Compact Low-Frequency High-Homogeneity Magnetic Field Exposure System for Cell Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

2. System Design Methods

2.1. Design of the Exposure System

- (1)

- The MF in a hollow fiber cartridge C2011 or a cartridge of similar size (AOI) must be practically homogeneous. The homogeneity of MF in AOI will be 97% or better. The cartridge or other AOI is cylindrical in shape to be positioned along the CS axes and symmetrically with respect to the CS origin. The AOI is defined as a cylindrical volume with a diameter of 30 and a length of 120 ;

- (2)

- The magnitude of an MF, which throughout this article refers to the magnetic flux density in the SI system of units, on the CS axis, must be tunable in the range of 0–2.5 (RMS);

- (3)

- Operating frequency must be adjustable in the range from 10 to 50 ;

- (4)

- The amount of power dissipated by the CS should not exceed 5 ;

- (5)

- The maximum size of the CS (including the protective cover) in the longitudinal (axial) direction must not exceed the cartridge longitudinal dimension by 1.7 times, while the maximum transverse dimension of the system cannot be larger than 8 times the cartridge diameter;

- (6)

- The system design must guarantee sufficiently good accessibility to the CS interior (the cartridge must not fit tightly into the CS interior and should not touch coil supporting surfaces).

- (1)

- While, in general, the larger the dimensions of the CS relative to the size of the region where a specific field uniformity level must be guaranteed, the better from the MF uniformity viewpoint, but unfortunately the CS dimensions are constrained by the size for practical applications in incubator;

- (2)

- Physically larger CS demonstrates significantly weaker MF on the CS axis for the same currents and winding parameters (the number of turns in each coil);

- (3)

- A higher magnitude of an MF in the AOI could be achieved by increasing coil currents;

- (4)

- The coil inductance leads to higher coil impedance of the coils;

- (5)

- Consequently, the load on the power supply increases with the operating frequency—the system must supply an increasing amount of power to maintain the same magnitude of the MF as at lower frequencies;

- (6)

- Higher coil winding resistance results in increased coil heating.

- (1)

- Design of the coil and CS—design and calculation of the dimensions of the coil windings and bodies, including windings cross-section shapes, the number of wire turns in windings, and the diameter of wires;

- (2)

- Design and calculation of the dimensions of the coil and cartridge support system;

- (3)

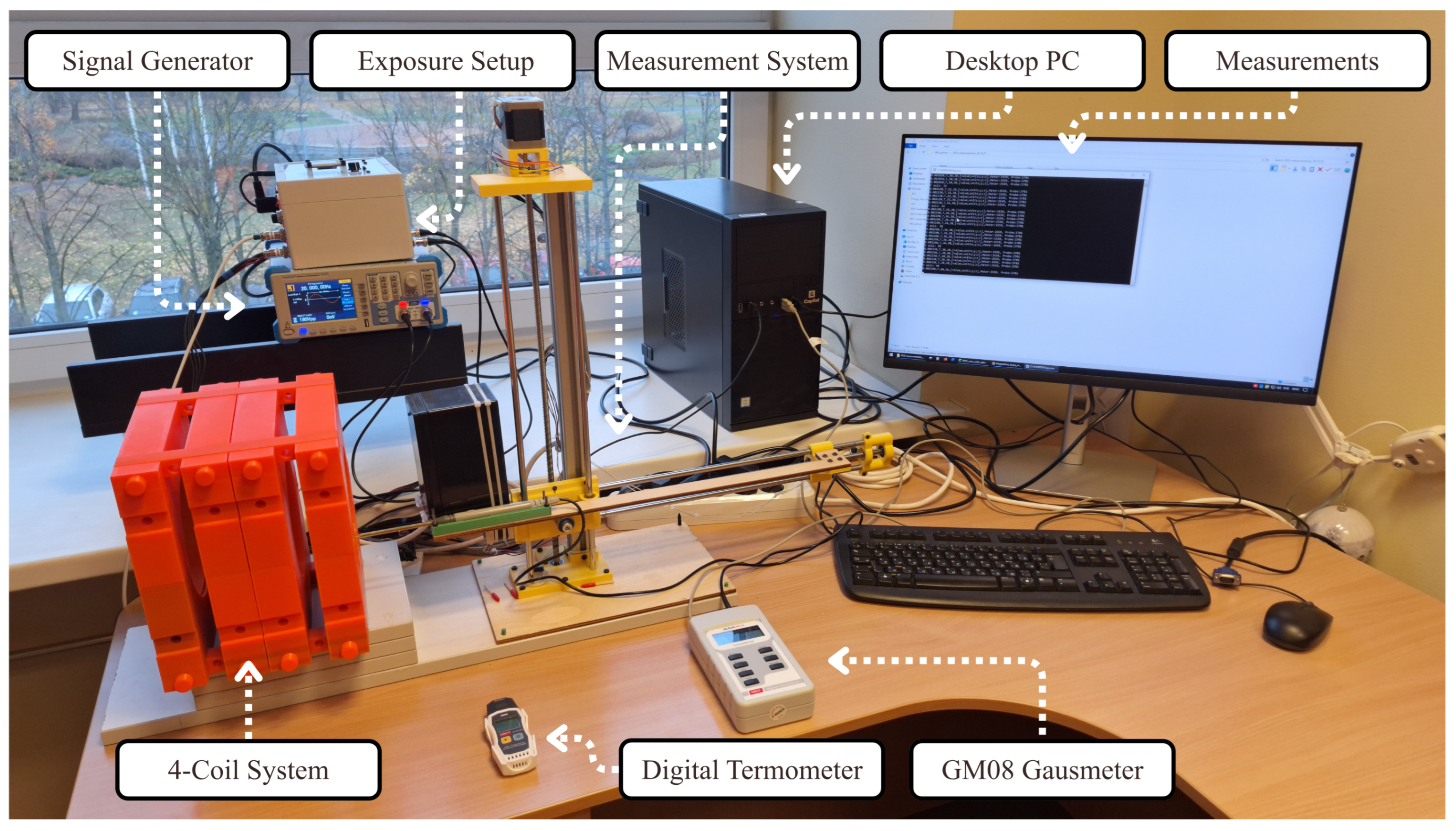

- Development of a personal computer (PC)-controlled two-axis MF measurement system for positioning the magnetic probe in CS space;

- (4)

- Choose suitable temperature sensors and their placement in CS, implementation of a temperature monitoring system (recording coil temperature during experiments and displaying temperature in real-time);

- (5)

- Selection and design of power supply system and control devices.

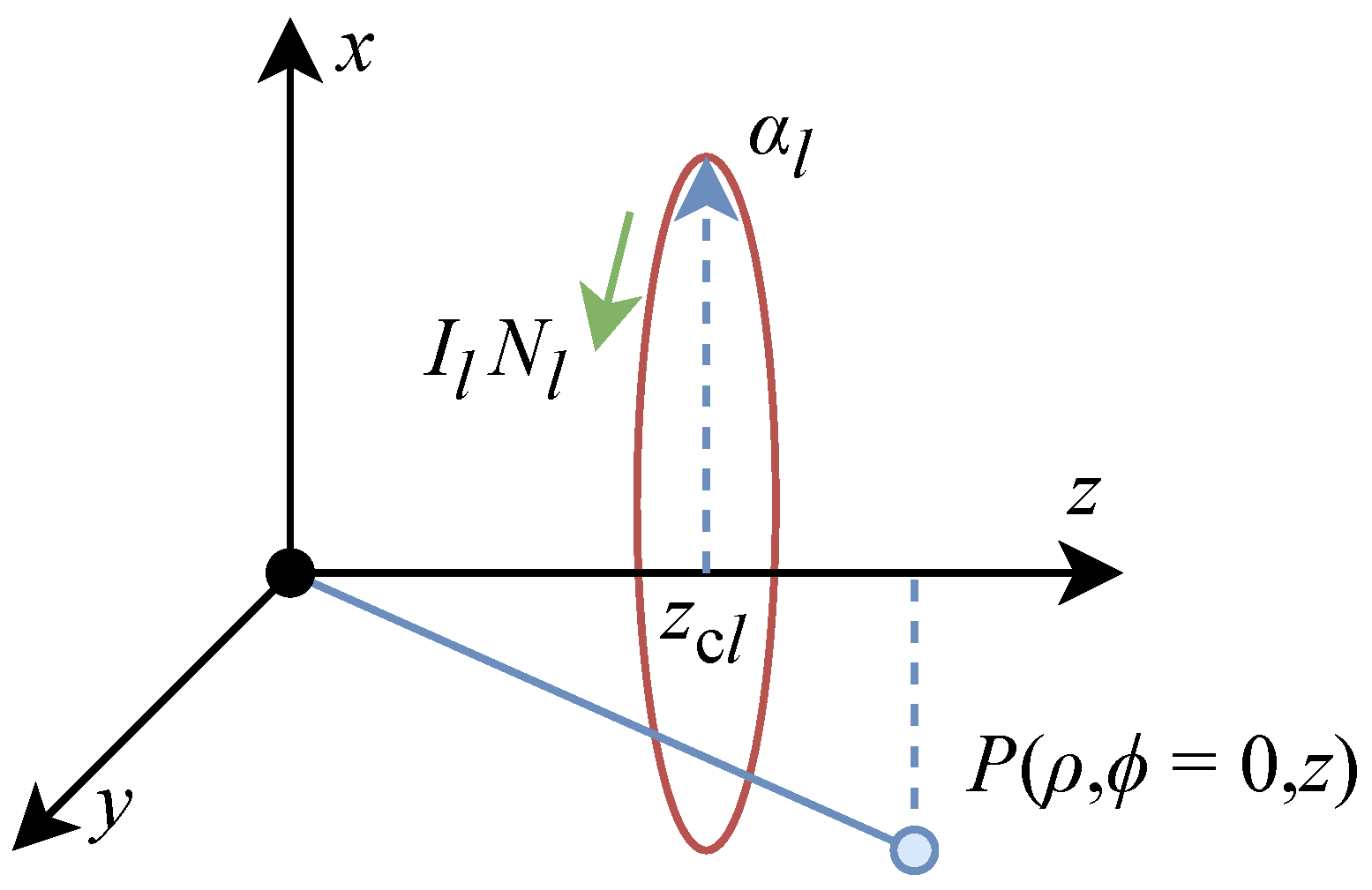

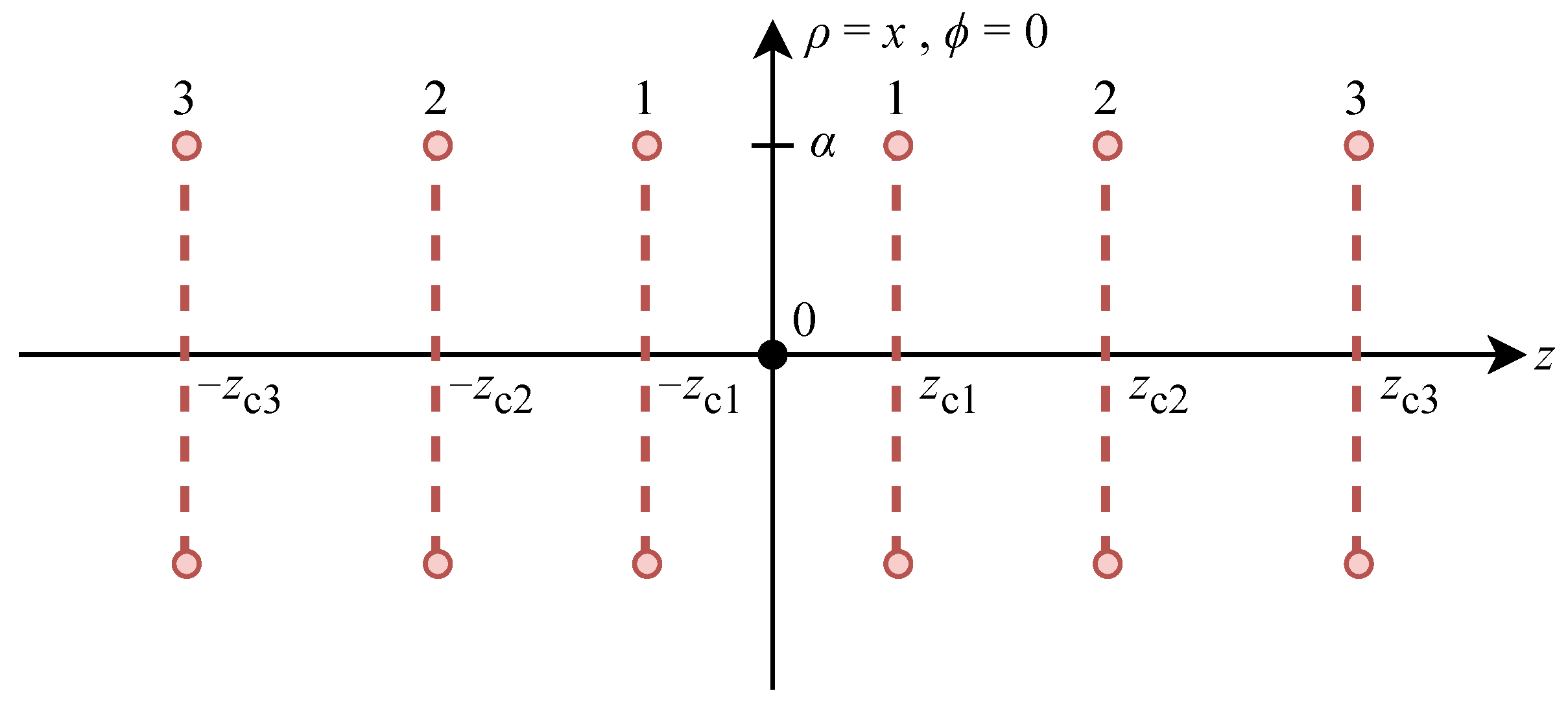

2.2. Methods and Approximate Models for the Coils and Coil System Design

- (1)

- The analysis of the very low-frequency MFs produced by CSs can be considerably simplified by assuming that each coil carries an equivalent current in a thin current turn (thin wire);

- (2)

- In many situations, numerical calculations may be simplified when coils with practical wires and real winding dimensions can be modeled as a set of single-turn coils with infinitely small wire radii.

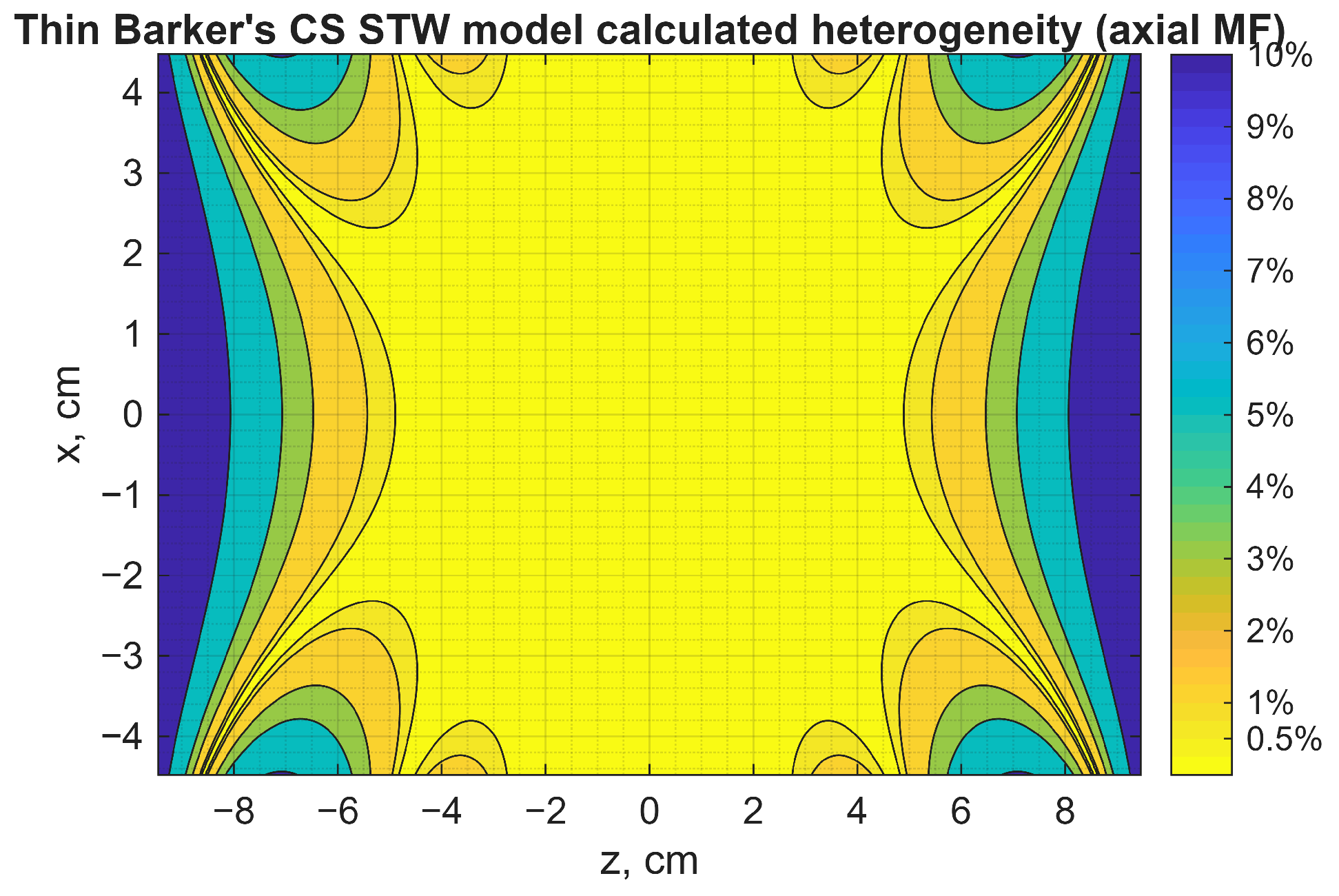

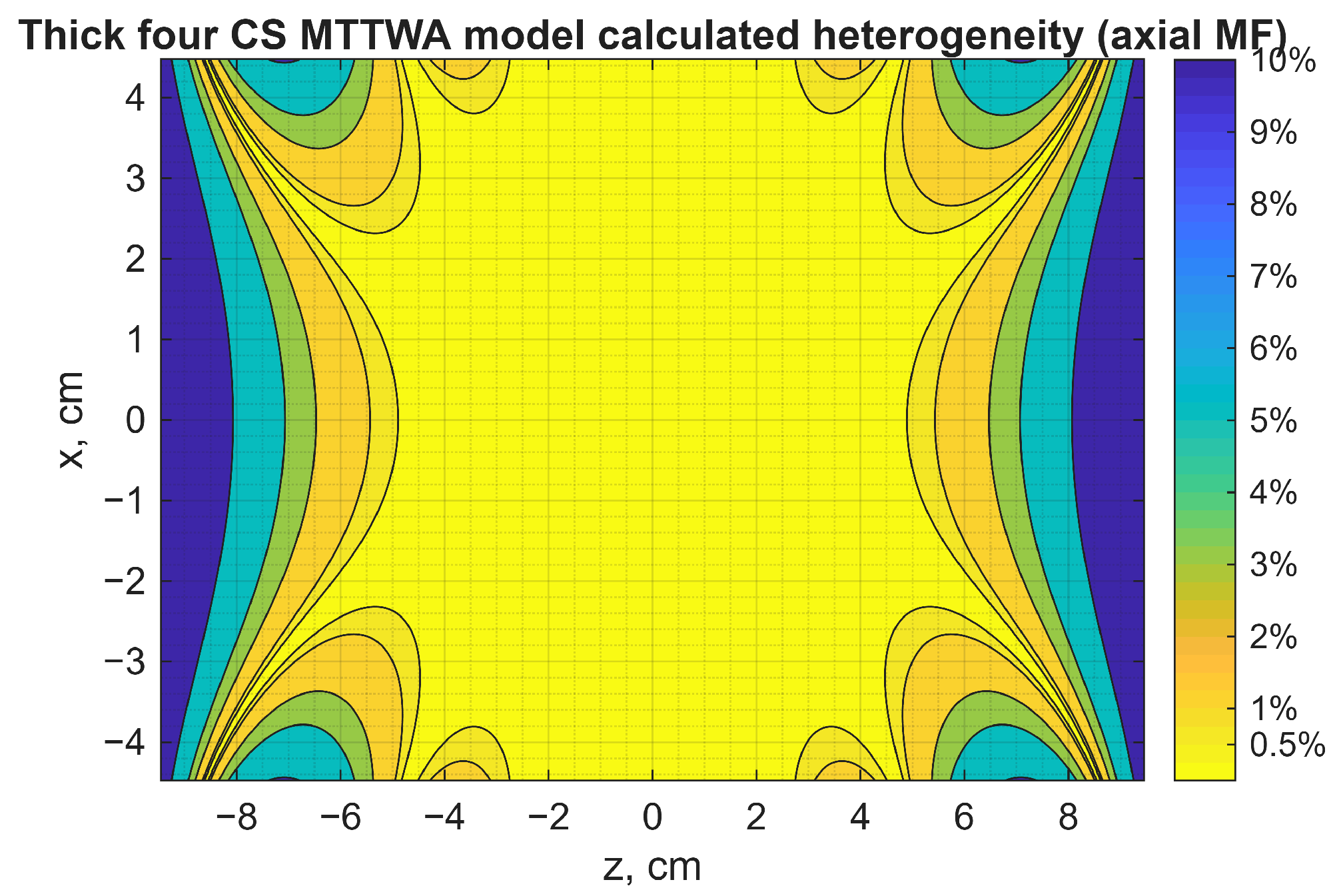

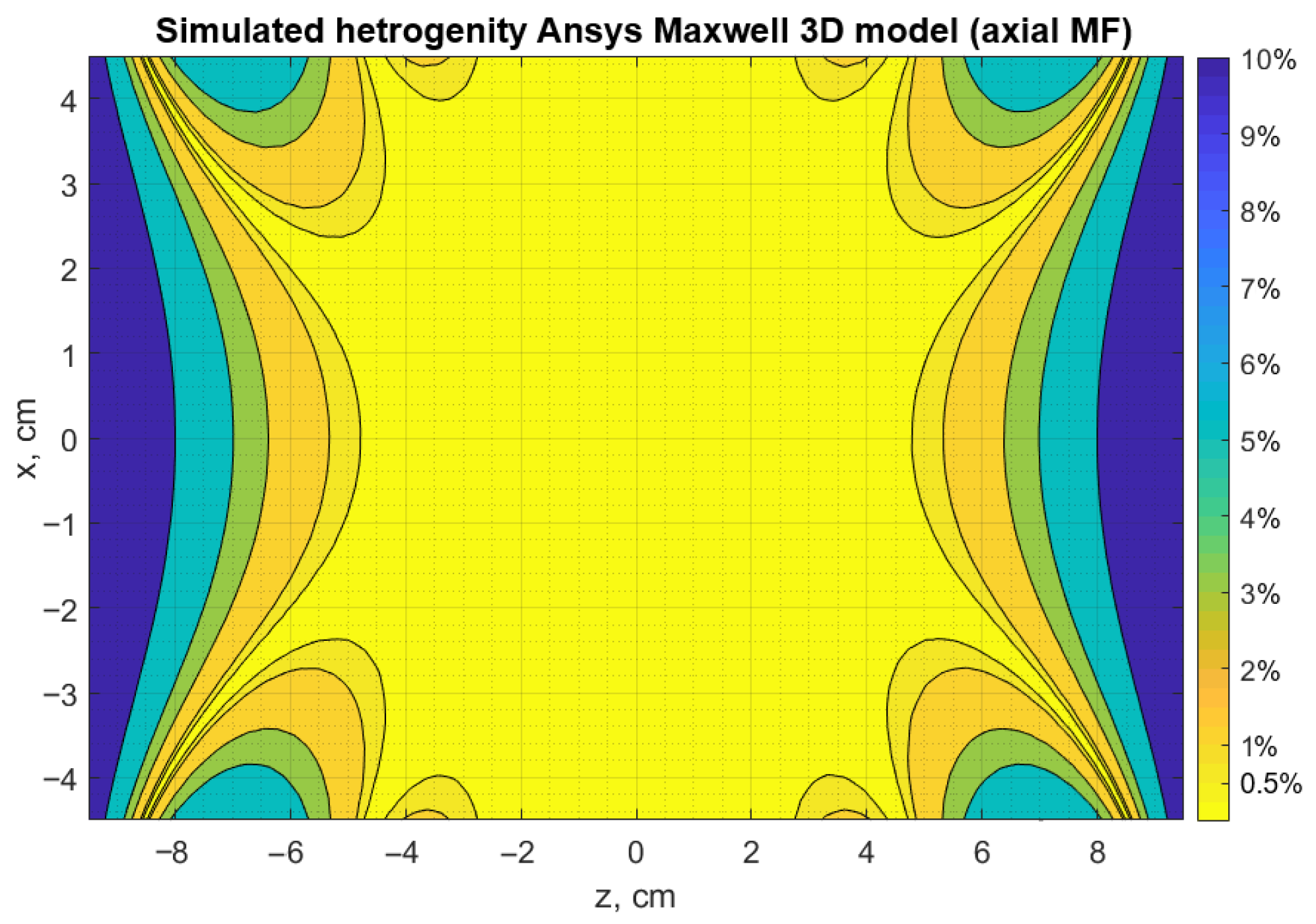

2.2.1. Heterogeneity of the Magnetic Field

2.2.2. Models for Thin Coils

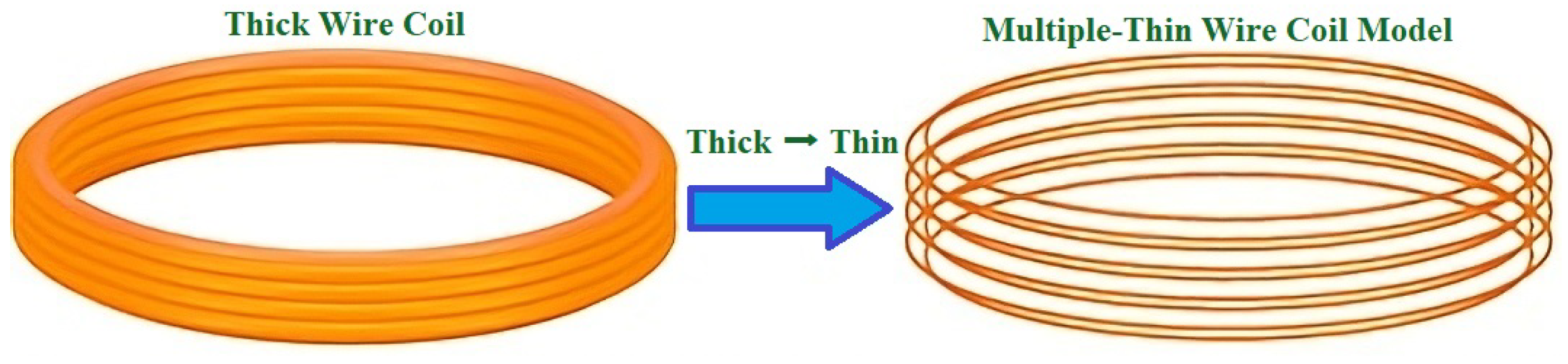

2.2.3. Multi-Turn Coil Approximation Method

- (1)

- Thick conductor coil with a very high current, in which case the radius of the wire will be large, and this fact must be taken into account in the calculations, as in this case it is unacceptable to disregard the wire dimensions;

- (2)

- Several thick wires forming a coil, but even in this case, the currents will have to be large, and the gaps between the wires cannot be ignored in the calculations;

- (3)

- A multi-turn practical coil, which is called a thick coil—a coil with a large number of wire turns when practical wires form a coil. In this investigation, we assume that a practical wire refers to a wire if the wire radii are much smaller than the smallest cross-sectional area of the winding and coil average radii. This type of coil is used in this study.

- (1)

- In the thick coils, small shape changes of the winding cross-section, small displacement of wires in the windings, and wire isolation do not cause notable uniformity changes and can be fully ignored if the wire radius is chosen small compared to the windings’ cross-section dimensions [30];

- (2)

- In the thick coils, current uniformity in wires is ignorable if the wire radius is chosen small compared to the windings’ cross-section dimensions [30].

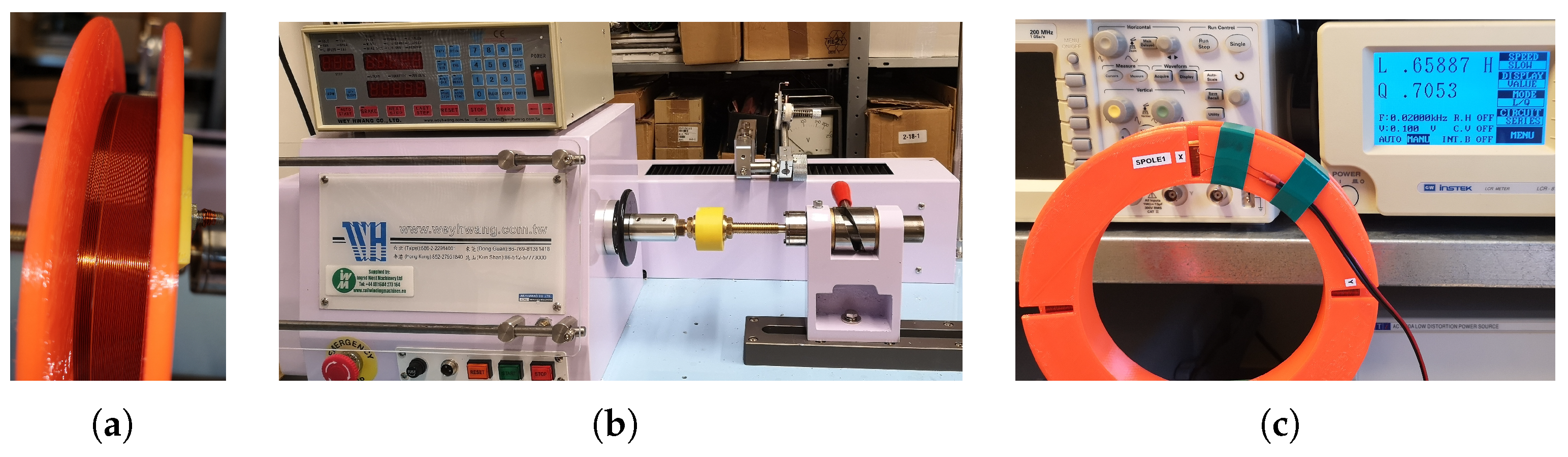

3. Coil and Coil System Design and Fabrication

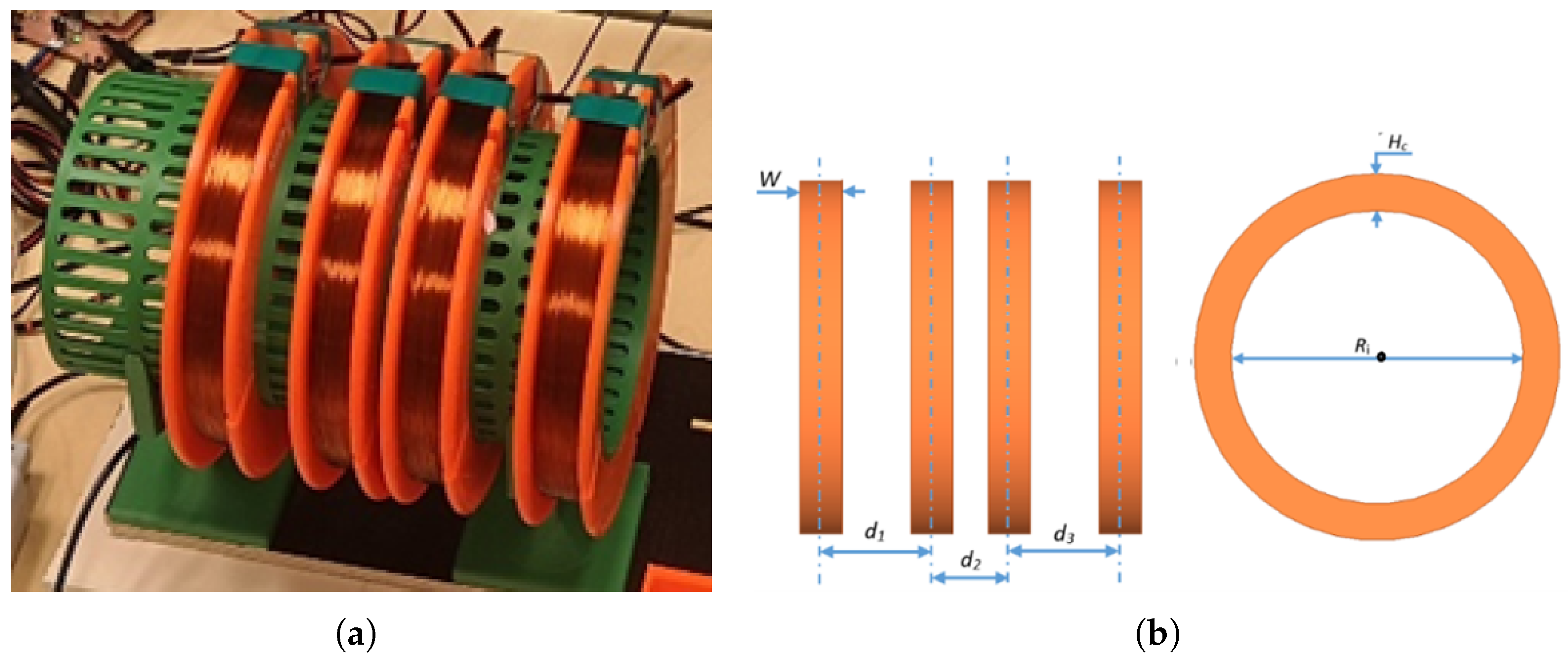

3.1. Coil Design and Fabrication

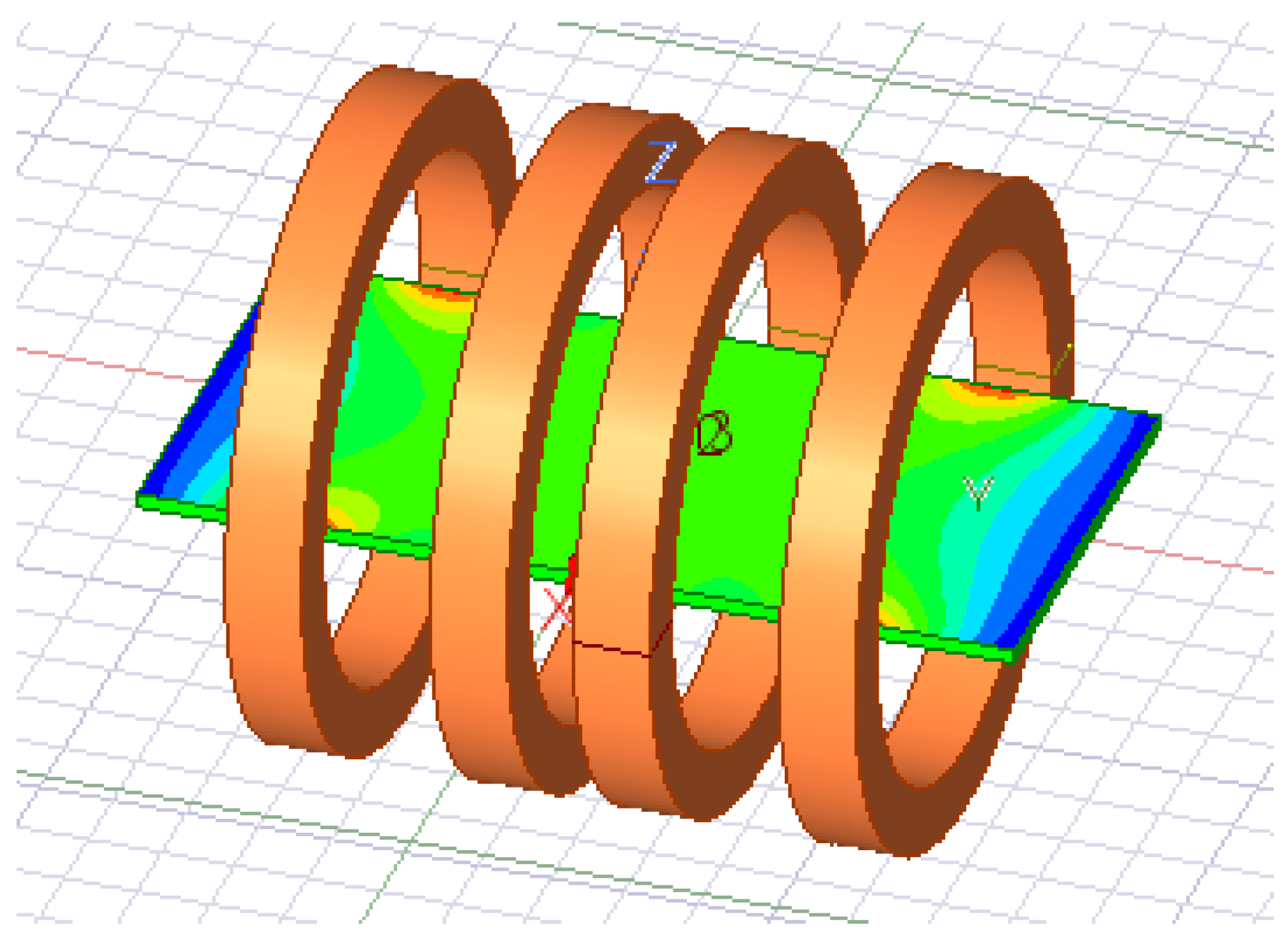

3.2. Coil System Design and Fabrication

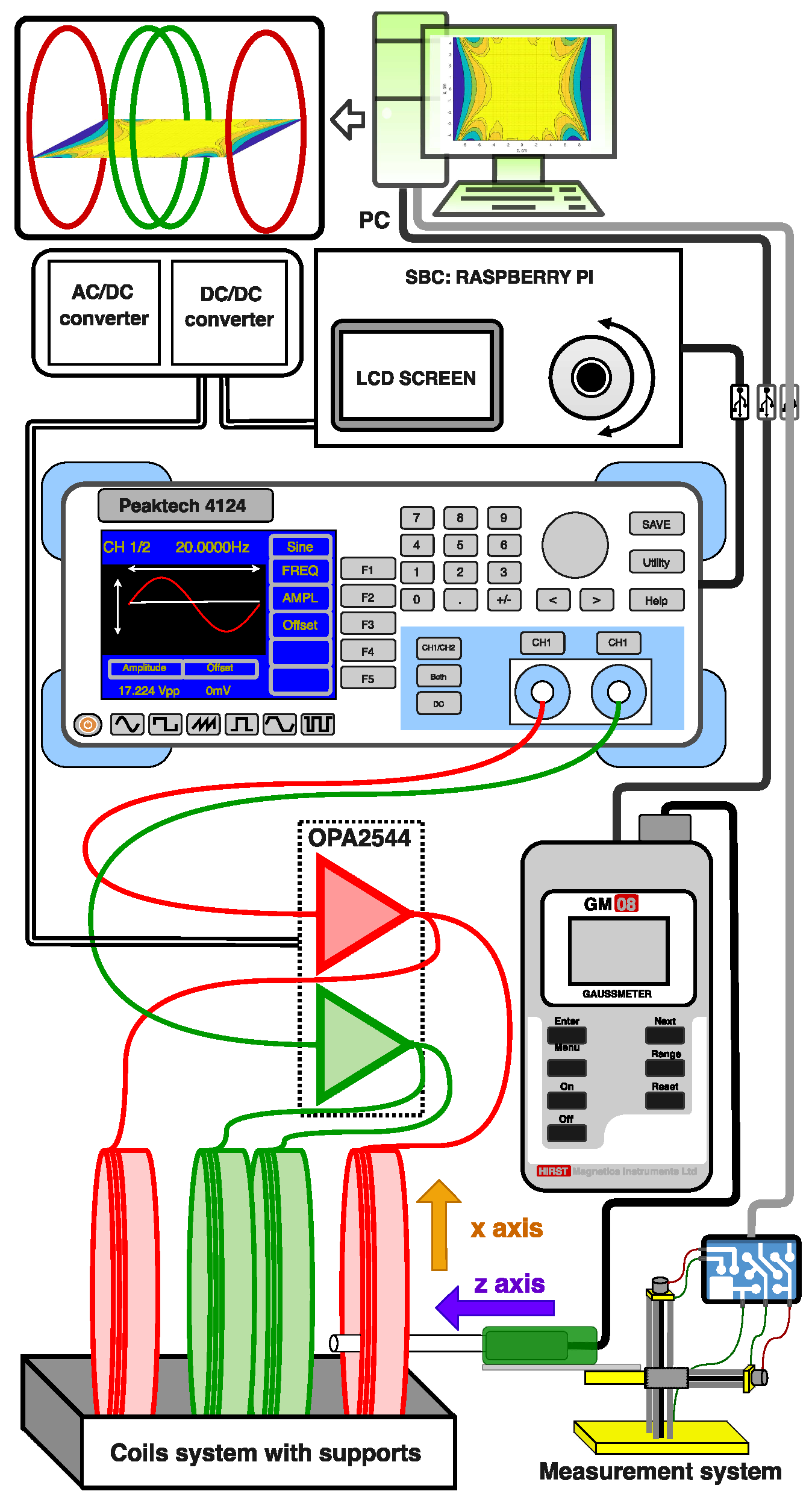

4. Exposure System

- (1)

- Dual channel operational amplifier Texas Instruments (Dallas, TX, USA) OPA2544;

- (2)

- AC-DC and DC-DC converters (Bel Power Solutions, West Orange, NJ, USA);

- (3)

- A liquid crystal display (LCD);

- (4)

- A device which measures the surface temperature of each coil and displays the temperature readings;

- (5)

- A device which reads and saves the MF probe measurements during the experiments;

- (6)

- An SBC;

- (7)

- Peripherals such as buttons and a rotary encoder for controlling the SBC settings.

5. Experimental Setup

6. Results and Discussion

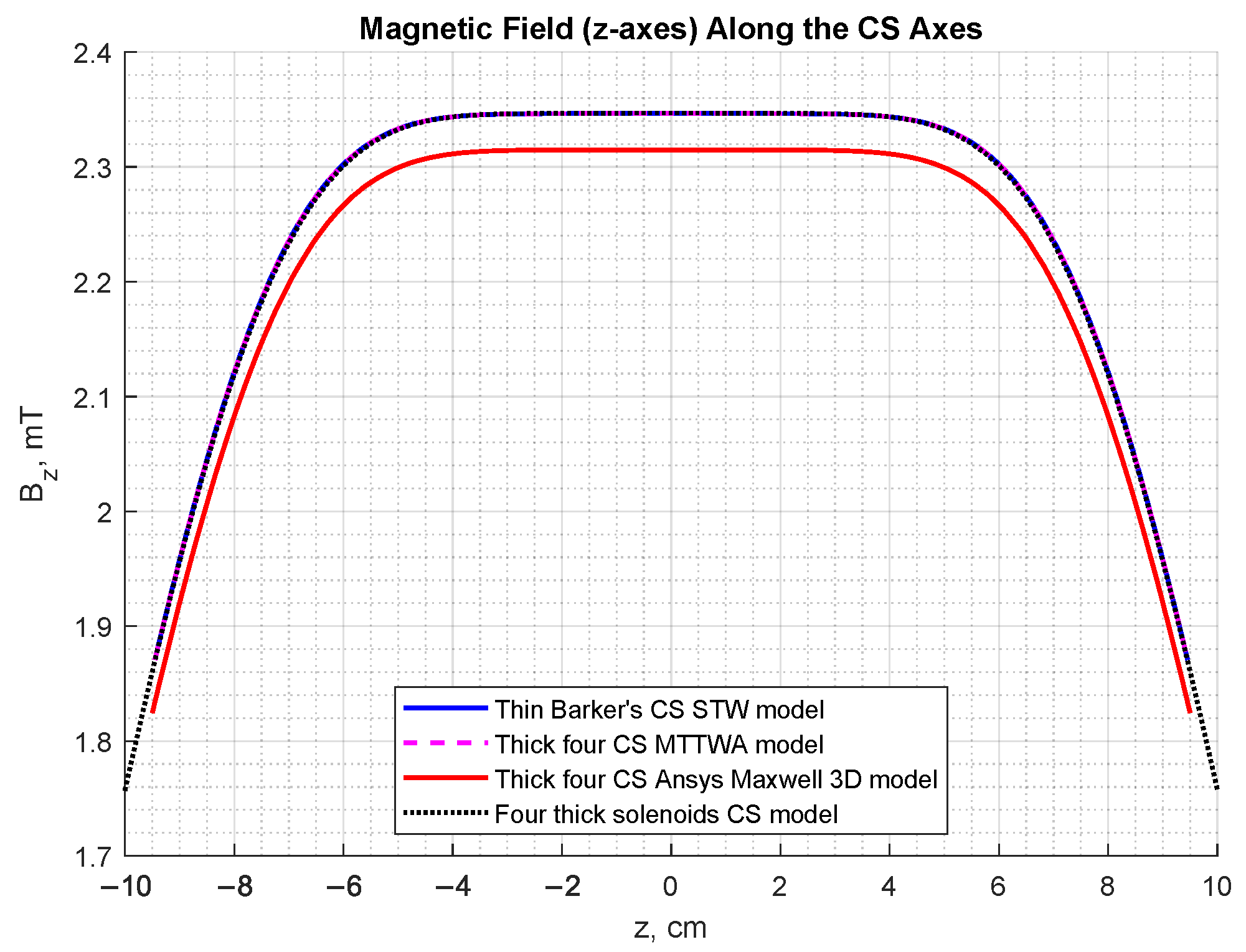

- Note 1

- Barker and Lee-Whitening one thin turn CSs are with the same parameters.

- Note 2

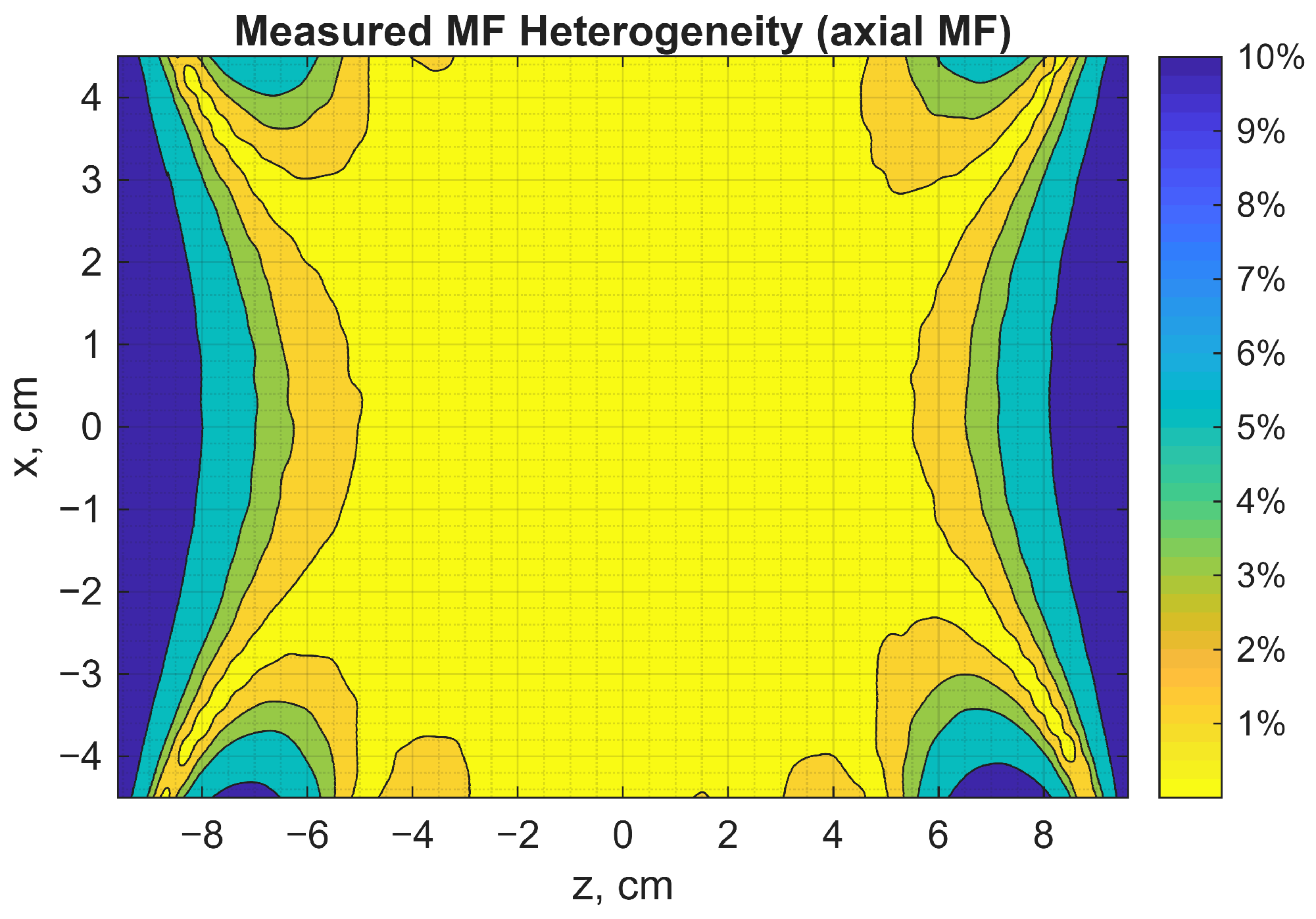

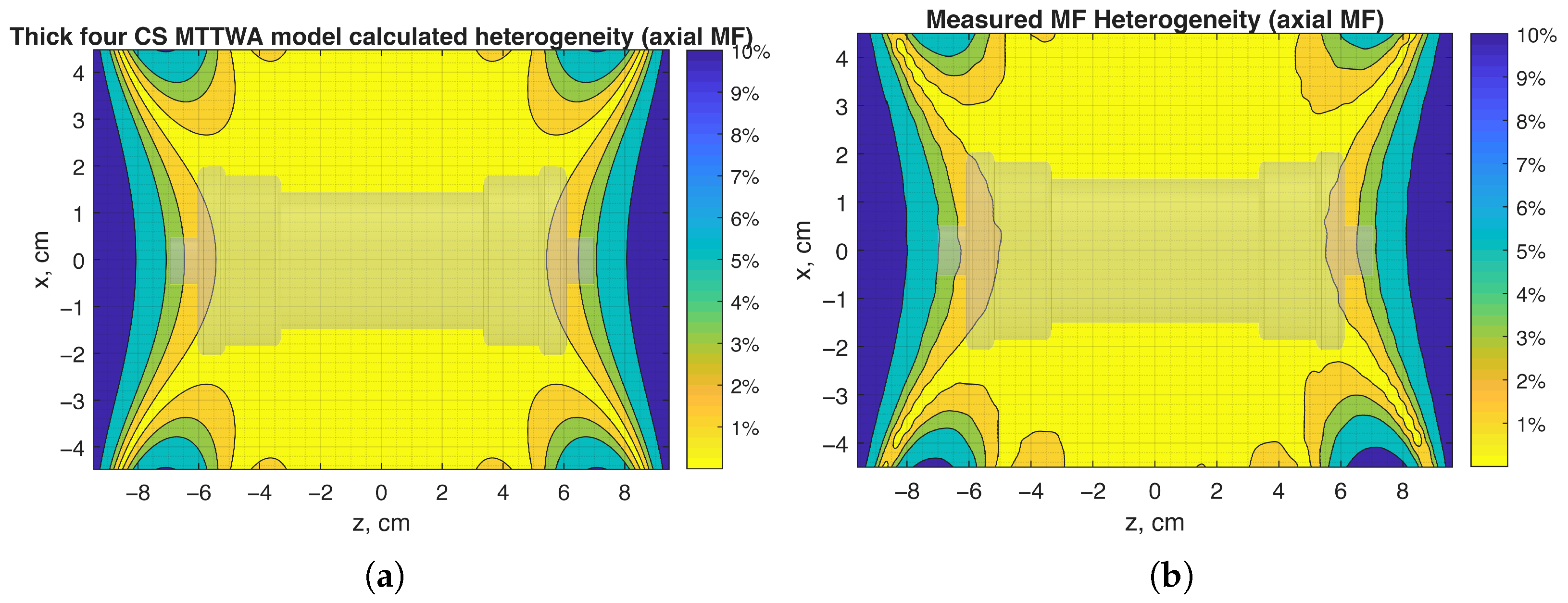

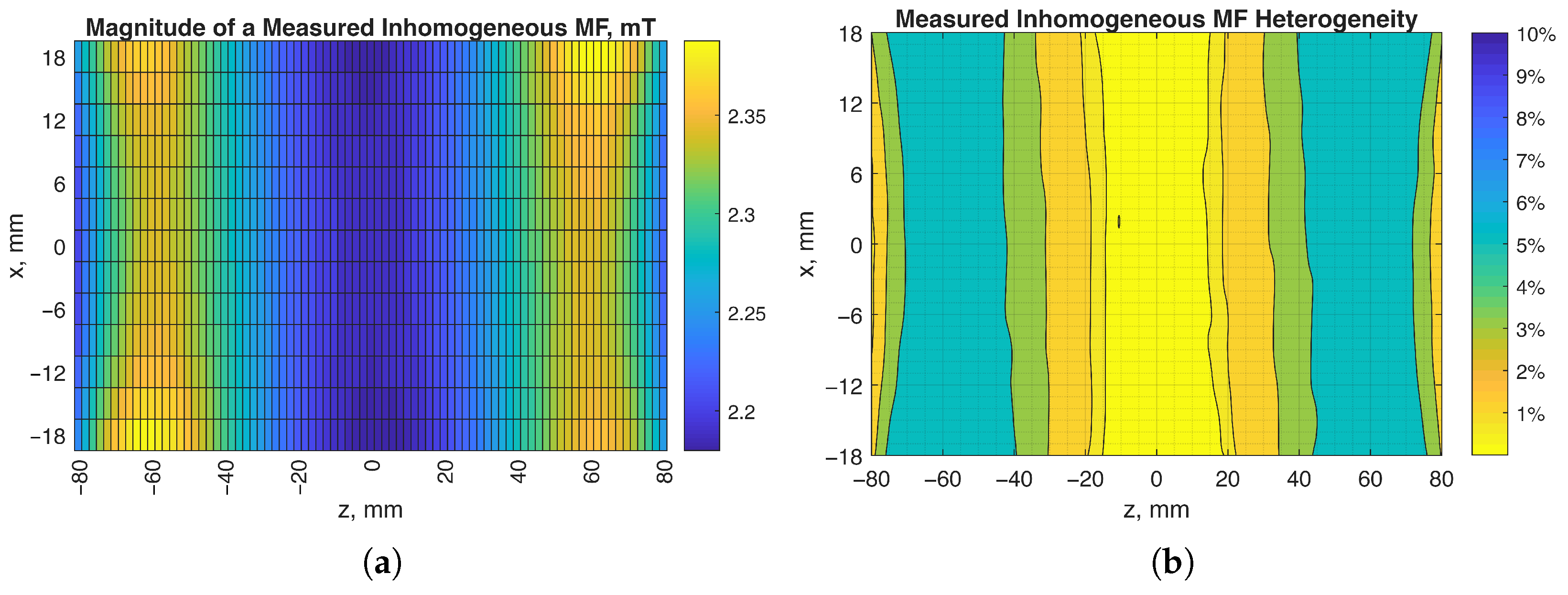

- Experimental measurement of the field in the CS volume at multiple points in space has been conducted.

- Note 3

- Thick Barker coil with parameters from Table 1 (distances between coil cross-section middle points and Barker’s ratio of currents in the outer and inner coils).

- Note 4

- No winding parameters set in [37].

- Note 5

- Two pairs of coils of different radii, symmetrical with respect to the center of a sphere, in which they are inscribed. The number of ampere-turns differs in the two pairs of coils. The average radius of coils is used for comparison. In [48], the optimal case is the radius of the sphere in which the system is inscribed.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFG | arbitrary function generator |

| AOI | area of interest |

| CS | coil system |

| FEM | finite element method |

| LCD | liquid crystal display |

| MF | magnetic field |

| MTTWA | multiple-turn thin-wire approximation |

| PC | personal computer |

| PCD | power supply and control device |

| PETG | polyethylene terephthalate glycol |

| RMS | root mean square |

| SBC | single board computer |

| STW | single thin wire |

References

- Pusta, A.; Tertis, M.; Crăciunescu, I.; Turcu, R.; Mirel, S.; Cristea, C. Recent Advances in the Development of Drug Delivery Applications of Magnetic Nanomaterials. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, R.M.; Novas, N.; Alcayde, A.; El Khaled, D.; Fernández-Ros, M.; Gazquez, J.A. Progress in the Knowledge, Application and Influence of Extremely Low Frequency Signals. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi, A.S.; Sendera, A.; Haghighipour, N.; Banas-Zabczyk, A. The Role of Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields on Mesenchymal Stem Cells Differentiation: A Systematic Review. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2022, 19, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Han, X.; Zhang, B.; Li, L. Analysis and Optimal Design of Magnetic Navigation System Using Helmholtz and Maxwell Coils. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2012, 22, 4401504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditterich, J.; Eggert, T. Improving the homogeneity of the magnetic field in the magnetic search coil technique. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2001, 48, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukharaev, A.A.; Zvezdin, A.K.; Pyatakov, A.P.; Fetisov, Y.K. Straintronics: A new trend in micro- and nanoelectronics and material science. Phys. Usp. 2018, 61, 1175–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivieri, R. Chapter Three—Metamaterial Properties of One-Dimensional and Two-Dimensional Magnonic Crystals. In Solid State Physics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; Volume 63, pp. 151–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R. Gradient coil design: A review of methods. Magn. Reson. Imaging 1993, 11, 903–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaskowski, A.; Gas, P. Estimation of SLP/ILP parameters inside a female breast tumor during hyperthermia with mobilized and immobilized magnetic nanoparticles. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2025, 27, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, M.; Fortuni, B.; Mulvaney, P.; Hofkens, J.; Uji-i, H.; Rocha, S.; Hutchison, J. Nanoparticle-mediated thermal Cancer therapies: Strategies to improve clinical translatability. J. Control. Release 2024, 372, 751–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gas, P.; Kurgan, E. Cooling effects inside water-cooled inductors for magnetic fluid hyperthermia. In Proceedings of the 2017 Progress in Applied Electrical Engineering (PAEE), Koscielisko, Poland, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gas, P. Behavior of helical coil with water cooling channel and temperature dependent conductivity of copper winding used for MFH purpose. Iop Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 214, 012124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowska, A.M.; Chmiel, P.; Rutkowski, P.; Telejko, M.; Spałek, M.J. Radiotherapy combined with locoregional hyperthermia for oligoprogression in metastatic melanoma local control. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2025, 17, 17588359251316189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López de Mingo, I.; Rivera González, M.X.; Ramos Gómez, M.; Maestú Unturbe, C. The Frequency of a Magnetic Field Reduces the Viability and Proliferation of Numerous Tumor Cell Lines. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, I.; Subbarao, R.B.; Rho, G.J. Human mesenchymal stem cells—Current trends and future prospective. Biosci. Rep. 2015, 35, e00191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Worrell, G.A.; Wang, H.L. It is the Frequency that Matters — Effects of Electromagnetic Fields on the Release and Content of Extracellular Vesicles. Cold Spring Harb. Lab. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszkowska, J.; Maliszewska, J.; Gas, P. Metabolic and Developmental Changes in Insects as Stress-Related Response to Electromagnetic Field Exposure. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatscher, J.; Pavez Loriè, E.; Mittermayr, R.; Meznik, P.; Slezak, P.; Redl, H.; Slezak, C. Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields (PEMF)—Physiological Response and Its Potential in Trauma Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collectif. Collection de Mémoires Relatifs à la Physique: Tome II. Mémoires sur L’électrodynamique, Première Partie; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1885; pp. 7–53. [Google Scholar]

- McKeehan, L.W. Gaugain-Helmholtz (?) Coils for Uniform Magnetic Fields. Nature 1934, 133, 832–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.R. New Coil Systems for the Production of Uniform Magnetic Fields. J. Sci. Instrum. 1949, 26, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, M.W. Axially Symmetric Systems for Generating and Measuring Magnetic Fields. Part I. J. Appl. Phys. 1951, 22, 1091–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, M.W. The Method of Zonal Harmonics. In High Magnetic Fields; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, M.W. Thick Cylindrical Coil Systems for Strong Magnetic Fields with Field or Gradient Homogeneities of the 6th to 20th Order. J. Appl. Phys. 1967, 38, 2563–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, M.W. Calculation of Fields, Forces, and Mutual Inductances of Current Systems by Elliptic Integrals. J. Appl. Phys. 1963, 34, 2567–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boridy, E. Magnetic fields generated by axially symmetric systems. J. Appl. Phys. 1989, 66, 5691–5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluck, F. Axisymmetric Magnetic Field Calculation with Zonal Harmonic Expansion. Prog. Electromagn. Res. B 2011, 32, 351–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jackson, J.D. Classical Electrodynamics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smythe, W.R. Static and Dynamic Electricity; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Beiranvand, R. Effects of the Winding Cross-Section Shape on the Magnetic Field Uniformity of the High Field Circular Helmholtz Coil Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 7120–7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosser, M.S.; Scott, S.; Clark, A.; Wilt, P.M. On the magnetic field near the center of Helmholtz coils. Rev. Sci. Instruments 2010, 81, 084701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhou, B.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Pang, H.; Chen, L.; Quan, W.; Liu, G. Design of Highly Uniform Magnetic Field Coils Based on a Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 125310–125322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapuh, R.; Aslan, C.; Stibernik, K.; Hudlicka, M. Uniform magnetic field coils construction optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC Europe, Brugge, Belgium, 2–5 September 2024; pp. 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Zhang, C.; Ge, F.; Qian, B.; Sun, H. A Parameter Design Method for a Wireless Power Transmission System with a Uniform Magnetic Field. Energies 2022, 15, 8829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; She, S.; Zhang, S. An improved Helmholtz coil and analysis of its magnetic field homogeneity. Rev. Sci. Instruments 2002, 73, 2175–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.J. Parametric design of tri-axial nested Helmholtz coils. Rev. Sci. Instruments 2015, 86, 054701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatonov, I.; Baranov, P.; Kolomeycev, A. Magnetic field computation and simulation of the coil systems using Comsol software. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 158, 01032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranova, V.E.; Baranov, P.F.; Muravyov, S.V.; Uchaikin, S.V. The Production of a Uniform Magnetic Field Using a System of Axial Coils for Calibrating Magnetometers. Meas. Tech. 2015, 58, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabuis, A.; Ren, X.; Duong, T.; Perriard, Y. Exploring Beyond the Helmholtz Coils for Uniform Magnetic Field Generation With Topology Optimization. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2022, 58, 7001404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Fu, P.; Huang, Z.; Xu, X. Optimal Design Method to Improve the Magnetic Field Distribution of Multiple Square Coil Systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 171184–171194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Song, Z.; Jiang, L.; Rao, B.; Zhang, M. An Improved Two-Coil Configuration for Low-Frequency Magnetic Field Immunity Tests and Its Field Inhomogeneity Analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 8204–8214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, R.; Jiang, L.; Qin, B. Improved Square-Coil Configurations for Homogeneous Magnetic Field Generation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 6350–6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, A.L.; Innes, D.J.; Rempel, R.C.; Ruddock, K.A. Octagonal Coil Systems for Canceling the Earth’s Magnetic Field. J. Appl. Phys. 1965, 36, 2560–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprari, R.S. Optimal current loop systems for producing uniform magnetic fields. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1995, 6, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Whiting, G. Uniform Magnetic Fields; Atomic Energy of Canada Limited: Chalk River, ON, Canada, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, M.E.; Waidelich, D.L. Three and Four Coil Systems for Homogeneous Magnetic Fields. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. 1964, 2, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenako, J.; Kusnins, R.; Litvinenko, A.; Deksnis, R. Axial Cylindrical Three-Coil Systems for Producing a Uniform Magnetic Field. In Proceedings of the 2023 Workshop on Microwave Theory and Technology in Wireless Communications (MTTW), Riga, Latvia, 4–6 October 2023; pp. 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottardi, G.; Mesirca, P.; Agostini, C.; Remondini, D.; Bersani, F. A four coil exposure system (tetracoil) producing a highly uniform magnetic field. Bioelectromagnetics 2003, 24, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiranvand, R. Analyzing the uniformity of the generated magnetic field by a practical one-dimensional Helmholtz coils system. Rev. Sci. Instruments 2013, 84, 075109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiranvand, R. Magnetic field uniformity of the practical tri-axial Helmholtz coils systems. Rev. Sci. Instruments 2014, 85, 055115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves, F.J.; Bayón, A.; Gascón, F. Optimization of the magnetic field homogeneity of circular and conical coil pairs. Rev. Sci. Instruments 2019, 90, 045120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kędzia, P.; Czechowski, T.; Baranowski, M.; Jurga, J.; Szcześniak, E. Analysis of Uniformity of Magnetic Field Generated by the Two-Pair Coil System. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2013, 44, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deksnis, R.; Eidaks, J.; Kuznecova, A.; Kusnins, R.; Semenako, J. A Compact Symmetric Four-Coil Uniform Magnetic Field Generating System for Biological Studies. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 11th Workshop on Advances in Information, Electronic and Electrical Engineering (AIEEE), Valmiera, Latvia, 31 May–1 June 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristic-Djurovic, J.L.; Gajic, S.S.; Ilic, A.Z.; Romcevic, N.; Djordjevich, D.M.; De Luka, S.R.; Trbovich, A.M.; Jokic, V.S.; Cirkovic, S. Design and Optimization of Electromagnets for Biomedical Experiments With Static Magnetic and ELF Electromagnetic Fields. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 4991–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judakova, Z.; Janousek, L.; Radil, R.; Carnecka, L. Low-Frequency Magnetic Field Exposure System for Cells Electromagnetic Biocompatibility Studies. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.R. Improvements to the system of four equiradial coils for producing a uniform magnetic field. J. Phys. Sci. Instruments 1983, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Barker’s Coil Value [21] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance between outer coil and inner coil | 56.4 | – | |

| Distance between outer coil and inner coil | 39.1 | – | |

| Coil winding width (the same for all coils) | W | 21.3 | – |

| CS winding height (the same for all coils) | 17.9 | – | |

| Coil winding average radius (measured) | 80.1 | – | |

| Number of horizontal turns (the same for all coils) | 43 | – | |

| Number of vertical turns (the same for all coils) | 38 | – | |

| Number of turns in coil (the same for all coils) | N | 1634 | – |

| Wire outer diameter | 0.4 | – | |

| (calculated and installed) | – | 0.244070 | 0.243186 |

| (calculated and installed) | – | 0.948190 | 0.940731 |

| Current in either outer coil (rms) | 116 | – | |

| Current in either inner coil (rms) | 51.5 | – | |

| – | 2.252427 | 2.260444 | |

| Operating frequency | f | 20 | – |

| Reference | CS | Coils | Method | Where Heterogeneity Is n% | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Proposed CS | 4 equal radii coils | One thin turn coil | STW | See Section 2.2.2 | |||

| 2. | [21,43] | 4 equal radii coils. Barker and Lee-Whiting | One thin turn coil | STW | Note 1 | |||

| 3. | Proposed CS | 4 equal radii coils | Thick multi-turn coil | MTTWA | See Section 2.2.3, Table 1 and Note 2 | |||

| 4. | — | Barker parameters | Thick multi-turn coil | MTTWA | Note 3 | |||

| 5. | [37] | 4 equal radii coils | Thick multi-turn coil | Comsol FEM multi-turn coil | Note 4 | |||

| 6. | [48] | 4 coils | Thick multi-turn coil, two pairs | Numerical calculations | No data | No data | Note 5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Semenako, J.; Kiselevskis, A.; Tihomorskis, N.; Terauds, M.; Migla, S. Compact Low-Frequency High-Homogeneity Magnetic Field Exposure System for Cell Studies. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010003

Semenako J, Kiselevskis A, Tihomorskis N, Terauds M, Migla S. Compact Low-Frequency High-Homogeneity Magnetic Field Exposure System for Cell Studies. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleSemenako, Janis, Arturs Kiselevskis, Nikolajs Tihomorskis, Maris Terauds, and Sandis Migla. 2026. "Compact Low-Frequency High-Homogeneity Magnetic Field Exposure System for Cell Studies" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010003

APA StyleSemenako, J., Kiselevskis, A., Tihomorskis, N., Terauds, M., & Migla, S. (2026). Compact Low-Frequency High-Homogeneity Magnetic Field Exposure System for Cell Studies. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010003