1. Introduction

Porous materials have important impact-damping properties and are widely used in our daily life. They are available in a large variety of materials (foams, textiles, woven or non-woven, etc.) which can be obtained from natural sources or synthetized. In recent years, highly compressible porous materials gained interest in various studies focused on high impact energy. The solid structure of the porous materials can absorb energy when deformed due to mechanical impact [

1]. Elastoplastic bending of walls of cellular solids [

2], buckling or shearing of the filaments and contacting between filaments of textiles [

3] contribute to the overall damping energy and influence the material response when compressed. Early studies ignored the presence of the air inside the pores [

2], but for higher strain rates the influence of gas must be considered [

4,

5]. Liquids, when used to imbibe porous materials, play a more important role in their dynamic behavior [

6,

7,

8]. Models such as Darcy–Brinkman and other porosity–permeability formulations have been particularly useful in describing flow, even in high-porosity structures.

Typical materials used for impact-damping applications are reticulated foams or textiles materials (woven or nonwoven), with an initial porosity around 0.9 or greater [

9,

10]. Permeability variation during compression is one of the key factors in generating lift effects. This type of damping mechanism opens new research directions. The envisioned applications are sports equipment, damping systems for the automotive industry (i.e., collision systems, shock absorbers, etc.) and protective equipment for medium and high impact energy. A similar mechanism can be found inside human joints, where a naturally produced fluid—the synovial fluid—imbibes a porous cartilage [

7]. According to ex-poro-hydrodynamic (XPHD) lubrication theory developed by Pascovici and Cicone [

7], the resistance to flow inside the porous material generates an important load-carrying capacity. The resistance to flow increases during compression due to decreasing porosity and permeability [

11]. During impact, the soft, porous materials imbibed with fluids are compressed rapidly, and for high impact energies the voids collapse simultaneously, squeezing out the fluid [

9], usually in a different direction. In one of the first published studies, Hilyard [

12] provided a third-order, nonlinear equation of motion to understand the contribution of fluid flow to the impact behavior of open-cell foams. More recently, Dawson et al. [

6] presented a tractable model to describe fluid contribution under dynamic compression for high-porosity, low-density, reticulated foams imbibed with a Newtonian fluid. Cicone et al. [

13] revealed that under impact compression there is an optimal initial porosity of the porous layer that minimizes the peak impact force, which is a key factor governing the effect on the impacted structure.

The need for protective equipment for hazardous recreational activities or for personnel handling high-risk activities could justify further investigation into the effect of the presence of fluids inside the porous structures and their response under dynamic compression. Undoubtedly, military regulations impose severe conditions in the design of ballistic protection, but the modern war in Ukraine can galvanize the research for unprecedented new solutions. Two research directions can be underlined related to the usage of non-Newtonian fluids for impact protection: the flow of shear-thickening (dilatant) fluids inside porous materials (when subjected to compression the viscosity increase with the shear rate will instantly create an opposite force) and the flow of shear-thinning (pseudoplastic) fluids inside porous materials (the viscosity decrease with the shear rate and by fluid flow fostering the impact force is damped).

An extensive analysis of the published experimental results for non-Newtonian flow inside porous structures reveals that most of the studies are dedicated to geological applications [

14] for rocks and soil. Most of the existing work on shear-dependent flow in porous structures originates from enhanced oil recovery, where polymer solutions permeate geological media [

15], which is a rigid porous matrix. Significant interest exists in studying blood flow through porous structures for biomedical applications [

16], and experimental methods continue to advance in filtration and mold-injection industries. However, we found a scarcity of studies related to the damping capacity of deformable porous materials imbibed with non-Newtonian fluid flow. The study by Dowson et al. [

17] is one of few that focuses on elastomeric foam filled with colloidal silica under dynamic compression, where the fluid behaves as a shear-thickening fluid under dynamic flow conditions. A distinct and extensively studied category concerns ballistic woven fabrics and the enhancement of their performance through imbibition with shear-thickening fluids [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. In contrast, a comprehensive survey of the literature published over the past five years across major scientific databases revealed no studies addressing shear-thinning fluids in soft, porous materials for impact applications.

Given the growing interest in lightweight, flexible and tunable protective systems, understanding the mechanics of shear-thinning fluids within deformable porous architectures is essential. Under rapid compression, the porous channels narrow significantly, increasing local shear rates within the fluid while reducing viscosity. This viscosity reduction facilitates sustained radial fluid flow through progressively narrowing porous channels, even at high compressive strains. Consequently, viscous dissipation is maintained, delaying premature stiffening leading to reduced peak impact forces and enhanced energy-absorption efficiency. Despite the relevance of this mechanism, no studies have investigated shear-thinning flow within deformable porous materials under dynamic compression.

The lack of recent studies in this area motivates the present work, which focuses on the coupled damping behavior of shear-thinning fluids and porous materials. More accurately, the objective of this study is to examine the dynamic impact response of a 3D spacer textile imbibed with a shear-thinning polyvinyl-alcohol–carbon-nanofiber solution. The use of three-dimensional fabrics has gained interest, especially in cushioning or impact-damping applications [

25,

26]. Understanding the contribution of the fluid was approached using the assumptions of ex-poro-hydrodynamic lubrication. Using controlled drop-weight experiments, we evaluated the overall ability of the shear-thinning fluid to contribute to energy absorption and impact-force reduction for different concentrations of the carbon nanofiber additive. The influence of textile structural parameters and the interaction between fibrous structure and the fluid was not analyzed in detail. Moreover, this paper discusses and compares the observed response with known mechanisms in shear-thickening systems. The present work provides one of the first experimental demonstrations of shear-thinning-assisted damping in highly compressible porous foams.

3. Results and Discussion

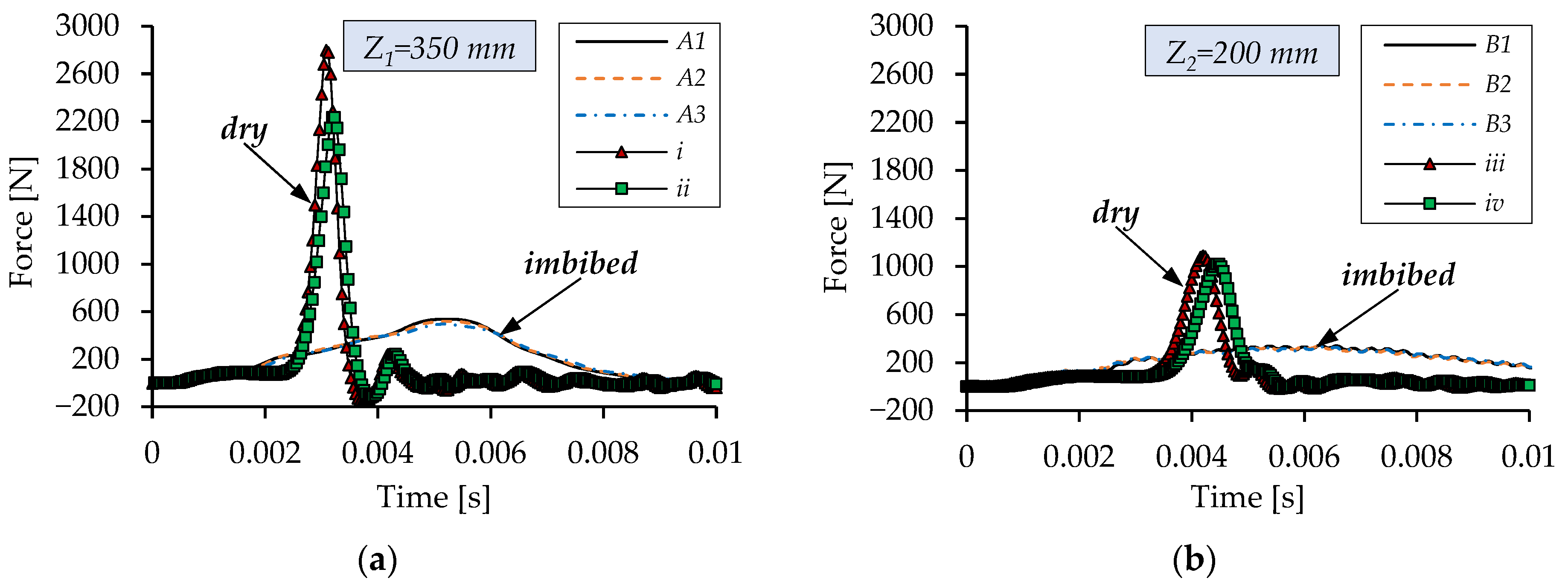

First, the variation in force over time was compared between the dry material (tests

i,

ii for

Z1 = 350 mm and

iii,

iv for

Z2 = 200 mm) and imbibed material with a solution of water and 9% PVA.

Figure 6 presents force variation during tests using a drop height

Z1 = 350 mm and

Z1 = 200 mm. The tests presented for

Z1 and

Z2 are annotated with A and B, respectively. A minimum of three tests, each performed on a new sample, were performed to evaluate the reproducibility of the results. With a corresponding impact energy

E1 = 1.38 J, the force recorded for dry material is significantly higher, 4 times greater. The dry material’s steep impact-force variation suggests that it was compressed enough to reach densification (“bottoming up” [

37]). A force reduction was also observed for the imbibed material for

Z2 = 200 mm, with a corresponding impact energy of

E2 = 0.79 J.

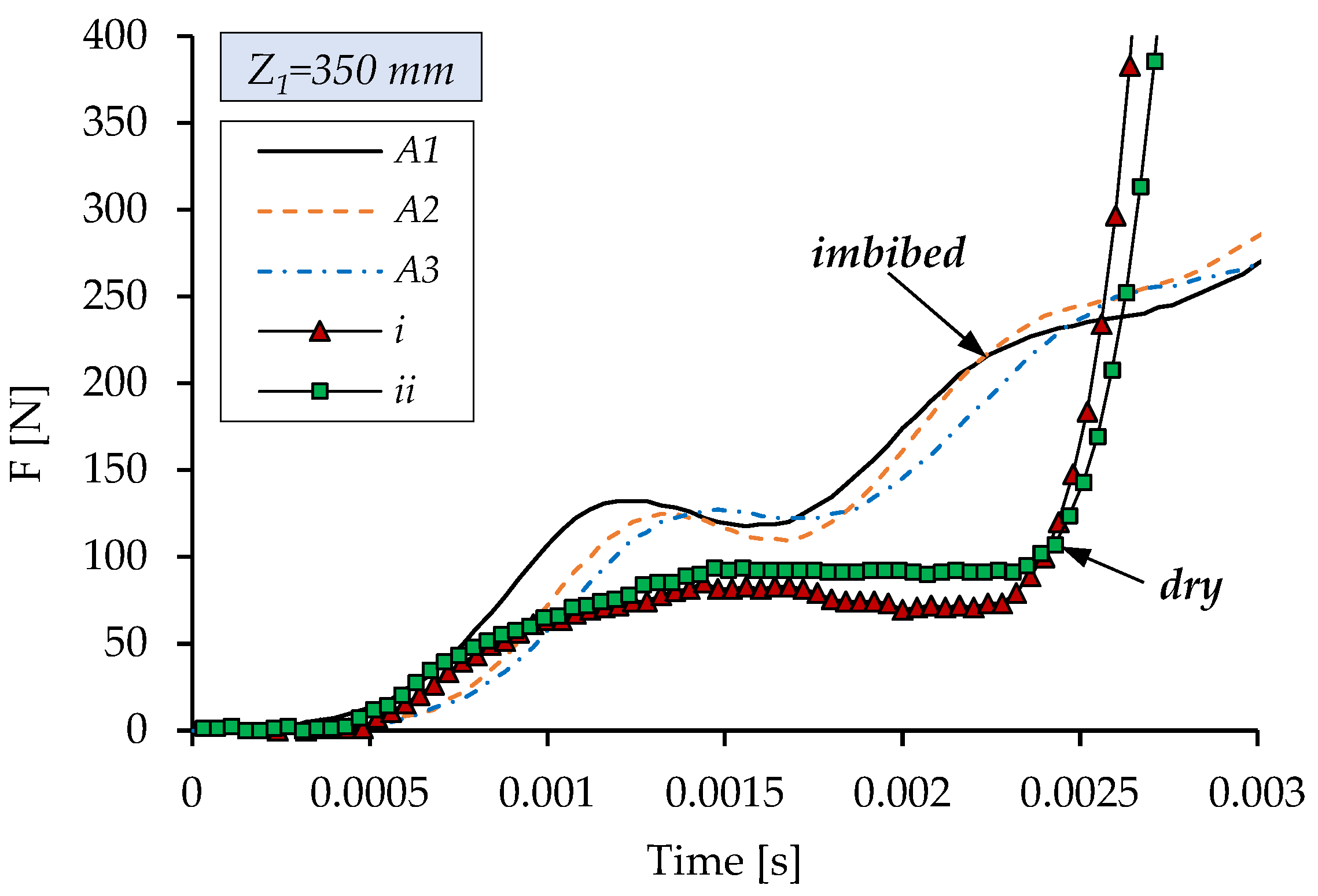

Figure 7 shows a magnified view in force variation (first 3 ms) for dry material, displaying typical behavior similar to the low-speed tests in

Figure 4. The force has a linear variation, followed by a plateau. Furthermore, the force increases very steeply, marking the beginning of the densification stage. For this test, the stress corresponding to the maximum force produced divided by area is 2.2 MPa. Comparing this result with the response of dry material (

Figure 6) and other studies from the literature [

33], the impact energy was too high for this drop height causing a hard contact due to “bottoming up”.

The experimental data shows a 4% scattering in terms of maximum force. This is due to errors in drop height adjustment, small kinetic energy losses from friction between the impactor and guiding tube or misalignment of the contact surfaces. All these factors can lead to unequal distribution of contact pressure. The misalignment of the contact surfaces, observed using high-speed images, is up to a maximum of 1.5°. With higher impact energies, misalignment effects become more significant, causing hard contact between the falling body and the steel base steel disc.

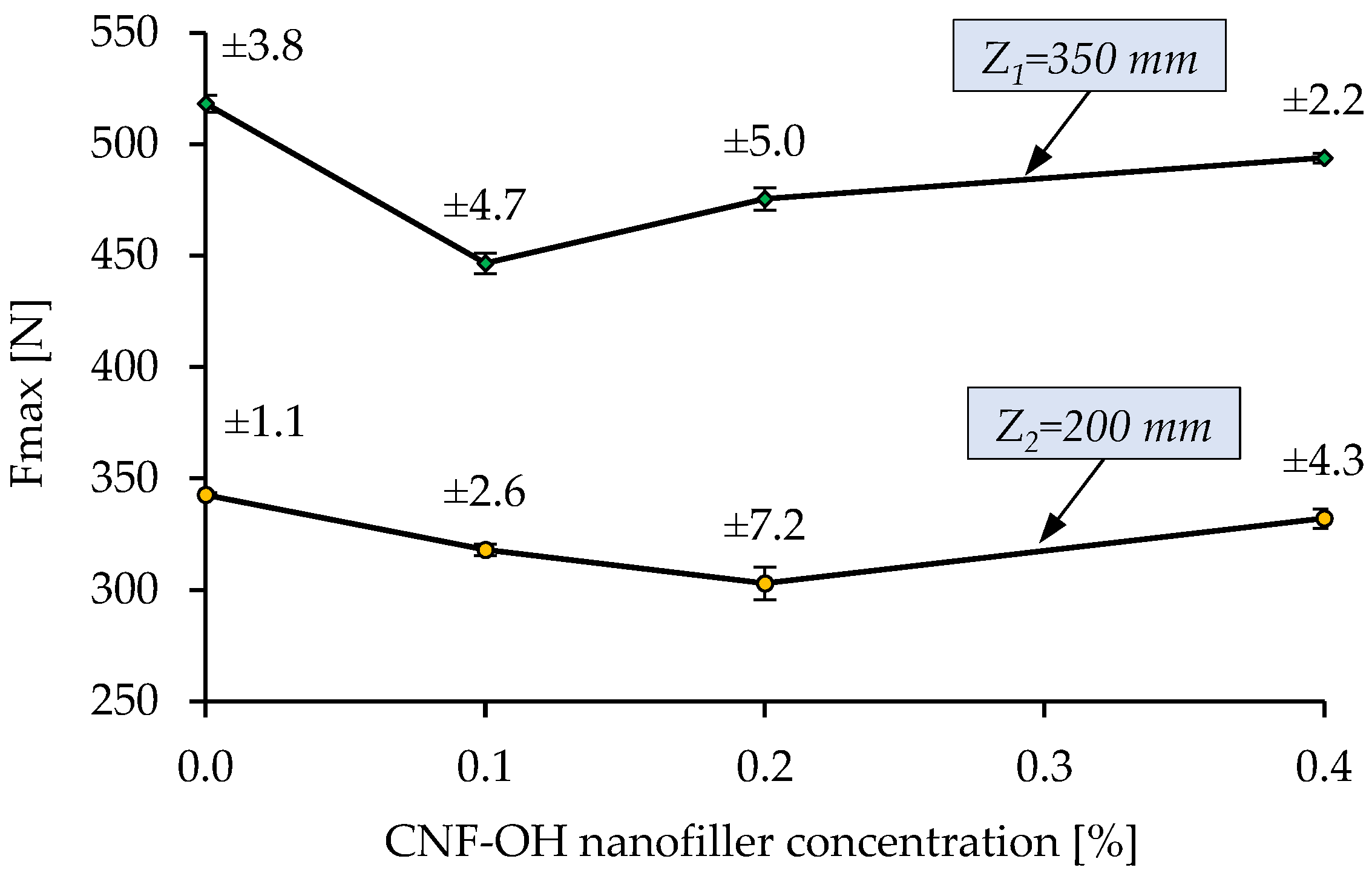

The values of the maximum force with respect to each CNF-OH nanofiller concentration are presented in

Figure 8 in average form (for 3 tests) with standard deviation included. The average standard deviation calculated for maximum force is less than 5 N for

Z1 = 350 mm and less than 8 N for

Z2 = 200 mm. The results presented in this figure show a 15% reduction for 0.1% CNF-OH nanofiller concentration for

Z1= 350 mm and a 7% reduction at

Z2= 200 mm, compared to the force generated when using the base solution. Better performance was observed for

Z2= 200 mm drop height when using 0.2% CNF-OH nanofiller concentration with an important reduction of 14%. Based on these results the optimal nanofiller concentration for maximum damping effect is around 0.1%.

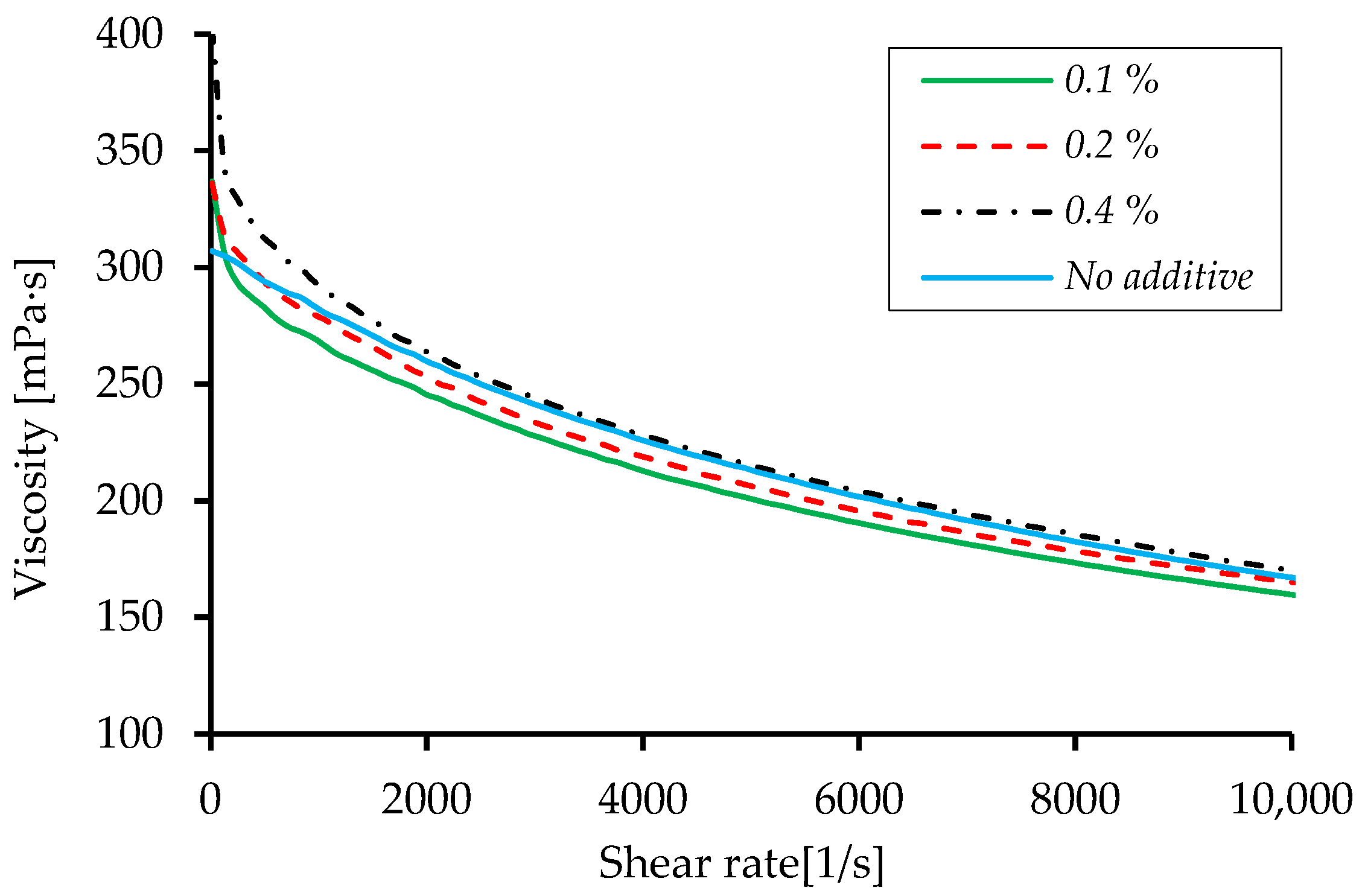

At low to moderate CNF-OH concentrations (0.1–0.2%), the polymer network remains sufficiently open to allow internal flow during impact, enabling effective viscous dissipation. At high shear rates, hydrogen bonds between PVA chains and CNF-OH partially break, reducing viscosity and facilitating energy absorption. However, at higher concentrations (>0.2%), excessive nanofiber entanglement and dense hydrogen-bonded networks create a quasi-gel structure with very high zero-shear viscosity. This restricts fluid mobility within the porous textile, leading to premature densification and reduced damping efficiency despite stronger low-shear resistance. Thus, optimal performance occurs at intermediate concentrations where shear-thinning is maximized without sacrificing flowability.

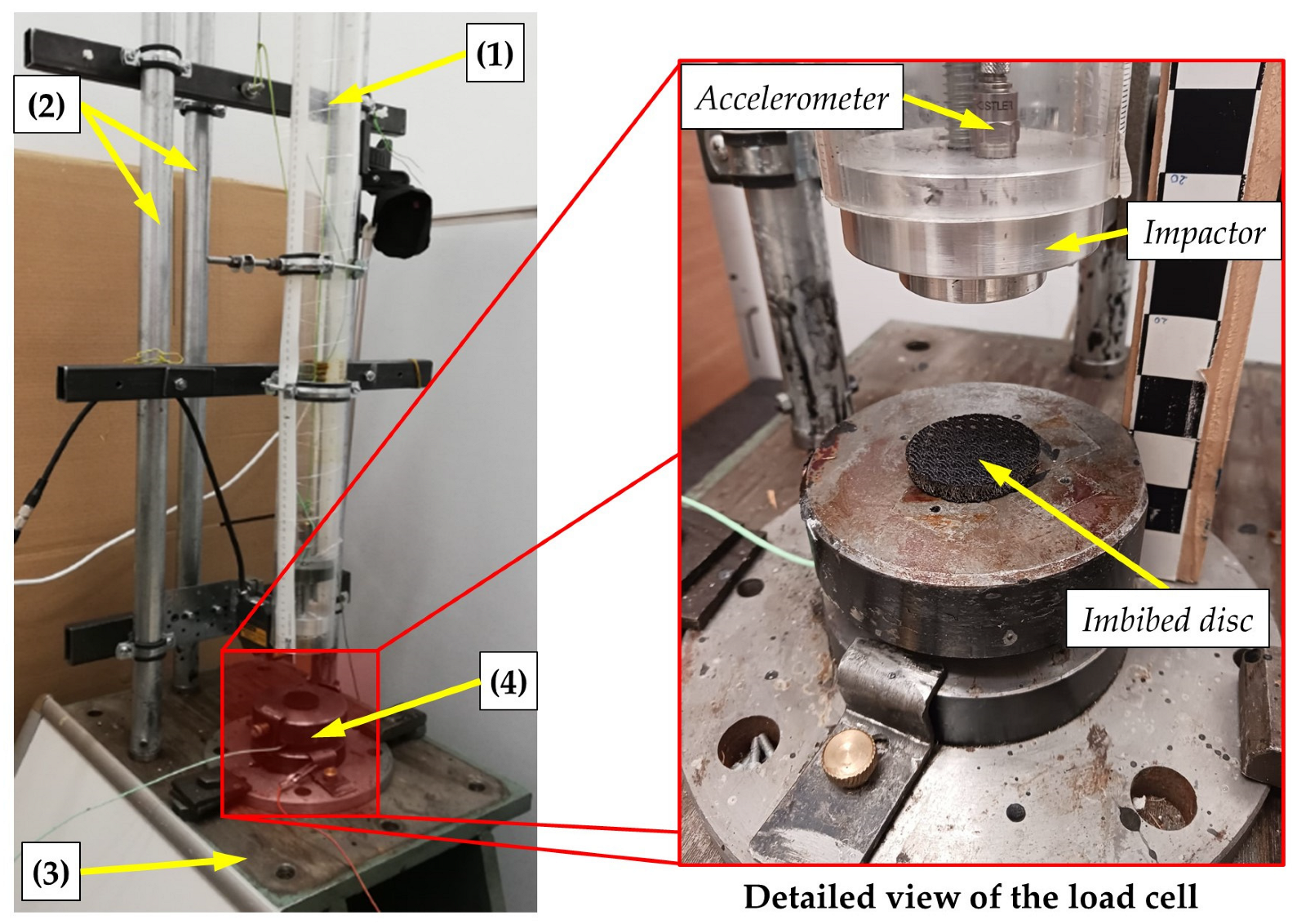

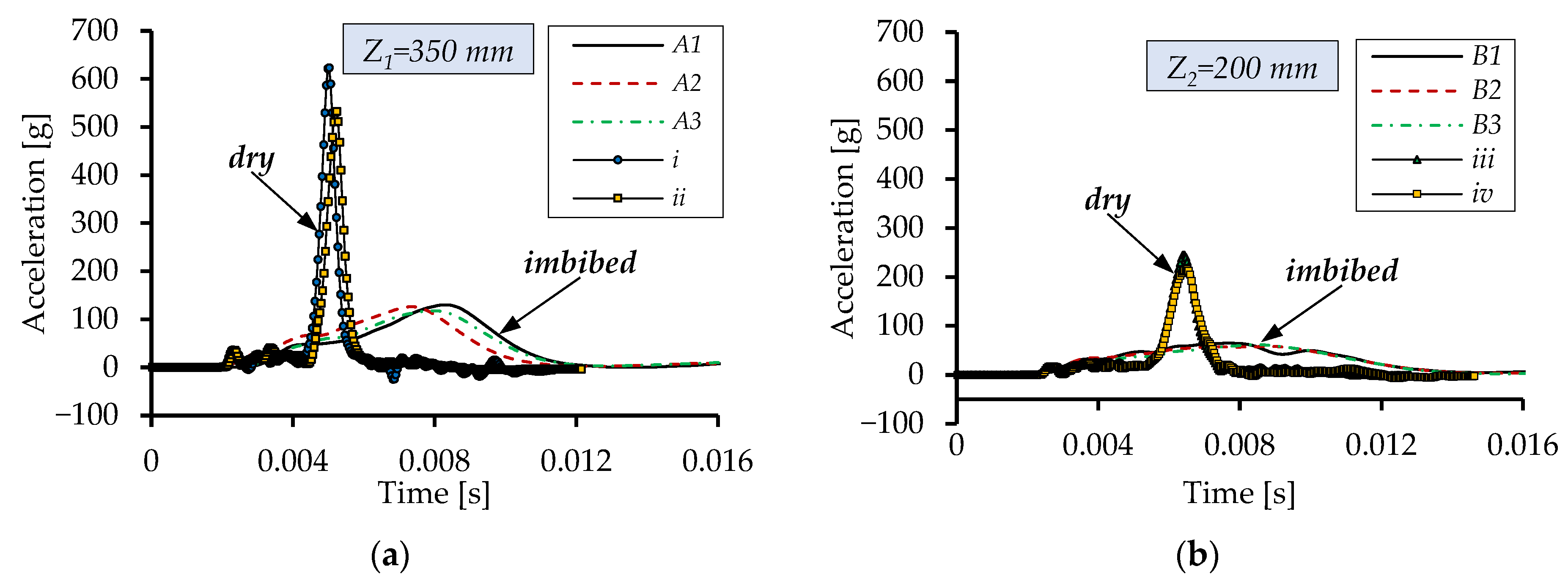

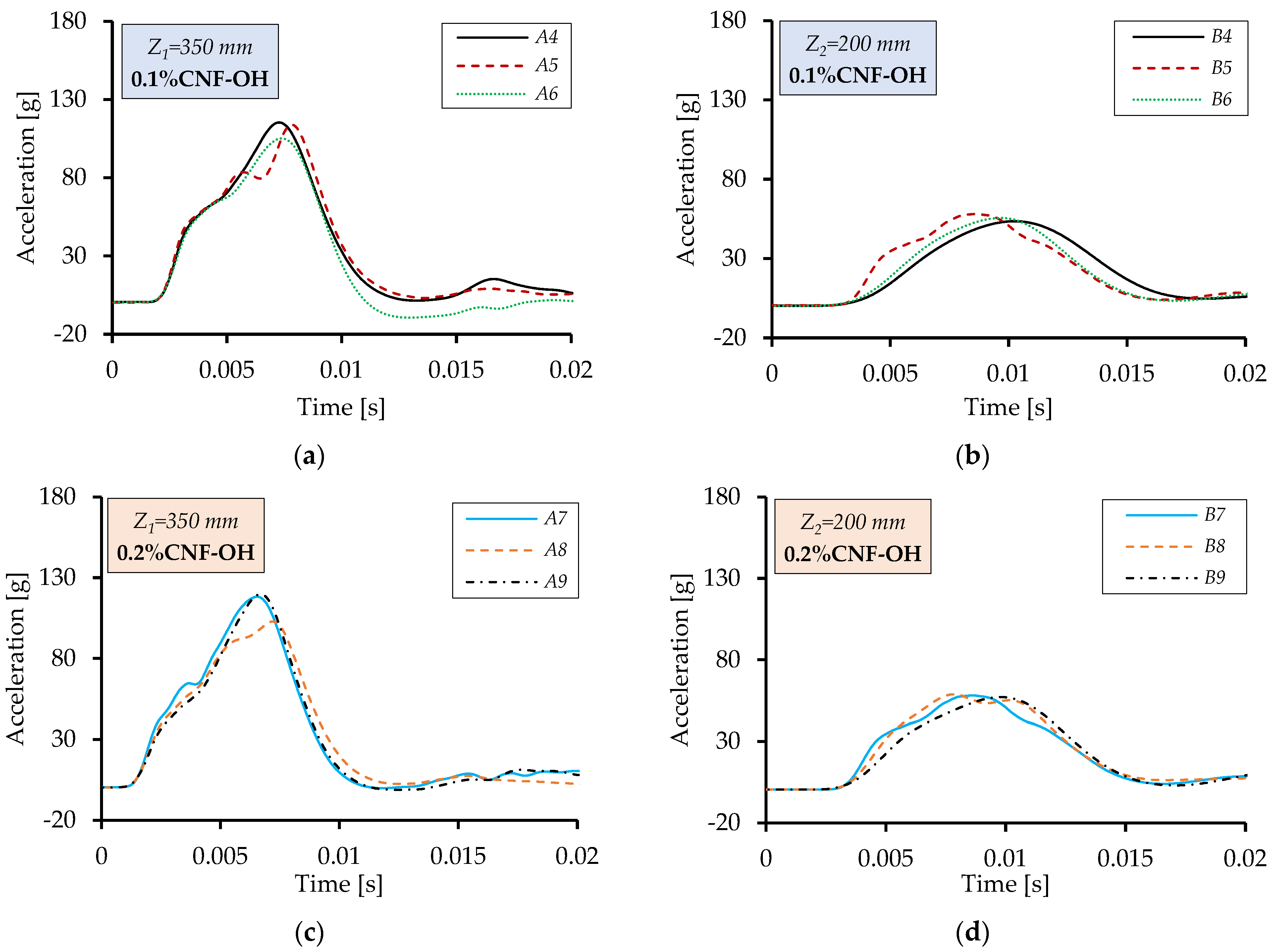

The acceleration during impact was also recorded for the dropping body using the sensor mounted on top. From

Figure 9, which depicts the acceleration variation during impact, one can observe a considerable attenuation when the material is imbibed, relative to tests performed on dry porous material in apparently identical conditions (test

i,

ii,…

iv).

Figure 10 illustrates the acceleration variation for tests with different nanofiller concentrations. The comparison reveals minor differences, as expected given that acceleration measured on the falling body reflects only post-contact displacement.

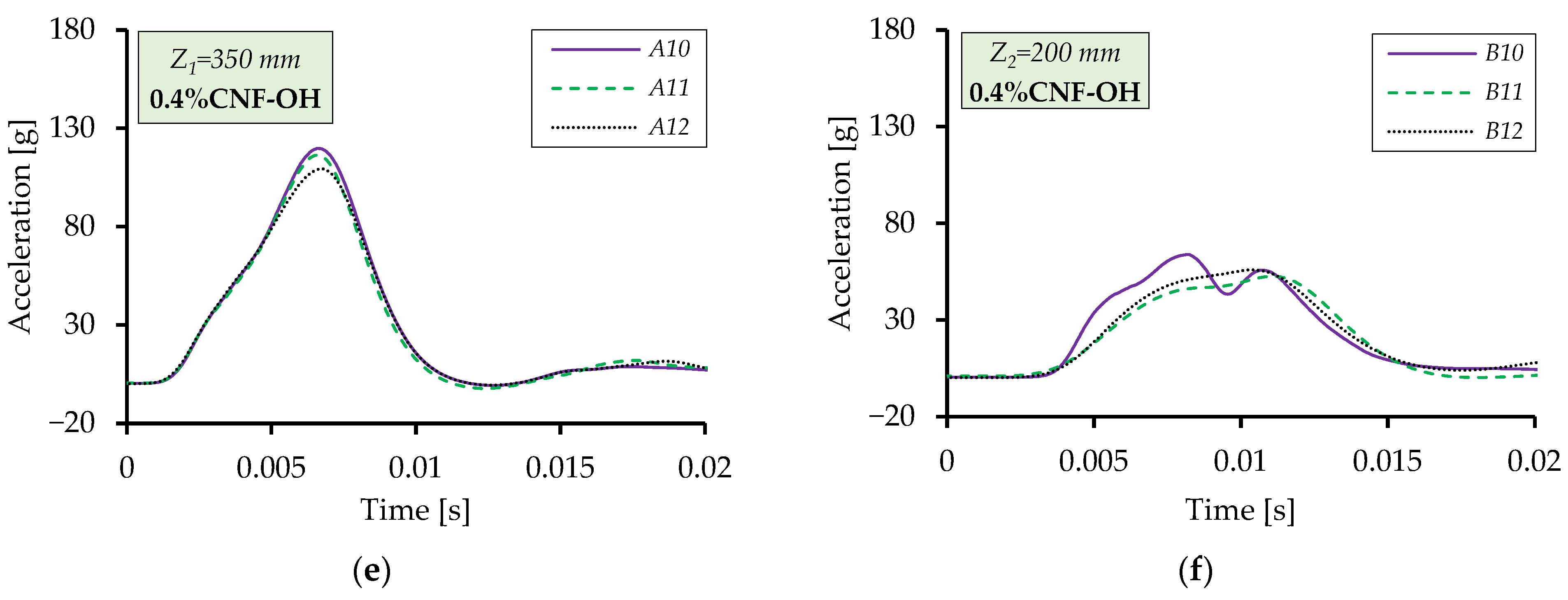

Figure 11 shows representative results for two tests at drop heights of

Z1 = 350 mm and

Z2 = 200 mm. After accounting for the ≈0.2 ms data-acquisition delay, the impact and transmitted forces were almost identical, with a small difference near the peak indicating the existence of the damping mechanism. This discrepancy arises mainly from the accelerometer accuracy and the slight tilting of the impactor. These observations confirm the reliability of the force-transducer and accelerometer data. By integrating the acceleration-time signal using Equations (1) and (2), the impactor’s velocity

v and material deformation

h during compression be obtained. Then, using the initial thickness

h0 of the imbibed sample strain,

ε can also be calculated (Equation (3)).

For the displacement calculation, the contact point is defined at the initial thickness

h0 of the imbibed disk. The impactor descends until the maximum force is reached (

Figure 11) and its velocity falls to zero, after which it rebounds as the velocity increases and the force decreases.

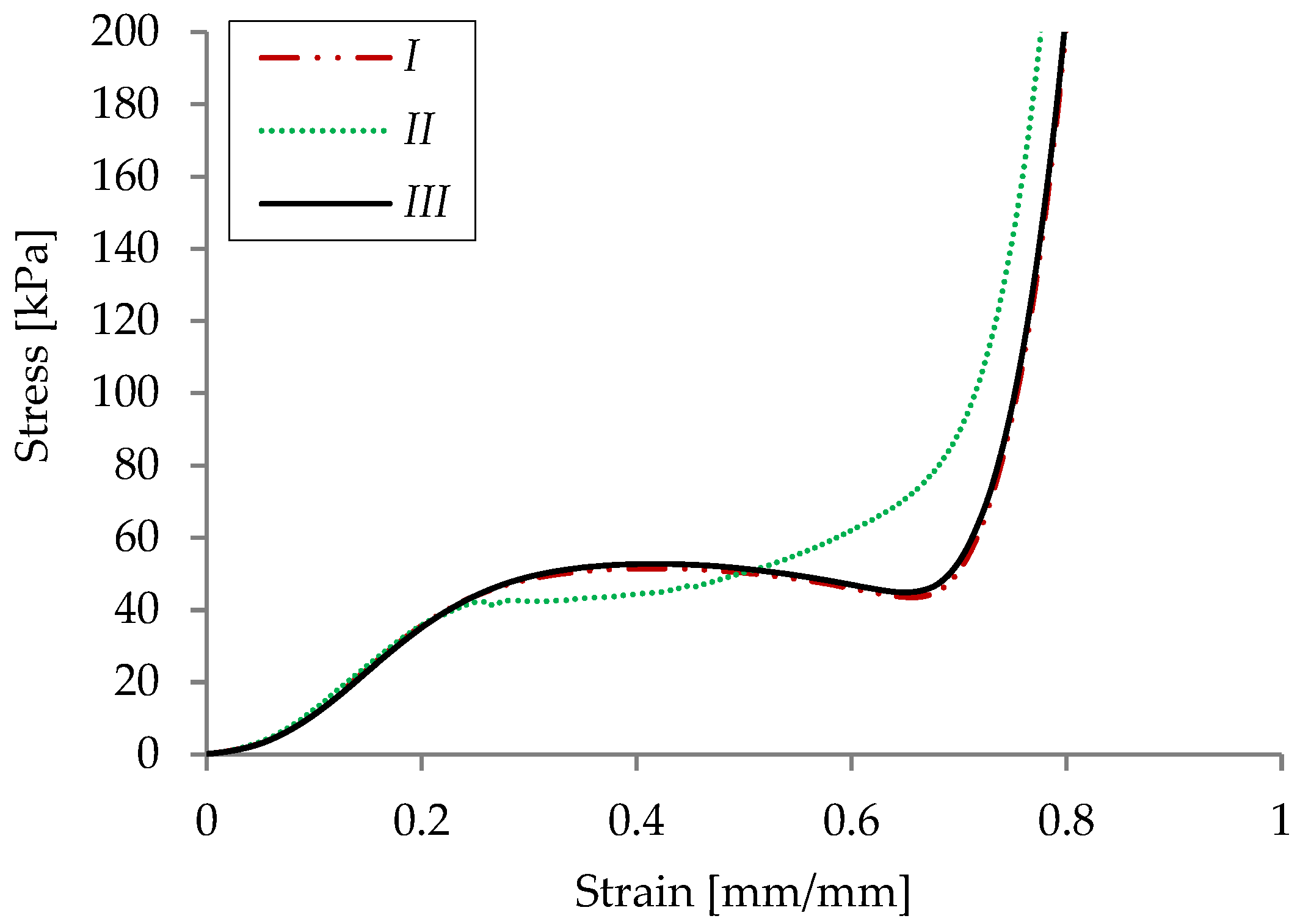

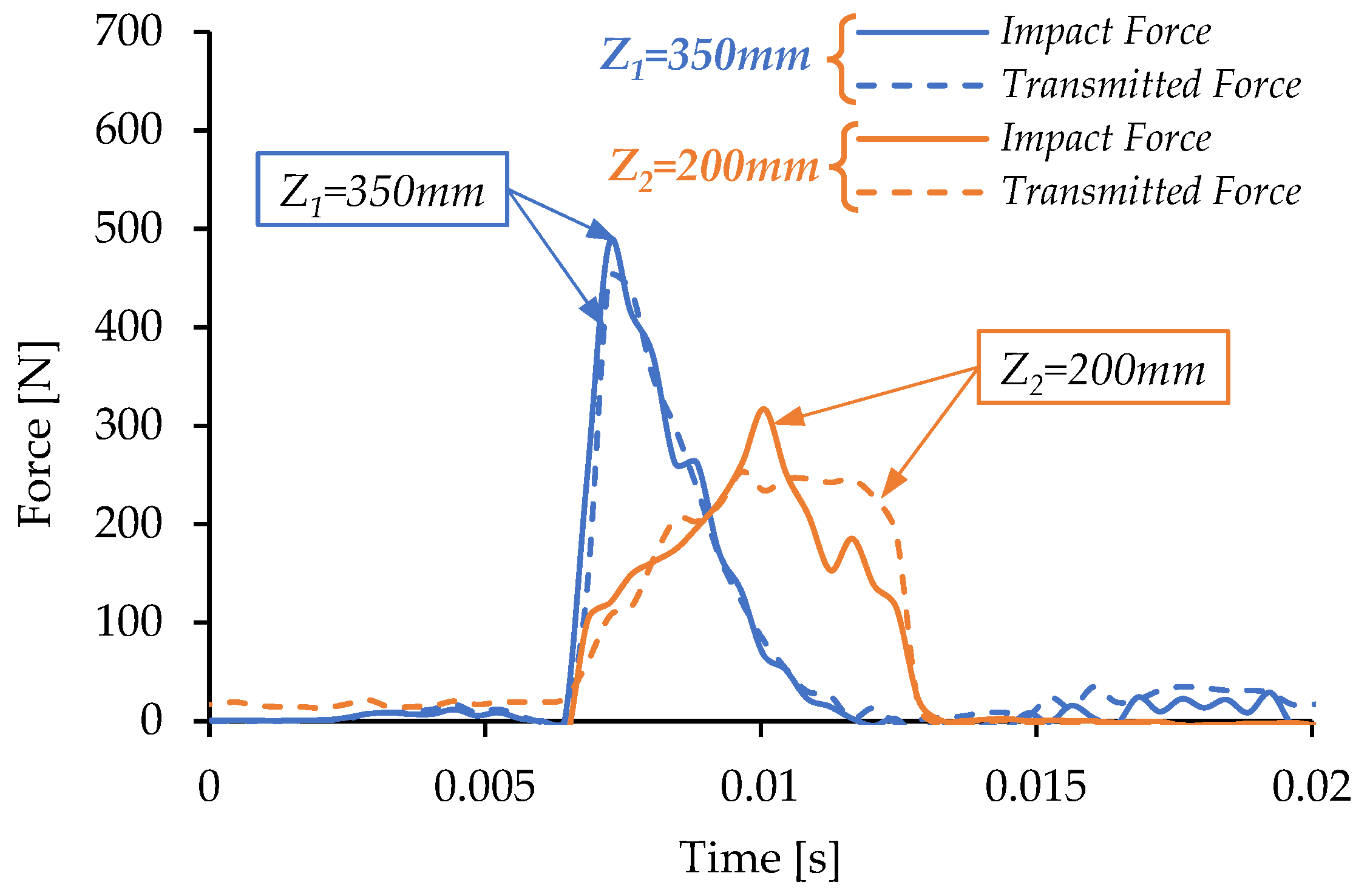

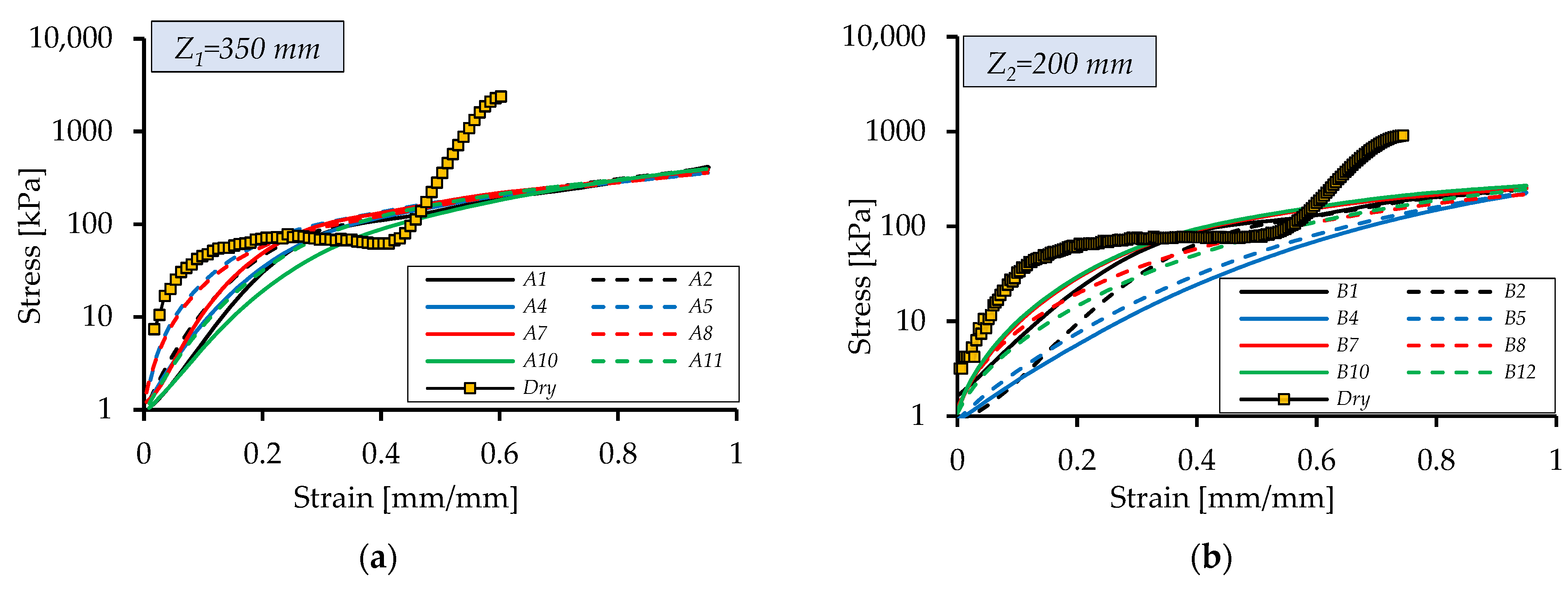

Figure 12a shows the influence of the nanofiller concentration on dynamic stress for

Z1 = 350 mm. At 0.1% and 0.2% nanofiller concentrations, the stress is initially high but drops markedly at large strains compared to the other concentrations. We attribute this to the lower viscosity at high strain, which facilitates fluid flow during compression and enhances impact damping when void volume is low. Based on

Figure 4, the material “solidification” begins a strain of around 0.6–0.7. The curves are limited to 0.95 strain, before the theoretical limit of 1 when there are no voids. Similar trends appear in

Figure 12b for

Z2 = 200 mm, where stresses at low strain are also reduced for the 0.1% and 0.2% nanofiller concentrations. Some inconsistencies arose when integrating acceleration to determine cell deformation during impact, but the errors were quantified and corrected. Some deviations result from slight axial deformation of the loading cell.

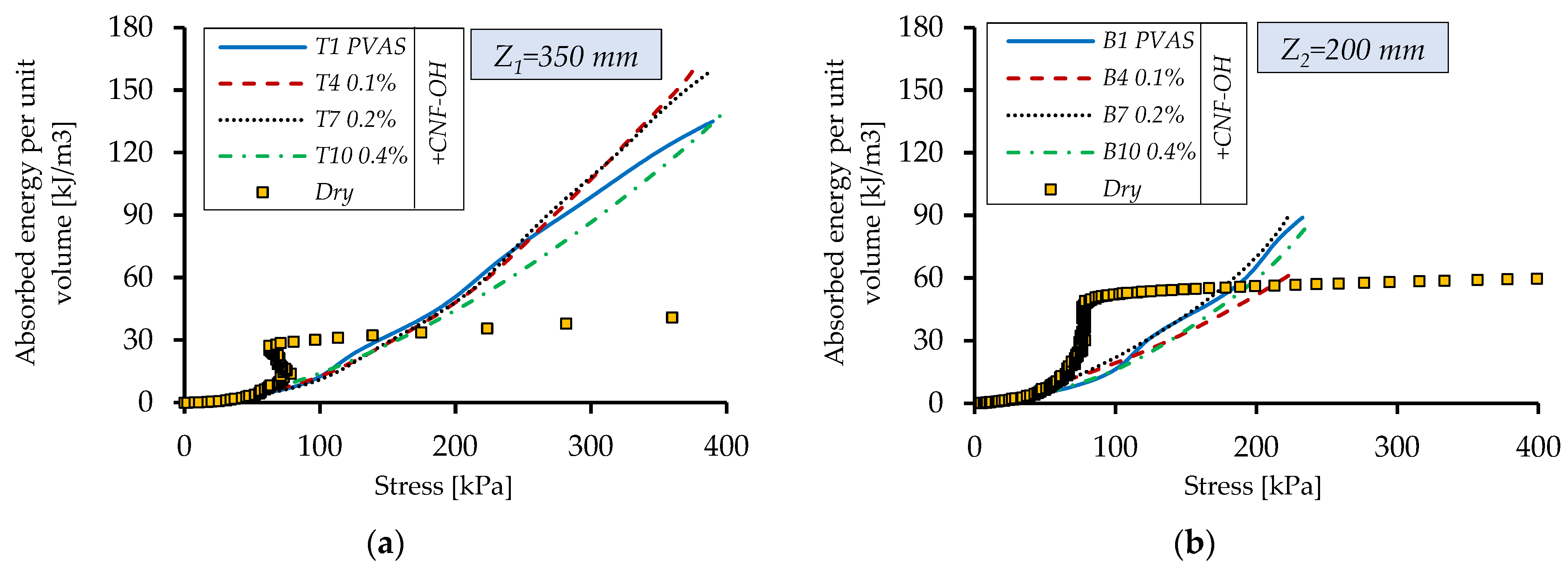

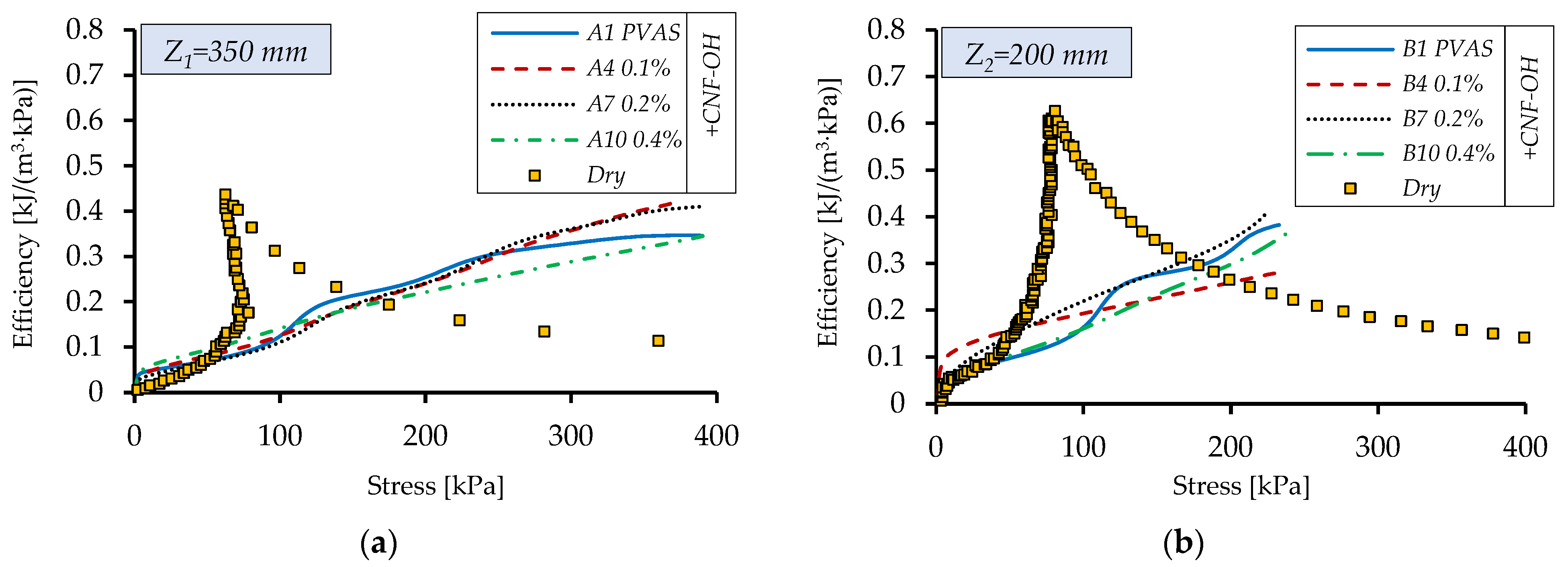

The stress–strain curve provides insight into damping behavior, but its full value emerges when the area under the curve is integrated to determine the absorbed energy per unit volume

E (Equation (4)). An effective impact-damping material should absorb as much energy as possible while minimizing the force transmitted to the protected object. To further assess performance, the efficiency

Eff (Equation (5)) can be used, which is calculated from the absorbed energy [

33]:

Figure 13 shows the specific energy absorption for the base solution and the different nanofiller concentrations, while

Figure 14 presents the corresponding efficiencies. Absorbed energy increases steadily with stress, and in tests where the stress reaches a plateau, a more pronounced rise is observed. Compared with the dry sample, the behavior is fundamentally different. For the dry material, absorbed energy and efficiency rise sharply when stress remains nearly constant in the plateau region (

Figure 12). Once the stress begins to increase again, absorbed energy levels off and efficiency drops, indicating the onset of densification.

In contrast, the presence of the fluid in between the fibers maintains a continuous increase in efficiency despite the reduction in the pore volume. This highlights the ability of the shear-thinning fluid to keep flowing through closing pores with high shear. As the pore volume rapidly decreases, the imbibed fluid is forced through progressively narrower inter-fiber channels, resulting in high shear rates and flow resistance. The response therefore depends strongly on how viscosity varies with shear rate. For shear-thinning fluids such as the PVA–CNF solution, effective viscosity decreases as shear rate increases, enabling sustained fluid flow even as pores close. This radial flow allows viscous dissipation to persist throughout compression and delays the stiffening of the structure. Consequently, the imbibed textile exhibits sustained damping behavior, reduced peak forces and a steadily increasing energy-absorption efficiency at high strains.

Shear-thickening fluids behave oppositely: their viscosity increases sharply with shear rate, causing rapid pressure generation in narrowing pores. This leads to early stiffening and shifts dissipation from viscous flow to fiber-to-fiber friction. Because flow is hindered rather than supported, shear-thickening fluids cannot maintain continuous radial displacement and are therefore poorly suited for highly compressible porous architectures such as 3D spacer textiles.

To better understand the response of the imbibed material, some of the XPHD assumptions are considered valid [

7]: the porous material is homogeneous and isotropic at macroscale, the fluid flow is isothermal, the fluid pressure is considered constant across the thickness of the material (the material is relative thin) and the area of the porous disk is preserved during compaction (the conservation of the solid matrix). The presence of porous structure amplifies the hydrodynamic pressure generated by resistive flow through pores and allows high compressions (orders of millimeters). The force attenuation mechanism is directly influenced by the permeability of the porous material, which depends on porosity and the properties of the imbibed fluid. When the soft (highly compressible) materials are subjected to compression, their porosity decreases, and correspondingly, the permeability reduces as well. In general, the resistance to squeeze increases sharply, generating a progressive stiffness.

A fundamental concept for energy damping based on which shear-thinning fluids flow through deformable porous structure presents good potential. When the size of the pore is reduced, the shear rate will increase with flow velocity, and the specific reduction in viscosity will encourage the radial displacement of fluid. In simpler terms, for the shear-thinning fluid the flow will accelerate easily through the contracting pores, sustaining an even more pronounced damping process.

At high impact velocities, flow speed can be high enough for inertial effects to be comparable with viscous effects. A thorough analysis of these effects can be carried out using Darcy’s law modification proposed by Forchheimer (for inertial effects specific to high flow speeds). A pore-based Reynolds number (

Rep) can be used dependent on the average flow velocity (

um), dynamic viscosity, density (

ρ) of the fluid and a characteristic dimension of the porous material. Many studies try to find the values of the

Rep number when the Darcy flow regime ends and indicate that flow enters a transition regime for values between 1 and 10 [

38,

39]. Depending on the type of the material, the characteristic dimension can be defined using the grain/fiber/sphere mean diameter, permeability or porosity. In this study permeability-based Reynolds was preferred, as in Cicone et al. [

13] and Lupu et al. [

35]:

where

ϕ is the permeability of the yarn and

η is the fluid viscosity.

The Reynolds number (

Re) can be approximated using the theoretical analysis conducted by Cicone et al. [

13], which includes a validation with impact experiments on the same textile material. Considering the experimental conditions used and assuming Newtonian fluid, it was found that

Re < 2.

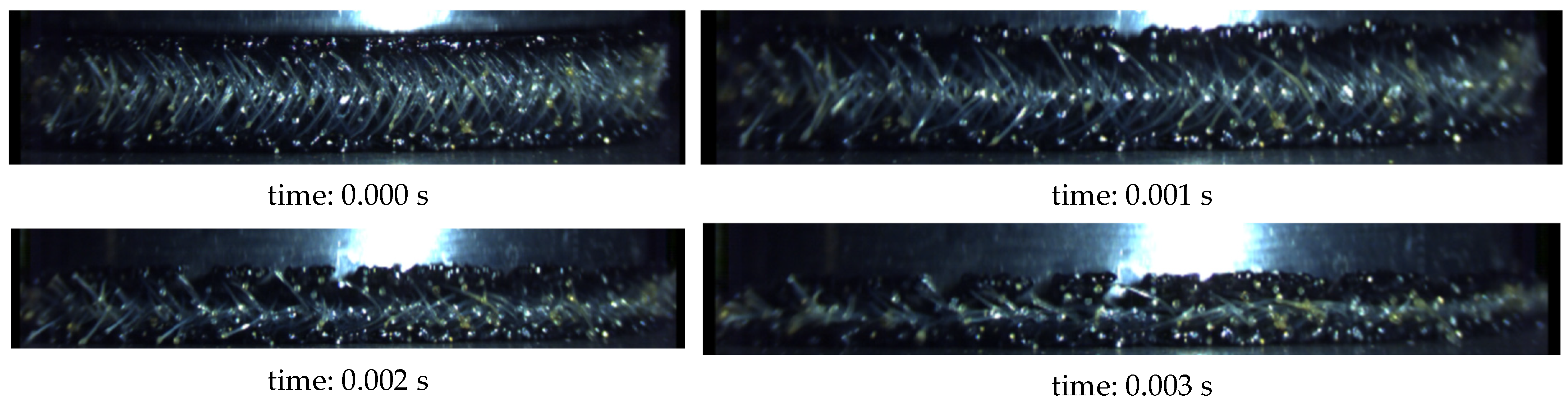

High-speed filming was carried out using a Photron FASTCAM SA-Z camera (Photron, San Diego, CA, USA) to better understand the interaction between the shear-thinning fluid and 3D textile during impact. Direct observation of the fluid–structure interaction inside the porous network was not possible as radial flow prevents clear visualization of the interior during compression. However, the images reveal interfacial instabilities characteristic to immiscible flow between a non-Newtonian fluid and gases when the fluid is squeezed out during compression [

14]. Radial displacement of the fluid withing the porous media produces “fingering” instabilities, ejecting the fluid as small jets into the surrounding air. Partial imbibition at the top surface of the sample can trap air beneath the impactor, further contributing to these instabilities as the fluid is expelled out.

High-speed footage of the dry 3D textile under compression provided insight into how the internal structure deforms (

Figure 15). The structure of the 3D textile is complex, with 3D monofilament shapes that are difficult to quantify or model. The images revealed that during compression, the monofilaments bend, collapse and interact with the outer layers, while the contact points to outer layer remain relatively fixed. Comparison of selected frames indicates that flow between vertical filaments dominates at the start of compression, whereas at later stages the outer layers play an increasingly important role. Their porosity—and thus their permeability—becomes a key parameter governing the compression response.