1. Introduction

Accurate implant impressions are essential for fabricating implant-supported restorations. Digital impressions can be transmitted virtually to the dental technician, streamlining the transfer process and reducing treatment time. Recent studies have shown that the accuracy of digital implant impressions is at least comparable to that of traditional implant impressions [

1]. Accuracy consists of two components—trueness (the closeness of agreement between the average value and the true value) and precision (the closeness of agreement between independent test results), as defined by ISO 5725 [

2].

Intraoral scanner (IOS) technology relies on imaging principles such as triangulation, confocal lasers, and active wavefront sampling to determine the relative position of the implant [

3,

4]. IOSs project a light source—typically a structured light pattern with a defined geometry or a laser beam—onto the dental surfaces and record its deformation with high-resolution cameras; the acquisition software then processes this information into a point cloud that is subsequently triangulated to create a mesh [

5,

6]. This mesh constitutes a direct digital reconstruction of the scanned object [

5,

6]. Wireless IOS models might be expected to exhibit greater surface deviations, as these systems transmit large data volumes via Bluetooth or Wi-Fi. Such wireless transmission can be influenced by signal interference, bandwidth limitations, or connectivity interruptions, which may introduce latency and compromise the integrity of the point cloud [

7,

8]. As a result, the generated 3D mesh may show reduced precision or incomplete surface details [

7,

8].

Digital impression technologies have become fundamental in contemporary implant dentistry; however, the accuracy of IOSs continues to be influenced by several clinical and technical parameters. IOS performance varies due to operator skill, implant placement and position, implant depth and angulation, number of implants, and ambient conditions [

9,

10], as well as mesh holes, stitching, tissue, reliability, and umbrella [

11]. In addition, patient-related scanning errors include humidity, bridges, fuzzy finish lines, and scanability noise errors [

11]. Scan bodies, which are essential components in implant digitization, further contribute to variability, as their material properties, material geometry, and manufacturing tolerances affect both trueness and precision; titanium scan bodies offer high dimensional stability but may require surface treatment due to reflectivity [

12,

13], whereas polyether ether ketone (PEEK) scan bodies are more susceptible to deformation after repeated use or sterilization [

12]. Recent research demonstrates that scan bodies fabricated with unsatisfactory optical properties can lead to clinically relevant inaccuracies, which may result in the misfit of implant-supported restorations and require additional adjustments [

12,

13]. Consequently, considering how scan body design properties interact with scanner optics and software algorithms is necessary for optimizing digital workflows and confirming reliable prosthetic outcomes [

12,

13].

Teeth function as stable geometric reference points that support image stitching during intraoral scanning, which explains why scans of dentate arches generally demonstrate acceptable accuracy [

13,

14,

15]. Nonetheless, studies have reported inconsistent accuracy outcomes when scanning is confined specifically to anterior or posterior segments of a dentate arch [

16,

17]. These discrepancies have been associated with well-documented morphological differences between anterior and posterior teeth that influence alignment performance [

15,

17] as well as the limited span of the scanned area in restricted-region scans [

18,

19]. Moreover, the precision of intraoral scans has been shown to vary according to the scanned segment, with notable differences reported between complete-arch and partial-arch acquisitions in dentate patients [

17,

18,

20]. During intraoral scanning, clinicians tend to concentrate on capturing the implant site, which may inadvertently reduce the accuracy of the remaining portions of the arch. Any discrepancy between the digitally acquired arch and the actual intra oral condition has the potential to influence occlusal contacts and inter-arch relationships, thereby affecting the overall functional outcome [

20,

21].

Three-dimensional analysis methods and metrology-grade 3D analysis software are widely used in dental research to evaluate the accuracy of digital scans of teeth and implant scan bodies (ISBs) [

16,

17]. However, conflicting results have been reported regarding scan accuracy when analyses are limited to the anterior or posterior regions of a dentate arch [

18,

19].

Despite the rapid progress in intraoral scanning technology, the accuracy of digital impressions for posterior single implants compared with contralateral posterior natural teeth has not been clearly evaluated [

11,

12]. Limited findings are available regarding the accuracy outcomes of intraoral scanners in the manufacturing process of single posterior crowns [

22]. Moreover, performing a complete or partial arch scan may affect scan accuracy depending on the region scanned [

23,

24], as clinicians primarily focus on the implant site during scanning, potentially compromising the accuracy of the remaining arch and 3D analysis differences whose scan accuracy can also be crucial even though it may not directly influence the accuracy or fit of an implant-supported crown [

24,

25]. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the effect of different intraoral scanners on the scanning accuracy of posterior single implant scan body (ISB) and posterior single molar tooth (MT) scans using a full-arch scanning strategy. The null hypothesis was that intraoral scanner-dependent differences, including those related to data acquisition and processing algorithms, would not significantly affect the digital accuracy (trueness and precision) of posterior single-implant and contralateral posterior tooth scans obtained with a full-arch scanning strategy.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethics committee approval was not required for this in vitro study. The minimum number required in each group to detect a large effect size (d = 1.5) between two representative IOSs (TRIOS 3 and Primescan) and 3D measurements was set at 9 (α = 0.05; 1 − β = 0.80) for the models [

23]. A similar number of digital scans was performed for each IOS used in this study. Power analysis was performed using G Power 3.9.1 software.

A Frasaco maxillary model (Frasaco ANA-4 AG3) was prepared with a single dental implant scan body (4.0 mm × 9 mm, Megagen ANYRidge–compatible Scan Post, Megagen, Daegu, Republic of Korea) positioned in the upper left molar region. To simulate clinical conditions, the transfer analog was subsequently embedded in self-curing acrylic resin (GC Pattern Resin, GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan) (

Figure 1). The master model was digitized by using an industrial scanner (Solutionix C500, MEDIT Corp., Seoul, Republic of Korea) to generate the reference model standard tessellation language (STL) files.

The master model and the opposing mandibular model were screw-fixed to a phantom head. All digital scans were performed under ideal conditions in a windowless room, with the dental unit light turned off, at an ambient temperature of approximately 23 °C and an illuminance of about 1000 lux, using the Medit i700 (Medit Corp., Seoul, Republic of Korea), TRIOS 3 (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark), and TRIOS 5 (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) intraoral scanners (

Table 1). TRIOS 5 performed automatic software calibration, whereas TRIOS 3 and Medit i700 were recalibrated after every 10 specimens were scanned before data collection. The scans were performed sequentially without repeatedly stopping and resuming, following a standardized manufacturer-recommended strategy in which the occlusal surfaces were scanned first, followed by the buccal and palatal surfaces. The left (implant) side of the model and the right (tooth) side were scanned, respectively. The scans were performed with the scanner positioned as close to the display as possible. Ten consecutive digital scans were conducted by the same experienced operator (M.O.), who has over two years of experience in digital impression making. A 5 min break was taken by the prosthodontist between each scanning session to minimize the risk of fatigue-related errors [

26]. Each model was scanned using a complete-arch strategy, and the procedure was repeated until all scans were completed.

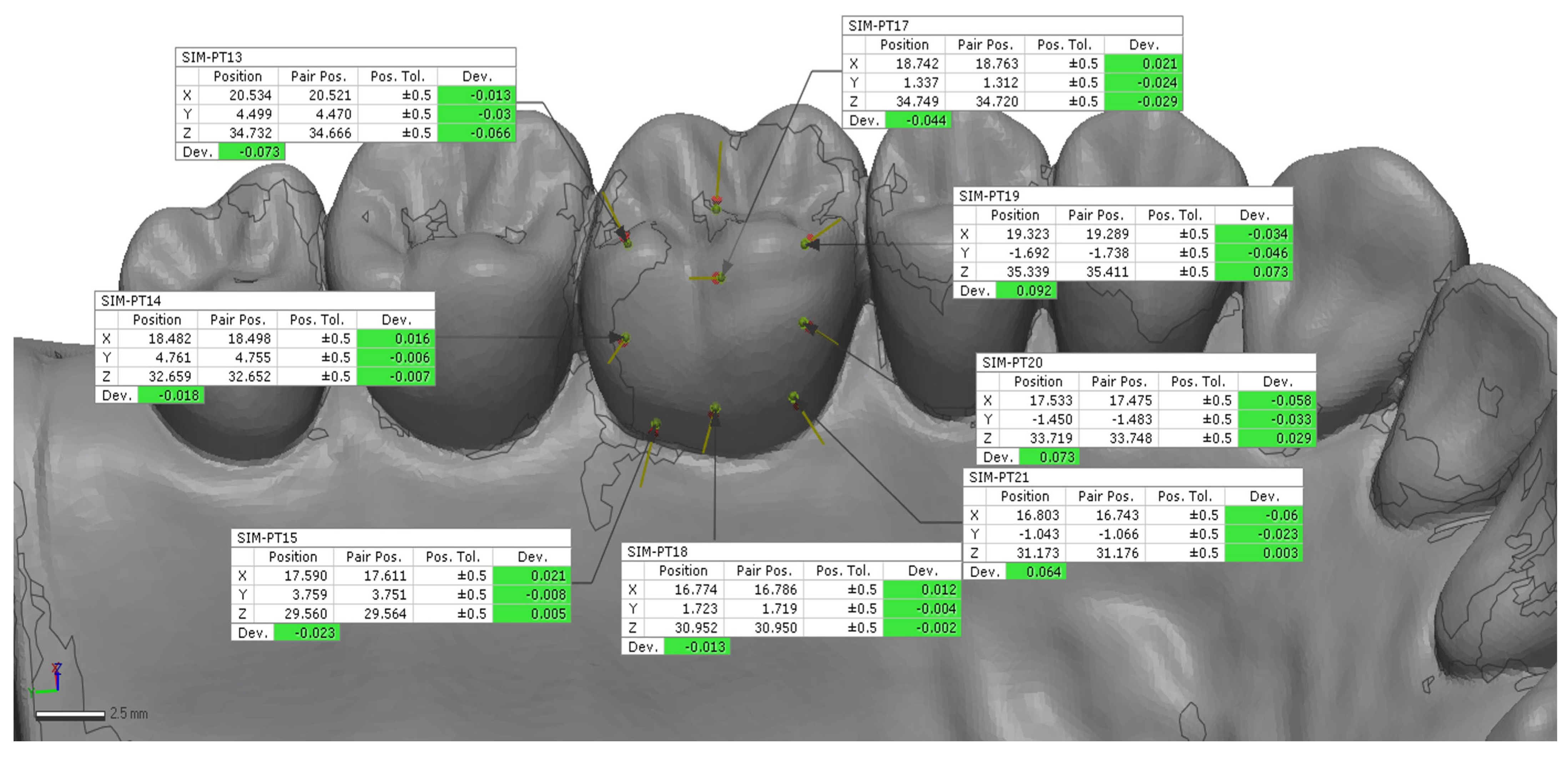

All data were exported in STL format (

Figure 2) and imported into control software (Geomagic Control X 2022; 3D Systems, Rock Hill, SC, USA). Scan alignment was performed by selecting corresponding points within the scanned regions using the best-fit alignment function, which enabled a standardized selection of points across all analyses [

23,

24]. A preliminary rough alignment was applied as an automatic point-based pre-alignment, followed by the use of a local best-fit tool between the reference and test scans. The scan body library file was subsequently aligned to the corresponding scan body mesh using a best-fit algorithm to ensure accurate orientation of the scan body geometry. After superimposition, 12 points on the implant (6 buccal and 6 palatal) (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) and 18 points on the tooth (9 buccal and 9 palatal) (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) were manually selected on the reference model and projected onto each IOS scan, from which 3D linear deviations were automatically calculated and averaged for each scan [

23,

24].

The STL format and its XYZ coordinate system enabled the standardization of all point positions during the analysis. For accuracy evaluation, each test scan was aligned with its corresponding reference scan to determine trueness (test–reference deviation), while the ten test scans within each scanner group were mutually aligned to assess precision (inter-scan variability).

Statistical Analysis

The IBM SPSS Statistics 22 program was used for statistical analyses. The Shapiro–Wilk test was conducted to assess whether the parameters were suitable for normal distribution. A one-way ANOVA and post hoc tests were performed to compare parameters among groups, and the Tukey HSD test was used to identify which group caused the differences. Significance was evaluated at the p < 0.05 level.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the scan accuracy of three IOSs while digitizing one posterior implant and one posterior molar tooth. The null hypothesis was rejected as TRIOS 3 and TRIOS 5 showed statistically different ISB trueness results; TRIOS 5 showed statistically different MT trueness results compared with TRIOS 3 and Medit i700; and Medit i700 showed statistically different MT precision results compared with TRIOS 3 and TRIOS 5.

The results obtained may vary depending on multiple factors; however, it is essential to first consider the differences in scanning technologies. All three devices incorporate different technological features. These results suggest that newer-generation scanners may provide enhanced image stitching and error compensation algorithms that improve surface registration, particularly in complex posterior regions. These results are consistent with previous reports that demonstrated improved digital accuracy in newer IOS generations due to algorithmic and hardware optimization [

25,

26].

Marques et al. (2022) [

24] investigated the effects of scanned areas and operator-related factors on scan accuracy in a dentate arch during anterior single-implant scanning of a dentate model. Three operators performed 10 complete-arch scans and 10 partial-arch scans using an intraoral scanner (TRIOS 3). Trueness and precision were higher at the anterior site than at the posterior for both complete- and partial-arch scans (

p ≤ 0.022). Operator influence on complete-arch scan precision was not significant, whereas partial-arch scans showed limited operator-related differences. Partial-arch scans demonstrated higher trueness than complete-arch scans, while precision values were comparable. Overall accuracy was greater in the anterior region, with only a minor operator effect. In the present study, only a posterior implant was scanned, and complete-arch scans were performed by a single operator.

In a recent study, Dinçer et al. (2024) compared the wireless TRIOS 4 and the wired Neoscan 2000 intraoral scanners and found that both devices provided largely similar scanning accuracy when capturing a combined healing abutment-scan body (CHA-SB) system composed of PEEK and acrylic resin compositions [

7]. In a different study, Jain et al. (2024) compared the accuracy of TRIOS 5 (wireless), Medit i700, and Primescan, and TRIOS 5 displayed the lowest deviation values, followed by Medit i700 and Primescan with a one-piece metal abutment system [

26].

Sombun et al. (2023) evaluated three battery level ranges (30%, 31–60%, and 61–100%) and demonstrated that battery level did not affect the scan accuracy of two wireless IOSs, including TRIOS 3 and TRIOS 4, when scanning a maxillary cast with four metal spheres, whereas high battery levels resulted in shorter scanning times and a reduced number of captured 3D images, leading to lower storage space requirements [

8]. In the present study, TRIOS 5 (wireless) exhibited higher trueness than TRIOS 3 with a 1-piece titanium scan body, whereas it showed lower trueness for molar scans. TRIOS 5 showed more successful trueness results than TRIOS 3 scanners for ISB. All of the scanners used in this study served similar precision results, showing non-independence of the operator.

Sicilia et al. (2024) emphasized that scan-body geometry and supramucosal height considerably affect the capture of 3D data, especially in angled posterior implants [

27]. Our results demonstrated similar tendencies, with accuracy decreasing as scanning complexity increased in the posterior region. The influence of scan-body design and modifications [

28,

29] and reflective behavior on the optical triangulation process may partially explain these discrepancies between tooth and implant scans [

30]. As digital scanning systems advance, scannable abutments and a range of designs provided by each company become available. In recent years, nearly all implant manufacturers have introduced scannable impression copings. The commercial ISB designs differ in terms of materials, sizes, surface geometries, reconfigurability, software/scanner compatibility, and cost variations [

31]. The scan body, having a narrower upper surface area compared to the occlusal surfaces of the molars, may have facilitated the proper alignment of scans at the posterior site and increased the deviation among different intraoral scanners, and a Ti-6AL-4V-ELI Grade 5 (sandblasting with aluminum oxide) scan body was used for this study.

Moon et al. (2020) [

20] reported that the accumulation of stitching errors is more pronounced in the distal segments during complete-arch scanning. In the present study, the posterior single implant scans showed higher deviation values than the contralateral tooth scans, supporting the notion that optical capturing in the distal region is less stable. This may be attributed to the geometry of the scan body, reflective surface characteristics, and reduced scanner visibility in the posterior area.

The fit of tooth-supported and implant-supported prostheses is a critical factor and directly affected by digital impression and its accuracy. In the literature, previous studies have demonstrated that variations in surface morphology, reflectivity, and geometric reference points can affect the trueness and precision of intraoral scans. Therefore, differences in optical behavior and landmark distribution must be taken into account. Siadat et al. (2024) found that tooth-based digital impressions tend to serve slightly lower root mean square (RMS) deviations compared with implant-based models [

30], and Fathi et al. (2023) reported that the tooth–implant impression techniques demonstrated similar accuracy results [

32]. In the present study, the molar tooth was left unprepared to represent an intact enamel surface, differing from previous studies that examined prepared teeth. This unprepared morphology may have provided differences for image matching, but also introduced light scattering, affecting overall trueness [

9]. Recent evidence indicates that the surface characteristics of dental tissues and the scanning environment can affect accuracy.

The literature reports that the clinically acceptable error level for digital measurement accuracy in all techniques and scenarios is between 30 and 150 µm [

33,

34], and a recent systematic review reported that vertical misfits up to 160 µm and horizontal misfits up to 150 µm did not lead to complications in implant-supported restorations [

35]. In the present study, when the 3D trueness and precision results were within the range of 0–40 µm, these values were considered clinically small and negligible. Based on the findings of this study, it is clinically relevant, given that error margins can accumulate throughout the digital workflow from impression taking to the manufacturing process. Therefore, even when the deviations are below 150 µm, the results should not be regarded as clinically insignificant based solely on this criterion. The higher standard deviations observed in several groups (e.g., TRIOS 5 MT ± 30 µm) primarily reflect increased digital measurement variability rather than a strict technical limitation of the scanner.

In a previous study, Lee et al. (2021) [

36] investigated the trueness of digital implant impressions according to implant angulation and scan body material using the CS3600 (Carestream Dental), TRIOS 3 (3Shape) and Primescan (Sirona Dental Systems) intraoral scanners. The RMS values for the titanium scan body group (150.5 ± 45.4 to 294.1 ± 110.4 µm) were significantly lower than those for the polyether ether ketone scan body group (264.0 ± 76.5 to 359.4 ± 48.3 µm) (

p < 0.001). In a different study, Sun et al. (2025) [

37] found that the accuracy of titanium scanning bodies demonstrated superior spatial positioning accuracy compared with PEEK under the conditions of the study in a 3D printed model for TRIOS 3 (3Shape). In the scenario most comparable to our study, Ti showed a 180 ± 30 μm trueness deviation, and PEEK showed a 190 ± 15 μm trueness deviation; moreover, precision worsened as Ti showed a 70 ± 20 μm precision deviation and PEEK showed a 110 ± 20 μm precision deviation. Unlike that study, Frasaco jaw models were used in the present study, and a single titanium implant was evaluated instead of two adjacent implants, as in the scenario most comparable to our study. Moreover, the results of the present study demonstrated more favorable accuracy and precision values.

Fathi et al. scanned a molar implant scan body and a prepared premolar tooth in a phantom model, similar to the design of the present study, using the Omnicam (CEREC) intraoral scanner, and evaluated digital accuracy. Unlike our study, the molar implant scan body and the prepared tooth were positioned adjacent to each other. According to the results of that study, the scanning accuracy of the implant region was 105 ± 11.3 μm, whereas the scanning accuracy of the prepared tooth was 484.3 ± 16.7 μm. The 3D deviation values in that study were higher, and the simultaneous tooth–implant impression techniques compared showed comparable accuracy, with no significant differences [

32]. In our study, the IOSs differed, and unlike that study, multiple intraoral scanners were compared.

Liu et al. (2024) [

22] evaluated a total of 70 mandibular posterior teeth requiring single-crown restorations, which were randomly assigned to either intraoral scanning or conventional impression-taking, after which the resulting casts were scanned in the laboratory as part of a parallel-group randomized controlled trial. The mean marginal fit achieved with intraoral scanning (57.94 ± 22.51 µm) was superior to that obtained with diagnostic cast scanning (82.98 ± 21.72 µm) using the TRIOS (3Shape) scanner. Although a comparison between conventional and digital impressions was not performed in our study, deviation values similar to those obtained with TRIOS (3Shape) scans in that study were achieved.

In a previous study, Lee et al. (2021) [

38] investigated the trueness of digital implant impressions according to the orientation of the implant scan body and the scanning method. With the flat surface of the implant scan body facing either the buccal or proximal direction, scans were obtained using one tabletop scanner (T500, Medit, Seoul, Republic of Korea) and three intraoral scanners (TRIOS 3, 3ShapeCopenhagen, Denmark; CS3600, Carestream Dental, Atlanta, GA, USA, and i500, Medit). The RMS was lower in the buccal groups (28.15 ± 8.87 µm, mean ± SD) than in the proximal groups (31.94 ± 8.95 µm;

p = 0.031), and lower in the full-scan groups (27.92 ± 10.80 µm) than in the partial-scan groups (32.16 ± 6.35 µm;

p = 0.016). When a tabletop scanner was used, trueness was higher when the ISB was connected buccally (14.34 ± 0.89 µm) compared with proximal connection (29.35 ± 1.15 µm;

p < 0.001). In the present study, the flat surface of the implant scan body faced the buccal direction.

In a previous in vitro study, Moura et al. (2025) [

39] evaluated the effects of margin preparation on dentin and enamel using different finishing protocols under dry and wet storage conditions. Enamel specimens demonstrated significantly higher precision (15.7 µm) than dentin specimens (24.3 µm) (

p < 0.001). Moreover, the storage environment significantly influenced scanning accuracy (

p < 0.001), with dentin exhibiting greater precision and trueness under dry conditions (18.3 µm) compared with wet conditions (37.3 µm) (

p < 0.001). These findings suggest that substrate type and moisture conditions may play a critical role in digital scanning accuracy. In the present study, unprepared tooth structures were simulated; however, partial or full tooth preparations may be associated with altered surface characteristics and moisture levels. Therefore, further studies are required to investigate the influence of different preparation designs and moisture conditions on scanning accuracy.

The main limitation of this in vitro study is the use of a static model that does not fully replicate clinical intraoral conditions; however, controlled settings were necessary to ensure reproducibility and isolate device-related variables. Performing all scans with a single operator constitutes another methodological limitation; although this approach eliminates inter-operator variability and ensures consistency, it may, to some extent, restrict the generalizability of the findings. Along with this, considering that higher precision outcomes may indicate a greater influence of operator-related errors, the use of a single operator may be considered to provide more reliable results.

One limitation of this study is that the implant scan body was positioned only in the left posterior region. Although this selection reflects common clinical access conditions encountered during intraoral scanning, particularly in right-handed operator setups, it may limit the generalizability of the findings to other clinical scenarios, such as different operator handedness or alternative implant locations.

Future research should include in vivo assessments comparing IOS accuracy in various clinical conditions. Molar dental preparation was not implemented in this study; however, results might have changed if it had been applied according to these studies. Different scenarios are needed to investigate both implant and tooth digital accuracy. Studies indicate that it is important to consider the variable digital accuracy in dental arches that contain both implant-supported materials and tooth-supported tissues. Further research is needed on impression accuracy in clinical scenarios involving both implant-supported and tooth-supported cases, including the involvement of multiple operators, in vivo conditions, and different scan bodies and clinical scenarios. The need to analyze the same study using different alignments is also one of the limitations.

This study highlights the differences between implant scan bodies and molar structures; further research on this topic is warranted. This contributes to reducing potential misfits, improving occlusal and proximal contact accuracy, and ultimately enhancing the long-term success of digitally fabricated prostheses.