4. Statistical Analyses of Odour Nuisance

4.1. Preparing Data for Statistical Analysis

The data preparation procedure included format conversion and validation, handling of missing values, and modification of categorical variables. Recent advances in environmental data analysis emphasise the importance of robust preprocessing, dimensionality reduction and flexible regression frameworks when analysing complex, non-linear and highly variable datasets typical of odour monitoring studies [

32,

33,

34]. Generalised additive models and modern chemometric techniques have been shown to outperform classical linear approaches when threshold effects and non-linear responses are present. The odour intensity was categorised as an ordinal variable, and the measurement dates were converted into seasonal variables, corresponding to the four seasons. A complete analysis of the dataset was conducted, excluding observations with significant missing values. A log1p(x) = log(x + 1) transformation was used for highly skewed concentration distributions (H

2S, NH

3, VOC, CH

3SH). All quantitative variables were standardised with the z-score approach, facilitating their comparability and accurate interpretation in multivariate analyses. The quality of the data was assessed using descriptive analyses and distribution visualisations. Seasonal categorisation was applied to reflect consistent meteorological differences, particularly in air temperature and atmospheric stability, which influence odour emission and dispersion. The seasonal grouping was therefore used as a pragmatic framework for interpreting broad climatic contrasts rather than as a fine-scale meteorological classification.

Missing values were handled using a complete-case approach for multivariate analyses, ensuring consistency across models. The proportion of excluded observations was low and did not exceed a few percent of the total dataset. Observations with missing key variables were excluded only when necessary. Highly skewed chemical concentration data were log-transformed using log1p(x) to stabilise variance. All continuous variables were subsequently standardised using z-score transformation (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1) prior to multivariate analyses, ensuring comparability among predictors and preventing scale dominance.

Explicit spatial autocorrelation analysis was not performed because receptor locations were not fixed in space and were dynamically adjusted according to prevailing wind direction and operational conditions. Spatial dependency was partially accounted for using mixed-effects models with random effects for measurement level and location context, which mitigated potential clustering effects.

Model selection was based on a combination of theoretical relevance, goodness-of-fit metrics (AIC, R2 or pseudo-R2), and diagnostic checks rather than exhaustive comparison of all possible model variants. Only models that were both statistically robust and interpretable were retained for presentation. Explicit interaction terms between meteorological and chemical variables were not systematically explored in parametric models to avoid overparameterisation and loss of interpretability. Non-linear and context-dependent effects were instead captured using additive and ordinal modelling frameworks, which are better suited to complex environmental datasets.

4.2. Relationships Between Parameters

Spearman’s rank correlation matrix was used to examine correlations among quantitative variables. In cases of significant skewness, the correlations were re-evaluated after a log1p(x) transformation. The Benjamini–Hochberg correction was used to assess the significance of the coefficients and mitigate type I errors in multiple comparisons. The findings are shown as correlation matrices and heatmaps, indicating link strength as weak (ρ < 0.3), moderate (0.3–0.6), or high (>0.6).

4.3. Analysis of Spatial and Contextual Variation

The Mann–Whitney test (for two-group comparisons) and the Kruskal–Wallis test (for multi-level comparisons) were used to compare measurements taken inside and outside the object, between measurement levels, and between seasons. When the assumptions of normality (Shapiro–Wilk) and homogeneity of variance (Levene) were satisfied, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed, with the η2 coefficient presented as an indicator of effect size. Seasonality was evaluated by categorising the four seasons based on the registration dates.

4.4. Principal Component Analysis and Construction of a Synthetic Odour Index (SOI)

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used for dimensionality reduction and to discern shared patterns of variability across chemical, olfactometric, and meteorological variables. The study included H

2S, NH

3, VOC concentrations, the aggregate of CH

3SH, olfactometric values (c

od_NR, c

od_SM), and ambient characteristics (air temperature, air humidity). The quantity of significant components was determined using Kaiser’s criteria (eigenvalues greater than 1), the scree plot, and parallel analysis. The first component (PC1) represents the overall gradient of odour strength, while the subsequent component (PC2) pertains to environmental factors, primarily associated with air humidity and air temperature. Variable contributions were assessed by component loadings and mapping quality coefficients (cos

2). The Synthetic Odour Index (SOI) is defined as the normalised (0–100) value of the first principal component (PC1) derived from a matrix of chemical (H

2S, NH

3, VOC, CH

3SH), olfactometric (D/T from Nasal Ranger and SM-100), and meteorological (air temperature, relative air humidity) variables. PC1 was linearly scaled to the range of [0, 100] and used as a composite metric for odour intensity in further models. The transformation was performed according to the following equation:

where

This scaling preserves the relative distances between observations while providing an intuitive, dimensionless index suitable for interpretation and further modelling.

4.5. Classical and Logistic Regression Models

4.5.1. Linear Regression (LM)

Linear regression models were used to describe the relationship between odour perception and environmental variables:

where

is the Synthetic Odour Index,

—is the air temperature,

—is the relative air humidity,

—is the random component. Additionally, a model explaining the SOI with chemical and meteorological variables was estimated:

For predictors with skewed distributions, a log1p(x) transformation was applied. To mitigate the impact of heteroskedasticity, robust estimation (HC3) was used. Collinearity was assessed using the VIF coefficient.

4.5.2. Logistic Regression

Logistic regression was used for the binomial variable defining the probability of high odour intensity (≥3):

with LASSO regularisation; the parameter λ was chosen using 10-fold cross-validation.

The regularisation parameter λ was selected using 10-fold cross-validation, resulting in an optimal value of λ = 0.034, which minimised the cross-validated deviance.

4.6. Ordered and Additive Models

4.6.1. Ordered Models (CLM, CLMM)

For the perceptual variable representing odour intensity (scale of 1–5), ordinal models with a logit link function were used:

where

are the category thresholds,

are chemical and meteorological predictors,

—is the random effect of the measurement level. The proportional odds assumption was verified; marginal effects were determined using the emmeans package.

4.6.2. Additive Models (GAM, VGAM)

Generalised additive models were used to capture non-linearity:

where

are smoothing functions (penalised splines). The degree of smoothing was controlled by the effective degrees of freedom (edf) and AIC. For ordinal data, analogous models were implemented within the VGAM framework, both with and without the proportional odds assumption. For the CLMM, the proportional odds assumption was formally tested and met, supporting the validity of the ordinal regression framework.

4.7. Model Validation and Diagnostics

The validation occurred in two phases. Initially, grouped cross-validation was used. The measurement level served as the blocking unit, preventing information leakage between observations. Subsequently, external validation (holdout) was used, designating one measurement level as the test set. For regression models, R2, RMSE, and MAE were provided; for classification and ordinal models, model performance was evaluated using established accuracy and discrimination metrics. The diagnostics for linear models depended on residual analysis (Shapiro–Wilk, Breusch–Pagan), variance inflation factor (VIF) coefficients, and impact metrics (Cook). Model diagnostics for linear, ordinal, and additive models were conducted using standard residual- and assumption-based procedures appropriate for each modelling framework.

The selection of statistical models was guided by the structure of the data and the nature of the response variables. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to reduce dimensionality and identify dominant patterns among correlated chemical, sensory, and meteorological variables. Generalised additive models (GAM/VGAM) were selected to capture non-linear relationships commonly observed in odour perception phenomena. Cumulative link mixed models (CLMM) were employed to account for the ordinal nature of odour intensity ratings and random effects related to measurement location. Logistic regression was used to estimate the probability of high odour nuisance events, allowing for interpretable threshold-based predictions.

Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the statistical models applied, including their formulation, link functions, and validation procedures.

External validation was intentionally limited to a single measurement level due to the structure of the field campaign and the limited number of independent high-intensity odour episodes. The applied validation strategy therefore reflects a conservative and realistic assessment of model performance under real operational conditions rather than an attempt at broad predictive generalisation. Model calibration was assessed using standard diagnostic procedures appropriate for each modelling framework. Calibration diagnostics indicated acceptable agreement between observed and predicted response distributions, with no systematic bias detected across odour intensity levels.

4.8. Odour Activity Value (OAV)

The Odour Activity Value (OAV) was defined as the ratio of the measured concentration of a compound to its sensory detection threshold:

where

—concentration of the i-th compound [mg/m

3],

—its detection threshold. Threshold values were adopted from the literature [

35]: H

2S—0.0005 mg/m

3, NH

3—1.7 mg/m

3, VOC—0.1 mg/m

3, CH

3SH—0.0001 mg/m

3. For each sample, the following were calculated: total index

, dominant value

and identification of the dominant component

. Perceptual categories were defined according to the values

: <1—imperceptible, 1–10—weak, 10–100—moderate, >100—strong. Due to the non-additive nature of odour mixture perception (synergy/antagonism), the OAV was treated as an indicative value, and the conclusions were primarily based on the SOI and perceptual models.

4.9. Analysis of Olfactometer Compliance (Nasal Ranger vs. Scentroid)

The concordance between the Nasal Ranger and the Scentroid SM-100 was evaluated by performing 401 simultaneous measurements under identical field settings. The dataset was purged of zeros and negative values, and the D/T values underwent a log transformation (log10(x)) to stabilise variance and mitigate the influence of outliers. Spearman’s correlation (rank concordance) and Pearson’s correlation (linear concordance on a logarithmic scale) were used to assess the links between the device readings. The Bland–Altman approach (bias, limits of agreement) and Deming regression were applied for a comprehensive evaluation of agreement. Deming regression accounts for errors in both variables. Lin’s Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) was computed; this coefficient integrates data on the correlation’s strength and the degree of agreement between the measurements.

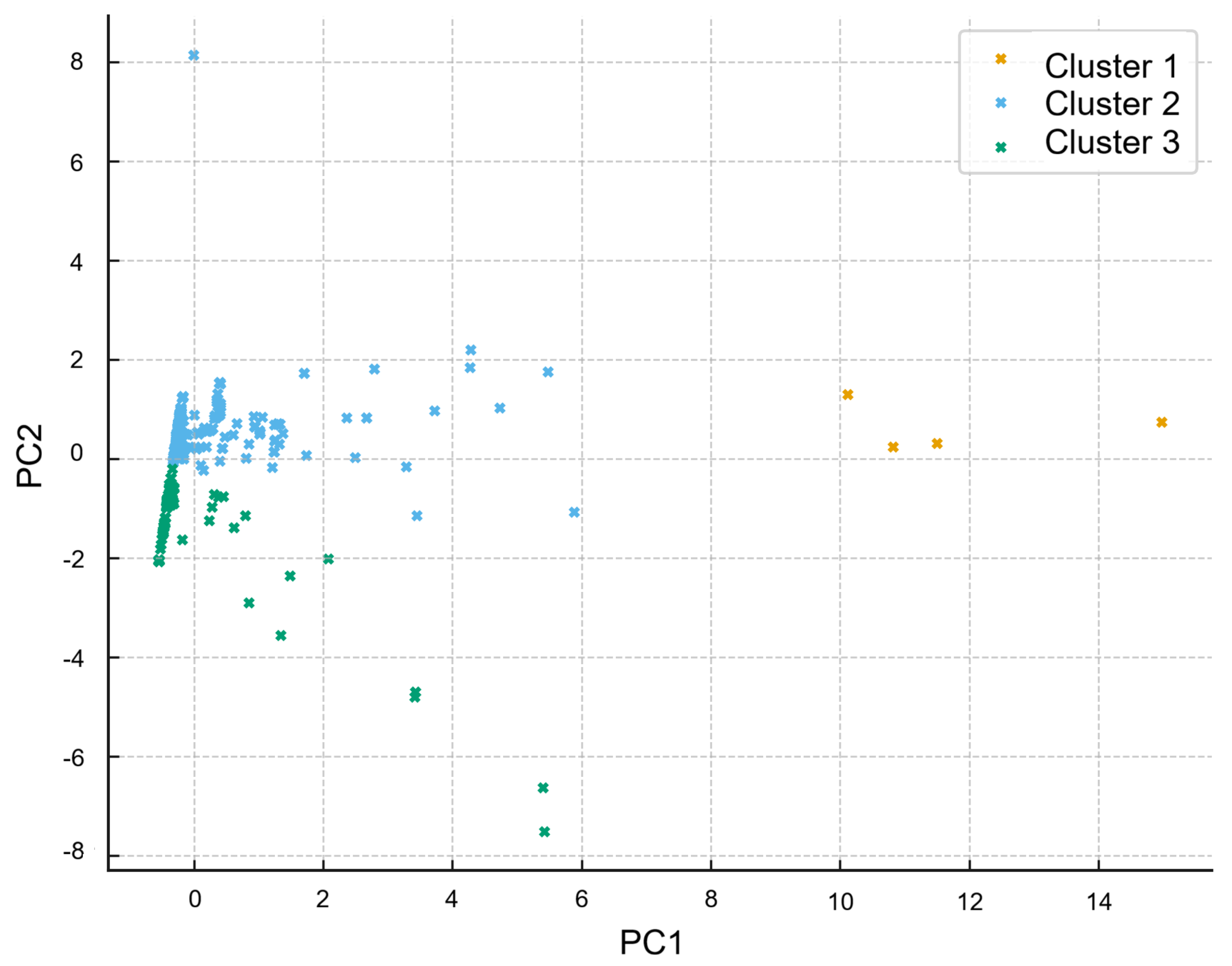

4.10. Cluster Analysis

Cluster analysis was used to discern groupings of data with similar chemical and environmental features. The input data included standard concentrations of H2S, NH3, VOCs, CH3SH, and meteorological factors, including air temperature and air humidity. PCA was first conducted for dimensionality reduction and collinearity removal; the top two components, which accounted for around 50% of the variation, were used for clustering. The selection of the first two principal components was based on a compromise between variance representation and interpretability. PC1 captured the dominant odour-related chemical gradient, while PC2 represented a complementary microclimatic dimension. Inclusion of additional components did not materially improve cluster separation metrics and would have reduced interpretability without adding meaningful structure. Hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted using Ward’s approach (Euclidean distance); the ideal cluster count was established with the elbow method and the silhouette index, with stability confirmed by k-means (multiple initialisations). The cluster profiling used the medians and quartiles of the chemical variables after log1p(x) transformation, the percentages of exceedances of odour thresholds (OAV > 1), and the distributions of perceptual intensity. The clusters were analysed in relation to IO, OAV, and sensory evaluations to determine the alignment of the chemical-meteorological categorisation with the felt nuisance rating.

All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.4.2) using packages like tidyverse, lmtest, sandwich, MASS, lme4/ordinal, VGAM, mgcv, FactoMineR/factoextra, and pROC.

5. Results

5.1. Characteristics of the Dataset and Variable Distributions

The Results section focuses on statistically supported outcomes, with methodological details restricted to the Methods section. Effect sizes and significance levels are reported consistently for all major analyses, using metrics appropriate to each statistical framework. Exploratory checks, including low-intensity observations (OI < 1), did not materially alter the direction or significance of the main relationships; therefore, these observations were excluded from final perception-based models to improve interpretability.

The analysed dataset includes observations from thirteen measurement series, conducted under various operational and meteorological conditions over two years. The analyses used a subset of n = 405 observations with an intensity ≥ 1. Summary statistics for chemical compound concentrations, meteorological variables, and sensory parameters are presented in

Table 2.

The strength of the odour, measured on a five-point scale, exhibited an asymmetric distribution with a median of 2.0, a mean of 2.8, and a standard deviation of 1.6. Positive skewness (0.22) and negative kurtosis (−1.56) suggest a prevalence of low to intermediate scores, accompanied by sporadic high numbers. The distributions of chemical concentrations exhibited significant right skewness, particularly for VOCs and NH3, with skewness coefficients above 10. Many readings fell within the low concentration range, while there were sporadic instances of high concentrations. The concentrations of H2S exhibited a more balanced, although still positively biased distribution. The distributions of chemical concentrations showed strong right skewness, particularly for VOCs and NH3 (skewness > 10), justifying the use of logarithmic transformation in subsequent analyses.

High skewness and kurtosis reflect the episodic nature of odour emissions, characterised by infrequent but intense peaks rather than stable background levels. Such distributions are typical for field-based environmental odour data and indicate that mean-based statistics alone are insufficient to describe odour dynamics.

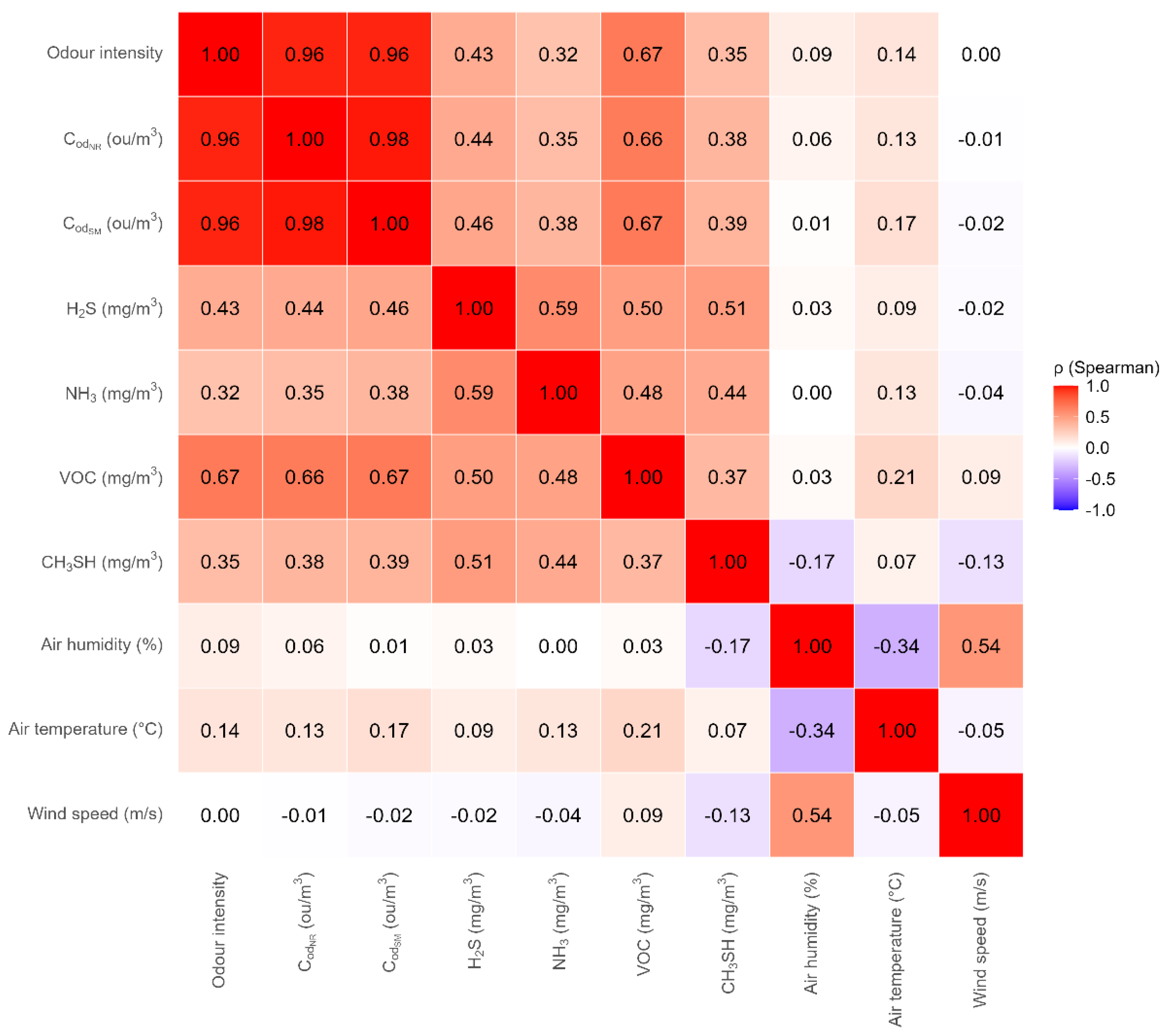

5.2. Correlations and Covariances of Parameters

Spearman’s correlation analysis demonstrated robust relationships between odour strength and quantities of sulphur compounds. The most robust link was seen for H

2S (ρ = 0.45;

p < 0.001), a moderate correlation for NH

3 (ρ ≈ 0.33;

p < 0.001), but VOCs and the aggregate of CH

3SH exhibited lesser correlations (ρ < 0.3). Moderate collinearity was detected among the chemical parameters (H

2S–NH

3, VOC–CH

3SH), warranting the use of regularisation techniques in further models. Wind speed exhibited a negative correlation with odour intensity (ρ = −0.30;

p < 0.001), but relative air humidity demonstrated a positive, although less robust, link. Odour intensity correlated most strongly with H

2S (ρ = 0.45,

p < 0.001), followed by NH

3 (ρ ≈ 0.33,

p < 0.001), while VOCs and CH

3SH showed weak associations (ρ < 0.3) (

Figure 1).

From a practical perspective, correlation magnitudes observed in this study indicate relationships of operational relevance rather than strict predictive dependence. Moderate correlations (ρ ≈ 0.3–0.5), such as those observed for H2S and NH3, imply that increases in these compounds are consistently associated with perceptible increases in odour intensity under field conditions, supporting their use as early warning indicators in operational monitoring. Weaker correlations (ρ < 0.3), observed for aggregated VOCs and CH3SH, suggest a more context-dependent contribution influenced by meteorological dispersion and mixture effects rather than direct linear control of perception.

5.3. Contextual and Spatial Differentiation

Spatial variability analysis indicated substantial discrepancies between data obtained inside and outside the wastewater pumping station structures. The mean odour intensity inside was much higher than outside (U = 11,500; p < 0.001), corroborating the presence of emission sources in technologically constrained zones with inadequate ventilation.

Seasonality without division: “indoor”/”outdoor” did not exhibit a distinct pattern in odour strength; nevertheless, chemical concentrations were elevated throughout the summer months, correlating with heightened emissions and accelerated diffusion of odorants. The Kruskal–Wallis test (H ≈ 28; p < 0.001; η2 ≈ 0.18) revealed seasonal variations in chemical parameters.

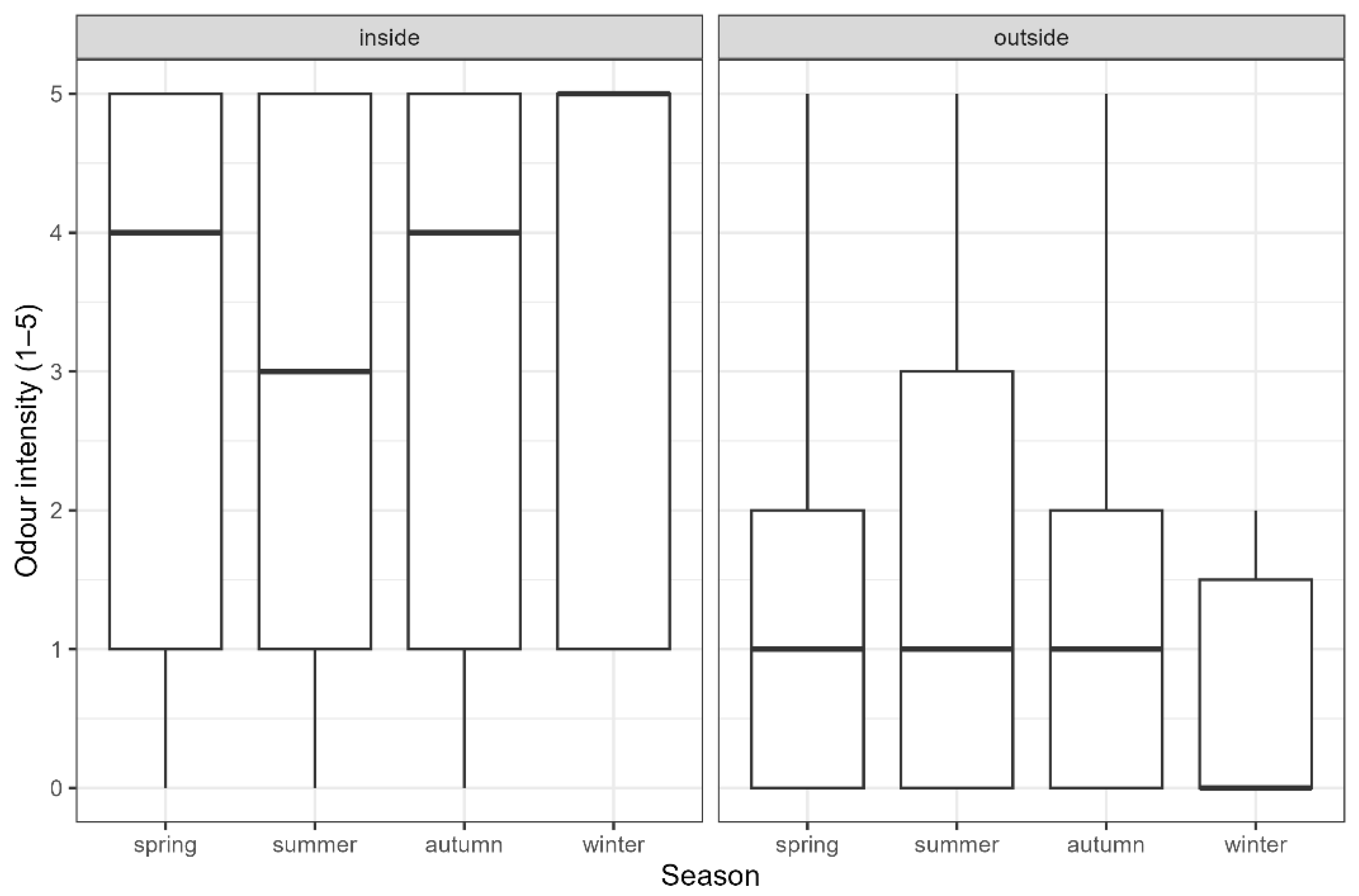

A seasonality analysis was also conducted with data stratified by measurement location (indoor/outdoor) (

Figure 2). When analysed separately, outdoor measurements exhibited significant seasonal variation (

p < 0.01), whereas indoor odour intensity remained statistically invariant across seasons (

p > 0.1). This demonstrates that the absence of clear seasonality in the pooled dataset results from a masking effect caused by consistently high indoor odour levels. After stratification, outdoor odour intensity showed moderate seasonality, with higher values in summer and lower values in winter, while indoor values remained persistently high throughout the year.

A moderate vertical concentration gradient was observed between the measurement levels (−1, ground level, and +1), suggesting the accumulation of odorants in the lower sections of the technological system. These results confirm the need to account for contextual variables (such as the location of receptor points and seasonality) in perceptual models.

5.4. Principal Component Analysis and Synthetic Odour Index (PCA, SOI)

PCA identified two principal components explaining approximately 60% of total variance (PC1: ~45%, PC2: ~15%). PC1 was dominated by H2S (loading = 0.95), NH3 (0.59) and CH3SH (0.57). The second principal component (PC2) represented a microclimatic gradient primarily related to relative air humidity (−0.81) and air temperature (−0.65).

Based on PC1, a Synthetic Odour Index (SOI) was developed and scaled to a range of 0–100. SOI correlated positively with odour intensity (r ≈ 0.33; p < 0.001), indicating a moderate but significant relationship between the integrated chemical dimension and odour perception. PC2, while explaining an additional proportion of variance, reflects environmental modulation of odour perception related to dispersion and microclimatic conditions rather than direct emission strength. Consequently, only PC1 was retained for SOI construction, as inclusion of PC2 would mix emission strength with dispersion-related effects and reduce the interpretability of the index as a practical indicator of odour nuisance.

5.5. Predictive Models of Odour Perception

5.5.1. Linear Models

Linear regression models were used as baseline reference models against which the performance and added value of ordinal and additive modelling approaches were evaluated. Improvements in fit and interpretability observed for non-linear and ordinal models motivated their further use. These improvements were reflected in lower AIC values and improved discrimination of odour intensity categories.

A linear regression model with odour intensity as the dependent variable (predictors: H2S, NH3, VOC, CH3SH, air temperature, air humidity, wind speed) showed significant relationships for most variables. The strongest effects were observed for H2S (β = 0.00081; p < 0.001) and wind speed (β = −0.72; p < 0.001). The model’s R2 was approximately 0.26, and after the log1p transformation, it increased to 0.30.

The model based on the SOI achieved an R2 ≈ 0.14, with a significant influence of SOI (p < 0.001) and a positive air humidity effect. These results confirm that the SOI can function as a chemical-sensory aggregate, describing the overall perception of the odour.

5.5.2. Ordered Models (CLMM)

In ordinal models (Cumulative Link Mixed Models) with a random effect for the measurement level, an AIC of 1052.8 was obtained. All major chemical predictors (H2S, NH3, VOCs, CH3SH) had positive effects, with H2S having the dominant influence. The measurement location (indoor/outdoor) was a significant factor (p < 0.001), confirming the importance of spatial context. The assumption of proportional odds was met. Increasing H2S concentration significantly increased the probability of higher odour intensity categories (OR ≈ 1.8 per log-unit increase, p < 0.001).

5.5.3. Additive Models (GAM/VGAM)

Additive models (GAM and VGAM) allowed us to capture the non-linear effects of odorant concentrations. The strongest curvilinear relationships were found for VOCs and air humidity, with a plateau effect at the highest values. After reducing the number of predictors, the VGAM model achieved a lower AIC (~944), indicating a better fit compared to the CLMM. Smooth terms for VOC concentration (edf ≈ 3.2, p < 0.01) and air humidity (edf ≈ 2.7, p < 0.01) were statistically significant.

5.5.4. Regularisation and Validation Models

The Ridge and LASSO models confirmed the hierarchy of variable influence: H2S > NH3 > VOC > air temperature > wind speed. Block validation (with the measurement level as a block) demonstrated predictive stability and the absence of data leakage, confirming the models’ robustness against overfitting. Across penalised models, H2S consistently retained non-zero coefficients and the highest relative importance, indicating robustness of this effect across model specifications.

Compared with linear baseline models, ordinal (CLMM) and additive (VGAM) models demonstrated improved goodness-of-fit and predictive performance, justifying their increased complexity.

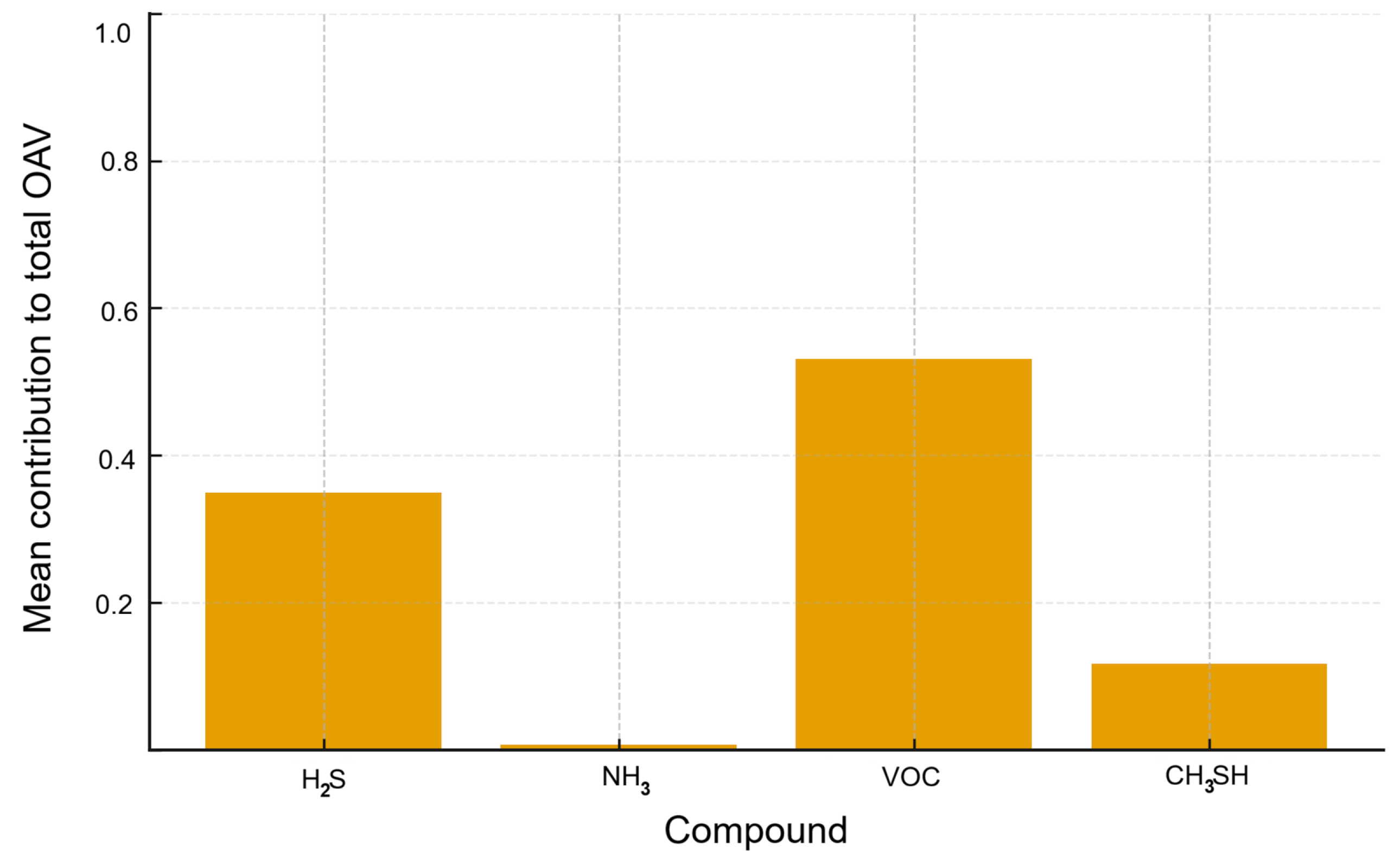

5.6. Odour Activity Value (OAV)

OAV indicators were calculated based on concentrations and odour thresholds: H

2S (0.0005 mg/m

3), NH

3 (1.7 mg/m

3), VOC (0.1 mg/m

3), CH

3SH (0.0001 mg/m

3) (

Figure 3). H

2S exceeded the odour threshold in almost all samples, CH

3SH in 15%, and NH

3 in approximately 9%.

The dominant contribution of H2S is due to its very low detection threshold (0.0005 mg/m3). The relationship between odour intensity and log10(OAV_dom) was significant (ρ = 0.46; p < 0.001; R2 ≈ 0.25), which confirms the usefulness of OAV as an approximate indicator of the odour potential of mixtures.

It is important to emphasise that the dominance of hydrogen sulfide in shaping the perceived odour intensity, as concluded by the OAV analysis, holds true despite the known extremely low Odour Detection Thresholds (OTs) of volatile organic sulfur compounds (VOSCs), such as methanethiol, which are often in the 10−7 mg/m3 range. While VOSCs possess a higher intrinsic olfactory potential, their concentrations in the sampled points were consistently very low. In contrast, hydrogen sulphide, with a higher OT (0.0005 mg/m3), was present at concentrations high enough for its OAVH2S to significantly outweigh the OAV of thiols in most measurements. Therefore, our conclusion regarding the predominant role of H2S is based on its actual contribution to the perceived odour under the observed operational conditions, rather than solely on the theoretically low detection limits of other compounds.

5.7. Olfactometry Measurement Consistency

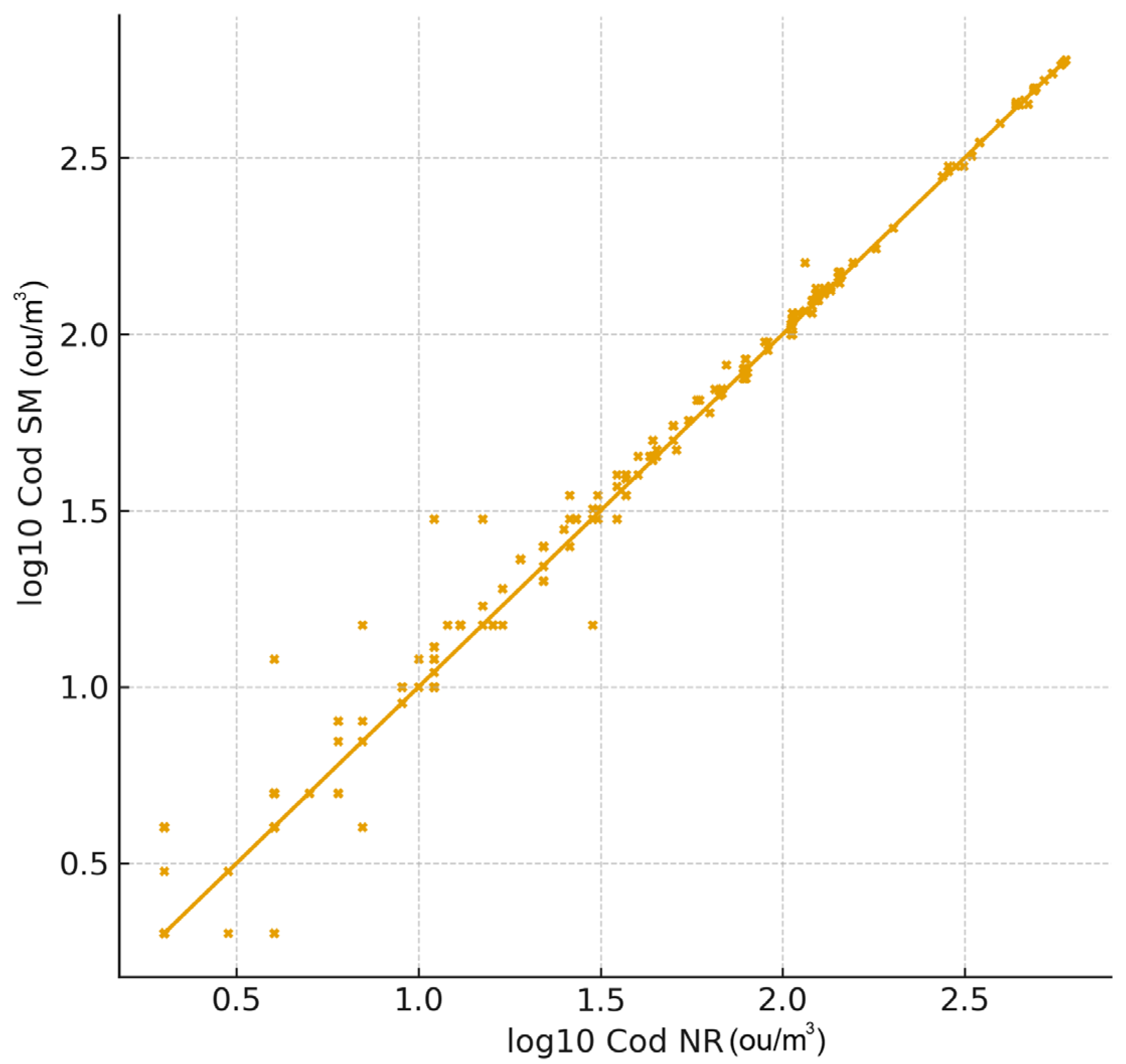

Analysis of 401 paired measurements showed high agreement between the Nasal Ranger and the Scentroid SM (

Figure 4).

Spearman’s correlation ρ = 0.99 (p < 2.2 × 10−16), Pearson (log10) r = 0.986, and Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient CCC = 0.9994 [0.9993–0.9995]. Deming regression confirmed the proportionality of the results (slope ≈ 1.96, intercept ≈ 1.00), and Bland–Altman analysis showed no significant systematic errors. The obtained CCC ≥ 0.90 and narrow limits of agreement in the Bland–Altman analysis confirm the practical interchangeability of the readings within the analysed D/T range.

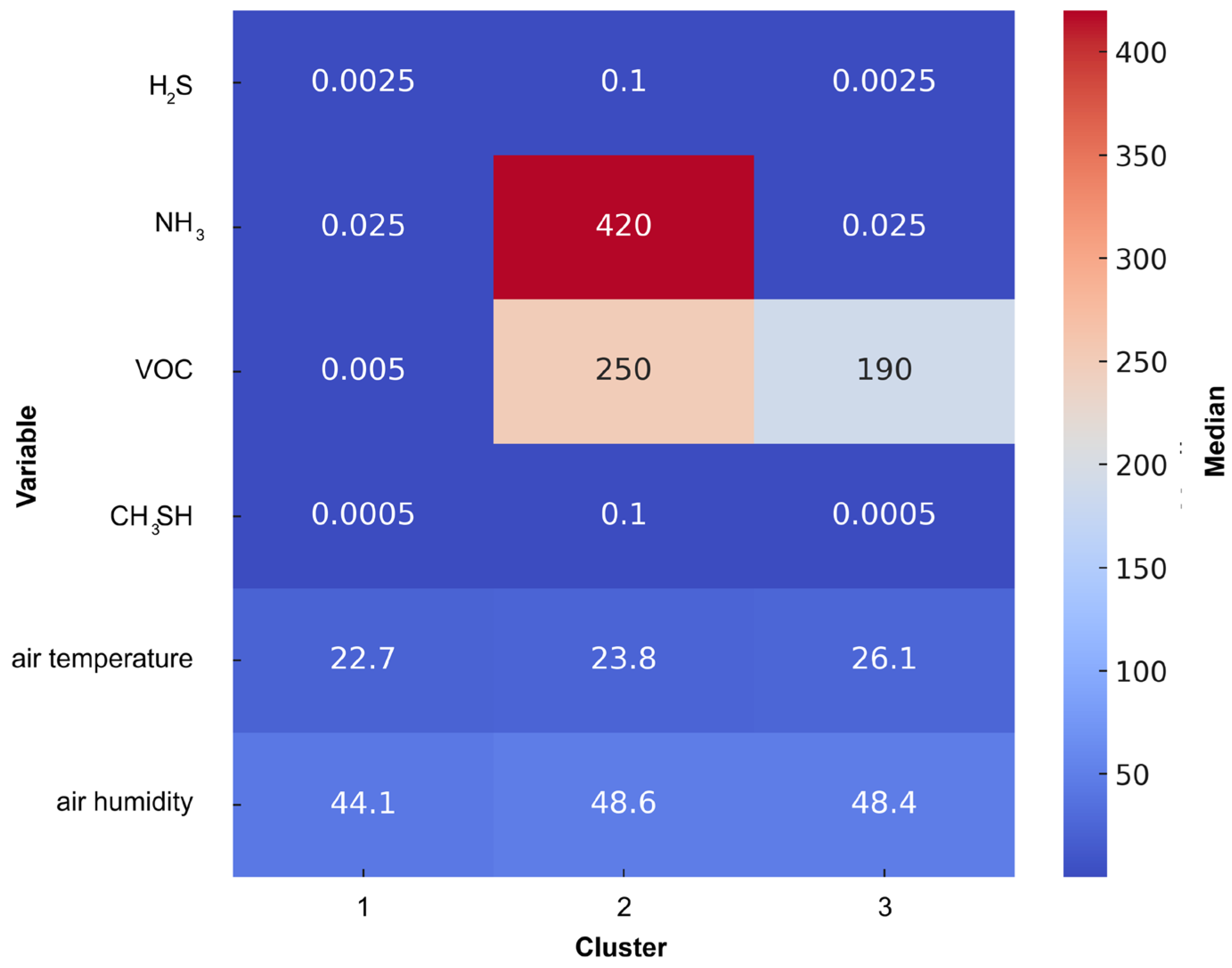

5.8. Cluster Analysis

Cluster analysis (PCA + Ward’s method, verified by k-means) revealed three characteristic sample groups reflecting differences in odour-relevant chemical and microclimatic conditions:

Cluster 1—samples with low odour intensity (approx. 90% of observations), characterised by very low concentrations of H2S, NH3, and CH3SH, and sporadic presence of VOCs.

Cluster 2—episodes of elevated emissions (approx. 9% of observations), with high H2S and NH3 values and frequent exceedances of odour thresholds (OAV > 1).

Cluster 3—a single episode dominated by VOCs, indicating a local emission source with a specific chemical composition.

The average silhouette coefficient of 0.69 confirms good cluster separation (

Figure 5), indicating the existence of clear differences between low and high odour intensity episodes.

Samples from cluster 2 were mostly located in outdoor settings throughout the summer, suggesting the impact of weather circumstances.

A heatmap was created to synthetically depict the distinctions across the clusters, illustrating the medians of chemical variables (H

2S, NH

3, VOC, CH

3SH) and meteorological data (air temperature, relative air humidity) among three observation groups (

Figure 6).

Distinct disparities are seen across the groups: cluster 1 is associated with low odour levels (below the annoyance threshold), cluster 2 with moderate emissions, and cluster 3 with strong occurrences. The standardised variant (z-score) facilitates the evaluation of relative disparities among variables with disparate units of measurement and indicates that the most significant differences between clusters pertain to sulphur compounds (H2S, CH3SH) and meteorological parameters, thereby affirming their pivotal impact on the odour profile of the mixture.

Cluster robustness was assessed by comparing results obtained using hierarchical clustering with Ward’s linkage and alternative partitioning approaches (k-means). Although different distance metrics and clustering algorithms can lead to minor variations in cluster boundaries, the overall structure of three dominant clusters representing low-, moderate-, and high-emission regimes was consistently preserved. The stability of the clustering solution was further supported by a high average silhouette coefficient (0.69) and by the coherent alignment of clusters with independent indicators such as SOI, OAV_dom, and odour intensity.

5.9. Relationship Between Clusters and SOI, OAV, and Intensity

Analysis of variance (Kruskal–Wallis test) revealed significant differences between the clusters (p < 0.001) in all three indicators: SOI, OAV_dom, and odour intensity. The average SOI values were as follows: cluster 1—approx. 13, cluster 2—approx. 60, cluster 3—>80. The OAV_dom index increased from a value < 5 for low odour levels (cluster 1) to >1000 during intense episodes (cluster 3).

A comprehensive analysis of the correlations between SOI—intensity (r = 0.33) and OAV—intensity (ρ ≈ 0.46) indicates a moderate concordance between both markers and olfactory perception. The SOI more efficiently consolidates multi-faceted information, while the OAV more prominently highlights the influence of chemicals with very low detection thresholds (thiols, H2S). The analyses validated the distinctions among the clusters, showing consistency between chemometric patterns and perceptual responses rather than direct equivalence.

5.10. Integrated Interpretation

The integration of PCA/OI methodologies, perceptual models (CLMM, VGAM), and OAV indicators elucidates two primary mechanisms governing odour perception: (1) a chemical component, regulated by H2S, NH3, VOC, and CH3SH emissions, and (2) a physical component, contingent upon meteorological conditions (air temperature, air humidity, turbulence).

The integration of SOI and OAV indicators establishes a quantifiable connection between chemical test outcomes and human perception. The established associations serve as a foundation for further odour risk modelling and the formulation of air quality indicators that include the olfactory dimension. It should be noted that the Synthetic Odour Index functions as an integrative descriptor of odour-related conditions rather than as a direct or universal measure of perceived odour intensity.

6. Discussion of Results

6.1. The Complex Nature of Odour Nuisance

The research results indicate that the odour nuisance at the examined facility is multifaceted and dynamic, influenced by the interaction of chemical, meteorological, and contextual elements. The outcome is contingent upon the interplay of chemical elements (composition and concentration of odorants), climatic factors (wind, air temperature, air humidity), and contextual factors (local working conditions, variations in wastewater flow, and ventilation). Although most observations showed low odorant concentrations, the data revealed brief but intense emission events that strongly influenced odour perception. This spatiotemporal variability aligns with findings from other wastewater treatment facilities and indicates localised variations in wastewater flow and ventilation conditions. These incidents significantly affect odour perception and elicit complaints from homeowners. The spatiotemporal variability of emissions aligns with findings from other sewage systems and wastewater treatment facilities, where fluctuations in emissions result from local alterations in wastewater flow, ventilation conditions, and atmospheric influences [

2,

8,

36,

37,

38,

39].

These relationships reflect well-established physical and biochemical mechanisms: elevated temperature enhances volatilisation and microbial activity, increased humidity reduces dilution and prolongs odour persistence, whereas higher wind speeds promote dispersion and reduce local concentration peaks. Separating the data into measurements taken inside and outside the facility revealed that seasonality in odour intensity occurs exclusively in open spaces. The interior sections of the facility exhibited consistently high values throughout the year, whereas the highest outdoor values were recorded in summer, which aligns with the air temperature-driven intensification of biological emissions. This finding explains the absence of clear seasonality in the aggregated analysis and highlights the dominant influence of microenvironmental conditions.

The variation in chemical profiles—from low odour levels dominated by H

2S to conditions with a substantial contribution of NH

3 and VOCs—reflects the presence of distinct emission pathways: some emissions originate from biological processes (e.g., decomposition of sulphur compounds in raw sewage), while others arise from chemical and technological reactions in enclosed systems. The results indicate that a thorough evaluation of odour nuisance necessitates the concurrent analysis of emission characteristics (concentrations and chemical composition of odorants), environmental variables (meteorological conditions, ventilation), and perceptual elements (odour intensity and quality assessed sensorially) [

10,

34,

40,

41,

42,

43]. The temporal and geographical variability of emissions, together with the complexity of odorant mixes, indicates that a mere summation of concentration fails to accurately represent the real experience of odour [

10,

39,

44]. The observed seasonal masking effect can be explained by the operational conditions of the pumping station. During summer, increased ventilation through open doors and gates enhances air exchange, whereas in winter, the facility remains more sealed. As a result, seasonal variability primarily affects open outdoor spaces, while enclosed technological interiors exhibit persistently high odour levels independent of season.

6.2. Relationships Between Chemical Parameters and Odour Perception

Correlation analysis established a strong, albeit modest, association between odour intensity and the quantities of primary odoriferous chemicals (H

2S, NH

3, VOCs, CH

3SH). The most robust relationships were seen for H

2S and NH

3, aligning with their low detection thresholds and common occurrence in wastewater settings. VOCs functioned as modifying variables; their impact was apparent when paired with other odorants, although they did not independently dictate perception. These findings align with other research suggesting that odour perception is a non-linear function of odorant mixtures, rather than a mere aggregation of their concentrations. Odour perception is a non-linear function of odorant mixtures, characterised by occurrences of synergy and antagonism, as well as modification by environmental conditions like air temperature, air humidity, and air turbulence. Research indicates that odorant combinations may provoke olfactory sensations that are either more intense or less intense than the aggregate of their individual components, as substantiated by sensory analysis and neurophysiological modelling [

45,

46,

47].

6.3. Regression, Ordinal and Nonlinear Models of Odour Perception

Although multiple statistical approaches were applied, the analyses were guided by a limited set of predefined research questions focusing on the relationships between odour perception, key chemical indicators and meteorological conditions. The different modelling techniques were used in a complementary manner to examine the same core hypotheses from linear, ordinal and non-linear perspectives rather than to perform exploratory testing or post hoc hypothesis generation. Extreme data distributions motivated the use of logarithmic transformations, robust estimation, and non-linear models, which improved stability and reduced sensitivity to outliers while preserving high-impact odour episodes.

Linear regression models indicate that air temperature and relative air humidity significantly influence odour perception, whereas wind speed constrains perceived intensity through enhanced dispersion. These findings align with existing research, which suggests that the local microclimate may influence odour intensity to a degree similar to that of source emissions. Elevated air temperatures result in enhanced emissions of odorants, including sulphur compounds and ammonia, attributable to increased microbiological activity and elevated vapour pressure of volatile substances [

48]. Relative air humidity positively corresponds with odour emission and perception, especially for NH

3 and H

2S [

49]. Conversely, windspeed constrains odour perception at the source by spreading and diluting odorant concentrations in the atmosphere, as shown by both modelling and empirical studies. Elevated wind speeds facilitate dispersion, reducing local concentrations and olfactory disturbances; however, they may expand the impacted region [

7,

50]. While previous studies on wastewater treatment plants report similar drivers of odour perception, the present results extend these findings by demonstrating that, in pumping stations, short-term operational conditions and enclosure effects can outweigh seasonal variability observed at larger treatment facilities.

Chemical factors, particularly H

2S and NH

3, exhibited considerable importance in log-linear models (

p < 0.001). The use of logarithmic transformation and robust estimation (HC3) enhanced the stability of the estimations, which is advisable in environmental research [

51]. The resultant coefficient of determination, R

2 = 0.25, is regarded as a standard value for field investigations when odour perception is also influenced by individual and contextual variables.

Together, ordinal and nonlinear models provide complementary insight into the structure of odour perception, capturing both discrete intensity categories and curvilinear sensory responses. Ordinal models (CLMM) facilitate the characterisation of odour perception on a categorical scale while accounting for differences across measurement levels. The use of random effects mitigated spatial variance and decreased information leakage among samples.

VGAM investigations indicated non-linear correlations between odorant concentrations and perception, particularly for VOCs and air humidity, where threshold values and a plateau effect were seen at elevated concentrations. This confirms that perceptual relationships in olfactory settings follow a curvilinear and saturating pattern, in line with Weber-Fechner’s rule and previous findings. The smooth terms obtained from GAM and VGAM models were interpreted as flexible representations of non-linear relationships rather than mechanistic functions. In particular, the observed threshold and plateau effects for VOC concentration and air humidity indicate saturation consistent with established psychophysical principles of olfactory perception. These smoothers provide insight into response patterns while maintaining interpretability at the level required for environmental decision-making.

6.4. Synthetic Odour Index (SOI) as a Perceptual Model

The Synthetic Odour Index (SOI), derived using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), effectively consolidates chemical and microclimatic data into a single numerical dimension. The moderate yet significant correlation with odour intensity (r ≈ 0.33;

p < 0.001) substantiates that SOI represents a principal dimension of odour variability, although it does not entirely encapsulate the subjective perception of odour, aligning with findings related to other “synthetic” indicators [

52,

53]. In contrast to the traditional OAV indication, the SOI more accurately represents the impact of covariation among the mixture components and mitigates the predominance of a singular component (e.g., H

2S) in the comprehensive evaluation. This enables SOI to function as a synthetic metric of olfactory perception, amalgamating instrumental and sensory data into a unified analytical dimension.

6.5. Odour Activity Value (OAV)—Usefulness and Limitations

OAV continues to serve as a predominant comparison metric, facilitating the identification of primary odour producers in combinations. Interpreting OAVs necessitates care, since a significant proportion of samples with OAV > 1 often arises from very low detection thresholds for some chemicals, like H

2S [

54,

55,

56]. The study of the dominant OAV indicator (OAV_dom) demonstrated a more pronounced correlation with perception (ρ = 0.46;

p < 0.001). Odour detection thresholds were adopted from established literature sources to ensure comparability with previous studies. While local population-specific thresholds may vary, the literature-based values are commonly used in environmental odour assessments and provide a consistent reference framework for relative comparisons rather than absolute prediction of perception.

A formal sensitivity analysis using alternative odour detection thresholds was not performed, as OAV was applied primarily as a relative indicator for ranking dominant odorants rather than for absolute prediction of odour perception. Changes in threshold values would proportionally affect absolute OAV magnitudes but would not alter the relative dominance of key compounds, particularly H2S and sulphur-containing species with very low detection thresholds. Consequently, the main conclusions regarding dominant contributors and high-risk odour episodes are robust to reasonable variations in the literature-based threshold values.

VOCs were treated as an aggregated group due to the limitations of field instrumentation and the exploratory nature of the analysis. This simplification is consistent with common practice in field-based odour studies and allows identification of dominant emission patterns, while acknowledging that detailed speciation would be required for compound-level mixture modelling. The SOI framework partially addresses this limitation by integrating VOC measurements with other chemical and microclimatic variables rather than relying on individual compound attribution.

The logarithmic correlation between odour intensity and OAV_dom (about 0.42 intensity units per order of magnitude rise in OAV) substantiates that odour perception is a logarithmic and nonlinear phenomenon, in accordance with Weber’s Law [

57].

6.6. Cluster Analysis and Odour Source Profiling

Cluster analysis validated the distinction of episodes exhibiting low, moderate, and high odour potential, aligning with the chemical-perceptual categorisation. In environmental field datasets characterised by high natural variability and episodic extremes, cluster interpretability is evaluated primarily through internal coherence (silhouette index, within-cluster consistency) rather than the proportion of total variance explained. The purpose of cluster analysis was exploratory and descriptive, aiming to identify recurrent emission patterns rather than to maximise explained variance. In highly variable environmental datasets, modest variance explained by the first principal components is common and does not preclude meaningful separation of dominant regimes. Cluster stability across seasons was not explicitly tested, as clusters were not intended to represent seasonal categories. Seasonal effects were therefore analysed independently using stratified comparisons, and cluster membership was interpreted in relation to prevailing meteorological conditions rather than as a fixed temporal structure. Instead, seasonal patterns were examined separately, and cluster membership was interpreted in relation to prevailing meteorological conditions rather than fixed temporal grouping. The observed predominance of high-emission clusters during summer supports this contextual interpretation.

The uniformity of the SOI, OAV_dom, and perceptual intensity values inside the clusters substantiates that this categorisation precisely represents the genuine emission and dispersion processes. The findings demonstrate that the integration of cluster analysis with synthetic indicators (SOI and OAV) serves as an effective method for identifying odour sources and episodes with the highest odour potential, which is beneficial for both diagnostic assessments and odour control practices.

6.7. Integration of Methods and Practical Significance

Current methodologies, including the use of an interaction coefficient (γ) and the use of vector models, permit a more comprehensive assessment of the interaction effects among mixture components and enhance the association between chemical indicators and sensory evaluation. Models using PCA and multiple regression are increasingly used, integrating chemical, meteorological, and sensory data to enhance the precision of odour perception predictions [

52,

53]. PC2 highlights the role of meteorological conditions as modulators of odour perception, whereas PC1 captures the dominant emission–perception axis used for SOI construction.

Although high correlation coefficients were observed between the Nasal Ranger® and Scentroid SM-100, correlation alone does not imply full analytical equivalence. Therefore, agreement-based methods (Bland–Altman analysis, Deming regression and Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient) were applied to assess practical agreement and operational interchangeability under field conditions. Paired measurements were performed simultaneously at identical receptor locations, which minimised the influence of short-term environmental variability (wind speed, air temperature and relative humidity). While strict laboratory control was not possible under field conditions, the adopted protocol reflects realistic operational use of portable olfactometers.

The high agreement observed between portable olfactometers should be interpreted considering the effective data range covered during the field campaign. Most paired measurements were conducted under low to moderate odour intensity conditions, where both devices operate within their optimal measurement ranges. At higher dilution-to-threshold values, potential ceiling effects may occur, particularly for instruments with a limited upper range. Therefore, the demonstrated interchangeability primarily applies within the observed concentration range, while caution is advised when extrapolating agreement to extreme odour episodes beyond the sampled conditions.

Minor discrepancies observed at higher dilution-to-threshold values are primarily related to differences in the operational ranges and sensitivities of the instruments and are operationally relevant, as they may affect the classification of extreme odour episodes. In practice, this indicates that portable field olfactometers should be selected according to expected odour intensity levels, with higher-range devices preferred during peak emission events. Despite these differences, both instruments consistently distinguished between low- and high-nuisance conditions, supporting their complementary use in field-based odour assessments.

The combined methodology of regression, ordinal, and additive models with PCA, OAV analysis, and clustering enabled an extensive mapping of odour processes at a localised level. Each approach provided a distinct perspective:

Linear models—quantitative assessment of the impact of chemical and meteorological factors,

CLMM—a probabilistic description of odour perception on an ordinal scale,

VGAM—capturing nonlinear effects,

OI—data integration in a synthetic dimension,

OAV and cluster analysis—profiling episodes with the highest odour potential.

The use of SOI and OAV indicators in operational procedures allows the dynamic regulation of deodorisation intensity and the forecasting of odour occurrences. The alignment of data from various methodologies validates that the integrated statistical-perceptual strategy is the best suited for odour research in real-world settings. These solutions may be used to assess the efficacy of deodorisation systems and in urban-scale odour nuisance prediction models.

The relationship between OAV and SOI was examined conceptually rather than through formal statistical testing, as the two indices are not intended to represent the same construct. OAV highlights the relative importance of individual odorants based on detection thresholds, whereas SOI integrates multi-dimensional chemical and contextual information. Their joint interpretation is therefore complementary rather than inferential. Both indices showed consistent alignment with odour intensity patterns, supporting their concurrent use without implying direct equivalence.

The Synthetic Odour Index (SOI) and odour activity value (OAV) introduced in the study may function as effective decision support instruments in the management of deodorisation systems. SOI, as a comprehensive metric, facilitates the ongoing assessment of an object’s odour potential without necessitating complete sensory evaluations. When integrated with OAV, it enables the identification of times and areas with the greatest odour emission risk, facilitating the optimisation of biofilter and ventilation system operations. The use of both indicators in intelligent monitoring, such as SCADA systems, enables the automated regulation of air purification intensity according to fluctuating environmental circumstances, resulting in diminished operating expenses and enhanced efficacy in alleviating odour disturbances.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Scientific Contributions

The results confirm that odour nuisance associated with wastewater pumping stations is a complex and dynamic phenomenon resulting from the interaction between emission processes, environmental conditions, and local operational factors. Short-term, high-intensity events play a disproportionate role in shaping odour perception, highlighting the limitations of assessments based solely on average concentrations.

Seasonality in odour perception was observed exclusively in open outdoor spaces, whereas odour intensity inside the facility remained consistently high throughout the year. This finding underscores the dominant role of local microclimatic and operational conditions and explains the masking of seasonal effects in aggregated datasets.

Complementary analytical approaches demonstrated that no single modelling framework is sufficient to characterise odour nuisance. Linear, ordinal and additive models, combined with chemometric techniques, revealed both continuous and categorical aspects of odour perception as well as non-linear sensory responses.

The Synthetic Odour Index (SOI), derived using Principal Component Analysis, proved effective in integrating chemical and microclimatic information into a single numerical dimension representing overall odour potential. Its moderate but statistically significant association with odour intensity confirms its diagnostic value. At the same time, the Odour Activity Value (OAV) remains useful for identifying dominant odorants, particularly sulphur compounds, despite inherent assumptions regarding additivity.

Cluster analysis further supported the existence of discrete emission regimes consistent with SOI, OAV and sensory observations, confirming the coherence between chemometric patterns and perceptual responses.

7.2. Practical Implications and Applicability

From a practical perspective, the proposed SOI-based framework can support operational decision-making in urban wastewater pumping stations by enabling early identification of odour nuisance conditions. The approach is suitable for implementation within continuous or semi-continuous monitoring systems, supporting ventilation control, deodorisation unit optimisation and targeted maintenance activities.

In operational practice, SOI may be used as an indicator for defining alert levels associated with increased odour risk. Exceedance of site-specific SOI thresholds can trigger preventive actions such as intensified ventilation, temporary modification of pumping regimes, or enhanced operation of deodorisation units during periods of unfavourable meteorological conditions.

Integration of SOI with meteorological forecasts further enables short-term prediction of odour nuisance episodes, which is particularly relevant in densely populated urban areas. The proposed framework is transferable to other urban wastewater facilities and provides a scientifically grounded basis for data-driven odour management. Future research should focus on extending the methodology to continuous monitoring systems and validating its applicability across different types of wastewater infrastructure.