Application of Microfluidics in Plant Physiology and Development Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Plant Cells, Tissues, and Organs in Microenvironments

2.1. Plant Research Fields with Advantageous Application of Microfluidic Devices

2.2. Microchambers and Microchannels in Plant Cultivation

- Cultivation volume: Optimal chamber or channel volume must balance sufficient nutrient delivery with the need to maintain biologically relevant interactions such as quorum sensing or paracrine signaling [124].

- (a)

- A dual-layer design separates a thin cell-cultivation chamber from an underlying transfer channel via a porous membrane, enabling continuous metabolite exchange [31].

- (b)

- A pentagonal array of interconnected chambers (~160 nL each) permits parallel cultivation of plant protoplast populations, with integrated microcolumn structures (20 μm gaps) that prevent cellular escape [29].

- (c)

- Large-scale arrays composed of square wells facilitate seedling cultivation and phenotyping; these systems support simultaneous exposure to multiple media compositions and allow for high-throughput screening [72].

- (d)

- Whole-plant or organ-level cultivation is enabled by macro-scale chambers (cultivation areas > 85 cm2), such as the Root-TRAPR system, which accommodates expansive root architectures while maintaining optical access for imaging and analysis [78].

3. Microfluidically Assisted Plant Technology

3.1. Microfluidic Devices for Cell-Based Investigation

3.2. Microfluidic Devices for Plant Development and Structural Characterization Research

3.3. Devices for Investigating Plant Cell Stress Response and Communication

4. Future Perspectives: Harnessing Microfluidics for Sustainable and Scalable Plant Technologies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDMS | polydimethylsiloxane |

| HILO | highly inclined and laminated optical sheet |

| MAC | microfluidic antibody capture |

| CMT | Cortical microtubule |

| ITO | Indium Tin Oxide |

| DLD | Deterministic lateral displacement |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| PP9 | perfluoromethyldecalin |

| MEMS | Microelectromechanical Systems |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| ED | Electrochemical detection |

| DC-iDEP | Direct-current insulator-based dielectrophoresis |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| PCW | Primary cell wall |

| IFC | impedance flow cytometry |

| BLOC | Bending-Lab-On-Chip |

| FiLoC | Flexure integrated Lab-on-a-Chip |

| FRET | Förster Resonance Energy Transfer |

| LMJ-SSP-MS | liquid micro-junction surface sampling probe mass spectrometry |

| CZE-MS | capillary zone electrophoresis-mass spectrometry |

| DSLR | Digital Single-Lens Reflex |

| LED | Light-Emitting Diode |

| NaCl | Sodium chloride |

| Pi | Inorganic phosphate |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| Kyn | Kynurenine |

| SGC | Seed Growth Chips |

| ENM | Electrospun nanofibrous membrane |

| FRAP | Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching |

| TRIS | Tracking root interaction system |

| mPFMC | Miniaturized plant-microbial fuel cell |

| SBN | Sugar beet nematode |

| GFP | Green Fluorescence Protein |

References

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wang, D.; Olesen, J.E. Challenges in upscaling laboratory studies to ecosystems in soil microbiology research. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, M.; Johansson Jänkänpää, H.; Moen, J.; Janssin, S. An illustrated gardener’s guide to transgenic Arabidopsis field experiments. New Phytol. 2008, 180, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L.; Cooledge, E.C.; Chadwick, D.R. Is one year enough? A commentary on field experiment duration in agricultural research. Agric. Syst. 2025, 228, 104393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruppuarachchi, C.; Kulsoom, F.; Ibrahim, H.; Khan, H.; Zahid, A.; Sher, M. Advancements in plant wearable sensors. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 229, 109778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyola-Vargas, V.M.; De-la-Peña, C.; Galaz-Avalos, R.M.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R. Plant tissue culture. In Molecular Biomethods Handbook: Second Edition; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 875–904. [Google Scholar]

- Husen, S.; Husen, S.; Purnomo, A.E.; Tina, S.A.; Iriany, A.; Wahyono, P.; Roeswitawati, D. Liquid culture for efficient in vitro propagation of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) using bioreactor system. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2024, 18, 365–373. [Google Scholar]

- Podar, D. Plant growth and cultivation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 953, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Junker, A.; Junker, A.; Muraya, M.M.; Weigelt-Fischer, K.; Arana-Ceballos, F.; Klukas, C.; Melchinger, A.E.; Meyer, R.C.; Riewe, D.; Altmann, T. Optimizing experimental procedures for quantitative evaluation of crop plant performance in high throughput phenotyping systems. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.; Brütting, C.; Meza-Canales, I.D.; Großkinsky, D.K.; Vankova, R.; Baldwin, I.T.; Meldau, S. The role of cis-zeatin-type cytokinins in plant growth regulation and mediating responses to environmental interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 4873–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngomuo, M.; Mneney, E.; Ndakidemi, P. The Effects of Auxins and Cytokinin on Growth and Development of (Musa sp.) Var. “Yangambi” Explants in Tissue Culture. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R.; Govindarajan, I. Micropropagation for multiplication of elite genotypes. In Tissue Culture Techniques in Vegetable Crop Improvement; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 127–158. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Hu, B.; Zeng, B. Establishment of a Highly Efficient Micropropagation System of Aquilaria crassna Pierre ex Lecomte. Forests 2024, 15, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimavat, N.; Parikh, P. Innovations in Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) micropropagation: Detailed review of in vitro culture methods and plant growth regulator applications. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 2024, 159, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, P.M. Therapeutically important proteins from in vitro plant tissue culture systems. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, S.; Sharma, K. Microenvironmentation in Micropropagation. In Modern Applications of Plant Biotechnology in Pharmaceutical Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 345–360. [Google Scholar]

- Hedden, P.; Stephen, G. Thomas, Gibberellin biosynthesis and its regulation. Biochem. J. 2012, 444, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, A.F.; Ali, M.M.; Rizwan, H.M.; Gad, A.G.; Liang, D.; Binqi, L.; Kalaji, H.M.; Wróbel, J.; Xu, Y.; Chen, F. Light quality and quantity affect graft union formation of tomato plants. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaeim, H.; Kende, Z.; Balla, I.; Gyuricza, C.; Eser, A.; Tarnawa, Á. The Effect of Temperature and Water Stresses on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Sustainability 2022, 14, 3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, K.; Geng, S.; Hossain, M.; Ye, X.; Li, A.; Mao, L.; Kogel, K.H. Enemies at peace: Recent progress in Agrobacterium-mediated cereal transformation. Crop. J. 2024, 12, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Massel, K.; Tabet, B.; Godwin, I.D. Biolistic DNA Delivery and Its Applications in Sorghum bicolor. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2014, 197–215. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann, F.; Dussert, S. Cryopreservation. In Conservation of Tropical Plant Species; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Białoskórska, M.; Rucińska, A.; Boczkowska, M. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Freezing Tolerance in Plants: Implications for Cryopreservation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchenkova, M.A.; Chapek, S.V.; Mukhanova, E.A.; Soldatov, A.V.; Kovalchuk, M.V. Microfluidic Processes As an Element of Bioinspired Technologies. Nanobiotechnology Rep. 2024, 19, 266–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araz, M.K.; Tentori, A.M.; Herr, A.E. Microfluidic Multiplexing in Bioanalyses. SLAS Technol. 2013, 18, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, D.; van Blitterswijk, C.; Habibovic, P. High-throughput screening approaches and combinatorial development of biomaterials using microfluidics. Acta Biomater. 2016, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, C.I.; Cheah, E.; Delon, L.; Nilghaz, A.; Thierry, B. Pumpless Microfluidic Devices and Uses Thereof. U.S. Patent Application 17/774,078, 24 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sanati Nezhad, A. Microfluidic platforms for plant cells studies. Lab A Chip 2014, 14, 3262–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.I.; Ko, J.M.; Kim, S.H.; Baek, J.Y.; Cha, H.C.; Lee, S.H. Soft material-based microculture system having air permeable cover sheet for the protoplast culture of Nicotiana tabacum. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2006, 29, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Liu, W.; Tu, Q.; Song, N.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. Culture and chemical-induced fusion of tobacco mesophyll protoplasts in a microfluidic device. Microfluid. Nanofluidics 2011, 10, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozgunova, E.; Goshima, G. A versatile microfluidic device for highly inclined thin illumination microscopy in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maisch, J.; Kreppenhofer, K.; Büchler, S.; Merle, C.; Sobich, S.; Görling, B.; Luy, B.; Ahrens, R.; Guber, A.E.; Nick, P. Time-resolved NMR metabolomics of plant cells based on a microfluidic chip. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 200, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mickleburgh, T.G.; Salehi-Reyhani, A.; Magness, A.J.; Joyce, W.D.; Ces, O.; Klug, D.R. A miniaturized microfluidic assay for single plant cell protein quantification. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Miniaturized Systems for Chemistry and Life Sciences, Savannah, GA, USA, 22–26 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, K.; Charlot, F.; Le Saux, T.; Bonhomme, S.; Nogué, F.; Palauqui, J.C.; Fattaccioli, J. Design of a comprehensive microfluidic and microscopic toolbox for the ultra-wide spatio-temporal study of plant protoplasts development and physiology. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, T.; Artmann, P.J.; Gkekas, I.; Illies, F.; Baack, A.L.; Viefhues, M. Microfluidic Single-Cell Study on Arabidopsis thaliana Protoplast Fusion-New Insights on Timescales and Reversibilities. Plants 2024, 13, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaban, B.; Liu, W.; Jiang, X.; Nick, P. Plant cells use auxin efflux to explore geometry. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.S.; Zhao, Y.M.; Okeyo, K.O.; Kurosawa, O. One-to-one Fusion of Plant Protoplasts by Using Electrofusion Based on Electric Field Constriction. BioNanoScience 2024, 14, 4520–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kurihara, D.; Higashiyama, T.; Arata, H. Fabrication of microcage arrays to fix plant ovules for long-term live imaging and observation. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 191, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, M.; Nezhad, A.S.; Agudelo, C.G.; Packirisamy, M.; Geitmann, A. Microfluidic positioning of pollen grains in lab-on-a-chip for single cell analysis. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2014, 117, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand-Smet, P.; Spelman, T.A.; Meyerowitz, E.M.; Jönsson, H. Cytoskeletal organization in isolated plant cells under geometry control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 17399–17408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin, L.; Chevallier, A.; Tsugawa, S.; Gacon, F.; Godin, C.; Viasnoff, V.; Saunders, T.E.; Hamant, O. Cortical tension overrides geometrical cues to orient microtubules in confined protoplasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 32731–32738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, M.S.; Chang, H.J. Developing microfluidics for rapid protoplasts collection and lysis from plant leaf. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part N J. Nanoeng. Nanosyst. 2012, 226, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Pineda, O.G.; Guevara-Pantoja, P.E.; Marín-Lizarraga, V.; Caballero-Robledo, G.A.; Patiño-Lopez, L.D.; May-Arrioja, D.A.; De-la-Peña, C.; Garcia-Cordero, J.L. Parallel DLD microfluidics for chloroplast isolation and sorting. Lab A Chip 2025, 25, 4609–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parimalam, S.S.; Abdelmoez, M.N.; Tsuchida, A.; Sotta, N.; Tanaka, M.; Kuromori, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Hirai, M.Y.; Yokokawa, R.; Oguchi, Y.; et al. Targeted permeabilization of the cell wall and extraction of charged molecules from single cells in intact plant clusters using a focused electric field. Analyst 2021, 146, 1604–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horade, M.; Yanagisawa, N.; Mizuta, Y.; Higashiyama, T.; Arata, H. Growth assay of individual pollen tubes arrayed by microchannel device. Microelectron. Eng. 2014, 118, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, C.G.; Sanati Nezhad, A.; Ghanbari, M.; Naghavi, M.; Packirisamy, M.; Geitmann, A. TipChip: A modular, MEMS-based platform for experimentation and phenotyping of tip-growing cells. Plant J. 2013, 73, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanati Nezhad, A.; Packirisamy, M.; Geitmann, A. Dynamic, high precision targeting of growth modulating agents is able to trigger pollen tube growth reorientation. Plant J. 2014, 80, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, N.; Sugimoto, N.; Higashiyama, T.; Sato, Y. Development of Microfluidic Devices to Study the Elongation Capability of Tip-growing Plant Cells in Extremely Small Spaces. Jove-J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 8, 57262. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Lin, W.; Van Norman, J.M.; Qin, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Z. Membrane receptor-mediated mechano-transduction maintains cell integrity during pollen tube growth within the pistil. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 1030–1042.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.M.; Ju, J.; Lee, S.; Cha, H.C. Tobacco protoplast culture in a polydimethylsiloxane-based microfluidic channel. Protoplasma 2006, 227, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landenberger, B.; Höfemann, H.; Wadle, S.; Rohrbach, A. Microfluidic sorting of arbitrary cells with dynamic optical tweezers. Lab A Chip 2012, 12, 3177–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Sun, Z.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Bao, N.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L. The Cell Wall Regeneration of Tobacco Protoplasts Based on Microfluidic System. Processes 2022, 10, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Jin, W.; Yin, X.; Fang, Z. Single-cell analysis by electrochemical detection with a microfluidic device. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1063, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.T.; Toffalini, F.; Witters, D.; Vermeir, S.; Rolland, F.; Hertog, M.L.; Nicolaï, B.M.; Puers, R.; Geeraerd, A.; Lammertyn, J. Digital microfluidic chip technology for water permeability measurements on single isolated plant protoplasts. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 199, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Boehm, C.R.; Hibberd, J.M.; Abell, C.; Haseloff, J.; Burgess, S.J.; Reyna-Llorens, I. Droplet-based microfluidic analysis and screening of single plant cells. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, M.S.; Lintilhac, P.M. Microbead encapsulation of living plant protoplasts: A new tool for the handling of single plant cells. Appl. Plant Sci. 2016, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolik, M.; Koop, H.U. Identification of embryogenic microspores of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) by individual selection and culture and their potential for transformation by microinjection. Protoplasma 1991, 162, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, F.; Chen, M.; Schaub, P.; Wüst, F.; Zhang, D.; Schneider, S.; Groß, G.A.; Mäder, P.; Dovzhenko, O.; Palme, K.; et al. Induction of embryogenic development in haploid microspore stem cells in droplet-based microfluidics. Lab A Chip 2022, 22, 4292–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczakiewicz-Perera, P.; Winkelmann, T.; Köhler, M.; Cao, J. Droplet-based microfluidics platform for investigation of protoplast development of three exemplary plant species. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 40332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, S.; Qi, H.; Duan, X.; Han, Z.; Wang, J. Functional Characterization and Phenotyping of Protoplasts on a Microfluidics-Based Flow Cytometry. Biosensors 2022, 12, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Han, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Duan, X. An impedance-coupled microfluidic device for single-cell analysis of primary cell wall regeneration. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 165, 112374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, T.; Wang, S.; Han, Z.; Duan, X.; Wang, J. Phenotyping of single plant cells on a microfluidic cytometry platform with fluorescent, mechanical, and electrical modules. Analyst 2024, 149, 4436–4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidmann, I.; Schade-Kampmann, G.; Lambalk, J.; Ottiger, M.; Di Berardino, M. Impedance Flow Cytometry: A Novel Technique in Pollen Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Duan, X. Label-Free and Simultaneous Mechanical and Electrical Characterization of Single Plant Cells Using Microfluidic Impedance Flow Cytometry. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 14568–14575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonge, J.; Philippot, M.; Leblanc, C.; Potin, P.; Bodin, M. Impedance flow cytometry allows the early prediction of embryo yields in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) microspore cultures. Plant Sci. 2020, 300, 110586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, X. Microfluidics identify moso bamboo and henon bamboo by leaf protoplast subpopulations with single-cell analysis. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, e2400120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nezhad, A.S.; Naghavi, M.; Packirisamy, M.; Bhat, R.; Geitmann, A. Quantification of the Young’s modulus of the primary plant cell wall using Bending-Lab-On-Chip (BLOC). Lab A Chip 2013, 13, 2599–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, M.; Packirisamy, M.; Geitmann, A. Measuring the growth force of invasive plant cells using Flexure integrated Lab-on-a-Chip (FiLoC). Technology 2018, 6, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Munglani, G.; Vogler, H.; Fabrice, T.N.; Shamsudhin, N.; Wittel, F.K.; Ringli, C.; Grossniklaus, U.; Herrmann, H.J.; Nelson, B.J. Characterization of size-dependent mechanical properties of tip-growing cells using a lab-on-chip deviced. Lab A Chip 2017, 17, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascom, C.S., Jr.; Wu, S.Z.; Nelson, K.; Oakey, J.; Bezanilla, M. Long-Term Growth of Moss in Microfluidic Devices Enables Subcellular Studies in Development. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Xu, Z.; Aluru, M.R.; Dong, L. Plant chip for high-throughput phenotyping of Arabidopsis. Lab A Chip 2014, 14, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, X.; Aluru, M.R.; Dong, L. Plant miniature greenhouse. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 2019, 298, 111572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.H.; Lee, N.; Choi, G.; Park, J.K. Plant array chip for the germination and growth screening of Arabidopsis thaliana. Lab A Chip 2017, 17, 3071–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.H.; Park, J.K. Light Gradient-Based Screening of Arabidopsis thaliana on a 384-Well Type Plant Array Chip. Micromachines 2020, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, L.; Lin, X.; Xia, Z.; Cao, J.; Xu, S.; Gu, H.; Yang, H.; Bao, N. Microfluidic Devices for Monitoring the Root Morphology of Arabidopsis Thaliana in situ. Anal. Sci. 2021, 37, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Pereira, D.; Baudrey, S.; Hoffmann, E.; Ryckelynck, M.; Asnacios, A.; Chabouté, M.E. Real-time tracking of root hair nucleus morphodynamics using a microfluidic approach. Plant J. 2021, 108, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patabadige, D.E.; Millet, L.J.; Aufrecht, J.A.; Shankles, P.G.; Standaert, R.F.; Retterer, S.T.; Doktycz, M.J. Label-free time- and space-resolved exometabolite sampling of growing plant roots through nanoporous interfaces. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, W.; Moore, B.T.; Martsberger, B.; Mace, D.L.; Twigg, R.W.; Jung, J.; Pruteanu-Malinici, I.; Kennedy, S.J.; Fricke, G.K.; Clark, R.L.; et al. A microfluidic device and computational platform for high-throughput live imaging of gene expression. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanchaikasem, P.; Idnurm, A.; Selby-Pham, J.; Walker, R.; Boughton, B.A. Root-TRAPR: A modular plant growth device to visualize root development and monitor growth parameters, as applied to an elicitor response of Cannabis sativa. Plant Methods 2022, 18, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossmann, G.; Guo, W.J.; Ehrhardt, D.W.; Frommer, W.B.; Sit, R.V.; Quake, S.R.; Meier, M. The RootChip: An Integrated Microfluidic Chip for Plant Science. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 4234–4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossmann, G.; Meier, M.; Cartwright, H.N.; Sosso, D.; Quake, S.R.; Ehrhardt, D.W.; Frommer, W.B. Time-lapse Fluorescence Imaging of Arabidopsis Root Growth with Rapid Manipulation of the Root Environment Using the RootChip. Jove-J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 7, 4290. [Google Scholar]

- Fendrych, M.; Akhmanova, M.; Merrin, J.; Glanc, M.; Hagihara, S.; Takahashi, K.; Uchida, N.; Torii, K.U.; Friml, J. Rapid and reversible root growth inhibition by TIR1 auxin signalling. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Verstraeten, I.; Roosjen, M.; Takahashi, K.; Rodriguez, L.; Merrin, J.; Chen, J.; Shabala, L.; Smet, W.; Ren, H.; et al. Cell surface and intracellular auxin signalling for H(+) fluxes in root growth. Nature 2021, 599, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, H.; Alotaibi, S.S.; Pěnčík, A.; Adamowski, M.; Novák, O.; Friml, J. RALF1 peptide triggers biphasic root growth inhibition upstream of auxin biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2121058119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufrecht, J.; Khalid, M.; Walton, C.L.; Tate, K.; Cahill, J.F.; Retterer, S.T. Hotspots of root-exuded amino acids are created within a rhizosphere-on-a-chip. Lab A Chip 2022, 22, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, Z.D.; Rogers, D.T.; Littleton, J.M.; Lynn, B.C. Microfluidic capillary zone electrophoresis mass spectrometry analysis of alkaloids in Lobelia cardinalis transgenic and mutant plant cell cultures. Electrophoresis 2019, 40, 2921–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussus, M.; Meier, M. A 3D-printed Arabidopsis thaliana root imaging platform. Lab A Chip 2021, 21, 2557–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, C.E.; Shrivastava, J.; Brugman, R.; Heinzelmann, E.; van Swaay, D.; Grossmann, G. Dual-flow-RootChip reveals local adaptations of roots towards environmental asymmetry at the physiological and genetic levels. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, C.; Tayagui, A.; Hornung, R.; Nock, V.; Meisrimler, C.N. A dual-flow RootChip enables quantification of bi-directional calcium signaling in primary roots. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1040117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Karamahmutoğlu, H.; Elitaş, M.; Yüce, M.; Budak, H. Through the Looking Glass: Real-Time Imaging in Brachypodium Roots and Osmotic Stress Analysis. Plants 2019, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, K.; Mehta, S.K.; Mondal, P.K. Unveiling nutrient flow-mediated stress in plant roots using an on-chip phytofluidic device. Lab A Chip 2024, 24, 3775–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakatsu, Y.; Okada, R.; Hara, M.; Tsutsui, H.; Yanagisawa, N.; Higashiyama, T.; Arima, A.; Baba, Y.; Kurotani, K.I.; Notaguchi, M. Microfluidic Device for Simple Diagnosis of Plant Growth Condition by Detecting miRNAs from Filtered Plant Extracts. Plant Phenomics 2024, 6, 0162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakatsu, Y.; Hara, M.; Kurotani, K.I.; Arima, A.; Baba, Y.; Notaguchi, M. A multiplex microfluidic device to detect miRNAs for diagnosis of plant growth status. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Jiao, Y.; Aluru, M.R.; Dong, L. Electrospun Nanofibrous Membranes for Temperature Regulation of Microfluidic Seed Growth Chips. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2012, 12, 6333–6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, M.; Lucchetta, E.M.; Ismagilov, R.F. Chemical stimulation of the Arabidopsis thaliana root using multi-laminar flow on a microfluidic chip. Lab A Chip 2010, 10, 2147–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.H.; Chen, F.; Zhang, S.J.; Li, Y.D.; Lu, Z.S.; Kang, Y.J.; Yu, L. Multi-chamber petaloid root-growth chip for the non-destructive study of the development and physiology of the fibrous root system of Oryza sativa. Lab A Chip 2019, 19, 2383–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, S.; Seitz, K.; Krysan, P.J. A simple microfluidic device for live-cell imaging of Arabidopsis cotyledons, leaves, and seedlings. Biotechniques 2018, 64, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.X.; Chai, H.H.; Chen, F.; Yu, L.; Fang, C. A Foldable Chip Array for the Continuous Investigation of Seed Germination and the Subsequent Root Development of Seedlings. Micromachines 2019, 10, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Zeng, L.; Yu, Z.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H. A magnetically enabled simulation of microgravity represses the auxin response during early seed germination on a microfluidic platform. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2022, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atoloye, I.A.; Herrera, D.; Veličković, D.; Clendinen, C.S.; Tate, K.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Aufrecht, J.; Zeng, T.; Rai, D.; Bhowmik, A. Insight into industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) root exudation composition in a simulated soil environment: A rhizosphere-on-a-chip study. Rhizosphere 2025, 34, 101099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Lee, M.R.; Kim, C.S.; Lee, K.H. Detection of proline using a novel paper-based analytical device for on-site diagnosis of drought stress in plants. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2019, 90, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.S.; Im, M.K.; Lee, M.R.; Kim, C.S.; Lee, K.H. Highly sensitive enclosed multilayer paper-based microfluidic sensor for quantifying proline in plants. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1105, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koman, V.B.; Lew, T.T.; Wong, M.H.; Kwak, S.Y.; Giraldo, J.P.; Strano, M.S. Persistent drought monitoring using a microfluidic-printed electro-mechanical sensor of stomata in planta. Lab A Chip 2017, 17, 4015–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkbeiner, T.; Manz, C.; Raorane, M.L.; Metzger, C.; Schmidt-Speicher, L.; Shen, N.; Ahrens, R.; Maisch, J.; Nick, P.; Guber, A.E. A modular microfluidic bioreactor to investigate plant cell-cell interactions. Protoplasma 2022, 259, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurotani, K.I.; Kawakatsu, Y.; Kikkawa, M.; Tabata, R.; Kurihara, D.; Honda, H.; Shimizu, K.; Notaguchi, M. Analysis of plasmodesmata permeability using cultured tobacco BY-2 cells entrapped in microfluidic chips. J. Plant Res. 2022, 135, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massalha, H.; Korenblum, E.; Malitsky, S.; Shapiro, O.H.; Aharoni, A. Live imaging of root-bacteria interactions in a microfluidics setup. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4549–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufrecht, J.A.; Timm, C.M.; Bible, A.; Morrell-Falvey, J.L.; Pelletier, D.A.; Doktycz, M.J.; Retterer, S.T. Quantifying the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Plant Root Colonization by Beneficial Bacteria in a Microfluidic Habitat. Adv. Biosyst. 2018, 2, 1800048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Sasse, J.; Lewald, K.M.; Zhalnina, K.; Cornmesser, L.T.; Duncombe, T.A.; Yoshikuni, Y.; Vogel, J.P.; Firestone, M.K.; Northen, T.R. Ecosystem Fabrication (EcoFAB) Protocols for the Construction of Laboratory Ecosystems Designed to Study Plant-microbe Interactions. Jove-J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 10, 57170. [Google Scholar]

- Jabusch, L.K.; Kim, P.W.; Chiniquy, D.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, B.; Bowen, B.; Kang, A.J.; Yoshikuni, Y.; Deutschbauer, A.M.; Singh, A.K.; et al. Microfabrication of a Chamber for High-Resolution, In Situ Imaging of the Whole Root for Plant-Microbe Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, C.L.; Khalid, M.; Bible, A.N.; Kertesz, V.; Retterer, S.T.; Morrell-Falvey, J.; Cahill, J.F. In Situ Detection of Amino Acids from Bacterial Biofilms and Plant Root Exudates by Liquid Microjunction Surface-Sampling Probe Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 2022, 33, 1615–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, A.; Pandey, S. Plant-in-chip: Microfluidic system for studying root growth and pathogenic interactions in Arabidopsis. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 263703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noirot-Gros, M.F.; Shinde, S.V.; Akins, C.; Johnson, J.L.; Zerbs, S.; Wilton, R.; Kemner, K.M.; Noirot, P.; Babnigg, G. Functional Imaging of Microbial Interactions with Tree Roots Using a Microfluidics Setup. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.; Gauci, F.X.; Noblin, X.; Galiana, E.; Attard, A.; Thomen, P. Kinetics of zoospores approaching a root using a microfluidic device. Phys. Rev. E 2025, 111, 024411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetisen, A.K.; Jiang, L.; Cooper, J.R.; Qin, Y.; Palanivelu, R.; Zohar, Y. A microsystem-based assay for studying pollen tube guidance in plant reproduction. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 2011, 21, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Sugimoto, N.; Higashiyama, T.; Arata, H. Quantification of pollen tube attraction in response to guidance by female gametophyte tissue using artificial microscale pathway. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2015, 120, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, N.; Higashiyama, T. Quantitative assessment of chemotropism in pollen tubes using microslit channel filters. Biomicrofluidics 2018, 12, 024113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.W.; Halverson, L.J.; Dong, L. A miniaturized bioelectricity generation device using plant root exudates to feed electrogenic bacteria. Sens. Actuators A-Phys. 2022, 342, 113649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, L.W.; Yong-Villalobos, L.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; Patil, G.B. Development of High-Quality Nuclei Isolation to Study Plant Root-Microbe Interaction for Single-Nuclei Transcriptomic Sequencing in Soybean. Plants 2023, 12, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Akram, Z.; Bule, M.H.; Iqbal, H.M. Advancements and potential applications of microfluidic approaches-A review. Chemosensors 2018, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, N.; Kozgunova, E.; Grossmann, G.; Geitmann, A.; Higashiyama, T. Microfluidics-Based Bioassays and Imaging of Plant Cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.; Alline, T.; Cascaro, L.; Lin, E.; Asnacios, A. Mechanical resistance of the environment affects root hair growth and nucleus dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L. Responses of chrysanthemum cells to mechanical stimulation require intact microtubules and plasma membrane-cell wall adhesion. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2007, 26, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Bai, L. Elevated CO2 and reactive oxygen species in stomatal closure. Plants 2021, 10, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, G.J.; Boghi, A.; Affholder, M.C.; Keyes, S.D.; Heppell, J.; Roose, T. Soil carbon dioxide venting through rice roots. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 3197–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbarma, P.; Kumar, C.M.; Kumari, M.; Makarana, G.; Gangola, S.; Kumar, S. Role of quorum sensing in plant–microbe interactions. In Advanced Microbial Techniques in Agriculture, Environment, and Health Management; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard, O.; Schneider, S.; Dehne, M.; Bahnemann, J.; Palme, K.; Welsch, R.; Dovzhenko, O.; Yu, Q.; Köhler, M.; Cao, J.; et al. Smarter cell sorting: Droplet microfluidics meets pick-and-place sorting. Lab A Chip 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhai, L.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, J.; Xu, W.; Li, X.; Liu, K.; Zhong, T.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Recent advances in microfluidics for the early detection of plant diseases in vegetables, fruits, and grains caused by bacteria, fungi, and viruses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 15401–15415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant Research Application Field | Microfluidic Device/Platform | Cell Type/Tissue/Organ of Interest | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-based approaches | |||

| Single cell and protoplast analysis | Chamber-based microfluidic device | Protoplasts, protonema cells, somatic cells | [28,29,30,31,32] |

| Single cell trapping devices | Protoplasts, pollen tubes, ovules | [33,34,35,36,37,38] | |

| Microwells array | Protoplasts | [39,40] | |

| Size-based microarrays | Protoplasts, chloroplasts | [41,42] | |

| Channel-based microfluidic devices | Protoplasts, pollen tubes, somatic cells, root hairs | [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] | |

| Droplet-based microfluidics | Protoplasts, microspores | [53,54,55,56,57,58] | |

| Impedance-based microfluidic devices | Protoplasts, mesophyll cells, microspores, pollens | [59,60,61,62,63,64,65] | |

| Microfluidic devices for cell stretching and compression | Pollen tubes | [66,67,68] | |

| Development and structural characterization | |||

| Morphological/functional phenotyping | Chamber-based microfluidic device | Protonema tissue | [69] |

| Microfluidic chip arrays | Germinating seeds | [70,71,72,73] | |

| Channel-based microfluidic devices | Root hairs, roots | [74,75] | |

| Microfluidic devices coupled with sampling fluidics | Roots | [76] | |

| Root array | Roots | [77] | |

| Root-on-a-chip device | Roots | [78,79,80,81,82,83] | |

| Rhizosphere-on-a-chip device | Roots | [84] | |

| Microfluidic capillary zone electrophoresis | Root extracts | [85] | |

| Environmental interactions and responses | |||

| Abiotic stress response | Root-on-a-chip devices | Roots | [86,87] |

| Microfluidic devices for precise control of environmental conditions | Roots | [88] | |

| Microchannel-based microfluidic devices | Roots, plant extracts | [89,90,91,92,93,94] | |

| Chamber-based microfluidic devices | Roots, leaves | [95,96] | |

| Microfluidic chip arrays | Roots | [97] | |

| Microgravity generating devices | Seeds | [98] | |

| Rhizosphere-on-a-chip devices | Roots | [99] | |

| Paper-based sensors | Plant extracts | [100,101] | |

| Microfluidic-printed electro-mechanical sensors | Leaves | [102] | |

| Cell communication and plant-microbe interactions | Modular microfluidic bioreactors | Somatic cells | [103] |

| Trapping devices | Somatic cells, roots | [104] | |

| Microfluidic chambers for co-cultivation | Roots | [105,106,107,108] | |

| Soil-analog microfluidic devices | Roots | [84,109] | |

| Microchannel-based devices | Pollen tubes, roots | [110,111,112,113,114,115] | |

| Bioelectricity generating devices | Roots exudates | [116] | |

| Microfluidic-based single-nucleus RNA-seq | Root extracts | [117] | |

| Device Type | Purpose | Characteristics | Cell Type, Organism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culturing chambers array | Protoplasts long-term cultivation and imaging | Array of 36 PDMS culturing chambers (diameter of 4 mm, depth of 500 µm) covered with glass or PDMS covers, placed in a square dish | Protoplasts, Nicotiana tabacum | [28] |

| Microchamber-based pentagonal array | Protoplasts fusion, cultivation and imaging | Five culture chambers (900 µm in width, 3200 µm in length and 55 µm) arranged in a pentagonal array, each containing Double micro-column (30 µm in length, 20 µm in width, and 55 µm in height) line for protoplasts trapping | Protoplasts, Nicotiana tabacum | [29] |

| U-shaped trapping microfluidic platform | Cultivation and microscopical imaging | Array of 112 flow-through U-shaped traps (inner length 60 µm, inner width 45 µm), arranged in 14 lines | Protoplasts and spores, Physcomitrella patens | [33] |

| Shallow microfluidic chamber | Protonema culture and real-time cytoskeleton imaging under highly inclined and laminated optical sheet microscopy (HILO) | Cultivation chamber (2 mm wide, 12 mm long, with height varying between 4.5 and 15 µm), containing supporting pillars | Protonema cells, Physcomitrella patens | [30] |

| Microfluidic antibody capture (MAC) chip | Single cell protein expression quantification | 50 analysis chambers (volume of 0.75 or 4.5 nL) with a micro-printed antibody spot individually connected to one reservoir channel used for cell and solutions delivery | Protoplasts, Arabidopsis thaliana | [32] |

| Microfluidic chip for single and double cell trapping | Controlled induction and study of protoplast fusion dynamics | Channel height of 56 µm, trapping features of minimum width 90 µm, consisting of 20 or 40 µm diameter posts arranged in a double U-shape. | Protoplasts, Arabidopsis thaliana | [34] |

| Microfluidic chip with an orifice array | Electrofusion of protoplasts | Two protoplast chambers between glass electrodes (425 µm spacing), separated by a Kapton sheet with a 5 µm-diameter, 25 µm-thick orifice array | Protoplasts, Phalaenopsis, Raphanus raphanistrum subsp. sativus | [36] |

| Microwells array | Shaping the cells in controlled geometries, microscopical imaging | Microchambers of circular, triangular, square and rectangular shapes with diameter of 15–40 µm and height 20 µm | Protoplasts, Arabidopsis thaliana | [39] |

| Microwells array | Cortical tension generation via cells confinement and cortical microtubules (CMTs) imaging | Microwells of various dimensions: 15 × 20 µm, 14 × 14 µm and 12 × 40 µm used for protoplasts confinement in various osmotic pressure conditions (280, 600 or 800 mOsmol·L−1) | Protoplasts, Arabidopsis thaliana | [40] |

| Microvessels array | Trapping and microscopical imaging | Chamber consisting of microvessels 72.8 µm × 52 µm | Protoplasts, Nicotiana tabacum | [35] |

| Microcage array | Immobilization and cultivation of ovules | Array of microcages of 650 µm length and varying width: 150, 200, 250 and 300 µm with PDMS pillars surrounding trapped ovule, for long-term ovule culture 200 and 250 µm wide microcages were used | Ovules, Arabidopsis thaliana | [37] |

| Device Type | Purpose | Characteristics | Cell Type, Organism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic chip with integrated concave and convex–concave microsieve arrays | Protoplasts collection and lysis | Main flow channel (600 µm width) and a protoplast sieving array (with a square length of 25 or 50 µm and distance between microsieves of 10 µm) with collecting channels (300 µm width) | Protoplasts, Phalaenopsis Chiada Pioneer | [41] |

| Deterministic lateral displacement (DLD) arrays integrated into one microfluidic chip | Size-based Chloroplast separation | Four parallel DLD arrays with 10-µm pillars and gap spacings from 5 to 11 µm, each providing a distinct critical diameter and enabling simultaneous size-based separation of chloroplasts in the 2–5 µm range | Chloroplasts, Spinacia oleracea L. | [42] |

| Microchannel with hydrodynamic trap | Analysis—electrical permeabilization for extracting cytosolic molecules | Microchannel with hydrodynamic trap for clusters of intact plant cells analysis | Protoplasts, Arabidopsis thaliana | [43] |

| Microchannel based device | Pollen tube guidance and cultivation | Multiple microchannels 5–20 µm wide | Pollen tubes, Torenia fournieri | [44] |

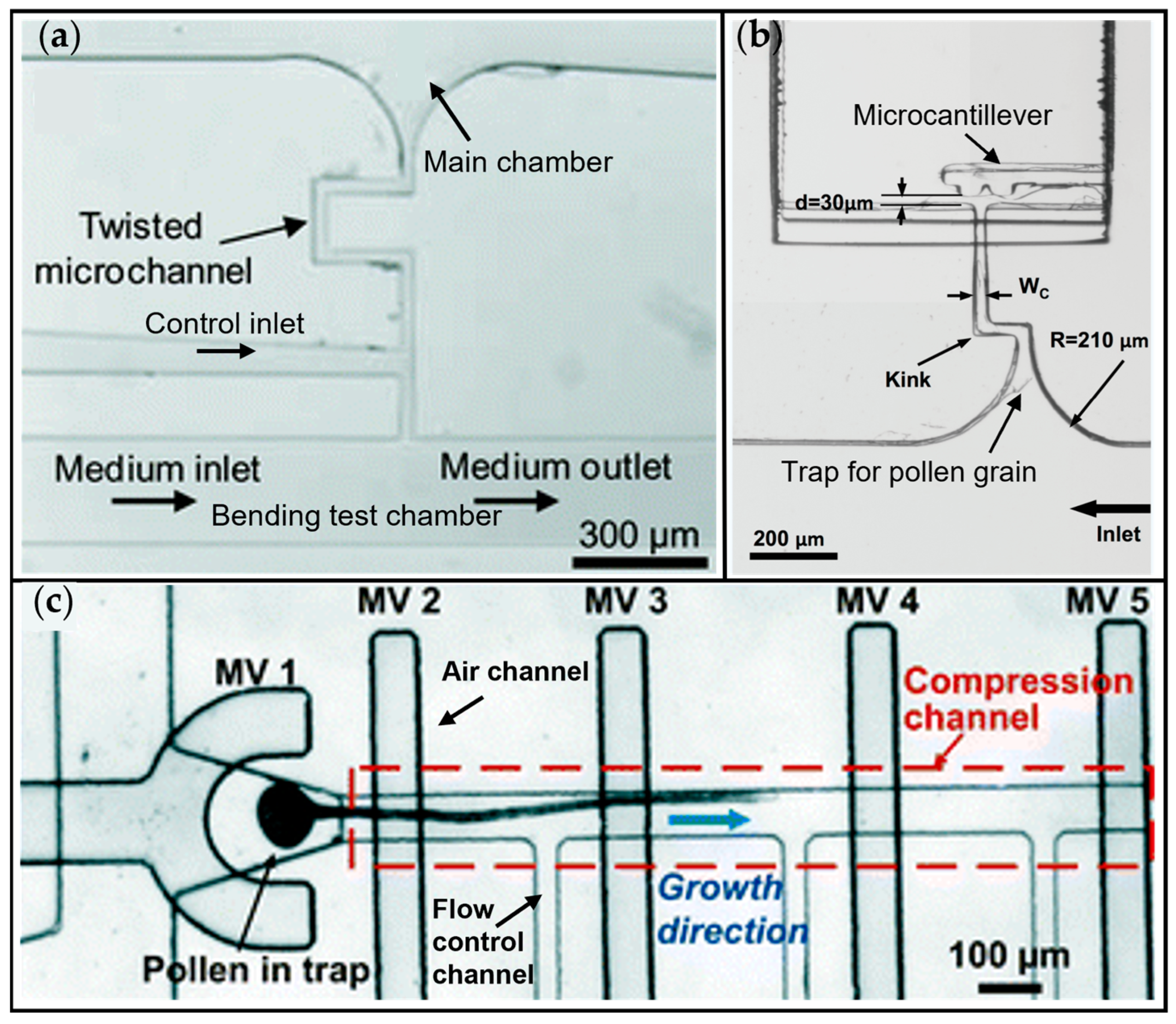

| TipChip— microfluidic network | Pollen tube guidance and cultivation | Network of microchannels 30 µm wide and 80 µm deep for pollen tube growth with additional structure elements: kink for locking the pollen grain, sections of air-media interface and additional inlet for creating chemical gradient | Pollen tubes, Camelia japonica | [45] |

| Microfluidic network based on the TipChip | Real-time Manipulation and analysis of pollen tube growth direction | Planar fluidic network with a depth of 80 µm, consisting of a main chamber into which the pollen grains are injected, two traps with adjacent microchannels into which the pollen tubes elongate, and two side inlets for the injection of different media into the main chamber | Pollen tubes, Camelia japonica | [46] |

| Microchannel-based device | Cell cultivation through extremely narrowed spaces | Growth channels for tip growing cells with microgaps of 1 or 4 µm width | Pollen tubes, T. fournieri Root hairs, A. thaliana Somatic cells, P. patens | [47] |

| Microchannel-based device | Cell guidance and testing of cell wall rupture | 500 µm long channels with narrowed gaps of various wide-length parameters: 4–20, 7–20 and 4–400 | Pollen tubes, Arabidopsis thaliana | [48] |

| Microchannel-based device | Protoplasts cultivation and imaging | Main microfluidic channel (13.8 mm long, 0.1 mm high and 1 mm wide) with oval region for current reduction, posts for decreasing of the shear stress and columns line (12 µm gaps between each column) for trapping protoplasts | Protoplasts, Nicotiana tabacum | [49] |

| Microchannel-based sorting chip | Cell sorting | 100-µm-wide, 80-µm-deep channels guide cell flow; sorting is triggered by bright-field and/or fluorescence-based classification, directing cells into either the sorted or unsorted outlet | Protoplasts, Arabidopsis thaliana | [50] |

| Crossed microfluidic chip | Cell wall regeneration, protoplasts cultivation and imaging | Three crossed microfluidic channels with a width of 250 µm, depth of 60 µm, and length of 30 mm (5–6 mm crossed zone) per device, 4 devices on a chip | Protoplasts, Nicotiana tabacum | [51] |

| Lab-on-a-chip device | Pollen grain trapping, pollen tube cultivation | Microfluidic network with hydrodynamic trapping of pollen grains with growth microchannels of various shapes | Pollen tubes, Camilla japonica | [38] |

| Droplet-based microfluidic device | Protoplasts cultivation | Top plate of the channel equipped with magnet, allowing for lining of magnetic microparticles labeled protoplasts for visualization | Protoplasts, Arabidopsis thaliana | [53] |

| Droplet-based microfluidic device | Protoplasts handling and fluorescence measurement analysis + sorting | Flow-focusing generation of droplets with protoplasts encapsulation, followed by on-chip fluorescence measurements | Protoplasts, Marchantia polymorpha | [54] |

| Microdroplet generation system | Protoplasts handling and cultivation | Agarose droplets generated via droplet chip junction | Protoplasts, Nicotiana tabacum | [55] |

| Microdroplet generation system | Identification and development of embryogenic microspores | Microspores individually introduced to the required volume transmitted via tubing to the tip of the capillary (final droplet volume 35–100 nL, coated by 800–1000 nL of mineral oil | Microspores, Hordeum vulgare | [56] |

| Droplet-based microfluidics | Induction and optimization of embryogenic development in microspores | Droplets of volume around 120 nL generated using 6-channel droplet generator and cultivated in polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tubing of 0.5 mm inner diameter, separated from each other by perfluoromethyldecalin (PP9) | Microspores, Brassica napus | [57] |

| Droplet-based microfluidics | Protoplasts cultivation | Droplets of volume around 300 nL generated using 6-channel droplet generator and cultivated in PTFE tubing of 0.5 mm inner diameter, separated from each other by PP9 | Protoplasts, N. tabacum, Brassica juncea, Kalanchoe daigremontiana | [58] |

| Device Type | Purpose | Characteristics | Cell Type, Organism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic chip-electrochemical detection (ED) system | Detection of ascorbic acid in single cells | Device consists of sample, separation and waste channels, each with a depth of 30 µm and a width of 80 µm, arranged in the double T-injector. Protoplasts are separated, lysed and analyzed using changing voltage (100–50 V for injection, 1000 V for lysis and 0.90 V for AA detection) | Protoplasts, Triticum aestivum | [52] |

| Microfluidic flow cytometer | Analysis—fluorescence detection Auxins level during cell wall regeneration Cytosolic redox status | Flow-through channel 60 µm high and 40 µm wide, accommodating single cells | Protoplasts, Arabidopsis thaliana, Petunia | [59] |

| Microfluidic impedance spectroscopy platform | Analysis—impedance measurement characterization of single cell at different plant cell wall regeneration | Platform contains a sensing trap and reference trap (which remains empty for the time of measurement) | Mesophyll cells, Arabidopsis thaliana | [60] |

| Microfluidic flow cytometry platform with fluorescent, mechanical and electrical modules | Analysis—fluorescence microscopy and impedance measurement | Platform contains flow-through channel accommodating single cells, equipped in electrodes for electrical-mechanical detection | Protoplasts, Arabidopsis Columbia | [61] |

| Microfluidic-based impedance flow cytometry platform | Analysis—impedance measurement at the frequency 0.5 to 12 MHz | Immature and mature pollen grains, Nicotiana tabacum (microscpores), Cucumis sativus, Capsicum anuum, Solanum lycopersicum | [62] | |

| Simultaneous mechanical and electrical characterization, At the frequency 0.5 and 5 MHz | Protoplasts, Arabidopsis thaliana, Populus trichocarpa | [63] | ||

| Microfluidic-based impedance flow cytometry platform | Cell viability measurements, detection of different microspore developmental stages during pollen formation and androgenesis | The Coulter system with coupled microfluidic chips containing electrodes and a microchannel of various sizes | Microspores, Triticum aestivum | [64] |

| Microfluidic flow cytometry platform | Characterization of cells subpopulations based on the biophysical properties using direct-current insulator-based dielectrophoresis (DC-iDEP) | Platform contains flow-through channel accommodating single cells, equipped in electrodes for electrical-mechanical detection | Protoplasts, Lophatherum gracile Brongn, Phyllostachys heterocycle ‘Pubescens’ | [65] |

| Microdevice | Investigated Tissue, Organism | Function | Structure Characteristics | Measured Parameter | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bending-Lab-On-Chip (BLOC) | Pollen tube, Camellia japonica | Bending of the pollen tube through fluid loading | Twisted growth microchannel to prevent backward movement of pollen, control channel and bending test chamber for measurement | Bending and rotational deflection Determination of the Young’s modulus | [66] |

| Flexure integrated Lab-on-a-Chip (FiLoC) | Pollen tube, Camellia japonica | Guiding pollen tube against microcantilever | Pollen grain is trapped and the pollen tube is guided through a growth channel against a microcantilever for invasive growth force measurement | Growth force, Growth dynamics upon interaction with a mechanical obstacle | [67] |

| Lab-On-Chip device | Pollen tube, Lilium longiflorum | Indentation of pollen tubes | Trapping microvalve for pollen grain immobilization, pollen tube growth channel with indentation microvalve | Compression and stretch ratio characterization | [68] |

| Phenotyping Target | Device Design | Functionality | Measured Parameters | Plant Species | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissues growth and development | Growth chamber (30 µm deep and volume of 1.36 µL) with central inlet sector and surrounding flow control channels, bonded to a coverslip | Long-term live imaging | Growth rate, Cell expansion rate—area, length, width, cell division, Cytoskeleton degradation | Physcomitrella patens | [69] |

| Root and shoot growth and development | Chip with seed holding sites, root and shoot growing regions and 1.8 mm channel for media flow | Live imaging and monitoring of root and shoot phenotypes | Root length, hypocotyl length, cotyledon surface area | Arabidopsis thaliana | [70] |

| Root and shoot growth and development (up to 30 days) | Miniature greenhouse—plant chip with light intensity and temperature sensor in insulated space | Environmental control | Root length, hypocotyl length, | Arabidopsis thaliana | [71] |

| Germination and shoot growth | Plant array chip—300 2 × 2 mm square arrays grouped in 5 regions | Monitoring multiple replicants phenotypes, nutrient gradient control | Germination rate, radicle length | Arabidopsis thaliana | [72] |

| Germination, growth and etiolation | Plant array chip with 384 wells | Light gradient control | Germination rate | Arabidopsis thaliana | [73] |

| Root morphology | Microchannel-based device with channels width 150–400 µm | Growth space definition, live imaging | Root length, root diameter root hair length, number of root hair | Arabidopsis thaliana | [74] |

| Root hair nucleus morphodynamics | 1.5 cm-long channels for main root growth (250 µm wide and 100 µm deep) connected via two arrays of lateral 400 µm-long perpendicular channels for root hairs expansion (20 µm wide and deep) | Live imaging | Position of the tip, tip average speed, nucleus to tip position | Arabidopsis thaliana | [75] |

| Spatial and temporal profiling of root exudates | Main channel for root growth, nanoporous membrane and two channels for sampling fluidics | Live imaging, Metabolite sampling | Metabolite concentration, diffusion | Arabidopsis thaliana | [76] |

| Gene expression dynamics | RootArray—growth chamber with 64 wells, liquid and gaseous chambers | Automated live imaging, environmental control | Fluorescence intensity (indicating gene expression) | Arabidopsis thaliana | [77] |

| Root growth and development | Root-TRAPR system—internal oval root growth chamber with transparent walls for microscopic observation and an external structural frame | Live imaging | root length, root surface area, average root diameter | Cannabis sativa | [78] |

| Root growth and development | RootChip—eight individual microchannels for root growth and observation 800 µm wide and 100 µm high | Live imaging, Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) measurements | Intracellular sugars (Glc, Gal) levels, root length, growth rate | Arabidopsis thaliana | [79,80] |

| Root exudation dynamics in soil-like environments | Rhizosphere-on-a-chip with synthetic porous structure, coupled with liquid micro-junction surface sampling probe mass spectrometry (LMJ-SSP-MS) | Long-term growth and imaging of roots, visualization and chemical analysis of root exudate distribution via mass spectrometry | Spatial distribution of amino acid hotspots | Brachypodium distachyon | [84] |

| Metabolomic profiling | microfluidic capillary zone electrophoresis-mass spectrometry (CZE-MS) | High-throughput alkaloid analysis with minimal sample prep; targeted and untargeted MS/MS | Relative abundance of alkaloids, electropherogram features, mass spectra | Lobelia cardinalis | [85] |

| Type of the Stress | Investigated Tissue, Organism | Cultivation Condition | Microdevice | Analysis Method | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drought | Roots, Arabidopsis thaliana | Media supplemented with 10 or 20% PEG-6000 | RootChip | Light microscopy | [86] |

| Salinity, Deficiency of Pi | Roots, Arabidopsis thaliana | Media with 100 mM NaCl, Media with deficient Pi (0.01 mM) | Dual-Flow-RootChip | Calcium imaging—fluorescence Microscopy Light microscopy | [87] |

| Salinity, Drought | Roots, Arabidopsis thaliana | 100 mM NaCl, 20% PEG-6000 | Bi-directional-dual-flow-RootChip | Calcium imaging—fluorescence microscopy | [88] |

| Nutrient flow | Primary root, Brassica juncea | Nutrient flow ranging from 0 to 1.2 mL/hr | Microfluidic channel | Light microscopy | [90] |

| Drought | Roots, Oryza sativa | 0,6% agar culture media containing 0%, 5%, 10%, 20% or 30% PEG-6000 | Multi-chamber petaloid root-growth chip | Light microscopy, Gene expression analysis | [95] |

| Salinity, Drought | Roots, Nicotiana tabacum | 150 mM NaCl, 10% PEG-6000 | Foldable Plant Array Chip | Light microscopy | [97] |

| Microgravity | Seed, Arabidopsis thaliana | Treatment of seeds with IAA, Kyn and Gd3+ | Microfluidic chip with 5 channels for seed cultivation | Light and fluorescence microscopy | [98] |

| Drought | Roots, Brachypodium distachyon | 20% PEG | Microfluidic channel | Light microscopy | [89] |

| Deficiency of Pi | Leaf extracts | Media with deficient Pi (0.05 mM) | Multichannel microfluidic chip with a detection area | Sandwich hybridization—fluorescence detection of miR399 | [91,92] |

| Drought | Plant extract, Arabidopsis thaliana | Plants cultivated in pots with dry soil | Paper-based microfluidic sensor | Colorimetric proline detection | [100,101] |

| Drought | Leaf stomata, Spathiphyllum wallisii | Plants cultivated in pots with soil with or without watering | Electro-mechanical sensor | Optical stomatal aperture Measurement Electrical and Raman measurements | [102] |

| Heat | Seed and root, Arabidopsis thaliana | Seeds placed in water, temperature in the range 25.3 °C—37.2 °C | Microfluidic Seed Growth Chips (SGC) incorporated with electrospun nanofibrous membranes (ENMs) | Light microscopy | [93] |

| Device | Type of Cell–Cell Interaction | Device Structure | Experimental Multiplicity | Investigation Method | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modular microfluidic bioreactor | Somatic cell–cell (cell line BY-2, N. tabacum) | Connectable chips containing 800 µL cell chamber and perfusion chamber separated by nanoporous membrane | 1, with possibility of multiple cell types combined in separate chambers | Proliferation factor measurement | [103] |

| Metabolic synergy between somatic cells (cell strains from seedlings of Catharanthus roseus) | HPLC–DAD-ESI–MS/MS for alkaloid detection | ||||

| Fungal phytotoxicity (cell line BY-2, N. tabacum an Neofusicoccum parvum) | Cell mortality assay | ||||

| Microfluidic trapping device | Plasmodesmata permeability between tobacco BY-2 cells | Channels for trapping plant filaments | 1 cell population | Confocal microscopy, Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) measurement | [104] |

| Tracking root interaction system (TRIS) | Root-bacteria (Arabidopsis thaliana and Bacillus subtilis) | 9 channels of 160 µm height, each with 3 individual ports: inlet and outlet for bacteria introduction and one for introduction of germinated seeds | 9 | Light and fluorescence microscopy | [105] |

| Channel-based device | Root-bacteria colonization (Arabidopsis thaliana and strains: Pantoea sp. YR343 and Variovarax sp. CF313) | Main channel for root growth 150 µm high, 200 µm wide and 3.8 mm long, surrounding treatment chamber 20 µm high and 8 areas with injection channels | 1 | Light and fluorescence microscopy | [106] |

| Imaging EcoFab | Root-microbes interactions (Brachypodium distachyon and Pseudomonas simiae strains) | Oval chamber covered with pillars, allowing for media flow while flat root growth against the coverslip | 1 | confocal microscopy | [107,108] |

| Y-channel device, Open format and Soil-analog microfluidic device | Root-bacterial biofilm (Populus trichocarpa and Pantoea YR343) | Devices allowing for the growth of the roots and formation of rhizosphere, with live sampling of root exudates | 1 | Mass spectrometry | [109] |

| Plant-in-chip microchannel based device | Root-pathogens (Arabidopsis thaliana interacting with sugarbeet nematode or Phytophtora sojae) | 8 parallel straight microchannels 80 µm high, 350 µm wide, 1 cm long, connected with thin vertical channels for pathogens introduction | 8 | Light microscopy | [110] |

| RMI-chip | Root-microbe interactions (roots of Populus tremuloides and Pseudomonas fluorescens) | Root growth channels 100 µm high, 800 µm wide and 36 mm long with two inlets for media and bacteria inoculation | 12 | Light and fluorescence microscopy | [111] |

| Channel-based device for root growth | Root-pathogens (Arabidopsis thaliana and Phytophthora parasitica) kinetics of zoospores in the vicinity of the root | Root growth channels 150 µm high and of various width: 0.5, 1, 2 or 4 mm | up to 8 | Light microscopy | [112] |

| Miniaturized plant-microbial fuel cell (mPFMC) | Root exudates as carbon source for electricity generating bacteria (rice plants and bacterial strains: Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14) | Chamber for hydroponic plant growth, carbon cloth for bacteria growth, separated from each other via semipermeable filtering membrane | 1 | Electrochemical measurements, GC-MS for root exudates analysis, SEM for bacterial biofilm observation | [116] |

| Droplet-based single nucleus RNA sequencing (sNucRNA-seq) platform | Root-symbiotic bacteria (Glycine max and Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens USDA 110) | Microfluidic channels included in the sequencing platform | High-throughput analytical platform | RNA sequencing | [117] |

| Type of the Device | Purpose | Characteristics | Cell Type, Organism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microsystem-based microfluidic device simulating ovule microenvironment | Assessment of pollen tube guidance in response to ovule-derived cues | Main groove (1 mm wide, 5 mm long) with side chambers (250–1000 µm2) for ovule placement or gradient generation, depth along whole device around 500 µm | Pollen tubes, Arabidopsis thaliana | [113] |

| T-junction and crossroad microchannel devices | Assessment of pollen tube guidance in response to ovule-derived cues | Microchannels of 500 µm in width and 25 µm in height. The distance between the center of style inlet and: T-junction—3.5 mm; crossroad—2 mm | Pollen tubes, Torenia fournieri | [114] |

| Microslit-based microfluidic chip | Quantitative assessment of pollen tube chemotropism | Thin microslit channel array (2–16 µm in width and 5 µm in height) and thick channels (90 µm in height) with style inlet, sample reservoir (containing ovary) and blank reservoir | Pollen tubes, Torenia fournieri | [115] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Marczakiewicz-Perera, P.; Köhler, J.M.; Cao, J. Application of Microfluidics in Plant Physiology and Development Studies. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010464

Marczakiewicz-Perera P, Köhler JM, Cao J. Application of Microfluidics in Plant Physiology and Development Studies. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):464. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010464

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarczakiewicz-Perera, Paulina, Johann Michael Köhler, and Jialan Cao. 2026. "Application of Microfluidics in Plant Physiology and Development Studies" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010464

APA StyleMarczakiewicz-Perera, P., Köhler, J. M., & Cao, J. (2026). Application of Microfluidics in Plant Physiology and Development Studies. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010464