1. Introduction and Motivation

Energy consumption in industrial manufacturing, together with its environmental impact, has become a critical driver for innovation in energy efficiency. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, manufacturing accounts for nearly 40% of total electricity use in the United States [

1]. Similarly, the European Association of Machine Tool Industries reports that over 99% of the environmental impacts in discrete part manufacturing originate from electricity consumption [

2]. These data highlight the urgent need for sustainable practices and energy-aware operations in modern production systems.

Traditionally, manufacturing systems have been designed and operated with a focus on classical performance metrics such as throughput, product quality, and inventory levels. However, recent years have seen a shift toward embedding energy efficiency as a core operational objective, alongside traditional KPIs [

3]. In discrete machining processes—such as milling, turning, drilling, and sawing—energy consumption can be decomposed into start-up operations (e.g., powering computers, pumps, and coolant systems), runtime operations (e.g., idle spindle time, tool changes), and material removal operations (i.e., actual machining) [

4,

5]. Empirical studies indicate that material removal accounts for only around 15% of total energy usage, with the majority stemming from baseline operational loads [

5,

6]. This motivates the investigation of strategies targeting idle energy consumption, especially during periods of low production activity.

Machine switch-off/on policies have emerged as a promising approach to reduce idle energy consumption [

7]. While effective in lowering baseline power draw, they introduce a trade-off: reactivation delays can negatively affect responsiveness to production demands. Achieving an optimal balance between energy savings and operational readiness is therefore essential.

Recent advances in manufacturing control enabled by Industry 4.0 technologies allow for sophisticated management of machine states, integrating energy efficiency with traditional operational objectives. In particular, the concept of “smart” Statistical Process Control (SPC) has evolved to leverage IoT sensors, real-time monitoring, and data-driven decision-making [

8]. These approaches can handle stochastic demand, machine variability, and dynamic system behavior, providing a foundation for predictive and adaptive control. In parallel, modern control charts have evolved to handle complex and functional data. For example, Capezza et al. [

9] proposed the Adaptive Multivariate Functional EWMA (AMFEWMA) control chart, while [

10] introduced the Adaptive Multivariate Functional Control Chart (AMFCC) framework, capable of monitoring multivariate and functional quality characteristics in real time. These methods illustrate how traditional SPC tools can be extended for data-intensive, high-variability industrial environments.

The emerging paradigm of Industry 5.0 emphasizes human-centric, sustainable, and collaborative manufacturing, integrating humans, machines, and advanced analytics. Recent reviews on smart factories in Industry 5.0 [

11] highlight the importance of human–machine collaboration, sustainable resource management, and data-driven process optimization. In this context, approaches combining SPC, Big Data analytics, and adaptive control enable predictive, real-time decision support, consistent with the principles of Industry 5.0 [

12]. It should be noted that Statistical Process Control is not employed in this study as a classical inferential methodology. The proposed framework does not assume stationarity or distributional stability of system variables. Instead, SPC concepts are adopted in an operational, signal-based sense to support adaptive control decisions in dynamic production environments.

Building on these insights, this study proposes a novel integration of quality-management-inspired control charts with adaptive, data-driven switch-off/on policies for pull-based production lines. Unlike existing adaptive or stochastic switch-off strategies, which typically rely on predictive models, learning algorithms, or optimization-based online controllers, the proposed approach introduces Statistical Process Control (SPC) logic as an explicit operational control mechanism rather than as a monitoring tool. In particular, downstream buffer levels are treated as a statistical process, and control-chart signals are directly used to update switch-off thresholds in closed loop. This design enables adaptive behavior without requiring demand forecasting, processing-time estimation, or training phases, resulting in a parameter-light, interpretable and shop-floor-ready control architecture. The contribution of the paper therefore lies not in proposing adaptation per se, but in defining a novel, SPC-driven control logic that governs machine state decisions in pull-controlled flow lines, fully aligned with Industry 4.0 data availability and Industry 5.0 human-centric principles.

Despite the extensive body of literature on energy-aware production control, a critical theoretical shortcoming remains insufficiently addressed. Most existing studies focus on the development of adaptive, stochastic, or data-driven switch-off strategies aimed at minimizing energy consumption, often assuming that performance degradation can be mitigated through parameter tuning, predictive models, or optimization-based control schemes. However, under stochastic and non-stationary operating conditions, such approaches frequently introduce unintended service-level deterioration, including increased flow times, higher tardiness, or reduced delivery reliability.

As a result, a central research tension emerges between aggressive energy-saving policies and the preservation of operational stability. While static switch-off rules are known to achieve significant energy reductions, they lack responsiveness to system dynamics and are particularly vulnerable to performance degradation. Conversely, more sophisticated adaptive approaches often rely on complex optimization or forecasting mechanisms, limiting their transparency and practical applicability. Addressing this unresolved tension—namely, how to preserve energy efficiency while avoiding systematic service-level degradation through simple and interpretable control logic—remains an open research problem.

Unlike conventional static thresholds, the method continuously monitors key system indicators—such as buffer occupancy, work-in-progress, and customer demand rates—and dynamically adjusts control limits to respond to stochastic fluctuations. By embedding this adaptive mechanism in a simulation model, the study identifies operating conditions that maximize energy savings without degrading service levels, demonstrating a practical, scalable approach for smart, sustainable manufacturing systems.

The experimental analysis is intentionally conducted on a stylized flow line to ensure interpretability of the control mechanisms. Accordingly, claims regarding robustness and applicability refer to the behavioral and architectural properties of the proposed control logic, rather than to empirical scalability with respect to system size or structural complexity.

The paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature on switch-off policies and energy efficiency in manufacturing, highlighting the state-of-the-art in adaptive control and SPC.

Section 3 introduces the reference production context.

Section 4 presents the proposed model in detail, followed by simulation experiments in

Section 5.

Section 6 discusses the numerical results, and

Section 7 concludes with managerial implications and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

Energy consumption in manufacturing remains a major factor shaping industrial sustainability targets, reinforcing the need for energy-aware control, scheduling, and monitoring strategies. Global institutions such as the International Energy Agency [

13] emphasize that industry continues to account for a substantial share of total energy demand, calling for data-driven technologies and intelligent supervisory methods capable of coordinating energy and operational performance. In this context, the transition toward Industry 4.0 and the emerging paradigm of Industry 5.0 increase the relevance of intelligent, adaptive, and human-centric energy management frameworks.

2.1. Switch-Off Policies and Stopping Strategies

A foundational stream of research focuses on switch-off/on policies aiming to reduce baseline energy consumption by powering down machines during idle periods. Early analytical models [

14] highlight the trade-off between energy savings and penalties such as warm-up delays or transient quality disturbances. Simulation-based studies confirm that coordinated switch-off strategies can enhance energy performance in pull-controlled lines [

15] and that extensions to more complex flow lines with fractional task allocations further improve energy responsiveness [

16]. More recent work emphasizes the importance of synchronization with buffer dynamics, WIP variability, and demand fluctuations, showing that data-driven policies can substantially improve the energy–performance trade-off [

17,

18,

19]. These models form the basis for adaptive approaches that adjust machine states according to real-time system conditions.

2.2. Energy-Efficient Scheduling

A second major research domain concerns energy-aware production scheduling, traditionally addressed through offline optimization. Fernandes et al. [

20] review energy-efficient job shop scheduling, noting the prevalence of metaheuristics to handle NP-hard complexity. More comprehensive analyses [

21,

22,

23] highlight the growing adoption of hybrid scheduling approaches that jointly optimize consumption, throughput, makespan, and service levels. However, many scheduling models oversimplify startup transients and ignore the dynamic variability inherent in real systems. This gap becomes particularly evident when compared to real-time adaptive control strategies, as emphasized in this Special Issue.

2.3. Dynamic and Online Control Strategies

Beyond offline scheduling, industry is moving toward online, adaptive control policies that adjust to real-time conditions. Frigerio et al. [

24] developed an online policy for energy-efficient state control, addressing the startup times needed when machines are switched off. Similarly, recent simulation-based work demonstrates the value of stochastic stopping policies under uncertainty [

18]. Jiang et al. [

19] proposed a stochastic-task-driven energy-saving control method for machine tools, confirming that adaptive responses to fluctuating demand are key to reducing unnecessary energy consumption.

These trends align closely with Industry 4.0 principles, where continuous data streams, CPS feedback loops, and cloud-based analytics support real-time machine state transitions, and with Industry 5.0, which seeks robust and sustainable control strategies that adapt to disruptions.

2.4. Digital Technologies: AI, Digital Twins, IoT

Digitalization is accelerating the adoption of energy-aware manufacturing. Li et al. [

25] proposed a digital twin framework for batch processes, while Alex and Johnson [

26] introduced an IoT-enabled architecture for resource optimization. Expert systems have also been systematically reviewed for improving industrial energy efficiency [

27]. Artificial intelligence plays an increasingly central role, with applications in forecasting, anomaly detection, and adaptive optimization across both manufacturing and smart grids [

28]. System-level surveys confirm their growing relevance in sustainable production [

29]. These technologies represent core building blocks of Industry 4.0, enabling cyber-physical synchronization and high-resolution energy monitoring, and support Industry 5.0 goals by fostering resilient and sustainable system behavior through explainable and human-supervised intelligence.

2.5. Monitoring and Statistical Process Control (SPC)

In parallel, researchers are extending statistical process control (SPC) tools to energy monitoring. Traditional charts such as Shewhart, CUSUM, and EWMA are now adapted to adaptive, multivariate, and time-varying environments. Muzayyanah et al. [

30] applied advanced regression techniques to capture nonlinear industrial relationships, while [

31] introduced adaptive EWMA charts for dynamic environments. Capezza et al. [

32] further extended SPC with multivariate functional monitoring. These tools complement Industry 4.0 data infrastructures, where sensors and digital twins generate continuous streams of high-dimensional data. Their integration with stopping policies offers a foundation for smart, self-adaptive switch-off thresholds, fully aligned with the real-time, data-centric logic of digital manufacturing.

2.6. Empirical Applications in Machining and Case Studies

Machining and discrete-part manufacturing remain key application areas, as fixed energy components (cooling, electronics, idle power) often dominate consumption. Pawanr and Gupta [

33] reviewed recent advances in machining energy efficiency, while Pimenov et al. [

34] highlighted challenges in reducing machining energy demand. Firdaus and Samat [

35] demonstrated the practical application of energy monitoring for sustainable maintenance. These studies illustrate both the opportunities and barriers to adoption—including operator acceptance, readiness times, and quality considerations—which are central themes in Industry 5.0, where technology must coexist with human-centric constraints and sustainability objectives.

2.7. SPC Integration Within Industry 4.0, Industry 5.0 and Smart Manufacturing

The evolution toward Industry 4.0 and, more recently, Industry 5.0, has expanded the role of Statistical Process Control (SPC) from a conventional quality monitoring tool to an integral component of cyber-physical production management. In modern smart factories, dense IoT sensor networks and cyber-physical systems provide continuous and high-resolution data streams that enable SPC methods to operate in real time, supporting predictive and adaptive decision-making. Several contributions document how digital transformation enhances SPC capabilities through big data analytics, multivariate monitoring and machine-learning-assisted anomaly detection [

36,

37]. Within Industry 4.0, SPC integrates with data-driven and model-based tools to create hybrid monitoring architectures capable of capturing nonlinear and time-varying behaviors in production systems. Recent studies show how IoT-enabled SPC frameworks can address energy monitoring, equipment degradation and machine idle patterns using real-time sensing [

38]. These approaches support dynamic and energy-aware policies by providing early warnings of threshold violations, which is essential for optimizing switch-off/on decisions in flow lines.

Digital twins further extend the potential of SPC by enabling virtual experimentation and predictive simulation. Digital-twin-assisted SPC systems can test alternative control limits, estimate the impact of shutdown delays and validate anomalies before they propagate to the physical system [

39]. This supports a transition from descriptive monitoring to prescriptive control, which aligns directly with the dynamic switch-off strategies proposed in this study.

The Industry 5.0 paradigm introduces a complementary focus on resilience, sustainability and human-centricity. In this context, SPC serves as an interpretable and trustworthy interface that mediates between automated decision-support systems and operator expertise. Recent work highlights how human-in-the-loop SPC, supported by AI-enhanced analytics, strengthens responsiveness to disturbances, assists in energy-aware decision-making and promotes sustainable operations [

40,

41]. SPC thus becomes an enabling technology for creating resilient production systems capable of adapting to fluctuating workloads, energy variability and uncertain demand.

The proposed framework—combining SPC monitoring, adaptive switch-off thresholds and a digital twin—fits naturally within these trajectories. SPC provides the real-time analytical backbone, the digital twin offers predictive validation, and the adaptive switch-off logic delivers actionable energy-saving interventions. This synergy reflects the emerging Industry 4.0/5.0 direction toward explainable, data-driven and sustainability-oriented operational control, addressing several research gaps described in recent reviews.

2.8. Research Gaps and Future Directions

From a production control and operations management perspective, a number of shared conclusions and limitations emerge across the reviewed literature. A broad consensus exists on the effectiveness of switch-off policies and energy-aware control strategies in reducing machine-level energy consumption, particularly when idle and blocking states are explicitly modeled. At the same time, existing approaches differ substantially in how they address the interaction between energy-saving actions and system-level performance.

A recurrent limitation is that many energy-aware control strategies implicitly assume that performance degradation can be compensated through tuning, prediction, or optimization, without explicitly modeling the feedback mechanisms through which switch-off decisions propagate along the production line. As a result, service-level effects such as increased flow time, tardiness, or loss of delivery reliability are often treated as secondary outcomes rather than as structural consequences of control decisions.

From a mechanism-oriented viewpoint, this reveals a theoretical blind spot in the literature: while energy efficiency is extensively studied at the machine or local control level, the dynamic coupling between energy-saving policies and workload accumulation in stochastic production systems remains insufficiently understood. In particular, there is limited empirical analysis of how simple, interpretable control logics can balance energy efficiency and operational stability without relying on complex optimization or forecasting schemes. The present study positions itself within this gap by focusing on the behavioral effects of adaptive switch-off control on system-level performance rather than on energy minimization alone.

Despite significant advances, several gaps remain. Transition modeling is often oversimplified, and startup transients are underrepresented in scheduling formulations. Monitoring and control strategies are seldom integrated into closed-loop frameworks capable of real-time adaptation. More importantly, while many contributions propose adaptive, stochastic, or data-driven switch-off policies, adaptation is typically achieved through heuristic rules, optimization routines, or learning-based controllers. In these approaches, adaptation is often opaque, parameter-intensive, or tightly coupled to specific demand or processing-time models. In contrast, the literature rarely explores the use of Statistical Process Control as a closed-loop control logic for machine state management. SPC is predominantly employed as a monitoring or diagnostic tool, rather than as a mechanism that actively updates policy parameters based on statistically significant deviations in system behavior. As a result, a gap exists for control architectures that (i) embed SPC logic directly into operational decision-making, (ii) enable adaptive switch-off threshold updates driven solely by observed system dynamics, and (iii) remain interpretable and human-supervisable, in line with Industry 5.0 principles. There is a growing need for integrative frameworks that combine SPC-inspired signal logic monitoring; adaptive switch-off policies; digital twin environments; AI-based prediction and optimization; and human-centered supervision consistent with Industry 5.0 principles.

Hybrid approaches could bridge data-driven prediction and explainable control, while empirical deployments would strengthen validation and industrial adoption.

3. Reference Context

The reference context considered in this study is a pull-controlled flow line, a common configuration in discrete-part manufacturing where production is synchronized with customer demand rather than driven by forecasted schedules. Such pull systems are particularly suitable for Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 environments, as they can leverage real-time data from sensors and IoT devices to dynamically adjust production, reduce energy consumption, and improve responsiveness. The line consists of m machines arranged sequentially, each separated by intermediate buffers that regulate the flow of work-in-progress (WIP). This configuration enables a balance between machine utilization and system responsiveness, as buffers act as decoupling points that absorb variability in processing times and machine availability [

14,

24]. In smart manufacturing contexts, these buffers can also serve as monitoring nodes where SPC or digital twin-based analytics support adaptive control decisions. At the end of the line, a final buffer serves as the interface between the production system and external demand. When a customer order arrives, it is immediately fulfilled if sufficient inventory is available in this buffer. If inventory is insufficient, the order is backordered-recorded and queued for delivery once the buffer is replenished through ongoing production. This mechanism ensures that unmet demand is not lost but carried forward, aligning production with actual consumption while preserving system continuity. Backordering is particularly relevant in pull-controlled lines, where the objective is to minimize excess inventory while avoiding service disruptions. In Industry 4.0/5.0-enabled lines, real-time monitoring of the final buffer can further enhance responsiveness and support data-driven decision-making for adaptive energy-saving strategies.

A key feature of this production line is that raw items are assumed to be always available at the first buffer, ensuring uninterrupted supply to the initial machine. Each subsequent machine is associated with an input buffer of finite capacity, denoted as Km. When a buffer reaches capacity, the upstream machine is blocked and cannot release additional items until downstream capacity becomes available. This blocking mechanism is a central dynamic of flow lines, as it captures the trade-off between throughput efficiency and WIP accumulation.

From an operational perspective, each machine

m can be in one of four states [

14]:

- -

Working: the machine is actively processing an item, consuming the highest power level, Pworkm.

- -

Idle: the machine is operational and ready, but no part is available from upstream. It consumes a reduced standby power level, Pidlem.

- -

Off: the machine is completely shut down, yet it still consumes a residual “standby” power, Poffm.

- -

Warm-up: the machine transitions from off to operational (idle or working). During this setup phase, which lasts for a duration Twum, it consumes a specific warm-up power level, Pwum.

The interplay of these states has significant implications for energy consumption and production performance. For instance, frequent switching between off and warm-up can reduce energy waste but may introduce delays or increase wear. Conversely, prolonged idle states avoid startup penalties but contribute to higher baseline energy consumption. In a pull-controlled system, where production is directly linked to actual demand and WIP buffers, these trade-offs are especially relevant.

This modeling framework reflects real-world production systems—such as assembly lines, machining cells, and automated flow lines—where efficiency depends not only on throughput and service levels but also on energy-aware operational policies, including switch-off strategies and adaptive scheduling. By analyzing this context, the study provides insights into how energy-saving measures can be integrated into demand-driven manufacturing systems, bridging the gap between productivity and sustainability.

4. Switch off Policies

Energy-aware production control has increasingly relied on switch-off policies to balance throughput performance with energy savings in flow lines. Among the policies proposed in the literature, the Downstream Policy (DP) is often employed as a benchmark, particularly because it aligns naturally with pull-controlled systems, where machine operation is regulated by downstream demand signals [

15].

In the standard DP, machine operation is governed by the level of the immediate downstream buffer. A machine is switched off when the buffer content reaches or exceeds an upper threshold, denoted as NDoff, and it is switched on when the buffer content falls below a lower threshold, NDon. The thresholds must be carefully tuned for the specific characteristics of the manufacturing system, and they often require re-design if system conditions (e.g., demand rate, variability, or machine reliability) change.

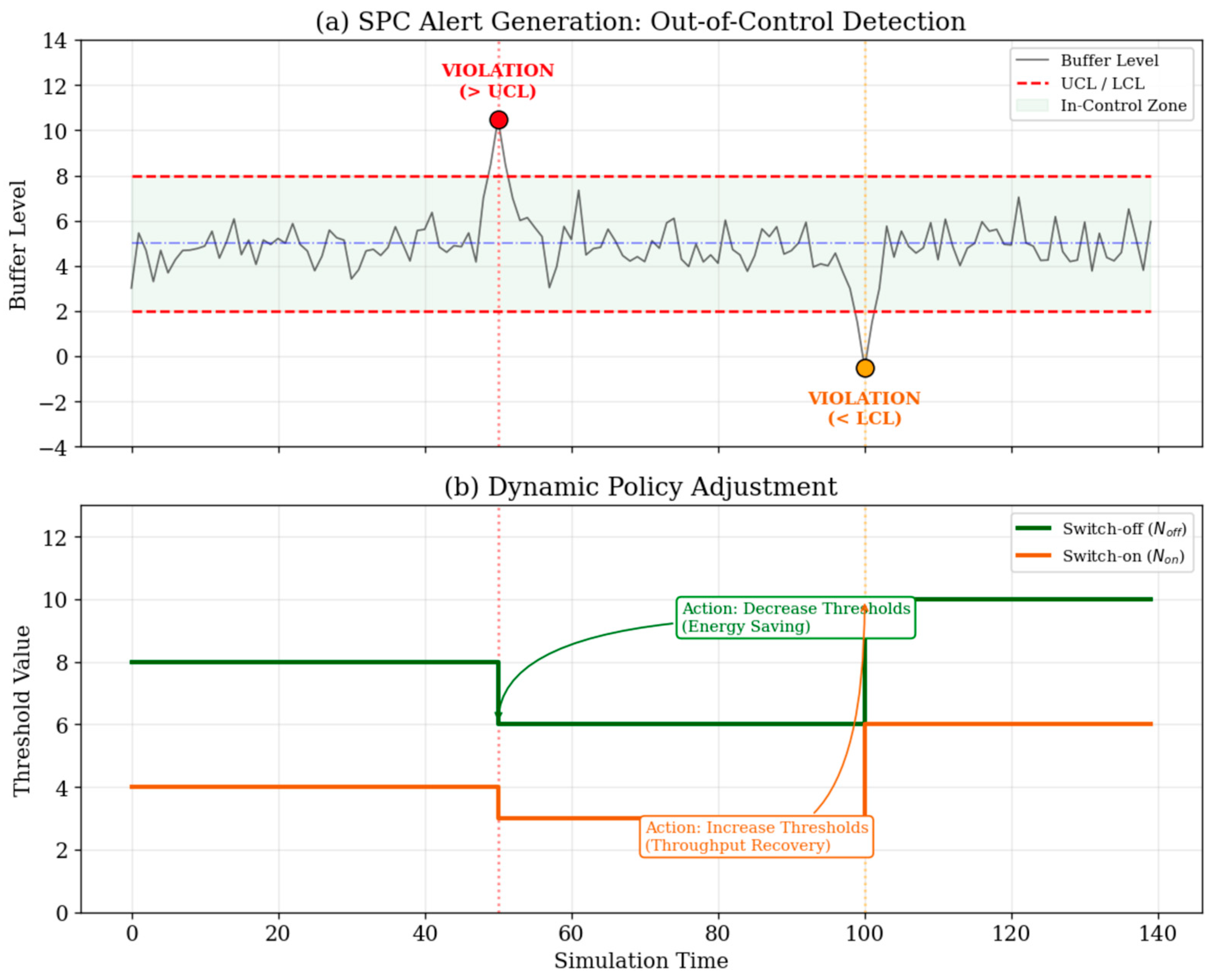

To overcome this rigidity, the proposed policy introduces a dynamic threshold adjustment mechanism inspired by the logic of control charts used in quality management. Control charts, originally developed by Shewhart, are a statistical tool for monitoring process stability. It is important to clarify that Statistical Process Control is not employed in this study as a classical inferential tool. Buffer levels in pull-controlled flow lines are inherently non-stationary and endogenously driven by demand and control actions. Consequently, control limits are not interpreted as statistical confidence bounds but as adaptive reference thresholds used to detect persistent deviations in system dynamics. They plot a process variable against time with a central line representing the average performance and upper and lower control limits (UCL/LCL), usually set at three standard deviations from the mean. When the variable remains within the control limits, the process is considered stable. Conversely, an observation outside the limits signals an out-of-control condition, prompting corrective actions. In analogy, the proposed switch-off policy continuously monitors the downstream buffer level and updates the thresholds accordingly. Initially, the thresholds NDoff and NDon are set identically to those of the benchmark DP. Then, for each downstream buffer (including the final one), the average buffer level is computed over a moving window of length Av. This moving average serves as the central line of the control chart. Upper and lower control limits (UCL/LCL) are defined as the central line ± three standard deviations, also estimated over the moving window. The use of short moving windows does not aim at estimating long-run process parameters or ensuring distributional convergence. Rather, it represents a design choice to balance noise filtering and responsiveness, which is consistent with the real-time control objective of the proposed policy.

Following a periodic review strategy, every Tp period the switching thresholds are reassessed (see

Figure 1):

If the observed buffer level remains within the UCL and LCL, the thresholds are left unchanged.

If the buffer level exceeds the UCL (out-of-control point on the high side), it indicates persistent buffer over-accumulation. In this case, both thresholds (NDoff, NDon) are reduced by one unit, preserving their relative distance. This adjustment lowers the average buffer content and prolongs machine off-times, enhancing energy savings.

Conversely, if the buffer level falls below the LCL, it reflects a risk of frequent starvation. Both thresholds are increased by one unit, again keeping their relative gap unchanged. This raises the average buffer level, ensuring more reliable machine utilization at the cost of slightly higher energy consumption.

Finally, a safeguard mechanism ensures that thresholds remain bounded within predefined maximum and minimum feasible values, preventing extreme settings that could either lead to excessive idle capacity or overly frequent switch-ons/offs.

This adaptive policy thus enables the production system to self-tune switch-off thresholds in response to observed buffer dynamics, maintaining a balance between energy efficiency and service level. By embedding SPC principles into operational control, the method improves robustness under variable demand and stochastic disturbances compared to static policies.

It is important to clarify how the proposed policy differs from generic adaptive or reactive threshold-adjustment heuristics. First, the adaptation mechanism is not driven by instantaneous buffer fluctuations but by statistically significant deviations identified through control-chart logic, reducing sensitivity to noise and transient variability. Second, the policy does not optimize an explicit cost or objective function, nor does it require demand forecasting, processing-time modeling, or learning-based parameter estimation. Threshold updates are triggered exclusively by out-of-control signals derived from observed buffer dynamics.

Finally, the magnitude of adaptation is intentionally incremental and bounded, ensuring stability, interpretability, and ease of supervision by human operators. These characteristics distinguish the proposed SPC-driven policy from both static switch-off rules and more complex data-driven controllers, positioning it as an explainable and robust control architecture rather than a black-box optimization approach.

In the proposed framework, out-of-control signals do not indicate statistical instability of the process. Instead, they act as operational indicators of sustained buffer accumulation or depletion, triggering corrective threshold adjustments. This interpretation reflects current Industry 4.0 practices, where SPC-inspired tools are increasingly used as real-time, explainable decision-support mechanisms in non-stationary and feedback-driven systems.

5. Simulation Environment

The production line consists of three sequential machines, each coupled with a finite-capacity buffer, except for the first machine, which has an unlimited supply of raw materials. While the proposed policy is initially formulated for a three-machine system, it can also be generalized to represent three manufacturing stages, potentially encompassing multiple machines and auxiliary equipment within each stage. Consequently, the analytical framework developed in this study is applicable to a broad range of production systems organized into three distinct stages. In this configuration, the process begins with an initial stage that continuously receives raw materials, followed by an intermediate processing stage, and culminates in a final stage directly responsible for fulfilling production orders. The downstream buffers are subject to finite storage constraints, whereas the final buffer must satisfy customer demand. When demand exceeds the capacity of the final buffer, excess orders are backlogged until sufficient capacity becomes available for processing. This structured modeling approach enables a comprehensive assessment of system performance and provides a robust foundation for optimizing production flow and buffer management across multiple stages.

The first set of simulations is conducted under steady-state conditions to evaluate the baseline behavior of the proposed dynamic policy. Machine processing times are fixed at 10 time units to establish a balanced flow line, thereby isolating the effect of the switch-off policy. Buffer capacities are set to 10 units, while customer demand follows an exponential distribution with a mean interarrival time of 10, ensuring a representative workload and meaningful evaluation of customer-related performance indicators. The total simulation horizon is 28,800 time units to assure an opportune horizon for the simulation results.

The thresholds for the downstream policy are initially set at NDoff = 9 and NDon = 5 to achieve a balanced trade-off between customer-oriented performance and buffer utilization. The moving average window (Av) and the periodic review interval (Tp) are varied between 8 and 18 time units (in increments of 2) to identify the parameter values that yield the most effective results. The exploration of (Av, Tp) values is not intended as a global optimization procedure. Instead, it aims to assess the robustness and stability of the proposed control logic across a reasonable parameter range. The reported configuration corresponds to a representative high-performing region rather than to a uniquely optimal solution. The parameters of the fixed switch-off policy are selected to represent a stable and commonly adopted benchmark configuration, consistent with prior literature, rather than to minimize or maximize a specific performance metric. The purpose of the comparison is therefore architectural rather than parametric.

To further assess robustness, scenarios with process variability are considered:

Two main categories of performance measures are investigated in the simulations: customer-oriented metrics and manufacturing system-oriented metrics (see

Table 1).

Customer performance measures aim to capture the quality of service delivered to the end user:

Average customer waiting time, representing the responsiveness of the system;

Standard deviation of customer waiting time, reflecting service time variability and reliability;

Average customer queue length, an indicator of the typical backlog faced by customers;

Maximum customer queue length, highlighting worst-case congestion conditions;

Total number of fulfilled orders, a direct measure of service level and throughput capability.

Manufacturing system performance measures are designed to evaluate internal efficiency and resource utilization:

Work-in-process (WIP), capturing the average inventory level circulating within the system, which is strongly related to lead time and operational efficiency;

Total energy consumption, reflecting the impact of switch-off policies on energy usage and enabling an assessment of the trade-off between productivity and sustainability.

The simulation models are implemented in Simul8® (version 32), with raw materials always assumed to be available for the first machine. This assumption eliminates variability associated with supply arrivals, ensuring that performance is evaluated solely as a function of the proposed policy and system dynamics. A terminating simulation approach is adopted, and for each experimental scenario, a sufficient number of replications is performed to guarantee a 95% confidence level with a maximum error margin of 5% for each performance measure. The number of replications is therefore not predefined. For each experimental scenario, replications are executed sequentially until the half-width of the confidence interval for each performance measure satisfies the prescribed 95% confidence level and 5% maximum relative error. Independent random number streams are used across replications, while identical seed sequences are applied across different control policies within the same scenario to ensure a fair and unbiased comparison. Since a terminating simulation framework is adopted, no steady-state detection or warm-up period is required.

6. Numerical Results

The always-on policy is included as a reference configuration to normalize performance indicators and to quantify relative improvements introduced by switch-off strategies. The fixed threshold policy represents a commonly adopted class of static energy-aware control rules, selected to provide a stable and interpretable benchmark rather than an exhaustive exploration of static parameter configurations. The comparative analysis is therefore intended to highlight structural differences between static and adaptive control logics under identical operating conditions. All results are expressed as percentage change relative to the benchmark “always-on” model; negative values indicate reductions. Percentage variations relative to the always-on configuration are used to support a comparative evaluation of control policies across heterogeneous performance indicators. The always-on policy serves as a neutral reference configuration rather than as a realistic operational benchmark, enabling consistent normalization of results. The last column (“Dynamic vs. Fixed”) reports the percentage change in the proposed dynamic policy relative to the fixed on/off policy (with NDoff = 9 and NDon = 5). Energy is computed using 5 kWh (working), 2 kWh (idle, including waiting + blocking), and 0 kWh (off). In the numerical experiments, the off state is associated with zero energy consumption as a simplifying assumption adopted for comparative purposes. The warm-up state is explicitly modeled in terms of time delay but does not introduce a separate energy category; its energy consumption is included in the idle energy level together with waiting and blocking states. This representation ensures a consistent and parsimonious energy accounting framework within the simulation model. Throughput (total fulfilled orders) is identical across all models and is therefore omitted. The reported dynamic-policy results correspond to the best tested pair (Av, Tp) = (16, 18) among {8, 10, …, 18}{8, 10, …, 18}.

For clarity, it is important to distinguish between insights that are directly supported by the reported simulation experiments and considerations that are more exploratory in nature. The experimental results provide empirical evidence regarding the effects of adaptive threshold adjustment on energy consumption, throughput stability, and congestion-related indicators under the analyzed scenarios.

Conversely, implementation-oriented recommendations and tuning guidelines discussed in the following paragraphs—such as alternative threshold ranges, adaptive update frequencies, or integration with higher-level control architectures—should be interpreted as forward-looking design considerations. These aspects are proposed based on the observed system behavior and on established production control principles, but they are not explicitly validated by the current experimental campaign.

The exploration of the parameter space is not recalled as a formal optimization procedure. No single objective function is defined, and no Pareto-based or weighted aggregation of performance measures is employed. Instead, parameter combinations are evaluated through a comparative analysis of multiple indicators, including energy consumption, throughput-related metrics, and service-level performance. The parameter pair reported in the numerical results is selected as representative of a region exhibiting stable and well-balanced behavior, rather than as a unique optimal solution. This choice aims to illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed control logic under conditions where energy savings are preserved while service-related performance improvements are consistently observed.

The simulation results are reported as the percentage difference compared to the benchmark (always-on model) and the percentage difference between the proposed dynamic policy and the fixed switch-off policy. The results of the proposed policy are reported for the better cases of average mobile and periodic review periods. The total number of fulfilled orders is the same for the three models; therefore, it is not reported in the tables. The total energy consumption is computed considering the working power of 5 kWh, idle (waiting summed to blocking state) of 2 kWh and 0 kWh for the off state.

All reported performance indicators correspond to sample mean estimates computed across independent replications. The number of replications for each scenario is adaptively determined to guarantee a 95% confidence level with a maximum relative error of 5% for each metric. Percentage variations reported in the following tables are derived from these mean values and are therefore supported by statistically controlled confidence intervals.

Table 2 reports the simulation results comparison in the steady conditions.

Relative to always-on, the fixed policy inflates average customer queue length by +543% and average waiting time by +546%. The dynamic policy cuts these penalties by roughly half (queue +236%, wait +236%), yielding −56.6% (queue) and −56.9% (wait) vs. fixed. Variability also drops markedly (−48.8% in the standard deviation of waiting time vs. fixed).

Both on/off strategies deliver large WIP reductions (~−38.6% to −38.8%) and energy savings (~−11.0%) relative to always-on. The dynamic policy matches the fixed policy on both dimensions (differences within ~0.3 percentage points). Switching machines off saves energy and WIP but hurts customer service compared to always-on; the dynamic thresholds recover ~50–57% of the service loss without sacrificing WIP or energy benefits.

Table 3 reports the simulation results for the case of machine processing times following a uniform distribution in the interval [

8,

12].

Against always-on, penalties remain substantial (queue +210%, wait +210% under the dynamic policy), but the dynamic controller again halves the fixed-policy penalties (−54.0% queue; −54.2% wait; −47.4% variability vs. fixed).

WIP drops by −37.8% (fixed) and −35.8% (dynamic) vs. always-on; energy by ~−10.9% for both. The small WIP gap (~2 percentage points) suggests the dynamic policy accepts slightly higher WIP to stabilize service under stochastic processing times, with no material energy penalty. With moderate, system-wide variability, the control-chart-driven adaptation preserves energy savings and substantially improves service relative to a static on/off rule.

Table 4 reports the simulation results for the case of Machine 3, which fluctuates between 10 and 13, with periodic shifts every 1000 time units.

When only the last stage fluctuates (10 → 13 time units), the dynamic policy still improves over the fixed rule but more modestly: −19.9% (queue), −20.2% (wait), and −16.9% (variability) vs. fixed. Relative to always-on, penalties remain high (queue +443%, wait +445%).

WIP reductions stay large (−39.7% fixed; −40.8% dynamic), and energy savings remain near −9.4% for both.

A downstream-localized disturbance weakens the benefit of global threshold adaptation. Because adjustments are incremental (±1) and triggered by out-of-control evidence, the controller may react conservatively to a structural bottleneck at the last stage, improving service only ~15–20% vs. fixed while keeping energy and WIP gains intact.

Table 5 reports the simulation results for the case of Machine 3, which fluctuates between 10 and 13, with periodic shifts every 500 time units.

With faster alternations, the dynamic policy’s advantage increases: −36.0% (queue), −36.1% (wait), and −29.8% (variability) vs. fixed. Relative to always-on, penalties are still large (queue +395%, wait +397%), but materially lower than with the fixed policy. WIP reductions remain ~−39%, and energy ~−9.5%, with negligible differences between fixed and dynamic.

More frequent deviations produce more control-chart signals, prompting quicker threshold updates and larger service gains than in the slower-drift case, again without sacrificing energy or WIP benefits.

The percentage differences for queue length and waiting time are very large due to the small values assumed by the benchmark.

Table 6 reports the absolute values for queue length and waiting time for the cases simulated.

The main cross-scenario takeaways are the following:

- -

Energy and WIP benefits are robust. Across all scenarios, on/off control yields ~9–11% energy savings and ~36–41% WIP reductions vs. always-on. The dynamic policy preserves these gains relative to the fixed rule.

- -

Service trade-offs vs. always-on are inevitable, but the dynamic policy meaningfully mitigates them:

- ○

Steady/balanced or system-wide variability: ~50–57% improvement vs. fixed on queuing and waiting.

- ○

Downstream-localized variability: ~20–36% improvement vs. fixed, depending on the disturbance period.

- -

Controller sensitivity to disturbance structure. Benefits shrink when variability is localized at the last stage and switches slowly (1000-unit period) and grow when shifts are more frequent (500-unit period), because the control chart generates more timely adjustments.

- -

Throughput neutrality. Identical fulfilled orders confirm that improvements are achieved without sacrificing output; the trade-off is primarily between service quality and energy/WIP.

The main practical implications and tuning guidance are the following:

- -

Choose Av and Tp to match disturbance time scales. Shorter windows and review periods increase responsiveness at the cost of noisier adjustments; longer windows smooth noise but may lag structural shifts. The observed differences between 1000 vs. 500-unit disturbances underscore this trade-off.

- -

Consider adaptive step sizes. Instead of ±1 updates, magnitude-proportional adjustments (e.g., based on distance beyond UCL/LCL or consecutive violations) can accelerate convergence under persistent shifts, especially for downstream bottlenecks.

- -

Localize thresholds. Allow buffer-specific limits (particularly at the last stage) to better handle stage-specific variability without over-correcting upstream.

- -

Guard banding remains essential. Min/max bounds on thresholds prevent extreme oscillations and protect service levels during transient regimes.

- -

Policy choice by objective. If service quality is paramount, always-on remains the upper bound but at higher energy/WIP. The dynamic policy is a high-leverage compromise, retaining nearly all energy and WIP gains of a fixed on/off rule while substantially improving customer-facing metrics.

In sum, the proposed control-chart-driven policy consistently dominates the fixed on/off rule on customer-oriented performance without giving up its inventory and energy advantages. Its benefits are strongest when the disturbance pattern aligns with the controller’s review cadence and window size—providing clear guidance for data-driven tuning in deployment.

7. Conclusions and Future Development Paths

This study has investigated the integration of dynamic switch-off policies into a three-stage production line through a simulation-based approach. The results clearly demonstrate that the proposed policy significantly improves customer-related performance measures—reducing average queue length and waiting times by approximately 50–56% compared to fixed policies. Crucially, these improvements are achieved without compromising system efficiency: total energy consumption and work-in-process (WIP) remain reduced by ~11% and ~38%, respectively, comparable to aggressive static policies. This dual benefit highlights the potential of dynamic strategies to effectively balance operational performance and energy efficiency in modern manufacturing systems.

Beyond the specific numerical results, the present study offers broader implications for production control and energy efficiency research. The findings highlight that energy-aware control policies should not be evaluated solely based on their ability to reduce energy consumption but also on how their decision logic interacts with workload propagation and service-level dynamics in stochastic production systems. From this perspective, adaptive switch-off strategies can be interpreted as control mechanisms that regulate the timing of capacity availability rather than as purely energy-saving devices.

Importantly, the results suggest that preserving energy efficiency does not necessarily require increasingly complex optimization or predictive frameworks. Instead, simple and interpretable adaptive rules may achieve a more favorable balance between energy savings and operational stability, provided that they explicitly account for system congestion signals. This insight contributes to the production control literature by emphasizing behavioral mechanisms over algorithmic sophistication in the design of energy-aware policies.

The applicability of these findings is subject to several boundary conditions. The analysis is limited to a flow-line configuration with stochastic processing times and machine failures, centralized control logic, and simplified energy modeling assumptions. The conclusions therefore apply primarily to systems where switch-off decisions directly affect local capacity availability and where energy performance is assessed in relative rather than absolute terms. Caution is required when extrapolating the results to large-scale, heterogeneous, or human-in-the-loop production systems, which may exhibit additional structural and organizational constraints.

From a production control and operational decision-making perspective, the proposed dynamic threshold adjustment can be interpreted as a decision mechanism that regulates the timing of capacity availability rather than as a mere technical enhancement of switch-off rules. By continuously adapting switch-off thresholds in response to congestion-related signals, the control logic implicitly balances competing objectives—energy efficiency and service-level stability—without requiring explicit multi-objective optimization or predictive modeling.

This mechanism-level interpretation contributes to production control theory by illustrating how simple, interpretable decision rules can shape system-level behavior in stochastic environments. In particular, dynamic threshold adjustment acts as a feedback-based coordination device that moderates the propagation of workload fluctuations along the production line. Framing the contribution at this level highlights its relevance beyond the specific numerical results, offering insights into the design of adaptive control policies that are both operationally meaningful and analytically transparent.

From a managerial perspective, the findings provide actionable pathways to resolve the traditional “productivity vs. sustainability” trade-off. First, the adoption of context-dependent rules allows managers to meet strict energy targets without the fear of degrading service levels or delivery times. Second, the implementation barrier is low: unlike “black-box” AI solutions, the proposed framework relies on Statistical Process Control (SPC) logic. Since SPC is a standard, trusted tool in quality management, shop-floor operators can easily understand and interact with the control system. Finally, the system offers operational resilience, autonomously adapting to fluctuations in processing times and reducing the need for manual parameter retuning by production managers.

Integrating these dynamic policies with Industry 4.0 tools—such as real-time IoT data collection and digital twins—further enhances adaptive capabilities. These technologies enable continuous adjustment of machine states in response to real-time demand and energy pricing, supporting the evolution toward smart, energy-aware, and resilient production systems.

Despite these contributions, the study presents limitations that open avenues for future research. The numerical analysis is limited to a three-machine flow line, which enables a clear investigation of control dynamics but does not support direct empirical claims on large-scale or structurally heterogeneous manufacturing systems. Extending the proposed framework to larger and more diverse system configurations is therefore required to assess scalability in quantitative terms. First, the analysis focused on heuristics; future work could extend the approach by integrating reinforcement learning to update policy parameters in real time. Second, broader stress-testing under high volatility or correlated failures would provide deeper insights. Third, future studies could incorporate economic metrics, such as dynamic energy pricing or carbon footprint penalties, to translate operational gains into quantifiable financial benefits. Finally, combining this framework with human-in-the-loop supervision represents a promising direction to achieve sustainable, human-centric manufacturing.