Damping Performance of Manganese Alloyed Austempered Ductile Iron

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Material Preparation

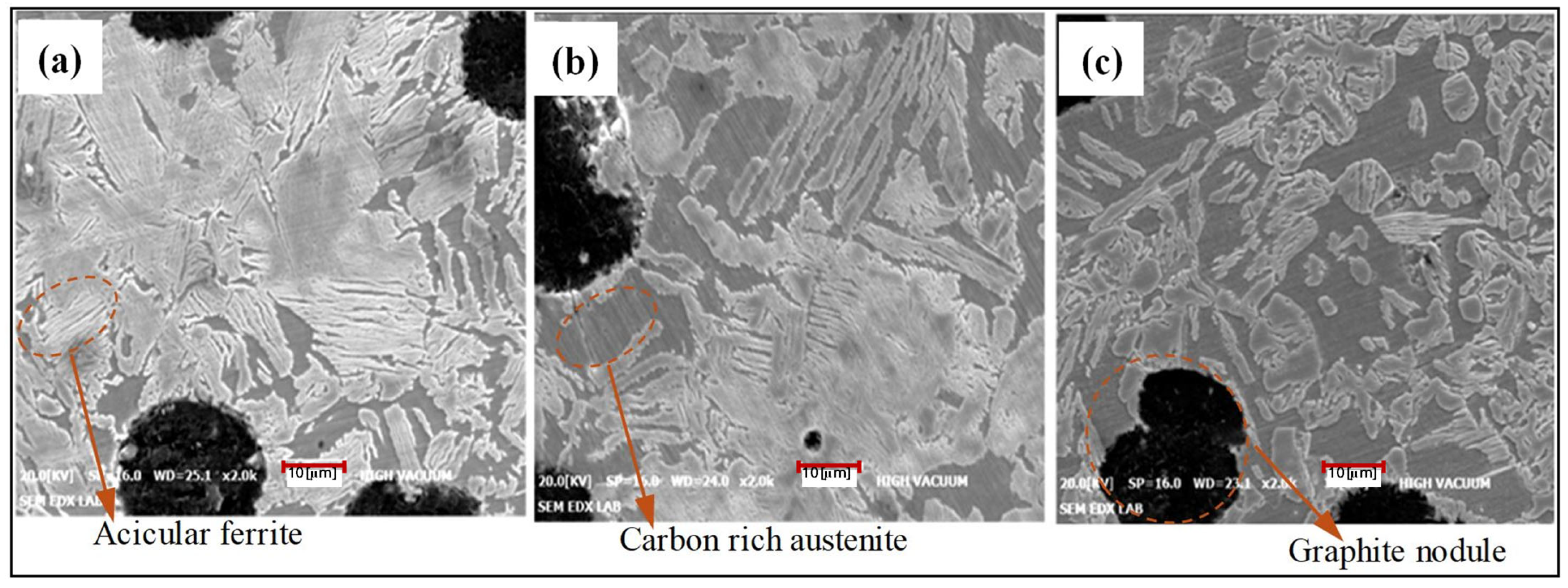

2.2. Microstructure Observation

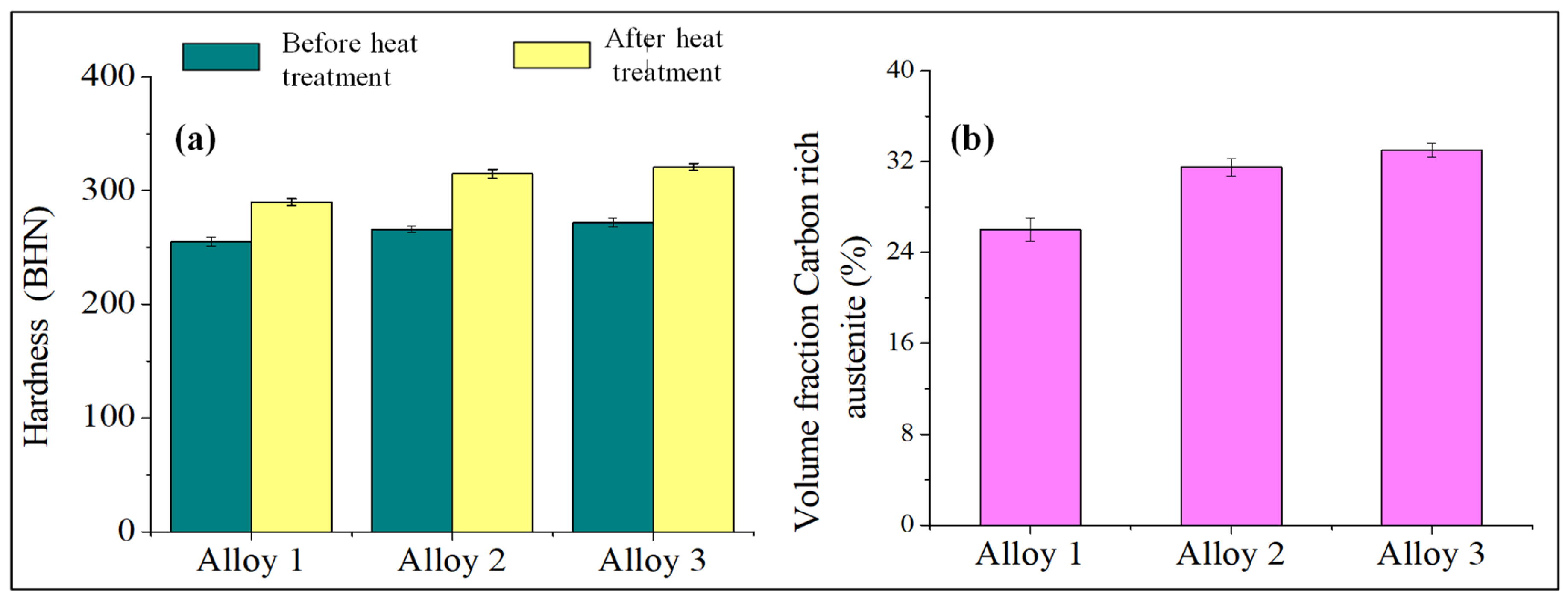

2.3. Heat Treatment and Mechanical Characterization

3. Damping Property Characterization

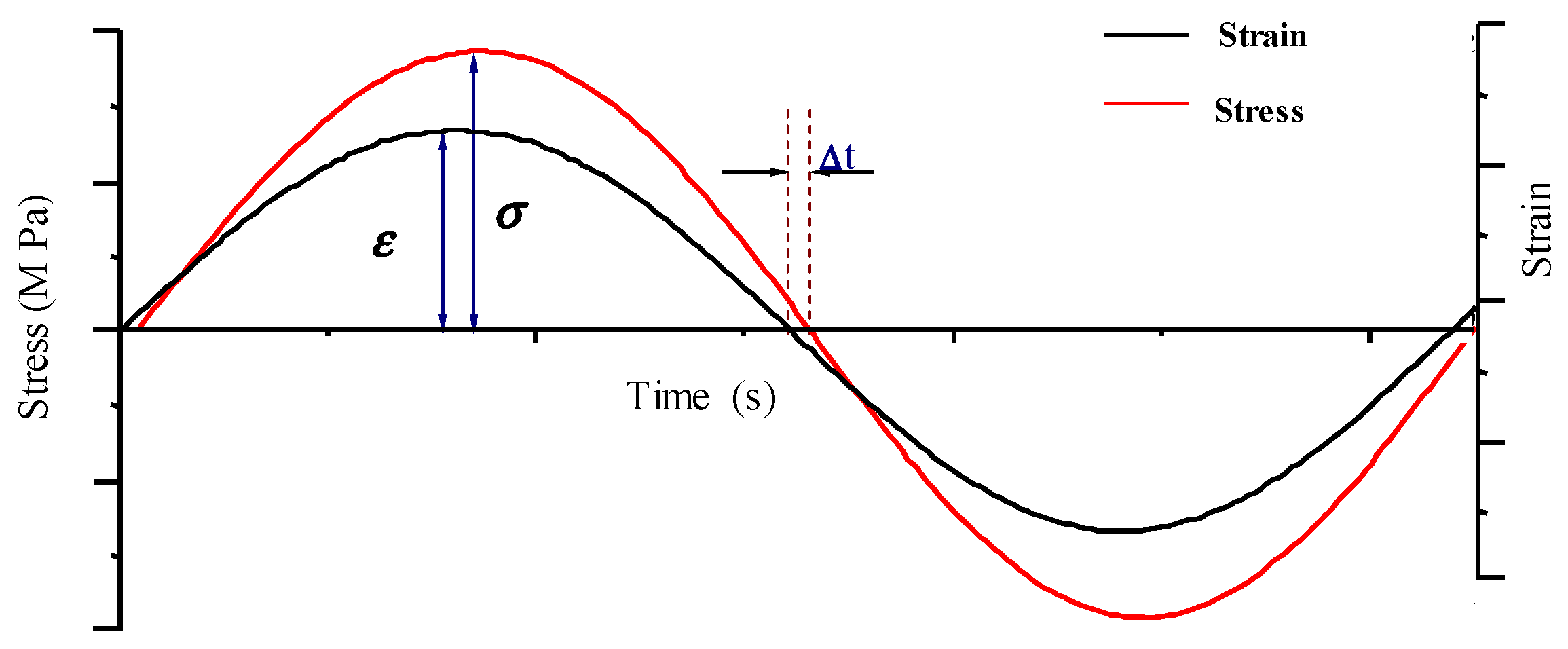

3.1. Material Damping Behavior

3.2. Methodology

3.3. Experimental Setup

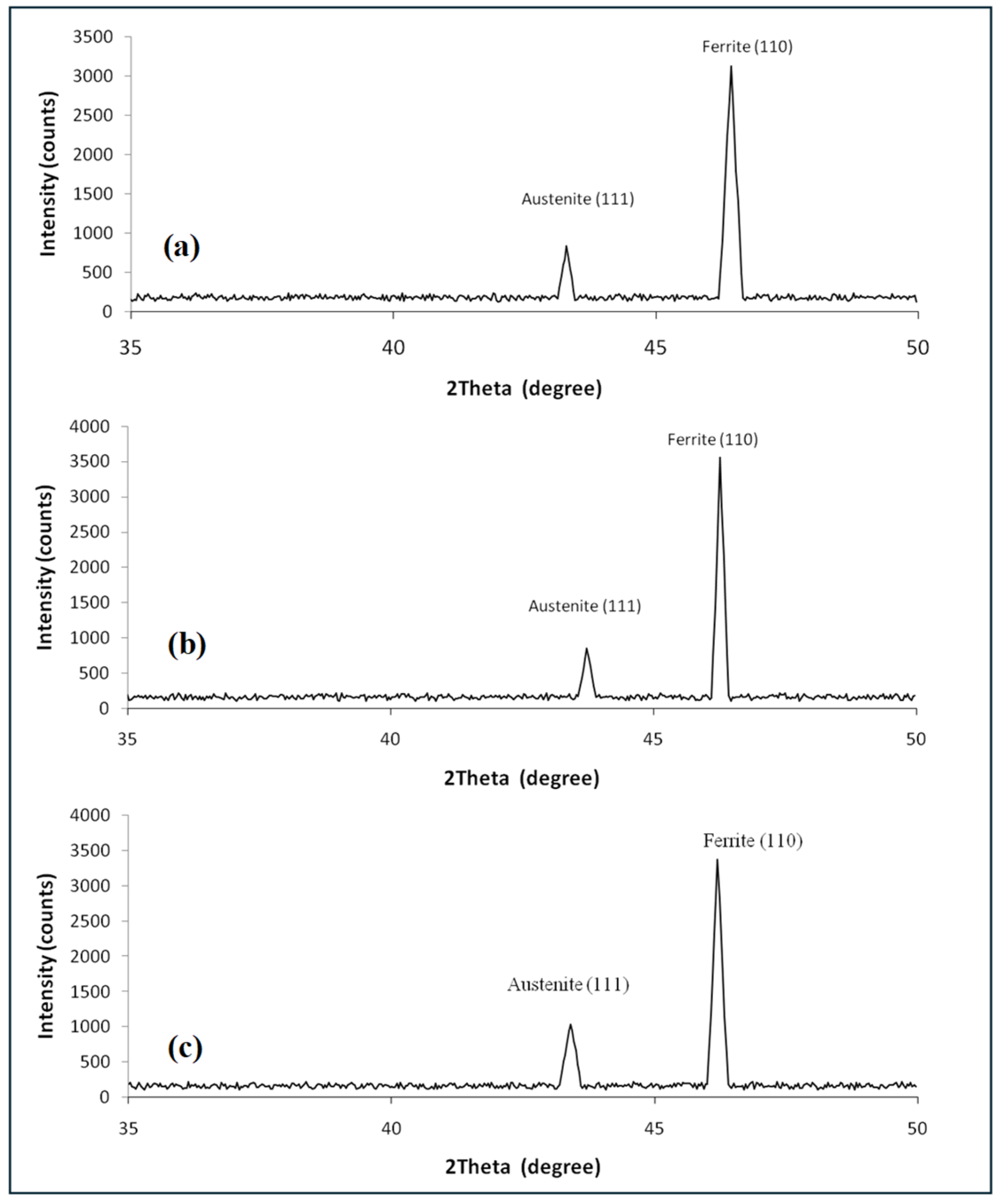

4. XRD Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Material Property Characterization

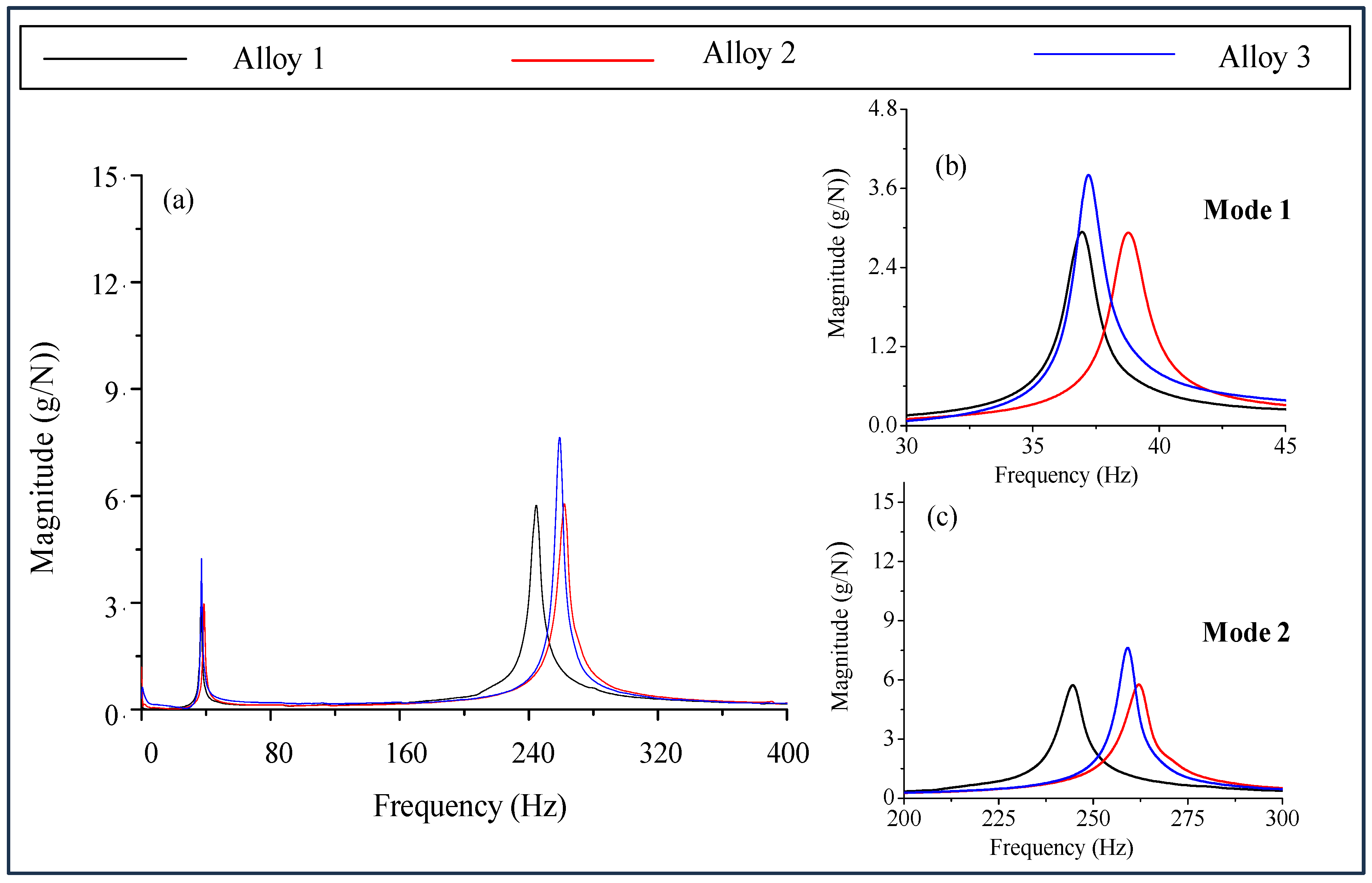

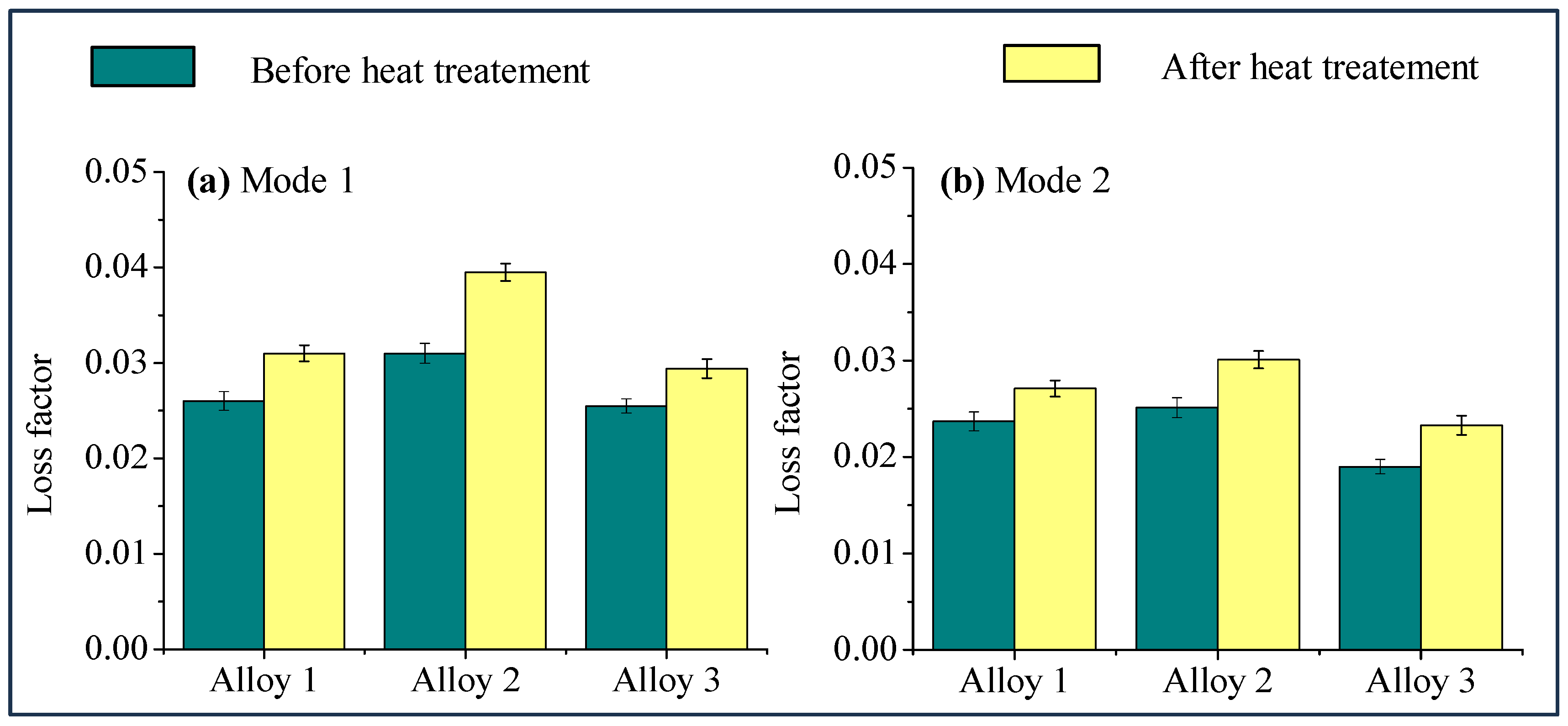

5.2. Damping Characteristics of ADI

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carpenter, S.H.; Stuch, T.E.; Salzbrenner, R. An investigation of the mechanical damping of ductile iron. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1995, 26, 2785–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damir, A.N.; Elkhatib, A.; Nassef, G. Prediction of fatigue life using modal analysis for grey and ductile cast iron. Int. J. Fatigue 2007, 29, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omole, S.O.; Alaneme, K.K.; Oyetunji, A. mechanical damping characteristics of ductile and grey irons micro-alloyed with combinations of Mo, Ni, Cu and Cr. Acta Metall. Slovaca 2021, 27, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, E.; Wang, L.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Song, M. Research and analysis of the effect of heat treatment on damping properties of ductile iron. Open Phys. 2019, 17, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayamathy, M.; Vasanth, R. Noise reduction in two wheeler gears using Austempered ductile iron. SAE Trans. 2003, 112, 2066–2070. [Google Scholar]

- Schaller, R. 8.7 High Damping Materials. In Materials Science Forum; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Baech, Switzerland, 2001; Volume 366, pp. 621–634. [Google Scholar]

- Sckudlarek, W.; Krmasha, M.N.; Al-Rubaie, K.S.; Preti, O.; Milan, J.C.; da Costa, C.E. Effect of austempering temperature on microstructure and mechanical properties of ductile cast iron modified by niobium. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 12, 2414–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Soliman, M.; Youssef, M.; Bähr, R.; Nofal, A. Effect of Niobium on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Alloyed Ductile Irons and Austempered Ductile Irons. Metals 2021, 11, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, N.V.; Mikhalev, R.I.; Tarasova, T.D.; Volkov, S.S. Effect of Aluminum, Copper and Manganese on the Structure and Properties of Cast Irons. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2024, 65, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, A.; Sahin, O.; Akar, N.; Kilicli, V. Effect of austempering temperatures on mechanical properties of dual matrix structure austempered ductile iron. Mater. Test. 2024, 66, 1999–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, P.; Mi, T.; Jiang, B. Influence of Ni addition on strain-induced martensite in austempered ductile iron. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 943, 148786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes González, F.; Magaña Hernández, A.; Miranda Pérez, A.; Almanza Casas, E.; Luna Alvarez, S.; García Vazquez, F. Effect of austenitization time on corrosion and wear resistance in austempered ductile Iron. Int. J. Met. 2024, 19, 1974–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liu, C.; Mei, X.; Yang, X.; Jiang, B. Effects of nickel contents on phase constituent and mechanical properties of ductile iron. Int. J. Met. 2024, 18, 2721–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundlsssach, R.B.; Tartaglia, J.M. Achieving higher strength and ductility in heavy-section ductile iron castings. Int. J. Met. 2024, 18, 1883–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, G.; Qu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, W. Microstructure and low-temperature impact behavior of ADI containing ni. Int. J. Met. 2024, 19, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; You, W.-S. Microstructure and dry/wet tribological behaviors of 1% cu-alloyed austempered ductile iron. Materials 2023, 16, 2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, A.; Sharma, S. Machinability study of manganese alloyed austempered ductile iron. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2018, 40, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.Y.; Sung, J.H.; Kim, G.H.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, I.S. Effect of heat treatment on the damping capacity of austempered ductile cast iron. Mater. Trans. 2009, 50, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumoto, H.; Sawaya, S.; Hinai, M. On the Damping Capacity of Fe–Cr Alloys. Trans. Jpn. Inst. Met. 1979, 20, 409413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewins, D.J. Modal Testing: Theory, Practice and Application; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM A897/A897M; Standard Specification for Austempered Ductile Iron Castings. ASTM International: Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2006.

- Hegde, A.; Sharma, S. Comparison of machinability of manganese alloyed austempered ductile iron produced using conventional and two step austempering processes. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 056519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E10; Standard Test Method for Brinell Hardness of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Roylance, D. Engineering Viscoelasticity; Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, UK, 2001; Volume 2139, pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lakes, R. Viscoelastic Materials; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, M.J.; Tang, B. Virtual Experiments in Mechanical Vibrations; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, W.T.; Dahleh, M.D.; Padmanabhan, C. Theory of Vibrations with Applications; Pearson: London, UK, 2011; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S.S. Mechanical Vibrations; Pearson: London, UK, 2018; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.R.; Farag, N.H.; Pan, J. Evaluation of frequency dependent rubber mount stiffness and damping by impact test. Appl. Acoust. 2006, 66, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, L.E.; Ripin, Z.M. Dynamic stiffness and loss factor measurement of engine rubber mount by impact test. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 1880–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Hegde, A. An Analysis of the Amount of Retained Austenite in Manganese Alloyed Austempered Ductile Iron. Mater. Res. 2021, 24, e20210301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellah, M.Y.; Alharthi, H.; Alfattani, R.; Suker, D.K.; Abu El-Ainin, H.M.; Mohamed, A.F.; Backar, A.H. Mechanical properties and fracture toughness prediction of ductile cast iron under thermomechanical treatment. Metals 2024, 14, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, A.N. Ni-Cu Alloyed Austempered Ductile Iron Resistance to Multifactorial Wear. Lubricants 2024, 12, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobuki, T.; Aoki, T.; Hatate, M. Effects of Manganese and Heat Treatment on Mechanical Properties in Spheroidal Graphite Cast Iron. Int. J. Met. 2024, 19, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cuo, E.; Wang, L.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Liu, X.; Yi, P. Effect of second-step austempering temperature on mechanical damping of austempered ductile iron. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2639, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Casting\Element in wt% | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Mg | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alloy 1 | 3.700 | 2.600 | 0.310 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.017 | 0.0360 | 93.350 |

| Alloy 2 | 3.710 | 2.600 | 0.600 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.017 | 0.0380 | 92.960 |

| Alloy 3 | 3.710 | 2.590 | 0.920 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.0370 | 92.600 |

| Parameter | Alloy 1 | Alloy 2 | Alloy 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nodule Count (no/mm2) | 340 ± 3 | 360 ± 2 | 368 ± 2 |

| Average Nodule Diameter (µm) | 18.4 ± 1.2 | 19.1 ± 1.0 | 19.3 ± 1.1 |

| Roundness Factor | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 0.87 ± 0.02 |

| Nodule Area Fraction (%) | 8.2 ± 0.4 | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 9.1 ± 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Poojary, U.R.; Hegde, A.; Hegde, S. Damping Performance of Manganese Alloyed Austempered Ductile Iron. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010420

Poojary UR, Hegde A, Hegde S. Damping Performance of Manganese Alloyed Austempered Ductile Iron. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):420. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010420

Chicago/Turabian StylePoojary, Umanath R., Ananda Hegde, and Sriharsha Hegde. 2026. "Damping Performance of Manganese Alloyed Austempered Ductile Iron" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010420

APA StylePoojary, U. R., Hegde, A., & Hegde, S. (2026). Damping Performance of Manganese Alloyed Austempered Ductile Iron. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010420