Artificial Intelligence for Artifact Reduction in Cone Beam Computed Tomographic Images: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Selection Process

- Population: in-vivo human CBCT images;

- Intervention: artifact reduction techniques based on AI;

- Comparator: no algorithm or alternative artifact reduction methods (other than AI);

- Outcome: image quality metrics;

- Study design: diagnostic accuracy studies, controlled trials, retrospective/prospective cohorts comparing AI vs. comparator, cross-sectional studies, and technical validation papers.

- Articles in English without restrictions on time of publication;

- Studies using AI to reduce the artifacts of CBCT images;

- Studies using artificial intelligence models including human CBCT scans.

- Studies applying AI to any imaging modality other than CBCT (e.g., CT, 4DCBCT);

- Studies using generative AI models in order to enhance the quality of CBCT images by generating sCTs;

- Reviews and conference abstracts;

- Unavailable full-text;

- Studies employing AI models trained on CBCT images from phantoms, objects, or animal models.

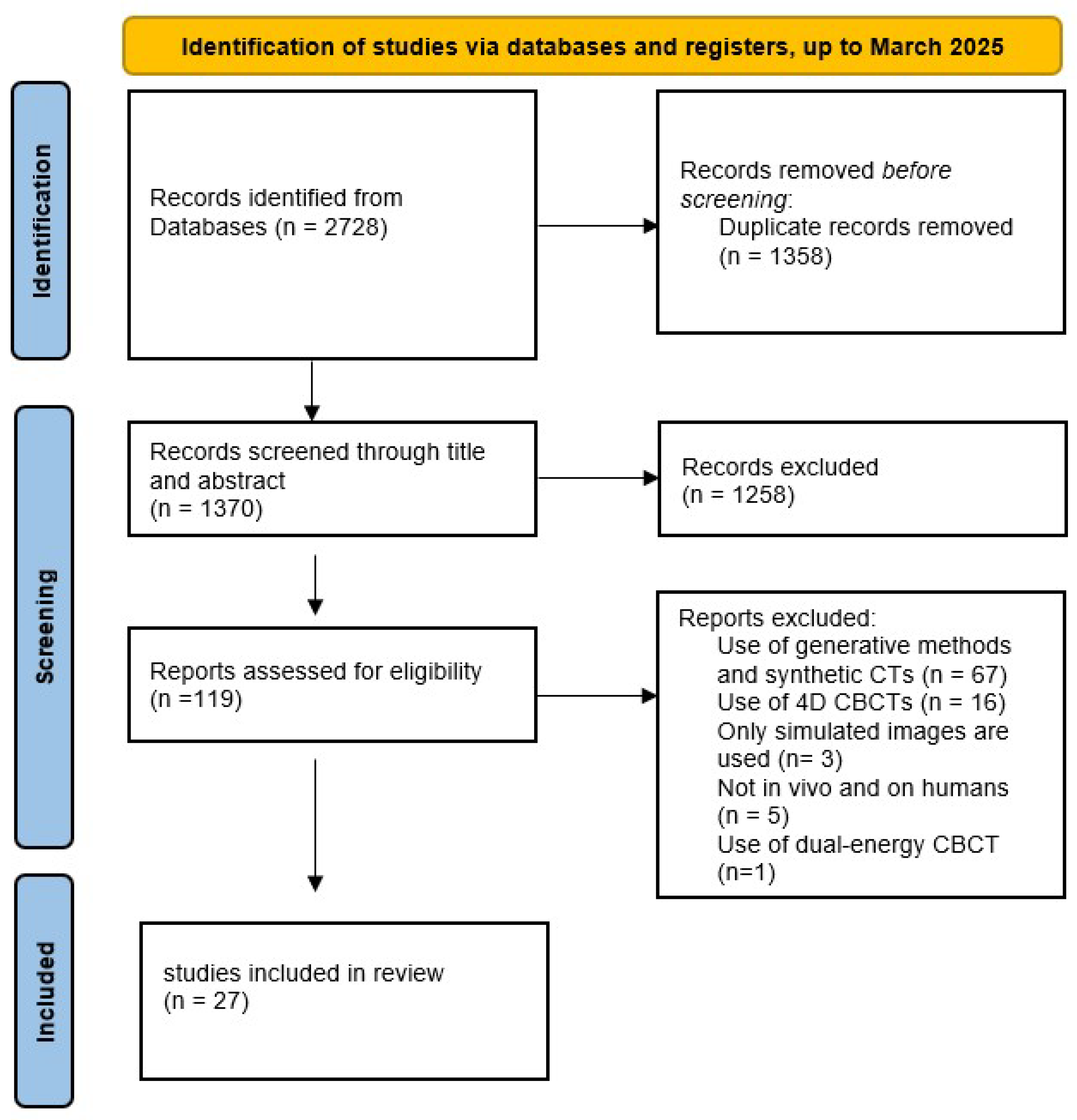

2.3. Screening and Study Selection

2.4. Data Items

- General characteristics:

- Author, Title, Year;

- Aim of the study: brief description of the research question of the study;

- Anatomical region of interest: indication of the anatomical region on which the imaging is focused (e.g., dentition, pelvis, chest, etc.);

- Main results: brief description of the main results of the study in terms of outcomes.

- Dataset characteristics and management:

- Dataset size: brief description in terms of number of patients and images analyzed;

- Dataset publicly available: indication of the dataset availability;

- Simulated data: indication about the use of synthetic or artificially generated data.

- AI modeling characteristics:

- AI model: type of model architecture adopted (e.g., CNN, recurrent neural network, U-Net, etc.);

- AI model code publicly available: indication of the availability of the AI model source code;

- Data augmentation: indication regarding the use of data augmentation techniques;

- Performance metrics: indication of quantitative or qualitative methods and metrics to assess the performance of the proposed AI-based approach.

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Synthesis and Analysis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

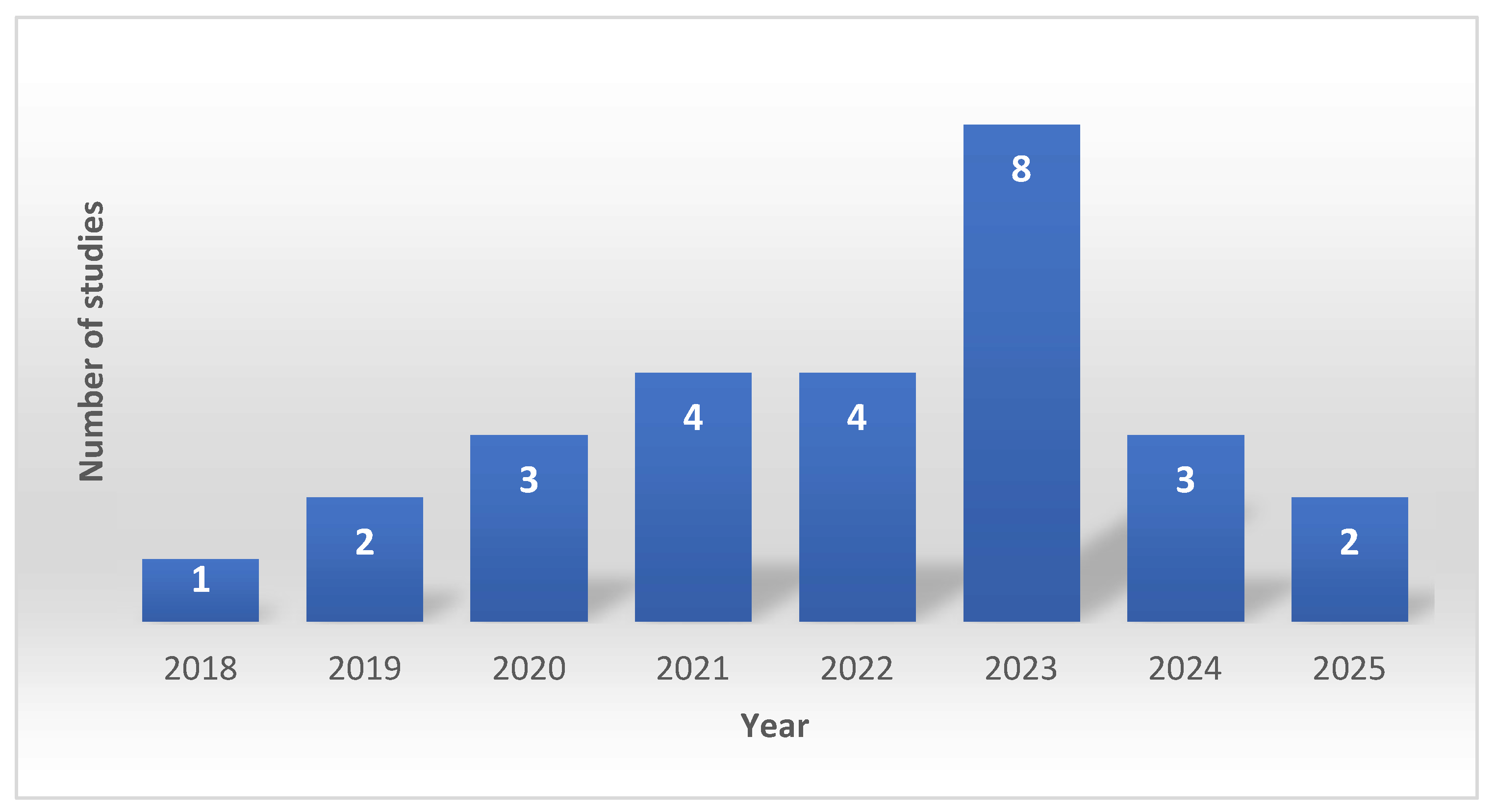

3.3. Temporal Distribution

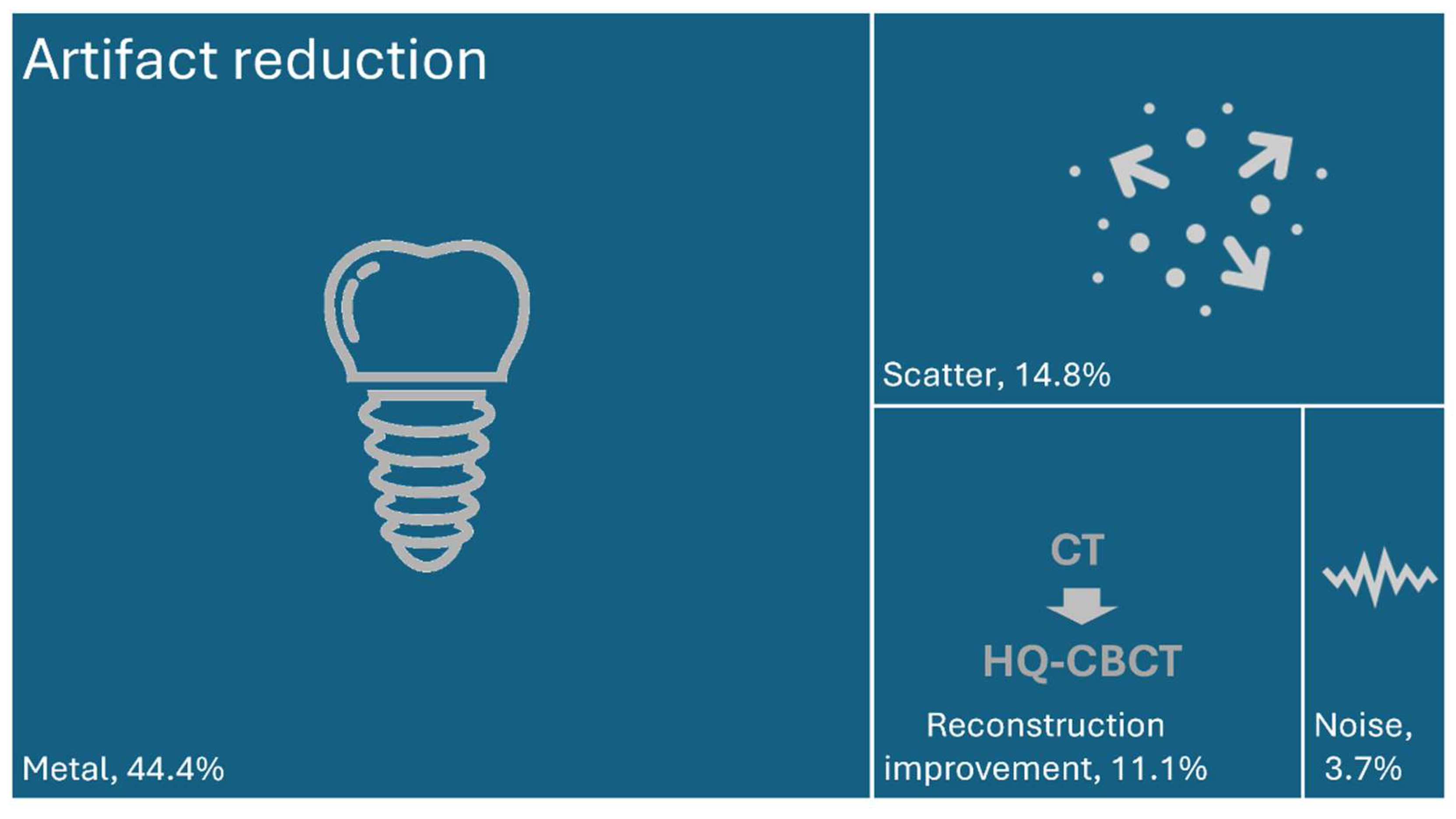

3.4. Main Categories of the Included Studies

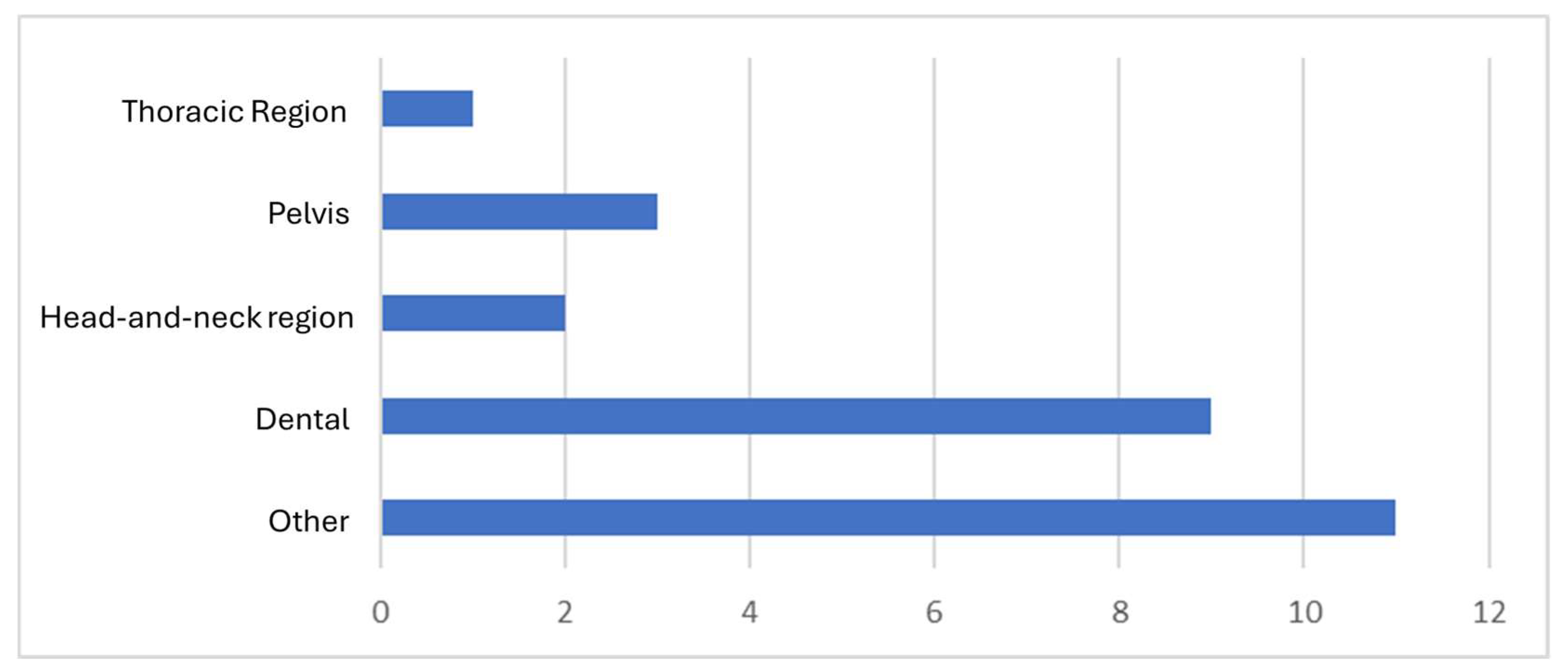

3.5. Anatomic Regions

3.6. AI Modeling Approaches

3.7. Dataset and Availability Issues

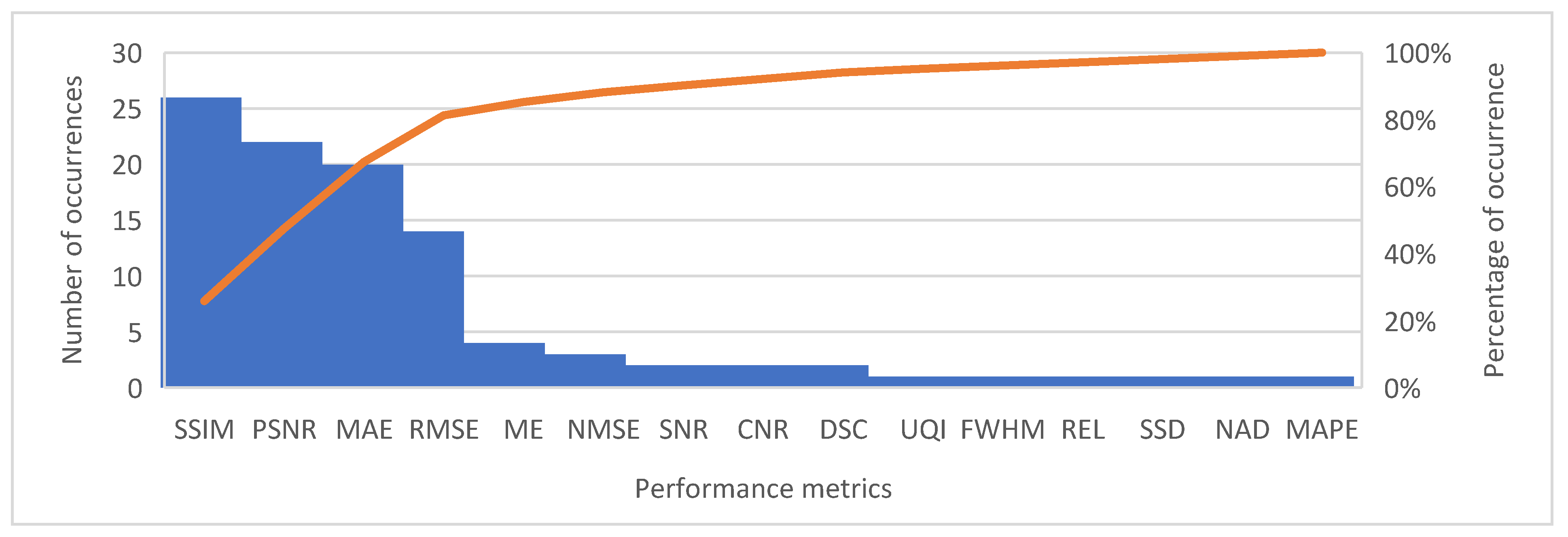

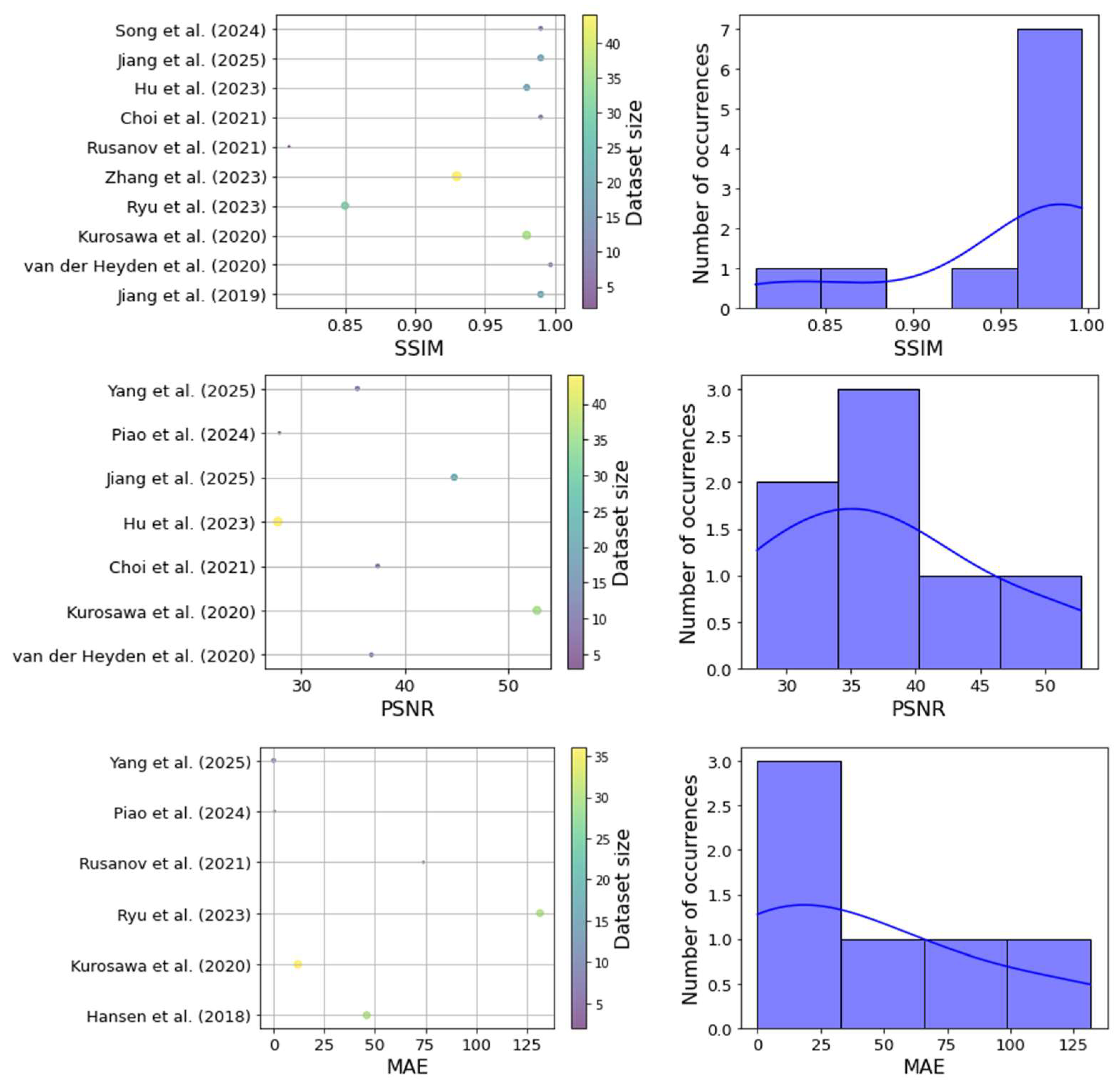

3.8. Performance Metrics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Booshehri, S.G.; Kazemzadeh, F.; Soltani, P.; Motamedi, M.R.K. Level of knowledge of dental practitioners in Isfahan, Iran about cone-beam computed tomography and digital radiography. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2015, 45, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, R.; Heil, U.; Groβ, D.; Bruellmann, D.D.; Dranischnikow, E.; Schwanecke, U.; Schoemer, E. Artefacts in CBCT: A review. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2011, 40, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, P.; Moaddabi, A.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Bateni, M.R.; Naghdi, S.; Cernera, M.; Mirrashidi, F.; Azimipour, M.M.; Spagnuolo, G.; Valletta, A. Effect of a metal artifact reduction algorithm on cone-beam computed tomography scans of titanium and zirconia implants within and outside the field of view. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2024, 54, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajappa, A.K.; Dwivedi, N.; Tiwari, R. Artifacts: The downturn of CBCT image. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shavakhi, M.; Soltani, P.; Aghababaee, G.; Patini, R.; Armogida, N.G.; Spagnuolo, G.; Valletta, A. A Quantitative Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Metal Artifact Reduction Algorithm in Cone Beam Computed Tomographic Images with Stainless Steel Orthodontic Brackets and Arch Wires: An Ex Vivo Study. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merone, G.; Valletta, R.; De Santis, R.; Ambrosio, L.; Martina, R. A novel bracket base design: Biomechanical stability. Eur. J. Orthod. 2010, 32, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterlik, I.; Strzelecki, A.; Lehmann, M.; Messmer, P.; Munro, P.; Paysan, P.; Plamondon, M.; Seghers, D. Reducing residual-motion artifacts in iterative 3D CBCT reconstruction in image-guided radiation therapy. Med. Phys. 2021, 48, 6497–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golosio, B.; Schoonjans, T.; Brunetti, A.; Oliva, P.; Masala, G.L. Monte Carlo simulation of X-ray imaging and spectroscopy experiments using quadric geometry and variance reduction techniques. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014, 185, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Lin, G.; Li, X.; Piao, Z.; Huang, S.; Wu, W.; Qi, M.; Ma, J.; Zhou, L.; Xu, Y. A correlated sampling-based Monte Carlo simulation for fast CBCT iterative scatter correction. Med. Phys. 2023, 50, 1466–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanassov, E.; Dimov, I.T. What Monte Carlo models can do and cannot do efficiently? Appl. Math. Model. 2008, 32, 1477–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian, M.; Montoya-Zegarra, J.A.; Herzig, I.; Eggenberger Hotz, P.; Lichtensteiger, L.; Morf, M.; Züst, A.; Paysan, P.; Peterlik, I.; Scheib, S.; et al. Mitigation of motion-induced artifacts in cone beam computed tomography using deep convolutional neural networks. Med. Phys. 2023, 50, 6228–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R.K.G.; Togashi, K. Convolutional neural networks: An overview and application in radiology. Insights Into Imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xing, Y. CT artifact reduction via U-net CNN. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2018: Image Processing, Houston, TX, USA, 11–13 February 2018; pp. 440–445. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, L.; You, L.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, Z.; Zhao, W.; Zeng, N.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X. Generative Adversarial Networks and Its Applications in Biomedical Informatics. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Zhang, C.; Liang, X.; Deng, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, X.; Song, L.; Zhao, X.; Xie, Y. A Deep Unsupervised Learning Model for Artifact Correction of Pelvis Cone-Beam CT. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 686875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ahn, J.; Kim, B.; Kim, C.; Baek, J. Convolutional neural network–based metal and streak artifacts reduction in dental CT images with sparse-view sampling scheme. Med. Phys. 2022, 49, 6253–6277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, M.A.; Cho, M.H.; Cho, M.H.; Lee, S.Y. U-net based metal segmentation on projection domain for metal artifact reduction in dental CT. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2019, 9, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, C.; Yang, P.; Hu, X.; Luo, C.; Xue, Y.; Xu, L.; Hu, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J. Scatter correction of cone-beam CT using a deep residual convolution neural network (DRCNN). Phys. Med. Biol. 2019, 64, 145003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, H.; Huang, K.; Du, Y.; Teng, M. Streaking artifacts suppression for cone-beam computed tomography with the residual learning in neural network. Neurocomputing 2020, 378, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Tang, F.; Zhong, T.; Zhang, Y. Metal artifact reduction on cervical CT images by deep residual learning. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 2018, 17, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heyden, B.; Roden, S.; Dok, R.; Nuyts, S.; Sterpin, E. Virtual monoenergetic micro-CT imaging in mice with artificial intelligence. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zunair, H.; Ben Hamza, A. Sharp U-Net: Depthwise convolutional network for biomedical image segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 136, 104699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusanov, B.; Hassan, G.M.; Reynolds, M.; Sabet, M.; Kendrick, J.; Rowshanfarzad, P.; Ebert, M. Deep learning methods for enhancing cone-beam CT image quality toward adaptive radiation therapy: A systematic review. Med. Phys. 2022, 49, 6019–6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian, M.; Barco, D.; Herzig, I.; Schilling, F.-P. Artifact reduction in 3D and 4D cone-beam computed tomography images with deep learning: A review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 10281–10295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.; Moon, S.; Baek, J.; Shim, H. Rigid and non-rigid motion artifact reduction in X-ray CT using attention module. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 67, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heyden, B.; Uray, M.; Fonseca, G.P.; Huber, P.; Us, D.; Messner, I.; Law, A.; Parii, A.; Reisz, N.; Rinaldi, I. A Monte Carlo based scatter removal method for non-isocentric cone-beam CT acquisitions using a deep convolutional autoencoder. Phys. Med. Biol. 2020, 65, 145002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, C.M.; Bayaraa, T.; Yun, H.S.; Jang, T.-J.; Park, H.S.; Seo, J.K. Deep learning method for reducing metal artifacts in dental cone-beam CT using supplementary information from intra-oral scan. Phys. Med. Biol. 2022, 67, 175007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, D.C.; Landry, G.; Kamp, F.; Li, M.; Belka, C.; Parodi, K.; Kurz, C. ScatterNet: A convolutional neural network for cone-beam CT intensity correction. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, 4916–4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurosawa, T.; Nishio, T.; Moriya, S.; Tsuneda, M.; Karasawa, K. Feasibility of image quality improvement for high-speed CBCT imaging using deep convolutional neural network for image-guided radiotherapy in prostate cancer. Phys. Medica 2020, 80, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Lee, C.; Han, Y.; Pang, S.; Kim, Y.H.; Choi, C.; Jang, I.; Han, S.-S. Multi-planar 2.5 D U-Net for image quality enhancement of dental cone-beam CT. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, T.M.; Maier, A.; Kordon, F.; Kreher, B.W. DL-based inpainting for metal artifact reduction for cone beam CT using metal path length information. Med. Phys. 2023, 50, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Seo, J.K.; Hyun, C.M.; Lee, S.M.; Jeon, K. A fidelity-embedded learning for metal artifact reduction in dental CBCT. Med. Phys. 2022, 49, 5195–5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, C.; Li, D.; Niu, T.; Yu, G. Image-based scatter correction for cone-beam CT using flip swin transformer U-shape network. Med. Phys. 2023, 50, 5002–5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusanov, B.; Ebert, M.A.; Mukwada, G.; Hassan, G.M.; Sabet, M. A convolutional neural network for estimating cone-beam CT intensity deviations from virtual CT projections. Phys. Med. Biol. 2021, 66, 215007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, D.; Kim, W.; Lee, J.; Han, M.; Baek, J.; Choi, J.-H. Integration of 2D iteration and a 3D CNN-based model for multi-type artifact suppression in C-arm cone-beam CT. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2021, 32, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thies, M.; Zäch, J.-N.; Gao, C.; Taylor, R.; Navab, N.; Maier, A.; Unberath, M. A learning-based method for online adjustment of C-arm Cone-beam CT source trajectories for artifact avoidance. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2020, 15, 1787–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketcha, M.D.; Marrama, M.; Souza, A.; Uneri, A.; Wu, P.; Zhang, X.; Helm, P.A.; Siewerdsen, J.H. Sinogram+ image domain neural network approach for metal artifact reduction in low-dose cone-beam computed tomography. J. Med. Imaging 2021, 8, 052103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, X.; Lu, Y.; Hua, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, S.; Wan, L.; Xie, Q.; Ji, X.; Chen, Y. Scatter correction for cone-beam CT via scatter kernel superposition-inspired convolutional neural network. Phys. Med. Biol. 2023, 68, 075011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, H.; Hietanen, A.; Särkkä, S. Deep learning based projection domain metal segmentation for metal artifact reduction in cone beam computed tomography. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 100371–100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Ritschl, L.; Beister, M.; Biniazan, R.; Wagner, F.; Kreher, B.; Gottschalk, T.M.; Kappler, S.; Maier, A. Simulation-driven training of vision transformers enables metal artifact reduction of highly truncated CBCT scans. Med. Phys. 2024, 51, 3360–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Reddy, K.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Gao, H. SEA-Net: Structure-enhanced attention network for limited-angle CBCT reconstruction of clinical projection data. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 4507613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Lyu, T.; Ma, G.; Wu, Z.; Zhong, X.; Xi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, W. CBCT projection domain metal segmentation for metal artifact reduction using hessian-inspired dual-encoding network with guidance from segment anything model. Med. Phys. 2025, 52, 3900–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, Z.; Deng, W.; Huang, S.; Lin, G.; Qin, P.; Li, X.; Wu, W.; Qi, M.; Zhou, L.; Li, B. Adaptive scatter kernel deconvolution modeling for cone-beam CT scatter correction via deep reinforcement learning. Med. Phys. 2024, 51, 1163–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Yao, T.; Peng, S.; Zhu, M.; Meng, M.; Ma, J.; Zeng, D.; Huang, J.; Bian, Z.; Wang, Y. b-MAR: Bidirectional artifact representations learning framework for metal artifact reduction in dental CBCT. Phys. Med. Biol. 2024, 69, 145010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Lin, Y.B.; Jiang, S.D.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Bao, X.D. A new dental CBCT metal artifact reduction method based on a dual-domain processing framework. Phys. Med. Biol. 2023, 68, 175016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajer, R.; Wajer, A.; Kazimierczak, N.; Wilamowska, J.; Serafin, Z. The Impact of AI on Metal Artifacts in CBCT Oral Cavity Imaging. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Bai, X.; Cao, G. A dual-domain network with division residual connection and feature fusion for CBCT scatter correction. Phys. Med. Biol. 2025, 70, 045014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Jeong, U.; Lee, D.; Kim, H.; Cho, S. Image quality improvement in bowtie-filter-equipped cone-beam CT using a dual-domain neural network. Med. Phys. 2023, 50, 7498–7512. [Google Scholar]

- Angelone, F.; Ponsiglione, A.M.; Grassi, R.; Amato, F.; Sansone, M. A general framework for the assessment of scatter correction techniques in digital mammography. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 89, 105802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, M.; Ponsiglione, A.M.; Angelone, F.; Amato, F.; Grassi, R. Effect of X-ray scatter correction on the estimation of attenuation coefficient in mammography: A simulation study. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for Extended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE), Rome, Italy, 26–28 October 2022; pp. 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Angelone, F.; Franco, A.; Ponsiglione, A.M.; Ricciardi, C.; Belfiore, M.P.; Gatta, G.; Grassi, R.; Sansone, M.; Amato, F. Assessment of an unsupervised denoising ap-proach based on Noise2Void in digital mammography. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, P.; Devlin, H.; Etemadi Sh, M.; Rengo, C.; Spagnuolo, G.; Baghaei, K. Do metal artifact reduction algorithms influence the detection of implant-related injuries to the inferior alveolar canal in CBCT images? BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Krupinski, E.A.; Xie, H.; Stillman, A.E. On the data acquisition, image reconstruction, cone beam artifacts, and their suppression in axial MDCT and CBCT–A review. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, e761–e782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, E.; Mallya, S. White and Pharoah’s Oral Radiology-E-BOOK: White and Pharoah’s Oral Radiology-E-BOOK; Elsevier Health Sciences: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, T.; Kang, Y.; Qiang, J.; Hu, D.; Zhang, Y. SureUnet: Sparse autorepresentation encoder U-Net for noise artifact suppression in low-dose CT. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 7561–7573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Han, J.; Shan, H.; Liu, J. Semi-supervised spatial-frequency transformer for metal artifact reduction in maxillofacial CT and evaluation with intraoral scan. Eur. J. Radiol. 2025, 187, 112087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhang, D.; Yu, C.; Jia, L.; Zhu, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, D.; Yu, H. MAReraser: Metal Artifact Reduction with Image Prior Using CNN and Transformer Together. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Lisbon, Portugal, 3–6 December 2024; pp. 4060–4065. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Zhong, X.; Lyu, T.; Xi, Y.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, S.; Yu, H.; Chen, Y. PRAISE-Net: Deep Projection-domain Data-consistent Learning Network for CBCT Metal Artifact Reduction. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 4506113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Bendig, D.; Vollmar, H.C.; Rasche, P. Mapping the bibliometrics landscape of AI in medicine: Methodological study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e45815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, B.; Baessler, B.; Cuocolo, R.; Mercaldo, N.; Pinto dos Santos, D. Trends and statistics of artificial intelligence and radiomics research in radiology, nuclear medicine, and medical imaging: Bibliometric analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 7542–7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, K.; Santomartino, S.M.; Sulam, J.; Yi, P.H. Code and data sharing practices in the radiology artificial intelligence literature: A meta-research study. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2022, 4, e220081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Gabriel, K.; Dheer, S.; Parajuli, A.; Augustin, A.I.; Elahi, A.; Awan, O.; Dako, F. Understanding biases and disparities in radiology AI datasets: A review. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2023, 20, 836–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudeng, V.; Kim, M.; Choe, S.-W. Prospects of structural similarity index for medical image analysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balki, I.; Amirabadi, A.; Levman, J.; Martel, A.L.; Emersic, Z.; Meden, B.; Garcia-Pedrero, A.; Ramirez, S.C.; Kong, D.; Moody, A.R. Sample-size determination methodologies for machine learning in medical imaging research: A systematic review. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2019, 70, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Emanuel, E.J. Predicting the future—Big data, machine learning, and clinical medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1216–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, A.; Tam, R.; Cadrin-Chênevert, A.; Guest, W.; Chong, J.; Barfett, J.; Chepelev, L.; Cairns, R.; Mitchell, J.R.; Cicero, M.D. Canadian Association of Radiologists white paper on artificial intelligence in radiology. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2018, 69, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, M.; Cioffi, I.; D’antò, V.; Valletta, A.; Valletta, R.; Amato, M. Facial attractiveness of skeletal class I and class II malocclusion as perceived by laypeople, patients and clinicians. Minerva Stomatol. 2018, 67, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | ((Cone AND Beam AND (Computed OR computerized) AND Tomography) OR (Cone AND Beam AND CT) OR (CBCT) OR (dental CT)) AND ((artificial AND intelligence) OR (deep AND learning) OR (machine AND learning) OR (neural AND network) OR (U-net)) AND ((quality AND (enhance* OR improve* OR correct*)) OR artifact* OR artefact* OR scatter*) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(((artificial AND intelligence) OR (deep AND learning) OR (machine AND learning) OR (neural AND network) OR (U-net)) AND ((Cone AND Beam AND (Computed OR computerized) AND Tomography) OR (Cone AND Beam AND CT) OR (CBCT) OR (dental CT)) AND ((quality AND (enhance* OR improve* OR correct*)) OR artifact* OR artefact* OR scatter*)) |

| Web of Science | TS = (((artificial AND intelligence) OR (deep AND learning) OR (machine AND learning) OR (neural AND network) OR (U-net)) AND ((Cone AND Beam AND (Computed OR computerized) AND Tomography) OR (Cone AND Beam AND CT) OR (CBCT) OR (dental CT)) AND ((quality AND (enhance* OR improve* OR correct*)) OR artifact* OR artefact* OR scatter*)) |

| Embase | (artificial:ti,ab,kw AND intelligence:ti,ab,kw OR (deep:ti,ab,kw AND learning:ti,ab,kw) OR (machine:ti,ab,kw AND learning:ti,ab,kw) OR (neural:ti,ab,kw AND network:ti,ab,kw) OR ‘u net’:ti,ab,kw) AND (cone:ti,ab,kw AND beam:ti,ab,kw AND (computed:ti,ab,kw OR computerized:ti,ab,kw) AND tomography:ti,ab,kw OR (cone:ti,ab,kw AND beam:ti,ab,kw AND ct:ti,ab,kw) OR cbct:ti,ab,kw OR ‘dental ct’:ti,ab,kw) AND (quality:ti,ab,kw AND (enhance*:ti,ab,kw OR improve*:ti,ab,kw OR correct*:ti,ab,kw) OR artifact*:ti,ab,kw OR artefact*:ti,ab,kw OR scatter*:ti,ab,kw) |

| Google scholar | ((artificial AND intelligence) OR (deep AND learning) OR (machine AND learning) OR (neural AND network) OR (U-net)) AND ((Cone AND Beam AND (Computed OR computerized) AND Tomography) OR (Cone AND Beam AND CT) OR (CBCT) OR (dental CT)) AND ((quality AND (enhance* OR improve* OR correct*)) OR artifact* OR artefact* OR scatter*) |

| No. | Authors | Year | Aim | Main Task | Anatomic Region | AI Model | AI Model Availability | Dataset Availability | Dataset Size | Dataset Splitting | Simulated Data | Data Augmentation | Qualitative Metrics | Quantitative Metrics | Main Quantitative Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ko et al. [25] | 2021 | Reducing motion artifacts | Motion artifact reduction | Dentition | AttBlocks | yes | yes | 12,560 scans | FBCT teeth dataset: Training: 9660+N2:N18 Testing: 2900 CQ500 dataset: Training: 9600 Testing: 834 CBCT teeth dataset: Training: 9660 Testing: 2900 Chest dataset: Training: 5000 Testing: 2000 | yes | yes | Visual evaluation | PSNR, SSIM | PSNR [dB]: 38.21 SSIM: 0.93 |

| 2 | Jiang et al. [18] | 2019 | Performing scatter correction | Scatter correction | Pelvis | DRCNN | no | no | 20 patients | Training: 15 patients Testing: 2 patients Validation: 3 patients | no | no | Visual evaluation | RMSE, SSIM | RMSE [HU]: 18.80 SSIM: 0.99 |

| 3 | van der Heyden et al. [26] | 2020 | Performing scatter correction | Scatter correction | Head-and-neck | DCAE | no | yes | 8 patients | Training: 1287 simulated projection pairs (primary and scatter) Testing: 360 simulated projections + 8 real patients | yes | yes | Visual evaluation | CNR, MAE, RMSE, PSNR, SSIM | CNR: 2.50–5.00 MAE [cm−1]: 5.80 × 10−3 MSE [cm−2]: 0.10 × 10−3 PSNR [dB]: 36.80 SSIM: 0.997 |

| 4 | Hyun et al. [27] | 2022 | Reducing metal artifacts | Metal artifact reduction | Dentition | Image-enhancing network fIE | no | no | 29 scans | Training: 20 patients Testing: 9 patients | yes | no | Visual evaluation | NMSE, PSNR, SSIM | NMSE [HU]: 0.34 SSIM: 0.99 PSNR [dB]: 57.44 |

| 5 | Hansen et al. [28] | 2018 | Performing scatter correction | Scatter correction | Pelvis, Prostate | ScatterNet | yes | no | 30 patients | Training: 15 patients Testing: 7 patients Validation: 8 patients | no | yes | Visual evaluation | MAE, ME | MAE [HU]: 46.00 ME [HU]: −3.00 |

| 6 | Kurosawa et al. [29] | 2020 | Generating high-quality CBCT images by paired low-quality/high-quality CBCT images | Reconstruction improvement | Pelvis | U-Net | no | no | 36 patients | Training: 30 patients Testing: 6 patients | yes | yes | Visual evaluation | MAE, SSIM, PSNR | MAE [HU]: 12.00 (ROI bone),13.90 (ROI prostate) PSNR [dB]: 52.8 SSIM: 0.98 |

| 7 | Ryu et al. [30] | 2023 | Correcting CBCT images by paired CT images | Reconstruction improvement | Dentition | COMPUNet | no | no | 30 patients | yes | yes | Visual evaluation Expert rating | NRMSE, SSIM, MAE | NRMSE: 0.14 SSIM: 0.85 MAE [HU]: 131.60 | |

| 8 | Gottschalk et al. [31] | 2023 | Reducing metal artifacts by inpainting of metal regions | Metal artifact reduction | Knees, Spines | PaintNet | no | no | 55 scans | Training: 33 scans Validation: 11 scans Testing: 11 scans | no | yes | Visual evaluation | SSIM, PSNR | SSIM: 0.99 PSNR [dB]: +6.00 |

| 9 | Kim et al. [16] | 2022 | Reducing metal artifacts and streaking artifacts | Metal artifact reduction | Dentition | U-Net | no | yes | 27 XCAT phantoms and 1252 real slices | yes | no | Visual evaluation | NRMSE, SSIM | SSIM: 0.99 NRMSE: 0.03 | |

| 10 | Park et al. [32] | 2022 | Reducing metal artifacts by iterative correction | Metal artifact reduction | Dentition | Deep convolutional framelets | no | no | 10 patients | Training: 49 paired data Validation: 7 paired data Testing: 14 paired data | yes | yes | Visual evaluation | RMSE, STD | RMSE [HU]: 0.39 SD [HU]: 14.97 |

| 11 | Zhang et al. [33] | 2023 | Performing scatter correction | Scatter correction | Pelvis | FSTUNet | no | yes | 44 patients | MC simulation dataset: Training: 18 patients Testing: 4 patients Validation: 4 patients Frequency split dataset: Training: 34 patients Testing: 5 patients Validation: 5 patients | yes | no | Visual evaluation | RMSE, SSIM, UQI | RMSE [HU]: 7.62 UQI: 0.99 SSIM: 0.93 |

| 12 | Rusanov et al. [34] | 2021 | Performing scatter correction by intensity correction | Scatter correction | Head-and-neck | U-Net based | no | no | 4 anthropomorphic phantoms and 2 patients | Training: 2001 projections Testing: 1000 projections | yes | yes | Visual evaluation | MAE, SSIM, CNR | MAE [HU]: 74.00 SSIM: 0.81 CNR: 13.90 |

| 13 | Choi et al. [35] | 2021 | Reducing complex low-dose noise | Noise reduction | Thorax, Knees | REDCNN | no | no | 2 phantoms and 8 patients | Training set: 5 patients, Test set: 3 patients | yes | no | Visual evaluation | SSIM, PSNR | PSNR [dB]: 37.41 SSIM: 0.99 tSNR: 12.10 |

| 14 | Thies et al. [36] | 2020 | Reducing metal artifacts by trajectory optimization | Metal artifact reduction | Chest | ConvNet | no | yes | 2739 simulated images | 1: Training: 1368 Testing: 1 chest CT scan 2: Training: 1368 images Testing: 3 simulations | yes | yes | Visual evaluation | FWHM, Fourier Spectrum Intensity, SSIM | SSIM: 0.90 (no noise), 0.89 (with 4.10 × 105 noise), 0.85 (with 5.10 × 104 noise) FWHM: 6.38 Fourier spectrum intensity: 9.05 |

| 15 | Hegazy et al. [17] | 2019 | Reducing metal artifacts by metal segmentation | Metal artifact reduction | Dentition | U-NET | no | no | 5 patients | no | yes | Visual evaluation | REL, SSD, NAD | REL (%): 5.70 SSD (%): 6.80 NAD (%): 8.20 | |

| 16 | Ketcha et al. [37] | 2021 | Reducing metal artifacts and correcting downsampling | Metal artifact reduction | Thorax, Lumbar area | CNNMAR-2 | no | no | 25 scans | Training: 19 scans Testing: 6 scans | yes | yes | Visual evaluation | RMSE | RMSE [mm−1]: 3.40 × 10−3 |

| 17 | Zhuo et al. [38] | 2023 | Performing scatter correction | Scatter correction | Head, Thorax, Abdomen | Dual-encoder U-Net-like network | no | no | 600 projections | yes | yes | Visual evaluation | MAPE, SSIM, RMSE | MAPE (%): 4.73 RMSE [HU]: 4.28 SSIM: 0.93 | |

| 18 | Agrawal et al. [39] | 2023 | Reducing metal artifacts by metal segmentation | Metal artifact reduction | Multiple extremity anatomies (e.g., knee, wrist, foot, ankle, palm, forearm) | Modified U-Net | no | no | 26 scans | Training: 10 metal-affected scans Testing: 10 metal-affected (100 projection pairs) + 6 metal-free scans (2400 projections) | yes | yes | Visual evaluation | DSC, IOU, FPR | DSC: 94.8 IOU: 90.2 FPR ~0.51 × 10−3 |

| 19 | Fan et al. [40] | 2024 | Reducing metal artifacts by metal segmentation | Metal artifact reduction | Knee and lower limb extremities | SwinConvUNet | yes | no | 8200 projections | Training: 6600 projections Validation: 600 projections Testing: 600 projections + 10 cadaver scans (400 projections per scan) + 1 clinical scan (434 projections) | yes | yes | Visual evaluation | PSNR, SSIM | PNSR: 40.598 SSIM: 0.987 |

| 20 | Hu et al. [41] | 2023 | Reconstructing high-quality limited-angle images | Reconstruction improvement | Head-and-neck, Pelvis, Thorax | SEA-Net | yes | no | 90 patients | Training: 102,500 images Validation: 5000 images Testing: 5000 images | no | yes | Visual evaluation | RMSE, PSNR, SSIM | RMSE: 2.38 × 10−4 PSNR [dB]: 33.61 SSIM: 0.9131 |

| 21 | Jiang et al. [42] | 2025 | Reducing metal artifacts by metal segmentation | Metal artifact reduction | Spine | HIDE-Net | no | no | 21 patients | Training: 1644 images Validation: 387 images | yes | no | Visual evaluation | RMSE, PSNR, SSIM | RMSE: 24.22 PSNR: 44.800 SSIM: 0.9986 |

| 22 | Piao et al. [43] | 2024 | Performing scatter correction | Scatter correction | Head and neck, pelvis | Scatter Kernel Deconvolution + Deep Q-Learning | no | no | 3 patients | Training: 40 projections Testing: 1336 projections | yes | no | Visual evaluation | MAPE, MAE, PSNR | MAPE [%]: 6.22 MAE: 0.42 PSNR [dB]: 27.92 |

| 23 | Song et al. [44] | 2024 | Reducing metal artifacts by jointly modeling artifact generation and elimination | Metal artifact reduction | Dentition | b-MAR framework: the artifact encoder (E), the metal artifact generator (G(AFtoA)), and the metal artifact eliminator (G(AtoAF)) | no | no | 10,903 images | Training: 8802 images Testing: 2001 images | yes | no | Visual evaluation Expert rating | RMSE, PSNR, SSIM | RMSE [HU]: 2.3373 PSNR [dB]: 42.5753 SSIM: 0.9931 |

| 24 | Tang et al. [45] | 2023 | Reducing metal artifacts by a dual-domain (image and projection domain) approach | Metal artifact reduction | Dentition | Prior based sinogram linearization correction + 2 U-Net-based CNNs | no | no | 60 projection series | Training: 42 series Validation: 6 series Testing: 13 series | yes | no | Visual evaluation | NRMSD, SSIM | NRMSD (%): 4.0196 SSIM: 0.9924 |

| 25 | Wajer et al. [46] | 2024 | Reducing metal artifacts and improving image quality by noise reduction | Metal artifact reduction and Noise reduction | Dentition | ClariCT.AI | no | no | 61 patients | not applicable | no | not applicable | Visual evaluation Expert rating | Voxel value difference, artifact index, CNR | Voxel value difference: 174.07 Artifact index: 158.31 CNR: 0.93 |

| 26 | Yang et al. [47] | 2025 | Performing scatter correction | Scatter correction | - | DR-Net + FF-Net | no | no | 10 patients (+2 phantom scans) | Training: 7 patients (5040 projections) Validation: 1 patient (720 projections) Testing: 2 patients (1440 projections) + 2 phantom scans | yes | no | Visual evaluation | MAE, PSNR | MAE: 3.195 × 10−4 PSNR [dB]: 35.441 |

| 27 | Yun et al. [48] | 2023 | Improving the image quality of bowtie-filter-equipped CBCT scans by reducing specific artifacts through a dual-domain approach | Reconstruction improvement | - | Modified residual U-Net + attention U-Net | no | yes | 6 patients (+11 phantoms) | Training: 3820 Validation: 1154 Testing: 240 | yes | no | Visual evaluation | RMSE, SSIM, CNR | RMSE: 4.57 × 10−2 SSIM: 0.71 CNR: 18.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Soltani, P.; Spagnuolo, G.; Angelone, F.; Rezaeiyazdi, A.; Mohammadzadeh, M.; Maisto, G.; Moaddabi, A.; Cernera, M.; Armogida, N.G.; Amato, F.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for Artifact Reduction in Cone Beam Computed Tomographic Images: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010396

Soltani P, Spagnuolo G, Angelone F, Rezaeiyazdi A, Mohammadzadeh M, Maisto G, Moaddabi A, Cernera M, Armogida NG, Amato F, et al. Artificial Intelligence for Artifact Reduction in Cone Beam Computed Tomographic Images: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):396. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010396

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoltani, Parisa, Gianrico Spagnuolo, Francesca Angelone, Asal Rezaeiyazdi, Mehdi Mohammadzadeh, Giuseppe Maisto, Amirhossein Moaddabi, Mariangela Cernera, Niccolò Giuseppe Armogida, Francesco Amato, and et al. 2026. "Artificial Intelligence for Artifact Reduction in Cone Beam Computed Tomographic Images: A Systematic Review" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010396

APA StyleSoltani, P., Spagnuolo, G., Angelone, F., Rezaeiyazdi, A., Mohammadzadeh, M., Maisto, G., Moaddabi, A., Cernera, M., Armogida, N. G., Amato, F., & Ponsiglione, A. M. (2026). Artificial Intelligence for Artifact Reduction in Cone Beam Computed Tomographic Images: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010396