Evaluation of Digital Elevation Models (DEM) Generated from the InSAR Technique in a Sector of the Central Andes of Chile, Using Sentinel 1 and TerraSar-X Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

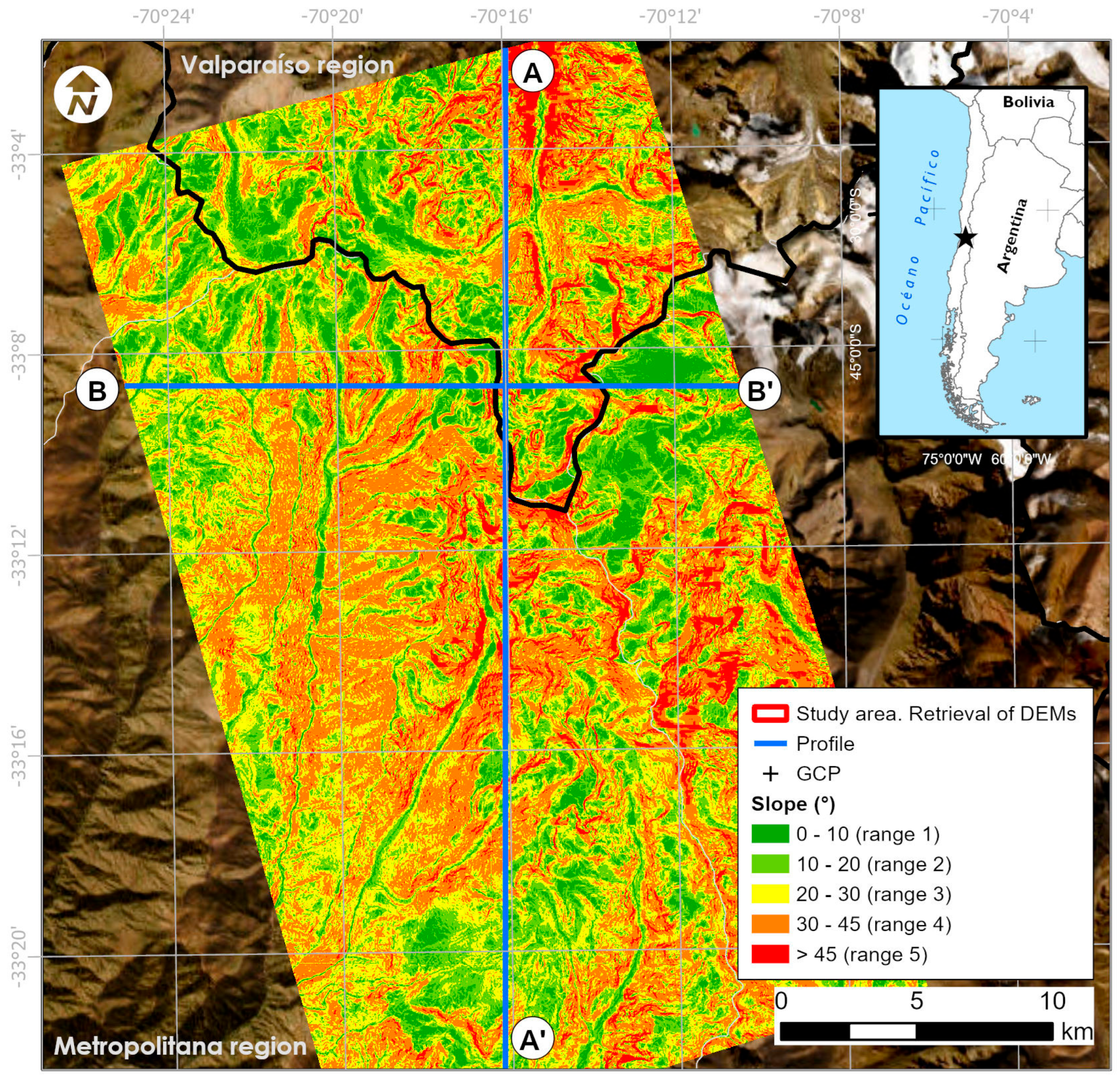

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Acquisition

2.2.1. S1 and TSX Data

2.2.2. Reference DEMs

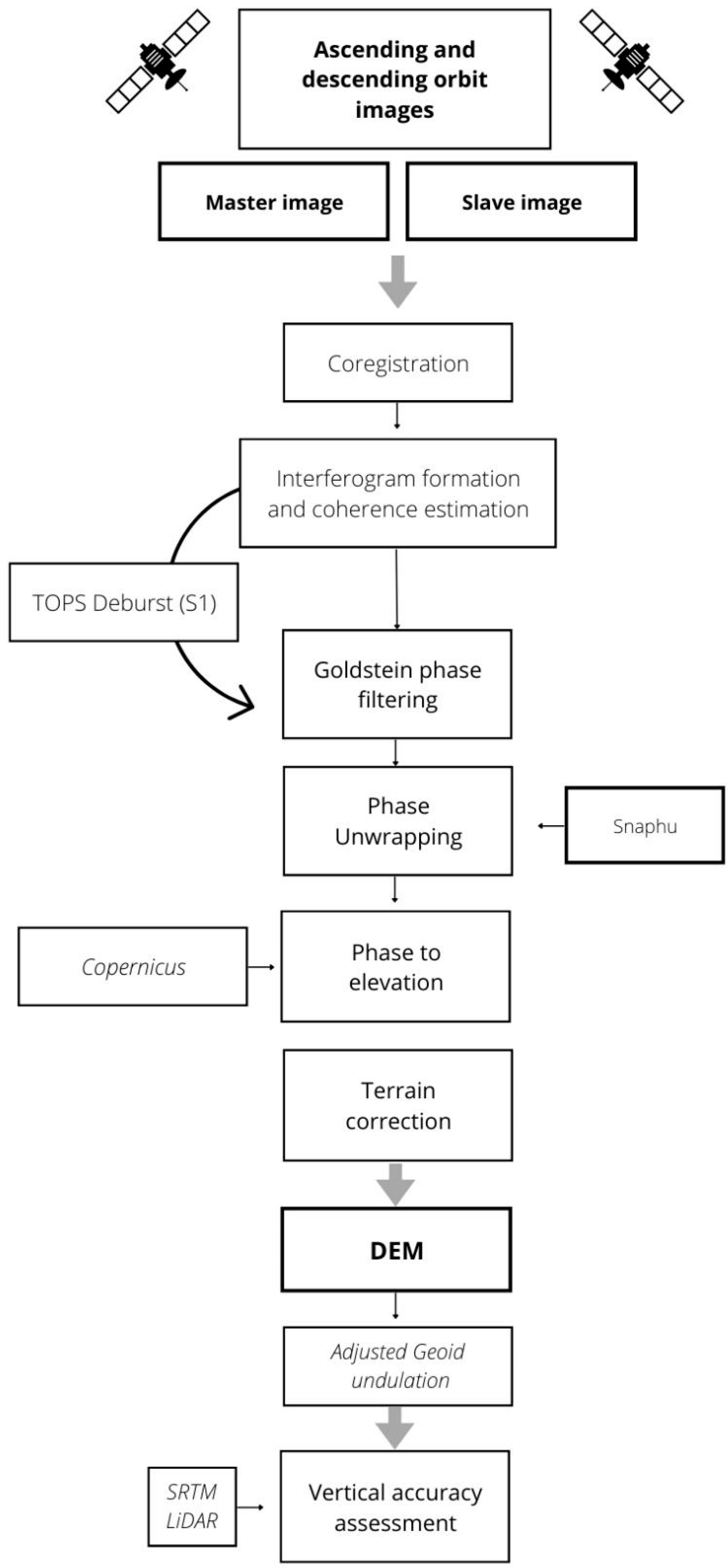

2.3. Interferometric Processing of S1 and TSX

2.4. Vertical Accuracy Assessment

3. Results

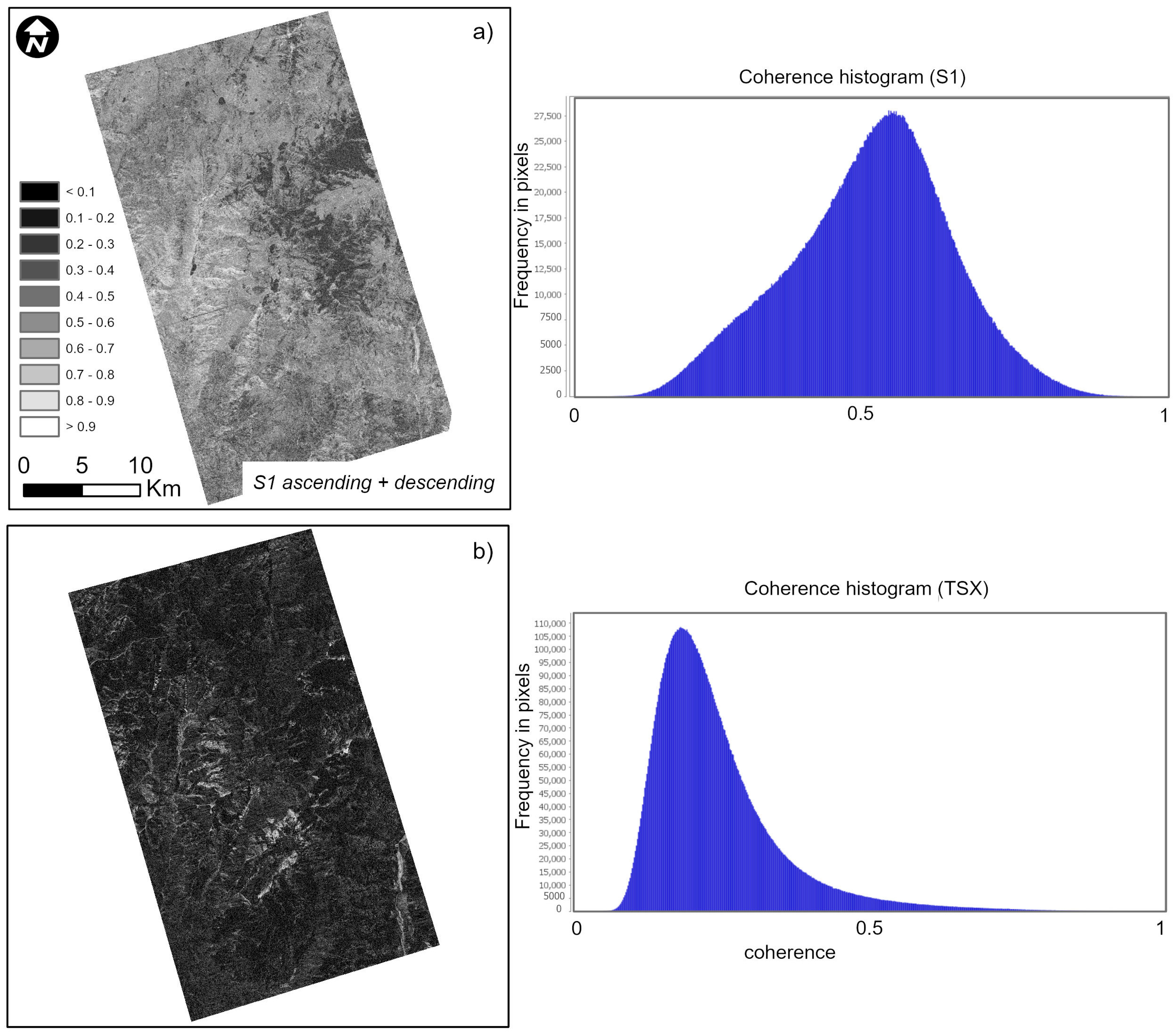

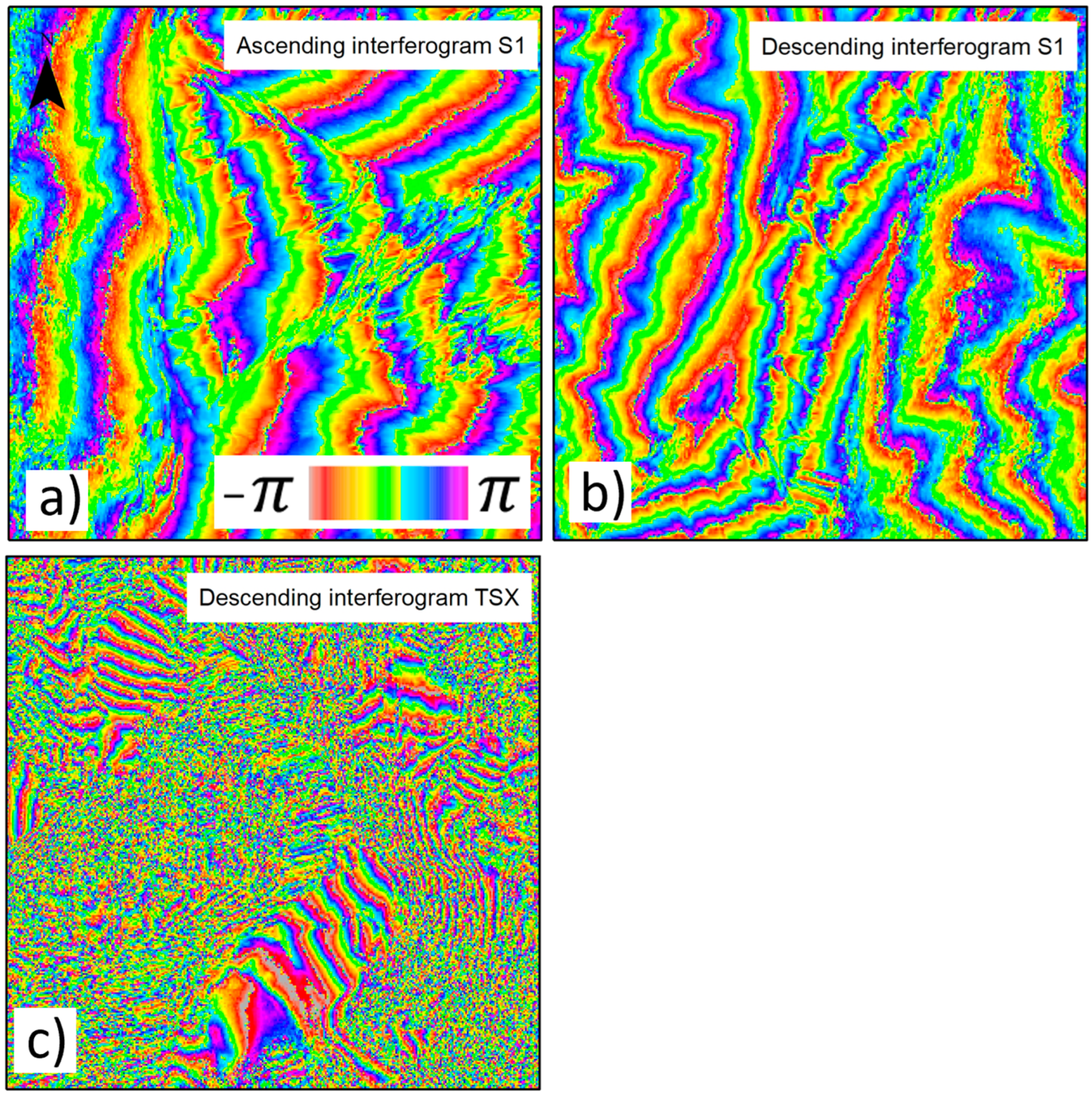

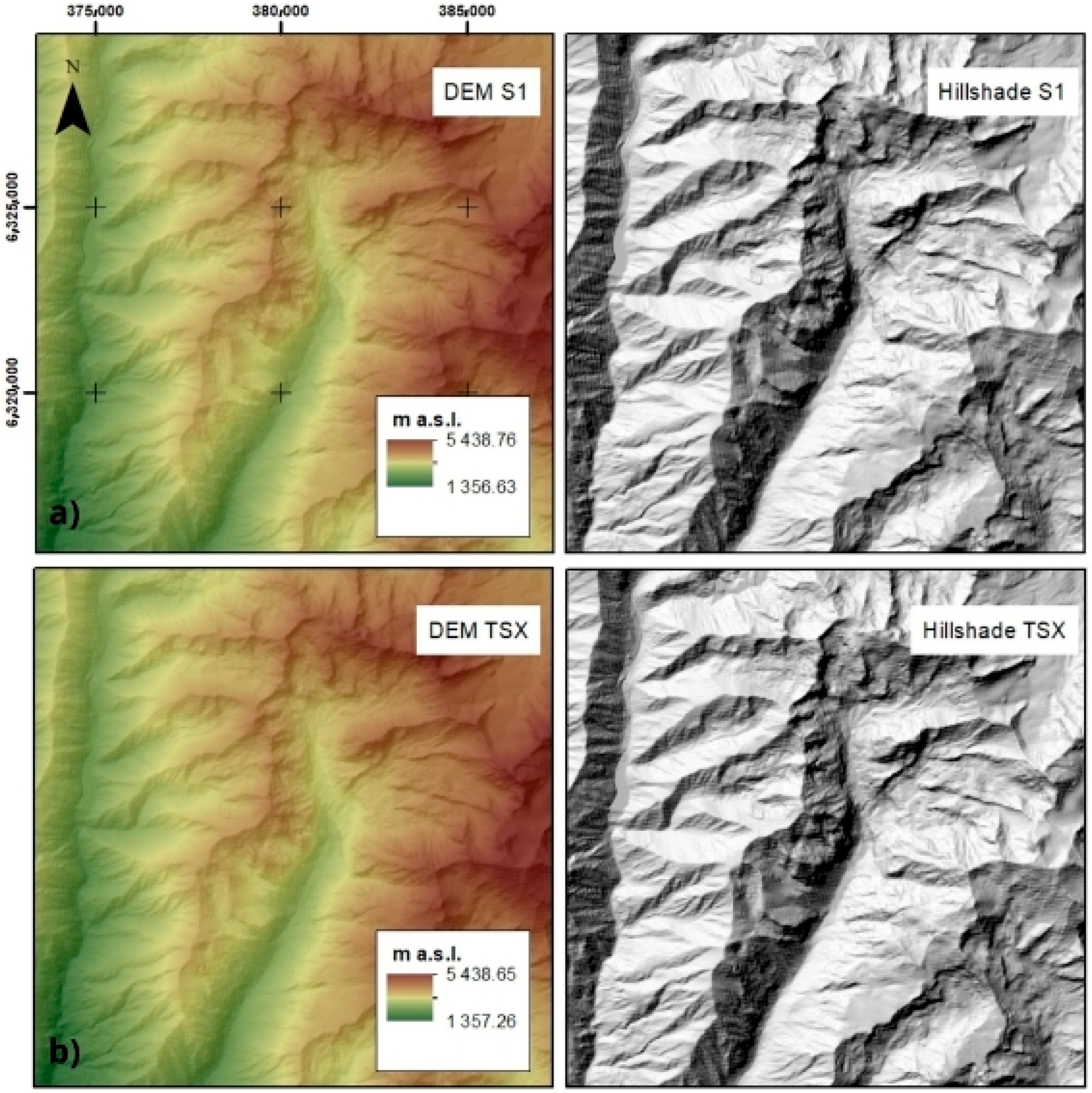

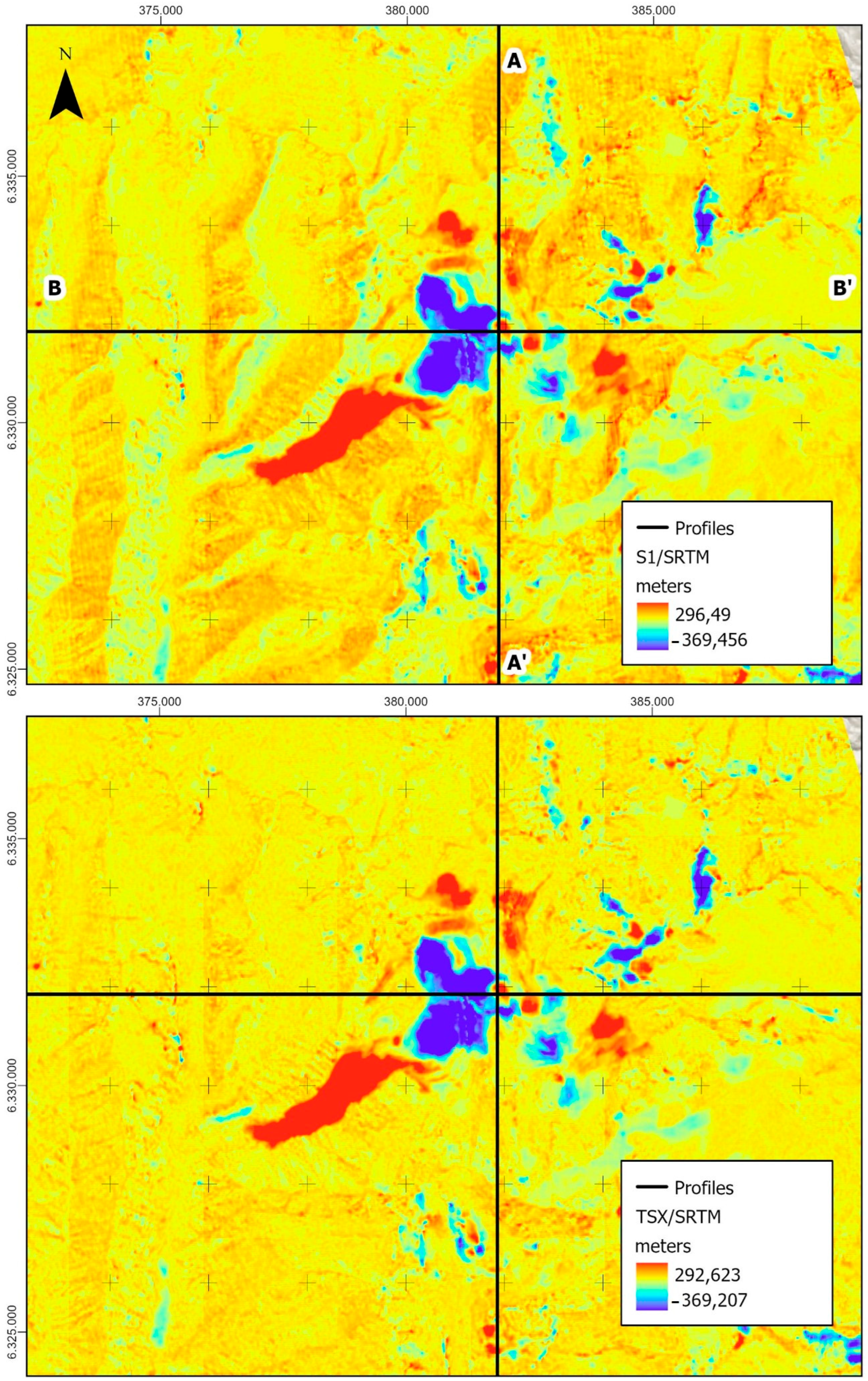

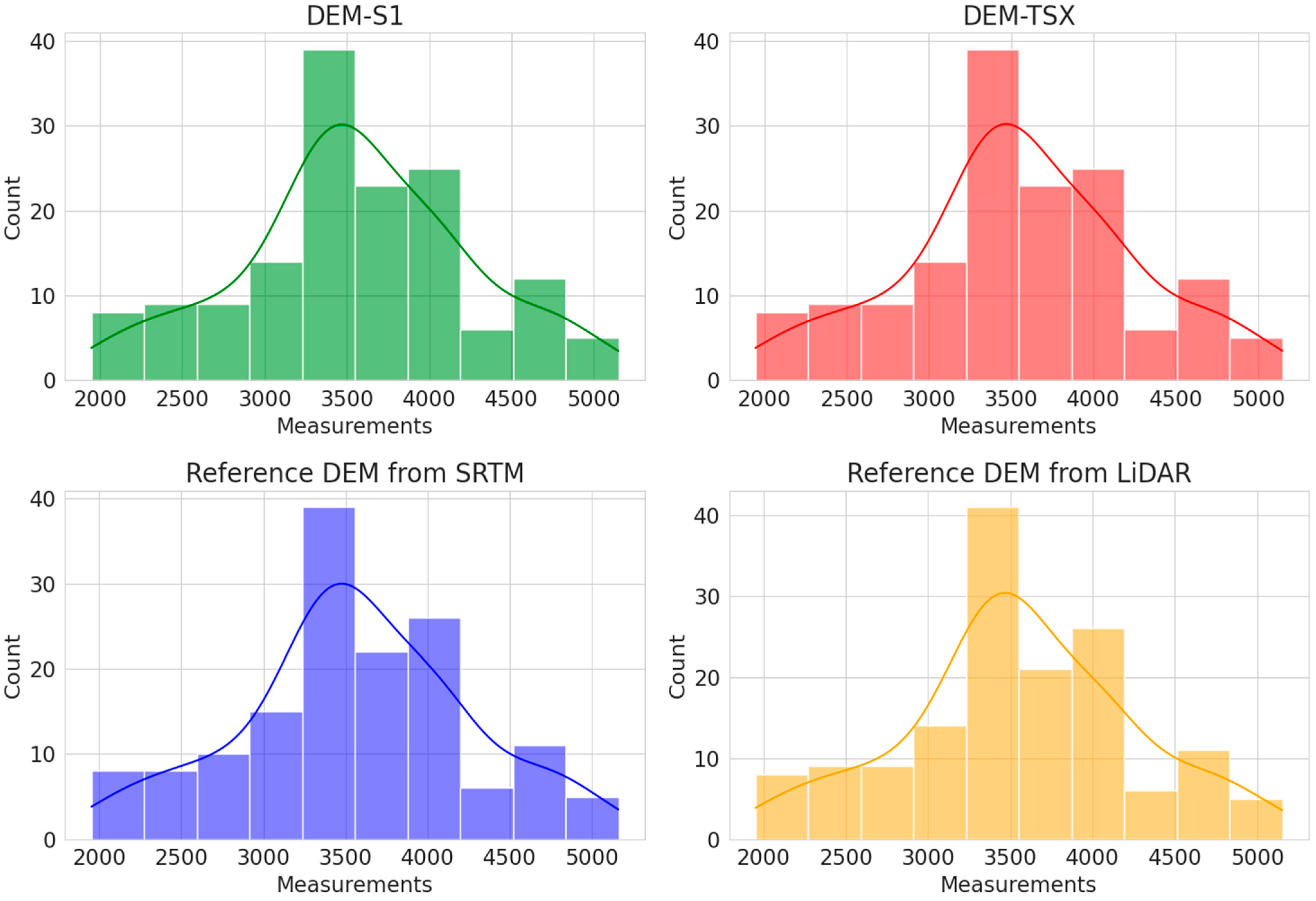

3.1. InSAR DEM Generation

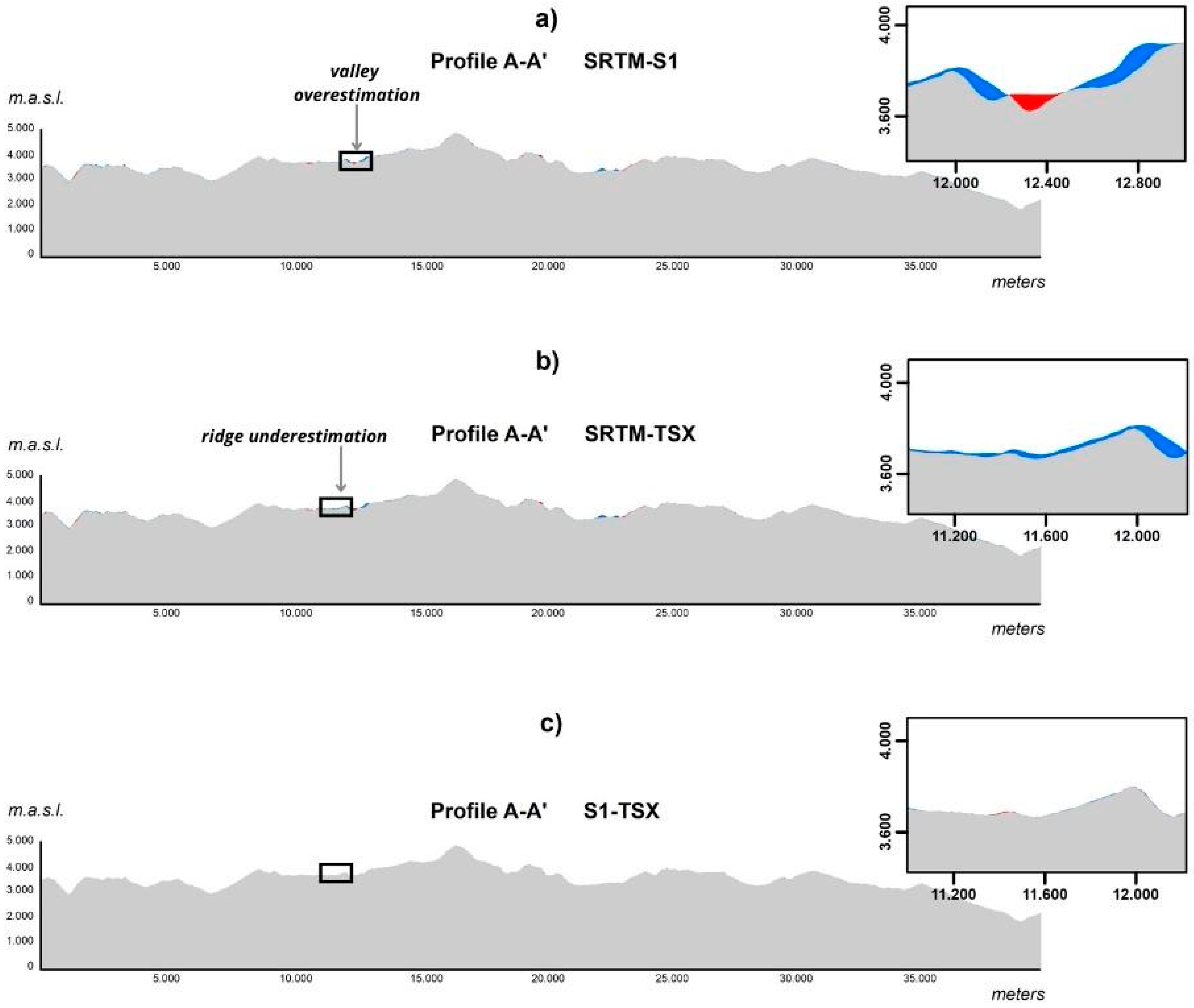

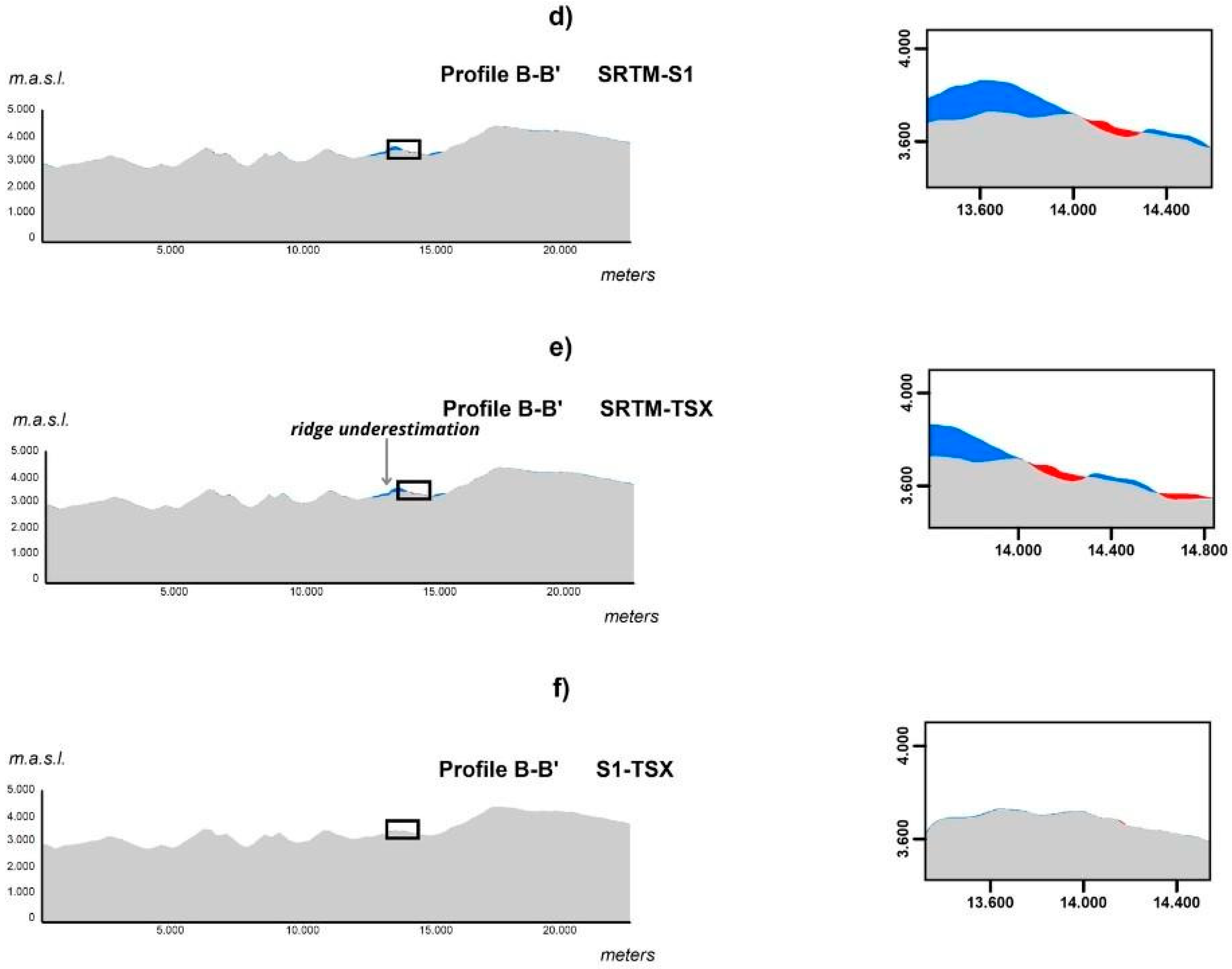

3.2. Comparison of DEM-S1 and DEM-TSX Profiles with SRTM and LiDAR Reference DEMs

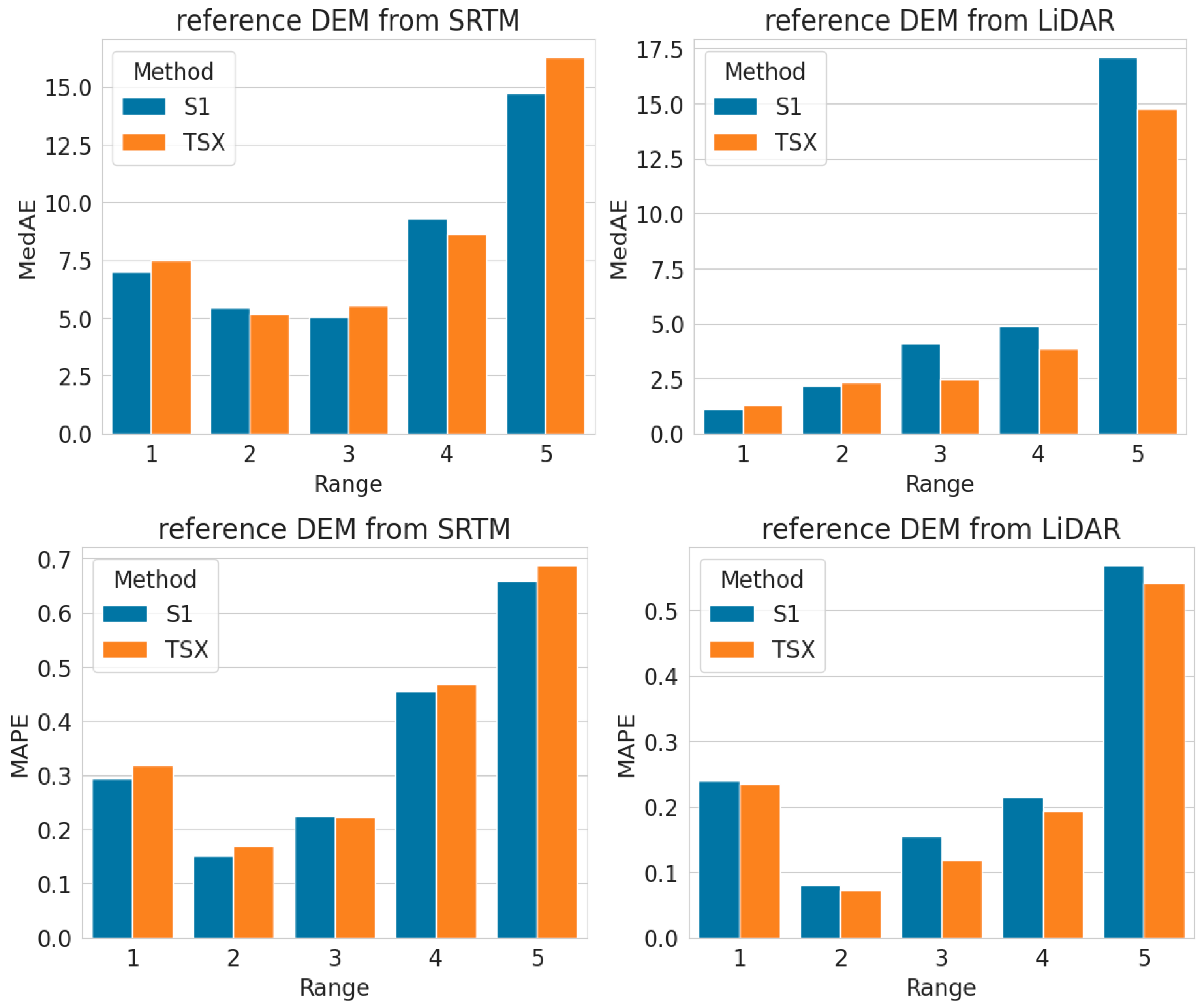

3.3. Vertical Accuracy Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moore, I.D.; Grayson, R.B.; Ladson, A.R. Digital terrain modelling: A review of hydrological, geomorphological, and biological applications. Hydrol. Process. 1991, 5, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, A. Retrieval of digital elevation models from Sentinel-1 radar data–open applications, techniques, and limitations. Open Geosci. 2021, 13, 532–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makineci, H.B.; Karabörk, H. Evaluation digital elevation model generated by synthetic aperture radar data. ISPRS Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, XLI–B1, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, M.; Voda, A.-I. InSAR digital terrain models for mining areas based on Sentinel-1 imagery: A case study in Căliman area. Geopatterns 2020, 5, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głowacki, T.; Kasza, D. Assessment of morphology changes of the end moraine of the Werenskiold Glacier (SW Spitsbergen) using active and passive remote sensing techniques. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakavas, M.P.; Nikolakopoulos, K.G. Digital Elevation Models of Rockfalls and Landslides: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Geosciences 2021, 11, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, J.; Gong, L.; Shang, X. Comparison and validation of different DEM data derived from InSAR. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 12, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deilami, K.; Hashim, M. Very High Resolution Optical Satellites for DEM Generation: A Review. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 2011, 49, 542–554. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan, S.; Shean, D.; Alexandrov, O.; Henderson, S. Automated Digital Elevation Model (DEM) Generation from Very-High-Resolution Planet SkySat Triplet Stereo and Video Imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 173, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmoon, B.; Biniyaz, A.; Liu, Z. Use of High-Resolution Multi-Temporal DEM Data for Landslide Detection. Geosciences 2022, 12, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, W.; Han, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, G. Exploring the Impact of Multitemporal DEM Data on the Susceptibility Mapping of Landslides. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Wang, J.; Shao, D. Glacier Mass Balance in the Manas River Using Ascending and Descending Pass of Sentinel 1A/1B Data and SRTM DEM. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geymen, A. Digital elevation model (DEM) generation using the SAR interferometry technique. Arab. J. Geosci. 2014, 7, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, V.H.; Salcedo, A.P. Modelos Digitales de Elevación: Tendencias, Correcciones Hidrológicas y Nuevas Fuentes de Información; Encuentro de Investigadores en Formación en Recursos Hídricos: Ezeiza, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2014. Available online: http://www.ina.gov.ar/ifrh-2014/Eje1/1.11.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2015).

- Md Ali, A.; Solomatine, D.P.; Di Baldassarre, G. Assessing the Impact of Different Sources of Topographic Data on 1-D Hydraulic Modelling of Floods. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Karimzadeh, S.; Jalal, S.J.; Kamran, K.V.; Shahabi, H.; Homayouni, S.; Al-Ansari, N. A Multi-Sensor Comparative Analysis on the Suitability of Generated DEM from Sentinel-1 SAR Interferometry Using Statistical and Hydrological Models. Sensors 2020, 20, 7214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.; Li, Z.; Tomás, R.; Liu, G.; Yu, B.; Wang, X.; Singleton, A.; Milledge, D.; Jordan, C.; Stockamp, J. Monitoring Activity at the Daguangbao Mega-Landslide (China) Using Sentinel-1 TOPS Time Series Interferometry. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 186, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagli, N.; Cigna, F.; Bianchini, S.; Hölbling, D.; Füreder, P.; Righini, G.; Gigli, G.; Tofani, V.; D’Amato Avanzi, G.; Lanteri, L.; et al. Landslide Mapping and Monitoring by Using Radar and Optical Remote Sensing: Examples from the EC-FP7 Project SAFER. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2016, 4, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigna, F.; Bianchini, S.; Righini, G.; Proietti, C.; Casagli, N. Updating Landslide Inventory Maps in Mountain Areas by Means of Persistent Scatterer Interferometry (PSI) and Photo-Interpretation: Central Calabria (Italy) Case Study. In Proceedings of the International Conference Mountain Risks, Florence, Italy, 24–26 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Massonnet, D.; Rabaute, T. Radar interferometry: Limits and potential. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1993, 31, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosetto, M.; Crippa, B. Quality assessment of interferometric SAR DEMs. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2000, 33, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Yamane, N.; Fujita, K.; Nonaka, T.; Shibayama, T.; Takagishi, S. Accuracy Evaluation of DEM Derived by TerraSAR-X Data in the Himalayan Region. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2008, 37, 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelfattah, R.; Nicolas, J.M. Topographic SAR interferometry formulation for high-precision DEM generation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 40, 2415–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Ge, L.; E, D.; Chang, H. A case study of using external DEM in InSAR DEM generation. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2005, 8, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Wang, T.; Lu, L.; Zhou, W.; Li, D. Reconstruction of DEMs from ERS-1/2 tandem data in mountainous area facilitated by SRTM data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2007, 45, 2325–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, C.; Fu, H.; Zhu, J.; Zuo, T. A framework for correcting ionospheric artifacts and atmospheric effects to generate high accuracy InSAR DEM. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Monti-Guarnieri, A.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F.; Massonnet, D. InSAR Principles—Guidelines for SAR Interferometry Processing and Interpretation, TM-19; ESA Publications: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2007; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11311/550055 (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Shi, X.; Huang, X.; Geng, W. A High Precision DEM Extraction Method Based on InSAR Data. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, IV–3, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, P.; Pérez, W.; Fernández-Sarría, A. Evaluación de Modelos Digitales de Elevación (MDEs) obtenidos a partir de imágenes Sentinel-1 en la Región Metropolitana de Chile. In Proceedings of the Teledetección: Hacia Una Visión Global del Cambio Climático. Actas del XVIII Congreso de la Asociación Española de Teledetección, Valladolid, Spain, 24–27 September 2019; pp. 373–376. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Feng, Z.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Liu, N. Verification of the Accuracy of Sentinel-1 for DEM Extraction Error Analysis under Complex Terrain Conditions. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 133, 104157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Arief, R.; Dyatmika, H.S.; Maulana, R.; Rahayu, M.I.; Sondita, A.; Setiyoko, A.; Maryanto, A.; Budiono, M.E.; Sudiana, D. Digital Elevation Model (DEM) Generation with Repeat Pass Interferometry Method Using TerraSAR-X/Tandem-X (Study Case in Bandung Area). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 280, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gdulová, K.; Marešová, J.; Moudrý, V. Accuracy assessment of the global TanDEM-X digital elevation model in a mountain environment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 241, 111724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección Meteorológica de Chile (DGAC). Datos Climáticos Históricos. 2020. Available online: https://climatologia.meteochile.gob.cl/application/requerimiento/producto/RE3002 (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Araya-Vergara, J.F.; Börgel, R. Definición de parámetros para establecer un banco nacional de riesgos y amenazas naturales, y criterios para su diseño; Oficina Nacional de Emergencia (ONEMI), Ministerio del Interior: Santiago, Chile, 1972. Available online: http://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/147470 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Alaska Satellite Facility (ASF). ASF Home. 2020. Available online: https://asf.alaska.edu/ (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Centro de Ciencia del Clima y la Resiliencia (CR2). Explorador CR2. 2020. Available online: http://explorador.cr2.cl/ (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- USGS/NASA. EarthExplorer Platform. 2020. Available online: https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Zebker, H.A.; Goldstein, R.M. Topographic Mapping from Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar Observations. J. Geophys. Res. 1986, 91, 4993–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, P.A.; Hensley, S.; Joughin, I.R.; Li, F.K.; Madsen, S.N.; Rodriguez, E.; Goldstein, R.M. Synthetic aperture radar interferometry. Proc. IEEE 2000, 88, 333–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Anderson, A.I.; Herndon, K.E.; Thapa, R.B.; Cherrington, E. The SAR Handbook: Comprehensive Methodologies for Forest Monitoring and Biomass Estimation; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Crosetto, M.; Solari, L. Satellite Interferometry Data Interpretation and Exploitation: Case Studies from the European Ground Motion Service (EGMS); Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; ISBN 9780323995746. [Google Scholar]

- Bamler, R.; Hartl, P. Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry. Inverse Probl. 1998, 14, R1–R54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbiol, R.; Palà, V.; Pérez, F.; Castillo, M.; Crosetto, M. Aplicaciones de la tecnología InSAR a la cartografía. In Proceedings of the IX Congreso Nacional de Teledetección, Lleida, Spain, 19–21 September 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen, R.F. Radar Interferometry: Data Interpretation and Error Analysis; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; 328p. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.W.; Zebker, H.A. Network approaches to two-dimensional phase unwrapping: Intractability and two new algorithms. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2000, 17, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal Páez, P.; Fernández-Sarría, A.; González-Bonilla, M.J.; Cuerda, J.M.; Casal, N.; Pérez-Martínez, W.; Ortega, J.; Sarricolea, P. Evaluación de Modelos Digitales de Elevación Obtenidos Mediante Imágenes PAZ y la Técnica InSAR en una Zona Cordillerana de la Región Metropolitana de Chile. In XX Congreso de la Asociación Española de Teledetección “Teledetección y Cambio Global: Retos y Oportunidades para un Crecimiento Azul”; Caballero, I., Navarro, G., Barbero, L., Gómez-Enri, J., Eds.; Instituto de Ciencias Marinas de Andalucía (ICMAN-CSIC) y Universidad de Cádiz: Cádiz, Spain, 2024; pp. 679–682. ISBN 978-84-9828-941-1. [Google Scholar]

- Soza, D.A.; Falaschi, D. Validation of Digital Elevation Models in the Central Andes of Chile. Rev. Geogr. Chile Terra Australis 2020, 56, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuvelink, G.B.M. Error Propagation in Environmental Modelling with GIS, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2018; Available online: https://otexts.org/fpp2/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Benesty, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Cohen, I. Pearson Correlation Coefficient. In Noise Reduction in Speech Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, I.P.; Bugya, T.; Czigány, S.; Székely, B.; Timár, G. How to Avoid False Interpretations of Sentinel-1A TOPSAR Interferometric Data in Landslide Mapping? A Case Study: Recent Landslides in Transdanubia, Hungary. Nat. Hazards 2019, 96, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bru, G.; Ezquerro, P.; López-Vinielles, J.; Reyez-Carmona, C.; Guardiola, A.; Béjar, P. Manual Básico Sobre el uso de Datos InSAR para Medir Desplazamientos de la Superficie del Terreno, 1st ed.; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Deledalle, C.A.; Denis, L.; Tupin, F. NL-InSAR: Nonlocal interferogram estimation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2010, 49, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, F.; Cozzolino, D.; Zhu, X.X.; Verdoliva, L.; Poggi, G. InSAR-BM3D: A nonlocal filter for SAR interferometric phase restoration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 3456–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, R.; Lee, S.-R.; Kwon, T.-H. Long-Term Remote Monitoring of Ground Deformation Using Sentinel-1 Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR): Applications and Insights into Geotechnical Engineering Practices. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Joshi, P.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ghosh, A.; Garg, R.D.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Evaluation of Vertical Accuracy of Open Source Digital Elevation Model (DEM). Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2013, 21, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Image | Acquisition Date | Acquisition Mode | Polarization | Orbit | Spatial Resolution | Bp (m) | Bt (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 m | 9 August 2017 | IW (TopSAR) | VV | ascending | 9 × 14 m | 65 | 12 |

| S1 s | 21 August 2017 | ||||||

| S1 m | 9 August 2017 | IW (TopSAR) | VV | ascending | 9 × 14 m | 66 | 12 |

| S1 s | 21 August 2017 | ||||||

| S1 m | 27 February 2017 | IW (TopSAR) | VV | descending | 9 × 14 m | 24 | 12 |

| S1 s | 11 March 2017 | ||||||

| S1 m | 27 February 2017 | IW (TopSAR) | VV | descending | 9 × 14 m | 100 | 36 |

| S1 s | 4 April 2017 | ||||||

| TSX m | 4 August 2017 | StripMap | HH | descending | 0.9 × 1.9 m | 184 | 66 |

| TSX s | 9 October 2017 |

| Corr (%) | EV (%) | MAPE (%) | MedAE (m) | MAE (m) | rMSE (m) | Standard Dev (m) | DEM Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEM reference from SRTM | |||||||

| 99.95 ± 0.01 | 99.91 ± 0.02 | 35 ± 1 | 7.07 ± 0.10 | 12.72 ± 0.56 | 23.26 ± 0.12 | 702.13 | S1 |

| 99.56 ± 0.02 | 99.90 ± 0.03 | 37 ± 2 | 7.49 ± 0.22 | 13.32 ± 0.38 | 24.05 ± 0.11 | 701.85 | TSX |

| DEM reference from LiDAR | |||||||

| 99.95 ± 0.02 | 99.92 ± 0.03 | 25 ± 2 | 3.97 ± 0.25 | 9.19 ± 0.25 | 20.16 ± 0.15 | 702.13 | S1 |

| 99.65 ± 0.03 | 99.92 ± 0.03 | 23 ± 1 | 3.26 ± 0.15 | 8.60 ± 0.18 | 19.63 ± 0.15 | 701.85 | TSX |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Flores, F.; Vidal-Páez, P.; Mena, F.; Pérez-Martínez, W.; Oliva, P. Evaluation of Digital Elevation Models (DEM) Generated from the InSAR Technique in a Sector of the Central Andes of Chile, Using Sentinel 1 and TerraSar-X Images. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010392

Flores F, Vidal-Páez P, Mena F, Pérez-Martínez W, Oliva P. Evaluation of Digital Elevation Models (DEM) Generated from the InSAR Technique in a Sector of the Central Andes of Chile, Using Sentinel 1 and TerraSar-X Images. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):392. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010392

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlores, Francisco, Paulina Vidal-Páez, Francisco Mena, Waldo Pérez-Martínez, and Patricia Oliva. 2026. "Evaluation of Digital Elevation Models (DEM) Generated from the InSAR Technique in a Sector of the Central Andes of Chile, Using Sentinel 1 and TerraSar-X Images" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010392

APA StyleFlores, F., Vidal-Páez, P., Mena, F., Pérez-Martínez, W., & Oliva, P. (2026). Evaluation of Digital Elevation Models (DEM) Generated from the InSAR Technique in a Sector of the Central Andes of Chile, Using Sentinel 1 and TerraSar-X Images. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010392