A Synchronous Data Approach to Analyze Cloud-Induced Effects on Photovoltaic Plants Using Ramp Detection Algorithms

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Ramps Detection Methods

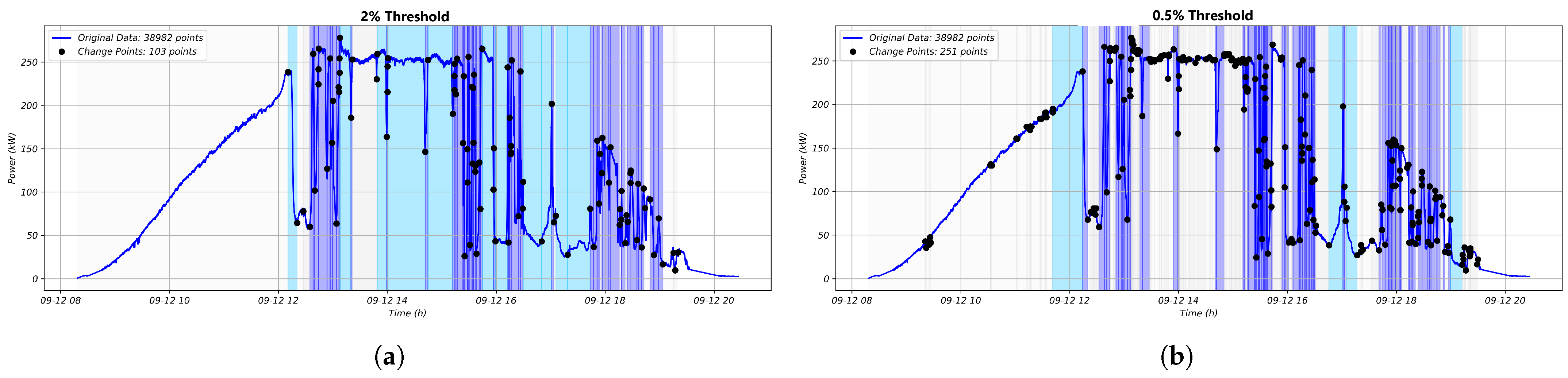

2.1. Threshold Selection

2.2. Modified SDA

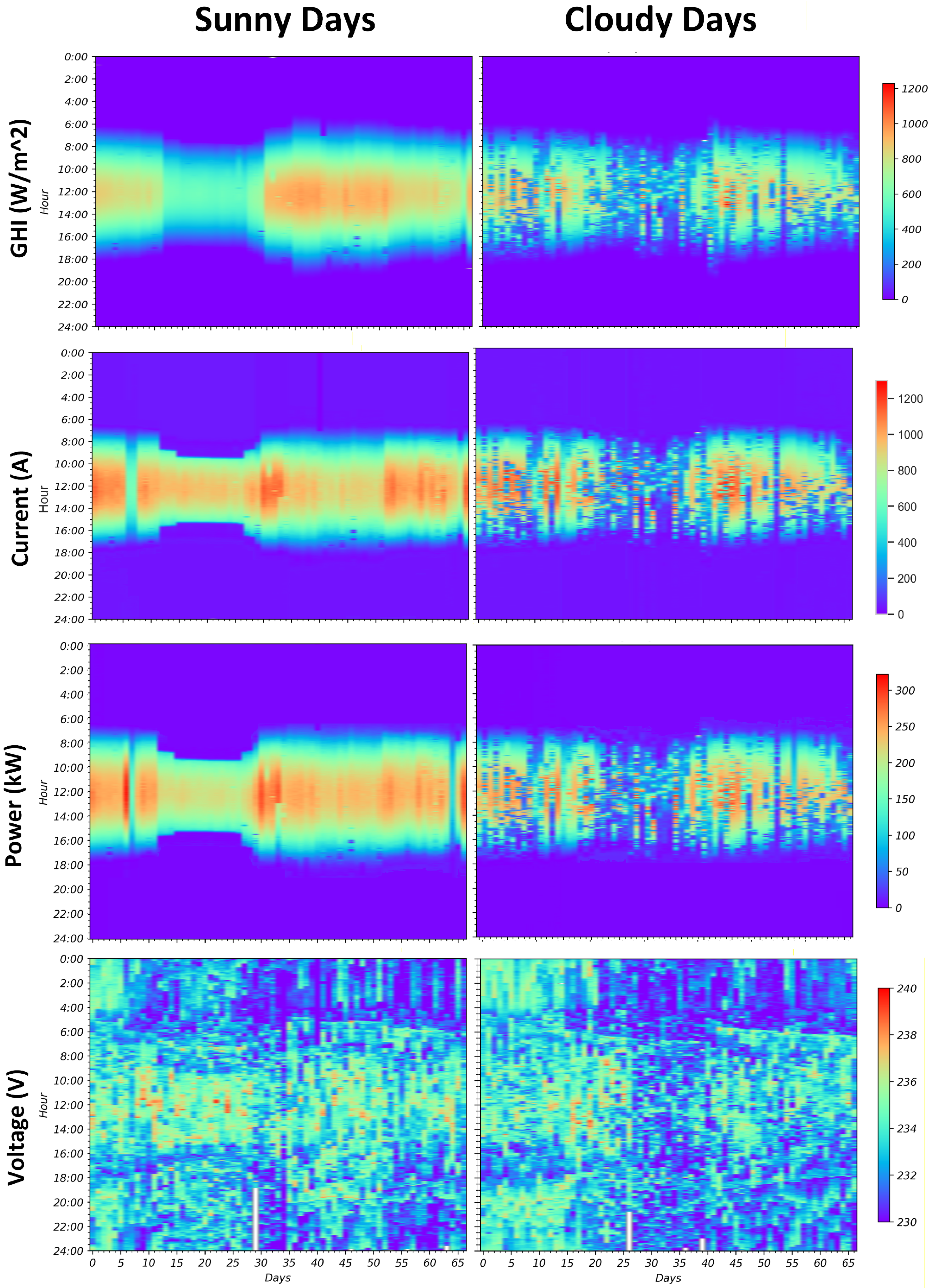

3. Data Set

- Power. Correspond to the average of the instantaneous power (P). It is calculated based on the instantaneous values of current and voltage as shown in Equation (1)where , and refers to the instantaneous voltage, current and power correspondingly, and N is the number of samples in one second.

- Current. It corresponds to the RMS values according to Equation (2)

- Voltage. As well as the current, it corresponds to an RMS value according to Equation (3)

- Irradiance. Irradiance correspond to the Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI), read every 100 ms and aggregated every second.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Analysis of the Initial Dataset

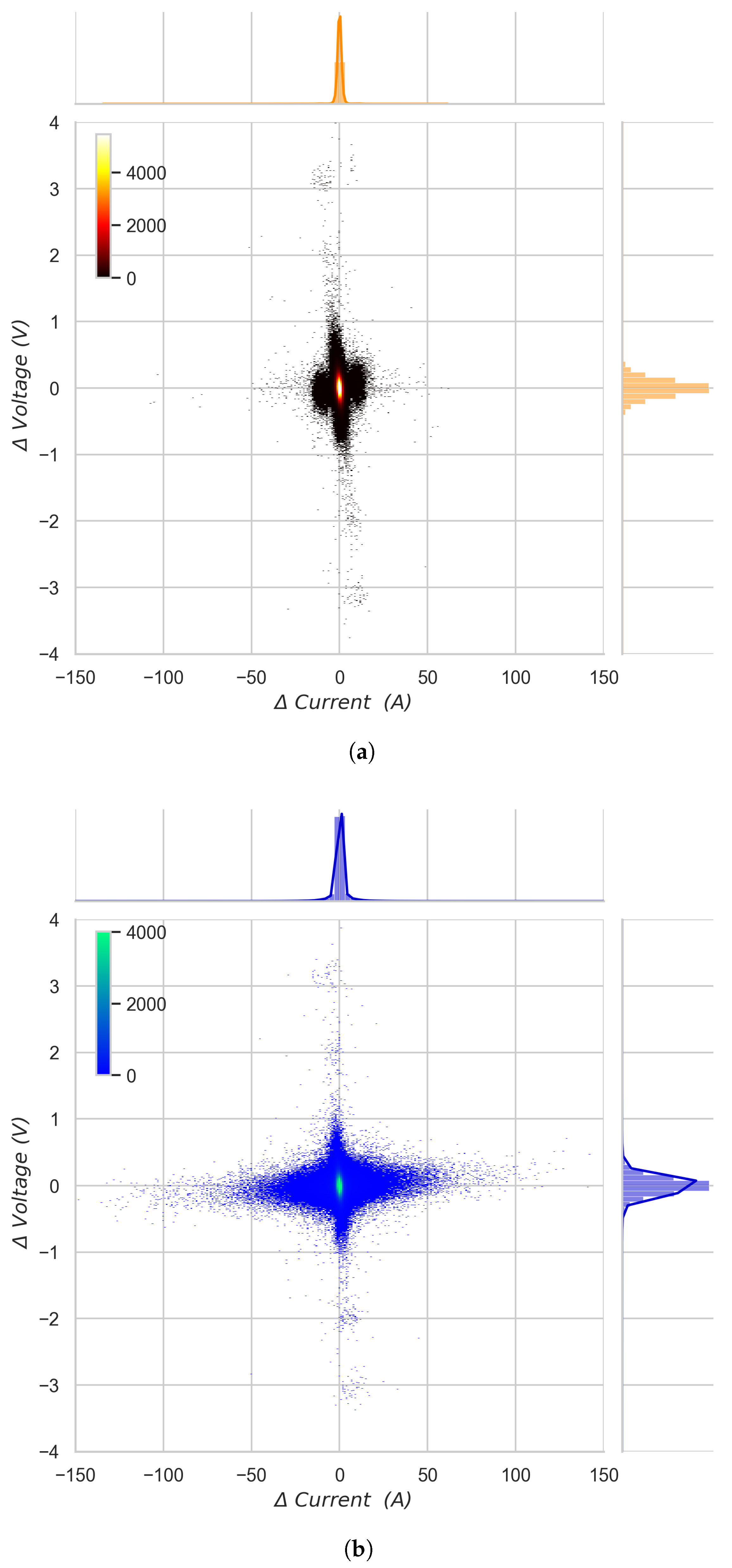

4.2. Data–Gradient Correlation Analysis

4.3. Algorithm-Based Detection and Evaluation of Power, Current, and Irradiance Ramps

4.3.1. Evaluation of the SDA Threshold Effect on GHI, Current and Power

4.3.2. GHI, Current, and Power Comparison

4.3.3. SPRR and SPRE

4.4. Analysis of Voltage Fluctuations Induced by Cloud Passage

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IRENA. Capacity and Generation, Statistics Time Series. 2025. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Data/View-data-by-topic/Capacity-and-Generation/Statistics-Time-Series (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- IRENA. Capacity and Generation, Country Rankings. 2025. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Data/View-data-by-topic/Capacity-and-Generation/Country-Rankings (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Shafiullah, M.; Ahmed, S.D.; Al-Sulaiman, F.A. Grid Integration Challenges and Solution Strategies for Solar PV Systems: A Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 52233–52257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samu, R.; Calais, M.; Shafiullah, G.M.; Moghbel, M.; Shoeb, M.A.; Nouri, B.; Blum, N. Applications for solar irradiance nowcasting in the control of microgrids: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 147, 111187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, A.; Lehtonen, M. A comprehensive voltage control strategy with voltage flicker compensation for highly PV penetrated distribution networks. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2019, 172, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łowczowski, K.; Nadolny, Z. Voltage Fluctuations and Flicker in Prosumer PV Installation. Energies 2022, 15, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, B.; Fabel, Y.; Blum, N.; Schnaus, D.; Zarzalejo, L.F.; Kazantzidis, A.; Wilbert, S. Ramp Rate Metric Suitable for Solar Forecasting. Solar RRL 2024, 8, 2400468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaible, J.; Nouri, B.; Höpken, L.; Kotzab, T.; Loevenich, M.; Blum, N.; Hammer, A.; Stührenberg, J.; Jäger, K.; Becker, C.; et al. Application of nowcasting to reduce the impact of irradiance ramps on PV power plants. EPJ Phtovoltaics 2024, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Su, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Smith, D. Study of variability metrics for solar irradiance and photovoltaic output. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 16–20 July 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.S.; Maharjan, S.; Albert; Srinivasan, D. Ramp-rate limiting strategies to alleviate the impact of PV power ramping on voltage fluctuations using energy storage systems. Sol. Energy 2022, 234, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agüera-Pérez, A.; Espinosa-Gavira, M.J.; Palomares-Salas, J.C.; de-la Rosa, J.J.G.; Sierra-Fernández, J.M.; Florencias-Oliveros, O. Meteorological contexts in the analysis of cloud-induced photovoltaic transients: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, L.; Charbonnier, B.; Paul, N.; Dubost, S.; Blanc, P. Towards a standardized procedure to assess solar forecast accuracy: A new ramp and time alignment metric. Sol. Energy 2017, 150, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logothetis, S.A.; Salamalikis, V.; Nouri, B.; Remund, J.; Zarzalejo, L.F.; Xie, Y.; Wilbert, S.; Ntavelis, E.; Nou, J.; Hendrikx, N.; et al. Solar Irradiance Ramp Forecasting Based on All-Sky Imagers. Energies 2022, 15, 6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrikx, N.Y.; Barhmi, K.; Visser, L.R.; de Bruin, T.A.; Po, M.; Salah, A.A.; van Sark, W.G. All sky imaging-based short-term solar irradiance forecasting with Long Short-Term Memory networks. Sol. Energy 2024, 272, 112463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Zhang, J.; Feng, C.; Florita, A.R.; Sun, Y.; Hodge, B.M. Characterizing and analyzing ramping events in wind power, solar power, load, and netload. Renew. Energy 2017, 111, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, E. Increased Penetration of Distributed Roof-Top Photovoltaic Systems in Secondary Low Voltage Networks: Interconnection. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Du, Y.; Lim, E.; Wen, H.; Yan, K.; Kirtley, J. Power ramp-rates of utility-scale PV systems under passing clouds: Module-level emulation with cloud shadow modeling. Appl. Energy 2020, 268, 114980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, T.E.; Perez, R. Quantifying PV power Output Variability. Sol. Energy 2010, 84, 1782–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Ramos, V.; Pallares-Lopez, V.; Real-Calvo, R.; Gonzalez-Redondo, M.; Santiago-Chiquero, I. Implementation and Characterization of a High Precision Monitoring System for Photovoltaic Power Plants Using Self-Made Phasor Measurement Units. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 37383–37393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, T.E.; Perez, R.; Kleissl, J.; Renne, D.; Stein, J. Reporting of irradiance modeling relative prediction errors. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 2013, 21, 1514–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaie, M.M.; Sezer, D.; Zareipour, H. An Updated Review and Comparison of Wind Power Ramp Detection Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Kingston, ON, Canada, 6–9 August 2024; pp. 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, C.; Costa, A.; Cuerva, Á.; Landberg, L.; Greaves, B.; Collins, J. A wavelet-based approach for large wind power ramp characterisation. Wind Energy 2013, 16, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucatelli, P.J.; Nascimento, E.G.; Santos, A.; Arce, A.M.; Moreira, D.M. An investigation on deep learning and wavelet transform to nowcast wind power and wind power ramp: A case study in Brazil and Uruguay. Energy 2021, 230, 120842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevlian, R.; Rajagopal, R. Detection and statistics of wind power ramps. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 3610–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freidenthal, S. EVSystem - Historian Data Compression. Available online: http://www.evsystems.net/files/GE_Historian_Compression_Overview.ppt (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Weatherford. CygNet Swinging Door Compression. Available online: https://softwaredocs.weatherford.com/cygnet/94/Content/Topics/History/CygNet%20Swinging%20Door%20Compression.htm (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Willy, D.; Dyreson, A.; Flood, R.K. Dead band method for solar irradiance and power ramp detection algorithms. In Proceedings of the 43rd ASES National Solar Conference, 2014, San Francisco, CA, USA, 6–10 July 2014; pp. 1204–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Bristol, E.H. Swinging door trending: Adaptive trend recording? In Proceedings of the ISA National Conference Proceedings, 1990, Houston, TX, USA, 14–18 October 1990; pp. 749–754. [Google Scholar]

- Swinging Door Algorithm for Process Value Archiving - WinCC V7.2: Working with WinCC - ID: 73506085 - Industry Support Siemens. Available online: https://support.industry.siemens.com/cs/mdm/73506085?c=46159586187&lc=en-BY (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Mikhaylov, A.F. swinging-door, version 2.0.1; Implementation of the Swinging Door Algorithm in Python; Python Package Index (PyPI). 2025. Available online: https://pypi.org/project/swinging-door/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Haghighat, M.; Niroomand, M.; Tafti, H.D. An Adaptive Power Ramp Rate Control Method for Photovoltaic Systems. IEEE J. Photovoltaics 2022, 12, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme-Dominguez, J.M.; García-López, F.D.P.; Martinez, S. Power Ramp-Rate Control via power regulation for storageless grid-connected photovoltaic systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 138, 107848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENTSO-E Network Code for Requirements for Grid Connection Applicable to All Generators; European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E): Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- Gevorgian, V.; Booth, S. Review of PREPA Technical Requirements for Interconnecting Wind and Solar Generation; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energinet. Technical Regulation 3.2. 2 for PV Power Plants with a Power Output Above 11 kW; Technical Report; Energinet: Erritsø, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 19964-2012; Technical Requirements for Connecting Photovoltaic Power Station to Power System. National Standard of the People’ Republic of China, Standardization Administration China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Stein, J.; Hansen, C.; Reno, M. The variability index: A new and novel metric for quantifying irradiance and PV output variability. In Proceedings of the 7th Renewable Energy Policy and Marketing Conference. World Renewable Energy Forum (WREF), Denver, CO, USA, 13–17 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Florita, A.; Hodge, B.M.; Orwig, K. Identifying wind and solar ramping events. In Proceedings of the IEEE Green Technologies Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 4–5 April 2013; pp. 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarés-López, V.; Real-Calvo, R.J.; Jiménez, S.D.R.; González-Redondo, M.; Moreno-García, I.; Santiago, I. Monitoring of Energy Data with Seamless Temporal Accuracy Based on the Time-Sensitive Networking Standard and Enhanced µPMUs. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Ramos, V.; Cuesta, F.; Pallares-Lopez, V.; Santiago, I. Software Integration of Power System Measurement Devices with AI Capabilities. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GPS.gov. Global Positioning System Accuracy. Available online: https://www.gps.gov (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Bakdi, A.; Bounoua, W.; Guichi, A.; Mekhilef, S. Real-time fault detection in PV systems under MPPT using PMU and high-frequency multi-sensor data through online PCA-KDE-based multivariate KL divergence. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 125, 106457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdphol, T.; Matsukawa, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Mitani, Y. Application of PMUs to monitor large-scale PV penetration infeed on frequency of 60 Hz Japan power system: A case study from Kyushu Island. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 185, 106393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Qiu, S.; Wang, Z.; Kimber, A. Micro-PMU Field Deployment and Data Analysis in Utility Distribution Grid with High Penetration of Distributed Energy Resources. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, Seattle, WA, USA, 21–25 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE 1588-2008; Standard for a Precision Clock Synchronization Protocol for Networked Measurement and Control Systems. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2008.

- IEEE C37.118.2-2011; Standard for Synchrophasor Data Transfer for Power Systems. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2011.

- Santiago, I.; García-Quintero, J.; Mengibar-Ariza, G.; Trillo-Montero, D.; Real-Calvo, R.J.; Gonzalez-Redondo, M. Analysis of Some Power Quality Parameters at the Points of Common Coupling of Photovoltaic Plants Based on Data Measured by Inverters. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Decreto 1565/2010; Por el que se Regulan y Modifican Determinados Aspectos Relativos a la Actividad de Producción de Energía Eléctrica en Régimen Especial. Ministerio de Industria, Turismo y Comercio, Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain, 2010.

- Rönnberg, S.; Bollen, M.; Larsson, A. Grid impact from PV-installations in northern Scandinavia. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference and Exhibition on Electricity Distribution (CIRED 2013), Stockholm, Sweden, 10–13 June 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- IEC TR 61000-3-6:2008; Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)—Part 3-6: Limits—Assessment of Emission Limits for the Connection of Distorting Installations to MV, HV and EHV Power Systems. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

| PCC | Power | Current | GHI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage Test 1 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| Voltage Test 2 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.72 |

| Voltage Test 3 | 0.71 | 0.7 | 0.68 |

| Voltage Test 4 | 0.52 | 0.5 | 0.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arenas-Ramos, V.; Santiago-Chiquero, I.; Gonzalez-Redondo, M.; Real-Calvo, R.; Florencias-Oliveros, O.; Pallarés-López, V. A Synchronous Data Approach to Analyze Cloud-Induced Effects on Photovoltaic Plants Using Ramp Detection Algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010371

Arenas-Ramos V, Santiago-Chiquero I, Gonzalez-Redondo M, Real-Calvo R, Florencias-Oliveros O, Pallarés-López V. A Synchronous Data Approach to Analyze Cloud-Induced Effects on Photovoltaic Plants Using Ramp Detection Algorithms. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):371. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010371

Chicago/Turabian StyleArenas-Ramos, Victoria, Isabel Santiago-Chiquero, Miguel Gonzalez-Redondo, Rafael Real-Calvo, Olivia Florencias-Oliveros, and Víctor Pallarés-López. 2026. "A Synchronous Data Approach to Analyze Cloud-Induced Effects on Photovoltaic Plants Using Ramp Detection Algorithms" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010371

APA StyleArenas-Ramos, V., Santiago-Chiquero, I., Gonzalez-Redondo, M., Real-Calvo, R., Florencias-Oliveros, O., & Pallarés-López, V. (2026). A Synchronous Data Approach to Analyze Cloud-Induced Effects on Photovoltaic Plants Using Ramp Detection Algorithms. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010371