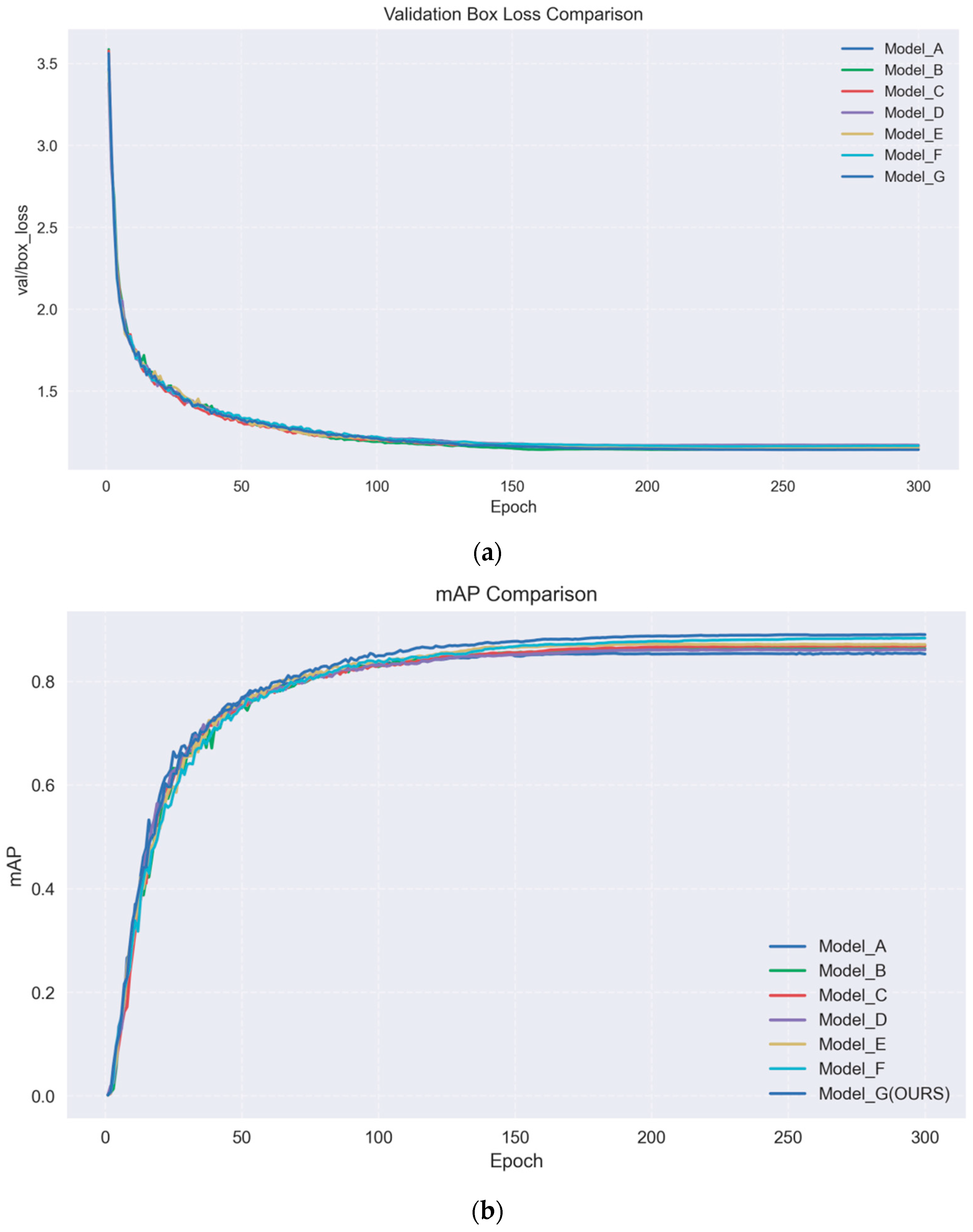

3.1. Overall of Network

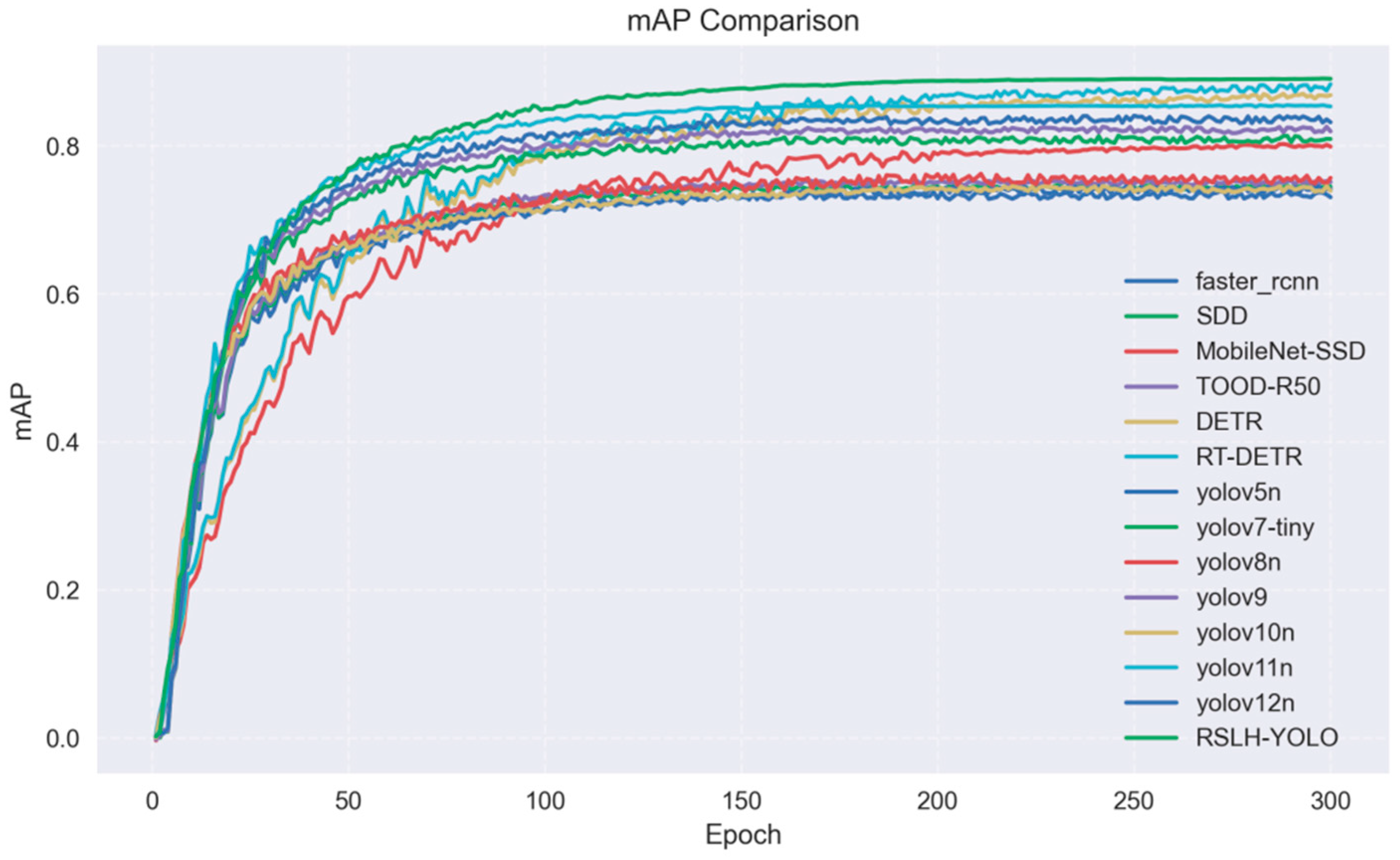

The YOLO series [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] has emerged as a leading framework for real-time object detection. YOLOv12 [

29] was the latest version of the YOLO series, which was released in February 2025. However, YOLOv11 [

30,

31] was selected as the baseline for RSLH-YOLO. As shown in

Table 1, YOLOv11 achieves the highest mAP and precision while maintaining manageable GFLOPs and FPS among the YOLO series. This is an essential consideration given the stringent hardware constraints in mining environments. Furthermore, the smallest density variant, YOLOv11n, is adopted for the same reason: it balances accuracy and efficiency under limited computational resources on site, as shown in

Table 2.

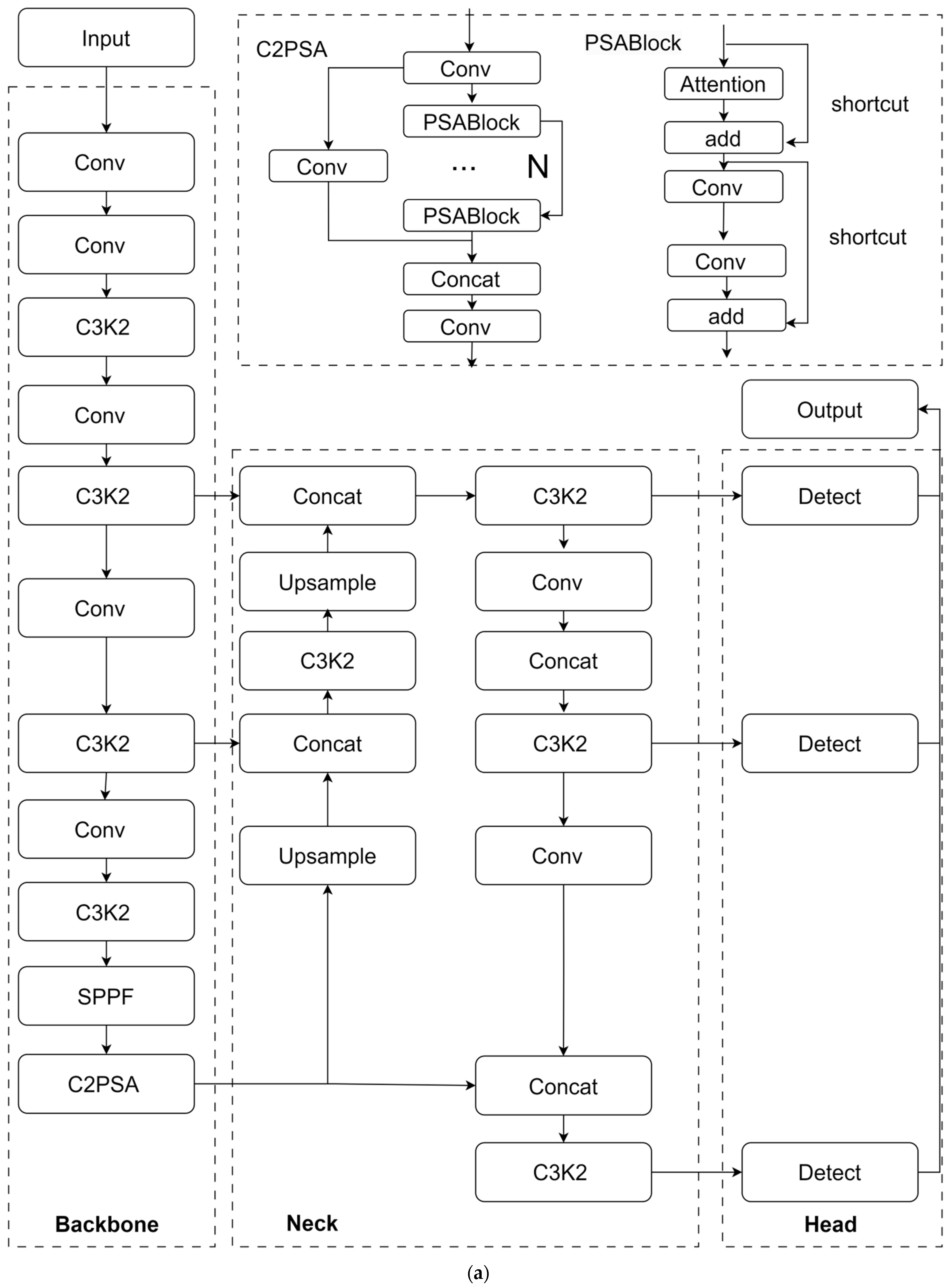

As shown in

Figure 1a, the architecture of YOLOv11 consists of three main components: Backbone, Neck, and Head. The Backbone focuses on feature extraction, employing C3k2 (a cross-stage portion of kernel size 2) block, SPPF (Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast), and C2PSA (Convolutional Block with Parallel Spatial Attention) components. These components transform raw image data into multi-scale feature maps. These feature maps, which contain rich local and global information, are subsequently passed to the neck for advanced integration. The neck component serves as an intermediate processing stage, employing specialized layers to aggregate and enhance feature representations across different scales. The enhanced feature maps generated by the neck are then routed to the head for the final detection tasks. The head component serves as the prediction mechanism, generating final outputs for object localization and classification based on refined feature maps. Using a multi-branch design, the head processes the multi-scale features provided by the neck. Each branch is optimized to detect objects of specific sizes, including small, medium, and large targets. The final detection outputs, encompassing the object categories, bounding box coordinates, and confidence scores, are produced by the head.

The architecture of the improved RSLH-YOLO network is illustrated in

Figure 1b. As shown in

Table 3, this paper primarily improves the YOLOv11n model in three aspects: the backbone, neck, and head. The specific enhancements are as follows. Firstly, the backbone is optimized by replacing the Conv, C3K2, and SPPF connection layers with RFAConv, C3K2_RFAConv, and FPSConv, respectively. These replacements expand the receptive field, enhance contextual information capture, reduce information loss, and enable multi-scale feature extraction. Subsequently, a ReCa-PAFPN integrating SBA and C3K2_RFAConv is introduced to replace the original neck of YOLOv11 to improve feature fusion and address large-scale span variations. To better detect small objects, a dedicated small-target detection layer is added to the head section. Finally, to ensure model lightweighting and better solving the occlusion problem, a lightweight EGNDH detection head replaces the original detection head.

3.2. Improvement of Backbone

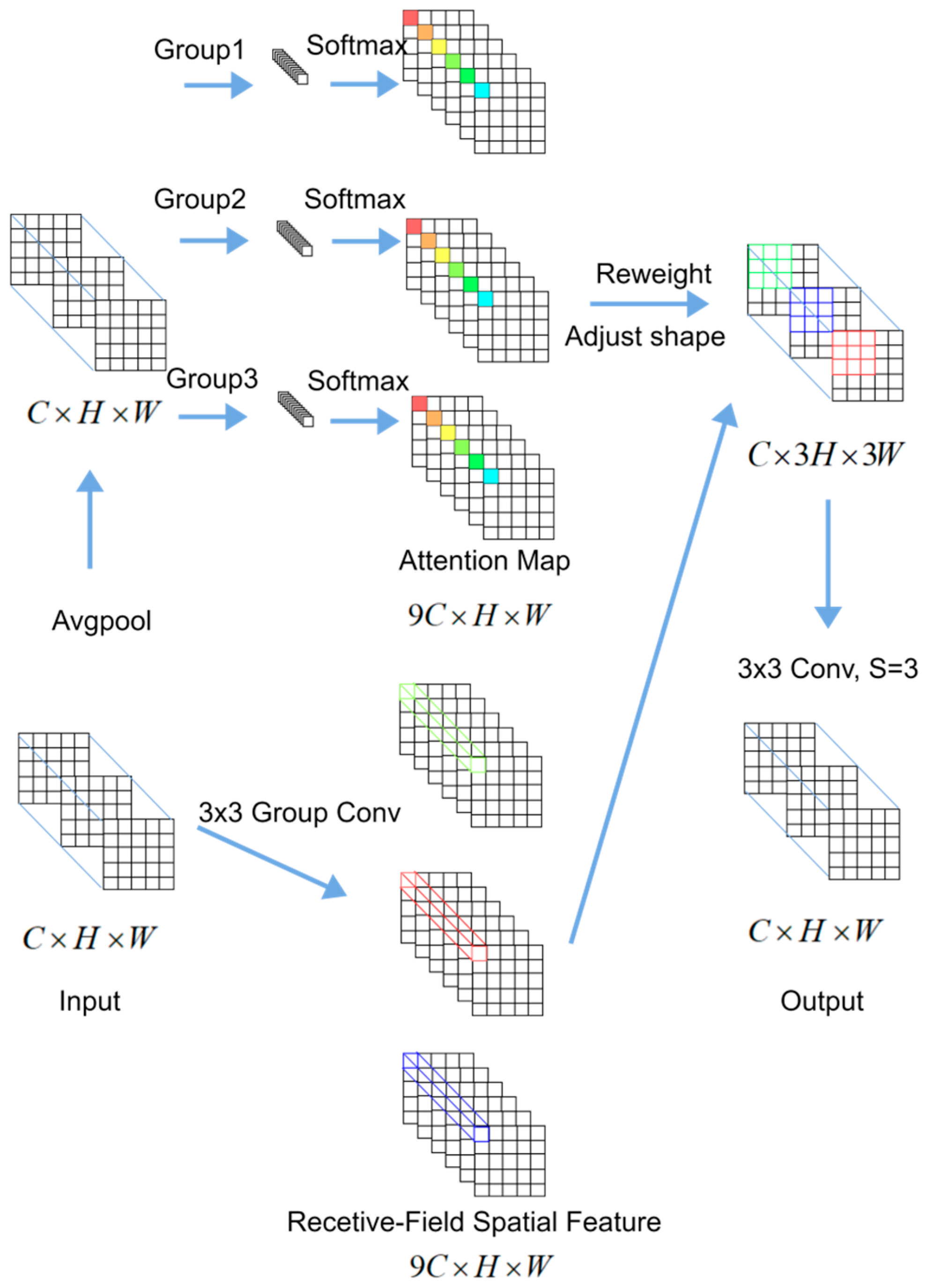

3.2.1. C3K2_RFAConv Module

The C3K2 module contains multiple Bottleneck structures, where the serial connection of these residual modules enables feature extraction and fusion across different scales. However, the limitations of the Bottleneck residual modules are evident in mining environments. Mining scenarios present unique challenges that severely test the capabilities of standard object detection architectures. For instance, in open pit mining operations, targets such as personnel, machinery, and vehicles often blend with complex backgrounds. These backgrounds are characterized by rock faces, shadows, and similar-colored equipment. This challenging condition requires detection models to maintain precise localization capabilities while effectively distinguishing targets from intricate backgrounds.

The limitations of the standard Bottleneck modules in C3K2 become particularly problematic under mining-specific conditions, where targets blend with complex backgrounds characterized by rock faces, shadows, and similar-colored equipment. These modules cause the network to excessively focus on high-frequency positional information within localized regions. Because the standard Bottleneck structure uses fixed convolution operations without adaptive attention, the effective receptive field remains limited to the immediate neighborhood of each position. This limited receptive field results in neglect of surrounding contextual information at each position, potentially causing loss of essential details that are crucial for distinguishing targets from complex backgrounds. Specifically, the standard Bottleneck structure employs fixed convolution operations that treat all positions within the receptive field equally. It lacks adaptive attention mechanisms to prioritize informative spatial locations. This design limitation—the lack of adaptive attention mechanisms to prioritize informative spatial locations—means that when targets are partially blended with backgrounds or when contextual cues are critical for accurate localization, the network cannot effectively focus on the most relevant information. Consequently, the model struggles to capture the subtle distinctions between targets and complex mining backgrounds, leading to degraded localization accuracy and increased false positives.

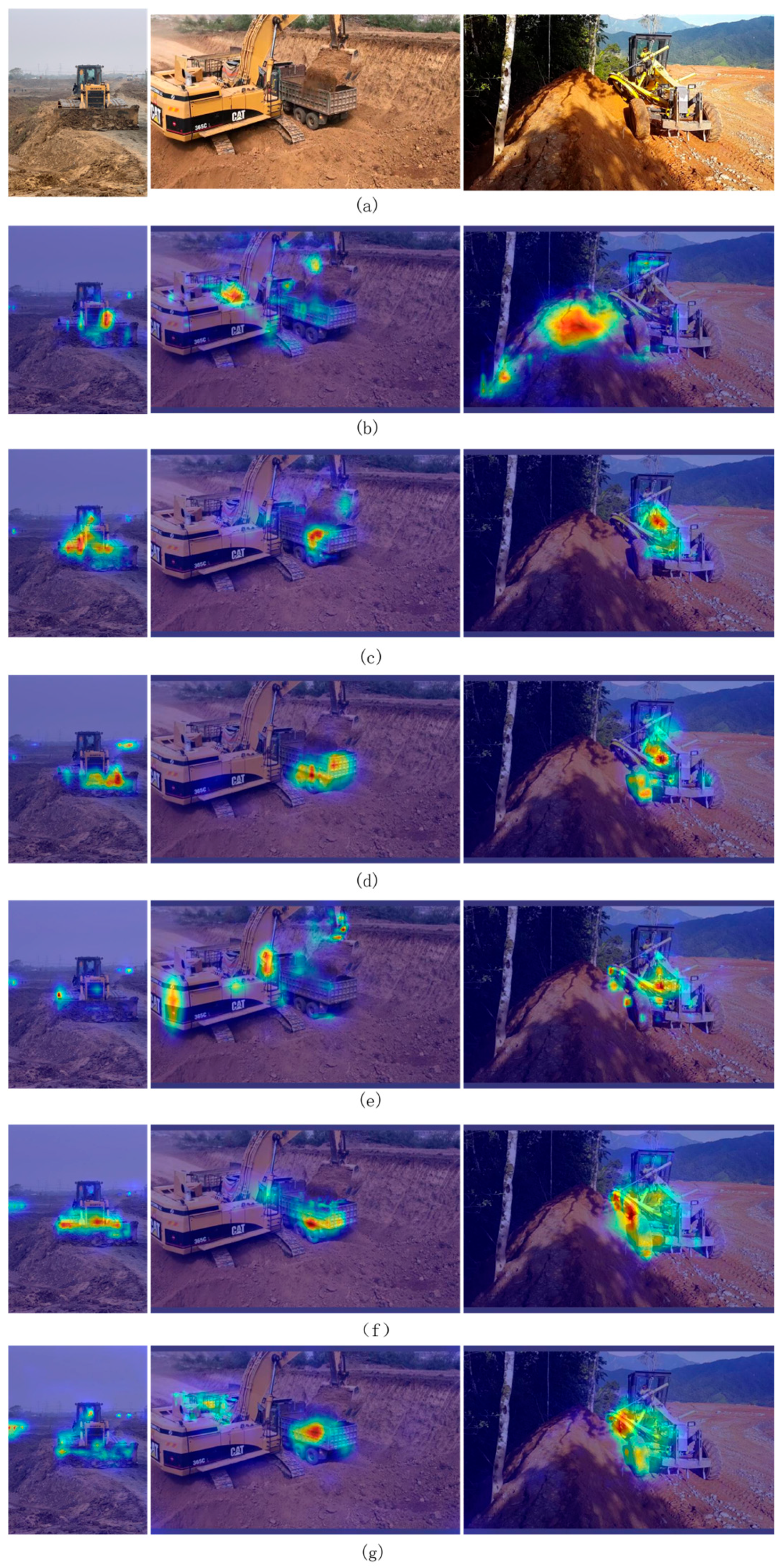

To enhance the detection accuracy of targets in complex mining backgrounds, the RFAConv [

35] module is introduced. This module improves both the backbone network and the C3K2 module in the neck network, as illustrated in

Figure 1b.

Unlike SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation), which operates at the channel level, or CBAM, which sequentially applies channel and spatial attention as separate modules, RFAConv integrates attention directly into the convolution process. Specifically, RFAConv learns position-specific attention weights within each k×k receptive field window before feature aggregation. This enables fine-grained spatial attention—attention that operates at the pixel level within each receptive field window rather than at the channel or global spatial level—that adaptively weights different positions based on their relevance to the target.

This design provides several key advantages for mining detection scenarios. First, the fine-grained spatial attention mechanism allows the model to focus on critical contextual cues at each position rather than treating all positions equally, which is essential when targets blend with rock faces, shadows, and dust. Second, by expanding the effective receptive field while maintaining computational efficiency comparable to standard convolution, RFAConv enables better capture of surrounding contextual information. This information is crucial for distinguishing targets from complex backgrounds. Third, the receptive-field-aware design—which explicitly considers the spatial structure of the receptive field when computing attention weights—provides superior localization capability compared to standard convolution and sequential attention mechanisms. This makes it particularly effective for scenarios where targets are partially blended with backgrounds or where precise boundary localization is critical. These are common challenges in mining environments.

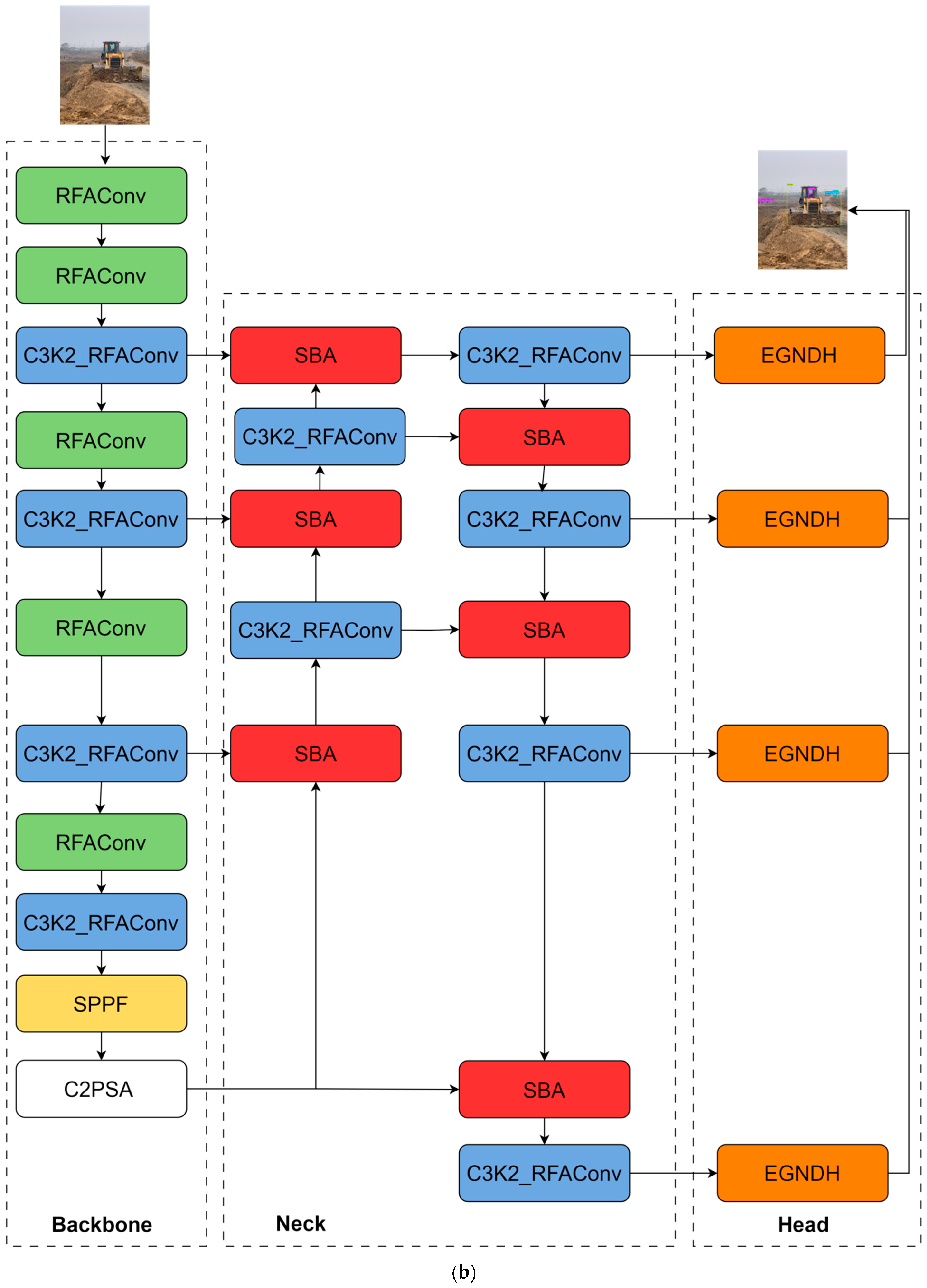

The integration of C3K2_RFAConv into the YOLOv11n architecture is implemented systematically across both the backbone and neck networks, as illustrated in

Figure 1. As

Figure 2b shows, the CBS of standard Bottleneck structures within C3K2 modules is replaced with RFAConv in the backbone and neck networks. The integration strategy of replacing CBS with RFAConv in both backbone and neck networks ensures that the enhanced contextual feature extraction capabilities of RFAConv are consistently applied across both the feature extraction (backbone) and feature fusion (neck) stages. This strengthens the model’s overall capability to distinguish targets from intricate mining backgrounds while maintaining the lightweight characteristics suitable for resource-constrained mining environments.

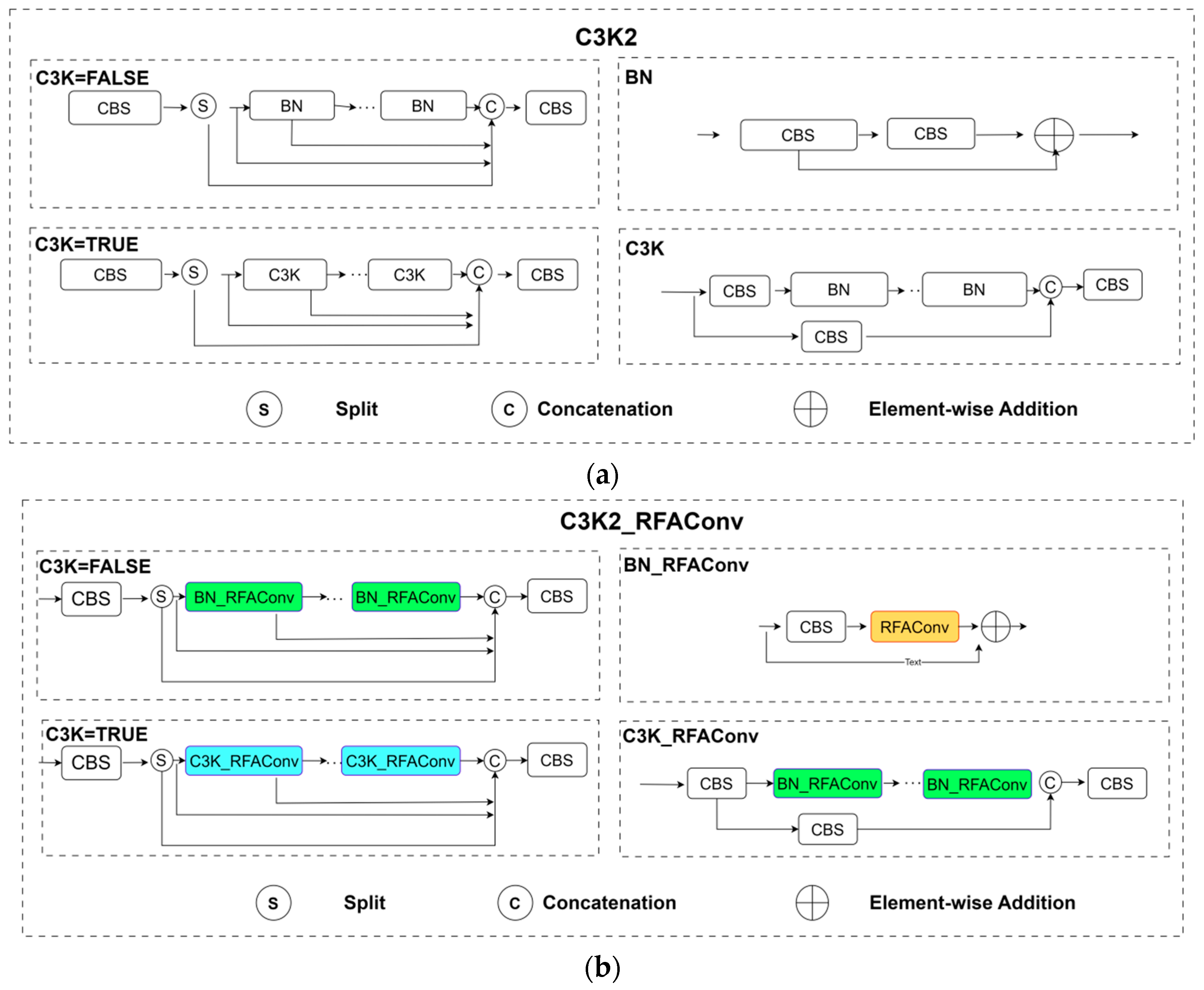

The structure of RFAConv is shown in

Figure 3. RFAConv is calculated as follows:

where

gi×i denotes a grouped convolution with a size of

i ×

i.

k represents the convolution kernel size,

Norm indicates normalization,

X denotes the input feature map, and

F is obtained by multiplying the attention picture

Arf with the transformed receptive field spatial features

Frf.

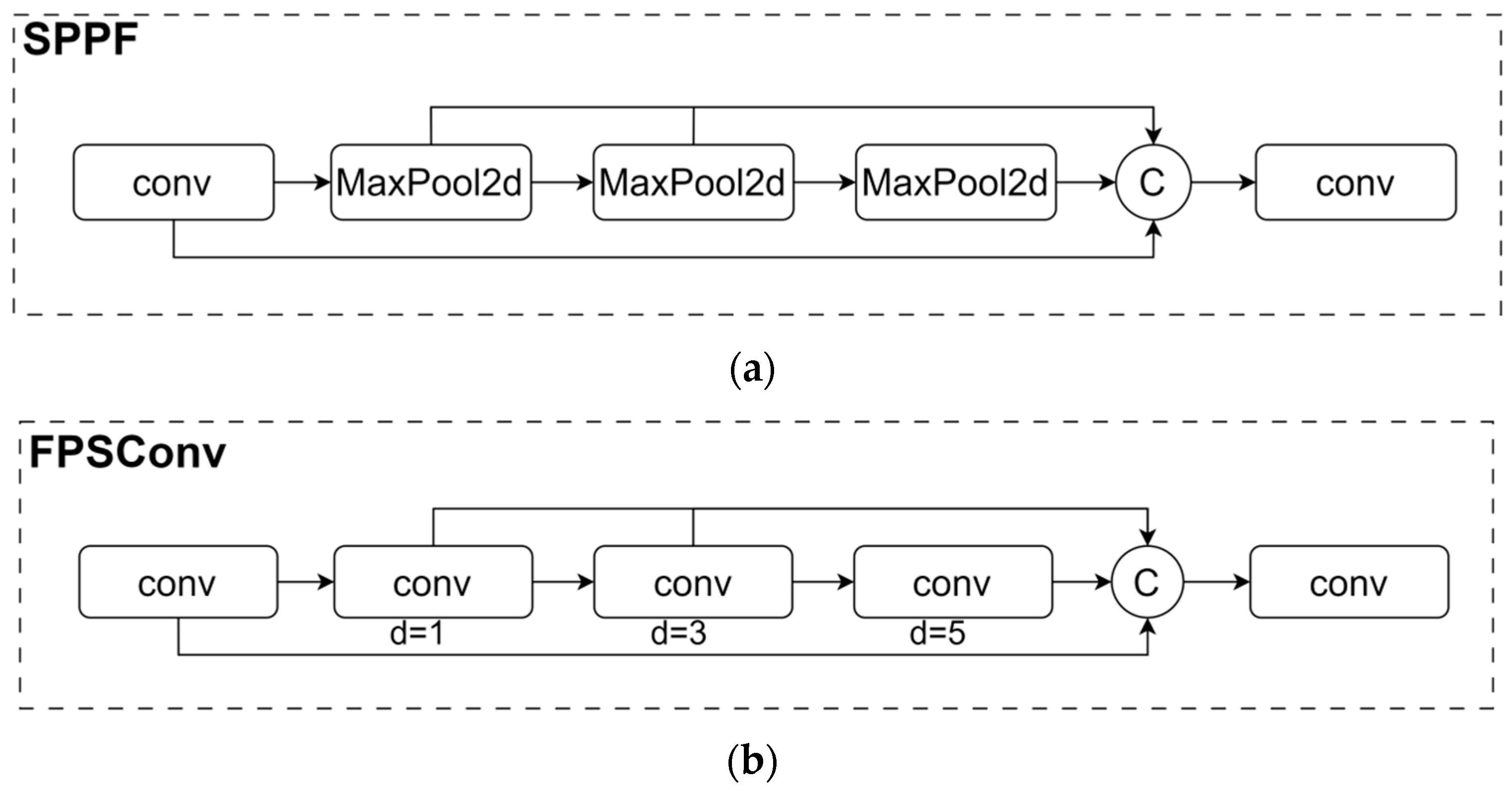

3.2.2. FPSConv Module

SPPF plays a significant role in YOLOv11 by repeatedly using the same max-pooling layer for multiple pooling operations. This reduces computational complexity and accelerates the processing speed while enabling multi-scale feature extraction. However, mining scenarios present unique challenges that expose the fundamental limitations of fixed-window pooling approaches. In open pit mining operations, the detection system must simultaneously handle extreme scale variations. These variations occur between small distant workers (often appearing as only a few pixels) and large engineering vehicles (trucks, excavators) that occupy significant portions of the image. These challenging conditions demand multi-scale feature extraction mechanisms that can adaptively capture both local details and global context while preserving critical spatial information across different scales.

The limitations of SPPF become particularly problematic under these mining-specific conditions. However, as shown in

Figure 4a, the fixed pooling window size and repetition count in SPPF may lead to information loss at certain scales. This is particularly problematic when handling very large or extremely small targets, failing to adequately adapt to all types of input data or application scenarios. Specifically, SPPF’s reliance on fixed-window max pooling operations creates several critical drawbacks. (1) The fixed window size cannot adapt to the diverse scale distribution of mining targets, causing information loss for targets that do not match the predefined pooling scales. (2) Max pooling operations inherently discard detailed spatial information by selecting only the maximum value within each window. This is particularly detrimental for small targets where fine-grained features are essential for accurate detection. (3) The non-learnable nature of pooling operations means that SPPF cannot adapt its feature extraction strategy based on the input content. This makes it unable to prioritize critical regions or adjust to varying target characteristics. The three limitations described above—fixed window size, information loss from max pooling, and non-learnable operations—significantly constrain the algorithm’s performance and practicality when dealing with complex variations and challenging ill-posed regions in mining scenarios. This leads to degraded detection accuracy for both small workers and large vehicles.

To effectively address the aforementioned challenges, we propose the FPSConv module, as illustrated in

Figure 4b. The FPSConv module addresses the limitations of SPPF through several key advantages specifically designed for mining scenarios. First, by employing shared-kernel dilated convolution cascades—where the same convolutional weights are reused with different dilation rates (d = 1, 3, 5) to extract multi-scale features—FPSConv can capture more fine-grained features while preserving detailed spatial information. In contrast, the pooling operations in SPPF may lose some detailed information, which is critical for distinguishing small workers from complex backgrounds or accurately localizing vehicle boundaries. Convolutional operations offer greater flexibility and representational capacity during feature extraction, enabling better capture of image details and complex patterns that are essential for mining safety monitoring. Second, through the use of convolutional layers with different dilation rates (d = 1, 3, 5), the module can extract multi-scale features that adaptively capture information at varying spatial scales. This proves highly advantageous for capturing information of varying sizes and spatial relationships within images. Low dilation rates (d = 1) capture local details crucial for small-target detection, while high dilation rates (d = 5) capture global context necessary for large vehicle recognition. This adaptive multi-scale capability enables FPSConv to effectively handle the extreme scale variations characteristic of mining environments. Third, the use of shared convolutional layers significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters compared to employing independent convolutional layers for each dilation rate. This shared-kernel design can reduce redundancy and improve model efficiency, lowering storage and computational costs while improving computational performance. This parameter efficiency is particularly important for resource-constrained mining equipment where computational resources are limited but high accuracy is required for safety-critical applications. Fourth, unlike SPPF’s fixed and non-learnable pooling operations, FPSConv’s convolutional operations are learnable. This allows the network to adaptively adjust feature extraction strategies based on the input content and learn optimal representations for mining-specific scenarios.

As shown in

Figure 1b, the integration of FPSConv into the YOLOv11n architecture is implemented at a critical location in the backbone network. Specifically, as shown in

Figure 1b, the SPPF module located after Stage 4 of the backbone network is replaced with the FPSConv module. This module follows the final C3K2 module. Placing FPSConv after Stage 4 of the backbone network (following the final C3K2 module) ensures that FPSConv operates on high-level semantic features that have already been processed through the four-stage feature extraction pipeline. This enables it to perform efficient multi-scale refinement on rich semantic representations. The replacement occurs at the final stage of the backbone network, where the feature maps have been downsampled to a resolution suitable for multi-scale feature aggregation. At this location, FPSConv receives feature maps from the C3K2_RFAConv modules and further refines them through adaptive multi-scale convolution. The C3K2_RFAConv modules have already enhanced contextual information through receptive-field-aware attention. The output of FPSConv then feeds into the neck network (ReCa-PAFPN), where the enhanced multi-scale features are fused with features from other stages through the SBA module. This integration strategy ensures that the improved multi-scale feature extraction capabilities of FPSConv complement the receptive-field enhancement provided by C3K2_RFAConv. This creates a synergistic effect that strengthens the model’s overall capability to handle complex mining backgrounds, extreme scale variations, and challenging detection scenarios while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for real-time deployment in mining safety monitoring systems. The FPSConv’s workflow is as follows:

Firstly, the input tensor x undergoes transformation through a convolutional layer, generating a feature map y with halved channel count. This stage reduces the computational complexity for subsequent operations and prepares for multi-scale feature extraction.

In the multi-scale feature extraction phase, shared convolutional weights are employed to perform dilated convolution operations with different dilation rates on these feature maps. Each dilated convolution operation generates a new feature representation, which is incrementally added to the results collection, accumulating feature representations through sequential element-wise addition, where each dilated convolution output is added to the previous sum. This incremental addition strategy enables the model to capture information across multiple scales, enhancing its understanding of multi-scale targets.

During the feature fusion stage, all feature maps from different scales are concatenated along the channel dimension. This step integrates information from various scales, forming a more comprehensive and enriched feature representation. Subsequently, the concatenated feature maps pass through another convolutional layer to adjust to the desired output channel count, ensuring the output format aligns with requirements.

Finally, the feature map obtained after undergoing the aforementioned processing steps constitutes the final output of this process. The entire workflow is designed to optimize feature extraction and fusion, thereby enhancing the model’s capability in target detection and recognition across various scales.

3.3. Improvement of Neck

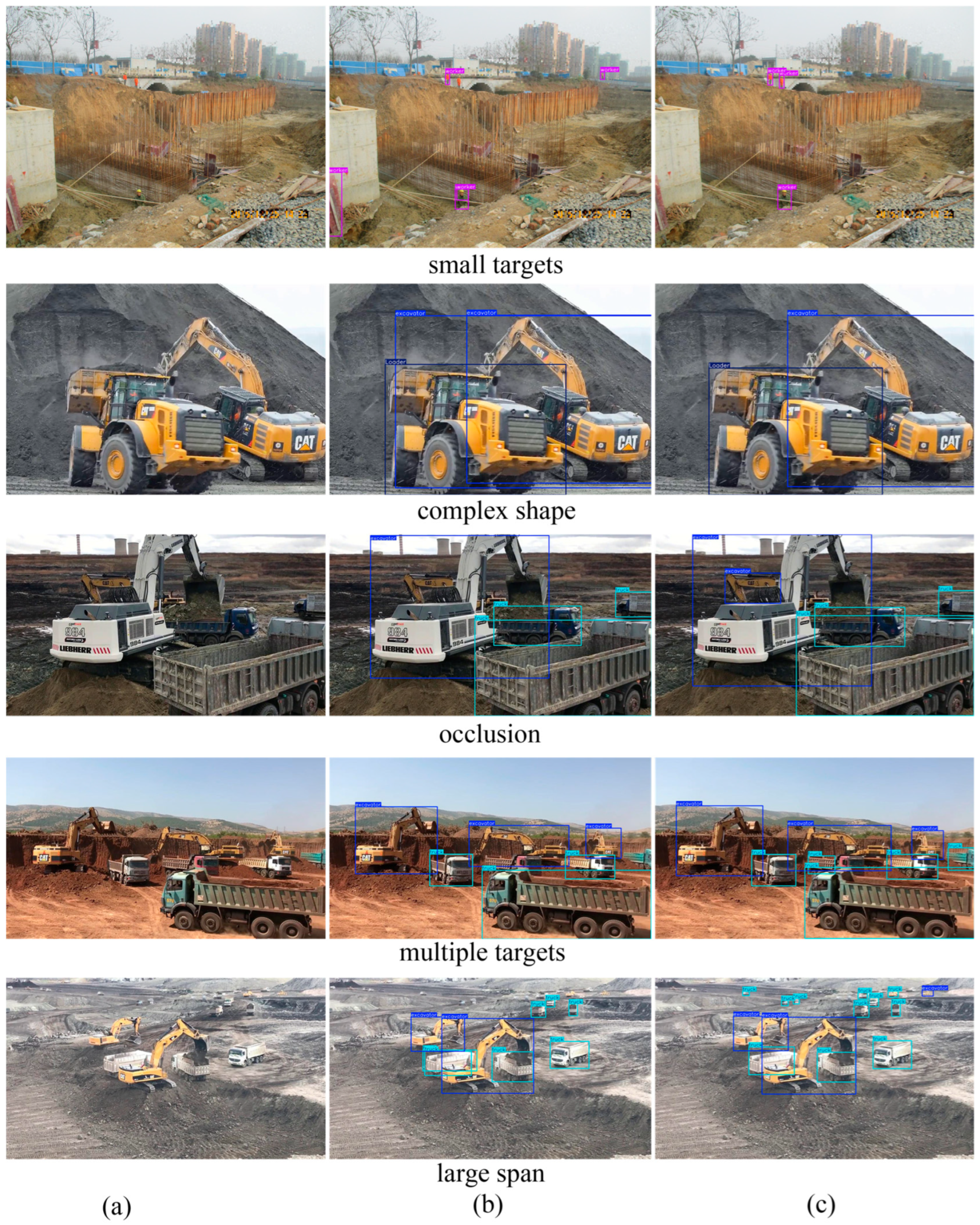

The shallow layers contain less semantic information but are rich in details, exhibiting more distinct boundaries and less distortion. Additionally, deeper layers encapsulate abundant material semantic information. Within the framework of object detection algorithms, the neck network constructs a Path Aggregation Network. It incorporates rich semantic features through feature fusion and multi-scale detection methods, aiming to minimize the loss of semantic feature information. However, mining scenarios present unique challenges that severely test the capabilities of traditional neck network architectures. In open pit mining operations, the neck network must effectively fuse features across extreme scale variations. Small distant workers (often appearing as only a few pixels) coexist with large engineering vehicles (trucks, excavators) that occupy significant portions of the image. Additionally, complex backgrounds characterized by rock faces, shadows, and similar-colored equipment create ambiguous boundaries between targets and backgrounds. This requires the neck network to preserve both fine-grained spatial details from shallow layers and rich semantic information from deep layers. These challenging conditions require neck networks to achieve effective multi-scale feature fusion while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for real-time safety monitoring applications.

However, traditional networks that directly fuse low-resolution and high-resolution features may lead to redundancy and inconsistency, thereby compromising the fusion effectiveness. The limitations of the original YOLOv11n neck network become particularly problematic under these mining-specific conditions. In the task of detecting personnel and vehicles in complex mining environments, the performance of the neck network is often constrained by multiple factors. These factors include interference from intricate backgrounds, diverse object categories, significant scale variations, and challenges with small targets. Specifically, the original YOLOv11n neck network employs a standard PAFPN structure that uses simple Upsample, Conv, and Concat operations for feature fusion. This design creates several critical drawbacks. (1) The direct concatenation or addition of features from different resolutions without adaptive weighting mechanisms leads to redundant information propagation and inconsistent feature representations across scales. This is particularly problematic when fusing shallow high-resolution features (rich in details but less semantic) with deep low-resolution features (rich in semantics but less detailed). (2) The fixed fusion strategy treats all spatial locations and channels equally, without considering the varying importance of different features for different target types (small workers vs. large vehicles). This makes it unable to adaptively emphasize critical information while suppressing background noise. (3) The lack of explicit compensation mechanisms for missing boundary information in high-level features and missing semantic information in low-level features results in incomplete feature representations. This degrades detection accuracy, especially for small targets where both fine-grained boundaries and semantic context are essential. These limitations significantly constrain the algorithm’s performance when dealing with complex mining scenarios characterized by extreme scale variations, ambiguous boundaries, and frequent occlusions.

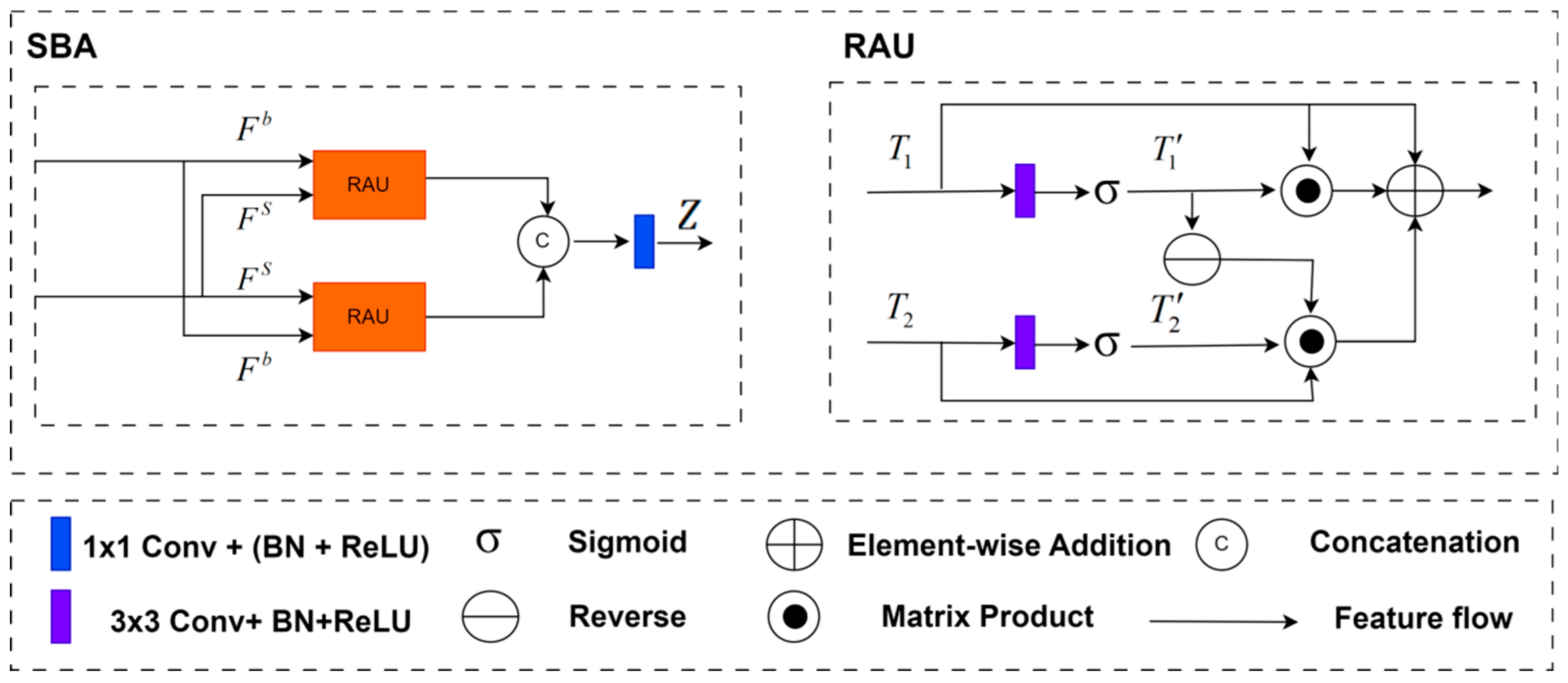

To enhance the detection performance of RSLH-YOLO in mining scenarios, we optimized and refined the neck of the original YOLOv11 and proposed a ReCa-PAFPN structure, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The ReCa-PAFPN structure addresses the aforementioned limitations through several key advantages specifically designed for mining scenarios. First, within the ReCa-PAFPN framework, the Spatial Branch Attention (SBA) module [

36] is introduced as a neural network component designed to handle high- and low-resolution feature maps. This module aims to improve feature fusion capabilities through attention mechanisms. Unlike traditional direct concatenation or addition, SBA learns two complementary gates for shallow and deep features and uses them to recalibrate what information should be exchanged in each direction. This enables adaptive weighting of features based on their relevance to the detection task. This adaptive fusion mechanism allows the network to emphasize critical information while suppressing redundant or noisy features. This is particularly effective for mining scenarios where targets must be distinguished from complex backgrounds. Second, the SBA module implements a bidirectional fusion mechanism between high-resolution and low-resolution features that ensures more thorough information exchange. The RAU (Recalibration and Aggregation Unit) block within SBA explicitly compensates missing boundary information in high-level features and missing semantic information in low-level features before fusion. This compensation is rarely considered in standard pyramid designs. This compensation mechanism ensures that both fine-grained spatial details and rich semantic information are preserved and effectively integrated. This makes SBA particularly effective for mining scenes where small workers and large engineering vehicles coexist and where boundaries between targets and background slopes are often ambiguous. Third, the adaptive attention mechanism dynamically adjusts feature weights based on the varying resolutions and content of feature maps, enabling better capture of multi-scale target characteristics. This attention mechanism assists the model in capturing long-range contextual dependencies, which is particularly critical for detecting small objects and handling occlusions in complex mining environments. Furthermore, ReCa-PAFPN incorporates an additional small-object detection layer (P2 layer) to maximize the detection of small targets and enhance the model’s overall detection accuracy. This additional detection layer operates on high-resolution feature maps, providing dedicated capacity for small-target detection that is essential for worker safety monitoring in mining environments.

As shown in

Figure 1b, the integration of ReCa-PAFPN into the YOLOv11n architecture is implemented as a comprehensive replacement of the original neck network structure. Specifically, the standard PAFPN neck network, which uses Upsample, Conv, Concat, and standard C3K2 modules, is entirely replaced with the ReCa-PAFPN structure. In the top–down path (FPN-like), the original Upsample and Concat operations are replaced with SBA modules. These modules perform adaptive bidirectional fusion between high-level semantic features (from deeper backbone stages) and low-level detailed features (from shallower backbone stages). Each SBA module receives features from two different scales and outputs a refined feature map that combines the strengths of both inputs through learned attention gates. Following each SBA module, the standard C3K2 modules are replaced with C3K2_RFAConv modules, which further enhance the fused features through receptive-field-aware attention. In the bottom–up path (PAN-like), the same replacement strategy is applied. SBA modules replace the original Conv and Concat operations for downsampling and feature fusion, while C3K2_RFAConv modules replace standard C3K2 modules. This comprehensive replacement ensures that all feature fusion operations in the neck network benefit from adaptive attention mechanisms and enhanced contextual feature extraction. Additionally, the ReCa-PAFPN structure extends the original three-scale detection (P3, P4, P5) to four scales by incorporating an additional P2 detection layer. This layer operates on the highest-resolution feature maps (160 × 160) to enhance small-target detection capability. The output feature maps from ReCa-PAFPN at four different scales are then fed into the EGNDH detection head for final predictions. This integration strategy ensures that the improved multi-scale feature fusion capabilities of ReCa-PAFPN work synergistically with the enhanced backbone features (from C3K2_RFAConv and FPSConv) and the lightweight detection head (EGNDH). This creates a coherent pipeline that effectively addresses large-scale variations, wide spatial distribution, and severe occlusions in mining safety monitoring scenarios while maintaining real-time inference capabilities.

As one of the most important parts of the ReCa-PAFPN, the architecture of the SBA module is illustrated in

Figure 5.

Figure 5 illustrates a novel RAU (Recalibrated Attention Unit) block that can adaptively select common representations from two inputs (

Fs,

Fb) before fusion.

Fb and

Fs, which denote the shallow-level and deep-level information, respectively, are fed into two RAU blocks through distinct pathways. This compensates for the missing spatial boundary information in high-level semantic features and the absent semantic information in low-level features. Finally, the outputs of the two RAU blocks are concatenated after a 3 × 3 convolution. This aggregation strategy achieves robust combination of different features and refines the coarse features. The RAU block function

(⋅,⋅) can be expressed as:

Here,

T1,

T2 are the input features. Two linear transformations and sigmoid functions

are applied to the input features to reduce the channel dimensions to the specific channel C and obtain the feature maps

and

. The symbol ⊙ represents Point-wise multiplication.

represents an inverse operation performed by subtracting the feature

, refining the imprecise and coarse estimates into accurate and complete prediction pictures [

36]. We employ convolutional operations with a kernel size of 1 × 1 as the linear transformation process. Therefore, the SBA process can be formulated as:

where C

3×3(·) is a 3 × 3 convolution with batch normalization and ReLU activation.

contains deep semantic information following the third and fourth layers of the fusion encoder, while

represents boundary-rich details extracted from the first layer of the backbone network.

denotes the concatenation operation along the channel dimension.

is the output of the SBA module. The code of SBA as described above can be found in [

36].

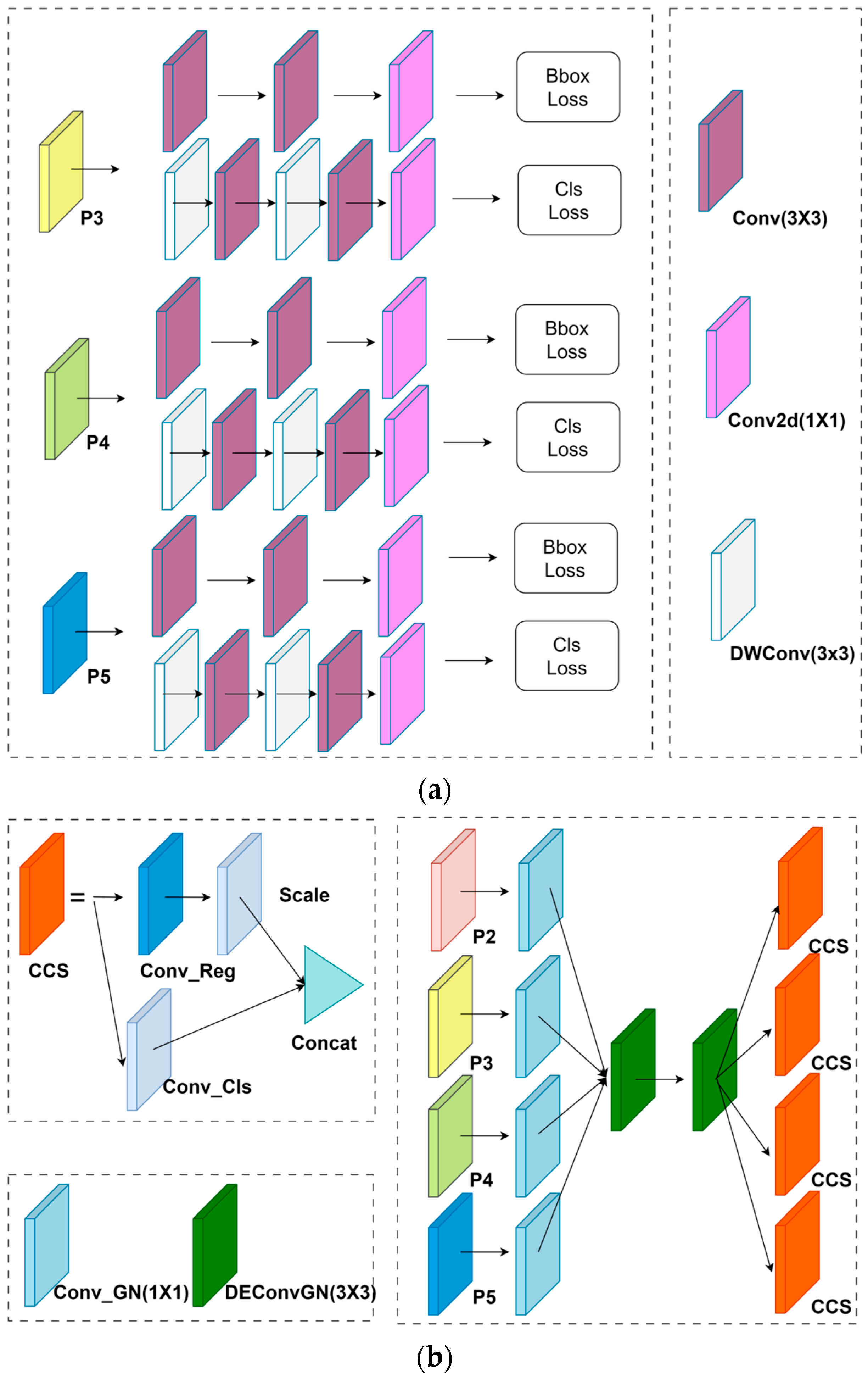

3.4. Improvement of Head

The detection head serves as the final stage of object detection networks, responsible for converting multi-scale feature maps from the backbone and neck networks into precise bounding box coordinates and class predictions. However, mining scenarios present unique challenges that severely test the capabilities of traditional detection head architectures. In open pit mining operations, frequent occlusions among workers, vehicles, and equipment demand robust detection mechanisms. These mechanisms can accurately predict bounding box coordinates and classifications even when partial target information is missing. This challenging condition requires detection heads to achieve high accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for real-time safety monitoring applications in resource-constrained mining environments. GPU memory limitations and batch size constraints are common in these environments.

As shown in

Figure 6a, the original detection head of the YOLOv11 network consists of three convolutional layers and a loss computation component. Each convolutional layer is independently trained with its own parameters. However, this structural design demands significant computational resources. Moreover, in object detection scenarios, input images typically have large dimensions, and due to GPU memory limitations, it is not possible to use batches with a large number of images. Batches with fewer images can lead to unstable calculations of mean and variance, which can adversely affect the model’s lightweight design and accuracy. Additionally, the three convolutional layers operate independently without information sharing, hindering effective acquisition of contextual information. This limitation reduces the model’s ability to handle occlusion scenarios, leading to increased false positives and missed detections. Specifically, the original YOLOv11n detection head architecture exhibits several critical limitations that become particularly problematic under mining-specific conditions. (1) The independent training of three separate convolutional layers with distinct parameters results in significant parameter redundancy and increased computational overhead. This is especially problematic in resource-constrained mining monitoring systems where computational efficiency is crucial. (2) The reliance on Batch Normalization (BN) for feature normalization creates a fundamental dependency on batch statistics (mean and variance), which becomes unstable when batch sizes are small due to GPU memory constraints. In mining detection scenarios, where high-resolution images are necessary to capture small workers and large vehicles simultaneously, batch sizes are often limited to eight or fewer images. This leads to inaccurate batch statistics that degrade both localization and classification performance. (3) The lack of parameter sharing between the three convolutional layers prevents effective information exchange and contextual understanding across different detection scales (P2, P3, P4, P5). This makes it difficult for the network to leverage complementary information from different feature resolutions. This limitation is particularly severe in mining scenarios where targets at different scales (small workers vs. large vehicles) require coordinated detection strategies. (4) The independent operation of convolutional layers without shared contextual information extraction mechanisms hinders the model’s ability to capture long-range dependencies and global scene understanding. These are essential for handling complex occlusions and distinguishing targets from cluttered backgrounds. This results in increased false positives (detecting background elements as targets) and missed detections (failing to detect partially occluded targets), significantly compromising detection accuracy in complex mining environments characterized by frequent occlusions and ambiguous boundaries. These limitations severely compromise detection efficiency and accuracy in resource-constrained environments like mine personnel and vehicle detection, where occlusions are common and computational resources are often limited.

To address these issues, this paper introduces EGNDH (Efficient Group Normalization Detection Head), which primarily consists of convolutional layers, GN (Group Normalization) components, two serially shared convolutional layers, as well as Conv2d modules and scale modules. GN can enhance the model’s localization and classification performance while reducing the dependency on batch size. Furthermore, by sharing convolutional kernel parameters across layers, the model achieves higher accuracy and becomes more lightweight. As shown in

Figure 6b, the EGNDH structure addresses the aforementioned limitations through several key advantages specifically designed for mining scenarios. First, the introduction of Group Normalization (GN) replaces Batch Normalization (BN) as the normalization mechanism, fundamentally eliminating the dependency on batch statistics. Unlike BN, which computes normalization statistics across the batch dimension and becomes unstable with small batch sizes, GN divides channels into groups and computes statistics within each group independently of batch size. This design ensures stable and accurate normalization even when batch sizes are as small as 1. This makes EGNDH particularly suitable for mining detection scenarios where GPU memory constraints limit batch sizes. The stable normalization provided by GN significantly enhances both localization accuracy (precise bounding box prediction) and classification accuracy (correct class prediction). This is especially critical for detecting small workers and distinguishing them from similar background elements. Second, the parameter sharing mechanism implemented through two serially shared convolutional layers dramatically reduces the total parameter count while improving detection performance. Instead of maintaining three independent sets of convolutional parameters (one for each detection scale), EGNDH shares convolutional kernels across all detection scales (P2, P3, P4, P5). This enables the network to learn common feature representations that are beneficial for all scales. This parameter sharing not only reduces the memory footprint and computational cost, making the model more lightweight and suitable for resource-constrained mining monitoring systems, but also facilitates information exchange and knowledge transfer across different scales. This allows the network to leverage complementary information from high-resolution features (for small targets) and low-resolution features (for large targets). Third, the serial architecture of shared convolutional layers creates a progressive feature refinement pipeline, where features from different scales are processed through the same learned transformations, ensuring consistent feature representations across scales. This consistency is particularly important for mining scenarios where the same target types (workers, vehicles) appear at multiple scales, enabling the network to maintain coherent detection strategies. Fourth, the integration of GN with shared convolutions creates a synergistic effect. GN provides stable normalization that enables effective parameter sharing, while shared parameters allow GN to learn more generalizable normalization statistics that benefit all detection scales. The synergistic integration of GN with shared convolutions results in improved detection accuracy, especially for challenging cases such as small targets, occluded objects, and targets with ambiguous boundaries. These are common in mining environments. Furthermore, the lightweight design of EGNDH, achieved through parameter sharing and efficient GN operations, maintains real-time inference capabilities while significantly improving detection performance. This makes it ideal for real-time safety monitoring applications in mining operations. The structure of the EGNDH module is illustrated in

Figure 6.

The integration of EGNDH into the YOLOv11n architecture is implemented as a comprehensive replacement of the original detection head structure. Specifically, the standard YOLOv11n detection head, which consists of three independent convolutional layers (each with its own BN and activation functions) operating separately on features from different scales, is entirely replaced with the EGNDH structure. In the EGNDH architecture, feature maps extracted from the Backbone and Neck components (labeled as P2, P3, P4, and P5) are first processed through scale-specific GN-convolution layers. These initial layers perform scale-specific feature extraction and normalization using Group Normalization, which ensures stable normalization regardless of batch size. The processed features from all scales are then fed into two serially connected shared convolutional layers, which apply the same learned transformations to features from all scales. This shared processing enables parameter sharing across scales, dramatically reducing the total parameter count while facilitating information exchange between different feature resolutions. The outputs from the shared convolutional layers are then divided into two parallel branches: the bounding box prediction branch and the classification prediction branch. For the training task, inputs are features at different scales. For each scale, GN-convolution layers specific to that scale are utilized to extract and normalize the input feature maps. The processed results are then further refined through the shared convolutional layers, effectively reducing the parameter count and improving computational efficiency. Finally, the outputs from the shared convolutional processing are fed into the bounding box prediction branch and classification prediction branch, which are concatenated along the channel dimension. For the inference task, the same architecture is used but optimized for real-time performance. The integration of EGNDH ensures that the improved normalization stability (through GN) and parameter efficiency (through shared convolutions) work synergistically with the enhanced backbone features (from C3K2_RFAConv and FPSConv) and the improved neck network (ReCa-PAFPN). This creates a coherent pipeline that effectively addresses large-scale variations, wide spatial distribution, severe occlusions, and resource constraints in mining safety monitoring scenarios while maintaining real-time inference capabilities. The lightweight design of EGNDH, combined with its stable normalization and parameter sharing mechanisms, makes it particularly suitable for deployment in resource-constrained mining monitoring systems where computational efficiency and detection accuracy must be balanced.

The theoretical calculation of EGNDH (Efficient Group Normalization Detection Head), implemented as a Lightweight Shared Detail-Enhanced Convolutional Detection Head, can be aligned with the following computation steps.

Assume the neck outputs four feature maps with shapes . All scales are first lifted to a unified hidden dimension by per-scale stem convolutions and then processed by shared detail-enhanced convolutions and prediction heads.

For each scale

, the stem block uses a 1 × 1 convolution, followed by Group Normalization with a fixed number of groups (G = 16) and a SiLU activation:

where

denotes GroupNorm with 16 groups. This operation costs approximately

FLOPs per scale.

The intermediate features

from all scales are then passed through a shared sequence of two detail-enhanced convolution blocks, each consisting of a 3 × 3 transposed convolution (stride 1), followed by GroupNorm (G = 16) and a nonlinear activation. For each scale

:

where the spatial resolution is preserved and the channel dimension remains

. Each 3 × 3 shared block contributes roughly

FLOPs, but the weights are shared across all four scales, so parameters do not grow with the number of levels.

For each scale

, the refined feature

is fed into two 1 × 1 convolutional heads that are shared across spatial locations but separate for regression and classification:

where

reg_max is the number of bins for distributional box regression, and

is the number of classes. Thus

and

. The Scale_s layer is a learnable scalar parameter applied element-wise to the regression logits on each scale.

At each scale, the regression and classification logits are concatenated along the channel dimension:

During decoding, a Distribution Focal Loss (DFL) layer—which models bounding box coordinates as a probability distribution over discrete bins and converts them to continuous values—converts from logits into 4 continuous offsets, and a distance-to-bbox mapping uses anchors and strides to obtain final bounding boxes. The classification logits are passed through a sigmoid function to yield class probabilities.

Complexity Summary: Across the four scales, the total computational cost of EGNDH can be approximated as

where the first term corresponds to the per-scale stem Conv + GN, the second to the two shared detail-enhanced 3 × 3 convolutions, and the third to the lightweight 1 × 1 prediction heads.