3.1. Equivalent Viscous Damping Ratios

For each building, the equivalent viscous damping ratios were estimated using the ATC-40 and Priestley approaches, resulting in values ranging from approximately 8% to 30%. According to the ATC-40 approaches, the equivalent viscous damping ratios of the old buildings varied between 10% and 24%, while those of the new buildings were between 22% and 30%. In contrast, equivalent viscous damping ratios of the Priestley approach were between 8% and 17% for the old buildings and between 11% and 18% for the new buildings.

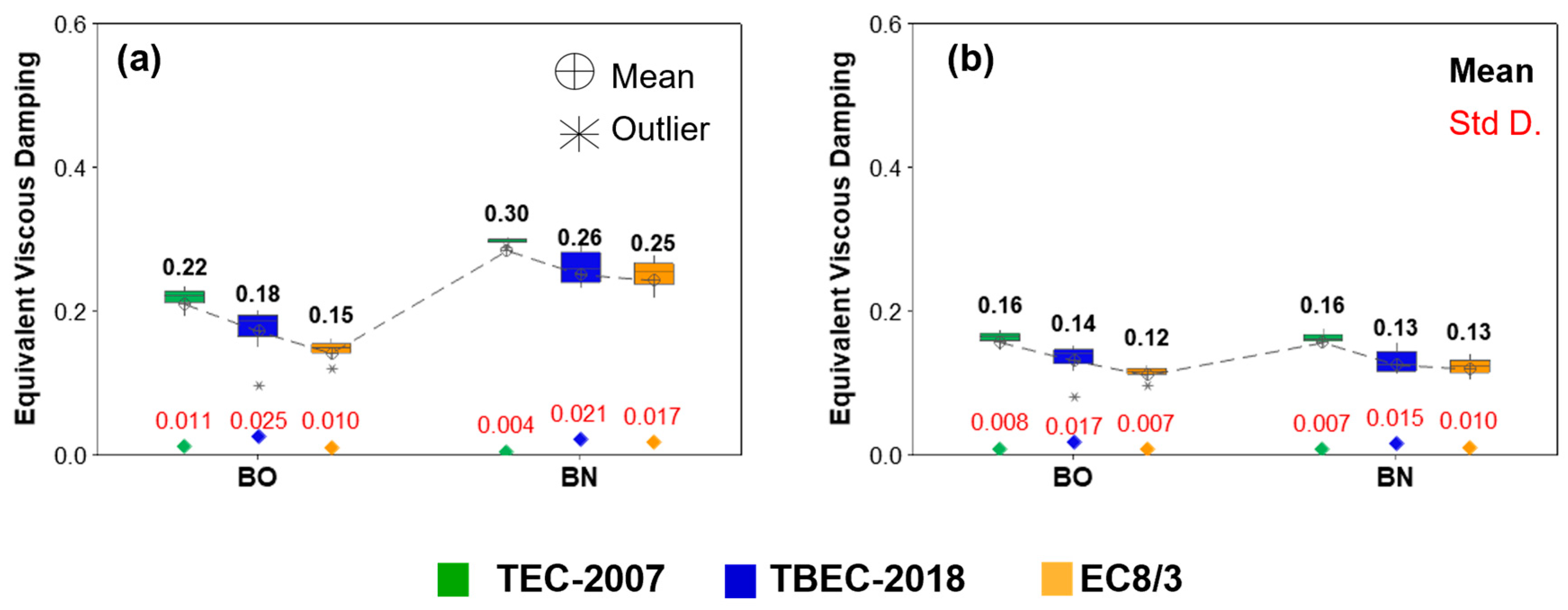

The distribution around the median value of the equivalent viscous damping ratios with respect to the building’s construction year and seismic code is presented in

Figure 10. In the plots, the green, blue, and orange colors correspond to the TEC-2007, TBEC-2018, and EC8 regulations, respectively. The mean value of each distribution is highlighted in bold, while the standard deviation of each dataset is indicated in red.

The results show that equivalent viscous damping ratios obtained using the ATC-40 method differ between old and new buildings. This difference is governed not only by variations in ductility but also by the use of the building type-dependent K coefficient inherent in the ATC-40 formulation. This amplification effect is most pronounced for newer buildings, demonstrating that the ATC-40 formulation is more sensitive to structural classification than to ductility alone. In contrast, damping ratios calculated using the Priestley method are unaffected by building age.

The ductility values specified in the codes also influenced the damping ratios. Ductility values determined from TEC-2007 are higher than the others, corresponding to the highest damping ratios. For new buildings, the average ductility values obtained for TBEC-2018 and EC8/3 are similar, which has also affected the damping ratios.

Furthermore, it was observed that the average damping values computed according to ATC-40 are higher than those obtained from the Priestley approach. When the ratios of the mean damping values obtained using the ATC-40 approach to those obtained using the Priestley method are examined, it is observed that the ATC-40 approach results in approximately 30% higher damping for older buildings and about 93% higher damping for newer buildings. For both damping approaches, the equivalent damping ratios decrease as the average ductility values decrease.

Overall, these findings indicate that the choice of damping formulation has a direct and non-negligible impact on subsequent spectral reduction and displacement demand calculations.

3.2. Spectral Reduction Factors

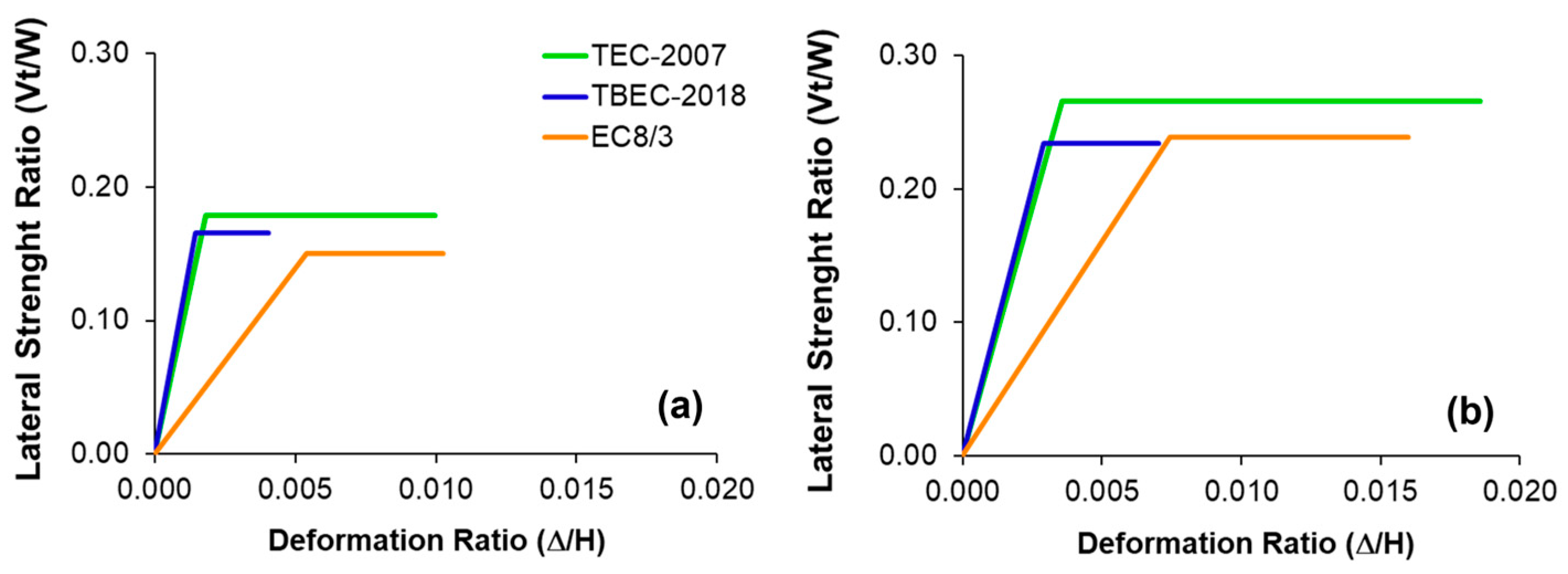

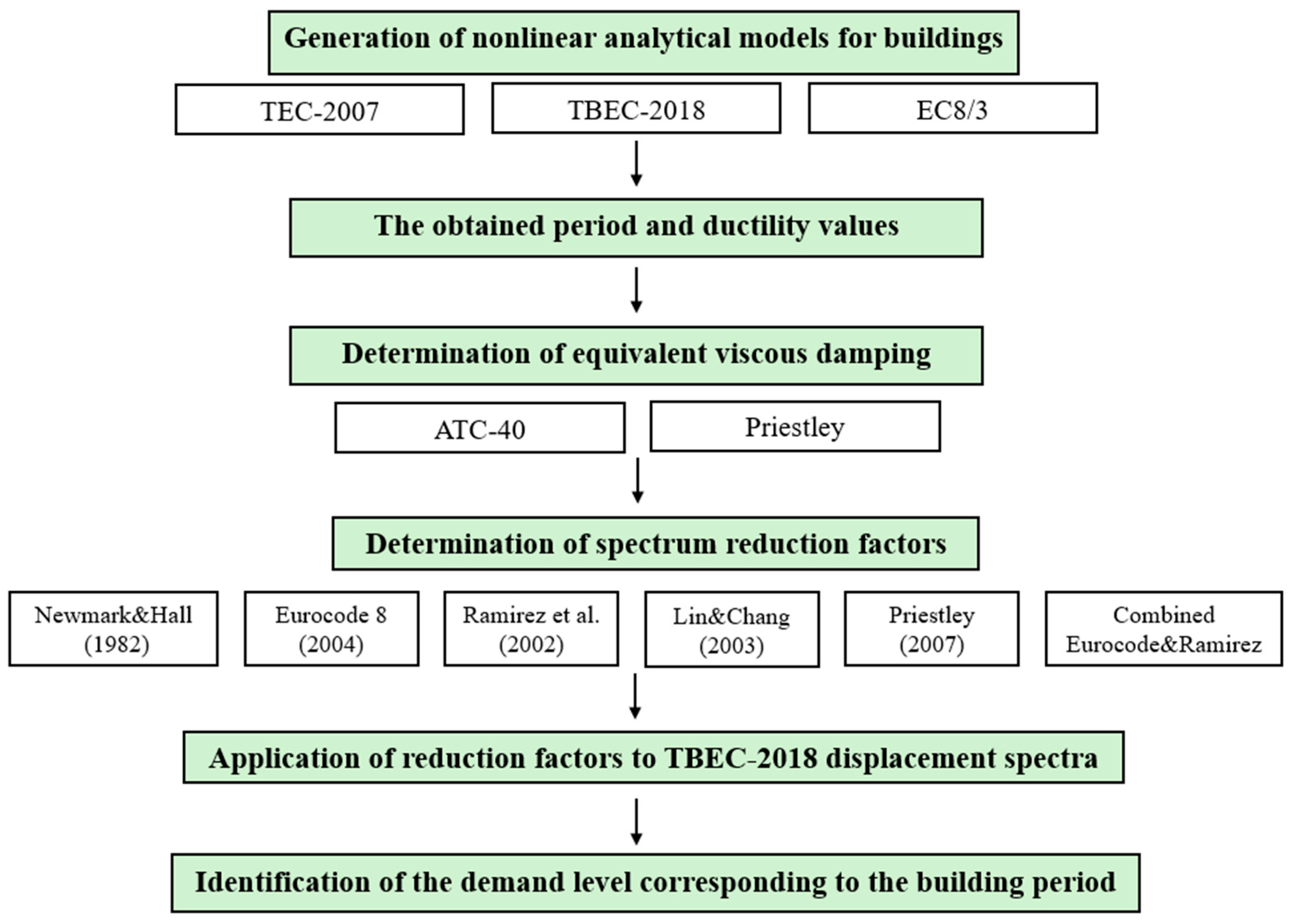

In this section, the displacement demands corresponding to the building periods are examined, considering the effects of the adopted seismic code, soil classification, equivalent viscous damping ratio, and spectral reduction approach.

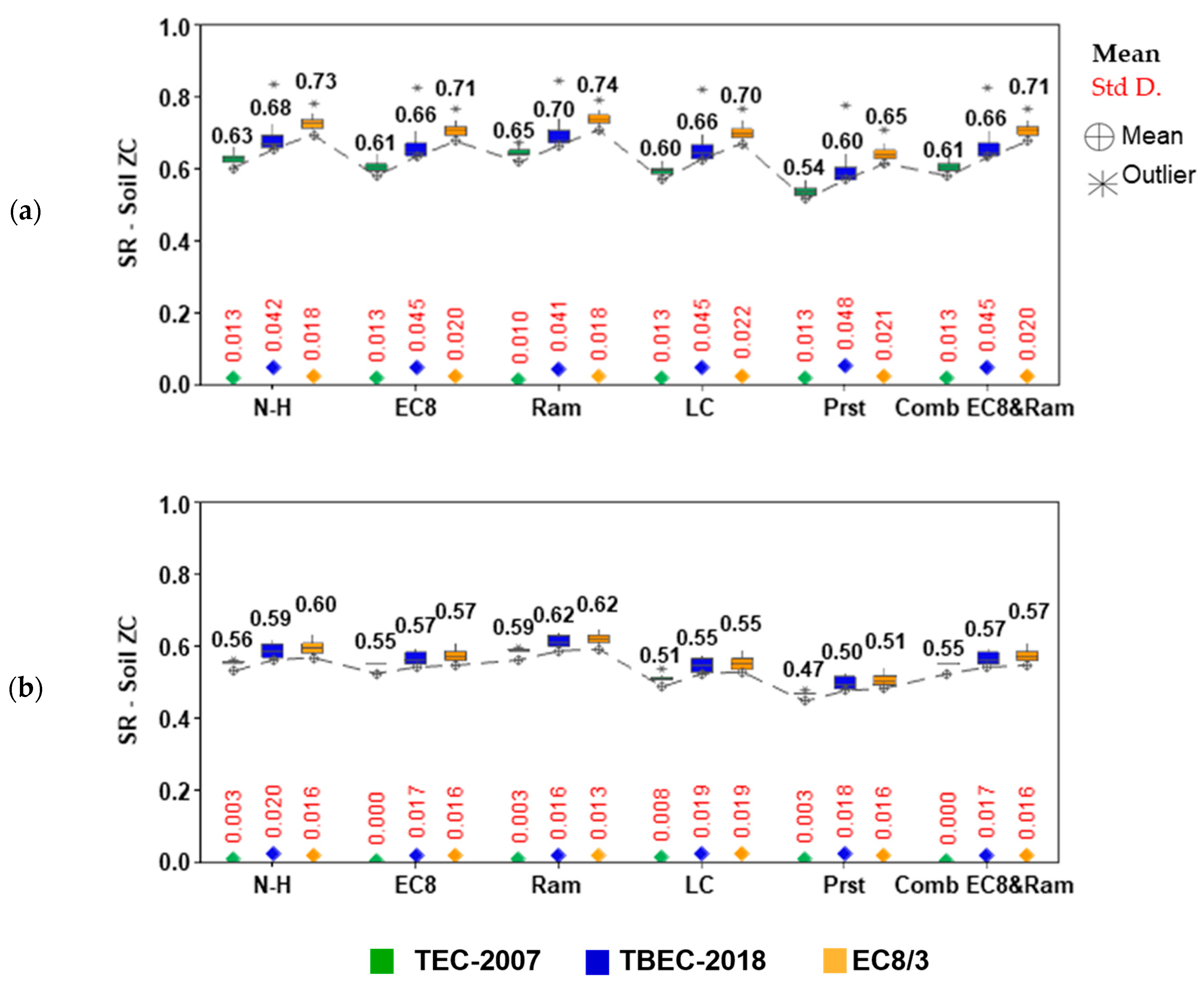

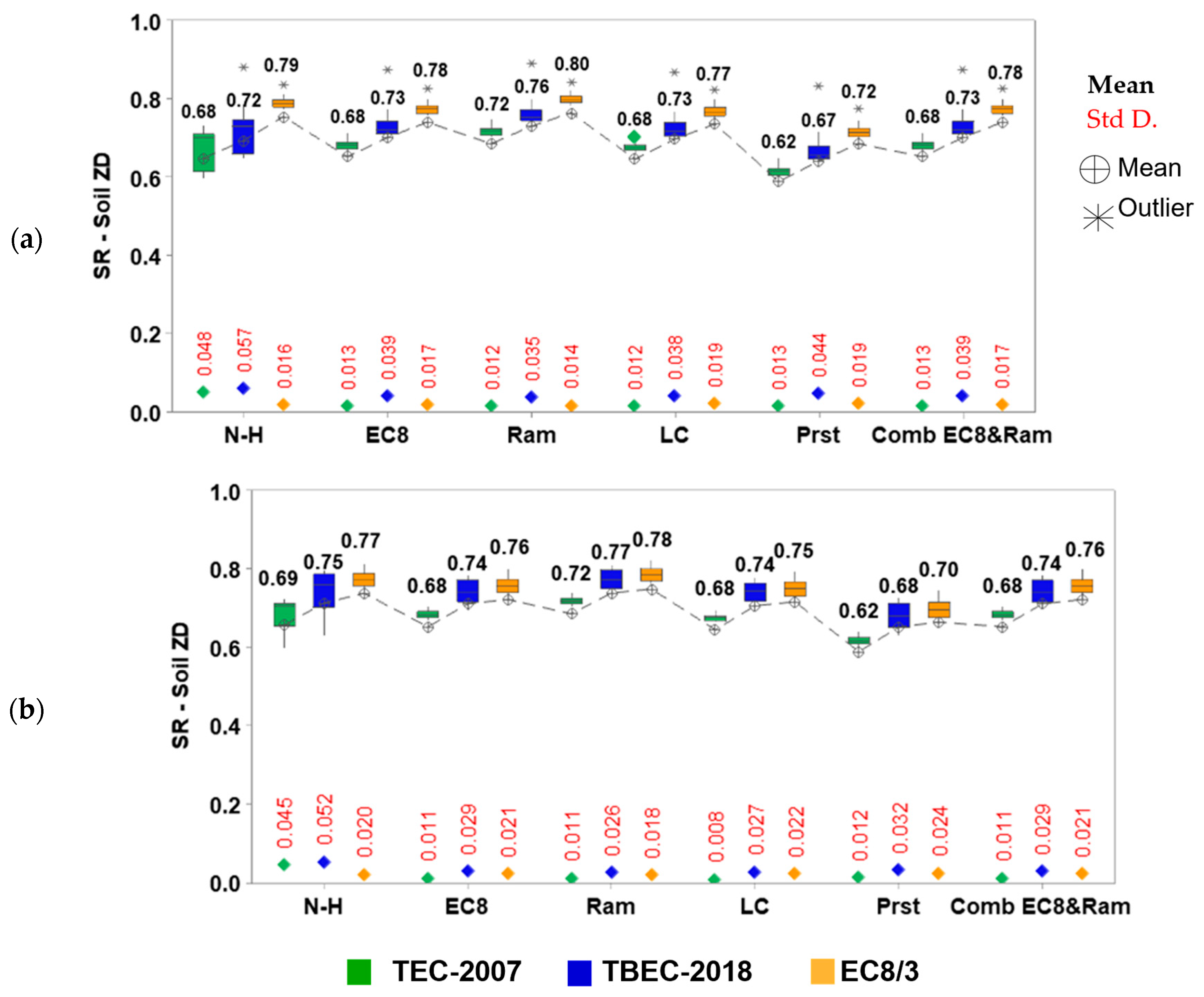

Figure 11 presents the spectral reduction factors (SR) for ZC soils, calculated using the equivalent viscous damping ratios obtained from the ATC-40 method, for both old (on the left) and new (on the right) buildings. Similarly,

Figure 12 shows the results obtained using the Priestley method. The design codes are represented by different colors, with the mean values indicated in bold above the distributions, while the standard deviations are shown in red below the distributions.

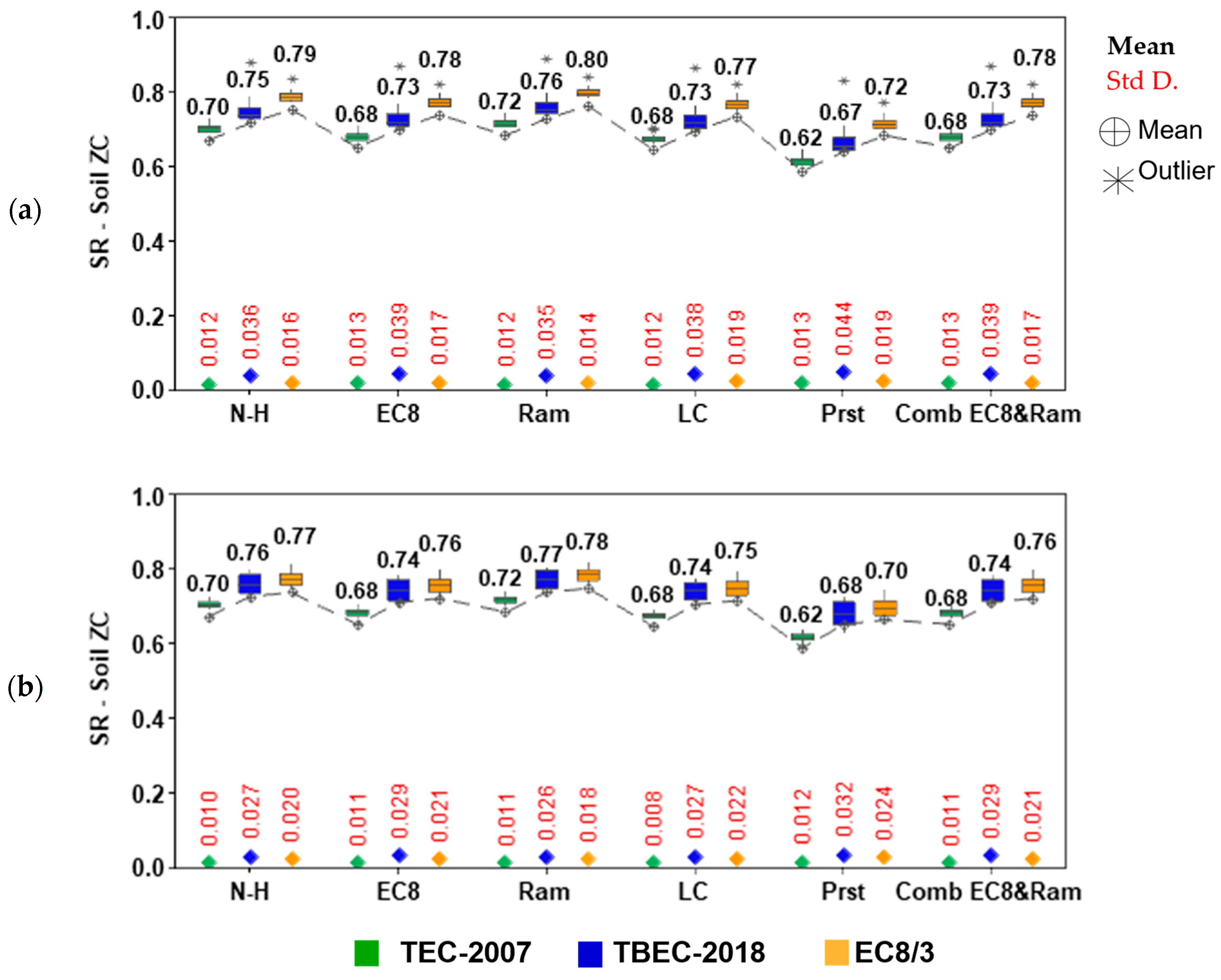

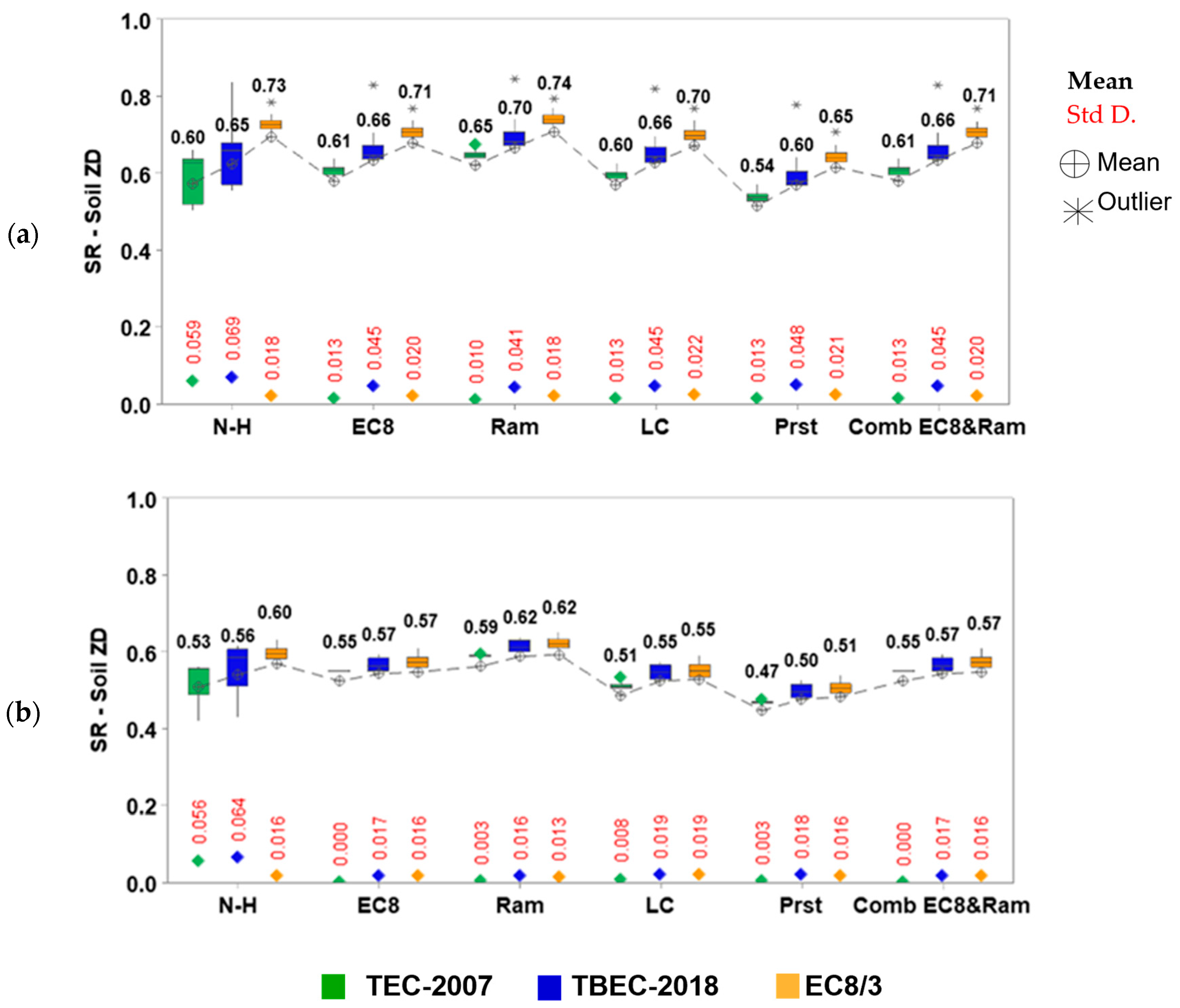

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 illustrate the distribution of the spectral reduction factors obtained for ZD soils.

Structures with higher damping ratios generally exhibit lower spectral reduction factors. While period effects slightly reduce the reduction factors as the building period increases, this influence is minor compared to that of the damping ratio.

Since ATC-40 provides higher equivalent damping ratios than the Priestley method, the corresponding reduction factors from ATC-40 are smaller. This difference is more pronounced for newer buildings, reflecting the sensitivity of the reduction factors to both damping and construction year. Mean of Priestley damping values are approximately 10% larger than those obtained from ATC-40 approach for older buildings across all seismic codes, soil types, and methods. For newer buildings, this difference is approximately 30%.

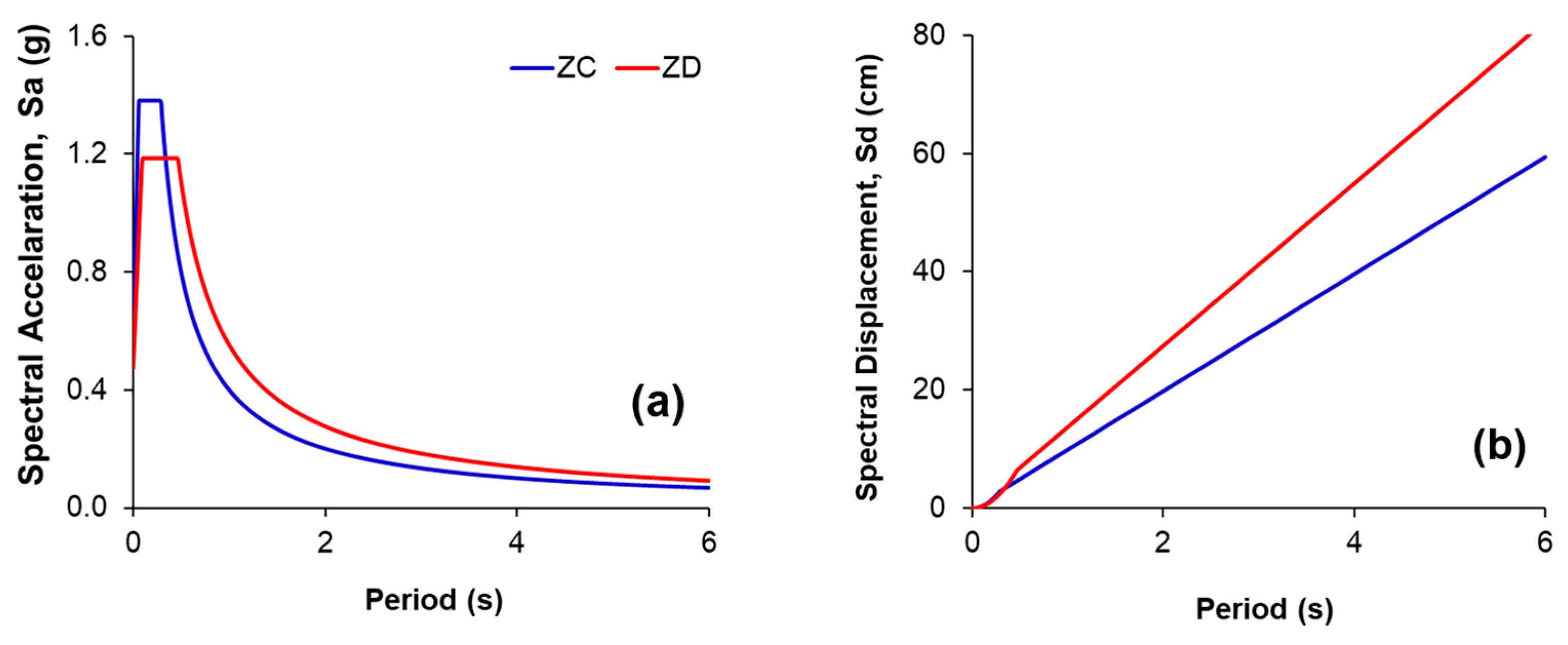

Soil conditions also affect the reduction factors. It can be seen in

Figure 9 that as the soil condition deteriorates, the corner periods increase, and the spectrum generally becomes broader. This leads to variations in the spectral reduction formulations that are defined with respect to these corner periods. In the present study, this effect was particularly evident for the Newmark–Hall approach. When the spectral reduction factors were compared for ATC-40, regardless of the construction year, it was observed that the values for soil class ZD were lower than those for ZC for the Newmark method. Specifically, for ZC soils, the reduction factors were found to be approximately 6% higher for TEC-2007 and TBEC-2018. All periods obtained from EC8/3 fall within the constant-velocity region in both spectra. Consequently, the spectral reduction coefficients for both soil classes are identical. In contrast, for the Priestley method, the reduction factors for ZC soils were, on average, 4% higher than those for ZD. When

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 are examined, the scatter of the distributions obtained for the TEC-2007 and TBEC-2018 regulations is larger on ZD soils. This is due to the larger corner periods.

Across the six evaluated spectral reduction methods, the Ramirez approach consistently produces the highest reduction factors, indicating a more conservative estimate of displacement demands, while the Priestley method gives the lowest values. Meanly, for the same period, the displacement demand obtained using the Ramirez approach is highest. Consequently, performance assessments based on Ramirez are likely to predict more critical performance levels for the same building capacity. The mean reduction coefficients obtained for the methods were evaluated by dividing the mean values of Priestley, and the results were compared. For old buildings, the average reduction coefficient obtained for the Ramirez results using ATC-40 damping was determined to be 17% greater than that of Priestley, regardless of the code. Values obtained for the Priestley damping were 14% greater. For new buildings, these values were 24% and 14%, respectively.

The SR equations vary because they are derived from different earthquake databases, resulting in differences among the formulations. In this study, although the average values are similar, it is observed that the variations differ. These differences naturally arise from the characteristics of the buildings and the methods applied. Additionally, the results are affected by using different equivalent viscous damping approaches, diverse code provisions, and the properties of each building.

The relationship between damping ratios and the ductility values of the codes is evident from the average values. TEC-2007, which has the highest damping ratios, yields the lowest SR factors. A similar trend can be observed for the other codes as well. However, for new buildings, since the ductility values for TBEC-2018 and EC8/3 are closer, the obtained values for these buildings are also quite similar.

The distribution of reduction factors shows greater scatter for TEC-2007 and TBEC-2018 on ZD soils, which is attributed to the larger corner periods in these soil classes. These observations highlight that both the choice of damping model and soil characteristics significantly influence spectral reduction, and hence seismic performance evaluation.

3.3. Spectral Demand

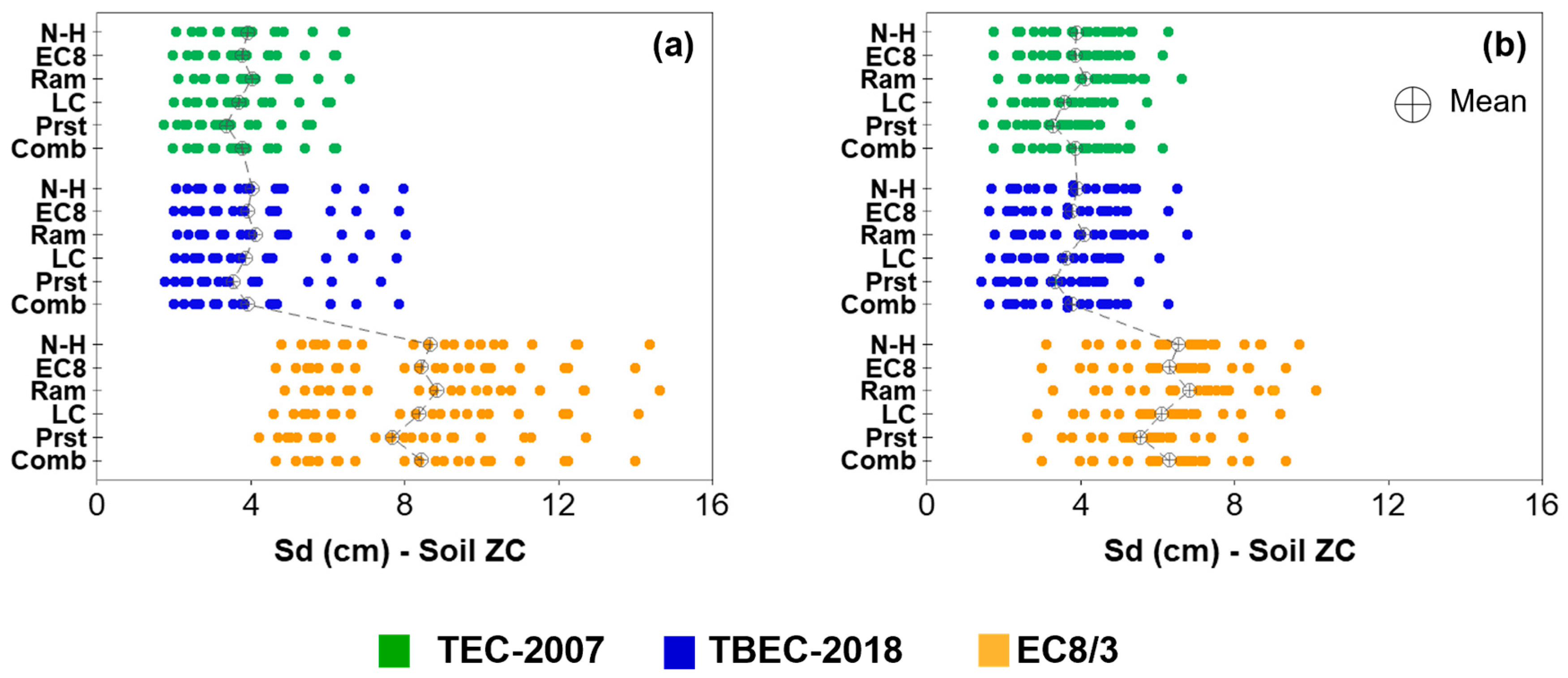

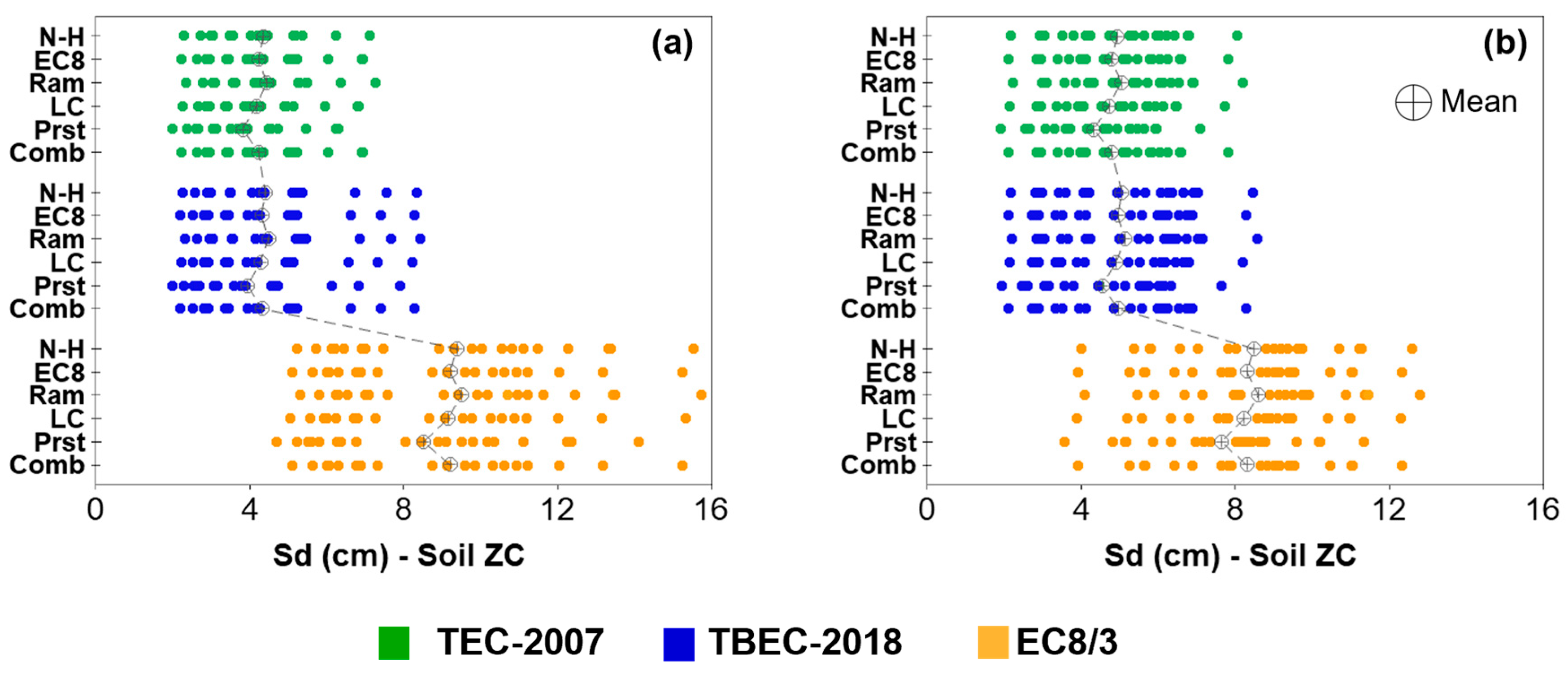

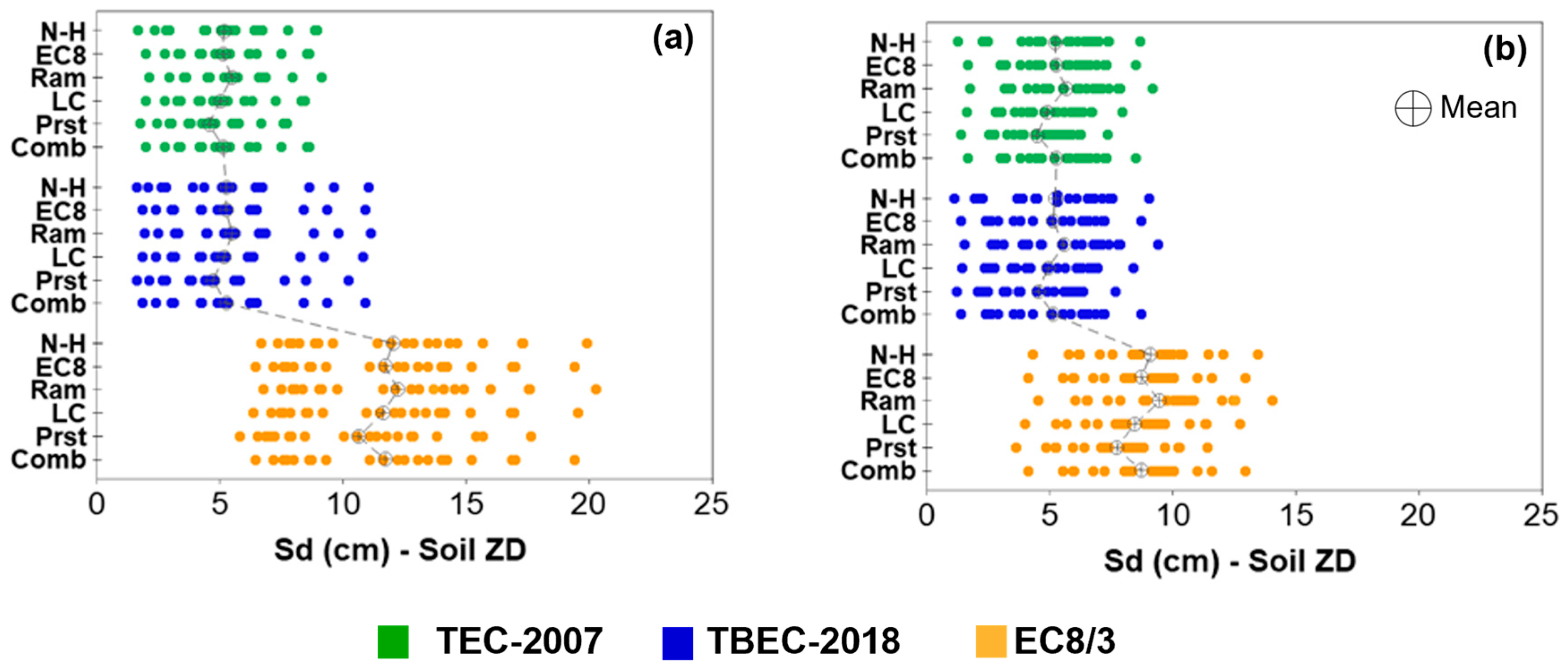

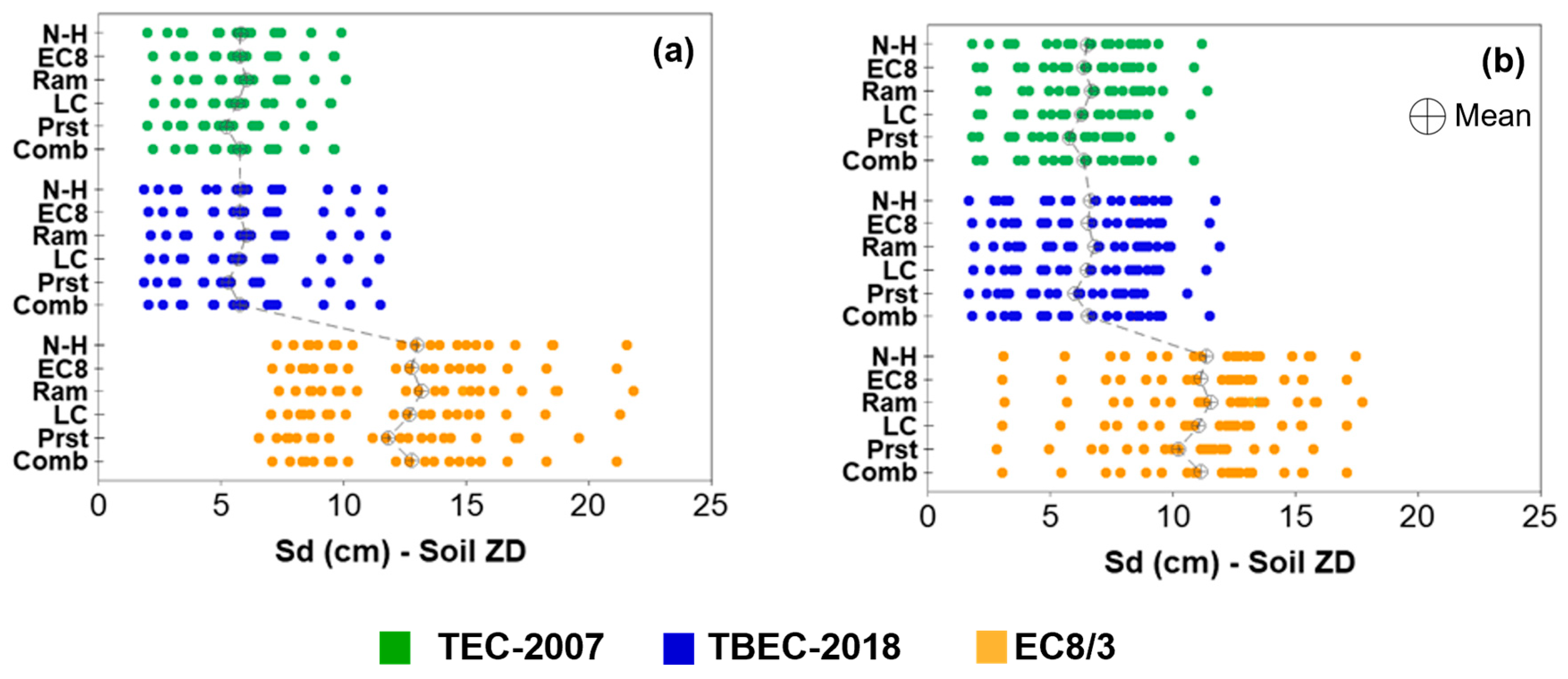

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 below illustrate the distribution of displacement values obtained for each method with respect to their median values. Consistent with the previous sections, the seismic codes are represented using the same colors: green indicates TEC-2007, blue indicates TBEC-2018, and orange indicates EC8/3. The mean value corresponding to each method is represented by a dashed line.

It is known that the SR coefficients obtained according to the codes follow an increasing order of TEC-2007, TBEC-2018, and EC8/3. Accordingly, a similar ranking can be expected for the resulting displacements. Period differences arising from the definitions in the codes have a noticeable effect on the displacements. Examination of the results shows that EC8/3 displacement demands are higher for both soil classes and building age groups. This is mainly due to the effective stiffness coefficients defined in EC8/3, which lead to longer periods and, consequently, larger spectral displacement demands.

The average displacement values obtained using the Priestley method are greater than those obtained with ATC-40. When comparing the results for new and old buildings, it is seen that, according to the ATC-40 method, old buildings have higher displacement demands. In contrast, this is not always the case for the Priestley method.

Comparing across soil classes, ZD soils consistently produce higher displacement demands than ZC. The ratio of the displacement demands obtained for ZD to ZC across all spectrum reduction (SR) methods were examined and comparatively evaluated. For older buildings, the demand for ZD is approximately 27–34% higher than for ZC under TEC-2007 and 25–31% higher under TBEC-2018 when using ATC-40. For newer buildings, ZD soil demands are generally 28–35% higher than ZC, depending on the code and damping method. Similar trends are observed with both old and new buildings, with EC8/3 periods showing nearly 39% higher demands for ZD soils.

For ZC soils, the Priestley method consistently produces the lowest displacement demands, while the Ramirez method yields the highest, regardless of building year or code. To highlight these differences, displacement demands from other methods were normalized with respect to the Priestley results (

Table 1 and

Table 2). When building periods were determined according to Turkish codes, ATC-40 damping led to average displacement demands 10–20% higher than Priestley for older buildings, and slightly lower differences for newer buildings. For EC8/3 periods, other methods gave 9–15% higher than the Priestley method. When equivalent damping was computed using the Priestley approach, these differences were further reduced, indicating that the choice of damping model has a significant effect on the estimated demands, especially for newer buildings with shorter periods. Overall, these results confirm that both the method for calculating spectral reduction and the choice of damping model substantially influence the predicted displacement demands, with the Ramirez method providing the most conservative estimates and Priestley the least.

For ZD soil and older buildings using ATC-40 damping, TEC-2007 periods result in demands roughly 10–20% higher than Priestley, TBEC-2018 periods 9–17% higher, and EC8/3 periods 9–15% higher. Using Priestley damping, these differences are slightly smaller. For newer buildings, ATC-40-based differences increase, reaching 26% for TEC-2007, while using Priestley damping, the differences remain moderate. These results confirm that both the choice of spectral reduction method and soil class have a substantial effect on predicted displacement demands. The Ramirez method consistently provides conservative estimates, while Priestley yields the lowest demands, and soil class differences can amplify displacements by up to 40%.

In this study, building performance levels (Immediate Occupancy—IO, Life Safety—LS, and Collapse Prevention—CP) were determined based on the obtained member damage limits. In the Turkish seismic codes, performance limits of buildings are defined in terms of the number of member damages for each direction. In contrast, EC8/3 does not provide such definitions; therefore, certain assumptions were made to establish performance limits under EC8/3. Accordingly, the CP level was adopted following the approach in the Turkish codes, the IO level was assumed equal to the yield displacement obtained from bilinearization, and the LS level was defined as 75% of the collapse, similar with the damage limit definitions. Using demand values obtained from different SR methods, the performance levels for each building direction were evaluated. The numerical distributions of these performance levels with respect to codes, SR methods, and soil types are presented in

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8.

The obtained performance limits are influenced by the characteristics of the buildings and the provisions of the codes. Accordingly, the highest displacement capacities belong to TEC-2007 buildings, while the lowest capacities correspond to TBEC-2018 buildings. Although the displacement values obtained for the methods are similar, building performance varies depending on the capacity. The results largely confirm that buildings reach collapse according to the Ramirez method. As expected, the number of damages at higher damage states (LS and CP) is observed for ZD. Additionally, the number of buildings reaching collapse is lower for new buildings since these buildings are more ductile. The use of different damping ratios also affects building performance. The results indicate that building performance varies depending on the applied reduction factor method and damping method.

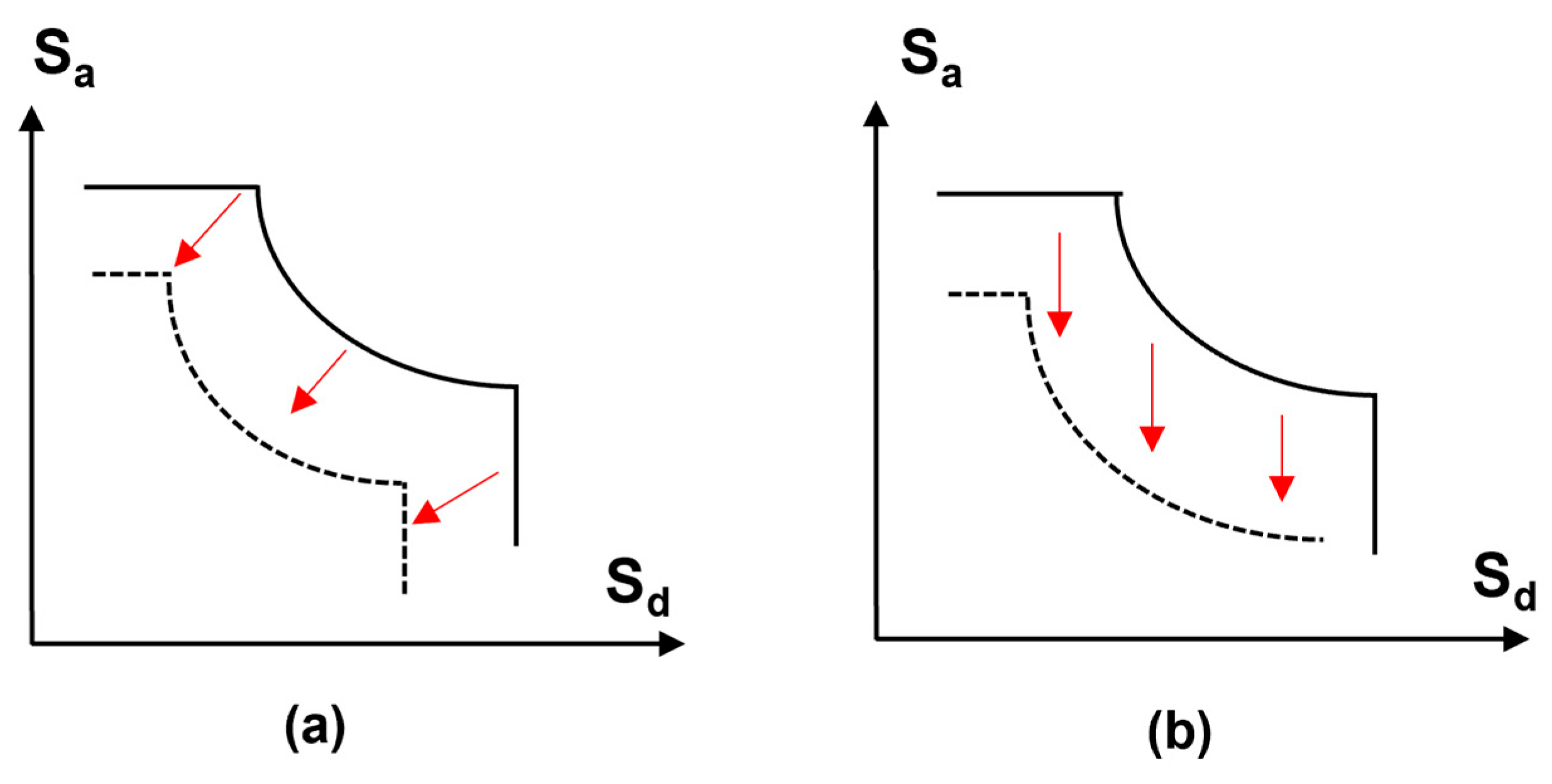

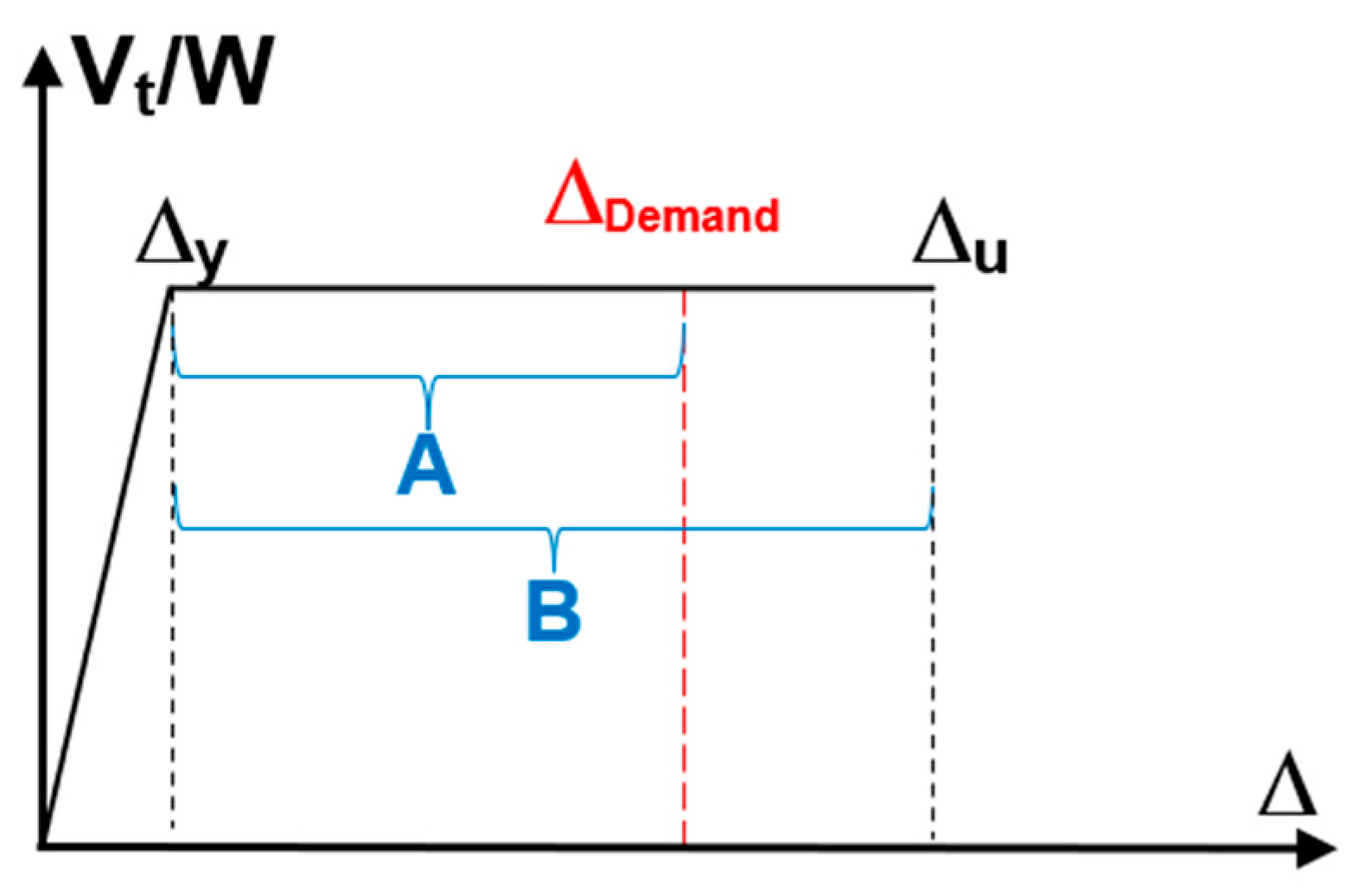

To investigate the influence of different spectral reduction factors on structural performance, the plastic ductility capacities (sketched as “B” in

Figure 19) of the buildings were obtained from the capacity curves. Subsequently, plastic ductility demands (sketched as “A” in

Figure 19) were calculated by subtracting the yield displacement of the structure from the displacement demands. The ratio of the plastic ductility demand to the plastic ductility capacity was then evaluated, as shown in

Figure 19 (Pl

Ratio= A/B). If this ratio is equal to or greater than 1.0, the building is considered to be at the collapse performance level; otherwise, the collapse limit state is not exceeded.

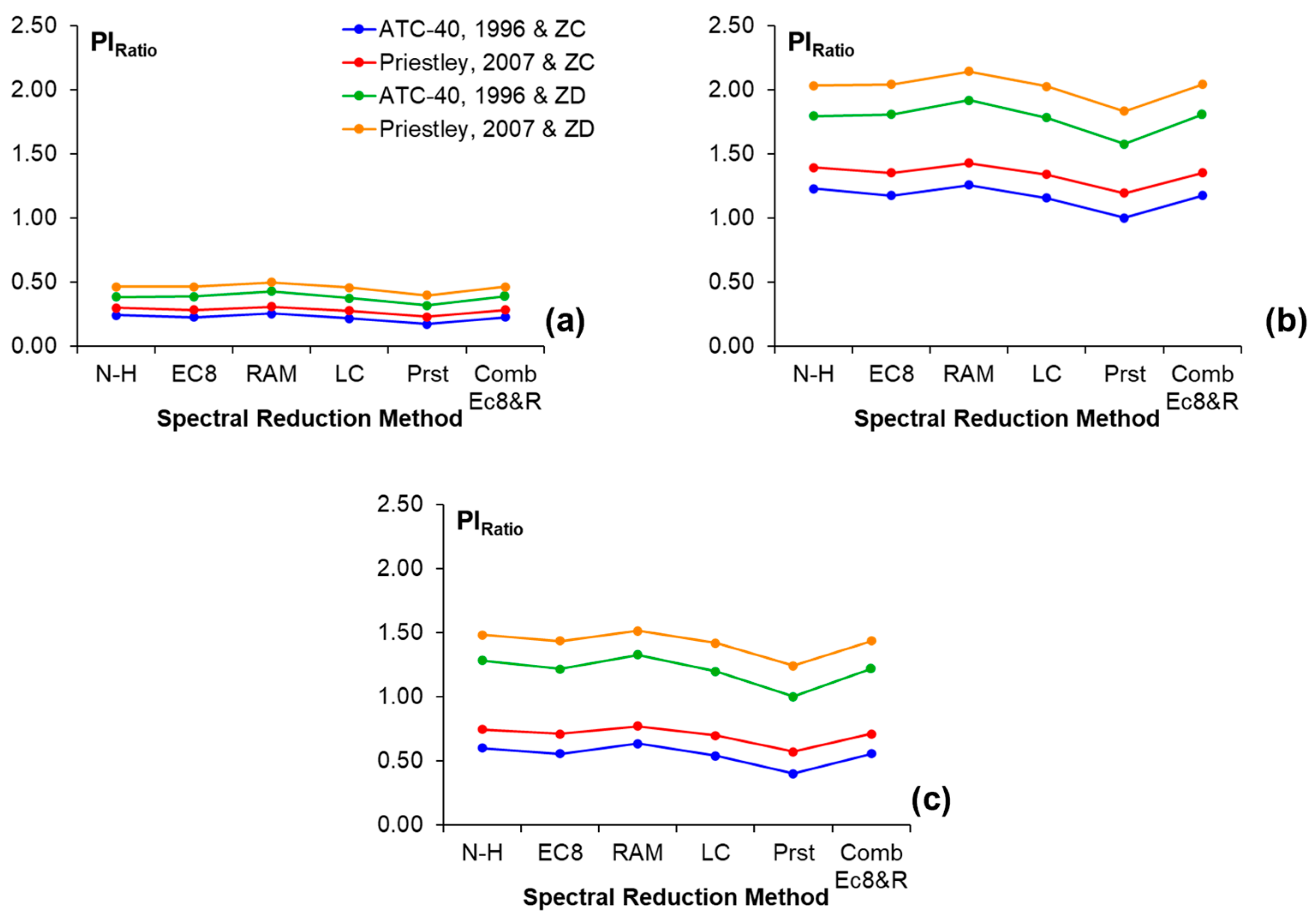

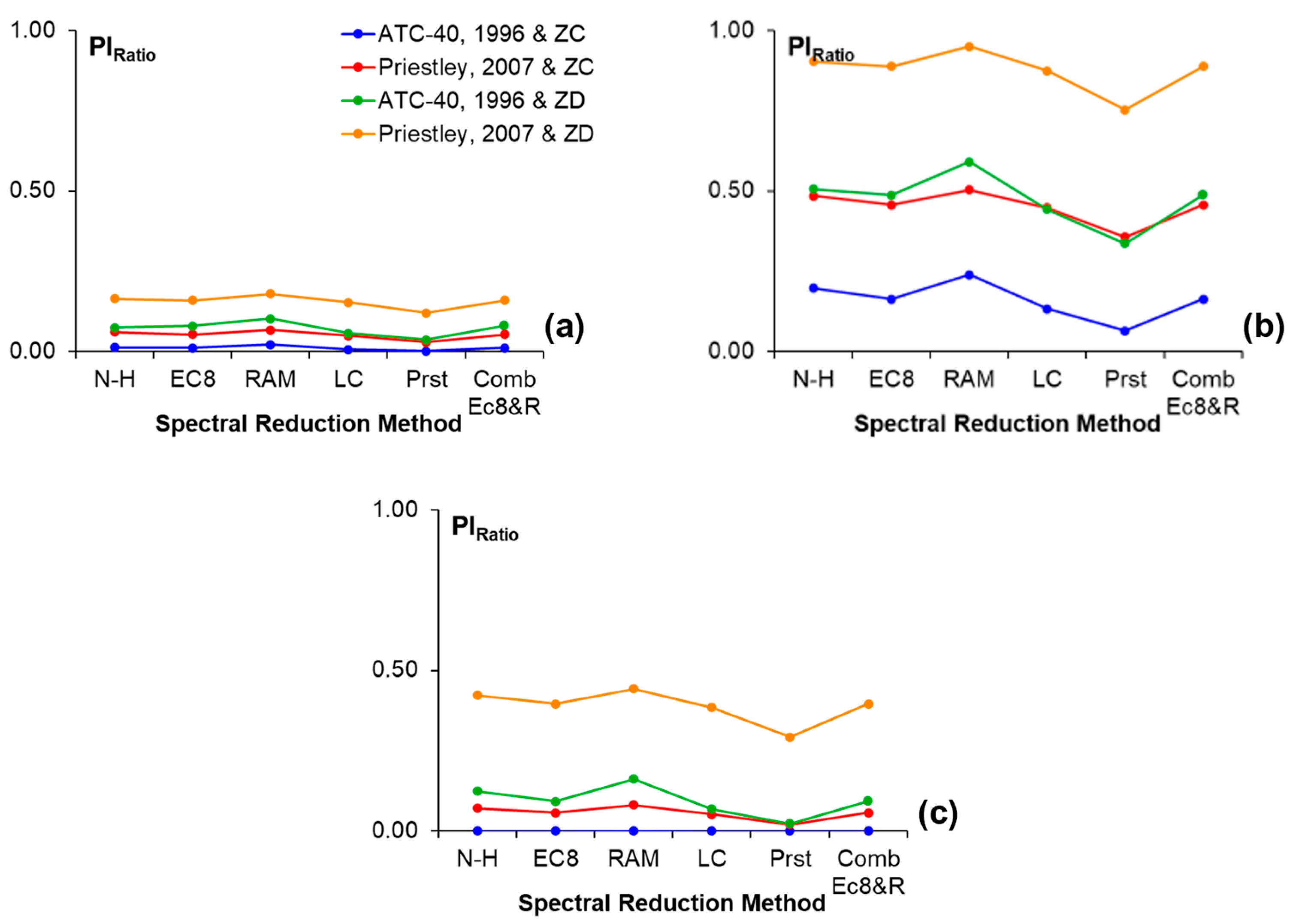

Average Pl

Ratio values are shown in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21, according to equivalent viscous damping, soil type, and codes. The evaluation of these values shows that the Ramirez method consistently produces the highest ratios, whereas the Priestley method yields the lowest.

According to

Figure 20 and

Figure 21, Pl

Ratio appears to be more critical when equivalent damping ratio was obtained according to the Priestley method. This situation is more apparent in older buildings, owing to insufficient ductility and strength capacities. Therefore, the plastic ductility ratios obtained for these buildings are higher than those of newer buildings. As can be seen from the capacity curves presented in

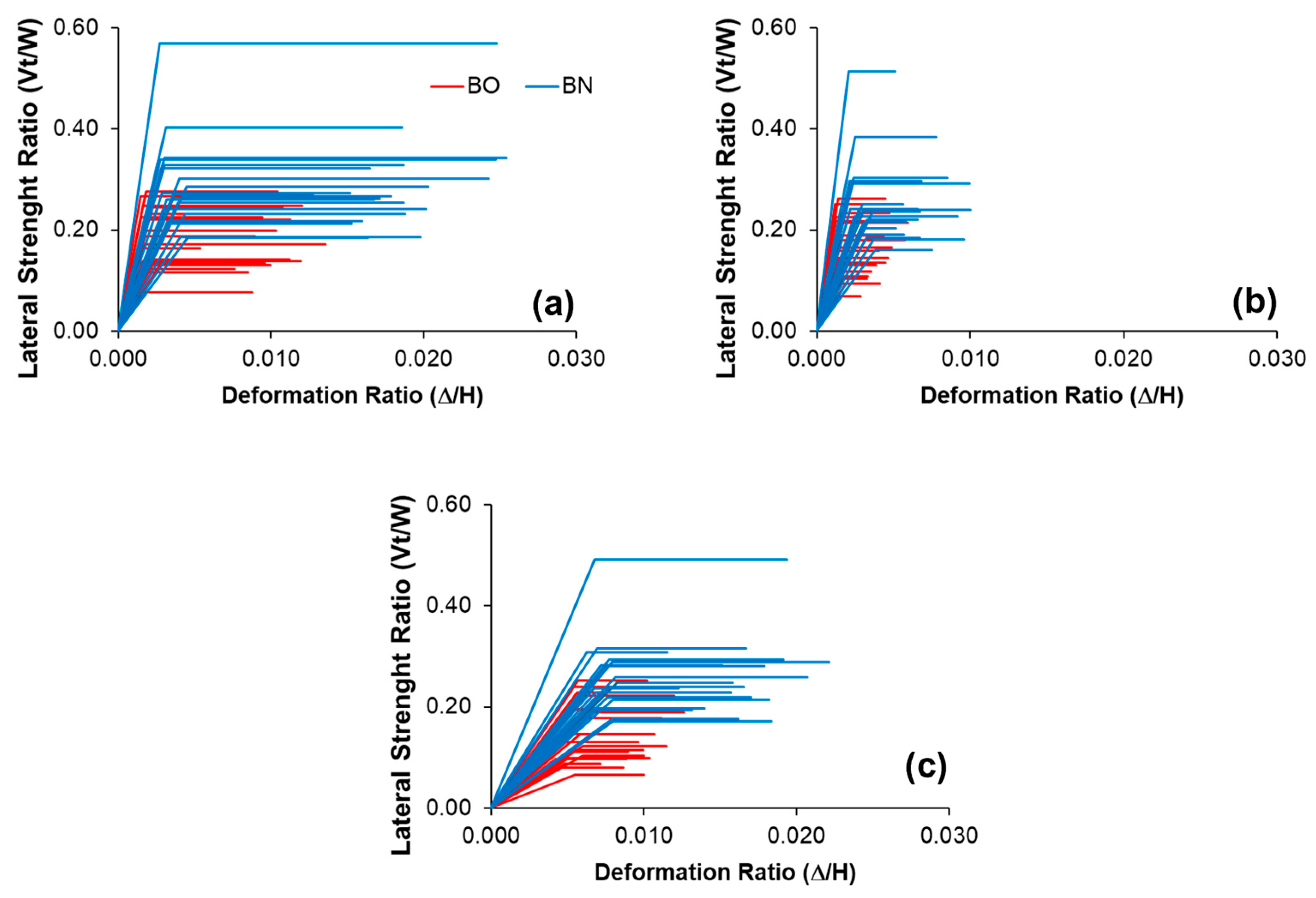

Figure 7, the highest displacement capacities were obtained from TEC-2007. For this reason, the Pl

Ratio of buildings determined according to TEC-2007 is less than one. In contrast, the displacement capacities obtained for TBEC-2018 buildings are considerably smaller, and hence the ratios calculated for TBEC-2018 are larger than the others. The displacement demands obtained for both seismic codes are similar; however, the displacement capacities determined according to the codes differ significantly. Therefore, remarkable differences are observed between the plastic capacity ratios [

50]. Although the displacement demands obtained for EC8/3 are higher, due to the approaches adopted in the code, the yielding displacement occurs at a larger deformation level. Therefore, the resulting Pl

Ratio values are not affected by the demand values; the plastic demand capacity decreases, and Pl

Ratio does not reach very large values.

As clearly observed in

Figure 9, the displacement values corresponding to the same period are larger for ZD soil types than for ZC soils. Therefore, the demand displacements obtained for ZD soils increase. In contrast, the capacities obtained for the buildings remain constant. As a result, the Pl

Ratio for ZD soils is higher.