IL-1-Beta and TNF-Alpha in Gingival Crevicular Fluid of Patients with Orthodontic Aligners and Application of Vibrations with Sonic Toothbrush: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

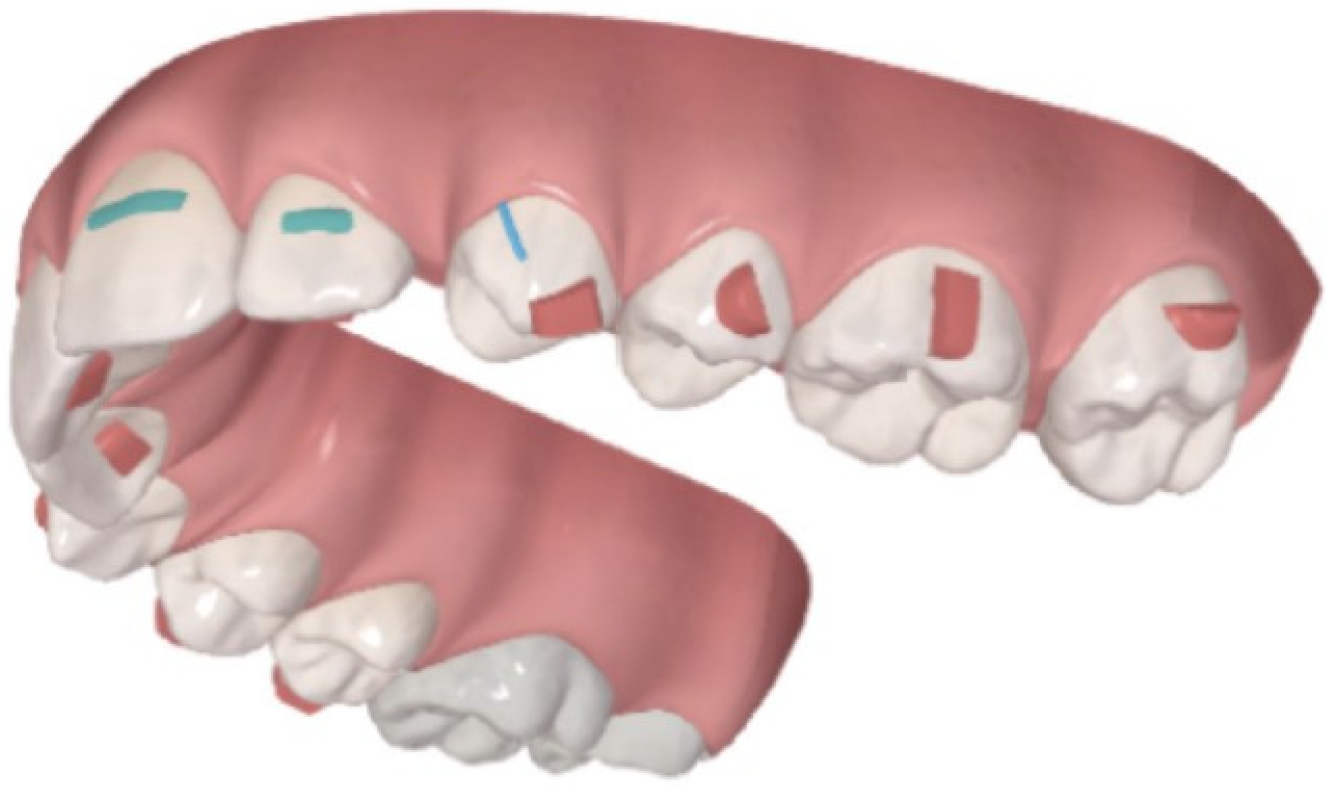

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Sample Characteristics

2.3. Experimental Protocol

2.4. Clinical Assessments and Sample Collection

2.5. Gingival Crevicular Fluid Collection

2.6. GCF Sample Processing and Cytokine Quantification

2.7. Statistical Analysis

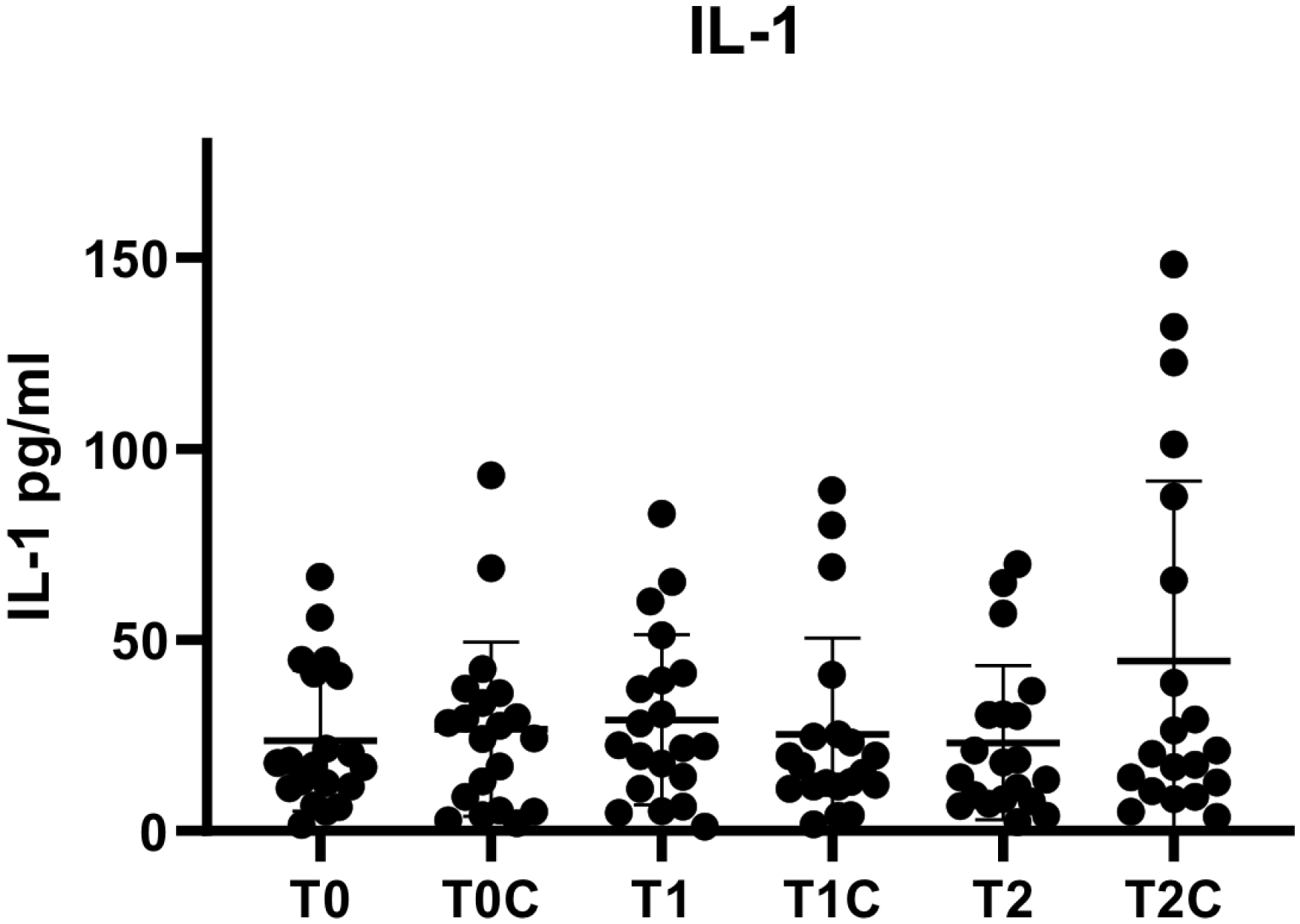

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Directions

4.2. Limitations of the Study

- Sample Size: One of the primary limitations of this study is the relatively small sample size, which may limit the statistical power to detect subtle differences between groups. A larger sample size could increase the reliability of the results and provide more robust evidence regarding the effects of vibratory stimulation on local cytokine levels in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF).

- Patient Compliance: The study relied on patient-reported compliance regarding the use of the vibratory stimulation device. However, the actual adherence to the prescribed protocol was not objectively monitored, leading to potential variability in the level of vibratory stimulation received by individual patients. This limitation may introduce biases in the results, as inconsistent or improper use of the device could impact the outcomes.

- Oral Hygiene Variability: Changes in oral hygiene practices during the study could have influenced the periodontal health of the participants. While instructions were provided for standardized oral hygiene, factors such as variations in brushing technique, frequency, or the introduction of new oral care products could have impacted the presence of supra-gingival plaque and the overall periodontal condition, which in turn may have influenced GCF cytokine levels.

- Fluctuations in General Health Status: Variations in the general health status of participants throughout the study period, including possible illnesses, stress, or fluctuations in medication use, may have introduced confounding variables that could affect both local and systemic inflammatory responses. As the study did not account for these potential fluctuations, the observed effects of vibratory stimulation might have been influenced by factors unrelated to the intervention itself.

- Hormonal Influences in Growing Patients: The potential impact of hormonal fluctuations, particularly in the case of younger, growing patients, represents another limitation. Hormonal changes associated with puberty, menstrual cycles, or other endocrine-related factors could modulate the inflammatory response and influence cytokine levels in GCF. The study did not control for these variables, making it difficult to isolate the effects of vibratory stimulation from the potential influence of hormonal variations, especially in female patients [33].

- These limitations underscore the complexity of studying cytokine modulation during orthodontic treatment, and further research with larger, more controlled populations and long-term follow-up would be necessary to validate and refine the conclusions drawn in this study.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castroflorio, T.; Gamerro, E.F.; Caviglia, G.P. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism during early orthodontic tooth movement with aligners. Angle Orthod. 2017, 87, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Hazemeijer, H.; de Haan, B.; Qu, N.; de Vos, P. Cytokine Profiles in Crevicular Fluid During Orthodontic Tooth Movement of Short and Long Durations. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujar, A.N.; Baeshen, H.A.; Alhazmi, A.; Bhandi, S.; Raj, A.T.; Patil, S.; Birkhed, D. Cytokine levels in gingival crevicular fluid during orthodontic treatment with aligners compared to conventional labial fixed appliances: A 3-week clinical study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2019, 77, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alikhani, M.; Lopez, J.; Alabdullah, H.; Vongthongleur, T.; Sangsuwon, C.; Alikhani, M.; Alansari, S.; Oliveira, S.M.; Nervina, J.M.; Teixeira, C.C. High-frequency acceleration: Therapeutic tool to preserve bone following tooth extractions. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kau, C.H.; Nguyen, J.T.; English, J.D. The clinical evaluation of a novel cyclical force generating device in orthodontics. Orthod. Pract. 2010, 1, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kau, C.H. A radiographic analysis of tooth morphology following the use of a novel cyclical force device in orthodontics. Head Face Med. 2011, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leethanakul, C.; Suamphan, S.; Jitpukdeebodintra, S.; Thongudomporn, U.; Charoemratrote, C. Vibratory stimulation increases interleukin-1 beta secretion during orthodontic tooth movement. Angle Orthod. 2016, 86, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikhani, M.; Sangsuwon, C.; Alansari, S.; Nervina, J.M.; Teixeira, C.C. High Frequency Acceleration: A New Tool for Alveolar Bone Regeneration. JSM Dent. Surg. 2017, 2, 1026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Azeem, M.; Afzal, A.; Jawa, S.A.; Haq, A.U.; Khan, M.; Akram, H. Effectiveness of electric toothbrush as vibration method on orthodontic tooth movement: A split mouth study. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2019, 24, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Chavakis, T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van der Sluijs, E.; Slot, D.E.; Hennequin-Hoenderdos, N.L.; Valkenburg, C.; van der Weijden, F.G.A. The efficacy of an oscillating-rotating power toothbrush compared to a high-frequency sonic power toothbrush on parameters of dental plaque and gingival inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2023, 21, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khocht, A.; Orlich, M.; Paster, B.; Bellinger, D.; Lenoir, L.; Irani, C.; Fraser, G. Cross-sectional comparisons of subgingival microbiome and gingival fluid inflammatory cytokines in periodontally healthy vegetarians versus non-vegetarians. J. Periodontal Res. 2021, 56, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genco, R.J.; Borgnakke, W.S. Risk factors for periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000 2013, 62, 59–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlstrom, B.L.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Johnson, N.W. Periodontal disease. Lancet 2005, 366, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, E.; López, M.; Vidal, H.; Martínez, M.; Virto, L.; Marrero, J.; Herrera, D.; Zapatero, A.; Sanz, M. Impact of periodontal therapy on systemic markers of inflammation in patients with metabolic syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020, 22, 2120–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, J.D.; Offenbacher, S. Systemic effects of periodontitis: Epidemiology of periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J. Periodontol. 2005, 76, 2047–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, G.H.; Nouer, D.F.; Pereira-Neto, J.S.; Urtado, M.B.; Novaes, P.D.; de Castro, M.; Veiga, M.C. The effects of systemic stress on orthodontic tooth movement. Australas. Orthod. J. 2008, 24, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLaine, J.K.; Rabie, A.B.; Wong, R. Does orthodontic tooth movement cause an elevation in systemic inflammatory markers? Eur. J. Orthod. 2010, 32, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viglianisi, G.; Polizzi, A.; Lombardi, T.; Amato, M.; Grippaudo, C.; Isola, G. Biomechanical and Biological Multidisciplinary Strategies in the Orthodontic Treatment of Patients with Periodontal Diseases: A Review of the Literature. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfuriji, S.; Alhazmi, N.; Alhamlan, N.; Al-Ehaideb, A.; Alruwaithi, M.; Alkatheeri, N.; Geevarghese, A. The effect of orthodontic therapy on periodontal health: A review of the literature. Int. J. Dent. 2014, 2014, 585048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawed, Y.; Beli, E.; March, K.; Kaleth, A.; Loghmani, T. Whole-Body Vibration Training Increases Stem/Progenitor Cell Circulation Levels and May Attenuate Inflammation. Mil. Med. 2020, 185, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, J.; Wendelken, M.; Driver, V.; Alvarez, O.M. Low-frequency ultrasound (20–40 kHz) as an adjunctive therapy for chronic wound healing: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Low Extrem. Wounds 2011, 10, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamberoni, F.; Borgese, M.; Pagiatakis, C.; Armenia, I.; Grazù, V.; Gornati, R.; Serio, S.; Papait, R.; Bernardini, G. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles with and without Cobalt Functionalization Provoke Changes in the Transcription Profile via Epigenetic Modulation of Enhancer Activity. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 9151–9159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weinheimer-Haus, E.M.; Judex, S.; Ennis, W.J.; Koh, T.J. Low-intensity vibration improves angiogenesis and wound healing in diabetic mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kono, T.; Ayukawa, Y.; Moriyama, Y.; Kurata, K.; Takamatsu, H.; Koyano, K. The effect of low-magnitude, high-frequency vibration stimuli on the bone healing of rat incisor extraction socket. J. Biomech. Eng. 2012, 134, 091001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohman, E.B., 3rd; Petrofsky, J.S.; Maloney-Hinds, C.; Betts-Schwab, H.; Thorpe, D. The effect of whole body vibration on lower extremity skin blood flow in normal subjects. Med. Sci. Monit. 2007, 13, CR71–CR76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Casale, R.; Hansson, P. The analgesic effect of localized vibration: A systematic review. Part 1: The neurophysiological basis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 58, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McGinnis, K.; Murray, E.; Cherven, B.; McCracken, C.; Travers, C. Effect of Vibration on Pain Response to Heel Lance: A Pilot Randomized Control Trial. Adv. Neonatal Care 2016, 16, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecca, P.A.; Borgese, M.; Raspanti, M.; Zara, F.; Fastuca, R.; Serafin, M.; Caprioglio, A. Comparative microscopic analysis of plastic dispersion from 3D-printed and thermoformed orthodontic aligners. Eur. J. Orthod. 2025, 47, cjaf014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marie, S.S.; Powers, M.; Sheridan, J.J. Vibratory stimulation as a method of reducing pain after orthodontic appliance adjustment. J. Clin. Orthod. 2003, 37, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zecca, P.A.; Bocchieri, S.; Carganico, A.; Caccia, M.; Fastuca, R.; Borgese, M.; Levrini, L.; Reguzzoni, M. Failed Orthodontic PEEK Retainer: A Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis and a Possible Failure Mechanism in a Case Report. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oprée, A.; Kress, M. Involvement of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL-1 beta, and IL-6 but not IL-8 in the development of heat hyperalgesia: Effects on heat-evoked calcitonin gene-related peptide release from rat skin. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 6289–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berry, S.; Rossouw, P.E.; Barmak, A.B.; Malik, S. The role ovariectomies and/or the administration of artificial female sex hormones play in orthodontic tooth movement: A systematic review. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2024, 27, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| IL-1 pg/mL | GF | SB | AP | FG | BS | PA | AC | CA | EB | OS | BE | GS | LP | PL | TP | PT | SG | SO | GM | MG |

| T0 | 21.53 | 40.52 | 12.52 | 16.77 | 41.1 | 55.88 | 13.04 | 11.19 | 44.58 | 6.21 | 44.84 | 1.58 | 20.29 | 17.80 | 5.01 | 17.17 | 18.42 | 6.62 | 11.60 | 66.50 |

| T1 | 60.04 | 21.70 | 28.20 | 22.43 | 65.16 | 41.35 | 14.14 | 1.20 | 4.65 | 11.08 | 51.28 | 5.13 | 30.53 | 83.07 | 6.33 | 39.32 | 37.06 | 19.61 | 17.62 | 22.10 |

| T2 | 21.02 | 18.07 | 56.86 | 17.91 | 30.37 | 9.33 | 69.77 | 36.73 | 8.33 | 7.69 | 64.84 | 2.33 | 30.48 | 13.40 | 6.56 | 3.93 | 7.16 | 11.37 | 30.14 | 14.10 |

| T0CTR | 33.47 | 29.75 | 36.01 | 16.93 | 42.39 | 28.31 | 27.47 | 4.11 | 5.01 | 2.08 | 24.06 | 2.70 | 37.34 | 68.81 | 24.28 | 8.98 | 5.31 | 29.42 | 12.93 | 93.10 |

| T1CTR | 69.08 | 11.60 | 80.10 | 11.02 | 15.17 | 89.17 | 17.00 | 12.52 | 11.60 | 12.00 | 4.17 | 1.71 | 40.85 | 19.55 | 24.73 | 19.78 | 23.11 | 12.81 | 25.24 | 3.10 |

| T2CTR | 17.28 | 29.15 | 87.53 | 21.02 | 26.36 | 16.65 | 20.11 | 122.66 | 8.98 | 4.95 | 8.33 | 3.62 | 38.71 | 148.33 | 65.64 | 12.64 | 10.43 | 14.02 | 131.95 | 101.23 |

| TNF pg/mL | GF | SB | AP | FG | BS | PA | AC | CA | EB | OS | BE | GS | LP | PL | TP | PT | SG | SO | GM | MG |

| T0 | 1.97 | 2.21 | 1.81 | 1.81 | 2.05 | 1.85 | 1.67 | 1.83 | 1.74 | 1.90 | 1.85 | 1.81 | 2.19 | 1.90 | 2.22 | 1.78 | 1.97 | 2.00 | 1.85 | 1.71 |

| T1 | 1.95 | 2.17 | 2.07 | 2.07 | 1.95 | 2.10 | 2.10 | 2.58 | 1.76 | 1.97 | 2.19 | 1.94 | 2.02 | 1.74 | 1.76 | 2.07 | 1.90 | 1.69 | 2.15 | 1.95 |

| T2 | 1.97 | 2.05 | 2.00 | 1.78 | 1.90 | 1.93 | 1.93 | 1.83 | 1.78 | 1.94 | 1.97 | 1.74 | 2.60 | 1.74 | 1.93 | 1.85 | 1.93 | 1.83 | 2.07 | 1.69 |

| T0CTR | 2.17 | 1.93 | 2.42 | 2.24 | 2.20 | 2.05 | 2.17 | 1.07 | 2.05 | 1.83 | 2.07 | 2.50 | 2.37 | 2.19 | 1.76 | 1.85 | 1.97 | 1.90 | 1.85 | 2.14 |

| T1CTR | 2.02 | 1.95 | 1.97 | 2.30 | 1.83 | 2.15 | 1.97 | 1.93 | 1.85 | 1.81 | 1.74 | 1.97 | 1.74 | 1.76 | 1.95 | 2.19 | 1.90 | 1.78 | 1.81 | 1.55 |

| T2CTR | 2.17 | 2.15 | 1.90 | 2.68 | 2.22 | 2.00 | 1.81 | 2.22 | 2.12 | 2.39 | 1.85 | 1.92 | 2.35 | 2.02 | 2.02 | 1.74 | 1.85 | 1.93 | 2.07 | 1.60 |

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Average | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 20 | 1.58 | 66.50 | 23.66 | 18.47 |

| T1 | 20 | 1.20 | 83.07 | 29.10 | 22.20 |

| T2 | 20 | 2.33 | 69.77 | 23.05 | 20.18 |

| T0C | 20 | 2.08 | 93.09 | 26.62 | 22.86 |

| T1C | 20 | 1.71 | 89.17 | 25.26 | 25.14 |

| T2C | 20 | 3.62 | 148.33 | 44.48 | 47.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Levrini, L.; Franchi, S.; De Zorzi, C.; Parpagliolo, L.; Carganico, A.; Giannotta, N.; Sacerdote, P.; Facchetti, G.; Saran, S. IL-1-Beta and TNF-Alpha in Gingival Crevicular Fluid of Patients with Orthodontic Aligners and Application of Vibrations with Sonic Toothbrush: A Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010344

Levrini L, Franchi S, De Zorzi C, Parpagliolo L, Carganico A, Giannotta N, Sacerdote P, Facchetti G, Saran S. IL-1-Beta and TNF-Alpha in Gingival Crevicular Fluid of Patients with Orthodontic Aligners and Application of Vibrations with Sonic Toothbrush: A Pilot Study. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):344. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010344

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevrini, Luca, Silvia Franchi, Carlotta De Zorzi, Luca Parpagliolo, Andrea Carganico, Nicola Giannotta, Paola Sacerdote, Giulio Facchetti, and Stefano Saran. 2026. "IL-1-Beta and TNF-Alpha in Gingival Crevicular Fluid of Patients with Orthodontic Aligners and Application of Vibrations with Sonic Toothbrush: A Pilot Study" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010344

APA StyleLevrini, L., Franchi, S., De Zorzi, C., Parpagliolo, L., Carganico, A., Giannotta, N., Sacerdote, P., Facchetti, G., & Saran, S. (2026). IL-1-Beta and TNF-Alpha in Gingival Crevicular Fluid of Patients with Orthodontic Aligners and Application of Vibrations with Sonic Toothbrush: A Pilot Study. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010344