1. Introduction

In recent years, the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) has been rapidly increasing, and enhancing their energy efficiency is essential for environmental protection and for emphasizing their role as sustainable modes of transportation [

1,

2]. In particular, the energy efficiency of EVs, known as electric mileage (miles per kWh), is directly related to their operational costs and can be improved through the efficient operation of air conditioning systems or various electronic components.

Among these systems, the air conditioning system of an EV consumes a significant amount of energy for heating in winter and cooling in summer [

3]. In particular, the use of HVAC systems in electric vehicles can increase overall energy consumption by up to 71% during heating and cooling processes. For example, at −10 °C, using the HVAC system can reduce the driving range from 155 km to 63 km, a decrease of approximately 59% [

4]. Therefore, precise temperature monitoring inside electric vehicles is crucial for efficient HVAC system operation, especially in situations where the system frequently operates to ensure thermal comfort for the driver and passengers.

Recent studies have focused on optimizing HVAC systems to reduce energy consumption in electric vehicles. Among these studies, some have explored the use of zonal air conditioning (zonal AC), which limits the cooling range within the vehicle to specific areas, while others have investigated methods to reduce power consumption by altering the vehicle’s physical characteristics, such as increasing the reflectivity of exterior surfaces or improving insulation [

5,

6]. Previous research has also utilized numerical modeling, which has served as the basis for evaluations and experiments.

However, most existing studies—whether physics-based or data-driven—predict only a single representative cabin temperature, typically measured near the center console or HVAC outlet. Physics-based models rely on simplified lumped thermal formulations or CFD-based simulations to estimate overall cabin conditions without considering spatial variability [

7,

8,

9]. Likewise, data-driven approaches using machine learning and deep learning models have focused on forecasting a single-point cabin temperature for HVAC control and energy optimization [

10,

11,

12]. These approaches do not account for the substantial temperature differences that arise across different seating positions and vertical levels inside a vehicle. As a result, relying on a single sensor is insufficient for capturing the heterogeneous thermal environments experienced by actual occupants, limiting the ability to deliver personalized comfort.

Table 1 presents a brief summary of previous research.

In contrast, our study developed a deep0020learning-based prediction system capable of accurately estimating temperatures at various locations inside a vehicle to enhance the energy efficiency of the HVAC system and optimize electric power consumption. The proposed system improves prediction accuracy by utilizing temperature measurements from various locations and is developed with consideration for real-world environmental conditions and data obtainable from the vehicle. This approach overcomes the limitations of conventional methods that rely on single-point temperature measurements by predicting temperatures at multiple locations.

A virtual environment capable of accurately predicting cabin temperature is essential for optimizing HVAC energy consumption. However, Negative-Temperature-Coefficient (NTC) sensors commonly used in vehicles can measure temperatures only at specific points and require physical hardware installation. This implies that they cannot reflect the spatial temperature variations experienced by different passengers.

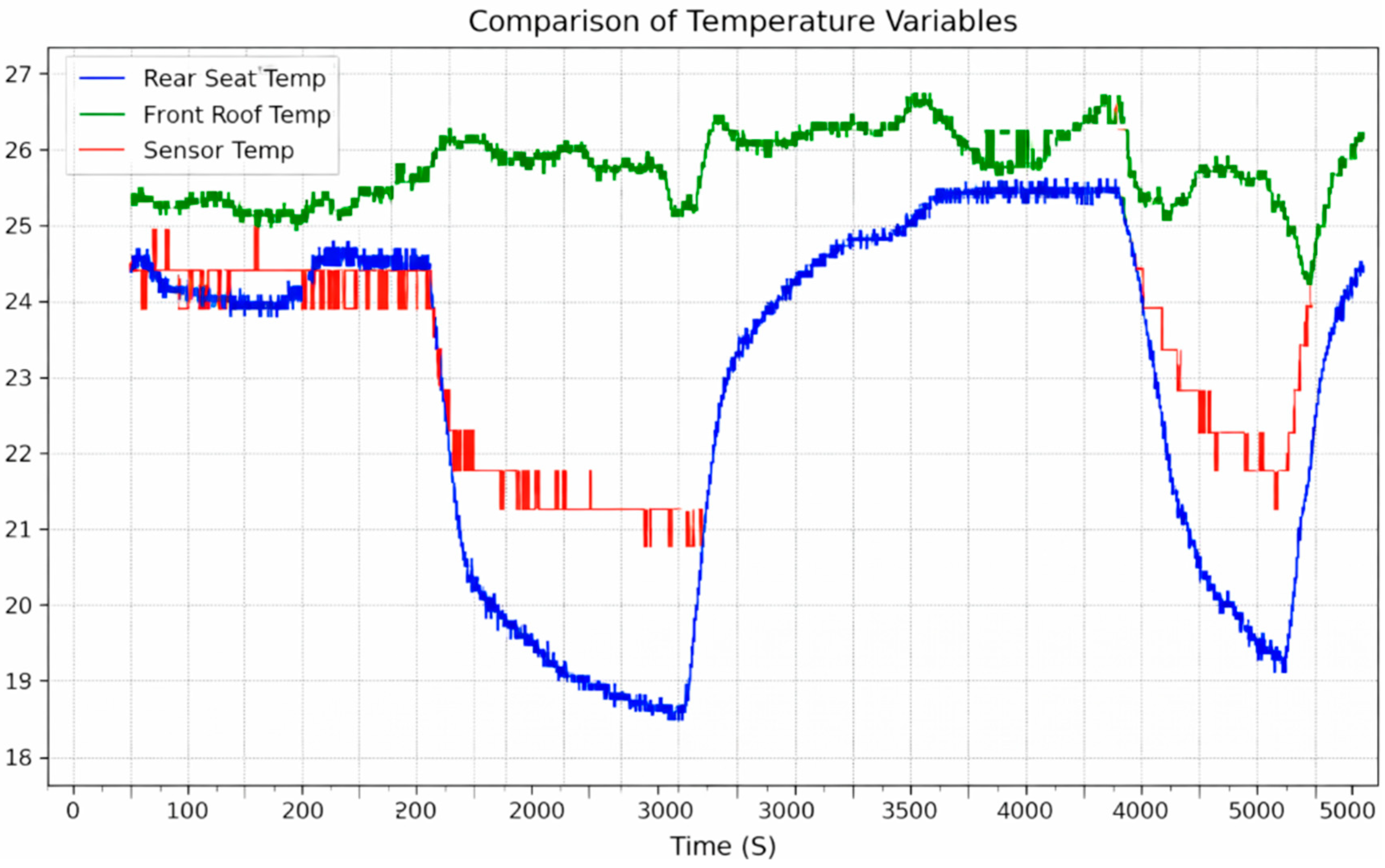

Figure 1 illustrates the discrepancy between the vehicle’s built-in sensor and the temperatures measured directly at specific cabin locations.

This discrepancy does not indicate that the built-in sensor itself is inaccurate or malfunctioning. Rather, it reflects the fundamental limitation of relying on a single representative measurement point, which cannot capture the local thermal conditions actually experienced by occupants at different positions in the cabin. Moreover, temperature varies significantly within the cabin depending on position, which directly affects perceived passenger comfort [

13]. This variation highlights the limitations of conventional air conditioning systems that rely on single-temperature measurements. Therefore, this study measures the temperatures at various positions within the cabin and establishes an experimental environment to collect spatial ground-truth temperatures that represent the actual thermal conditions experienced by occupants.

In this paper, temperature changes in various parts of a vehicle were predicted based on influencing factors, such as external and internal environmental conditions and the operation of the air conditioning system by passengers. All data utilized for the development of this system were collected directly, with a particular focus on predicting the temperatures at eight key points: five locations on the roof of the vehicle (three in the front and two in the rear) and three locations on the seats (two in the front and one in the rear).

The system comprehensively analyzed various factors that influence the temperature, including internal and external environmental information and how passengers use the air conditioning system. To achieve this, 46 different data points were used as input data to predict the temperature changes at these eight output data points. These data points directly reflect the impact of environmental conditions and passenger behavior patterns on the temperature.

The temperature prediction system was developed using time series deep learning models based on input data obtained from the vehicle and temperature values acquired from additional temperature sensors installed in the vehicle. The models used for deep learning training consider the time series characteristics of the temperature data and utilize recurrent neural network (RNN) layers that process sequence data. To achieve this, temperature-prediction training employs Vanilla RNN, Bidirectional RNN (BRNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), 1D Convolutional Neural Network (Conv1D), and Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) models. These models were trained for the purpose of developing and evaluating the performance of an in-vehicle temperature prediction system. The evaluation metric used in this study was the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), which calculates the percentage error between the predicted results and actual temperatures to assess the accuracy.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 describes the data used in the temperature prediction system and the processing methods applied to it. Specifically,

Section 2.1 and

Section 2.2 discuss the input and output data as well as the pre-processing steps for these data.

Section 2.3 provides a detailed explanation of the models used in the proposed temperature prediction system and the data post-processing methods, which are central to this study. In

Section 3, a comparative analysis of the results of each model is presented to evaluate the performance of the developed system. This paper aims to systematically describe the development process of a system capable of predicting cabin temperatures at various locations and to validate its performance, thereby discussing the potential for enhancing HVAC efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

Section 2 describes the datasets and various deep learning approaches used in this study to explain the proposed in-cabin temperature prediction method.

Section 2.1 and

Section 2.2 focus on the characteristics of the data and the data preprocessing procedures.

Section 2.3 presents the deep learning methodologies employed in this study, while

Section 2.4 explains the post-processing techniques applied to improve prediction performance.

2.1. Data Materials

The temperature in the cabin of a vehicle is significantly influenced by internal and external environmental conditions (such as temperature, humidity, and solar radiation) and the operation of the air conditioning system. Therefore, it is crucial to collect data under various temperature, humidity, and weather conditions [

14]. In this study, to build a more sophisticated system, data were collected under diverse road environments (such as highways and urban roads) and different weather conditions (such as day, night, and rainy conditions), while varying the air conditioning operation under these conditions. The 2019 Hyundai Kona EV was used for data collection. To conduct this study, it was necessary to utilize a part of the powertrain CAN information, which is typically secured in most vehicles. The research team selected the 2019 Kona vehicle because we were able to access the required signals through reverse engineering of the vehicle’s CAN system. However, the CAN information used in this study consists of general data that most manufacturers use or can obtain. Therefore, as long as the CAN data can be accessed, the proposed method can be applied to other vehicles as well. This enhances the generalizability of the developed system and strengthens the practicality and relevance of the research findings. All CAN signals were resampled to a unified 1 s interval, as their original sampling periods varied from 10 ms to 1 s, and using the slowest common rate prevented signal loss and artificial averaging effects.

In this study, an RTD (Resistance Temperature Detector was sourced from Sentrion Corporation in Seoul, Republic of Korea.) sensor was used to collect the output data, specifically the internal temperature of the EV. RTD sensors provide high accuracy and stability based on their linear resistance characteristics in response to temperature changes. This enables precise detection of subtle temperature variations inside the vehicle. While traditional NTC sensors collect temperature data at intervals of 0.5 °C, this study utilized RTD sensors to obtain more precise temperature data at 0.1 °C intervals. This makes them well suited for reliably capturing data under various environmental conditions and accurately measuring temperature changes within the EV.

The data used for training and testing in this study were collected from 7 July 2023, to 25 April 2024. The dataset comprises approximately 90 h of driving data collected under various air conditioning operations and three distinct environmental conditions: clear mornings during summer, clear afternoons during autumn, and cloudy mornings during winter. The final dataset contains 324,000 samples. Seasonal cabin temperature ranges were as follows: summer (Seat 16.5–31.1 °C, Roof 17.4–48.0 °C), autumn including partial shoulder-season data (Seat 5.4–31.9 °C, Roof 7.5–40.8 °C), and winter (Seat 4.0–32.3 °C, Roof 8.6–31.7 °C). To preserve temporal dependency, the dataset was split chronologically, with three predefined test scenarios held out and the remaining data partitioned into an 80% training and 20% validation set.

Although the environmental conditions were diverse, most driving sessions were conducted with only the driver due to limitations in available personnel during data collection. The detailed data collection conditions are presented in

Table 2.

This comprehensive dataset under various conditions ensures robust training and testing of the proposed temperature prediction system, enhancing its accuracy and reliability in predicting the internal temperature of the vehicle under different scenarios. The various environmental conditions described in

Table 1 were selected to evaluate the model’s performance under different external factors. Case 1 represents an environment where high external temperatures and strong solar radiation directly affect the vehicle roof, causing the cooling system to activate. In contrast, Case 3 depicts an environment with low external temperatures, leading to the activation of the heating system. Lastly, Case 2 represents a transitional season, where rain falls outside, providing an opportunity to assess the model’s predictive performance in intermediate conditions. The purpose of selecting these diverse environmental conditions is to verify whether the model can effectively predict and respond to temperature changes in real driving scenarios.

2.1.1. Input Data

The input data used in this study comprise 46 variables of in-vehicle data collected through CAN communication from the vehicle. These data points were selected based on their influence on the internal temperature of the vehicle, which includes both internal and external factors. The input variables are listed in

Table 3.

2.1.2. Output Data

Conventional vehicle interior temperature measurements primarily use NTC sensors. These sensors measure temperature by utilizing the characteristics of electrical resistance that change with temperature. Typically, these sensors are installed near air conditioning panels in vehicles, which places them in locations that do not account for spatial constraints, radiant heat, or convection currents. Moreover, NTC sensors require physical hardware that adds complexity to their installation and maintenance requirements. In addition, the nonlinear temperature characteristics of NTC sensors can pose challenges for precise temperature measurements and predictions [

15].

To overcome these limitations, this study employed RTD sensors to design and collect temperature data directly by measuring the interior temperature at eight key locations within the vehicle. These locations include five points on the roof and three seating positions, carefully selected to comprehensively capture the spatial temperature variations inside the vehicle. The specific locations of the measurement points are listed in

Table 4 and shown in

Figure 2.

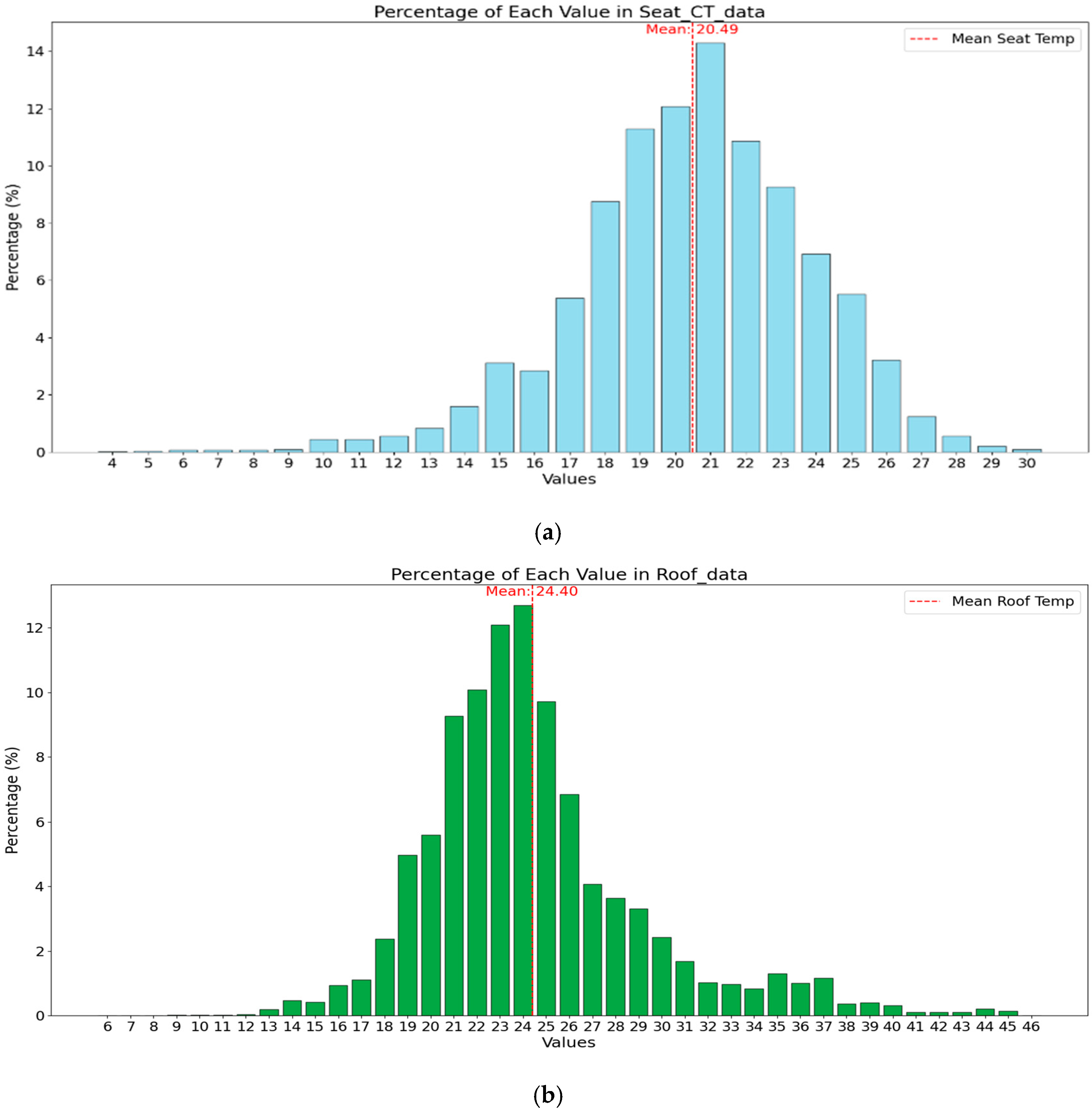

By utilizing the target data from the roof and seat measurement points, this study comprehensively considered the variations in internal vehicle temperature influenced by various input data. This approach provides an accurate understanding of the temperature changes experienced by drivers and passengers in the upper and lower areas of the cabin of the vehicle with different temperature distributions as shown in

Figure 3. Consequently, it provides an in-depth insight into how the heating and cooling systems of a vehicle regulate the internal environment.

The roof temperature data collected in this study ranges from 6.0 °C to 46.0 °C, with an average temperature of 24.40 °C. In contrast, the seat temperature data range from 4.0 °C to 30.0 °C, with an average temperature of 20.49 °C. This range and the average temperature demonstrate a diverse temperature distribution depending on the location, even with the same air conditioning operation and internal/external environmental conditions. This also highlights the limitations of indoor thermometers currently installed at the air conditioning control positions.

2.2. Data Pre-Processing

To implement a data-driven temperature prediction system, the integrity and completeness of the data are crucial. To ensure this completeness and integrity, we addressed cases where the output temperature data included missing values or sudden, unrealistic temperature readings during data storage. This outlier-handling process is detailed in

Section 2.2.1, where the steps taken to address and resolve such anomalies are described to ensure the data’s reliability for the temperature prediction system.

The input data are expressed in various scales and formats. For instance, the power consumption of the air-conditioner compressor is represented in units of 1000, whereas the data from the solar radiation sensor are expressed as decimal values with two decimal places less than 1. Understanding these diverse representations and accurately reflecting them in the model-training process is crucial [

16]. If the changes and significance of each feature are not carefully considered, the model may rely excessively on certain features or ignore important ones [

17].

The time series nature of data is also a critical consideration. Time series data are characterized by past information that influences future data. This characteristic is essential for understanding and predicting changes in the data over time [

18]. Therefore, this study performed data normalization and transformation processes before applying the data to model training.

2.2.1. Data Outlier Pre-Processing

Considering the time series characteristics of the input and output data, we treated values that deviate by more than 10% from the 10-step moving average as outliers based on the characteristics of the measurement system. The RTD sensors themselves did not exhibit extreme abnormal values; however, occasional spikes were observed due to CAN network transmission issues. Preliminary experiments confirmed that the ±10% rule selectively removed only these non-physiological spikes, whereas using a smaller threshold unintentionally filtered out normal temperature fluctuations.

For example, if the average temperature of the previous 10 data points is 22.3 °C, any value showing a deviation greater than ±2.23 °C (i.e., below 20.1 °C or above 24.5 °C) would be considered an outlier. These outliers were removed to maintain data integrity and consistency, ensuring high-quality data for stable model training.

The outliers typically appeared as single-timepoint values exceeding 40 °C or falling below 10 °C, which are physically implausible given that the surrounding cabin temperature remained stable within approximately 23–25 °C.

Let γ represent the average of the previous 10 data points. The criterion for identifying an outlier is a value that falls outside the range of ±10% from the average. The outlier range can be defined using the following equation. By using outlier removal, among approximately 324,000 time steps collected over 90 h, 303 data points (about 0.09%) were identified as outliers and removed. This process helped secure the reliability of the model’s learning and improved overall performance.

Figure 4 illustrates the data distributions before and after applying the outlier removal procedure.

2.2.2. Data Normalization

To ensure that all input features were reflected in the model training, the min-max normalization method was used to adjust the data to a range of [0, 1]. Min-max normalization was performed using the following equation:

Equation (2) is used for minimum–max normalization, representing each element of the data.

,

denote the minimum and maximum values of the observed data, respectively. This normalization process has several advantages. First, it reduces the tendency to depend overly on specific features and enhances the stability of the learning process [

19]. Second, it improves the interpretability of the model, clarifying the relative importance of each feature. Finally, it accelerates the learning process, allowing the model to converge more quickly [

20]. This normalization process was applied only to the input data and was considered an essential step in optimizing the performance of the model.

2.2.3. Data Sequencing for Model Input

The time series data utilized in this study encompass various factors of the vehicle’s internal and external environments, particularly input data such as humidity, temperature, and solar radiation measured by radiation sensors, all of which exhibit temporal variability. Given the characteristics of time series data, in which past data can influence present and future data, it is crucial to effectively incorporate them into the learning process. Additionally, it is important not only to predict the current temperature using past time series components but also to forecast future temperature trends to optimize the air conditioning system [

21].

To preserve these characteristics, the data collected were transformed using a many-to-many conversion technique. This technique uses input data from the past 60 s in a time series manner to predict the output data representing the temperature for the next 60 s.

The reason why we chose a 60 s input window is based on both the physical characteristics of cabin thermal dynamics and empirical evaluation. First, the temperatures measured at the roof and seat regions exhibit a delayed response following HVAC adjustments. Preliminary experiments showed that sequences shorter than 30 s failed to capture this delayed thermal behavior, whereas sequences longer than 90 s introduced instability due to limited data length per driving scene and the mixing of heterogeneous conditions within a single sequence. Second, after comparing multiple window lengths ranging from 30 to 120 s, we found that a 60 s window provided the most balanced trade-off among physical interpretability, data structure, model performance, and training stability. Therefore, 60 s was selected as the final input window for all experiments.

This approach considers the sequence of data collected at each time step, enabling the model to effectively learn the patterns of temperature changes over time. By sequencing the data, the model can accurately understand past temperature variations and environmental factors and use this information to predict future temperature changes [

22].

The many-to-many conversion technique plays a crucial role in capturing the dynamic relationships of the time series data, allowing the model to leverage temporal dependencies for more accurate temperature predictions. This enhances the predictive performance of the model, while providing high accuracy in handling the complexity of time series data.

2.3. Method

In this section, various deep learning models are evaluated and compared to improve the accuracy of the temperature-prediction model applied to a vehicle cabin in the temperature prediction system. The proposed algorithm is structured as shown in

Figure 5.

Among these, machine learning models applied to the temperature prediction system consider the time series characteristics of the temperature data and use RNN and sequence data-processing layers. Simple RNN, BRNN, LSTM, GRU, Conv1D, and TCN models were used for temperature-prediction training. In addition, hybrid models that combined these architectures were utilized for training.

An RNN is a neural network architecture specialized in processing sequential data, making it suitable for modeling dynamic patterns such as time series data [

23]. The core of an RNN is the incorporation of past information into current predictions. To achieve this, the RNN considers both the previous hidden state and the current input at each time step.

A BRNN extends the concept of an RNN by processing sequence data in both directions [

24]. It combines two independent RNNs, one processing the sequence forward and the other processing it backward. This bidirectional approach allows for the inclusion of both past and future contexts, enabling more accurate time series data analysis.

LSTM was developed to overcome the limitations of RNNs and effectively address long-term dependencies [

25]. This model excels in handling long sequences of data and maintaining important information over long periods through unique structures called memory cells. Memory cells include three gates—the input, output, and forget gates—which meticulously control the flow of information.

The GRU was designed to address the complexity of the LSTM while effectively solving the long-term dependency problem [

26]. The GRU is similar to the LSTM but has a simpler structure and primarily uses two types of gates: an update gate and a reset gate. The GRU effectively captures and processes long-term dependencies in time series data, offering high computational efficiency and lower memory usage, making it suitable for various time series data-processing tasks.

Conv1D is a convolutional neural network architecture suitable for one-dimensional data such as audio signals, time series data, and text data [

27]. This model was designed to identify local patterns in data and effectively capture the characteristics of time series data. Unlike RNN or LSTM, Conv1D can effectively capture the global patterns of the entire sequence or parts of the sequence, making it useful for identifying important local features in long sequences. Conv1D has been used in various fields, including text classification and financial time series analysis.

A TCN is a neural network architecture specialized for processing time series data, extending the concept of 1D convolutional neural networks to address long-term dependencies more effectively [

28]. Unlike the standard convolutions used in Conv1D, TCN employs dilated convolutions. In addition, it features a casual convolution to ensure that the model uses only past information and incorporates residual connections in the input network. The TCN is designed to effectively learn the overall patterns of time series data while maintaining temporal order. This model enhances the structural advantages of Conv1D with the specific features necessary for time series data processing, making it useful for learning long-term dependencies and complex temporal patterns in long sequences of time series data. To effectively learn the complex characteristics of time series data, this study proposes a hybrid model that combines convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and RNNs as represented in

Figure 6. This model leverages the powerful feature extraction capabilities of CNNs and the temporal sequence learning abilities of RNNs, thereby capturing both local patterns and long-term dependencies in the data.

Specifically, two different neural networks such as TCN-LSTM and Conv1D-LSTM are used in this study were combined. Each combination exploits the strengths of the two network types in different contexts. The TCN-LSTM combination broadens the receptive field through extended convolutions to capture long-term dependencies, followed by LSTM layers to learn temporal sequences. This approach helps understand changes over time in long time series data. However, the Conv1D-LSTM combination quickly identifies and processes local features through the Conv1D layers, after which the LSTM layers analyze deeper temporal patterns based on these features. Additionally, the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss function was used for training. MSE penalizes larger errors more heavily, helping the model capture the temperature trends more effectively and improving its accuracy. By focusing on minimizing larger deviations, MSE contributes to enhancing the overall prediction performance of the model. The detailed hyperparameters of the models used in this study are summarized in

Table 5.

Since the eight temperature locations exhibit different thermal behaviors, separate prediction models were trained for each temperature zone. For every model, the input tensor was defined as (batch size, 60, 46), corresponding to a 60 s sequence with 46 features, and the output tensor as (batch size, 60, 1), representing the future 60 s temperature sequence for a single target location. All models were trained using mean squared error (MSE) loss, and identical sequence lengths, feature sets, and output structures were applied across all architectures (RNN, TCN, and hybrid) to ensure a fair comparison.

2.4. Post Processing

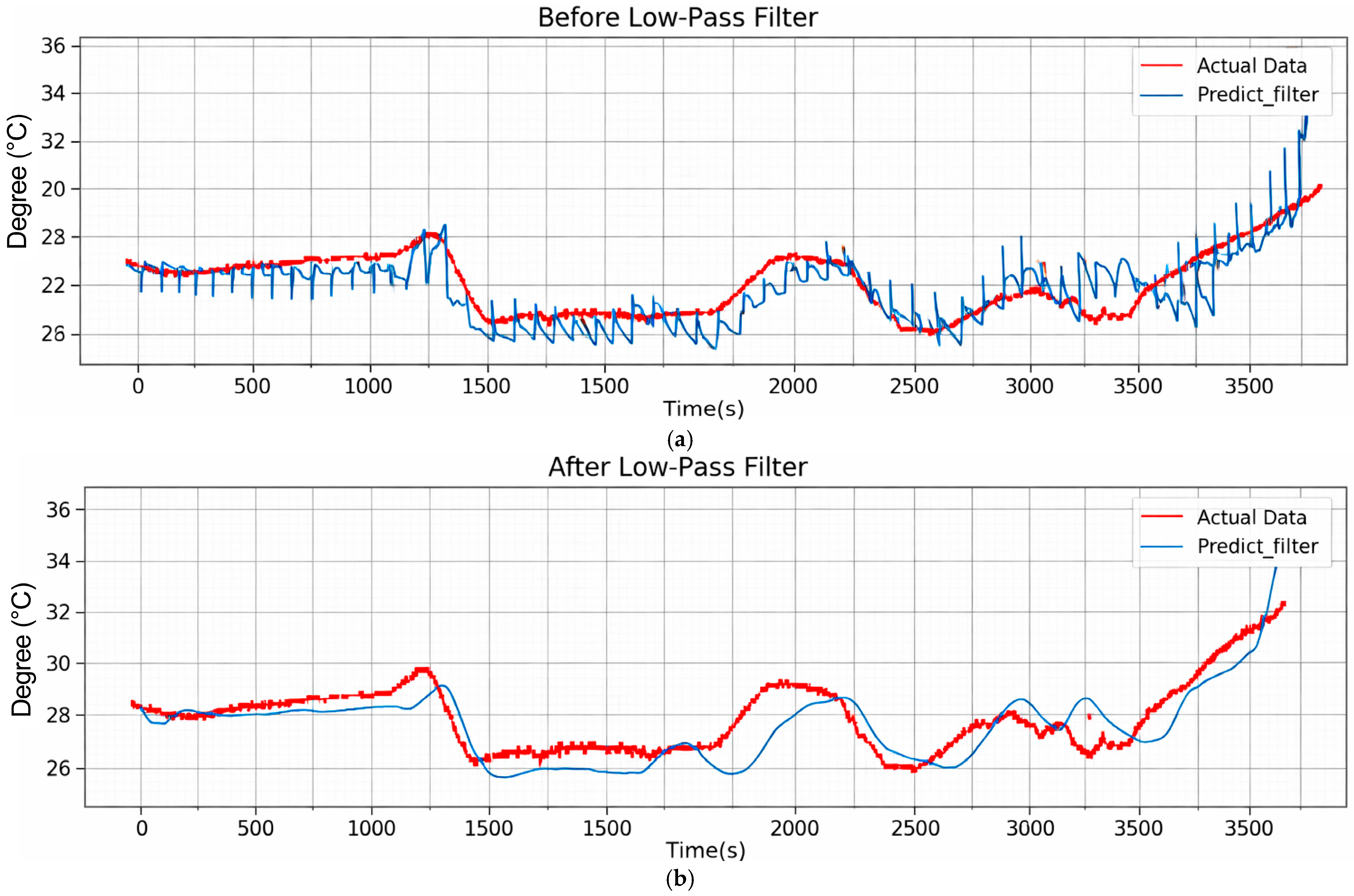

In regression tasks using neural networks, including our study, oscillations in the results are often observed [

29]. Therefore, a low-pass filter was applied to the prediction results obtained using the trained model. This filter operates by attenuating signals above a certain cutoff frequency, while allowing signals below the cutoff frequency to pass through. This process removes high-frequency noise, thereby increasing the smoothness of the prediction results [

30].

In this study, a third-order Butterworth low-pass filter was implemented using the scipy.signal library(version 1.16.2)in Python(version 3.13.8), with the cutoff frequency set to 0.01. This configuration effectively removes high-frequency noise while maintaining the smoothness of the prediction results.

As shown in

Figure 7a, the prediction results before applying the low-pass filter exhibited significant noise, with the blue line (prediction results) being much noisier than the red line (actual results). In the regression results, high-frequency oscillations resembling noise appeared, which degraded the prediction performance. To address this issue, a low-pass filter was applied to remove these high-frequency components, smoothing the predicted values and enhancing the model’s overall prediction performance. This filtering helped to reduce unwanted fluctuations and improved the stability of the model’s predictions.

Figure 7b illustrates the results obtained after applying the low-pass filter.

3. Results

Section 3 presents the experimental results obtained by applying the methodologies and datasets described in

Section 2. In this study, we evaluated the performance of temperature-prediction models under various environmental conditions (clear mornings in summer, rainy afternoons in summer, and clear afternoons in autumn) based on the selected models and applied methods. The results obtained by applying the test set to the trained models were analyzed, and the changes in the outcomes after post-processing were reviewed. The performances of the models were compared using both the MAPE and MAE metrics.

3.1. Evaluation Criteria

To compare the performance of the model using the predicted results and actual values, we utilized both MAPE and MAE as evaluation metrics. MAPE measures the accuracy of the model by calculating the percentage error between the actual and predicted values. MAPE is defined as follows:

where n is the number of data points,

is the actual value, and

is the predicted value. Because MAPE is expressed as a percentage, a value closer to zero indicates higher prediction accuracy of the model. In addition to MAPE, we also used MAE (Mean Absolute Error) to directly measure the absolute error between the predicted and actual values. MAE is defined as follows:

MAE provides the average of the absolute differences between actual and predicted values, helping to understand the errors in the same unit as the predicted values. It is particularly useful in overcoming the limitations of MAPE, which can produce inflated error values when the actual values are small. Therefore, MAE is used exclusively for comparing model performance after the final application of the low-pass filter, providing a more direct and unit-consistent evaluation of prediction accuracy. In addition to the MAPE, other metrics such as the root mean square error (RMSE) or mean squared error (MSE) can be used for model evaluation. However, this study chose the MAPE because it expresses the relative size of prediction errors in an easily interpretable percentage format. This is particularly useful for comparing prediction values at different scales.

Therefore, the model’s performance was evaluated using MAPE for general comparisons, while MAE was additionally used for models with the Low-Pass Filter applied. This dual approach allowed for a comprehensive assessment, with MAPE providing a percentage-based error metric and MAE offering a direct, unit-consistent error measure for smoother, filtered predictions. This approach serves as an indicator of model performance.

3.2. Experimetal Results

Before evaluating the performance of the proposed model, we first conducted preliminary experiments using simpler time series approaches. Specifically, we applied the classical statistical time series model ARIMAX and trained separate models for each of the eight temperature locations, using the RTD temperature at each location as the endogenous variable and 46 CAN signals as exogenous variables. In addition, we implemented a Feedforward Neural Network (FFN) based on a simple multilayer perceptron architecture, trained under the same input preprocessing conditions to ensure a fair comparison. Both baseline models were evaluated across three test cases (Cases 1–3) using the same metric (MAPE), and the results are summarized in

Table 6. In terms of MAPE, ARIMAX achieved an average error of 8.28%, while FFN achieved a lower average error of 5.33%. When assessed using MAE in

Table 7, ARIMAX produced an average of 1.98 °C, whereas FFN achieved 1.26 °C, demonstrating that even a simple neural network can provide a noticeable performance improvement over a statistical approach. These observations underscore the necessity of more advanced sequence-modeling architectures capable of capturing complex temporal patterns—such as RNN- and TCN-based models—which are expected to deliver superior predictive performance compared to basic baseline methods.

Building upon the performance observed from the baseline algorithms, we evaluated the performance of various deep learning-based models in developing a temperature prediction system for predicting EV cabin temperatures. Specifically, eight-time sequence models capable of sequence learning were used: RNN, BRNN, LSTM, GRU, Conv1D, TCN, Conv1D + LSTM, and TCN + LSTM. These models were compared and analyzed for their prediction performances across the three test cases using both the MAPE and MAE metrics. These environmental conditions and models are described in

Table 2 of

Section 2.1 (Data Materials) and in

Section 2.3 (Methods).

The key results of this study are presented in

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10, which compare the performance of each model before and after applying the low-pass filter.

Table 8 shows the results before applying the filter, whereas

Table 9 shows the results after applying the filter,

Table 10 includes the MAE results after applying the filter. These tables include the MAPE values for the prediction results of the three test cases and assess the prediction accuracy of each model. Additional results demonstrating the robustness of the model under different initializations and the performance evaluation based on the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) metric are provided in

Appendix A.

Additionally, we compared the differences between the internal sensors of the EV and the actual measured temperatures at eight points using the MAPE to identify the limitations and discrepancies of the in-vehicle temperature sensors.

The comparison results in

Table 8 and

Table 9 show that the performances of all eight learning models improved after the application of the low-pass filter. Specifically, the improved models exhibited an average MAPE decrease of approximately 0.13%. This corresponds to an overall prediction error reduction of approximately 0.034 °C, based on the average temperature of 25 °C used in this study. These results suggest that the low-pass filter helps reduce noise and smooth the prediction results, while also positively impacting the accuracy.

Table 11 highlights the significant differences between the temperatures measured by the internal sensors of the EVs and those measured by the thermometers installed directly in this study. The MAPE of 8.21% between the vehicle’s built-in temperature sensor and the RTD measurements at the occupant position quantifies the spatial discrepancy between the control reference point and the actual thermal environment experienced by the passenger. This value does not imply that the original sensor is erroneous; instead, it highlights that using a single control point as a global proxy for cabin temperature is insufficient in the presence of strong spatial gradients.

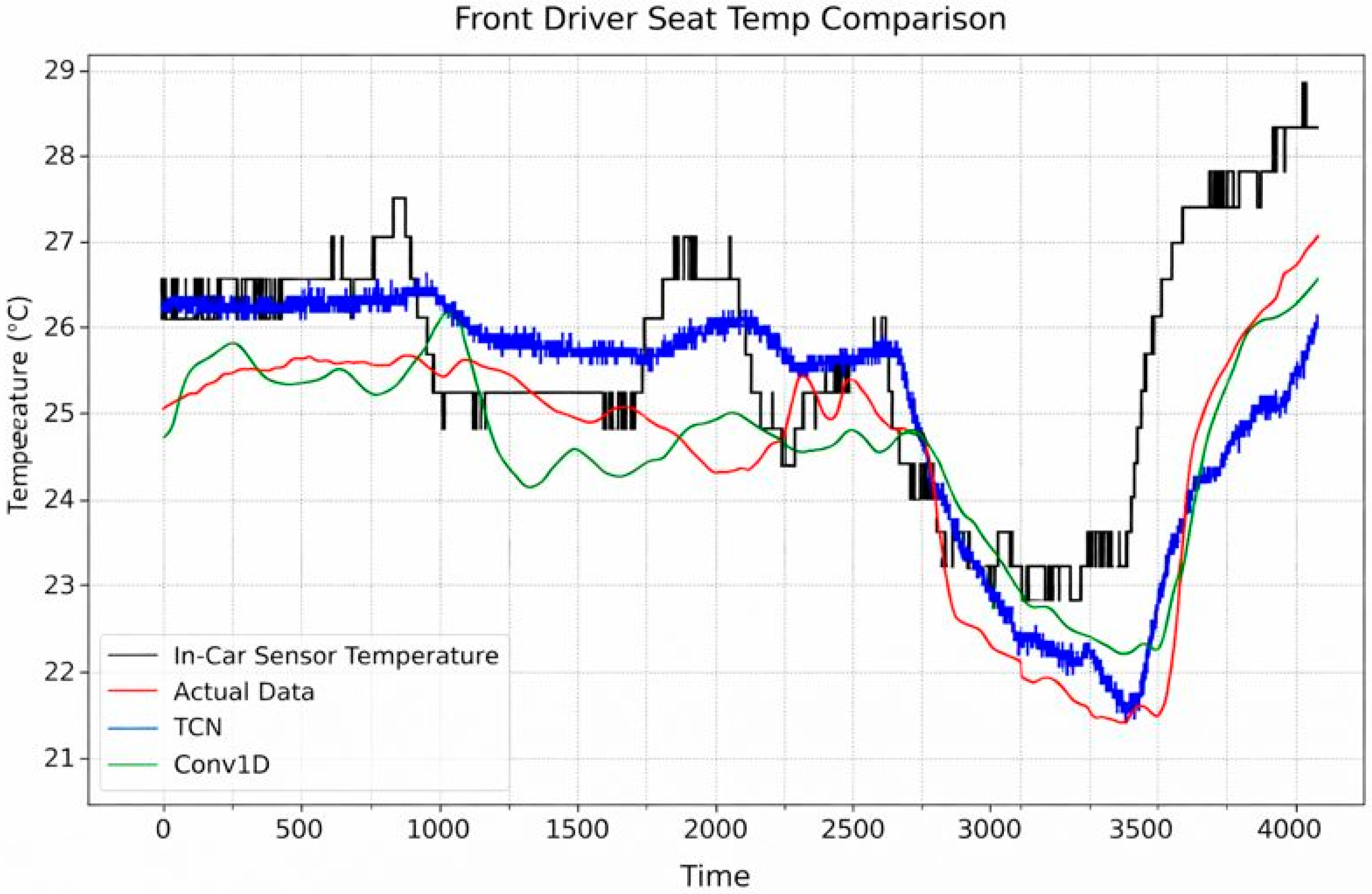

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 display the comparison between the prediction results of the best-performing model, TCN, and the lowest-performing model, Conv1D, against the actual temperature and the in-vehicle sensor temperature. These figures illustrate the differences in accuracy and performance between the two models in predicting the temperature inside the vehicle. As shown in

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, the actual thermometers on the roof exhibited increasing discrepancies with the actual roof temperatures over time, with significant temperature differences observed in the rear seats compared to the front seats. These results emphasize that the existing temperature sensors may be limited when considering and predicting temperature variations in different parts of a vehicle. In contrast, the models proposed in this study can respond more effectively to dynamic temperature changes in real vehicle-usage environments. This demonstrates the utility of the temperature-prediction models developed in this study.

Table 12 presents the results of the experiment conducted to evaluate the effect of input data normalization, comparing model performance before and after applying normalization. As shown in

Table 12, the model’s performance improved by approximately 50% in terms of MSE after normalization.

Among all the models, the TCN model recorded the lowest MAPE and MAE values, showing the best prediction performance. The TCN model consistently exhibited low error rates across the three test cases, demonstrating its high reliability and accuracy in the development of a temperature prediction system. This suggests that the temperature prediction system proposed in this study enhances applicability in real vehicle environments and can improve the comfort of EV users as well as overall vehicle energy performance.

4. Discussion

Based on the experimental results in

Section 3,

Section 4 discusses the advantages, limitations, and future potential of the proposed approach. In this study, we evaluated the efficiency of cabin temperature prediction for an EV’s temperature prediction system by directly training collected sequence data. The collected sequence data were gathered over approximately nine months and included EV cabin temperature conditions ranging from 4.0 °C to 46.0 °C. Additionally, it was assumed that the EV’s CAN data accurately reflect the vehicle’s operating conditions, and data processing was conducted based on this assumption.

Among the various models, the single TCN outperformed the traditional RNN and other CNN-based models. Although neural networks cannot be perfectly interpreted from a strict theoretical perspective, we consider the TCN to be more suitable for this task, and these differences in performance can be reasonably attributed to two main factors.

The TCN uses a dilated convolution to effectively model inherent temporal dependencies in time series data. This expands the range of information processed in each layer, allowing the model to remember a wide range of past states, including short sequences. By contrast, while RNNs and typical Conv1D models recognize temporal characteristics, TCN can also effectively capture the relationships between data points that are temporally distant. This ability is crucial for accurately predicting the impact of air conditioning operations or changes in the external environment on the temperature, as required for cabin temperature prediction.

- 2.

Improved Efficiency and Accuracy:

The architecture of the TCN significantly enhances the efficiency of training and prediction owing to its high parallel-processing capabilities. Even with relatively short sequences such as 60 data points, the TCN can independently process data at each time step, reducing the overall training time and increasing the response speed of the model. In addition, the TCN has fewer issues with gradient vanishing and offers high stability during training, thereby allowing for more accurate predictions. This is particularly beneficial for preventing overfitting and improving the generalization performance with small datasets.

Considering these aspects, the high performance of the TCN model in the temperature-prediction problem for temperature prediction systems reflects the TCN’s ability to effectively capture and predict complex patterns in time series data. In particular, even with a short sequence length of 60, the extended receptive field and multilayer structure of the TCN significantly contributed to capturing critical information within the temporal range without missing important details. This structure enables the TCN to handle long-term dependencies and complex patterns more effectively than before, making it particularly well-suited to the dataset used in this study.

Furthermore, the parallel-processing capability and gradient stability of the TCN provide an environment in which the model can learn stably without overfitting and perform faster computations, effectively modeling complex time series data. Additionally, the use of skip Connections, originally designed in ResNet, contributed to stable learning even with small datasets. These connections help mitigate issues such as vanishing gradients, allowing the model to learn deeper representations effectively, which enhances the overall performance and robustness of the model during training [

31]. These factors played a crucial role in the relatively high performance of the TCN observed in this study. However, the complexity of the TCN model can also lead to increased computational costs. The dilated convolution and residual connection in TCN effectively capture long-term dependencies, playing a crucial role in predicting vehicle temperatures. These characteristics, however, can result in higher computational overhead compared to simpler models such as RNN or Conv1D. Experimental results showed that increasing the number of TCN layers improved performance in terms of MAPE but also increased computation time. For example, in Case 1, a 2-layer TCN achieved an error rate of 4.8707% with a prediction time of 0.68 s. In comparison, a 4-layer TCN improved the performance with a 3.188% error rate but required 0.99 s for prediction. As the number of layers increased, the model was able to capture long-term dependencies more effectively due to a broader receptive field, but computational complexity also rose proportionally. Therefore, while TCN offers superior prediction accuracy, it is important to consider the high computational cost when deploying the model in real-time vehicle environments, especially in cases where computational resources are limited.

These findings can significantly contribute to optimizing vehicle temperature control systems and improving energy efficiency. The accurate temperature-prediction capability of the TCN model facilitates efficient management of the HVAC system, demonstrating its potential to enhance the vehicle’s energy usage efficiency.

This study was conducted based on data collected with only the driver present, and thus additional experiments are required to account for the impact of increased passenger numbers on interior temperature changes. Moreover, the dataset was obtained from a single vehicle model (Hyundai Kona EV), and therefore the model’s generalization to other vehicle types with different cabin geometries and HVAC characteristics remains limited. Future studies should incorporate data from multiple vehicle models and diverse passenger-loading scenarios to enhance the robustness and applicability of the proposed approach. Furthermore, the dataset lacks data from extreme weather conditions and is based on short-term collection, indicating the need for additional data acquisition and experiments to address these limitations. Future work will therefore incorporate structured metadata collection and expanded experimental conditions to improve overall model robustness and generalizability. Additionally, the computational load for real-time performance must be considered depending on the algorithm used and the ECU (electronic control unit) implementation. To address this, further research is needed to balance performance and efficiency by employing model light weighting techniques or hardware acceleration technologies.

Also, in a broader context, cabin temperature prediction can be interpreted as an integral component of three-dimensional scene understanding within the vehicle interior. The thermal distribution inside a cabin is strongly influenced by the spatial layout of seats, interior materials, occupant posture, and airflow pathways—factors that are fundamentally geometric and three-dimensional in nature. Future research may therefore benefit from integrating temperature prediction models with 3D indoor scene understanding frameworks, such as those used for human-centric indoor environments or slanted-deck scene analysis. Incorporating 3D cabin geometry, occupant detection, and spatial attention mechanisms could enable thermal models that are more sensitive to localized conditions and capable of predicting heat transfer patterns across different regions of the cabin. Such cross-disciplinary integration could lead to a unified in-cabin environment understanding model that jointly leverages thermal, geometric, and semantic information.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we evaluated various deep learning-based sequence models for predicting the cabin temperature of an EV to develop an in-cabin temperature prediction system. In particular, the TCN model outperformed traditional RNN models in capturing long-term dependencies in time series data, making it more effective at handling complex patterns. The TCN model demonstrated a significant improvement in prediction accuracy compared to other temperature prediction models, achieving a MAPE of 3.6963%, thereby establishing its reliability. By applying a low-pass filter, the MAPE of the TCN model improved from 3.6963% to 3.5287%, highlighting the filter’s effectiveness in removing high-frequency noise and enhancing the smoothness of the prediction results. Furthermore, while the MAPE of the in-vehicle thermometer was 8.2111%, the TCN model achieved a much lower MAPE of 3.5287%, confirming a substantial improvement in prediction accuracy. This indicates that the TCN model exhibits superior performance, potentially serving as a viable alternative to traditional vehicle sensors.

Currently, HVAC systems control the overall cabin temperature based on a single representative point within the vehicle, which limits their ability to provide thermal energy tailored to the individual needs of each passenger. This approach makes it difficult to accurately meet passengers’ temperature preferences, leading to potential energy waste. The system proposed in this study predicts temperature in real-time from various locations within the vehicle, enabling the HVAC system to be more precisely controlled according to each passenger’s desired temperature. This not only reduces unnecessary energy consumption but also improves overall energy efficiency. These results demonstrate that the application of deep learning technology can play a crucial role in optimizing HVAC systems and enhancing vehicle energy efficiency. However, to ensure the reliability and generalizability of the results, additional validation in scenarios involving more occupants and longer-distance driving situations is necessary. This study was conducted based on data collected with only the driver present, and additional experiments are necessary to account for the impact of increased passenger numbers on interior temperature changes. Furthermore, it is essential to collect data on factors such as the distribution and activity of passengers, which contribute to heat generation, as well as extreme weather conditions, to further generalize the research findings. Future research to enhance the performance of the system should focus on continuous comparison and improvement of prediction performance using various deep learning models, as well as structural enhancements to the models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L., W.N. and S.P.; methodology, H.L. and S.P.; software, H.L.; validation, H.L., W.N. and S.P.; formal analysis, H.L., W.N. and S.P.; investigation, H.L., W.N. and S.P.; resources, H.L. and S.P.; data curation, H.L. and S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L., W.N. and S.P.; writing—review and editing, H.L., W.N. and S.P.; visualization, H.L.; supervision, S.P.; project administration, S.P.; funding acquisition, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Industrial Technology Innovation Program (Project No. 20018646) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE, Republic of Korea), Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2023-00245084) and Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) grant funded by the Korea Government (MOTIE) (RS-2024-00415938, HRD Program for Industrial Innovation).

Data Availability Statement

Data not available due to participant consent and security data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

In this appendix, we present the results of additional experiments conducted in this study.

Table A1 shows the results of five trials performed by varying the initial weights of the TCN model, which is the representative model used in this paper. The results indicate that the model consistently achieved performance within a sufficiently valid range, with most trials exhibiting low standard deviations.

Table A2 presents the RMSE performance metric in addition to the MAE and MAPE values reported in the main paper. Unlike MAE and MAPE, the model with the best RMSE performance was GRU; however, the TCN model demonstrated the second-best performance with only a marginal difference.

Table A1.

MAPE results across different initial values(weight and bias) with low-pass filter.

Table A1.

MAPE results across different initial values(weight and bias) with low-pass filter.

| Model | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|

| TCN | 3.6088 ± 0.383% | 3.6845 ± 0.595% | 1.7101 ± 0.611% |

Table A2.

RMSE results with the low-pass filter.

Table A2.

RMSE results with the low-pass filter.

| Model | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Mean |

|---|

| RNN | 1.9082 | 2.0424 | 0.7519 | 1.5675 |

| BRNN | 1.9259 | 1.7486 | 0.9328 | 1.5358 |

| LSTM | 1.9104 | 1.3054 | 0.9665 | 1.3941 |

| GRU | 1.5549 | 1.3066 | 0.8090 | 1.2235 |

| Conv1D | 1.7720 | 1.4424 | 0.7404 | 1.3183 |

| TCN | 1.5855 | 1.4039 | 0.8255 | 1.2716 |

| Conv1D + LSTM | 1.9817 | 1.3882 | 1.5202 | 1.6300 |

| TCN + LSTM | 1.8730 | 1.5121 | 1.0684 | 1.4845 |

| | | | | 1.4282 |

References

- International Energy Agency. Demand for Electric Cars Is Booming with Sales Expected to Leap 35% This Year After a Record-Breaking 2022, I.E.A. 23 April 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/news/demand-for-electric-cars-is-booming-with-sales-expected-to-leap-35-this-year-after-a-record-breaking-2022 (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Helmers, E.; Marx, P. Electric cars: Technical characteristics and environmental impacts. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2012, 24, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.J. Study on Low Temperature Performance of Li-Ion Battery. Open Access Libr. J. 2017, 4, e4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paffumi, E.; Otura, M.; Centurelli, M.; Casellas, R.; Brenner, A.; Jahn, S. Energy Consumption, Driving Range, and Cabin Temperature in Electric Vehicle Design: The QUIET Project. European Commission, Joint Research Centre; Honda R&D Europe (Deutschland) GmbH. 2023. Available online: https://www.quiet-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/JRC-DirC_Paffumi_et_al_final_SDEWES2019.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Jose, S.S.; Chidambaram, R.K. Electric Vehicle Air Conditioning System and Its Optimization for Extended Range—A Review. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Brandes, G.; Rahman, A.; Paul, S. A Numerical Model to Evaluate the HVAC Power Demand of Electric Vehicles. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 96239–96248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jiang, F.; Song, H.; Liu, C.; Lu, B. Analysis and Validation of Transient Thermal Model for Automobile Cabin. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 122, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezrhab, A.; Bouzidi, M. Computation of thermal comfort inside a passenger car compartment. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2006, 26, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, S.; Kim, M.-H. Thermal Comfort in the Passenger Compartment Using a 3-D Numerical Analysis and Comparison with Fanger’s Comfort Models. Energies 2020, 13, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, F.; Zhang, X.; Duan, X. Modeling for vehicle cabin temperature prediction based on graph spatial–temporal neural network in air conditioning system. Energy Build. 2022, 72, 112229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolachalama, S.; Malik, H. A NARX Model to Predict Cabin Air Temperature to Ameliorate HVAC Functionality. Vehicles 2021, 3, 872–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warey, A.; Kaushik, S.; Khalighi, B.; Cruse, M. Data-driven prediction of vehicle cabin thermal comfort using machine learning and high-fidelity simulation results. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 148, 119083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Xin, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, L.; Deng, B. A Review of Sensor Applications in Electric Vehicle Thermal Management Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alum, A.S.; Fay, T.-A.; Cigarini, F.; Göhlich, D. Assessment of Thermal Comfort in an Electric Bus Based on Machine Learning Classification. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I. Engine Coolant Temperature Sensor in Automotive Applications. Department of Automotive Software Engineering, Technische Universität Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Saxony, Germany. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344327217_Engine_Coolant_Temperature_Sensor_in_Automotive_Applications (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Kamber, M. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 9780123814791. [Google Scholar]

- Wadi, S. Reversible Color and Gray-scale Based Images in Image Hiding Method Using Adding and Subtracting Operations. Smart Comput. Rev. 2014, 4, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooke, C.; Smith, J.; Leung, K.K.; Volkovs, M.; Zuberi, S. Temporal Dependencies in Feature Importance for Time Series Predictions. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Virtually, 18–24 July 2021. PMLR 139. [Google Scholar]

- Patro, S.G.K.; Sahu, K.K. Normalization: A preprocessing stage. Int. Adv. Res. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2015, 2, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samit, B.; Abhishek, D. Impact of Data Normalization on Deep Neural Network for Time-Series Forecasting. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.05519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; ISBN 9780262035613. [Google Scholar]

- Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; Le, Q.V. Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 2, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R.M. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): A gentle Introduction and Overview. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.05911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Paliwal, K.K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1997, 5, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Gulcehre, C.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Empirical Evaluation of Gated Recurrent Neural Networks on Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1408.5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An Empirical Evaluation of Generic Convolutional and Recurrent Networks for Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Pan, I.; Sur, K.; Das, S. Artificial neural network based prediction of optimal pseudo-damping and meta-damping in oscillatory fractional order dynamical systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE-International Conference on Advances in Engineering, Science and Management (ICAESM-2012); New Delhi, India, 30–31 March 2012, IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-81-909042-2-3. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.W. The Scientist and Engineer’s Guide to Digital Signal Processing; California Technical Publishing: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0966017632. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Comparison of in-car sensor readings with specific cabin point temperatures (Blue: Rear seat center temperature; Green: Front roof center temperature; Red: In-car sensor temperature).

Figure 1.

Comparison of in-car sensor readings with specific cabin point temperatures (Blue: Rear seat center temperature; Green: Front roof center temperature; Red: In-car sensor temperature).

Figure 2.

Cabin temperature measurement points: (a) Roof data with front positions marked in red and rear positions in yellow (b) Seat data with front positions marked in red and rear positions in yellow.

Figure 2.

Cabin temperature measurement points: (a) Roof data with front positions marked in red and rear positions in yellow (b) Seat data with front positions marked in red and rear positions in yellow.

Figure 3.

Distribution of rounded output data: (a) Distribution of seat data (b) Distribution of roof data.

Figure 3.

Distribution of rounded output data: (a) Distribution of seat data (b) Distribution of roof data.

Figure 4.

Comparison temperature data (a) before removing outlier, Outliers are in green circles(b)after removing outlier.

Figure 4.

Comparison temperature data (a) before removing outlier, Outliers are in green circles(b)after removing outlier.

Figure 5.

Temperature Prediction system (The algorithm of the Temperature Prediction system).

Figure 5.

Temperature Prediction system (The algorithm of the Temperature Prediction system).

Figure 6.

Architecture of hybrid models.

Figure 6.

Architecture of hybrid models.

Figure 7.

Actual Temperature vs. Prediction Temperature (Blue: Predict Data; Red: Target Data): (a) Before Applying low-pass filter (b) Applying low-pass filter.

Figure 7.

Actual Temperature vs. Prediction Temperature (Blue: Predict Data; Red: Target Data): (a) Before Applying low-pass filter (b) Applying low-pass filter.

Figure 8.

Comparison of actual and predicted temperature on Case 1: Front Driver Seat Temp.

Figure 8.

Comparison of actual and predicted temperature on Case 1: Front Driver Seat Temp.

Figure 9.

Comparison of actual and predicted temperature on Case 1: Rear Center Seat Temp.

Figure 9.

Comparison of actual and predicted temperature on Case 1: Rear Center Seat Temp.

Figure 10.

Comparison of actual and predicted temperature on Case 1: Front Center Roof Temp.

Figure 10.

Comparison of actual and predicted temperature on Case 1: Front Center Roof Temp.

Table 1.

Physics and data driven cabin temperature prediction methods.

Table 1.

Physics and data driven cabin temperature prediction methods.

| | Date | Time | Limitation |

|---|

| Physics-based models [7,8,9] | Model global cabin thermal behavior using heat transfer or CFD | Cannot predict passenger-level temperatures; no multi-point real-time prediction | No prior work predicts multi-point temperatures directly from vehicle signals (CAN) without additional sensors |

| Data-driven ML models [10,11,12] | Predict a single cabin temperature using machine learning/deep learning | Still single-point; no spatial thermal mapping; no multi-point prediction |

Table 2.

Test set configuration (Cases 1–3).

Table 2.

Test set configuration (Cases 1–3).

| | Date | Time | Temperature | Humidity | Passengers |

|---|

| Case 1 | 22 August 2023 | 09:30~10:30 | 31 °C ± 1 °C | 60%~65% | Driver Only |

| Case 2 | 26 October 2023 | 11:10~12:18 | 21 °C ± 2 °C | 70%~80% | Driver + Passenger |

| Case 3 | 19 January 2024 | 07:10~08:50 | 5 °C ± 1 °C | 70%~75% | Driver Only |

Table 3.

Input data for Proposed method.

Table 3.

Input data for Proposed method.

| Number | Description | Unit |

|---|

| 1 | Driver left vent air flow velocity | m/s |

| 2 | Driver right vent air flow velocity |

| 3 | Driver foot vent air flow velocity |

| 4 | Driver seat vent air flow velocity |

| 5 | Passenger left vent air flow velocity |

| 6 | Passenger right vent air flow velocity |

| 7 | Passenger foot vent air flow velocity |

| 8 | Passenger seat vent air flow velocity |

| 9 | Heat Pump control mode | - |

| 10 | Refrigerant pressure of the A/C system | PSI |

| 11 | Cabin solar energy | V |

| 12 | Windshield humidity | % |

| 13 | Outside Temperature of Ambient Sensor | °C |

| 14 | Outside temperature(FATC *) |

| 15 | Set point temperature |

| 16 | Temperature of the evaporator sensor |

| 17 | Temperature of the cabin sensor |

| 18 | Driver Vent discharge Temperature |

| 19 | Driver Floor discharge Temperature |

| 20 | Outside temperature display |

| 21 | Driver’s set temperature display |

| 22 | PTC heater power consumption | W |

| 23 | Power consumption of the A/C compressor |

| 24 | Climate system power consumption |

| 25 | Lateral acceleration speed | m/s2 |

| 26 | Longitudinal acceleration speed |

| 27 | Yaw rate | °/s |

| 28 | Vehicle speed | km/h |

| 29 | Wheel speed (high resolution), front, left-hand |

| 30 | Wheel speed (high resolution), front, right-hand |

| 31 | Wheel speed (high resolution), rear, left-hand |

| 32 | Wheel speed (high resolution), rear, right-hand |

| 33 | Operation status of A/C, Heat | - |

| 34 | Blower speed setting |

| 35 | Mix ratio of cold and warm air |

| 36 | Mix ratio of outside air to conditioned air |

| 37 | Operational mode of the auto defog system |

| 38 | Adjusts airflow direction |

| 39 | Air conditioning compressor speed feedback | rpm |

| 40 | Refrigerant temperature (Post-Compressor) | V |

| 41 | Refrigerant pressure (Post-Compressor) |

| 42 | Refrigerant temperature (Post-Evaporator) |

| 43 | Refrigerant pressure (Post-Evaporator) |

| 44 | Refrigerant temperature (Post-Condenser) |

| 45 | Blower speed PWM | PWM |

| 46 | Blower operation frequency | Hz |

Table 4.

Cabin temperature measurement points.

Table 4.

Cabin temperature measurement points.

| Location (Count) | Front | Rear |

|---|

| Roof (5) | Center | Left |

| Driver |

| Passenger | Right |

| Seat (3) | Driver | Center |

Table 5.

Summary of model architectures and training hyperparameters.

Table 5.

Summary of model architectures and training hyperparameters.

| Model | Layers | Hidden/Filters | Dilation (TCN) | Activation | Batch Size | Optimizer | Epoch |

|---|

| RNN | 4 | 256 | - | tanh | 32 | Adam | 300 |

| BRNN | 4 | 256 | - | tanh | 32 | Adam | 300 |

| LSTM | 4 | 256 | - | tanh | 32 | Adam | 300 |

| GRU | 4 | 256 | - | tanh | 32 | Adam | 300 |

| Conv1D | 4 | 256 | - | relu | 32 | Adam | 300 |

| TCN | 4 | 256 | 1, 2, 4, 8 | tanh | 32 | Adam | 300 |

| Conv1D + LSTM | 2 + 2 | 256 | - | relu/tanh | 32 | Adam | 300 |

| TCN + LSTM | 2 + 2 | 256 | 1, 2, 4, 8 | tanh | 32 | Adam | 300 |

Table 6.

Average MAPE of base line model: ARIMAX and MLP (without low-pass filter).

Table 6.

Average MAPE of base line model: ARIMAX and MLP (without low-pass filter).

| | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Mean |

|---|

| ARIMAX | 7.1137 | 7.3479 | 10.3824 | 8.2813 |

| MLP | 5.2281 | 5.5711 | 5.1862 | 5.3285 |

Table 7.

Average MAE of base line model: ARIMAX and MLP (without low-pass filter).

Table 7.

Average MAE of base line model: ARIMAX and MLP (without low-pass filter).

| | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Mean |

|---|

| ARIMAX | 1.9000 | 1.8367 | 2.2124 | 1.9830 |

| MLP | 1.3453 | 1.3760 | 1.0610 | 1.2608 |

Table 8.

MAPE Results without the low-pass filter.

Table 8.

MAPE Results without the low-pass filter.

| Model | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Mean |

|---|

| RNN | 4.6075 | 5.9241 | 2.7249 | 4.4188 |

| BRNN | 3.9935 | 5.3269 | 3.0844 | 4.1349 |

| LSTM | 5.2942 | 4.1706 | 3.6326 | 4.3658 |

| GRU | 4.6306 | 5.5958 | 5.1373 | 5.1212 |

| Conv1D | 6.0894 | 3.7867 | 5.5720 | 5.1493 |

| TCN | 3.4797 | 4.4031 | 3.2063 | 3.6963 |

| Conv1D + LSTM | 4.6102 | 3.4490 | 2.9672 | 3.6754 |

| TCN + LSTM | 4.5234 | 3.8331 | 2.6741 | 3.6768 |

Table 9.

MAPE Results with the low-pass filter.

Table 9.

MAPE Results with the low-pass filter.

| Model | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Mean |

|---|

| RNN | 4.2843 | 5.8832 | 2.5745 | 4.2473 |

| BRNN | 3.6351 | 5.2919 | 2.9715 | 3.9661 |

| LSTM | 4.9374 | 4.1273 | 3.4560 | 4.1735 |

| GRU | 4.3991 | 5.4842 | 5.0315 | 4.9716 |

| Conv1D | 5.9420 | 3.8090 | 5.4194 | 5.0568 |

| TCN | 3.1883 | 4.3412 | 3.0568 | 3.5287 |

| Conv1D + LSTM | 4.2999 | 3.5280 | 3.0197 | 3.6158 |

| TCN + LSTM | 4.2395 | 3.8360 | 2.6831 | 3.5862 |

| | | | | 4.1433 |

Table 10.

MAE Results with the low-pass filter.

Table 10.

MAE Results with the low-pass filter.

| Model | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Mean |

|---|

| RNN | 1.1895 | 1.4953 | 0.5433 | 1.0760 |

| BRNN | 1.0166 | 1.3231 | 0.6271 | 0.9889 |

| LSTM | 1.3390 | 1.0315 | 0.7270 | 1.0325 |

| GRU | 1.2169 | 1.3510 | 1.0597 | 1.2092 |

| Conv1D | 1.5812 | 0.9510 | 1.1401 | 1.2241 |

| TCN | 0.8535 | 1.0827 | 0.6425 | 0.8596 |

| Conv1D + LSTM | 1.1648 | 0.8540 | 0.6442 | 0.8877 |

| TCN + LSTM | 1.1651 | 0.9376 | 0.5708 | 0.8911 |

| | | | | 1.0211 |

Table 11.

MAPE between the actual in-car sensor measurements and our target.

Table 11.

MAPE between the actual in-car sensor measurements and our target.

| | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Mean |

|---|

| In-Car Sensor | 5.9354 | 10.3183 | 8.3796 | 8.2111 |

Table 12.

Data Normalization Effect of Input Scaling on Temperature Prediction Performance.

Table 12.

Data Normalization Effect of Input Scaling on Temperature Prediction Performance.

| | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Mean |

|---|

| Non- Normalization | 6.0986 | 6.8457 | 4.6256 | 5.8566 |

| Normalization | 3.1883 | 4.3412 | 3.0568 | 3.5287 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |