An Experimental Investigation on the Barrier Performance of Complex-Modified Bentonite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

2.1. Preparation of Complex-Modified Bentonites

2.2. Leachate

3. Methods

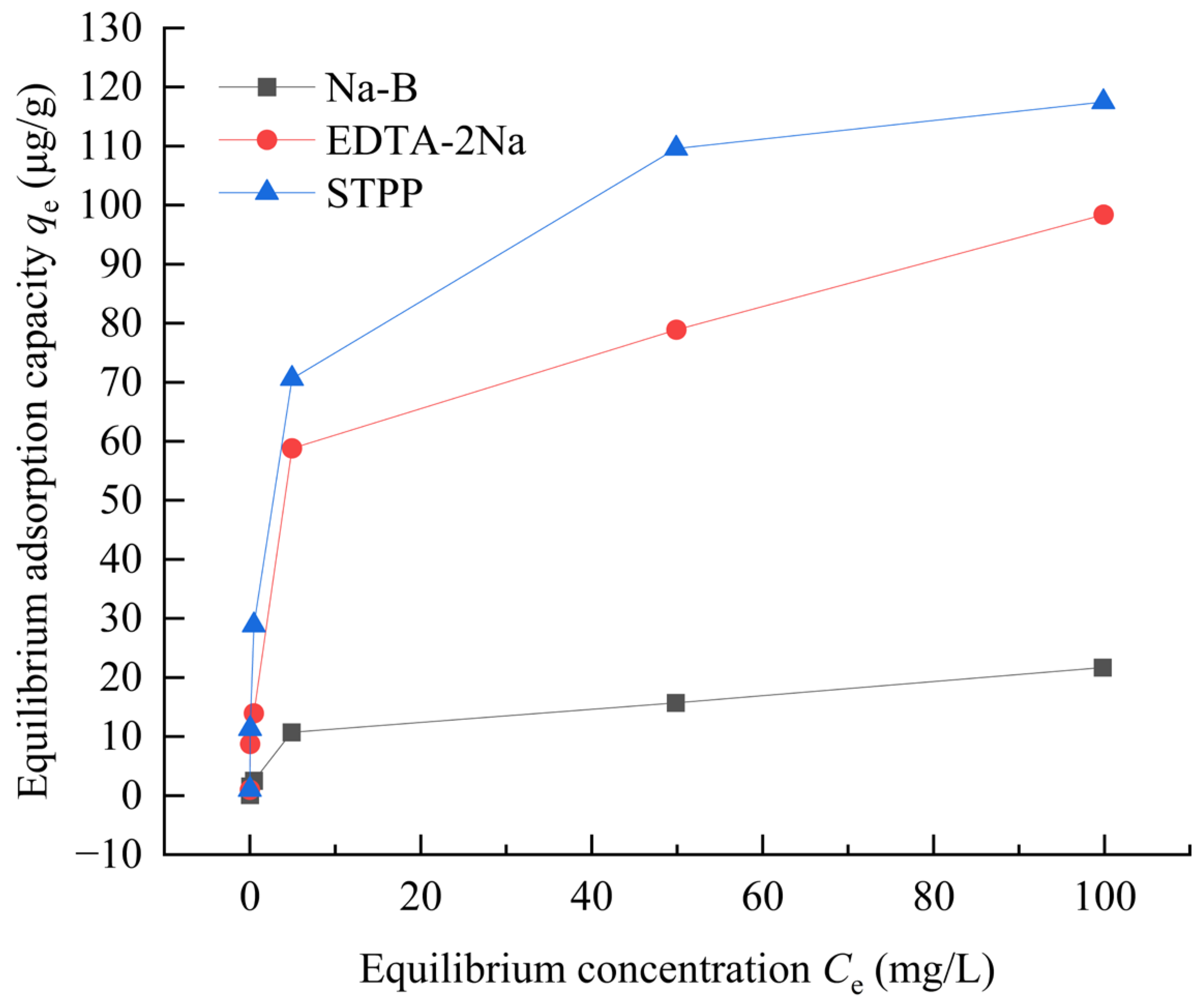

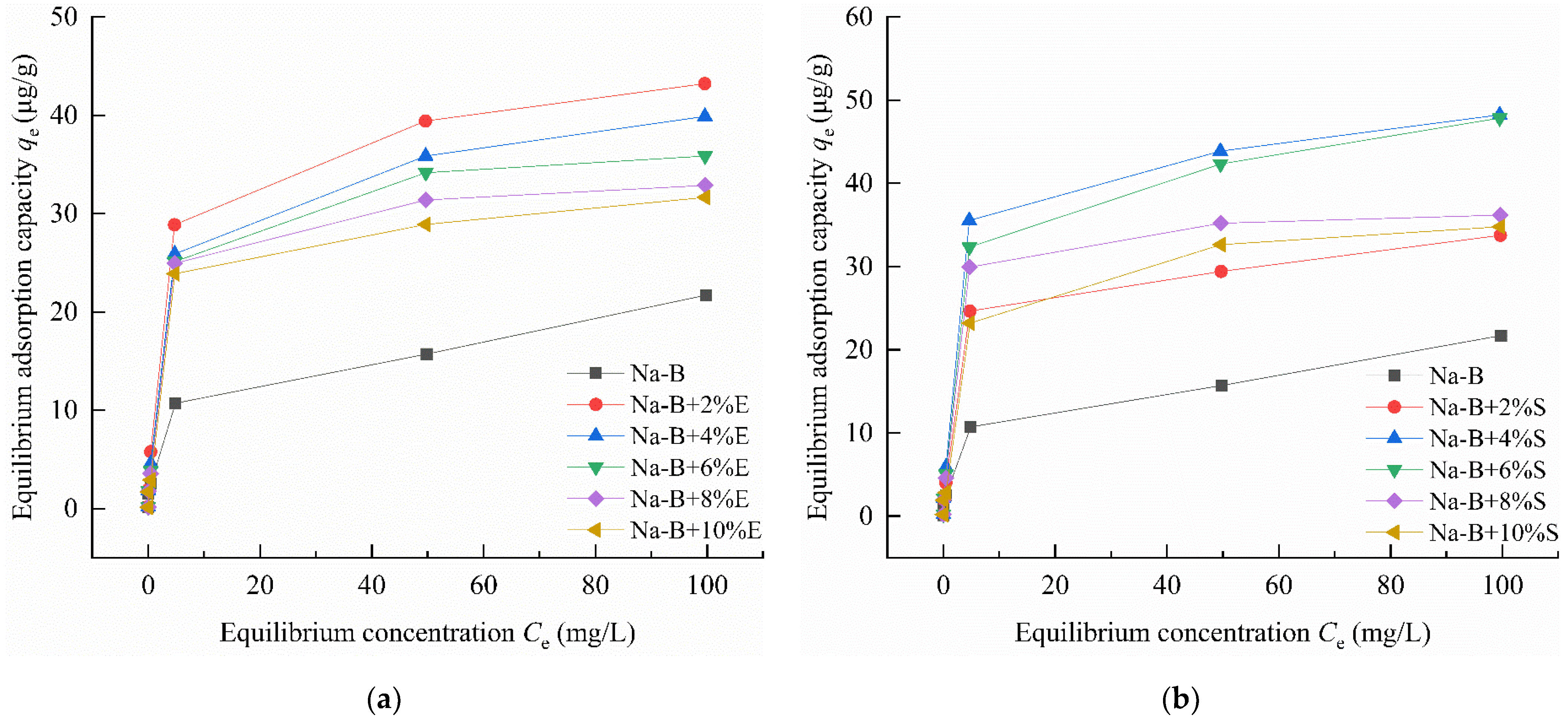

3.1. Batch Sorption Experiments

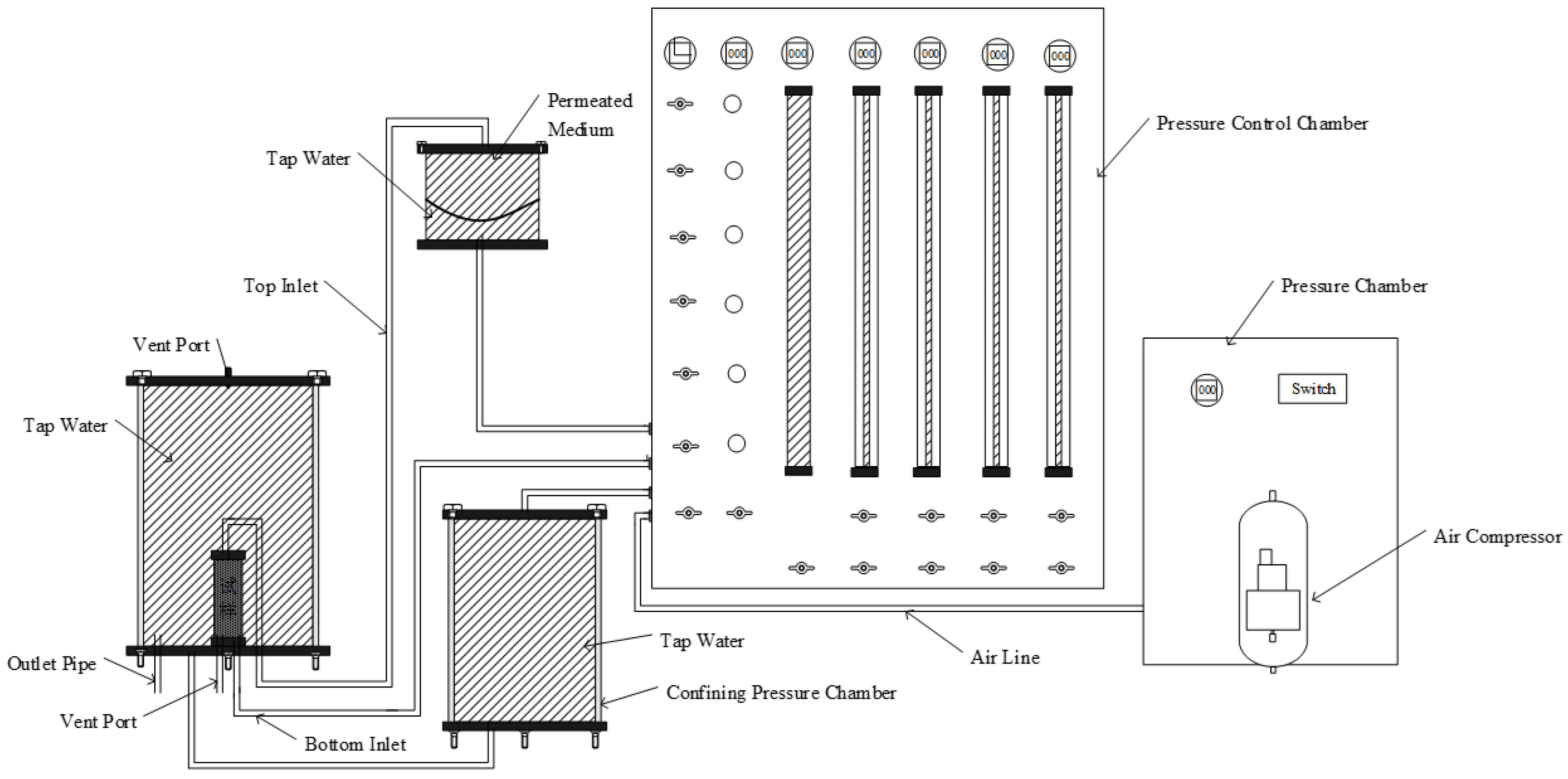

3.2. Hydraulic Conductivity Tests

3.3. BET Specific Surface Area Testing

3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Testing

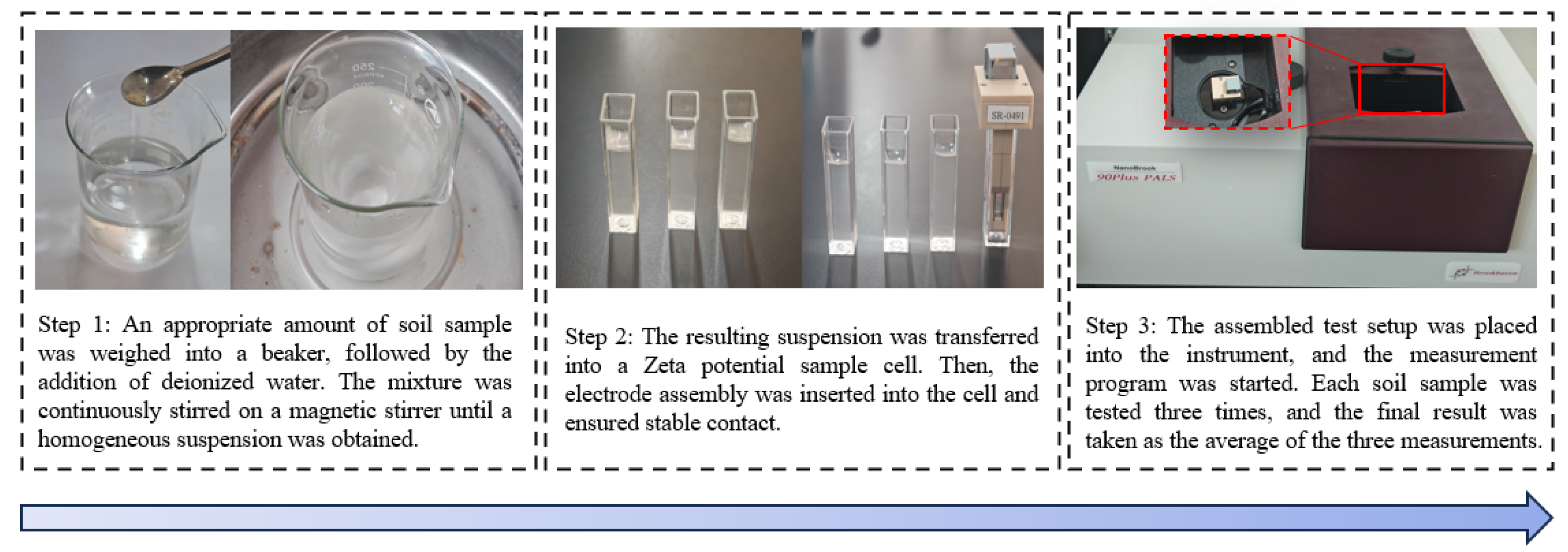

3.5. Zeta Potential Tests

4. Results

4.1. Adsorption Characteristic

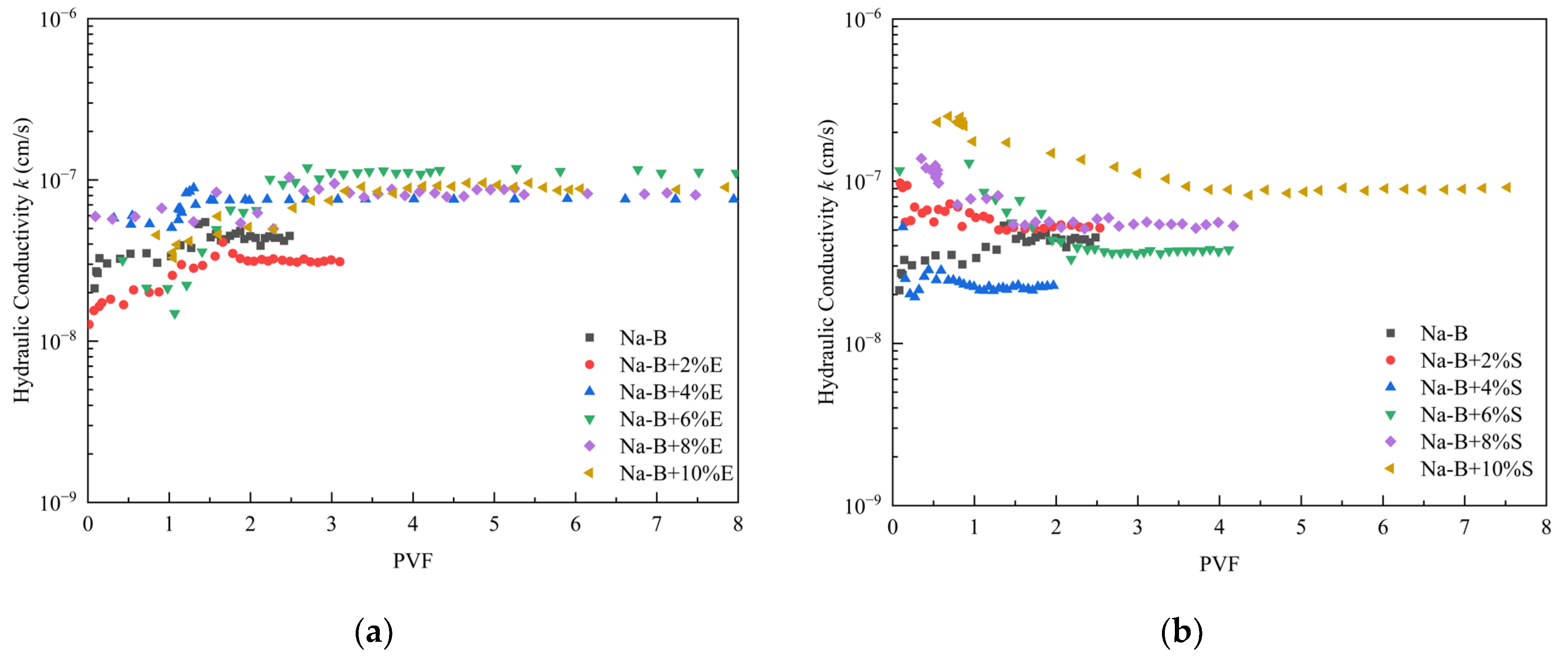

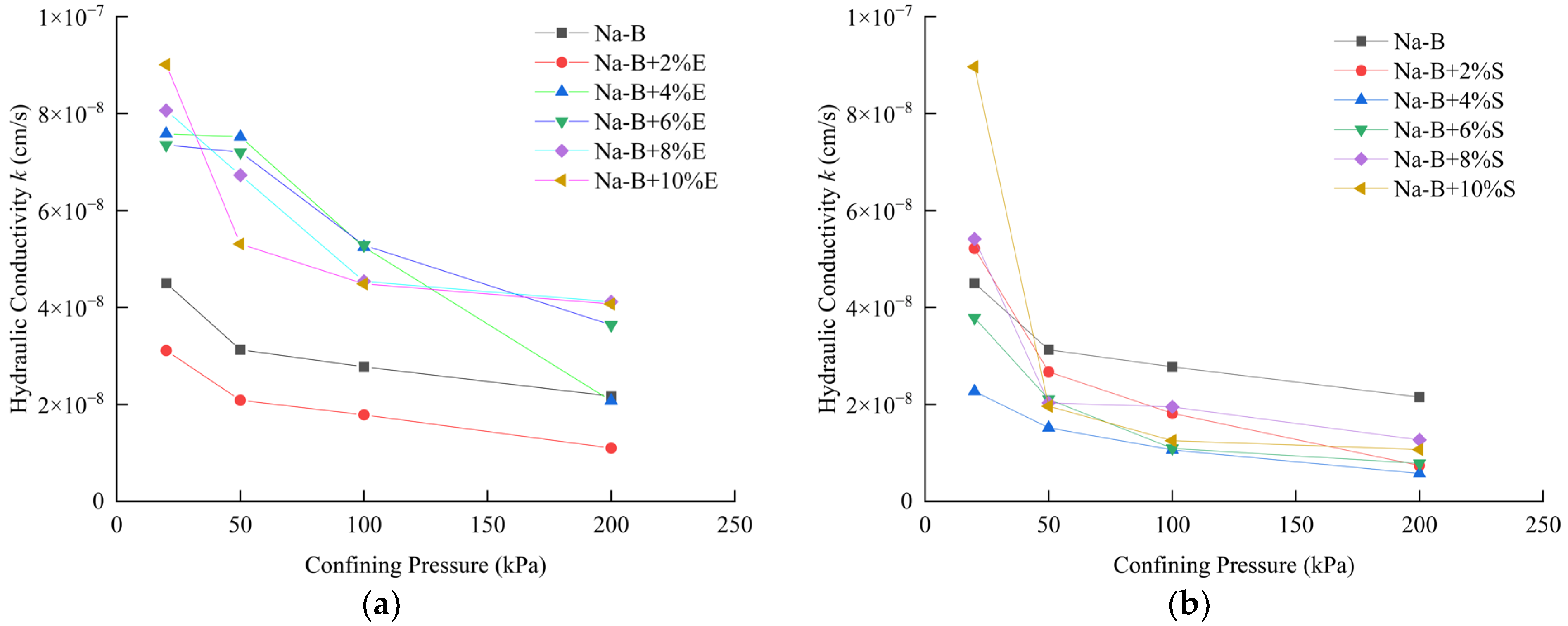

4.2. Hydraulic Conductivity

4.3. Morphological Analysis

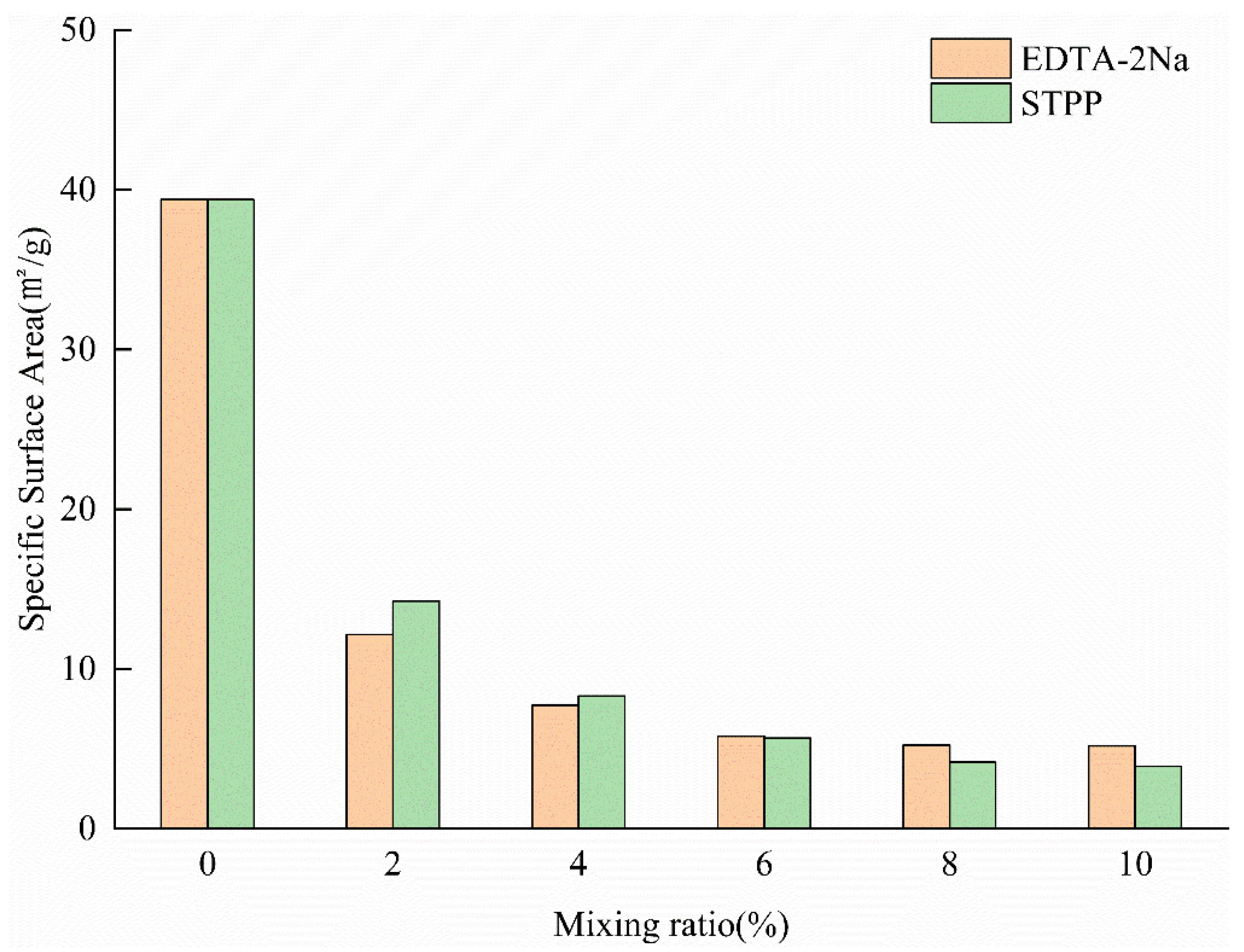

4.3.1. Specific Surface Area

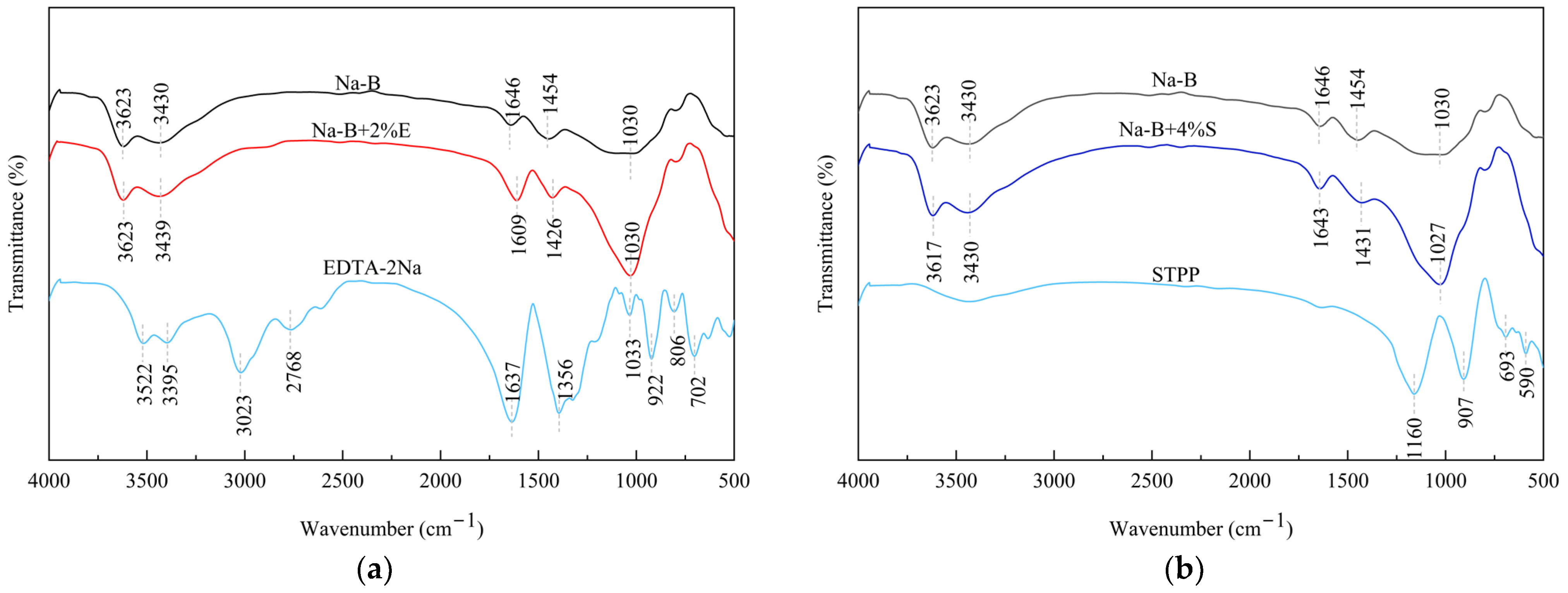

4.3.2. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

4.3.3. Mechanisms of Action of EDTA and STPP

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- In Zn(II)-containing extreme synthetic leachate, the maximum Zn(II) adsorption capacities of 2% EDTA-2Na and 4% STPP modified bentonites reached 43.22 μg/g and 48.22 μg/g, respectively. These values represent a 1.99–2.32-fold enhancement compared to unmodified bentonite. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy demonstrated that the enhanced adsorption originated from functional groups grafted by complexing agents. These included carboxyl (–COOH) and phosphate (PO43−) groups. Simultaneously, the significant negative shift in zeta potential demonstrates the enhanced capability of complexing agents to attract metal cations in bentonite.

- (2)

- BET specific surface area measurements demonstrated that the specific surface area of both EDTA- and STPP-modified sodium bentonites decreased with in-creasing additive content. The measured values decreased from 12.15 to 5.10 m2/g for EDTA-modified bentonite and from 14.25 to 3.89 m2/g for STPP-modified bentonite. This phenomenon results from the filling of montmorillonite interlayer domains and interparticle pores by complex molecules, which effectively blocks ion migration channels. These results confirm that the adsorption process is not governed by the material’s specific surface area.

- (3)

- Under a confining pressure of 200 kPa, the 4% STPP-modified sample exhibited an equilibrium hydraulic conductivity (k) as low as 5.74 × 10−9 cm·s−1. This value represents a reduction of nearly one order of magnitude compared to unmodified bentonite. The hydraulic conductivity (k) of EDTA-2Na-modified bentonite increased with higher additive dosage, reaching its minimum value at a 2% dosage. This trend is attributed to the reduction in bentonite mass per unit area, resulting in the coarsening of the pore network. In contrast, STPP utilizes electrostatic repulsion from its phosphate groups to promote the transition from disordered aggregation to parallel-aligned stacking of clay particles. Notably, all modified specimens exhibited hydraulic conductivity (k) values significantly lower than the international impermeability standard (1 × 10−7 cm·s−1) in extreme synthetic leachate. This confirms their suitability for engineering applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). Design, Construction, and Evaluation of Clay Liners for Waste Management Facilities; EPA/530-SW-86-007-F; Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. Available online: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=100018BV.txt (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- USEPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). Requirements for Hazardous Waste Landfill Design, Construction, and Closure; Report No. 625/4-89/022; Seminar Publication: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1989; pp. 1–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bouazza, A.; Rouf, M.A.; Singh, R.M.; Rowe, R.K.; Gates, W.P. Gas advection-diffusion in geosynthetic clay liners with powder and granular bentonites. Geosynth. Int. 2017, 24, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackelford, C.D.; Benson, C.H.; Katsumi, T.; Edil, T.B.; Lin, L. Evaluating the hydraulic conductivity of GCLs permeated with non-standard liquids. Geotext. Geomembr. 2000, 18, 133–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Likos, W.J.; Benson, C.H. Polymer elution and hydraulic conductivity of bentonite-polymer composite geosynthetic clay liners. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2019, 145, 04019061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, C.H.; Thorstad, P.A.; Jo, H.Y.; Rock, S.A. Hydraulic performance of geosynthetic clay liners in a landfill final cover. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2007, 133, 814–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meer, S.R.; Benson, C.H. Hydraulic conductivity of geosynthetic clay liners exhumed from landfill final covers. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2007, 133, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.L.; Zhang, R.; Reddy, K.R.; Li, Y.C.; Yang, Y.L.; Du, Y.J. Membrane behavior and diffusion properties of sand/SHMP-amended bentonite vertical cutoff wall backfill exposed to lead contamination. Eng. Geol. 2021, 284, 106037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.L.; Shen, S.Q.; Reddy, K.R.; Yang, Y.L.; Du, Y.J. Hydraulic conductivity of sand/biopolymer-amended bentonite backfills in vertical cutoff walls permeated with lead solutions. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2022, 148, 04022022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egloffstein, T.A. Natural bentonites—Influence of the ion exchange and partial desiccation on permeability and self-healing capacity of bentonites used in GCLs. Geotext. Geomembr. 2001, 19, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalia, J.; Bohnhoff, G.L.; Shackelford, C.D.; Benson, C.H.; Sample-Lord, K.M.; Malusis, M.A.; Likos, W.J. Enhanced bentonites for containment of inorganic waste leachates by GCLs. Geosynth. Int. 2018, 25, 392–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, C.H.; Chen, J.N.; Edil, T.B.; Likos, W.J. Hydraulic conductivity of compacted soil liners permeated with coal combustion product leachates. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2018, 144, 04018073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, S.L.; Benson, C.H.; Rauen, T.L. Hydraulic conductivity of geosynthetic clay liners to recirculated municipal solid waste leachates. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2016, 142, 04015076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalia, J.; Benson, C.H. Hydraulic conductivity of geosynthetic clay liners exhumed from landfill final covers with composite barriers. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2011, 137, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.N.; Benson, C.H.; Edil, T.B. Hydraulic Conductivity of Geosynthetic Clay Liners with Sodium Bentonite to Coal Combustion Product Leachates. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2018, 144, 04018042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.Y.; Katsumi, T.; Benson, C.H.; Edil, T.B. Hydraulic conductivity and swelling of nonprehydrated GCLs permeated with single-species salt solutions. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2001, 127, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolstad, D.C.; Benson, C.H.; Edil, T.B. Hydraulic conductivity and swell of nonprehydrated geosynthetic clay liners permeated with multispecies inorganic solutions. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2004, 130, 1236–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A.H.; Akar, R.C. Swelling and hydraulic conductivity of bentonites permeated with landfill leachates. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 142, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhl, J.L.; Daniel, D.E. Geosynthetic clay liners permeated with chemical solutions and leachates. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1997, 123, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Li, X.; Luo, J.; Han, R.; Chen, Q.; Shen, D.; Shentu, J. Soil heterogeneity influence on the distribution of heavy metals in soil during acid rain infiltration: Experimental and numerical modeling. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 322, 116144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.C.; Ren, S.X.; Zuo, Q.Q.; Wang, S.T.; Zhou, Y.P.; Liu, W.; Liang, S.X. Effect of nanohydroxyapatite on cadmium leaching and environmental risks under simulated acid rain. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, E.G.; Mazzieri, F.; Verastegui-Flores, R.D.; Van, W.; Bezuijen, A. Polymer-treated bentonite clay for chemical-resistant geosynthetic clay liners. Geosynth. Int. 2015, 22, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Liao, R.P.; Cai, X.Q.; Yu, X. Sodium polyacrylate modification method to improve the permeant performance of bentonite in chemical resistance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prongmanee, N.; Chai, J.C.; Shen, S.L. Hydraulic properties of polymerized bentonites. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.J.; Feng, S.J.; Zheng, Q.T.; Zhang, X.L.; Chen, H.X. Effect of polyanionic cellulose modification on properties and microstructure of calcium bentonite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 228, 106633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Shen, S.Q.; Fu, X.L.; Wang, C.M.; Du, Y.J. Assessment of membrane and diffusion behavior of soil-bentonite slurry trench wall backfill consisted of sand and Xanthan gum amended bentonite. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Ruan, R.; Cui, X. Resource utilization of wastepaper and bentonite: Cu(II) removal in the aqueous environment. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 353, 120213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malusis, M.A.; McKeehan, M.D. Chemical compatibility of model soil-bentonite backfill containing multiswellable bentonite. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2013, 139, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huang, X.-F.; Wang, Z.; Peng, K.-M.; Lu, L.-J.; Liu, J. Composite-polymer modified bentonite enhances anti-seepage and barrier performance under high-concentration heavy-metal solution. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cui, M.; Su, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Huang, R. Preparation of Modified Calcium Bentonite for the Prevention of Heavy Metal Ion Transport in Groundwater. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2020, 81, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokri, M.; Azougagh, O.; El Bojaddayni, I.; Jalafi, I.; Ouardi, Y.E.; Jilal, I.; Ahari, M.; Salhi, A.; El Idrissi, A.; Bendahhou, A.; et al. Progress in bentonite clay modification and enhancing properties to industrial applications: A review. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 337, 130486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagaly, G.; Ziesmer, S. Colloid chemistry of clay minerals: The coagulation of montmorillonite dispersions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 100–102, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olu-Owolabi, B.I.; Unuabonah, E.I. Adsorption of Zn2+ and Cu2+ onto sulphate and phosphate-modified bentonite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2011, 51, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Tareq, A.M.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Khusro, A.; Idrisf, A.M.; Khandakerh, M.U.; Osmani, H.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; et al. Impact of heavy metals on the environment and human health: Novel therapeutic insights to counter the toxicity. J. King Saud Univ.—Sci. 2022, 34, 101865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossini, H.; Shafie, B.; Niri, A.D.; Nazari, M.; Esfahlan, A.J.; Ahmadpour, M.; Nazmara, Z.; Ahmadimanesh, M.; Makhdoumi, P.; Mirzaei, N.; et al. A comprehensive review on human health effects of chromium: Insights on induced toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 70686–70705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, V.; Abern, M.R.; Jagai, J.S.; Kajdacsy-Balla, A. Observational study of the association between air cadmium exposure and prostate cancer aggressiveness at diagnosis among a Nationwide retrospective cohort of 230,540 patients in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, C.G.; Poulsen, A.H.; Eliot, M.; Howe, C.J.; James, K.A.; Harrington, J.M.; Roswall, N.; Overvad, K.; Tjønneland, A.; Raaschou-Nielsen, O.; et al. Urine cadmium and acute myocardial infarction among never smokers in the Danish diet, Cancer and Health cohort. Environ. Int. 2021, 150, 106428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, E.; Botton, J.; Caspersen, I.H.; Alexander, J.; Eggesbø, M.; Haugen, M.; Iszatt, N.; Jacobsson, B.; Knutsen, H.K.; Meltzer, H.M.; et al. Maternal seafood intake during pregnancy, prenatal mercury exposure and child body mass index trajectories up to 8 years. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 1134–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hossain, M.M.A.; Yajima, I.; Tazaki, A.; Xu, H.; Saheduzzaman, M.; Ohgami, N.; Ahsan, N.; Akhand, A.A.; Kato, M. Chromium-mediated hyperpigmentation of skin in male tannery workers in Bangladesh. Chemosphere 2019, 229, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasoy, A.D.; Bilgic, B. Adsorption of copper and zinc ions from aqueous solutions using montmorillonite and bauxite as low-cost adsorbents. Mine Water Environ. 2017, 36, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohdee, K.; Kaewsichan, L. Enhancement of adsorption efficiency of heavy metal Cu(II) and Zn(II) onto cationic surfactant modified bentonite. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2821–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiei, H.R.; Shirvani, M.; Ogunseitan, O.A. Removal of lead from aqueous solutions by a poly(acrylic acid)/bentonite nanocomposite. Appl. Water Sci. 2016, 6, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.G.; Liao, R.P.; Yu, C.; Yu, X. Sorption of Pb (II) on sodium polyacrylate modified bentonite. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 3274–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage, G.; Wickes, B.L.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Inhibition on Candida albicans biofilm formation using divalent cation chelators (EDTA). Mycopathologia 2007, 164, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.G.; Xu, Y.Y.; Yu, H.Q.; Xin, X.D.; Wei, Q.; Du, B. Adsorption of phosphate from aqueous solution by hydroxy-aluminum, hydroxy-iron and hydroxy-iron-aluminum pillared bentonites. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Shi, B.; Ding, J.; Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Qian, J. Preparation and characterization of a nontoxic cross-linked lipase aggregate by using sodium tripolyphosphate and chitosan. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Crini, G.; Lichtfouse, E.; Rhimi, B.; Wang, C. Removal of mercury ions from aqueous solutions by crosslinked chitosan-based adsorbents: A mini review. Chem. Rec. 2020, 20, 1220–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhao, H.; Chen, S.; Long, F.; Huang, B.; Yang, B.; Pan, X. A magnetically recyclable chitosan composite adsorbent functionalized with EDTA for simultaneous capture of anionic dye and heavy metals in complex wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 356, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Hu, L.; Yan, L.; Wei, Q.; Du, B. EDTA functionalized magnetic graphene oxide for removal of Pb(II), Hg(II) and Cu(II) in water treatment: Adsorption mechanism and separation property. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 281, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ.; Alwasel, S.H. Metal Ions, Metal Chelators and Metal Chelating Assay as Antioxidant Method. Processes 2022, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D854; Standard Test Methods for Specific Gravity of Soil Solids by the Water Displacement Method. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM D4546; Standard Test Methods for One-Dimensional Swell or Collapse of Soils. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D698; Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Compaction Characteristics of Soil Using Standard Effort (12,400 ft-lbf/ft3 (600 kN-m/m3)). ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D2216; Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Determination of Water (Moisture) Content of Soil and Rock by Mass. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D4318; Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

- Norris, A.; Aghazamani, N.; Scalia, J.; Shackelford, C.D. Hydraulic performance of geosynthetic clay liners comprising anionic polymer-enhanced bentonites. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2022, 148, 04022023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tan, Y.; Copeland, T.; Chen, J.; Peng, D.; Huang, T. Polymer elution and hydraulic conductivity of polymer-bentonite geosynthetic clay liners to bauxite liquors. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 242, 107039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4646; Standard Test Method for 24-h Batch-Type Measurement of Contaminant Sorption by Soils and Sediments. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM D5084; Standard Test Methods for Measurement of Hydraulic Conductivity of Saturated Porous Materials Using a Flexible Wall Permeameter. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Jo, H.Y.; Benson, C.H.; Edil, T.B. Hydraulic conductivity and cation exchange in non-prehydrated and prehydrated bentonite permeated with weak inorganic salt solutions. Clays Clay Miner. 2004, 52, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3663; Standard Test Method for Surface Area of Catalysts and Catalyst Carriers. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D1993; Standard Test Method for Precipitated Silica-Surface Area by Multipoint BET Nitrogen Adsorption. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- ASTM E168; Standard Practices for General Techniques osf Infrared Quantitative Analysis. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Giles, C.H.; Smith, D.; Huitson, A. A general treatment and classification of the solute adsorption isotherm part. II. Experimental interpretation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1974, 47, 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Benson, C.H.; Peng, D. Hydraulic conductivity of bentonite-polymer composite geosynthetic clay liners permeated with bauxite liquor. Geotext. Geomembr. 2021, 49, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M. The dispersive effect of sodium hexametaphosphate on kaolinite in saline water. Clays Clay Miner. 2024, 60, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, M.A.; Inglezakis, V.J.; Loizidou, M.D.; Agapiou, A.; Itskos, G. Equilibrium ion exchange studies of Zn2+, Cr3+, and Mn2+ on natural bentonite. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 27853–27863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapinar, N.; Donat, R. Adsorption behaviour of Cu2+ and Cd2+ onto natural bentonite. Desalination 2009, 249, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, S.L.; Benson, C.H. Effect of municipal solid waste leachate on hydraulic conductivity and exchange complex of geosynthetic clay liners. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2013, 140, 04013034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyonnet, D.; Touze-Foltz, N.; Norotte, V.; Pothier, C.; Didier, G.; Gailhanou, H.; Blanc, P.; Warmont, F. Performance-based indicators for controlling geosynthetic clay liners in landfill applications. Geotext. Geomembr. 2009, 27, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specific Gravity (Gs) | Free Swell Index (mL/2g) | Free Swell Ratio (%) | Maximum Dry Density (g/cm3) | Natural Moisture Content (%) | Optimum Moisture Content (%) | Liquid Limit (%) | Plastic Limit (%) | Plasticity Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.70 | 31.02 | 365 | 1.583 | 24.65 | 12.52 | 255.77 | 32.45 | 223.29 |

| Complexes | Chemical Formula | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Solubility (25 °C, g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDTA-2Na | C10H14N2Na2O8 | 336.21 | 100 |

| STPP | Na5P3O10 | 367.86 | 140 |

| Leachate Properties | Na+ | K+ | Mg2+ | Ca2+ | Cu2+ | Zn2+ | Al3+ | Cl- | SO42− | pH | I (mM) | RMD (M1/2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 20.1 | 8.48 | 46.9 | 29.8 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 53.7 | 252.35 | 45.55 | 4.85 | 400 | 0.08 |

| Specimen Type | Complex Dosage (%) | Solid-to-Liquid Ratio (g/mL) | Zn(II) Solution Concentration (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na-B+EDTA-2Na | 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 | 1:100 | 0.005, 0.05, 0.5, 5, 50, 100 |

| Na-B+STPP | 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 | 1:100 | 0.005, 0.05, 0.5, 5, 50, 100 |

| Specimen Type | Complexes Dosage (%) | Permeant Solution | Confining Pressure (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na-B+EDTA-2Na Na-B+STPP | 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 | Extreme synthetic leachate | 20 50 100 200 |

| Langmuir Model | Freundlich Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KL (L/mg) | qm (mg/g) | R2 | KF ((μg/g)/(mg/L)) | n | R2 | |

| Na-B | 0.2257 | 20.0966 | 0.9482 | 5.0932 | 3.2286 | 0.9647 |

| Na-B+2%E | 0.4008 | 42.7619 | 0.9940 | 13.6691 | 3.7901 | 0.9184 |

| Na-B+4%E | 0.3495 | 39.1588 | 0.9919 | 12.0715 | 3.6737 | 0.9211 |

| Na-B+6%E | 0.3385 | 35.6036 | 0.9958 | 11.5239 | 3.7796 | 0.8962 |

| Na-B+8%E | 0.3775 | 32.4175 | 0.9949 | 11.1437 | 3.9362 | 0.8688 |

| Na-B+10%E | 0.3443 | 30.1867 | 0.9908 | 10.3702 | 3.8775 | 0.8634 |

| Na-B+2%S | 0.4254 | 32.0048 | 0.9829 | 11.0546 | 3.9454 | 0.8823 |

| Na-B+4%S | 0.4349 | 46.6353 | 0.9920 | 16.1059 | 3.9538 | 0.8822 |

| Na-B+6%S | 0.3565 | 46.0409 | 0.9985 | 14.7489 | 3.7398 | 0.9060 |

| Na-B+8%S | 0.4919 | 35.8673 | 0.9956 | 13.2655 | 4.1727 | 0.8397 |

| Na-B+10%S | 0.2655 | 34.2763 | 0.9936 | 10.5678 | 3.6330 | 0.9041 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Lin, H.; Su, Y.; Tang, S. An Experimental Investigation on the Barrier Performance of Complex-Modified Bentonite. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010299

Xu J, Lin H, Su Y, Tang S. An Experimental Investigation on the Barrier Performance of Complex-Modified Bentonite. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):299. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010299

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jiangdong, Hai Lin, Youshan Su, and Shanke Tang. 2026. "An Experimental Investigation on the Barrier Performance of Complex-Modified Bentonite" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010299

APA StyleXu, J., Lin, H., Su, Y., & Tang, S. (2026). An Experimental Investigation on the Barrier Performance of Complex-Modified Bentonite. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010299