Towards a Circular Phosphorus Economy: Electroless Struvite Precipitation from Cheese Whey Wastewater Using Magnesium Anodes

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cheese Whey Wastewater and Chemicals

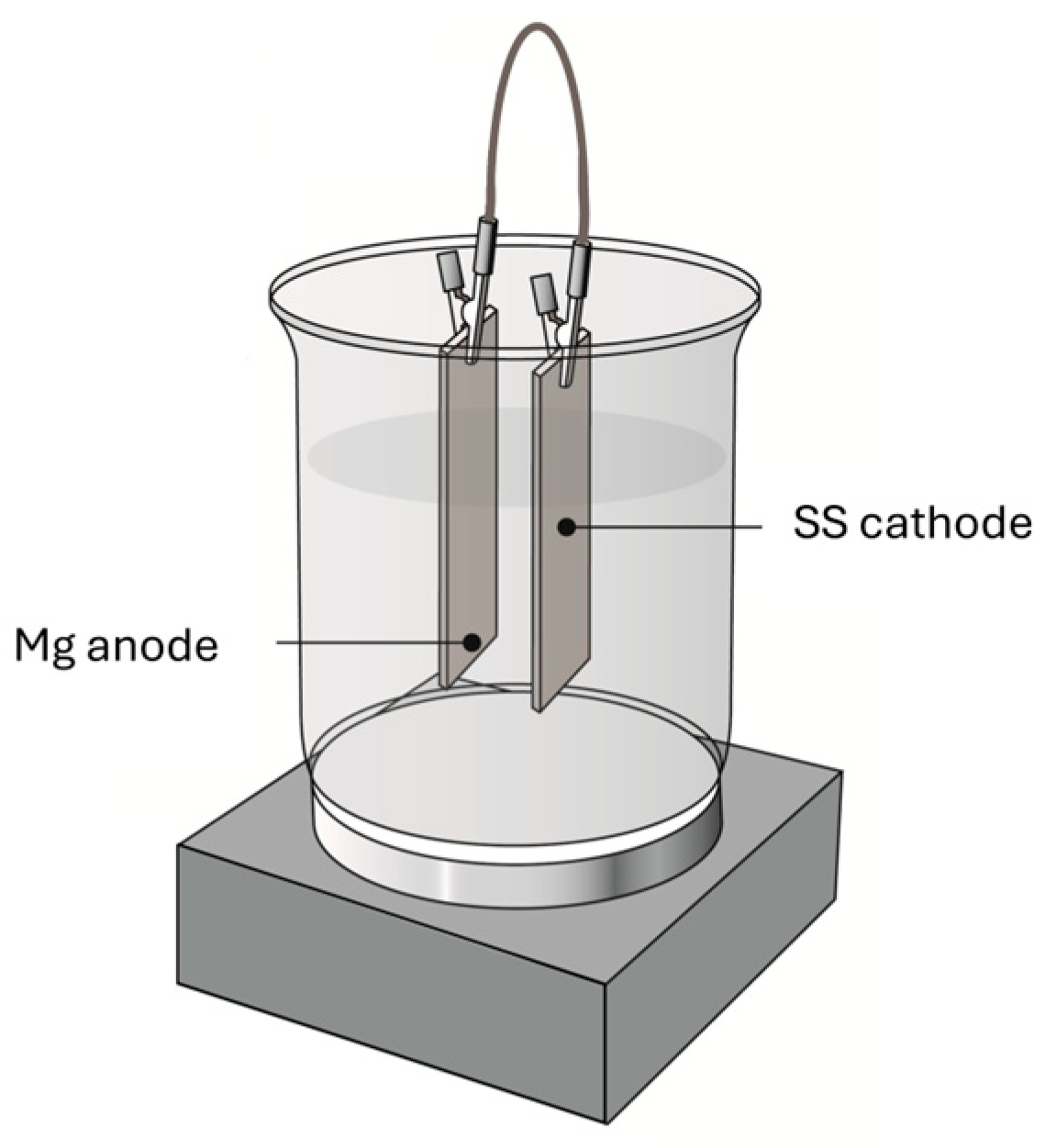

2.2. Electrochemical Experiments

2.3. Analytical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

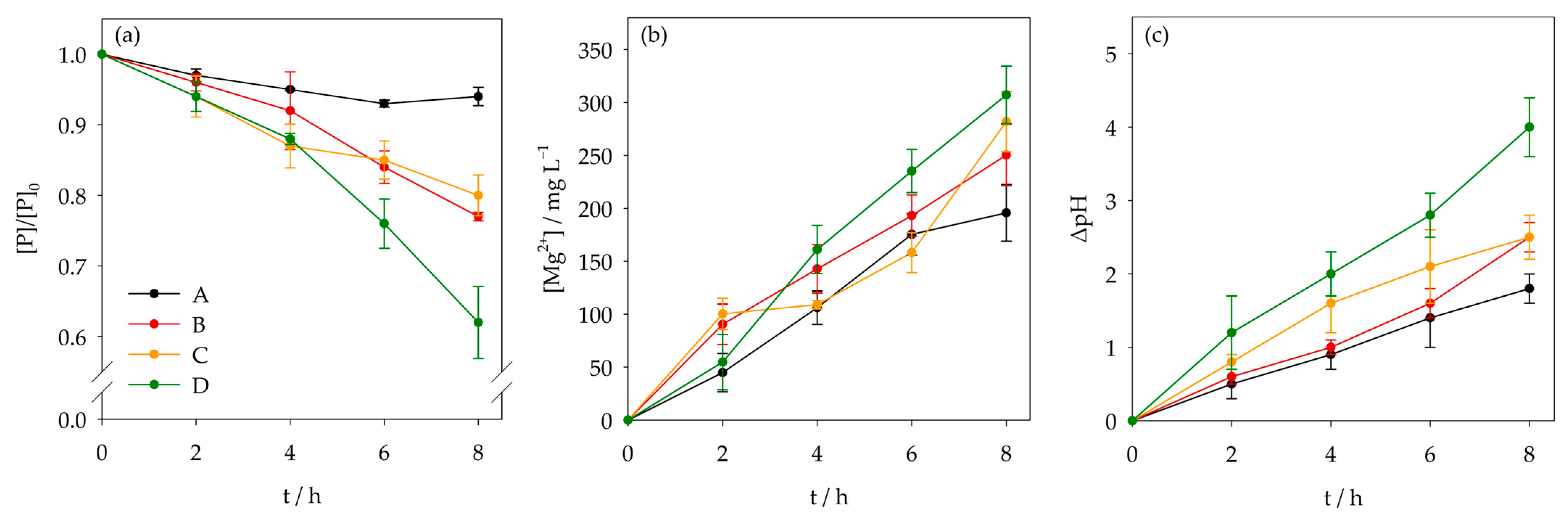

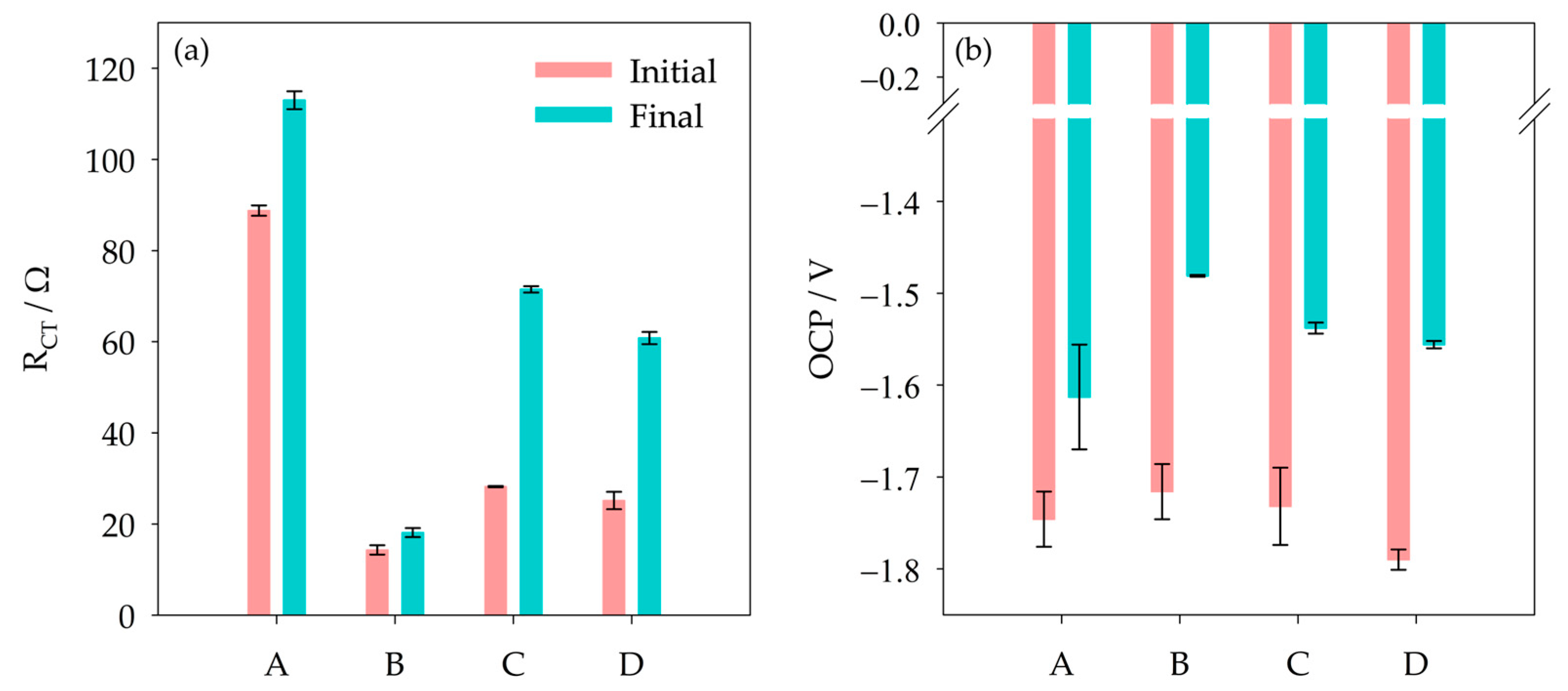

3.1. Effect of Chloride and Sulfate

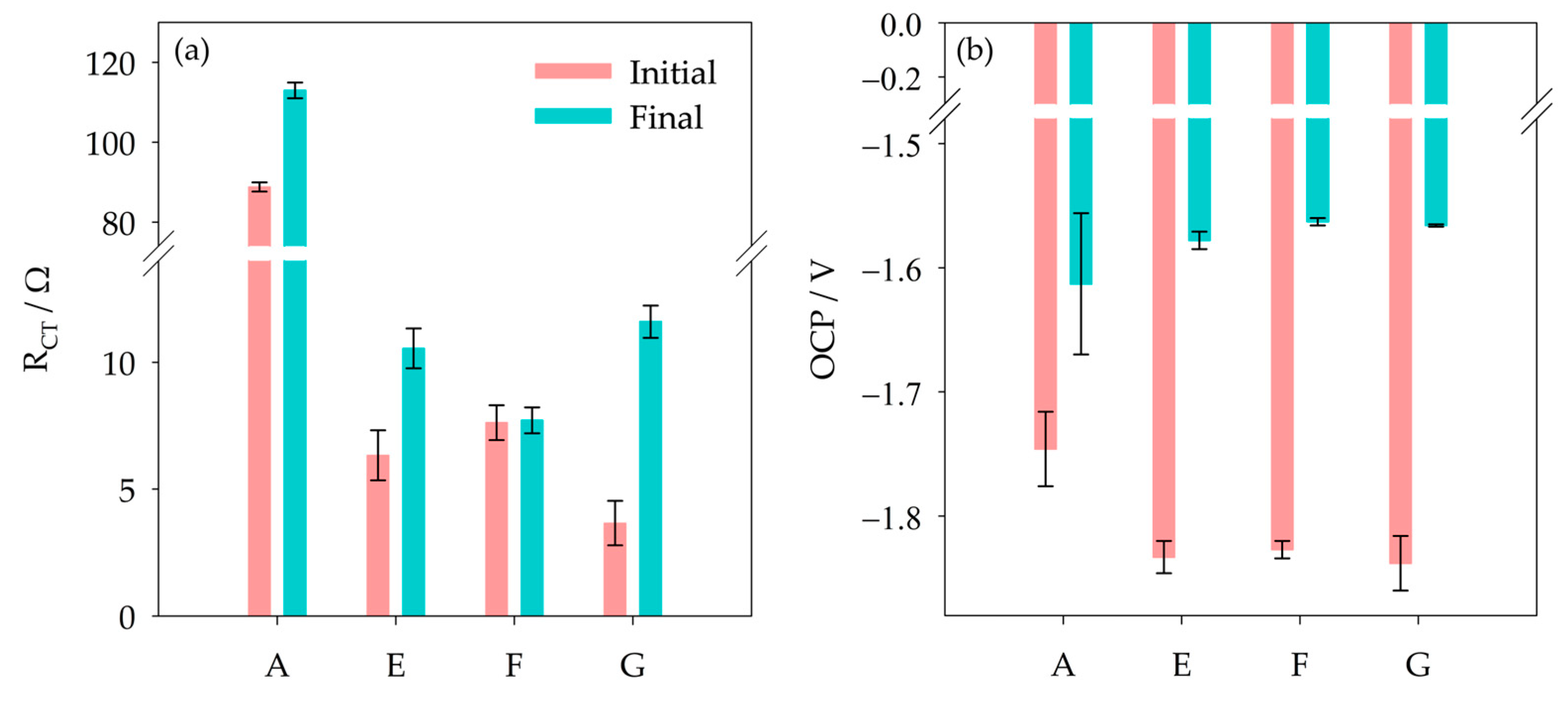

3.2. Effect of Ammonium

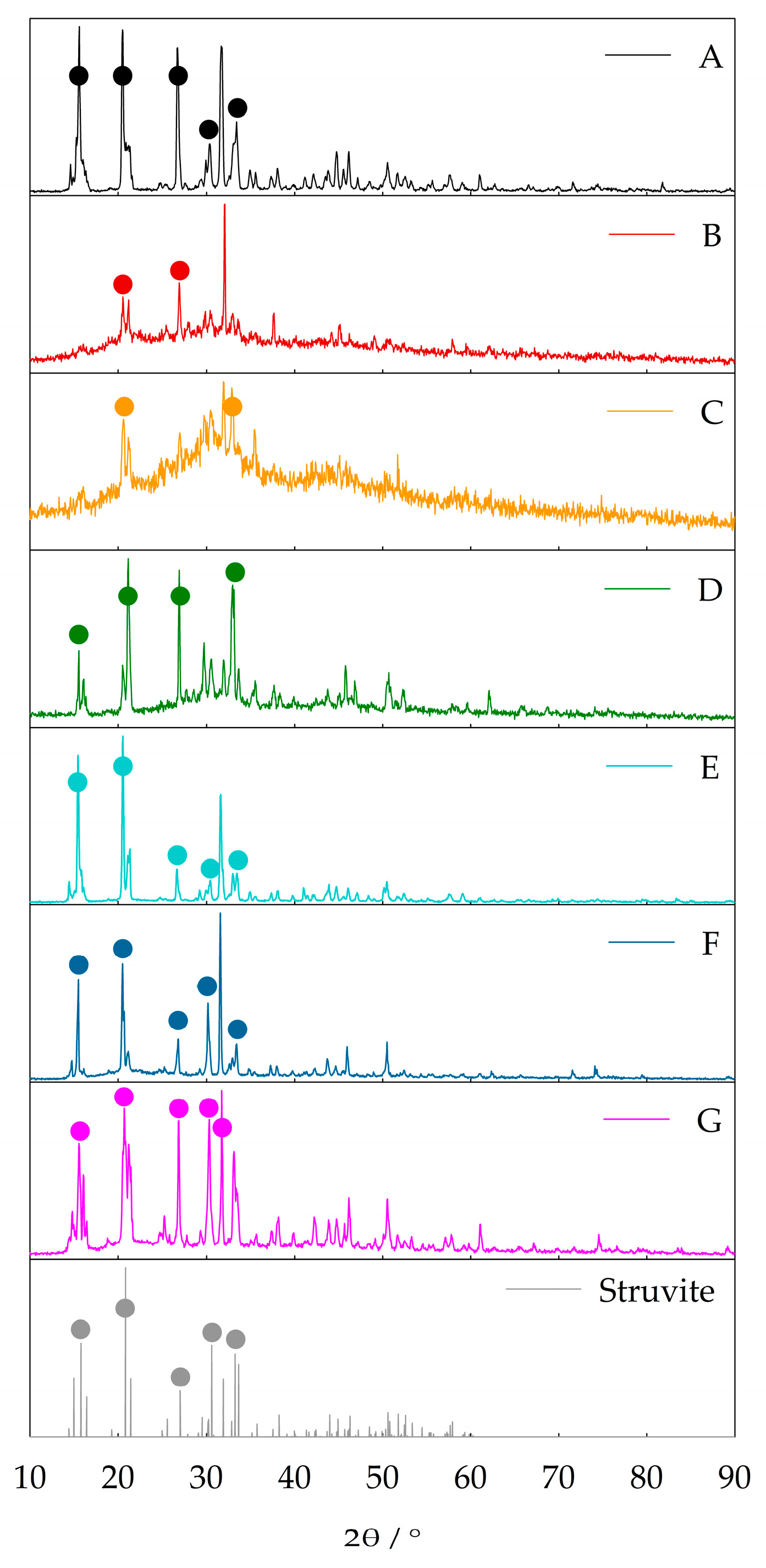

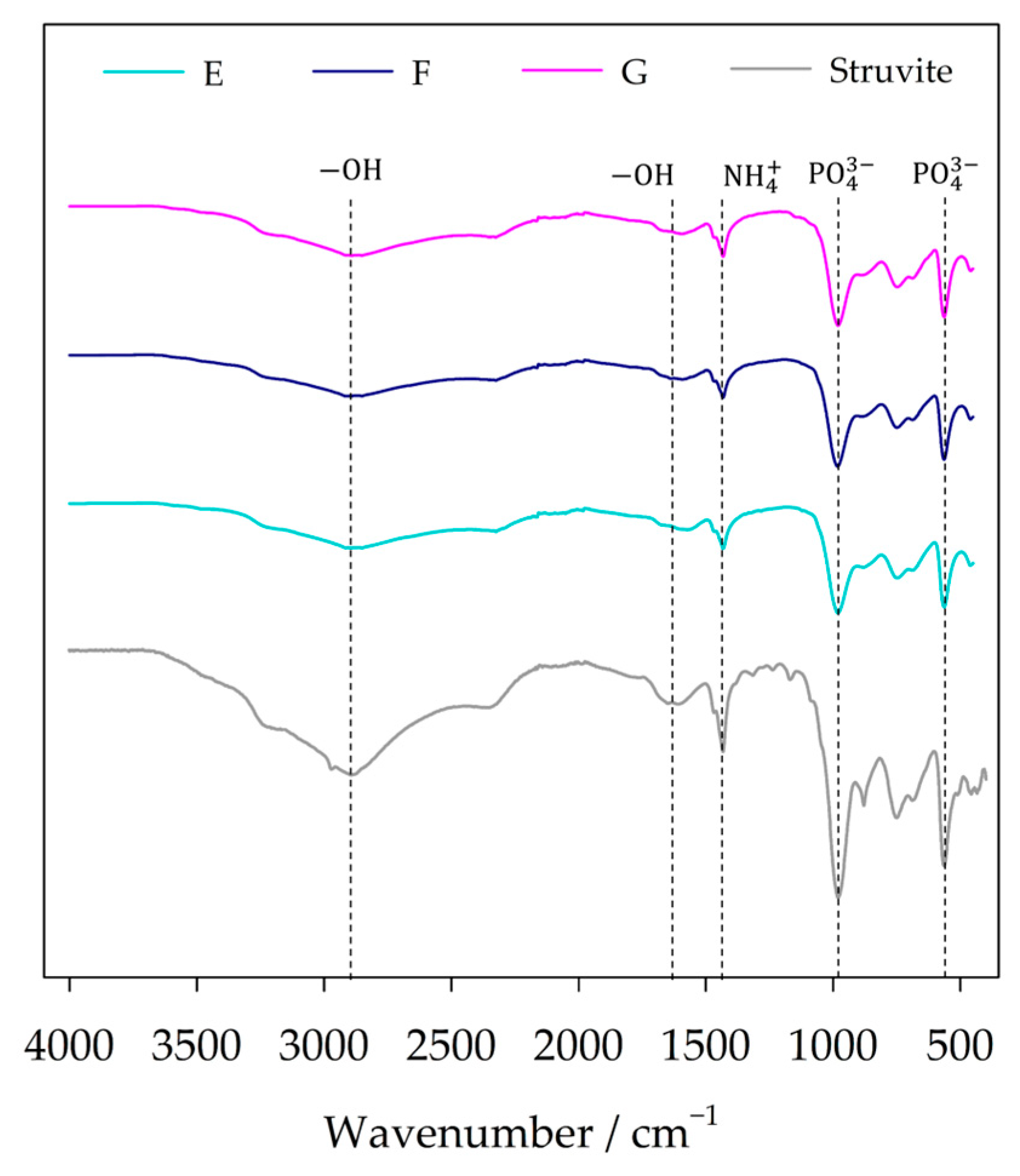

3.3. Solids Characterization

3.4. Economic Assessment

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| AZ31 | Magnesium (96%) alloy with aluminum (3%) and zinc (1%) |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| DIC | Dissolved inorganic carbon |

| DOC | Dissolved organic carbon |

| EIS | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| OCP | Open circuit potential |

| RCT | Charge transfer resistance |

| RPL | Passivation layer resistance |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SS | Stainless-steel |

| TDN | Total dissolved nitrogen |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Cordell, D.; Rosemarin, A.; Schröder, J.J.; Smit, A.L. Towards Global Phosphorus Security: A Systems Framework for Phosphorus Recovery and Reuse Options. Chemosphere 2011, 84, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erisman, J.W.; Sutton, M.A.; Galloway, J.; Klimont, Z.; Winiwarter, W. How a Century of Ammonia Synthesis Changed the World. Nat. Geosci. 2008, 1, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, T.S.; Moreira, F.S.; Cabral, B.V.; Dantas, R.C.C.; Resende, M.M.; Cardoso, V.L.; Ribeiro, E.J. Phosphorus Recovery from Phosphate Rocks Using Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria. Geomicrobiol. J. 2019, 36, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edixhoven, J.D.; Gupta, J.; Savenije, H.H.G. Recent Revisions of Phosphate Rock Reserves and Resources: A Critique. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2014, 5, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, J.R.; Fantel, R.J. Phosphate Rock Demand into the next Century: Impact on World Food Supply. Nat. Resour. Res. 1993, 2, 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisinyo, P.O.; Opala, P.A. Depletion of Phosphate Rock Reserves and World Food Crisis: Reality or Hoax? Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 16, 1223–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, M.; Arnaudguilhem, C.; El Samad, O.; Khozam, R.B.; Lobinski, R. Impact of a Phosphate Fertilizer Plant on the Contamination of Marine Biota by Heavy Elements. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 14940–14949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hug, A.; Udert, K.M. Struvite Precipitation from Urine with Electrochemical Magnesium Dosage. Water Res. 2013, 47, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Zhan, Z.; Saakes, M.; van der Weijden, R.D.; Buisman, C.J.N. Electrochemical Recovery of Phosphorus from Acidic Cheese Wastewater: Feasibility, Quality of Products, and Comparison with Chemical Precipitation. ACS ES T Water 2022, 1, 1002–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aka, R.J.N.; Hossain, M.; Yuan, Y.; Agyekum-Oduro, E.; Zhan, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wu, S. Nutrient Recovery through Struvite Precipitation from Anaerobically Digested Poultry Wastewater in an Air-Lift Electrolytic Reactor: Process Modeling and Cost Analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 465, 142825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Anand, D.; He, Z. Phosphorus Recovery from Whole Digestate through Electrochemical Leaching and Precipitation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 10107–10116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomei, M.C.; Stazi, V.; Daneshgar, S.; Capodaglio, A.G. Holistic Approach to Phosphorus Recovery from Urban Wastewater: Enhanced Biological Removal Combined with Precipitation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L. Recovery of Phosphorus in Wastewater in the Form of Polyphosphates: A Review. Processes 2022, 10, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kuntke, P.; Saakes, M.; van der Weijden, R.D.; Buisman, C.J.N.; Lei, Y. Electrochemically Mediated Precipitation of Phosphate Minerals for Phosphorus Removal and Recovery: Progress and Perspective. Water Res. 2022, 209, 117891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Zheng, W.; Duan, X.; Goswami, N.; Liu, Y. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Removal and Recovery of Phosphorus from Water: A Review. Environ. Funct. Mater. 2022, 1, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockhorn, T. About the Economy of Phosphorus Recovery. In International Conference on Nutrient Recovery from Wastewater Streams; Ashley, K., Mavinic, D., Koch, F., Eds.; IWA Publishing: Vancouver, BC, USA, 2009; pp. 145–158. ISBN 9781780401805. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, M.; Pan, Y.; Li, D.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, L.; Song, Z.; Zhao, Y. Metagenomics Reveals the Metabolism of Polyphosphate-Accumulating Organisms in Biofilm Sequencing Batch Reactor: A New Model. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 360, 127603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zhang, J.; Ni, M.; Pan, Y. Phosphate Recovery from Urban Sewage by the Biofilm Sequencing Batch Reactor Process: Key Factors in Biofilm Formation and Related Mechanisms. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.Y.; Fernandes, A.; Amaro, A.; Pacheco, M.J.; Ciríaco, L.; Lopes, A. Electrochemical Recovery of Phosphorus from Simulated and Real Wastewater: Effect of Investigational Conditions on the Process Efficiency. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, D.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Degryse, F. Efficacy of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles as Phosphorus Fertilizer in Andisols and Oxisols. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2015, 79, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Piqueres, A.; Ribó, M.; Rodríguez-Carretero, I.; Quiñones, A.; Canet, R. Struvite as a Sustainable Fertilizer in Mediterranean Soils. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford-Hartke, Z.; Razmjou, A.; Gregory, L. Factors Affecting Phosphorus Recovery as Struvite: Effects of Alternative Magnesium Sources. Desalination 2021, 504, 114949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; She, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Xiang, P.; Xia, S. Electrochemical Acidolysis of Magnesite to Induce Struvite Crystallization for Recovering Phosphorus from Aqueous Solution. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Fang, Y.; Song, L.; Niu, Q. Production of Struvite by Magnesium Anode Constant Voltage Electrolytic Crystallisation from Anaerobically Digested Chicken Manure Slurry. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B.; Wang, R.; Li, W.; Zhan, Z.; Luo, J.; Lei, Y. Fate of Micropollutants in Struvite Production from Swine Wastewater with Sacrificial Magnesium Anode. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, Y. An Integrated Process for Struvite Electrochemical Precipitation and Ammonia Oxidation of Sludge Alkaline Hydrolysis Supernatant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 2435–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, I.B.; Singh, M.; Das, S. A Comparative Corrosion Behavior of Mg, AZ31 and AZ91 Alloys in 3.5% NaCl Solution. J. Magnes. Alloys 2015, 3, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kékedy-Nagy, L.; Abolhassani, M.; Perez Bakovic, S.I.; Anari, Z.; Moore, J.P.; Pollet, B.G.; Greenlee, L.F. Electroless Production of Fertilizer (Struvite) and Hydrogen from Synthetic Agricultural Wastewaters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 18844–18858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kékedy-Nagy, L.; Morrissey, K.G.; Anari, Z.; Daneshpour, R.; Greenlee, L.F.; Thoma, G. Sustainable Electroless Nutrient Recovery from Natural Agro-Industrial and Livestock Farm Wastewater Effluents with a Flow Cell Reactor. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.Y.; Gomes, I.; Amaro, A.; Fernandes, A. Phosphorus Recovery from Industrial Effluents through Chemical and Electrochemical Precipitation: A Critical Review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 24, 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kékedy-Nagy, L.; English, L.; Anari, Z.; Abolhassani, M.; Pollet, B.G.; Popp, J.; Greenlee, L.F. Electrochemical Nutrient Removal from Natural Wastewater Sources and Its Impact on Water Quality. Water Res. 2022, 210, 118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsi, P.D.; Koutsoukos, P.G. Electrochemical Recovery of N and P from Municipal Wastewater. Crystals 2024, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Zhang, T.; Wan, D.; Xie, Y. Electrochemical Impedance Sensor Based on Nano-Cobalt-Oxide-Modified Graphenic Electrode for Total Phosphorus Determinations in Water. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 2635–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotta, E.H.; Martí-Calatayud, M.C.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; Bernardes, A.M. Evaluation by Means of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy of the Transport of Phosphate Ions through a Heterogeneous Anion-Exchange Membrane at Different PH and Electrolyte Concentration. Water 2022, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Qiao, J.; Zheng, W.; Lei, Y.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Y. Flow-through Electrochemical Organophosphorus Degradation and Phosphorus Recovery: The Essential Role of Chlorine Radical. Environ. Res. 2023, 236, 116867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Li, J.; Qu, W.; Wang, W.; Ma, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S. Enhancing Electrochemical Crystallization for Phosphate Recovery from Swine Wastewater by Alternating Pulse Current. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 59, 104918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kékedy-Nagy, L.; Teymouri, A.; Herring, A.M.; Greenlee, L.F. Electrochemical Removal and Recovery of Phosphorus as Struvite in an Acidic Environment Using Pure Magnesium vs. the AZ31 Magnesium Alloy as the Anode. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 380, 122480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kékedy-Nagy, L.; Moore, J.P.; Abolhassani, M.; Attarzadeh, F.; Hestekin, J.A.; Greenlee, L.F. The Passivating Layer Influence on Mg-Based Anode Corrosion and Implications for Electrochemical Struvite Precipitation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, E358–E364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuess, L.T.; Garcia, M.L. Implications of Stillage Land Disposal: A Critical Review on the Impacts of Fertigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Burgos, W.J.; Bittencourt Sydney, E.; Bianchi Pedroni Medeiros, A.; Magalhães, A.I.; de Carvalho, J.C.; Karp, S.G.; Porto de Souza Vandenberghe, L.; Junior Letti, L.A.; Thomaz Soccol, V.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; et al. Agro-Industrial Wastewater in a Circular Economy: Characteristics, Impacts and Applications for Bioenergy and Biochemicals. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association; American Water Works Association; Water Environment Federation. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 24th ed.; Lipps, W.C., Braun-Howland, E.B., Baxter, T.E., Eds.; APHA Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Wang, Z.; You, S.; Liu, Y. Electrogenerated Quinone Intermediates Mediated Peroxymonosulfate Activation toward Effective Water Decontamination and Electrode Antifouling. Appl. Catal. B 2023, 320, 121980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazanas, A.C.; Prodromidis, M.I. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy─A Tutorial. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2023, 3, 162–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Medhekar, N.V.; Frankel, G.S.; Birbilis, N. Corrosion Mechanism and Hydrogen Evolution on Mg. Curr. Opin. Solid. State Mater. Sci. 2015, 19, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunold, R.; Holtan, H.; Berge, M.-B.H.; Lasson, A.; Steen-Hansen, R. The Corrosion of Magnesium in Aqueous Solution Containing Chloride Ions. Corros. Sci. 1977, 17, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-W.; Lin, H.; Huang, C.-Y.; Shi, C.-H.; Lin, C.-S. The Initial Corrosion Behavior of AZ31B Magnesium Alloy in Chloride and Sulfate Solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 081504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wei, Y.; Hou, L.; Zhang, D. Corrosion Behaviour of Die-Cast AZ91D Magnesium Alloy in Aqueous Sulphate Solutions. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Morales, C.; Fernández, B.; Molina, F.J.; Naranjo-Fernández, D.; Matamoros-Veloza, A.; Camargo-Valero, M.A. Influence of PH and Temperature on Struvite Purity and Recovery from Anaerobic Digestate. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mallahi, J.; Sürmeli, R.Ö.; Çalli, B. Recovery of Phosphorus from Liquid Digestate Using Waste Magnesite Dust. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ye, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, Z.L.; Chen, S. Selection of Cost-Effective Magnesium Sources for Fluidized Struvite Crystallization. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 70, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Mohammed, A.N.; Liu, Y. Phosphorus Recovery from Source-Diverted Blackwater through Struvite Precipitation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, C.; Tang, Q.-L.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Chen, F. Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Rapid Synthesis of Hydroxyapatite Nanowires Using Adenosine 5′-Triphosphate Disodium Salt as Phosphorus Source. Mater. Lett. 2012, 85, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Zeng, G.; Song, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S. Ultrasonic Power Combined with Seed Materials for Recovery of Phosphorus from Swine Wastewater via Struvite Crystallization Process. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Liu, F.; Gao, X.; Zhai, Z.; Li, J.; Du, L. Simultaneous Recovery of Ammonium and Phosphate from Aqueous Solutions Using Mg/Fe Modified NaY Zeolite: Integration between Adsorption and Struvite Precipitation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 299, 121713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heraldy, E.; Rahmawati, F.; Heriyanto; Putra, D.P. Preparation of Struvite from Desalination Waste. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 1666–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorczuk, D.; Kozanecki, M.; Civalleri, B.; Pernal, K.; Prywer, J. Structural and Optical Properties of Struvite. Elucidating Structure of Infrared Spectrum in High Frequency Range. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 8668–8678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, R.C.d.S.; da Paz, S.P.A.; Corrêa, J.A.M. XRD-Rietveld Analysis as a Tool for Monitoring Struvite Analog Precipitation from Wastewater: P, Mg, N and K Recovery for Fertilizer Production. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 15202–15213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, S.; Sayan, P. Preparation, Characterization and Kinetic Evaluation of Struvite in Various Carboxylic Acids. J. Cryst. Growth 2020, 531, 125339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindhu, B.; Swetha, A.S.; Veluraja, K. Studies on the Effect of Phyllanthus Emblica Extract on the Growth of Urinary Type Struvite Crystals Invitro. Clin. Phytoscience 2015, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Shih, K. Effects of Calcium and Ferric Ions on Struvite Precipitation: A New Assessment Based on Quantitative X-Ray Diffraction Analysis. Water Res. 2016, 95, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouff, A.A. Sorption of Chromium with Struvite During Phosphorus Recovery. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 12493–12501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Sun, B.; Zhao, H.; Yan, H.; Han, M.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, R.; Zhuang, D.; Li, D.; Ma, Y.; et al. Isolation of Leclercia adcarboxglata Strain JLS1 from Dolostone Sample and Characterization of Its Induced Struvite Minerals. Geomicrobiol. J. 2017, 34, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Tucker, M.; Han, Z.; Yan, H. Bio-Precipitation of Carbonate and Phosphate Minerals Induced by the Bacterium Citrobacter Freundii ZW123 in an Anaerobic Environment. Minerals 2020, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, H.; Hantoko, D.; Wen, X.; Kanchanatip, E.; Yan, M. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Recovery from Sludge Treatment by Supercritical Water Gasification Coupled with Struvite Crystallization. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 55, 104070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, L.; Kirwan, K.; Alibardi, L.; Pidou, M.; Coles, S.R. Recovery of Ammonia from Wastewater through Chemical Precipitation. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 142, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muys, M.; Phukan, R.; Brader, G.; Samad, A.; Moretti, M.; Haiden, B.; Pluchon, S.; Roest, K.; Vlaeminck, S.E.; Spiller, M. A Systematic Comparison of Commercially Produced Struvite: Quantities, Qualities and Soil-Maize Phosphorus Availability. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ye, C.; Gao, B.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Ding, K.; Li, H.; Ren, K.; Chen, S.; Wang, W.; et al. Applying Struvite as a N-Fertilizer to Mitigate N2O Emissions in Agriculture: Feasibility and Mechanism. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 330, 117143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, Z. Electrochemical Phosphorus Leaching from Digested Anaerobic Sludge and Subsequent Nutrient Recovery. Water Res. 2022, 223, 118996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Du, M.; Kuntke, P.; Saakes, M.; Van Der Weijden, R.; Buisman, C.J.N. Energy Efficient Phosphorus Recovery by Microbial Electrolysis Cell Induced Calcium Phosphate Precipitation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 8860–8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoi, G.P.; Singh, K.S.; Connor, D.A. Optimization of Phosphorus Recovery Using Electrochemical Struvite Precipitation and Comparison with Iron Electrocoagulation System. Water Environ. Res. 2023, 95, e10847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, R.; Greenlee, L.F. The Implications of Pulsating Anode Potential on the Electrochemical Recovery of Phosphate as Magnesium Ammonium Phosphate Hexahydrate (Struvite). Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 459, 141522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, Á.; Vinardell, S.; Ganesan, K.; Bacardí, C.; Cortina, J.L.; Valderrama, C. Life-Cycle Assessment and Techno-Economic Evaluation of the Value Chain in Nutrient Recovery from Wastewater Treatment Plants for Agricultural Application. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Mean Value (±SD) |

|---|---|

| pH | 5.4 ± 0.3 |

| Electrical conductivity/mS cm−1 | 2.24 ± 0.06 |

| Chemical oxygen demand/g L−1 | 5.86 ± 0.05 |

| Total dissolved carbon/g L−1 | 1.44 ± 0.03 |

| Organic dissolved carbon/g L−1 | 1.42 ± 0.03 |

| Inorganic dissolved carbon/mg L−1 | 20 ± 1 |

| Total phosphorus/mg L−1 | 200 ± 5 |

| Dissolved orthophosphate/mgP-PO43− L−1 | 201 ± 3 |

| Total dissolved nitrogen/mg L−1 | 149 ± 6 |

| Magnesium/mg L−1 | <0.5 |

| Experiment | Salt Added | Concentration/mM |

|---|---|---|

| A | – | – |

| B | KCl | 90.0 ± 0.7 |

| C | K2SO4 | 45.0 ± 0.4 |

| D | K2SO4 | 90.0 ± 0.7 |

| E | CH3COONH4 | 90.0 ± 0.7 |

| F | NH4Cl | 90.0 ± 0.7 |

| G | (NH4)2SO4 | 45.0 ± 0.4 |

| Product | Energy Cost a/€ kgP−1 | Mg Cost/€ kgP−1 | Mg Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium phosphates | 24.86 | – | – | [11] |

| 68.76 | – | – | [68] | |

| 6.30 | – | – | [69] | |

| Struvite | 0.79 | 34.47 | AZ31 | [8] |

| 0.00 | 7.13 | MgO | [8] | |

| 0.00 | 53.88 | MgCl2 | [8] | |

| 0.00 | 27.33 | MgSO4 | [8] | |

| 1.95 | NR b | Mg | [70] | |

| 7.53 | NR b | Mg | [71] | |

| 1.13 | NR b | Mg | [26] | |

| 0.00 | 25.51–63.78 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fernandes, V.B.; Farinon, D.M.; Fernandes, A.; Silveira, J.E.; Amaro, A.; Zazo, J.A.; Sousa, C.Y. Towards a Circular Phosphorus Economy: Electroless Struvite Precipitation from Cheese Whey Wastewater Using Magnesium Anodes. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010298

Fernandes VB, Farinon DM, Fernandes A, Silveira JE, Amaro A, Zazo JA, Sousa CY. Towards a Circular Phosphorus Economy: Electroless Struvite Precipitation from Cheese Whey Wastewater Using Magnesium Anodes. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):298. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010298

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernandes, Vasco B., Daliany M. Farinon, Annabel Fernandes, Jefferson E. Silveira, Albertina Amaro, Juan A. Zazo, and Carlos Y. Sousa. 2026. "Towards a Circular Phosphorus Economy: Electroless Struvite Precipitation from Cheese Whey Wastewater Using Magnesium Anodes" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010298

APA StyleFernandes, V. B., Farinon, D. M., Fernandes, A., Silveira, J. E., Amaro, A., Zazo, J. A., & Sousa, C. Y. (2026). Towards a Circular Phosphorus Economy: Electroless Struvite Precipitation from Cheese Whey Wastewater Using Magnesium Anodes. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010298