A Stress-Relief Concept and Its Energy-Dissipating Support for High-Stress Soft-Rock Tunnels

Abstract

1. Introduction

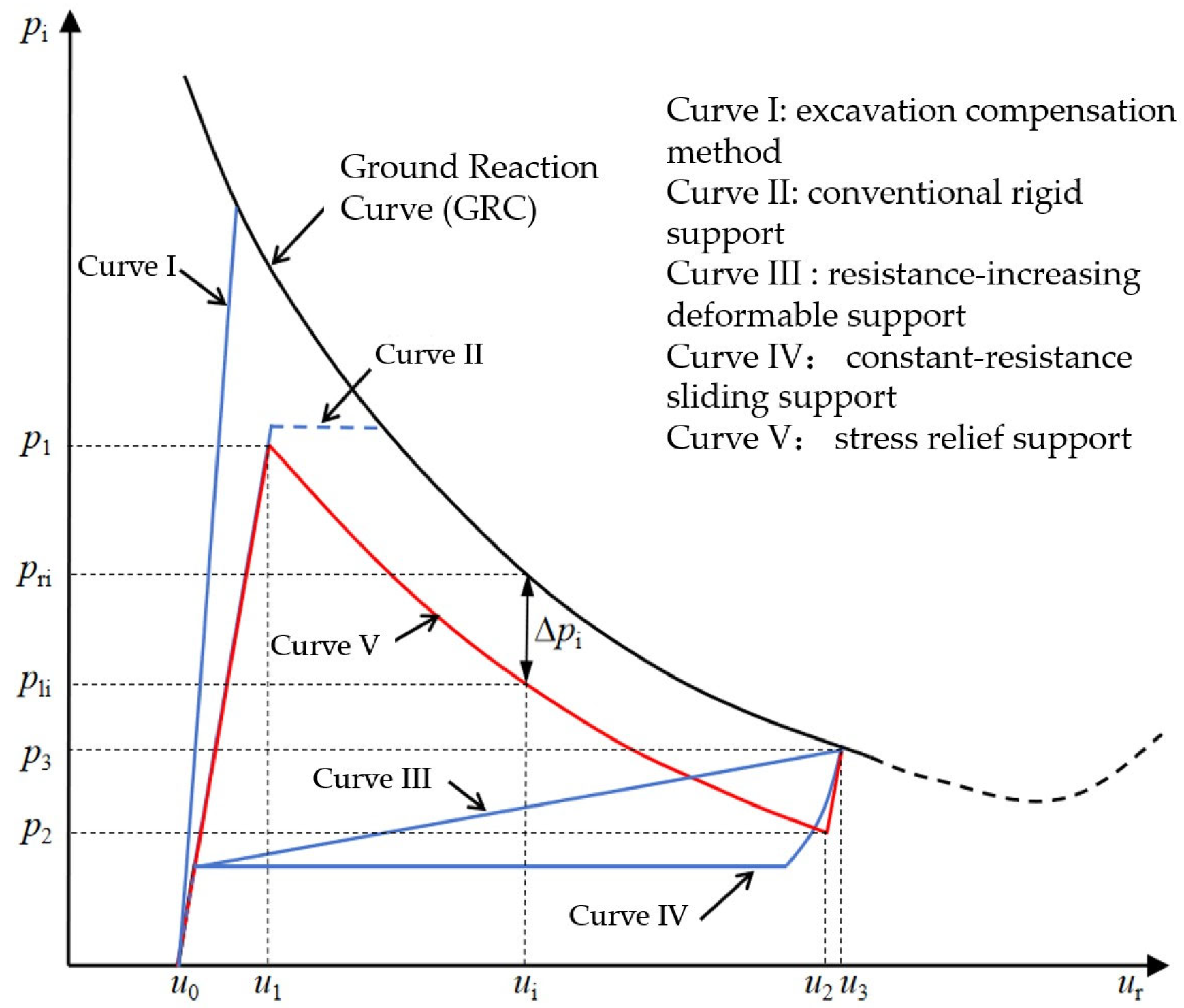

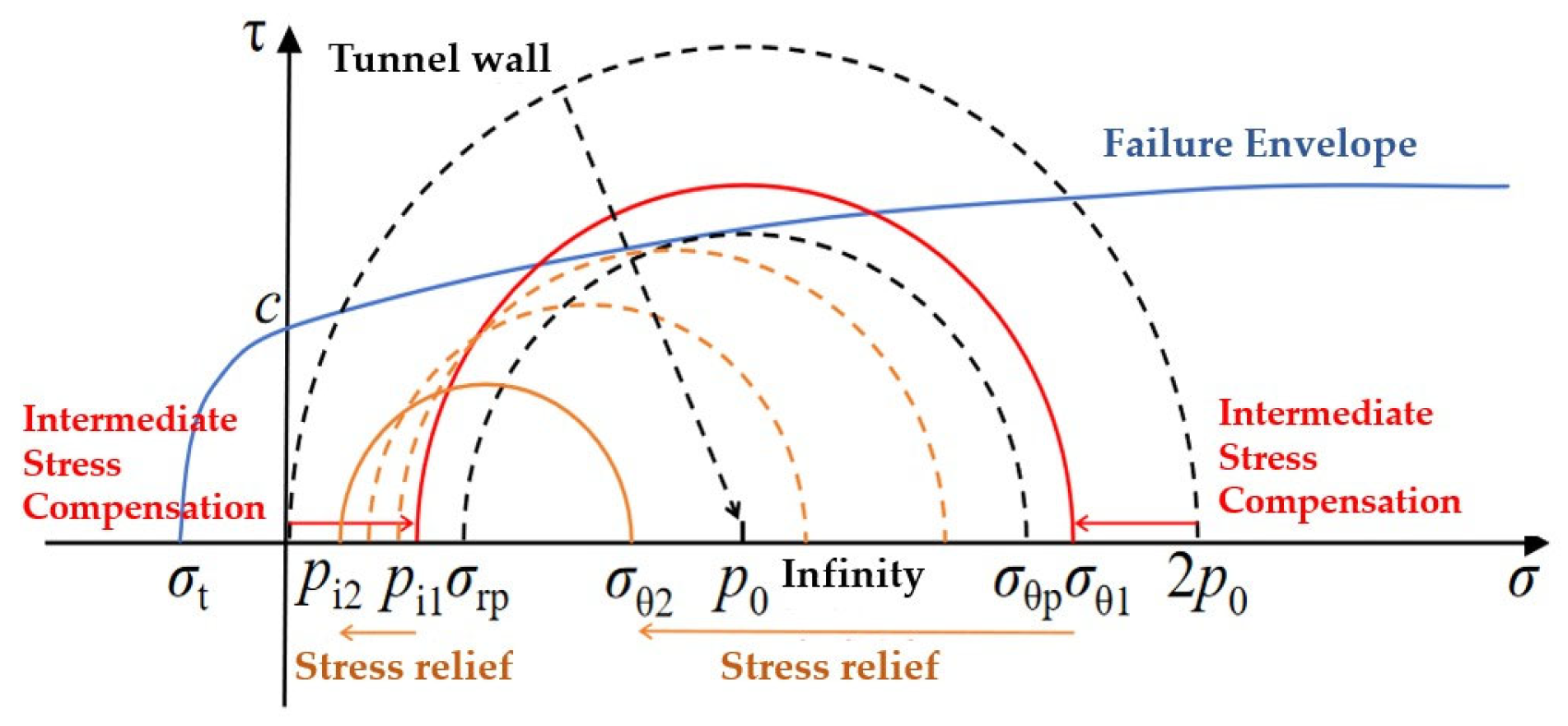

2. Stress-Relief Concept for Surrounding Rock in High In Situ Stress Tunnels

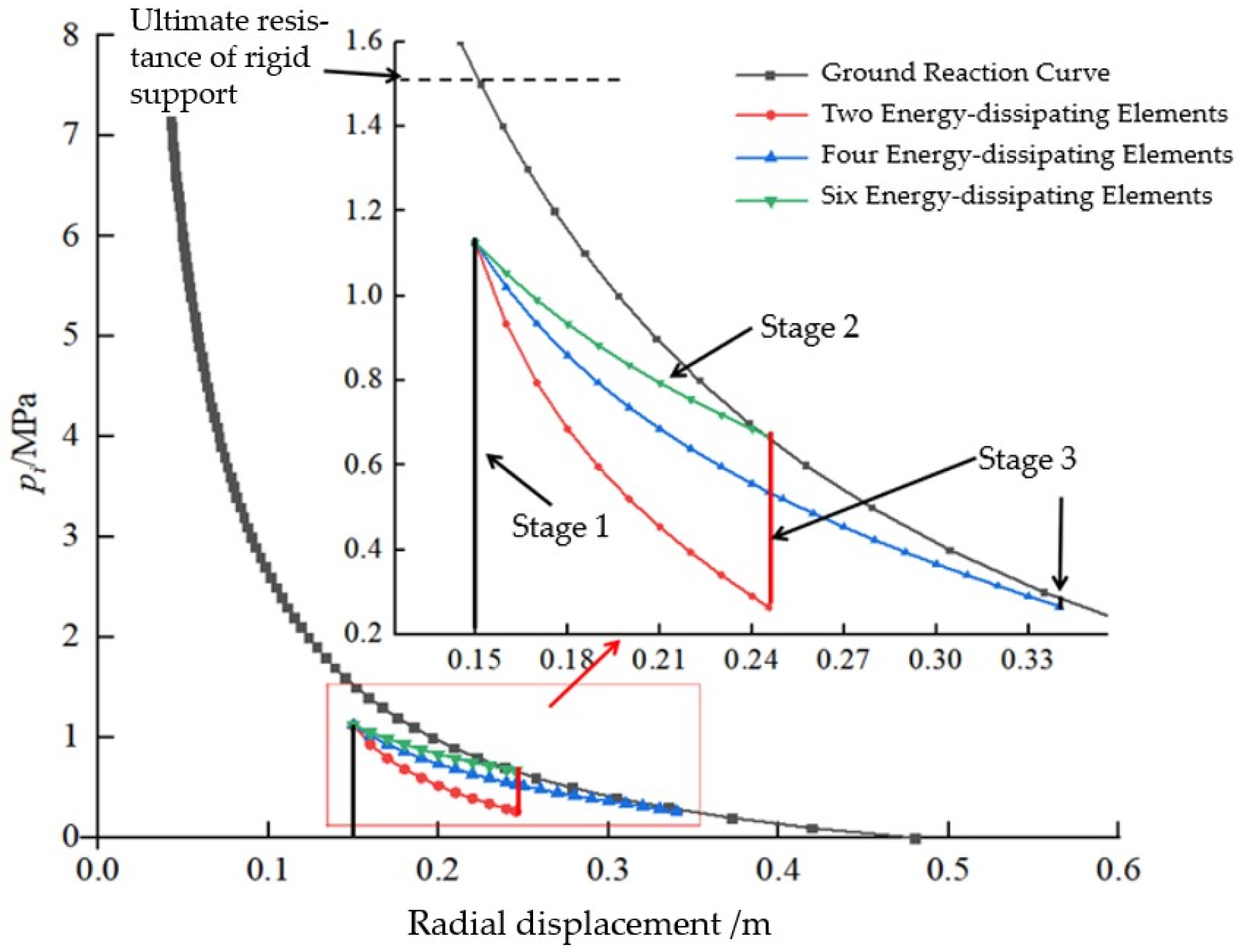

2.1. Fundamentals of the Stress-Relief Control Concept

- A high initial stiffness stage, suppressing rapid loosening of the surrounding rock;

- A moderate stress-relief stage, guiding gradual energy release and controlling the deformation rate;

- A final re-stiffening stage, promoting deformation convergence and providing structural redundancy.

2.2. Elastoplastic Solution of the Surrounding Rock–Support System Under the Stress-Relief Control Concept

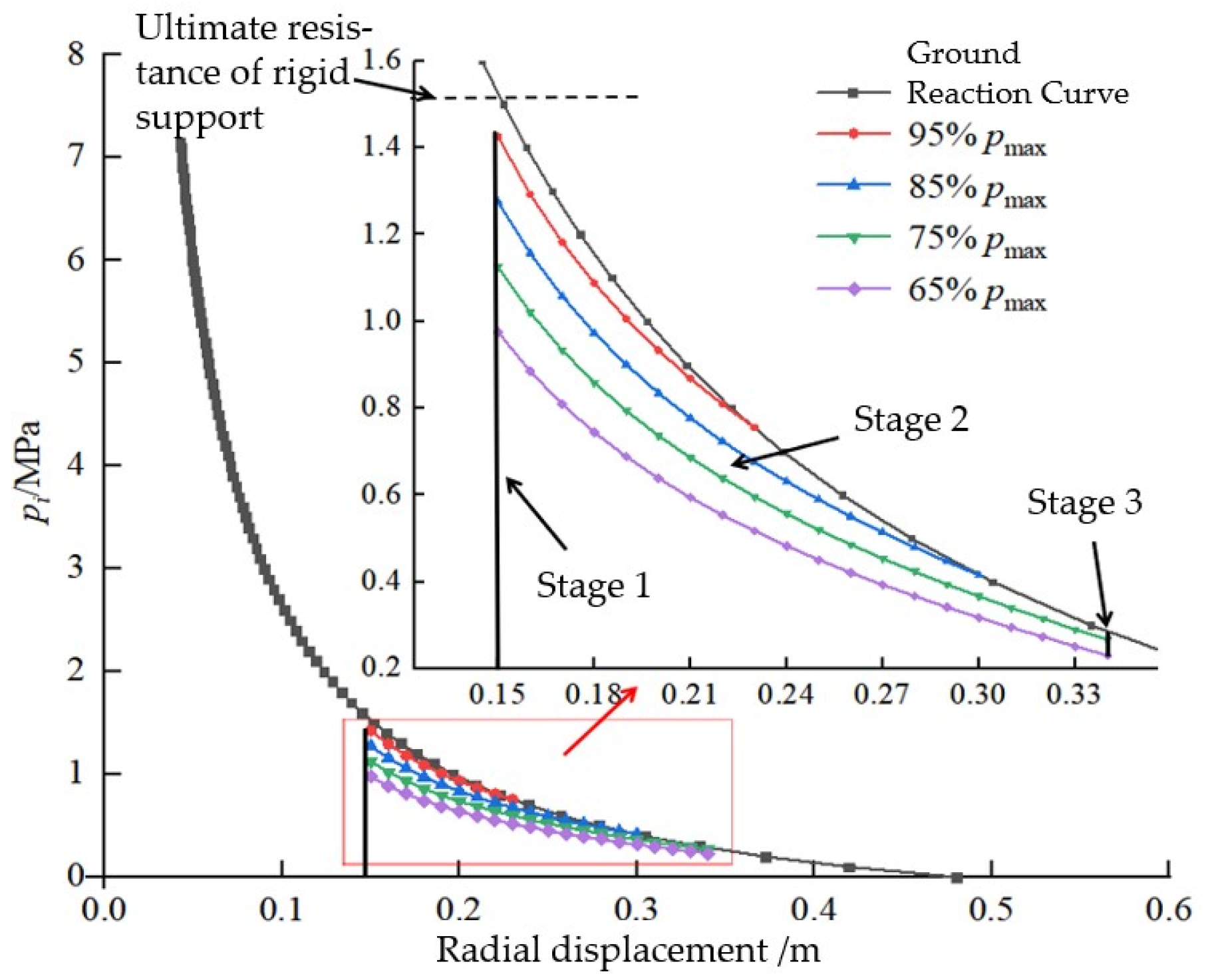

2.3. Influence of Stress-Relief Support Parameters on Tunnel Control Performance

2.3.1. Influence of Peak Resistance on Support Performance

2.3.2. Influence of the Number of Stress-Relief Elements on Support Performance

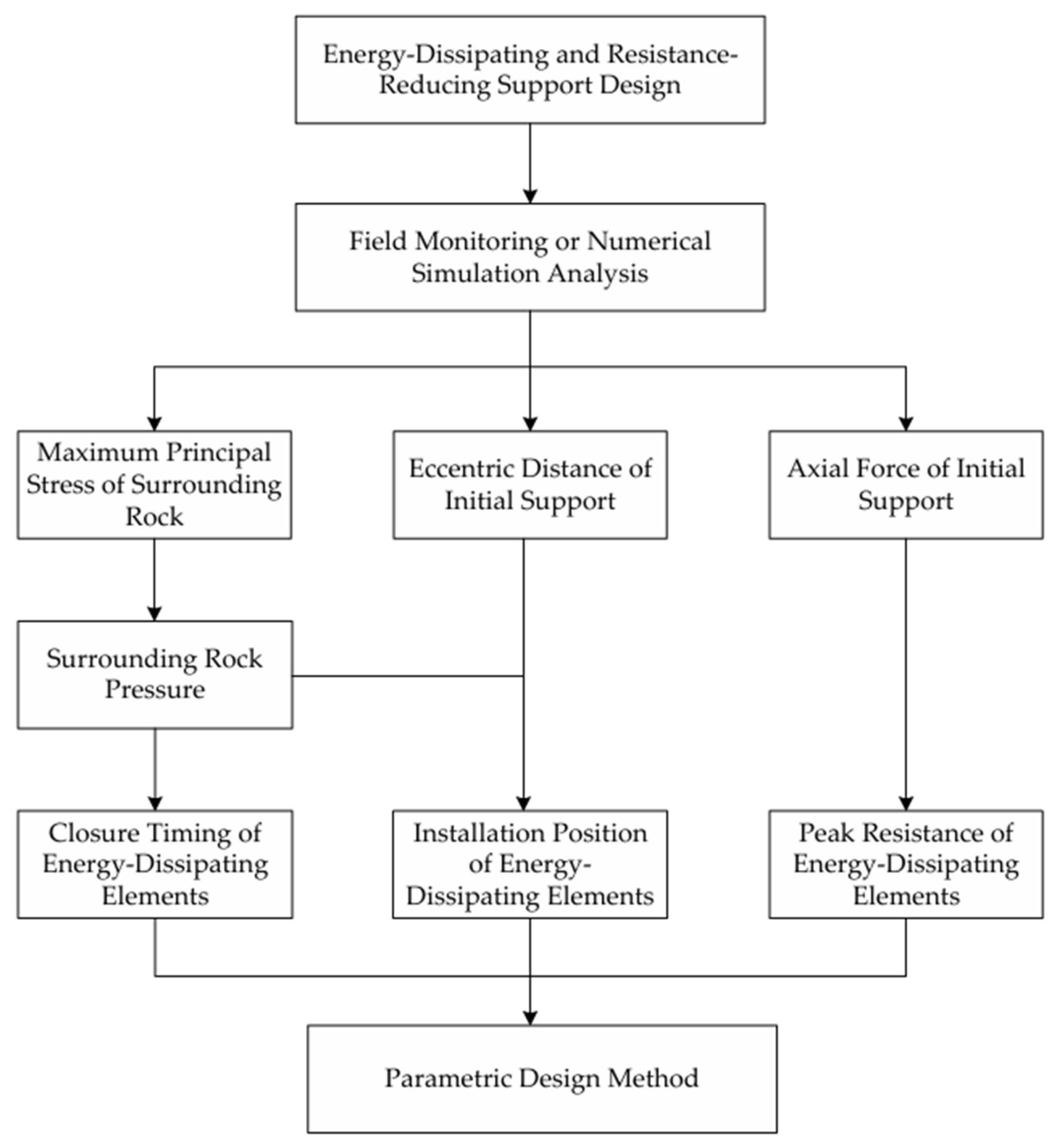

2.4. Parameter Design Method for Stress-Relief Support Structures

- For tunnels under different in situ stress conditions, obtain the surrounding rock stress field and the internal force distribution of the primary support through numerical simulation or field monitoring.

- Extract the maximum principal stress at the interface between the surrounding rock and the primary support as the surrounding rock pressure. Identify zones with relatively low pressure and determine feasible installation locations for the stress-relief elements by also considering construction convenience.

- Extract the axial force and bending moment of the primary support to determine how the eccentricity evolves with staged excavation. Based on the requirement that the installation location of the stress-relief element should remain under compressive stress across the entire section, verify the safety of the selected installation location derived from the surrounding rock stress field.

- Determine the closure timing of the stress-relief elements according to the evolution of surrounding rock pressure after each excavation step. To ensure sufficient stress release, the elements should generally be closed when the surrounding rock pressure stabilizes following the support installation of the subsequent excavation step.

- Extract the primary support axial force at the installation location under different in situ stress conditions and analyze its variation during staged excavation. Based on these data, determine the appropriate range for the peak bearing capacity of the stress-relief elements.

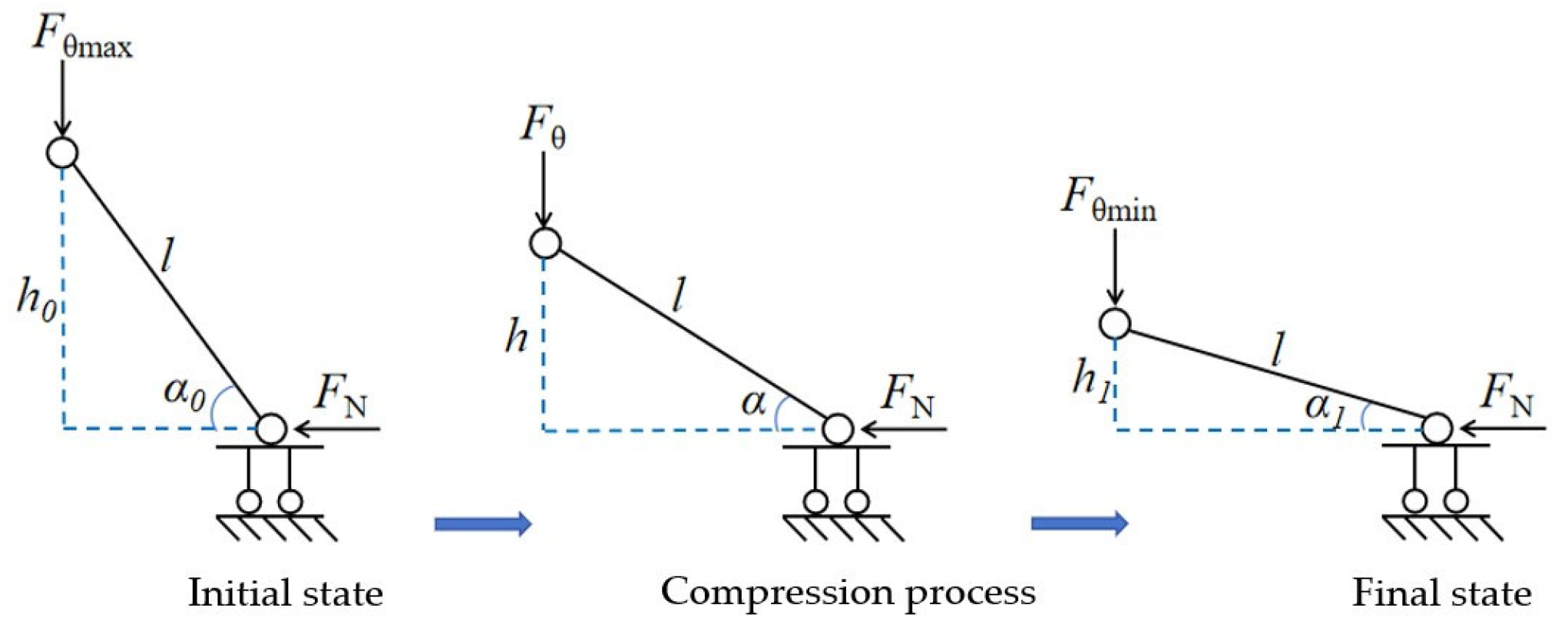

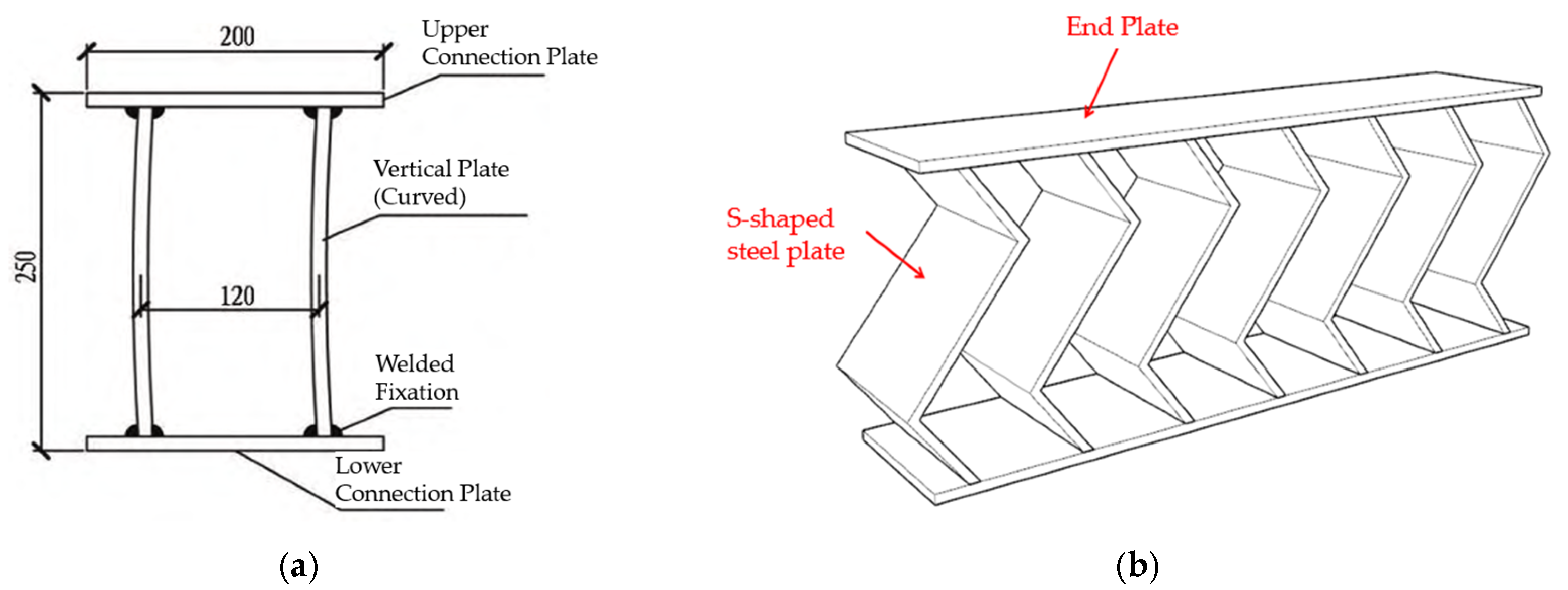

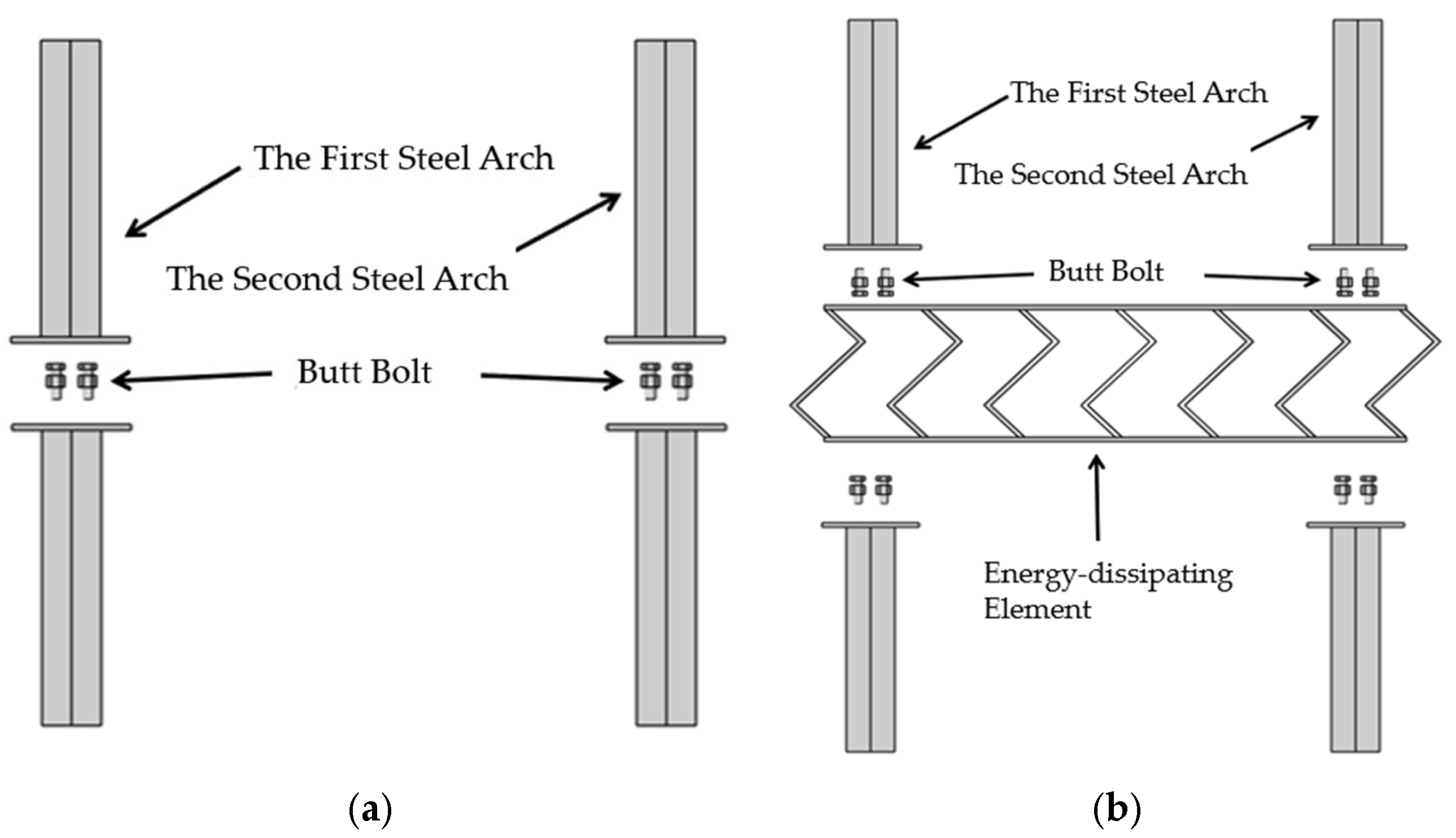

3. Design of the Friction-Reducing and Energy-Dissipating Support Structure

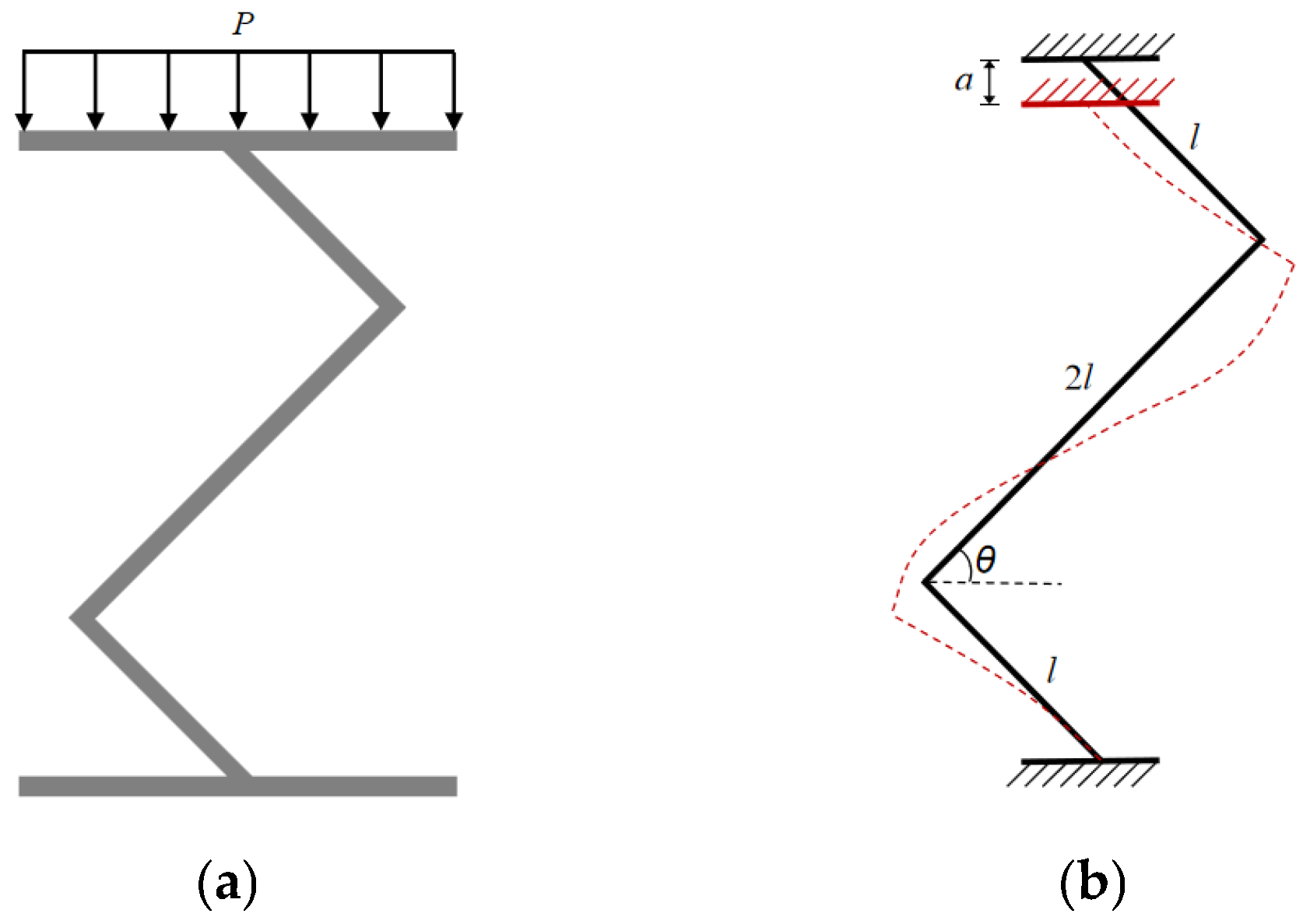

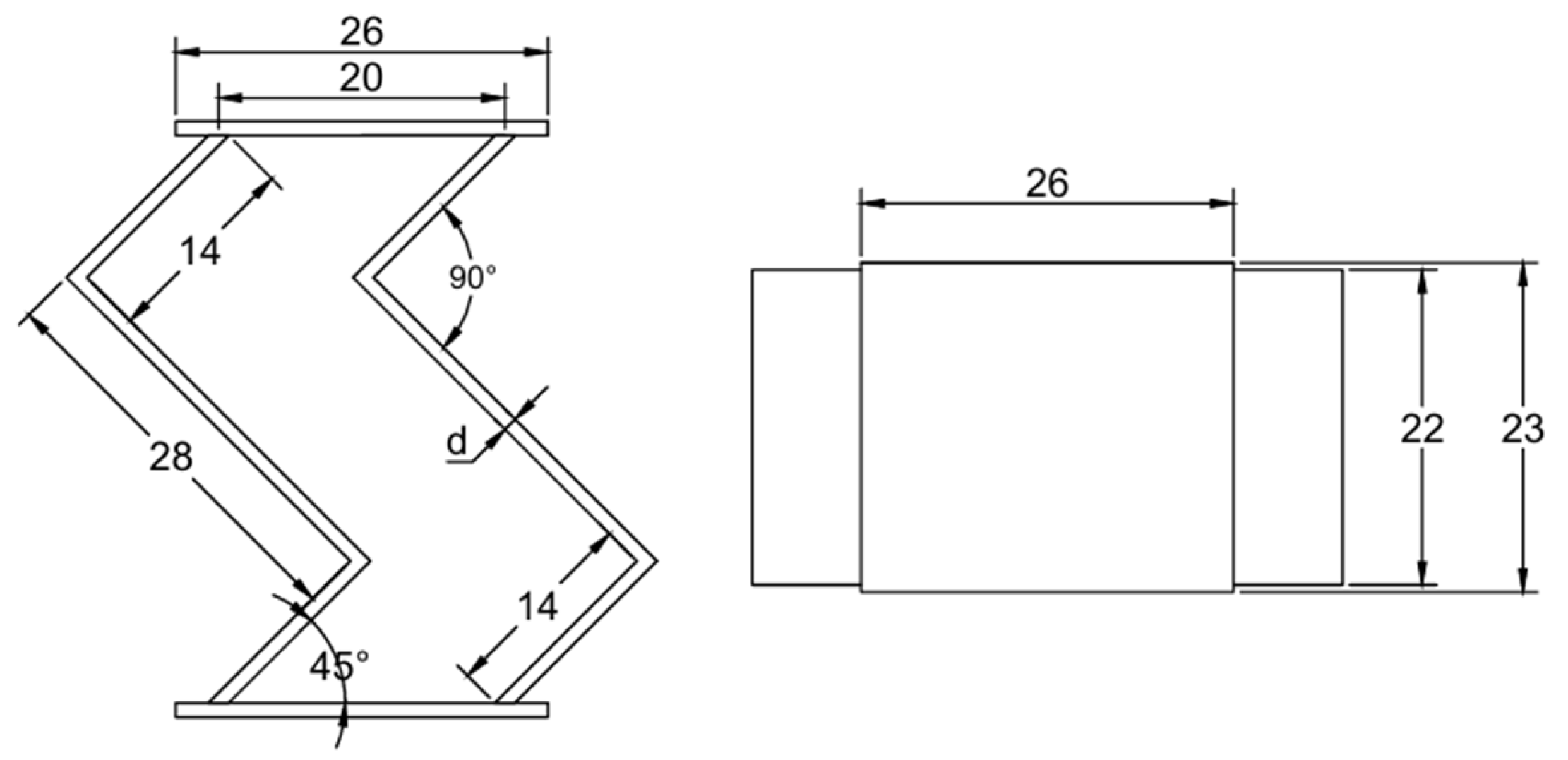

3.1. Mechanical Model and Calculation of the Friction-Reducing and Energy-Dissipating Element

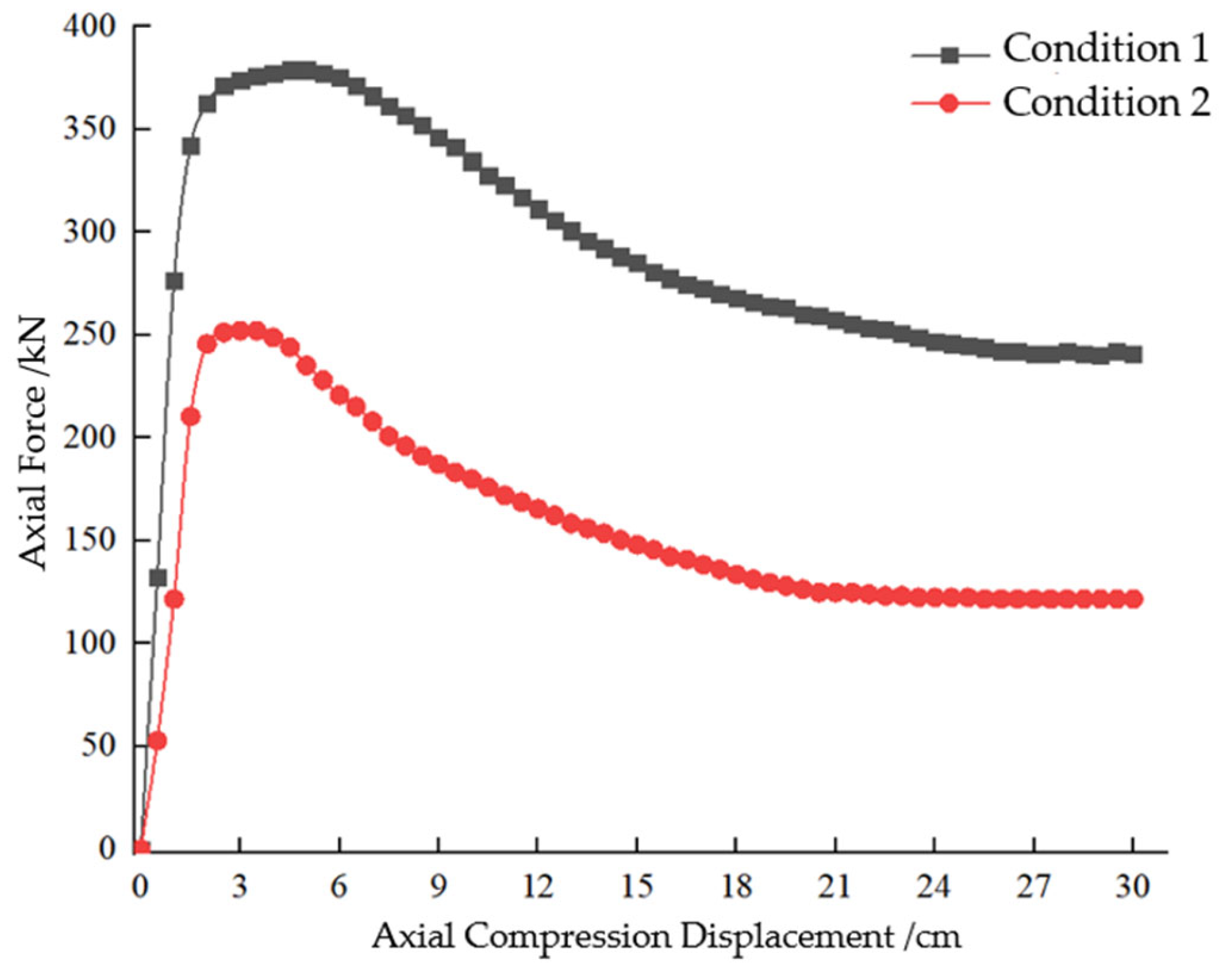

- In the elastic stage, the element provides a large bearing capacity.

- In the plastic (stress relief) stage, the bearing capacity decreases gradually as the bending angle reduces, allowing progressive stress relief and energy dissipation.

- Upon ultimate compression, the stiffness increases again, and the mechanical response approaches that of a rigid support system.

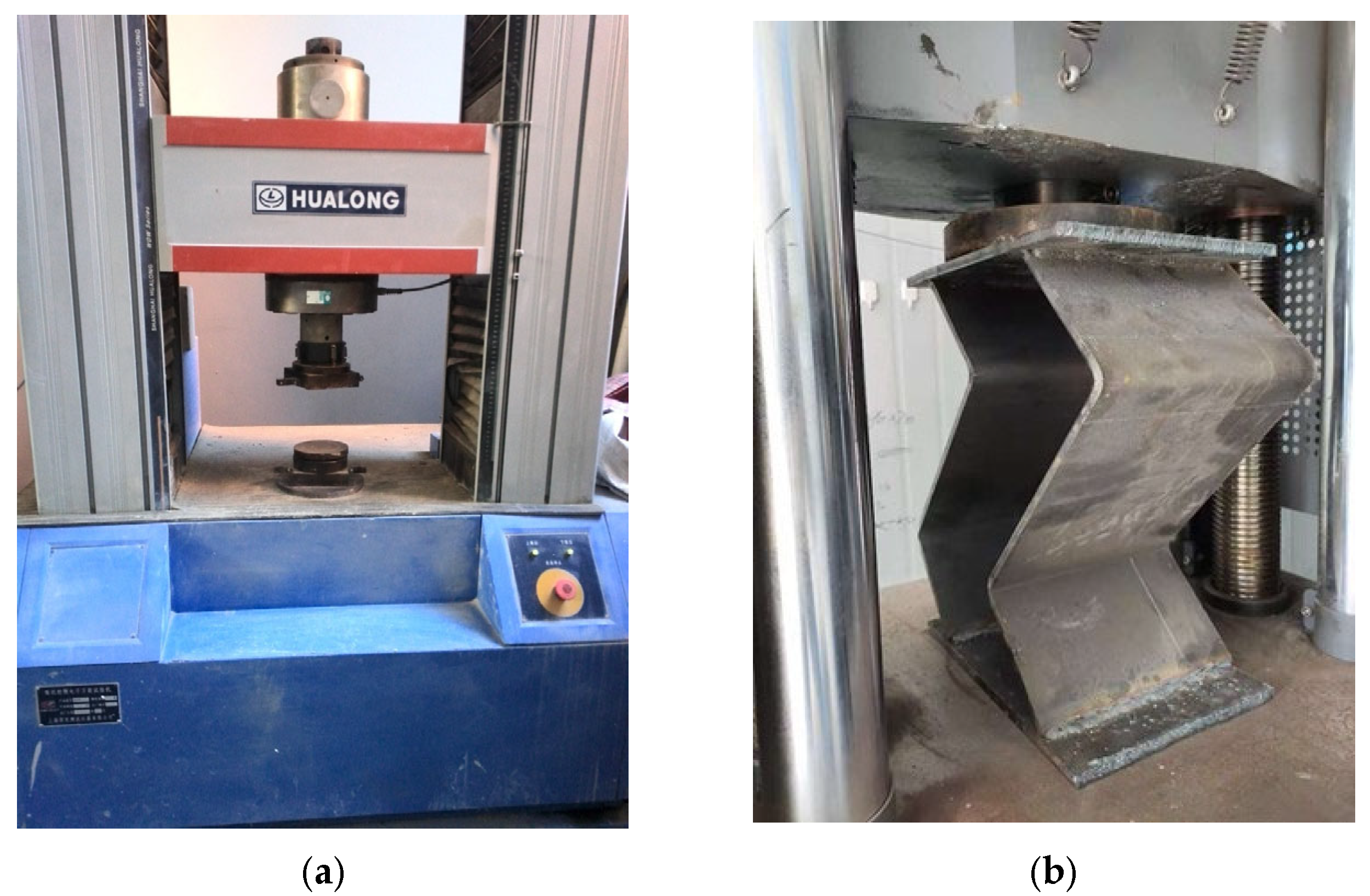

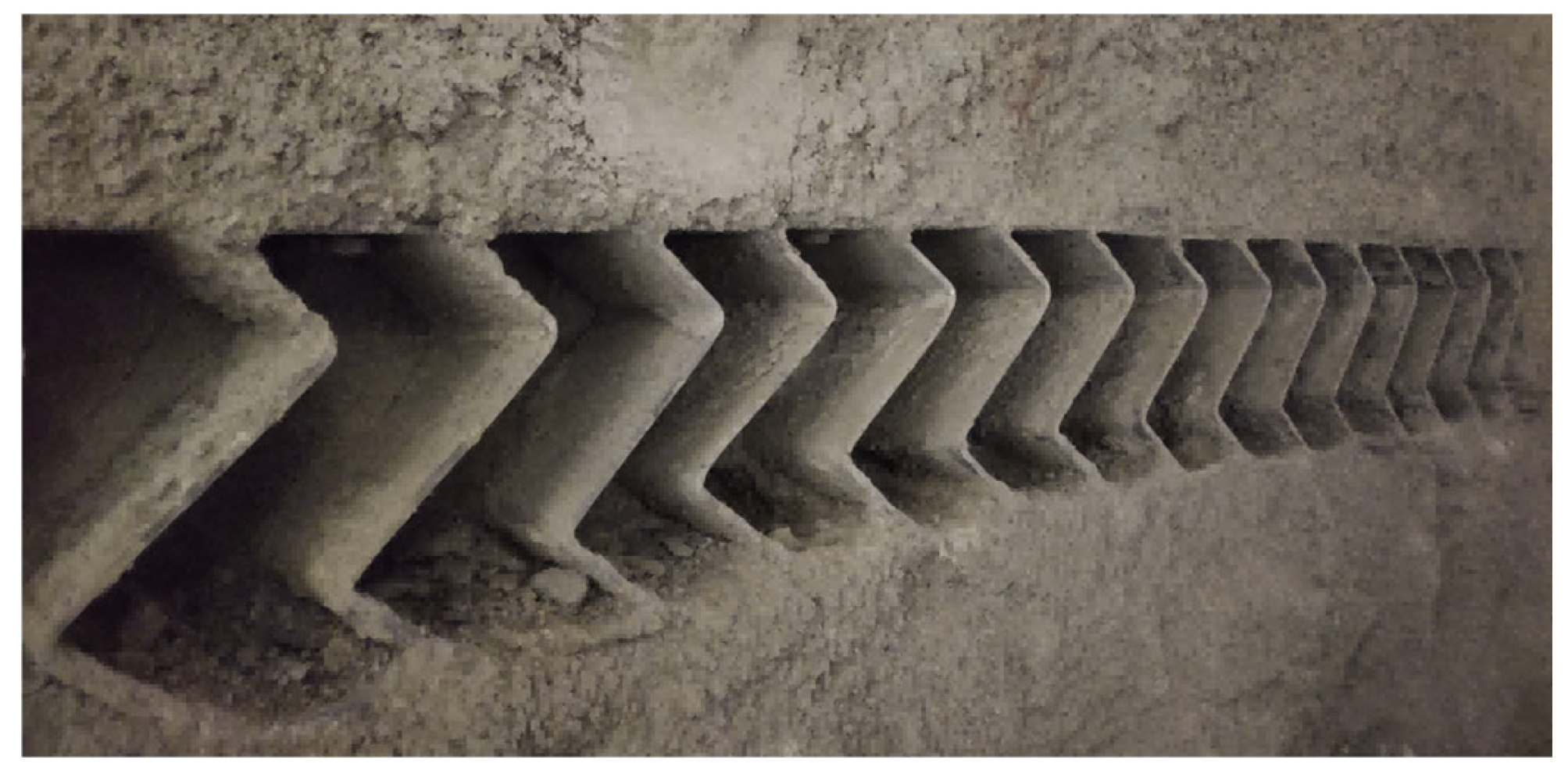

3.2. Laboratory Compression Test Analysis of the Friction-Reducing and Energy-Dissipating Element

3.3. Installation Procedure of the Friction-Reducing and Energy-Dissipating Element

- The friction-reducing and energy-dissipating elements are prefabricated in a steel processing plant and transported to the tunnel face together with the steel arches. During on-site assembly, each element is bolted between two arch segments to form an integrated primary support frame.

- After assembly, the primary shotcrete layer is applied. The gaps between the S-shaped steel plates are temporarily covered with wooden boards or geotextile to prevent inadvertent filling. The protection is removed after shotcreting to allow subsequent observation of the deformation behavior of the element.

- For the next construction cycle, the newly installed elements are welded to the ends of the previously installed ones to improve longitudinal stiffness and prevent uneven axial compression. Once the elements reach stable deformation or the designed deformation limit, the remaining gaps between the S-shaped plates are filled with shotcrete to complete the integrated support structure.

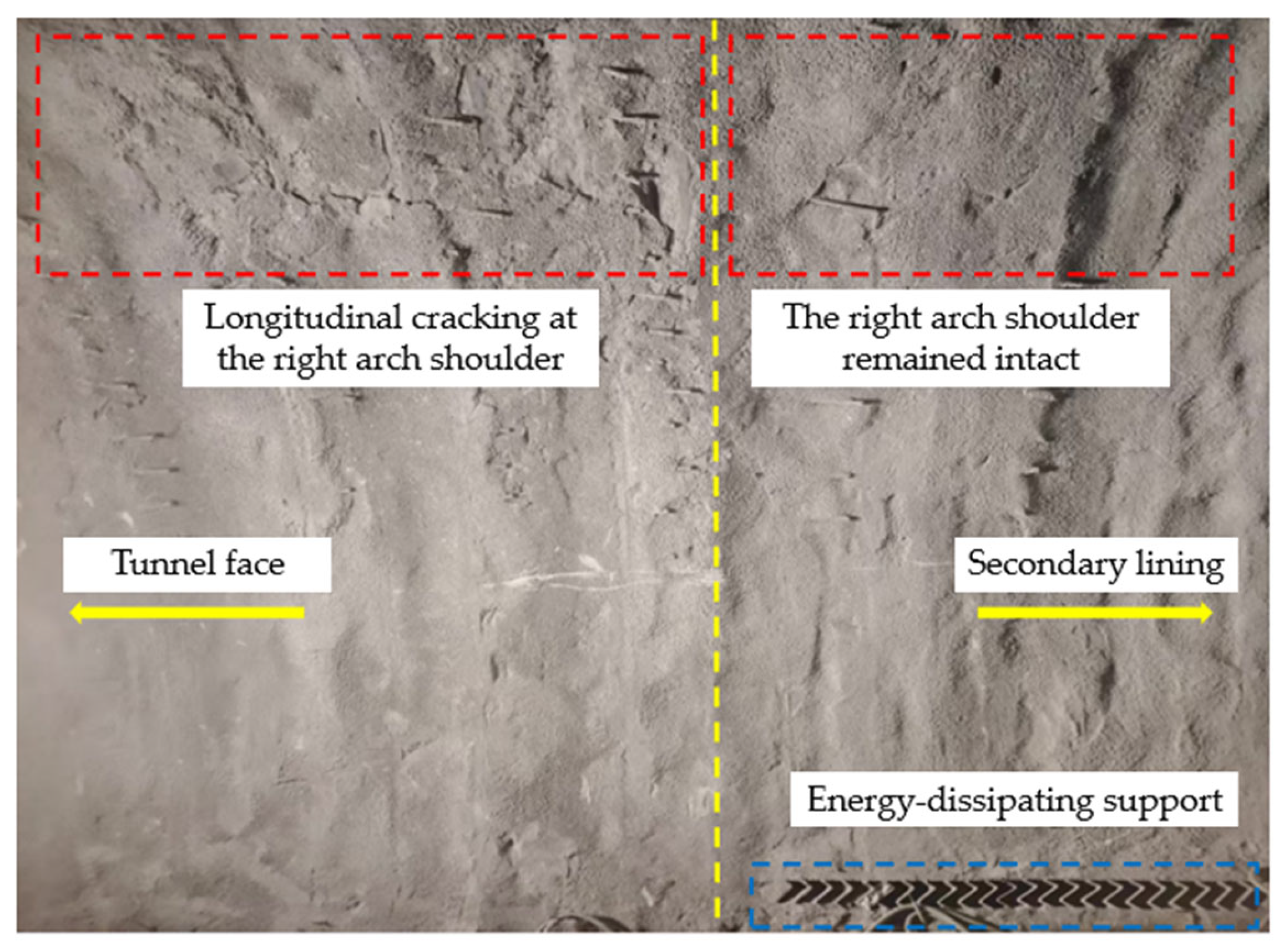

4. Application of Energy-Dissipating Support in Asymmetrically Stressed Tunnels with Large Deformation

4.1. Engineering Overview of Qiaojia Tunnel

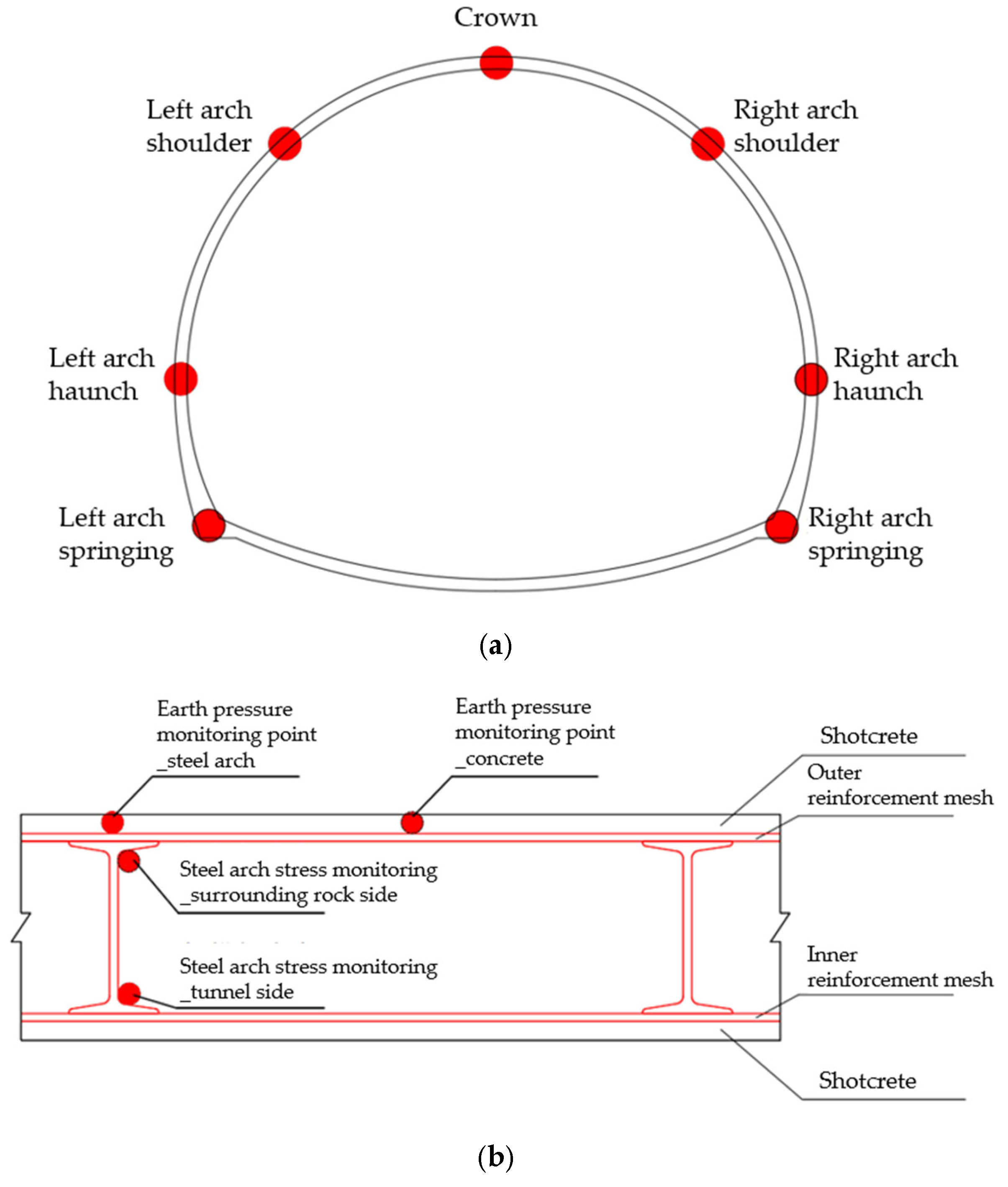

4.2. Design Parameters and Installation of Energy-Dissipating Support

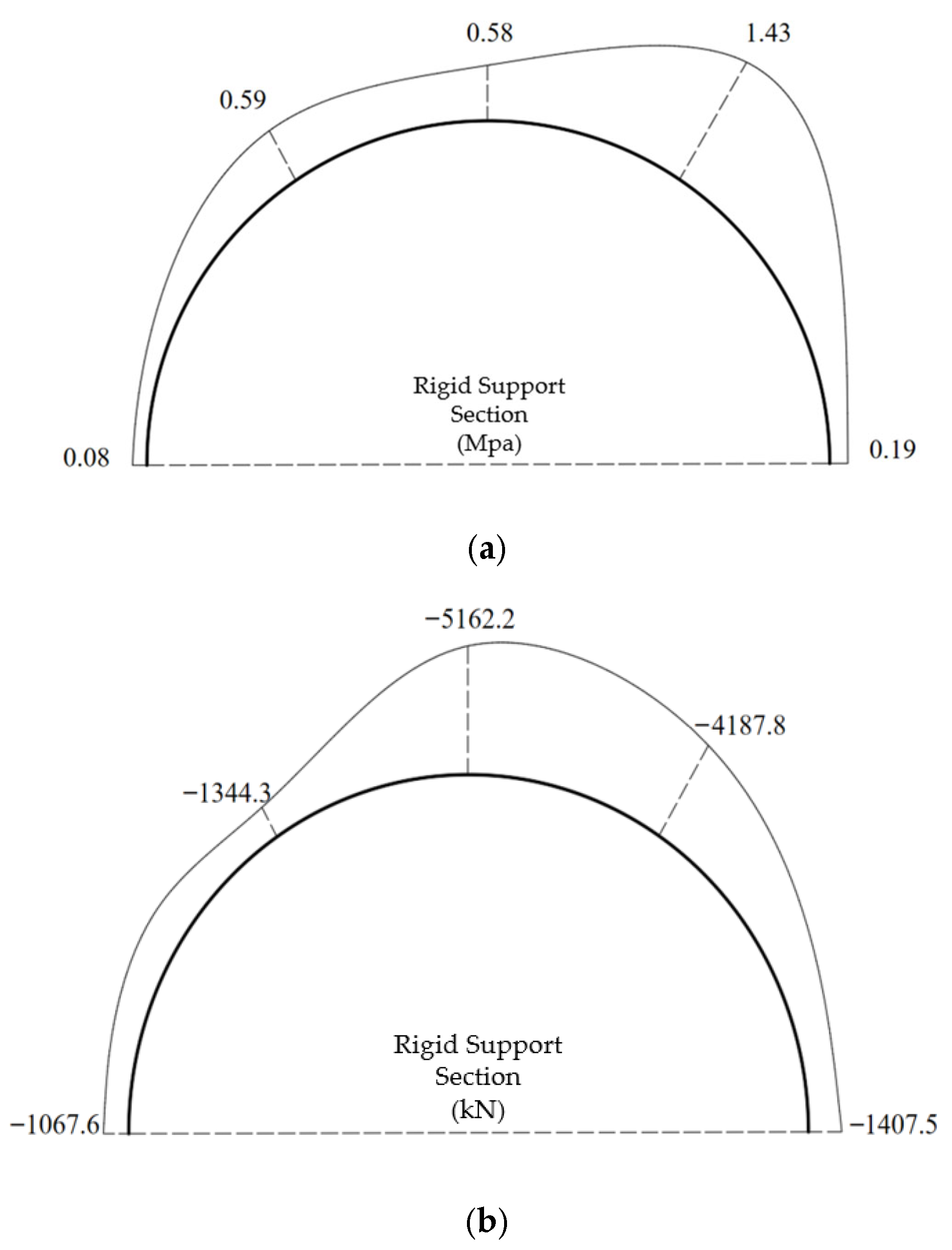

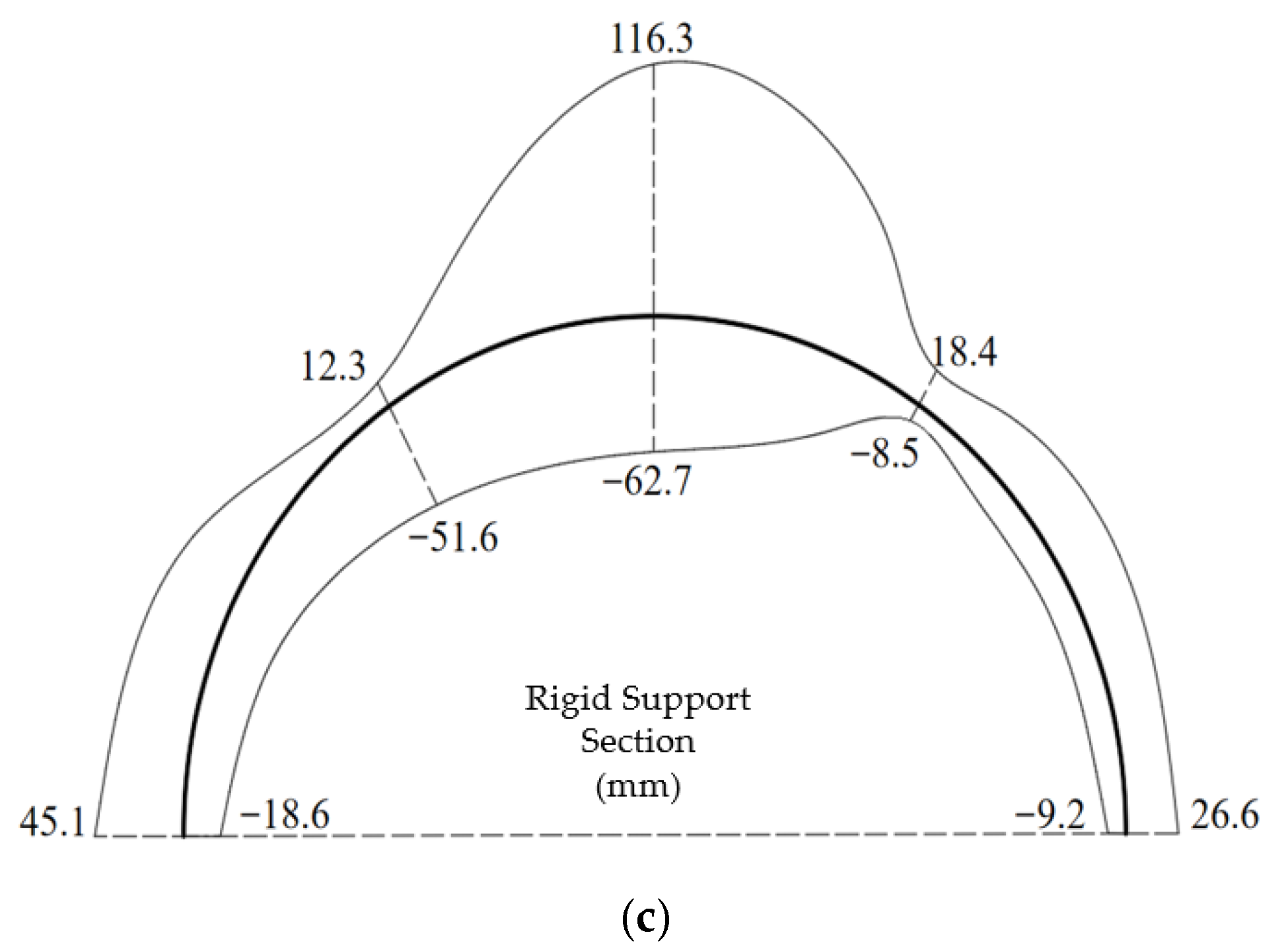

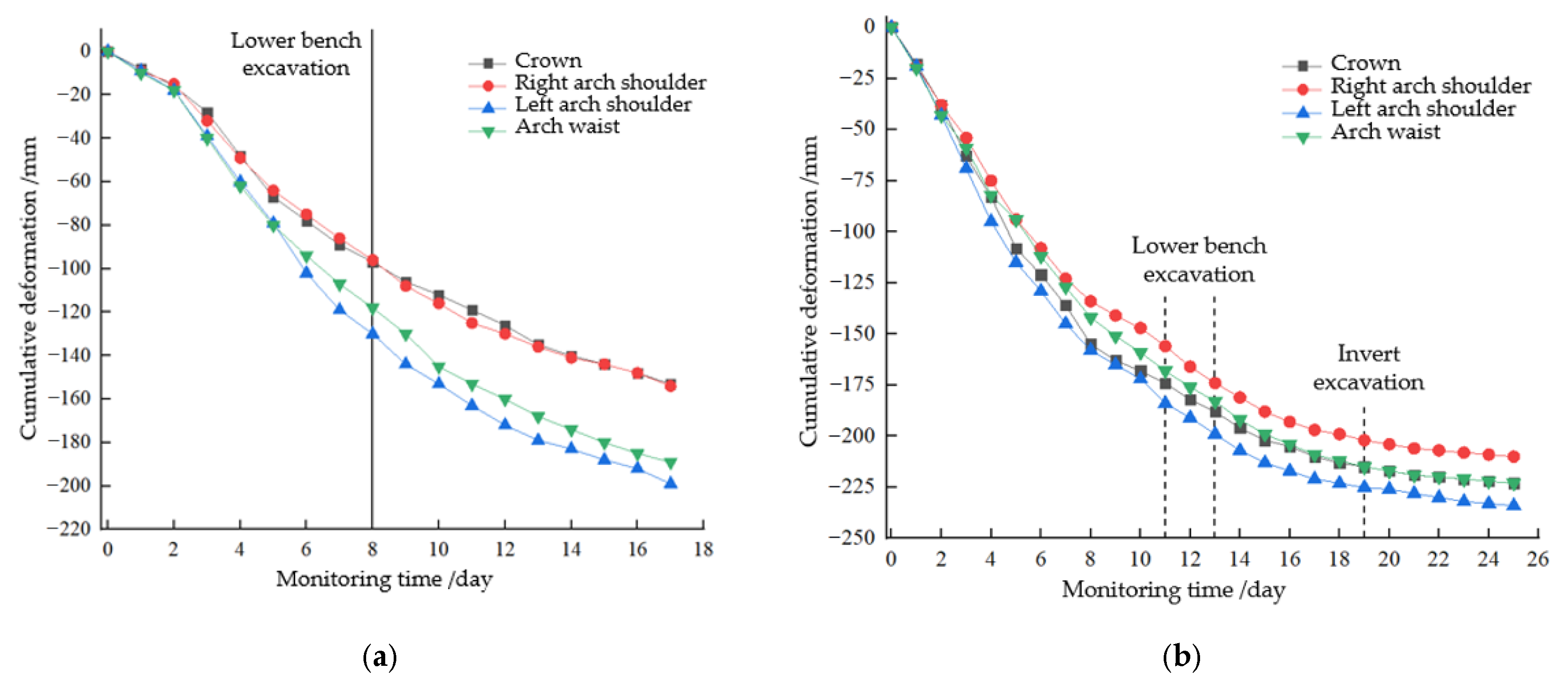

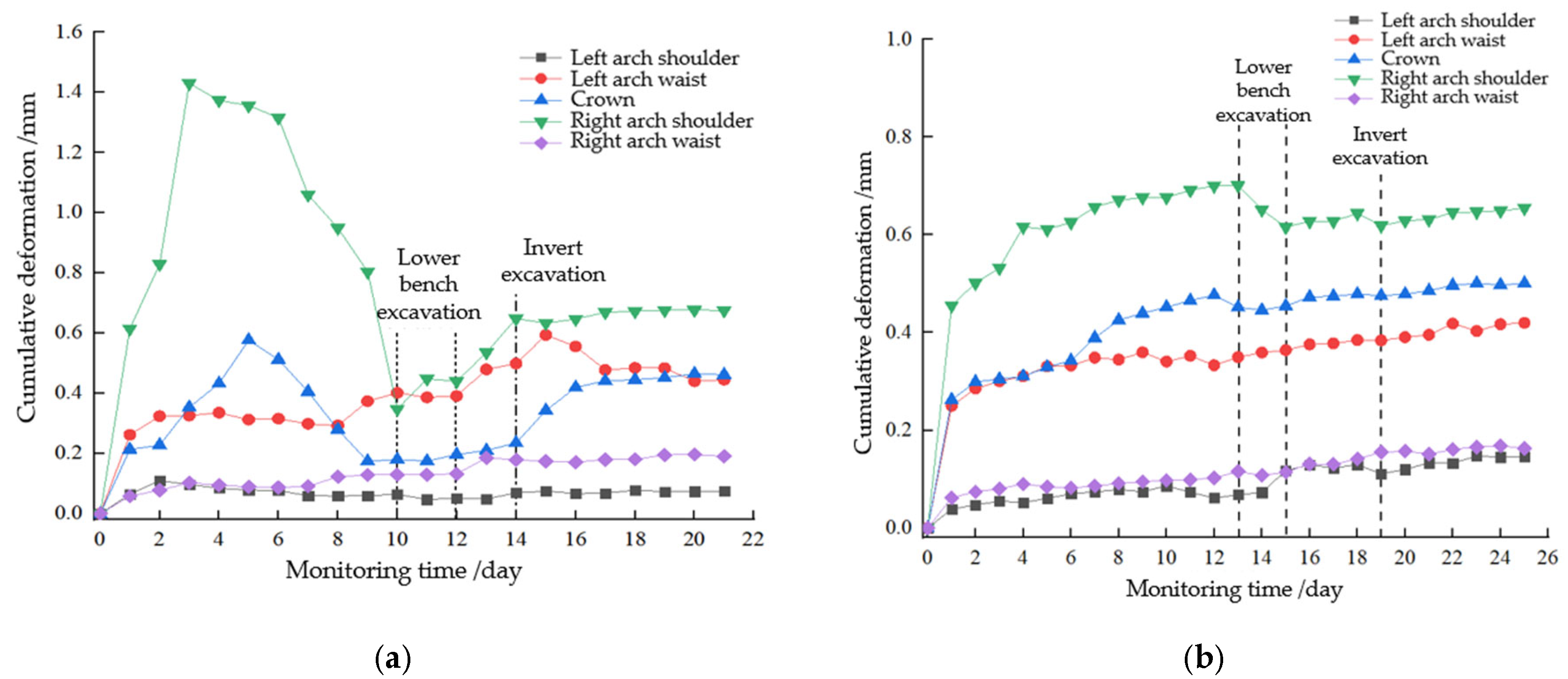

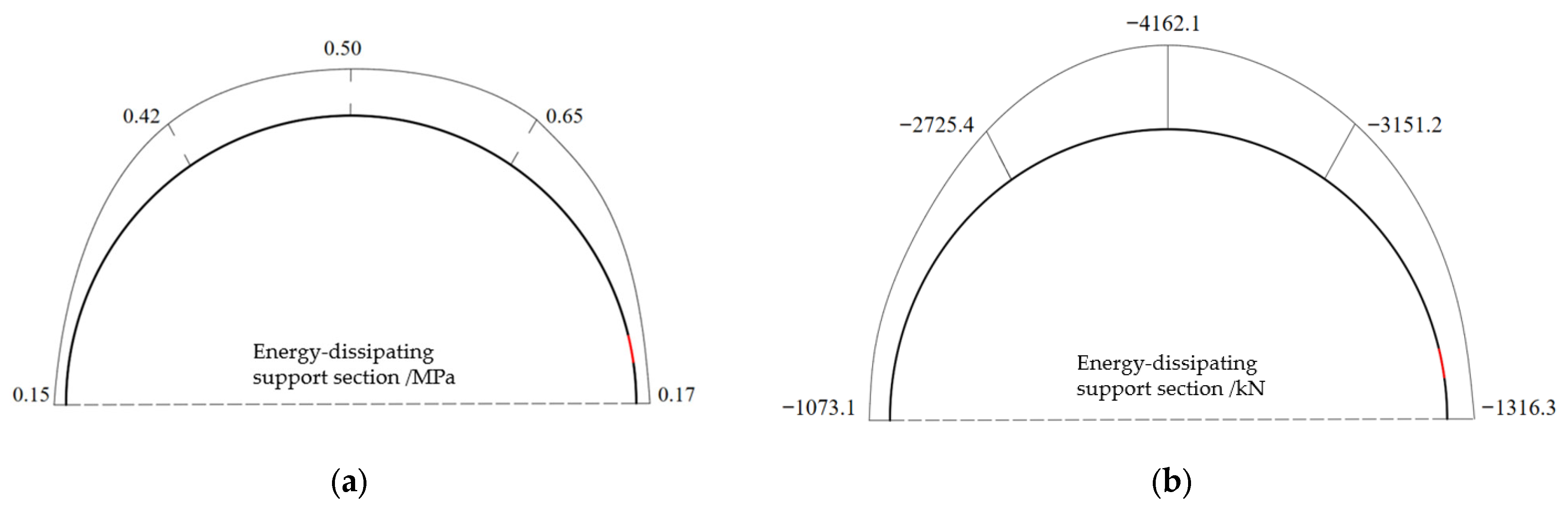

4.3. Analysis of the Control Effect of Energy-Dissipating Support

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusions

- A stress-relief support system with a “rigid–relief–rigid” variable-stiffness response is proposed. It provides high initial stiffness to restrain early loosening, then reduces resistance with deformation to maintain low radial imbalance force, and finally re-stiffens to promote rapid stabilization.

- A three-stage mechanical model is established based on the stress-relief mechanism and the convergence–constraint curve. By representing the relief stage with trigonometric functions, analytical solutions for all stages and a corresponding parameter-determination method are derived.

- A friction-reducing energy-dissipating element utilizing plastic bending of S-shaped steel plates is developed. Structural analysis and uniaxial compression tests verify both the theoretical model and the characteristic “rigid–relief–rigid’’ response.

- Field application in the Qiaojia Tunnel shows significant improvement in deformation control. Crown settlement (22.3 cm) and shoulder differential deformation (2.4 cm) meet design limits. Compared with rigid support, peak surrounding-rock pressures decreased by 20.2–45.4%, and the left–right shoulder pressure difference was reduced by 59.2%, effectively mitigating asymmetric deformation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ding, Y. Study on Construction Control Technology for Large Deformation in Soft-Rock Tunnels. Sichuan Hydropower 2020, 39, 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Cheng, S.; Yu, H.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Huang, X.; Gao, F.; Jing, G. Probabilistic assessment of rockburst risk in TBM-excavated tunnels with multi-source data fusion. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 152, 105915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Tan, Z.; Guo, X.; Wu, Y.; Luo, N. Study on Large Deformation of Tunnels in High-Stress, Steeply-Dipping Interbedded Schist Strata. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2017, 36, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.H.; Yan, J.X.; Liang, W.H. Challenges and development prospects of ultra-long and ultra-deep mountain tunnels. Engineering 2019, 5, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza-Torres, C.; Fairhurst, C. Application of the convergence–confinement method of tunnel design to rock masses that satisfy the Hoek–Brown failure criterion. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2000, 15, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Luo, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, W. Mechanism and Control Method of Large Deformation in a Large-Span Tunnel Excavated in Chlorite Schist. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2021, 21, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, C.O.; Genis, M. A review of the numerical modeling procedure in mining. Int. J. Min. Miner. Process. 2010, 1, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, F.; Song, H.; Guo, Z.; Lu, S.; Liang, S. Support Theory of the Loosening Zone in Roadway Surrounding Rock. J. China Coal Soc. 1994, 19, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H. Key-Zone Theory of Surrounding Rock in Roadways. Mech. Eng. 1997, 19, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lunardi, P. Design and Construction of Tunnels; Analysis of Controlled Deformations in Rock and Soils; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.C.; Wang, Q. Excavation compensation method and key technology for surrounding rock control. Eng. Geol. 2022, 307, 106784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, M.D.G. Energy Considerations in Rock Mechanics: Fundamental Results. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 1984, 84, 233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J. Understanding of Lithological Characteristics and Surrounding Rock Stability of Tunnels in High In-Situ Stress Areas. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 1988, 7, 185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Gao, F.; Chen, Z.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, S. Intelligent Multi-Channel Classification of Microseismic Events during TBM Excavation. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 7056–7077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yu, W.; Zi, X.; Cheng, X.; Guo, X.; Fan, Y. Discussion on the Rationality of Different Support Modes for Large-Deformation Soft-Rock Tunnels: A Case Study of the Muzhaling Highway Tunnel. Tunn. Constr. 2023, 43, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Guo, X.; Ma, Z.; Yang, T.; Xu, J. Research Status of Squeezing Large-Deformation Tunnels and the High-Strength Prestressed Primary Support System. Tunn. Constr. 2020, 40, 755–782. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Xie, X.; Tang, G.; Zhou, B.; Xu, D.; Huang, Y. A new adaptive compressible element for tunnel lining support in squeezing rock masses. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 137, 105124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Guo, Z.; Qiao, X.; Tao, Z.; Wang, F. Constant Resistance and Yielding Support Technology for Large Deformations of Surrounding Rocks in the Minxian Tunnel. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Wang, G.; Gong, L.; Shen, Z.; Li, C.; Dang, J. Development and application of a limited-resistance energy-absorbing support structure for large-deformation tunnels. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2018, 37, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar]

| Rock Grade | Unit Weight (kN/m3) | Deformation Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Cohesion (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade IV Rock | 20 | 1.5 | 0.35 | 0.4 |

| Item | Specification |

|---|---|

| Model | Hualong WAW-600 |

| Maximum static test load | 600 kN |

| Load measurement range | 4–100% FS |

| Load accuracy | <±1% |

| Maximum piston speed | 100 mm/min |

| Maximum piston displacement | 600 mm |

| Test ID | Steel Plate Material | Plate Thickness d (cm) | Compression Stroke (cm) | Loading Rate (cm/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition 1 | Q235 | 1.0 | 30 | 0.2 |

| Condition 2 | Q235 | 0.8 | 30 | 0.2 |

| Chainage Range | Length (m) | Rock Class | [BQ] | BQ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZK67 + 170~ZK67 + 020 | 150 | Ⅴ1 | 242 | 0.45 | 2900 | 33.00 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0 | 312 |

| ZK67 + 020~ZK66 + 850 | 170 | Ⅴ1 | 227 | 0.45 | 2900 | 21.40 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0 | 277 |

| ZK66 + 850~ZK66 + 650 | 200 | Ⅳ3 | 262 | 0.55 | 3000 | 21.40 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 309 |

| No. | Measured Item | Instrument | Specification | Monitoring Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Steel arch stress | Wire-type surface strain gauge | 2000 με | 1 time/day |

| 2 | Contact pressure between the surrounding rock and the initial support | Earth pressure cell | 1.2 MPa | 1 time/day |

| 3 | Foundation bearing capacity below the arch foot | Earth pressure cell | 3 MPa | 1 time/day |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Xie, X.; Tang, G.; Li, S.; Wu, Q. A Stress-Relief Concept and Its Energy-Dissipating Support for High-Stress Soft-Rock Tunnels. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010213

Liu H, Xie X, Tang G, Li S, Wu Q. A Stress-Relief Concept and Its Energy-Dissipating Support for High-Stress Soft-Rock Tunnels. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):213. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010213

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Huaiyang, Xiongyao Xie, Genji Tang, Shouren Li, and Qilong Wu. 2026. "A Stress-Relief Concept and Its Energy-Dissipating Support for High-Stress Soft-Rock Tunnels" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010213

APA StyleLiu, H., Xie, X., Tang, G., Li, S., & Wu, Q. (2026). A Stress-Relief Concept and Its Energy-Dissipating Support for High-Stress Soft-Rock Tunnels. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010213