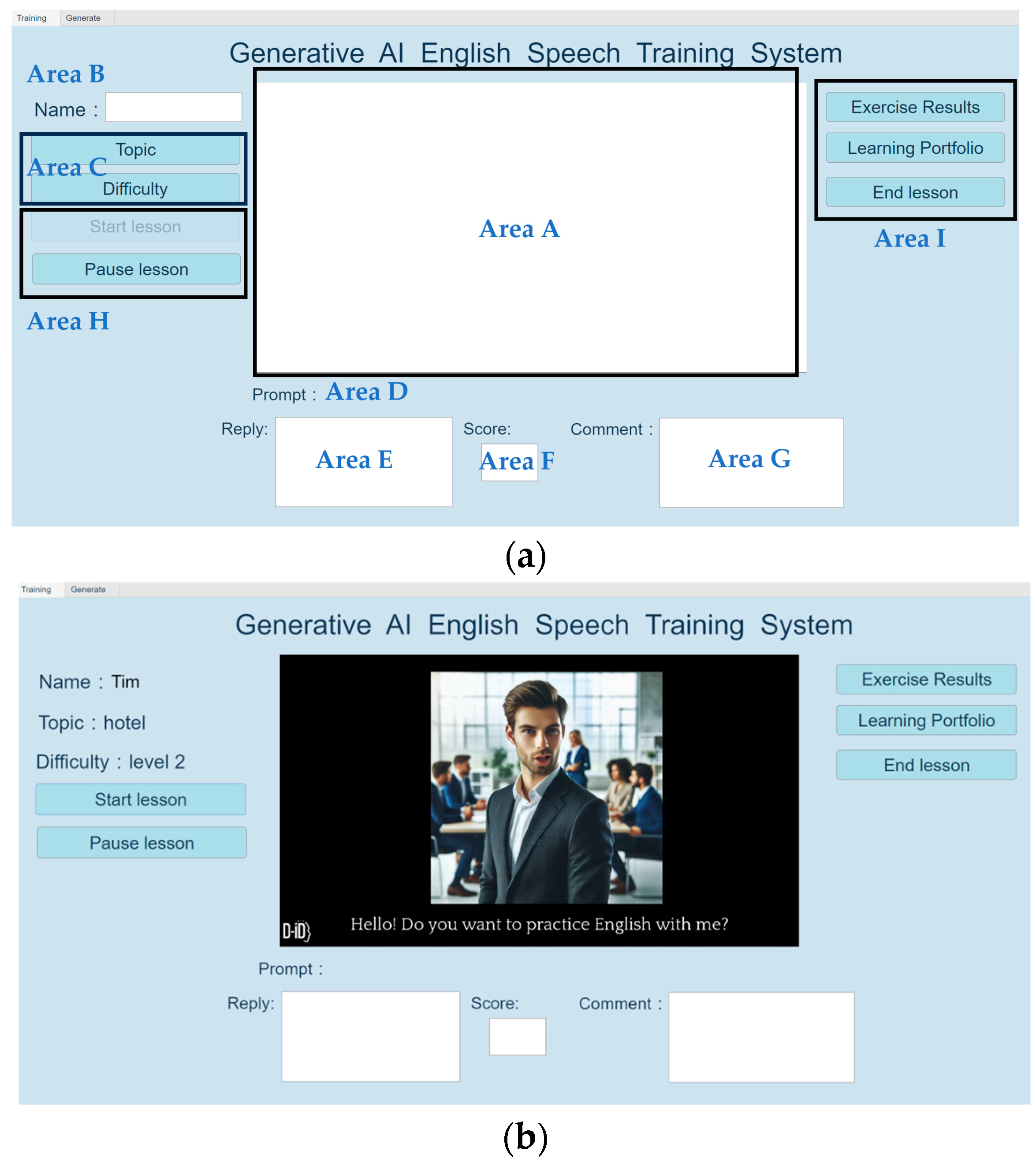

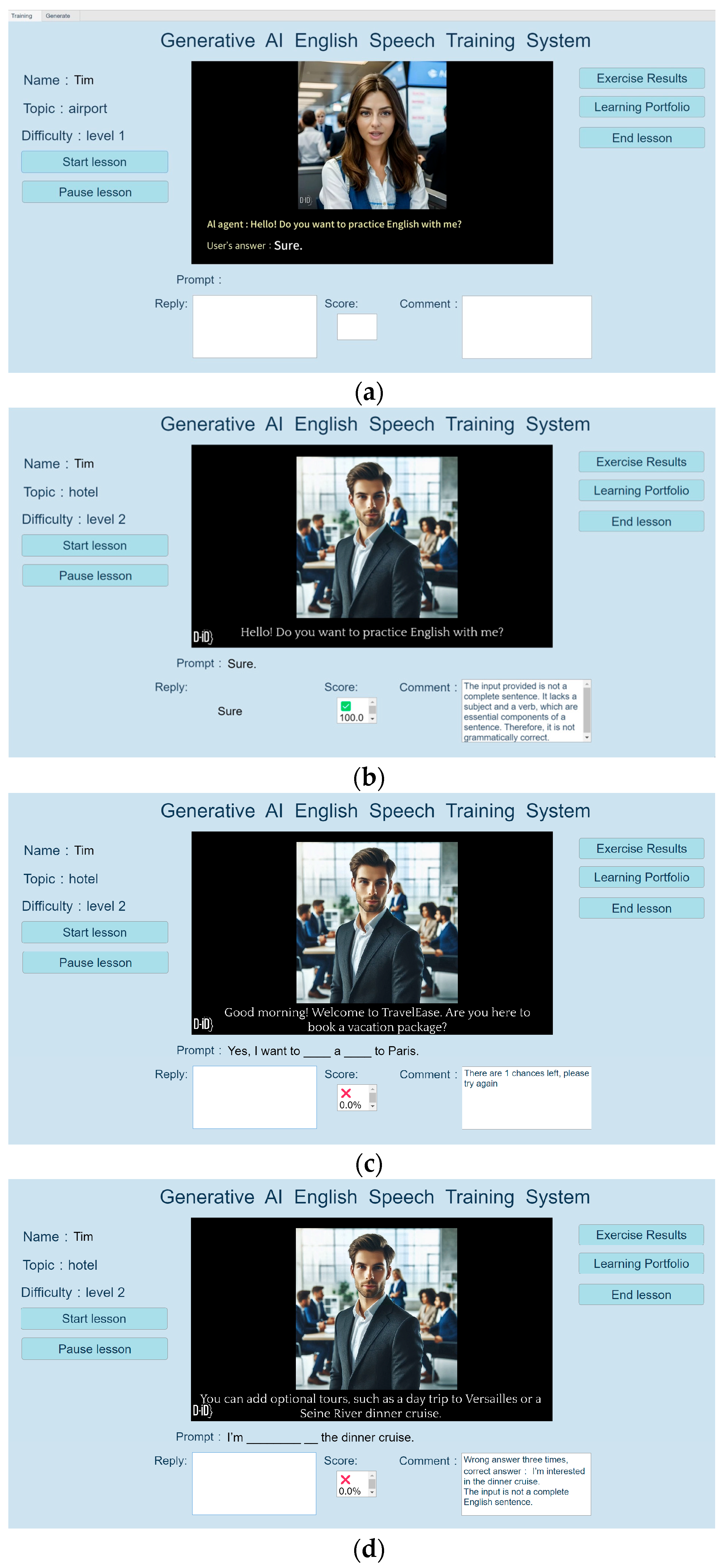

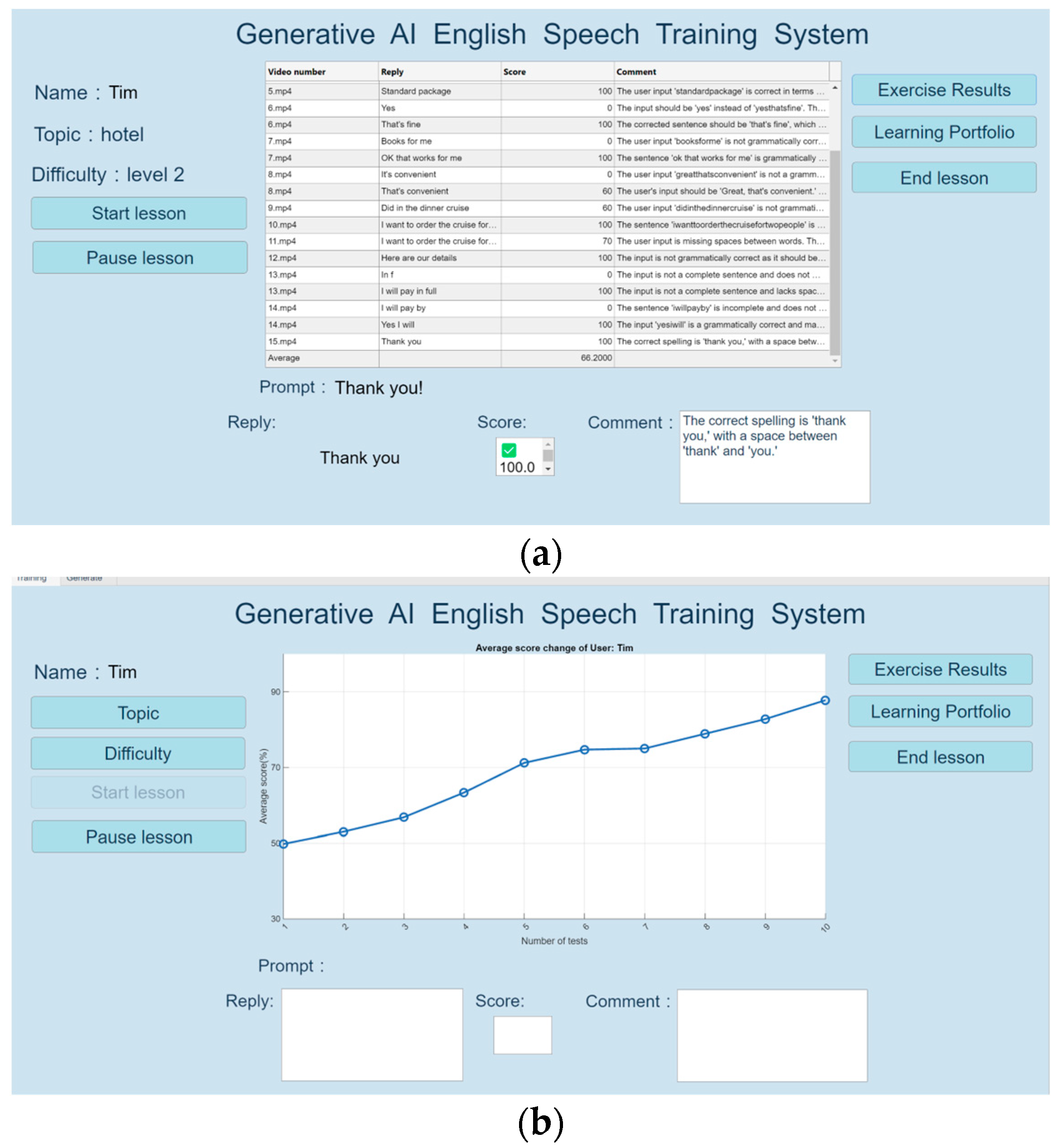

The system is divided into three levels of difficulty for conversation. In Level 1, the simplest level, the dialog image displays the AI agent’s speech content. It provides the user with sentences that need to be answered, making it the best choice for beginners who want to improve their English-speaking skills. Level 2 is the moderately complex level. The dialog image no longer provides the user with the complete sentences. However, the system provides the sentences in the prompting area, and the user only needs to know the verb or unit of measure and recite the complete sentence to complete the entire oral training. Users only need to know the verb or unit of measure in the blanks and recite the complete sentence to complete the speaking exercise. The most challenging level is Level 3, where the system provides the user with only a few keywords, such as specific names or places, and the user must respond to the AI agent according to the given conditions.

4.1. Experimental Procedures

The participants in this study were undergraduate students enrolled in English courses at a university in Taiwan. To ensure a comparable baseline of language proficiency, five inclusion criteria were applied: (1) participants were third- or fourth-year undergraduates who had completed at least two semesters of compulsory university English courses; (2) they were classified as intermediate level according to the university’s English placement test; (3) their English proficiency was equivalent to IELTS scores of 6.0–6.5; (4) based on self-reported questionnaires, they had an average of approximately 15 years of English learning experience; and (5) they had never resided long-term in an English-speaking country.

In addition, three exclusion criteria were adopted: (1) the presence of hearing impairments or speech articulation disorders that could affect speech recognition performance; (2) current participation in intensive English tutoring programs or exchange programs; and (3) failure to complete the pre-test. Based on these criteria, a total of 100 students were ultimately recruited to participate in this study.

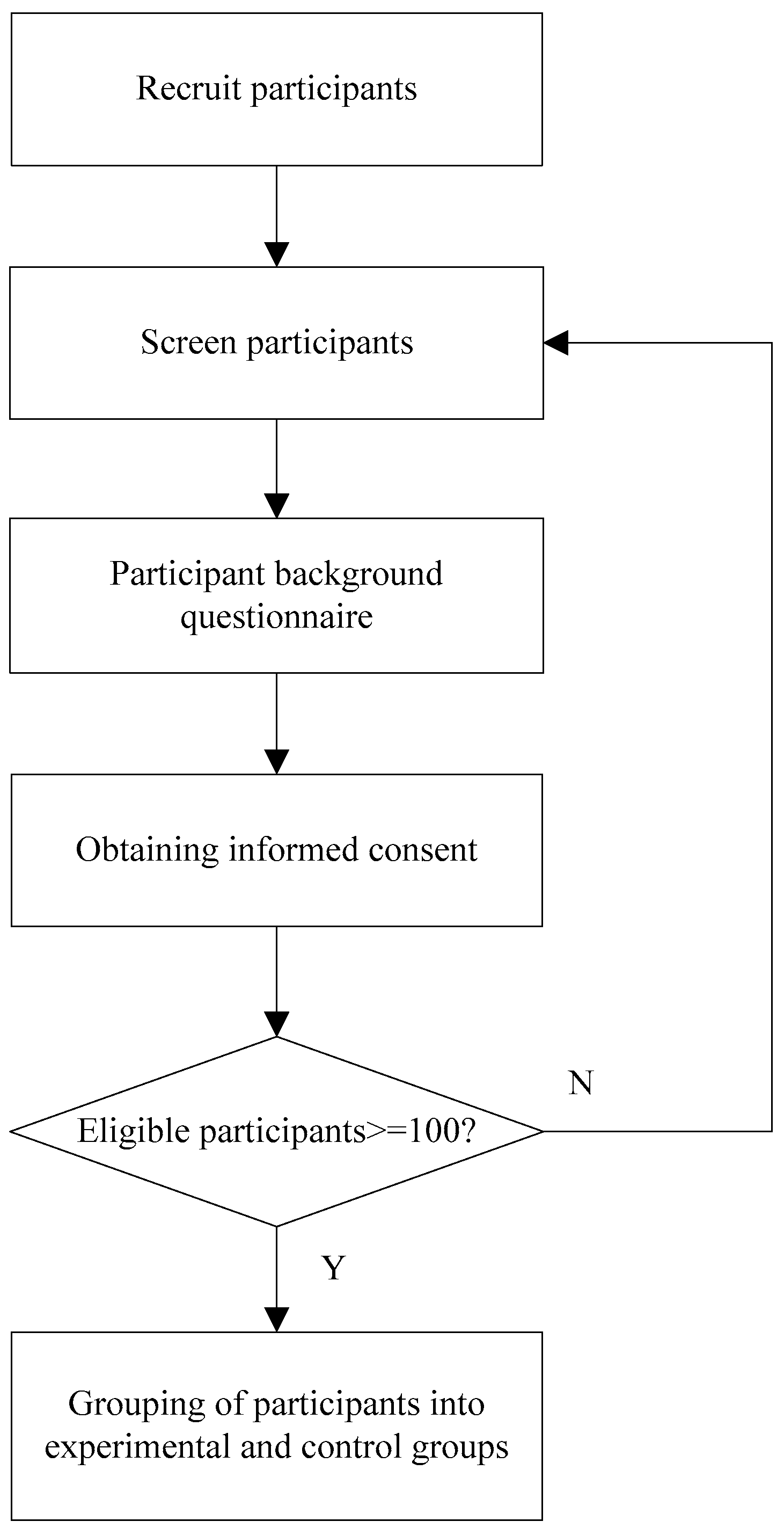

The participant screening procedure was conducted in four stages, as illustrated in

Figure 10. First, volunteer students were recruited from intermediate-level English courses at the university to form the initial pool of potential participants. In the second stage, a self-reported background questionnaire was administered to screen students who met the inclusion criteria and to exclude those who did not satisfy the requirements. In the third stage, the researchers provided eligible students with a detailed explanation of the study objectives, procedures, and participant rights, and obtained written or online informed consent. Finally, the 100 qualified participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group or the control group, with 50 participants in each group, while ensuring that the two groups were relatively balanced in terms of background characteristics and English proficiency levels.

To ensure that participants in the experimental group could effectively use the English-speaking training system developed in this study, we conducted a standardized system usage and operational training session prior to the formal experiment. First, the researcher demonstrated the system login procedure, task presentation interface, voice recording process, and the feedback mechanism provided after each practice session. Next, each participant in the experimental group was required to complete 3–5 trial questions to confirm that they could correctly activate the audio recording, complete spoken responses, and review the system feedback. During the trial phase, the researcher provided individual assistance to resolve technical or operational issues, such as microphone configuration problems, insufficient input volume, or incorrect procedures. Additionally, a concise user manual was provided, outlining the system’s workflow and standard troubleshooting guidelines, to ensure that all participants were familiar with the system’s operation before the formal training sessions began.

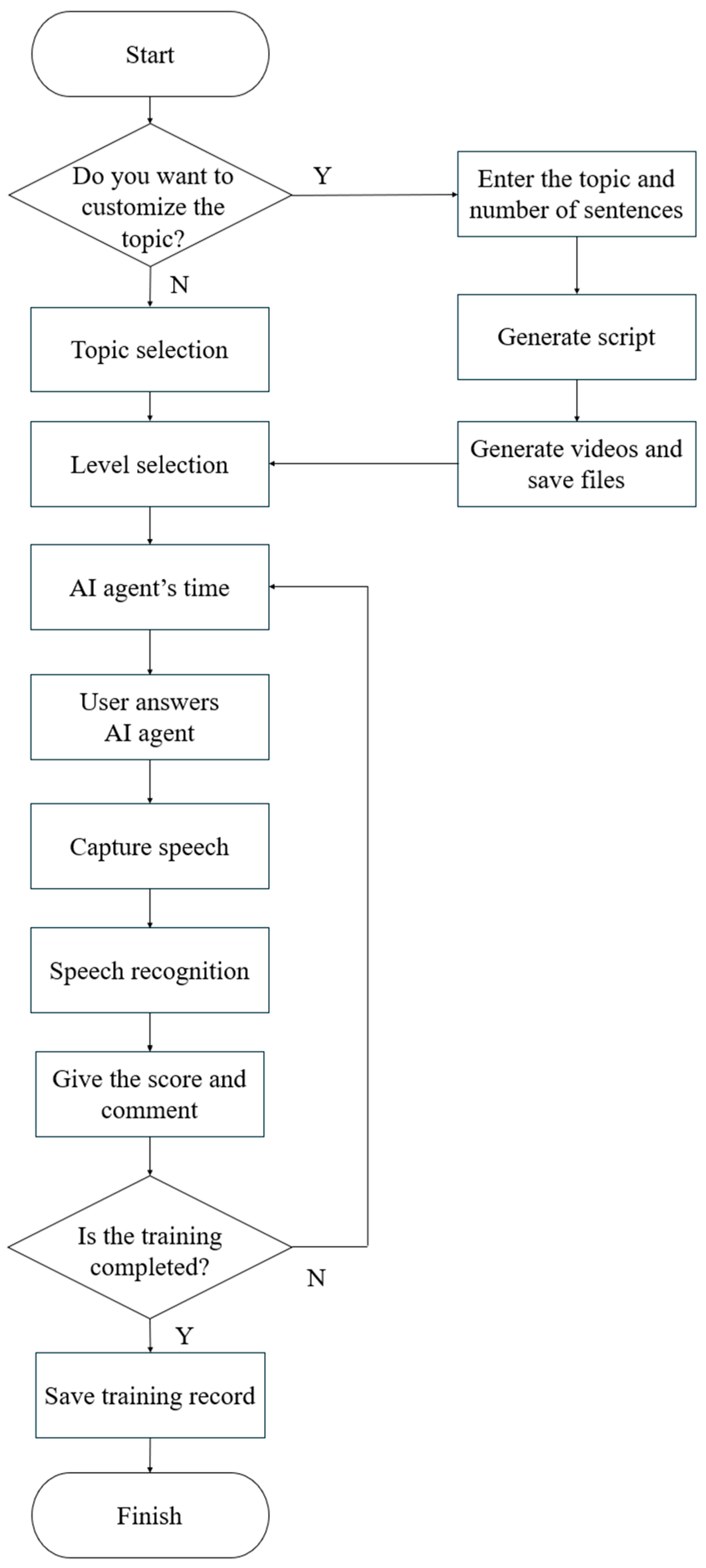

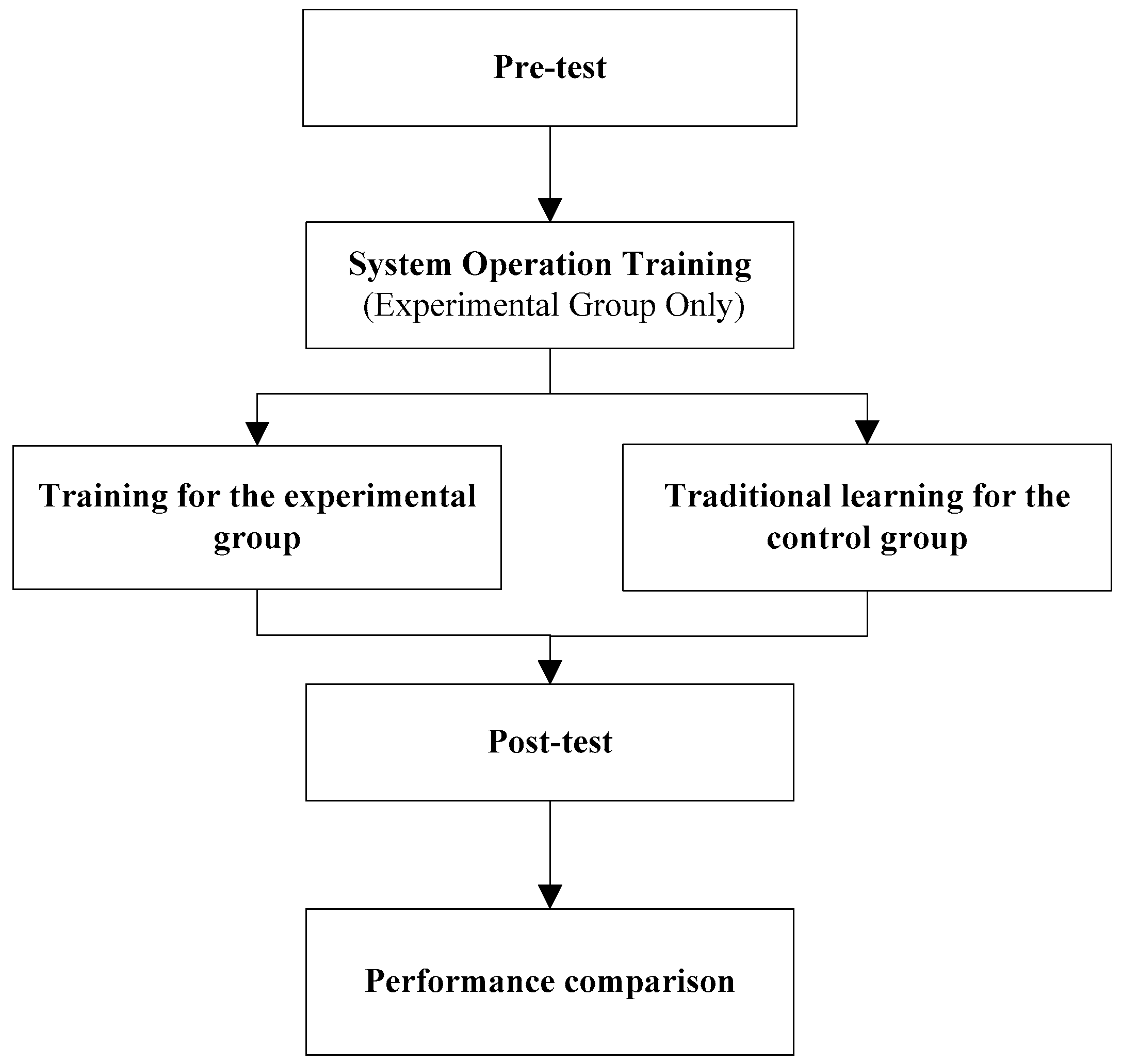

Figure 11 illustrates the experimental workflow of the system. This study adopted a pre-test–training–post-test experimental design. First, all participants completed a pre-test using the proposed system prior to the experiment to obtain baseline scores and average response times. The pre-test items and testing procedures were identical for both groups.

The experimental group then underwent a four-week English-speaking training period using the proposed system, during which they were required to complete ten training sessions. In contrast, the control group followed traditional English instruction, which included classroom reading, note-taking, oral discussions, and after-class review, without utilizing the proposed system. The system automatically recorded the experimental group’s responses and average response times for each training session for subsequent analysis.

After the experimental group completed the ten training sessions, all participants were administered a post-test within one week of the final session. The post-test content was identical to that of the pre-test. By comparing changes in test scores and average response times between the pre-test and post-test, the effectiveness of the proposed system in improving English speaking ability and language response fluency was evaluated.

4.2. Analysis of Learning Results

To evaluate the learning effectiveness of the proposed system, this study adopted a randomized controlled experimental design. Participants were randomly assigned to either an experimental group or a control group to compare learning outcomes under different instructional methods. The participants consisted of 100 junior and senior students from Feng Chia University, Taiwan. Their English proficiency levels were approximately equivalent to an IELTS score of 6.0–6.5, and they were placed in intermediate-level English courses based on the university’s English placement test. All participants had previously completed at least two semesters of required university English courses. According to self-reported language learning histories, the participants had studied English for an average of 14.2 years, and none had lived in an English-speaking country. This participant composition ensured a relatively consistent learning baseline, thereby minimizing the impact of individual differences on the experimental results.

Participants were randomly assigned to two groups: 50 in the experimental group and 50 in the control group. The experimental group used the English-speaking training system developed in this study and completed multiple practice sessions during the learning period. In contrast, the control group did not use the system; instead, they engaged in traditional English-learning activities, such as reading course materials, taking written notes, participating in classroom discussions, and conducting self-review.

To ensure experimental consistency, both groups were given the same learning duration, task content, and testing procedures. The only independent variable was whether the participants used the proposed system. Before formal learning began, all participants completed a pre-test using the system to obtain baseline performance scores and average response time, which served as the pre-test data. During the learning phase, the experimental group completed ten practice sessions, with the system automatically recording their performance scores and response times after each session. Learning effectiveness was evaluated using two key indicators:

- (1)

Whether test scores exhibited an upward trend as the number of practice sessions increased.

- (2)

Whether the average response time per item decreased progressively.

These two measures enabled us to evaluate the system’s impact on enhancing learners’ language proficiency and spoken fluency. After the learning phase, both groups completed the identical post-test, during which the system recorded their performance scores and average response time. By comparing the pre-test and post-test results, the effectiveness of the system in improving operational proficiency and language ability could be evaluated. The experimental results showed that participants in the experimental group exhibited significant improvements in test scores after repeated use of the system, and their average response time decreased substantially, indicating enhanced fluency in answering and task familiarity. These findings confirm the effectiveness of the proposed system in facilitating language learning and support our hypothesis that repeated interactive practice strengthens memory retention and improves operational efficiency, thereby demonstrating meaningful educational value.

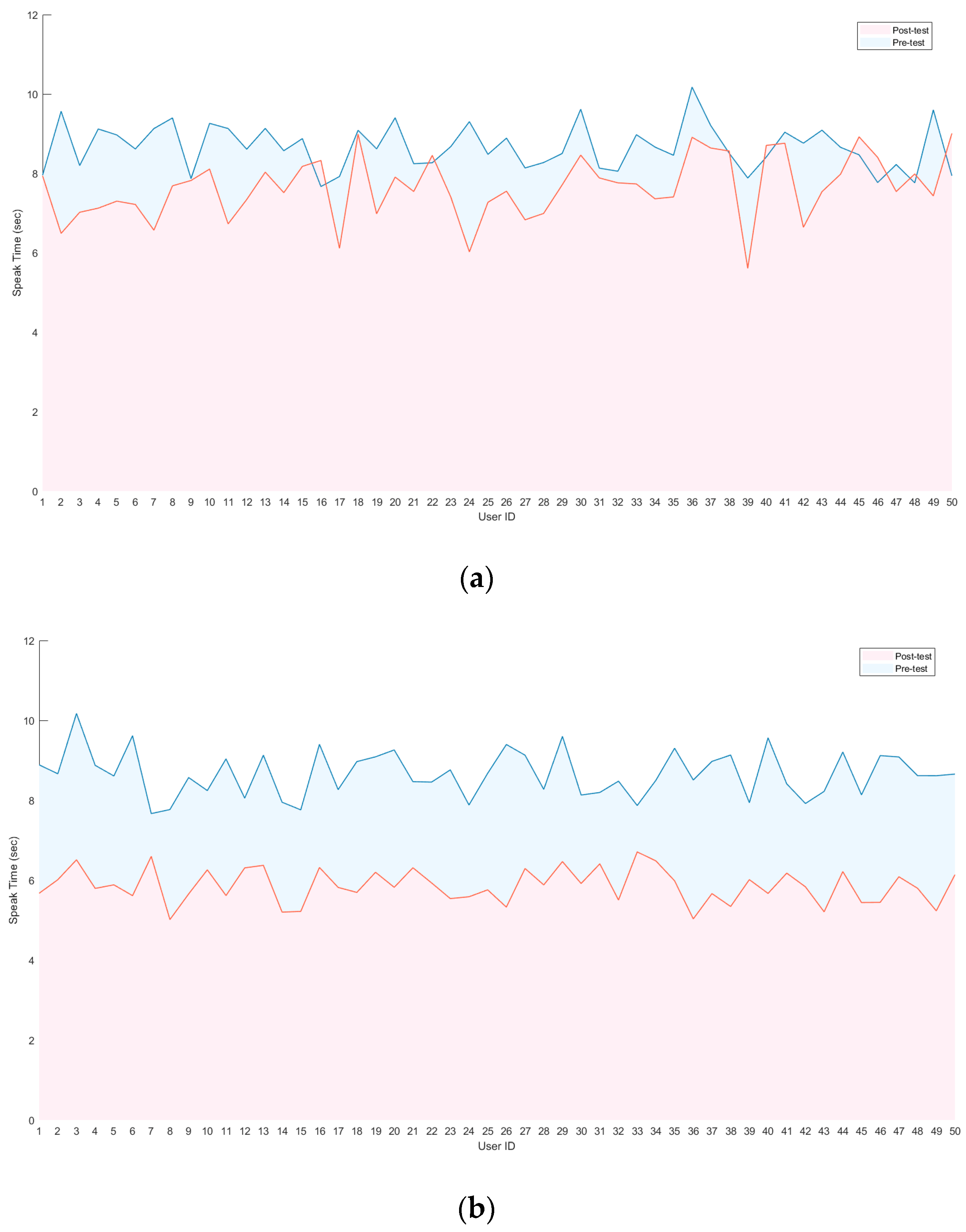

Figure 12a illustrates the distribution of average response times for the 50 participants in the control group during the pre-test and post-test. Although the control group showed a slight reduction in response time in the post-test, the degree of improvement was minimal, and substantial heterogeneity was observed across individuals. Some participants responded faster in the post-test than in the pre-test, suggesting that natural familiarity with the test content or general self-directed learning can still enhance oral English fluency to some extent. However, several participants exhibited longer response times in the post-test, indicating that without systematic training, learning outcomes are inconsistent. This pattern shows that traditional learning approaches (e.g., in-class practice, reading, note-taking, or self-practice) may offer limited improvement in language output fluency but cannot ensure uniform progress among learners within a short period. Moreover, performance is highly influenced by individual differences and variable learning strategies. In other words, the control group demonstrated only limited and unstable improvement in language response speed.

Figure 12b presents the changes in average response time for the 50 participants in the experimental group between the pre-test and post-test. All participants in the experimental group demonstrated reduced response times in the post-test, indicating that practice with the proposed oral training system led to substantial improvements in spoken fluency and reaction speed. The overall trend line shows a clear downward trajectory, with every participant responding more rapidly in the post-test. Furthermore, the variability in response times decreased compared with the pre-test, suggesting that the system produced consistent benefits across learners with different English proficiency levels. These results indicate that systematic, multi-round oral practice—incorporating speech-recognition feedback, real-time question responses, and speed-focused speaking exercises—effectively enhances the automaticity of language production, enabling participants to exhibit more fluent and faster spoken output in the post-test.

To estimate the accuracy distributions of the experimental and control groups in both the pre-test and post-test, this study employed Kernel Density Estimation (KDE). This non-parametric density estimation method does not require assumptions regarding the underlying probability distribution of the data. The kernel density estimator provides an estimated probability density function (PDF) for a random variable. For any real value x, the KDE is defined as

where

N denotes the sample size,

xi represents the

ith sample point, and

B is a smoothing parameter.

In this study, the Gaussian kernel was adopted, and its kernel function

K(

x) can be computed by

By substituting Equation (2) into Equation (1), the estimated probability density function (PDF) of the KDE can be expressed as

where

x denotes the point at which the density is to be estimated.

Using the KDE method allows the probability density function to be estimated from a finite set of samples and visualized in the form of kernel density plots. This method facilitates the comparison of distributional differences between pre-test and post-test scores as well as between groups.

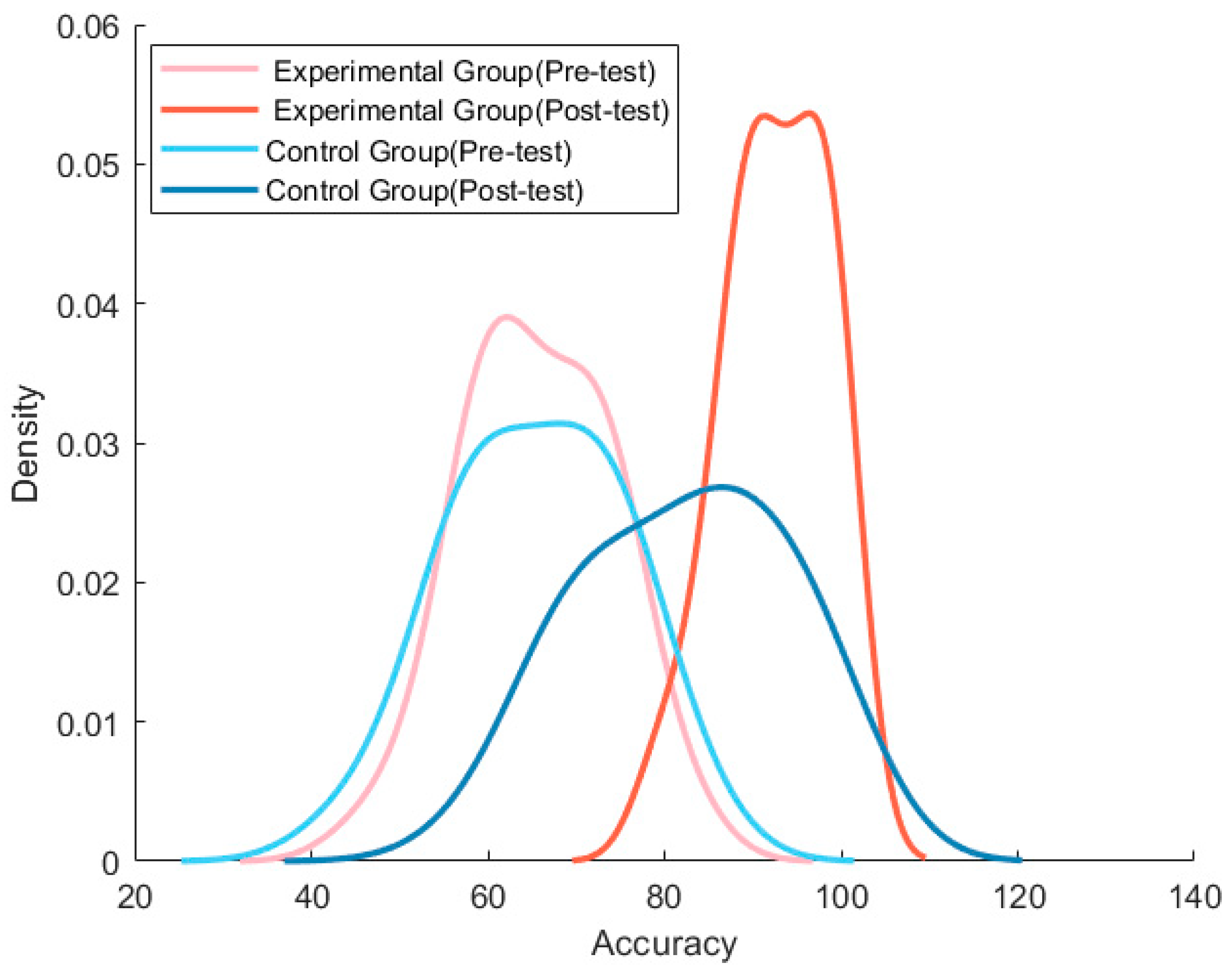

Figure 13 illustrates the accuracy distributions of both the experimental and control groups across the pre-test and post-test, estimated using Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) to visualize the shape and central tendency of the score distributions at each assessment stage.

The figure contains four density curves representing the experimental group (pre-test) and the experimental group (post-test), as well as the control group (pre-test) and the control group (post-test). At the pre-test stage, the two groups exhibit highly similar distributions, with density peaks concentrated around the 55–65% range, indicating comparable initial language proficiency prior to the intervention. In contrast, the post-test results reveal a pronounced divergence. The experimental group’s post-test distribution (dark red) shifts substantially to the right, with a sharp density peak near the 90% accuracy level. This result demonstrates not only a marked improvement in overall correctness but also a more concentrated distribution of scores, suggesting that learners consistently benefited from repeated practice with the proposed system. The sharper peak further indicates strengthened learning stability and homogeneity among participants. By comparison, although the control group’s post-test distribution (dark blue) also shifts to the right, its peak remains within the 70–85% range, reflecting a noticeably smaller improvement. Moreover, the control group’s distribution remains more dispersed, with the lower-accuracy tail extending further than that of the experimental group. This result suggests that some learners did not achieve meaningful progress through traditional or self-directed learning, resulting in greater variability in learning outcomes. Based on the KDE distributions shown in

Figure 13, several conclusions can be drawn:

The experimental group exhibits a substantial rightward shift and increased concentration in the post-test distribution, indicating that the proposed training system effectively enhances response accuracy.

The control group shows only moderate improvement, with considerable individual variability.

The clear divergence between the two groups in the post-test phase demonstrates the significant learning benefits provided by the system developed in this study.

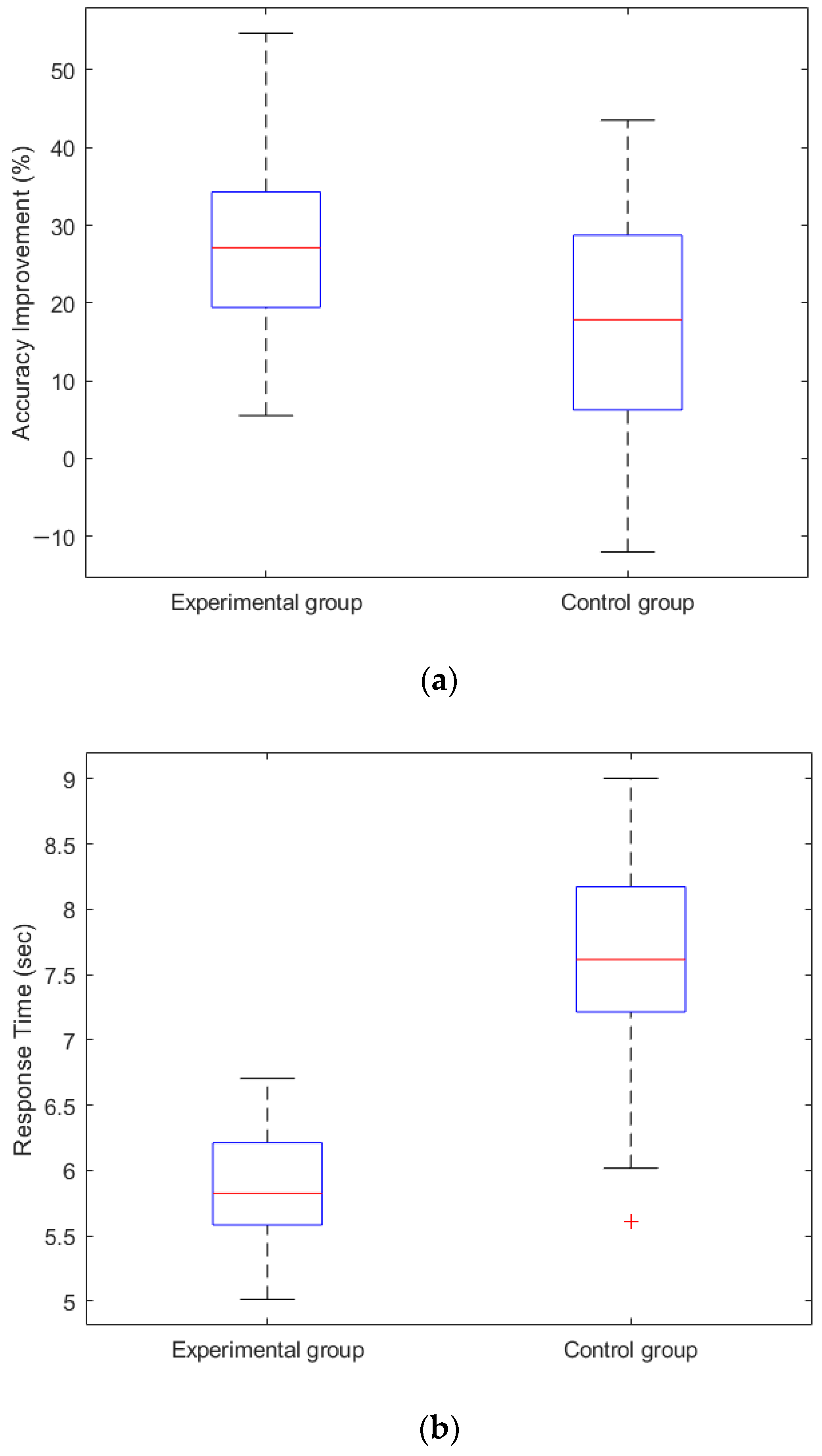

Figure 14a illustrates the distribution of accuracy improvement (post-test minus pre-test) for both the experimental and control groups. A notable disparity is apparent between the two groups. The median improvement for the experimental group is approximately 28%, substantially higher than the control group’s median improvement of about 18%, indicating that learners who used the proposed training system achieved more pronounced gains in spoken English accuracy. In addition, the interquartile range (IQR) of the experimental group is more compact and positioned noticeably higher than that of the control group, suggesting that the performance enhancement among experimental participants is more consistent and stable. Conversely, the control group exhibits a broader distribution, reflecting greater variability in learning outcomes; some participants even showed stagnation or decline in accuracy without systematic practice. Overall, the results presented in

Figure 14a demonstrate that the proposed English-speaking training system effectively enhances learners’ response accuracy, yielding not only larger improvement magnitudes but also reduced variability, thereby outperforming traditional learning approaches.

Figure 14b compares the average response time on the post-test between the experimental and control groups to evaluate differences in spoken English reaction speed and answering fluency. The results show that the median response time of the experimental group is approximately 5.8 s, which is significantly faster than the 7.6 s median observed in the control group. This difference indicates that learners who engaged with the proposed training system demonstrated a clear advantage in spoken English speed. Furthermore, the boxplot distribution reveals that the experimental group exhibits a narrower interquartile range, with most data concentrated between 5.5 and 6.2 s, suggesting stable and consistent answering speed. In contrast, the control group shows a much wider distribution range (approximately 6 to 8.8 s), indicating greater variability in reaction speed and less improvement in fluency when relying on traditional learning methods. The results presented in

Figure 14b support the hypothesis of this study: repeated practice using the proposed system can effectively enhance learners’ spoken English proficiency, leading to more fluent and rapid responses.

In this study, notched boxplots were employed to illustrate the differences in median performance between groups. The notches in the boxplot represent the 95% confidence interval of the median, estimated using the formula proposed by McGill et al. [

35]. Therefore, non-overlapping notches indicate a statistically significant difference at the α = 0.05 level.

Figure 15a presents the distribution of post-test accuracy scores for the experimental and control groups, using notched boxplots to facilitate group comparison. The plot shows that the median accuracy of the experimental group is approximately 93%, whereas the control group exhibits a significantly lower median of around 83%. The notches between the two groups do not overlap, indicating a statistically significant difference in median accuracy at the 95% confidence level.

Additionally, the experimental group demonstrates a more concentrated interquartile range and highly consistent performance, with maximum scores approaching 100%, suggesting that most learners achieved high accuracy after training with the proposed system. In contrast, the control group exhibits a broader distribution, with minimum scores falling below 60%, indicating substantial individual variability among learners using traditional study methods and suggesting that some participants did not achieve adequate proficiency.

Figure 15b compares the average post-test response times of the experimental and control groups using notched boxplots to highlight differences in median performance. The results show that the median response time of the experimental group is approximately 5.8 s, which is substantially faster than that of the control group, which is about 7.6 s. The non-overlapping notches between the two groups indicate a statistically significant difference in median response time at the 95% confidence level. Moreover, the experimental group exhibits a narrow distribution range, suggesting that most learners demonstrated consistent and improved oral response speed after using the proposed system. In contrast, the control group displays greater variability, with some participants requiring more than 8.5 s to respond even in the post-test, indicating that traditional learning strategies such as reading or independent practice are less effective in rapidly enhancing spoken fluency.

Figure 15b demonstrates that learners who trained with the proposed system achieved significantly faster and more fluent English oral responses, confirming the system’s effectiveness in improving spoken language fluency.

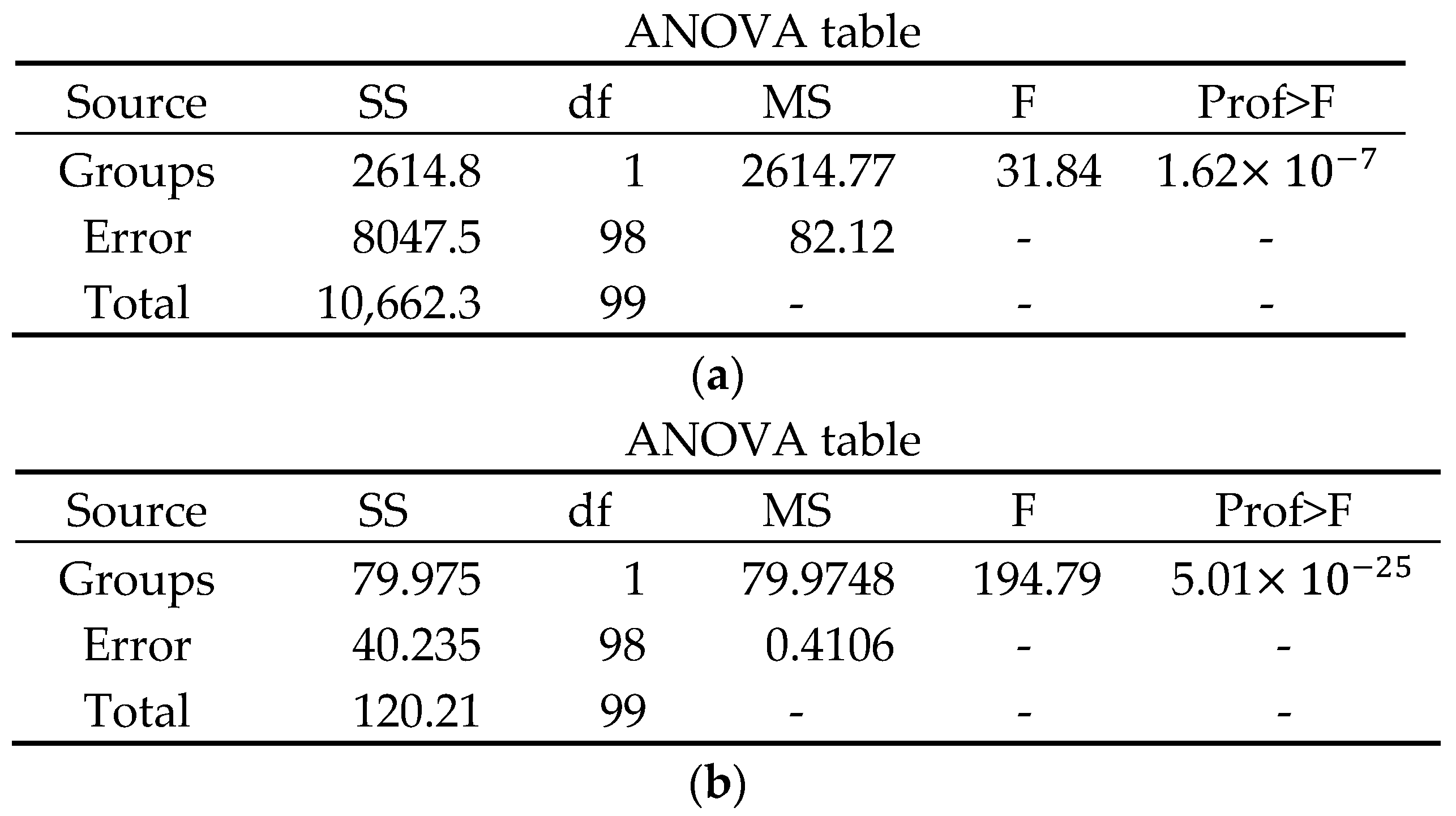

Figure 16a presents the results of a one-way ANOVA conducted on the post-test accuracy scores of the experimental and control groups. The between-group sum of squares (SS) was 2614.8, with a corresponding mean square (MS) of 2614.77. The within-group error sum of squares was 8047.5, yielding a mean square of 82.12. The resulting F-value was 31.84, with a

p-value of 1.6244 × 10

−7, which is highly significant at the α = 0.001 level. These results indicate a statistically significant difference in post-test accuracy between the two groups, demonstrating that the proposed training system produced a clear and measurable improvement in learners’ English-speaking accuracy. This finding is consistent with the distribution patterns observed in the boxplot in

Figure 15a, and the inferential statistical test further confirms that the observed group difference is unlikely to be attributed to random variation.

Figure 16b presents the ANOVA results for the post-test response times of the experimental and control groups. The between-group sum of squares was 79.975, with a corresponding mean square of 79.9748; the within-group error sum of squares was 40.235, yielding a mean square of 0.4106. The resulting F-value was 194.79, with an associated

p-value of 5.01317 × 10

−25, far below the 0.001 threshold. These statistical results indicate that the difference in response times between the two groups is not due to random variation but is substantially influenced by the use of the proposed system. In other words, the system significantly reduced learners’ English-speaking response times. This finding is entirely consistent with the trend observed in

Figure 15b, further confirming that the proposed system effectively improves English-speaking fluency.

The experimental results show that participants’ test scores increased significantly after multiple sessions of practice using the proposed system, while their average response time per item decreased markedly. These improvements indicate enhanced answer fluency and operational proficiency. The findings verify the effectiveness of the system in promoting English-speaking ability and support our hypothesis that repeated interactive practice using the proposed system can indeed facilitate substantial gains in spoken English performance.

4.3. Discussions

This study involved the assistance of a human rater (an experienced English instructor) to evaluate the responses—the human rater, who conducted the evaluations based on a rubric table.

Table 1 presents the rubric table used in this study to assess users’ English responses. The evaluation consists of four dimensions: sentence naturalness, semantic clarity, conformity of grammatical structure to native-speaker usage, and overall comprehensibility. The same rubric table was also provided to ChatGPT to ensure consistency in the scoring criteria.

For example, the reference answer provided by the AI agent was “I went to school yesterday.” When the participant responded with “I go to school yesterday,” the response was evaluated by a human rater using the rubric shown in

Table 1.

As summarized in

Table 2, the rubric score was 17 points (corresponding to an overall score of 85). The human rater’s qualitative feedback indicated that the response was generally understandable; however, it contained a grammatical error related to verb tense. Although the user’s intended message was conveyed successfully, semantic precision was compromised due to incorrect tense usage.

Table 3 presents the scoring results obtained using ChatGPT. The detailed explanations for each scoring dimension are as follows.

- (1)

Sentence naturalness

The sentence follows a commonly used conversational structure. The only issue lies in the incorrect verb tense, which does not match the temporal adverb yesterday. While a native speaker would recognize the response as produced by a non-native speaker, the sentence does not sound unnatural or awkward in context. Therefore, ChatGPT assigns a rubric score of 4 points (equivalent to 20 points).

- (2)

Semantic clarity

The meaning of the response is entirely clear, and the intended message—“going to school yesterday”—can be understood without any need for inference or guesswork. Accordingly, this dimension received the highest rubric score of 5 points (equivalent to 25 points).

- (3)

Grammatical completeness

The sentence exhibits a complete grammatical structure, consisting of a subject, a verb, an object, and a temporal adverb. However, the verb tense is incorrect (go instead of went), which constitutes a grammatical error. As a result, this dimension was assigned 4 points (equivalent to 20 points).

- (4)

Overall Comprehensibility

The response is entirely understandable and provides an appropriate answer to the question. Although it contains a grammatical tense error, the error does not hinder comprehension. The response can therefore be classified as “communicatively successful with minor grammatical errors.” This dimension received 5 points (equivalent to 25 points).

Although the sentence contains a verb tense error, its structure is complete, its meaning is clear, and it successfully addresses the prompt. The grammatical error does not impair overall understanding. Consequently, the response received the highest scores in semantic clarity and overall comprehensibility and is categorized as a comprehensible response with minor grammatical errors.

A comparison between the human rater’s evaluation and the ChatGPT assessment reveals both notable similarities and systematic differences. The similarities in scoring outcomes are as follows:

- (1)

Consistent judgment of communicative success

Both ChatGPT and the human rater agreed that the response successfully addressed the question. The core meaning—“going to school yesterday”—was conveyed clearly and unambiguously. Consequently, both evaluators classified the response as “communicatively successful despite grammatical errors” and assigned the highest scores for semantic clarity and overall comprehensibility. This consistency suggests that ChatGPT’s judgment, in terms of global understanding and communicative effectiveness, closely aligns with that of an experienced human rater.

- (2)

Shared interpretation of the nature of the grammatical error

The human rater noted that although the response contained an apparent grammatical defect, the error was isolated and did not affect the core meaning. Similarly, ChatGPT identified the verb tense error as a single grammatical mistake that did not interfere with the comprehension of the main message. Both evaluators therefore treated the error as a localized, non-fatal grammatical issue, rather than as evidence of a broader language ability deficiency. The differences in scoring outcomes are as follows:

- (1)

Differences in penalty strategy and grading strictness

The primary divergence emerged in the overall comprehensibility dimension: ChatGPT assigned a full score (5), whereas the human rater assigned a score of 4. This difference reflects the human rater’s greater emphasis on semantic precision, particularly with respect to temporal accuracy. From a pedagogical perspective, the tense error was considered to slightly compromise the precision of meaning, resulting in an additional penalty to the overall comprehension level.

- (2)

Divergent scoring orientations

ChatGPT employs a communication-oriented scoring logic, allowing for the clear inference of intended meaning. High scores are awarded, and errors are confined to the specific dimension in which they occur (e.g., grammar). In contrast, the human rater follows a more pedagogically oriented approach, whereby a single grammatical error may influence multiple evaluation dimensions, reflecting its potential instructional significance. This difference explains why the human rater’s total score (85) is slightly lower than ChatGPT’s score (90).

The above comparison demonstrates a high degree of agreement between ChatGPT and the human rater in terms of scoring trends and error characterization. Both evaluators judged the response to be communicatively successful and identified the grammatical issue as a single, non-critical error. The observed score discrepancy arises primarily from differing levels of strictness regarding the impact of grammatical errors on semantic precision, rather than from any fundamental disagreement about the learner’s language competence.

If no rubric table is provided and ChatGPT is used to assign scores directly, the resulting evaluations may exhibit huge variance. In contrast, when an explicit rubric table and scoring examples are provided, ChatGPT-4o demonstrates consistent and fair grading [

36]. The current ChatGPT-5.2 version exhibits even higher scoring stability; when used in conjunction with the rubric table, the assigned scores are both reasonable and stable.

To illustrate the application of the scoring rubric, we provide an example of a severely incorrect response. The question posed by the AI agent was: “What did you do over the weekend?” The user’s response was: “I weekend tomorrow because friend happy no money yesterday.”

Table 4 shows the scoring results.

The user’s final score was 20 points. The detailed evaluation by ChatGPT version 5.2 is as follows:

The word order does not conform to standard English usage. The verb usage is incorrect (“I weekend” is not a valid verb phrase), and the tense usage is inconsistent, with “tomorrow” and “yesterday” appearing simultaneously. Native speakers would rarely use such a sentence structure. Score: 1 point.

- (2)

Semantic clarity

It is impossible to determine with certainty what the user did over the weekend. The causal relationship expressed in “because friend happy no money” is semantically unclear, and the reader must rely heavily on guesswork to infer any meaning. Score: 1 point.

- (3)

Grammatical completeness

The response lacks a complete sentence structure, with no correct subject–verb construction. Verb tense usage is incorrect, and conjunctions and relational words are misused. Score: 1 point.

- (4)

Overall Comprehensibility

Even when considering the surrounding context, the response remains difficult to understand and fails to effectively answer the question (i.e., it does not state what was done over the weekend). This response falls into the category of communication failure. Score: 1 point.

Because the participant’s response exhibits severe deficiencies in grammatical structure, semantic expression, and sentence naturalness, and fails to address the question meaningfully, the overall comprehensibility is exceptionally low. Consequently, the response received the lowest rating (1 point) across all four evaluation dimensions, resulting in a rubric score of 4 points and a final scaled score of 20 points, representing a case of severe communication failure.

Although the primary scoring mechanism in this study is conducted automatically by the proposed ChatGPT-based evaluation system, human evaluation was included as a supplementary validation reference. It should be acknowledged that the human assessment relied on a single experienced rater, which may limit inter-rater reliability and the generalizability of the validation results. However, this design choice was intentional, as the role of human scoring in this study was not to serve as the primary evaluation standard, but rather to verify the consistency and plausibility of the AI-generated scores. The human rater followed a predefined and consistent rubric to minimize subjective bias. Future work will incorporate multiple human raters and inter-rater agreement analysis to further strengthen the robustness of the validation process.

Concerning the system latency, the response delay—from the moment the user finishes speaking to the system displaying the GPT-generated reply—ranges from a minimum of approximately 2 s to an average of 10 s, which is acceptable for interactive language-learning applications.

The cost of using GPT as the primary response-generation engine is relatively low. Under a credit-based usage model, each query consumes approximately 210 tokens, resulting in a monthly cost of less than USD 2.5. In contrast, video-generation services such as D-ID incur higher expenses, averaging USD 7.5 per month. The combined operational cost for running both services is approximately USD 10 per month, making the system cost-efficient and sustainable.

In terms of scalability, the system architecture allows for future expansion and enhancement. Planned improvements include integrating AI-driven pronunciation analysis and computer vision modules, expanding platform compatibility, leveraging cloud-based deployment, and supporting additional languages to meet broader educational and commercial needs.

Concerning the speech recognition reliability, the speech recognition module employed in this system achieves a recognition accuracy of approximately 97%, providing a reliable foundation for downstream tasks such as scoring, feedback generation, and learning analytics.

The reliability of the proposed system’s scoring remains limited by the accuracy of speech recognition and occasional inconsistencies in GPT-based evaluation. Future work will expand the scoring dimensions, improve the system’s robustness to diverse accents, and validate it with broader learner populations.

During the experimental phase, all participants read and signed an informed consent form prior to using the system. The consent form explained that their speech data would be collected for research purposes, clarified that the audio recordings would be transmitted to and processed by a third-party cloud service (ChatGPT), and stated explicitly that participants retained the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

This study falls under the category of exempt research, as it involves a small-scale, voluntary participation test during the proof-of-concept stage and does not include any sensitive personal information or interventional procedures. Accordingly, a formal Institutional Review Board (IRB) review was not required. Nevertheless, we adhered strictly to all applicable ethical principles throughout the study.

This study incorporates a comprehensive ethics statement and data protection protocol to safeguard the rights and privacy of participants. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. The ethical declaration clearly specifies that all collected speech data were used exclusively for research purposes and were de-identified (anonymized) before analysis. In accordance with the data protection policy, all research data will be permanently destroyed upon completion of the study.

Although the proposed system employs cloud-based speech recognition services, no personally identifiable information is collected, stored, or processed at any stage. The uploaded voice data are used solely for transient speech-to-text conversion. They are not linked to user names, identifiers, biometric information, or any metadata that could enable individual identification. The system does not perform speaker identification or voiceprint analysis, and audio inputs are not retained after recognition is completed. The recognized speech content is used only for linguistic evaluation and feedback generation. Consequently, the processed data cannot be traced back to specific individuals, and the risk of privacy infringement is minimal. The study, therefore, adheres to the relevant ethical guidelines for research involving non-identifiable data.