One-Dimensional Simulation of PM Deposition and Regeneration in Particulate Filters: Optimal Conditions for PM Oxidation in GPF Considering Oxygen Concentration and Temperature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Calculation Model

2.1. Exhaust Gas Flow in the Axial Direction (x-Direction) of the GPF

2.2. PM Deposition Within the GPF Wall

2.3. Treatment of Temperature

2.4. PM Oxidation

2.5. Calculation for Mode Operation with Additional FC Operation

2.6. Catalytic Reaction and Gas-Phase O2 Reaction

3. Results

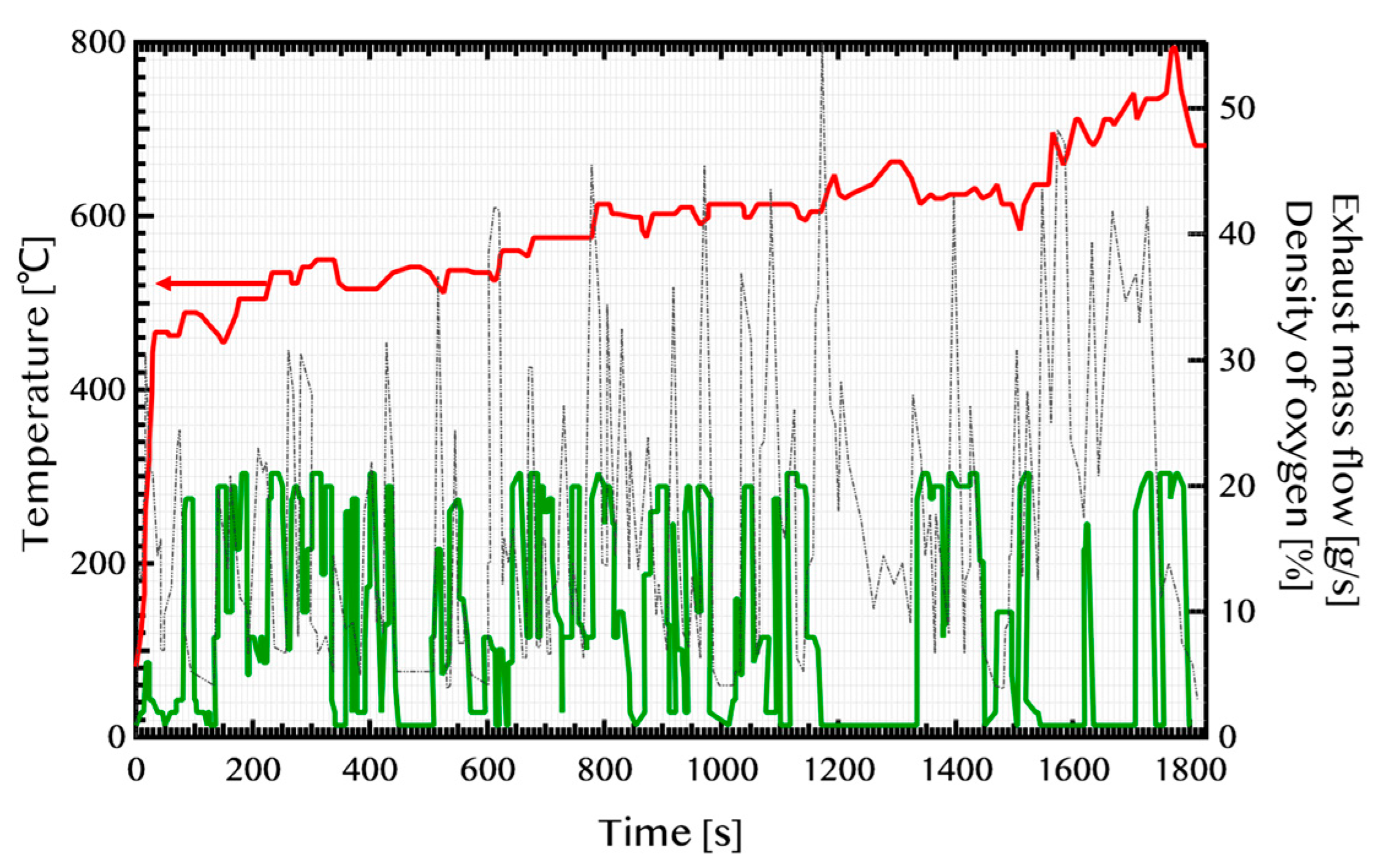

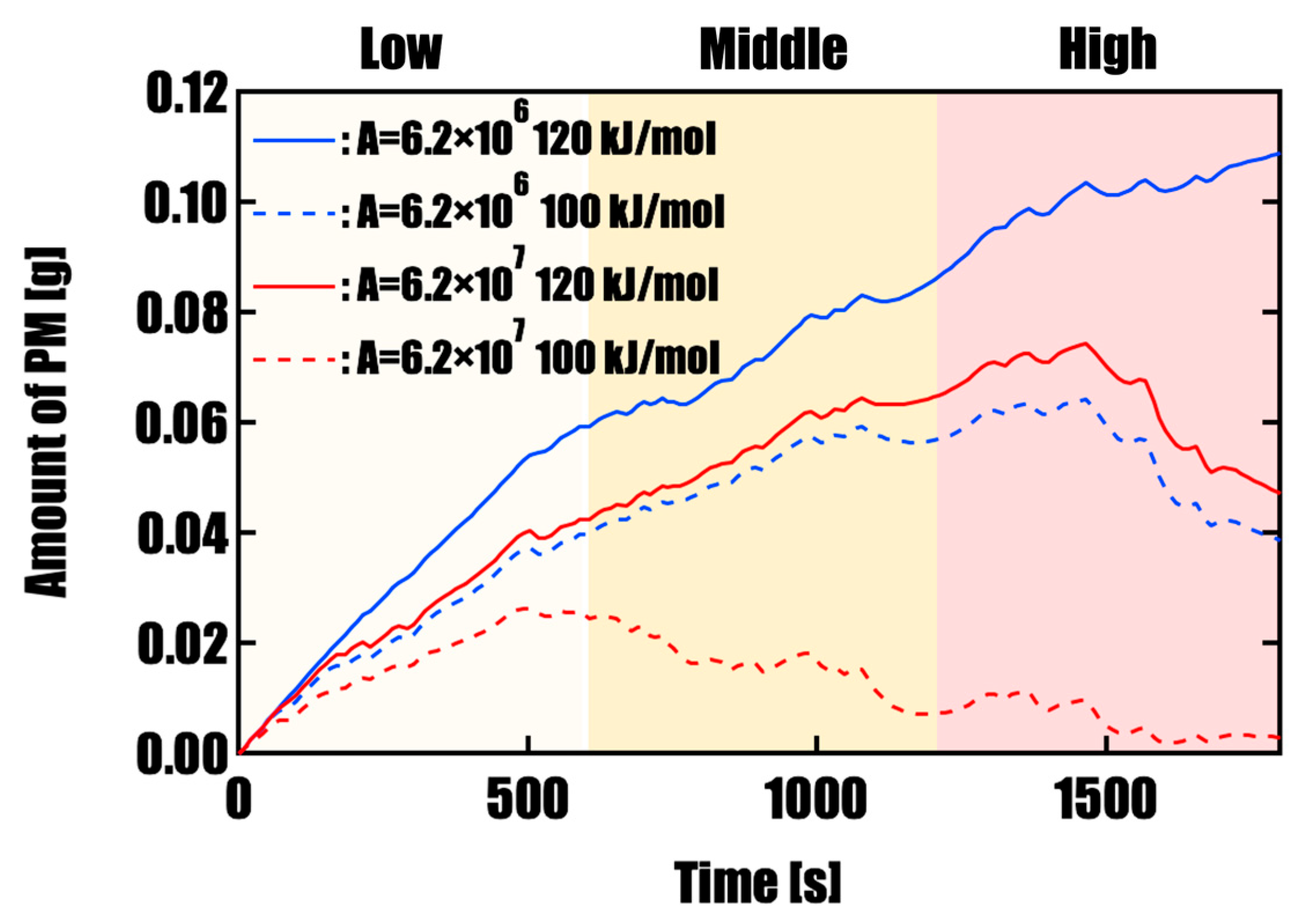

3.1. Effect of Activation Energy on PM Oxidation Performance

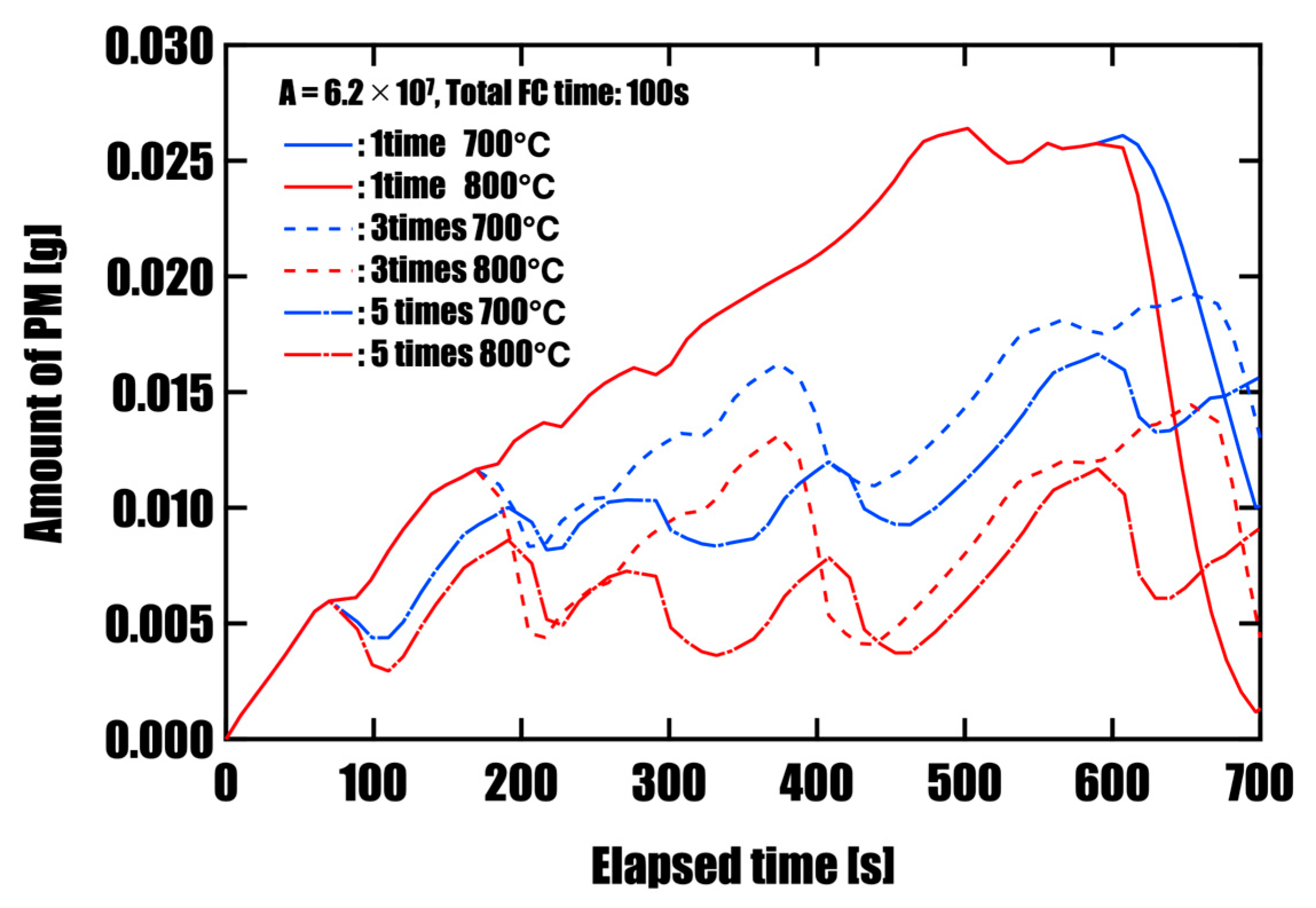

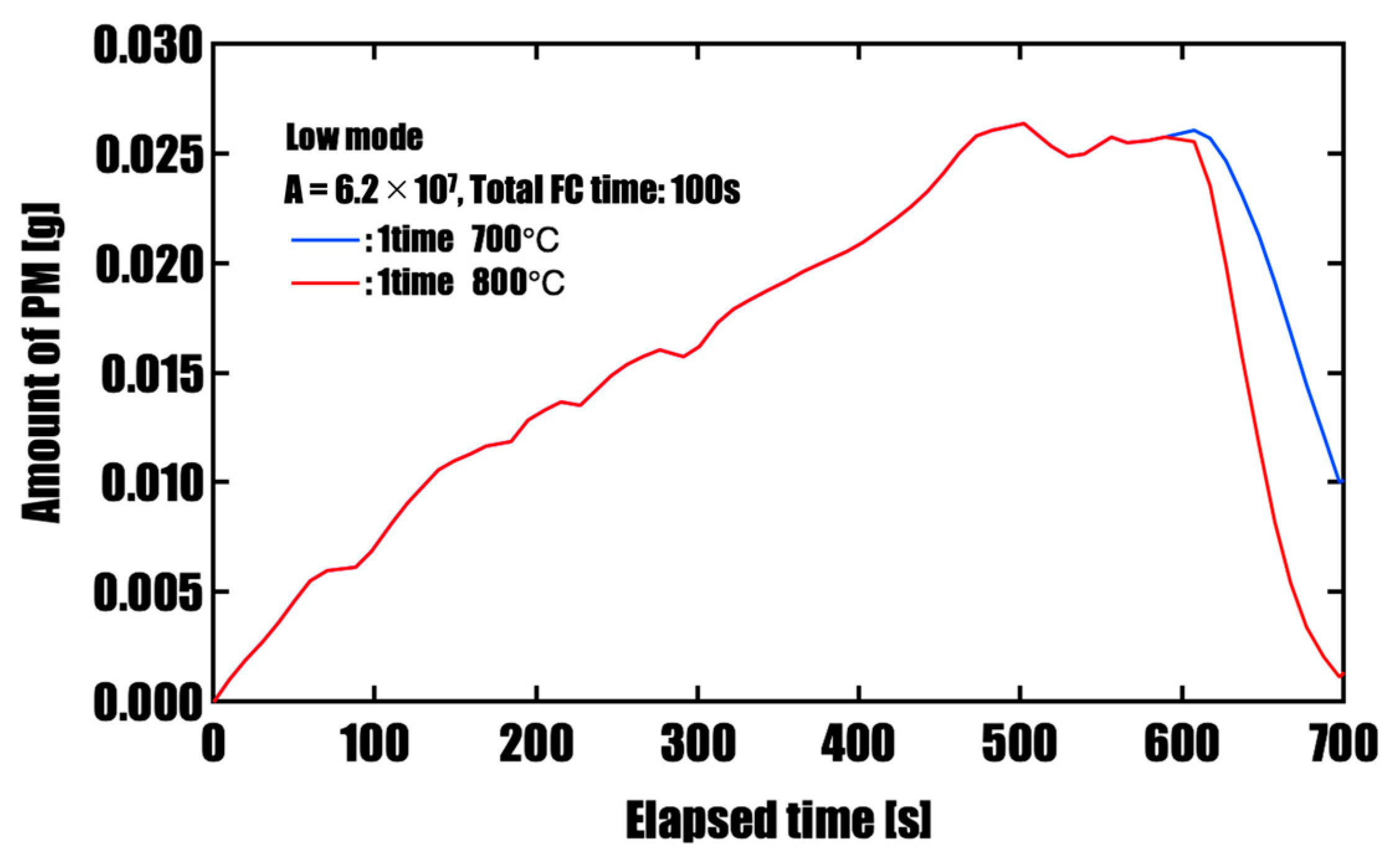

3.2. Effect of Forced Fuel Cut (FC) on PM Oxidation

4. Conclusions

- Effect of Catalyst Performance (Activation Energy and Pre-exponential Factor)Simulations under four different conditions, varying activation energy (E) and pre-exponential factors (A), revealed that PM oxidation performance highly depends on catalyst activity. Under high-activity conditions (E = 100 kJ/mol, A = 6.2 × 107), an oxidation rate of 98.8% was achieved within a single WLTC, and the final residual PM mass was as low as 0.003 g. In contrast, under conventional catalyst performance (E = 120 kJ/mol, A = 6.2 × 106), oxidation was insufficient, with residual PM reaching 0.11 g, highlighting the limitations in regeneration under such conditions.

- Effectiveness of Forced Fuel Cut (FC) IntroductionUnder conditions of limited catalyst performance, temporarily raising the exhaust oxygen concentration to 20% through forced fuel cut (FC) was shown to promote PM oxidation effectively. This is especially so in the low-speed mode, where exhaust temperatures remain around 500 °C, introducing a single continuous 100 s FC event yielded the highest oxidation effect, reducing PM by approximately 96%. This is attributed to the synergistic effects of sustained oxygen supply and heat release from oxidation reactions, which accelerated and maintained the reaction. On the other hand, when FC was divided into three or five intervals, the oxidation rate slightly decreased, but peak PM accumulation was effectively suppressed. This suggests that a split FC introduction may help reduce pressure drop and improve filter regeneration stability. Therefore, optimizing the FC strategy is crucial to meet multiple performance demands, such as regeneration efficiency and pressure loss reduction, and strategic control tailored to the operating conditions is required.

- Future Issues and OutlookThe present model analyzed regeneration behavior separately for each speed phase. Future work must include continuous PM accumulation calculations, catalyst aging effects, and exhaust gas fluctuations to more accurately simulate real driving conditions. Moreover, for the practical implementation of forced FC, a comprehensive evaluation of control feasibility, user impact, and safety will be essential.Based on the above, the numerical analysis has demonstrated that combining catalyst activity and engine control utilizing fuel cut can effectively improve GPF regeneration performance in GDI vehicles. These findings provide valuable technical insight that may guide the future development of regeneration control algorithms and the design of thermally durable catalysts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cg | Specific heat of exhaust gas [J/(kg·K)] |

| D | Diameter of GPF [m] |

| dc | Density of cordierite [kg/m3] |

| E | Activation energy [J/mol] |

| ΣF | Total flow rate [m3/s] |

| i | Cell number in x-direction [-] |

| j | Number in y-direction (wall thickness direction) within each cell i [-] |

| L | Total length of GPF [m] |

| N | Cell number counted from the inlet in x-direction [-] |

| PM | Amount of particulate matter (PM) [mol] |

| Q | Heat capacity [J/K] |

| R | Gas constant [J/(K·mol)] |

| Rpm | Amount of PM reaction [mol] |

| S | Flow amount of gas [kg] |

| T | Temperature used in PM combustion reaction rate equation [°C] |

| Tw | Wall temperature [°C] |

| TR | Corrected temperature [°C] |

| TPM | PM combustion heat temperature [°C] |

| ΔT | Temperature change [°C] |

| V | Volume of computational unit cell [m3] |

| vi | Flow velocity [m/s] |

| VO2 | O2 concentration [mol/m3] |

| WT | Wall thickness of GPF [m] |

| α | Superficial velocity of each cell [m/s] |

| μ | Permeability of GPF wall [-] |

| σ | Cross-sectional area of each cell [m2] |

| φ | Porosity [-] |

| λ | Pipe friction coefficient [-] |

| ρ | Fluid density [kg/m3] |

| Lwp+PM | Length [m] |

| Dwalls | Diameter [m] |

References

- Samaras, Z.C.; Kontses, A.; Dimaratos, A.; Kontses, D.; Balazs, A.; Hausberger, S.; Ntziachristos, L.; Andersson, J.; Ligterink, N.; Aakko-Saksa, P.; et al. A European Regulatory Perspective towards a Euro 7 Proposal. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Pr. Mobil. 2022, 5, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.; Goodwin, J. Impact of the Proposed Euro 7 Regulations on Exhaust Aftertreatment System Design. Johns. Matthey Technol. Rev. 2023, 67, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, A.; Salavert, M.J.; Palau, G.E.; Guardiola, C. Analysis of the Euro 7 on-board emissions monitoring concept with real-driving data. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 127, 104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giechaskiel, B.; Melas, A.; Valverde, V.; Otura, M.; Martini, G. Challenging Conditions for Gasoline Particulate Filters (GPFs). Catalysts 2022, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Environmental Studies, Research Project Report No. 123. Available online: https://www.nies.go.jp/kanko/tokubetu/pdf/sr-123.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025). (In Japanese).

- Kwon, H.; Ryu, H.M.; Carlsten, C. Ultrafine particles: Unique physicochemical properties relevant to health and disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akihama, K. Particulate Matter Regulations and the Need for Modeling. J. Combust. Soc. Jpn. 2017, 59, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Giechaskiel, B.; Valverde, V.; Kontses, A.; Melas, A.; Martini, G.; Balazs, A.; Andersson, J.; Samaras, Z.; Dilara, P. Particle Number Emissions of a Euro 6d-Temp Gasoline Vehicle with GPF under Wide Range of Conditions. Catalysts 2021, 11, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.; Park, S. Reduction of Particle Emissions from Gasoline Vehicles with Direct Fuel Injection Systems Using a Gasoline Particulate Filter. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 1418–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Deng, C.; Gao, Y.; He, Y. Diesel Particulate Filter Design Simulation: A Review. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2016, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.W.; Saffaripour, M.; Liu, F.; Hendren, J.; Thomson, K.A.; Kubsh, J.; Brezny, R.; Rideout, G. Characterization of Real-Time Particle Emissions from a Gasoline Direct Injection Vehicle Equipped with a Catalyzed Gasoline Particulate Filter During Filter Regeneration. Emiss. Control Sci. Technol. 2016, 2, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, N.R.H.; Baum, M.M.; Moss, J.A.; Castonguay, A.E.; Jocic, S.; Northrop, W.F. Dicarboxylic Acid Emissions from a GDI Engine Equipped with a Catalytic GPF. Fuel 2020, 275, 117940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yan, F.; Fang, N.; Yan, D.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W. An Experimental Investigation of the Impact of Washcoat Composition on Gasoline Particulate Filter (GPF) Performance. Energies 2020, 13, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Song, B.; Quan, Y. Effect of Oxidation Temperature on Oxidation Reactivity and Nanostructure of Particulate Matter from a China VI GDI Vehicle. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 256, 118461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Meng, Z.; Peng, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, Z.; Mao, J.; Fang, J. Effect of Different Aging Conditions on the Soot Oxidation by Thermogravimetric Analysis. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 30568–30576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, G.; Saleh, R.; Zhao, Y.; Presto, A.A.; Lambe, A.T.; Frodin, B.; Sardar, S.; Maldonado, H.; Maddox, C.; May, A.A.; et al. Comparison of Gasoline Direct-Injection (GDI) and Port Fuel Injection (PFI) Vehicle Emissions: Emission Certification Standards, Cold-Start, Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation Potential, and Potential Climate Impacts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 10302–10311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolin, P.; Rose, D.; Kunath, F.; Boger, T. Modeling of the Soot Oxidation in Gasoline Particulate Filters. SAE Int. J. Engines 2015, 8, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boger, T.; Rose, D.; Nicolin, P.; Gunasekaran, N.; Glasson, T. Oxidation of Soot (Printex® U) in Particulate Filters Operated on Gasoline Engines. Emiss. Control Sci. Technol. 2015, 1, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, H.; Pozzato, G.; Hoffman, M.A.; Onori, S. Modeling the Thermal and Soot Oxidation Dynamics Inside a Ceria-Coated Gasoline Particulate Filter. Control Eng. Pract. 2020, 94, 104199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, Y.; Huang, H.; Cao, C. Review of Particle Filters for Internal Combustion Engines. Processes 2022, 10, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinharter, C. Investigation of Gasoline Particulate Filters (GPF) System Requirements and Their Integration in Future Passenger Car Series Applications. Master’s Thesis, University of Graz, Graz, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stanmore, B.R.; Brilhac, J.F.; Gilot, P. The Oxidation of Soot: A Review of Experiments, Mechanisms and Models. Carbon 2001, 39, 2247–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, E.; Palma, V. Most Recent Advances in Diesel Engine Catalytic Soot Abatement: Structured Catalysts and Alternative Approaches. Catalysts 2020, 10, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, L.; Landi, G.; Di Sarli, V. The Issue of Soot–Catalyst Contact in Regeneration of Catalytic Diesel Particulate Filters. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Lv, X.; Wang, Y.; He, L.; Wang, Y.; Fu, K.; Liu, Q.; Wang, K. Experimental Investigation of Diesel Soot Oxidation Reactivity Along the Exhaust After-Treatment System Components. Fuel 2021, 302, 121047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawatmongkhon, B.; Promhuad, P.; Thaisruang, T.; Theinnoi, K.; Sittichompoo, S.; Wongchang, T.; Sukjit, E. Kinetic Analysis of Devolatilized Diesel-Soot Oxidation Catalyzed by Ag/Al2O3 and Ag/CeO2 Using Isoconversional and Master-Plots Techniques. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 29437–29447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiguro, T.; Takatori, Y.; Akihama, K. Microstructure of Diesel Soot Particles Probed by Electron Microscopy First Observation of Inner Core and Outer Shell. Combust. Flame 1997, 108, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiabudi, A.; Makkee, M.; Moulijn, J.A. The role of NO2 and O2 in the oxidation of diesel soot over Pt catalysts. Appl. Catal. B 2004, 50, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehliu, K.; Vander Wal, R.L.; Armas, O.; Boehman, A.L. Impact of Fuel Formulation on the Nanostructure and Reactivity of Diesel Soot. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 6188–6198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Ozawa, M. Phenomena of PM Deposition and Oxidation in Diesel Particulate Filters; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, M.; Yokota, K.; Ozawa, M. Numerical Calculation of PM Trapping and Oxidation of Particulate Filter-Considering Operation Mode of the Engine. J. Automot. Eng. 2022, 53, 360–365. (In Japanease) [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, M.; Yokota, K.; Ozawa, M. Numerical Calculation Optimization for PM Trapping and Oxidation of Catalytic DPF. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Yokota, K.; Okai, K.; Ozawa, M. Development of Converter Model for Catalysts in Particulate Filters. J. Automot. Eng. 2023, 54, 242–247. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Sanui, R.; Hanamura, K. Electron microscopic time-lapse visualization of surface cavity filtration in the particulate matter trapping process. J. Microsc. 2016, 263, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Guo, W.; Yin, M.; Xi, W.; Sunden, B. Flow and heat transfer characteristics of regenerative cooling channels using supercritical CO2 with circular tetrahedral lattice structures. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 71, 106204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency Factor: A | Activation Energy: E [kJ/mol] | |

|---|---|---|

| SSR | 6.2 × 107, 6.2 × 106 | 100, 120 |

| GPR | 2 × 109 | 195 |

| Number of FC Installations | Temperature [℃] | Maximum Deposited Volume [g] | Final Residual Volume [g] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 time (100 s) | 700 | 0.026 | 0.010 |

| 1 time (100 s) | 800 | 0.026 | 0.001 |

| 3 times (30 + 30 + 40 s) | 700 | 0.019 | 0.013 |

| 3 times (30 + 30 + 40 s) | 800 | 0.019 | 0.004 |

| 5 times (20 s × 5) | 700 | 0.016 | 0.016 |

| 5 times (20 s × 5) | 800 | 0.016 | 0.009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nakamura, M.; Yokota, K.; Ozawa, M. One-Dimensional Simulation of PM Deposition and Regeneration in Particulate Filters: Optimal Conditions for PM Oxidation in GPF Considering Oxygen Concentration and Temperature. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010150

Nakamura M, Yokota K, Ozawa M. One-Dimensional Simulation of PM Deposition and Regeneration in Particulate Filters: Optimal Conditions for PM Oxidation in GPF Considering Oxygen Concentration and Temperature. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010150

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakamura, Maki, Koji Yokota, and Masakuni Ozawa. 2026. "One-Dimensional Simulation of PM Deposition and Regeneration in Particulate Filters: Optimal Conditions for PM Oxidation in GPF Considering Oxygen Concentration and Temperature" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010150

APA StyleNakamura, M., Yokota, K., & Ozawa, M. (2026). One-Dimensional Simulation of PM Deposition and Regeneration in Particulate Filters: Optimal Conditions for PM Oxidation in GPF Considering Oxygen Concentration and Temperature. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010150