1. Introduction

Phase transitions are fundamental phenomena across diverse chemical, physical, and biological systems, characterized by abrupt changes in macroscopic properties and often by the emergence of new orders or broken symmetries. Familiar examples span the solid–liquid–gas transitions, magnetic ordering (e.g., ferro-, antiferro-, and ferrimagnetism), and the macroscopic quantum phenomena of superconductivity and superfluidity. Such transitions can occur at finite temperatures by varying thermodynamic parameters like pressure, or even at absolute zero by tuning external fields (e.g., magnetic, electric) or chemical potential. Transitions occurring at zero temperature, known as quantum phase transitions (QPTs), involve a singular transformation of the system’s ground state. While experimentally inaccessible, the critical fluctuations of QPTs profoundly influence material behavior at finite temperatures, making their study crucial for understanding emergent phenomena.

Among QPTs, the metal–insulator transition (MIT) is of paramount importance. At zero temperature, the distinction is clear: insulators exhibit diverging resistivity, while metals maintain a finite, constant value. Although resistivity is finite for both at non-zero temperatures, the MIT is fundamentally considered a quantum phenomenon [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, many systems display sharp, often multi-order-of-magnitude jumps in conductivity at finite temperatures, necessitating an extension of the MIT concept to finite temperatures [

3]. The MIT manifests in a wide array of materials, including doped semiconductors, semiconductor heterostructures (e.g., GaAs/AlGaAs) [

4], organic conductors (e.g.,

-

) [

5], and, in particular, strongly correlated transition metal oxides (e.g.,

,

) [

6,

7,

8], as well as other transition metal compounds (e.g., NiSSe, Nb) [

9,

10].

According to the standard viewpoints of solid state physics [

11], the metal–insulator transition (MIT) is described by the band filling mechanism. This theory describes a material’s electronic structure by calculating energy bands based on a periodic potential and, crucially, treating electrons as non-interacting particles. It predicts that a material is a metal if the highest energy band is partially filled (free movement of electrons), which allows electrical conductivity, while its density of states (DOS) is high at the Fermi level; it also predicts that it is an insulator if the band is completely filled and separated from the next by a band gap. By continuously changing the band structure, either by applying pressure, a displacement field, or even due to spontaneous symmetry breaking, a band-tuned metal–insulator transition can be obtained [

12]. This principle is the key physics behind the conductive switching in a transistor. However, this theory fails when electron–electron interactions significantly influence the physical properties, which is especially true in compounds containing partially filled

d or

f bands like transition metal oxides (NiO or

). Several mechanisms describe the metal–insulator transition when the band theory fails to describe the behavior. One mechanism is Anderson localization [

13], where disorder localizes electron wave functions even in the absence of interactions. A well-established scaling theory [

14] shows that for dimensions

(excluding spin-orbit or spin-inversion potentials), all states are localized with any amount of disorder. For

, a critical disorder strength is required for the transition. Another mechanism is the Mott transition [

15], which arises from strong electron–electron interactions even in a perfectly clean system. Originally conceived with long-range Coulomb interactions, the Mott transition is also observed in the Hubbard model [

16,

17,

18] when strong short-range interactions exist at half-filling. Despite significant efforts [

19,

20,

21,

22], a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between disorder and interactions in driving the MIT remains a complex and open problem.

Early theoretical descriptions of the Mott transition, such as Hubbard’s initial approach [

16,

17,

18], began from an insulating “atomic limit” and predicted a transition to a metallic state upon weakening interactions, marked by the closing of the Mott gap between Hubbard bands. Conversely, Brinkman and Rice [

23], utilizing a Gutzwiller variational wave function [

24], described the collapse of a correlated metal with increasing interactions, leading to the disappearance of Fermi liquid quasi-particles. However, both models were incomplete: Hubbard’s failed to capture correlated metal quasi-particles, while Brinkman and Rice’s did not predict Hubbard bands. Experimental observations, particularly from optical conductivity, consistently show both phenomena, highlighting the limitations of these early theories.

Dynamical Mean-Field Theory (DMFT) [

25,

26] provided a breakthrough, offering a unified framework that reconciles the insights of both Hubbard and Brinkman–Rice. DMFT uniquely incorporates both low-energy Fermi liquid quasi-particles and high-energy Hubbard bands for intermediate interaction strengths (

U). Within this description, the Mott transition is a first-order phase transition characterized by the abrupt disappearance of quasi-particles, leaving only Hubbard band excitations. This transition exhibits a region of metal–insulator coexistence, analogous to supercooling/superheating in liquid–gas transitions. The first-order line in the temperature-versus-

U phase diagram culminates at a second-order critical point

, where the sharp jump in resistivity diminishes with increasing temperature and vanishes. These striking parallels underscore the profound connection between the DMFT-described Mott transition and universal liquid–gas transitions. The canonical Hubbard model [

16,

17,

18], treated with DMFT [

26] and Statistical Dynamical Mean Field Theory (StatDMFT) when adding disorder [

27,

28], provides an ideal platform for accurately mapping out these phase transitions [

29,

30,

31]. The computational process typically involves solving the DMFT impurity problem to obtain Matsubara frequency Green’s functions, often using Quantum Monte Carlo [

32], followed by analytical continuation to the real frequency domain for physical interpretation.

This paper extends our previous work by investigating the intricate interplay between electron–electron interactions and disorder along the metal–insulator transition in a two-dimensional lattice [

30,

33]. Specifically, we employ the Hubbard model augmented with disorder and statistical dynamical mean-field theory to explore how these two competing mechanisms govern the phase transition characteristics. Our study aims to shed light on the emergent behavior in this complex, correlated disordered system.

2. Materials and Methods

The Hubbard model is the simplest model capable of capturing the Mott metal–insulator transition (MIT),

Here, the operator

creates an electron of spin

in the i-th orbital,

t is the tunneling element describing the inter-orbital hybridization,

implies first neighbor. A purely imaginary second nearest-neighbor hopping

is introduced in order to move the van Hove singularity away from the middle of the clean non- interacting band, while maintaining particle– hole symmetry [

30]. We set

.

U accounts for a local Coulomb repulsion, and

are random variables distributed according to a uniform probability distribution from

to

,

for the clean case and

for the disordered case.

Within the single-site DMFT framework, electronic correlations are treated via the assumption of a site-local, frequency-dependent self-energy. This assumption, when applied to a disordered lattice, leads to an approximation of self-energy that depends only on each specific site:

[

30].

The local dynamics of any site

i are governed by its effective actions

where

, and

represents the “cavity” function characterizing single-particle hopping from and toward site

i. Solving the effective action in Equation (

2) allows us to obtain the local interacting Green’s function, which is defined by

and is linked to the self-energy as follows,

The iterative self-consistency scheme built upon Equations (

2) and (

3), is employed for each site of a finite

disordered lattice. This process begins with an initial guess for the

hybridization functions

, which in turn define the

effective actions (Equation (

2)). Subsequently, the Quantum Monte Carlo algorithm of Hirsch and Fye [

32] serves as an impurity solver to compute the

local interacting Green’s functions. From the latter, the respective local self-energies can be deduced, using Equation (

3).

This ensemble of local self-energies updates the “cavity” functions through the relation

Here,

denotes the identity matrix, and

is a diagonal matrix with elements

. These local self-energies effectively renormalize the bare site energies, with the addition of a frequency-dependent term, reflecting the influence of electron–electron interactions. In the context of the single-site DMFT-based approach, this renormalization solely describes local, single-particle processes. The lattice Green’s function

(from Equation (

4)) is obtained by numerically inverting the non-Hermitian operator in the denominator. This inversion is performed for each frequency in the site basis, independently, using standard linear algebra routines. The diagonal elements of the resulting

correspond to the updated local Green’s functions,

, from which the new cavity functions

are derived

These, in turn, are used to update the set of effective actions

, thus closing the self-consistency loop. This complete, self-consistent scheme is known as statistical dynamical mean field theory (statDMFT).

We implemented the statDMFT approach to investigate the disordered Mott transition in the two-dimensional Hubbard model at half-filling. Our study considered various disorder strengths

, where

serves as the energy unit [

30]. All calculations were performed at fixed temperature

. For the impurity problem, we utilized the Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) algorithm of Hirsch and Fye [

32]. The imaginary time axis was discretized, with

. Each QMC run consisted of 100,000 sweeps to ensure convergence of the impurity solver. The statDMFT self-consistency loop typically required 150 iterations to reach full convergence. To obtain the local density of states (LDOS), we performed an analytical continuation [

33,

34].

3. Results and Discussion

To characterize the Mott transition in two dimensions, we employ the Hubbard Hamiltonian (Equation (

1)) on a two-dimensional square lattice of

sites, where

. For the clean system (

), numerous studies have established the first-order nature of this transition at finite temperatures below a critical temperature

, exhibiting a distinct coexistence region and associated hysteresis [

29,

35]. Given that finite-size systems are expected to retain such hysteretic behavior, our statDMFT calculations must account for the convergence of both stable and metastable solutions. To accurately map the hysteretic loop, we utilize a sweep-based protocol. Calculations use initial interaction values

well outside the expected coexistence region, ensuring the system starts clearly within either the metallic or insulating phase. Once self-consistency is achieved for

, the resulting local Green’s functions

serve as the initial guess for the next interaction step

. This process is then iterated by increasing or decreasing

U, at increments of size

across the relevant range, effectively scanning the phase diagram from the metallic side toward the insulating side, and vice-versa. The objective is to trace both branches of the hysteretic loop. We identify two critical interaction values:

, observed when traversing from the insulating phase to the metallic phase, and

, obtained during the reverse sweep from the metallic phase to the insulating phase. These values delineate the spinodal points of the phase transition. The disparity between these forward and backward transition points traces a hysteretic loop. The interval between

and

defines the two-phase coexistence region, within which one of the solutions is always metastable [

30,

36].

The introduction of disorder significantly alters the nature of the Mott transition by inducing spatial inhomogeneities across the lattice. As shown in

Figure 1, individual sites within the square lattice exhibit their own distinct local density of states, leading to spatially varying metal–insulator transition characteristics. These site-dependent fluctuations not only influence the local transition points, but also affect the overall hysteretic behavior and the critical values

and

. For instance, the area enclosed by the hysteresis loop for site 58 is observed to be larger than that for site 2. This local variability has direct implications for device fabrication applications, where material inhomogeneities can severely impact critical temperatures or transport properties in different sections of a material. This is a crucial consideration in applications such as microstrip lines or high-temperature superconductors (HTS), where uniform performance and stability are paramount [

37,

38,

39]. To further illustrate the local transition dynamics, we track the evolution of the system’s spatial configuration as

U is varied. As the local electron–electron interaction

U increases during a sweep from the metallic to the insulating phase (

Figure 2), insulating "bubbles" nucleate and grow within the metallic background. Eventually, at the critical interaction strength

, the entire system undergoes a macroscopic transition to the insulating phase, visualized by a global change from a predominantly red (metallic) to a blue (insulating) color in

Figure 2. Conversely, when sweeping from the insulating to the metallic phase, metallic "bubbles" form and expand within the insulating medium until the system transitions into a fully metallic state (

Figure 3).

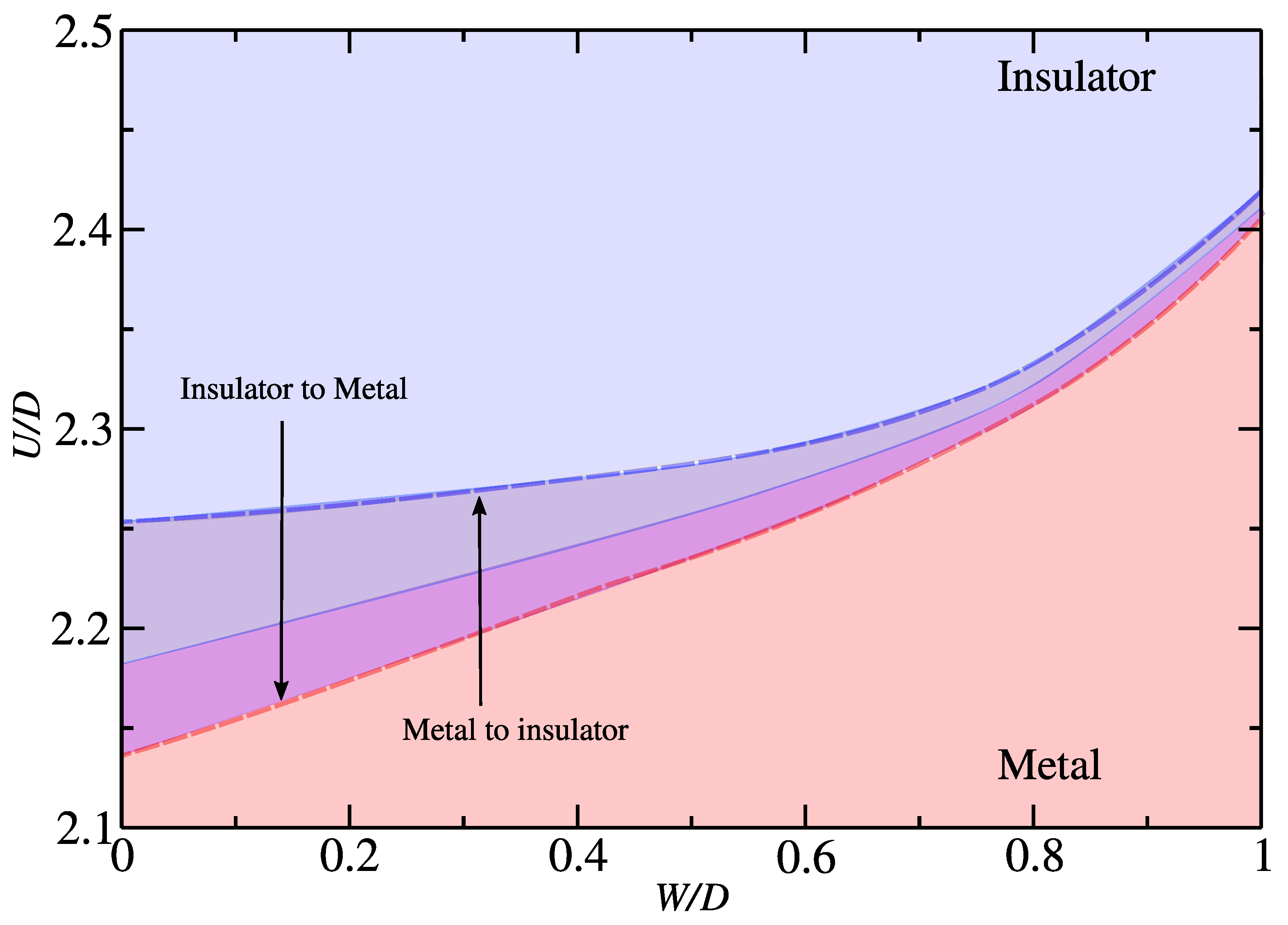

At zero disorder (), all sites in the system exhibit identical behavior, leading to a uniform metal–insulator transition across the lattice. This uniformity results in consistent critical values, for the insulator-to-metal transition and for the metal-to-insulator transition, for every site. However, even a small introduction of disorder () breaks this uniformity, causing each lattice site to exhibit a distinct local solution, where both the local potential U and the influence of neighboring sites become significant. As the disorder strength W increases, (insulator-to-metal) and (metal-to-insulator) shift toward higher on-site Coulomb repulsion (U), which is a defining characteristic of the competition between Mott and Anderson localization.

Disorder destabilizes the Mott insulating state by introducing site-to-site energy variations, which lead to the formation of localized in-gap states within the clean Mott gap. This “band tailing” [

40] effectively closes the gap prematurely, thereby requiring a stronger electron–electron interaction to re-establish the gapped state. This forces

toward higher

U [

41]. Concurrently, disorder acts as a scattering center for the coherent quasi-particles that define the metallic Fermi liquid phase. However, the electron–electron interaction (

U) itself can partially screen the random potential, protecting the metallic state from Anderson localization [

13] up to a higher disorder level. This competition means that the system maintains its metallic character, and transitions to the insulating state only at a significantly higher interaction value

[

42]. This trend is summarized quantitatively by the average critical values in

Table 1 as a function of increasing disorder

W.

Qualitatively,

Figure 4 illustrates the complex interplay between electron–electron interactions and disorder within the lattice, showing that increased disorder tends to shrink the hysteresis loop. The observed reduction in the width of the hysteresis region is a thermodynamic consequence of disorder, undermining the first-order nature of the Mott transition. The coexistence region, responsible for the hysteresis, relies on the stability of two distinct, uniform ground states—the correlated metal and the Mott insulator—separated by a finite energy barrier.

Increasing disorder introduces local inhomogeneity, promoting the formation of phase-separated metallic and insulating puddles rather than a uniform transition. The presence of these random nucleation sites effectively smears the transition by reducing the energy barrier separating the two phases, thereby shrinking the region where both phases are globally metastable. This phenomenon leads to the convergence of

and

toward a single critical endpoint (

) in the phase diagram, where the first-order transition line terminates and gives way to a continuous or crossover transition [

42,

43].

While the region of phase coexistence for each local site in the lattice shrinks—as disorder (W) increases—the critical interaction strength required to achieve a metallic state across the entire lattice, for a specific value of disorder, , remains below the lower critical point, , of the site. In contrast, the critical strength required to ensure a fully insulating state across the lattice, , is greater than the upper critical point, , of any local site of the lattice.

4. Conclusions

Our study systematically investigated the metal–insulator transition (MIT) in the two-dimensional Hubbard model within the framework of statistical dynamical mean-field theory (statDMFT), focusing on the intricate competition between electron–electron interactions and disorder. The transition’s nature is fundamentally determined by the balance of these opposing forces, making disorder a crucial factor for realistic understanding of inhomogeneous materials. As disorder strength increases, we observed a systematic shift of the critical interaction values, (insulator-to-metal) and (metal-to-insulator), toward higher values, with both and increasing monotonically with W. Concurrently, the width of the hysteretic region, characteristic of the first-order transition, is progressively reduced. Crucially, our site-resolved approach revealed that each lattice site exhibits unique hysteretic behavior and distinct local critical values for and . This spatial inhomogeneity, a direct consequence of local disorder, implies that different regions within a material can possess varying critical properties. For instance, in the context of material fabrication, such site-to-site variability can lead to a spatially non-uniform critical temperature, which is a critical concern for applications. In superconductors, for example, localized regions with a lower effective critical temperature could act as nucleation points for quenching, limiting overall device performance. These findings underscore the critical role of inhomogeneity in strongly correlated materials and highlight the necessity of theoretical frameworks like statDMFT, which account for local variations. Our work provides a foundational understanding for further explorations into the rich phenomenology of quantum materials and their potential technological applications, where material uniformity is paramount.