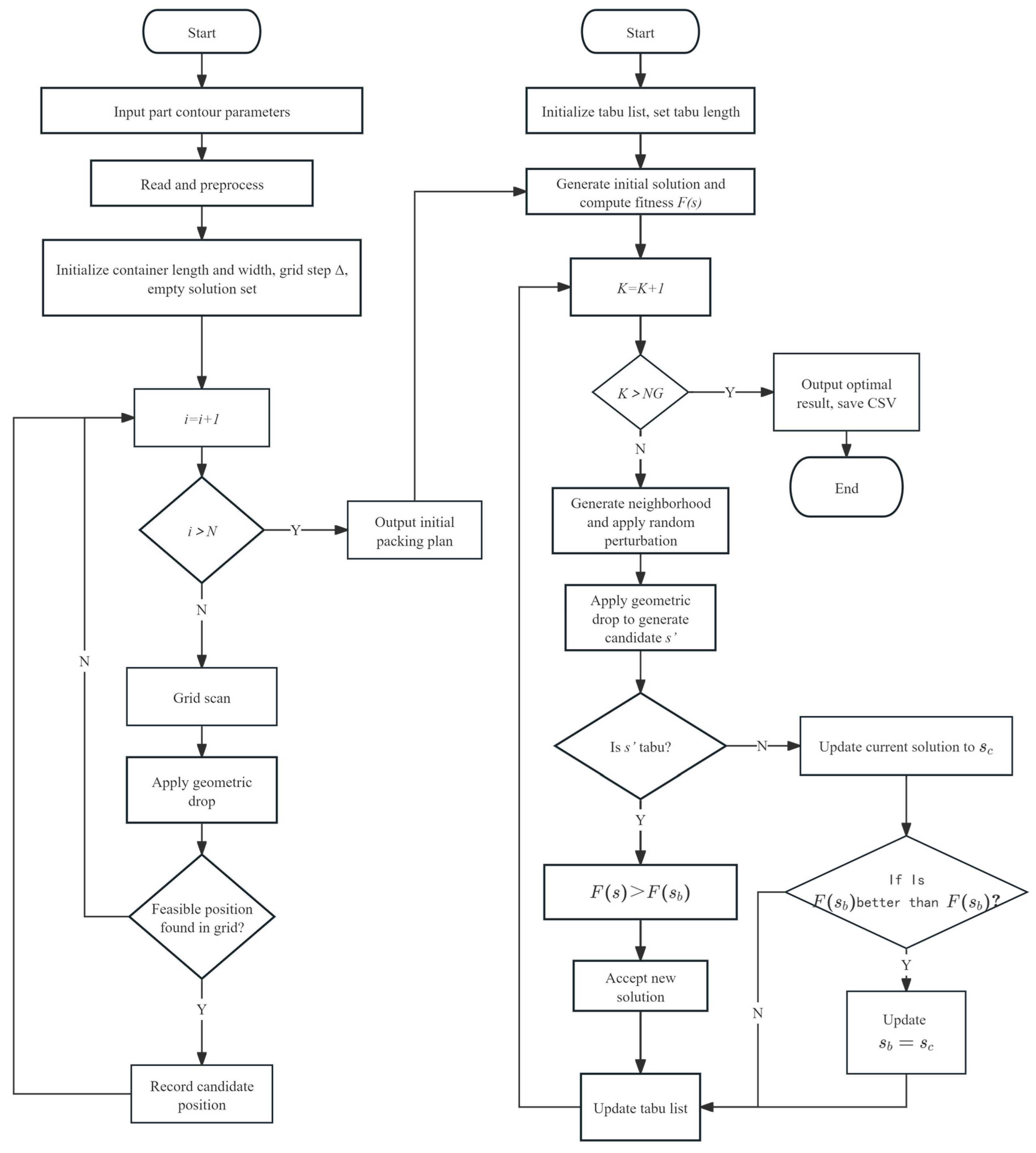

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed two-stage heuristic packing algorithm, this section presents experimental demonstrations and performance evaluations based on a representative case. The experiment first performs 2D layout optimization of irregular parts, then constructs the 3D packing model based on the optimal layer template, and finally compares the results with other algorithms to evaluate the advantages of the proposed method in terms of packing efficiency and computational performance.

6.1. Experimental Environment and Data Settings

The experiments were conducted on a personal computer equipped with an Intel Core i7-9750H processor, 8 GB of RAM, and running the Windows 11 operating system. The computational environment utilized Python 3.10 along with commonly used scientific computing libraries, including NumPy for numerical operations, Trimesh for 3D geometry processing, and Matplotlib 3.10.3 for visualization.

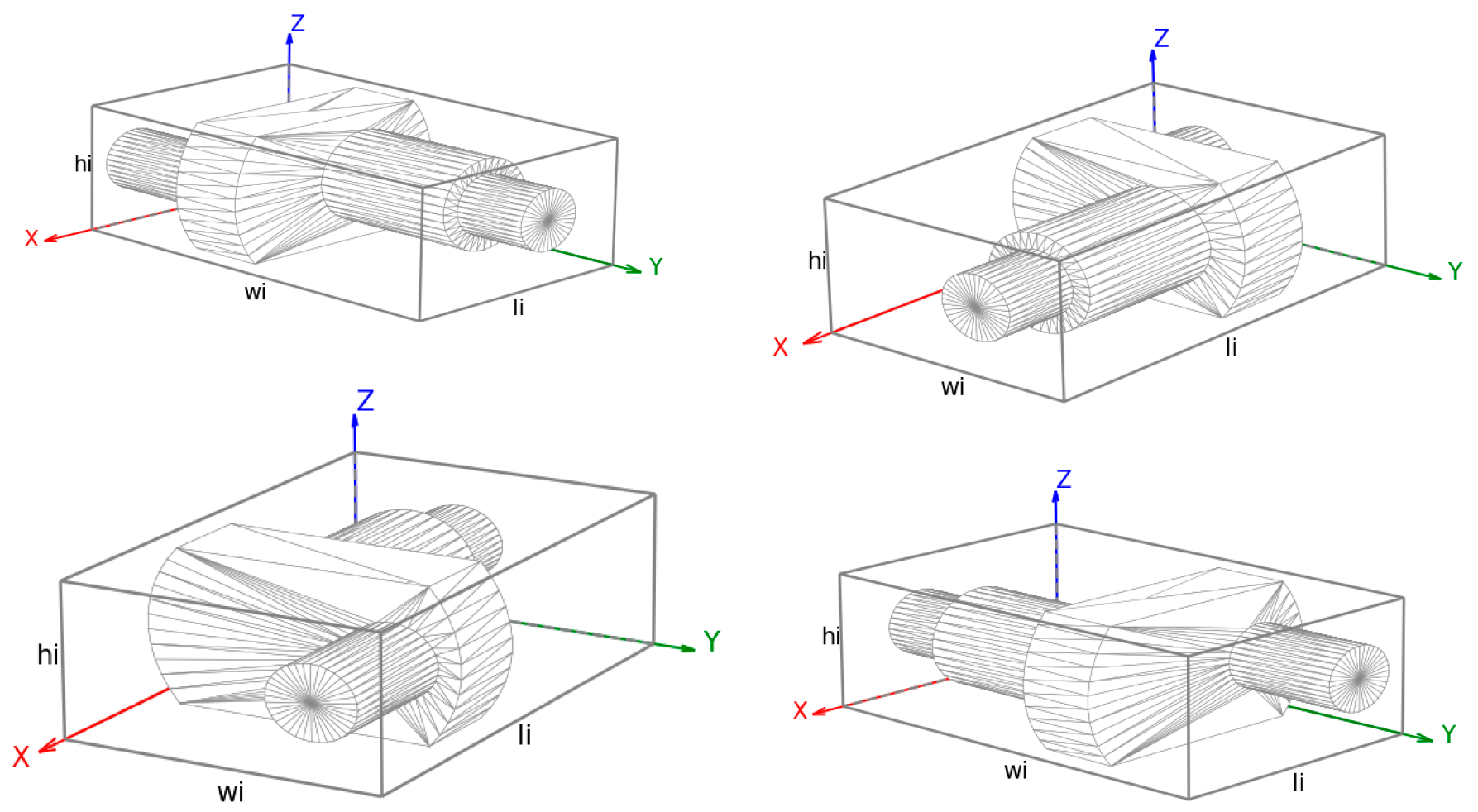

The experimental study focused on eccentric shafts, which exhibit irregular and non-symmetrical geometric features. The dataset comprised a total of 1000 identical components, and the packing container was a rectangular box. As a representative example, Box Type 1 had dimensions of 400 mm × 300 mm × 250 mm. This setup allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed packing algorithm’s performance under practical conditions involving large quantities of mechanically complex parts.

6.2. Results of the First-Stage 2D Layout

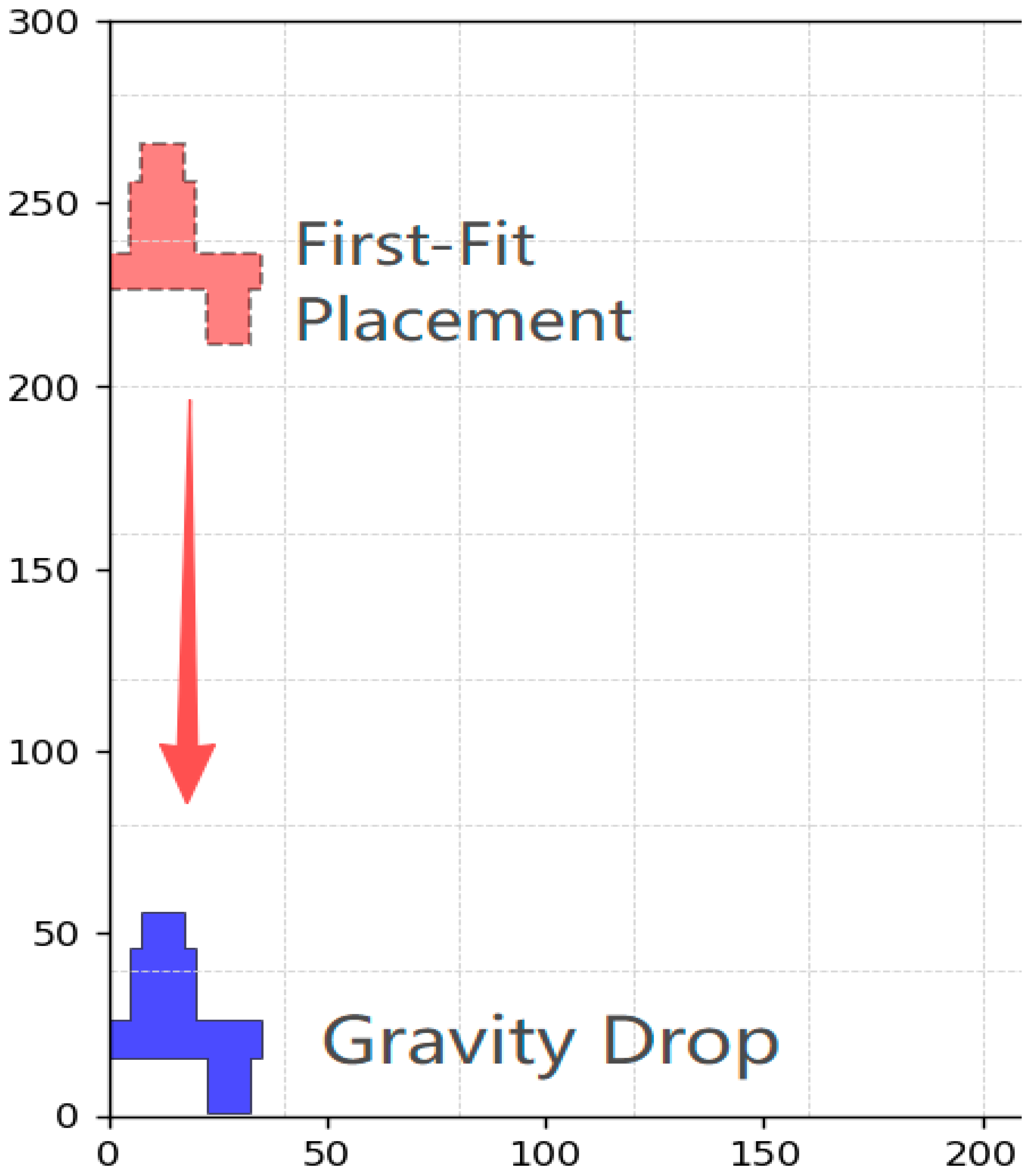

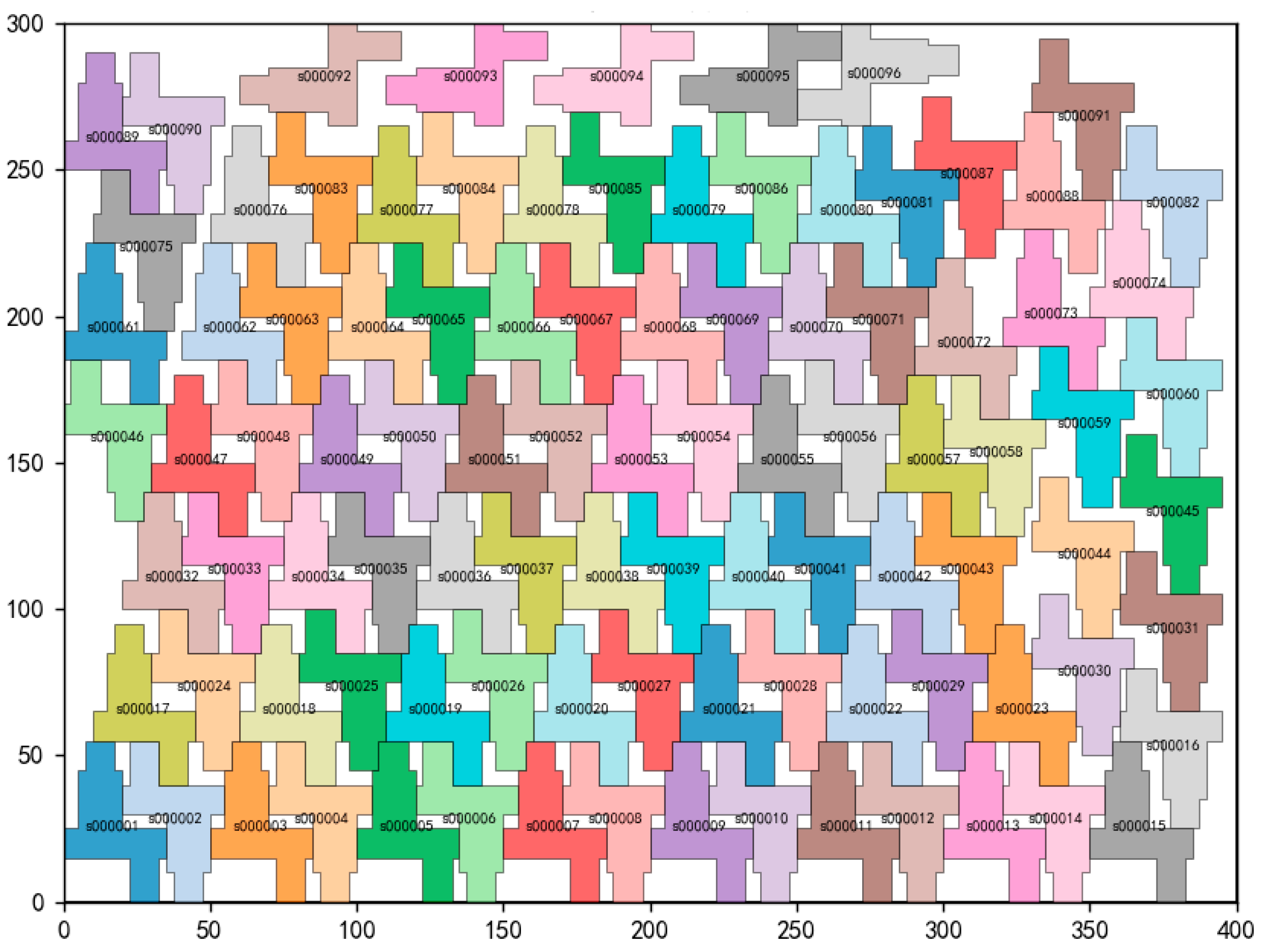

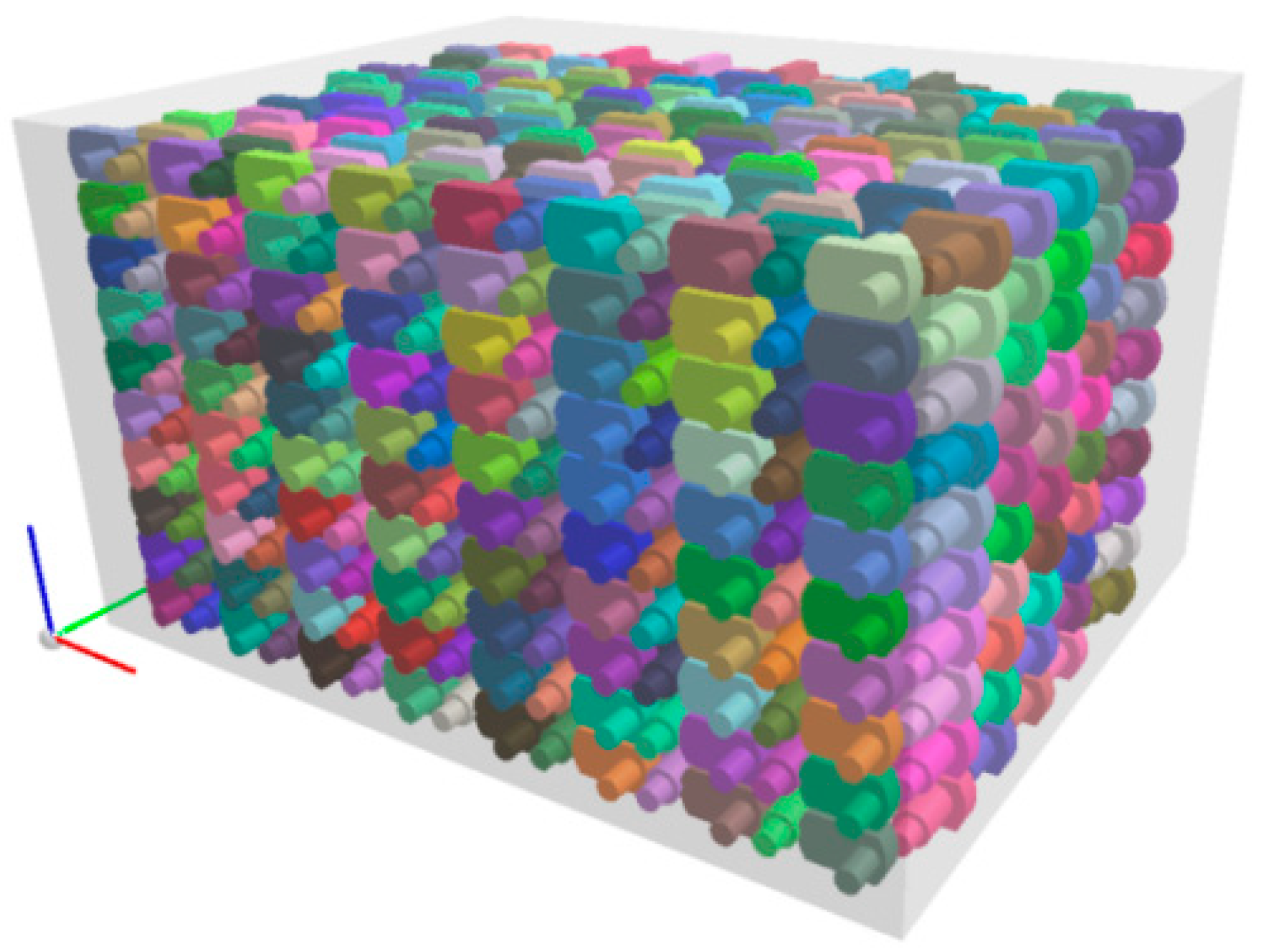

In the first stage of computation, the program generates a color-coded two-dimensional layout for each individual layer, providing a clear and intuitive representation of the initial packing arrangement. As illustrated in

Figure 5, each eccentric shaft is represented by a polygon corresponding to its projection onto the plane, with different colors used to distinguish individual parts. To facilitate identification and subsequent post-processing, the index of each part is labeled directly within the corresponding polygon, typically at or near its center. This placement ensures that the part can be easily distinguished without ambiguity, supporting tasks such as data extraction, verification, collision detection, and integration with automated packing systems. The visual representation allows for immediate assessment of layer compactness, orientation distribution, and unused spaces, and provides essential information for guiding the subsequent three-dimensional stacking process, enhancing the overall packing efficiency and reliability.

In addition to the visual layout, the program automatically generates a CSV file that records each part’s ID, placement coordinates, and rotation angle, facilitating automated reading or manual verification in practical applications.

Experimental results indicate that the combination of grid scanning and tabu search heuristic optimization achieves a high space utilization rate within each layer. The eccentric shafts are compactly arranged with minimal gaps, and the orientation distribution is well distinguished, which benefits subsequent packing and manipulation tasks. The overall packing scheme can be generated rapidly with a high degree of standardization.

The exported CSV data and visual layout provide a reliable reference for downstream automated sorting, packing, and verification operations, demonstrating the feasibility and practicality of the proposed heuristic algorithm in eccentric-shaft packing. The 2D area utilization rate of the optimized layer reaches 72%, indicating an efficient use of the available planar space.

To further assess the robustness of the proposed first-stage layout strategy with respect to initialization randomness, a multi-start experiment was conducted. The complete two-dimensional layout generation process, including grid-based initial placement and Tabu Search optimization, was independently executed five times using different randomized initial configurations.

All experimental runs consistently converged to the same final 2D area utilization rate of 72%, yielding a standard deviation of 0 across trials. This result indicates that the proposed neighborhood perturbation and gravity-like projection mechanisms exhibit strong robustness and are not sensitive to the initial placement configuration. The consistent convergence behavior suggests that the search process is not trapped in poor local minima, and that the effective solution space is dominated by a stable high-quality packing structure under the given geometric constraints.

6.3. Template-Layer Replication Results

In the second stage of the proposed method, a three-dimensional packing model is constructed based on the optimal two-dimensional layout obtained during the first stage, employing a template-layer replication strategy. Given that all eccentric shafts are identical in type, their geometric features remain consistent across layers, which allows for a uniform and regular stacking pattern. The algorithm selects the most efficient 2D layer layout from the first stage as the template and replicates it proportionally along the vertical direction, spanning the full height of the container. While true three-dimensional nesting could theoretically enhance inter-layer interlocking for certain irregular objects, the geometric characteristics of the eccentric shafts in this study limit the feasibility of vertical interlocking. Therefore, the template-layer replication strategy is expected to provide a near-optimal 3D packing solution for these components, and additional three-dimensional nesting does not offer significant improvement.

To further enhance the mechanical stability of the stacked components, a thin foam interlayer may be optionally introduced between adjacent layers, which serves to increase friction, absorb shocks, and prevent relative displacement during handling or transportation. Although the introduction of buffer layers slightly increases the overall height and reduces the volume available for packing, the effect on the total packing-utilization rate is minor, and the trade-off favors improved stability without significantly compromising efficiency.

During the replication process, the algorithm performs automatic verification for boundary violations and inter-component collisions in each layer, ensuring that the three-dimensional arrangement is both geometrically feasible and mechanically stable. This approach guarantees that each layer aligns precisely with the template, maintaining consistent positioning and orientation of the components throughout the box.

Figure 6 presents the final 3D packing configuration generated by the proposed algorithm. The experimental evaluation shows that, within a container measuring 400 mm × 300 mm × 250 mm, the algorithm successfully packs 920 individual eccentric shafts, achieving a total space utilization rate of 45.82%. These results underscore the algorithm’s capability to densely and efficiently arrange irregular, asymmetrical components while maintaining uniformity and stability across the stacked layers. The high packing density demonstrates the practical effectiveness of the template-layer replication approach, providing a robust and reliable solution for automated packing systems, particularly in industrial applications involving large quantities of mechanically complex parts. Moreover, the method’s systematic verification and stability measures ensure that the packed structure can withstand handling and transportation stresses without compromising the integrity of the components.

6.4. Dynamic Simulation Experiment

To further verify the stability of the three-dimensional packing structure under actual transportation and handling conditions, a three-dimensional dynamic simulation system was constructed based on PyBullet, using the previously generated 3D stacking structure from the 2D template replication. The dynamic stability of the eccentric shaft packing structure was analyzed under slight vibrations. Previous studies have demonstrated that physics-engine-based multi-body dynamic simulations can effectively evaluate the relative displacement of irregular parts under gravity and external disturbances [

21], and that frequency-domain collision optimization methods can significantly improve collision detection efficiency in large-scale packing scenarios [

22].

Following these methodological foundations, the present study adopts physics-based modeling for contact, collision, friction, and gravity response. Unlike approaches primarily focused on dynamic behavior analysis or collision-handling efficiency, the physics engine here is employed as a post-packing verification tool to assess the mechanical stability of the packing structure generated by the proposed algorithm. The PyBullet engine operates on principles similar to Box2D [

23] and NVIDIA PhysX SDK [

24] in collision detection, contact solving, and gravity response, enabling realistic simulation of collisions, friction, and stacking stability among multiple objects. This makes it particularly suitable for virtual verification of packing structure stability.

6.4.1. Initial Packing Verification and Simulation Setup

The experimental objects consisted of the three-dimensional packing solutions generated by the proposed packing algorithm, comprising a total of 920 eccentric shafts. The simulation container dimensions were set to 400 mm × 300 mm × 250 mm. Each part was assigned a mass of 1 kg, and the gravitational acceleration was set to 9.8 m/s2.

To simulate slight vibrations during logistics transport or handling, a periodic disturbance with an amplitude of 0.05 rad and a frequency of 1 Hz was applied to the container for a total simulation duration of 5 s. These vibration parameters represent mild and repetitive disturbances, such as vehicle body swaying or slight tilting of a heavy truck during steady driving, gentle turns, or lane changes.

The initial positions and orientations of all parts were imported from the CSV file generated by the packing algorithm. Due to the highly irregular and sharp geometry of the eccentric shafts, direct mesh-based collision detection may introduce numerical instability or excessive computational cost. Therefore, convex hull approximations of the parts were adopted for collision detection, while the original STL meshes were retained for visualization. To improve contact resolution and reduce numerical penetration, the number of solver iterations was set to 1500, and the simulation time step was set to 1/480 s.

It should be noted that the primary objective of the dynamic simulation is post-packing stability verification, rather than high-precision contact mechanics validation. Although small numerical penetrations may occur when using convex hull–based collision models, the simulation parameters were selected to ensure stable and conservative evaluation of relative displacements under external disturbances. Detailed validation of solver convergence and mesh-level collision accuracy is beyond the scope of the present study and will be addressed in future work.

The vibration model employed in this study is intentionally simplified. A single-frequency harmonic excitation was applied as a baseline disturbance model, which has been widely adopted in packing and stacking stability studies due to its controllability and repeatability. While real transportation environments may involve broadband vibrations, stochastic disturbances, and occasional impacts, such complex excitations are expected to amplify displacement responses rather than fundamentally alter the observed stability trends. Accordingly, the current model provides a conservative and interpretable assessment of structural stability. Extension to multi-frequency and stochastic disturbance models is considered an important direction for future research.

6.4.2. Simulation Results and Stability Analysis

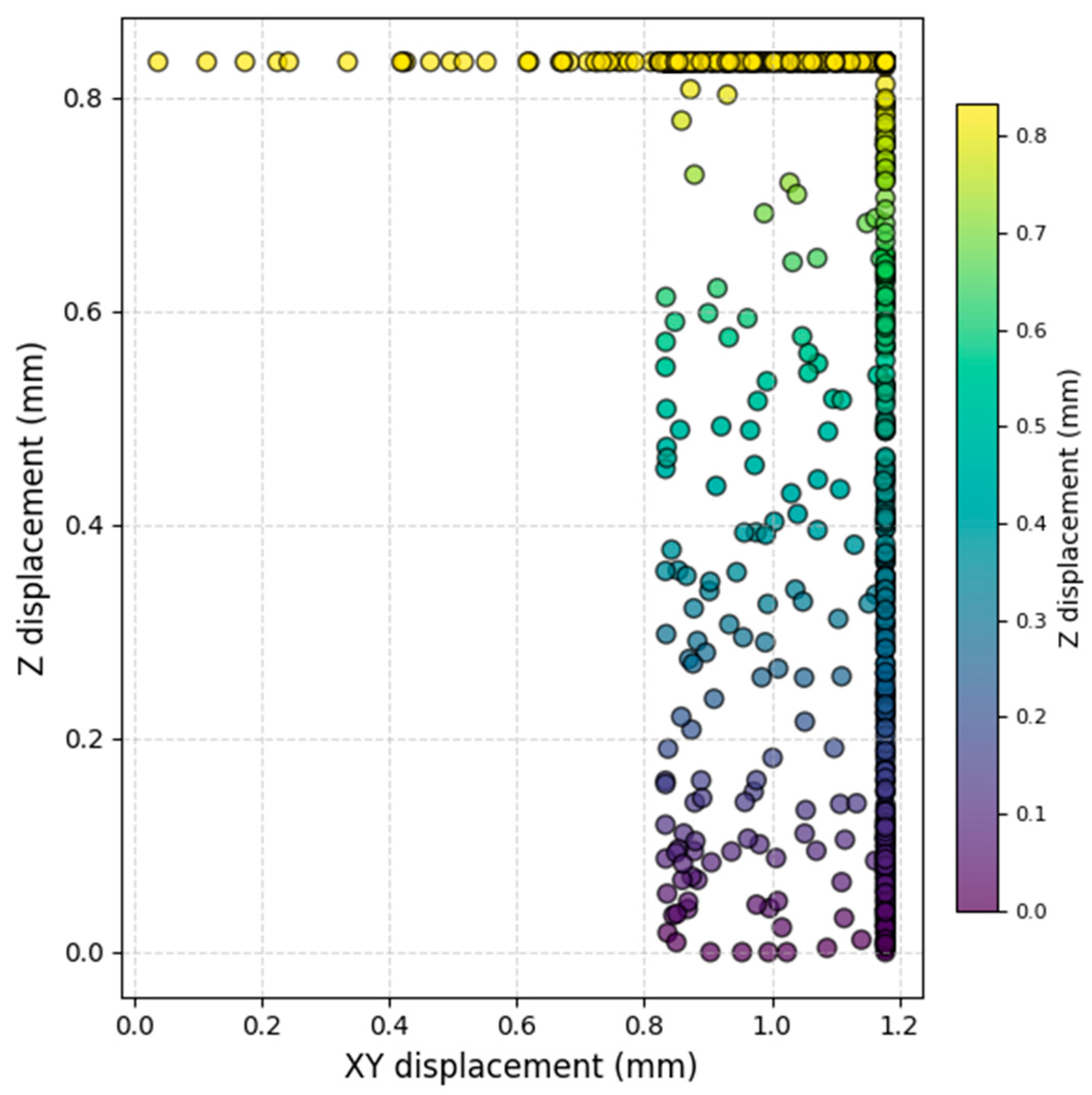

To quantify the stability of the packing structure, the spatial displacement of each part before and after the simulation was recorded, as shown in

Figure 7. The XY-plane displacement was used as an indicator of horizontal stability, while the Z-axis displacement was used to assess inter-layer risk. Specifically, a part was considered “loose” if its XY displacement exceeded 2.0 mm, and “cross-layer” if its Z displacement exceeded 50% of a single layer height. These metrics allow direct quantification of structural stability and effectively reflect potential risks such as micro-movements, sliding, tipping, or collapse.

The results show that 920 eccentric shafts were successfully packed into the 400 mm × 300 mm × 250 mm container, achieving an overall packing efficiency of 45.82%. During the simulation, most parts exhibited only minor displacements, with a maximum XY displacement not exceeding 2.0 mm. Only a few parts were classified as loose, and no cross-layer movements were observed. The entire packing structure remained stable under slight vibrations, without local collapse or significant sliding, demonstrating that the proposed packing algorithm produces 3D structures with good spatial nesting and mechanical stability, suitable for practical engineering applications in transport and handling scenarios.

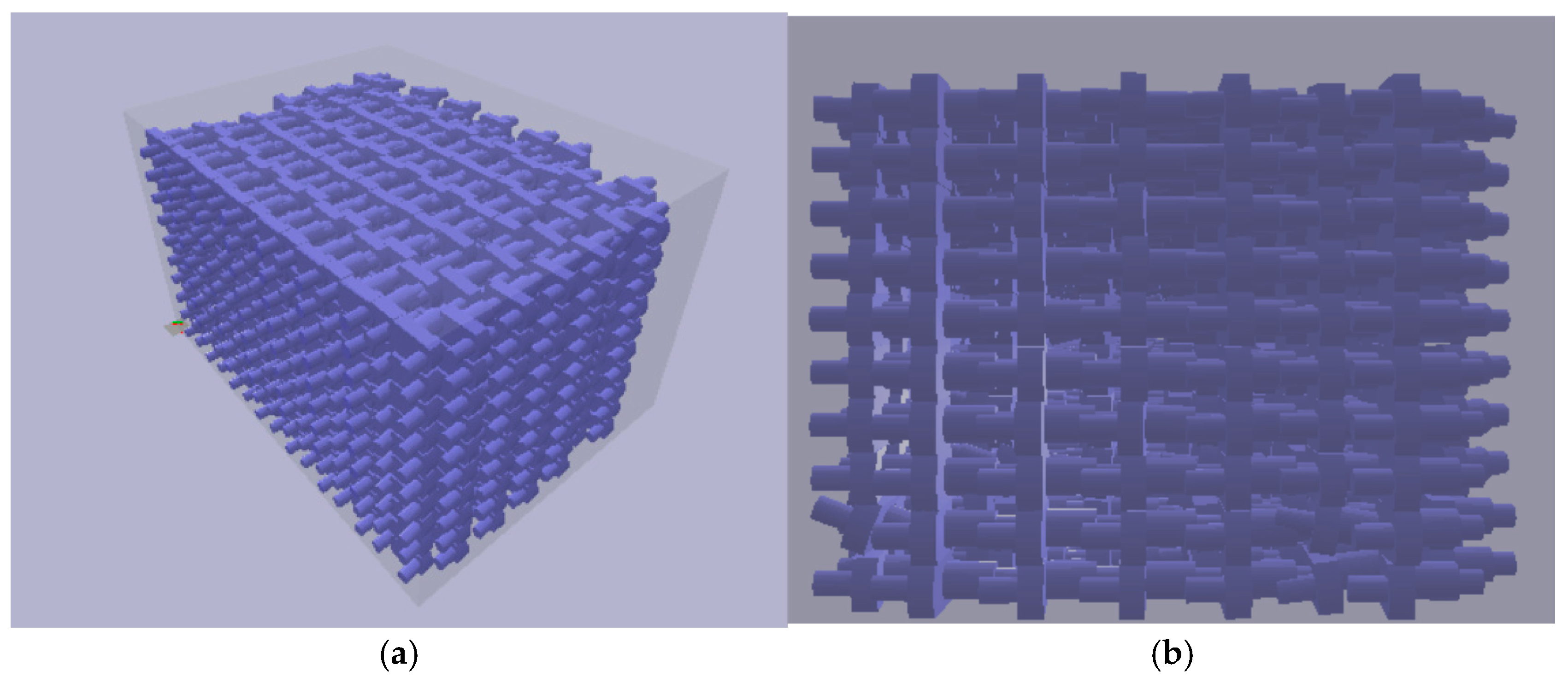

For more intuitive visualization of the simulation scene and stability performance,

Figure 8 shows snapshots of the simulated model from different viewpoints. The figures clearly demonstrate that the parts remain tightly nested under disturbance, with only minor displacements.

Importantly, these dynamic simulation results also address potential concerns regarding the use of a 2D layer template for constructing the 3D packing configuration. Although the 3D arrangement is generated from a planar 2D layout, the template-layer replication strategy ensures consistent alignment across all layers. Automatic checks for boundary violations and inter-component collisions are performed during replication, preventing vertical misalignment, unsupported placements, or inter-layer instability.

The PyBullet-based simulation confirms that, under gravitational and vibration disturbances, the packed components maintain their relative positions with minimal horizontal displacement (≤2 mm) and no cross-layer movement. These observations indicate that any cumulative projection modifications from the 2D-to-3D conversion do not compromise geometric feasibility or mechanical stability. Consequently, the results validate the robustness of the proposed packing method and its suitability for practical industrial application

6.4.3. Robustness to Manufacturing-Induced Geometric Variations

In practical manufacturing scenarios, small geometric deviations inevitably arise due to machining tolerances, surface roughness, and material deformation. Unlike exact geometric nesting methods that rely on tight boundary fitting, the proposed packing strategy is driven by feasibility-based placement rather than exact contour matching. The grid-scan heuristic, discrete orientation set, and first-fit placement mechanism inherently introduce geometric clearance, which reduces sensitivity to small local shape perturbations.

Moreover, the gravity-like drop strategy further enhances robustness by allowing components to settle into mechanically supported positions based on contact interactions, rather than relying on predefined geometric constraints. As a result, minor deviations in local geometry are compensated through contact redistribution during placement.

The dynamic simulation experiments conducted using PyBullet provide indirect yet effective validation of this robustness. In these simulations, collision detection is performed using convex hull approximations instead of exact mesh geometries, which introduces additional geometric abstraction comparable to manufacturing-induced uncertainties. Despite these approximations and the application of external vibrational disturbances, the packing structure exhibited minimal displacement and no cross-layer instability. This observation indicates that the proposed method is not highly sensitive to small geometric perturbations and can maintain stable packing configurations under realistic non-ideal conditions.

Although explicit geometric noise injection experiments are not included in the present study, the combined effects of feasibility-based placement, gravity-driven stabilization, and physics-based post-verification collectively demonstrate the algorithm’s resilience to moderate manufacturing-induced geometric variations. A more detailed stochastic geometry perturbation analysis is identified as an important direction for future work.

6.5. Comparative Experiments

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed method under different box conditions, four representative packing algorithms were selected as benchmark methods for comparison:

- –

BLF (Bottom-Left Fill): sequentially places parts in feasible gaps following the bottom-left priority rule, a widely used constructive heuristic in packing studies.

- –

LHL (Lowest Horizontal Line): places parts along the lowest horizontal line to minimize voids, commonly applied in layer-based packing.

- –

Best Fit: sorts and places parts according to the minimum residual space after placement, representing a residual-space optimization approach.

- –

Random: randomly selects feasible positions and orientations, serving as a baseline reference to highlight the advantages of structured heuristics.

The proposed algorithm is compared with these benchmark methods from three perspectives: space utilization rate, computation time, and number of packed parts. This selection ensures a well-rounded comparison across different packing strategies and provides a substantiated basis to assess the effectiveness of the newly developed method.

6.5.1. Experimental Design and Box Configurations

To verify the adaptability of the proposed algorithm to different box types, eccentric shafts were used as test objects in multiple simulated packing experiments based on actual industrial packaging scenarios. The box configurations are listed in

Table 2.

In the experiments, all boxes were loaded with the same type of irregular eccentric shafts to ensure consistency and comparability. The proposed heuristic packing algorithm was applied alongside four benchmark algorithms to systematically evaluate its performance. This comparative study aimed to assess the adaptability and effectiveness of the proposed method across various box dimensions and configurations. By analyzing the resulting packing layouts, space utilization, and placement efficiency, the experiments provide comprehensive insights into how the algorithm performs under different container conditions, thereby demonstrating its robustness, general applicability, and potential advantages over traditional packing strategies in practical industrial scenarios.

6.5.2. Results and Discussion

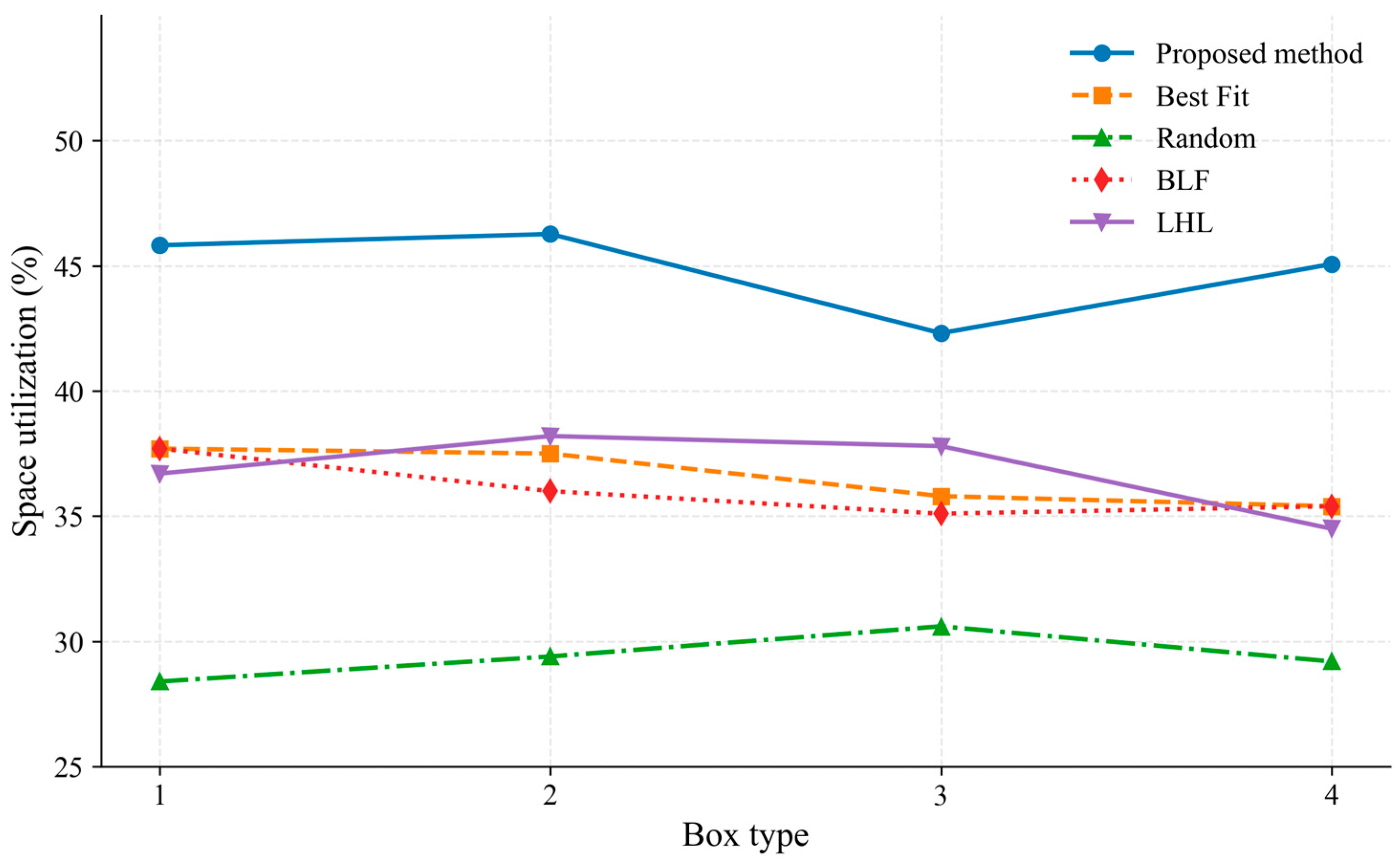

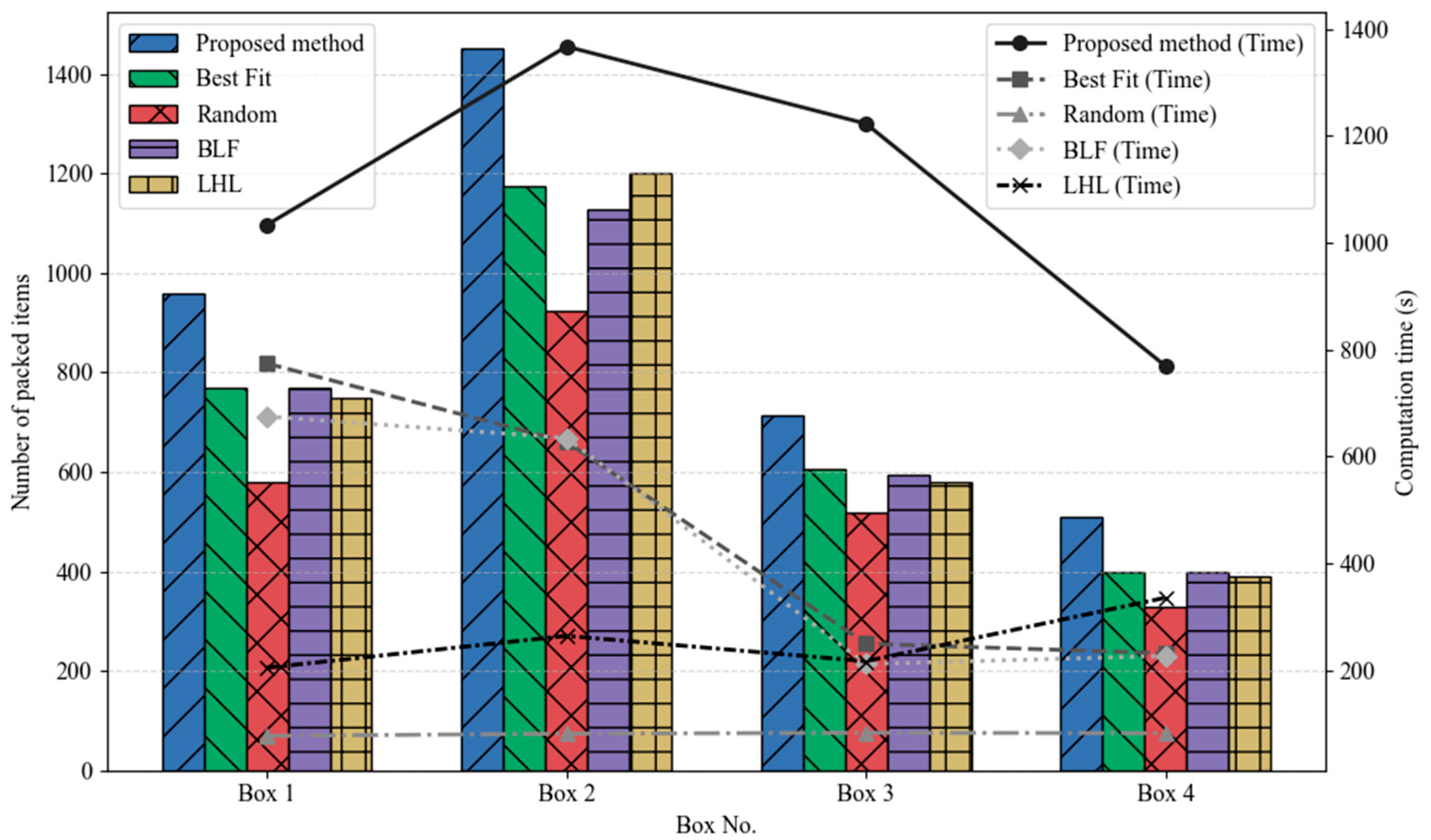

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present the comparative results in terms of space utilization and computation time across different box types.

As shown in the figures, the experimental results indicate that the proposed two-stage heuristic packing algorithm achieves higher space utilization and more compact layouts across all tested box types compared with conventional methods, including Bottom-Left Fill (BLF), Lowest Horizontal Line (LHL), Best Fit, and Random placement. Quantitative analysis shows that the average space utilization across the four box types reaches 44.9%, corresponding to improvements of approximately 8.8%, 8.3%, 8.1%, and 15.5% over the BLF, Best Fit, LHL, and Random algorithms, respectively. These results demonstrate the method’s capability to enhance packing efficiency, particularly for irregular eccentric parts, where even moderate improvements can lead to substantial volume savings in industrial scenarios.

Although the computational complexity of the proposed algorithm is higher and the runtime slightly exceeds that of traditional methods, the two-stage optimization process—incorporating gravity-like descent and tabu search—enables exploration of a larger solution space and the attainment of near-optimal packing configurations. The maximum observed runtime in the experiments was approximately 1366.8 s, which remains acceptable for practical industrial applications.

The algorithm ensures consistent layer geometry during three-dimensional stacking, resulting in more compact and orderly arrangements with reduced inter-layer gaps. Such structural consistency enhances the mechanical stability of packed items and provides clear geometric references for automated packing equipment, facilitating path planning and picking operations in automated feeding systems. Overall, the proposed algorithm demonstrates strong potential for deployment in real-world industrial packaging, offering both efficiency and reliability in handling irregular eccentric shafts or similar mechanical components.

6.5.3. Discussion on Benchmark Selection and Advanced Packing Methods

The comparative evaluation in this study focuses on representative constructive heuristic packing methods, including BLF, LHL, Best Fit, and Random placement. These algorithms are widely adopted in industrial packing systems due to their simplicity, determinism, and low computational overhead, making them practical baselines for large-scale automated packaging applications.

More advanced packing techniques, such as no-fit polygon (NFP)-based shape packing, continuous optimization methods, and hybrid metaheuristic frameworks, have been reported to achieve high packing densities for certain classes of irregular objects. However, these methods typically require complex geometric preprocessing, exact polygon decomposition, or intensive collision computations, which substantially increase implementation complexity and computational cost, especially for three-dimensional industrial-scale problems involving hundreds or thousands of parts.

In contrast, the proposed method is designed to balance packing quality, computational efficiency, and robustness under industrial constraints. By integrating grid-based candidate generation, gravity-like descent, and tabu search refinement, the algorithm achieves near-optimal packing performance while maintaining a predictable runtime and straightforward geometric handling. This design choice aligns with the practical requirements of automated packing systems, where robustness and scalability are often prioritized over marginal improvements in theoretical packing density.

Nevertheless, incorporating advanced shape-based or continuous optimization methods as additional benchmarks represents an important direction for future work. Such comparisons would provide deeper insights into the trade-offs between packing optimality, computational expense, and engineering feasibility for irregular mechanical components.