1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive respiratory disease characterized by persistent airway obstruction and respiratory symptoms and is one of the leading causes of death worldwide [

1,

2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), COPD is expected to be the third most common cause of death in the world by 2030, accounting for approximately 5% of all deaths, causing approximately 3.5 million deaths worldwide as of 2021 [

3,

4]. According to the Global Burden of Disease study, there are approximately 213.39 million COPD patients in 2021, and this trend is constantly increasing [

5,

6].

Early diagnosis of COPD and adequate assessment of severity are crucial for improving patient prognosis and disease management [

2,

7]. However, approximately 70–85% of COPD patients worldwide remain undiagnosed, and this problem is more acute in low- and middle-income countries [

8,

9]. Undiagnosed COPD patients are exposed to higher health risks compared to normal people, and experience acute exacerbations, pneumonia, and high mortality [

10,

11].

Currently, the standard method for diagnosing COPD is pulmonary function testing (spirometry), which is diagnosed according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria when the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) is less than 0.7 after bronchodilator administration [

2,

12]. The GOLD classification system distinguishes disease severity into four levels according to the percentage of predicted FEV1: mild (≥80%), moderate (50–79%), severe (30–49%), and very severe (<30%) [

13,

14]. However, these pulmonary function tests are difficult to perform in all medical settings due to limitations such as the availability of equipment, technical difficulties in performing the test, and cost [

15,

16].

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) technologies, have brought about revolutionary changes in the field of medical image analysis [

17,

18]. Chest computed tomography (CT) imaging is a powerful tool for visualizing structural changes in COPD, capturing pathological features such as emphysema, airway thickening, and vascular changes [

19,

20]. Deep learning models, especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have shown excellent performance in diagnosing COPD and classifying its severity by automatically extracting and learning features from CT images [

21,

22].

Several previous studies have utilized pre-trained CNN models such as ResNet, VGG, DenseNet, and Inception to significantly improve the accuracy of COPD diagnosis, and some studies have achieved classification accuracy of more than 90% [

23,

24,

25]. In addition, the introduction of Multiple Instance Learning (MIL) and Transfer Learning techniques has made it possible to achieve high performance even with limited medical data [

26,

27]. However, the heterogeneous nature of COPD and its accurate classification of different stages of severity remain a challenge [

28,

29].

Crucially, the radiographic diagnosis of COPD relies not on a single global feature, but on the synthesis of multiple, distinct localized signs such as hyperinflation, diaphragm flattening, and bronchial wall thickening. Standard CNNs, which tend to aggregate global context, often struggle to disentangle these heterogeneous local features effectively. This limitation highlights the need for an attention mechanism capable of explicitly separating and attending to these distinct anatomical components to improve diagnostic precision.

Therefore, this study addresses these limitations by proposing a unified multi-task deep learning framework utilizing chest X-rays (CXRs), which are more widely available than CTs. We introduce a novel architecture integrating a ConvNeXt-Large backbone with a Slot Attention decoder. By leveraging the object-centric nature of Slot Attention, our model is designed to disentangle the complex, overlapping radiographic signs of COPD into distinct feature slots, enabling more accurate concurrent performance of COPD severity classification (Non COPD, Mild COPD, and Severe COPD) and continuous FEV1/FVC ratio regression. We present a comprehensive evaluation against multiple baseline models, analyzing both quantitative performance and qualitative saliency maps to validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

3. Proposal Methods

In this study, we developed a multi-task deep learning framework designed to concurrently perform classification and regression analysis on CXR images. The proposed architecture integrates a high-capacity convolutional neural network backbone with a slot-based attention mechanism to extract and subsequently refine disease-relevant features from high-resolution medical images. The overall pipeline encompasses data pre-processing, model training utilizing specialized loss functions for each task, and subsequent validation procedures.

3.1. Overall Architecture

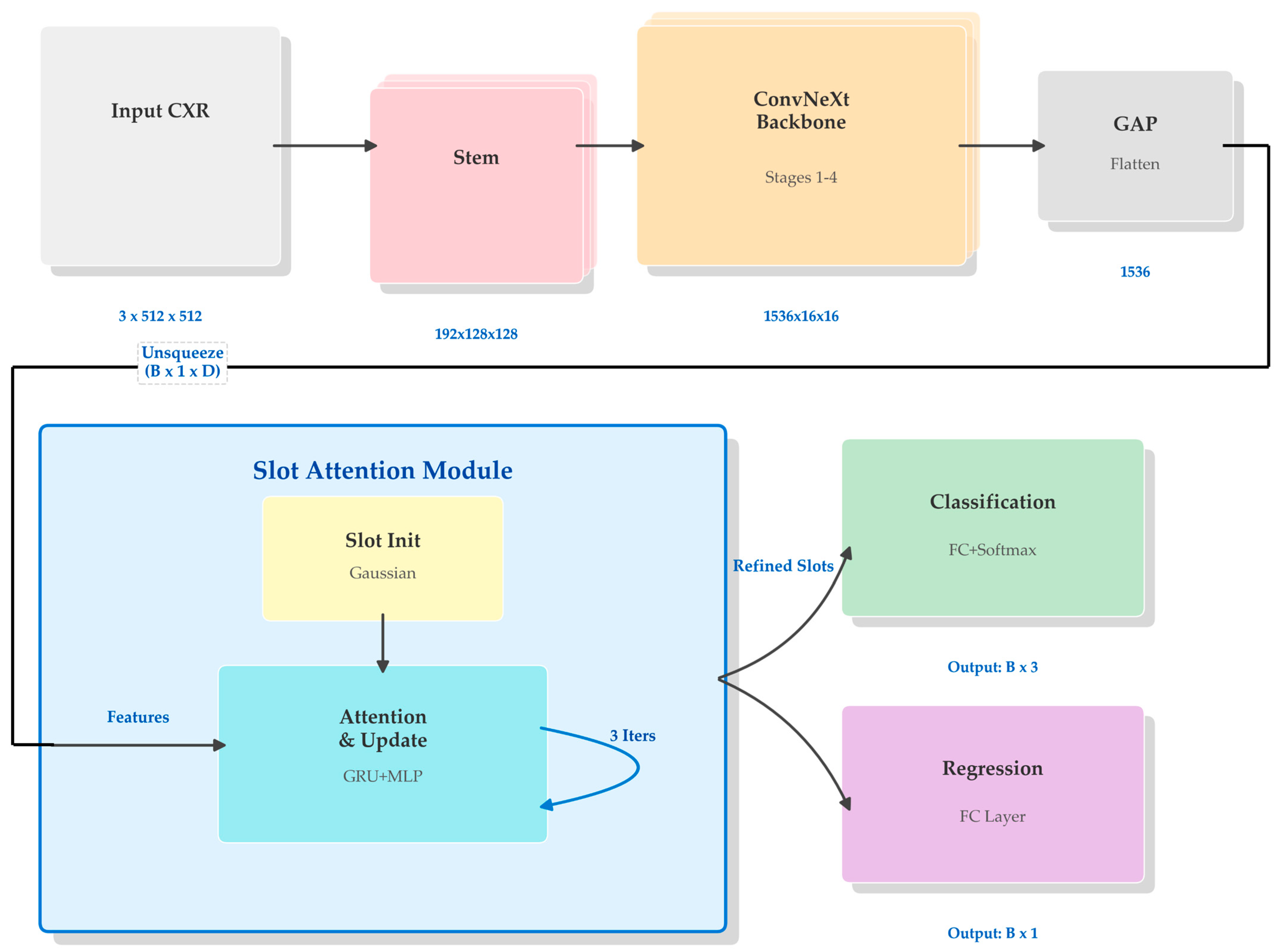

The complete architecture of the proposed model is schematically illustrated in

Figure 1. The model is configured to process input CXR images with predetermined dimensions of 512 pixels in both height and width, across three RGB color channels. Data flows through the network in batches, denoted by the batch size B, resulting in an input tensor shape represented as B × 3 × 512 × 512.

As shown in the global view of

Figure 1, the processing pipeline begins with a backbone network that encodes the raw high-dimensional image data into a compact feature representation. Unlike conventional architectures that directly utilize this backbone output for final predictions, our approach introduces an intermediate Slot Attention module. This module functions as a semantic bottleneck, decomposing the monolithic feature vector from the backbone into a set of distinct component vectors, referred to as slots. These refined slots are subsequently concatenated to form a unified rich representation, which is then fed into parallel output heads. Each head is specialized for its respective task: the classification head outputs probabilities for three diagnostic categories while the regression head simultaneously predicts the continuous FEV1/FVC ratio.

3.2. Feature Extraction Backbone

For the primary encoder, we employed the ConvNeXt-Large architecture [

57]. ConvNeXt modernizes the standard ResNet design by incorporating architectural choices inspired by Vision Transformers, such as larger convolutional kernel sizes (7 × 7), replacing ReLU with GELU activations, and utilizing fewer normalization layers. These adjustments allow the model to achieve competitive performance and scalable capacity while maintaining the inductive biases of convolutional networks, which remain advantageous for visual data processing.

The detailed structure of the backbone utilized in our framework is depicted in

Figure 2. The network consists of a stem layer followed by four progressive stages. The input image of shape B × 3 × 512 × 512 is first processed by the stem layer, which applies a 4 × 4 convolution with a stride of 4, effectively downsampling the spatial resolution to 128 × 128 while expanding the channel depth to 192. The subsequent four stages are composed of varying numbers of ConvNeXt blocks—specifically 3, 3, 27, and 3 blocks, respectively, for the ‘Large’ variant. Between these stages, downsampling layers further reduce spatial dimensions by a factor of 2 while doubling the channel capacity. Upon completing Stage 4, the resulting feature maps have dimensions of B × 1536 × 16 × 16. A global average pooling operation is then applied to collapse the spatial dimensions entirely, effectively summarizing the image content into a single feature vector of 1536 dimensions for each sample in the batch. A final flattening step ensures the output is a two-dimensional tensor with shape B × 1536, ready for the subsequent attention-based refinement.

3.3. Slot Attention Module

To enable more granular feature processing and disentanglement of semantic concepts, we incorporated a Slot Attention module [

58] as a trainable bottleneck. The internal mechanism of this module is detailed in

Figure 3. The module interfaces with the aggregated features from the backbone and distributes the contained information into a fixed number of five distinct slots (K = 5).

The process initiates by expanding the backbone’s output vector B × 1536 to B × 1 × 1536 to introduce a sequence dimension (N = 1), allowing it to function as visual keys and values within the attention mechanism. Simultaneously, five slot vectors, each maintaining the dimension D = 1536, are initialized using learnable parameters derived from a Gaussian distribution with trained mean and variance. These slots serve as queries that iteratively compete for information from the input feature vector.

As illustrated in the iterative loop of

Figure 3, this refinement occurs over three recurrent update steps. In each iteration, a dot-product attention mechanism calculates similarity scores between the current slot states (queries) and the input features (keys). These scores are normalized via a softmax function across the distinct slots, ensuring a competitive allocation of information. The weighted sum of input values is then used to update the slots via a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) [

59], followed by a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) with residual connections. Through this iterative process, the initially random slots progressively diverge and specialize to capture different latent aspects of the input image representation.

3.4. Multi-Task Output Heads

The final stage of the network diverges into separate pathways to handle the disparate objectives of classification and regression simultaneously. The five refined slot vectors from the attention module, each with a dimensionality of 1536, are first flattened and concatenated into a single unified representation vector with a total dimensionality of 7680 (5 × 1536).

This combined vector serves as the common input to two distinct linear layers functioning as task-specific heads. The classification head projects this 7680-dimensional vector down to three output nodes (B × 3). These nodes correspond to the un-normalized logits for the three target classes: Non COPD, Mild COPD, and Severe COPD. During inference, a Softmax function is applied to these logits to yield the final predicted probabilities for each severity level. In parallel, the regression head maps the same feature vector to a single scalar output node (B × 1), which represents the predicted continuous value of the FEV1/FVC ratio, a critical spirometric indicator of airflow limitation. By sharing the entire feature extraction and slot refinement pipeline up to these final layers, the model is encouraged to learn generalized representations that are robust enough to support both discrete categorization and continuous variable prediction tasks without needing separate backbone networks.

4. Experimental Environment

The proposed model was implemented using the PyTorch framework version 1.12 (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) and the Python programming language version 3.8.13 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA). All model training and evaluation processes were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU (NVIDIA Corp., Santa Clara, CA, USA).

4.1. Dataset

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cheonan Soonchunhyang Hospital (SCH; SCHCA 14 June 2025, approved on 4 July 2025). The dataset consists of de-identified CXR images in PNG format. To ensure consistency in anatomical presentation, only standard Anteroposterior (AP) and Posteroanterior (PA) projection views were included in the study cohort.

Ground truth labels for the classification task were established based on spirometric assessment following the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines [

2]. To avoid confusion with existing guidelines, we explicitly defined the diagnostic criteria for our three-class stratification system.

The Non COPD group included subjects with normal pulmonary function, defined as a post-bronchodilator ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) of 0.70 or higher.

The Mild COPD category corresponded to GOLD Stage 1 (Mild) and GOLD Stage 2 (Moderate). Patients in this group exhibited airflow limitations characterized by an FEV1/FVC ratio below 0.70 and an FEV1 of 50% or more of the predicted value.

The Severe COPD category merged patients from GOLD Stage 3 (Severe) and GOLD Stage 4 (Very Severe). This group represented advanced disease states, defined by severe airflow limitation with an FEV1/FVC ratio below 0.70 and an FEV1 of less than 50% of the predicted value [

60].

This stratification strategy was adopted to balance clinical relevance with model training stability, effectively grouping patients requiring similar levels of medical intervention.

To minimize class imbalance inherent in raw clinical data, the dataset collection followed a prospective protocol established prior to data extraction. The inclusion criteria were designed to acquire a targeted number of high-quality cases for each severity class, aiming for a balanced distribution (approximately 1599 Normal, 1200 Mild, and 1200 Severe cases) suitable for robust model training. This curated collection strategy ensures that the dataset reflects a controlled distribution for experimental validation rather than a random sample of hospital admissions.

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in

Table 1. The dataset included a total of 5000 subjects. Statistical analysis (One-way ANOVA for age and FEV1/FVC; Chi-square test for sex) revealed significant differences in age and gender distribution among the three groups (

p < 0.001). This reflects the natural prevalence of COPD, which is strongly associated with older age and male sex in the Korean population.

The study cohort was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets. To ensure rigorous evaluation and prevent data leakage, this split was performed strictly at the patient level. Consequently, images from the same subject were assigned exclusively to one subset, ensuring that no patient appeared in multiple splits. The detailed distribution of image samples across these three classes for each dataset split is presented in

Table 2.

For the regression task, the Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 s to FEV1/FVC was utilized as the target variable. This ratio is the primary spirometric index used for diagnosing obstructive lung diseases, representing the fraction of vital capacity that can be expired in the first second of a forced exhalation [

61].

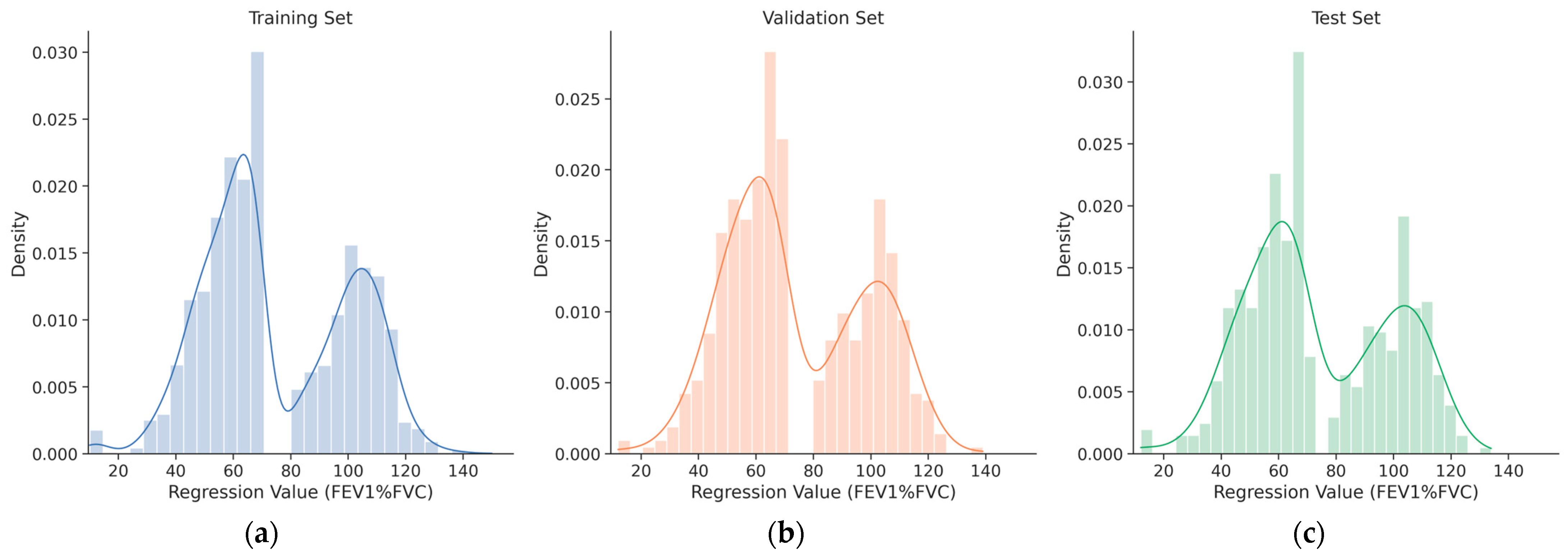

The distribution of FEV1/FVC ratios across the training, validation, and test splits is illustrated in

Figure 4. To facilitate direct comparison of data distribution among splits, histograms are overlaid with distinct colors. A single extreme outlier with a recorded value of 1114 was identified in the training set; this data point was determined to be physiologically impossible and was permanently removed from the dataset to ensure data integrity and training stability. Descriptive statistics for the FEV1/FVC ratio, calculated from the cleaned dataset for each individual split, are summarized in

Table 3.

4.2. Data Preprocsssing

Input CXR images were preprocessed to align with the initialization requirements of the backbone network pre-trained on ImageNet. Specifically, pixel intensity values were normalized using the standard ImageNet RGB mean (0.485, 0.456, 0.406) and standard deviation (0.229, 0.224, 0.225) after rescaling to the [0, 1] range. While medical images typically exhibit different intensity distributions compared to natural images, we maintained the ImageNet normalization statistics to preserve the feature distribution expected by the pre-trained weights, thereby ensuring stable convergence during transfer learning. All images were resized to a uniform spatial resolution of 512 × 512 pixels via bicubic interpolation. To improve model generalization and robustness against variations in image quality, we employed RandAugment [

62], an automated data augmentation strategy. For this study, the RandAugment parameters were set to N = 2 (number of augmentations to apply sequentially) and M = 28 (magnitude of the augmentation operations).

Target variables were processed according to their respective tasks. Diagnostic class labels for classification were converted using one-hot encoding. The continuous FEV1/FVC ratio labels for regression underwent standardization (Z-score normalization) utilizing the global mean and standard deviation derived from the training dataset. This step ensured that the regression targets had a comparable scale to the classification outputs, preventing either task from dominating the joint gradient descent process.

4.3. Experimental Setup and Metric

The model was trained for a total of 250 epochs with a batch size of 32. Network parameters were optimized using the AdamW optimizer [

63], which decouples weight decay from gradient updates. The initial learning rate was set to 1 × 10

−4 with a weight decay coefficient of 1 × 10

−4. To stabilize the early training phase, a flat warmup strategy was applied for the first 5 epochs, followed by a Cosine Annealing learning rate scheduler [

64] for the remainder of the training process. The multi-task objective function combined distinct losses for each head. For the multi-class classification task, Categorical Cross-Entropy loss was utilized with label smoothing [

65] of 0.1 to mitigate overconfidence in predictions. For the regression task, the Log-Cosh loss function was employed, as it approximates Mean Squared Error for small errors and Mean Absolute Error for larger errors, making it robust to outliers. To ensure a balanced optimization process where neither task dominates the gradient updates, we adopted a fixed weighting scheme, assigning an equal weight of 1.0 to both the classification and regression losses. The overall hyperparameters are summarized in

Table 4.

Performance evaluation was stratified into classification and regression components to align with the multi-task learning objective. For the multi-class classification task, performance was assessed using macro-averaged metrics derived from one-vs-all confusion matrices for each diagnostic category. This approach ensures equal weight is given to all three classes regardless of their prevalence in the test set. The primary classification metrics include Sensitivity, Specificity, and Accuracy. These are calculated as the arithmetic mean of the respective per-class metrics, providing a balanced view of model performance across all severity levels. The mathematical definitions of these metrics are presented in Equations (1)–(3):

where N denotes the number of diagnostic classes (here N = 3), and

,

,

, and

represent the number of True Positives, True Negatives, False Positives, and False Negatives for class i, respectively.

For the regression task, the predictive accuracy of the continuous FEV1/FVC ratio was evaluated using Mean Absolute Error, Mean Squared Error, and the Coefficient of Determination. Prior to calculating these metrics, the raw output values of the model were inversely standardized using the global mean of 74.83 and standard deviation of 29.18 from the original dataset. This step restores the predicted values to their original physiological scale for clinically meaningful validation. Mean Absolute Error measures the average magnitude of errors in a set of predictions without considering their direction. Mean Squared Error measures the average of the squares of the errors, giving more weight to larger differences. The Coefficient of Determination provides an indication of goodness-of-fit, representing the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variable. These metrics are formally defined in Equations (4)–(6):

where n is the total number of test samples,

is the actual ground truth FEV1/FVC value for sample j, and

is the corresponding predicted value after inverse standardization.

This dual-evaluation framework ensures a balanced optimization of the multi-task objective, verifying that the model achieves reliable performance across both qualitative disease staging and quantitative pulmonary function estimation.

6. Discussion

This study proposed a unified deep learning framework integrating a ConvNeXt backbone with Slot Attention to simultaneously classify COPD severity and estimate the FEV1/FVC ratio from chest radiographs. Our findings demonstrate that this multi-task approach achieves high diagnostic accuracy and precise functional quantification, outperforming standard CNN and Vision Transformer baselines.

6.1. Clinical Implications and Diagnostic Performance

The primary clinical contribution of this work is the demonstration that deep learning can effectively extract spirometric surrogates from standard CXR images. The model achieved a Test

of 0.7591 for FEV1/FVC estimation, a figure that aligns with recent studies reporting strong correlations between radiographic features and pulmonary function [

21,

42]. While structural changes on X-rays do not always linearly map to functional impairment, our results suggest that deep convolutional networks can identify complex, non-linear patterns—such as subtle parenchymal texture variations and micro-architectural distortions—that are often imperceptible to human observers but highly indicative of airflow limitation.

In resource-limited settings where spirometry is unavailable or contra-indicated, this automated tool could serve as a valuable screening mechanism. By providing an immediate, low-cost assessment of COPD severity, it could help prioritize high-risk patients for confirmatory pulmonary function testing, thereby optimizing healthcare resource allocation.

6.2. Role of Slot Attention in Feature Disentanglement

A key methodological innovation of this study is the application of Slot Attention to medical image analysis. COPD diagnosis relies on the synthesis of various localized radiographic signs, such as hyperinflation, diaphragm flattening, and bronchial wall thickening. Standard CNNs often struggle to disentangle these heterogeneous features from the global context.

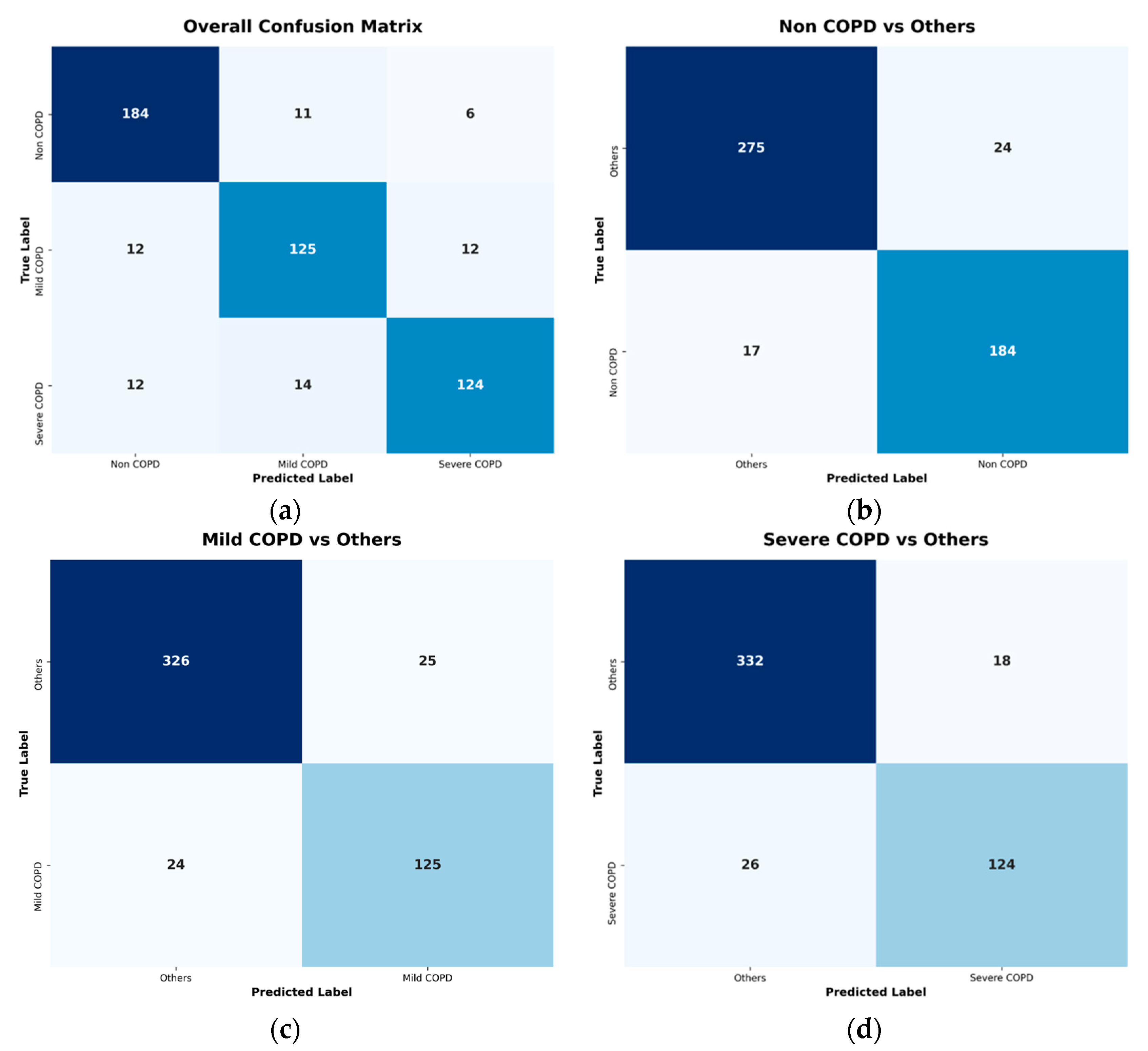

Our ablation study (

Table 7) and qualitative analysis (

Figure 6) provide empirical evidence that the Slot Attention mechanism addresses this limitation. The 5-slot configuration yielded the highest performance, suggesting it provides the optimal capacity to separate distinct disease-relevant concepts. Visually, the slot-based model produced more constrained and localized attention maps compared to the diffuse activation seen in baseline models. This indicates that the slots effectively “compete” for different anatomical regions, allowing the model to aggregate specific local evidence for a more robust global prediction.

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations. First, our experiments relied on data collected from a single institution, utilizing a specific set of scanner types and imaging protocols. This creates a potential risk of the model overfitting to local acquisition parameters and the specific demographic characteristics of the patient population at our center. Consequently, the generalizability of our proposed model to external datasets acquired from different institutions or scanner manufacturers has not yet been fully verified. Future studies should aim to validate the model using large-scale, multi-center cohorts to ensure robustness across diverse clinical environments and imaging conditions.

Second, the input resolution was standardized to 512 × 512 pixels due to computational constraints. While sufficient for capturing major structural changes, higher resolutions might be necessary to detect finer details of mild COPD, such as early vascular pruning. Future research should explore high-resolution training strategies or multi-scale architecture.

Third, our “Severe” class merges GOLD stages 3 and 4. While this simplification is clinically practical for identifying patients requiring urgent intervention, a more granular classification aligning strictly with all four GOLD stages would be beneficial for precise disease staging.

Finally, as shown in

Table 2, significant demographic differences were observed between classes, with the Severe COPD group being older and predominantly male compared to the Non COPD group. This raises the concern that the model might rely on demographic shortcuts (e.g., predicting age or bone density) rather than pathological features. However, our qualitative analysis using saliency maps (

Figure 6) demonstrates that the model’s attention is consistently focused on lung parenchymal structures and airway markers rather than irrelevant features like bone structure or soft tissue. This suggests that while demographic biases exist in the dataset, the proposed Slot Attention mechanism successfully drives the model to learn disease-specific radiographic patterns. Future work could explicitly integrate tabular data (age, sex, smoking history) into the model to further enhance predictive accuracy and mitigate potential confounding factors.

In conclusion, this study validates the potential of Slot Attention-enhanced deep learning for comprehensive COPD assessment from chest X-rays, offering a promising path toward accessible and interpretable AI-aided diagnosis.

7. Conclusions

This study presented a unified deep learning framework designed for the concurrent multi-task analysis of COPD from standard chest radiographs. By integrating a high-capacity ConvNeXt-Large backbone with a Slot Attention mechanism, the proposed architecture addressed the challenge of simultaneously learning discriminative features for discrete severity classification and continuous functional quantification.

Empirical evaluations on a clinical dataset demonstrated that the proposed model consistently outperformed established CNN baselines (ResNet, DenseNet, EfficientNet families) and Vision Transformer (ViT-L/16) across both tasks. The ablation study specifically highlighted the efficacy of the Slot Attention decoder in refining standard backbone features for multi-task learning. The 5-slot configuration proved optimal, achieving the highest test set performance with an Accuracy of 0.9253 for three-class severity stratification and an of 0.7897 for FEV1/FVC ratio estimation.

Furthermore, qualitative analysis using saliency maps suggested that the slot-based approach contributes to attention patterns that are more constrained to clinically relevant pulmonary structures, compared to baseline models. These findings suggest that incorporating explicit feature disentanglement mechanisms like Slot Attention can effectively enhance both the predictive performance and interpretability of deep learning models in complex medical imaging tasks. Future work may involve validating this approach on larger, multi-center cohorts to further confirm its generalizability in diverse clinical environments.