1. Introduction

Steel materials are traditionally believed to exhibit a fatigue limit at around

cycles, beyond which any cyclic plastic deformation can be considered to be negligible, and an infinite fatigue life expected. In recent years, however, it has been observed that this traditional value of the fatigue limit is inaccurate, and that fatigue failure can still occur even after billions of cycles, in what is known as the very high cycle fatigue (VHCF) regime [

1].

Acquiring reliable test data in this VHCF regime using conventional fatigue testing methods, which operate at frequencies of 10–100 Hz, is both time-consuming and expensive, however, thereby necessitating the use of accelerated testing methods to efficiently produce VHCF data. For this purpose, Ultrasonic Fatigue Testing (UFT) is typically employed. UFT makes use of a piezoelectric actuator to produce a controlled vibration at high frequencies, which is then amplified using an acoustic horn and used to excite the longitudinal resonant frequency of a test specimen [

2]. This allows a cyclic load to be imparted in a specimen at a frequency of 20 kHz, therefore enabling fatigue tests to be carried out up to 1000 times faster than using conventional fatigue testing (CFT) methods.

However, the use of such high test frequencies introduces several challenges. The increased loading rate and shortened test duration of UFT can significantly affect the fatigue response [

3], in a phenomenon referred to as the frequency effect. This effect is particularly pronounced for heavily ferritic steels, for which the fatigue lives obtained through UFT are typically much longer than those observed at conventional frequencies. For example, Klusák et al. [

4] found that the fatigue life at an equivalent stress amplitude was extended by two decades when tested at ultrasonic frequencies, while Bach et al. [

5] observed an increase in the fatigue limit of 58% for a C15E steel under UFT. Similar observations are reported for a variety of high ferrite-content steels throughout the literature [

6,

7,

8,

9].

This difference in fatigue behaviour is typically attributed to the Seeger Effect within the body-centred-cubic (BCC)

-ferrite regions of the steel [

10]. As described by Mughrabi et al. [

10], slip mechanisms in BCC materials are inherently temperature sensitive, and the transitional temperature is a function of strain rate. Thus, the energy required to cause dislocation motion in BCC metals increases with strain rate, leading to a higher effective yield strength and correspondingly a higher fatigue strength in UFT [

10]. In addition, the increased strain rate can potentially cause the deformation glide mechanisms to transition from the athermal regime to the thermally-activated regime, changing the crack initiation mechanisms from intragranular slip band formation at conventional frequencies to intergranular cracking at ultrasonic frequencies [

11,

12]. Until the effect of the test frequency on the fatigue behaviour for ferritic steels can be fully quantified, the usability of UFT to produce VHCF data that is applicable to conventional frequency applications remains limited.

Bach et al. [

5] proposed a frequency sensitivity parameter,

m, based on the Hart strain rate sensitivity equation [

13]. Parameter

m is evaluated by comparing the stress amplitude of specimens that lasted for an equivalent number of cycles to failure at each test frequency, thereby providing a method to quantify the frequency sensitivity of a material based on the finite life fatigue region. The definition of this proposed parameter is given in Equation (

1), where

is the stress amplitude and

f is the test frequency [

14]. The subscripts C and U are used to denote the values from Conventional and Ultrasonic frequency testing, respectively:

where

m was evaluated for C15E, C45E and C60E ferritic-pearlitic carbon steels. It was observed that the frequency sensitivity appears to correlate strongly with the ferrite volume % [

5]. Notably, this model has only been used as a comparative measure of the frequency sensitivity, and has not been applied to predict the frequency sensitivity for a given steel.

Guennec et al. [

12] produced a model, based on the Arrhenius relation, which predicts the fatigue limit of ferritic-pearlitic carbon steels based purely on the test frequency and ferrite content, as shown below:

where

is the fatigue limit,

is the quasistatic yield strength of the material,

is the ferrite volume content of the material,

is room temperature (

= 293 K),

is the frequency corresponding to the vibratory factor (taken as

[

12]), and

,

,

and

are all empirically obtained constants. A generalised form of the model (

2) was created by fitting it against a range of carbon steels from the literature. This generalised model was able to estimate the fatigue limit of a given steel at a specified test frequency, with an error of less than 10% in most cases.

In a previous investigation by the authors [

8,

9,

15], the average difference between the finite-life region S-N curves at conventional and ultrasonic frequencies was used to evaluate the frequency sensitivity for S275JR, S355JR, and Q355B grade structural steels. This average difference was also subtracted from the UFT S-N curve to act as a correction factor, which worked well for the S355JR, but not for the Q355B due to the observed change in the slope of the S-N curve.

Therefore, the aims of the current investigation are as follows. Firstly, S-N curves at both conventional and ultrasonic frequencies will be produced for the structural steel grade S275J2, to evaluate the influence of the test frequency on the fatigue resistance for this material. This data, combined with the previous literature results, will then be used to develop generalised frequency sensitivity models, which will also be applied as correction factors to the UFT data.

4. Generalised Frequency Sensitivity Model Development

A method was sought to estimate the difference between the CFT and UFT fatigue response for a given ferritic-pearlitic steel, without requiring a full set of test data to be produced at both frequencies. To accomplish this, a generalised model must be developed which can evaluate the difference between the fatigue response at conventional and ultrasonic frequencies of a steel, based only on its material properties.

To achieve this, a new frequency sensitivity model was developed, based on using the difference in the S-N curve parameters at conventional and ultrasonic frequencies as a measure of the frequency sensitivity. By examining how the parameters a and b shift at ultrasonic frequencies across a range of ferritic-pearlitic steels reported in the literature, an empirical relationship between these changes and the steels’ material properties can be established.

In addition to this original approach, an updated and generalised form of the strain rate sensitivity model proposed by Bach et al. [

5] will also be developed. Updated versions of the frequency sensitivity parameter,

m, will be proposed and fitted to the material properties of the literature steels, resulting in generalized versions of the model.

4.1. Selection of Literature Data

A number of additional test results for ferritic-pearlitic steels from the literature were considered in addition to the S275J2 results produced in this investigation. The literature results selected for comparison were for ferritic-pearlitic steels, which were tested at room temperature, and had a direct comparison between ultrasonic frequencies (20 kHz) and conventional frequencies (1–200 Hz). Important values such as the material strength, ferrite content, and fatigue limit at each frequency were extracted from the papers. The full list of papers and corresponding properties is detailed in

Table 4.

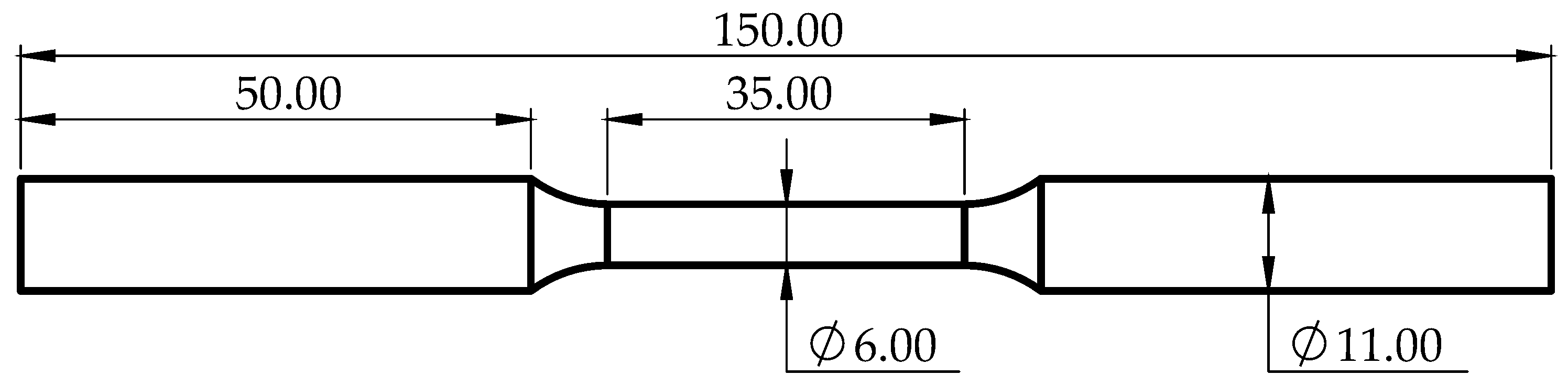

It is important to note that there is significant variability in the test procedures between the investigations. The test frequencies, especially at conventional frequencies, were not consistent, which may lead to inaccuracies when comparing them against each other. The number of cycles used for a run-out specimen also varied between the investigations, which will influence the point at which fatigue limit values are identified. Additionally, the specimen geometries varied between the different investigations, and in most cases, it was not kept consistent at both test frequencies, likely leading to size effects being present. The number of tested specimens in each investigation is also inconsistent, sometimes being as low as 3 for Nonaka et al. [

7], which may lead to inaccurate S-N curves. The S355J0 and S355J2 [

4] investigations also used liquid cooling instead of air cooling, which has sometimes been reported to cause a reduction in fatigue resistance from factors such as cavitation erosion in Trško et al. [

30]. The 0.13%C specimens investigated by Tsutsumi et al. [

6] had drilled holes to act as artificial initiation sites, which will reduce the number of cycles spent in the crack initiation phase.

It can therefore be seen that there is a large amount of variance in the test procedures throughout the literature, leading to large uncertainties when comparing results against each other. This highlights the need to develop a more prescriptive and widespread standard for UFT to ensure better consistency in future investigations. Until then, any observed trends between investigations can only be considered to be approximate.

For each of the literature steels,

and

were evaluated using the procedure described in

Section 3. Plots of the corresponding

and

values for each of the steels are presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, respectively.

For both approaches, a general increase in the frequency sensitivity with ferrite content can be seen; however, there is significant scatter in the results, especially beyond 70% ferrite volume %, where the increase in fatigue strength at ultrasonic frequencies ranges from 20–80%. Additionally, the moderate ferrite content materials (S45C, C45E) are well within the region of scatter of the high ferrite content materials and do not appear to be notably less sensitive to the test frequency, despite this being previously reported by Bach et al. [

5]. It is therefore difficult to identify a direct correlation between ferrite content and the frequency sensitivity using this approach alone.

Another factor that must be considered is the change in the gradient of the S-N curves at ultrasonic frequencies. Most of the literature steels exhibited a reduction in the slope of the S-N curve at ultrasonic frequencies, with the only exceptions being the C15E [

5] and the Wheel Steels tested by Li et al. [

28], which showed an increase in the gradient. The severity of this gradient reduction varied between materials, with it being very small for the C45E, S38C, S355JR and S275JR steels, and being very large for S45C, S355J0, 0.13%C, and Q355B steels.

4.2. Evaluation of the Change in S-N Curve Parameters

Taking an S-N curve in the form of Equation (

3), then the ratio of the survivable stress amplitude at low and high stress amplitudes at an equivalent number of cycles to failure,

N, can be defined using Equation (

4), where the

C and

U subscripts denote the conventional and ultrasonic frequency fatigue values, respectively. The change in the fatigue response at ultrasonic frequencies can therefore be defined by the two parameters: the change in the coefficient,

, which represents the change in intercept when plotted on a log-log graph, and the change in the exponent,

, which represents the change in the gradient when plotted on a log-log graph:

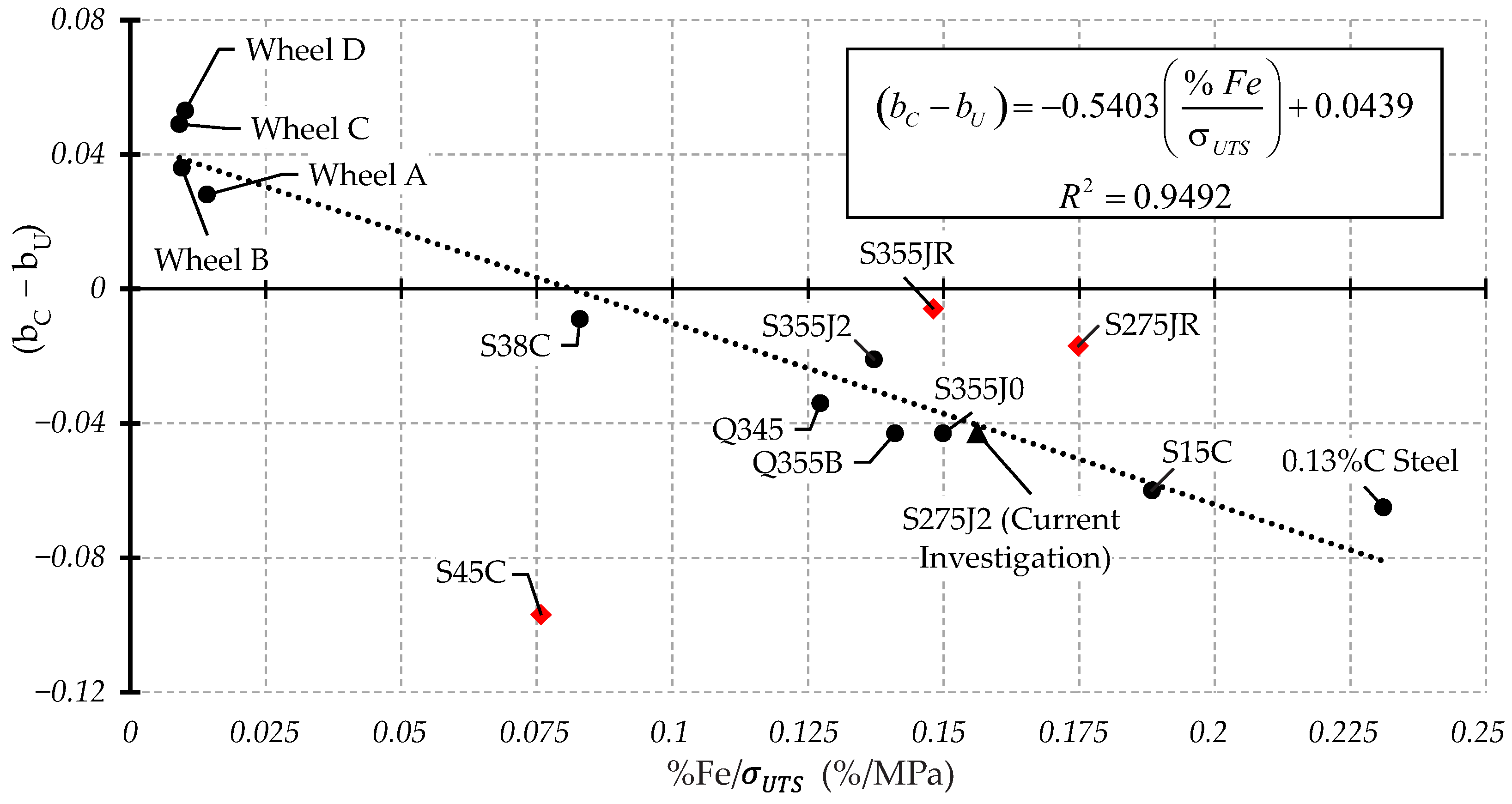

To produce a generalised model,

and

were therefore evaluated for all of the materials in

Table 4, and the corresponding values were plotted against different combinations of the material properties.

The material properties considered for comparison were the hardness, ferrite content, grain size, and strength, as well as combinations of these. Out of these options, it was found that the closest trends were against %Fe/

. The resultant scatter plots of

and

against %Fe/

are presented in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, respectively. A linear correlation was observed for both

and

, using a least-squares regression in Microsoft Excel, with a coefficient of determination of

= 0.8613 and

= 0.9492 respectively. Some outliers can be seen, however.

The S275JR and S355JR previously investigated by the authors also appear to be outliers, with a lower and a higher when compared to similar steels. It is proposed that this is indicative of specimen size influences when comparing across test frequencies, as these materials were both tested with larger cylindrical specimens at conventional frequencies. The equivalent steel grades tested by the authors with consistent geometries across the test frequencies (Q355B and S275J2) lie much closer to the other literature data and the corresponding trendlines.

Existing size effect models for UFT testing are typically predicated upon the size of an internal defect from which a crack originates [

31], and as such are not applicable to the materials in the current investigation, where UFT failures almost exclusively continue to originate from the specimen surface. As such, it is recommended for future work to carry out additional testing to robustly quantify and compare the influence of the size effect for ferritic steels under both CFT and UFT. As it stands, the S275JR and S355JR have been excluded when evaluating the trendline. Additionally, the S45C steel tested by Guennec et al. [

12] has a much higher

and a lower

than similar steels, as a result of the particularly steep gradient observed in the conventional frequency results. As such, the S45C was also excluded when evaluating the trendline. A table showing additional error metrics for the resultant

and

trendlines is provided in

Table 5.

4.3. Bach Frequency Sensitivity Model

The frequency sensitivity model proposed by Bach et al. [

5] was provided in Equation (

1) as it was presented in the original work; however, some modifications can be made to this model to enhance its accuracy. The model was based on Hart’s definition of a strain rate sensitivity parameter,

m, for a linear load relaxation test, as provided in Equation (

5) according to [

13], where

is the true stress and

is the strain rate:

To convert this to a cyclic load case, Bach et al. replaced

with stress amplitude,

, and replaced

with the test frequency,

f, to obtain Equation (

1) according to [

5]. The relationship between strain rate and test frequency is not linear for a sinusoidal load, however, as the strain rate also varies with the amplitude of the loading. Deriving the root mean square strain rate,

, in terms of the test frequency,

f, yields Equation (

6), which can then be substituted for

in Equation (

5) to obtain an updated form of the Bach frequency sensitivity model:

This is provided in Equation (

7), where the updated frequency sensitivity parameter is denoted by

:

Additionally,

m is not an inherent material parameter, as the observed

m value will vary depending on the CFT frequency,

, used to evaluate it. This can be demonstrated by applying the Bach model to the results produced at different CFT test frequencies for a single material by Guennec et al. [

26].

Figure 12 shows

m evaluated for the same S15C steel using the results from three different conventional frequencies. This trend is also observed when plotting

.

As can be seen in

Figure 12, the relationships between the frequency sensitivity parameters and

both follow a logarithmic trend. This logarithmic trend can therefore be used to correct

m or

to an arbitrary frequency of

= 20 Hz, provided that the ultrasonic frequency is kept constant at 20 kHz. Assuming the slope of this trendline is consistent between similar materials, this would allow better comparison of the frequency sensitivity between results that were produced at different test frequencies. The corresponding correction for

is given in Equation (

8), where

is the frequency sensitivity parameter evaluated at the conventional frequency

, and

is the frequency sensitivity parameter corrected to 20 Hz. Assuming that this trend is consistent between the literature materials,

can therefore be used to more accurately compare the frequency sensitivity of steels which were tested at different conventional frequencies:

The frequency sensitivity parameters

m,

, and

were evaluated for all of the literature steels. Parameters

m,

and

were evaluated for up to 5 pairs of data points for each material, with the average values for each being presented in

Figure 13. A negative

m value represents a material in which a reduction in the fatigue resistance was observed at ultrasonic frequencies. It is worth noting that, as these frequency sensitivity parameters are evaluated using pairs of data points at an equivalent number of cycles to failure at each frequency [

5], the resultant values are highly dependent on which specimens happened to last an equivalent number of cycles before failure. As such, evaluating

m,

, and

is particularly sensitive to the scatter in fatigue results. For some of the literature steels, there were no pairs of data points that were sufficiently close to each other, and thus the frequency sensitivity parameters could not be ascertained.

From

Figure 13, it can be seen that

m,

, and

all yield similar values for each of the steels, with the overall trends being the same for all three versions of the model. In all cases, the

and

values were slightly lower than the original

m values; however, with the biggest difference seen for the materials with the highest frequency sensitivity. As a result, this results in a small improvement in scatter over the original

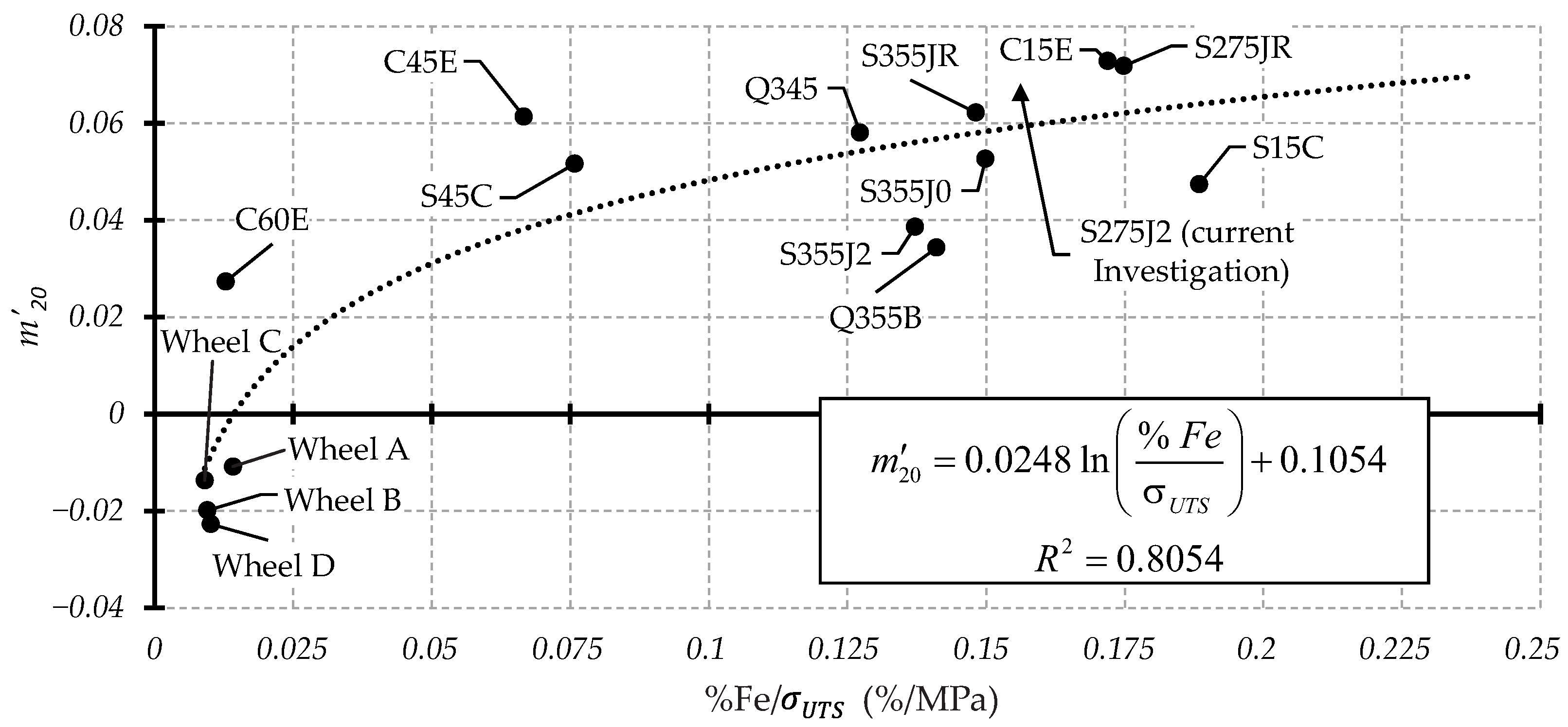

m model. A general increase in all of the frequency sensitivity parameters with ferrite content can be seen, with a large amount of scatter still present between 70 and 85% ferrite. In contrast to the approach using the empirical change in the S-N curve parameters, the S275JR, S355JR, and S45C results do not appear to be significant outliers. Following this, generalised versions of the Bach model were produced based on both the

and

parameters. Parameters

and

were evaluated as a function of the material properties, following the same procedure outlined for

and

in

Section 4.2. It was again found that the best trends were against %Fe/

, as shown in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 for

and

respectively. Logarithmic trendlines were fitted to the experimental data using a least-squares regression in Microsoft Excel. Notably, the

version of the model exhibits an improved correlation coefficient in comparison to the

version, with

values of 0.8054 and 0.7467 for the two versions, respectively. This shows that the test frequency used to carry out the CFT tests does have a tangible influence on the measured frequency sensitivity, contributing to the scatter observed between the results. As such, it is clear that for a generalised frequency sensitivity model to be sufficiently robust, it must take into account any variations in the CFT test frequency. Additional error metrics for the

and

trendlines are presented in

Table 6.

5. Application of Models as UFT Correction Factors

With generalised versions of the frequency sensitivity models now produced, it was desired to evaluate whether they could be suitably used to correct the UFT S-N curves to match the CFT test data, which would enable the accelerated evaluation of fatigue data for lower frequency applications.

To use the empirical change in the S-N curve as a correction factor,

and

can be evaluated for a given steel using the relation in

Figure 10, then applied to the coefficients of the UFT S-N curve to evaluate the equivalent CFT curve. For comparison, the

correction and

correction were each applied separately to the UFT S-N curve, as well as applying both corrections together.

To apply the modified Bach model as a correction factor, Equation (

7) can be rearranged to give the low frequency stress amplitude

, in terms of the high frequency stress amplitude,

and the frequency sensitivity parameter,

, as presented in Equation (

9). Hence, by evaluating the

value for a given steel using the relation in

Figure 14, the UFT stress amplitude can be converted into an equivalent CFT stress amplitude:

For additional comparison, the generalised frequency sensitivity model previously proposed by Guennec et al. [

12] was also applied as a correction factor by combining Equation (

2) for both the UFT and CFT test frequencies, to evaluate the ratio of the corresponding fatigue limits. This yields the relationship in Equation (

10):

The corrected UFT curves produced using each of these methods are compared against the actual CFT data for the S275J2 steel in

Figure 16. For comparison, the corrected UFT curves are also evaluated for the Q355B from the previous investigation by the authors [

15], in

Figure 17.

The corrections from the Bach and Guennec models all provide a similar response, as they both shift the ultrasonic S-N curve directly downwards with no correction made to the gradient. As previously discussed in

Section 4.1, however, a reduction in the S-N curve gradient is commonly observed for ferritic steels tested in UFT. Neither the Generalised Bach nor Guennec models consider this change in gradient, resulting in the corresponding corrected UFT curves not being aligned with the CFT test results. This highlights the inaccuracies of using these models directly as correction factors and the necessity of including a gradient correction. For the empirical change in the S-N curve approach, it can immediately be seen that applying only the intercept correction,

, provided an inaccurate result, as in many cases the intercept of the S-N curve was actually higher in the CFT tests than in the UFT tests. Therefore, applying the intercept correction alone inaccurately predicted a greater fatigue resistance at the lower test frequencies. Note, however, that

has previously been successfully applied as a correction factor for 34CrNiMo6 and 42CrMo4 alloy steels by Teixeira et al. [

32], and thus this approach may still be viable for other classes of steel.

From all of the evaluated correction factors, it was found that either applying only the empirical gradient correction, , or both the and corrections together provide the best estimations of the CFT S-N curves. Both of these approaches captured the change in gradient for the S275J2 and Q355B steels, as well as approximately aligning with the stress amplitude range of the CFT data.

In

Figure 18, the number of cycles to failure evaluated from the corrected UFT S-N curves is compared to the corresponding value from the CFT S-N curve at an equivalent stress amplitude, in order to evaluate the accuracy of the corrected curves. For both of the steels, it can be seen that applying

and

together provided a non-conservative estimate of the CFT curve. For the S275J2, the number of cycles to failure from the corrected curve was overestimated by a factor of 20, which would be unusable for design applications. For the Q355B steel, the number of cycles to failure was overestimated by 2–10 times. Applying only

provides conservative estimates of the CFT S-N curves, with the number of cycles to failure being underestimated for both of the steels. For the S275J2, the corrected S-N curve was within a factor of 1.3 of the CFT curve along the full finite life region. For the Q355B, however, the corrected UFT S-N curve underestimated the CFT curve by approximately one decade, diverging further at low numbers of cycles to failure.

Out of the models applied in the current investigation, it can therefore be seen that the UFT S-N curve corrected using

provided the best estimate of the CFT data: approximating the slope of the CFT S-N curve and providing conservative estimates of the conventional frequency fatigue life for both materials. However, there is still significant variability in how much the corrected curve undercuts the conventional frequency data, with the Q355B CFT results in particular being underestimated by approximately one decade. The further the

value for a given steel strays from the empirical trendline in

Figure 11, the greater the difference between the corrected UFT and CFT results will be.

The key to improving the accuracy of this approach would therefore be to improve the correlation between

and the material parameters in

Figure 11, by further identifying and evaluating the causes of the scatter. Due to the reliance on the disparate literature data to build the generalised versions of these models, however, it is currently difficult to determine how much of the scatter in the correlation is due to stochastic fatigue effects, due to the influence of additional material factors, or due to the variance in the test parameters between the different investigations. To achieve this goal, it would therefore be necessary to test a wide range of ferritic steels with equivalent specimen geometries under a consistent set of test conditions. From this data, a more accurate correlation for

could be determined, leading to the production of a more consistently reliable correction factor.