Designing Innovative Digital Solutions in the Cultural Heritage and Tourism Industry: Best Practices for an Immersive User Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Immersive Technology Applications for Advanced Cultural Experience

2.2. Tips and Attributes for Designing Cloud-Based Solutions for CH

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Definition of the Survey-Based Questionnaire

3.2. Administration of the Survey

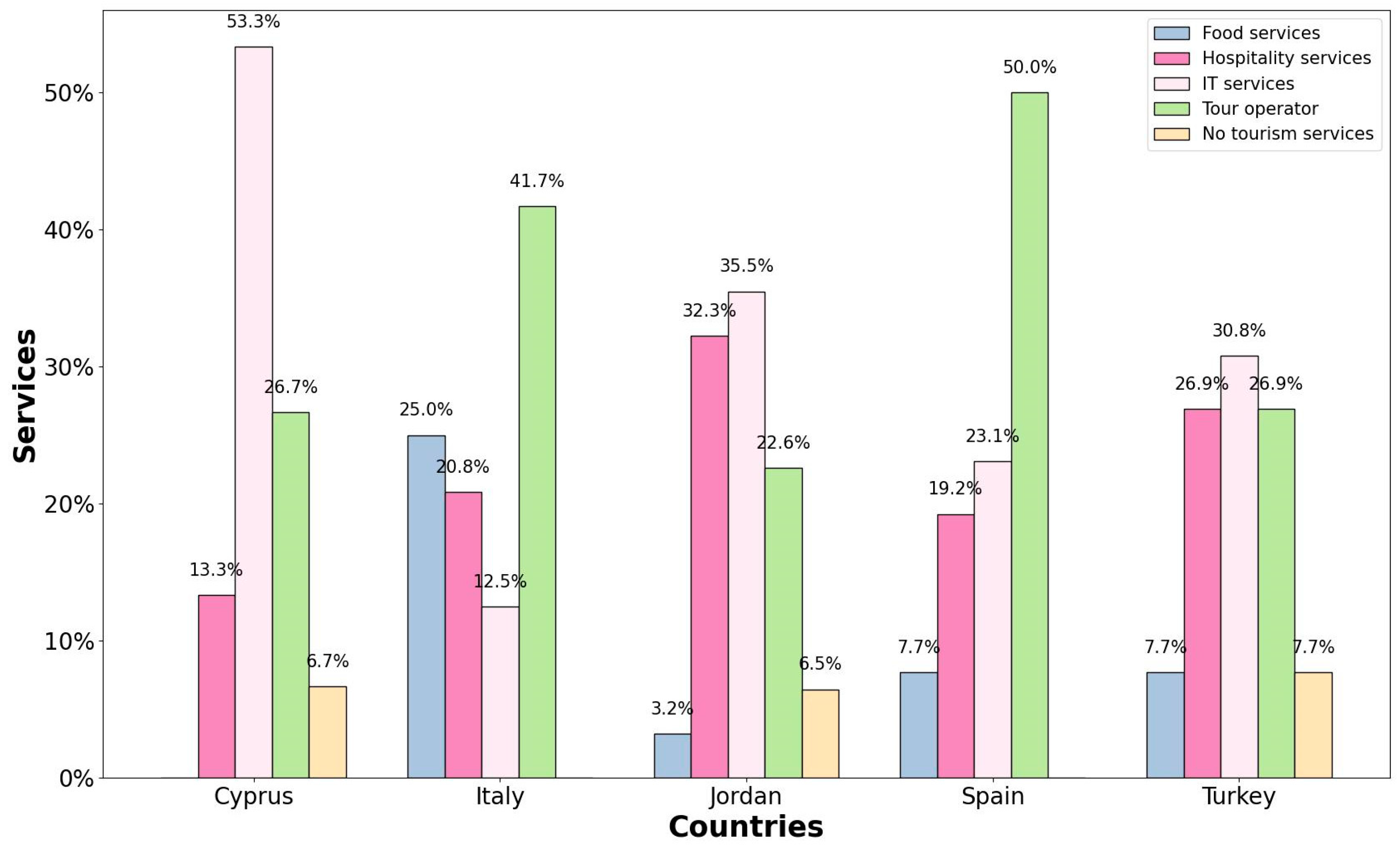

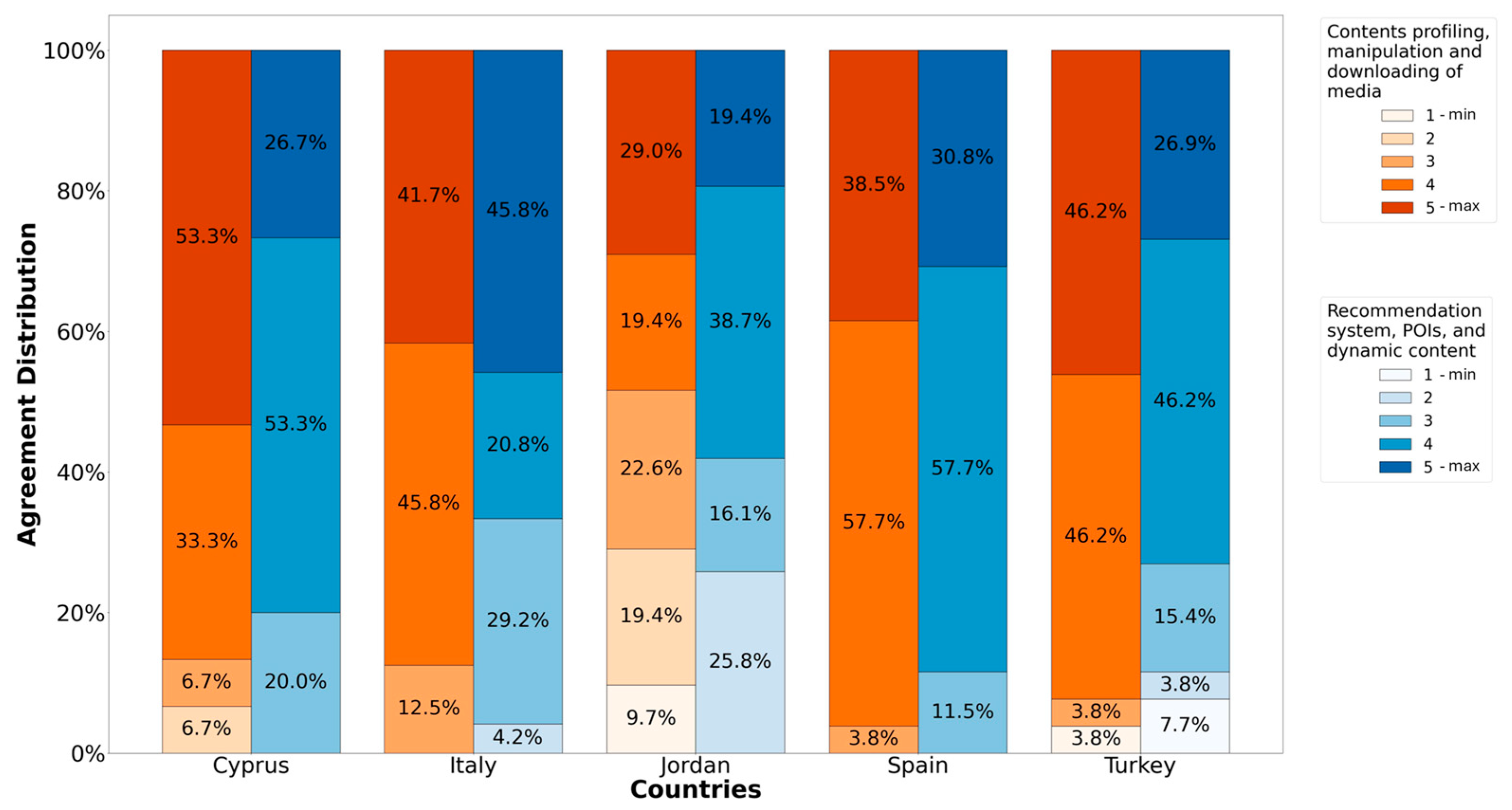

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- SMEs are fully aware of the potential value coming from digital technologies in CH, and most of them intend to invest in such initiatives;

- A cloud-based platform for tourism is seen as a useful digital solution to more effectively and resiliently satisfy visitors’ expectations;

- Among the most important technologies to integrate in such platforms, SMEs focus on XR technologies, IoT, sensors, and data-driven services, in order to provide immersive and customized CH journeys;

- XR technology is essential for virtual heritage, offering users an immersive experience, even though it requires advanced visualization techniques and tools to fully use contents;

- SMEs need to integrate a recommendation system for suggesting sites, products, and services based on user preference data.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Del Vecchio, V.; Menegoli, M. Internet of Things and Industrial Business Models: Knowledge Boundaries and Practical Implications. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th Blockchain and Internet of Things Conference, Osaka, Japan, 21–23 July 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nuenen, T.; Scarles, C. Advancements in technology and digital media in tourism. Tour. Stud. 2021, 21, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontopanagou, K.; Tsipis, A.; Komianos, V. Fostering Cultural Awareness in Museums and Monuments by Employing Extended Reality. Glob. J. Archaeol. Anthr. 2024, 13, 555870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.H.; Douglas, E.J. Resource reconfiguration by surviving SMEs in a disrupted industry. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2024, 62, 140–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratisto, E.H.; Thompson, N.; Potdar, V. Immersive technologies for tourism: A systematic review. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2022, 24, 181–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, N. The scenographic turn: The pharmacology of the digitisation of scenography. Theatr. Perform. Des. 2015, 1, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueser, D.; Vlachos, P. Almost like being there? A conceptualisation of live-streaming theatre. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2018, 9, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, E.; Hong, A. OTT Streaming Distribution Strategies for Dance Performances in the Post-COVID-19 Age: A Modified Importance-Performance Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valbom, L.; Marcos, A. WAVE: Sound and music in an immersive environment. Comput. Graph. 2005, 29, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaytoue, M.; Silva, A.; Cerf, L.; Meira, W.; Raïssi, C. Watch me playing, I am a professional: A first study on video game live streaming. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on World Wide Web, Lyon, France, 16–20 April 2012; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, V.; Lazoi, M.; Lezzi, M. An Overview on Technologies for the Distribution and Participation in Live Events. In Extended Reality; De Paolis, L.T., Arpaia, P., Sacco, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13445, pp. 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocente, C.; Ulrich, L.; Moos, S.; Vezzetti, E. A framework study on the use of immersive XR technologies in the cultural heritage domain. J. Cult. Herit. 2023, 62, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maietti, F. Heritage Enhancement through Digital Tools for Sustainable Fruition—A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okanovic, V.; Ivkovic-Kihic, I.; Boskovic, D.; Mijatovic, B.; Prazina, I.; Skaljo, E.; Rizvic, S. Interaction in eXtended Reality Applications for Cultural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistola, T.; Diplaris, S.; Stentoumis, C.; Stathopoulos, E.A.; Loupas, G.; Mandilaras, T.; Kalantzis, G.; Kalisperakis, I.; Tellios, A.; Zavraka, D.; et al. Creating immersive experiences based on intangible cultural heritage. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Reality (ICIR), Piscataway, NJ, USA, 12–13 May 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, A.; Pariso, P.; Picariello, M. Digital platforms and entrepreneurship in tourism sector. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2022, 9, 282–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhbauer, S.L.; Hausmann, A. Cooperation for the implementation of digital applications in rural cultural tourism marketing. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 16, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, A.; Rodríguez, I.; Arcos, J.L.; Rodríguez-Aguilar, J.A.; Cebrián, S.; Bogdanovych, A.; Morera, N.; Palomo, A.; Piqué, R. Lessons learned from supplementing archaeological museum exhibitions with virtual reality. Virtual Real. 2020, 24, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, F. An examination on the use of immersive reality technologies in the travel and tourism industry. Bus. Manag. Stud. Int. J. 2020, 8, 2348–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, C. Commercialization without over-commercialization: Normative conundrums across heritage rationalities. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 27, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, V.; Lazoi, M.; Lezzi, M. Digital Twin and Extended Reality in Industrial Contexts: A Bibliometric Review. In Extended Reality; De Paolis, L.T., Arpaia, P., Sacco, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14218, pp. 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, G.; D’errico, G.; De Luca, V.; Barba, M.C.; De Paolis, L.T. Hand Tracking for XR-Based Apraxia Assessment: A Preliminary Study. In Proceedings of the 19th Nordic-Baltic Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Medical Physics, Liepaja, Latvia, 12–14 June 2023; Dekhtyar, Y., Saknite, I., Eds.; IFMBE Proceedings; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 89, pp. 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, G.; Barba, M.C.; D’errico, G.; Küçükkara, M.Y.; De Paolis, L.T. eXtended Reality & Artificial Intelligence-Based Surgical Training: A Review of Reviews. In Extended Reality; De Paolis, L.T., Arpaia, P., Sacco, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14218, pp. 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museen der Stadt Wien-Stadtarchäologie. In In Monumental Computations, Proceedings of the International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies, Vienna, Aus-tria, 4–6 November 2019; Propylaeum: Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhu, Y. A Survey of Museum Applied Research Based on Mobile Augmented Reality. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 2926241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morciano, F.; Mondellini, M.; D’errico, G.; Gatto, C.; Pellegrino, G.; Antonietti, A.; Palesi, F.; De Paolis, L.T. Assessment of Neuroaesthetic Criteria to Select Hedonic Stimuli for Rehabilitation: A Preliminary Study. In Extended Reality; De Paolis, L.T., Arpaia, P., Sacco, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 15029, pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmigniani, J.; Furht, B.; Anisetti, M.; Ceravolo, P.; Damiani, E.; Ivkovic, M. Augmented reality technologies, systems and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2011, 51, 341–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; An, H.; Chen, W.; Pan, Z. A Survey on Mobile Augmented Reality Visualization. J. Comput. Des. Comput. Graph. 2018, 30, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corallo, A.; Del Vecchio, V.; Lezzi, M.; Morciano, P. Shop Floor Digital Twin in Smart Manufacturing: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skublewska-Paszkowska, M.; Milosz, M.; Powroznik, P.; Lukasik, E. 3D technologies for intangible cultural heritage preservation—Literature review for selected databases. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, H.T.; Lim, C.K.; Ahmed, M.F.; Tan, K.L.; Bin Mokhtar, M. Virtual Reality Usability and Accessibility for Cultural Heritage Practices: Challenges Mapping and Recommendations. Electronics 2021, 10, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chianese, A.; Piccialli, F. Designing a smart museum: When cultural heritage joins IoT. In Proceedings of the 2014 8th International Conference on Next Generation Mobile Applications, Services and Technologies, Oxford, UK, 10–12 September 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, M.K. Clouds-Based Collaborative and Multi-Modal Mixed Reality for Virtual Heritage. Heritage 2021, 4, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debandi, F.; Iacoviello, R.; Messina, A.; Montagnuolo, M.; Manuri, F.; Sanna, A.; Zappia, D. Enhancing cultural tourism by a mixed reality application for outdoor navigation and information browsing using immersive devices. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Florence, Italy, 16–18 May 2018; Volume 364, p. 012048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvak, E.; Kuflik, T. Enhancing cultural heritage outdoor experience with augmented-reality smart glasses. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2020, 24, 873–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbi, B.; Marasco, A. Co-designing Cultural Heritage Experiences for All with Virtual Reality: A Scenario-Based Design approach. Um. Digit. 2022, 11, 71–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, K.; Bennett, C.L.; Wobbrock, J.O. How Designing for People with and with Disabilities Shapes Student Design Thinking. In Proceedings of the 18th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Reno, NV, USA, 23–26 October 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, E.; Merchán, P.; Merchán, M.J.; Salamanca, S. Virtual Reality to Foster Social Integration by Allowing Wheelchair Users to Tour Complex Archaeological Sites Realistically. Remote. Sens. 2020, 12, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masciotta, M.; Morais, M.; Ramos, L.; Oliveira, D.; Sánchez-Aparicio, L.J.; González-Aguilera, D. A Digital-based Integrated Methodology for the Preventive Conservation of Cultural Heritage: The Experience of HeritageCare Project. Int. J. Arch. Herit. 2021, 15, 844–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teruggi, S.; Grilli, E.; Fassi, F.; Remondino, F. 3D surveying, semantic enrichment and virtual access of large cultural heritage. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, VIII-M-1–2021, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corallo, A.; Esposito, M.; Marra, M.; Pascarelli, C. Transmedia Digital Storytelling for Cultural Heritage Visiting Enhanced Experience. In Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Computer Graphics; De Paolis, L.T., Bourdot, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11614, pp. 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathioudakis, G.; Klironomos, I.; Partarakis, N.; Papadaki, E.; Anifantis, N.; Antona, M.; Stephanidis, C. Supporting Online and On-Site Digital Diverse Travels. Heritage 2021, 4, 4558–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, M.S.; Woods, P.; Thwaites, H. Designing and developing a location-based mobile tourism application by using cloud-based platform. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Technology, Informatics, Management, Engineering and Environment, Bandung, Indonesia, 23–26 June 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldeon, J.; Díaz, E.; Auccapuri, D.; Masuda, A.; Gálvez, R.; Arana, A.; Chávez, P.; Hernández, V.; Lau, M.E. ECOPACAYA 4.0: An Innovation Augmented Reality Based Application for Ecotourism and Scientific Tourism in the Pacaya Samiria Amazon Lodge Private Reserve in the Amazon Jungle of Loreto, Peru. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Lima, Peru, 8–11 March 2023; IEOM Society International: Southfield, MI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertacchi, S.; Al Jawarneh, I.M.; Apollonio, F.I.; Bertacchi, G.; Cancilla, M.; Foschini, L.; Grana, C.; Martuscelli, G.; Montanari, R. SACHER Project: A Cloud Platform and Integrated Services for Cultural Heritage and for Restoration. In Proceedings of the 4th EAI International Conference on Smart Objects and Technologies for Social Good, Bologna, Italy, 28–30 November 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.A.; Welsh, K.E.; Mauchline, A.L.; France, D.; Whalley, W.B.; Park, J. Do educators realise the value of Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) in fieldwork learning? J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, V.; Lazoi, M.; Marche, C.; Mettouris, C.; Montagud, M.; Specchia, G.; Ali, M.Z. Designing Digital Solutions in the Cultural Heritage and Tourism Industry for Advancing Visitors’ Experiences: SMEs Needs, Preferences, and Expectations. In Extended Reality; De Paolis, L.T., Arpaia, P., Sacco, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 15029, pp. 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corallo, A.; Crespino, A.M.; Del Vecchio, V.; Gervasi, M.; Lazoi, M.; Marra, M. Evaluating maturity level of big data management and analytics in industrial companies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 196, 122826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, B.R.; Templeton, G.F.; Byrd, T.A. A methodology for construct development in MIS research. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2005, 14, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P. Construct Measurement and Validation Procedures in MIS and Behavioral Research: Integrating New and Existing Techniques. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 293–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reja, U.; Manfreda, K.; Hlebec, V.; Vehovar, V. Open-ended vs. Close-ended Questions in Web Questionnaires. Dev. Appl. Stat. 2003, 19, 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, A.C.; Kaminski, P.C. A reference model to determine the degree of maturity in the product development process of industrial SMEs. Technovation 2012, 32, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoumrungroje, A.; Racela, O.C. Linking SME international marketing agility to new technology adoption. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2022, 40, 801–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ali, M.; Rauch, E.; Matt, D.T. Exploring the Synergy of Digitalization and IoT: A Literature Review on Energy Monitoring for SMEs. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Vallette, Malta, 1–4 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelelli, M.; Catalano, C.; Hill, D.; Koshutanski, H.; Pascarelli, C.; Rafferty, J. A Reference Architecture Proposal for Secure Data Management in Mobile Health. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech), Split/Bol, Croatia, 5–8 July 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqoud, A.; Schaefer, D.; Milisavljevic-Syed, J. Industry 4.0: A systematic review of legacy manufacturing system digital retrofitting. Manuf. Rev. 2022, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelelli, M.; Gervasi, M.; Ciavolino, E. Representations of epistemic uncertainty and awareness in data-driven strategies. Soft Comput. 2024, 28, 13763–13780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Questions | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Section 1: information on responding SMEs | ||

| 1 | Country | Italy, Jordan, Spain, Turkey, Cyprus |

| 2 | SME size | Micro, Small, Medium, Large |

| 3 | What is your reference cultural heritage site? | Open-ended question |

| 4 | What is your core business type? | Service provider, product developer, both |

| 5 | If you are a service provider, what type of services do you provide? | Tourism operator, hospitality, IT and digital services, restaurant, food, not providing services, other |

| Section 2: information on SMEs’ needs, preferences, expectations | ||

| 6 | Do you believe that technology, such as mobile applications and cloud-based platforms, can provide benefits for enhancing cultural heritage experiences? | Yes/No |

| 7 | How familiar are you with the concept of using technology to enhance cultural heritage experiences? | 1–5 |

| 8 | In your opinion, how important is it for SMEs to invest in digital solutions for enhancing cultural heritage experiences? | 1–5 |

| 9 | How interested are you in leveraging digital tools to enhance visitor experiences at cultural heritage sites? | 1–5 |

| 10 | Would your SME benefit from having access to a cloud-based platform for managing and delivering cultural heritage content? | Yes/No |

| 11 | How likely would you be to use a platform that offers services such as content profiling, manipulation, and downloading of various media types related to cultural heritage? | 1–5 |

| 12 | Do you see value in incorporating features like object recognition and 3D reconstruction to provide immersive experiences at cultural heritage sites? | Yes/No |

| 13 | How important do you consider features like a recommender system, Points of Interest (POIs), and dynamic content enhancement based on visitor preferences? | 1–5 |

| 14 | How likely are you to utilize data obtained from sensors within the cultural heritage site to enhance visitor experiences? | 1–5 |

| 15 | Are you concerned about the costs associated with developing and maintaining such a digital solution? | Yes/No |

| 16 | Would you be willing to allocate resources (time, budget, etc.) towards the development and maintenance of such a cultural heritage application? | Yes/No |

| 17 | Do you have any reservations regarding data privacy and security when utilizing cloud-based services for cultural heritage applications? | Yes/No |

| 18 | Would you consider investing in or partnering with developers to create a digital solution for enhancing cultural heritage experiences in the future? | Yes/No |

| 19 | How likely are you to recommend adopting digital tools for cultural heritage to other SMEs in your industry? | 1–5 |

| 20 | Overall, how beneficial would it be for your SME to invest in an application connected to a cloud-based platform that offers these features for cultural heritage? | 1–5 |

| 21 | Is there any specific feature or functionality that you believe would be crucial for the success of a cultural heritage application connected to a cloud-based platform? | Multiple choice |

| 22 | Do you have any other suggestions or insights regarding the integration of technology into cultural heritage preservation and visitor engagement efforts? | Open-ended question |

| 23 | What knowledge or resources do you feel are lacking in your current operations? | Open-ended question |

| 24 | What specific skills or expertise would you seek in a potential strategic alliance partner? | Open-ended question |

| 25 | Are you currently exploring international markets or considering expanding internationally? | Closed-ended question |

| 26 | What barriers do you perceive in entering or expanding into international markets? | Open-ended question |

| 27 | Are there any complementary products or services that could enhance your offerings or address current gaps in your business? | Open-ended question |

| 28 | What types of partnerships or collaborations do you envision would be most beneficial for your business growth? | Open-ended question |

| 29 | How much are you interested in forming collaborations with other SMEs? | 1–5 |

| 30 | How hard is it to form a collaboration starting from an independent initiative? | 1–5 |

| 31 | What is the usefulness of using incubators for knowledge transfer? | 1–5 |

| 32 | How useful is it to have a specific training for innovative technologies in cultural heritage? | 1–5 |

| 33 | What factors would influence your decision to enter into a strategic alliance? | Open-ended question |

| 34 | Percentage of your revenues from local market? | Closed-ended question |

| 35 | Percentage of your revenues from international markets? | Closed-ended question |

| 36 | What are your long-term goals and objectives for your business? | Open-ended question |

| 37 | How do you envision strategic alliances contributing to the achievement of these goals? | Open-ended question |

| Service | Description | Total | Cyprus | Italy | Jordan | Spain | Turkey |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | Third-party services integration | 41.80% | 8.62% | 13.76% | 0.00% | 10.32% | 12.20% |

| ii | Platform services support | 2.46% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.94% | 0.00% |

| iii | Social community | 31.15% | 6.90% | 7.34% | 0.00% | 8.39% | 10.57% |

| iv | Story generator | 9.02% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 7.28% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| v | Setup walkthrough for beacons to the IoT established network | 41.80% | 5.17% | 2.75% | 9.93% | 12.26% | 8.94% |

| vi | Recommendations based on accumulated knowledge from data | 59.02% | 13.79% | 16.51% | 7.28% | 10.32% | 15.45% |

| vii | Recognition of 3D objects for MR apps | 57.38% | 17.24% | 12.84% | 6.62% | 12.26% | 13.82% |

| viii | Gaming contents to the platform of choice | 13.11% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 9.93% | 0.65% | 0.00% |

| ix | Profiling and personalized manager | 60.66% | 5.17% | 15.60% | 8.61% | 10.97% | 19.51% |

| x | Privacy and security management | 0.82% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.66% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| xi | Point-cloud to model (to support MR) | 8.20% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 6.62% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| xii | IoT network establishment walkthrough | 33.61% | 10.34% | 6.42% | 7.28% | 10.97% | 0.00% |

| xiii | Expert system-based itinerary planner | 30.33% | 8.62% | 7.34% | 4.64% | 8.39% | 3.25% |

| xiv | Data analysis and knowledge building | 9.02% | 0.00% | 1.83% | 5.96% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| xv | Content access | 73.77% | 24.14% | 15.60% | 11.92% | 13.55% | 16.26% |

| xvi | Cloud-based recognition of target images (MR apps) | 9.02% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 7.28% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| xvii | Advanced visualization | 7.38% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 5.96% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Country | Local Market | International Market |

|---|---|---|

| Average | 57.65% | 31.41% |

| Cyprus | 47.87% | 38.57% |

| Italy | 57.00% | 29.00% |

| Jordan | 56.29% | 34.68% |

| Spain | 66.92% | 21.92% |

| Turkey | 55.77% | 35.00% |

| ID | Best Practices |

|---|---|

| 1 | For extended and immersive user experience, digital contents, mobile applications, cloud-based platforms, and XR tools need to be combined |

| 2 | CH platforms should be supported by IoT technology, smart devices, beacon sensors, and 3D models to enable real-time and context-aware interactions |

| 3 | User data should be collected and elaborated for providing customers with tailored services and customized experience based on their interests and preferences |

| 4 | Gamification and storytelling elements make cultural exploration more engaging and educational |

| 5 | SMEs should focus on developing analytics and data-driven capabilities to extract valuable insights from IoT data, which can help optimize visitor journeys and operational efficiency |

| 6 | Data privacy and security frameworks need to be implemented to establish a trustworthy relationship between users and technologies |

| 7 | Digital content should be created, managed and provided according to regional preferences, customization needs, and cultural diversity |

| 8 | Visitors need to be supported, both physically and digitally, in all the phases of their experience, from journey planning, to site visiting, and after their experience |

| 9 | Digital applications and services should be designed to ensure a valuable customer experience both in the physical site and remotely |

| 10 | Digital solutions should engage customers beyond their experience in terms of time, space, and provided value |

| 11 | CH platforms should be integrated with third-party services in order to provide the customer with complementary and additional services |

| 12 | Social community enhances the sense of belonging to a group of people with common interests and preferences with whom they share emotions and perceptions |

| 13 | Digital user data should be accurately stored and analyzed for elaborating insights and foresights based on historical data |

| 14 | Digital platforms should be associated with the use of multimodal interaction interfaces to ensure inclusivity |

| 15 | Open standards and tools should be used to facilitate interoperability and scalability of digital solutions with third parties |

| 16 | AI predictive models should be integrated for improving visitors flow management |

| 17 | Adaptive learning and educational models could be customized for different user segments |

| 18 | Platforms should be designed to provide value for customers and SMEs in terms of site visiting, management, and maintenance |

| 19 | Ethical concerns should be considered for a sustainable use of cultural heritage |

| 20 | CH platforms should have robust backup and disaster recovery mechanisms to protect digital cultural assets from cyber threats or system failures |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Del Vecchio, V.; Lazoi, M.; Marche, C.; Mettouris, C.; Montagud, M.; Specchia, G.; Ali, M.Z. Designing Innovative Digital Solutions in the Cultural Heritage and Tourism Industry: Best Practices for an Immersive User Experience. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4935. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15094935

Del Vecchio V, Lazoi M, Marche C, Mettouris C, Montagud M, Specchia G, Ali MZ. Designing Innovative Digital Solutions in the Cultural Heritage and Tourism Industry: Best Practices for an Immersive User Experience. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(9):4935. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15094935

Chicago/Turabian StyleDel Vecchio, Vito, Mariangela Lazoi, Claudio Marche, Christos Mettouris, Mario Montagud, Giorgia Specchia, and Mostafa Z. Ali. 2025. "Designing Innovative Digital Solutions in the Cultural Heritage and Tourism Industry: Best Practices for an Immersive User Experience" Applied Sciences 15, no. 9: 4935. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15094935

APA StyleDel Vecchio, V., Lazoi, M., Marche, C., Mettouris, C., Montagud, M., Specchia, G., & Ali, M. Z. (2025). Designing Innovative Digital Solutions in the Cultural Heritage and Tourism Industry: Best Practices for an Immersive User Experience. Applied Sciences, 15(9), 4935. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15094935