1. Introduction

The aging population is a reality in most human societies. According to Bloom et al. [

1], people over 60 were estimated at 800 million in 2011 but they are expected to reach 2 billion by 2050, meaning that the elderly population will expand significantly. This large segment of the population cannot remain inactive for social, political, and economic reasons. For example, with the younger workforce reducing, it is a necessity that healthy older adults continue to work and support economies with their consumer power. It is also essential that older people participate in democratic procedures and social life, contribute with their life experiences, knowledge, and wisdom to help younger generations, etc. However, to achieve all these goals, reduce healthcare costs, and keep socially, politically, and economically active, older individuals need to remain healthy. Studies have shown that elders remain healthy for longer when they remain active physically [

2] and mentally [

3].

Cultural heritage is a great medium to keep people involved since it offers experiences on many levels. For example, cultural heritage provides a sense of identity and belonging, connecting individuals to their roots and heritage [

4], as well as to the societies they belong to by creating common understandings and shared values [

5]. When interacting with heritage and the rich stimulation it offers, cognitive ability is enhanced [

6]. Among the many cognitive benefits, learning is widely acknowledged as a part of cultural experiences [

7]. Cultural heritage can also trigger creativity [

8]. In addition, cultural heritage can evoke strong emotions, such as joy, pride, and inspiration, contributing to overall emotional wellbeing [

9].

Virtual reality (VR) is a great medium to explore cultural heritage since it can make heritage and knowledge accessible to more people. Technology can also allow the personalization of experiences to match people’s needs and interests [

10], increasing motivation to participate in cultural experiences [

11].

Regarding the elderly, research is still scarce regarding VR cultural experiences for this age group. In addition, most studies focus on accessibility, immersion, and presence issues (e.g., [

12]) and/or visitor satisfaction and benefits [

13]. Very few studies, if any, focus on VR cultural content. Usually, content is designed before user testing, and content creation seems to be an intuitive process. Thus, the present work aims to gather content requirements for VR cultural experiences for the elderly.

2. Virtual Reality in Cultural Heritage for the Elderly

Over the last few years, virtual reality applications have been used more and more in cultural heritage [

14] to increase engagement and interaction with cultural content. In particular, during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, virtual applications were employed to keep people connected with cultural heritage content, and different approaches to mix the physical and the virtual were explored [

15,

16]. Moreover, museum visitors, and especially younger individuals, seem to have high levels of acceptance of VR in cultural experiences and there are learning gains while they engage with VR environments [

17]. Visitors also report higher levels of satisfaction with the use of VR in cultural settings [

18]. Immersive VR environments allow users to better understand both tangible and intangible aspects of the experience [

19]. VR can support different types of cultural experiences from storytelling to 360 video [

12,

20] and games with very positive findings [

21]. It seems that VR can enhance museum learning [

22], and it can be also used to help with the preservation of cultural heritage [

23]. Systematic reviews of the field [

11] reveal the challenges but also show the potential of VR applications in cultural heritage [

24].

2.1. Virtual Reality and the Elderly

The potential of VR in increasing the quality of life of older adults is recognized in the literature. In different studies, VR has been used to identify cognitive disorders [

25], assist rehabilitation [

26], and train elders’ cognitive [

27,

28] and motor skills [

29,

30], effectively using people’s free time [

31] and increasing satisfaction and wellbeing. In a study by Matsangidou et al. [

32], VR is used to provide rich and emotional experiences for people with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, showing the benefits of its use for this group of participants.

2.2. Virtual Reality in Cultural Heritage for the Elderly

Currently, most digital heritage ICT applications are designed with the average young, healthy person in mind [

33,

34]. However, cultural institutions are increasingly aiming to include older adults, including those with mild cognitive impairment. While initiatives like the Museum of Cycladic Art’s (Greece) VR-guided tours for nursing homes are promising, adapting existing VR applications for the elderly presents unique challenges. Older adults often have a deep personal connection to cultural heritage and can enrich the experience by sharing their own stories and memories related to historical sites and monuments. It is crucial to provide opportunities for them to participate in discussions and interpretations, as well as to design virtual experiences that evoke emotional and sensory responses [

35,

36]. Recent research focused on the therapeutic aspects of combining VR and cultural heritage for the elderly who feel lonely, showing that it could become a powerful tool to increase the wellbeing of this age group [

37].

VR is also used to increase social interactions, and people can interact with others in a network in the virtual world [

38,

39]. However, to reach real networked virtual reality solutions, a few challenges need to be addressed, like the capacity of broadband networks, wireless operation, ultra-low latency, client/network access, system deployment, edge computing/cache, and end-to-end reliability [

40,

41]. In addition, when multiple users are involved and they need to have real-time experiences, more challenges regarding network performance arise [

42]. Apart from the technical limitations, networked VR also allows for more than one user to interact with the system, raising issues of sociality. The opportunities for social interaction and the dynamics of social interactions within such systems are important elements of networked VR [

43]. Depending on the conditions, users can have low-end, inexpensive devices, like Google Cardboards, or high-end expensive ones, like HTC Vive and Oculus Rift [

42].

Regarding cultural heritage, networked virtual reality is a relatively underexplored field. Very few works focus on the intersection of cultural heritage and networked virtual experiences. Among the few is the work of Park et al. [

44], focusing on the design and implementation of network VR experiences for the Gyeongju VR Theater. The VR Theater was designed and built to serve as a flexible public platform showcasing VR technology as a novel medium for interactive storytelling. It aimed to present diverse artistic expressions and virtual heritage to the public. To realize this, NAVER employed a distributed micro-kernel architecture, which allowed for the integration of 3D virtual spaces with various interfaces and applications.

As far as older individuals are concerned, virtual reality has been studied for its potential to be used in medical and/or entertainment services. Shao and Lee [

45] gathered qualitative and quantitative data from 114 elderly people on their experiences after using a social VR application. The results indicated that the elderly participants perceived social VR as a means of augmenting their social opportunities through entertainment and interaction. Furthermore, they recognized its potential to address medical needs, including teleconferencing and cognitive decline.

Regarding older individuals, cultural heritage, and virtual reality, the field seems to be relatively new and research is not vast. Thus, the present work will focus on collecting content requirements for the design of virtual reality to support the cultural experiences of older people. This is performed within the framework of a research project that wishes to create virtual cultural heritage experiences for older people. The project is called Firefly and is briefly presented below.

2.3. Firefly Project

FIREFLY (fostering virtual heritage experience for elderly,

https://firefly.athenarc.gr/, accessed on 1 February 2025) seeks to design, develop, and assess optimized versions of Extended Reality (XR) applications related to cultural heritage (CH). Current XR applications in this field are primarily aimed at the average user, often focusing on younger individuals or those comfortable with digital interfaces. In contrast, FIREFLY is dedicated to creating interfaces specifically tailored for the elderly, informed by research utilizing Brain–Computer Interface (BCI) technology, unified electroencephalography (EEG), and eye-tracking. The project focuses on intelligent, real-time modeling of cognitive abilities in older adults, aiming to advance how cultural experiences can be enhanced for this demographic. Ultimately, FIREFLY will foster the development of personalized, cognition-centered solutions and significantly push forward the research in cognitive modeling to improve cultural heritage access for the elderly, including those who are healthy or experiencing mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Being in its first year, FIREFLY currently focuses on selecting rich data from the end users and understanding the qualitative differences between older and younger users’ cognitive processing capacities. In this framework, in the present study, FIREFLY focused on studying aspects of content, and in particular, cultural content, to proceed with the formulation of design guidelines for VR cultural environments.

Thus, from all the above, the main research questions of the project and the present study are formed as follows:

What type of images should be used with older individuals in virtual experiences?

How do older people analyze images and what emotions do these images trigger?

Is sentiment analysis and/or expert analysis adequate in predicting the type of emotions that images will trigger in older individuals?

Are there any cognitive alterations when older people interact with historical content presented with the use of technology?

How do older people perceive technologies like AR and VR? Are there any concerns about their use?

3. Method

To answer the above research questions, 21 people over 65 were invited to participate in the study. In the following section, we present the methodology used, following the APA style methodology reporting structure. Therefore, we first present the study participants, then the materials used (i.e., sentiment analysis tool, images used, and film used), and finally, the procedure followed.

3.1. Participants

The Open Care Centers for the Elderly of the Municipality of Patras were contacted for the participation of their members in the study. After discussing with the responsible social workers of the Municipality, explaining the purpose of the study and the methodology to be used, and presenting the ethics approvals and procedures, it was agreed that a group of elders would participate in the study. The social workers explained the need to keep the study duration under 2 to 3 h. On the day of the study (September 2024), 21 people over 65 years of age, all in good health with no or very mild dementia and intact cognitive abilities, came to the premises of the University of Patras, Human–Computer Interaction Lab.

3.2. Sentiment Analysis Web Application

Understanding that creating an engaging cultural venue goes beyond simply arranging exhibits or artworks since it requires a deep understanding of the venue’s purpose and the narrative that unfolds within the space, the University of Peloponnese developed a tool for assessing exhibitions’ potential in triggering specific emotional reactions [

46]. Emotions play a crucial role in how visitors perceive and interpret exhibitions’ messages. According to Norman [

47,

48], emotional responses to objects and environments can influence user experience, which can be applied to cultural experiences.

The Sentiment Analysis Web Application (available at

http://hydra-6.dit.uop.gr:3000, accessed on 1 February 2025) facilitates curators and museum staff to evaluate the emotional design of their collections and itineraries, helping to identify potential flaws and areas for improvement. This can be achieved through modifications such as adjusting descriptive texts, changing exhibit sequences, or revising the set of exhibits included in the collections. It allows curators to define collections and populate them with exhibits. Sentiment analysis is employed to identify the emotions conveyed by the exhibit texts, and the results are visualized at both the exhibit and collection/itinerary levels. The Sentiment Analysis Web Application analyzes content based on 6 primary emotions, namely anger, happiness, sadness, fear, surprise, and disgust, based on Ekman’s Basic Emotions Theory [

49,

50]. In addition, the Sentiment Analysis Web Application also estimates the level of arousal and the emotional intensity following the Circumplex Model of Affect, which categorizes emotions along two dimensions: valence (pleasant vs. unpleasant) and arousal (high vs. low) [

51,

52].

The Sentiment Analysis Web Application was used here to test the emotional aspects of the content that would be presented to the study participants for 3 main reasons:

To make sure a diverse spectrum of emotions is used.

To balance the intensity of the different emotions and have similar intensity of negative and positive emotions during the study phase.

To find the right order of presentation avoiding the concentration of negative or positive emotions together, allowing a sequence of positive and negative emotional experiences throughout the presentation.

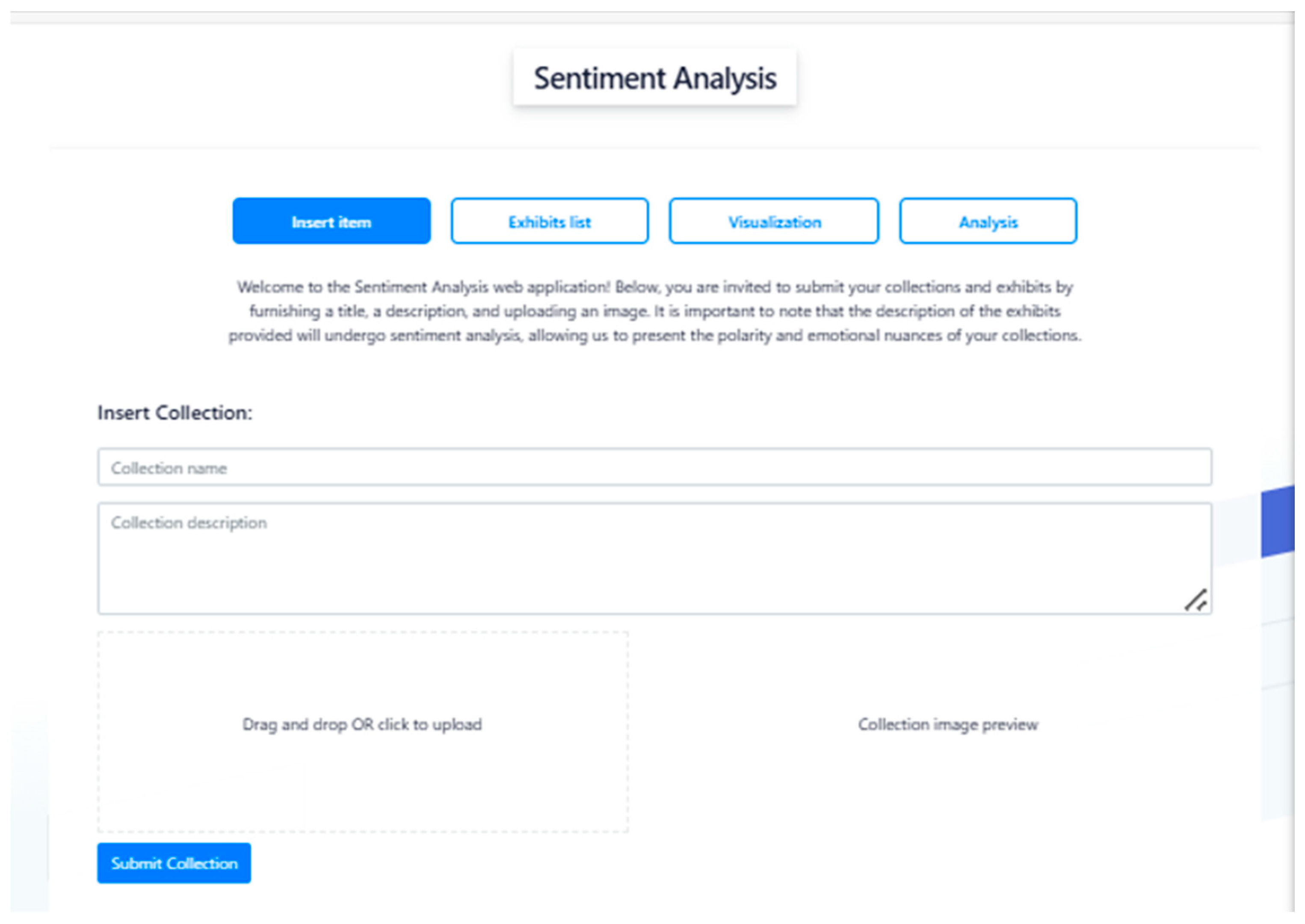

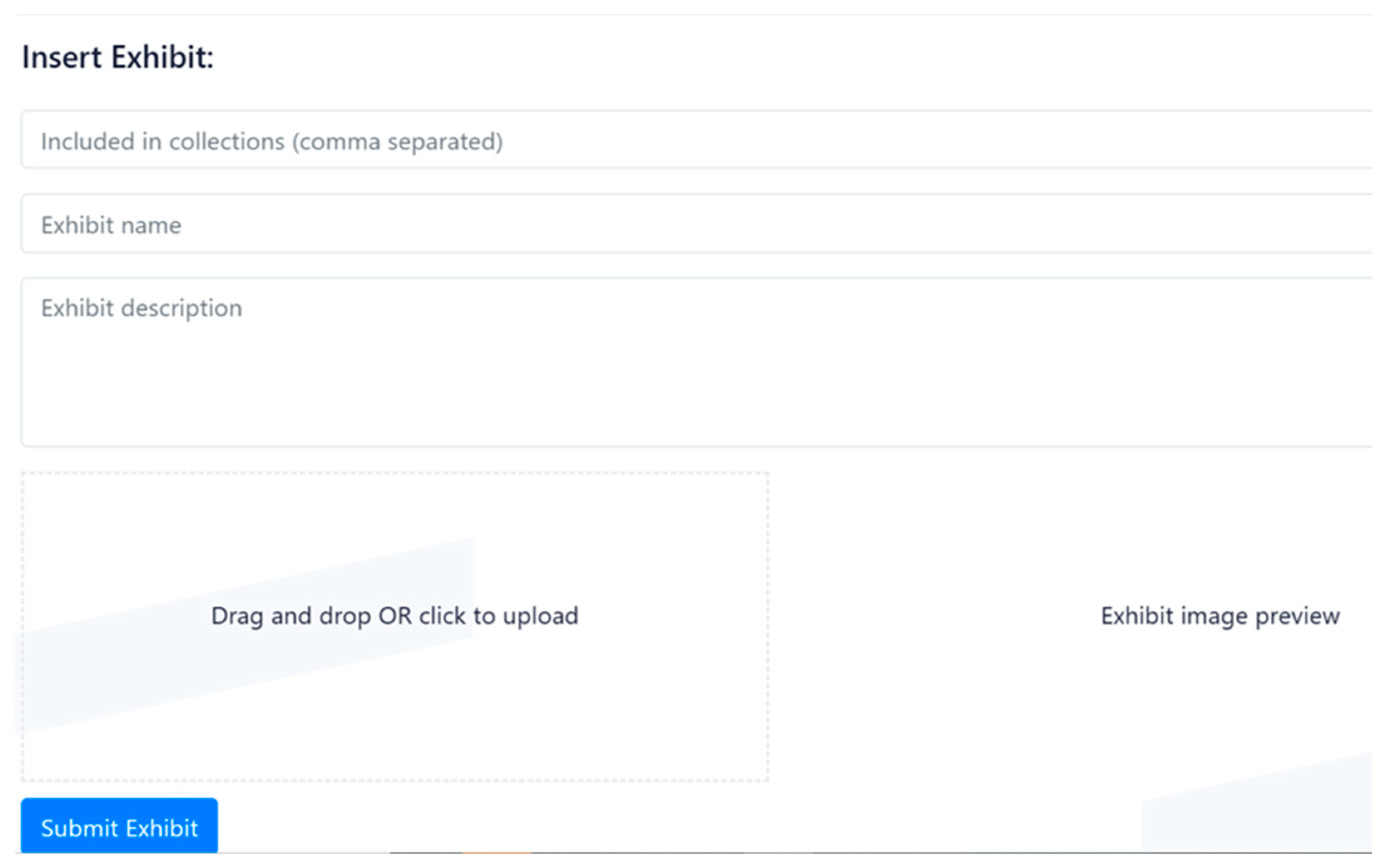

To use the Sentiment Analysis Web Application, one can create collections (

Figure 1) by inserting exhibits (

Figure 2).

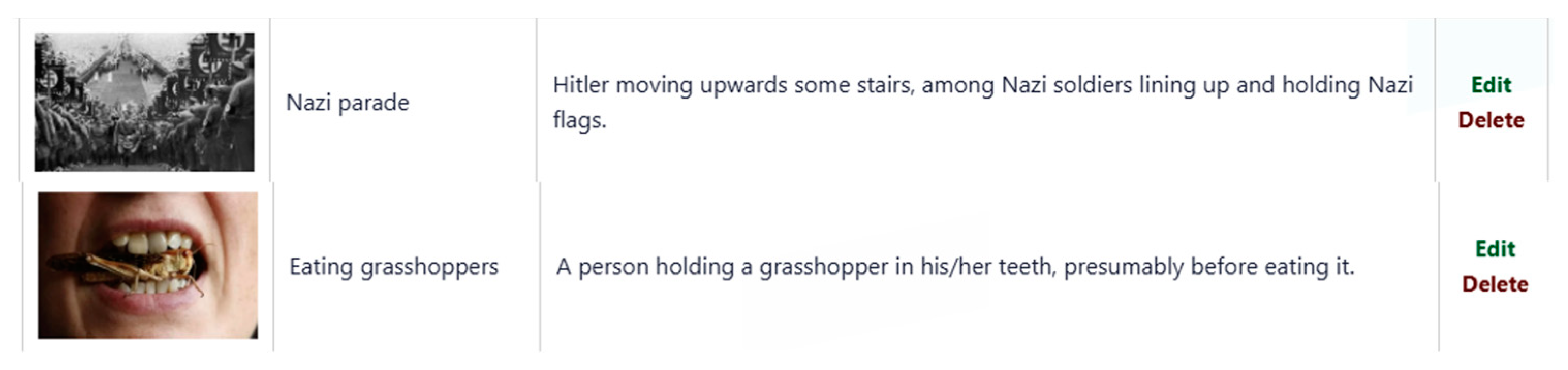

Once images are inserted and collections are made (

Figure 3), the tool analyzes the images and their descriptions.

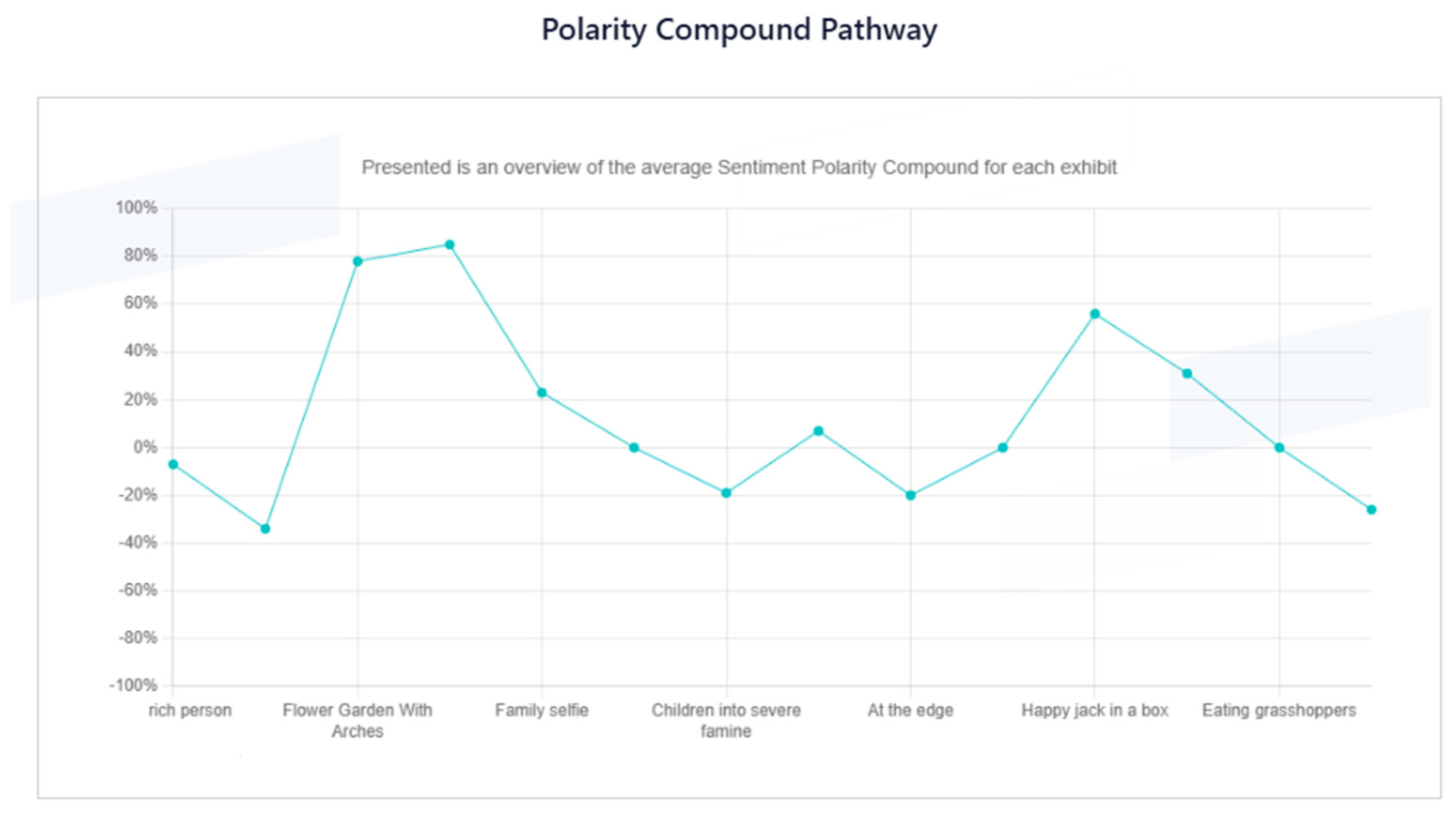

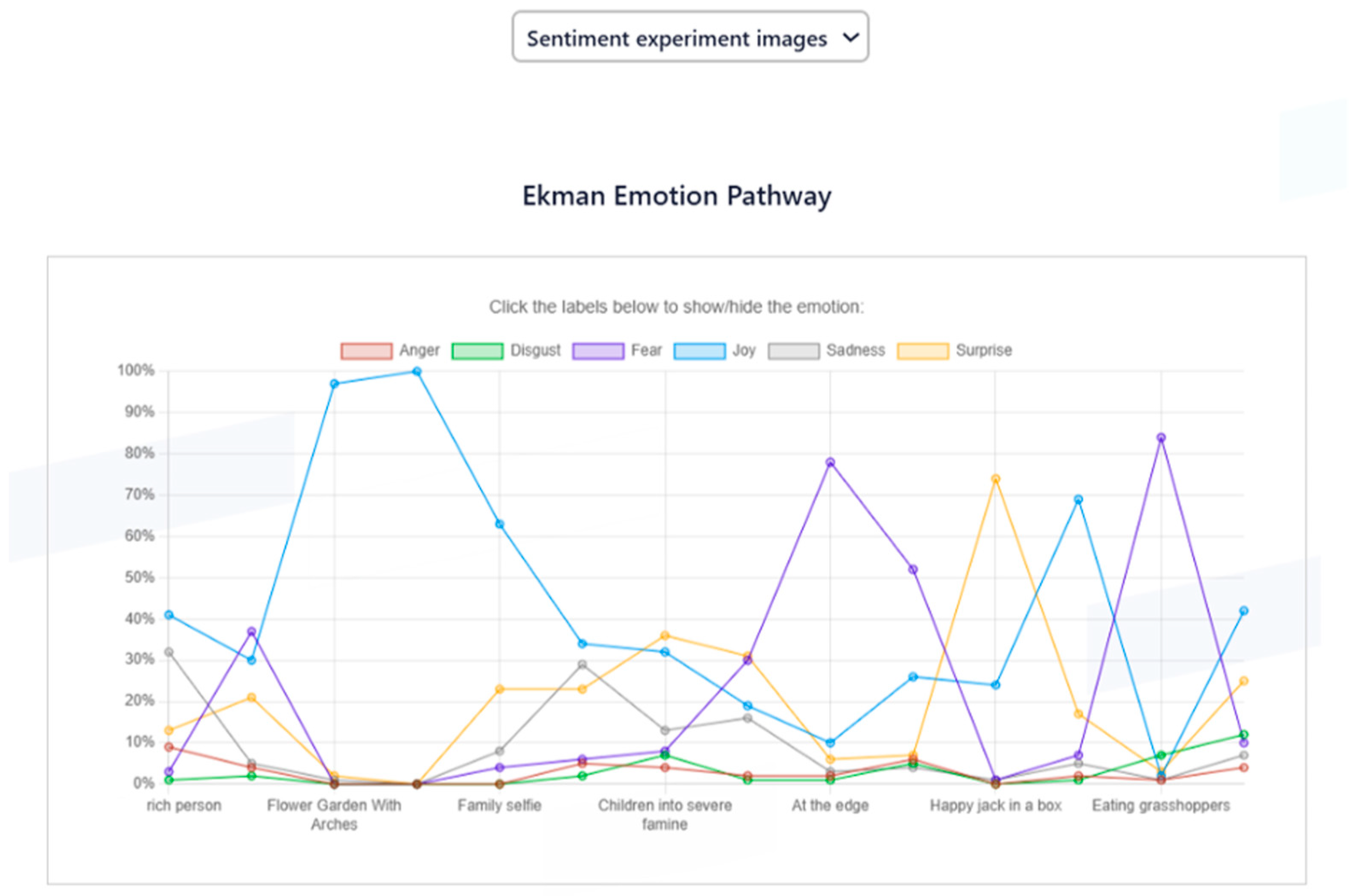

The tool also provides visualizations of the emotions depicted in the images and analyses of the emotion pathways for the entire collection to create a balanced order of presentation regarding the emotional reactions the images will create. For example, the images presented in the current study followed a specific order. As presented in

Figure 4, the polarity analysis of the order of presentation showed that by following this order, positive and negative emotions were spread out and participants would not experience all negative or positive emotions at the same time. Balancing the type of emotional reactions would allow people to recover from possibly strong emotional reactions between images. The presentation order of visual stimuli is crucial and should be considered, as past research has shown the impact of stimulus presentation order on working memory [

49,

50]. Therefore, the Sentiment Analysis Web Application allows the visualization of the emotion pathway in specific presentation orders (

Figure 5), which helped researchers decide on the presentation order.

3.3. Choice of Images

A set of images was chosen by a team of experts, including a psychologist and a museum specialist, using the Basic Emotions Theory [

51,

52], representing basic emotions like anger, happiness, sadness, fear, surprise, and disgust since these emotions seem to be globally recognized and expressed. In addition, these emotions are a combination of positive and negative ones as they are recognized as the primary emotion categories from the Circumplex Model of Affect [

53,

54].

Overall, 14 images were used. The descriptions of the images are shown in

Table 1 in the order of presentation (the actual images are not presented due to copyright issues).

Table 1 also describes the main emotion found after the sentiment analysis of the images and the main emotions expected by the psychologist of the study.

The images were used as input in the Sentiment Analysis Web Application to ensure the presentation of a diverse spectrum of emotions. The analysis showed that, indeed, the images chosen could provoke all 6 basic emotions, as shown in

Figure 5.

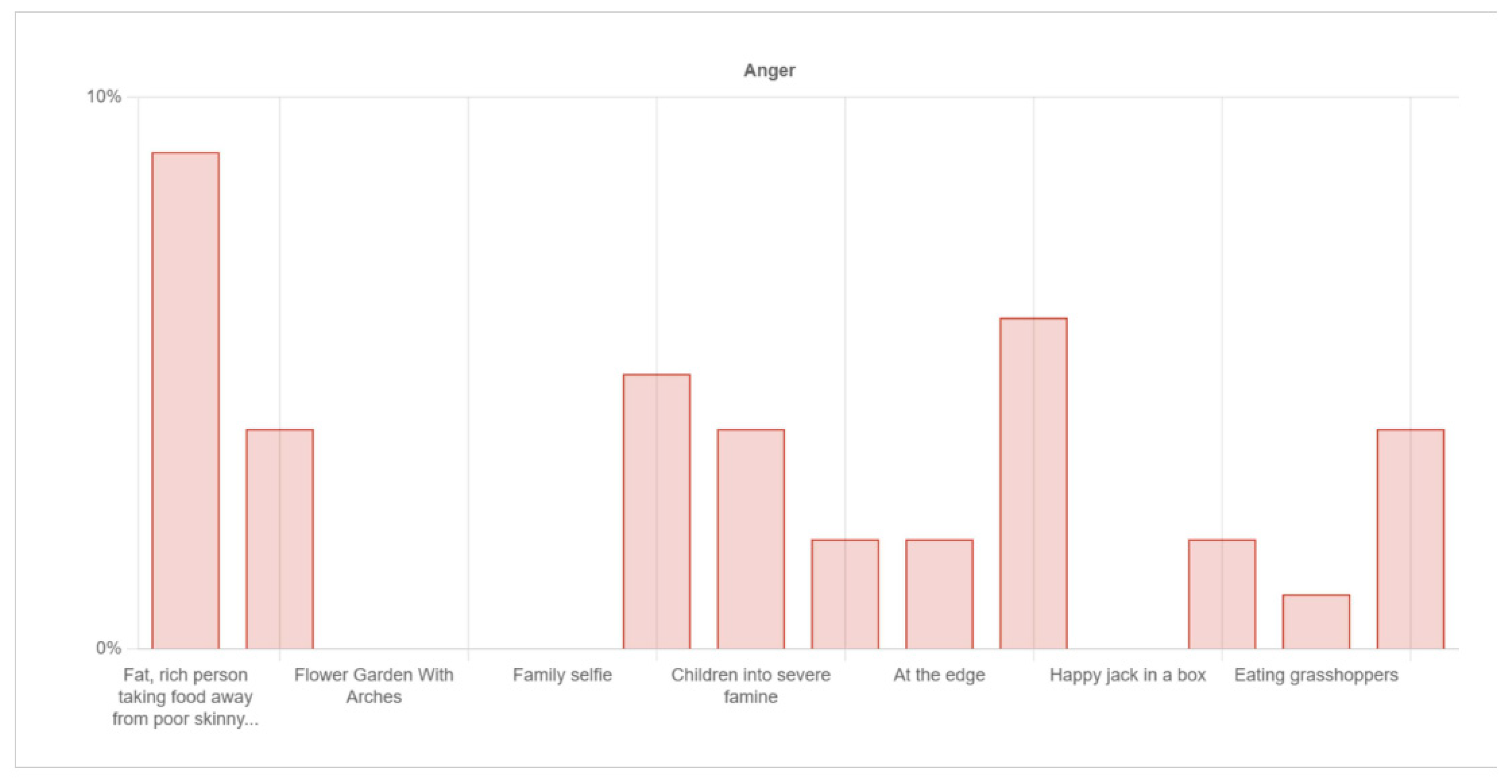

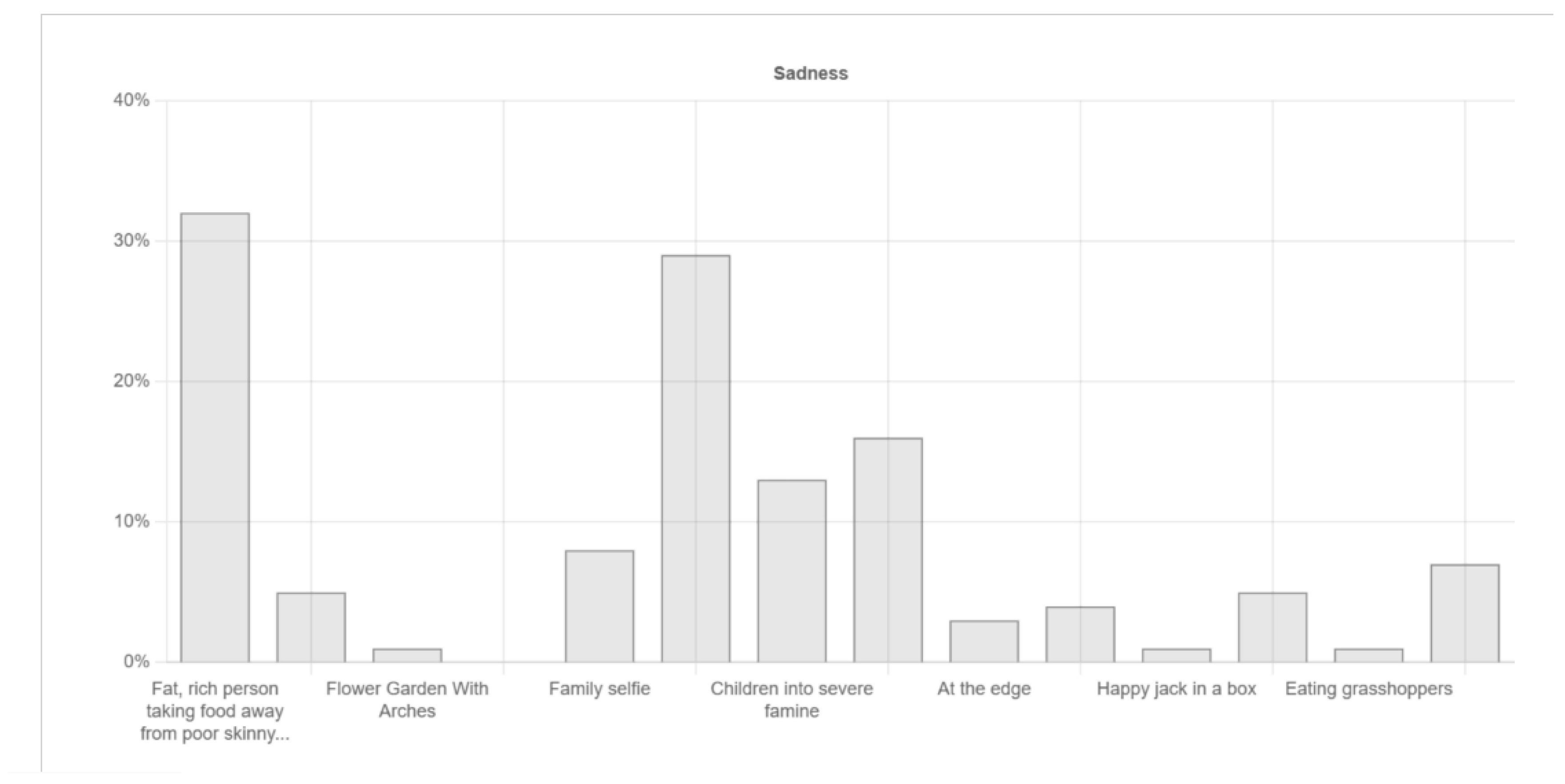

Testing the intensity of the emotions provoked, the Sentiment Analysis Web Application showed that there is adequate fluctuation of emotions.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show examples of the intensity of emotions for the different images.

Testing the order of presentation, the Sentiment Analysis Web Application showed that the order of the presentation of the images maintains a balance between negative and positive images and spreads them throughout the presentation (

Figure 4).

3.4. Choice of Film

The short film “As a letter to memory” by Michalis Manoussakis was chosen for the reasons below:

The short duration of the film is ten (10) minutes.

The topic of the film presents the story of a woman (the grandmother of the film’s creator) forced to leave her home after the end of the Greco-Turkish war of 1922 and the refugee crisis that followed. This topic was chosen since many participants are of refugee origin or have lived next to Asia Minor refugees and they are therefore involved directly with the events presented in the short film.

The film, created for the exhibition Topoi Atopoi tis Anatolis (translation: Places Un-places of the East) at the Municipal Art Gallery of Thessaloniki, Greece in 2022, 100 years after the Asia Minor Catastrophe, offers a heartfelt tribute to those who lived through it. It reflects on themes of displacement, memory, and identity, resonating deeply with the tragic events that happened in Asia Minor in 1922. This catastrophe profoundly reshaped the cultural and historical landscape of Greece and the wider region, emphasizing the profound sense of dislocation experienced by those who were exiled from their ancestral homes. The Asia Minor Catastrophe was not merely a historical event; it was a cultural and human rupture, leaving thousands of families without a sense of place or belonging. For those who survived, their “topoi”—their homes, communities, and way of life—became “atopoi”, unrecognizable or completely lost.

The film captures the emotional and historical weight by intertwining personal narratives. “As a letter to memory” is more than a film—it is a deeply personal and moving story that invites viewers to connect with history on an emotional level. At its heart is Michalis Manoussakis, sharing the life of his grandmother—a story filled with hardship, resilience, and love, reflecting cultural trauma. As he speaks, her world comes alive through historical photographs, drawings of her family, and a soundtrack of nostalgic music as a musical carpet. These elements come together to create something special—a story that feels both intimate and universal. The film also draws us to the sea—a powerful, ever-present force that shapes lives. It connects people and cultures while, at the same time, creating distances that can feel insurmountable. Yet, it also brings peace, its soothing waves stirring memories and offering space to reflect. The sea is not just part of the story; it feels like a character itself, carrying the weight of emotions and history. This film is not just something to watch—it is something to feel, a reminder of the strength it takes to hold onto hope and memory, that deepens the understanding of the catastrophic loss of life and heritage while honoring the enduring spirit of those who survived.

3.5. Procedure

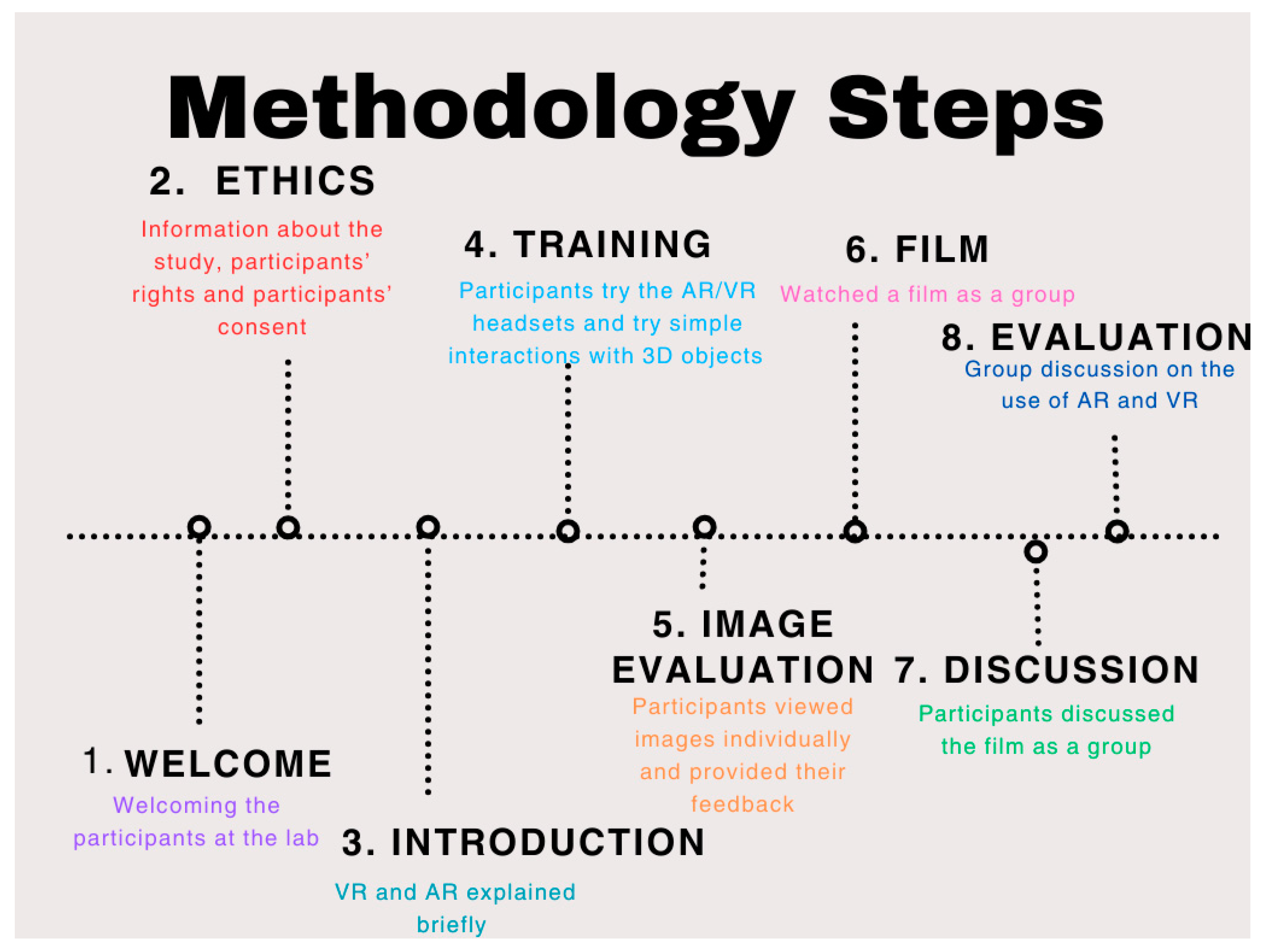

The procedure followed is presented in

Figure 8.

3.5.1. Introducing VR Headsets (Phase 1)

After welcoming the participants to the lab and completing ethics requirements (information about the study, participants’ rights, and participants’ consent), a researcher explained briefly what virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) is and presented virtual and augmented reality headsets. The participants also watched a short film about the use of VR and AR in cultural heritage spaces.

Then, the participants who wanted to try the headsets were assisted with their use until they felt confident enough to proceed on their own. It is interesting to note that 20 people tried the headset out of a total of 21. Only one lady explained privately to the researchers that she was wearing a wig, and she did not want others to know about it. For this reason, she did not want to risk using the headset.

3.5.2. Reviewing Images (Phase 2)

After the training session was completed, participants viewed the chosen set of images individually and they were asked to describe what they saw and how they felt. Only 12 individuals out of 21 participated in this phase due to time restrictions. At a preparatory meeting between the researchers and social workers, social workers explained that when working with people over 65, one needs to respect a strict timetable, and activities cannot exceed 3 h. As phase 2 was evolving, researchers also noticed that each participant needed a lot more time than expected since participants wanted to discuss images in detail and make connections to their personal experiences.

3.5.3. Watching a Film (Phase 3)

After a short coffee break, a researcher introduced the short film that would follow. After the participants watched the film, a discussion followed based on the questions below:

What did you like and dislike about the film?

What else would you add to the film?

If you felt strong emotions watching the film, at what point did this happen?

Should the film be more or less emotionally intense?

Could technology help you transfer your knowledge and experiences to younger generations?

4. Results

4.1. Results from Phase 2

The first image, showing two people sitting at a table and the rich person eating the food of the poor person, and the second, showing a forest on fire, were shown together since the experts in the team predicted that the two together would evoke the feeling of anger. However, the sentiment analysis predicted people experiencing sadness when looking at these images. During the study, most participants expressed negative emotions, like sadness (eight participants) and fear (two participants), but anger was mentioned only by one participant. P12 mentioned: “(I feel) anger…greed…He has no feeling. He is indifferent”. Another participant mentioned that she remembered being a child in the countryside and she had to be disciplined at the table. The participant did not elaborate further on that; however, the main emotions seem to be related to discipline and have negative connotations.

Images 3, 4, and 5 were shown together since experts and sentiment analysis predicted that the main emotion would be joy. In fact, all 12 participants mentioned that they felt happy looking at the images. Three participants also mentioned that these images brought back memories of happy family times, and one felt nostalgic. P7 mentioned that “I was also a baby and then I grew up and made my family…memories. I feel nice”. P10 mentioned that she feels optimistic, and P12 mentioned that he feels “a sweet calmness…I take courage for the life we live…I remember gathering the family”.

Images 6 and 7 were shown together since experts expected people to feel sad by watching them. However, the sentiment analysis predicted (wrongly) 34% joy for one image and 51% surprise for the second. All participants mentioned that they experienced negative emotions and most mentioned sadness as being the main emotion in these images. P6 called it “absolute sadness”, while P8 reported “helplessness”, P2 reported “pessimism”, and P9 stated “horror”. P12 mentioned that he felt sadness and anger looking at these images. Two participants said that they felt like crying (P12 and P3).

Images 8, 9, and 10 were presented together since both experts and sentiment analysis predicted fear as the dominant emotion. Again, most of the participants (8 out of 12) mentioned fear as the main emotion. Three participants mentioned that they felt sad (P6, 7, and 10) and two mentioned that they felt very worried (P10, 11). P11 said “He wants to commit suicide. I feel something bad will happen” referring to the image of a person standing at the edge of a rooftop. Interestingly, for the same image, two participants mentioned “my time has passed. I sit (on the edge) and I walk slowly” (P7), “My mind hangs between yesterday and today” (P9). It seems that both participants made connections between the image of a person at the edge of their life and the end getting closer. Therefore, all participants reported negative emotions.

Images 11 and 12 were presented together since experts predicted people to experience surprise. The sentiment analysis predicted the emotion of surprise for one of the two images and joy for the other. Participants seem to agree with the sentiment analysis since 9 out of 12 reported feeling joy. One participant (P1) did not mention feeling any emotion.

Images 13 and 14 were presented together since experts predicted people to feel disgust. However, sentiment analysis predicted fear for image 11 and surprise for image 12. Again, the majority of the participants seemed to agree with the experts, and 9 out of 12 reported disgust as the main emotion. P1 mentioned that he felt unpleasant without elaborating more. Creepiness was mentioned by P2 and P4. P6 mentioned she felt anger because the person in the image ate the grasshopper.

Table 2 summarizes the findings.

4.2. Results from Phase 3

After watching the short video, a group discussion followed. To analyze the data collected through this group discussion, the taxonomy proposed by Soren [

55] was used. This taxonomy specifically identifies cognitive alterations that individuals experience when encountering culturally significant content. People may describe these alterations as:

Novel understanding.

A sense of infinity or lasting phenomena.

Experiences connected to original objects.

Intense emotional experiences.

Unexpected sensory perceptions.

The potential for motivation to engage further with cultural content.

The dimensions of the taxonomy were clearly observed and recorded during the group discussion. More specifically, participants showed signs of novel understanding. One participant mentioned that her grandparents rarely talked about their hardships after leaving Asia Minor, and it is only now that she understands what they went through. As a participant characteristically mentioned, “I just now learnt the history…now that I am 75”. In addition, while most Greek people would be familiar with the Greek side of the war and the events, believing that Greek populations were the only victims of this war, in the video, the Turkish side was also presented, explaining that regardless of who is winning or losing a war, everyone has lost since the suffering is for all involved sides. In this light, one participant mentioned that he would like to see “the bad things the Greek Army did in Asia Minor” showing a novel understanding of the historical events. As another participant explained, he realized that the Greek state did not receive the refugees well and they were mistreated. In particular, he said, “I want to know what Greece did NOT do for these people” and explained that he knew of things that the Greek state did with the refugees but he now wanted to know all the things that the Greek state should have done.

During the discussion, many participants seemed to notice similarities between the events of 1922–1923 and the refugee crisis that followed, mentioning similarities with today’s world. Although none explicitly stated that phenomena like this are lasting, their comments often implied that there was a realization and understanding that human societies always face problems like war, forced population movement, immigration, etc. As one participant mentioned, “It is always the poor that are affected the most”, and another one said, “Human life does not seem to be worth a lot”, connecting events of the past and the present.

The story presented to the participants through the video was the real-life story of an older woman. Many participants shared their family’s stories and spotted the many similarities in the lives of refugees. One participant mentioned, “The video told the truth!”. Although their experience was not connected to original objects, it was nevertheless connected to original events, and participants had a clear understanding of that.

While watching the film and during the discussion that followed, most participants showed clear signs of emotional engagement. They explicitly mentioned emotions they experienced like anger, sadness, or melancholy. They also said that they were deeply moved by the story and that it brought back memories from their families. The emotional arousal that was caused by the video seemed to trigger certain episodic memory processes since many personal stories emerged and were shared in the group. Most stories included memories from the lives of refugees as they remembered and experienced them. These stories also carried a rich emotional load (stories of poverty, exclusion, segregation, etc.).

Regarding unexpected sensory perceptions, most participants mentioned the aesthetics of the video as unexpected since the video used drawings of people and locations and not photos. As one participant mentioned when referring to one drawing in the video: “The grandmother sitting in the chair had a haunting gaze...it told her whole story”.

During the session, researchers also observed increased motivation to participate in similar cultural activities in the future as was expressed both by participants and the accompanying social workers. The participants also mentioned that they would like to use technology again for their cultural experiences. One person said “I would like to see places I have not been with these glasses”, showing a positive attitude toward AR and VR technologies, as well as the motivation to engage further in the future.

4.3. Important Observations

During the interaction with the study participants, there were some important observations that could significantly affect the VR experiences designed for this age group, as discussed below:

The initial planning of the different phases of the study regarding time was not followed because participants needed significantly more time for each activity than younger adults would. Although the time spent on the activities was not measured nor compared against younger individuals’ activity completion times, based on the involved researchers’ past experience, there are potentially significant time delays for this age group. There seem to be two main reasons for this. The first reason is that reaction times for the different stimuli are slower compared to younger people. The second reason is that for most stimuli, participants recollected an event from their lives that they wanted to share with the researchers. Therefore, although it was originally planned to collect data from 21 individuals, there was time for only 12 people to view the images and state their emotions.

While viewing new cultural content, participants seem to process information in a serial manner and not as a whole. That was observed in most cases when the participants saw a new image. The way they described the images was by discussing different parts of the image, one after the other. Only a couple of participants described the image as a whole or performed parallel processing. In addition, many details of the images were neglected, even if they were important for understanding. For example, regarding the image showing a gigantic nail polish bottle hanging in the air, all participants talked about the dimensions of the bottle and not the fact that it was defying gravity.

The technologies presented to the participants (AR and VR) seemed to have a very high novelty effect since there were strong emotional reactions, spanning from enthusiasm to hesitation. A few individuals were hesitant toward this type of technology and the use of VR and AR glasses, either for practical issues (e.g., if such technology would interfere with hearing aids, if the glasses could remove a wig, etc.) or because they felt insecure about their abilities in using technologies. In addition, participants seemed very reluctant to touch and handle the equipment for fear of doing something wrong. With the help of the researchers, the participants felt confident enough to try the equipment. This observation raises questions regarding the autonomy of older adults with the use of VR and AR technologies. In the scenario of remote access, older adults might avoid using such technologies alone. Issues of technology acceptance are therefore crucial. Thus, issues of technology acceptance and motivation for use are very important when VR experiences are designed for older adults.

Many participants expressed an increased concern about history and how it is taught to younger generations. The realization that cultural content is not easy to approach and the need to provide multiple views on historical phenomena seemed to concern participants. A fear of the potential for unethical uses of VR and AR technologies was expressed often during the study session. Finally, one participant asked the researchers about the funding of the study and its goals and requested a report with a summary of our findings. In addition, many participants expressed their hope that researchers around the world will use AR and VR following ethical principles, and they mentioned that images (offered through VR) are a powerful medium. Finally, one participant reflected further on the framework of the use of such technologies: “The content (of VR) should be created with emotion and honesty, leaving aside political agendas... and with moderation so that we don’t become slaves to technology... and avoid overloading our minds with images, leaving them empty”.

5. Threats to Validity

The present work is an observational study wishing to inform the design of virtual cultural experiences for the elderly. There are a few limitations with the methodology followed that should be mentioned here, together with possible mitigation efforts. First, the present study cannot create generalizable results due to the limited sample size. In fact, elders from an Open Care Center were invited, implying that people in relatively good health were involved since elders in Open Care Centers go to the Center on their own daily. In addition, and due to the nature of the observational study, there was no control group in the present work. In a future study, an experiment could be set up where some people use new technologies to engage with historical and cultural content and others do not use technology. In an observational study, like the one described here, the Hawthorne effect is also present, implying that there might be biases when people know they are observed. To minimize the effect, during data collection in phase 2, participants were interviewed in a separate room by only one researcher, while the other researchers waited outside. However, the effect remains in such a research setup. In a future study, data could be collected by an application that would record the responses of the participants without the presence of a researcher (although interaction without human presence might feel strange for people in this age group). Another important issue is the selection of images to be presented, their presentation order, and the choice of film. Different images in different presentation orders and a different film might produce different results. Furthermore, the questions used to collect data were open-ended to produce rich qualitative data, but at the same time, they also introduce significant variability, making it difficult at times to quantify the responses. In a qualitative study like this one and analysis of qualitative data, there are also researcher interpretation biases since our preconceptions and expectations might influence the analysis, even though the involved researchers are highly experienced in qualitative research. To balance these biases, future works could use different types of films and images and possibly create/use a taxonomy of images and films with specific characteristics. Finally, during the group discussion phase, the group dynamics might also bias the results, although a group discussion is made for recording group results and does not treat responses as individuals. In addition, the results were not only collected from the group phase but also from phase 2 where participants viewed content on their own and provided responses individually. Overall, the present work presents a first attempt to engage elders with cultural content using cutting-edge technology and, as such, provides the first understanding of possible factors that affect such interactions. Hopefully, future work can build on the present findings and proceed with methodologies that provide more generalizable results.

6. Conclusions

The current study showed that experts’ expectations do not always match the sentiment analysis or the participants’ answers. Although there are cases where there is complete agreement between experts, sentiment analysis, and participants, there are also cases where the dominant emotion was not easy to predict. Having said that, in all cases, the experts and the participants agreed on whether the experience was predominantly positive or negative. More specifically, there were 6 images (out of 14) that the participants, experts, and algorithms agreed on regarding the main emotion depicted. Participants agreed with the sentiment analysis tool 8 times (8 images out of 14). Participants agreed with the experts 10 times (10 images out of 14). Trying to further understand these discrepancies and the reasons for occurring, we believe that two elements might be important: 1. algorithms in the sentiment analysis tool are trained by younger people; 2. algorithms in the sentiment analysis tool are trained by computer experts and not social sciences experts. Of course, the sample in the current study does not allow further speculation on the matter since it was not the scope of the present work to validate the sentiment analysis tool with the input of older individuals, but it was used to find the right images for the experiment that covered a vast spectrum of emotions. A future study could study this issue in detail.

To create meaningful and inclusive experiences in virtual reality for people of all ages, including people over 65, it is important to focus on issues of content design, as well as technology design. Content development for VR is demanding and requires resources, making it essential to design it following accessibility guidelines, including physical, emotional, and cognitive accessibility. The present work allowed participants to participate in experiences that evoked emotions and engage in group discussions on historical events, also building on past research [

35,

36].

This age group seems to be hesitant with the use of technology either because they believe they lack technical skills or because they are skeptical overall about the use of novel technologies. As mentioned above, issues of ethics emerged frequently during the data collection session. Even if using technology acceptance models is important with all types of users, with this age group, it is essential. The current study moved beyond the existing literature, which has provided data on younger individuals [

17], and showed clear differences in the technology acceptance between older and younger users of VR.

Regarding content requirements, designers should avoid unnecessary details in the material used for VR and AR content since there seem to be cognitive capacity limitations and a slower processing speed. Dark colors seem to trigger negative emotional reactions, and in fact, this was mentioned by most participants when the images were analyzed. Cultural content should provide connections to personal experiences and allow room for the recollection of personal memories and reflection. As they also mentioned, “

as the end of life is getting closer, we need to feel optimistic about the future”. Considering this aspect, cultural content needs to include elements of hope and triggers of positive emotional reactions. The current study builds on previous works [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32] that recognized cognitive limitations in people over 65. In fact, we also observed cognitive capacity limitations and slower processing speed of older individuals when they analyzed the images presented to them.

Regarding hardware requirements, VR applications for older adults could be offered in a simple form, e.g., desktop applications, VR cardboards, etc., that is more accessible and cheaper without being intimidating for older adults (not being afraid to destroy the equipment). In addition, heavy head-mounted equipment cannot be easily used with this age group due to its weight but also because it might affect the location and function of hearing aids, vision glasses, etc. It is better to have something to hold like VR cardboard than something to wear like headsets. The current study did not focus on the social potential of VR cultural experiences for the elderly. Considering the slower and serial processing time of older individuals, future works need to focus on studying the balance needed between providing opportunities for socialization through networked VR and keeping cognitive load to a manageable level for people of that age. Although previous works [

42] found that, depending on the conditions, users can have low-end devices or high-end ones, the present study argues for the use of low-end devices like desktop applications and VR cardboards for people over 65 due to usability issues raised during data collection.

Finally, regarding procedure requirements for future studies, when working with older people, one needs to allow more time for all processes, including the use of technology. All activities should have a duration of 2 to 3 h with sitting arrangements, and bathrooms should be also close by as most participants explained their importance. In this light, the possibility of having VR experiences from home seems very important if the experience is designed according to older adults’ needs for comfort.

Therefore, regarding the design of VR experiences for the elderly, a few guidelines emerged, such as:

Involving older individuals in participatory design processes and following accessibility and usability guidelines for content and technology development.

Applying technology acceptance models since older individuals are particularly skeptical of the use of new technologies.

Using simple graphics and simple images and avoiding unnecessary details and purely decorative elements.

Avoiding dark colors.

Including positive messages and messages of hope in the VR experiences.

Avoiding the use of head-mounted displays and heavy headsets. VR cardboards and/or desktop applications are preferable.

Allowing plenty of time for the experiences and making sure there are sitting arrangements and frequent breaks.

Creating opportunities for social interactions in VR worlds.

The research team will continue working with elders and VR cultural experiences. In particular, the next set of studies will focus on collecting physiological data from elders when exposed to VR cultural experiences, like brain waves. In addition, eye-tracking technology will be also used to study further the findings of the current study regarding the serial processing of image details. In addition, the sentiment analysis tool will be used to further extract participants’ affective profiles. The affective profiles will be used to create balanced group interactions since people with similar affective profiles seem to create better social interactions [

56].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and S.S.; methodology, A.A.; software, C.V. and G.K. (Georgios Kantianis); validation, A.A. and C.V.; formal analysis, A.A.; investigation, A.A., C.V. and S.S.; resources, A.A., C.V., G.K. (George Kolokithas) and S.S.; data curation, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A. and C.V.; visualization, A.A.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, S.S. and G.K. (George Kolokithas); funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research project is implemented in the framework of H.F.R.I called “Basic research Financing (Horizontal support of all Sciences)” under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan “Greece 2.0” funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU (FIREFLY-Fostering vIrtual heRitage Experience For eLderlY, H.F.R.I. Project Number: 15497).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of International Hellenic University (protocol code 88/2024) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Sentiment Analysis data can be found at

http://hydra-6.dit.uop.gr:3000/list (accessed on 1 February 2025). The datasets from the study participants are not readily available because of Ethics requirements. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the study participants for a unique and memorable data collection session and their accompanying nurse from the Municipality of Patras (Greece), Plota, for organizing the transportation of the elders and providing valuable knowledge for the management of the workshop.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bloom, D.E.; Boersch-Supan, A.; McGee, P.; Seike, A. Population aging: Facts, challenges, and responses. Benefits Compens. Int. 2011, 41, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, M.E.; Rejeski, W.J.; Blair, S.N.; Duncan, P.W.; Judge, J.O.; King, A.C.; Macera, C.A.; Castaneda-Sceppa, C. Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007, 116, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares Pereira, G.; Silva Nunes, M.V.; Alzola, P.; Contador, I. Cognitive reserve and brain maintenance in aging and dementia: An integrative review. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2022, 29, 1615–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karst, K.L. Paths to belonging: The constitution and cultural identity. NCL Rev. 1985, 64, 303. [Google Scholar]

- Shackel, P.A. Pursuing heritage, engaging communities. Hist. Archaeol. 2011, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfa-Lobato, L.; Guàrdia-Olmos, J.; Feliu-Torruella, M. Benefits of cultural activities on people with cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 762392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Why Culture and Education? Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/about-culture-education (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Cominelli, F.; Greffe, X. Intangible cultural heritage: Safeguarding for creativity. City Cult. Soc. 2012, 3, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, U.; Robertson, K.; Aitken, R. Experience, emotion, and eudaimonia: A consideration of tourist experiences and well-being. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, M.K.; Pierdicca, R.; Frontoni, E.; Malinverni, E.S.; Gain, J. A survey of augmented, virtual, and mixed reality for cultural heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2018, 11, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H.T.; Lim, C.K.; Rafi, A.; Tan, K.L.; Mokhtar, M. Comprehensive systematic review on virtual reality for cultural heritage practices: Coherent taxonomy and motivations. Multimed. Syst. 2022, 28, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škola, F.; Rizvić, S.; Cozza, M.; Barbieri, L.; Bruno, F.; Skarlatos, D.; Liarokapis, F. Virtual reality with 360-video storytelling in cultural heritage: Study of presence, engagement, and immersion. Sensors 2020, 20, 5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagud, M.; Orero, P.; Matamala, A. Culture 4 all: Accessibility-enabled cultural experiences through immersive VR360 content. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2020, 24, 887–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, F.; Bolognesi, C.M. Virtual reality for cultural heritage: New levels of computer-generated simulation of a unesco world heritage site. In From Building Information Modelling to Mixed Reality; Bolognesi, C., Villa, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, A. Mixed Cultural Visits or What COVID-19 Taught Us. Computers 2023, 12, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katifori, A.; Antoniou, A.; Damala, A.; Raftopoulou, P. Editorial for the special issue “advanced technologies in digitizing cultural heritage”. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch’Ng, E.; Li, Y.; Cai, S.; Leow, F.T. The effects of VR environments on the acceptance, experience, and expectations of cultural heritage learning. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2020, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Lucia, M.D.; Campana, S.; Magnelli, A. Innovating the cultural heritage museum service model through virtual reality and augmented reality: The effects on the overall visitor experience and satisfaction. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paolis, L.T.; Chiarello, S.; Gatto, C.; Liaci, S.; De Luca, V. Virtual reality for the enhancement of cultural tangible and intangible heritage: The case study of the Castle of Corsano. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2022, 27, e00238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmanović, E.; Rizvic, S.; Harvey, C.; Boskovic, D.; Hulusic, V.; Chahin, M.; Sljivo, S. Improving accessibility to intangible cultural heritage preservation using virtual reality. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2020, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulos, A.; Antoniou, A. VR games in cultural heritage: A systematic review of the emerging fields of virtual reality and culture games. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulusic, V.; Gusia, L.; Luci, N.; Smith, M. Tangible user interfaces for enhancing user experience of virtual reality cultural heritage applications for utilization in educational environment. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2023, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H. The application of virtual reality technology in the digital preservation of cultural heritage. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2021, 18, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H.T.; Lim, C.K.; Ahmed, M.F.; Tan, K.L.; Mokhtar, M.B. Virtual reality usability and accessibility for cultural heritage practices: Challenges mapping and recommendations. Electronics 2021, 10, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniack, E.P. Not just fun and games: Applications of virtual reality in the identification and rehabilitation of cognitive disorders of the elderly. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2011, 6, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, J.S.C.D.; Leite, R.C.; Brizola, R.; Yonamine, C.Y. Virtual reality therapy for rehabilitation of balance in the elderly: A systematic review and META-analysis. Adv. Rheumatol. 2019, 58, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.C.M.; Andringa, G. The potential of immersive virtual reality for cognitive training in elderly. Gerontology 2020, 66, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Betances, R.I.; Jiménez-Mixco, V.; Arredondo, M.T.; Cabrera-Umpiérrez, M.F. Using virtual reality for cognitive training of the elderly. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement.® 2015, 30, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, E.D.; Schoene, D.; Pichierri, G.; Smith, S.T. Use of virtual reality technique for the training of motor control in the elderly: Some theoretical considerations. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2010, 43, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamińska, M.S.; Miller, A.; Rotter, I.; Szylińska, A.; Grochans, E. The effectiveness of virtual reality training in reducing the risk of falls among elderly people. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 2329–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeng, M.Y.; Pai, F.Y.; Yeh, T.M. The virtual reality leisure activities experience on elderly people. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2017, 12, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsangidou, M.; Solomou, T.; Frangoudes, F.; Ioannou, K.; Theofanous, P.; Papayianni, E.; Pattichis, C.S. Affective out-world experience via virtual reality for older adults living with mild cognitive impairments or mild dementia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.X.; Lee, C.; Lally, D.; Coughlin, J.F. Impact of virtual reality (VR) experience on older adults’ well-being. In Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Applications in Health, Assistance, and Entertainment, Proceedings of the 4th International Conference, ITAP 2018, Held as Part of HCI International 2018, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 15–20 July 2018; Zhou, J., Salvendy, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Part II 4; pp. 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Syed-Abdul, S.; Malwade, S.; Nursetyo, A.A.; Sood, M.; Bhatia, M.; Barsasella, D.; Liu, M.F.; Chang, C.C.; Srinivasan, K.; Li, Y.C.J. Virtual reality among the elderly: A usefulness and acceptance study from Taiwan. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, H.; Vreeland, S.; Noble, G. Museopathy: Exploring the healing potential of handling museum objects. Mus. Soc. 2009, 7, 164–177. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, L.J.; Chatterjee, H.J. Well-being with objects: Evaluating a museum object-handling intervention for older adults in health care settings. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2016, 35, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldmeijer, L.; Wartena, B.; Terlouw, G.; van’t Veer, J. Reframing loneliness through the design of a virtual reality reminiscence artefact for older adults. Des. Health 2020, 4, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Kannan, R.J.; Ramanathan, S. Multi-user networked framework for virtual reality platform. In Proceedings of the 2017 Proceedings of the 14th IEEE Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 8–11 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oriti, D.; Manuri, F.; Pace, F.D.; Sanna, A. Harmonize: A shared environment for extended immersive entertainment. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 3259–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, J.; Xie, D. Networked vr: State of the art, solutions, and challenges. Electronics 2021, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Vega, M.; Liaskos, C.; Abadal, S.; Papapetrou, E.; Jain, A.; Mouhouche, B.; Kalem, G.; Ergüt, S.; Mach, M.; Sabol, T.; et al. Immersive interconnected virtual and augmented reality: A 5G and IoT perspective. J. Netw. Syst. Manag. 2020, 28, 796–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, V.; Simiscuka, A.A.; O’Connor, N.; Muntean, G.M. Performance evaluation of a multi-user virtual reality platform. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC), Limassol, Cyprus, 15–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, R. Networked Worlds: Social Aspects of Multi-User Virtual Reality Technology. Sociol. Res. Online 1997, 2, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Ko, H.; Kim, T. NAVER: Networked and Augmented Virtual Environment aRchitecture; design and implementation of VR framework for Gyeongju VR Theater. Comput. Graph. 2023, 27, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Lee, I.J. Acceptance and influencing factors of social virtual reality in the urban elderly. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantianis, G. Sentiment Analysis for Cultural Venue Interfaces. Bachelor Thesis, Department of Informatics and Telecommunications, University of Peloponnese, Tripoli, Greece, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D.A. The Design of Everyday Things; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D.A. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Jiang, M.; Yin, H.; Wang, G.; Colzato, L.; Zhang, W.; Hommel, B. The impact of stimulus format and presentation order on social working memory updating. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2024, 19, nsae067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvert, L.; Naveteur, J.; Honoré, J.; Sequeira, H.; Boucart, M. Emotional stimuli in rapid serial visual presentation. Vis. Cogn. 2004, 11, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. An Argument for Basic Emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. Emotions Revealed: Recognizing Faces and Feelings to Improve Communication and Emotional Life; Times Books: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A. A Circumplex Model of Affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Core Affect and the Psychological Construction of Emotion. Psychol. Rev. 1983, 110, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soren, B.J. Museum experiences that change visitors. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2009, 24, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J.H.; Molani, Z.; Sadhukha, S.; Chang, L.J. Synchronized affect in shared experiences strengthens social connection. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).