1. Introduction

In wind energy projects, due diligence in the pre-construction phase typically requires an expensive data collection campaign lasting at least one full year, followed by long-term extrapolation over the project lifetime. In the current energy context—with an urgent need to reduce fossil-fuel dependence via renewables—hybrid projects that combine several resources are expected to expand rapidly, providing greater stability in power generation. The benefits and market opportunities of hybrid systems and renewables are discussed in [

1,

2].

A central challenge when estimating expected energy production for a given scenario is the accurate characterisation of the site’s typical wind-energy content. Recent overviews of energy-production prediction bias and loss accounting highlight that long-term resource characterisation and uncertainty quantification are now central elements of modern wind project due diligence [

3], underscoring the need for representative datasets that reflect multi-year climatic variability. Most specialised simulation tools rely on reference years to estimate production at a site. Furthermore, recent analyses of long-term resource uncertainty show that variability in the underlying wind resource can propagate into significant AEP deviations in real projects [

4], reinforcing the need for representative reference-year datasets. For compatibility with such tools (e.g., WAsP, HOMER), a reference year of the relevant resource (wind, solar, etc.) is required. This dataset must capture long-term climatic conditions (typically 15–20 years) while condensing them into a single “typical” year of 8760 hourly values.

The concept of a typical meteorological year has been widely studied in building-energy performance [

5,

6] and solar-resource assessment. Overviews and comparisons of algorithms can be found in [

7,

8]. More recently, ref. [

9] constructed a global TMY database directly from ERA5, confirming the feasibility of reanalysis-based typical years for building- and renewable-energy applications. Similarly, in the urban context, ref. [

10] used ERA5 in combination with an urban canopy model to generate urban typical meteorological year (uTMY) datasets for building-energy simulations, further illustrating the flexibility of reanalysis-based typical years across different applications. One of the most-used methods is the Sandia approach, which selects 12 typical months from a long-term dataset and concatenates them into a representative year [

11]. Updated versions were later developed at NREL [

12,

13]. Further developments include the modification of Sandia’s method to generate typical years at different time resolutions [

14]. However, classical TMY/WRY approaches were originally developed for building- and solar-energy applications and were not designed to preserve multi-site dependence, long-term climatic variability, or modern uncertainty requirements. Recent studies have shown that these aspects are critical for contemporary wind-resource assessment [

3,

4].

In the wind industry, however, there is no universally accepted methodology for generating a Wind Reference Year (WRY). As noted in [

15], a method based on the Finkelstein–Schafer statistic has been proposed and applied to a real case using reanalysis data. Since multi-year measurements are seldom available, reliance on long-term reanalysis products (e.g., ERA5 [

16]) has increased. Reanalysis nodes exhibit substantial uncertainties: they provide grid-averaged hourly values that require adaptation to the specific site. Recent validation studies [

17] show that ERA5 can provide reliable long-term wind resources and AEP estimates at flat and offshore sites, but performance degrades in complex terrain and coastal regions, highlighting the need for local adaptation methods such as MCP. This site-adaptation process, common in climate and meteorology, adjusts long-term modelled variables by comparison with observations. For example, refs. [

18,

19] explored bias-correction techniques based on quantile mapping. A recent critical review [

20] synthesises the main sources of uncertainty across 15 global and regional reanalysis products at more than 300 sites worldwide, underlining that spatial biases remain a key limitation for long-term wind resource assessment and reinforcing the need for local adaptation procedures such as MCP.

Most often, Measure–Correlate–Predict (MCP) is used to obtain representative long-term series: short-term site measurements are related to long-term references and corrected accordingly. In [

21,

22], the bin method is compared to linear regression, and ref. [

23] provides an extensive review of MCP methods since the 1940s, highlighting limitations and uncertainties. The MEASNET guide [

24] recommends combining site data (e.g., met-mast measurements) with concurrent long-term reference series, whether reanalysis or off-site measurements. More recent developments continue to demonstrate the relevance of advanced MCP formulations for long-term wind-resource assessment. For example, ref. [

25] applied an enhanced MCP framework to transfer wind speeds from MERRA2 reanalysis to turbine hub heights, achieving substantial improvements in long-term representativeness. These results highlight the importance of robust MCP-based site-adaptation procedures when reanalysis data exhibit spatial or height-related discrepancies.

To complement these developments and situate our work within the broader landscape of modern wind-energy modelling, several hybrid learning–observer approaches have also been explored to address uncertainty, noise, and stochastic variability. For instance, ref. [

26] proposed ANFIS-based interval observers for robust fault detection in wind turbines, while ref. [

27] developed MANFIS architectures combined with zonotopic observers to enhance resilience against measurement disturbances and model inaccuracies. Although these methods focus primarily on short-term operational dynamics rather than long-term climatological representativeness, they illustrate the increasing adoption of advanced data-driven and hybrid estimation techniques in wind-energy applications.

A notable example of reference-year construction is PVGIS (Photovoltaic Geographical Information System) [

28], which provides typical meteorological years for nine climatic variables by selecting the most representative months over a long-term period. The methodology, described in [

29] and based on ISO 15927-4 [

30], relies on the Finkelstein–Schafer statistic, with primary variables (irradiance, temperature, humidity) and secondary variables (such as wind speed). Although PVGIS targets solar energy and building applications, it also reports wind speed at 10 m without site adaptation. Commercial tools such as Windographer [

31] use Markov chains to generate representative years and include an MCP module for long-term extrapolation. Combining MCP-based site adaptation with a Markov chain generator enables a site-specific WRY.

In this work, machine-learning models are applied to capture long-term wind behaviour from 15 to 20 years of reanalysis. Specifically, Gaussian Mixture Copula Models (GMCMs) are used [

32]. Prior studies have leveraged GMCMs to augment machine-learning inputs with synthetic series [

33]. Here, synthetic data are generated to emulate long-term behaviour in an 8760-h dataset. Copula-based modelling has also seen increasing use in power-system applications, where it enables the generation of spatiotemporal wind-power scenarios together with explicit treatment of forecast errors [

34]. While such approaches focus on short-term operational uncertainty, the GMCM-based WRY developed in this work addresses a complementary problem: the long-term climatological representation of wind-resource variability.

Alternative approaches to impose temporal dependence on synthetic resource series include dependent-bootstrap schemes and sequence-assembly methods. In wind and solar applications, moving-block bootstrap techniques are widely used to reconstruct short-term persistence by resampling contiguous blocks of historical data [

35,

36,

37]. A second family of techniques relies on rank-based reordering, most notably the Schaake Shuffle and its more recent variants, which restore temporal and spatial consistency by imposing the rank structure of historical observations [

38,

39,

40]. While these methods are effective for generating coherent time series, they either replicate historical blocks or impose dependence indirectly through rank structure. In contrast, assignment-based approaches such as that introduced by Naimo [

41] provide a deterministic and distribution-preserving way to enforce persistence. Building on this line of work, the present study applies the Hungarian algorithm to introduce realistic temporal structure without altering the marginal or multivariate characteristics learned from long-term reanalysis.

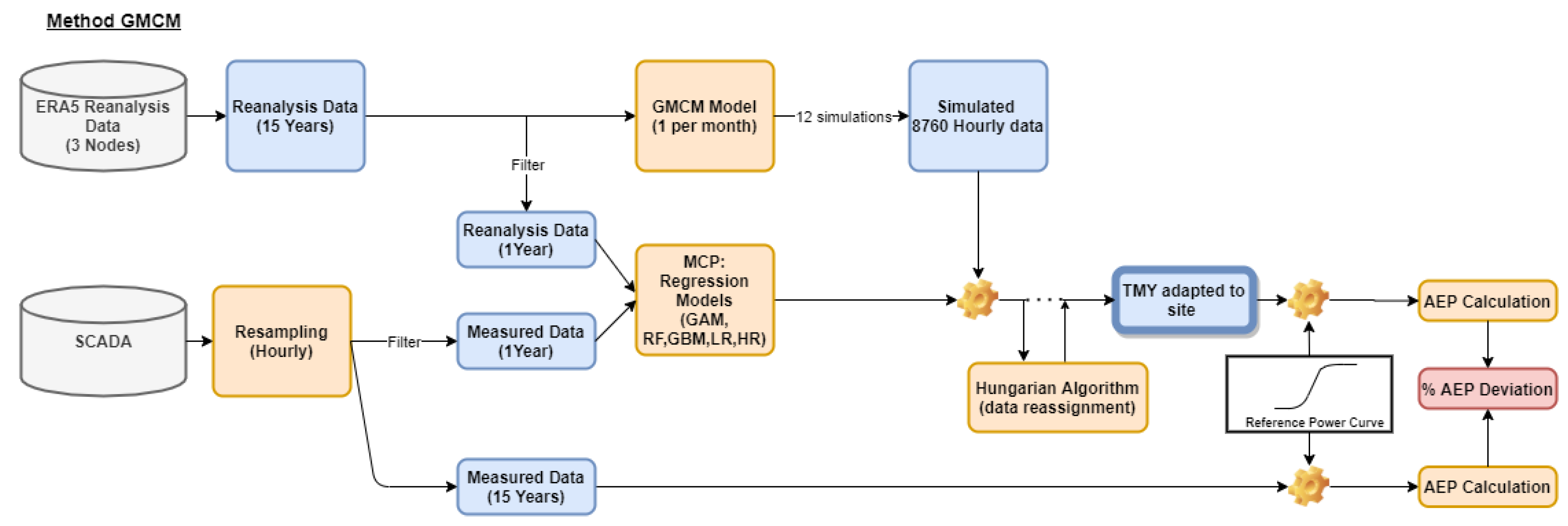

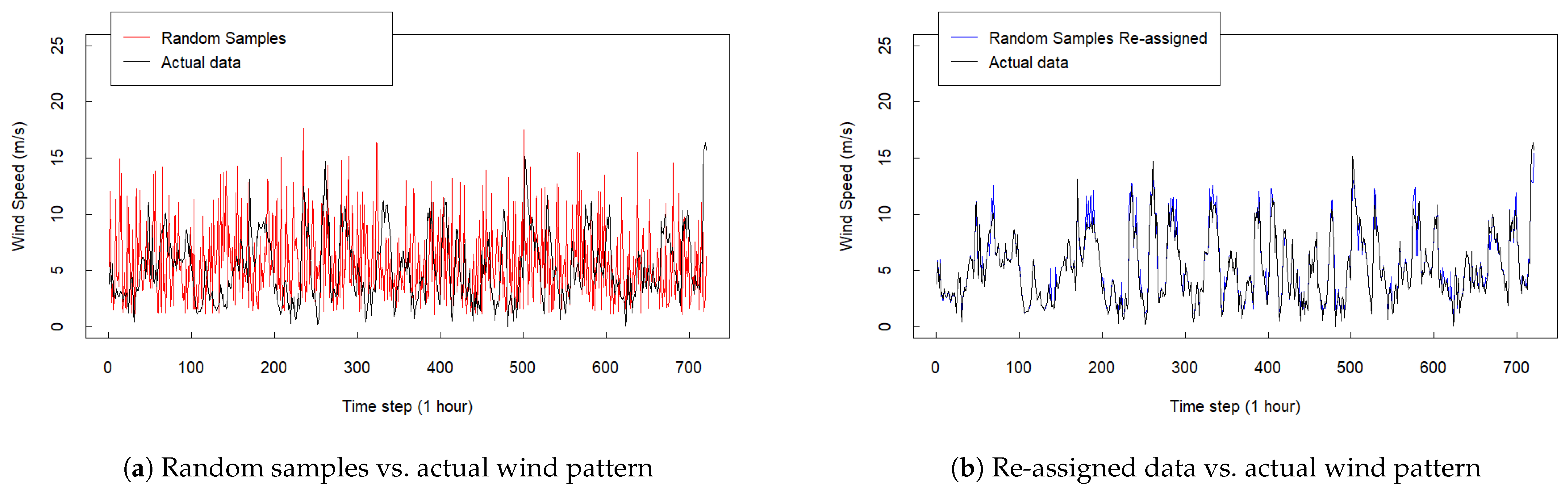

The proposed pipeline proceeds in three steps. First, copulas capture inter-variable dependencies and generate synthetic data consistent with the training period (GMCM). Second, the simulated series are adapted to site conditions via multiple regression models following the MCP framework, using one year of on-site measurements and long-term reanalysis. Finally, the simulated and site-adapted data are rearranged to preserve wind persistence and to ensure a consistent intra-annual wind pattern; to this end, the Hungarian algorithm is applied [

41].

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results. First, the GMCM trained on 15 years of ERA5 reanalysis is checked to reproduce long-term statistics when compressed into a one-year WRY before site adaptation (

Section 4.1). Second, after MCP-based site adaptation and temporal reordering via the Hungarian algorithm, energy representativeness is evaluated by comparing the WRY-derived AEP with the 15-year operational data and by inspecting monthly wind-speed and energy aggregates (

Section 4.2). For context, two baselines under identical pre-/post-processing are included: (i) heuristic month selection (ISO 15927-4 style; Euclidean distance on monthly mean and Weibull parameters) and (ii) the Windographer workflow (MCP plus the

Representative Year Window). The subsections report pre-adaptation consistency, site-adjusted performance, and head-to-head comparisons with the baselines.

4.1. WRY Before Site Adjustment

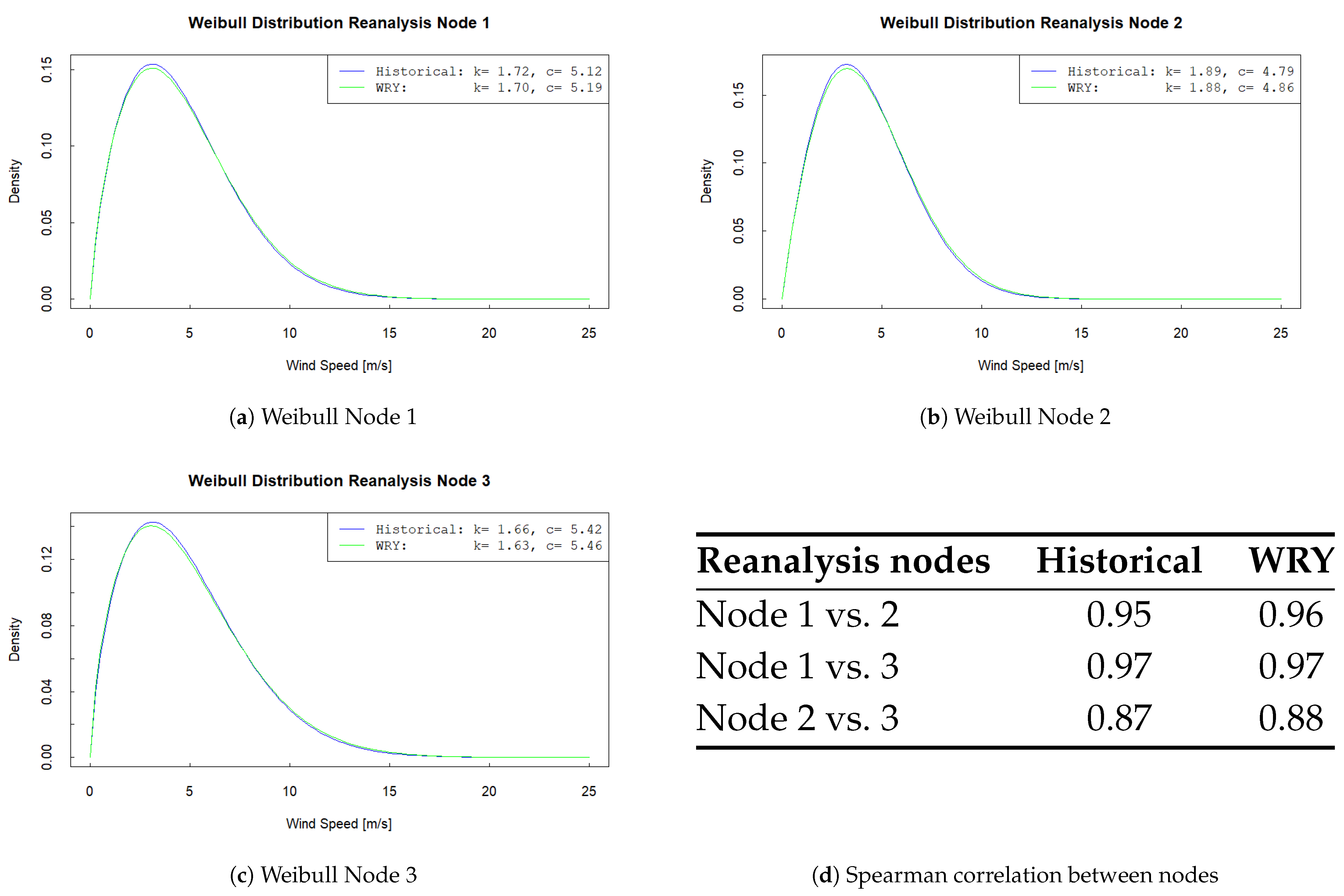

The capability of the GMCM to reproduce the characteristics of the historical reanalysis record must be confirmed. Consequently, the aggregation of historical reanalysis data is compared with the synthetic series generated by the GMCM and considered as the WRY before adjusting to the site. The Spearman correlation, distribution density functions, and monthly wind speeds are reported for each case.

First, the monthly wind speeds (monthly averages of the historical data and the monthly wind speeds of the WRY before site adjustment) for the three reanalysis nodes considered in the GMCM are compared.

Table 2 compares the monthly average wind speeds obtained from historical data at the three nodes with the GMCM simulations prior to site adaptation. Actual values from each node and their simulations show close similarity; the largest error among all cases is around 5%. This reinforces the proposed method’s capability to capture the nature of the sample.

Subsequently, in

Figure 3d, the Spearman correlations between the three reanalysis nodes are reported. Furthermore, the Weibull distribution is fitted to historical data from the reanalysis nodes and to the WRY (before site adjustment) in

Figure 3a–c.

It is confirmed that the relationship among the variables considered (the wind speeds at the three nodes) is preserved: the Spearman coefficients are practically identical in both cases (Vn1–Vn2 = 0.95 vs. 0.96; Vn1–Vn3 = 0.97 vs. 0.97; Vn2–Vn3 = 0.87 vs. 0.88). Thus, the robust performance of the GMCM in generating synthetic data from the sample is again reinforced.

In the comparison of Weibull distributions, the plots (

Figure 3a–c) show that, for each node, the Weibull fit (Equation (

1)) to the historical data is very similar to the fit to the simulated data, as are the estimated shape and scale parameters (see Equations (

2) and (

3)). Therefore, it can be concluded that the GMCM can simulate a distribution similar to that of the original historical reanalysis data.

4.2. WRY Adjusted to the Site

This section analyses the results obtained after adapting the simulated WRY to site conditions. The proposed GMCM method is compared against two baselines—a heuristic month-selection method from the literature and the Windographer commercial workflow. Metrics reported for each approach include Annual Energy Production (AEP), Weibull parameters, and monthly mean wind speeds.

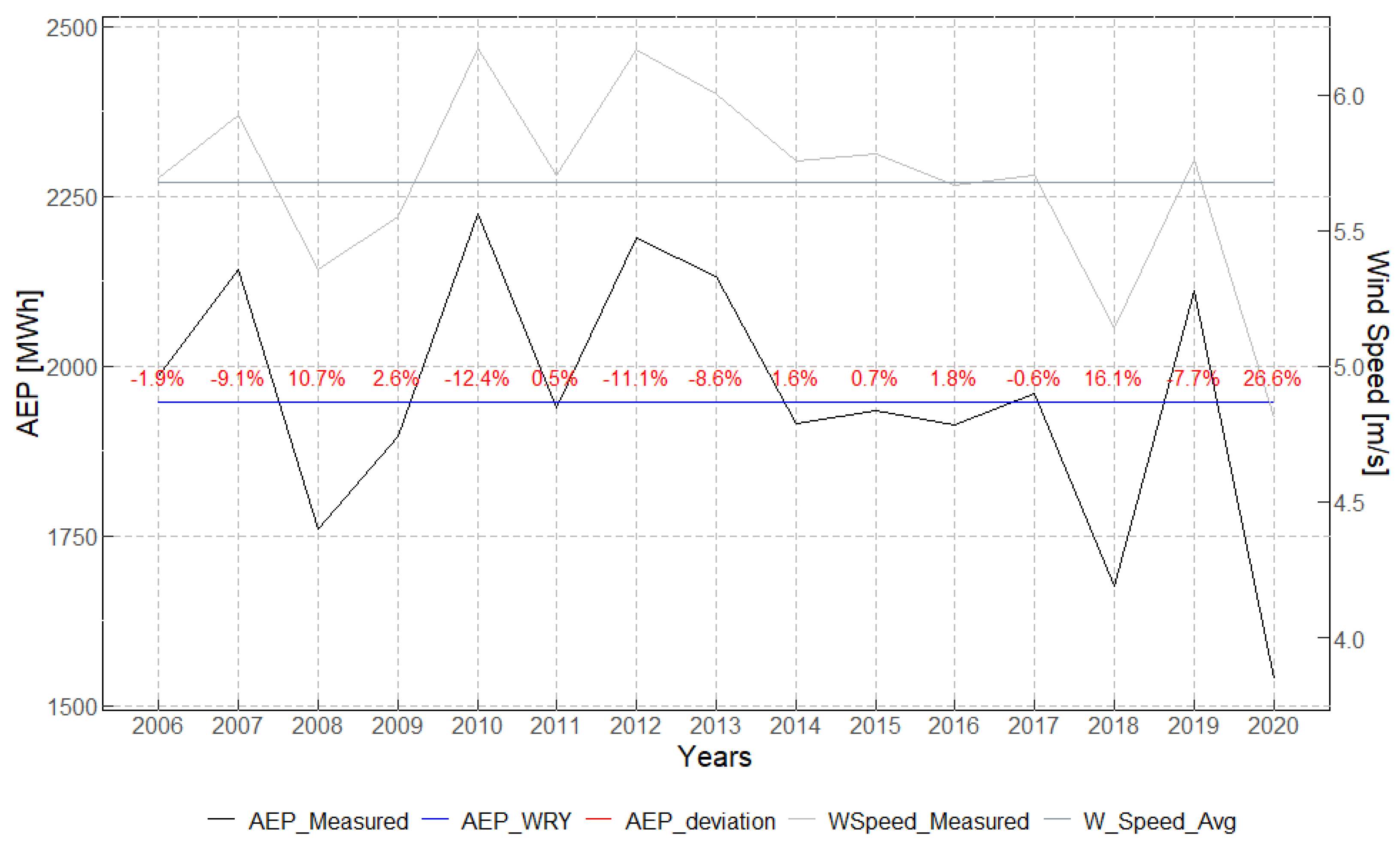

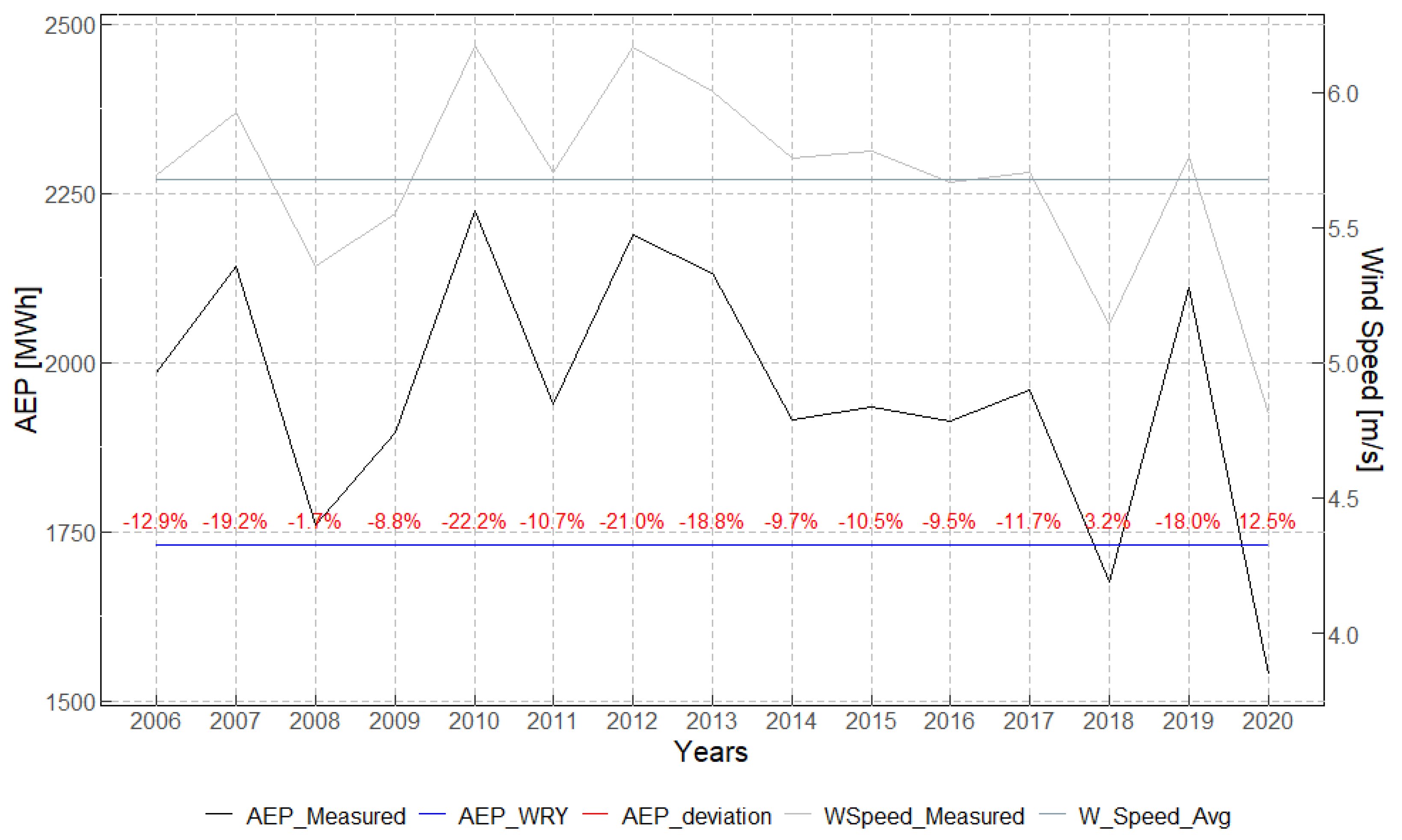

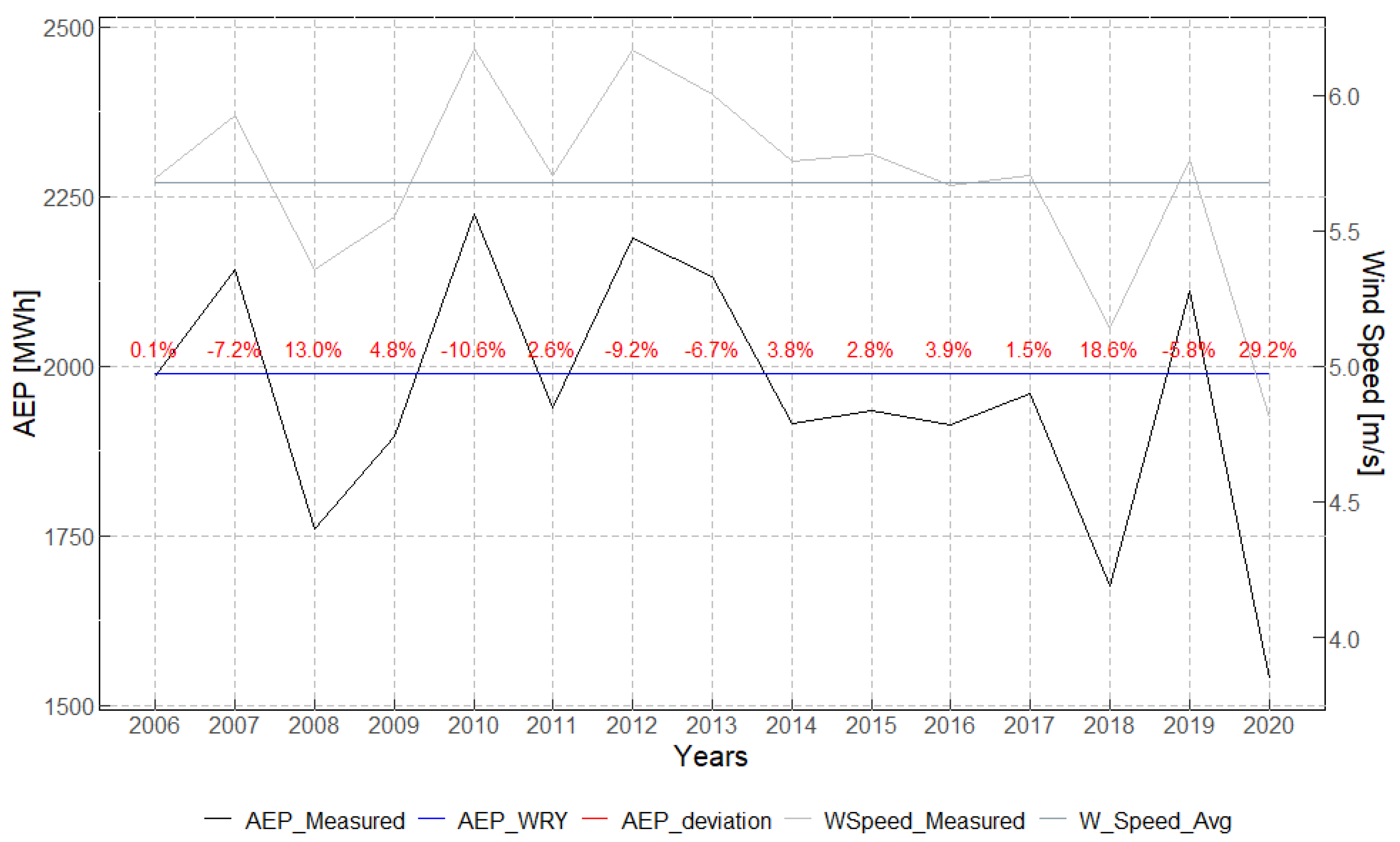

The AEP calculations are shown for the different MCP configurations (see

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5). In addition,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 compare the WRY-derived AEP with the annual AEP computed from the 15-year operational record. In each figure, the black line represents the annual AEP over the 15 available years, the blue line the AEP estimated from the corresponding WRY, and the red markers the percentage deviation of each year’s AEP from the WRY AEP. For context, the annual mean wind speeds (grey) are shown together with their 15-year average (dark grey).

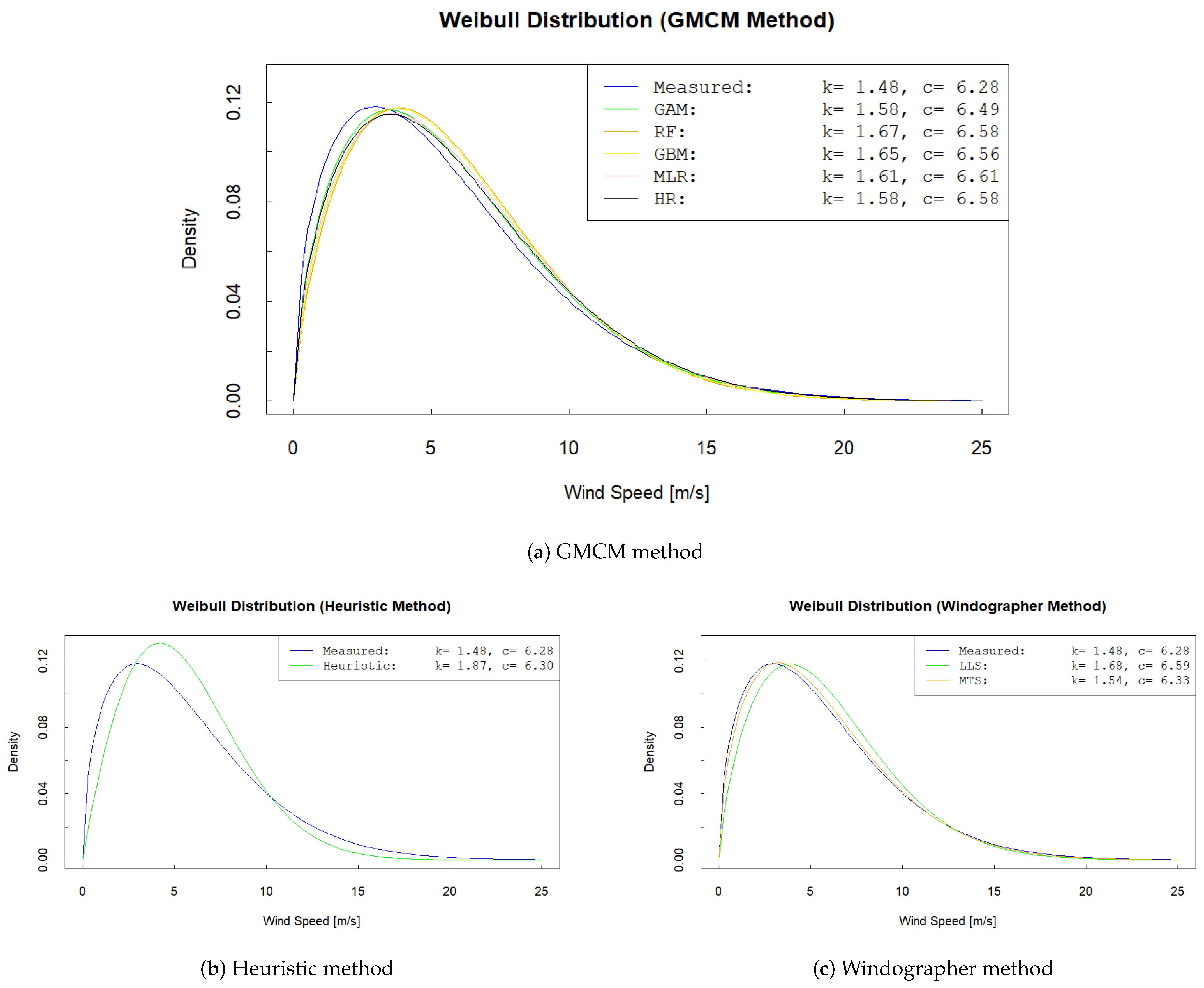

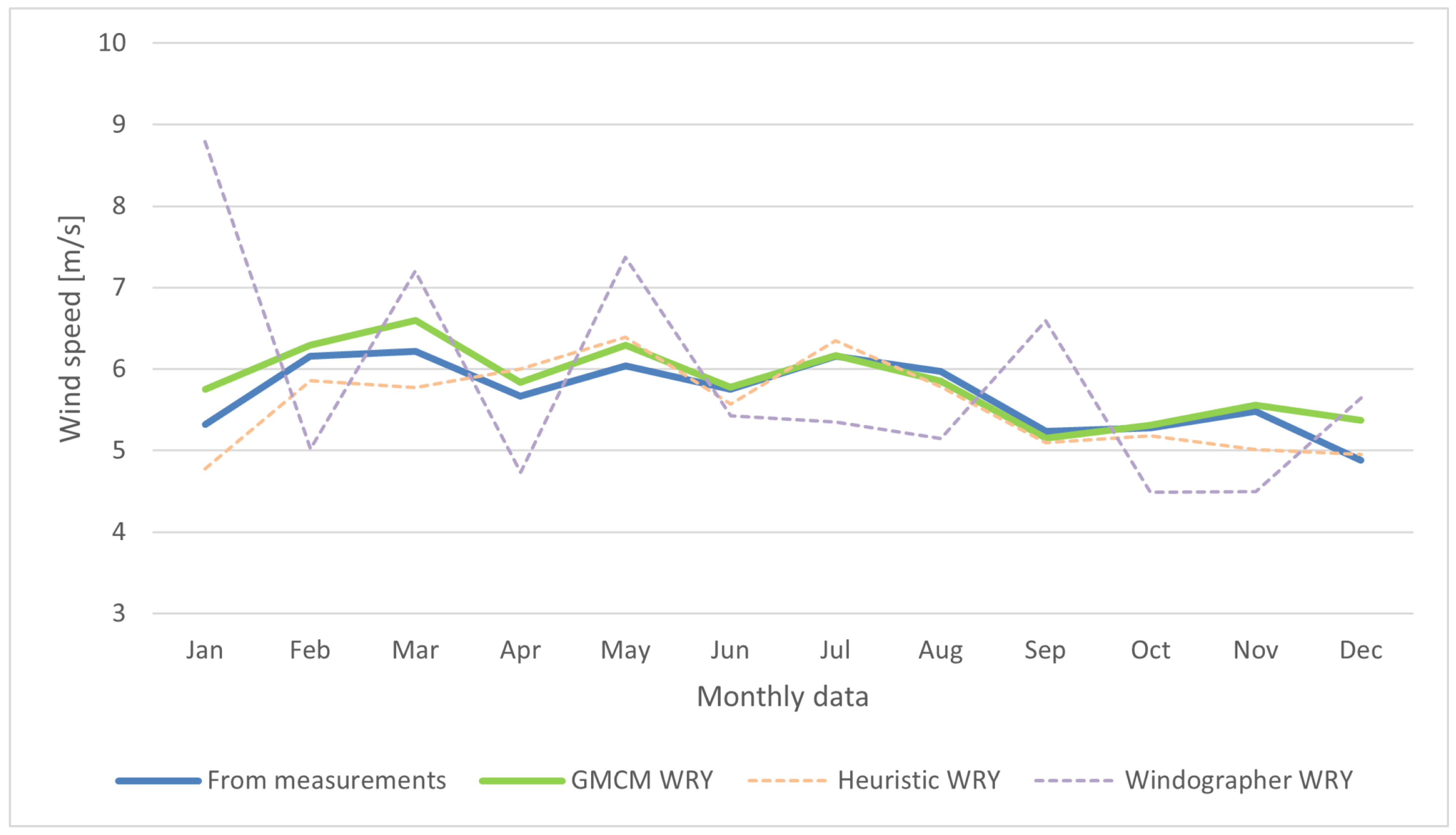

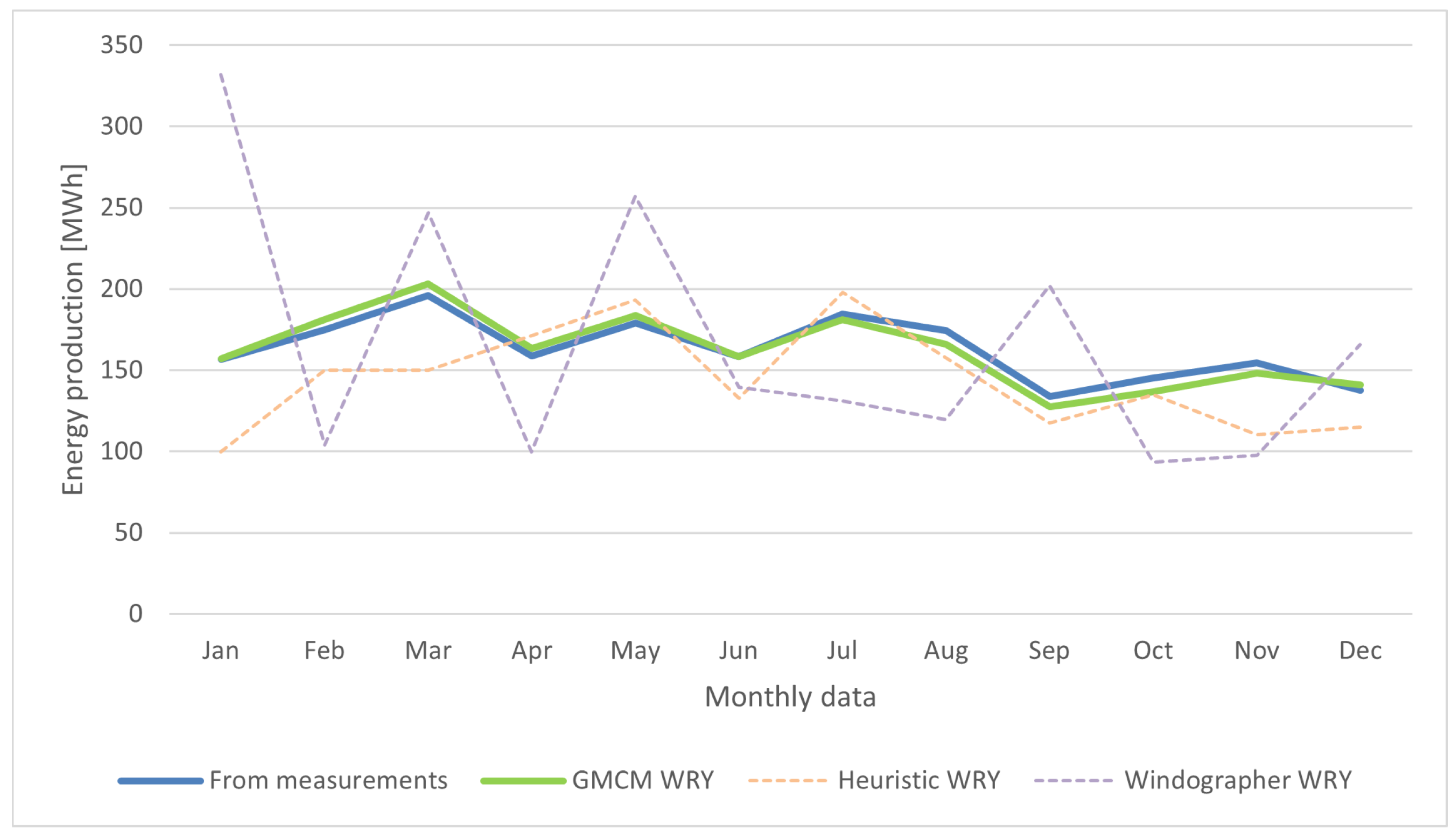

For the Weibull comparison, fitted parameters and the associated Weibull distributions are plotted in

Figure 7a–c. Monthly aggregates of mean wind speed and energy (the latter derived from the reference power curve) are provided in

Table 6 and

Table 7 and visualised in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

For the AEP comparison, the average annual energy from the 15-year measured dataset is taken as the benchmark and compared with the AEP obtained from each WRY. Because different regression models are used to adapt wind speed to the site, the resulting AEP varies by method and by model.

For the proposed GMCM-based method, the AEP differences range from

to

across the regression models tested. The best results are obtained with Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR), yielding AEP errors of

and

, respectively, whereas Multivariate Linear Regression (MLR) and Huber Regression (HR) show the largest positive biases. For the year-by-year comparison, we focus on the best case (GBR). As shown in

Figure 4, deviations with respect to the WRY AEP range from

to

; overall, this method most closely aligns with the 15-year average behaviour. The largest discrepancies correspond to years with unusually low or high wind resources (notably 2020 in this dataset). Despite year-to-year variability, the WRY estimate remains consistent with the long-term mean.

Regarding the heuristic baseline where a single Gradient-Boosting-based MCP model is applied, the AEP difference is substantial (

). This outcome is consistent with expectations: although a month is selected from the historical record to resemble long-term behaviour, its characteristics are not identical to the long-term climatology, so deviations are anticipated.

Figure 5 shows that the WRY AEP obtained with this method differs from the annual AEP values derived from the 15-year record by between 3% and 22%, depending on the year.

For the Windographer baseline, the AEP differences are

when using the

Linear Least Squares (LLS) option and

with the

Matrix Time Series (MTS) option provided in Windographer’s MCP module. For the year-by-year comparison, we focus on the best case (LLS). As shown in

Figure 6, the deviations with respect to the WRY AEP range from

to

; in general, the WRY estimate follows the multi-year average behaviour. The largest discrepancies occur in years with unusually low or high wind resources relative to the rest of the period.

In terms of AEP estimation, the best overall performance is achieved by the GMCM method combined with the GBR regression model for site adaptation.

In the comparison of Weibull distributions fitted to the real (measured) data and to the simulated WRY, similar conclusions are obtained. For the Heuristic method, the Weibull fit for the WRY differs slightly from the fit to the measured data (

Figure 7b). This is expected because the selected month from the historical record has characteristics that are close to, but not identical with, the long-term climatology.

By contrast, the fits for the GMCM and Windographer methods are much closer to the measured distribution (

Figure 7a,c). Both methods deliver an accurate representation of the site’s wind-speed distribution, with the MTS option in Windographer performing slightly better than the GBR-based case in GMCM. These outcomes emphasise the importance of the MCP method and, additionally, highlight the impact of reanalysis-data quality on the final result.

Once the best-performing case within each method has been identified, the analysis centers on the proposed GMCM method (with GBR-based MCP) and, for context, two baselines: the heuristic month-selection approach (Euclidean distance) and the Windographer workflow (LLS-based MCP). A monthly analysis of wind speed and energy is presented. Comparative tables report monthly mean wind speed and monthly energy production, and in all cases, the WRY-derived monthly series are contrasted with the 15-year measured aggregates.

Table 6 and

Table 7 summarize the monthly averages of wind speed and the corresponding monthly energy (computed with the site’s reference power curve) for the best-case configuration of the proposed GMCM method and for the two baselines—the heuristic approach and Windographer (best-case MCP option). For each month of a typical year, the tables report the deviation of the WRY-derived values from the 15-year measured aggregates.

The final outcome of the process is an hourly wind-speed time series that exhibits the hallmarks of a realistic wind pattern—persistence together with seasonal and diurnal variability. Moreover, the series can be regarded as representative of the site’s long-term behaviour.

In the proposed GMCM workflow, the simulated values are temporally reordered using the Hungarian algorithm to enforce persistence and realistic sequencing (see

Section 3.3). The resulting 8760 h WRY is therefore suitable for direct use in standard industry tools for energy assessment. For the proposed GMCM method, wind-speed deviations are ∼

–

, and production deviations are ∼0.1–

(absolute percentage). For the heuristic baseline, wind-speed deviations are approximately

–

, while production deviations are ∼7–

(absolute percentage). For the Windographer baseline, wind-speed deviations are ∼6–

, with production deviations of ∼13–

(absolute percentage). These deviations should also be interpreted in the context of typical uncertainty levels associated with long-term resource assessment. Recent studies report that wind-resource uncertainty alone can introduce AEP variations of ∼0.4–

in operational offshore projects [

4], indicating that the deviations obtained with the proposed WRY fall well within the expected range for real-world applications. These results confirm that, for both wind speed and energy, the proposed method attains the lowest monthly deviations, as also illustrated in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, where the WRY monthly wind speeds and the WRY monthly productions are compared against the 15-year measured aggregates.

5. Conclusions

This work demonstrates a method to estimate a Wind Reference Year (WRY) from fifteen years of reanalysis data combined with a one-year on-site measurement campaign. Results are compared against two practical alternatives: a heuristic month-selection approach based on practitioner expertise and the commercial Windographer workflow.

From the obtained results, we infer that the proposed method—based on Gaussian Mixture Copula Models (GMCMs)—captures long-term wind behaviour and can generate synthetic series suitable for WRY estimation. Moreover, applying the Hungarian algorithm to temporally reassign the simulated values ensures that the final series respects wind persistence and exhibits a realistic seasonal and diurnal pattern.

Site adaptation remains a challenging step. Several regression models were evaluated (GAM, RF, GBR, MLR, and HR). In this case study, the Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) provided the best performance, with an AEP deviation of approximately 0.3% relative to the multi-year measurements. The quality of the long-term reference and the strength of correlation between measured and reanalysis data are critical to achieving robust outcomes. Although the energy results are satisfactory, there is still room for improvement in the transposition from reanalysis to site conditions.

As with any typical-year construction, the proposed WRY is not intended to reproduce event-scale dynamics, such as gusts or abrupt regime transitions, since these behaviours are inherently smoothed when condensing multi-year data into a representative year. The method may also face limitations at sites where reanalysis nodes exhibit weak correlation with local measurements or in environments affected by strong non-stationarity, where long-term representativeness becomes more difficult to achieve. These aspects define natural boundaries of applicability and point to opportunities for methodological refinement.

Future work will consider higher-quality long-term references from meteorological reanalyses (e.g., the global meteorological reanalysis model Vortex) and additional site-adaptation strategies. In parallel, to support hybrid plant design, the WRY dataset should be extended to incorporate other renewable resources (e.g., solar) while preserving their joint dependence structure within a common, multi-source reference year. This will enable consistent, multi-vector resource assessments that remain faithful to the temporal co-variability required by modern hybrid systems.