1. Introduction

The increasing integration of artificial intelligence into high-stakes decision-making processes has changed operational practices in many industries, with human resource management and higher-education admissions among the primary areas of application. The student admission process, particularly for international candidates, can be viewed as a specialized case of personnel recruitment, sharing fundamental challenges of scalability, objectivity, and the valid assessment of applicant potential. Consequently, technological solutions developed in one domain are often applicable to the other. Motivated by these challenges, we introduce FAIR-VID, a multimodal preprocessing pipeline designed for the transparent and fair evaluation of applicant documents, video interviews, and forms. The system addresses the growing demand for AI-enabled workflows that can holistically analyze diverse applicant information while maintaining the robustness, transparency, and ethical accountability required in high-stakes contexts.

In many current systems, the initial phase of the application process—where candidates submit curricula vitae (CVs), application forms, and educational certificates—is managed by rule-based document management systems. These platforms are typically limited to verifying the presence of required documents and extracting basic structured data, such as identification numbers, course names, and grades. A significant and persistent challenge arises when evaluating documents from international applicants, as these systems lack the contextual understanding to consistently and fairly compare qualifications across disparate educational frameworks. This paper introduces a novel solution to this problem, leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) augmented with a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) architecture that draws upon a curated knowledge base, such as Wikipedia’s detailed entries on country-specific education systems. This approach moves beyond simple validation to provide a context-aware and equitable preprocessing of international credentials, forming a foundational layer of fairness from the very start of the pipeline.

Following the initial document screening, the interview stage represents another critical juncture for AI-driven innovation. Automated Video Interviews (AVIs) have emerged as a scalable and standardized method for initial applicant assessment. Building upon prior research that has established the psychometric viability of AVIs for evaluating constructs like cognitive ability [

1], our work focuses on building a pipeline that fully capitalizes on this rich data source. Previous studies have demonstrated that while AI-scored interviews can be more resistant to score inflation than self-reports, the need for objective, multi-faceted evaluation remains paramount to mitigate impression management and potential fraud. The FAIR-VID pipeline addresses this by not only analyzing interview content but also integrating it with data from submitted documents, creating a unified and comprehensive applicant profile.

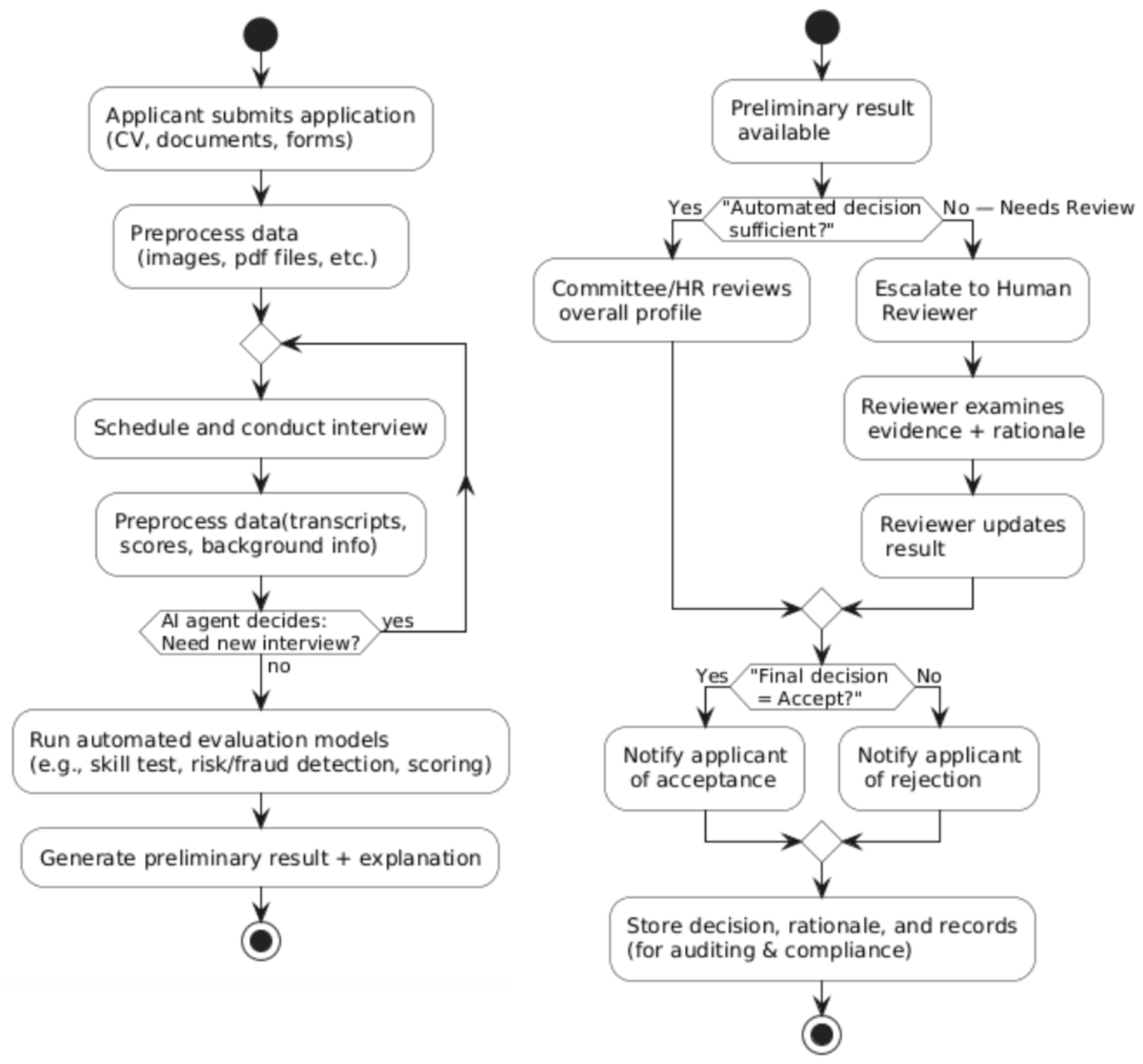

To contextualize our contribution,

Figure 1 illustrates the end-to-end admission workflow envisioned by the FAIR-VID project. The diagram explicitly demarcates the boundary between automated processing (left panel) and human authority (right panel) to visualize where the AI’s role ends and human judgment begins. The left panel outlines the pipeline that is the primary focus of this paper. It begins with the applicant’s submission of multimodal data, which is then processed through an iterative cycle of automated interviews and data enrichment. An AI agent determines if follow-up interviews are necessary, creating subsequent questions and dialogue flows to probe specific areas of the applicant’s profile. The automated phase ends in the execution of evaluation models—including skills tests, risk and fraud detection algorithms, and holistic scoring—to generate a preliminary result accompanied by a detailed, explainable rationale. The right panel of

Figure 1 depicts the subsequent stage, where this AI-generated output serves as a decision-support tool for human experts, who retain authority in the final selection, thus ensuring a model of human-AI collaboration.

This paper details the design and implementation of the multimodal pre-processing pipeline that underpins this entire system. Its central novelty lies in its ability to fuse heterogeneous data modalities into a structured, semantically rich dataset suitable for training sophisticated deep learning models. Specifically, we move beyond conventional feature extraction by employing generative AI to convert unstructured visual data from video interviews—such as key image frames depicting applicant behavior and environment—into structured textual descriptions. This transformation enriches the dataset with a new layer of semantic information, facilitating more nuanced analyses of non-verbal cues and contextual factors. In line with the growing demand for trustworthy AI, our approach emphasizes transparency and the use of open-source modules, ensuring that each step of the interaction between applicants, AI agents, and institutional decision-makers is auditable and explainable.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the related work in automated video interviews, document intelligence, and audiovisual forgery detection.

Section 3 details the methodology for our advanced document analysis, tracing the evolution from layout-aware transformers to the zero-shot capabilities of large multimodal models and presenting our novel RAG-based framework for credential adjudication.

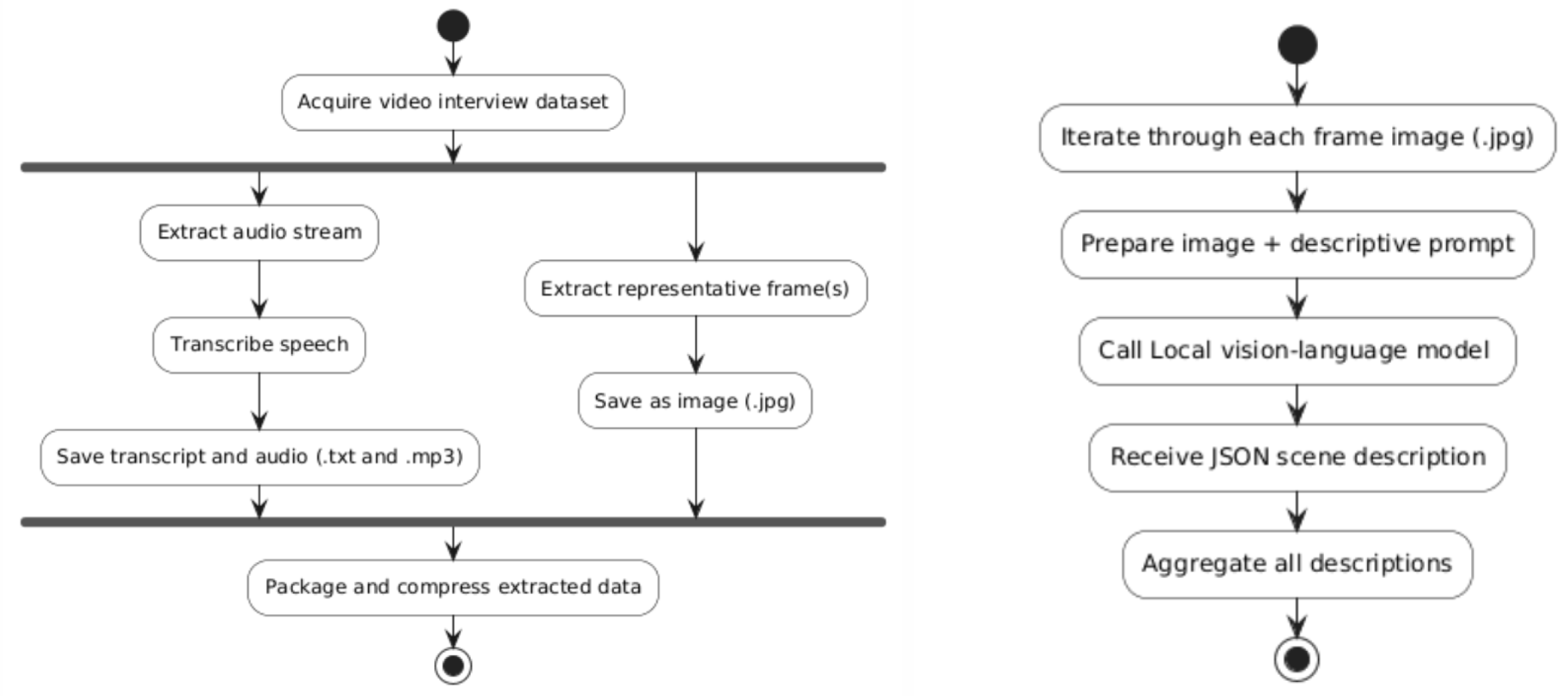

Section 4 describes the implementation of the multimodal data processing pipeline for video, audio, and visual data, detailing the two-phase process of data deconstruction and generative AI-based enrichment.

Section 5 discusses the implications of this complete pipeline for training next-generation assessment systems and its broader applications in creating fairer and more effective admission and recruitment workflows. Following this,

Section 6 will present the results of our proof-of-concept and discuss their implications for fairness and fraud detection. It will outline the experimental setup for evaluating the pipeline, including the datasets used and the fusion of the processed modalities. Finally,

Section 7 will conclude the paper, summarize our contributions, and outline directions for future work.

2. Related Work

The FAIR-VID pipeline builds upon and integrates advances across several related research domains, including multimodal artificial intelligence, document intelligence, speech and video forensics, and knowledge-based reasoning. This section places our work within the broader scientific field, reviewing key developments and remaining challenges in document understanding, vision-language modeling, speech processing, video forensics, multimodal fusion, retrieval-augmented generation, AI fairness, and predictive analytics in high-stakes decision-making. While extensive research exists on document intelligence, automated video interviews, and multimodal fusion, the literature reveals a notable absence of end-to-end multimodal preprocessing pipelines specifically designed for admissions or HR decision workflows. Existing commercial systems typically handle only isolated components—such as résumé parsing, video interview scoring, or fraud detection—without unifying heterogeneous modalities into a single auditable representation. To the best of our knowledge, no prior work has proposed a transparent, open-source, and regulation-aligned preprocessing pipeline that integrates documents, audio, transcripts, and visual data into a standardized applicant profile. This paper therefore fills a methodological gap by presenting FAIR-VID as a holistic, multimodal preprocessing architecture.

Document Image Understanding. The field of document intelligence has moved from traditional optical character recognition (OCR) toward end-to-end deep learning models that process visual, text, and layout information together. The LayoutLM family of models [

2] created a method of pretraining transformers on document images by adding location information with text data, greatly improving key-value extraction from structured forms. Later work, such as LayoutLMv3 [

3] and LiLT [

4], improved pretraining efficiency and the ability to work across languages, showing that combined text-image representations work better than separate OCR then Natural Language Processing (NLP) pipelines.

More recent approaches, such as OCR-free models like Donut [

5] and Pix2Struct [

6], have appeared that treat document understanding as a direct image-to-text generation task. This approach removes the need for unreliable, middle-step OCR processes, making it especially useful for the FAIR-VID system, which must handle non-standard credentials and poor-quality scans from many different global sources.

In the admissions field, AI services now read transcripts and credential images to pull out grades and check if they’re real, sometimes using LLMs or Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training (CLIP) style vision-language models to read scanned certificates. FAIR-VID builds on this work by using generative image-to-text models to turn applicant-uploaded images of credentials into computer-readable text, cutting down on OCR errors. Also, credential review can be improved through retrieval: by connecting to official data (university catalogs, accreditation lists), the system checks if courses match up or if degrees are valid. While fewer studies focus on credential checking in admissions, FAIR-VID’s pipeline uses advanced document transformers and knowledge retrieval to fill this gap.

Vision-Language Models and Generative Enrichment. The recent growth of Vision-Language Models (VLMs) and Large Multimodal Models (LMMs)—such as CLIP, Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training (BLIP) [

7], Gemini, and GPT-4o—has created new possibilities for interview preprocessing by changing how zero-shot visual understanding works. These systems learn matched image-text representations, allowing open-vocabulary recognition and descriptive captioning without direct supervision. For example, models like BLIP work well at image captioning and can apply to video tasks even in zero-shot settings.

Building on these basics, “Vision LLMs” can look at facial images to figure out characteristics; a recent study shows that fine-tuned VLMs can predict age, gender, and emotion from regular photos with results equal to specialized classifiers [

8]. Such models can create text summaries of a candidate’s expression or posture. In credential processing, generative V-L systems can also improve OCR by “making up” missing text or fixing errors using context.

FAIR-VID uses this approach to add textual descriptions to video frames and document images, a process we call “generative enrichment.” This method turns raw pixels into meaningful, language-matched representations that can be combined with transcript and document data. This goes beyond most current pipelines, which rarely use advanced V-L generation. However, issues of hallucination, spatial grounding, and factual consistency remain unsolved. To reduce these issues, FAIR-VID combines LMM outputs with layout-extracted metadata and time-based consistency checks, making sure that visual descriptions can be traced back to specific video frames and document references.

Speech Processing and Speaker Verification. Automatic speech recognition (ASR) and speaker verification have been changed by self-supervised learning. Models like wav2vec [

9] and HuBERT [

10] learn audio representations from unlabeled data, capturing phonetic and prosodic features. OpenAI’s Whisper extended this to a multilingual ASR model with near-human accuracy across a wide range of languages, accents, and acoustic conditions. For speaker verification, architectures such as x-vector and ECAPA-Time Delay Neural Network (TDNN) [

11] have become standard, achieving low error rates on established benchmarks. These technologies, along with toolkits for paralinguistic analysis like openSMILE [

12], form the foundation of FAIR-VID’s speech processing module for transcription, identity verification, and non-verbal feature extraction.

Video Forensics and Deepfake Detection. The proliferation of generative video manipulation has spurred significant research in deepfake detection. Foundational work in audiovisual synchronization, such as SyncNet [

13], introduced deep learning methods to verify temporal consistency by analyzing lip movements. The “LipForensics” approach [

14], which is also cited for its multimodal analysis, specifically leverages lip movement patterns as a modality-specific signal to achieve strong cross-dataset generalization in forgery detection. Datasets like FaceForensics++ [

15] fueled the development of detectors trained to identify subtle artifacts in facial dynamics, lighting, and compression. Subsequent research has shown that multimodal approaches, which combine visual cues with audio-visual synchronization analysis [

16], offer higher reliability. While recent methods use self-supervised learning to improve generalization to unseen manipulation techniques, robust cross-dataset performance remains a challenge. FAIR-VID incorporates these lessons by integrating speaker verification with lip-sync analysis and visual forgery detection. Crucially, instead of providing a binary fraud classification, our system generates evidential metadata (e.g., confidence scores, timestamps) to support transparent human review, aligning with calls for greater interpretability in digital forensics.

Multimodal Data Fusion. Integrating different data modalities is a central challenge in AI. Methods have moved from early fusion (concatenating embeddings) and late fusion (combining predictions) to more advanced techniques based on cross-modal attention [

17]. Contrastive learning frameworks like CLIP [

18] have been particularly influential, learning a shared latent space where different modalities can be directly compared and combined. Such approaches have been shown to improve performance on complex reasoning tasks. FAIR-VID uses a staged fusion architecture: document entities are extracted first, followed by the fusion of video and audio streams, with the resulting representation feeding into a final reasoning layer. This modular design improves traceability and aligns with best practices for building explainable multimodal systems.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Grounded Reasoning. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) [

19] improves large language models by grounding their outputs in externally retrieved evidence. This approach reduces hallucination and enables responses that are factual, context-aware, and attributable to specific sources. Later research has extended RAG to handle long-context reasoning, citation tracking, and structured knowledge grounding [

20]. FAIR-VID applies RAG in its Cross-Border Adjudication Matrix, which queries knowledge bases like International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) and European Network of Information Centres (ENIC-NARIC) to assess credential equivalence. This approach mirrors the use of RAG in other high-stakes domains, such as legal and policy analysis, where provenance and auditability are critical.

Fairness, Governance, and Human-in-the-Loop Systems. The deployment of AI in education and employment requires careful consideration of fairness, transparency, and accountability. Foundational work in algorithmic fairness has identified numerous sources of bias in data, models, and deployment contexts [

21,

22,

23]. In multimodal systems, these risks are increased by potential biases related to accents, facial attributes, and document formats [

24,

25]. In response, research has focused on developing explainability techniques for multimodal models [

26] and designing human-in-the-loop (HITL) governance frameworks that preserve human oversight [

27]. FAIR-VID implements these principles by designing its pipeline around interpretable, auditable outputs (e.g., structured data, timestamped transcripts, provenance logs), enabling human review and aligning with emerging regulatory standards like the EU AI Act.

Predictive Modeling in Admissions and HR. There is a growing body of literature on the use of automated systems for applicant screening and interview analysis. Studies on asynchronous video interviews and personality prediction have shown that multimodal cues can predict performance and engagement [

28,

29]. However, such systems have been criticized for their opacity and potential for bias [

30]. Research specifically focused on automated video interviews confirms their increasing use for efficiency but also notes that their validity and fairness remain active areas of investigation [

31,

32]. Notably, the specific problem of applicant fraud within these interviews, such as the use of deepfakes or pre-scripted answers, has received limited academic attention [

33]. FAIR-VID addresses these concerns by explicitly separating data preprocessing and enrichment from downstream predictive modeling. By producing standardized, provenance-aware representations, our system ensures that any subsequent predictive models are built on a transparent and auditable foundation, supporting reproducibility and bias auditing.

3. End-to-End Visual Document Analysis

This section describes the visual-document analysis component of FAIR-VID and explains why robust document understanding is a prerequisite for fair multimodal admission decisions. Below we outline the practical constraints that motivate our design choices and summarize the operational trade-offs that guided model selection and system architecture. While FAIR-VID centers on multimodal fusion, reliable applicant assessment depends equally on accurate, context-aware document understanding. Traditional document processing systems—typically reliant on rigid templates and basic optical character recognition—struggle to cope with the diversity of international diplomas, transcripts, and identity documents. For admissions workflows, document understanding is therefore not a simple automation problem but one of accuracy, explainability, and verification.

3.1. Key Challenges in International Credential Processing

We begin by listing the practical obstacles that make credential processing particularly challenging in cross-border admissions settings. In international student admissions, document evaluation remains one of the most labor-intensive stages of the process. Unlike video interview scoring, which can be standardized and automated relatively easily, document verification requires human-level reasoning across heterogeneous layouts, languages, seals, and grading conventions. These documents carry significant decision weight; even small extraction errors can distort an applicant’s profile and lead to biased or inconsistent outcomes.

Accuracy in information extraction is critical because even small OCR or parsing errors can mischaracterize an applicant’s record and propagate through downstream models. Therefore, extracted text should be treated as a hypothesis that is verified by complementary signals or human review rather than as ground truth. OCR results cannot be treated as unquestionable truth, since errors in text segmentation, recognition, or language encoding often propagate through downstream models.

In FAIR-VID, OCR output is regarded as a preliminary hypothesis that must be verified by complementary models or human oversight. To minimize such propagation of uncertainty, the pipeline adopts a dual-model strategy—combining OCR-based extraction with direct vision-language reasoning.

Another major constraint arises from data annotation requirements. Fine-tuning document models such as LayoutLM or Donut usually requires large, manually annotated datasets with bounding boxes, entity labels, and field relationships. For global admissions, where credentials vary across thousands of institutions and hundreds of document formats, such annotation is prohibitively expensive and impractical. Consequently, FAIR-VID prioritizes models and methods that generalize to unseen document structures without the need for exhaustive labeled data.

These real-world constraints—verification demands, OCR uncertainty, and the infeasibility of large-scale fine-tuning—directly shaped the FAIR-VID approach to building a reliable and auditable document understanding system.

3.2. Zero-Shot Document Understanding Strategy

Given these constraints (verification needs, OCR fragility, and annotation costs), we prioritized approaches that reduce dependence on large labeled corpora and that support rapid, explainable inference—which motivated a zero-shot prompt-based strategy described next. To address these challenges, development began with a local large language model (LLM)—Google’s Gemma 3 (27B)—as the central engine for the first version of the FAIR-VID document pipeline.

In our zero-shot setup each document image is supplied together with a compact, structured natural language prompt that specifies target fields and a machine-readable output format (for example, JSON), enabling direct image to structured text inference without task-specific fine-tuning. This prompt-based, zero-shot workflow enables rapid experimentation and bypasses the need for task-specific fine-tuning, allowing the system to handle highly diverse document types. Gemma 3 was selected over Donut- and LayoutLM-style architectures because it does not require any task-specific training dataset, making it better suited to the highly heterogeneous and globally diverse credentials encountered in international admissions. Additionally, in contrast to proprietary multimodal models such as GPT-4o, Gemma 3 can be deployed on institutional hardware and a single GPU, ensuring full data locality and compliance with privacy regulations while maintaining strong zero-shot interpretability.

A practical limitation is that generative LMM outputs can sometimes hallucinate; we therefore pair the zero-shot path with a verifiable OCR branch to provide spatial grounding and error checks. The verified results from this stage also serve as a foundation for benchmarking and constructing training data for secondary models.

Although Gemma 3 shows strong zero-shot performance and development efficiency relative to older end-to-end models (e.g., Donut), we maintain a complementary LayoutLM + OCR branch to provide explicit spatial grounding and visual evidence for extracted fields. This secondary path is essential for explainability: it enables bounding-box visualization of extracted fields, allowing the system to justify its decisions and support transparent human-AI interaction interfaces. In practice, Gemma 3 provides semantic interpretation, while the LayoutLM + OCR pipeline ensures spatial grounding and verification consistency.

3.3. Model Justification and Practical Trade-Offs

This subsection summarizes why we selected the chosen components and highlights the main trade-offs considered: accuracy vs. annotation cost, zero-shot flexibility vs. verification needs, and runtime/energy vs. local privacy controls. Specifically:

- (1)

a zero-shot LMM (Gemma 3) minimizes annotation overhead and scales across diverse layouts;

- (2)

a LayoutLM + OCR path provides inspectable bounding boxes required for audits;

- (3)

local deployment of heavier verification components balances privacy with compute cost.

Empirical evaluation confirms that the Gemma 3 approach provides superior flexibility and development efficiency, making it suitable for large-scale document ingestion and zero-shot inference. That said, once a sufficiently large, verified corpus exists, end-to-end models such as Donut may become preferable because they require less task orchestration and typically offer smaller model footprints, lower energy use, and faster per-document throughput.

In the current operational configuration of FAIR-VID, the combined LayoutLM + OCR branch remains essential because it provides spatial grounding and visual evidence for each extracted field. This verification capability is critical for explainability, auditability, and human–AI collaboration in the document analysis process, particularly in cases involving ambiguous or high-risk credentials. While the Gemma 3-based semantic interpretation module offers strong zero-shot performance and development efficiency, the layout-aware branch complements it by enabling explicit field localization and visual justification. Maintaining both pathways therefore ensures that extracted information can be inspected, validated, and traced to the underlying document structure, supporting the reliability requirements of international admissions workflows. We acknowledge that the current zero-shot strategy may underperform on rare credential formats, and the absence of fine-tuned domain-specific weights remains a limitation at this stage of deployment.

3.4. Integration into the Multimodal Pipeline

This subsection explains how document outputs are packaged and handed off to downstream actors so that they can be fused with video and behavioral signals described in

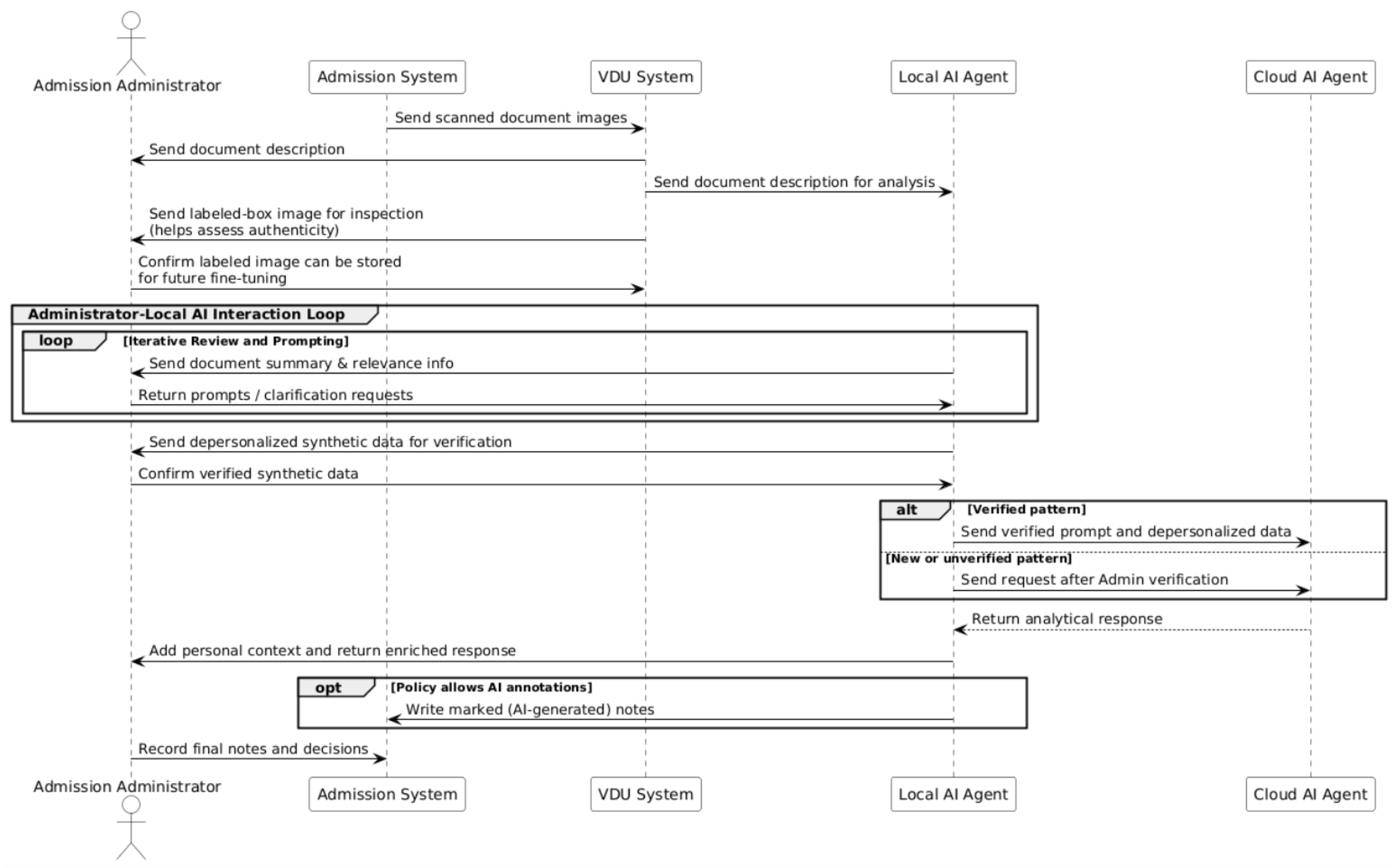

Section 4. The overall interaction among the admission system, the visual document understanding subsystem (VDU), the local and cloud AI agents, and the human administrator is summarized in

Figure 2. This sequence diagram is structured to clarify the flow of information, distinguishing the iterative verification loop from the final, linear hand-off to the admission system. The process begins in the admission system, where applicants register and upload scanned documents alongside other application data. These document images are transmitted to the VDU system, which performs multimodal visual analysis and entity extraction using both the Gemma 3-based semantic reasoning module and the LayoutLM + OCR verification branch. The extracted information is represented in structured JSON form and accompanied by labeled document images that highlight identified fields.

The VDU forwards structured JSON outputs and visualized, labeled images to the admission administrator for human inspection. Simultaneously, the local AI agent ingests the same outputs for contextual interpretation and downstream fusion. The visualized, labeled images are particularly valuable for human review, since formatting, texture, and visual authenticity cues provide additional evidence that purely textual transcripts cannot convey. Upon administrator approval, these labeled samples may be retained for future fine-tuning and validation of the VDU models.

A central operational feature is an interactive review loop: administrators request clarifications or corrections and the local AI agent responds with updated interpretations or grounding evidence. This loop functions as a conversational review cycle in which the administrator requests clarifications, issues new prompts, or provides feedback on extracted entities, while the local AI agent responds with updated interpretations or relevance assessments. Through this iterative exchange, the system ensures that all extracted data remain contextually valid and institutionally compliant.

Once verified, the local AI agent depersonalizes the data—removing identifiable information and transforming sensitive fields into synthetic or abstracted forms—before forwarding reasoning tasks to the cloud AI agent. The cloud AI agent, operating exclusively on anonymized profiles, executes advanced reasoning and knowledge-based validation steps. This strict separation ensures that computationally heavier cloud reasoning never accesses personal identifiers, in line with EU AI Act requirements. Its prompts are published in open repositories to ensure transparency, while its responses may optionally be archived for reproducibility. The resulting insights are returned to the local AI agent, which re-integrates contextual and personal details before presenting the complete, interpretable output to the admission administrator.

We note that this depersonalization and cloud/local split reduces privacy risk but does introduce an additional verification step that must be audited in practice. Depending on institutional policy, the local AI agent may annotate or insert AI-generated notes directly into the admission system. Finally, the admission administrator consolidates all AI-generated outputs, human observations, and validation results within the admission system, completing the end-to-end cycle from document submission to verified, explainable, and auditable decision support.

5. A Multimodal Data Fusion Pipeline

This section explains how FAIR-VID merges the processed document, audio, and video streams into a unified reasoning pipeline. We describe the rationale for each fusion stage and clarify how these components jointly support transparent, auditable decision-making. Having established how documents and video interviews are independently analyzed, we now detail how these heterogeneous representations are combined to form a coherent applicant profile.

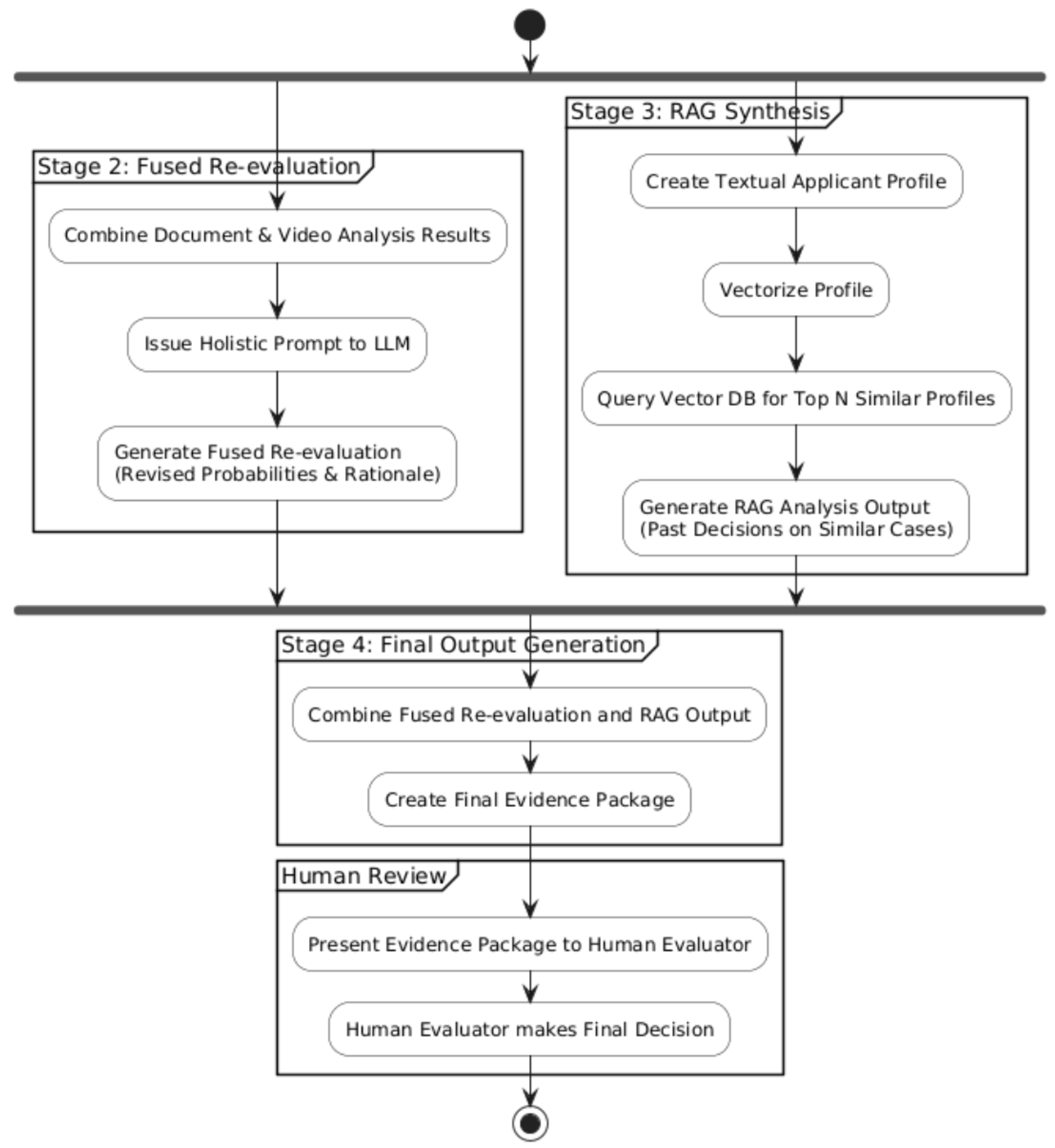

The final stage of the FAIR-VID framework brings together all previously processed modalities—documents, audio, and video—into a unified decision-support architecture. The objective of the fusion architecture is to synthesize multimodal signals into a fair and interpretable representation that reflects both quantitative attributes and contextual behavioral evidence. The fusion criteria were defined to prioritize explainability and traceability: document-based evidence provides structural grounding, video-derived cues supply contextual and behavioral signals, and retrieval-augmented responses ensure alignment with prior institutional practice. This phase, shown in

Figure 5, implements a

multimodal data fusion pipeline that integrates document reasoning, video analysis, and historical decision data. The diagram illustrates the downward progression of data, systematically going from raw multimodal inputs in Stages 2 and 3 into a concise, human-readable evidence package in Stage 4. Each stage builds incrementally on the previous one, allowing evaluators to trace how raw inputs influence intermediate summaries and final recommendations. The resulting synthesis is always presented to a human evaluator for the final admission decision.

5.1. Transparency and Open Access of Prompts

A fundamental design principle of FAIR-VID is radical transparency in AI reasoning. Because prompt structure directly shapes model behavior, exposing these prompts enables external auditing and facilitates reproducibility. Since LLM behavior is highly sensitive to prompt formulation, documenting these prompts ensures that evaluators understand the assumptions embedded in each reasoning step.

All prompts used across the FAIR-VID system—ranging from document interpretation and video evaluation to multimodal fusion—are version-controlled in a public repository (fair-vid/admission_prompts). This repository allows external experts, auditors, and applicants to inspect exactly what the AI was asked to do. The prompt content, structure, and evaluation criteria can thus be publicly scrutinized and improved, aligning with the transparency and human-oversight principles emphasized in the EU AI Act.

By treating prompts as institutional policy artifacts rather than internal parameters, FAIR-VID makes the AI evaluation process open, contestable, and auditable—core expectations for trustworthy AI deployment in high-risk domains such as admissions and HR management.

5.2. Local vs. Cloud Agents

Fusion requires careful handling of sensitive versus depersonalized data, which motivates a split between local and cloud computation. The FAIR-VID design explicitly distinguishes between two categories of AI agents:

the Local AI Agent, operating within institutional infrastructure and authorized to access personal or sensitive data, and

the Cloud AI Agent, which performs advanced reasoning only on fully depersonalized or synthetic data.

This architectural division establishes a privacy boundary that ensures personal identifiers remain under institutional control while still enabling advanced cloud-based reasoning. The local AI agent performs multimodal fusion using actual applicant data (documents, audio, and video) and then depersonalizes the intermediate representations—removing names, identifiers, and contextual details—before sending general analytical requests to the cloud AI agent. The cloud AI agent thus receives only abstract or anonymized descriptions, ensuring that no personally identifiable data ever leave the institution.

This architecture satisfies several key obligations outlined in the EU AI Act. In particular, it supports proportionality, documentation, and explicit human oversight—requirements that are central for systems operating in high-risk admission contexts:

Data governance and protection: Personal data remain local, under institutional control.

Transparency and documentation: Prompts and system behavior are documented for external review.

Human oversight: A human administrator remains responsible for all final decisions.

Proportionality and risk mitigation: High-risk processing (e.g., profiling or ranking) is restricted to verified local environments.

5.3. Stage 1—Holistic Document Analysis

The fusion process begins with text-based materials, as these typically contain the most complete evidence about an applicant’s academic background. The first stage of the fusion pipeline conducts a comprehensive analysis of all textual materials submitted by the applicant—academic transcripts, CVs, certificates, and application forms. This ordering reflects an empirical trade-off: document-level reasoning offers the most complete and reliable evidence base, allowing later stages to refine rather than replace the initial assessment. All pre-processed document content is merged into a unified text block, enabling the model to reason holistically across credentials, summaries, and supporting statements.

In this step, the Local AI Agent has access to the complete, context-rich data, including personal identifiers, document metadata, and prior institutional records. This allows document-level reasoning to incorporate details that cannot be shared with the cloud agent, such as personal identifiers or institution-specific metadata. Local AI Agent uses this information to generate an internally consistent assessment of the applicant’s academic and professional potential. The model is guided by a transparent prompt template, publicly available in the fair-vid/admission_prompts repository, to ensure accountability and reproducibility. A representative example of such a prompt is (Prompt example):

You are an expert university admissions evaluator. Below is a student’s full application description and supporting documents.

{combined_text}

Based on this information, estimate the student’s probability (from 0 to 100%) of being accepted for a scholarship at universities of three different global ranking levels:

Top 10 global university; Around rank 100; Around rank 500.

For each category, provide:

- -

A numerical probability (integer 0–100)

- -

A short list of reasons (2–3 concise bullet points) explaining your evaluation.

Respond only with a valid JSON object.

The output from this local evaluation forms a structured, machine-readable JSON document that quantifies the applicant’s likelihood of acceptance at different institutional tiers.

Before sharing outputs externally, the Local AI Agent removes all identifying attributes and rewrites the profile into an abstract description that preserves structure but not identity. The depersonalization process removes names, identifiers, and any contextual markers, transforming the data into a hypothetical applicant profile—for example, “a student with high mathematics grades, average English proficiency, and two international certificates.” The Cloud AI Agent then reasons only about this generalized, anonymized profile. It produces broad interpretive insights, such as typical scholarship probabilities for similar academic patterns, without ever accessing personal or institutional data.

This division of responsibilities establishes a privacy-preserving hierarchy: the Local AI Agent performs fine-grained reasoning with access to all data, while the Cloud AI Agent contributes generalized analytical reasoning based solely on synthetic, context-neutral representations. This design both upholds the transparency and human-oversight principles of the EU AI Act and ensures that FAIR-VID’s decision-support process remains interpretable, reproducible, and ethically compliant.

5.4. Stage 2—Fused Re-Evaluation with Video Analysis

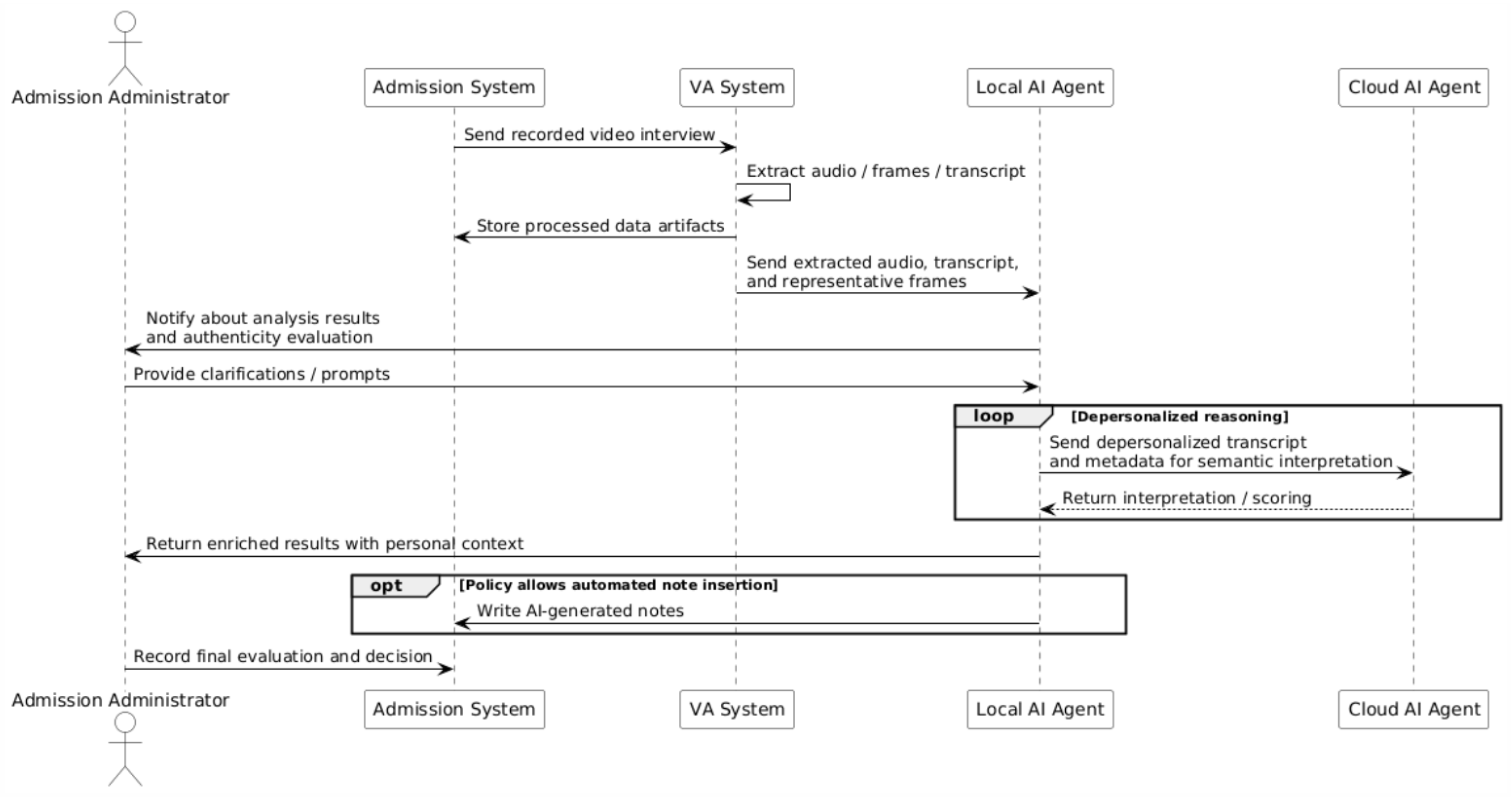

The second fusion stage incorporates audiovisual information to refine or contextualize the document-based assessment. In the second stage, the results of the video interview analysis (from

Section 4) are integrated with the document-based evaluation. Video-derived cues—such as prosodic features, communication style, and authenticity indicators—are integrated with the document assessment to form an enriched intermediate representation. The combined dataset is then submitted to the local AI agent through a fused holistic prompt, prompting the model to re-evaluate the applicant in light of multimodal evidence.

This phase enables context-aware adjustment: strong written credentials may be reconsidered if the video reveals low engagement or inconsistencies, whereas a modest application may gain strength through confident and authentic communication. This step is particularly important for distinguishing strong applicants with weak documentation from those whose written credentials overstate performance.

5.5. Stage 3—Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) Synthesis

To ensure that the fused profile is interpreted consistently with prior institutional practices, FAIR-VID supplements model reasoning with retrieval-based evidence. Running in parallel, the RAG subsystem grounds the AI’s reasoning in institutional precedent. The fused profile is embedded into a vector space and matched against historically similar cases, retrieving the most relevant prior decisions. The top-N most similar cases and their historical outcomes are retrieved to provide an empirical benchmark for comparison.

In the current implementation, all historical outcomes used for similarity-based retrieval are derived exclusively from human-made admission decisions recorded in previous admission cycles. These outcomes reflect the institution’s standard evaluation procedure and include only the binary admission result (offer granted or denied), without incorporating later academic performance. Relying on human-generated decisions prevents the retrieval mechanism from recycling FAIR-VID’s own predictions, thereby avoiding recursive feedback loops. Nevertheless, if institutions later adopt FAIR-VID-generated recommendations in operational practice, accumulated decisions may gradually incorporate model influence. We acknowledge this as a potential source of recursive bias and recommend periodic auditing and recalibration of the historical database. The RAG component is therefore intended solely as a reference tool for contextualizing cases, supporting both the reinterpretation of past decisions and the identification of decisions that should not be used in downstream model training.

This mechanism enforces consistency and fairness over time, aligning with the EU AI Act’s emphasis on traceability and risk monitoring. However, the quality of these comparisons depends on the representativeness of the historical dataset, which is an acknowledged limitation in early-stage deployments. The RAG output includes descriptive summaries of comparable applicants and how their cases were resolved, giving evaluators a transparent view of how the current assessment fits within established patterns.

5.6. Stage 4—Final Output Generation and Human Review

The final stage consolidates all intermediate results into a form that supports human review and regulatory compliance. This stage (

Figure 5, Stage 4) fuses the outputs of the re-evaluation and RAG modules into a single evidence package. The resulting evidence package contains:

Updated scholarship probabilities and rationale;

A list of comparable past applicants and decisions;

Supporting extracts from documents, transcripts, and video metrics.

This package is presented to the admission administrator, who performs the ultimate evaluation and records the decision in the admission system. The human-in-the-loop review ensures compliance with the EU AI Act’s human oversight and accountability principles. The AI thus acts as an assistant that aggregates and contextualizes evidence rather than a decision-maker, ensuring that fairness, transparency, and privacy remain central to every stage of the multimodal assessment. The fused evidence produced by this stage forms the basis for the experiments and evaluation presented in

Section 6.

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the reliability and generalization capacity of the FAIR-VID visual document understanding pipeline, we conducted a controlled experiment comparing two model configurations:

Gemma 3 (27B)—a large multimodal model operating in zero-shot mode;

LayoutLMv3 Base—a layout-aware transformer utilizing OCR input for spatial reasoning.

Both models were assessed on an identical test set of standardized International English Language Testing System (IELTS) certificates, chosen due to the global uniformity of their format and field structure (candidate name, overall score, date, and issuing center). This standardization allowed for precise benchmarking of extraction accuracy and error analysis under real document conditions.

6.2. Model Performance on Standardized IELTS Certificates

Each certificate image was processed independently, and outputs were evaluated against manually verified ground-truth annotations. Correct extraction required exact textual and field-level accuracy (e.g., numerical scores, names, and dates).

The Gemma 3 (27B) model achieved near-perfect accuracy, with only one document misclassified out of the entire test set. In contrast, LayoutLMv3 produced three erroneous extractions, primarily related to OCR boundary misalignment and missing diacritical marks in candidate names (see

Table 1).

The results clearly demonstrate that document regularity strongly influences extraction accuracy. On the highly standardized IELTS certificates, Gemma 3 delivered nearly flawless zero-shot performance, confirming the model’s capability to generalize spatial and textual understanding without fine-tuning. The small number of errors observed in LayoutLMv3 highlights the limitations of OCR-dependent architectures when field boundaries or typography vary slightly, even in uniform documents.

When tested on a random set of international academic documents of the same size, Gemma 3’s error count increased to four, corresponding to 80% overall accuracy. This decline reflects the model’s sensitivity to unfamiliar layouts and unstructured text, emphasizing that robust generalization still benefits from limited domain adaptation. LayoutLMv3 was not evaluated on the random set due to the significant manual effort required to prepare OCR-aligned annotations—a known scalability limitation of layout-aware models.

Collectively, these findings validate the decision to employ Gemma 3 as the primary inference model within the FAIR-VID visual analysis pipeline. Its superior accuracy on standardized formats, minimal dependency on explicit OCR, and reduced data-annotation requirements make it the most practical solution for international admission workflows. At the same time, maintaining an OCR-based verification branch remains valuable for explainability, allowing bounding-box visualization of key fields in high-risk or ambiguous cases.

For the IELTS Certificate evaluation, accuracy was computed at the document level, defined as the proportion of certificates for which all required fields were extracted correctly. Each certificate was treated as a single evaluation unit because IELTS documents follow a standardized layout with a small, fixed number of fields, making field-level weighting unnecessary for this dataset. Accordingly, the metric does not distinguish between cases where two errors occur in a single certificate versus two errors distributed across two certificates; what matters for downstream use is whether a complete document can be reliably parsed. We acknowledge that the sample size of 20 certificates is limited and therefore interpret the results as exploratory rather than conclusive. The intent of this experiment is to illustrate the behavior of different model configurations under real-world constraints rather than to establish statistical superiority. This limitation reflects an important practical challenge in international admissions: institutions often receive very small numbers of examples for many certificate types across different countries, making it infeasible to develop large, high-quality training sets for layout-based models such as LayoutLMv3. In such settings, zero-shot multimodal LLMs provide a more practical and scalable alternative, while layout-aware verification remains valuable only where regulatory or transparency requirements necessitate explicit spatial grounding.

6.3. Predictive Modeling Experiments on Multimodal Admission Data

To quantify the contribution of multimodal analysis to predictive modeling in university admissions, we evaluated the proposed FAIR-VID framework on 5400 anonymized foreign student applications obtained from the admissions system. Each record included structured form data, uploaded supporting documents, and, for a subset of cases, video interview recordings processed through the FAIR-VID video pipeline.

For each application, a binary success variable was defined for three consecutive stages of the admission workflow:

Experiment 1—Fee Payment Prediction: Identifies applicants who complete the initial registration fee payment after document submission.

Experiment 2—Offer Prediction: Estimates the probability of receiving an admission offer, tested in two configurations:

without video data, using only structured and document features;

with integrated video–audio data from the FAIR-VID video pipeline.

Experiment 3—Enrollment Prediction: Predicts final enrollment after offer acceptance, incorporating behavioral interaction data (e.g., login frequency, payment timing).

Each task was modeled as a binary classification problem (success = 1, failure = 0). For Experiment 2 (Offer Prediction), the binary outcome corresponds to the actual admission offers issued by human admissions officers through the standard institutional evaluation process. The FAIR-VID pipeline was not involved in generating these decisions; it was used exclusively to produce predictive features for analytical purposes. Thus, the experiment assesses the extent to which the pipeline can approximate historical human judgments rather than predict outcomes of its own automated process. Data were partitioned using an 80/20 train–test split, and results were averaged across five randomized folds to ensure stability. Precision and recall were used as the primary evaluation metrics to capture the balance between predictive specificity and completeness, with the full performance summary presented in

Table 2.

Experiment 1—Fee Payment Prediction. Early-stage application completeness and metadata consistency emerged as strong behavioral indicators. Applicants who provided all required credentials and adhered to the upload instructions were significantly more likely to complete the payment process. The resulting model achieved precision = 0.83 and recall = 0.79, effectively distinguishing compliant from uncertain or potentially fraudulent profiles.

Experiment 2—Offer Prediction. The introduction of video and audio modalities demonstrated clear performance gains. Without video features (Exp. 2a), the model achieved precision = 0.85 and recall = 0.82. When multimodal embeddings (Whisper-transcribed speech and Gemma 3-derived semantic representations) were added (Exp. 2b), both metrics improved by approximately 6 percentage points. This confirms that paralinguistic and visual cues—such as fluency, emotional tone, and authenticity—enhance evaluative robustness.

Experiment 3—Enrollment Prediction. The final stage integrated all available modalities, including behavioral activity logs. The model achieved precision = 0.87 and recall = 0.84, indicating stable predictive performance. However, these results also reflect the limits of algorithmic predictability, as external variables such as visa approval or financial circumstances introduce significant variance beyond the model’s scope.

Overall, the experiments confirm that multimodal fusion significantly improves the reliability of predictive admission modeling, particularly when incorporating video interview data. The results validate FAIR-VID’s design principles: (a) the complementary use of structured and unstructured data streams, (b) interpretable AI through modular pipelines, and (c) the preservation of human oversight. These findings provide empirical support for the project’s emphasis on transparent, explainable, and regulation-aligned AI in international admissions.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper introduced FAIR-VID, a transparent and regulation-aligned framework that integrates document understanding, video analysis, and multimodal fusion into a coherent human-in-the-loop system. By combining two-phase video preprocessing with AI-driven document interpretation, FAIR-VID establishes a pipeline capable of converting heterogeneous raw data into interpretable, structured, and ethically auditable representations.

A defining feature of the project is its commitment to transparency and reproducibility. All major pipeline components, including document parsing, video deconstruction, visual enrichment, and multimodal fusion, are implemented as a set of Google Colab notebooks. These notebooks are openly accessible and fully executable, enabling researchers, educators, and policymakers to inspect, replicate, and extend every stage of the process. This open-source design ensures that FAIR-VID is not merely a technical framework but also an important research infrastructure that promotes accountability and community-driven innovation in AI-assisted profiling.

From an ethical and legal standpoint, the FAIR-VID architecture explicitly separates Local AI Agents, which process sensitive or identifiable data, from Cloud AI Agents, which operate only on synthetic or depersonalized inputs. This design operationalizes compliance with the EU AI Act and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), demonstrating how advanced AI reasoning can coexist with strict privacy protection and auditability requirements.

Future work will build on this foundation by extending multimodal learning to incorporate all available data streams—audio, transcript text, visual frames, and AI-generated descriptions—for semi-supervised fraud detection and holistic applicant assessment. In parallel, upcoming research will focus on benchmarking fairness and interpretability metrics across demographic and linguistic groups and developing shared evaluation datasets for reproducible research in ethical admissions AI. Through open collaboration and verifiable experimentation, FAIR-VID aims to foster a more transparent, fair, and community-governed future for AI-supported decision systems in higher education.

In addition to these broader research directions, further development of the document analysis component will investigate a transition from the current hybrid architecture toward more compact and energy-efficient end-to-end models, such as Donut-style OCR-free transformers. As the system accumulates a wider range of verified credentials, such models may become increasingly advantageous due to reduced annotation requirements and shorter inference times. At the same time, a layout-aware verification branch will be retained for cases that require explicit spatial grounding or compliance-oriented auditability. This evolution aims to balance scalability, transparency, and computational efficiency as the pipeline is adapted for large-scale and heterogeneous international admissions contexts.