Gas-Liquid Flow of R290 in the Integrated Electronic Expansion Valve and Vapor Injection Loop for Heat Pump

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model and Verification

2.1. Geometrical Model

2.2. Governing Equations for Gas-Liquid Flow

2.2.1. Multiphase Flow Model

2.2.2. Phase Change Mechanism

2.3. Numerical Simulation Setup

2.4. Validating the Evaporation Coefficient Through Experiment

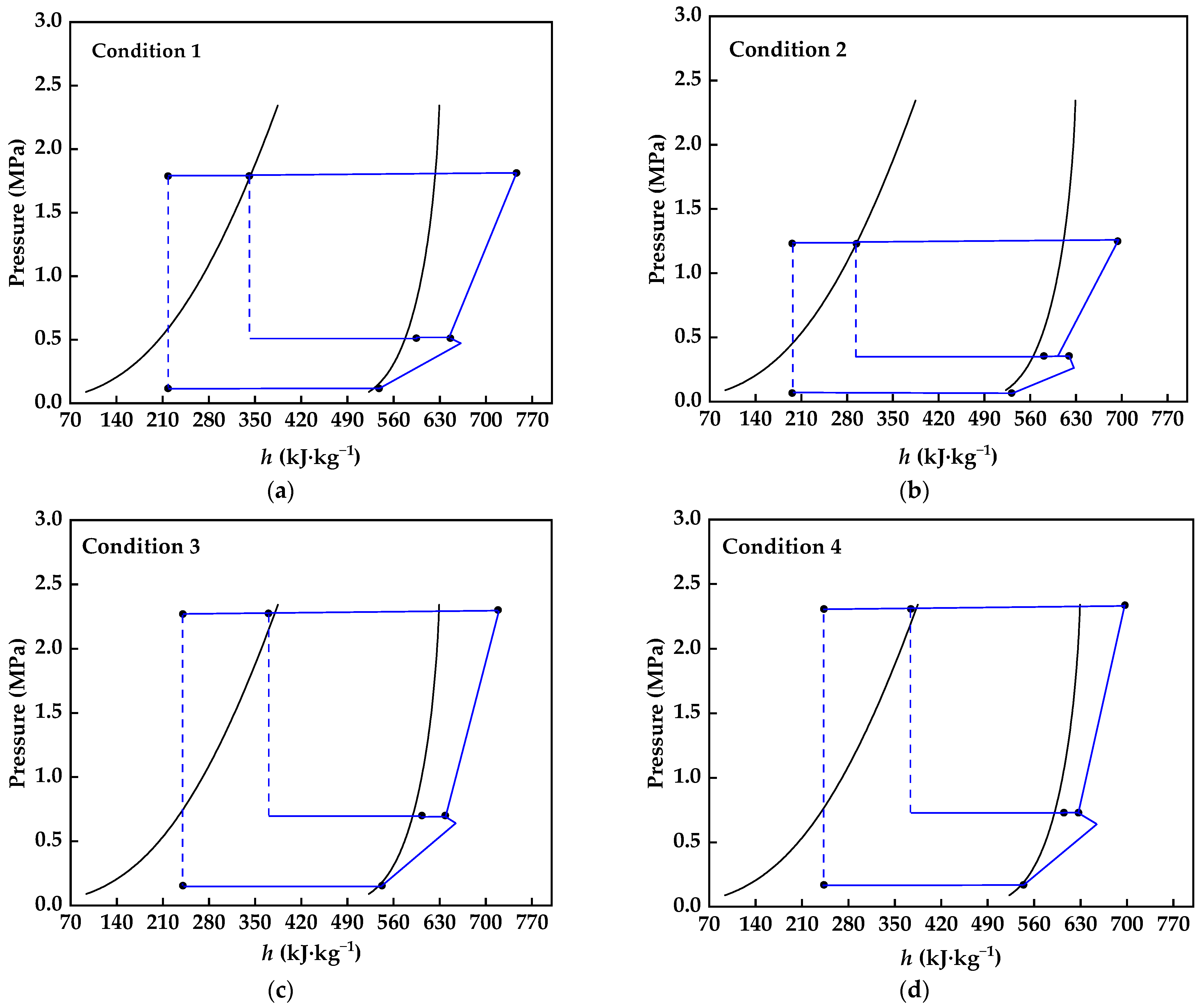

2.4.1. Test System and Conditions

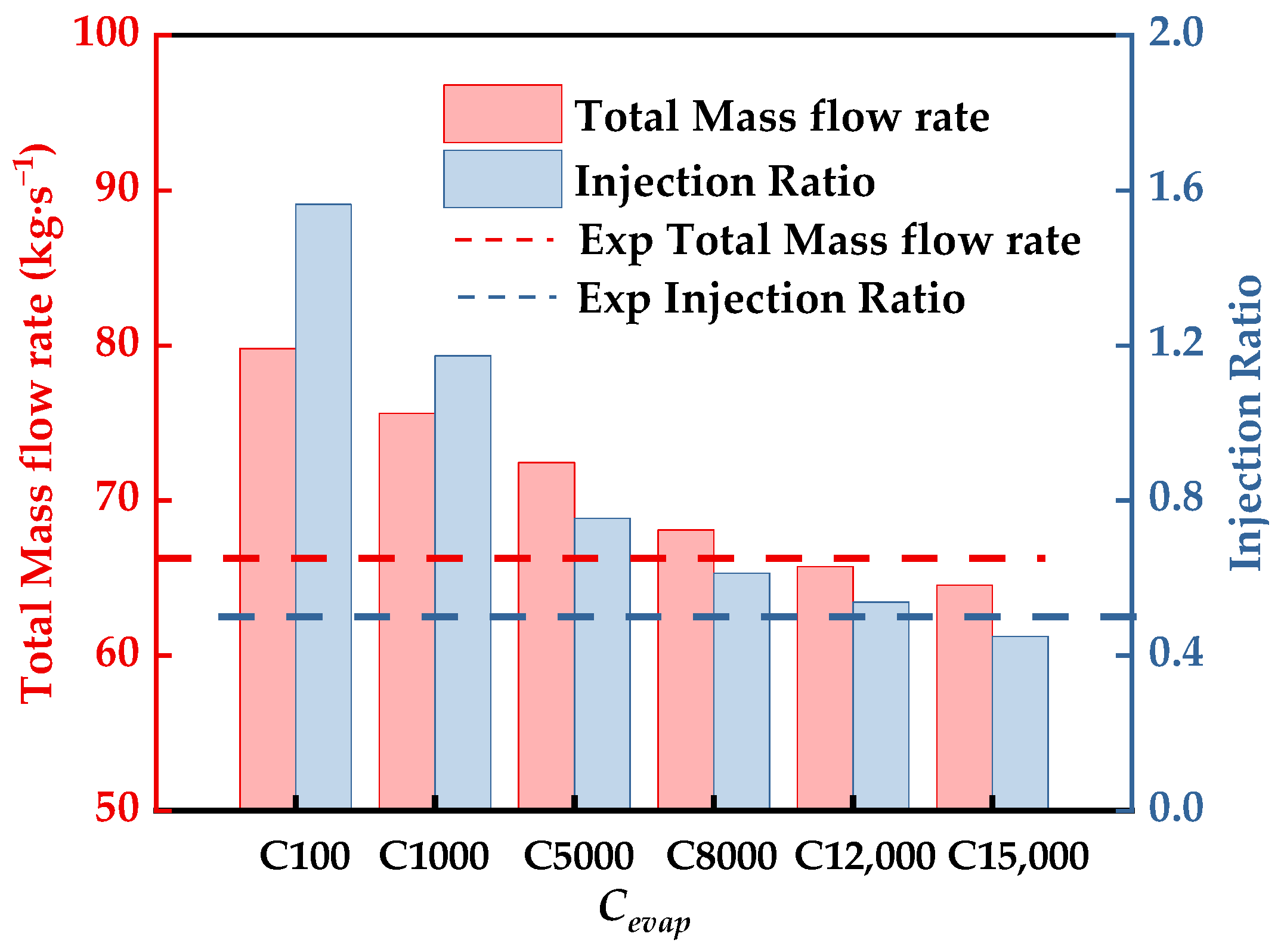

2.4.2. Determination of the Evaporation Coefficient (Cevap)

3. Results and Discussion

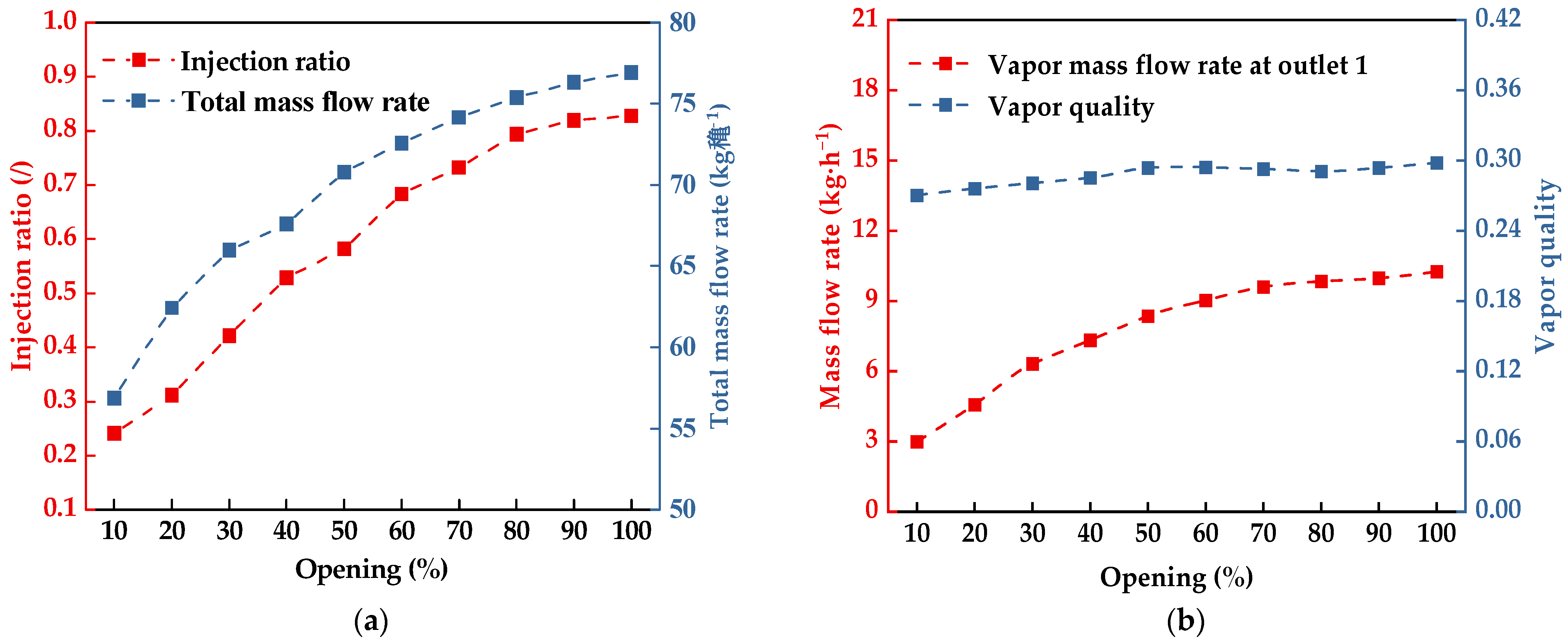

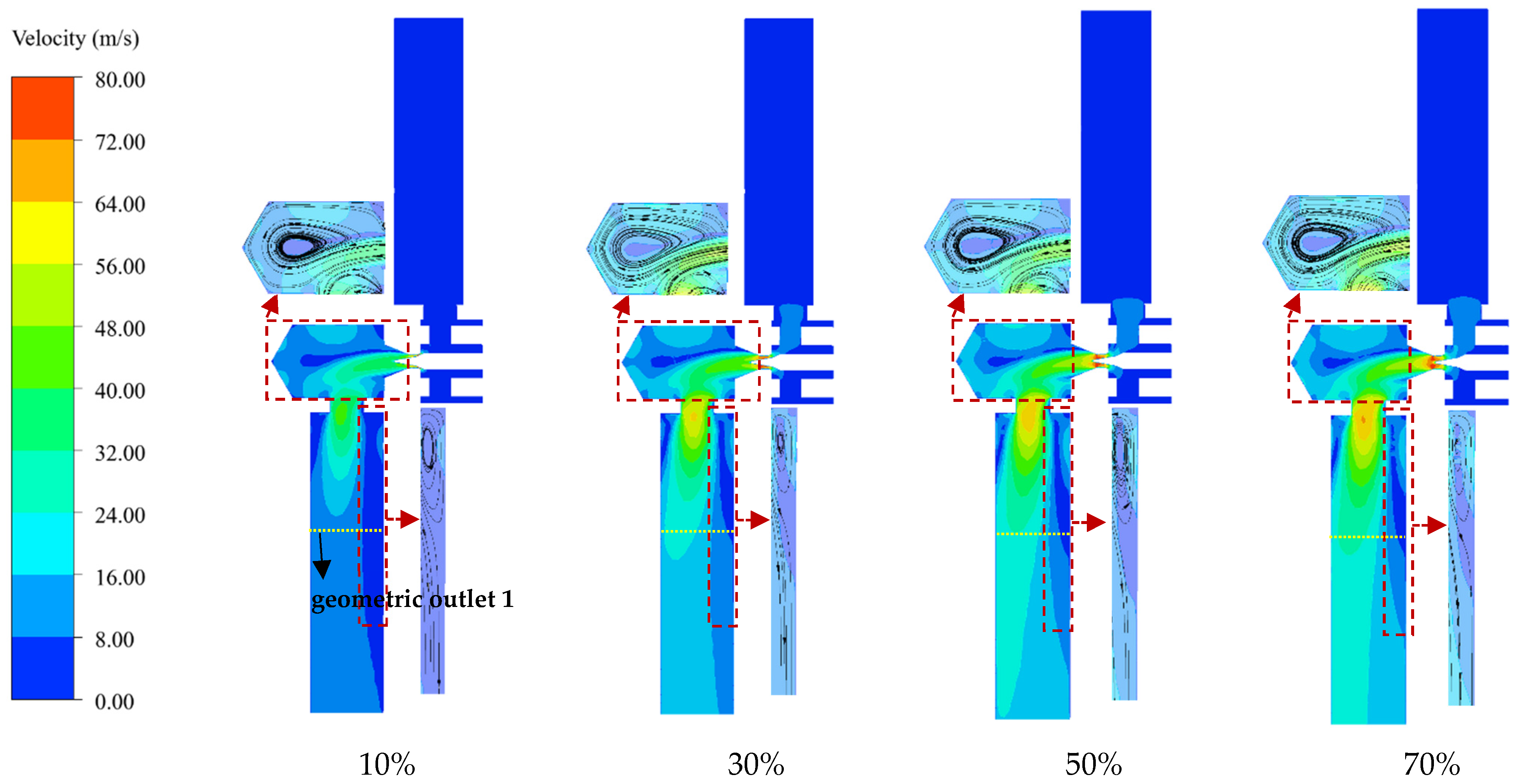

3.1. Analysis of Influencing Factors on the Injection Ratio

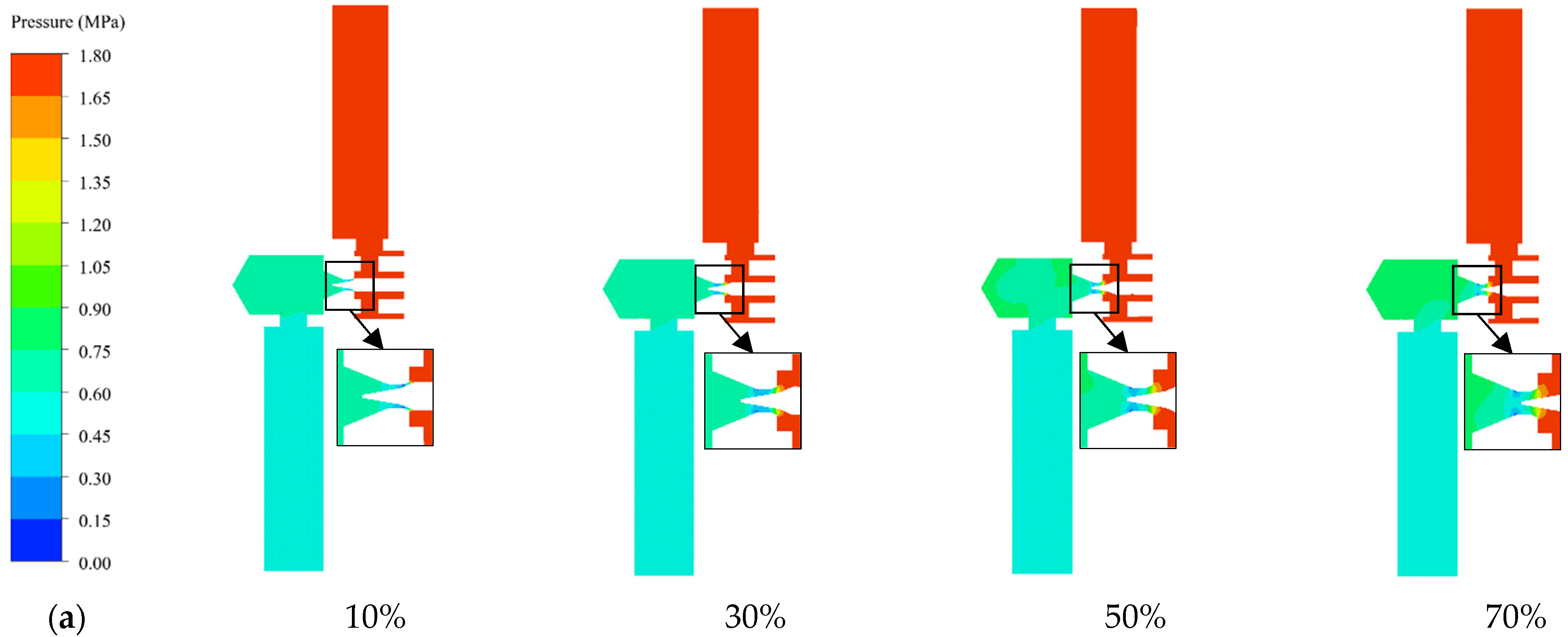

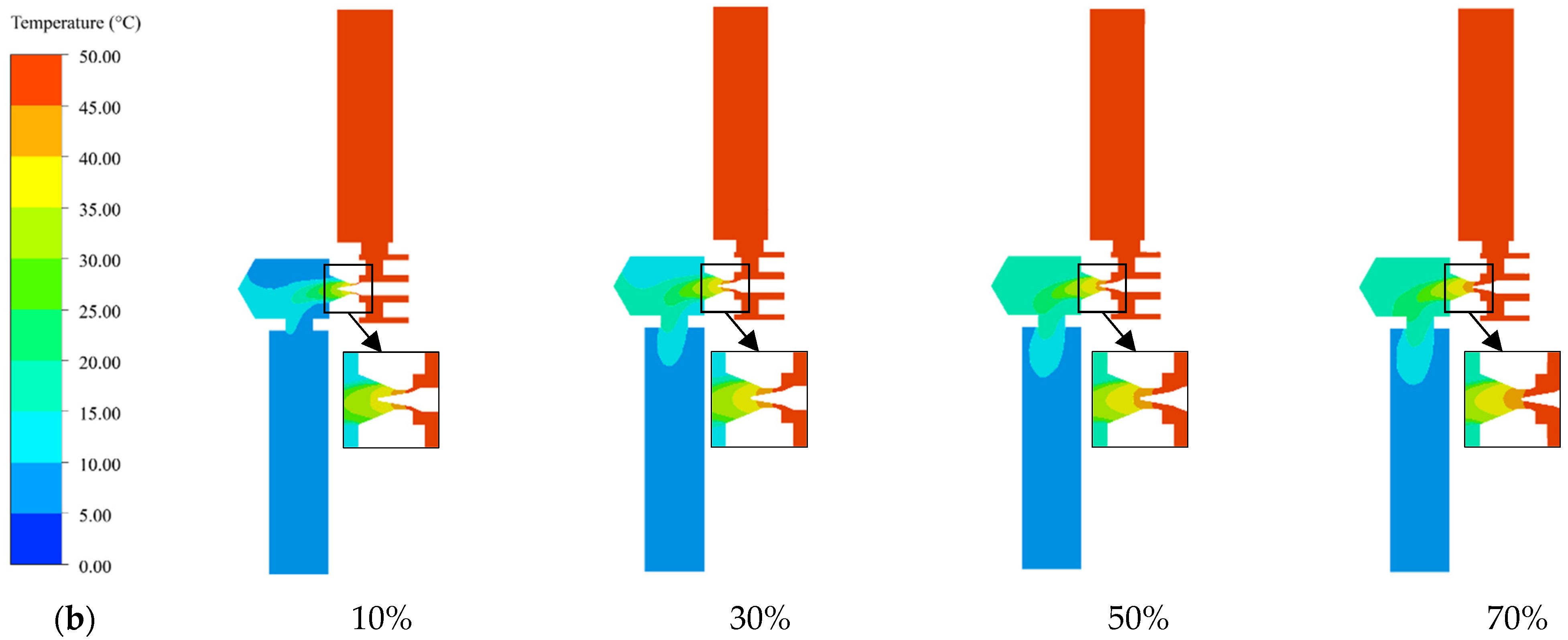

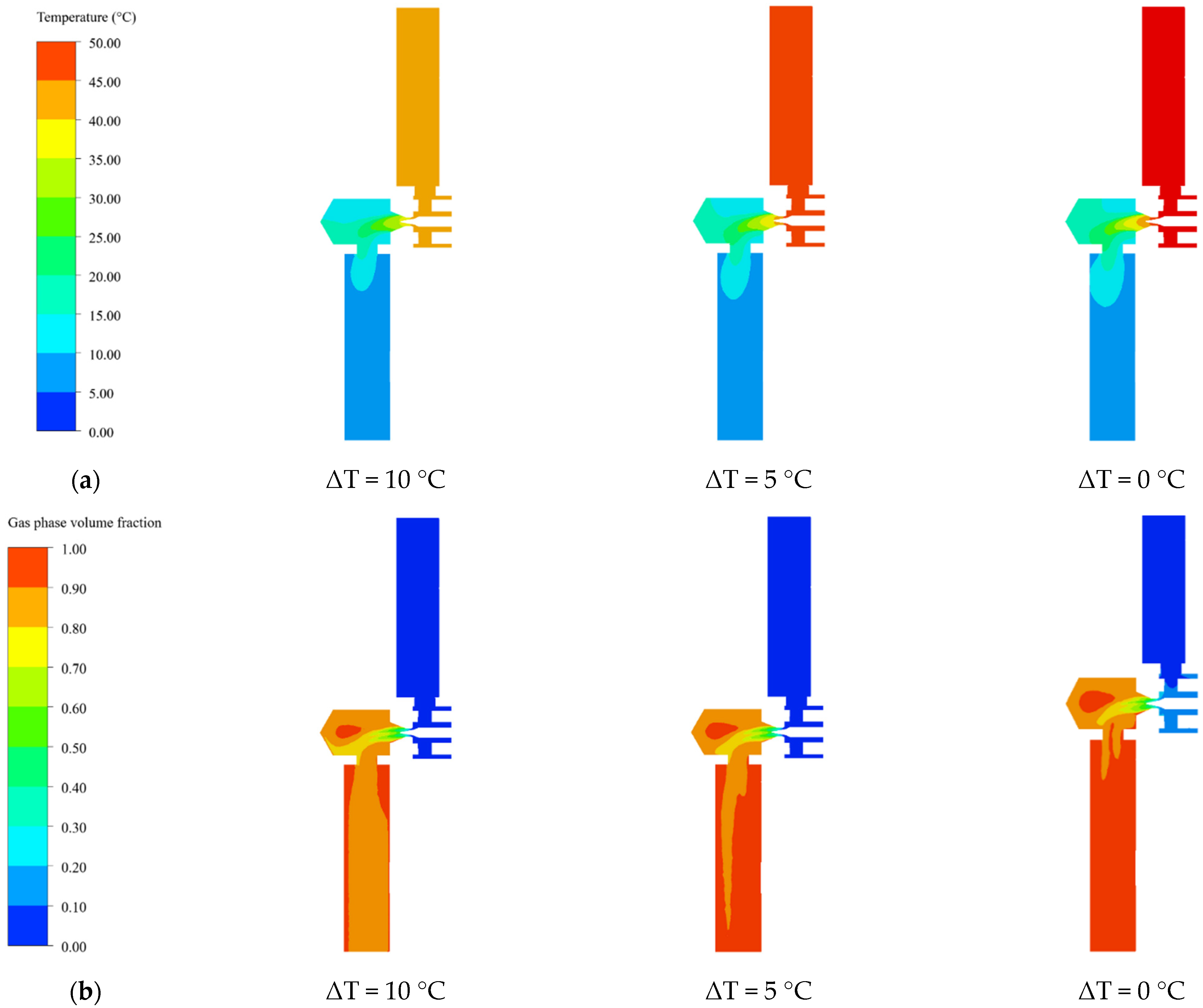

3.2. Pressure and Temperature in the VPI-EXV

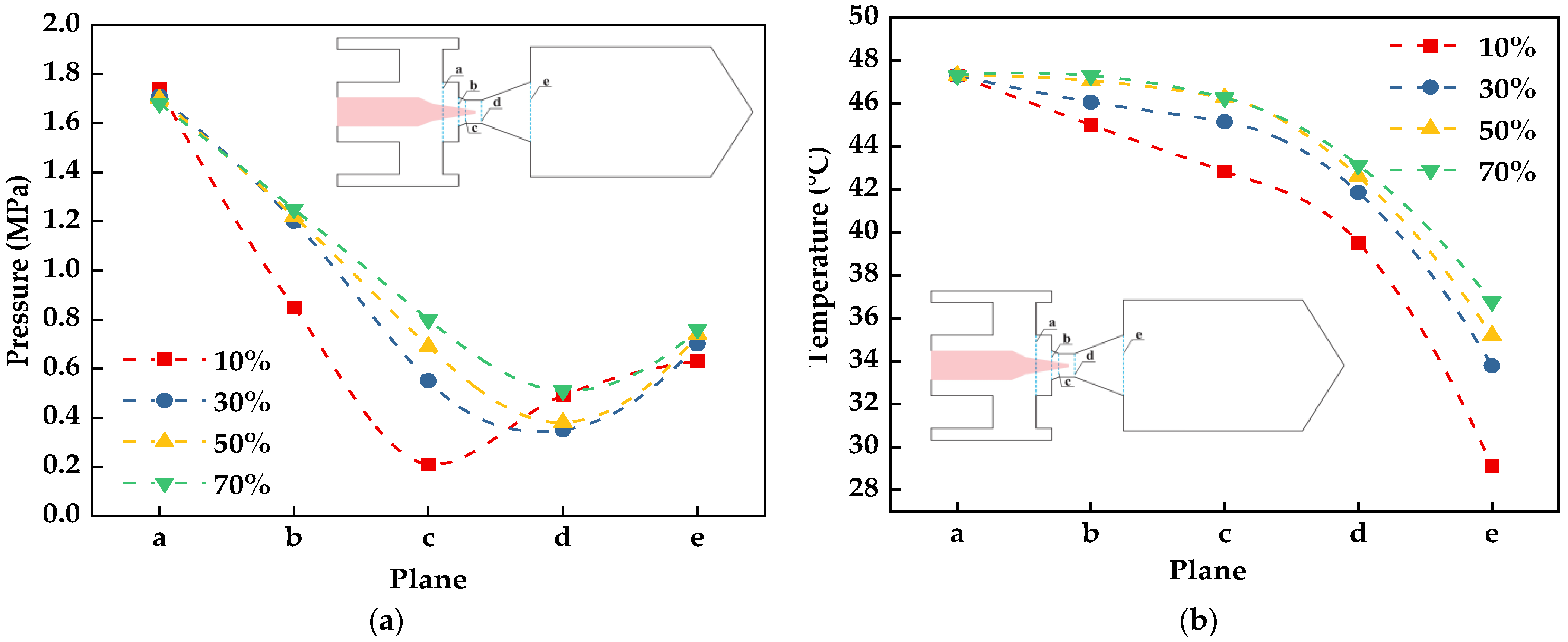

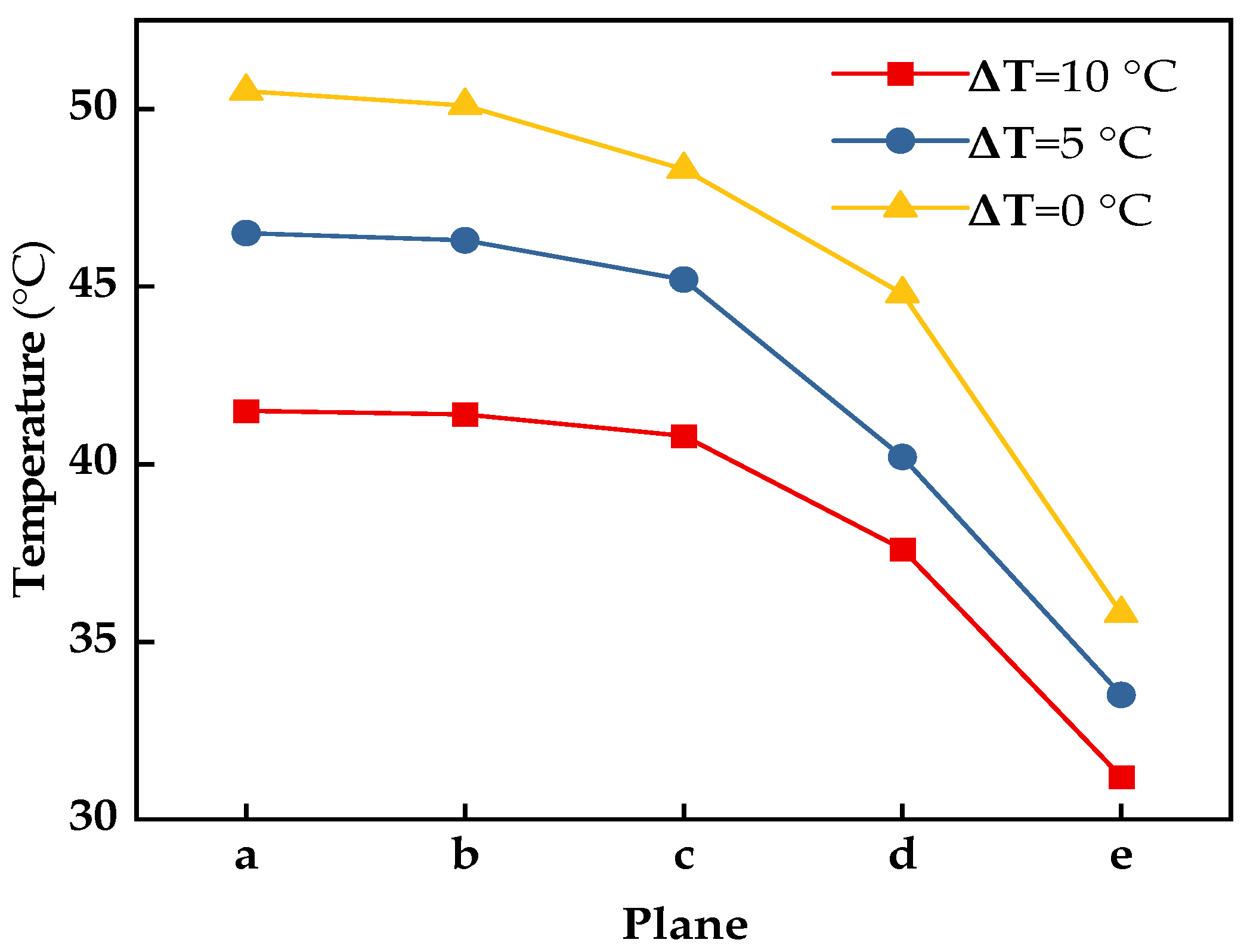

3.3. Gas-Liquid Flow at Different Subcooling

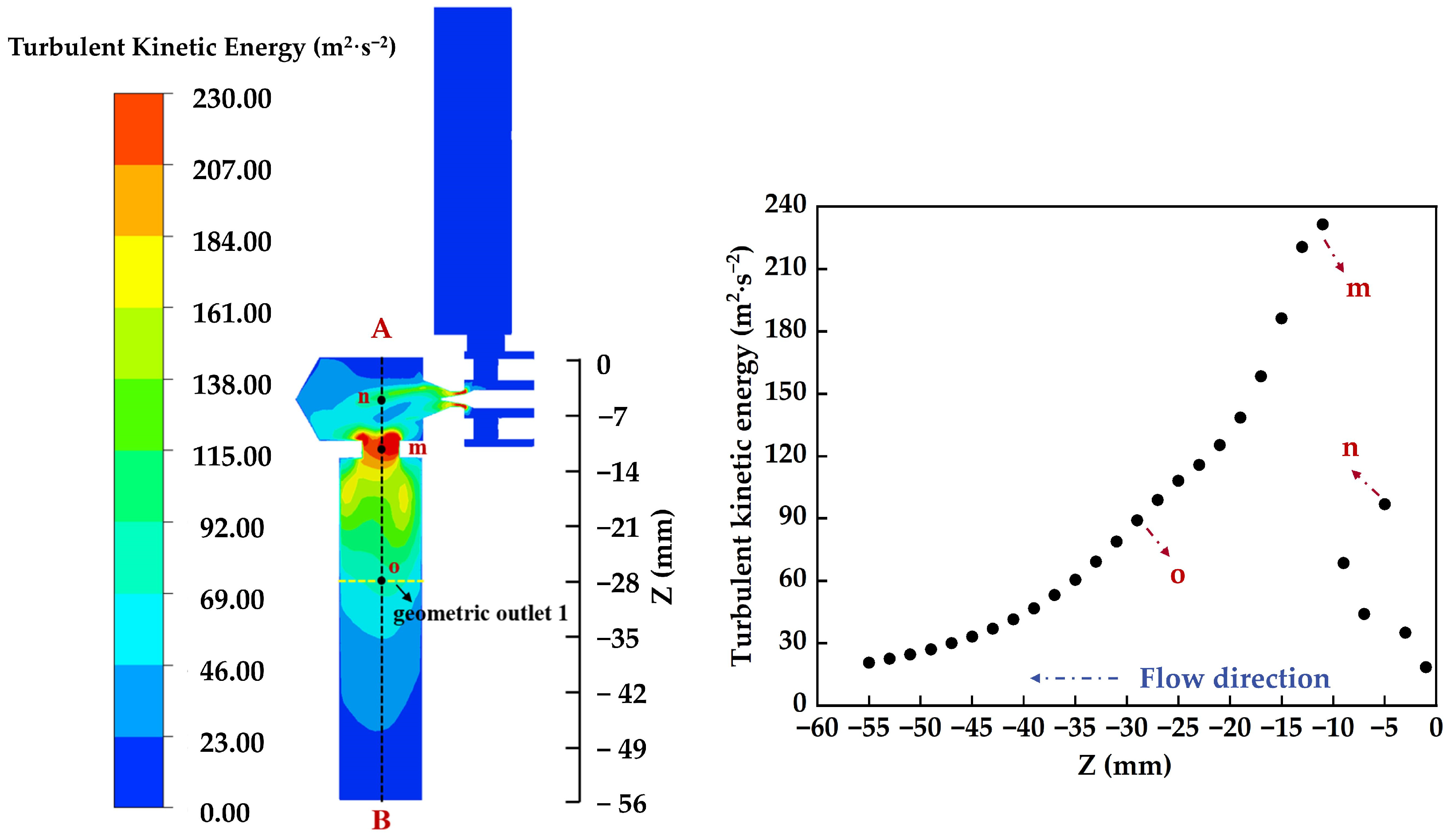

3.4. Turbulent Kinetic Energy in the Novel Throttling Section

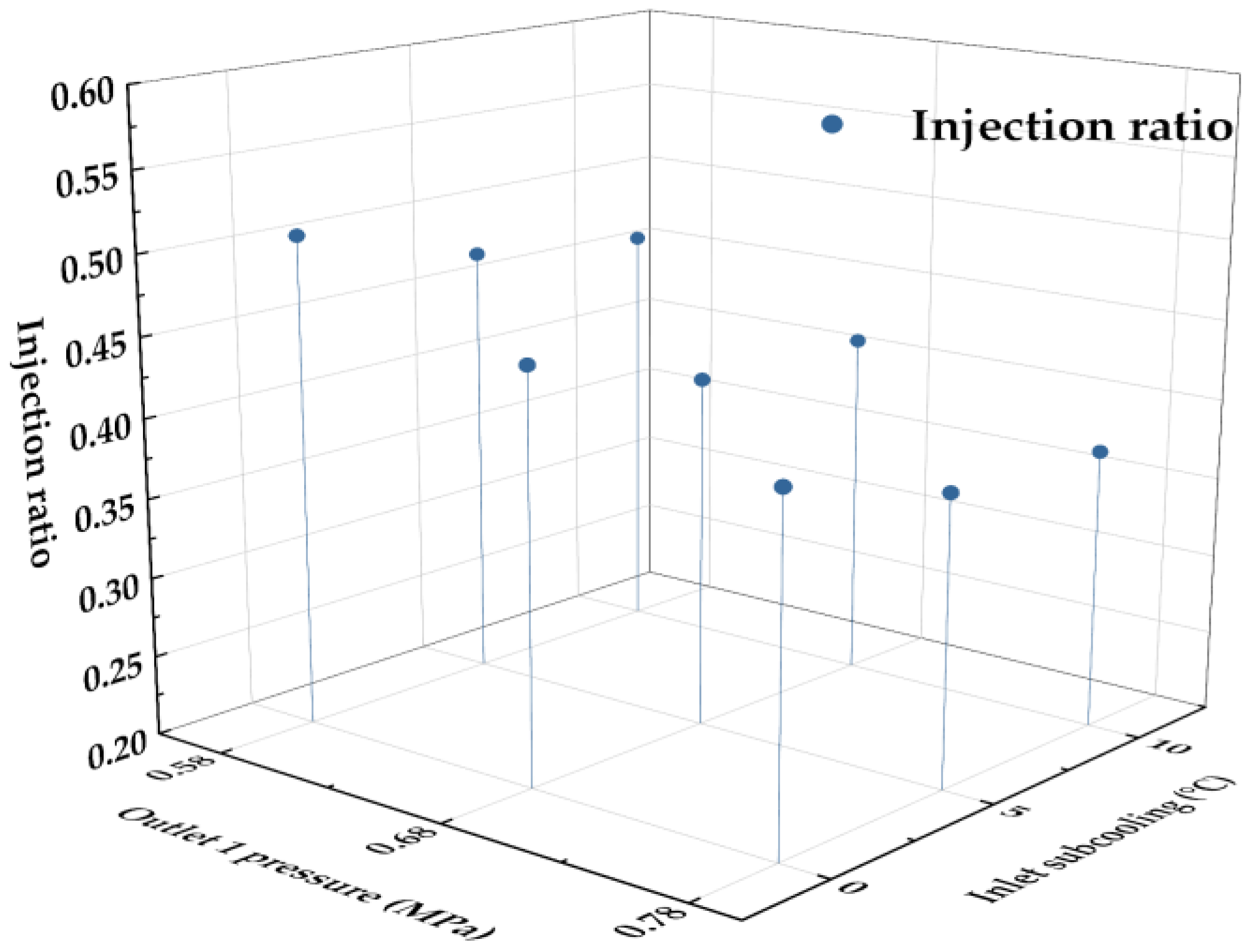

3.5. Orthogonal Analysis of Factors Affecting the Injection Ratio

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, J.; Kim, J.; Eom, S.; Lee, J.; Chu, Y.; Kim, J.; Choi, S.; Choi, M.; Choi, G.; Park, Y. Study on the refrigerant interchangeability under extreme operating conditions of R1234yf heat pump systems for electric vehicles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 245, 122789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Jeon, Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y. Numerical study of the effects of injection-port design on the heating performance of an R134a heat pump with vapor injection used in electric vehicles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 127, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.H.; Fauzan; Hakiem, F.Z.A.; Kim, H.; Park, S.H.; Chang, Y.S. Design and Performance Evaluation of Car Seat Heat Pump for Electric Vehicles. Energies 2025, 18, 6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, H.; Guo, X. Theoretical analysis and experimental research on R1234yf as alternative to R134a in a heat pump system. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2023, 42, e14041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L. Numerical Investigation on Heat Transfer of Supercritical CO2 in Minichannel with Fins Integrated in Sidewalls. Processes 2025, 13, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, D.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, M.; Wang, X. Review of Thermal Management Technology for Electric Vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Bradshaw, C.R. A novel characterization methodology for vapor-injected compressors: A comparative analysis with existing black-box models. Int. J. Refrig. 2025, 169, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ma, J.; Zhang, B.; Su, L.; Liu, N.; Zhang, H.; Dou, B.; He, Q.; Zhou, X.; Tu, R. Experimental study on low temperature heating performance of different vapor injection heat pump systems equipped with a flash tank and economizers for electric vehicle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 227, 120428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shao, W.; Yang, T.; Zou, H.; Tian, C. Performance analysis of an R290 vapor-injection heat pump system for electric vehicles in cold regions. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2024, 67, 3673–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y. Performance Research on Heating Performance of Battery Thermal Management Coupled with the Vapor Injection Heat Pump Air Conditioning. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Cho, H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, Y. Mass flow characteristics and empirical modeling of R22 and R410A flowing through electronic expansion valves. Int. J. Refrig. 2007, 30, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeng, H.; Kim, J.; Kwon, S.; Kim, Y. Energy and environmental performance of vapor injection heat pumps using R134a, R152a, and R1234yf under various injection conditions. Energy 2023, 280, 128265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, L.; Qin, X.; An, T.; Zhao, C. Influence of electronic expansion valve on heating performance of vehicle heat pump system. Therm. Sci. 2023, 27, 1819–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zou, H.; Tang, M.; Tian, C.; Yan, Y. Comprehensive study on EEVs regulation characteristics of vapor-injection CO2 heat pump for electric vehicles. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 149, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Kim, M.K.; Jeong, J.H. Development of refrigerant flow rate correlation for electronic expansion valve using valve flow coefficient. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 227, 120324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Li, Z.-Y.; Shao, L.-L.; Zhang, C.-L. Refrigerant flow through electronic expansion valve: Experiment and neural network modeling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 92, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, A.; Gong, Z.; Chen, T.; Al-Bukhaiti, K. Mass flow characteristics prediction of refrigerants through electronic expansion valve based on XGBoost. Int. J. Refrig. 2024, 158, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Hua, H.; Zhang, D.; Li, Z.; Tao, W.-Q. Numerical investigation of refrigerant flashing flow in electronic expansion valves. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2025, 114, 109827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Li, L.; Shangguan, W.-B. Numerical Investigation on the Internal Flow Field of Electronic Expansion Valve as the Throttle Element. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Pract. Mobil. 2022, 4, 1931–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Wu, C.J.; Wang, D.H. Study on the Flow and Acoustic Field of an Electronic Expansion Valve under Refrigeration Condition with Phase Change. Shock Vib. 2022, 202, 6714925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Song, Y.X.; Liu, J.T.; Zhang, L.H. Research on the characteristics of two-phase flow-induced noise in the cavitation dynamics of electronic expansion valves. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 013310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Jiang, M.; Ran, X.; Xuan, L.; He, Y. Numerical and experimental study on cavitation and noise characteristics of electronic expansion valve. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ji, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lin, H. Experimental study of propane heat pump system with secondary loop and vapor injection for electric vehicle application in cold climate. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 217, 119196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Wang, H.; Fu, M.; Lin, C.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, Y. Experimental study of the integrated vapor injection R1234yf electric vehicle heat pump system in cold conditions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 270, 126214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhifang, X.; Lin, S.; Hongfei, O. Refrigerant flow characteristics of electronic expansion valve based on thermodynamic analysis and experiment. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsson, J.E. An Introduction to ANSYS Fluent 2022; Sdc Publications: Mission, KS, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Lucas, D. Computational modelling of flash boiling flows: A literature survey. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 111, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Shi, X.; Qian, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, Q. Numerical Simulation on BLEVE Mechanism of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaraman, S.; Makarov, D.; Molkov, V. Flash boiling and pressure recovery phenomenon during venting from liquid ammonia tank ullage. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 182, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.K.; Bose, S.; Patle, S.D. Comparison of the performance of propane (R290) and propene (R1270) as alternative refrigerants for cooling during expansion in a helical capillary tube: A CFD-based insight investigation. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 146, 300–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molkov, V.; Sivaraman, S.; Cirrone, D.; Truchot, B.; Makarov, D. Modelling and numerical simulations of heat and mass transfer in multiphase flow during the release of liquid ammonia from a storage tank through the piping system to the open atmosphere. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 246, 127097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.R. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, E.W.; Bell, I.H.; Huber, M.; McLinden, M. NIST Standard Reference Database 23: Reference Fluid Thermodynamic and Transport Properties-REFPROP; Version 10.0; Standard Reference Data Program; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, T.; Lu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Yu, J. Numerical study on the structural optimization of R290 two-phase ejector with a non-equilibrium CFD model. Int. J. Refrig. 2025, 170, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X. Numerical simulation study on the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of heat transfer in the static flash evaporation. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 210, 109675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Zhao, H.; Xu, Q.; Li, D.; Chen, Z.; Dong, X. Simulation study on noise reduction effect of porous material on electronic expansion valve. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 151, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, S.; Zhen, J.; Guo, J.; Xu, W. Numerical study and orthogonal analysis of optimal performance parameters for vertical cooling of sintered ore. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.-h.; Pang, K.-g.; Pang, B.-b.; Wang, S. Orthogonal experimental-based thermal management design and simulation optimization of a liquid-cooled battery module. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Lv, D.; Yang, Q.; Liu, G.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L. Energy and exergy analysis of a transcritical CO2 refrigeration system integrated with vapor injection and mechanical subcooling. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2025, 222, 106592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Throat diameter | mm | 1.65 |

| Maximum travel of needle | mm | 3.60 |

| Cone angle | ° | 20.5 |

| Valve needle diameter | mm | 1.82 |

| Operating Condition | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Unit | Value | |||

| Boundary conditions | |||||

| Ambient temp | °C | −20 | −20 | −10 | −10 |

| Compressor speed | rpm | 8500 | 6750 | 8500 | 6750 |

| Refrigerant charge | g | 310 | 310 | 310 | 310 |

| Main EXV opening | % | 15 | 11 | 18 | 16 |

| VPI EXV opening | % | 43 | 82 | 37 | 64 |

| Chiller parameters | |||||

| Evaporate temp | °C | −39.0 | −51.0 | −32.0 | −30.0 |

| Outlet pressure | MPa | 0.116 | 0.067 | 0.154 | 0.170 |

| Outlet temp | °C | −33.3 | −39.4 | −29.0 | −27.5 |

| Compressor parameters | |||||

| Stage2 outlet pressure | MPa | 1.812 | 1.249 | 2.302 | 2.338 |

| Stage2 outlet temp | °C | 104.9 | 74.8 | 98.3 | 89.9 |

| Stage 1 outlet pressure | MPa | 0.582 | 0.322 | 0.681 | 0.721 |

| Stage 1 outlet temp | °C | 40.4 | 22.9 | 39.4 | 33.8 |

| WCC parameters | |||||

| Condense temp | °C | 52 | 36 | 63 | 64 |

| Outlet pressure (Inlet 1 pressure) | MPa | 1.789 | 1.229 | 2.276 | 2.309 |

| Outlet temp (Inlet 1 temp) | °C | 51.3 | 35.3 | 60.5 | 61.7 |

| VPI parameters | |||||

| Inlet press (Outlet 1 pressure) | MPa | 0.582 | 0.322 | 0.681 | 0.721 |

| Injection Inlet temp | °C | 12.0 | 0.6 | 20.7 | 22.3 |

| Main EXV parameters | |||||

| Inlet press (Outlet 2 pressure) | MPa | 1.788 | 1.231 | 2.271 | 2.308 |

| Main EXV inlet temp | °C | 7.0 | −1.8 | 15.5 | 16.5 |

| Mass flow rates | |||||

| Suction mass flow rate | kg·h−1 | 44.2 | 21.2 | 52.4 | 43.8 |

| Total mass flow rate | kg·h−1 | 66.3 | 30.2 | 82.3 | 74.1 |

| Coolant Loop parameters | |||||

| Chiller coolant flow rate | L·min−1 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Chiller coolant inlet temp | °C | −23.8 | −27.4 | −15.4 | −17.2 |

| Chiller coolant outlet temp | °C | −27.0 | −36.9 | −21.5 | −22.6 |

| WCC coolant flow rate | L·min−1 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| WCC coolant Inlet temp | °C | 39.3 | 27.4 | 48.3 | 51.2 |

| WCC coolant outlet temp | °C | 44.7 | 30.2 | 54.8 | 56.6 |

| Cevap | 100 | 1000 | 5000 | 8000 | 12,000 | 15,000 |

| RMSRE [%] | 237.3 | 160.6 | 78.3 | 31.2 | 9.6 | 24.7 |

| Level | Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Valve Opening [%] | Outlet Pressure [MPa] | Inlet Subcooling [°C] | |

| 1 | 30 | 0.5 | 0 |

| 2 | 50 | 0.6 | 5 |

| 3 | 70 | 0.7 | 10 |

| Case | Factors | Simulation Results | Evaluation Index | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valve Opening [%] | Outlet Pressure [MPa] | Inlet Subcooling [°C] | Total Mass Flow Rate [kg·h−1] | Vapor Quality [/] | Injection Ratio [/] | |

| 1 | 30 | 0.5 | 0 | 67.830 | 0.32 | 0.54 |

| 2 | 30 | 0.6 | 5 | 66.975 | 0.26 | 0.46 |

| 3 | 30 | 0.7 | 10 | 65.436 | 0.19 | 0.41 |

| 4 | 50 | 0.6 | 0 | 71.991 | 0.31 | 0.52 |

| 5 | 50 | 0.7 | 5 | 70.623 | 0.24 | 0.45 |

| 6 | 50 | 0.5 | 10 | 72.960 | 0.27 | 0.55 |

| 7 | 70 | 0.7 | 0 | 74.214 | 0.29 | 0.56 |

| 8 | 70 | 0.5 | 5 | 76.722 | 0.27 | 0.68 |

| 9 | 70 | 0.6 | 10 | 75.639 | 0.23 | 0.58 |

| Level i Mean Value | Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Valve Opening | Outlet Pressure | Inlet Subcooling | |

| Level 1 mean | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.54 |

| Level 2 mean | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.53 |

| Level 3 mean | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.51 |

| Range (R) | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Factor order | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Factors | Sum of Squares | Degree of Freedom | Mean Square | Range (R) | Variance Contribution (%) | Order of Influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valve opening | 0.03002 | 2 | 0.01501 | 0.14 | 57.6 | 1 |

| Outlet pressure | 0.01158 | 2 | 0.00579 | 0.08 | 22.2 | 2 |

| Inlet subcooling | 0.00109 | 2 | 0.00054 | 0.03 | 2.1 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, Z.; Wang, H.; Lin, C. Gas-Liquid Flow of R290 in the Integrated Electronic Expansion Valve and Vapor Injection Loop for Heat Pump. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13114. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413114

Ji Z, Wang H, Lin C. Gas-Liquid Flow of R290 in the Integrated Electronic Expansion Valve and Vapor Injection Loop for Heat Pump. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13114. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413114

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Zhiyuan, Haimin Wang, and Chunjing Lin. 2025. "Gas-Liquid Flow of R290 in the Integrated Electronic Expansion Valve and Vapor Injection Loop for Heat Pump" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13114. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413114

APA StyleJi, Z., Wang, H., & Lin, C. (2025). Gas-Liquid Flow of R290 in the Integrated Electronic Expansion Valve and Vapor Injection Loop for Heat Pump. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13114. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413114