1. Introduction

Modern applications in fields such as autonomous driving, healthcare, and smart-city infrastructure depend on vast amounts of data that are spread across different devices and organizations. In the case of autonomous vehicles, for instance, every car constantly records sensory information that could, if jointly utilized, improve perception and driving-assistance models and thus contribute to safer roads [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, centralizing such data is often infeasible due to concerns about privacy, data protection laws, and practical limitations.

Federated Learning (FL) enables distributed training without centralizing raw data [

5,

6,

7]. Each client trains a local model on its private dataset and transmits only model updates to a central server, which aggregates them to form a global model. Although this approach mitigates privacy risks, traditional algorithms such as Federated Averaging (FedAvg) still require exchanging the information of the entire model at every communication round, leading to significant communication overhead [

4,

5].

To address these challenges, Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) has been introduced as a means to reduce communication and computation costs [

8,

9,

10]. Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) inserts small trainable matrices

and

into pretrained layers, enabling fine-tuning with fewer parameters [

11].

Although the FL does not involve the exchange of raw data during the update process, it remains vulnerable to privacy leakage from shared updates. Gradient inversion attack [

12,

13,

14] and membership inference attack [

15,

16] have shown that private information can be reconstructed from gradients. Consequently, it is crucial to protect not only data but also shared parameters.

Differential Privacy (DP) provides a formal privacy guarantee by injecting calibrated noise into gradients, thus bounding the influence of any individual data sample [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Recent DP-based FL frameworks, adaptive local mechanisms, and feedback-controlled approaches aim to achieve a balance between privacy protection and model accuracy [

21,

22,

23]. Although these approaches improve privacy protection, they often add computational complexity or reduce model accuracy, especially under strict privacy budgets. Furthermore, data heterogeneity in non-i.i.d. settings causes the global model to converge toward an average representation that fits no client well, resulting in degraded overall accuracy [

24,

25].

In this paper, we propose FedSA-LoRA-DP, a novel FL framework that integrates DP and leverages LoRA for efficient model adaptation. In the framework, we share only the matrices between clients and the server and apply the DP to them to ensure secure aggregation. This design maintains the same amount of transmitted data even when differential privacy noise is added, as the noise only perturbs the numeric values of the matrices. Through experiments conducted under various conditions, we confirm that the proposed framework maintains a high accuracy of the model even in a non-independent and identically distributed (non-i.i.d.) environment, demonstrating its robustness and practical effectiveness.

We summarize our contributions as follows:

We design a selective aggregation strategy that aggregates only the LoRA matrices while keeping the matrices local to each client, achieving both communication efficiency and personalization.

We incorporate DP into the shared matrices, providing formal privacy guarantees without increasing communication overhead.

We demonstrate through experiments on multiple datasets (CIFAR-100, MNIST, and SVHN) that FedSA-LoRA-DP achieves comparable accuracy to non-private baselines even under heterogeneous and partial participation conditions.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on PEFT, FL, and DP.

Section 3 introduces our proposed method, which integrates selective Aggregation and LoRA with DP.

Section 4 presents the experimental setup and performance evaluation under various conditions.

Section 5 discusses the implications of the results, including the effects of data heterogeneity, LoRA rank, dataset characteristics, and models. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Federated Learning and Communication Efficiency

To address high communication cost and client heterogeneity, several strategies have been developed to reduce the amount of data exchanged while maintaining model accuracy. Sattler et al. [

4] proposed sparse update compression to reduce bandwidth usage. Li et al. [

26] proposed FedProx, an additional regularization term to stabilize optimization under non-i.i.d. conditions, while Wang et al. [

27] introduced FedNova, in which client updates are normalized to mitigate the impact of heterogeneous local training. Other communication-efficient approaches leverage gradient quantization and periodic aggregation to reduce transmission overhead and maintain scalability in federated systems [

28,

29,

30].

While these methods improve scalability, they still transmit large parameter sets and may underperform in highly heterogeneous settings.

2.2. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning

PEFT has emerged as a complementary solution to reduce communication and computational load by limiting the number of trainable parameters. Instead of updating all parameters, methods such as Adapter-Tuning [

8], Prefix-Tuning [

9], and Prompt-Tuning [

10] learn lightweight modules that preserve most of the pretrained model’s knowledge. LoRA [

11] has attracted particular attention by introducing trainable low-rank matrices

and

into existing layers, achieving both parameter and communication efficiency without degrading performance.

Aggregating the LoRA matrices

and

in an FL setting presents significant challenges. If the server directly aggregates the

and

matrices and broadcasts them to all clients, aggregation errors occur. Specifically, in an FL task with K clients, the model update of each client can be represented by two low-rank matrices,

and

, introduced by LoRA. After aggregation and broadcasting on the server, the model update for each client is given as follows:

which is different from the proper model update

.

To address this challenge, some methods have been explored [

31,

32,

33]. For instance, Sun et al. [

32] proposed the method that updates only

and freezes the

. Thus, the local update on each client is

where

denotes the initialized and fixed weights. Guo et al. [

31] proposed the method that aggregates only the

matrices across clients while keeping the

matrices local. Thus, the local update on each client

i is

.

Despite these frameworks significantly reducing communication overhead, most have yet to achieve a well-balanced integration of model accuracy, privacy preservation, and efficiency. Ensuring consistent performance while maintaining strong privacy guarantees remains an open challenge.

2.3. Differential Privacy in LoRA-Based Federated Learning

Recent advances have explored combining DP with PEFT in FL to enhance privacy and communication efficiency. Liu et al. [

34] proposed the method which integrates LoRA and DP to fine-tune large language models in a distributed manner. While this approach effectively reduces communication cost and provides formal privacy guarantees, it aggregates both LoRA matrices

and

across clients, thereby limiting client-level personalization and introducing potential bias when data distributions are non-i.i.d.

Sun et al. [

32] proposed the method which freezes the shared

matrix and updates only

to simplify communication and avoid aggregation inconsistency. Although this design improves communication efficiency, it constrains model expressivity since the shared representation

remains fixed throughout training.

Overall, while these DP-integrated LoRA frameworks have made progress in improving privacy and communication efficiency in federated settings, most still face limitations in balancing personalization, model expressivity, and scalability under heterogeneous data conditions. A more comprehensive approach that jointly achieves privacy preservation, communication efficiency, and robustness to client diversity remains an open challenge.

2.4. Privacy Attacks and Defense Mechanisms

Although FL reduces direct data sharing, it does not fully eliminate privacy risks. There are studies that have shown that sensitive information can be extracted from shared model updates. For example, gradient inversion attack [

12,

13,

14] reconstructs input samples by exploiting gradients. Membership inference attacks [

15,

16] reveal whether specific data points were included in training. These studies argue that even without central data aggregation, model parameters themselves can act as unintended information channels.

To mitigate such risks, several defense strategies have been proposed. For instance, blockchain-assisted FL has been investigated as a way to ensure transparency and accountability across decentralized systems [

35,

36]. Nevertheless, most of these methods either introduce high computational overhead or compromise model utility when applied to large-scale models.

DP provides a rigorous framework to quantify privacy guarantees by bounding the influence of any individual data sample [

17,

18,

19]. Within FL, DP has been applied to protect model updates from inference and reconstruction attacks. Since DP simply perturbs the numeric values of existing parameters without altering their dimensionality or structure, it does not increase communication cost, in contrast to cryptographic approaches that require additional encoded data [

37,

38].

Recent research has also provided empirical evidence that the theoretical guarantees of differential privacy can effectively mitigate practical privacy attacks. For example, Mironov [

19] introduced Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP), which provides a tighter accounting of cumulative privacy loss, while Jayaraman and Evans [

39] empirically demonstrated that DP significantly reduces the success rate of membership inference and data reconstruction attacks in machine learning models. Similarly, Dong et al. [

40] established refined analytical bounds for the Gaussian mechanism, confirming its robustness against adversarial inference under realistic settings. These studies collectively support the use of DP as a principled defense framework that provides both theoretical and empirical privacy protection.

Despite extensive research efforts on communication-efficient, parameter-efficient, and privacy-preserving federated learning, an effective framework that simultaneously achieves high model accuracy, strong privacy protection, and low communication overhead has yet to be established.

3. Proposed Method

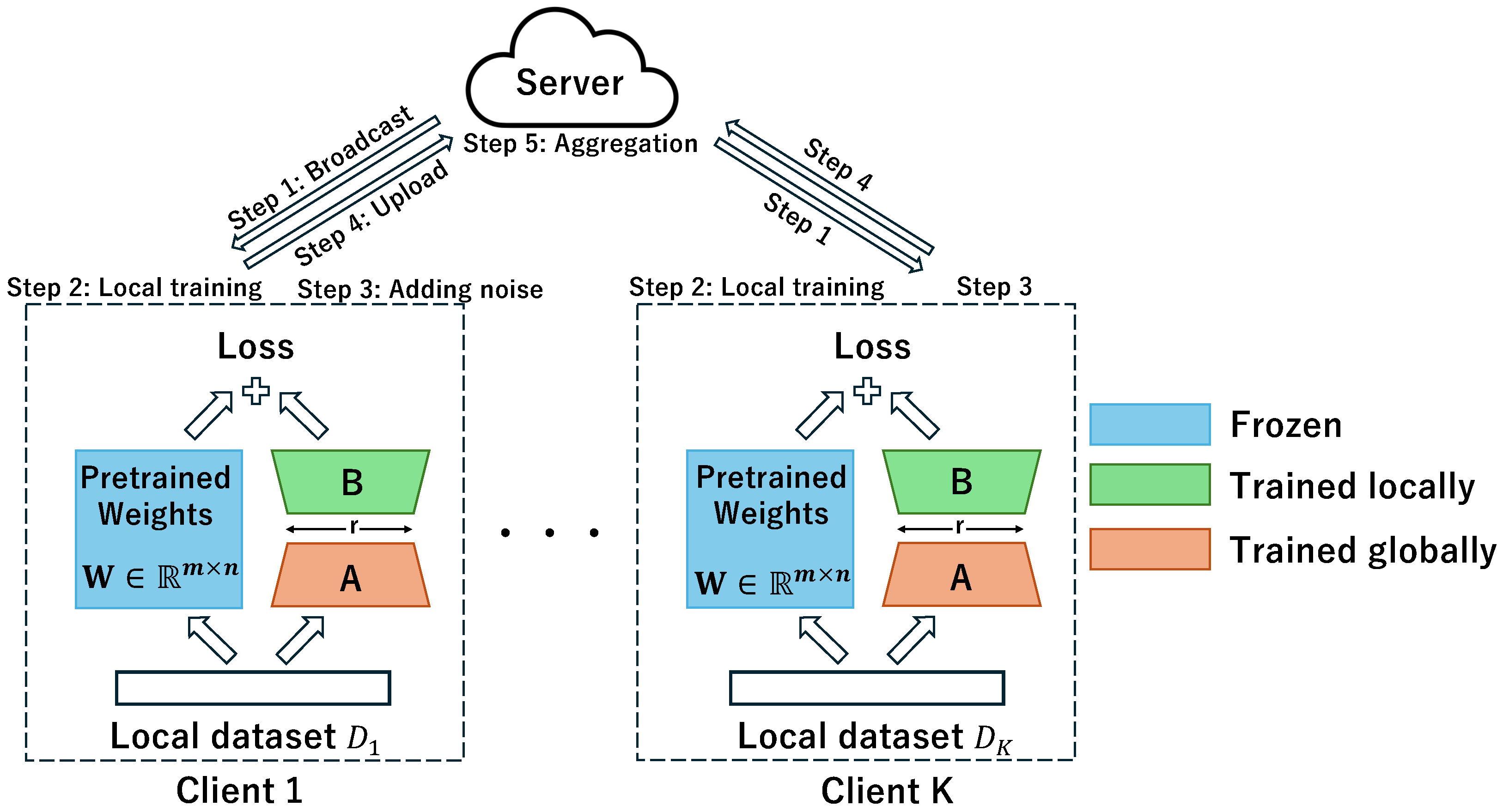

We propose FedSA-LoRA-DP, a federated learning framework that integrates Selective Aggregation and LoRA with DP to achieve communication efficiency, privacy preservation, and personalization simultaneously. An overview of our proposed framework is shown in

Figure 1. To clarify the operation of our proposed framework, the main steps of FedSA-LoRA-DP are summarized as follows.

- Step 1:

Broadcast: The server distributes the aggregated matrices to all clients, which combine them with their frozen pretrained weights and local .

- Step 2:

Local training: Each client i performs local training on its private dataset to update and .

- Step 3:

Adding noise: After training, differential privacy noise is applied to the gradients of through gradient clipping and Gaussian perturbation, altering only their numeric values without changing the communication size.

- Step 4:

Upload: The clients upload the differentially private matrices to the server, while keeping local to preserve personalization.

- Step 5:

Aggregation: Finally, the server aggregates the received matrices using a weighted average based on the local sample sizes, and the updated global is broadcast to all clients for the next round.

Specifically, FedSA-LoRA-DP exploits the structural asymmetry between LoRA’s low-rank matrices and by aggregating the matrices into a shared matrix on the server while keeping the matrices local to each client. The overall training and aggregation procedure of the proposed framework is summarized in Algorithm 1.

Let

be a frozen pretrained weight matrix. In LoRA, a low-rank matrix

is parameterized as

, where

and

. In each client

i, the pretrained weight matrix

is augmented with a LoRA module parameterized by low-rank matrices

and

. The model weights are updated as

where

t denotes the learning round. Only

and

are trainable, leading to a significant reduction in the number of trainable and transmitted parameters compared to full fine-tuning. In LoRA clients can collaboratively train global knowledge via

while retaining personalization through local

[

41].

| Algorithm 1 FedSA-LoRA-DP |

- Require:

Pretrained model , LoRA rank r, learning rate , clipping norm C, noise multiplier , rounds T, clients K - Ensure:

Personalized models for all clients

Server: Insert LoRA modules into , freeze backbone, broadcast for to T do for each client in parallel do Receive and update: where is obtained by clipping and adding Gaussian noise Update Upload and to the server end for Broadcast to all clients Privacy accounting: Update using RDP end for

|

For each client

i, let

be a minibatch and

the gradient for sample

. We apply DP to the shared parameters

as follows. Each gradient is clipped:

and then perturbed with Gaussian noise:

where

C is the clipping norm,

is the noise multiplier and

is the identity matrix. The

parameters are then updated by

where

is the learning rate. In contrast,

is updated without noise. Following the privacy composition framework of Abadi et al. [

18], the noise multiplier

is computed based on the specified privacy budget

, the total number of iterations

T, where

N represents the total number of training samples.

Consider a situation with

K clients where each client

i holds a local dataset

. Each client takes a sample

from their respective dataset

; we set

. Let

denote the number of samples on client

i. After local updates, only the updated

is uploaded to the server. The server aggregates them using a weighted average:

The aggregated

is then broadcast to all clients for the next round.

We use Opacus, a PyTorch library for differential privacy, to implement DP and track the cumulative privacy loss during training [

20]. Specifically, we employ the built-in RDP accountant to compute the privacy spending

across multiple communication rounds, following the composition rules of RDP [

19].

4. Experiment and Evaluation

4.1. Experiment Setup

Experiments were conducted on the CIFAR-100 dataset [

42], using an input resolution of

and following the standard preprocessing pipeline for BiT models [

43]. Samples of the datasets are as shown in

Figure 2 The dataset was partitioned into 10 clients to simulate a federated learning environment, and both i.i.d. and non-i.i.d. settings were examined. In the non-i.i.d. scenario, data were distributed across clients according to a Dirichlet distribution with

, introducing statistical heterogeneity to reflect realistic federated learning conditions better. A local batch size of 64 was used for client-side training.

For the model architecture, BiT-s R50 × 1 and BiT-s R101 × 1, both pretrained on ImageNet-21k, were employed as backbones. In all experiments, the backbone networks were kept frozen, and LoRA modules were inserted into all convolution layers to enable parameter-efficient fine-tuning. Federated training was performed for 100 communication rounds. During each round, only the LoRA matrices were aggregated on the server, while the matrices remained local to each client. Client-side training was conducted for three epochs per round using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with a cosine learning rate schedule.

For experiments involving privacy preservation, differential privacy was applied by performing DP exclusively on the shared LoRA

matrix, while local parameters were left unperturbed [

18]. The main hyperparameters used in the federated learning setup are summarized in

Table 1.

To ensure accurate privacy accounting, we adopted RDP [

19] as implemented in Opacus [

20]. RDP provides a tighter composition bound compared to standard

-DP by tracking the cumulative privacy loss across multiple training iterations. In our setup, each client performed per-sample gradient clipping with norm

and added Gaussian noise with a multiplier

to the gradients of the LoRA

parameters during local training. The sampling rate is determined by the mini-batch size (

) relative to the local dataset size, and the cumulative privacy loss

was computed from the RDP accountant after

communication rounds at a fixed

. We report the final privacy budgets

and

, corresponding to the noise multipliers

and

, respectively.

4.2. Analysis

This section provides an in-depth analysis of the proposed FedSA-LoRA-DP framework by examining how different factors, such as data heterogeneity, client participation rate, and LoRA rank, affect the overall performance. In real-world federated learning scenarios, it is unlikely that all clients participating in training will have the same data distribution, and it is also difficult for the same clients to always participate in training. For this reason, we compared experiments in i.i.d. and non-i.i.d. environments, as well as experiments where the client participation rate was changed. Furthermore, we evaluated whether the proposed method could maintain high accuracy in spite of lighter parameter configuration to confirm its applicability in resource-constrained federated environments. We conducted experiments with LoRA ranks set to and , and verified the trade-off between model weight reduction and accuracy.

Unless otherwise specified, the parameters listed in

Table 2 are used throughout the experiments. Since the primary source of client diversity in our setting arises from differences in dataset size and class balance, clients with larger and more balanced data naturally achieve higher accuracy. Therefore, instead of reporting individual client metrics, we summarize results at the global level to focus on the overall performance trends. All reported results in this section denote the mean and standard deviation of test accuracies across all clients.

4.2.1. Effect of Data Heterogeneity

To analyze the impact of data heterogeneity, we conducted experiments under both i.i.d. and non-i.i.d. (Dirichlet

) data distributions and compared the resulting model performance. The results of this analysis are summarized in

Table 3.

When comparing the i.i.d. and non-i.i.d. settings for the BiT-S R50 × 1 model, FedSA-LoRA exhibited a performance gap of 18.87 points, whereas FedSA-LoRA-DP showed gaps of 18.75 points and 18.73 points for and , respectively. Similarly, for the BiT-S R101 × 1 model, the accuracy gap between i.i.d. and non-i.i.d. settings was 18.99 for FedSA-LoRA, compared to 18.79 points for both and in FedSA-LoRA-DP. Furthermore, when comparing FedSA-LoRA and FedSA-LoRA-DP, the accuracy difference was only 0.40–0.41 points for the R50 × 1 model and 0.44 points for the R101 × 1 model.

These results demonstrate that the proposed FedSA-LoRA-DP framework maintains stable learning performance even under data heterogeneity. The minimal performance difference between FedSA-LoRA and FedSA-LoRA-DP indicates that the introduction of differential privacy does not significantly compromise model accuracy. A detailed discussion of the limitations under more extreme non-i.i.d. conditions is provided in

Section 5.1.

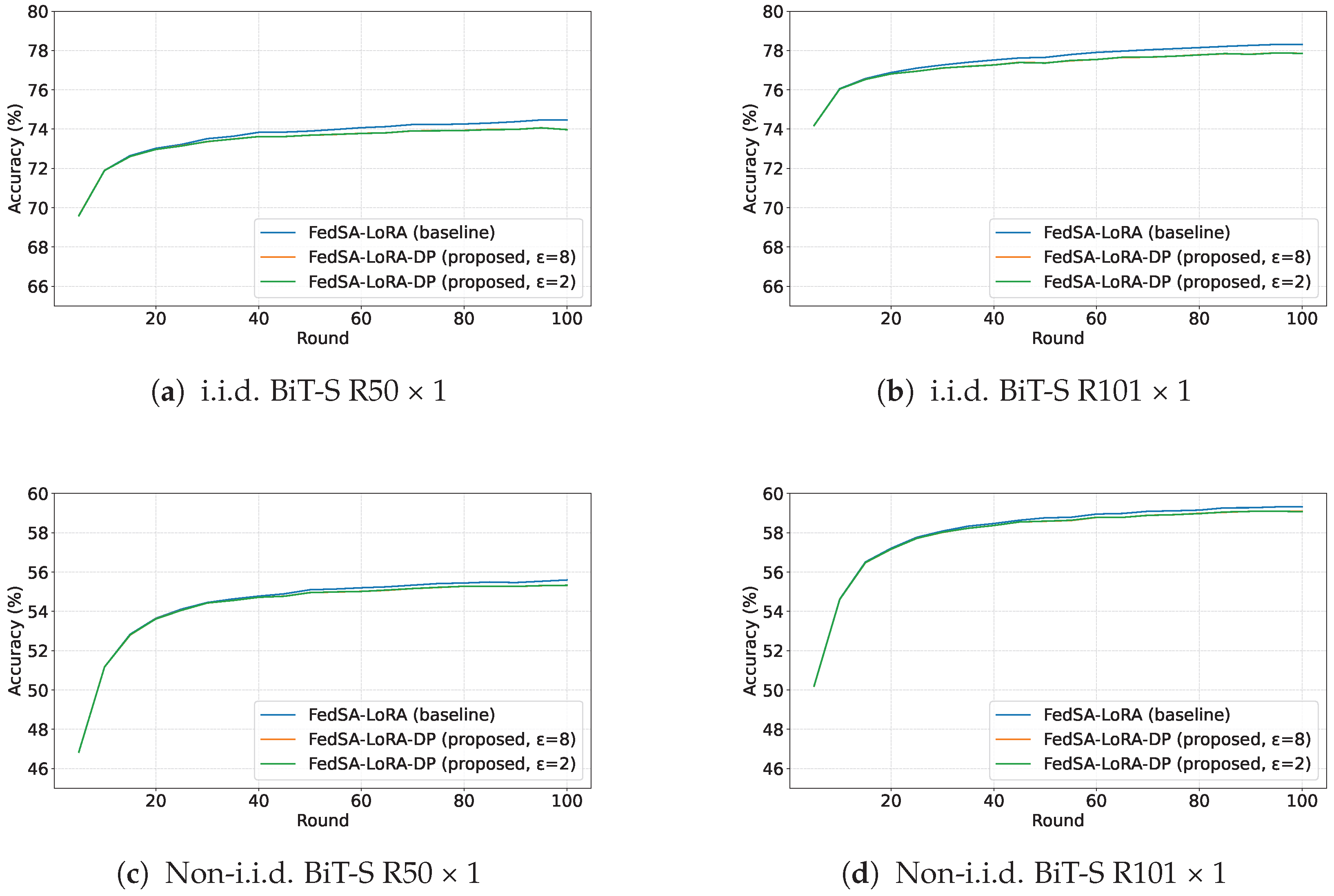

As shown in

Figure 3, all methods exhibit similar convergence behavior during training, indicating that the introduction of differential privacy does not hinder the learning dynamics or delay convergence. The performance difference appears primarily in the final accuracy, suggesting that DP noise affects only the fine-tuning stage rather than the overall optimization trajectory. Furthermore, when comparing

and

, there is almost no observable difference in the learning dynamics, indicating that the injected DP noise does not affect convergence stability. This indicates that the injected DP noise is sufficiently small compared to the model’s inherent stochasticity, resulting in nearly identical convergence behavior and learning stability across different privacy levels.

4.2.2. Effect of Client Participation Rate

To verify whether the model can maintain high accuracy even in scenarios where not all clients are able to participate in every training round, we investigate the framework’s robustness to partial client participation by comparing full (

), where all clients join every round, and partial (

), where 30% of clients are randomly selected for each round. To maintain comparable privacy levels across different participation settings, the noise multiplier

was set to 1.1 for

and 3.0 for

. The results evaluating this effect are summarized in

Table 4.

When comparing the client participation ratios and for the BiT-S R50 × 1 model, FedSA-LoRA exhibited an accuracy difference of 0.50 points, whereas FedSA-LoRA-DP showed gaps of 0.42 points and 0.40 points for and , respectively. Similarly, for the BiT-S R101 × 1 model, the accuracy gap between the two participation settings was 0.55 points for FedSA-LoRA, 0.54 points for FedSA-LoRA-DP (), and 0.53 points for FedSA-LoRA-DP ().

The largest gap between FedSA-LoRA and FedSA-LoRA-DP was observed in the comparison of the BiT-S R101 × 1 model with , where the accuracy difference reached 0.43 points. These results suggest that FedSA-LoRA-DP maintains comparable accuracy to FedSA-LoRA even when the number of participating clients is reduced, demonstrating robustness against partial participation and communication variability in federated environments.

4.2.3. Effect of LoRA Rank

To investigate the model’s ability to maintain high accuracy while being trained with a smaller number of parameters, we analyze the effect of the LoRA rank by comparing configurations with

and

. The results are summarized in

Table 5.

When comparing LoRA ranks and for the BiT-S R50 × 1 model, FedSA-LoRA showed a performance difference of 0.19 points, while FedSA-LoRA-DP reported gaps of 0.13 points for both and . For the BiT-S R101 × 1 model, the accuracy differences were 0.05 points for FedSA-LoRA and only 0.02 and 0.01 points for FedSA-LoRA-DP ( and ), respectively. Furthermore, when comparing FedSA-LoRA and FedSA-LoRA-DP, the accuracy gap was 0.40–0.44 points for rank , whereas it decreased to 0.34–0.41 points for rank .

The smallest accuracy gap was observed for the BiT-S R50 × 1 model with

, indicating that the proposed method maintains high accuracy even under stronger parameter compression. These results demonstrate that the proposed framework is robust to changes in LoRA rank, and that privacy preservation can be achieved with negligible loss in accuracy. A more detailed discussion on the relationship between LoRA rank and noise robustness is provided in

Section 5.2.

4.3. Generalizability Across Datasets

The goal of this analysis is to evaluate the generalizability of the proposed FedSA-LoRA-DP framework across datasets of varying complexity and domain characteristics. We employed three datasets: CIFAR-100, MNIST [

44], and SVHN [

45], each differing in image dimensionality, visual diversity, and class structure. Samples of MNIST and SVHN are as shown in

Figure 4.

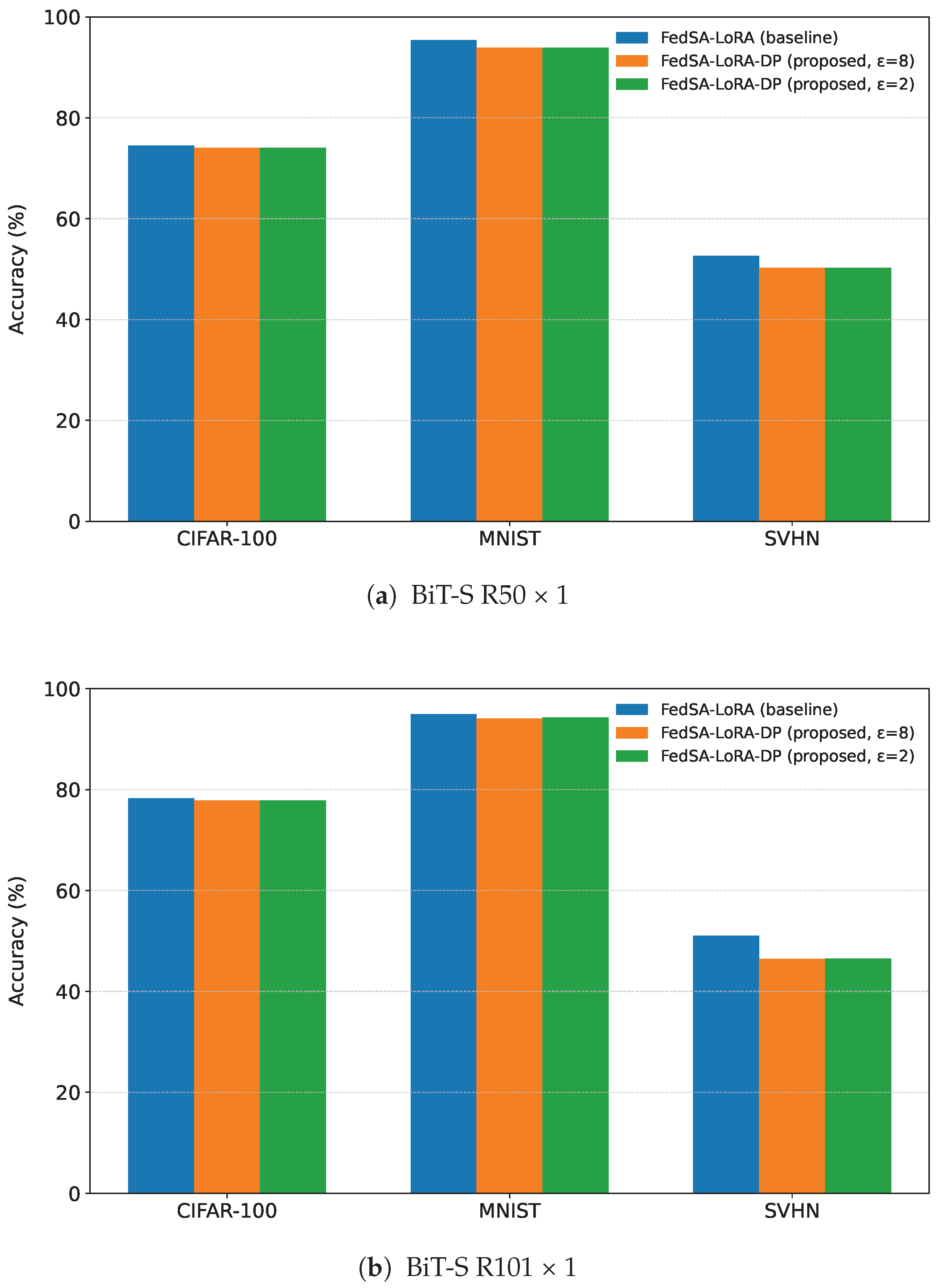

All experiments in this subsection were conducted under the i.i.d. setting with a LoRA rank of

and client participation

, to ensure consistent comparison across datasets. The results of test accuracy are shown in

Figure 5a,b, corresponding to the BiT-S R50 × 1 and R101 × 1 architectures, respectively.

For the BiT-S R50 × 1 model, FedSA-LoRA achieved 74.47% accuracy on CIFAR-100, while FedSA-LoRA-DP achieved 74.07% for and 74.06% for , resulting in only a 0.4-point difference. For MNIST, FedSA-LoRA achieved 95.38%, and FedSA-LoRA-DP achieved 93.91% for both and , corresponding to a 1.47-point reduction. For SVHN, FedSA-LoRA achieved 52.63%, and FedSA-LoRA-DP achieved 50.24% for and 50.28% for , showing a 2.3-point difference.

For the BiT-S R101 × 1 model, FedSA-LoRA achieved 78.32% accuracy on CIFAR-100, while FedSA-LoRA-DP achieved 77.88% for both and , resulting in only a 0.4-point difference. For MNIST, FedSA-LoRA achieved 94.99%, and FedSA-LoRA-DP achieved 94.11% for and 94.35% for , corresponding to reductions of 0.88 and 0.64 points. For SVHN, FedSA-LoRA achieved 51.03%, and FedSA-LoRA-DP achieved 46.47% for and 46.49% for , showing differences of 4.56 points and 4.54 points.

These results confirm that the proposed FedSA-LoRA-DP framework maintains high accuracy across datasets with different visual and structural complexities. A deeper discussion of the dataset-dependent privacy–utility trade-off is provided in

Section 5.3.

4.4. Communication Cost

To quantitatively validate the communication efficiency of our proposed methods, we measured both the per-round and total communication costs for FedSA-LoRA, FedSA-LoRA-DP, and the baseline FedAvg.

As shown in

Table 6, the per-round communication cost of FedSA-LoRA and FedSA-LoRA-DP is only 0.6375 MB, whereas FedAvg requires 90.428 MB per round, corresponding to an approximate 99% reduction in communication overhead.

The substantial reduction in communication cost stems from the structural difference between FedAvg and our LoRA-based approaches. In FedAvg, the entire set of model parameters must be transmitted between clients and the server in each communication round, resulting in a payload proportional to the full model size. In contrast, our methods employ LoRA, which decomposes the parameter update into two small matrices, and . During training, only is communicated, while the pretrained base weights remain frozen. This design effectively transforms federated learning into a transfer learning paradigm, where clients fine-tune lightweight adaptation modules rather than the entire model. Consequently, the per-round communication cost scales linearly with the low-rank dimension r, leading to a 99% reduction compared to standard FedAvg. Even when differential privacy is applied, the communication cost remains unchanged, as DP noise is injected locally without altering message size.

Therefore, our method achieves substantial communication savings while maintaining competitive global accuracy.

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations Under Extreme Data Heterogeneity

Table 7 presents the results under more extreme non-i.i.d. conditions, where the Dirichlet parameter is set to

. As

decreases, the class distributions among clients become highly imbalanced, and the overlap between local datasets diminishes substantially. Consequently, the global model struggles to generalize across clients, resulting in a marked drop in overall test accuracy. This degradation can be attributed to two key structural factors of the proposed framework.

First, the low-rank structure of LoRA inherently limits the representational capacity of each client model. When client data distributions differ significantly, the restricted trainable subspace may lead to underfitting, as the low-rank decomposition cannot fully capture the diversity of local feature representations. This structural limitation becomes more pronounced as the degree of data heterogeneity increases, leading to diminished generalization across clients.

Furthermore, previous work has shown that the method performs well even under non-i.i.d. conditions in large-scale language models, where a substantially higher-dimensional [

31,

32] parameter space is used. However, in our image classification setting, the total number of trainable parameters is relatively small, making the expressive power of LoRA more constrained. As a result, it becomes more challenging for low-rank adaptation to capture client-specific feature variations, which exacerbates the performance drop under strong heterogeneity.

Second, since only the matrices are aggregated on the server while remain local, the amount of shared information across clients is substantially reduced. Although this selective aggregation strategy greatly enhances communication efficiency, it can intensify model divergence when client distributions are highly dissimilar. Under such conditions, the aggregated updates fail to represent a coherent global direction, limiting the benefits of collaborative training.

In summary, while FedSA-LoRA-DP maintains robustness under moderate heterogeneity (e.g., ), its performance deteriorates sharply under extreme data skewness, revealing an inherent structural limitation of the selective aggregation mechanism. Future work could address this issue by adopting clustering-based aggregation or personalized model fusion techniques to further enhance robustness in highly non-i.i.d. federated environments.

5.2. Impact of LoRA Rank on Noise Robustness

Table 5 demonstrates an interesting trend; the performance degradation caused by DP noise becomes smaller as the LoRA rank decreases. This observation indicates that lower-rank configurations inherently exhibit stronger robustness to DP-induced noise. The following factors may explain this behavior.

First, reducing the LoRA rank effectively decreases the number of trainable parameters, thereby limiting the dimensionality of the parameter space affected by the injected noise. In lower-rank settings, the gradient perturbations caused by Gaussian noise are distributed over a smaller subspace, leading to more stable optimization and less distortion of the learned representations. In contrast, higher-rank LoRA modules expose a larger number of parameters to DP noise, increasing the likelihood of performance degradation due to noisy gradient updates.

Second, in the proposed FedSA-LoRA-DP framework, DP is applied only to the matrices. When the rank r is smaller, the size of these matrices—and consequently the number of perturbed parameters—is also reduced. As a result, the total noise magnitude introduced per round decreases, further mitigating accuracy loss. This selective protection mechanism, combined with low-rank parameterization, thus achieves a natural form of noise resilience.

Finally, these results highlight a trade-off between model capacity and privacy robustness. While higher ranks provide greater representational power, lower ranks yield improved stability against DP noise. This implies that LoRA-based federated systems can exploit rank as a controllable hyperparameter to balance privacy and performance, enabling efficient and privacy-preserving learning even with constrained model capacity.

5.3. Impact of Dataset Characteristics on Privacy–Utility Trade-Off

The variations in performance observed across CIFAR-100, MNIST, and SVHN can be attributed to differences in dataset complexity and representational diversity. Unlike the preceding quantitative analysis, this section focuses on the underlying factors that influence the privacy–utility trade-off in federated LoRA-based training.

First, the dimensionality and representational complexity of each dataset play a critical role in determining the sensitivity to noise injection. CIFAR-100 consists of high-resolution and semantically rich images, where the LoRA modules can capture diverse feature patterns even with low-rank adaptation. As a result, the Gaussian noise added to the gradients of the matrices has only a marginal impact on the overall optimization, leading to a minimal accuracy gap of approximately 0.4 points.

In contrast, MNIST is a low-dimensional and homogeneous dataset with limited intra-class variation. In such cases, the model’s representational subspace is narrow, and the DP-induced perturbation in the low-rank updates may directly disrupt the already compact feature space. Consequently, a larger accuracy drop of about 1.5 points was observed. This slightly larger gap than in the CIFAR-100 case suggests that DP-induced noise has a more noticeable effect on datasets with limited feature diversity and simpler visual representations.

For SVHN, which contains real-world digit images with substantial illumination and background variability, both the low-rank approximation and the heterogeneous data distributions among clients contribute to training instability. Because the shared matrix captures only a small portion of the total feature variation across clients, the model becomes more sensitive to gradient variance, leading to less stable updates and lower overall accuracy. This explains the relatively lower accuracy, around 2.3 points below FedSA-LoRA, despite consistent privacy guarantees. Also, this effect is inherent to the dataset’s complex visual structure rather than the privacy mechanism itself.

Additionally, these observations suggest that the effectiveness of the proposed method depends on the expressive capacity of the LoRA modules relative to dataset complexity. In large-scale models such as LLMs, where parameter space is extremely high-dimensional, low-rank adaptation can still capture rich feature interactions even under strong privacy constraints. However, for smaller-scale models or simpler tasks like image classification, the limited number of trainable parameters may not fully compensate for DP-induced noise, making the performance degradation more noticeable.

Overall, these findings highlight that the privacy–utility trade-off in federated LoRA-based learning is inherently dataset-dependent. Datasets with richer and higher-dimensional representations tend to absorb privacy noise more effectively, while simpler or noisier datasets experience more pronounced degradation. Future work could explore adaptive noise scaling or rank-aware privacy calibration strategies to balance the noise magnitude according to dataset complexity.

5.4. Future Work

In future work, we plan to verify the extent to which the proposed method is resistant to membership inference attacks and gradient leakage attacks. We demonstrated that FedSA-LoRA-DP effectively balances model accuracy and privacy through differential privacy in this paper. However, further investigation is needed to evaluate its empirical resilience against direct privacy attacks.

Theoretical guarantees of differential privacy have been extensively established in prior studies [

17,

18], ensuring formal protection against information leakage in expectation. Nevertheless, it would be valuable to empirically validate how effectively FedSA-LoRA-DP withstands practical privacy attacks, such as membership inference or gradient inversion, under realistic federated conditions. This line of research would complement the theoretical analysis presented in this work and provide a more comprehensive assessment of the method’s robustness.

In addition, future work will extend the proposed framework to large-scale and domain-specific applications such as autonomous driving, medical imaging, and natural language processing. Evaluating FedSA-LoRA-DP under these complex, heterogeneous, and data-rich environments will be essential to verify its scalability, practical effectiveness, and robustness to extreme non-i.i.d. conditions. Such experiments will also enable a more direct connection between the theoretical contributions and real-world deployment scenarios.

Furthermore, we plan to expand our experimental evaluation to include comparisons with representative DP-FL baselines. These benchmarks will help quantify the relative advantages of FedSA-LoRA-DP in terms of accuracy retention, communication efficiency, and privacy–utility trade-offs. Such analysis will provide a more comprehensive empirical perspective on how our method aligns with and differs from existing adaptive or personalized DP-FL frameworks.

Depending on future requirements, we will consider integrating cryptographic techniques such as secure aggregation or homomorphic encryption to further strengthen privacy protection. Therefore, a systematic empirical evaluation against these attack scenarios remains an important direction for future work to confirm whether FedSA-LoRA-DP provides robust privacy protection beyond formal differential privacy guarantees.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed FedSA-LoRA-DP, a novel FL framework that integrates DP and LoRA for efficient model adaptation. This method protects privacy during the training process while maintaining communication efficiency and model accuracy.

Evaluation across various experimental conditions on the CIFAR-100 dataset confirmed that the proposed method minimizes accuracy degradation compared to its non-private counterpart. Furthermore, additional experiments using the MNIST and SVHN datasets confirmed that the proposed method demonstrates high versatility across different data domains. These results demonstrate that FedSA-LoRA-DP is an effective method for achieving both privacy and performance.

As future work, we plan to quantitatively evaluate the actual degree of privacy protection using attack methods such as Membership Inference Attack and Gradient Leakage Attack. In addition, we aim to extend the proposed FedSA-LoRA-DP framework to large-scale, real-world applications such as autonomous driving and healthcare, to further validate its scalability, robustness, and practical effectiveness in complex federated environments. We also plan to include comparative evaluations with representative DP-FL baselines to more comprehensively assess the privacy–utility trade-off and communication efficiency of the proposed framework.