1. Introduction

Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) methods serve as an effective way to evaluate and rank various alternatives according to the preferences of decision-makers. Over the years, their application has become widespread. In industrial robot selection, a critical and complex task, the literature includes broad taxonomies of methods [

1], early intelligent decision support systems [

2], and foundational Fuzzy Digraph (FD) approaches [

3]. Recent work continues to advance this specific domain, proposing new hybrid models [

4,

5] and methods using advanced interval-valued fuzzy sets [

6]. Beyond manufacturing, MCDM methods are applied broadly, as highlighted in comprehensive reviews [

7], with applications in optimizing machining processes [

8,

9], selecting biomaterials [

10], and complex product design [

11]. A common challenge in all these applications is the inherent uncertainty from incomplete or imprecise information. To address this, scientists have effectively exploited Fuzzy Logic’s power to enhance MCDM methods, leading to established and widely-used approaches like Fuzzy TOPSIS [

12] and Fuzzy AHP [

13].

A more profound challenge, however, is that standard MCDM approaches (including fuzzy extensions) often fail to model the intricate dependencies (including feedback loops) that exist among criteria. FCMs—a powerful soft computing technique for capturing complex causal relationships [

14]—have been explored as a solution. As detailed in reviews [

15], FCMs have demonstrated flexibility in various domains, such as medical decision-making [

16,

17,

18] and forecasting or prediction [

19,

20]. Methodological work has also expanded their capabilities, with algorithms for learning FCMs from data [

21,

22,

23] and theoretical advances in their structure, such as transformations [

24] and the integration of granular computing [

25,

26].

This flexibility has naturally led to the integration of FCMs into MCDM methodologies. Seminal studies proposed soft computing methods using FCMs to explicitly handle dependence and feedback [

27,

28]. This preliminary work was extended to hybrid models, such as those combining FCMs with hierarchical TOPSIS [

29]. These cognitive frameworks have been applied to various decision support problems, including hotel quality assessment [

30], medical diagnosis [

31,

32], and even in analyzing time-series data for decision-making [

33]. However, despite these strengths, this preliminary work has two main limitations: (1) FCMs are often utilized as a ‘one-off’ correction mechanism rather than a dynamic simulation tool and (2) their effectiveness remains highly dependent on the quality of expert knowledge used to build the causal map, a challenge highlighted even in the FCM learning literature [

21].

While traditional MCDM methods, including fuzzy extensions, constitute an effective decision support tool for structured problems, they are based on the assumption of criteria independence. Often, the only factor taken into consideration is the importance of each criterion, which determines the degree to which each criterion contributes to the final ordering of alternatives. This assumption can be a significant limitation in complex, real-world scenarios, such as industrial robot selection, where criteria like ‘cost’, ‘payload capacity’, and ‘flexibility’ are inherently interrelated. The resulting inability of traditional MCDM methods to fully incorporate systemic, causal influences and intricate dependencies (including feedback loops) means that the derived decision support may be limited for strategic planning. This represents the profound challenge that this research framework addresses. Although some approaches have attempted to address the criteria interdependencies, they have done so mostly in a static manner. FCMs, on the other hand, have emerged as a powerful tool capable of modeling dynamic systems with feedback loops; however, despite their advantages, they remain under-explored in MCDM problems. To address these challenges, this research, which is an expanded version of the paper [

34], introduces a cognitive framework for MCDM. Crucially, unlike existing hybrid approaches that predominantly utilize FCMs as a weight-correction mechanism, the proposed framework extends this utility by integrating a dynamic simulation layer capable of modeling complex, non-linear feedback loops—via the generalized non-linear influence function—for scenario-based ranking. The primary contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

Two MCDM Methodologies: We introduce two novel frameworks: (1) an enhanced New Fuzzy Digraph [

3] (NFD) method that utilizes an FCM as a corrective layer to refine expert judgments, and (2) a fully FCM-based Decision Making (FCM_DM) method that leverages causal relationships for dynamic analysis.

Modeling of Interdependencies: Both methods are explicitly designed to address the profound challenge of modeling complex interdependencies, including dependence and feedback loops, among decision criteria, a significant limitation in standard MCDM approaches.

Dynamic Scenario Analysis: The FCM_DM method, in particular, offers a flexible framework for ranking alternatives under varying scenarios, a feature that allows decision-makers to explore different causal relationships and their impact on outcomes.

A New Comparison Metric: We propose a modification of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient that assigns different weights to alternatives based on their ranking positions, enabling more meaningful and nuanced comparisons between MCDM methods.

To demonstrate the applicability and effectiveness of this framework, we apply it to the complex case of industrial robot selection. This domain is a fitting testbed, as it requires balancing numerous performance metrics, cost-based parameters, and technological capabilities. Recent research advances in this problem, as seen in comparative analyses [

35,

36], continue to refine the decision-making process. This includes the development of new hybrid models [

37,

38] and frameworks to address specific challenges like group decision-making [

39] and detailed performance evaluation [

40,

41].

The rest of the paper is organized to systematically present the proposed methodologies and their applications.

Section 2.1.1,

Section 2.1.2 and

Section 2.1.3 establish the essential background by discussing mathematical conventions, FCMs, and the foundational FD method [

3]. Next,

Section 2.2 details the suggested MCDM methodologies (

Section 2.2.1 and

Section 2.2.2), followed by

Section 2.3, which provides a numerical example to illustrate how these methods are applied and how effective they can be.

Section 3 presents an experimental analysis, while

Section 4 offers concluding remarks that tie together the main insights and implications of this research, especially concerning industrial robot selection.

2. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the methodological framework of the study, structured to guide the reader from established theory to the proposed innovations. It is organized into three distinct parts: first, the essential theoretical prerequisites and mathematical conventions are reviewed; second, the two novel cognitive decision-making methodologies (NFD and FCM_DM) are formally introduced; and third, a comprehensive numerical example is provided to demonstrate the practical application of these methods in an industrial robot selection scenario.

2.1. Theoretical Background

The following subsections detail the foundational concepts and mathematical tools upon which the proposed framework is built. This includes the definition of notations to ensure consistency, an examination of FCMs regarding their inference mechanisms and non-linear capabilities, and an analysis of the standard FD method, which serves as the structural baseline for the enhanced approaches developed in this work.

2.1.1. Mathematical Conventions/Notations

This subsection defines the essential mathematical conventions to ensure consistency throughout the work. Matrices are written using uppercase letters (e.g., A, B, Q); vectors appear as bold lowercase letters (e.g., , , ); and scalars are indicated by plain lowercase letters (e.g., n, m, k). For example, the element of a matrix in row i and column j is represented as , while the i-th element of a vector is written as .

To represent fuzzy quantities, a hat (^) is placed over the symbol, such as fuzzy matrices (e.g.,

), fuzzy vectors (e.g.,

), and fuzzy numbers (e.g.,

). A fuzzy number can be further expressed as a triplet of real values

. While this work utilizes triangular fuzzy numbers [

42] (represented by these triplets) for their computational efficiency and intuitive definition by experts [

43], the proposed methodologies are not structurally limited to this form. Other representations, such as trapezoidal or Gaussian membership functions, could also be integrated.

2.1.2. Fuzzy Cognitive Maps

Building upon these mathematical conventions, we first examine the primary cognitive modeling tool used in this framework. FCMs, introduced by Kosko [

14], expand on the idea of cognitive mapping by integrating fuzzy logic. They are usually represented as directed, signed graphs composed of nodes (which stand for concepts) and weighted arcs (showing cause-effect relationships among nodes). Each node can influence others and, at the same time, be influenced by them, thus capturing the system’s underlying interdependencies. The state of each node at time

t, denoted as

, evolves over time, representing the node’s current condition.

Typically, the state of a node

is defined inside the interval

, though sometimes it is extended to

for broader applications, while the strength of the influence from node

i to node

j is quantified by a weight

, which usually falls either within

or

, depending on the context. The rectangular weight matrix

W, which defines the topology of the FCM, is usually derived from expert knowledge. To represent fuzzy relationships, a fuzzy weight matrix

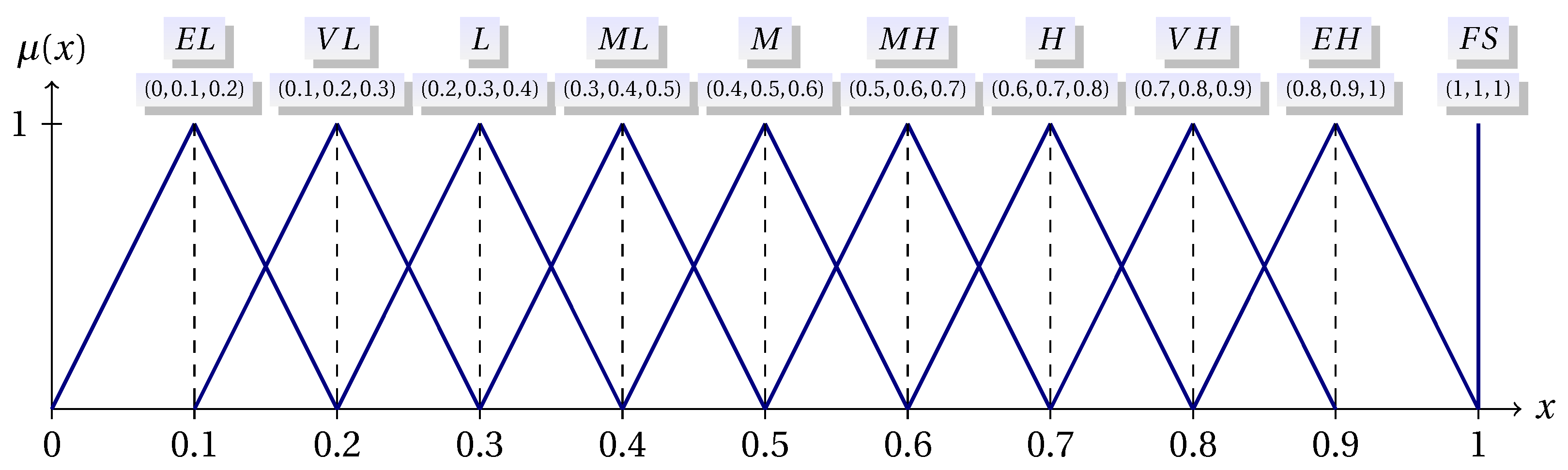

can be used, where linguistic values such as “low,” “medium,” and “high”, whose membership functions are illustrated in

Figure 1, quantify the strength of influences. The defuzzified version of

, denoted as

W, is often used in calculations.

In a traditional FCM, crisp values are assigned to both the states of the nodes and the weights between them, while the state of the nodes at the next time step,

is computed through the updating rule of Equation (

1) [

44]:

where

is a

real-valued vector representing the initial state which is determined by the problem and

is a threshold function applied element-wise to normalize the state values, ensuring they remain within the specified range, often

or

. Two commonly used threshold functions are given by Equations (

2) and (

3):

These functions help model the nonlinear behavior of node state updates [

45]. When applied to a matrix

A, the threshold function is applied element-wise.

By iterating the update rule, FCMs can reach one of three possible equilibrium states:

- 1.

A fixed point, where the states no longer change ().

- 2.

A limit cycle, where states repeat in a cycle over time ().

- 3.

A chaotic state, where all states differ from one another and the system continues to evolve indefinitely ().

In addition to the traditional form of FCMs, where crisp values are used for the connection matrix

W and node states, an alternative formulation can be employed. This alternative approach utilizes linguistic/fuzzy values for constructing the fuzzy connection matrix

and for calculating the steady state of the system using a fuzzy inference mechanism, as demonstrated in ref. [

28]. In this case, the traditional updating rule of Equation (

1) is transformed into its fuzzy version of Equation (

4):

where the function

represents the fuzzy version of the threshold function, which processes fuzzy numbers instead of crisp ones.

The fuzzy version of the threshold function can be expressed using common thresholding approaches, such as the logistic function or the hyperbolic tangent function. Given a fuzzy number

, where

,

, and

represent the lower, middle, and upper bounds of the fuzzy number, respectively, the logistic and hyperbolic tangent functions can be extended to fuzzy numbers as follows (Equations (

5) and (

6)):

In these expressions, each element of the fuzzy number is processed individually, and the resulting fuzzy number is a triplet representing the transformed values.

When applying the fuzzy threshold function to a fuzzy matrix , the operation is performed element-wise. For a fuzzy matrix , the fuzzy threshold function is applied to each element: . This process allows for the propagation of fuzzy states and weights throughout the FCM, enabling the system to capture and handle uncertainty or imprecision inherent in complex decision-making environments.

Inference Mechanism and Non-Traditional Influence

In traditional FCMs, the influence

of one node

i on another node

j is calculated by multiplying the current state of node

i (denoted as

) with the connection weight between the two nodes

. This is expressed mathematically in Equation (

7):

while effective in many situations, this method assumes a simple, linear relationship between nodes, which may not accurately reflect the complex, non-linear interactions found in real-world decision-making problems.

To capture these complex relationships, a generalized, non-linear influence function was proposed in ref. [

46]. This function extends the traditional mechanism by using parameters to fine-tune the shape and intensity of the influence curve. The generalized influence function is expressed in Equation (

8) as:

where

is the generalized logistic function [

47], defined by Equation (

9) as:

In this equation, the parameters

control the shape and intensity of the influence curve. The traditional influence model is just a special case of this function and can be expressed as

. By adjusting these parameters, we can capture more complex and nuanced relationships between the nodes.

The influence of node

i on node

j, using the non-traditional mechanism, is represented in Equations (

10) and (

11) as:

where

is a compact notation for representing the non-traditional influence.

Here, the standard multiplication of state and weight is replaced by a non-linear function to capture complex interactions. The entire system is expressed in Equation (

12):

where

represents the non-traditional influence, while

denotes the threshold function (typically logistic or hyperbolic tangent) that maps the updated state

to the interval

or

.

This non-traditional influence mechanism extends the flexibility of FCMs by allowing more dynamic, non-linear relationships between criteria. It is especially useful for modeling real-world systems where influence is not strictly proportional and can vary based on different conditions.

The notation

compactly represents this non-linear mechanism that results in the vector defined in Equation (

13):

where

represents the column

j of matrix

W.

The extension of Equation (11) to its fuzzy version

is a straightforward process given by Equation (15).

where

and

. In this context, the fuzzy version of the non-traditional inference mechanism can be defined as

.

2.1.3. The Standard Fuzzy Digraph Method

While FCMs provide a dynamic mechanism for modeling complex causality, the structural basis of our first proposed methodology rests on a more static graph-based ranking approach, known as the FD. The FD model, introduced in ref. [

3], combines fuzzy logic with the structure of a directed graph (digraph) in order to provide a robust decision-making framework. In the context of decision-making problems, where there are

z potential alternatives and

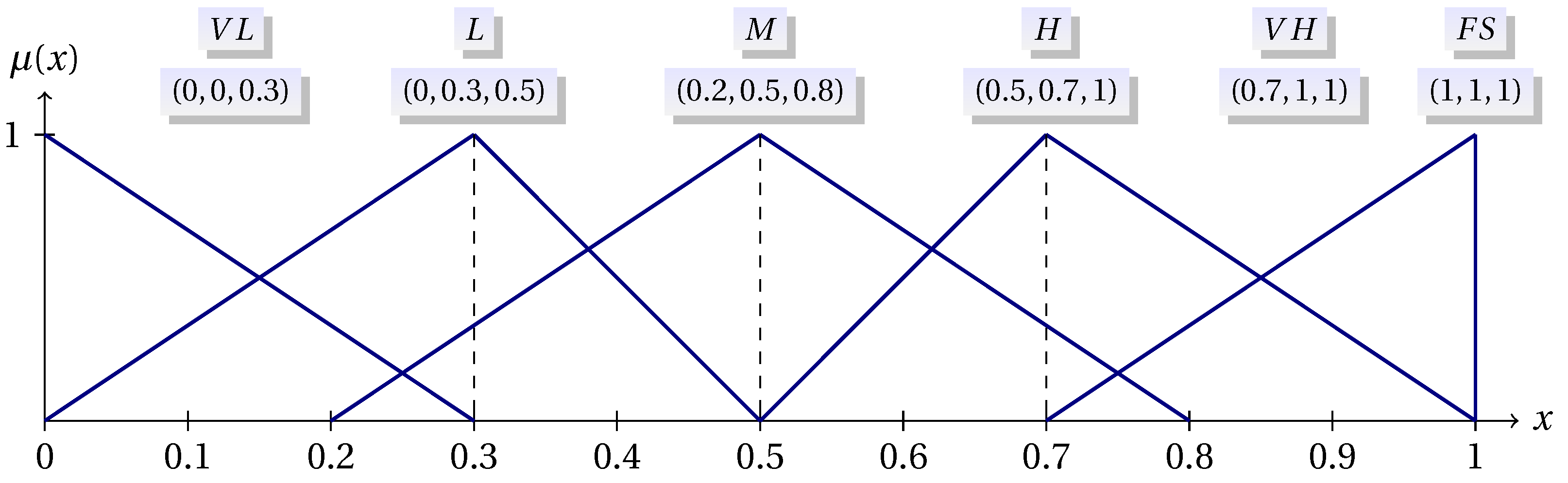

n criteria (which can be subjective or objective),

m decision-makers assign fuzzy weights

to each criterion. These weights reflect the experts’ opinions on the importance of each criterion

i (where

and

). Indicative membership functions of the linguistic values, which are used for representing experts’ opinion, are presented in

Figure 2.

Each criterion can be classified as either a cost or benefit type, depending on whether higher values are preferable (benefit) or lower values are more desirable (cost). For simplicity, this section assumes that all the criteria are objective and benefit-based.

Step 1: Fuzzy Average Importance Vector

The first step of the FD method involves calculating the fuzzy average importance vector

, which aggregates the importance weights assigned by all decision-makers (Equation (

16)):

This vector represents the overall importance of each criterion for the decision-making process.

Step 2: Normalization of Fuzzy Values

Next, the fuzzy values for each criterion are normalized to ensure they fall within the range

. The normalization process differs depending on whether the criterion is subjective or objective and whether it is a cost or benefit. In this case, where all criteria are objective and benefit-based, the normalization Equation (

17) is as follows:

where

,

,

,

and

is the upper bound of the fuzzy number of the

criterion across all alternatives. This process ensures that all the components of the normalized fuzzy numbers remain ≤ 1.

Step 3: Fuzzy Average Importance Vector Normalization

From the fuzzy average importance vector

, a normalized fuzzy average importance vector

is derived using Equations (

18) and (

19). This normalized vector forms the basis for generating the Relative Importance (RI) Matrix, which represents the interrelations between criteria.

where

is the defuzzified value of

, while

is the upper bound of the fuzzy number of the

t-

th element of fuzzy vector

(i.e.,

,

).

2.2. Proposed Methodologies

This subsection introduces two new methodologies for multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM). The first one is a modification of the previously mentioned FD method [

3], aiming to enhance its ability to address the dependence and feedback among the criteria and their interrelations. The main difference from the original one (a key contribution of this work) is the use of an FCM for correcting potential expert misjudgments regarding the importance of criteria for a specific problem. The second method is based entirely on FCMs, which provide a dynamic and flexible approach for ranking alternatives, allowing the examination of various scenarios by taking into account the causal relationships between criteria. Both methods are capable of handling crisp or fuzzy data, yet, for the sake of consistency, this paper focuses on their fuzzy versions, as their crisp counterparts can be easily derived.

This article proposes two distinct methodologies to systematically investigate the impact of integrating a Fuzzy Cognitive Map (FCM) as a corrective mechanism within a MCDM framework. The primary objective was to explore how an initial FCM-based correction of expert-provided criteria weights would affect the final rankings of an established method. For this purpose, the FD method was specifically chosen as the foundational model due to its inherent structure, which, like an FCM, is built upon a directed graph to model interrelations among criteria. This structural alignment makes it a uniquely suitable candidate for enhancement, as both methods share a conceptual basis in representing causal relationships.

By presenting the enhanced NFD, the research directly assesses this integration, treating the FCM as a pre-processing step to refine inputs by modeling deeper criteria interdependencies. Simultaneously, the novel FCM_DM method was introduced as a benchmark and a more radical application, using the same corrected weights but within a fully dynamic FCM structure for ranking. This dual approach allows for a direct comparison, demonstrating both an evolutionary enhancement to a structurally compatible model and a revolutionary, fully FCM-driven alternative. This provides a comprehensive analysis of the FCM’s utility in complex decision-making, showcasing its power both as a corrective layer for a related method and as a standalone ranking framework.

To clearly explain the proposed methodologies, let us define a decision-making problem involving z alternatives and n criteria (attributes). For each criterion i (where ), which can be either objective or subjective, decision-makers assign a fuzzy weight , where , representing the importance of the criterion. The experts also provide a Fuzzy Cognitive Map (FCM) topology by defining the fuzzy connection matrix , where each node corresponds to a criterion. It is assumed, for simplicity, that all criteria are objective and benefit-oriented.

2.2.1. New Fuzzy Digraph

Similar to many decision-making algorithms, this method comprises two main phases: (1) Data Processing and (2) Ranking Alternatives. In the first phase, the data are processed to ensure they are in the appropriate form. Experts’ opinions on the importance of each criterion, as well as the values of the criteria, are averaged and normalized. The second phase focuses on producing a ranking vector, which is used to order the alternatives according to their suitability.

Data Processing

The first step in the NFD method is to compute the fuzzy average importance vector

by using Equation (

24):

where

is the fuzzy weights matrix. Normalization of the fuzzy average importance vector

is then carried out to produce the fuzzy normalized vector

(using Equation (

19)). However, the proposed NFD method employs an FCM-based correction mechanism (proposed in [

27]) to address potential errors in the estimation of the normalized importance vector

.

Initially, an FCM is used, and the connection matrix

is provided by the experts. Using the initial state

, which is set as the identity matrix

, the fuzzy steady-state matrix

is calculated using the following iterative Equation (

25):

where

is the fuzzy version of the threshold function. After obtaining the steady-state matrix

, the corrected normalized fuzzy average importance vector

is calculated as shown in Equations (

26) and (

27):

where

is the maximum defuzzified summation of the rows of

,

,

and

is the defuzzified version of fuzzy vector

.

Since all the criteria have been transformed to be objective and benefit, the fuzzy values of criteria

, where

and

, are normalized according to Equation (

17) in order for the normalized criteria values

to be produced.

Ranking Alternatives—Using Decision Matrix & Positive Determinant

With the corrected normalized fuzzy importance vector

already calculated, the next step is to compute the relative importance matrix

by using Equation (

28):

Finally, the decision matrix

is formed by replacing the diagonal elements

,

, with the normalized criteria values

, for each alternative

. The ranking of alternatives is obtained by calculating and defuzzifying the positive determinant of the decision matrix (Equation (

29)):

The higher the

value, the more suitable the alternative.

Pseudocode for both the NFD method is presented in Algorithm 1.

2.2.2. Decision Making Using Fuzzy Cognitive Maps

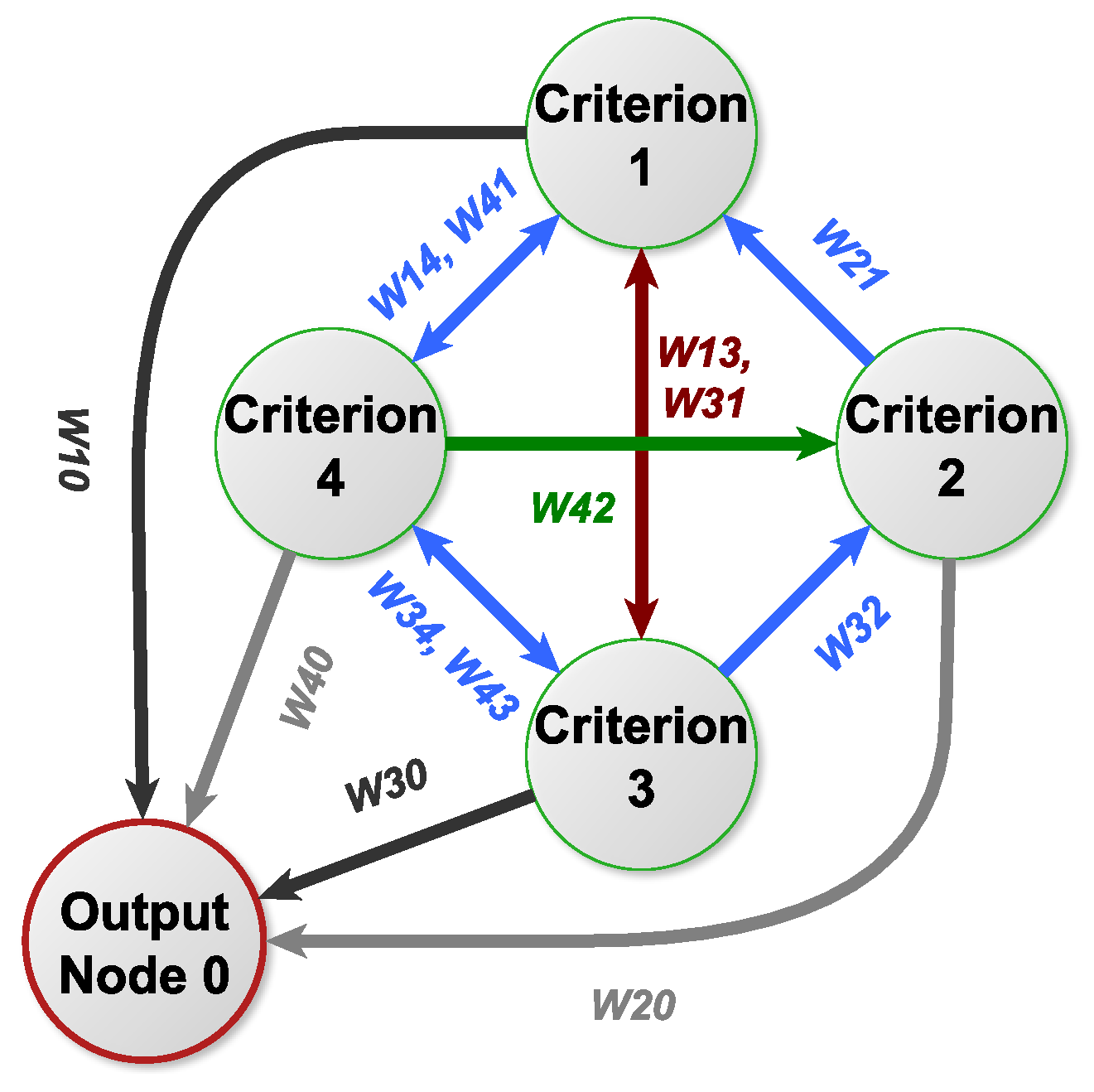

In contrast to the previous method, which utilizes FCMs merely as a corrective layer for static weights, the following approach leverages the full computational power of FCMs to perform dynamic scenario-based ranking. FCMs offer a structured way to model the relationships between concepts by simulating influences and interrelations among them. In the FCM-based proposed method, each criterion is represented as a node in an FCM, while a connection matrix

is provided by experts to capture inter-criteria influences. This structure needs one additional element in order to rank alternatives. This element is an additional output node, which is influenced by all other nodes (see

Figure 3). The value of this output node, once the FCM system reaches a steady state, is used to rank the alternatives.

The data processing phase is the same as the one described in the section on new fuzzy digraph and given the connection matrix

, its modified version

, which also includes the output node, is given by Equation (

30):

where

is the transposed corrected normalized fuzzy average importance vector calculated by Equation (

27). The steady state is reached by iterating the update rule of Equation (

31):

The initial state

is defined using the normalized values of the criteria for each alternative (

). The last element of

represents the output node.

To extend the inference mechanism of Equation (

31) to its non-traditional version, the rule of Equation (

32) is used:

where

is defined in the section on inference mechanism and non-traditional influence.

| Algorithm 1 Pseudocode for the NFD method, detailing the procedure for correcting expert weights via an FCM steady-state calculation before constructing the Relative Importance Matrix and computing the positive determinant for ranking |

- 1:

Input: Fuzzy weights , connection matrix , criteria values - 2:

Output: - 3:

▹ Aggregate expert weights - 4:

▹ Normalize weights to comparable range - 5:

▹ Initialize steady-state matrix - 6:

repeat ▹ Loop until FCM converges - 7:

- 8:

- 9:

until - 10:

▹ Apply FCM correction - 11:

- 12:

▹ Compute importance matrix - 13:

- 14:

for to z do - 15:

▹ Initialize decision matrix for Alt k - 16:

for to n do - 17:

▹ Replace diagonal with values - 18:

end for - 19:

▹ Compute final rank score - 20:

- 21:

end for - 22:

- 23:

return

|

Finally, the ranking procedure takes place using either the traditional or non-traditional inference mechanism until a steady state is reached for each alternative. The defuzzified value of the output node at steady state indicates the position of each alternative, with higher values indicate better alternatives.

To formally outline the complete procedure, pseudocode for both the FCM-DM method is presented in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Pseudocode for the FCM-DM method, detailing the construction of the augmented connection matrix () and the iterative simulation process used to derive a ranking score from the Output Node |

- 1:

Input: Fuzzy weights , connection matrix , criteria values - 2:

Output: - 3:

▹ Aggregate expert weights - 4:

▹ Normalize weights to comparable range - 5:

▹ Initialize steady-state matrix - 6:

repeat ▹ Loop until FCM converges - 7:

- 8:

- 9:

until - 10:

▹ Apply FCM correction - 11:

▹ Normalize criteria values - 12:

▹ Create augmented matrix - 13:

- 14:

▹ Link criteria to Output Node - 15:

- 16:

for to z do - 17:

▹ Init state vector for Alt k - 18:

repeat ▹ Simulate system evolution - 19:

- 20:

- 21:

until - 22:

▹ Extract Output Node score - 23:

- 24:

end for - 25:

- 26:

return

|

2.3. Numerical Example

To bridge the gap between the theoretical formulation of the NFD and FCM_DM algorithms and their practical implementation, we apply both methodologies to a concrete decision-making scenario. In this section, a numerical example to clarify and demonstrate the steps of each proposed decision-making method is presented. The example includes a robot selection problem, where five different robot alternatives are evaluated based on four criteria, the fuzzy values of which are listed in

Table 1. The criteria are considered objective and benefit-oriented, meaning that higher values are preferred. Four experts are consulted to provide their opinions about the importance of each criterion as well as to define the interrelations among the criteria.

The proposed methods result in four variants for each decision-making methodology. These variants arise from two key decisions: (1) whether to use the traditional (crisp/defuzzified) or fuzzy inference mechanism and (2) whether to use traditional (linear) or non-traditional (nonlinear) influence among the criteria. Thus, each method has four versions as is illustrated in

Table 2 where this taxonomy is detailed. The selection among these variants depends on the specific requirements of the decision problem. The Linear variants (NFD-LI, FCM-LI) are preferable when the relationships between criteria are straightforward and proportional, offering computational simplicity. Conversely, the Non-Linear variants (NFD-NLI, FCM-NLI) are better suited for complex environments where influence saturation occurs (e.g., diminishing returns). Regarding uncertainty, the Fuzzy versions are essential when expert inputs are vague or linguistic, whereas Crisp versions suffice for problems with precise, deterministic data. In this example, only the NFDFLI (New Fuzzy Digraph-Fuzzy version-Linear Influence) and FCMFLI (Fuzzy Cognitive Maps-Fuzzy version-Linear Influence) variants are demonstrated as indicative examples.

2.3.1. Example Setup

For the purpose of this example, the following assumptions are made:

2.3.2. Data Processing

The first phase involves processing the expert data, which is a common prerequisite for both the NFD and FCM_DM methods.

- Step1:

Averaging Expert Opinions. First, the fuzzy weights provided by the four experts in

Table 3 are aggregated. Using Equation (

16), we compute the fuzzy average importance vector

. The result of this averaging is shown in the first row of

Table 5.

- Step2:

Normalization. Next, this average vector

is normalized to produce

using Equation (

19). This step ensures all values fall within a comparable range. The resulting normalized fuzzy average importance vector

is presented in the second row of

Table 5.

- Step3:

Correcting Normalized Importance. To account for criteria interdependencies, we apply the FCM-based correction. The iterative Equation (

25) is applied, using the fuzzy connection matrix

from

Table 4 and an initial state

. This process is repeated until the system reaches a fuzzy steady-state matrix,

. This steady-state matrix

and the vector

are then used in Equations (

26) and (

27) to calculate the final corrected normalized fuzzy average importance vector,

. This final corrected vector, which reflects the dynamic influences between criteria, is shown in the third row of

Table 5.

Table 5.

Computational progression of criteria importance, displaying the values for the Average (), Normalized () and final FCM-Corrected () vectors used to adjust for interdependencies.

Table 5.

Computational progression of criteria importance, displaying the values for the Average (), Normalized () and final FCM-Corrected () vectors used to adjust for interdependencies.

| Fuzzy Importance Vectors | Criterion1 | Criterion2 | Criterion3 | Criterion4 |

|---|

| Average () | (0.400, 0.500, 0.600) | (0.350, 0.450, 0.550) | (0.375, 0.475, 0.575) | (0.500, 0.600, 0.700) |

| Normalized () | (0.198, 0.247, 0.296) | (0.173, 0.222, 0.272) | (0.185, 0.235, 0.284) | (0.247, 0.296, 0.346) |

| Corrected () | (0.194, 0.285, 0.408) | (0.123, 0.201, 0.315) | (0.172, 0.267, 0.398) | (0.158, 0.207, 0.273) |

2.3.3. NFDFLI Method Calculation

With the corrected vector

from

Table 5, we now proceed with the NFDFLI (New Fuzzy Digraph-Fuzzy version-Linear Influence) method.

- Step4:

Compute Relative Importance Matrix. The corrected vector

is used as the input for Equation (

28) to compute the new relative importance matrix,

. This matrix, which quantifies the relative importance between pairs of criteria, is presented in

Table 6.

- Step5:

Form the Decision Matrix. A unique decision matrix

is formed for each robot alternative. This is done by taking the matrix

, detailed in

Table 6 and replacing its diagonal elements with the normalized criteria values (

) for that specific alternative from

Table 1. For example,

Table 7 shows the completed decision matrix for Robot 1.

- Step6:

Calculate Final Score. Finally, the ranking score

for Robot 1 is calculated by applying the fuzzy positive determinant function to its decision matrix (presented in

Table 7) and then defuzzifying the result, as defined in Equation (

22). This process is repeated for the other four robot alternatives to obtain their final scores.

Table 6.

The calculated New Relative Importance Matrix (), derived using the corrected importance vector () to establish the relative importance weight between every pair of criteria.

Table 6.

The calculated New Relative Importance Matrix (), derived using the corrected importance vector () to establish the relative importance weight between every pair of criteria.

| Criterion1 | Criterion2 | Criterion3 | Criterion4 |

|---|

| Criterion1 | (0.000, 0.000, 0.000) | (0.91, 1.339, 1.916) | (0.695, 1.022, 1.463) | (0.912, 1.343, 1.921) |

| Criterion2 | (0.416, 0.678, 1.067) | (0.000, 0.000, 0.000) | (0.441, 0.719, 1.131) | (0.579, 0.944, 1.485) |

| Criterion3 | (0.583, 0.903, 1.344) | (0.81, 1.253, 1.866) | (0.000, 0.000, 0.000) | (0.812, 1.256, 1.871) |

| Criterion4 | (0.533, 0.699, 0.923) | (0.74, 0.971, 1.282) | (0.565, 0.741, 0.979) | (0.000, 0.000, 0.000) |

Table 7.

The Decision Matrix () constructed for Robot 1, formed by replacing the diagonal elements of the Relative Importance Matrix with Robot 1’s normalized criterion values.

Table 7.

The Decision Matrix () constructed for Robot 1, formed by replacing the diagonal elements of the Relative Importance Matrix with Robot 1’s normalized criterion values.

| Criterion1 | Criterion2 | Criterion3 | Criterion4 |

|---|

| Criterion1 | (0.696, 0.796, 0.896) | (0.91, 1.339, 1.916) | (0.695, 1.022, 1.463) | (0.912, 1.343, 1.921) |

| Criterion2 | (0.416, 0.678, 1.067) | (0.648, 0.748, 0.848) | (0.441, 0.719, 1.131) | (0.579, 0.944, 1.485) |

| Criterion3 | (0.583, 0.903, 1.344) | (0.81, 1.253, 1.866) | (0.000, 0.022, 0.122) | (0.812, 1.256, 1.871) |

| Criterion4 | (0.533, 0.699, 0.923) | (0.74, 0.971, 1.282) | (0.565, 0.741, 0.979) | (0.154, 0.254, 0.354) |

2.3.4. FCMFLI Method Calculation

For the FCMFLI (Fuzzy Cognitive Maps-Fuzzy version-Linear Influence) method, we use the processed data in a different, dynamic simulation.

- Step4:

Form the Modified Connection Matrix. The fuzzy connection matrix

from

Table 4 is modified to include the output node, as specified by Equation (

30). The corrected importance vector

(the values of which are illustrated in

Table 5) is inserted as the column of weights leading to this new output node. The resulting modified connection matrix

is shown in

Table 8.

- Step5:

Define the Initial State. A unique initial state vector

is created for each alternative. This vector is formed using the normalized criteria values (

) from

Table 1, with the output node’s initial value set to (0, 0, 0). The initial state vector for Robot 1 is shown in the first column of

Table 9.

- Step6:

Run FCM Simulation to Steady State. The FCM updating function, Equation (

31), is applied iteratively, using the initial state for Robot 1 (shown in

Table 9) and the modified matrix

(displayed in

Table 8). This simulation continues until the system reaches a steady state. The second column of

Table 9 shows the final steady-state vector for Robot 1. The defuzzified value of the output node at this steady state provides the final ranking score. This procedure is repeated for the remaining four robots.

Table 8.

The Modified Connection Matrix () used in the FCM-DM method, which augments the original criteria matrix () by adding a fifth column (Output Node) populated with the corrected importance weights.

Table 8.

The Modified Connection Matrix () used in the FCM-DM method, which augments the original criteria matrix () by adding a fifth column (Output Node) populated with the corrected importance weights.

| Criterion1 | Criterion2 | Criterion3 | Criterion4 | Output Node |

|---|

| Criterion1 | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) | (0.3, 0.4, 0.5) | (0.7, 0.8, 0.9) | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) | (0.194, 0.285, 0.408) |

| Criterion2 | (0.2, 0.3, 0.4) | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) | (0.0, 0.1, 0.2) | (0.0, 0.1, 0.2) | (0.123, 0.201, 0.315) |

| Criterion3 | (0.0, 0.1, 0.2) | (0.8, 0.9, 1.0) | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) | (0.2, 0.3, 0.4) | (0.172, 0.267, 0.398) |

| Criterion4 | (0.1, 0.2, 0.3) | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) | (0.158, 0.207, 0.273) |

| Output Node | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) | (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) |

Table 9.

Simulation results for Robot 1 using the FCM-DM method, comparing the values of the Initial State vector () against the converged Steady State vector ().

Table 9.

Simulation results for Robot 1 using the FCM-DM method, comparing the values of the Initial State vector () against the converged Steady State vector ().

| | Initial State () | Steady State () |

|---|

| Criterion1 | (0.696, 0.796, 0.896) | (0.096, 0.227, 0.433) |

| Criterion2 | (0.648, 0.748, 0.848 | (0.223, 0.389, 0.610) |

| Criterion3 | (0.000, 0.022, 0.122) | (0.270, 0.435, 0.631) |

| Criterion4 | (0.154, 0.254, 0.354) | (0.027, 0.125, 0.288) |

| Output Node | (0.000, 0.000, 0.000) | (0.166, 0.345, 0.628) |

2.3.5. Example Results

Both the NFDFLI and FCMFLI methods result in the same final ranking for the five robot alternatives: [4, 5, 3, 2, 1]. This indicates that, while the methods differ in their approach, they produce consistent rankings for this particular example.

3. Results

In this section, we evaluate the proposed decision-making methods by comparing their ranking performance with other widely used methodologies.

3.1. Ranking Correlation with Other Methods

The proposed methods and all of their variants are compared with several established methods, such as the traditional FD [

3], Topsis [

49], Fuzzy Topsis (FzTopsis) [

12], and Fuzzy MCDM (FzMCDM) [

50]. Their ranking results are correlated using a modified metric,

, which is derived from the standard Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient

, which is givenby Equation (

33).

In its original form, Spearman’s correlation coefficient

takes values within the range

, where

indicates perfect positive correlation,

indicates perfect negative correlation, and

indicates no correlation. However, to make the correlation easier to interpret within this context, the domain of

is shifted from

to

, resulting in a modified metric

, which simplifies interpretation by ensuring that all the correlation values are positive [

51]. The relationship between

and

is defined in Equation (

34):

Thus,

, where values closer to 1 indicate stronger agreement between the rankings produced by two methods, while values near 0 indicate weaker correlation. The transformed SRCC

is calculated as defined in Equation (

35):

where

and

,

, represent the ranks from the two different decision-making methods

A and

B, while

and

are the average ranks for each method.

To further refine the correlation analysis, a weighted version of the SRCC is introduced, where more importance is given to higher-ranked alternatives. The weighted SRCC formula isgiven by Equation (

36):

where

,

, represents the weights assigned to the ranks, giving more significance to top-ranked items. For

, the weights

are calculated by using Equation (

37):

The comparison between

and

coefficients for different rankings is presented in

Table 10.

3.2. Experimental Setup & Parameter Selection

To perform a robust comparison of the methods, a random example generator was implemented to create 250 distinct test cases. This generator is defined by the following procedures:

- 1.

Generation of Criteria Values: For each of the alternatives, their criteria values were generated as triangular fuzzy numbers. The modal value of each number was sampled from a uniform distribution . The lower and upper bounds were then set as and , respectively, to create consistent fuzzy numbers. All criteria were treated as objective and benefit for simplicity.

- 2.

Generation of Expert Opinions (Matrix ): To simulate the input from

experts, the fuzzy importance weights for each of the

criteria were generated using the same process as above. This produced a

matrix of

triangular fuzzy numbers, which was then averaged (Equation (

24)) to create the fuzzy average importance vector

for each test case.

- 3.

Generation of the FCM Connection Matrix (): For each test case, a new fuzzy connection matrix was generated. The diagonal elements were set to (0, 0, 0). A random sparsity p (e.g., ) was first determined. For each off-diagonal element, a random number was drawn from ; if it exceeded the sparsity threshold p, the element was set to (0, 0, 0). Otherwise, it was generated as a non-zero triangular fuzzy number with a modal value sampled from and bounds set at and . To ensure a meaningful causal structure, a check was performed to guarantee a minimum number of n non-zero edges (criteria pairs) were generated (these minimum n edges must not include pairs with same indices, e.g., and ); if not, the process for the matrix was repeated. This process creates a sparse, random topology for each simulation, reflecting more realistic causal structures.

The values of criteria and alternatives were chosen for two primary reasons: first, they represent a common, small-scale MCDM problem, and second, they allow for a direct conceptual comparison with the single illustrative numerical example. While this experiment focuses on this scale, the proposed methodologies are algorithmically scalable to problems with significantly larger n and z.

The analysis of the non-linear versions of the methods used the non-traditional influence mechanism of Equation (

32). For this, the parameters were set to

,

, and

. These values were selected based on our previous work [

46], which demonstrated that this specific configuration provides a distinct, sigmoidal non-linear influence curve that fits well around the traditional linear influence. The 250 simulation runs were determined to be sufficient to provide a stable mean for the Spearman’s correlation coefficients, ensuring the reliability of the comparison.

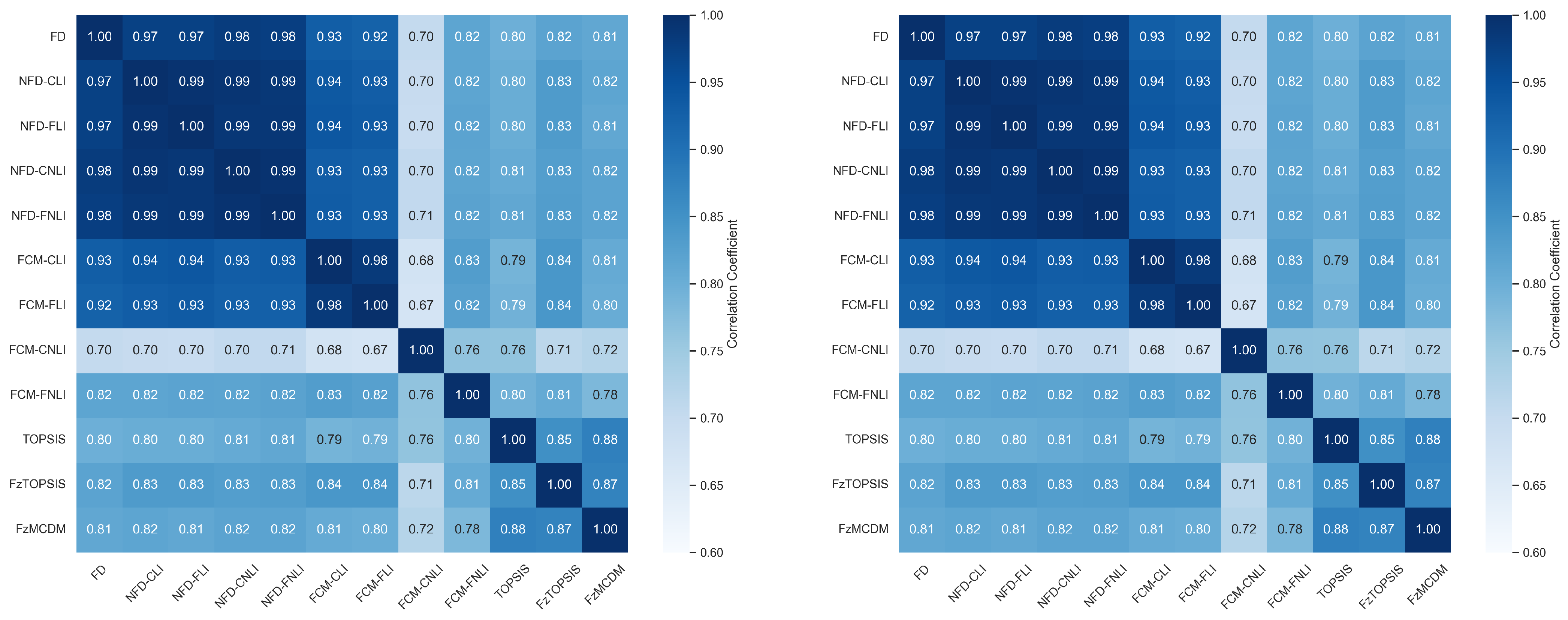

3.3. Mean and Weighted Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients

Figure 4, which presents the correlation heatmaps, reveals a high level of consistency between the traditional FD method and its non-linear and fuzzy variants (NFDCLI, NFDFLI, NFDCNLI, and NFDFNLI) can be observed. The correlation coefficients, ranging from

to

, indicate a very high positive correlation for both of the used types (SRCC and its weighted version). This suggests that while non-linear and fuzzy elements introduce additional flexibility, they do not significantly alter the core ranking structure of the FD-based methods, particularly for top-ranked alternatives.

In contrast, the Fuzzy Cognitive Map (FCM) based variants (FCMCLI, FCMFLI, FCMCNLI, and FCMFNLI) present higher variability. The correlation values between the linear and non-linear FCM methods, as well as their crisp and fuzzy variants, fall within the range of to , and although these values indicate positive correlation, they reflect only moderate consistency between the methods. This suggests that the introduction of non-linearity and fuzziness in FCM methods results in more diverse rankings, especially for top alternatives, offering greater flexibility but at the cost of a reduced ranking alignment.

The correlation between TOPSIS and Fuzzy TOPSIS (FzTOPSIS) is (SRCC) and (weighted SRCC), which can be interpreted as moderate-to-high. While the two methods are strongly aligned, the introduction of fuzziness in FzTOPSIS introduces some divergence from the crisp TOPSIS method, and this becomes more apparent when the alternatives are characterized by uncertain or imprecise criteria.

Interestingly, the correlation between TOPSIS and Fuzzy MCDM (FzMCDM) is slightly higher, with (SRCC) and (weighted SRCC), which clearly indicates that FzMCDM aligns more closely with the ranking behavior of TOPSIS, even when incorporating fuzziness.

In summary, the heatmaps in

Figure 4 visually distinguish two dominant behaviors: (1) a ‘stability cluster’ comprising the NFD variants and the foundational FD, which show minimal deviation, and (2) a ‘dynamic cluster’ within the FCM variants, where non-linearity significantly diversifies the rankings. This contrast underscores the practical distinction between the two proposed frameworks: NFD serves as a consistent refinement tool, whereas FCM_DM acts as a flexible mechanism for exploring diverse causal scenarios.

3.4. Percentage of Identical Rankings

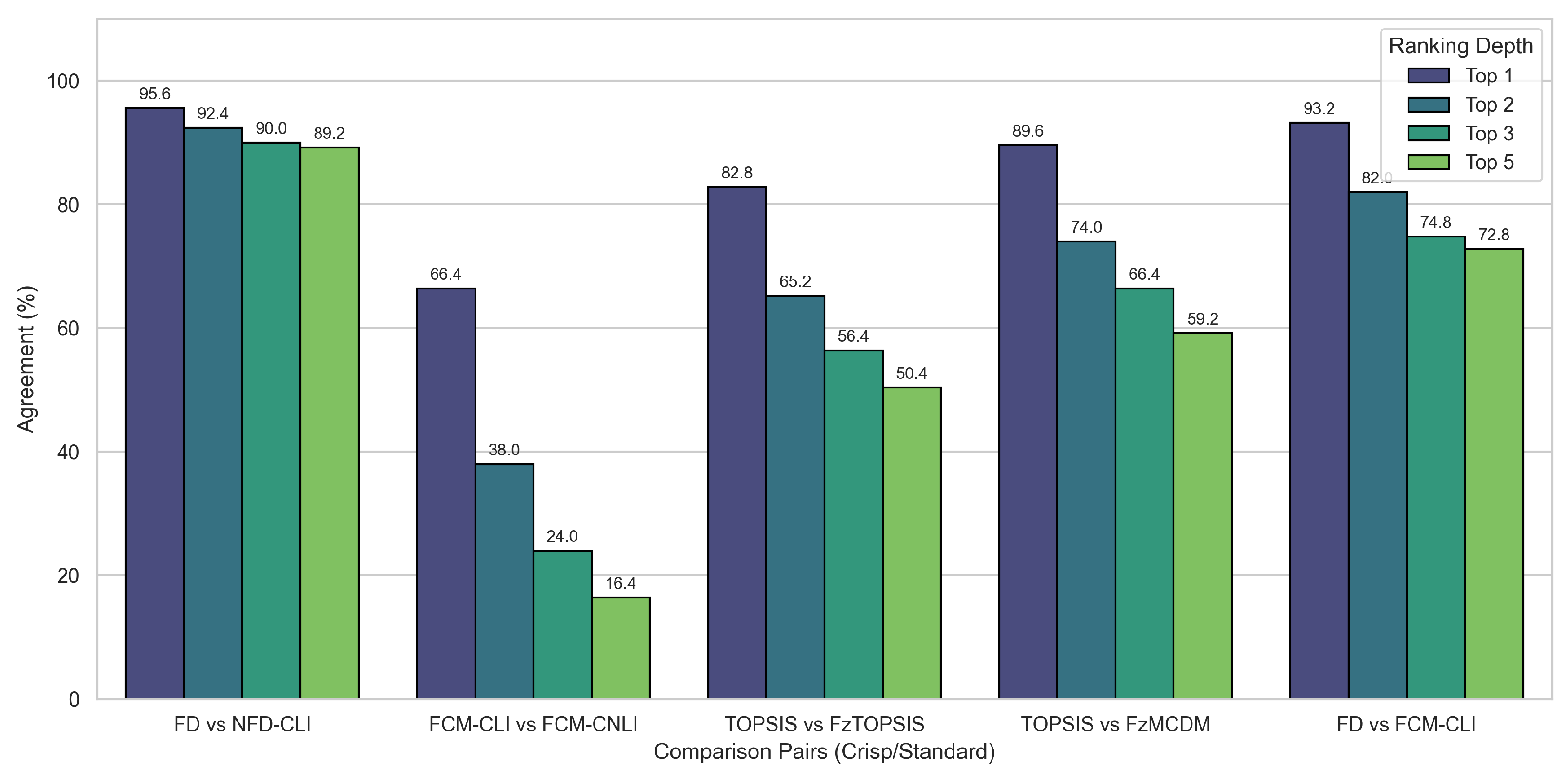

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the percentage of identical rankings between methods when considering the top one, two, three, four, and five positions. These results agree with the conclusions from the previous correlation analysis.

FD and Its Variants (Stability): The FD method and its non-linear variants show high percentages of identical rankings, particularly for the top positions.

Figure 5, which groups the agreement percentages for crisp variants, indicates that FD and NFDCLI share 95.6% of their top 1 rankings and 89.2% of their top 5 rankings. This stability is further confirmed by

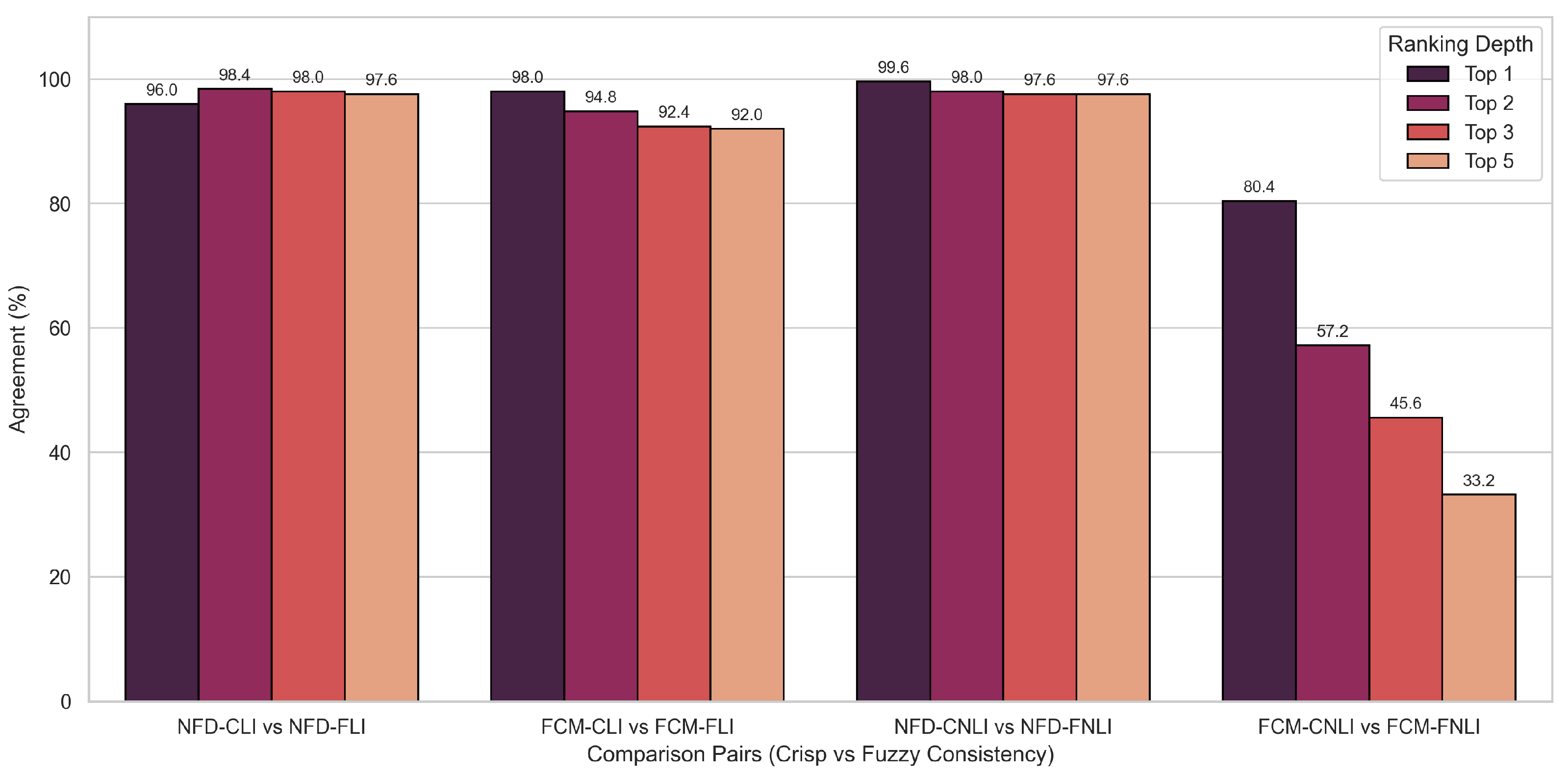

Figure 7, which illustrates the consistency between crisp and fuzzy variants; the agreement between NFDCLI and NFDFLI is exceptionally high, remaining above 97% even for the top 5 positions. This demonstrates that the FCM correction acts as a subtle refinement mechanism, adjusting rankings based on interdependencies without disrupting the core logic of the foundational method.

Figure 5.

Grouped bar chart summarizing the ranking agreement between key method pairs in their standard (crisp) forms. The bars represent the percentage of cases where the methods identified the exact same set of alternatives for the Top 1, Top 2, Top 3, and Top 5 positions. Note the high stability of the NFD method (left) versus the significant impact of non-linearity on the FCM method (second from left).

Figure 5.

Grouped bar chart summarizing the ranking agreement between key method pairs in their standard (crisp) forms. The bars represent the percentage of cases where the methods identified the exact same set of alternatives for the Top 1, Top 2, Top 3, and Top 5 positions. Note the high stability of the NFD method (left) versus the significant impact of non-linearity on the FCM method (second from left).

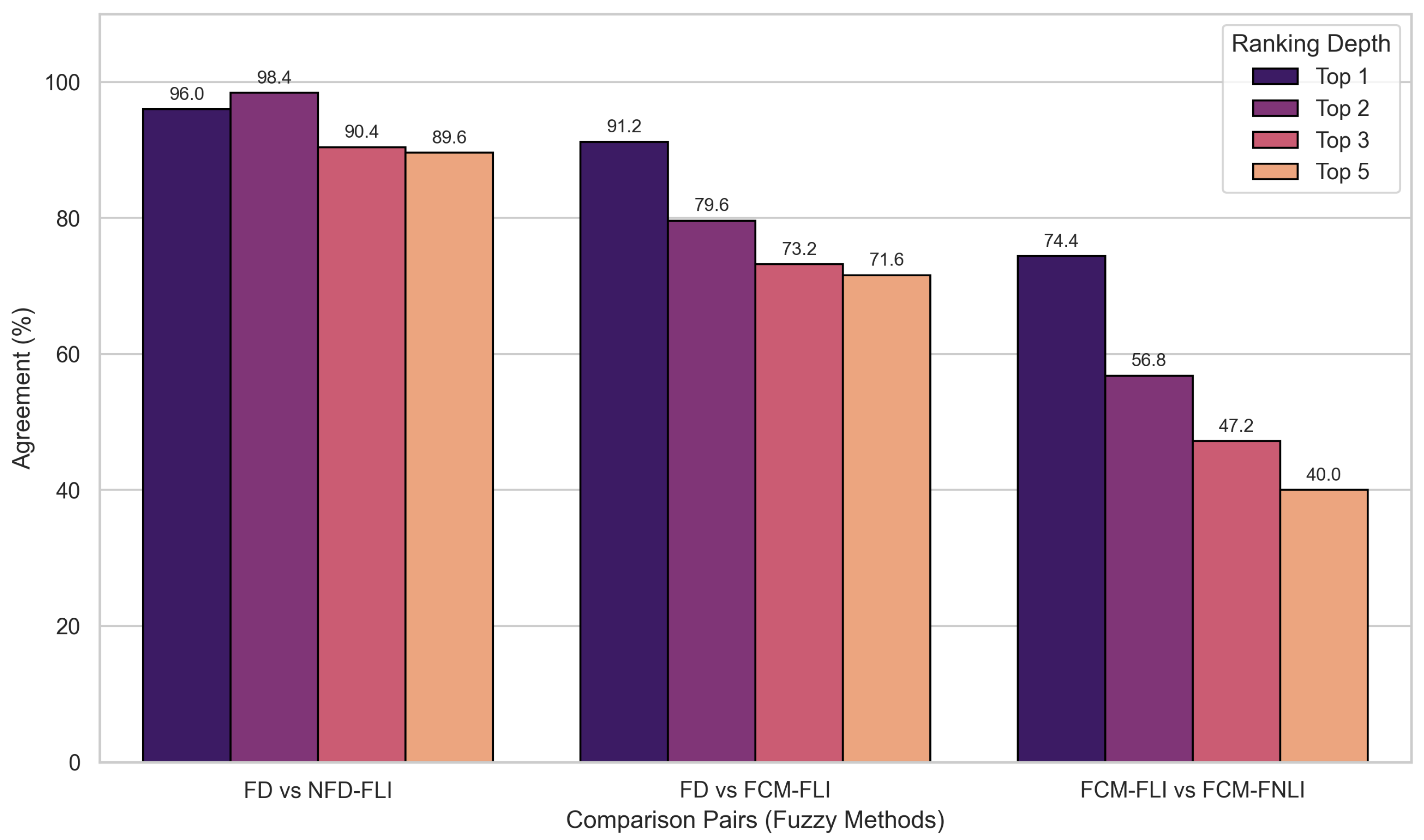

FCM Methods (Variability): On the other hand, the FCM methods show greater variability.

Figure 5 highlights the significant impact of non-linearity: the agreement between the linear FCMCLI and the non-linear FCMCNLI drops dramatically from 66.4% (Top 1) to just 16.4% (Top 5). Similarly,

Figure 6 shows that within the fuzzy context, the non-linear variant (FCMFNLI) diverges significantly from the linear one (FCMFLI), with agreement falling to 40.0% for the top 5. By comparing the high stability of fuzzy variants in

Figure 7 (e.g., FCMCLI vs FCMFLI at 92.0%) with the sharp drops caused by non-linearity, it can be deduced that non-linearity introduces significantly greater ranking variability than the effects of fuzziness.

Figure 6.

Grouped bar chart summarizing the ranking agreement for Fuzzy method variants. This comparison highlights how the fuzzy implementations of the proposed methods relate to the baseline FD and to each other. Consistent with the crisp results, the non-linear fuzzy variant (FCM-FNLI) shows significant divergence from its linear counterpart (FCM-FLI).

Figure 6.

Grouped bar chart summarizing the ranking agreement for Fuzzy method variants. This comparison highlights how the fuzzy implementations of the proposed methods relate to the baseline FD and to each other. Consistent with the crisp results, the non-linear fuzzy variant (FCM-FNLI) shows significant divergence from its linear counterpart (FCM-FLI).

Figure 7.

Analysis of consistency between Crisp and Fuzzy variants. This chart measures the percentage of identical rankings when identifying the Top 1 to Top 5 alternatives. The consistently high bars for the NFD comparisons (e.g., NFD-CLI vs NFD-FLI) confirm that fuzzification does not drastically alter the method’s output. In contrast, the non-linear FCM variants show lower consistency between crisp and fuzzy forms at deeper ranking levels.

Figure 7.

Analysis of consistency between Crisp and Fuzzy variants. This chart measures the percentage of identical rankings when identifying the Top 1 to Top 5 alternatives. The consistently high bars for the NFD comparisons (e.g., NFD-CLI vs NFD-FLI) confirm that fuzzification does not drastically alter the method’s output. In contrast, the non-linear FCM variants show lower consistency between crisp and fuzzy forms at deeper ranking levels.

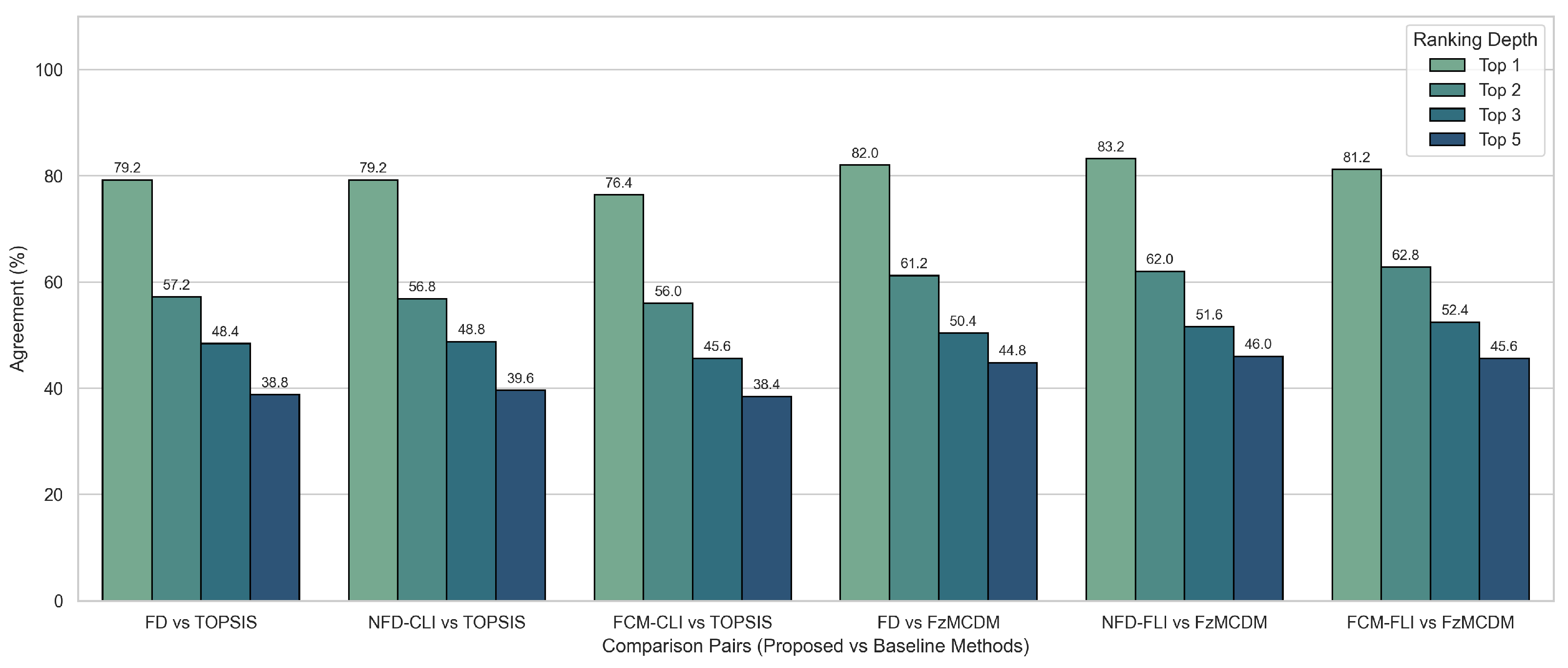

Baseline Comparisons: The comparisons with established methods are detailed in

Figure 5 and

Figure 8. The agreement between TOPSIS and FzTOPSIS, as illustrated in the third cluster of

Figure 5, is 82.8% for the top 1 position but falls to 50.4% for the top 5. In contrast, the agreement between TOPSIS and FzMCDM is higher, maintaining 59.2% for the top 5. Furthermore,

Figure 8 demonstrates that the proposed cognitive methods (NFD and FCM_DM) generally maintain competitive alignment with these baselines, often showing slightly higher agreement with FzMCDM (e.g., NFDFLI vs FzMCDM at ~46% for Top 5) than with TOPSIS (NFDCLI vs TOPSIS at ~39% for Top 5), supporting the validity of the proposed framework in fuzzy decision environments.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the proposed cognitive methods (FD, NFD, FCM) against established baselines (TOPSIS and FzMCDM). The chart displays the percentage of identical rankings for the Top 1 to Top 5 positions. The proposed methods generally show stronger alignment with FzMCDM than with the crisp TOPSIS method, particularly at deeper ranking levels.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the proposed cognitive methods (FD, NFD, FCM) against established baselines (TOPSIS and FzMCDM). The chart displays the percentage of identical rankings for the Top 1 to Top 5 positions. The proposed methods generally show stronger alignment with FzMCDM than with the crisp TOPSIS method, particularly at deeper ranking levels.

4. Discussion

In this work, two novel methodologies for MCDM have been proposed and analyzed. The first, NFD, constitutes an enhancement of the FD approach, developed specifically to improve the method’s ability to address dependence and feedback among criteria. The second, FCM_DM, utilizes the architecture of FCMs to offer a flexible ranking mechanism. Crucially, the proposed framework is intentionally flexible, capable of modeling both linear relationships (via the traditional FCM inference mechanism) and nonlinear relationships (using the non-traditional influence function), with the outcome driven primarily by the expert-defined fuzzy connection matrix (). Additionally, to facilitate detailed comparisons, a new metric based on Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was introduced, which assigns different significance to alternatives according to their rank positions.

4.1. Interpretation of Key Findings

The experimental analysis, which utilized a random example generator to create 250 diverse test cases, provided distinct insights into the behavior of the proposed methods. It is important to clarify that this “randomness” is not an inherent property of the model but a simulation strategy used to generate diverse topologies, ensuring the comparative results are robust and not dependent on a single problem structure.

The results indicate a clear distinction between the two approaches. The NFD method demonstrated high stability, maintaining strong correlations () with the foundational FD method across all variants. This confirms that the FCM-based correction acts as a subtle refinement mechanism; it adjusts rankings to account for criteria interdependencies without disrupting the core logic of the original method. Conversely, the FCM_DM method exhibited greater ranking variability () compared to traditional methods. This divergence suggests that incorporating dynamic feedback loops and non-linear influences leads to more diverse rankings, particularly for top alternatives. This variability is not a defect but rather evidence of the method’s capacity to capture complex systemic behaviors that static methods, such as TOPSIS or FzMCDM, may overlook.

4.2. Limitations

While the proposed methodologies offer significant advancements, specific technical limitations must be explicitly acknowledged:

Computational Complexity: The iterative nature of FCM-based methods introduces greater computational complexity compared to single-pass algorithms like TOPSIS. While modern computing capabilities make this a minor barrier for most standard applications, the added insight from modeling dynamic feedback comes at the cost of increased processing time.

Reliance on Expert Weights: As with many MCDM approaches, the framework’s effectiveness hinges on the quality of expert-defined weights. While our NFD method serves as a corrective lens to partially compensate for initial misjudgments by evaluating the holistic influence of criteria, the final output remains dependent on the accuracy of the initial expert inputs.

Validity of Causal Structure: A more fundamental challenge is the validity of the causal relationships defined in the matrix. The framework requires experts to define the entire network of influence, creating a risk where the expert’s “mental map” may not accurately reflect the real-world system’s dynamics. Although Fuzzy Logic aids in capturing expert intuition, validating these perceived causal links objectively remains a difficult task.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This study introduced a comprehensive cognitive framework for MCDM, specifically applied to the complex problem of industrial robot selection. By integrating FCMs into the decision-making process, we provided two distinct paths: an evolutionary enhancement of the FD method and a novel, fully dynamic approach.

5.1. Contributions and Implications

The primary contribution of this work is the development of a framework that moves beyond the assumption of criteria independence—a significant limitation in standard MCDM approaches. We successfully demonstrated that while NFD offers a stable method for refining expert judgments, the FCM_DM method provides a distinctive capability to generate rankings based on the simulation of causal relationships.

From a managerial perspective, the proposed approach transforms the decision-making process from a static selection task into an exploratory strategic exercise. FCM_DM serves as a powerful strategic tool that enables dynamic “what-if” scenario analysis. For instance, a decision-maker can simulate a scenario where ‘operating cost’ exerts a stronger negative impact on ‘profitability’ and instantly observe how the ranking of robot alternatives shifts. This adaptability allows for a more nuanced understanding of how specific criteria interrelations influence the final decision.

5.2. Future Directions

The limitations identified in this study point toward significant avenues for future research. To address the “expert-reliance” problem, future work should focus on:

- 1.

Hybrid Learning Approaches: Integrating machine learning algorithms to “learn” or refine FCM weights from historical data, reducing the subjectivity of the initial inputs.

- 2.

Causal Discovery: Developing methods to objectively discover or validate the causal structure of the connection matrix. Creating an approach that combines expert intuition with evidence from data-driven causal discovery would provide a more verifiable and robust foundation for cognitive decision-making.