1. Introduction

Rail transportation, serving as a critical infrastructure and economic artery for the nation, demands utmost safety and reliability. Track fasteners, as key connecting components that secure rails to sleepers, directly undertake vital functions including maintaining gauge, transmitting loads, and absorbing vibrations [

1]. Due to the high-frequency forces exerted by trains and the impact of complex environmental loads, fastener defects occur frequently [

2].

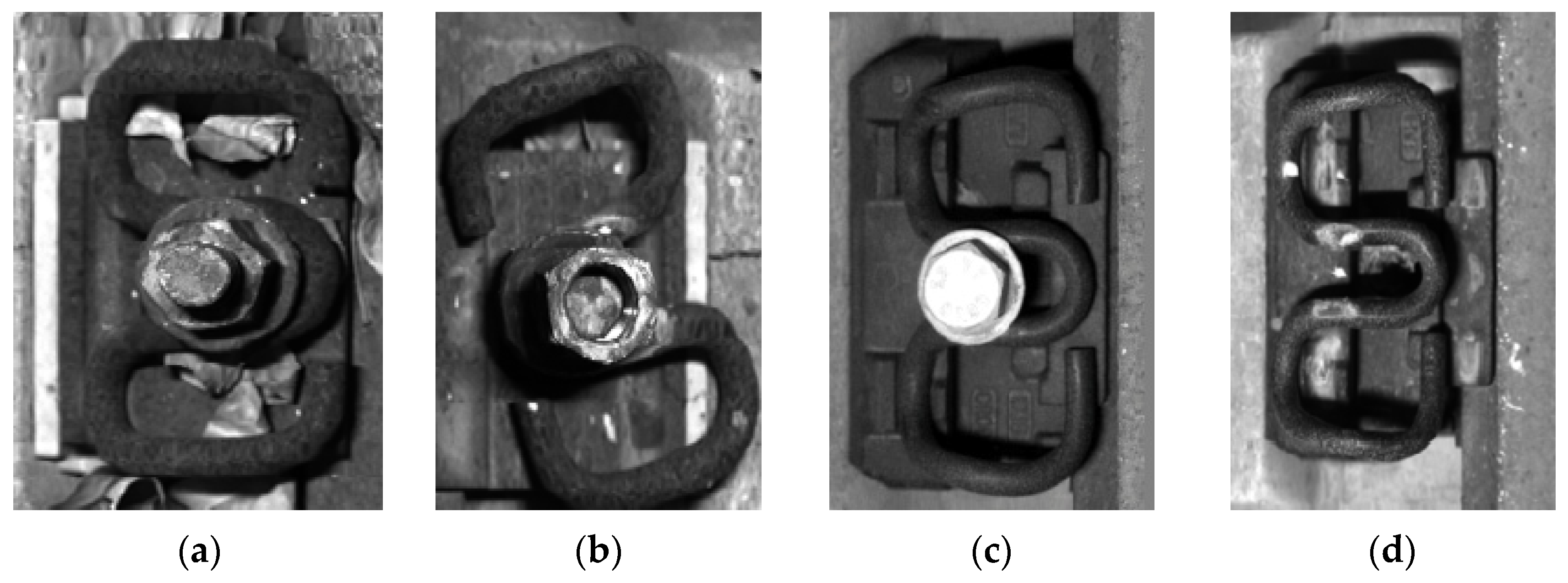

Figure 1 displays typical fastener defects identified during field investigations and provides a detailed classification of common fastener defect types. Once defects such as missing, broken, deformed, or severely corroded fasteners occur, they significantly compromise the integrity and stability of the track structure, potentially leading to rail displacement, gauge widening, and even catastrophic derailments. Therefore, conducting efficient and accurate periodic inspections of track fastener conditions constitutes a crucial link in ensuring railway operational safety.

Traditional fastener inspection primarily relies on manual patrols. This method is not only inefficient and labor-intensive but also struggles to guarantee accuracy and consistency in detection results due to the influence of inspectors’ subjective experience, physical condition, and environmental factors. It has become inadequate to meet the development demands of modern high-density, high-speed railway networks. To address these challenges, non-destructive testing (NDT) technologies have been developed for detecting defects in railway components, including methods utilizing acoustic and vibration signals, as well as machine vision technologies [

3].

Early non-destructive testing methodologies were predominantly based on acoustic and vibration signal analysis [

4]. For example, Zhang et al. [

5] employed acoustic emission monitoring data to perform probabilistic assessment of railway damages, while Chellaswamy et al. [

6] implemented a dynamic differential algorithm combined with vibration signals acquired from accelerometers mounted on bogies and axle boxes to identify track defects. Although these approaches demonstrate considerable efficacy in detecting certain macroscopic damages, they exhibit substantial limitations in identifying “latent” failures—such as fastener loosening and minor misalignments that generate only minimal vibrational and acoustic signatures—thus failing to satisfy the rigorous requirements of modern inspection standards.

In recent years, with the rapid advancement of computer vision technology, machine vision-based inspection methods have emerged as a research focus due to their non-contact nature, high efficiency, and precision. The methodologies in this field can be broadly categorized into two evolutionary stages: traditional image processing-based approaches and deep learning-based techniques.

The first stage encompasses inspection methodologies grounded in traditional image processing techniques. These approaches fundamentally rely on handcrafted feature extractors designed by researchers. Ma et al. [

7] introduced a mechanism utilizing curve projection and template matching to achieve real-time detection of missing fasteners. Inspired by few-shot learning, Liu et al. [

8] devised a novel visual inspection system to localize fastener regions. Furthermore, Gibert et al. [

9] proposed a multi-task learning framework that leveraged Histogram of Oriented Gradients features (HOG) combined with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier, thereby enhancing classification accuracy for damaged and missing fasteners. Wang et al. [

10] comprehensively employed background subtraction, an improved Canny operator, Hough transform, alongside Local Binary Patterns and HOG features, with final classification performed by an SVM, demonstrating notable real-time performance and accuracy. Despite these methods having advanced automation to some extent, their performance is heavily dependent on the quality of handcrafted features. In practical scenarios characterized by varying illumination conditions, complex backgrounds, and diverse fastener types, these approaches exhibit insufficient generalization capability and poor robustness. Moreover, the intricate preprocessing and feature extraction pipelines inherent to these methods impose constraints on further enhancing detection efficiency.

The second phase is characterized by the adoption of deep learning-based detection methodologies. The emergence of deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), has enabled algorithms to autonomously learn hierarchical feature representations directly from data, thereby eliminating the dependency on manually engineered features. This paradigm shift has led to a qualitative leap in detection accuracy and robustness. Predominant object detection algorithms within this domain can be categorized into two-stage models and single-stage models.

The two-stage models, represented by the Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (R-CNN) series such as Fast Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (Fast R-CNN) [

11] and Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (Faster R-CNN) [

12], first generate region proposals and then perform classification and regression on each proposed region. This architecture generally achieves superior detection accuracy. Wei et al. [

13] applied Faster R-CNN to fastener detection, validating its exceptional classification performance. However, the multi-step detection pipeline inherent in these models results in high computational complexity and slower detection speeds, making it challenging to meet the demands of real-time online inspection in railway applications.

In pursuit of real-time performance, researchers have shifted their focus to single-stage detection models, with the You Only Look Once (YOLO) series gaining significant prominence due to their remarkable balance between speed and accuracy. Substantial improvements and applications have been developed around the YOLO architecture. Qi et al. [

14] designed an MYOLOv3-Tiny network based on YOLOv3, incorporating depthwise separable convolutions and reconstructing the backbone network, which significantly enhanced detection speed while maintaining accuracy, making it more suitable for embedded deployment. As the YOLO algorithm has evolved, enhancement efforts have continued to deepen. Guo et al. [

15] optimized the YOLOv4 framework to propose a cost-effective real-time detection solution for railway track components. Meanwhile, Fu et al. [

16] employed the lightweight MobileNet to replace the original backbone network of YOLOv4, effectively capturing subtle features of fasteners while reducing model parameters and computational load, thereby further accelerating the detection process.

In recent years, YOLOv5 and its subsequent variants have emerged as predominant platforms for research. To enhance the discrimination capability for miniature fasteners against complex backgrounds, attention mechanisms and more efficient feature fusion networks have been introduced. Li et al. [

17] embedded a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) into the neck of YOLOv5s to strengthen the extraction of critical features while suppressing irrelevant information, concurrently incorporating a weighted Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network to achieve superior multi-scale feature fusion. The work by Wang et al. [

18] demonstrates a more systematic approach: they integrated the Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN) attention mechanism into YOLOv5’s backbone, employed Ghost Shuffle Convolution (GSConv) modules in the neck network to reduce complexity, and incorporated BiFPN to enhance feature fusion. Ultimately, they improved detection accuracy and model robustness through a lightweight decoupled head structure, with their proposed YOLOv5 with CBAM, GSConv, BiFPN and Decoupled head (YOLOv5-CGBD) model surpassing the original across multiple evaluation metrics.

Furthermore, several studies have explored alternative technical pathways. Liu et al. [

19] enhanced the Faster R-CNN framework by employing K-means clustering to automatically determine anchor box positions, thereby improving detection performance for imbalanced fastener samples. In an innovative approach, Zhan et al. [

20] leveraged prior information to verify fastener locations on three-dimensional ballastless track images, subsequently detecting defects through their designed RailNet model, introducing a novel dimension to inspection methodology. Cha et al. [

21] successfully applied Faster R-CNN to multi-class damage detection in bridges and building clusters, demonstrating the broad applicability of deep learning in infrastructure visual inspection. Roy et al. [

22] integrated Densely Connected Convolutional Networks (DenseNet) and Swin Transformer prediction heads into YOLOv5, proposing the DenseNet and Swin Transformer Prediction Head YOLOv5 (DenseSPH-YOLOv5) model for effective multi-scale road damage detection—a methodology whose conceptual framework holds significant referential value for fastener inspection.

However, current research and applications continue to face a prominent bottleneck: most existing approaches treat “fastener detection” as a single, homogeneous task, failing to adequately account for its inherent complexity and heterogeneity in real-world scenarios. This limitation manifests concretely at the following two levels:

Firstly, there exists a diversity in fastener types and heterogeneity in their defect manifestations. After decades of development in China’s railway system, multiple fastener types are in operation—ranging from traditional Type I and Type II elastic strips to Type III, WJ-7, and WJ-8 fasteners designed for high-speed and heavy-haul lines. Significant differences in structure, material, and fastening mechanisms among these variants lead to distinct defect patterns. A generic detection model optimized for Type II elastic strip fasteners often experiences severe performance degradation when confronted with structurally distinct WJ-8 fasteners. Current approaches for multi-type fastener detection typically involve training a single, all-encompassing model to recognize all types. Such models are compelled to learn generic features across all fastener types, thereby struggling to capture type-specific, subtle defect characteristics. Consequently, in complex mixed-type railway lines, the overall detection accuracy—particularly the recognition rate for specific defects on particular fastener types—remains unsatisfactory.

Secondly, the challenge lies in the co-occurrence of multiple defect types and the complexities of multi-label classification. A single fastener may simultaneously exhibit various defects; for instance, an elastic strip might present both “fracture” and “corrosion,” while a bolt could be “loose” and accompanied by “strip displacement.” This necessitates a detection system capable of multi-label classification. However, employing a single classifier to process all fastener types and structures leads to an excessively complex and high-dimensional feature space that the model must learn. The classifier is required to disentangle both “type-specific” characteristics and multiple “defect” features from highly diverse fastener images—an exceptionally difficult task that often results in insufficient model learning, ultimately causing misclassification and missed detections.

In summary, the core scientific challenge in the field of automated railway fastener inspection can be formulated as follows: determining how to construct an intelligent detection system capable of effectively accommodating the diversity of fastener types while achieving accurate and robust multi-label recognition of various defects.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this study proposes a Type-Guided Expert Model-based Fastener Detection and Diagnosis framework (TGEM-FDD) based on YOLOv8. The core concept follows a “type-identification-first, defect-diagnosis-second” paradigm, with specific contributions outlined as follows:

- (1)

Framework Design: We construct a novel two-stage detection framework that decouples the complex task into localization/type identification and specialized defect diagnosis, effectively overcoming the limitations of single-model approaches.

- (2)

Model Enhancement: We introduce three key enhancements to the first-stage detector—the Deepstar Block, Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast with Attention (SPPF-Attention), and Dynamic Sample (DySample)—significantly boosting its feature representation, multi-scale fusion, and localization precision.

- (3)

Expert Model Pool: We innovatively adopt an expert model pool, where a dedicated multi-label classifier is trained for each fastener type, enabling specialized and accurate defect diagnosis.

- (4)

Dataset: We design and construct a multi-label fastener image dataset, providing crucial data support for fine-grained component recognition in complex industrial scenarios.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Construction

The image dataset of railway fasteners was acquired from an industrial railway line located in Hengshui City, Hebei Province, China, during November 2024. The collected fastener models are the most representative Type II clip fastener and WJ-8 fastener, which are the mainstream types in China’s conventional-speed railways and high-speed railways, respectively. Their samples can effectively reflect the typical conditions encountered in actual operation. To ensure dataset diversity and robustness, the collection procedure systematically incorporated real-world variations in illumination conditions, background complexity, and shooting distances.

Image acquisition was performed using a line-scan camera mounted on a track inspection vehicle, yielding 160 original images capturing two fastener types under various damage conditions. Each image covered a 12 m track segment with an original resolution of 512 × 9000 pixels.

Given the excessive aspect ratio of the original images—which proves suboptimal for effective model detection—we performed initial preprocessing through cropping and padding operations. This standardized each image to contain four fastener sets. After processing and quality screening, the final curated dataset comprised 1200 validated images containing 4800 individual fastener samples.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the constructed dataset, providing comprehensive statistics on sample distribution across fastener types and detailed occurrence frequencies of six common defect categories.

Figure 1 presents representative examples of typical defects observed across different fastener types.

2.2. Overall Architecture

The overall architecture of the proposed Type-Guided Expert Model-based Two-Stage Fastener Multi-Label Detection method (TGEM-FDD) is illustrated in

Figure 2. The fundamental motivation for this decoupled design stems from the inherent challenges posed by the heterogeneous nature of diverse fastener types and the multi-label characteristic of their defects, which collectively compel a single model to learn an excessively complex and conflicting feature representation. Therefore, our core concept follows a “type identification first, defect diagnosis second” paradigm, which decomposes the complex multi-type, multi-label detection task into two relatively independent and focused sub-tasks. This design effectively overcomes the performance limitations of single-model approaches in handling such heterogeneous scenarios.

Stage I: Fastener Localization and Type Identification. This stage takes raw track images as the input, with the primary objective of accurately localizing all fasteners within the image and identifying the specific type of each fastener. In this study, an enhanced high-performance detector (YOLOv8s with Deepstar, SPPF-attention, and DySample (YOLOv8s-DSD)) is constructed based on the YOLOv8 architecture, incorporating modules such as Deepstar Block, Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast with Attention (SPPF-Attention), and Dynamic Sample (DySample). The output of this stage consists of the bounding box coordinates and the type classification label for each fastener.

Stage II: Multi-Label Defect Diagnosis. This stage executes the type-guided mechanism for defect analysis. Initially, based on the fastener type identified in the first stage, the system dynamically retrieves the corresponding specialized classification model from a pre-constructed expert model pool. Subsequently, the cropped fastener region images from the first stage are fed into this expert model for refined analysis. Each expert model comprises a targeted multi-label classifier, generating independent confidence scores for potential multiple defects present in the specific fastener type.

Finally, a result fusion module integrates the localization and type information from the first phase with the defect diagnosis results from the second phase, yielding comprehensive detection results with complete informational integrity.

2.3. YOLOv8s-DSD Model

As the foundational and prerequisite component of the proposed two-stage detection framework, the performance of the first stage directly determines the upper limit of the entire system. The core objective of this stage is to accurately localize all fasteners within the image and correctly identify their specific types. The output of this stage provides a reliable control signal for the type-guided mechanism in the second phase.

The YOLOv8 [

23] architecture is categorized into five variants—n, s, m, l, and x—based on application scenarios, with sequentially increasing network depth and width, correspondingly enhancing detection accuracy at the cost of computational complexity. Among these, YOLOv8s achieves an optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency: its precision and mean average precision (mAP) significantly surpass those of YOLOv8n, while its model size, computational load, and parameter count remain substantially lower than those of YOLOv8m. Given the stringent requirements for real-time performance and deployment on resource-constrained edge devices in railway fastener detection tasks, this study selects YOLOv8s as the baseline model for enhancement.

To improve the model’s sensitivity to small fastener targets and subtle inter-type differences, several modifications are implemented: the Cross Stage Partial network with 2 convolutions (C2f) module in the backbone network is replaced with the Deepstar Block to enhance feature selection and semantic extraction capabilities; an attention mechanism is integrated into the Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF) module in the Neck section; and the original interpolation-based upsampling method is substituted with the DySample dynamic upsampling operator. The resulting model, termed YOLOv8s with Deepstar, SPPF-attention, and DySample (YOLOv8s-DSD), is structured as illustrated in

Figure 3.

- (1)

Deepstar Block Feature Extraction Module

In the YOLOv8 algorithm, the C2f module is responsible for feature extraction [

24]. It consists of convolutional layers, split operations, and bottleneck modules, incorporating multiple gradient branches and cross-stage feature connections to capture more effective information. However, the extensive convolutional layers and gradient branches require more computational operations and higher memory demands, leading to inefficient feature extraction. To address this limitation, a novel feature extraction module named Deepstar Block is constructed, integrating multi-branch modeling, residual connections, star operations [

25], and regularization strategies. Its structure is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The Deepstar Block module adopts a dual-branch design, utilizing depthwise separable convolutions in place of standard convolutional operations to reduce computational load, with all being convolutions. In the first branch, initial features are formed through a convolutional layer, followed by a residual structure containing two parallel convolutional layers (without BatchNorm operations), after which a star operation is applied. Subsequently, two sequential convolutional layers are employed, followed by a Dropout operation. The second branch begins with a convolutional layer for channel compression, followed by two bottleneck layers to extract deep semantic features. The outputs of both branches are then concatenated, and finally, a convolutional layer is used to control the number of output channels.

In the first branch, the star operation facilitates information interaction between two feature maps of identical shape. Combined with residual connections, it ensures information integrity while enhancing gradient stability. The Dropout operation helps to suppress overfitting and improves generalization performance. The star operation, defined as elementwise matrix multiplication, non-linearly combines different channels of the input features by performing per-element multiplication, creating a large number of interaction terms and significantly expanding the dimensionality of the feature space. Through the star operation and residual fusion, this branch finely adjusts feature distributions, strengthens the expression of key information, and enhances feature diversity, thereby improving the model’s sensitivity to small target features and its ability to model complex semantic relationships.

The second branch, composed of convolutional and Bottleneck layers, is primarily responsible for extracting high-level semantic information and constructing stable feature representations. It reinforces the depth of information flow, enabling the extraction of richer features while maintaining gradient stability.

The Deepstar Block achieves a structurally stable and efficient design: one branch emphasizes dynamic regulation and detail refinement, exhibiting sensitivity to subtle features of small targets; the other focuses on global modeling and deep feature extraction, with stable gradients and strong representational capacity. By employing depthwise separable convolutions, the module reduces computational overheads while maintaining structural depth. Thus, the Deepstar Block module realizes an organic integration of structural stability, rich expressiveness, and computational efficiency, accomplishing a feature representation strategy that balances stability and sensitivity while complementing semantic information with local details.

- (2)

Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast with Attention (SPPF-attention)

To address the issue of weak focus on key regions in fastener detection, this study improves upon the SPPF module [

26]. The SPPF module is a spatial pyramid pooling structure designed for feature extraction and fusion. However, when processing fastener features, it struggles to effectively concentrate on critical attention information, resulting in limited discriminative capability for fastener types. To overcome this limitation, an attention mechanism is introduced into the SPPF module, leading to the proposed SPPF-attention module [

27].

The structure of SPPF-attention is illustrated in

Figure 5. The module embeds a spatial attention mechanism before the final

convolutional layer, generating a spatial attention weight map through operations on the spatial dimensions of the feature map to highlight key spatial regions. Specifically, the input feature map first undergoes global average pooling and global max pooling along the channel dimension, producing two feature descriptors of size

. These two descriptors are then concatenated along the channel dimension and passed through a

convolutional layer for feature fusion and dimensionality reduction. A Sigmoid activation function is subsequently applied to generate spatial attention weights ranging from 0 to 1. Finally, these weights are multiplied elementwise with the original feature map, thereby enhancing the feature response in important regions while suppressing irrelevant areas. Through this attention mechanism, the module enables the network to automatically focus on critical regions of fasteners, extracting more discriminative features and effectively improving the recognition performance for defect characteristics.

- (3)

DySample Upsampler

The original YOLOv8 employs nearest-neighbor interpolation for upsampling, which operates by simply replicating the values of neighboring pixels to fill newly generated pixel locations. This approach lacks smoothness and tends to lose fine details and edge information, potentially leading to positional deviations of feature points. In this study, DySample [

28] is adopted as the upsampler. DySample is a lightweight and efficient upsampling algorithm that utilizes a content-aware dynamic upsampling method, adaptively adjusting sampling positions based on local image characteristics to more accurately reconstruct the locations and details of feature points.

Compared to kernel-based dynamic upsamplers (e.g., Content-Aware ReAssembly of Features (CARAFE) [

29], Feature Agnostic Dynamic Upsampling (FADE) [

30], and Spatially Adaptive Pooling (SAPA) [

31]), which incur significant computational overheads due to time-consuming dynamic convolutions and additional sub-networks for generating dynamic kernels, DySample circumvents dynamic convolution by formulating upsampling from a point-sampling perspective. This results in fewer parameters, reduced floating-point operations, lower GPU memory usage, and decreased latency, making it more suitable for edge deployment.

The design principle of DySample is illustrated in

Figure 6. In

Figure 6a, the input feature

is resampled using a sampling set

generated by a sampling point generator.

Figure 6b depicts the structure of the sampling point generator, which consists of two components: the generated offset

and the original sampling grid

. The offset generation mechanism combines linear transformation with pixel shuffling. Taking the static factor sampling method shown in the upper part of

Figure 6b as an example, given an upsampling factor

and a feature map of size

, the feature map is passed through a linear layer with input and output channels of c and

, respectively, to generate an offset

of size

. This offset is then transformed into a

representation via pixel-level shuffling, where 2 denotes the

and

coordinates. Finally, an upsampled feature map of size

is generated.

By introducing a neighboring pixel sampling mechanism, DySample effectively enhances sample diversity, thereby mitigating class imbalance issues and suppressing false predictions.

2.4. YOLOv8-Cls-Based Multi-Label Classification Network

This stage serves as the implementation of the “type-guided” mechanism, aiming to perform detailed analysis on the fastener region images localized and cropped in the first stage, while simultaneously outputting multiple potential defect labels for each fastener. To achieve this objective, we developed an “expert model pool” with multi-label classification capability by modifying the YOLOv8 pre-trained classification model through several key adaptations.

The YOLOv8-Cls model was selected as the foundational backbone for each expert model. Pre-trained on large-scale datasets such as ImageNet, this model possesses strong general feature extraction capabilities, providing an excellent starting point for subsequent defect feature learning.

Since the standard YOLOv8-Cls model is designed for single-label classification (where each image belongs to only one category), while fastener defects (such as concurrent “Fractured spring clip” and “Displaced spring clip”) often coexist, the following adaptations were implemented:

- (1)

Detection Head Reconstruction

The original single-label classification head at the network’s output layer (utilizing Softmax activation function) has been replaced with a multi-label classification head. The reconstructed head employs a Sigmoid activation function as its output layer, with channel dimensionality matching the number of defect categories. Specifically, for a task containing K defect types, the model outputs a K-dimensional vector , where each element represents the independent probability of the fastener containing the kth defect type. By setting an appropriate threshold (typically 0.5), the coexistence of multiple defects can be effectively determined.

- (2)

Loss Function Adaptation

To accommodate the multi-label classification task, the original cross-entropy loss has been replaced with binary cross-entropy loss. This loss function decomposes the multi-label classification task into K independent binary classification problems, computing the loss between predicted and ground-truth values for each label separately, and subsequently averaging these losses. The formulation is as follows:

Here, is the true value of the kth defect label (1 indicates presence, 0 indicates absence), and is the Sigmoid probability predicted by the model for the kth defect. This loss function can effectively optimize both positive labels (i.e., existing defects) and negative labels (i.e., non-existing defects) simultaneously.

- (3)

Specialized Training

We independently train a modified YOLOv8-Cls (Multi-label) model for each primary fastener type (e.g., Type II Clip Fastener, WJ-8). Each model is trained exclusively using images of the corresponding fastener type along with their multi-label defect data. This “divide and conquer” strategy enables each expert model to deeply focus on learning the unique defect patterns and characteristics specific to its assigned fastener structure, thereby transforming it into a specialized “diagnostic expert” for that particular fastener type.

- (4)

Type-Guided Inference

During the inference phase, the fastener type (class_type) identified in the first stage serves as a control signal to dynamically retrieve the corresponding pre-trained model from the “expert model pool.” The selected expert model then analyzes the cropped fastener region images from the first stage and outputs a multi-label defect vector. Finally, a result fusion module integrates the localization, type, and defect information to generate comprehensive detection results.

3. Experiments and Results Analysis

3.1. Evaluation Metrics

This study employs standard evaluation metrics from the field of object detection. The core detection performance indicators include: mean average precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5 (mAP@0.5), average mAP over IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 (mAP@0.5:0.95), Precision (P), and Recall (R). Additionally, the number of parameters and Giga Floating Point Operations (GFLOPs) are selected to assess model complexity, ensuring practical deployment feasibility while maintaining performance.

To comprehensively evaluate the end-to-end performance of the two-stage framework, this paper defines “Task mAP” as a comprehensive evaluation metric. This metric requires the detection results to simultaneously satisfy three conditions:

- (1)

Accurate Localization: IoU between the detected bounding box and the ground truth box ≥ 0.5;

- (2)

Correct Type Identification: Accurate classification of the fastener type;

- (3)

Correct Defect Diagnosis: Accurate prediction of all defect labels (confidence threshold of 0.5).

The calculation method is as follows: the average precision (AP) is computed separately for each “type-defect” combination, and then the AP values across all combinations are averaged to obtain the final Task mAP@0.5.

This metric is intentionally stringent. A prediction is considered correct only if all defect labels are exactly matched; partial success (e.g., identifying only two out of three true defects) is treated as a failure under this criterion. This design aims to drive the system toward achieving comprehensive and faultless detection, which aligns with the high-reliability requirements of practical railway inspection. To complement this strict overall measure, the Macro-F1 score is also reported to provide a more nuanced assessment of the defect recognition module’s performance across all categories.

This metric rigorously reflects the system’s comprehensive capability in localization, type identification, and multi-label defect diagnosis, aligning closely with practical application requirements.

3.2. Experimental Environment and Implementation Details

The experiments were conducted in a software environment based on Windows 10, CUDA 12.1, and PyTorch 2.4.1. The hardware configuration consisted of an Intel Core i7-12700K CPU and an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU.

For the first-stage model training, the core hyperparameters were set as follows: a total number of training epochs of 200, an early stopping patience of 50 epochs to prevent overfitting, a batch size of 16, an initial learning rate of 0.01, and a weight decay coefficient of 0.0005.

In the second stage, each expert model was trained on its corresponding fastener-type subset using a strategy similar to the first stage: 100 training epochs, an early stopping patience of 50 epochs, a batch size of 16, an initial learning rate of 0.01, and a weight decay coefficient of 0.0005. Through independent training processes, specialized classification models were obtained for each fastener type.

Figure 7 illustrates the mAP progression curves during training for both YOLOv8s-DSD and the baseline model.

3.3. Module Effectiveness Analysis

- (1)

Localization Effectiveness Experiment of Deepstar Block

To determine the optimal placement of the Deepstar Block, we systematically replaced the C2f modules in different network components while keeping all other conditions identical. Specifically, the Deepstar Block was substituted into the backbone network, the neck network, and both the backbone and neck networks simultaneously. The experimental results are summarized in

Table 2.

As shown in

Table 2, the Deepstar Block exhibits varying effects when deployed in different network components. Its integration into the neck module yields limited performance improvements while significantly increasing both parameters and computational costs. Therefore, we decided against replacing the C2f modules in the neck with the Deepstar Block. Compared to deployments in the neck or the combined backbone-neck configuration, replacing only the backbone’s C2f modules achieves substantial accuracy improvements with only marginal increases in parameters and computation. This outcome aligns with the module’s design purpose: the dual-branch structure of the Deepstar Block is particularly effective in the backbone for collaboratively modeling both the global semantic features (e.g., overall fastener shape and type prototype) and fine-grained local details (e.g., edges and micro-defects), thereby providing a richer and more discriminative feature foundation for subsequent detection tasks. Consequently, applying the Deepstar Block exclusively to the backbone network delivers the optimal accuracy enhancement.

- (2)

Experimental Validation of SPPF-Attention Module

This investigation presents a systematic optimization of YOLOv8’s feature extraction architecture, with particular emphasis on augmenting the multi-scale feature fusion capabilities of the SPPF module. To rigorously evaluate the efficacy of the proposed SPPF-Attention mechanism in dense railway fastener detection applications, we conducted comprehensive comparative analyses against prevailing enhancement methodologies (

Table 3). The integration of an efficient attention mechanism with hierarchical pooling operations yielded a composite SPPF-Attention structure that achieved a 1.9% enhancement in detection precision while maintaining parametric efficiency.

The implemented methodology employs feature selection mechanisms to optimize fusion weights across scale-specific representations, substantially improving small-scale fastener discriminability with minimal parametric overheads. Under challenging operational scenarios characterized by complex track environments and high fastener density, the proposed architecture demonstrates significant improvements in localization accuracy while effectively suppressing both false positive and false negative rates. Comparative assessment reveals that while dilated convolution-based Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) modules achieve receptive field expansion, they exhibit susceptibility to feature confusion among morphologically similar fastener instances. The lightweight Simplified Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SimSPPF) variant, though computationally efficient, demonstrates inadequate characterization of critical fastener minutiae. The Spatial Pyramid Pooling Cross Stage Partial Channel (SPPCSPC) architecture introduces substantial computational redundancy through multi-branch pooling operations, resulting in suboptimal operational efficiency.

Our framework innovatively incorporates structural prior learning through attention reweighting, enabling selective emphasis on mechanically salient fastener attributes over superficial textural patterns. This design is driven by the task objective of fastener localization and type identification. During training, the network is intrinsically guided to allocate attention weights to features most relevant to this task. Although direct visualization of attention maps is not presented in this study, the significant and consistent improvement in detection accuracy (e.g., +1.9% mAP@0.5 as shown in

Table 3) provides compelling empirical evidence. It indicates that the attention mechanism effectively learns to suppress irrelevant and variable background noise (e.g., randomly shaped ballast) and to enhance stable structural features of fasteners, rather than being misled by high-contrast but semantically irrelevant textures. This architectural refinement significantly enhances inter-class discriminability among heterogeneous fastener typologies. Empirical validation confirms that the optimized feature extraction backbone maintains real-time inference capabilities while exhibiting superior robustness and generalization performance in complex railway operational environments.

3.4. Ablation Studies

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed DeepstarBlock, SPPF-attention module, and DySample upsampler, we conducted comprehensive ablation experiments using YOLOv8s as the baseline model. The evaluation metrics included precision, recall, mAP@50, model size, floating point operations (GFLOPs), and parameter count. Eight different module combinations were systematically tested, with the experimental results on the test set summarized in

Table 4.

The experiments first evaluated the individual contributions of each improved module through ablation studies. Compared to the baseline model (YOLOv8s), the standalone introduction of the Deepstar Block demonstrated significant lightweight advantages while improving detection accuracy: mAP@0.5 increased from 95.7% to 97.5% (+1.8%), mAP@0.5:0.95 improved from 77.2% to 78.7% (+1.5%), while GFLOPs decreased from 28.9 to 26.1 and parameters reduced from 11.2 M to 10.5 M. This module enhances feature representation capability while reducing computational resource consumption, achieving the improvement goal of being “both stronger and smaller.”

The independent incorporation of the SPPF module yielded the most substantial enhancement in comprehensive detection capability, achieving 97.6% mAP@0.5 (+1.9%) and 79.1% mAP@0.5:0.95 (+1.9%), though it introduced significant computational overheads, with GFLOPs increasing to 33.9 and parameters growing to 12.5 M. This validates the effectiveness of multi-scale feature fusion for fastener detection tasks, while acknowledging the inevitable computational cost increase.

The standalone implementation of the DySample upsampling operator achieved a stable improvement in mAP@0.5 from 95.7% to 96.2% (+0.5%) without increasing parameter count, verifying the effectiveness of its dynamic high-frequency detail preservation strategy.

Module combination experiments further revealed synergistic effects among components. This synergy can be attributed to the complementary roles of each module: the Deepstar Block serves as a powerful backbone, providing a rich and stable foundation of features; the SPPF-Attention module then operates on this enhanced foundation, performing more precise multi-scale feature fusion by adaptively focusing on salient regions across scales. Consequently, the Deepstar Block and SPPF-Attention combination achieved 98.1% mAP@0.5 and 78.9% mAP@0.5:0.95 with 31.3 GFLOPs and 11.8 M parameters, striking an optimal balance between computational efficiency and detection accuracy. Similarly, the integration of DySample with the Deepstar Block ensures that the high-quality features learned by the backbone are preserved and refined during upsampling, mitigating detail loss. This explains how the Deepstar Block with DySample combination achieved 97.8% mAP@0.5 with only 27.0 GFLOPs, constituting a “high-performance, low-complexity” solution with substantial potential for edge deployment.

The final model integrating all three modules achieved optimal performance: 98.5% mAP@0.5 (+2.8%) and 79.5% mAP@0.5:0.95 (+2.3%), with 11.8 M parameters and 31.9 GFLOPs. Compared to the baseline, it achieved significant detection accuracy improvement while maintaining an essentially equivalent parameter count, fully demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed enhancement scheme.

These ablation studies demonstrate that the proposed improvement strategy effectively optimizes a lightweight baseline model (YOLOv8s) into a high-performance, efficiency-conscious detector (YOLOv8s-DSD). This not only validates the effectiveness of individual modules but also highlights the substantial application value of our solution in resource-constrained edge computing scenarios.

3.5. Performance Comparison of Different Detection Models

To objectively evaluate the performance advantages of the proposed method, comparative experiments were conducted between the improved model and current mainstream object detection models. The models selected for comparison include Faster R-CNN, SSD, YOLOv5s, YOLOv7s, and YOLOv8s. Detailed comparative results are presented in

Table 5.

As shown in

Table 5, the proposed YOLOv8s-DSD model demonstrates significant advantages in detection accuracy. Specifically, the model achieves an mAP@0.5 of 98.5%, surpassing the baseline models Faster R-CNN, SSD, YOLOv5s, YOLOv7-Tiny, and YOLOv8s by 22.9, 21.6, 10.2, 10.0, and 2.8 percentage points, respectively. In terms of precision, it reaches 95.0%, representing improvements of 22.7, 21.3, 10.5, 10.1, and 2.9 percentage points over the comparative models. The recall metric stands at 97.1%, with enhancement ranging from 4.2 to 27.0 percentage points compared to the other models.

Regarding model complexity, the proposed model maintains excellent performance while demonstrating notable efficiency advantages. Compared to the two-stage detector Faster R-CNN, the parameter count is only 8.6%, and the computational load is less than one-tenth. Even when compared to lightweight models in the same series, our model exhibits a favorable balance: relative to the YOLOv8s baseline, the parameter count increases by only 5.4% and computational load by 10.4%, while the key metric mAP@0.5:0.95 improves by 2.3 percentage points. This achieves significant performance gains at a relatively small computational cost.

In summary, the experimental results indicate that the proposed improvement scheme effectively enhances the accuracy of fastener detection while maintaining well-controlled model complexity. It achieves an optimal balance between precision and efficiency, fulfilling the dual requirements of detection accuracy and real-time performance in practical railway maintenance scenarios.

3.6. Comparative Experiment of the Overall Two-Stage Framework

To validate the comprehensive advantages of the proposed “type-guided expert model” two-stage framework in addressing the multi-task detection problem for fasteners, this section systematically compares it with various advanced single-stage end-to-end detection methods. All comparative methods were trained and tested on the same multi-label fastener dataset to ensure experimental fairness.

- (1)

Configuration of Comparative Methods.

This experiment establishes the following three categories of comparative approaches:

Category 1: Single-model Unified Detection Method.

YOLOv8s (Category Combination): This approach simplifies the task into a single multi-category detection problem, where the output categories represent all possible combinations of fastener types and defects.

Category 2: Multi-task Separate Head Detection Method.

YOLOv8s (Separate Head): This method modifies the detection head structure to simultaneously output bounding boxes, fastener type categories, and multiple independent defect confidence scores.

RT-DETR-R50 (Separate Head): A Transformer-based detector built on the RT-DETR architecture, adapted for multi-task output.

Category 3: Proposed Method.

TGEM-FDD Framework: The complete Type-Guided Expert Model Framework.

- (2)

Results and Analysis

The comparative experimental results presented in

Table 6 lead to the following conclusions:

The single-model unified detection approach demonstrates the poorest performance, achieving a comprehensive task mAP of only 65.2%. This indicates that forcibly merging multi-type and multi-defect tasks into a single multi-category detection problem leads to significant performance degradation, as the model struggles to learn complex category combination relationships. The multi-task separate head method shows some improvement, with RT-DETR-R50 (separate head) reaching 76.5%, proving that the separate head design can partially alleviate multi-task learning conflicts. However, the single model still needs to simultaneously learn localization, type classification, and multi-defect recognition, exhibiting clear performance bottlenecks. The proposed TGEM-FDD framework achieves optimal performance with a comprehensive task mAP of 88.1%, significantly outperforming the previous two categories of methods, thus validating the effectiveness of the two-stage design and expert model strategy.

In terms of type recognition accuracy, the proposed method reaches 89.0%, maintaining a stable advantage compared to other approaches. For defect recognition macro-average F1-score, our method achieves 86.5%, representing a 7.2 percentage point improvement over RT-DETR-R50 (separate head). This demonstrates that the two-stage framework, through task decoupling, enables each component to focus on specific subtasks, thereby achieving more professional performance in the defect recognition phase.

Regarding parameter count, the proposed framework (13.5 M) is substantially lower than RT-DETR-R50 (19.8 M), reflecting better parameter efficiency. In inference speed, our method (121 FPS) maintains real-time performance while achieving the optimal accuracy-speed balance.

The experimental results clearly illustrate the capability differences among the three approaches in addressing complex multi-task detection problems. The single-model unified detection method performs poorly due to high task complexity; the multi-task separate head method achieves some improvement through structural optimization but remains limited by the representation capacity of a single model; the proposed two-stage framework achieves optimal performance through type-guided task decomposition and specialized diagnosis by expert models. The overall two-stage framework comparison experiment proves that the proposed TGEM-FDD framework significantly outperforms both single-model unified detection and multi-task separate head solutions in end-to-end fastener detection tasks, validating the advanced nature and practical utility of the two-stage design in complex industrial vision applications.

3.7. Visualization and Analysis of Results

To intuitively demonstrate the performance of the proposed TGEM-FDD framework in practical applications, we selected representative scenarios from the test set for visual analysis.

Figure 8 presents the detection results of our method under various complex working conditions.

Figure 8 presents a visual analysis of detection results under various working conditions. Subfigures (a) and (b) demonstrate the framework’s precise detection capability under normal lighting conditions, successfully identifying fastener types and diagnosing multiple defects. However, subfigure (c) reveals instances of missed and false detections. Preliminary analysis indicates that these errors primarily stem from severe lighting variations (such as overexposure and extreme shadows), which significantly alter the apparent characteristics of the fasteners. This suggests that although the proposed method performs robustly under standard conditions, its generalization capability and robustness against intense, non-uniform lighting require further enhancement. Subsequent work will focus on improving the model’s adaptability to such challenging environmental factors.