AI-Powered Cybersecurity Models for Training and Testing IoT Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: How can AI-powered models improve the detection of cyberattacks in diverse IoT environments compared to traditional methods?

- RQ2: What challenges, such as concept drift and feature space heterogeneity, arise when training and testing AI models across heterogeneous IoT datasets?

- Unified Benchmarking Framework: We establish a standardized preprocessing and evaluation pipeline applied consistently across five distinct, modern IoT datasets (2019–2024), mitigating the bias found in single-dataset studies.

- Cross-Domain Performance Analysis: We provide a granular analysis of AI model performance across varying IoT contexts including Industrial IoT (IIoT), Internet of Medical Things (IoMT), and general IoT highlighting specific protocol-based vulnerabilities (e.g., MQTT).

- Evaluation of Generalization Capabilities: We empirically evaluate the challenges of feature heterogeneity and concept drift, offering insights into the realistic limitations of deploying models trained on general traffic in specialized environments.

2. Related Work

2.1. The IoT Threat Landscape

2.2. AI-Driven Intrusion Detection Systems

2.3. Limitations and Research Gaps

3. Datasets and Preprocessing

3.1. Description of the Datasets

- We utilized a collection of modern IoT datasets from CIC to evaluate the robustness and cross-domain generalization of our models. We chose these specific datasets because they represent a wide spectrum of IoT environments ranging from smart homes and industrial control systems to medical devices and include recent, complex attack vectors. Using multiple heterogeneous datasets is key to our goal of verifying how well models generalize beyond their training domain. Table 1 provides a comprehensive summary of these datasets, detailing the specific domain focus, total sample count, feature dimensions, and the primary attack categories included in each dataset. ToN-IoT Dataset (2021): This dataset comes from a large and realistic network that includes both regular IoT devices and Industrial IoT (IIoT) devices. Its main strength is its diversity and complexity, making it a good test for how models handle a mixed environment. It includes attacks like DDoS, ransomware, and man-in-the-middle [10].

- Edge-IIoTset (2022): This dataset focuses on Industrial IoT. The data was collected from a network with edge devices, common in smart factories. Its strength is its focus on IIoT-specific attacks and its realistic feature set, which includes 14 types of attacks like MQTT brute force and injection attacks [11].

- IoT-2023 Dataset: To establish a performance baseline on more generalized threats, we incorporate this dataset, which represents a modern, broad-scope IoT network.

- MQTT-IDS Dataset: For protocol-specific analysis, we utilize this dataset, which is narrowly focused on the lightweight MQTT messaging protocol common in many sensor devices.

- IoMT-2024 Dataset: A critical component of our study, this recent collection is centered on the Internet of Medical Things, allowing us to test model performance in the high-stakes healthcare domain [12].

- ACI-IoT Dataset (2023): Finally, to evaluate model robustness, we leverage this specialized dataset, which contains not only standard attacks but also intentionally crafted adversarial samples designed to evade AI-based detection.

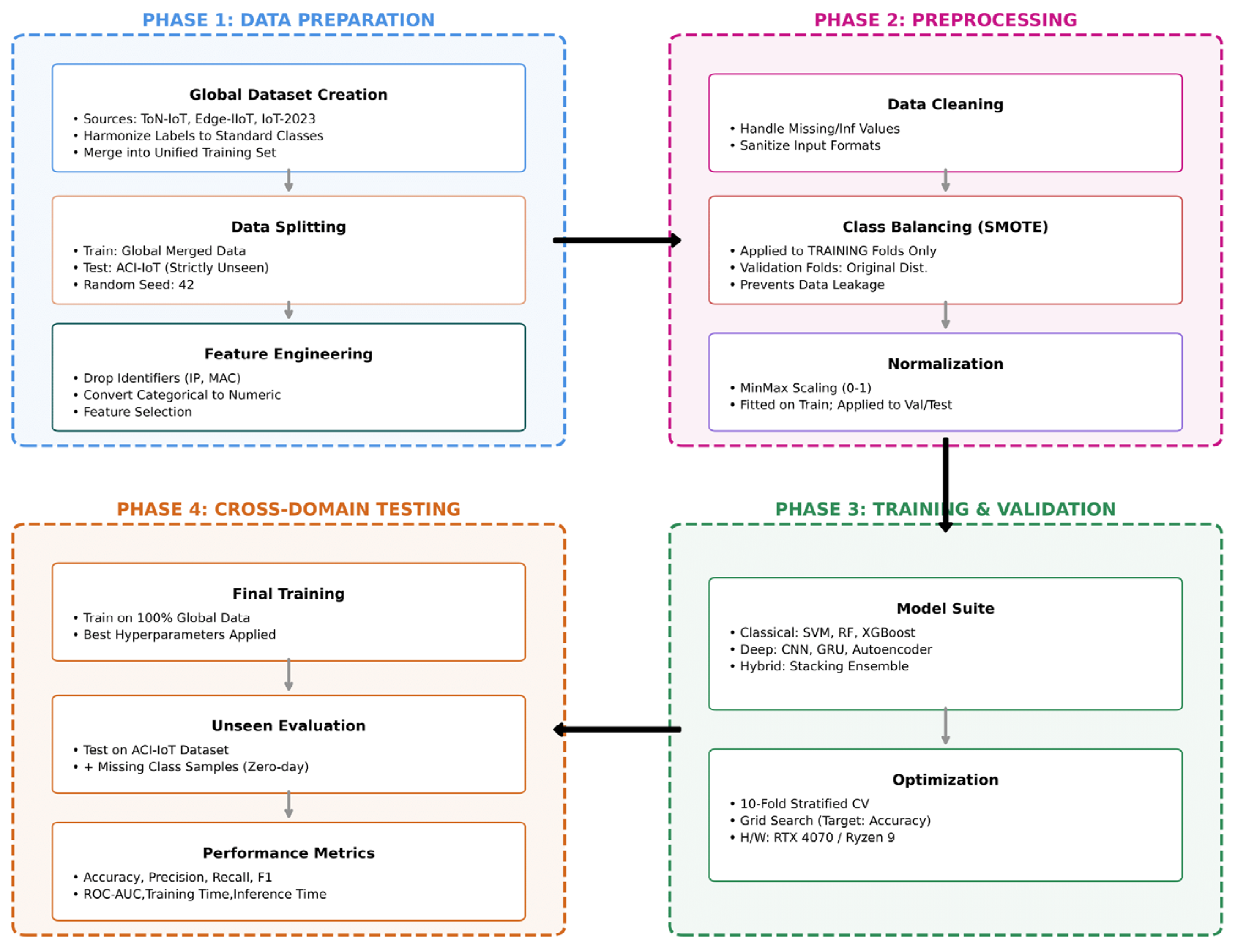

3.2. Data Preprocessing Pipeline

- Data Cleaning: The first step is to handle errors in the data. This includes finding any missing values (NaN) or infinite values. We removed rows with missing values to ensure our data was complete. We also converted all feature labels from text to numbers so the models could understand them (e.g., ‘Benign’ becomes 0, ‘DDoS’ becomes 1, etc.).

- Feature Selection: Given the heterogeneity of the datasets, where feature counts varied significantly (often exceeding 80 attributes), we first identified the intersection of common network features across all datasets to ensure consistency. To further optimize the input space, we applied Principal Component Analysis (PCA). This technique projected the high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional subspace, resulting in a final set of 30 principal components. These 30 components retained the most critical variance of the original data and served as the standardized input vectors for training all machine learning models.

- Handling Class Imbalance: In any real network, most of the traffic is normal (benign), and only a small part is an attack, which creates an “imbalanced” dataset. To fix this, we used a technique called SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique). SMOTE creates new, synthetic examples of the attack classes so that the model has more attack data to learn from.

- Data Normalization: The values of different features can be on very different scales. This difference can confuse some AI models. To solve this, we used Min-Max scaling to change all feature values to be in the same range, from 0 to 1. This helps the models train faster and more effectively.

4. Methodology

4.1. Selected Intrusion Detection Models

4.2. Experimental Design

- Phase 1: Performance Benchmarking (Internal Validation): To establish a reliable baseline, the four source datasets were harmonized mapping diverse attack labels to a standardized set of classes and merged to create a unified Global Training Dataset. We employed a 10-fold stratified cross-validation scheme. In each iteration, the dataset was partitioned into ten subsets; nine for training and one for validation.

- Phase 2: Cross-Dataset Generalization (External Testing): To evaluate the models’ resilience to domain shift and their applicability to real-world scenarios, we constructed a strictly held-out “Unseen Test Set.” This dataset comprises the ACI-IoT 2023 dataset in its entirety, augmented with hold-out samples of two specific attack classes that were present in the Global Dataset but absent in ACI-IoT. Models trained on the full Global Dataset were evaluated on this unseen set without any further retraining or fine-tuning. This step rigorously assesses the transferability of the learned features to new network contexts and heterogeneous feature spaces.

5. Results and Evaluation

- Accuracy: The overall percentage of correct predictions out of all predictions made.

- Precision: This metric indicates the reliability of the model when it flags an event as an attack. High precision implies a low rate of false alarms.

- Recall: This measures the proportion of actual attacks that the model successfully identified. High recall indicates that the model rarely misses a threat.

- F1-Score: Given that accuracy can be misleading on imbalanced datasets, the F1-Score provides a balanced view by combining Precision and Recall into a single harmonic mean.

- AUC: This measures the model’s overall ability to distinguish between classes across all thresholds. It is calculated as the integral of the ROC curve:

- Training Time: This metric measures the computational efficiency of the learning phase. It is defined as the total wall-clock time required for the model to complete its training process on the dataset.

- Inference Time: This measures the operational latency of the model. It is defined as the total time taken by the model to process and classify all samples in the testing set (referred to as Support in our classification reports). This metric is crucial for assessing suitability for real-time deployment.

5.1. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

5.1.1. Training Performance Analysis

5.1.2. Cross-Domain Generalization on ACI-IoT Dataset

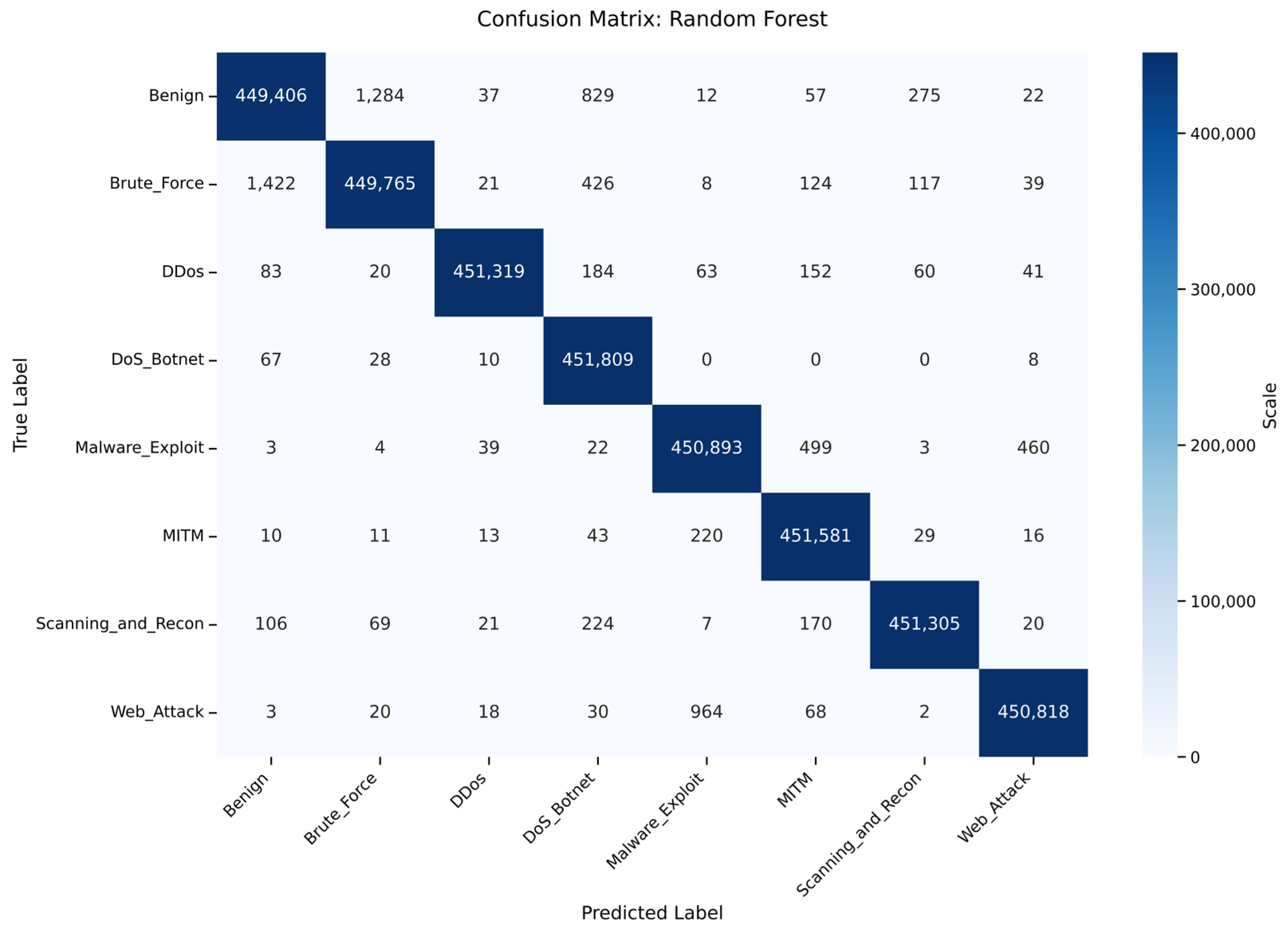

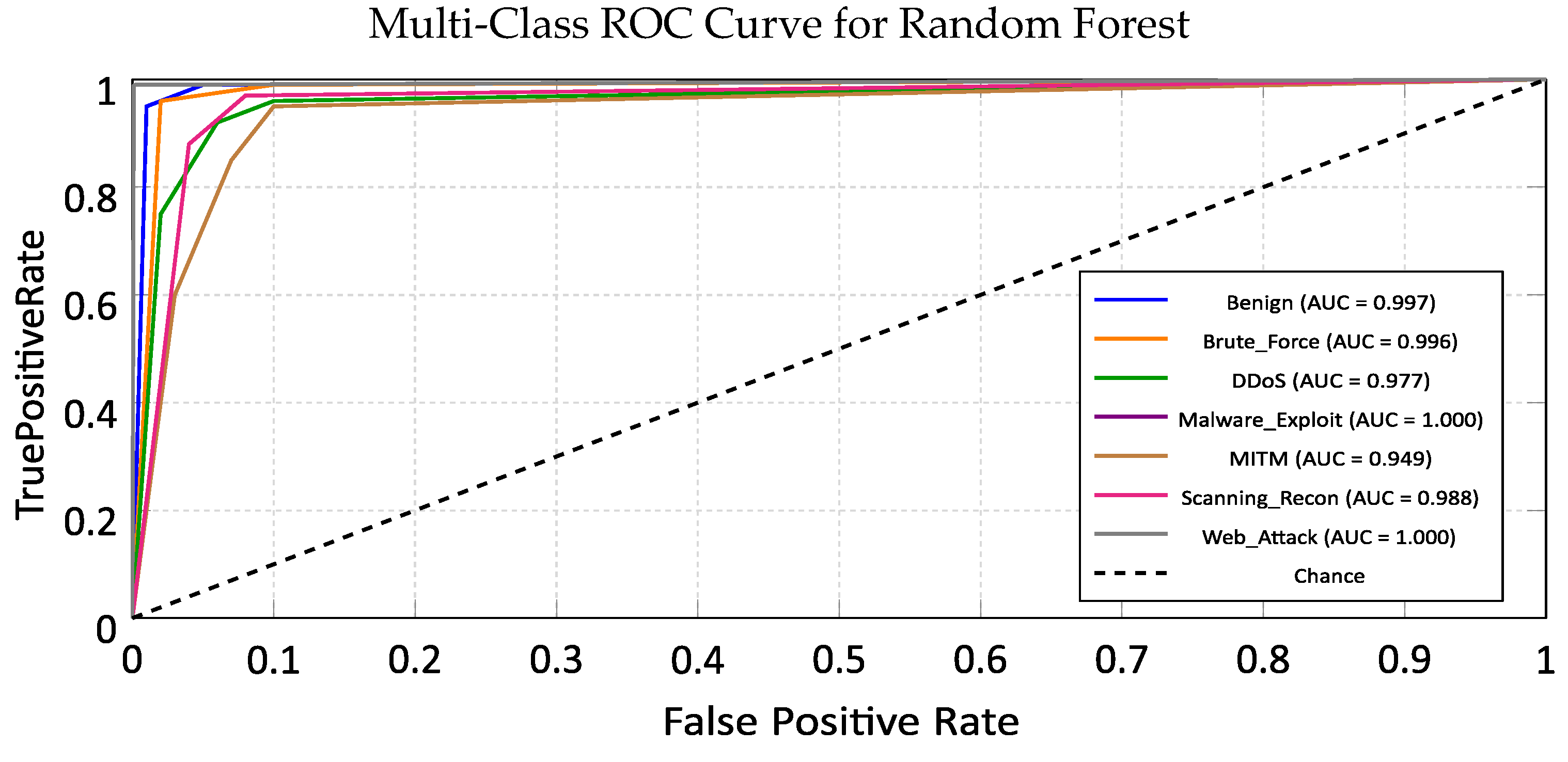

5.2. Random Forest (RF)

5.2.1. Training Performance Analysis

5.2.2. Cross-Domain Generalization on ACI-IoT Dataset

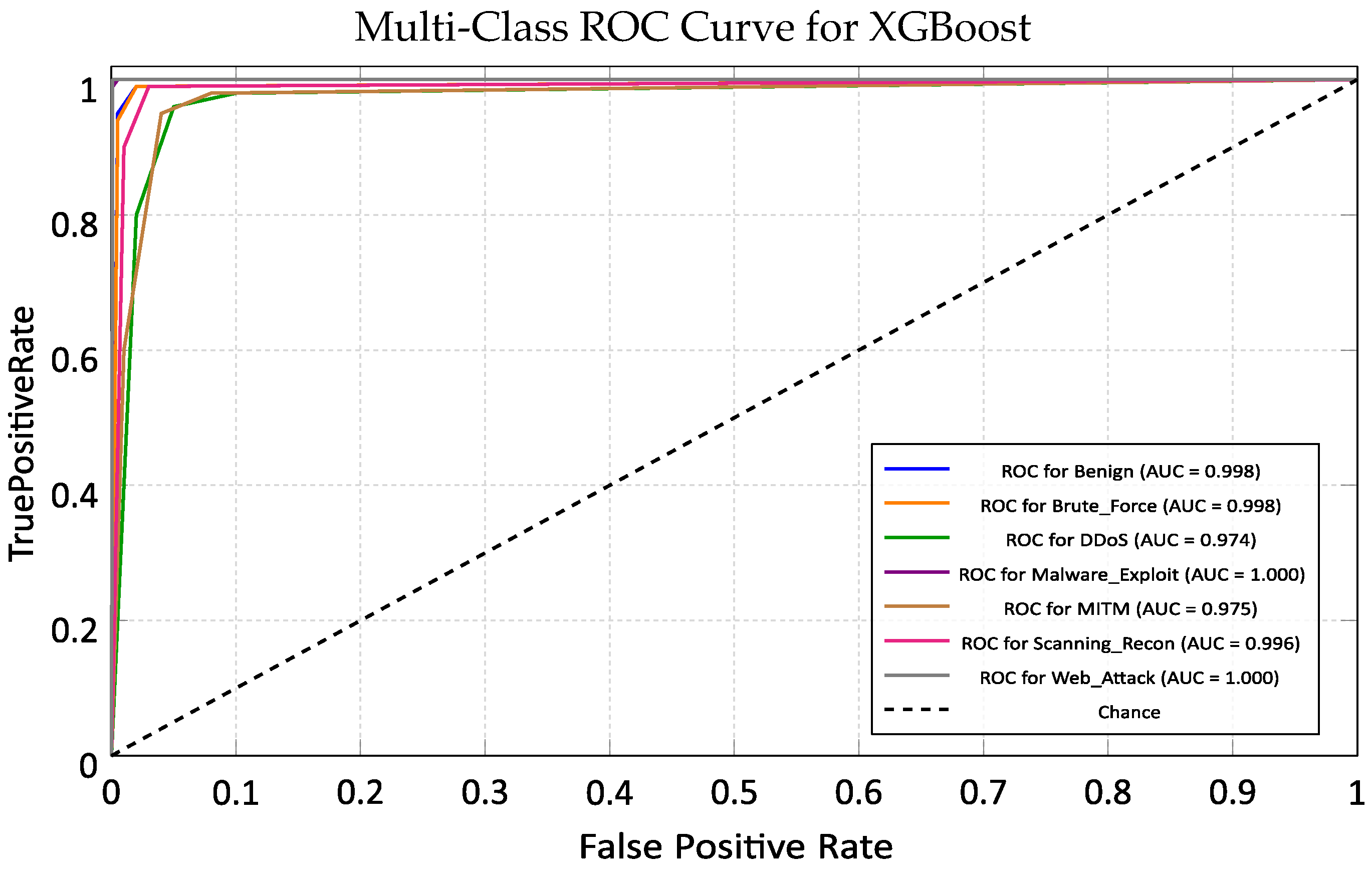

5.3. XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting)

5.3.1. Training Performance Analysis

5.3.2. Cross-Domain Generalization on ACI-IoT Dataset

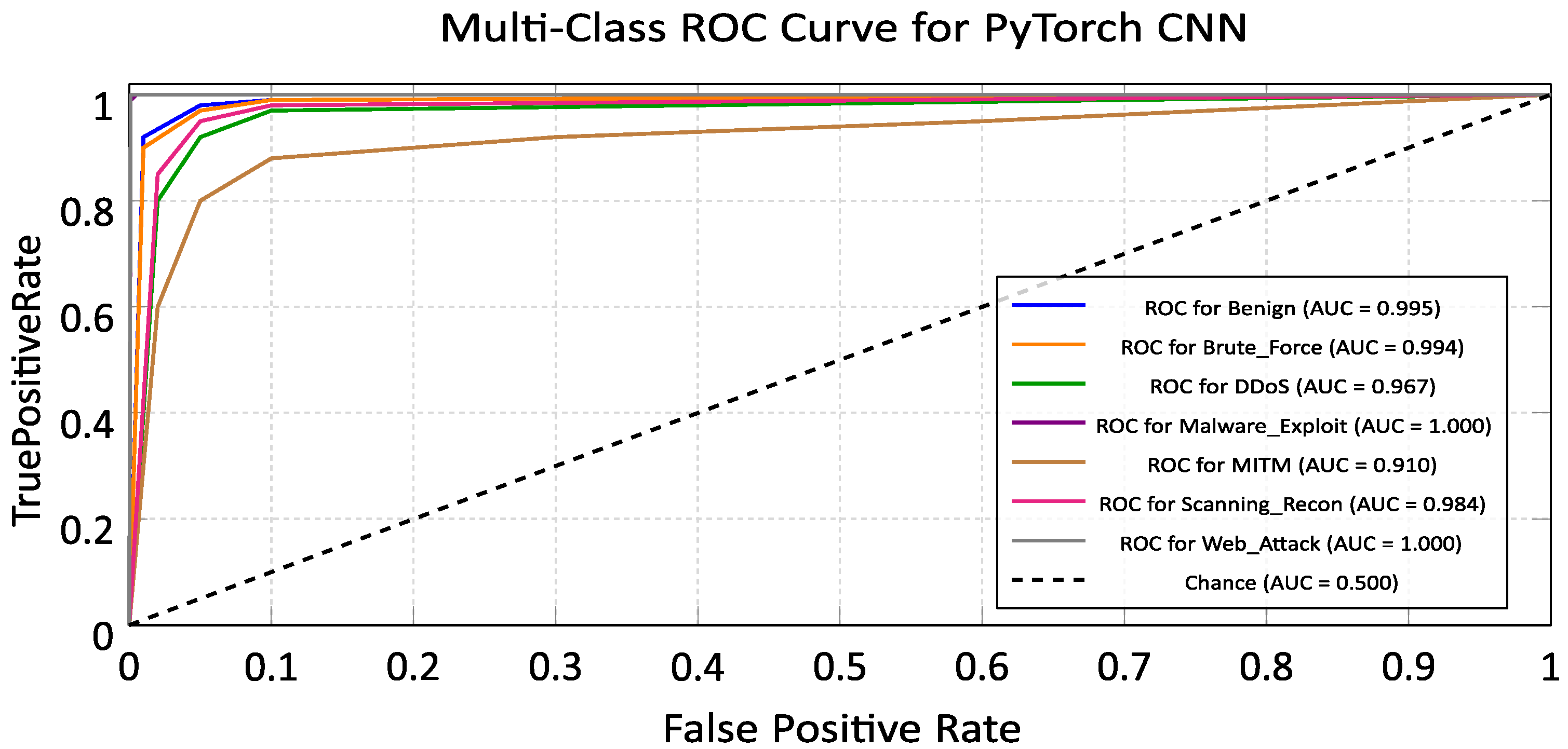

5.4. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

5.4.1. Training Performance Analysis

5.4.2. Cross-Domain Generalization on ACI-IoT Dataset

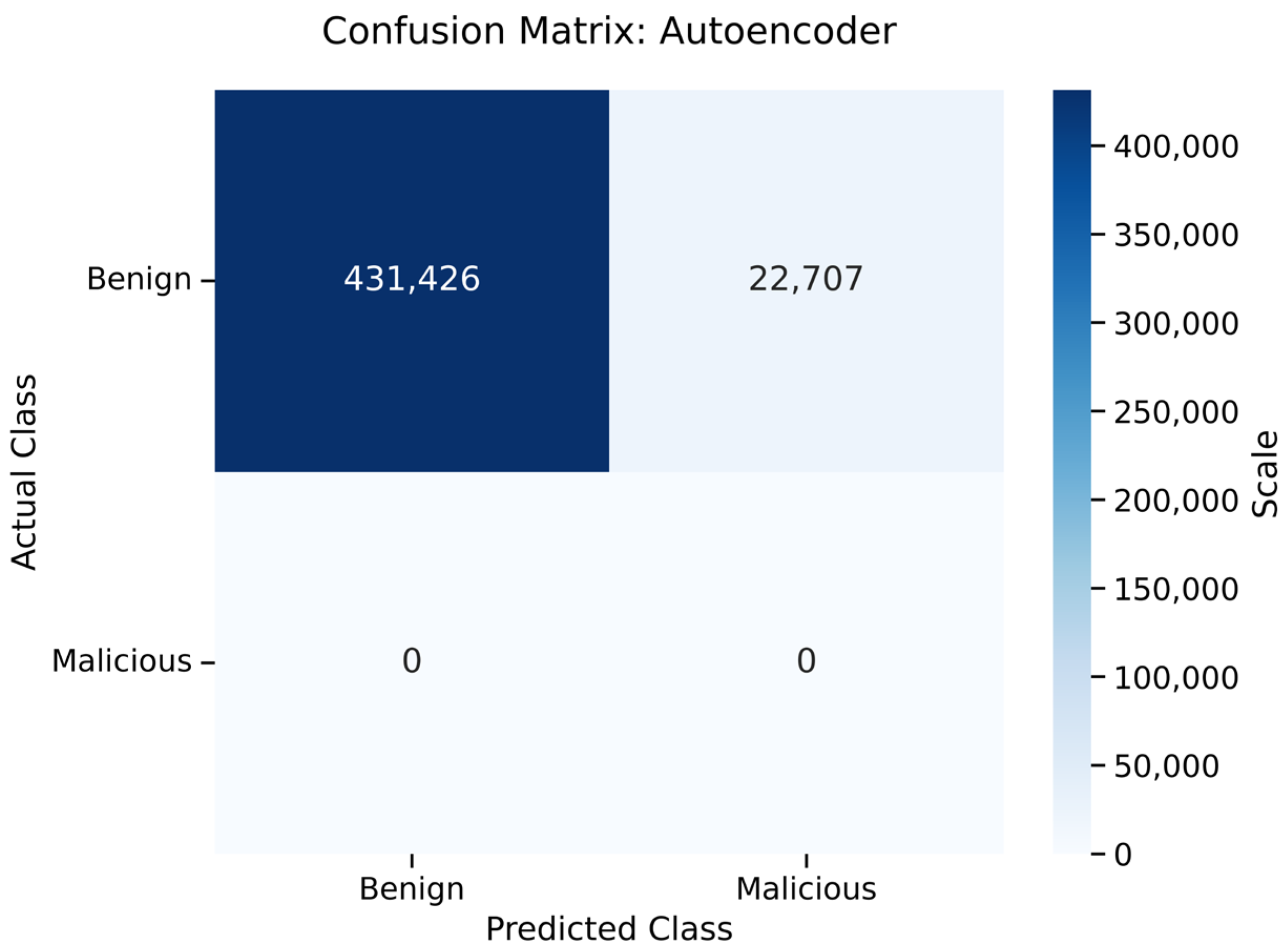

5.5. Autoencoder

5.5.1. Training Performance and Anomaly Detection

5.5.2. Generalization and Anomaly Detection Capability

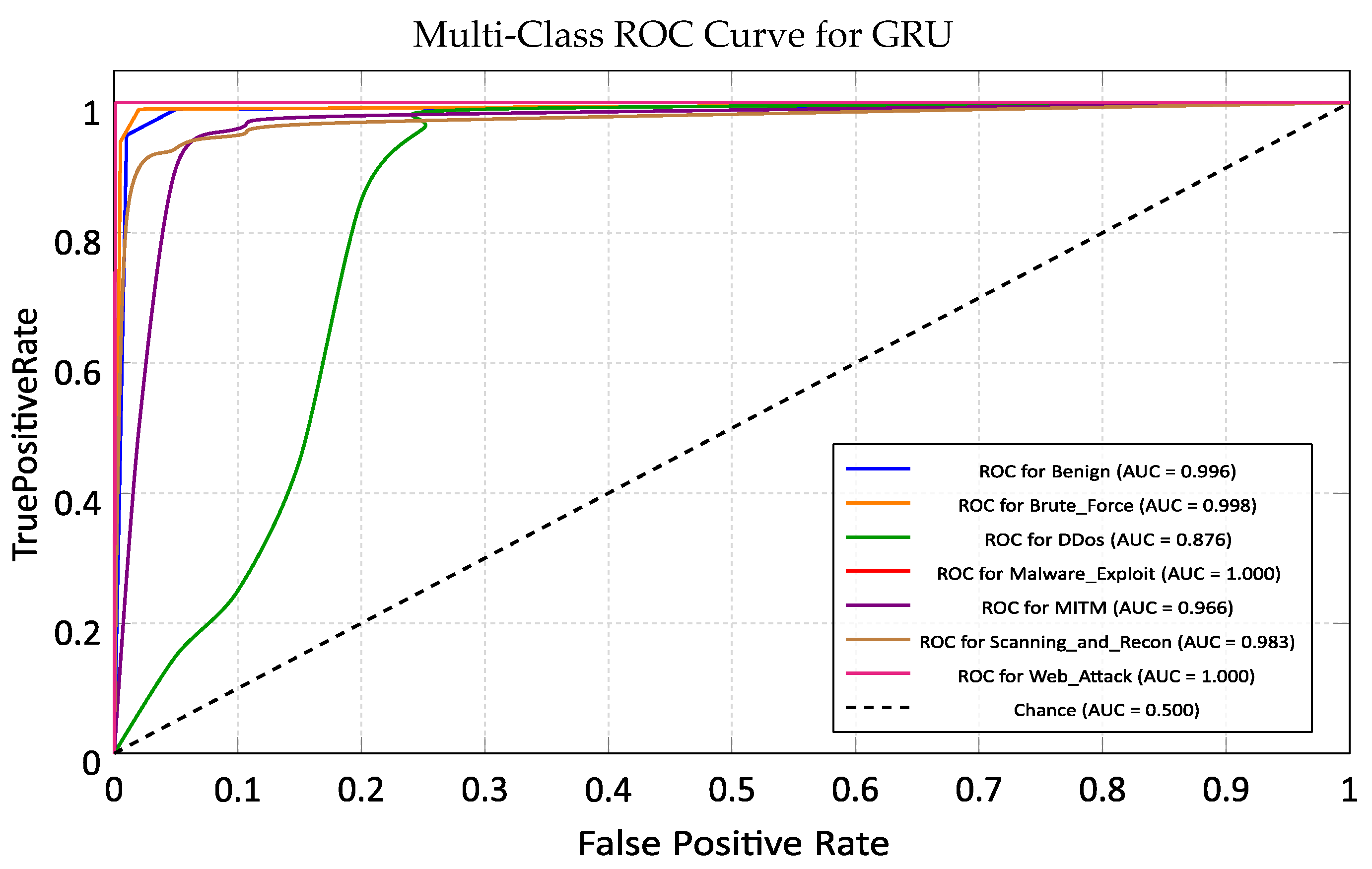

5.6. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)

5.6.1. Training Performance Analysis

5.6.2. Cross-Domain Generalization on ACI-IoT Dataset

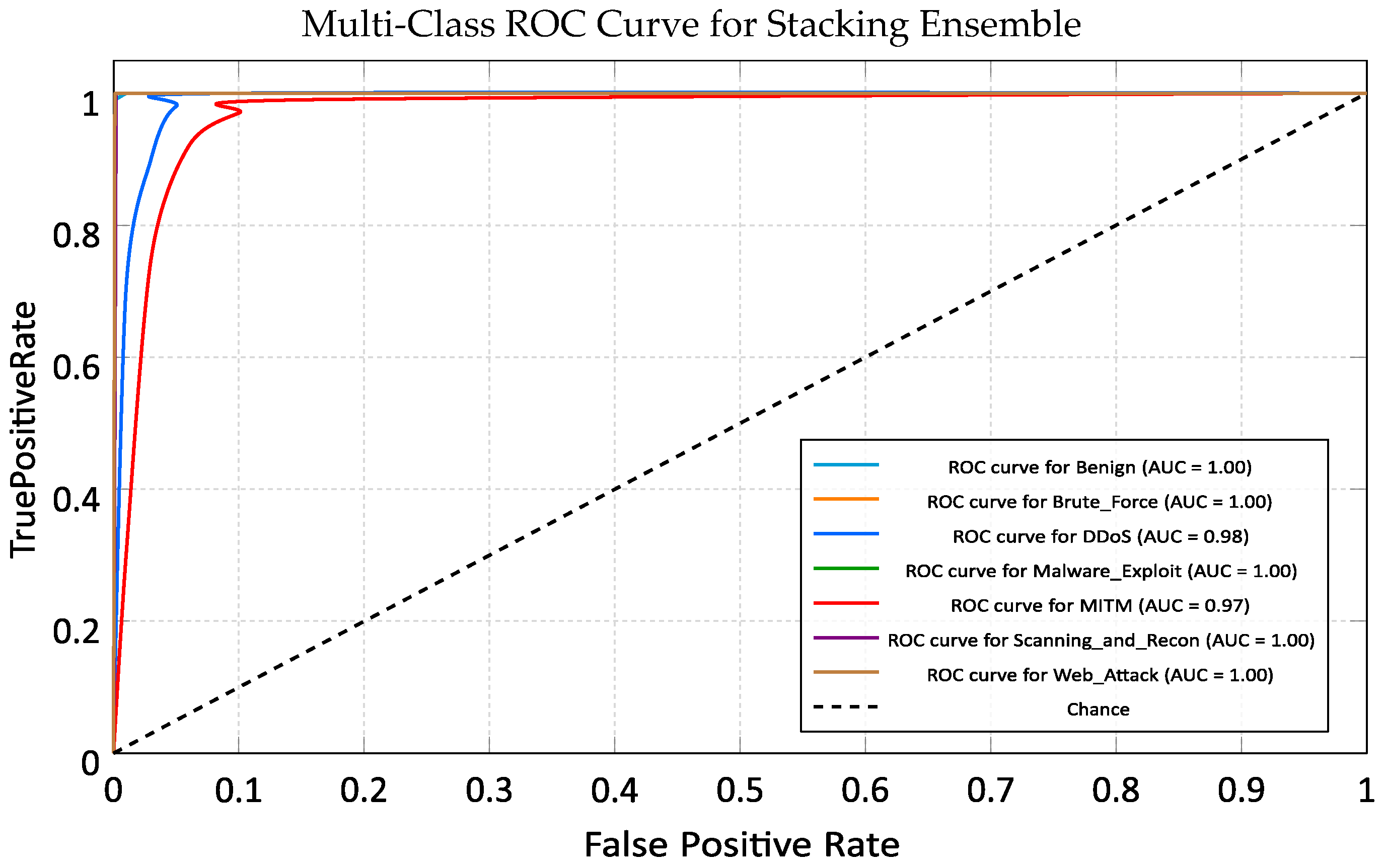

5.7. Stacking Ensemble (SE)

5.7.1. Training Performance Analysis

5.7.2. Cross-Domain Generalization on ACI-IoT Dataset

6. Discussion

6.1. Operational Efficiency vs. Detection Fidelity

- High-Latency Zone (Deep Learning): The GRU incurred the highest computational costs, requiring 93.63 s for inference over 10× slower than the tree-based models. This establishes a clear boundary, while the GRU is essential for temporal analysis, its latency prohibits its use as a primary, inline packet filter on low-power edge devices.

- Balanced Zone (Tree-Based Ensembles): The tree-based models represent the optimal balance for general application. XGBoost outperformed RF in both training speed (1331 s vs. 2386 s) and inference speed (7.30 s vs. 8.20 s), while maintaining statistically identical accuracy (≈99.7%).

- High-Efficiency Zone (SVM and Stacking): The SVM offered the lowest inference latency (0.84 s) but at the cost of unacceptable detection accuracy (62.30%). Conversely, the Stacking Ensemble, despite its architectural complexity, achieved an inference time of 3.32 s remarkably faster than the individual tree-based models while delivering the highest accuracy (99.98%). This suggests that the ensemble’s meta-learner efficiently shortcuts the decision process, making it a viable candidate for near-real-time systems.

6.2. Performance Analysis by Architecture

6.2.1. The Limitations of Linear Boundaries (SVM)

6.2.2. The Dominance of Tree-Based Ensembles (XGBoost)

6.2.3. Specialized Deep Learning Capabilities

- Autoencoder (Zero-Day Detection): With an AUC of 0.975 on the mixed dataset, the Autoencoder proved that reconstruction error is a reliable proxy for malicious intent. Its primary utility is not classification, but filtration identifying novel “unknown unknowns” that supervised models might misclassify as benign.

- GRU (Temporal Forensics): The GRU’s strength lies in its temporal context. While it suffered from lower recall on DDoS (0.95) compared to XGBoost, it achieved excellent generalization on complex, multi-stage attacks like Reconnaissance (AUC 0.991). However, due to its high inference latency, it is best suited for a retrospective role, analyzing session logs asynchronously rather than filtering live traffic.

6.3. The Stacking Ensemble: Synergy in Defense

6.4. Deployment Recommendations

- Tier 1 (Device Level): Deploy Autoencoders on edge devices. Their fast inference (3.56 s) and ability to flag anomalies without labeled data make them ideal for signaling when a device is behaving erratically.

- Tier 2 (Gateway Level): Deploy XGBoost. Its high throughput and generalization capabilities allow it to filter 99.7% of known threats at the network edge, preventing upstream congestion.

- Tier 3 (Cloud Level): Deploy the Stacking Ensemble and GRU. Traffic flagged as suspicious by Tier 1 or 2 is routed here for deep inspection. The GRU analyzes the temporal sequence, while the Ensemble provides the final, high-confidence classification.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

7.1. Answering the Research Questions

- RQ1: How can AI-powered models improve the detection of cyberattacks in diverse IoT environments compared to traditional methods?

- RQ2: What challenges, such as concept drift and feature space heterogeneity, arise when training and testing AI models across heterogeneous IoT datasets?

7.2. Final Model Recommendations and Future Work

- Lightweight Edge Deployment: Developing efficient, optimized versions of high-performing deep learning models (like GRU) and ensemble methods is critical. This involves exploring model quantization, knowledge distillation, and pruning techniques to enable effective detection directly on resource-constrained IoT and edge computing devices.

- Federated and Continual Learning: Implementing federated learning to train a global model collaboratively across diverse, distributed IoT networks could effectively address concept drift and feature heterogeneity in a privacy-preserving manner, allowing models to continually adapt to new environments without centralized data aggregation.

- Adversarial Resilience and XAI: Future dataset creation and modeling should explic-itly prioritize adversarial machine learning to stress-test model robustness against sophisticated evasion techniques. Furthermore, integrating XAI is vital to make the complex decisions of ensemble and deep learning models transparent and trustworthy for security analysts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Garadi, M.A.; Mohamed, A.; Al-Ali, A.K.; Du, X.; Ali, I.; Guizani, M.A. A survey of IoT: Applications, security, and private-preserving schemes. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2020, 22, 1646–1685. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Research Department. Number of Internet of Things (IoT) Connected Devices World-Wide from 2019 to 2030; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakakis, M.; April, T.; Bailey, M.; Bernhard, M.; Bursztein, E.; Cochran, J.; Durumeric, Z.; Halderman, J.A.; Invernizzi, L.; Kallitsis, M.; et al. Understanding the Mirai Botnet. In Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–18 August 2017; pp. 1093–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Khraisat, A.; Gondal, I.; Vamplew, P.; Kamruzzaman, J. Survey of intrusion detection systems: Techniques, datasets and challenges. Cybersecurity 2019, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczak, A.L.; Guven, E. A survey of data mining and machine learning methods for cyber security intrusion detection. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2015, 18, 1153–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Chaabouni, N.; Mosbah, M.; Zemmari, A.; Sauvignac, C.; Faruki, P. Network intrusion detection for IoT security based on learning tech-niques. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2671–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindy, H.; Brosset, D.; Bayne, E.; Seeam, A.K.; Tachtatzis, C.; Atkinson, R.; Bellekens, X. A comprehensive review of the CIC-IDS2017 dataset and a preliminary study on its usage for intrusion detection systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Big Data, Online, 10–13 December 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Arp, D.; Quiring, E.; Pendlebury, F.; Warnecke, A.; Pierazzi, F.; Wressnegger, C.; Cavallaro, L.; Rieck, K. DOS and DON’TS of Machine Learning in Computer Security. In Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Security Symposium, Virtual, 12–14 August 2020; pp. 3971–3988. [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa, N. A new distributed architecture for evaluating AI-based security systems at the edge: Network TON_IoT datasets. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 72, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrag, M.A.; Friha, O.; Hamouda, D.; Maglaras, L.; Janicke, H. Edge-IIoTset: A New Comprehensive Realistic Cyber Security Dataset for the Edge of Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 40281–40306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, S.; Pinto Neto, E.C.; Ferreira, R.; Molokwu, R.C.; Sadeghi, S.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoMT2024: Attack vectors in healthcare devices—A multi-protocol dataset for assessing IoMT device security. Preprints 2024, 28, 101351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshenko, N.; Bou-Harb, E.; Crichigno, J.; Kaddoum, G.; Ghani, N. Demystifying IoT security: An exhaustive survey of security vulnerabilities and defense mechanisms. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2702–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolias, C.; Kambourakis, G.; Stavrou, A.; Voas, J. DDoS in the IoT: Mirai and other botnets. Computer 2017, 50, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, I.; Ahmed, E.; Rehman, M.H.U.; Ahmed, A.I.A.; Al-Garadi, M.A.; Imran, M.; Guizani, M. The rise of ransomware and emerging security challenges in the Internet of Things. Comput. Netw. 2017, 129, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafaldin, I.; Lashkari, A.H.; Ghorbani, A.A. A detailed look at the CICIDS2017 dataset. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy, Funchal, Portugal, 22–24 January 2018; pp. 172–188. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, W.; Hu, J.; Slay, J.; Turnbull, B.P.; Xie, Y. A deep CNN-based approach for intrusion detection in the IoT. In Proceedings of the 21st Saudi Computer Society National Computer Conference (NCC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 25–26 April 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Panwar, H.; Gupta, P.; Monea, M.K.; Kumar, N. A deep learning based approach for intrusion detection in IoT network. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Security of Information and Networks, Jaipur, India, 13–15 October 2017; pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muna, A.H.; Moustafa, N.; Sitnikova, E. A comprehensive review of intrusion detection systems for IoT: A deep learning approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Papernot, N.; McDaniel, P.; Jha, S.; Fredrikson, M.; Celik, Z.B.; Swami, A. The limitations of deep learning in adversarial settings. In Proceedings of the IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy, Saarbrücken, Germany, 21–24 March 2016; pp. 372–387. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Bruna, J.; Erhan, D.; Goodfellow, I.; Fergus, R. Intriguing properties of neural networks. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6199. [Google Scholar]

- Carlini, N.; Wagner, D. Towards evaluating the robustness of neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Jose, CA, USA, 22–24 May 2017; pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Apruzzese, G.; Anderson, H.S.; Drichel, A.; Glukhov, V.; Hemberg, E.; Hoeschele, M.; Lashkari, A.H.; Lew, P.; Lupu, E.C.; Mittal, S. The Role of Machine Learning in Cybersecurity. In Proceedings of the ACM Computing Surveys, New York, NY, USA, 15 January 2023; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, M.; Zeng, X.; Ye, X.; Sheng, Y. Malware traffic classification using convolutional neural networks for representation learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN), Da Nang, Vietnam, 11–13 January 2017; pp. 712–717. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurada, M.; Yairi, T. Anomaly detection using autoencoders with nonlinear dimensionality reduction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the MLSDA 2014 2nd Workshop on Machine Learning for Sensory Data Analysis, Gold Coast, Australia, 2 December 2014; pp. 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky, Y.; Doitshman, T.; Elovici, Y.; Shabtai, A. Kitsune: An ensemble of autoencoders for online network intrusion detection. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS), San Diego, CA, USA, 18–21 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1724–1734. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Year | IoT Domain | Key Attack Types | Samples (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ToN-IoT [10] | 2021 | IIoT and General | DDoS, Ransomware, XSS, Backdoor | 22,339,000 |

| Edge-IIoTset [11] | 2022 | Industrial Edge | MQTT-BF, Injection, MITM, Scanning | 2,200,000 |

| IoT-2023 | 2023 | General IoT | Mirai, Spoofing, Reconnaissance | 46,700,000 |

| ACI-IoT | 2023 | Adversarial | Perturbed Traffic (Adversarial Examples) | 1,200,000 |

| IoMT-2024 [12] | 2024 | Medical (IoMT) | MIM, Data Exfiltration, Spoofing | 8,700,000 |

| Algorithm | Rationale for Selection (Justification) | Role in Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Machine Learning (ML) | ||

| Random Forest (RF) | Chosen as a robust and efficient model. RF performs well on large datasets with many features and naturally resists fitting too closely to the training data (overfitting). | Assesses the performance ceiling of efficient tree-based methods. |

| XGBoost | Selected as a leading gradient boosting technique. It is recognized for its computational speed and ability to achieve top-tier performance by aggressively correcting mistakes from previous iterations. | Represents state-of-the-art ensemble tree methods. |

| SVM | Included as a method that finds the clearest separation boundary between attack and normal data. It provides a strong, non-probabilistic approach for complex classification tasks. | Acts as a strong, non-probabilistic classification benchmark. |

| Deep Learning (DL) Architectures | ||

| CNN | We adapted the CNN to process network flows as a stream of features. It is effective at finding short, local patterns and hidden, hierarchical relationships within the feature set. | Captures local and hierarchical features within the flow data. |

| GRU | Chosen for its efficiency in handling sequential data. The GRU models how network traffic changes over time, which is key to finding multi-stage attacks, using fewer resources than older recurrent networks. | Captures temporal patterns in network sessions with high efficiency. |

| Autoencoder (AE) | Used for unsupervised anomaly detection. It is trained only on normal traffic; any high error in recreating a new flow signals an anomaly or potential unknown (zero-day) attack. | Assesses capacity for unsupervised anomaly and zero-day attack detection. |

| Hybrid Approach | ||

| Stacking Ensemble | Created to combine the strengths of multiple models. The ensemble integrates predictions from the individual top-performing models using a meta-learner to make a final, more stable, and accurate decision. | Aims for superior, generalizable performance across heterogeneous datasets. |

| Model | Key Hyperparameters | Selected Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| SVM (SGD) | Loss Function Alpha (Regularization) | Hinge (Linear SVM) 3.18 |

| Random Forest | n_estimators (Trees) Max Depth | 100 None (Full Expansion) |

| XGBoost | Learning Rate Max Depth | 0.1 10 |

| n_estimators | 1000 | |

| CNN | Architecture Kernel Size | 2 Conv1D Layers (32, 128 filters) 3 |

| Optimizer | Adam (lr = 0.001) | |

| GRU | Hidden Units Sequence Length | 128 (2 Layers) 4 flows |

| Dropout Rate | 0.2 | |

| Autoencoder | Latent Dimension Anomaly Threshold | 16 0.000331 (95th Percentile) |

| Stacking Ensemble | Meta-Learner | XGBoost Classifier |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 451,922 |

| Brute Force | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 451,922 |

| DDoS | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 451,922 |

| DoS Botnet | 0.46 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 451,922 |

| Malware Exploit | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 451,923 |

| MITM | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 451,923 |

| Scanning and Recon | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 451,922 |

| Web Attack | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 451,923 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 3,615,379 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| Brute Force | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| DDoS | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| DoS Botnet | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| Malware Exploit | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,923 |

| MITM | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,923 |

| Scanning and Recon | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| Web Attack | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,923 |

| Weighted Avg | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3,615,379 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| Brute Force | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| DDoS | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| DoS Botnet | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| Malware Exploit | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,923 |

| MITM | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,923 |

| Scanning and Recon | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| Web Attack | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,923 |

| Weighted Avg | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3,615,379 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 451,922 |

| Brute_Force | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 451,922 |

| DDoS | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| DoS_Botnet | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 451,922 |

| Malware_Exploit | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 451,923 |

| MITM | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 451,923 |

| Scanning_and_Recon | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 451,922 |

| Web_Attack | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 451,923 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 3,615,379 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 454,133 |

| Malicious | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 |

| Accuracy | 0.95 | 454,133 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 454,133 |

| Weighted Avg | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 454,133 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 753,203 |

| Brute_Force | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 753,203 |

| DDos | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 753,203 |

| DoS_Botnet | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 753,204 |

| MITM | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 753,204 |

| Malware_Exploit | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 753,204 |

| Scanning_and_Recon | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 753,204 |

| Web_Attack | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 753,204 |

| Accuracy | 0.99 | 6,025,629 | ||

| Macro Avg | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 6,025,629 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 6,025,629 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| Brute_Force | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| DDos | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| DoS_Botnet | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,923 |

| MITM | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| Malware_Exploit | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| Scanning_and_Recon | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,923 |

| Web_Attack | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 451,922 |

| Accuracy | 1.00 | 3,615,378 | ||

| Macro Avg | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3,615,378 |

| Weighted Avg | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3,615,378 |

| Model | Acc. (%) | Gen. (AUC) | Train Time (s) | Infer. Time (s) | Optimal Deployment Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 62.30 | 0.21 (Poor) | 2017 | 0.84 | Legacy/Microcontroller: Simple pre-filtering on constrained hardware for detecting scanning activity only. |

| Random Forest | 99.77 | 0.99 (Exc.) | 2386 | 8.20 | General Purpose: Robust baseline for standard IoT gateways; high resistance to overfitting. |

| XGBoost | 99.74 | 0.99 (Exc.) | 1331 | 7.30 | Edge Gateway Standard: Best all-rounder. Recommended for primary deployment on IoT Hubs due to optimal speedaccuracy balance. |

| CNN | 98.93 | 0.98 (Good) | 4550 | 29.37 | Packet Inspection: Best suited for inputs where feature engineering is difficult (e.g., raw payload bytes). |

| Autoencoder | N/A | 0.975 | 438 | 3.56 | Zero-Day Filter: Anomaly detection layer. Should sit in front of a classifier to flag unknown threats. |

| GRU | 99.30 | 0.99 (Exc.) | 2534 | 93.63 | Forensic Analysis: Too slow for real-time edge blocking. Best used for offline analysis of session logs (low-and-slow attacks). |

| Stacking Ens. | 99.98 | 1.00 (Perf.) | 303 * | 3.32 | Cloud Core/SIEM: The ultimate defense engine. Deployed in the cloud to aggregate alerts with near-zero false positives. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quaye, S.; Khan, A.H.; Tapre, K.; Dawson, M. AI-Powered Cybersecurity Models for Training and Testing IoT Devices. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13073. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413073

Quaye S, Khan AH, Tapre K, Dawson M. AI-Powered Cybersecurity Models for Training and Testing IoT Devices. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13073. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413073

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuaye, Samson, Abdul Hadi Khan, Kshitij Tapre, and Maurice Dawson. 2025. "AI-Powered Cybersecurity Models for Training and Testing IoT Devices" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13073. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413073

APA StyleQuaye, S., Khan, A. H., Tapre, K., & Dawson, M. (2025). AI-Powered Cybersecurity Models for Training and Testing IoT Devices. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13073. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413073