Prediction of Soft Soil Settlement Based on Ensemble Smoother with Multiple Data Assimilation

Abstract

1. Introduction

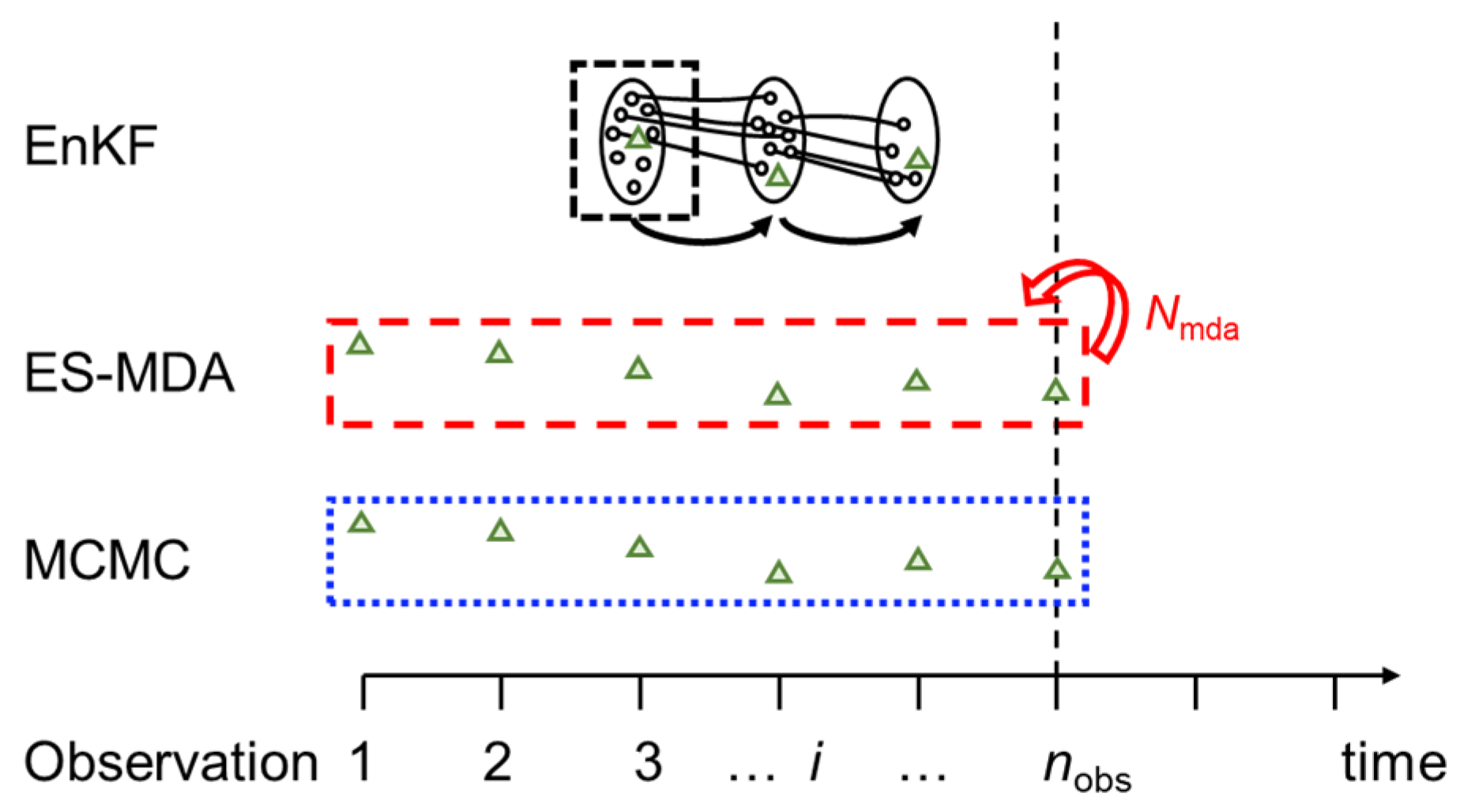

2. Bayesian Updating Framework

3. Case Study

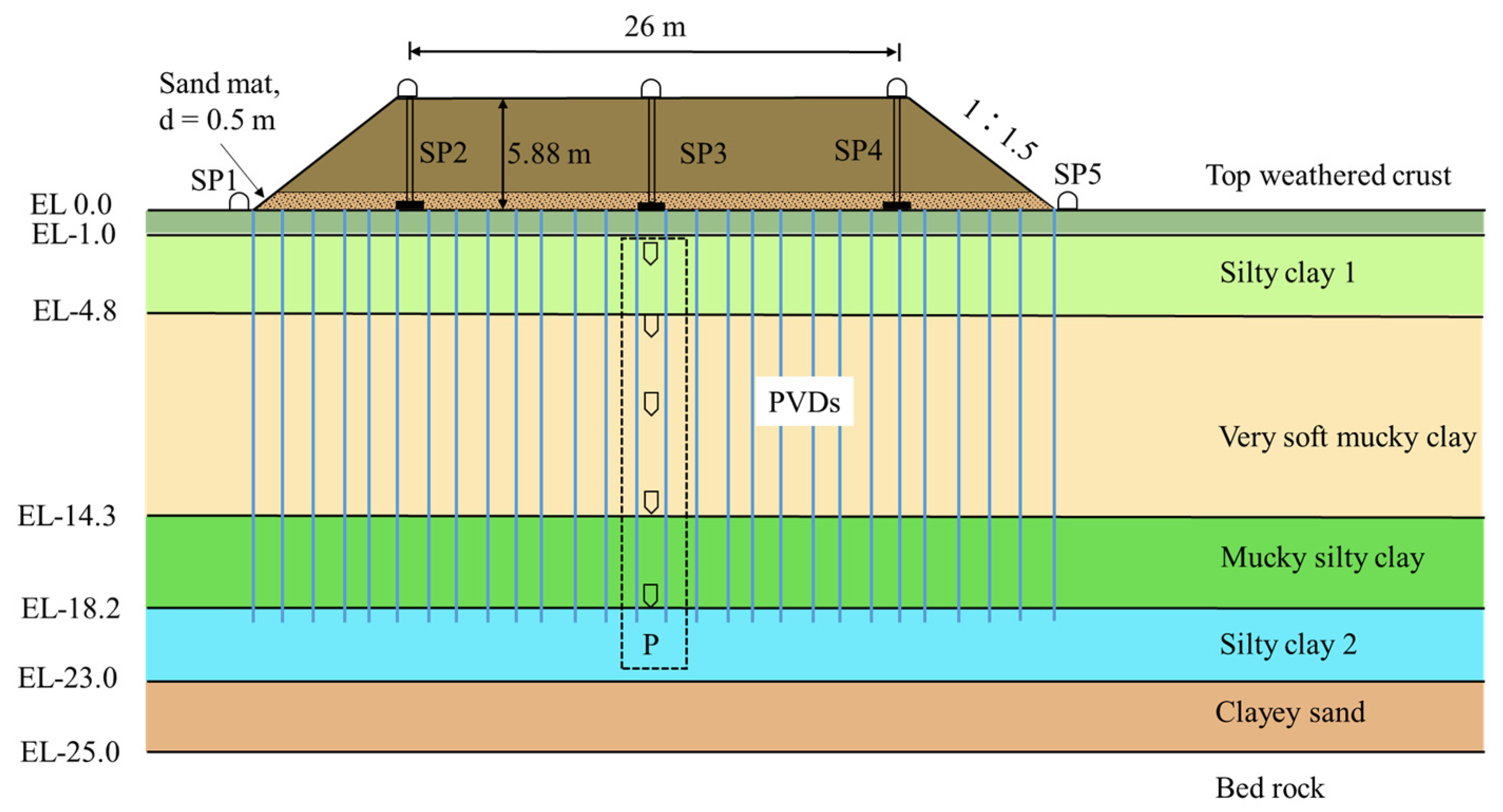

3.1. Project Overview

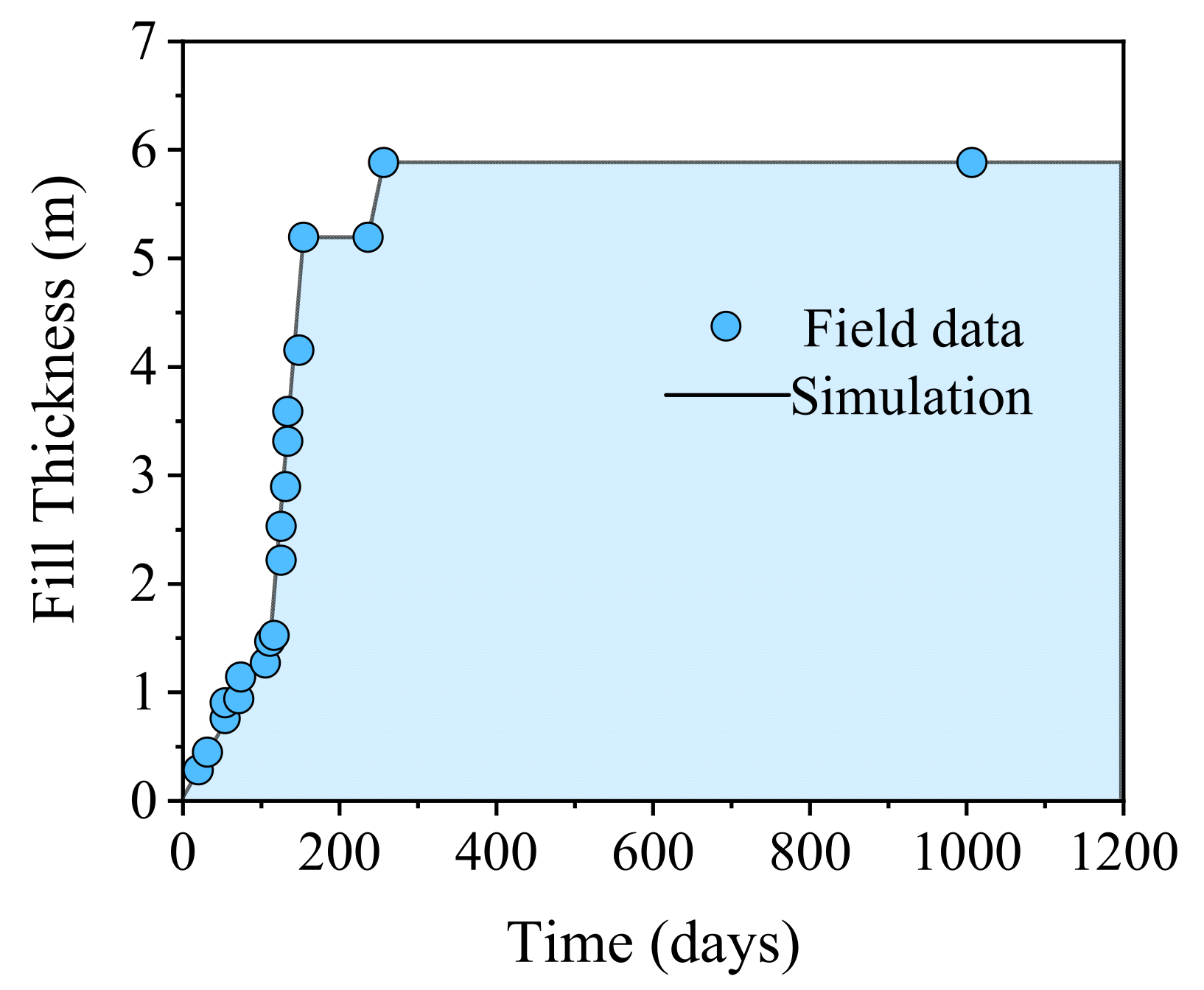

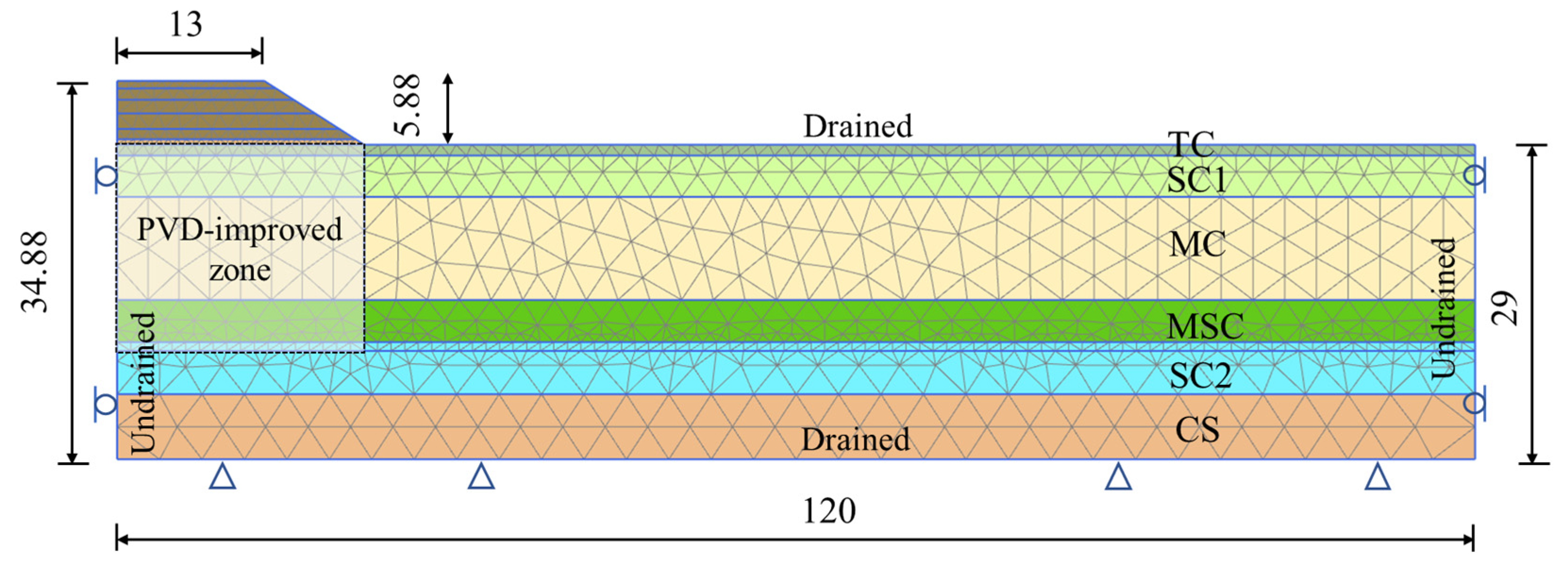

3.2. Numerical Simulation

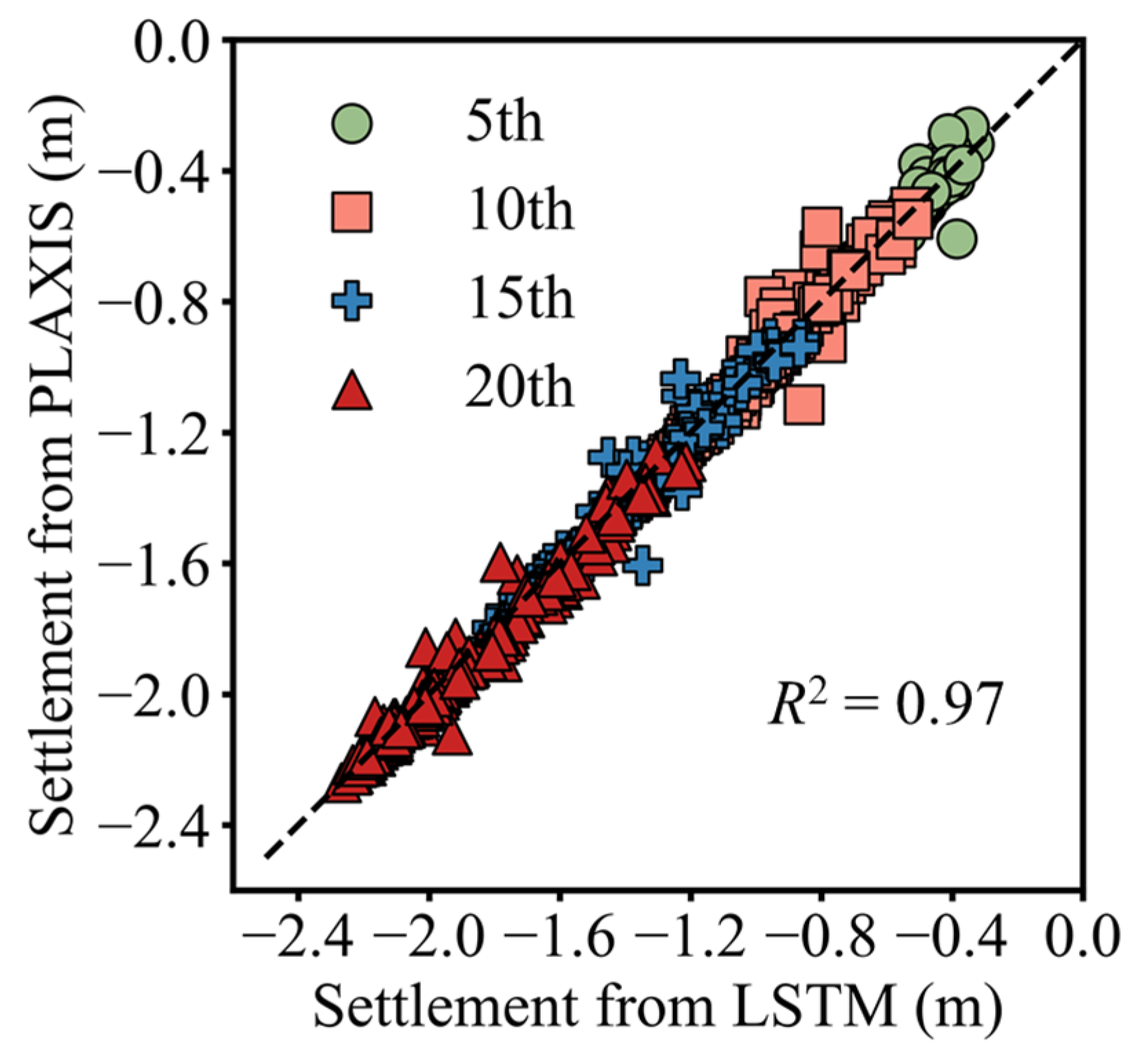

3.3. Surrogate Model

4. Results and Discussion

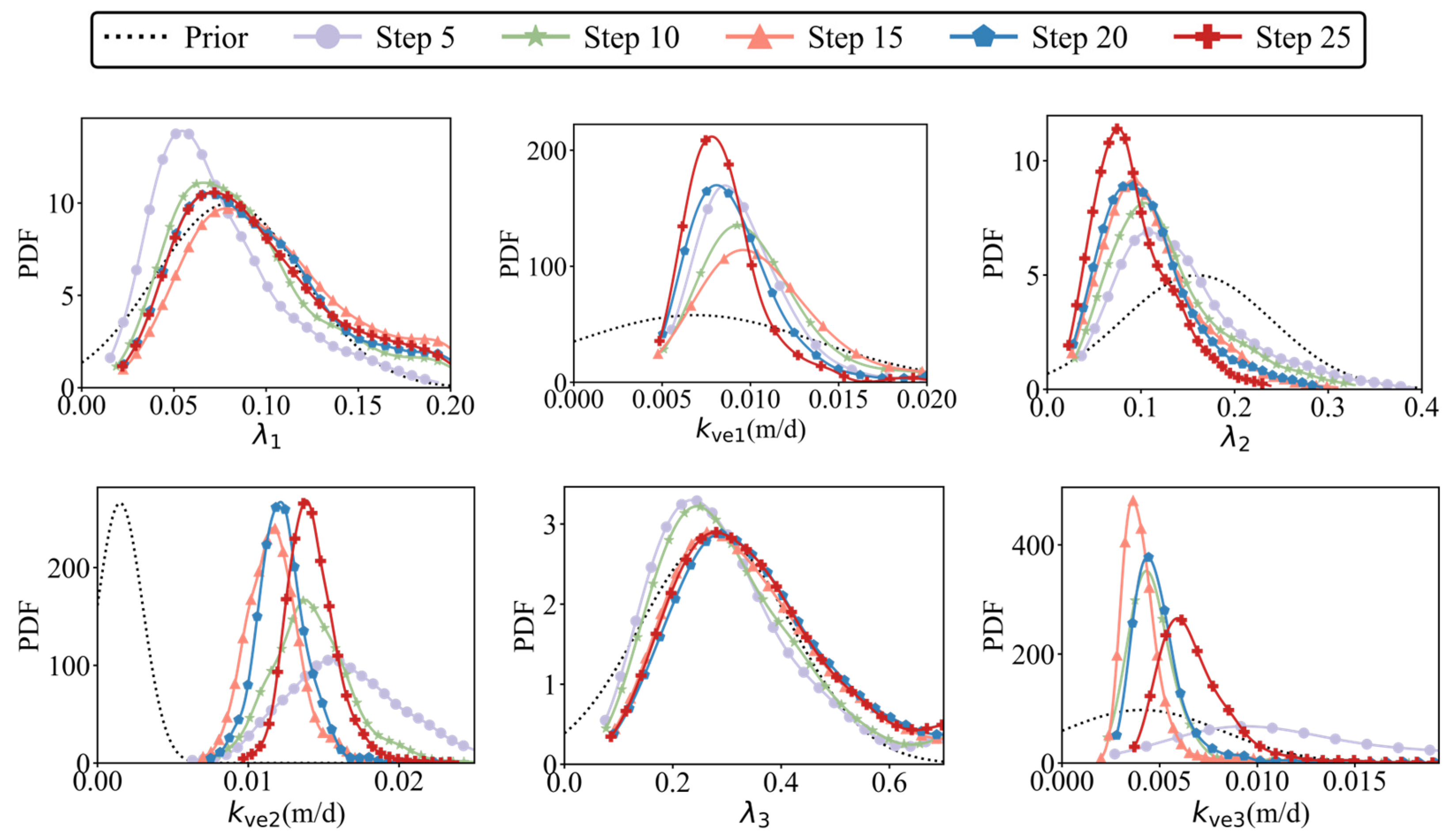

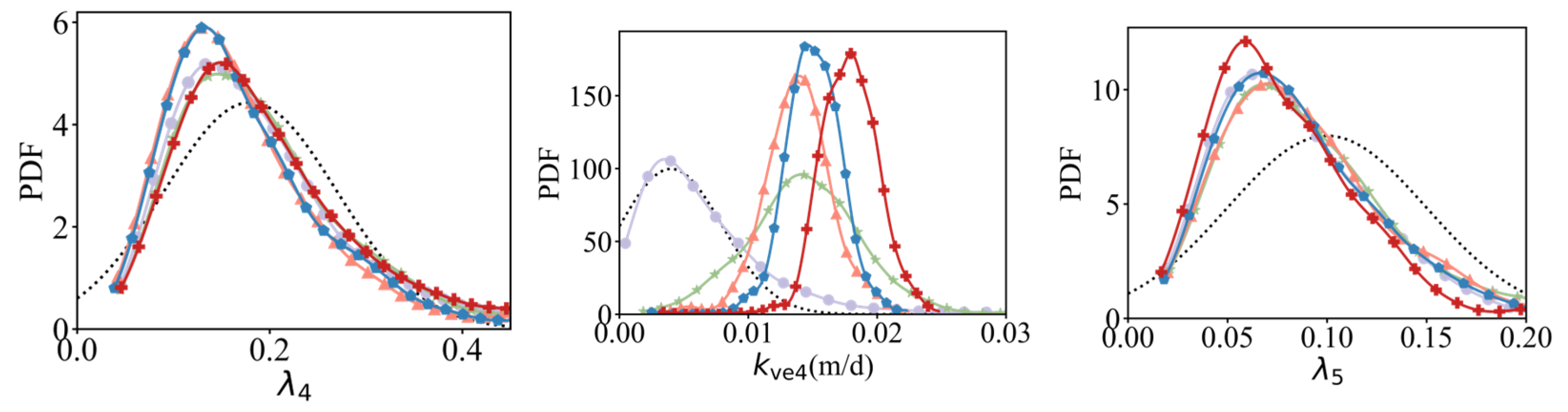

4.1. Updated Soil Parameters

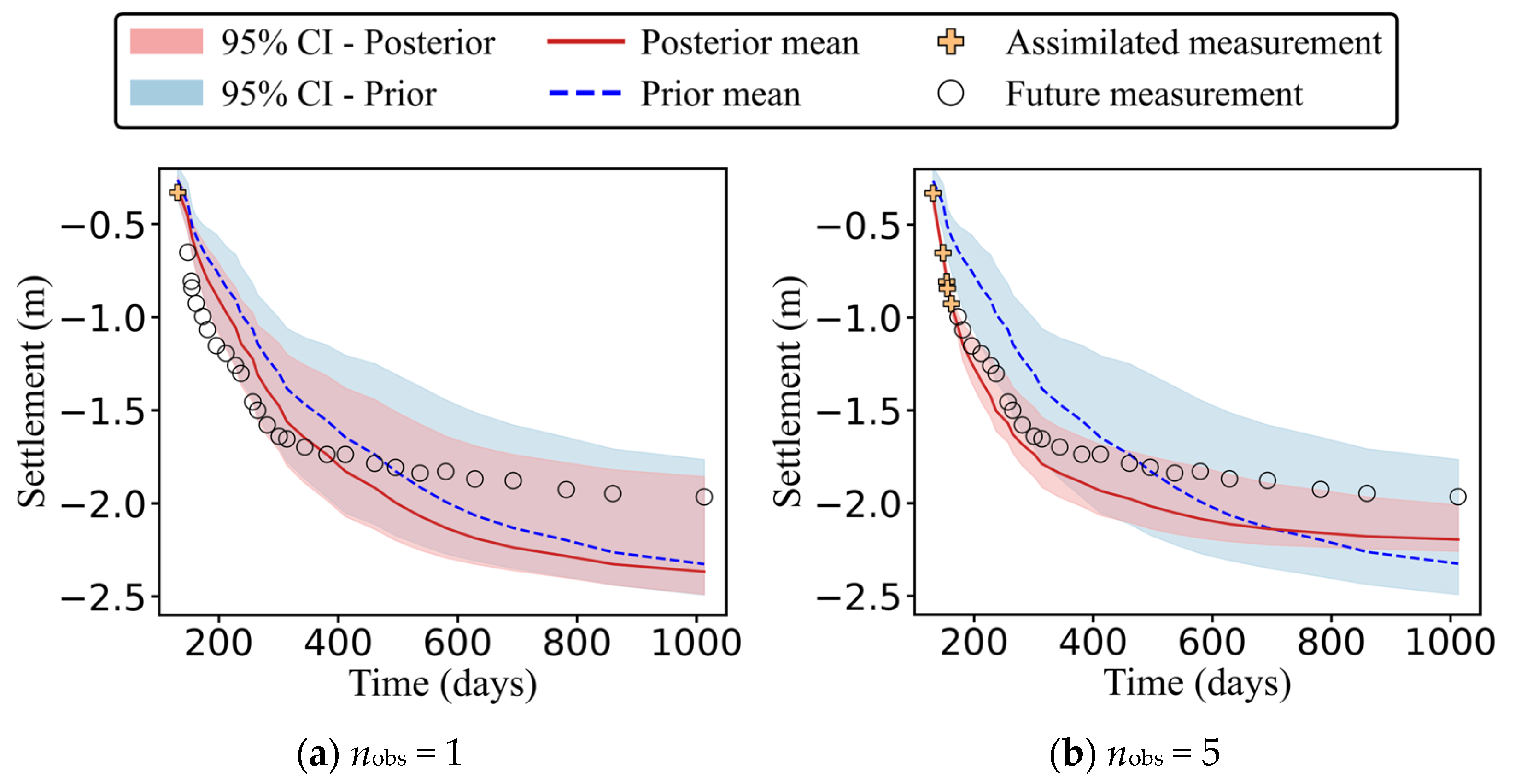

4.2. Settlement Prediction

4.3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- In terms of parameter updating, ES-MDA can adaptively refine key consolidation parameters, including the compression index λ and the equivalent vertical permeability kve of each soil layer, by progressively assimilating field monitoring data. Compared with the prior parameters derived from limited oedometer tests and empirical estimates, the posterior probability density functions become more concentrated, and their means exhibit significant shifts, indicating biases in the initial parameter values. The prior mean compression index λ obtained from laboratory tests tends to be overestimated, whereas the prior mean vertical permeability tends to be underestimated. After ES-MDA updating, both compressibility and drainage capacity are adjusted in a manner more consistent with the observed settlement response, and the uncertainty in the parameters is significantly reduced, providing a more reliable basis for subsequent settlement prediction.

- (2)

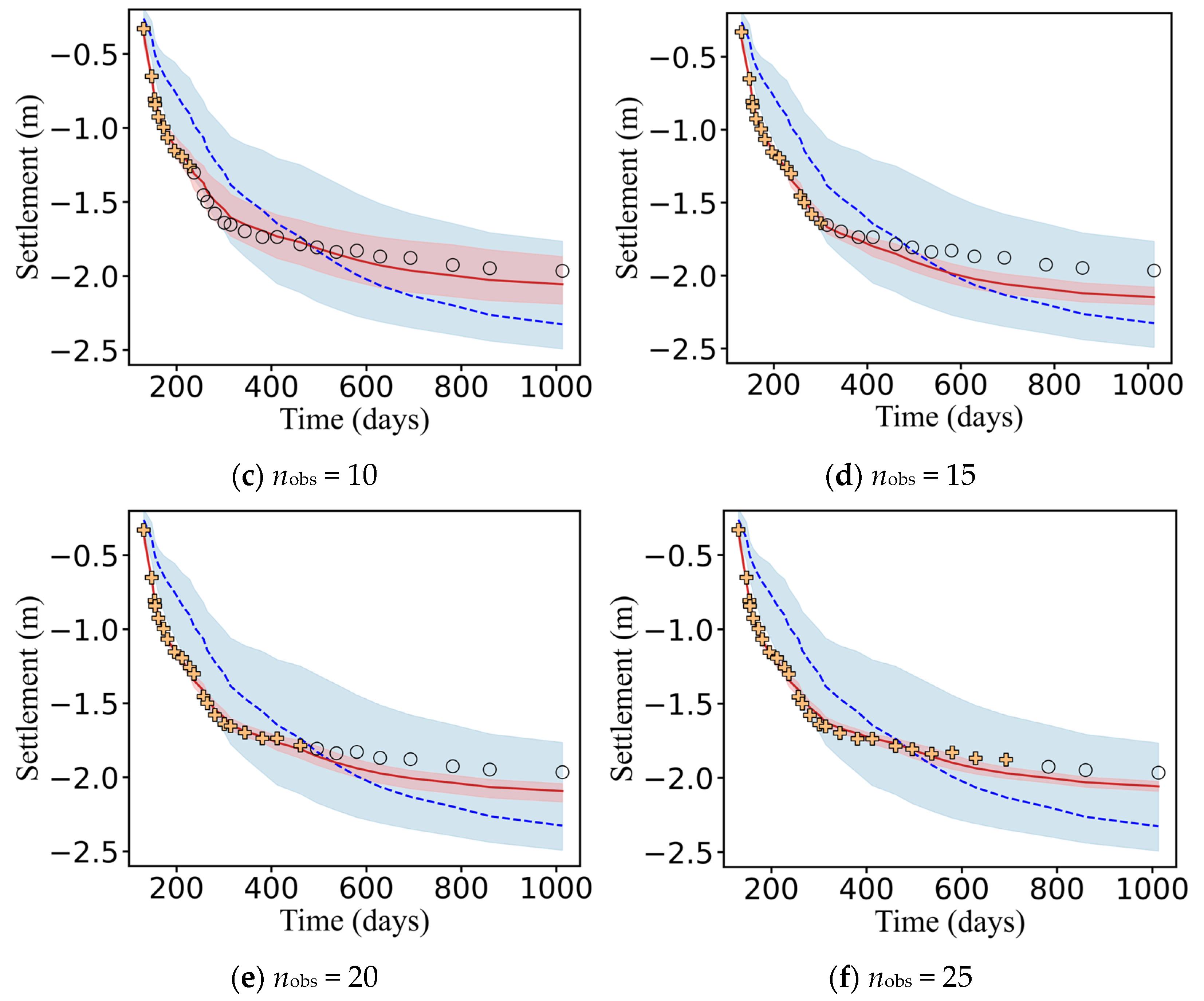

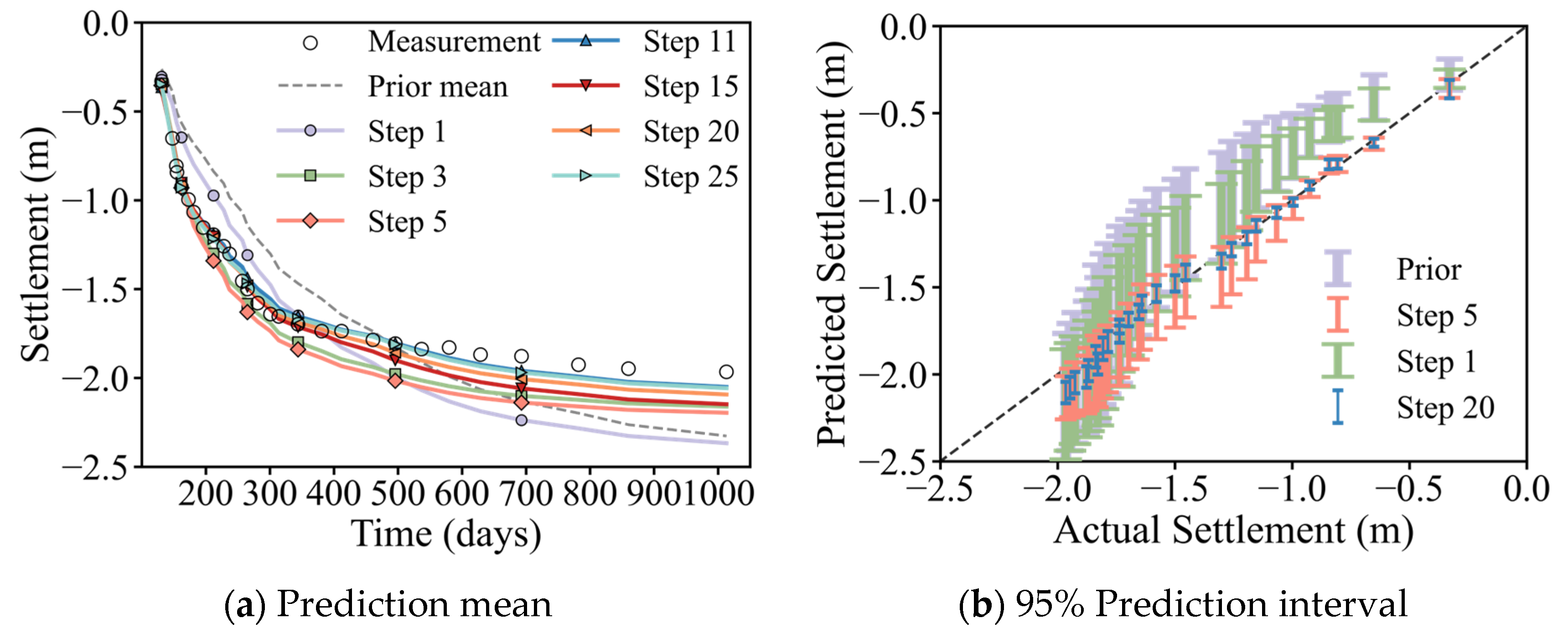

- Regarding settlement prediction and uncertainty characterization, ES-MDA effectively exploits early-stage monitoring data to substantially improve long-term settlement prediction performance. Predictions based on prior parameters exhibit a wide 95% prediction interval and a pronounced bias between the predicted mean settlements and the measured values. After assimilating a limited number of observations, the agreement between the predicted mean and the monitoring history improves markedly, and the prediction interval narrows significantly, leading to reduced bias and uncertainty. As more observations are assimilated, prediction errors may exhibit slight and localized increases at certain stages; however, the overall prediction accuracy and stability are considerably superior to those based on the prior parameters. This indicates that, while preserving physical interpretability, the proposed method can provide robust long-term settlement predictions for embankments on soft soil.

- (3)

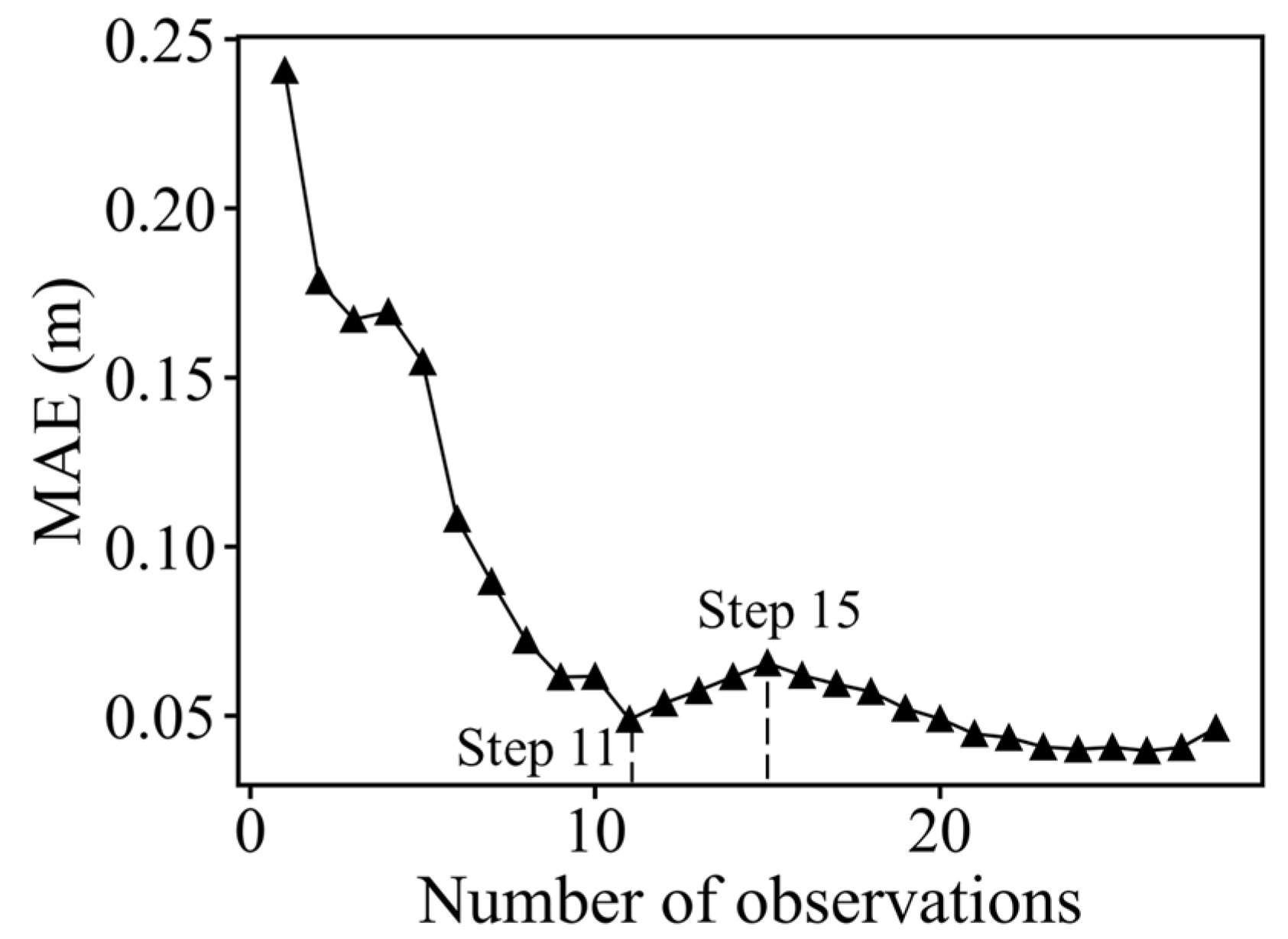

- The influence of monitoring data volume and the sensitivity of the method are studied. As the number of assimilated observations increases, the settlement prediction error generally decreases and gradually stabilizes, although a local error peak appears when the number of assimilated monitoring points lies between 11 and 15. This behavior is closely related to the abrupt increase in the settlement rate at the 11th monitoring time. To reproduce this short-term high settlement rate, ES-MDA updates the soil properties accordingly, resulting in an overestimation of settlements at other stages. As subsequent observations are assimilated, the settlement rate returns to a more moderate level, the predicted mean settlements move back towards the measured values, the errors decrease again, and the width of the prediction intervals remains stable. This behavior demonstrates that ES-MDA is sensitive to abrupt changes in ground response, which is beneficial for identifying changes in loading or boundary conditions, but also implies that short-term anomalous monitoring data should be interpreted and used for parameter updating with careful consideration of field conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C. A simplified method for prediction of embankment settlement in clays. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2014, 6, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.I.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, H.Y. Field performance of a genetic algorithm in the settlement prediction of a thick soft clay deposit in the southern part of the Korean peninsula. Eng. Geol. 2015, 196, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Fatahi, B.; Khabbaz, H.; Nguyen, H.H.; Kelly, R. Field study and numerical modelling for a road embankment built on soft soil improved with concrete injected columns and geosynthetics reinforced platform. Geotext. Geomembr. 2021, 49, 804–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venda Oliveira, P.J.; Araújo Santos, L.M.; Almeida e Sousa, J.N.V.; Lemos, L.J.L. Effect of initial stiffness on the behaviour of two geotechnical structures: An embankment and a tunnel. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 136, 104181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müthing, N.; Zhao, C.; Hölter, R.; Schanz, T. Settlement prediction for an embankment on soft clay. Comput. Geotech. 2018, 93, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Phoon, K.-K.; Yuan, J.; Tao, Y.; Sun, H. Variability in Geostructural Performance Predictions. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part A Civ. Eng. 2025, 11, 03124003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Phoon, K.-K. Model Uncertainties in Foundation Design; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y.; Zeng, S.; Ying, T.; Sun, H.; Pan, S.; Cai, Y. A deep transfer learning model for the deformation of braced excavations with limited monitoring data. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 1555–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Phoon, K.-K.; Sun, H.; Ching, J. Variance reduction function for a potential inclined slip line in a spatially variable soil. Struct. Saf. 2024, 106, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cami, B.; Javankhoshdel, S.; Phoon, K.-K.; Ching, J. Scale of Fluctuation for Spatially Varying Soils: Estimation Methods and Values. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part A Civ. Eng. 2020, 6, 03120002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoon, K.-K.; Kulhawy, F.H. Evaluation of geotechnical property variability. Can. Geotech. J. 1999, 36, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, J.; Wu, T.-J. Probabilistic transformation models for preconsolidation stress based on clay index properties. Eng. Geol. 2017, 226, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, J.Y.; Lin, G.H.; Chen, J.R.; Phoon, K.K. Transformation models for effective friction angle and relative density calibrated based on generic database of coarse-grained soils. Can. Geotech. J. 2017, 54, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.B.; Sloan, S.W.; Pineda, J.A.; Kouretzis, G.; Huang, J. Outcomes of the Newcastle symposium for the prediction of embankment behaviour on soft soil. Comput. Geotech. 2018, 93, 9–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, J.P.; Gourvenec, S.; Gaone, F.M.; Pineda, J.A.; Kelly, R.; O’Loughlin, C.D.; Cassidy, M.J.; Sloan, S.W. A novel web based application for storing, managing and sharing geotechnical data, illustrated using the national soft soil field testing facility in Ballina, Australia. Comput. Geotech. 2018, 93, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Wang, G.; Sun, H.; Tao, Y.; Pan, X. A semi-supervised dual-path model for underground defect detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 158, 111493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Zeng, S.; Sun, H.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pan, X. A spatiotemporal deep learning method for excavation-induced wall deflections. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 16, 3327–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.K.; Loh, D.R.D.; Chian, S.C.; Ku, T. Probabilistic Prediction of Consolidation Settlement and Pore Water Pressure Using Variational Autoencoder Neural Network. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2023, 149, 04022119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-S.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, A.; Shen, S.-L. Time-series prediction of shield movement performance during tunneling based on hybrid model. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 119, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, F.; Sargent, P.; Montague, G. The use of PCA and signal processing techniques for processing time-based construction settlement data of road embankments. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 46, 101181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.K.; Leung, Y.F. Bayesian updating of subsurface spatial variability for improved prediction of braced excavation response. Can. Geotech. J. 2019, 56, 1169–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zeng, C.; Kelly, R. Back analysis of settlement of Teven Road trial embankment using Bayesian updating. Georisk Assess. Manag. Risk Eng. Syst. Geohazards 2019, 13, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.-H.; Zhou, W.-H. An efficient probabilistic back-analysis method for braced excavations using wall deflection data at multiple points. Comput. Geotech. 2017, 85, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, A.; Shinmura, H.; Ohno, S.; Fujisawa, K. Model identification and parameter estimation of elastoplastic constitutive model by data assimilation using the particle filter. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2017, 42, 110–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Huang, J.; Kelly, R.; Jones, M.; Kamruzzaman, A.H.M. Predicting settlement of embankments built on PVD-improved soil using Bayesian back analysis and elasto-viscoplastic modelling. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 157, 105323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Sun, H.; Cai, Y. Predictions of Deep Excavation Responses Considering Model Uncertainty: Integrating BiLSTM Neural Networks with Bayesian Updating. Int. J. Geomech. 2022, 22, 04021250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Cao, Z.; Li, D.; Du, W.; Zhang, F. Efficient and flexible Bayesian updating of embankment settlement on soft soils based on different monitoring datasets. Acta Geotech. 2021, 17, 1273–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.; Huang, J. Bayesian updating for one-dimensional consolidation measurements. Can. Geotech. J. 2015, 52, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amavasai, A.; Tahershamsi, H.; Wood, T.; Dijkstra, J. Data assimilation for Bayesian updating of predicted embankment response using monitoring data. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 165, 105936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Pan, S.; Sun, H.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, G.; Sun, M. A bi-fidelity inverse analysis method for deep excavations considering three-dimensional effects. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2024, 48, 2471–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Sun, H.; Cai, Y. Bayesian inference of spatially varying parameters in soil constitutive models by using deformation observation data. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2021, 45, 1647–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Sun, H.; Cai, Y. Predicting soil settlement with quantified uncertainties by using ensemble Kalman filtering. Eng. Geol. 2020, 276, 105753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Vardon, P.J.; Hicks, M.A. Sequential reduction of slope stability uncertainty based on temporal hydraulic measurements via the ensemble Kalman filter. Comput. Geotech. 2018, 95, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardon, P.J.; Liu, K.; Hicks, M.A. Reduction of slope stability uncertainty based on hydraulic measurement via inverse analysis. Georisk Assess. Manag. Risk Eng. Syst. Geohazards 2016, 10, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommels, A.; Murakami, A.; Nishimura, S.-I. Comparison of the Ensemble Kalman filter with the Unscented Kalman filter: Application to the construction of a road embankment. In Proceedings of the 19th European Young Geotechnical Engineers Conference, Gyor, Hungary, 3–6 September 2008; pp. 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Evensen, G.; van Leeuwen, P.J. An Ensemble Kalman Smoother for Nonlinear Dynamics. Mon. Weather Rev. 2000, 128, 1852–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, P.J.; Evensen, G. Data Assimilation and Inverse Methods in Terms of a Probabilistic Formulation. Mon. Weather Rev. 1996, 124, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerick, A.A.; Reynolds, A.C. Ensemble smoother with multiple data assimilation. Comput. Geosci. 2013, 55, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, C.H.; Luo, Z.; Atamturktur, S.; Huang, H.W. Bayesian Updating of Soil Parameters for Braced Excavations Using Field Observations. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2013, 139, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, M.A.; Law, K.J.H.; Stuart, A.M. Evaluation of Gaussian approximations for data assimilation in reservoir models. Comput. Geosci. 2013, 17, 851–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Huang, J.S.; Li, D.Q.; Kelly, R.; Sloan, S.W. Embankment prediction using testing data and monitored behaviour: A Bayesian updating approach. Comput. Geotech. 2018, 93, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerick, A.A.; Reynolds, A.C. History matching time-lapse seismic data using the ensemble Kalman filter with multiple data assimilations. Comput. Geosci. 2012, 16, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.-C.; Shen, S.-L.; Miura, N.; Bergado, D.T. Simple Method of Modeling PVD-Improved Subsoil. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2001, 127, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Shrestha, S.; Hino, T.; Ding, W.; Kamo, Y.; Carter, J. 2D and 3D analyses of an embankment on clay improved by soil–cement columns. Comput. Geotech. 2015, 68, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuku, T.; Murakami, A.; Nishimura S-i Fujisawa, K.; Nakamura, K. Parameter identification for Cam-clay model in partial loading model tests using the particle filter. Soils Found. 2012, 52, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, A.; Uysal, F. Modelling of anisotropy and consolidation effect on behaviour of sunshine embankment: Australia. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 14, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, J.J.; Jayawickrama, P.W.; Ekwaro-Osire, S. Uncertainty Analysis in Prediction of Settlements for Spatial Prefabricated Vertical Drains Improved Soft Soil Sites. Geosciences 2020, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Fityus, S.; Bishop, D.; Smith, D.; Sheng, D. Finite-Element Parametric Study of the Consolidation Behavior of a Trial Embankment on Soft Clay. Int. J. Geomech. 2006, 6, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, K.L.; Pinder, G.F.; Belitz, K. Comparison of the lognormal and beta distribution functions to describe the uncertainty in permeability. J. Hydrol. 2005, 313, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layer | γ (kN/m3) | e0 | E′ (kPa) | ν | λ | κ | M | kh (10−3 m/d) | kv (10−3 m/d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fill | 20.0 | 30,000 | 0.25 | 32.3 | 32.3 | ||||

| TC | 19.3 | 0.81 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.008 | 1.0 | 0.45 | 0.54 | |

| SC1 | 18.5 | 1.07 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.016 | 1.0 | 0.09 | 0.04 | |

| MC | 17.3 | 1.36 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.028 | 0.8 | 0.42 | 0.24 | |

| MSC | 17.9 | 1.10 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.018 | 0.8 | 0.34 | 0.17 | |

| SC2 | 19.3 | 0.81 | 0.30 | 0.1 | 0.010 | 1.0 | 0.07 | 0.03 | |

| CS | 19.5 | 25,000 | 0.25 | 4.32 | 4.32 |

| Item | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Width (mm) | w | 100 |

| Thickness (mm) | t | 6 |

| Drain spacing (m) | SL | 1.5 |

| Drainage length (m) | l | 19 |

| Drain diameter (mm) | dw | 53 |

| Smear zone diameter (mm) | ds | 355 |

| Ratio of kh over ks in field | (kh/ks)f | 13.5 |

| ds/dw | s | 6.7 |

| Diameter of influential zone (m) | De | 1.575 |

| De/dw | n | 29.72 |

| Discharge capacity (m3/a) | qw | 100 |

| Layer | Variable | Mean | Coefficient of Variance (COV) | Distribution Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC | λ1 (kPa) | 0.08 | 0.5 | Lognormal distribution |

| kve1 (m/d) | 6.9 × 10−3 | 1 | ||

| SC1 | λ2 | 0.16 | 0.5 | |

| kve2 (m/d) | 1.5 × 10−3 | 1 | ||

| MC | λ3 | 0.28 | 0.5 | |

| kve3 (m/d) | 4.1 × 10−3 | 1 | ||

| MSC | λ4 | 0.18 | 0.5 | |

| kve4 (m/d) | 4 × 10−3 | 1 | ||

| SC2 | λ5 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Term | Value |

|---|---|

| Loss function | MSE |

| Optimization algorithm | Adam |

| Hidden layer | 2 |

| Hidden dimension | 128 |

| Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Batch size | 16 |

| Epoch | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, P.; Zhou, Z.; Ma, D.; Pan, X.; Wu, F.; Wang, M. Prediction of Soft Soil Settlement Based on Ensemble Smoother with Multiple Data Assimilation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13074. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413074

Zhao P, Zhou Z, Ma D, Pan X, Wu F, Wang M. Prediction of Soft Soil Settlement Based on Ensemble Smoother with Multiple Data Assimilation. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13074. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413074

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Pan, Zeling Zhou, Delian Ma, Xiaodong Pan, Fan Wu, and Mingyuan Wang. 2025. "Prediction of Soft Soil Settlement Based on Ensemble Smoother with Multiple Data Assimilation" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13074. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413074

APA StyleZhao, P., Zhou, Z., Ma, D., Pan, X., Wu, F., & Wang, M. (2025). Prediction of Soft Soil Settlement Based on Ensemble Smoother with Multiple Data Assimilation. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13074. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413074