Investigation of In Situ Strategy Based on Zn/Al-Layered Double Hydroxides for Enhanced PFOA Removal: Adsorption Mechanism and Fluoride Effect

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Analytical Methods and Characterization

2.3. In Situ Removal Experiments

2.4. Ex Situ Removal Experiments

2.5. Simulation Method

2.6. Calculation Method

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Comparison of the In Situ and Ex Situ Methods

3.1.1. Adsorption Kinetics

3.1.2. Adsorption Isotherm

3.1.3. Effect of the Fluoride Ion Addition

3.2. Mechanism Investigation of the Fluoride Ion Effect for the In Situ Method

3.2.1. Effect of pH

3.2.2. Effect of the Ionic Strengths

3.2.3. Solid Phase Analysis

- Characterization

- 2.

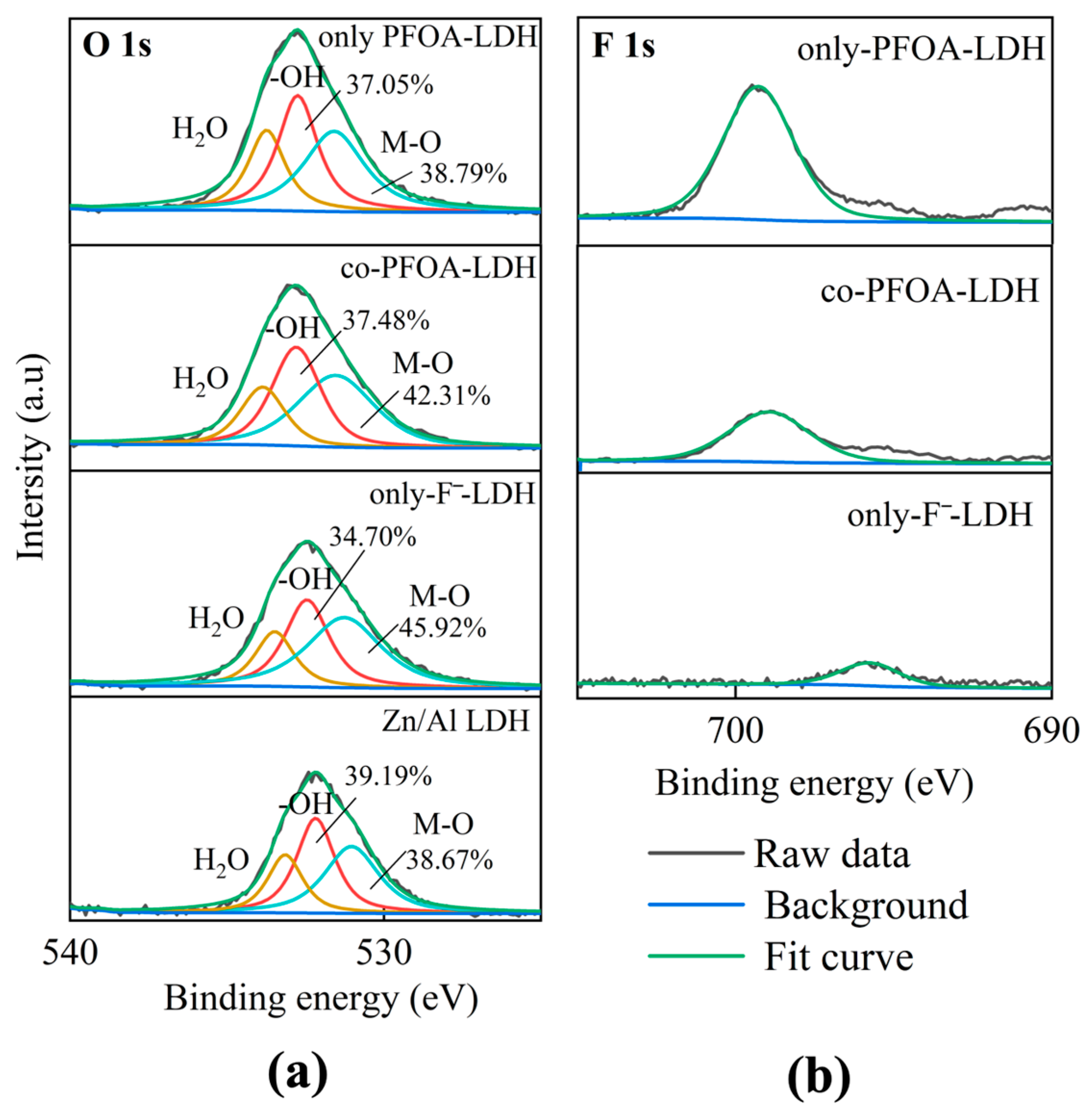

- XPS analysis

- 3.

- FTIR analysis

- 4.

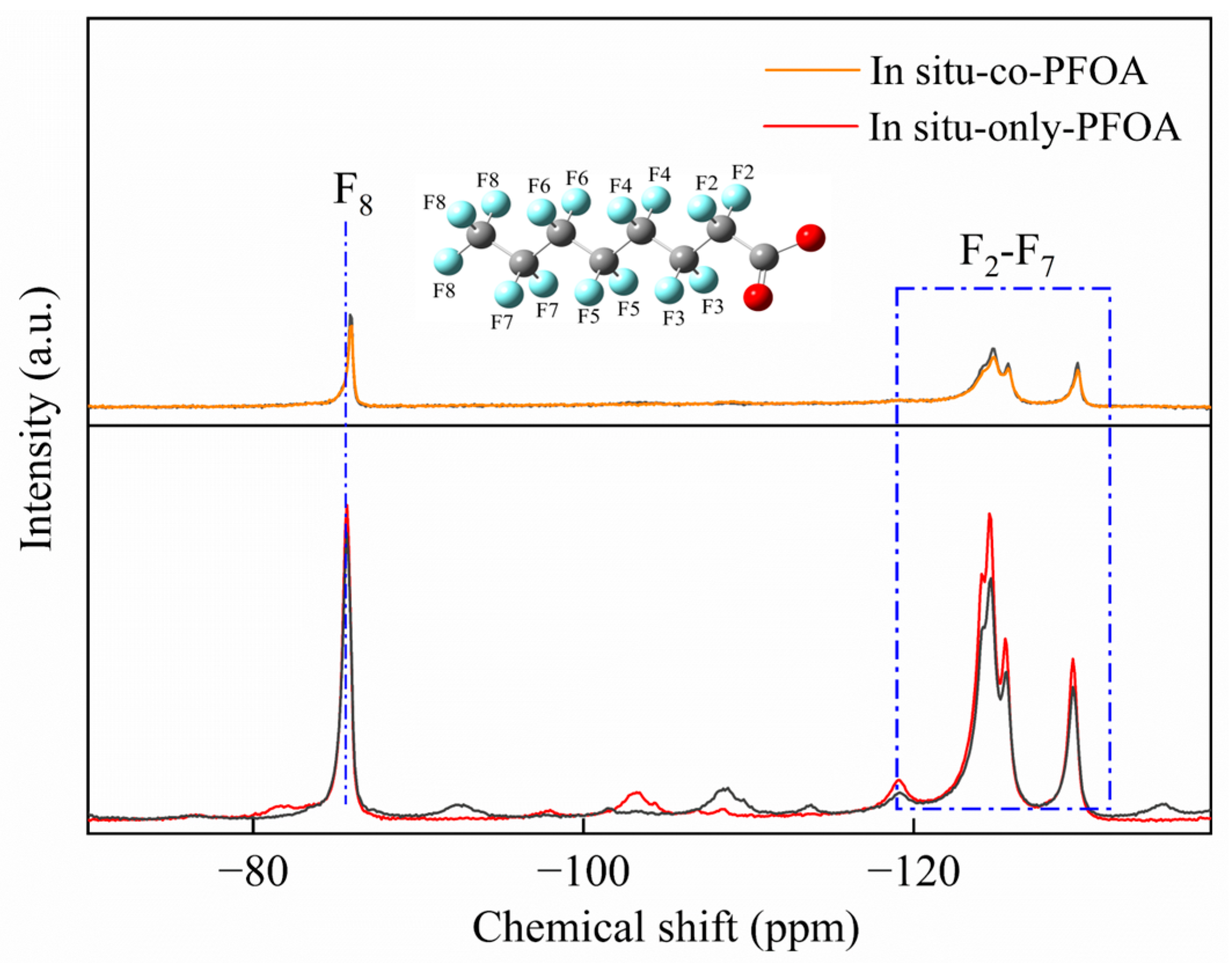

- NMR analysis

3.3. Theoretical Calculations Insight

3.3.1. Dynamic Trajectory and Radial Distribution Function (RDF) Analysis

3.3.2. Visual Study for Weak Interactions Analysis

3.3.3. Energy Decomposition for Interactions

3.4. Proposed Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PFAS | Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| PFOA | Perfluorooctanoic acid |

| PFOS | Perfluorooctane sulfonate |

| LDHs | Layered double hydroxides |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| RDF | Radial distribution function |

| MSD | Mean square displacement |

| IGMH | Independent gradient model method based on the Hirshfeld |

References

- He, Y.; Cheng, X.; Gunjal, S.J.; Zhang, C. Advancing PFAS Sorbent Design: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Perspectives. ACS Mater. Au 2024, 4, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yang, Z.; Qu, X.; Zheng, S.; Yin, D.; Fu, H. Screening and Discrimination of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Aqueous Solution Using a Luminescent Metal-Organic Framework Sensor Array. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 47706–47716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.H.; Koizumi, A. Environmental and biological monitoring of persistent fluorinated compounds in Japan and their toxicities. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2009, 14, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoner, J.R.; Kolpin, D.W.; Cozzarelli, I.M.; Smalling, K.L.; Bolyard, S.C.; Field, J.A.; Bradley, P.M. Landfill leachate contributes per-/poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and pharmaceuticals to municipal wastewater. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2020, 6, 1300–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunn, H.; Arnold, G.; Körner, W.; Rippen, G.; Steinhäuser, K.G.; Valentin, I. PFAS: Forever chemicals—Persistent, bioaccumulative and mobile. Reviewing the status and the need for their phase out and remediation of contaminated sites. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M.; Ayinla, R.T.; Elsayed, I.; Hassan, E.B. Understanding PFAS Adsorption: How Molecular Structure Affects Sustainable Water Treatment. Environments 2025, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwers, A.; Vercammen, J.; De Vos, D. Adsorption of PFAS by All-Silica Zeolite beta: Insights into the Effect of the Water Matrix, Regeneration of the Material, and Continuous PFAS Adsorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 52612–52621. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, A.; Khosropour, A.; Khazdooz, L.; Amirjalayer, S.; Khojastegi, A.; Zadehnazari, A.; Zhao, Y.; Abbaspourrad, A. Substitution and Orientation Effects on the Crystallinity and PFAS Adsorption of Olefin-Linked 2D COFs. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 9483–9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukasiewicz, E. Coagulation–Sedimentation in Water and Wastewater Treatment: Removal of Pesticides, Pharmaceuticals, PFAS, Microplastics, and Natural Organic Matter. Water 2025, 17, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, C.; Song, X.; Tang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M. Rapid and effective removal of PFOS from water using ultrathin MgAl-LDH nanosheets with defects. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 158998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Huang, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Du, Z. Selective adsorption of OBS (sodium p-perfluorous nonenoxybenzenesulfonate) as an emerging PFAS contaminant from aquatic environments by fluorinated MOFs: Novel mechanisms of F–F exclusive attraction. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Lin, Y.; Sun, Y.; Cao, H.; Fu, J.; Gao, K.; Zhang, A. In silico approach to investigating the adsorption mechanisms of short chain perfluorinated sulfonic acids and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid on hydrated hematite surface. Water Res. 2017, 114, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenka, S.P.; Kah, M.; Padhye, L.P. A review of the occurrence, transformation, and removal of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2021, 199, 117187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, J.; Min, X.; Dong, Q.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y. Comparison of Zn-Al and Mg-Al layered double hydroxides for adsorption of perfluorooctanoic acid. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, M.; Zhang, W.; Jia, Y.; Han, L.; Luo, Y. Formation processes of iron-based layered hydroxide in acid mine drainage and its implications for in-situ arsenate immobilization: Insights and mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lin, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, K.; Wu, L.; Li, S.; Liu, H. As(III) removal from wastewater and direct stabilization by in-situ formation of Zn-Fe layered double hydroxides. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Thomas, A.; Apul, O.; Venkatesan, A.K. Coexisting ions and long-chain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) inhibit the adsorption of short-chain PFAS by granular activated carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woke, J.C.; Maroli, A.S.; Zhang, Y.; Venkatesan, A.K. Impact of coexisting nitrate and sulfate ions on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances removal by anion exchange resins. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 318, 122126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zubair, Y.O.; Pan, S.; Tokoro, C. Mechanism of boron removal and stabilization by in-situ formation of layered double hydroxides: Insight from spectroscopy and DFT studies. J. Environ. Sci. 2026, 160, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Yan, X.; Qi, Y.; Wang, L.; Tu, H.; Jiang, H.; Xu, Y. Assessing Fluoride Contamination in Groundwater of Informal Landfills in the Yangtze River Delta: Implications for Environmental Security and Sustainable Resource Management. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2025, 236, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.M.; Barofsky, D.F.; Field, J.A. Quantitative Determination of Fluorotelomer Sulfonates in Groundwater by LC MS/MS. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 36, 1828–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Wang, M.; Chuang, Y.; Chiang, P. Arsenate adsorption by Mg/Al–NO3 layered double hydroxides with varying the Mg/Al ratio. Appl. Clay Sci. 2009, 43, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Sanchez, G.; Galvao, T.L.; Tedim, J.; Gomes, J.R. A molecular dynamics framework to explore the structure and dynamics of layered double hydroxides. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 163, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, C.M.; Schutt, T.C.; Shukla, M.K. Properties and Mechanisms for PFAS Adsorption to Aqueous Clay and Humic Soil Components. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 10053–10061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Wei, M.; Ma, J.; Li, F.; Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Theoretical Study on the Structural Properties and Relative Stability of M(II)-Al Layered Double Hydroxides Based on a Cluster Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 6133–6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Dong, W.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, L. Elucidating the Photo-Induced Electronic Structure and Mechanisms of ZnAl-Layered Double Hydroxide: A DFT Study. Chem. Asian J. 2025, 20, e202401154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goerigk, L.; Grimme, S. Efficient and Accurate Double-Hybrid-Meta-GGA Density Functionals-Evaluation with the Extended GMTKN30 Database for General Main Group Thermochemistry, Kinetics, and Noncovalent Interactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, R.B.J.S.; Binkley, J.S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Harvey, A.J.; Sen, A.; Dessent, C.E. Performance of M06, M06-2X, and M06-HF density functionals for conformationally flexible anionic clusters: M06 functionals perform better than B3LYP for a model system with dispersion and ionic hydrogen-bonding interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 12590–12600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Furche, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Gaussian basis sets of quadruple zeta valence quality for atoms H–Kr. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 12753–12762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.J.; Wadt, W.R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for the transition metal atoms Sc to Hg. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokoro, C.; Sakakibara, T.; Suzuki, S. Mechanism investigation and surface complexation modeling of zinc sorption on aluminum hydroxide in adsorption/coprecipitation processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 279, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokoro, C.; Suzuki, S.; Haraguchi, D.; Izawa, S. Silicate Removal in Aluminum Hydroxide Co-Precipitation Process. Materials 2014, 7, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, S.; Gürses, A.; Açıkyıldız, M.; Ejder, M. Adsorption of cationic dye from aqueous solutions by activated carbon. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 115, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, S.; Fuchida, S.; Tokoro, C. Coprecipitation mechanisms of Zn by birnessite formation and its mineralogy under neutral pH conditions. J. Environ. Sci. 2022, 121, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Morita, M.; Matsuoka, M.; Tokoro, C. Sorption mechanisms of chromate with coprecipitated ferrihydrite in aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 334, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.H.C.d.; Marques Fraga, D.M.d.S.; da Silva, M.P.; Fraga, T.J.M.; Carvalho, M.N.; de Luna Freire, E.M.P.; Ghislandi, M.G.; da Motta Sobrinho, M.A. Removal of toxic dyes from aqueous solution by adsorption onto highly recyclable xGnP® graphite nanoplatelets. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zeng, Y.; Cheng, Y.; He, D.; Pan, X. Recent advances in municipal landfill leachate: A review focusing on its characteristics, treatment, and toxicity assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 135468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Deng, S.; Bei, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Yu, G. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of perfluorinated compounds on various adsorbents—A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 274, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, X.; Trujillo, D.; Huo, J.; Dong, Q.; Wang, Y. Amine-bridged periodic mesoporous organosilica nanomaterial for efficient removal of selenate. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 396, 125278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, B.; Yan, Y.; Huang, R.; Abdala, D.B.; Liu, F.; Tang, Y.; Tan, W.; Feng, X. Formation of Zn-Al layered double hydroxides (LDH) during the interaction of ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) with gamma-Al2O3. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1980–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Chen, Q.; Lin, Y.; Zu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Feng, T.; Liao, X. New insights into removal efficacy of perfluoroalkyl substances by layered double hydroxide and its composite materials. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2024, 19, 100636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Dong, Z.; Sun, D.; Wu, T.; Li, Y. Enhanced adsorption capacity of dyes by surfactant-modified layered double hydroxides from aqueous solution. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 49, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Georgi, A.; Zhang, W.; Kopinke, F.D.; Yan, J.; Saeidi, N.; Li, J.; Gu, M.; Chen, M. Mechanistic insights into fast adsorption of perfluoroalkyl substances on carbonate-layered double hydroxides. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 408, 124815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Narducci, R.; Varone, A.; Kaciulis, S.; Bolli, E.; Pizzoferrato, R. Zn–Al Layered Double Hydroxides Synthesized on Aluminum Foams for Fluoride Removal from Water. Processes 2021, 9, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, B. Enhanced fluoride removal by La-doped Li/Al layered double hydroxides. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2018, 509, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Chen, J.; Che, H.; Ao, Y.; Wang, P. Surface Complex and Nonradical Pathways Contributing to High-Efficiency Degradation of Perfluorooctanoic Acid on Oxygen-Deficient In2O3 Derived from an In-Based Metal Organic Framework. ACS EST Water 2022, 2, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Zhang, P.; Jin, L.; Li, Z. Photocatalytic decomposition of perfluorooctanoic acid in pure water and sewage water by nanostructured gallium oxide. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 142–143, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Jiang, Z.; Ding, W.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y. Multiple interactions steered high affinity toward PFAS on ultrathin layered rare-earth hydroxide nanosheets: Remediation performance and molecular-level insights. Water Res. 2023, 230, 119558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Chowdhury, T.; Rabin, M.H.; Islam, R.; Xiao, K. Sorption of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) using Polyethylene (PE) microplastics as adsorbent: Grand Canonical Monte Carlo and Molecular Dynamics (GCMC-MD) studies. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2022, 104, 2719–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaher, A.; Taha, M.; Mahmoud, R.K. Possible adsorption mechanisms of the removal of tetracycline from water by La-doped Zn-Fe-layered double hydroxide. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 322, 114546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, B.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Shao, X.; Cai, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Ion Adsorption and Ligand Exchange on an Orthoclase Surface. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 14952–14962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, Q. Independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition: A new method for visual study of interactions in chemical systems. J. Comput. Chem. 2022, 43, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, K.; Hao, M.; Geng, M.; Shi, B.; Hu, C. Comparison of perfluoroalkyl substance adsorption performance by inorganic and organic silicon modified activated carbon. Water Res. 2024, 260, 121919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Khan, M.A.; Wang, F.; Bano, Z.; Xia, M. Rapid removal of toxic metals Cu2+ and Pb2+ by amino trimethylene phosphonic acid intercalated layered double hydroxide: A combined experimental and DFT study. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 392, 123711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, X.; Chen, J.; Shi, G.; Liu, X. Enhancement of gas adsorption on transition metal ion-modified graphene using DFT calculations. J. Mol. Model. 2024, 30, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, A.V.; Kamath, P.V.; Shivakumara, C. Conservation of Order, Disorder, and “Crystallinity” during Anion-Exchange Reactions among Layered Double Hydroxides (LDHs) of Zn with Al. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 3411–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System | Diffusion Coefficients |

|---|---|

| co-PFOA system | 1.059 × 10−6 |

| only-PFOA system | 1.349 × 10−6 |

| System | ΔEint | ΔEels | ΔEx | ΔErep | ΔEorb | ΔEDFTC | ΔEdc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFOA adsorbed on LDH | −214.85 | −213.45 | −28.16 | 104.46 | −38.60 | −19.79 | −19.31 |

| F− adsorbed on LDH | −250.41 | −268.64 | −50.29 | 141.79 | −57.48 | −12.83 | −2.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Zubair, Y.O.; Tokoro, C. Investigation of In Situ Strategy Based on Zn/Al-Layered Double Hydroxides for Enhanced PFOA Removal: Adsorption Mechanism and Fluoride Effect. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13064. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413064

Wang Y, Zubair YO, Tokoro C. Investigation of In Situ Strategy Based on Zn/Al-Layered Double Hydroxides for Enhanced PFOA Removal: Adsorption Mechanism and Fluoride Effect. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13064. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413064

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yafan, Yusuf Olalekan Zubair, and Chiharu Tokoro. 2025. "Investigation of In Situ Strategy Based on Zn/Al-Layered Double Hydroxides for Enhanced PFOA Removal: Adsorption Mechanism and Fluoride Effect" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13064. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413064

APA StyleWang, Y., Zubair, Y. O., & Tokoro, C. (2025). Investigation of In Situ Strategy Based on Zn/Al-Layered Double Hydroxides for Enhanced PFOA Removal: Adsorption Mechanism and Fluoride Effect. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13064. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413064