Lightweight YOLO-SR: A Method for Small Object Detection in UAV Aerial Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

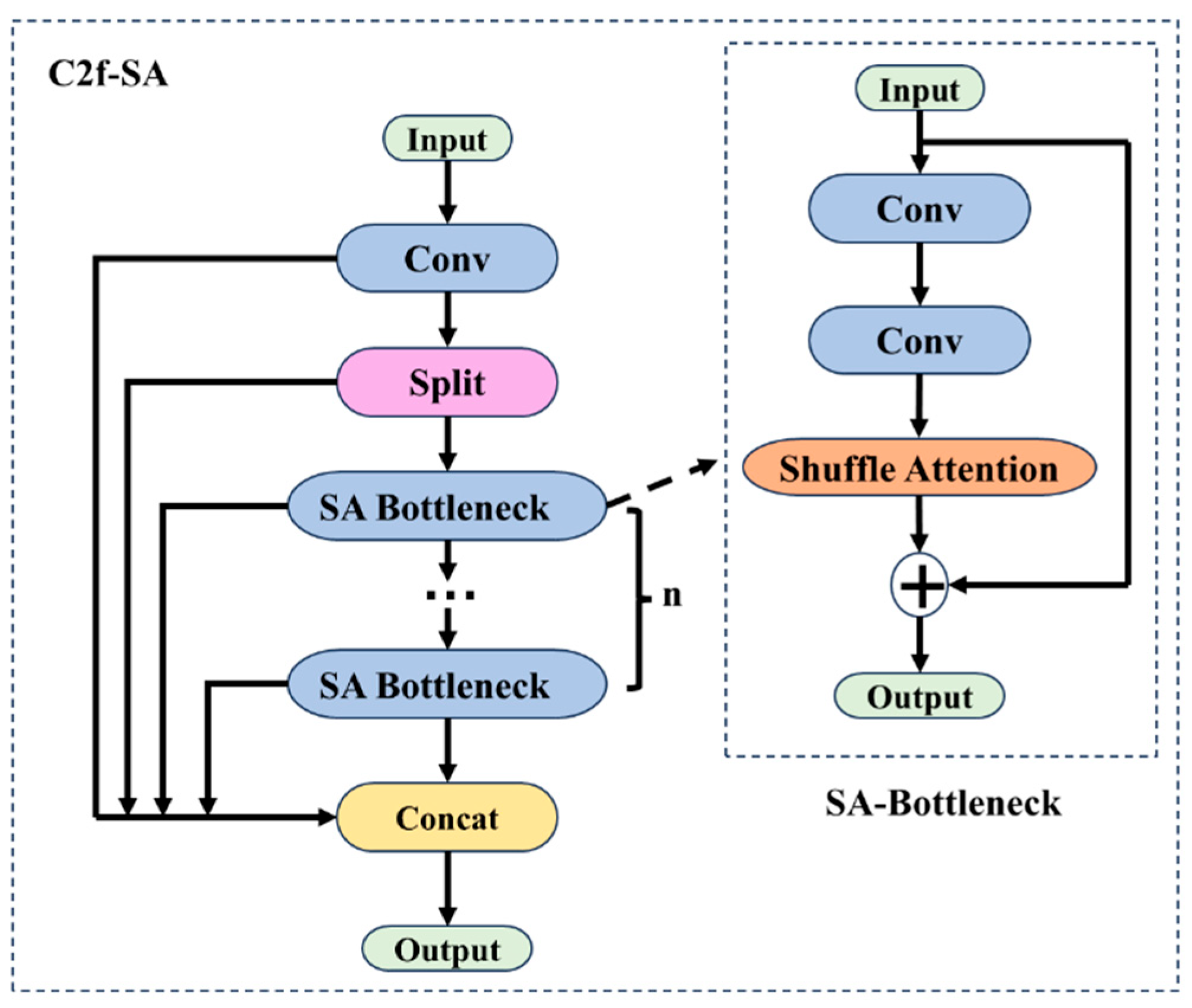

- Designed the lightweight feature extraction module C2f-SA: By integrating separable convolutions with the Shuffle Attention mechanism, it reduces redundant operations after the first downsampling, preserves high-frequency details of small objects, and enhances fine-grained feature extraction capabilities. This module effectively reduces parameter count, computational load, and memory overhead while maintaining feature expressiveness, thereby improving detection accuracy and inference efficiency.

- (2)

- Designed the Small Object Detection-Specific Module SPPF-CBAM: Building upon spatial pyramid pooling (SPPF), it captures global contextual information through multi-scale pooling. By integrating a dual channel–spatial attention mechanism, it adaptively suppresses noise while amplifying key information, mitigating information dilution during cross-scale feature integration. Embedded within the YOLOv5 backbone network, this module enhances small object feature representation and detection performance while maintaining lightweight architecture.

- (3)

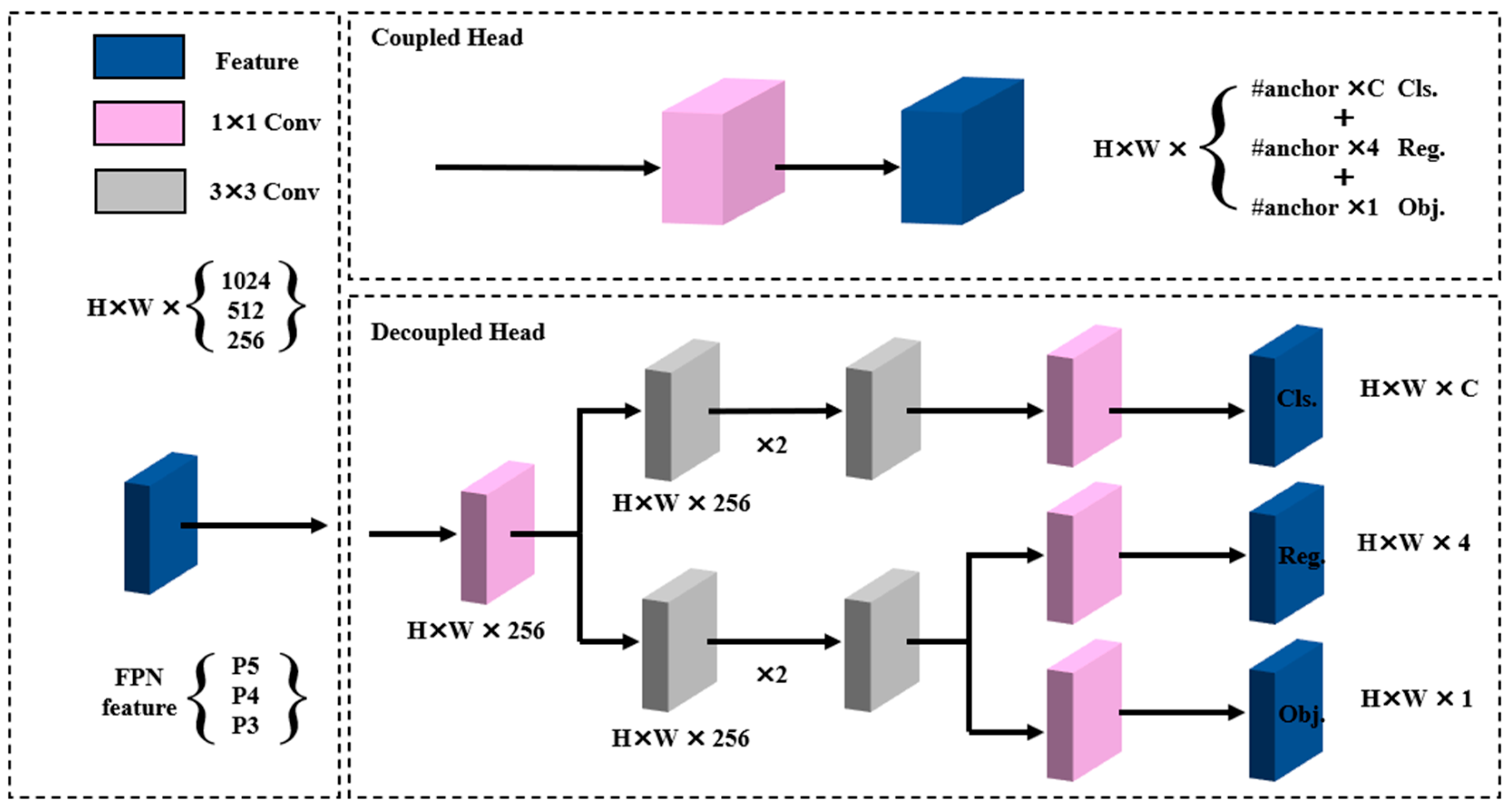

- Introduced the Decoupled Detect decoupled detection head: By separating tasks and implementing dynamic loss optimization, it mitigates conflicts between classification and regression tasks, improving classification confidence and localization accuracy for small object detection in drone scenarios.

2. Related Work

2.1. Small Object Detection

2.2. Limitations of Existing Approaches

3. Methodology

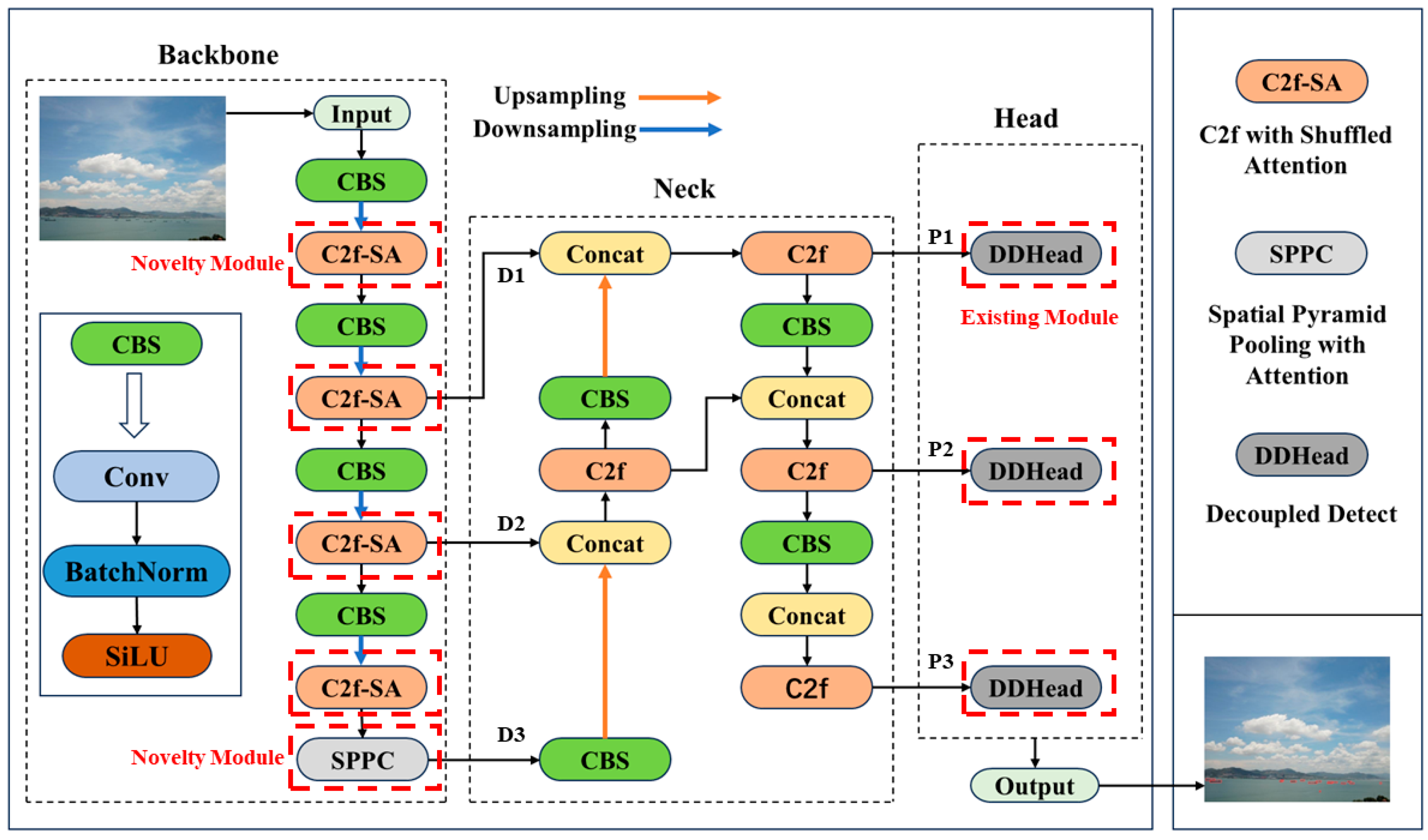

3.1. Network Architecture Design

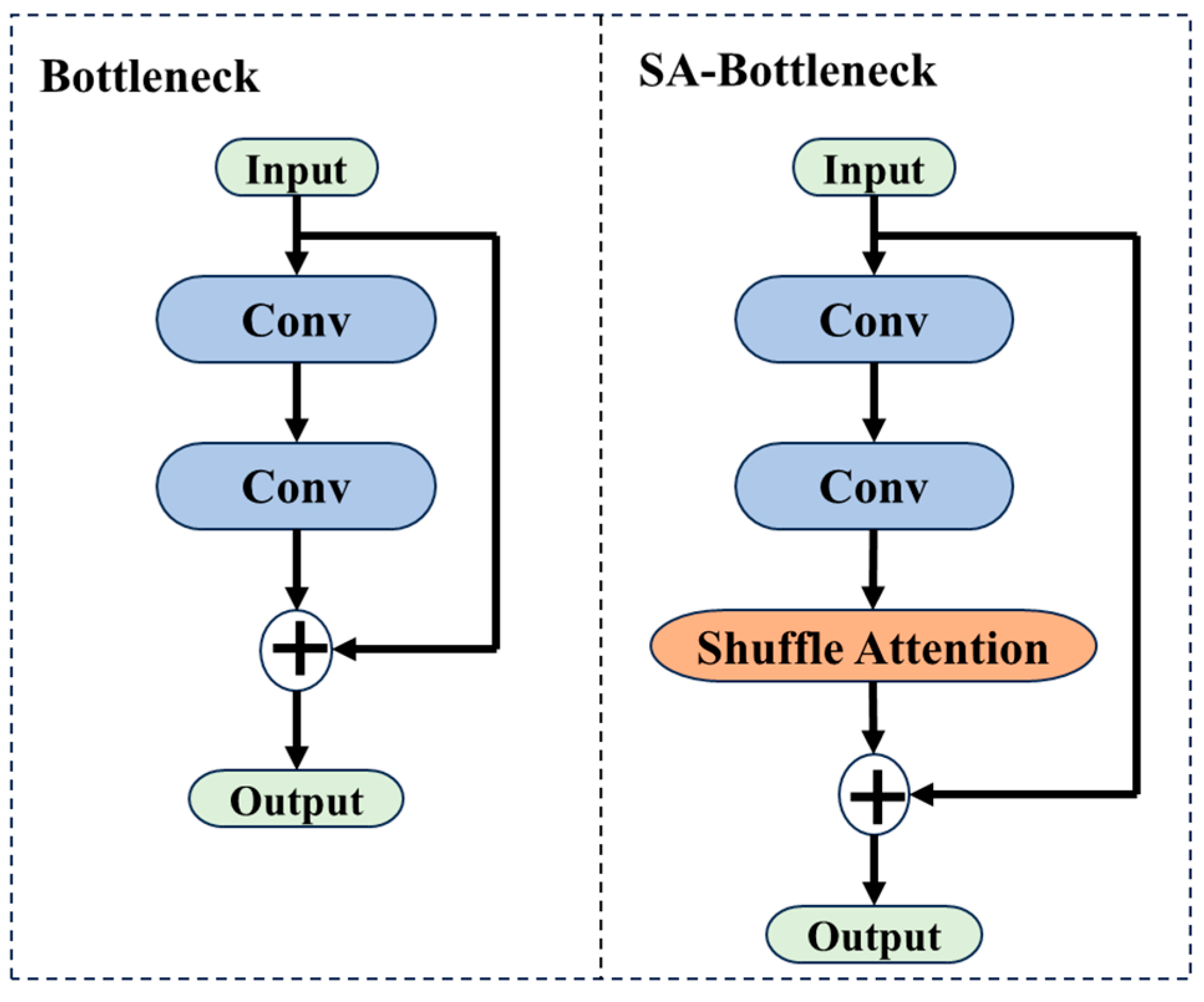

3.2. Lightweight Backbone Network Based on C2f-SA

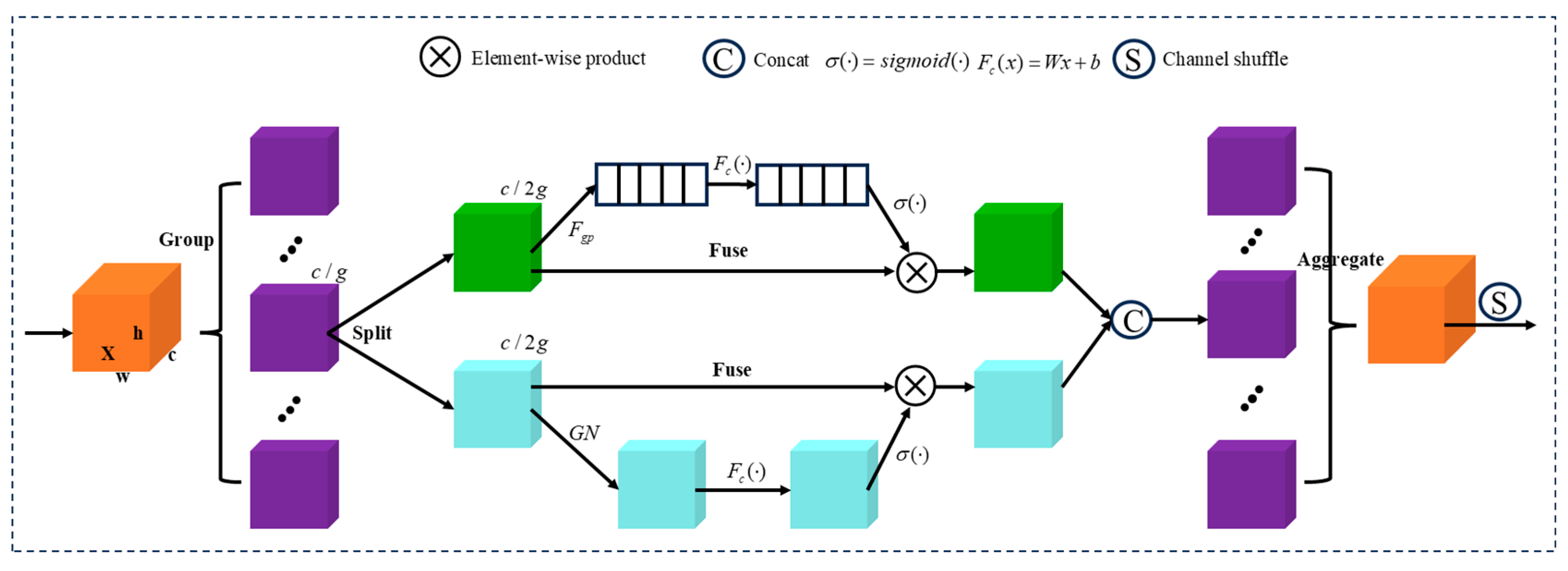

3.2.1. Shuffle Attention (SA) Mechanism

3.2.2. C2f-SA Module Design

3.3. Spatial Pyramid Pooling Attention Module SPPC (SPPF-CBAM)

3.3.1. CBAM Attention Mechanism

3.3.2. SPPF-CBAM Module Design

3.4. Decoupled Detection Head

4. Results and Analysis

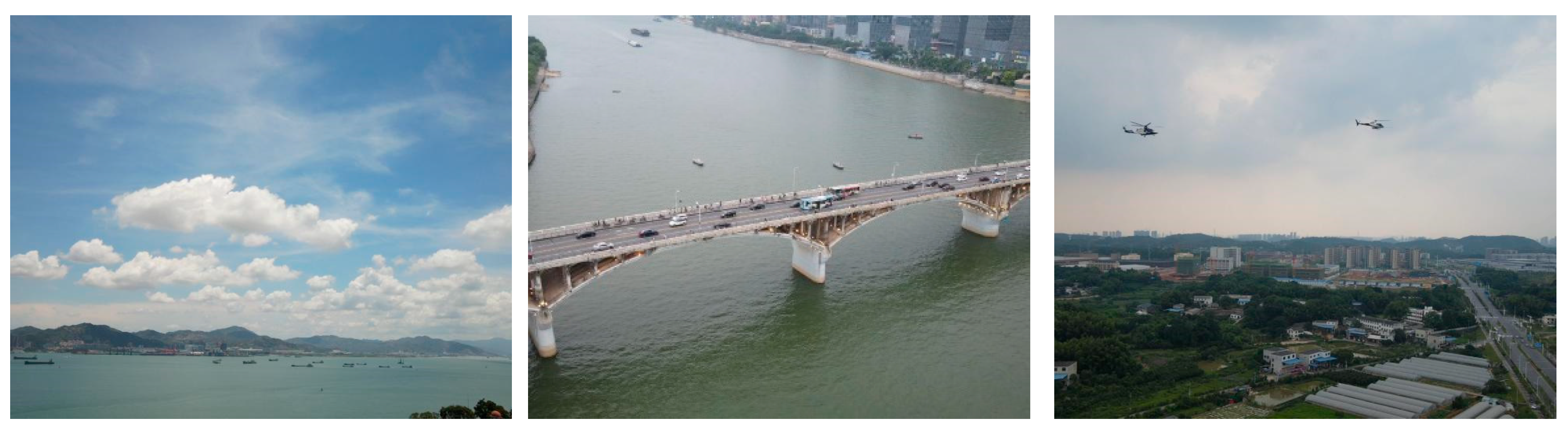

4.1. Experimental Datasets

4.1.1. RGBT-Tiny Dataset

4.1.2. VisDrone2019 Dataset

4.2. Environment and Parameter Settings

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

- Precision represents the reliability of a model’s prediction as a positive sample. The calculation formula is as follows:where TP (true positive) is the number of correctly detected positive samples, and FP (false positive) is the number of incorrectly detected samples.

- Recall reflects the model’s ability to cover true positive samples. The calculation formula is as follows:FN (false negative) represents the number of true positive samples that were missed.

- F1-Score: As a core metric for comprehensively evaluating a model’s detection precision and coverage capability, F1-Score represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall. Its definition is based on the statistics of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) in object detection tasks:The F1-Score is in the range of [0, 1], with values closer to 1 indicating superior overall performance in both “accurate target identification” and “comprehensive target coverage.” This metric is particularly well-suited for datasets with a high proportion of small targets, as in this study, effectively reflecting the model’s balanced detection capability for small objects.

- Mean average precision (mAP): To comprehensively evaluate model robustness, this study calculates the average precision at IoU (intersection over union) thresholds of 0.5 and 0.75, denoted as mAP0.5 and mAP0.75, respectively. The final model performance is characterized by the global mean average precision across categories (mAP), and its calculation method is as follows:where N is the total number of categories and is the average precision of the i-th category. The mAP value is in the range of [0, 1], and a higher value indicates better overall detection performance of the model.

- Intersection over union (IOU): The intersection over union is used to measure the degree of overlap between predicted boxes and ground truth boxes. Its mathematical expression is as follows:

- Model parameters (Params): The total number of all trainable weight parameters in the model, which directly determines the model’s complexity and hardware resource requirements.

- Floating point operations (GFLOPs) measure the number of billions of floating point operations executed per second by the model, representing the computational complexity of the model.

- Frames per second (FPS) represents the number of image frames processed per second by the model, used to evaluate the real-time performance of the model.

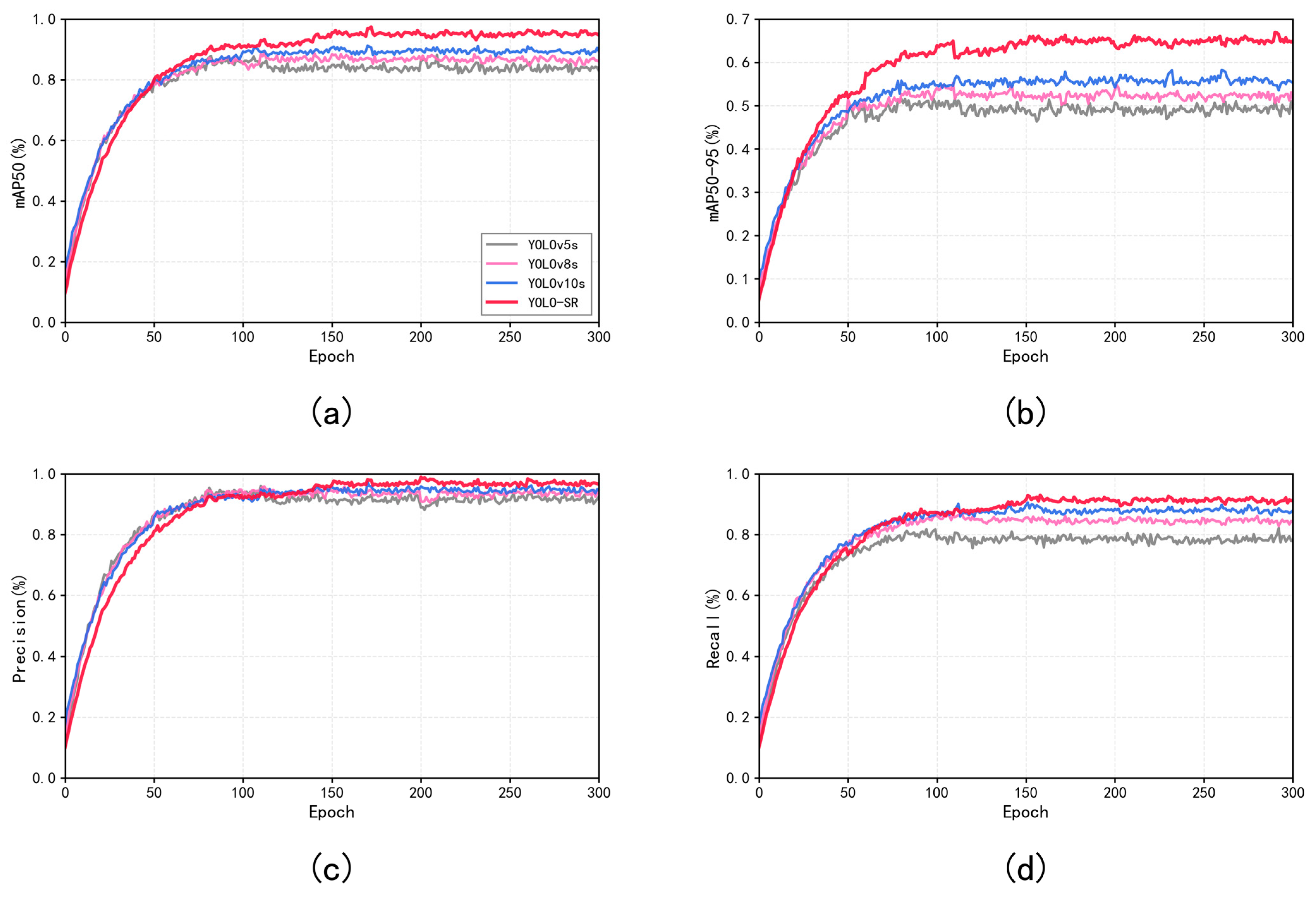

4.4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.4.1. Comparative Experiments

4.4.2. Ablation Studies

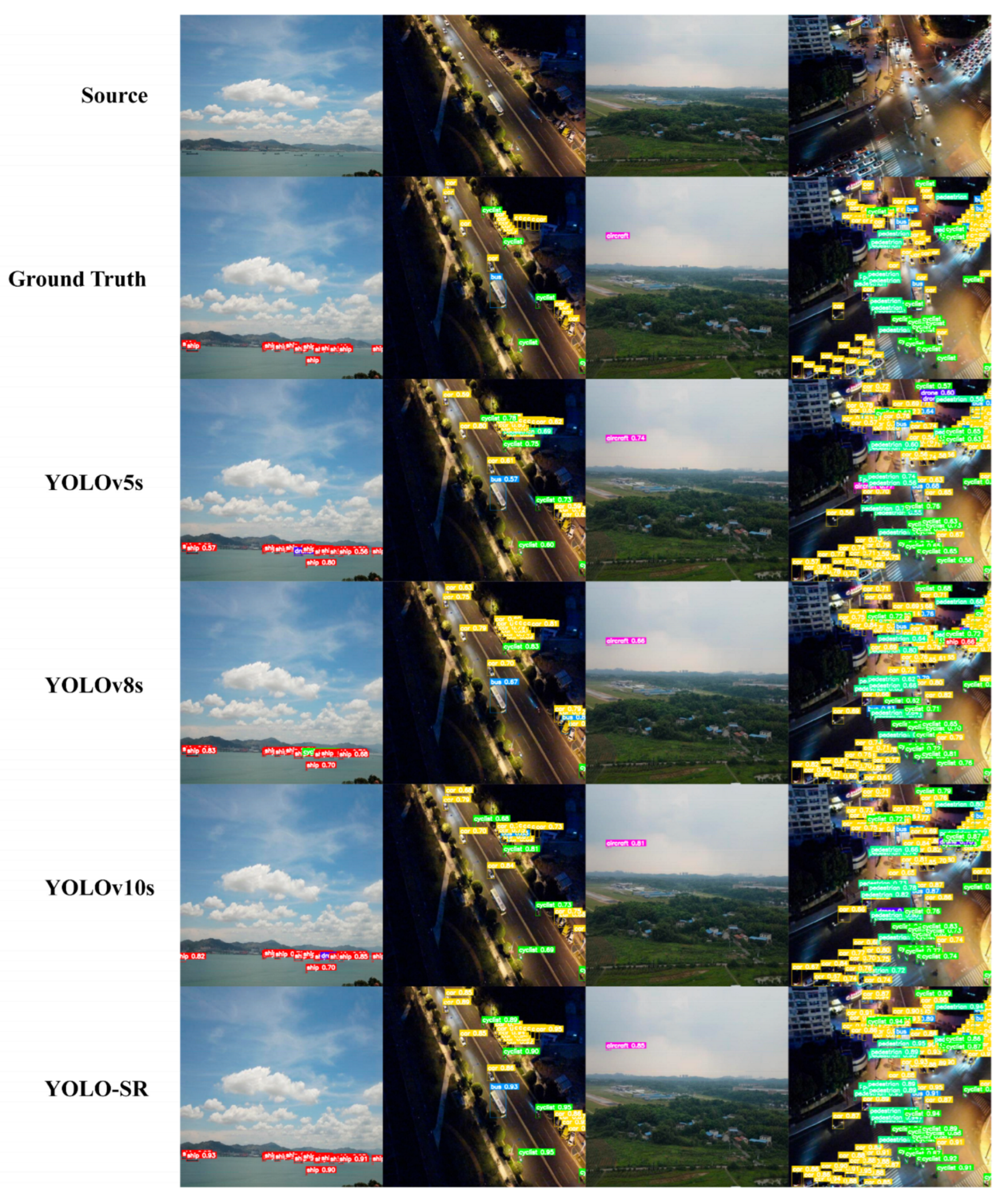

4.4.3. Visualization Analysis of Experimental Results

4.5. Analysis of Model Limitations and Future Directions for Improvement

- (1)

- Limited detection capability for extremely small targets. For targets smaller than 8 × 8 pixels, the model exhibits some false negatives. The primary reasons are as follows: after multiple downsampling iterations, the effective pixel information for extremely small targets becomes extremely sparse in deep feature maps, making it difficult to form discriminative feature representations; the C2f-SA and SPPF-CBAM modules have limited effectiveness in enhancing features for even smaller-scale targets.

- (2)

- Object discrimination capability in densely occluded scenes requires improvement. When multiple small objects are highly spatially overlapped or partially occluded, the model still struggles to precisely distinguish adjacent object boundaries, occasionally resulting in overlapping bounding boxes. The primary reasons are as follows: overlapping receptive fields on feature maps make it difficult for the model to accurately distinguish independent boundaries of different objects and the current multi-scale feature fusion strategy lacks explicit modeling mechanisms for the interrelationships among densely packed objects.

- (3)

- Cross-domain generalization capabilities require strengthening. Performance degrades to some extent when transferred to other drone aerial datasets. (The mAP@0.5 decreases by approximately 3–5 percentage points.) Key reasons include model design primarily optimizing for the distribution characteristics of specific datasets, potentially overfitting to training data patterns; insufficient consideration of domain-to-domain variations across different aerial scenarios; and lack of domain adaptation mechanisms.

- (4)

- Further optimization is needed to balance real-time performance and accuracy. Deployment on resource-constrained edge devices further reduces inference speed. Key reasons include the following: the self-attention mechanism in the C2f-SA module incurs significantly higher computational overhead at higher input resolutions; the multi-scale pooling operations in the SPPF-CBAM module increase computational burden; and the dual-branch structure of the decoupled detection head adds approximately 15-20% computational overhead compared to a single-branch design.

- (1)

- For ultra-small object detection, we will explore progressive feature enhancement strategies based on feature super-resolution, combined with knowledge distillation techniques, to enhance the model’s perception of pixel-level small targets.

- (2)

- For densely occluded scenes, we will introduce a target relationship modeling mechanism based on Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to explicitly model spatial relationships and occlusion between densely packed targets, improving the model’s object separation capability in complex scenarios.

- (3)

- For cross-domain generalization challenges, we will design domain-adaptive training strategies. By incorporating adversarial training mechanisms or domain-adversarial loss functions, the model will learn domain-invariant feature representations. Concurrently, we will explore fast adaptation methods based on meta-learning.

- (4)

- To balance real-time performance and accuracy, we will investigate model pruning and quantization techniques. Research will focus on automated lightweight design methods using neural architecture search (NAS) to achieve a better equilibrium between precision and efficiency.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles based low-altitude economy with lifecycle techno-economic-environmental analysis for Sustainable and Smart Cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 499, 145050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wandelt, S. LAERACE: Taking the policy fast-track towards low-altitude economy. J. Air Transp. Res. Soc. 2025, 4, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Development Path of Low-Altitude Logistics and Construction of Industry-Education Integration Community from the Perspective of New Quality Productive Forces. Ind. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.; Shin, I.K.; Moon, J.; Kang, J.; Choi, S.I. Road traffic monitoring from UAV images using deep learning networks. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić-Štulić, D.; Marušić, Ž.; Gotovac, S. Deep learning approach in aerial imagery for supporting land search and rescue missions. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2019, 127, 1256–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElTantawy, A.; Shehata, M.S. Local null space pursuit for real-time moving object detection in aerial surveillance. Signal Image Video Process. 2020, 14, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, A.; Khemmar, R.; Decoux, B.; Ragot, N.; Rossi, R.; Trabelsi, R.; Boutteau, R.; Ertaud, J.-Y.; Savatier, X. Deep learning for real-time 3D multi-object detection, localisation, and tracking: Application to smart mobility. Sensors 2020, 20, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Deng, Z.; Huang, X. A novel detector for range-spread target detection based on HRRP-pursuing. Measurement 2024, 231, 114579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, K.S.; Chadaga, M.G.; Savalgimath, S.S.; Rakshith, G.R.; Kumar, M.N. Evaluation and evolution of object detection techniques YOLO and R-CNN. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. IJRTE 2019, 8, 2S3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, T.; Guo, S.; Feng, S.; Yao, W.; Lan, Y. Yolo-based uav technology: A review of the research and its applications. Drones 2023, 7, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.H.; Kim, S.Y. Real-time object detection and segmentation technology: An analysis of the YOLO algorithm. JMST Adv. 2023, 5, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ma, H. Improving the Vehicle Small Object Detection Algorithm of Yolov5. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Innov. 2025, 15, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Xue, W.; Yue, G.; Wang, S. Research on YOLOX for small target detection in infrared aerial photography based on NAM channel attention mechanism. In Proceedings of the Conference on Infrared, Millimeter, Terahertz Waves and Applications (IMT2022), Shanghai, China, 8–10 November 2023; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2023; Volume 12565, pp. 983–992. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, G.; Liao, G.; Zhu, H.; Sun, B. Multibranch attention mechanism based on channel and spatial attention fusion. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Han, J. Real-Time object detector based MobileNetV3 for UAV applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 18709–18725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Hu, C.; Hao, J.; Ge, P.; Han, B. Target Detection in Single-Photon Lidar Using CNN Based on Point Cloud Method. Photonics 2024, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Qiu, Z.; Li, P.; Hong, Y. RMAU-Net: Breast Tumor Segmentation Network Based on Residual Depthwise Separable Convolution and Multiscale Channel Attention Gates. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, K.; Li, Q.; Zhu, C. Non-technical losses detection using missing values’ pattern and neural architecture search. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 134, 107410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, T. Multi-scale residual aggregation feature pyramid network for object detection. Electronics 2022, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, Q.; Zhao, H.; Yang, W. Doublem-net: Multi-scale spatial pyramid pooling-fast and multi-path adaptive feature pyramid network for UAV detection. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2024, 12, 5781–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Feng, X. Multi-object pedestrian tracking using improved YOLOv8 and OC-SORT. Sensors 2023, 23, 8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z. Vehicle Target Detection Using the Improved YOLOv5s Algorithm. Electronics 2024, 13, 4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowthami, N.; Blessy, S.V. Extreme small-scale prediction head-based efficient YOLOV5 for small-scale object detection. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 025007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Luo, S.; He, C.; Xiao, H.; Wu, H. Underwater small and occlusion object detection with feature fusion and global context decoupling head-based yolo. Multimed. Syst. 2024, 30, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.01497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; Wang, Q.; Feng, W.; Wang, T.; Tong, C. An SAR imaging and detection model of multiple maritime targets based on the electromagnetic approach and the modified CBAM-YOLOv7 neural network. Electronics 2023, 12, 4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, X.; Xiao, C.; Li, R.; He, X.; Li, B.; Li, Z.; Li, M.; Zhao, S.; Liu, L.; Sheng, W. Visible-thermal tiny object detection: A benchmark dataset and baselines. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.14482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Nian, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, F. Lightweight multimechanism deep feature enhancement network for infrared small-target detection. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, S.; Zhang, R.; Yu, P.; Fu, Z.; Wang, X.; Kadoch, M.; Yang, Y. Detection of floating objects on water surface using YOLOv5s in an edge computing environment. Water 2023, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xu, Y.; Hou, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, X. ARU-GAN: U-shaped GAN based on Attention and Residual connection for super-resolution reconstruction. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 164, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J. MHDNet: A Multi-Scale Hybrid Deep Learning Model for Person Re-Identification. Electronics 2024, 13, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Li, T.; Liu, Q.; He, Z. PANet: Pluralistic Attention Network for Few-Shot Image Classification. Neural Process. Lett. 2024, 56, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, Z. BA-YOLO for Object Detection in Satellite Remote Sensing Images. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zang, B.; Song, C.; Li, B.; Lang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huo, P. Small object detection in remote sensing images based on redundant feature removal and progressive regression. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ding, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Bao, L. TRC-YOLO: A real-time detection method for lightweight targets based on mobile devices. IET Comput. Vis. 2023, 16, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Najibi, M.; Sharma, A.; Davis, L.S. Scale normalized image pyramids with autofocus for object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 3749–3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Huang, T. Fast Image Pyramid Construction Using Adaptive Sparse Sampling; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 9, pp. 123456–123467. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Kong, W.; Shen, J.; Shao, Y. CSA-Net: Cross-modal scale-aware attention-aggregated network for RGB-T crowd counting. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 119038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Y. YOLOv7-RAR for urban vehicle detection. Sensors 2023, 23, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Xia, R.; Yang, K.; Zou, K. GCAM: Lightweight image inpainting via group convolution and attention mechanism. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2024, 15, 1815–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Xu, F.; Guo, H. Side-Scan Sonar Image Detection of Shipwrecks Based on CSC-YOLO Algorithm. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 82, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zong, M.; Zhu, J. Improved YOLOv3 integrating SENet and optimized GIoU loss for occluded pedestrian detection. Sensors 2023, 23, 9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Zhu, P.; Wen, L.; Bian, X.; Lin, H.; Hu, Q.; Peng, T.; Zheng, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; et al. VisDrone-DET2019: The vision meets drone object detection in image challenge results. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops 2019, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Proceedings, Part I 14. Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Scott, M.R.; Huang, W. Tood: Task-aligned one-stage object detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; IEEE Computer Society: Piscataway, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3490–3499. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Chi, C.; Yao, Y.; Lei, Z.; Li, S.Z. Bridging the gap between anchor-based and anchor-free detection via adaptive training sample selection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 9759–9768. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Vasconcelos, N. Cascade r-cnn: Delving into high quality object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 19–21 June 2018; pp. 6154–6162. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Chang, H.; Ma, B.; Wang, N.; Chen, X. Dynamic R-CNN: Towards high quality object detection via dynamic training. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part XV 16. Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 260–275. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Cao, Y.; Chen, K.; Pang, J.; Gong, T.; Loy, C.; Lin, D. Side-aware boundary localization for more precise object detection. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part IV 16. Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 403–419. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, D.; Krähenbühl, P. Objects as points. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.07850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. Fcos: Fully convolutional one-stage object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9627–9636. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Dayoub, F.; Sunderhauf, N. Varifocalnet: An iou-aware dense object detector. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 8514–8523. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable detr: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Kong, T.; Xu, C.; Zhan, W.; Tomizuka, M.; Li, L.; Tuan, Z.; Wang, C.; et al. Sparse r-cnn: End-to-end object detection with learnable proposals. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 14454–14463. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Xiao, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, M.; An, W.; Guo, Y. Dense nested attention network for infrared small target detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 32, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Yu, H.; Yu, L.; Xia, G.S. RFLA: Gaussian receptive field based label assignment for tiny object detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Visio, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 526–543. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Park, S.; Song, H.; Ryu, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Pereira, S.; Yoo, D. Interactive multi-class tiny-object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 14136–14145. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Dai, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, F.; Liu, Y. Efficient underwater object detection with enhanced feature extraction and fusion. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 4904–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Geng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, C.; Li, C.; Lian, Z.; Zhou, X. Ace-sniper: Cloud–edge collaborative scheduling framework with DNN inference latency modeling on heterogeneous devices. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2024, 43, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Hirata, K. Comparison with detection of bacteria from gram stained smears images by various object detectors. In Proceedings of the2024 16th IIAI International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics, Takamatsu, Japan, 6–12 July 2024; pp. 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Yang, X.; Zhu, H.; Wang, X.; Hou, B.; Ma, M.; Wu, Y. Dense-weak ship detection based on foreground-guided background generation network in SAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5212616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Tan, J.; Wu, L.; Chang, L.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Z. A fruit and vegetable recognition method based on augmsr-cnn. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Machine Vision and Intelligent Algorithms (PRMVIA), Changsha, China, 24–27 May 2024; pp. 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, S.; Han, Y.; Zhao, B.; Luo, S. Enhanced aircraft detection in compressed remote sensing images using cmsff-yolov8. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5650116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yao, G.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, H.; Kong, J. SOD-YOLOv10: Small object detection in remote sensing images based on YOLOv10. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Module Type | Parameters (M) | Computational Load (GFLOPs) | Inference Speed (FPS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C3 Module | 2.1 | 8.5 | 45 |

| C2f-SA Module | 1.6 | 6.2 | 58 |

| Improvement | −23.8% | −27.1% | +28.9% |

| Param (M) | mAP0.5 (%) | mAP0.75 (%) | mAP0.5:0.95 (%) | GFLOPs | FPS@640 | FPS@1280 | F1-Score (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSD | 25.2 | 43.1 | 31.9 | 28 | 95 | 78.5 | 22.1 | 61.7 |

| TOOD | 31.8 | 37.7 | 31.7 | 27.9 | 105 | 72.3 | 20.3 | 55.3 |

| ATSS [46] | 31.9 | 43.5 | 26.8 | 24.2 | 100 | 75.2 | 21.2 | 65.0 |

| RetinaNet [47] | 36.2 | 37.4 | 22.9 | 21.8 | 100 | 73.8 | 20.8 | 58.6 |

| Faster RCNN | 41.2 | 43.1 | 33.5 | 28.8 | 85 | 22.1 | 6.1 | 68.1 |

| Cascade RCNN [48] | 68.9 | 44.2 | 35.8 | 30.1 | 280 | 8.0 | 2.2 | 69.7 |

| Dynamic RCNN [49] | 41.2 | 44 | 34.2 | 29.4 | 90 | 20.7 | 5.8 | 68.2 |

| SABL [50] | 41.9 | 43.3 | 35.3 | 29.6 | 120 | 65.8 | 18.5 | 70.6 |

| CenterNet [51] | 14.4 | 31.7 | 18.2 | 17.8 | 80 | 82.5 | 23.2 | 57.2 |

| FCOS [52] | 31.9 | 28.6 | 19.2 | 17.5 | 90 | 68.5 | 19.3 | 53.6 |

| VarifocalNet [53] | 32.5 | 41.6 | 30.1 | 26.9 | 95 | 76.3 | 21.5 | 65.2 |

| Deformable DETR [54] | 39.8 | 45.4 | 32 | 28.2 | 180 | 11.1 | 3.1 | 65.5 |

| Sparse RCNN [55] | 44.2 | 29.8 | 21.9 | 19.2 | 200 | 10.0 | 2.8 | 57.7 |

| DNAnet [56] | 4.7 | 4.8 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 110 | 58.2 | 16.4 | 22.2 |

| RFLA [57] | 36.3 | 47.1 | 36.3 | 32.1 | 100 | 74.5 | 21.0 | 63.7 |

| C3Det [58] | 55.3 | 13.8 | 11.2 | 9.4 | 130 | 52.3 | 14.7 | 29.2 |

| PANet [59] | 33.5 | 52.3 | 38.7 | 34.2 | 95 | 72.5 | 20.3 | 68.1 |

| SNIPER [60] | 31.8 | 54.6 | 40.2 | 35.8 | 115 | 60.8 | 17.0 | 70.0 |

| M2Det [61] | 48.2 | 49.8 | 35.4 | 31.2 | 140 | 48.2 | 13.5 | 59.1 |

| GFL [62] | 35.6 | 56.2 | 41.8 | 37.3 | 105 | 71.5 | 20.0 | 70.8 |

| AugFPN [63] | 34.1 | 51.7 | 37.9 | 33.5 | 98 | 74.8 | 21.0 | 63.2 |

| YOLOv5s [12] | 7 | 83.6 | 50.9 | 49.1 | 60 | 142.9 | 40.2 | 84.4 |

| YOLOv8s [64] | 11 | 86.5 | 54.8 | 52.3 | 70 | 128.6 | 36.2 | 86.6 |

| YOLOv10s [65] | 14 | 89.2 | 58 | 55.7 | 85 | 105.9 | 29.8 | 89.3 |

| YOLO-SR | 4 | 95.1 | 73.2 | 65 | 37.7 | 150 | 59.9 | 93.9 |

| mAP0.5(xs) (%) | mAP0.5(vs) (%) | mAP0.5(s) (%) | mAP0.5(m/l) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faster R-CNN | 24.7 | 45.3 | 60.5 | 69.8 |

| YOLOV5s | 71.8 | 85.4 | 92.3 | 93.1 |

| YOLOV8s | 76.4 | 88.1 | 94.2 | 94.5 |

| YOLOV10s | 79.3 | 91.2 | 96.1 | 95.4 |

| YOLO-SR | 88.5 | 97.3 | 98.4 | 96.2 |

| Precision (%) | Recall (%) | mAP0.5 (%) | mAP0.5:0.95 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5s | 33.9 | 29.3 | 24.5 | 12.4 |

| SSD | 23.5 | 18.7 | 10.2 | 5.1 |

| CenterNet | 31.8 | 32.6 | 29.0 | 14.2 |

| RetinaNet | 39.2 | 30.8 | 31.67 | 16.3 |

| Faster RCNN | 29.4 | 23.5 | 20.0 | 8.91 |

| YOLO-SR | 42.5 | 34.7 | 31.7 | 17.5 |

| Precision (%) | Recall (%) | mAP0.5 (%) | mAP0.75 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5 | 91.4 | 78.2 | 83.6 | 50.9 |

| YOLOv5 + C2f-SA | 91.5 | 83.4 | 88.8 | 46.1 |

| YOLOv5 + C2f-SA + SPPC | 93 | 84.6 | 90 | 52.7 |

| YOLOv5 + C2f-SA + SPPC + DDect (YOLO-SR) | 96.7 | 91.3 | 95.1 | 73.2 |

| Original Params (M) | New Params (M) | Param Change (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Extraction Module | 2.1 (C3) | 1.6 (C2f-SA) | −23.8% |

| Feature Fusion Module | 2.62 (SPPF) | 3.67 (SPPC) | +40% |

| Detection Head | 0.8 (Head) | 1.69 (DDect) | +111.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, S.; Feng, X.; Xie, M.; Tang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Li, G. Lightweight YOLO-SR: A Method for Small Object Detection in UAV Aerial Images. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13063. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413063

Liang S, Feng X, Xie M, Tang Q, Zhu H, Li G. Lightweight YOLO-SR: A Method for Small Object Detection in UAV Aerial Images. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13063. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413063

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Sirong, Xubin Feng, Meilin Xie, Qiang Tang, Haoran Zhu, and Guoliang Li. 2025. "Lightweight YOLO-SR: A Method for Small Object Detection in UAV Aerial Images" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13063. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413063

APA StyleLiang, S., Feng, X., Xie, M., Tang, Q., Zhu, H., & Li, G. (2025). Lightweight YOLO-SR: A Method for Small Object Detection in UAV Aerial Images. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13063. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413063