1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of the aquaculture industry, which has significantly outpaced livestock and crop production over the last two decades [

1], has increased the demand for fish-derived feed inputs, particularly fish meal (FM) and fish oil (FO), leading to disproportionate fish harvesting and raising concerns for marine ecosystems and food security [

2]. Owing to its favorable functional (e.g., digestibility and palatability) and nutritional (e.g., essential amino acids and essential fatty acids) properties, FM remains a key dietary component, especially for carnivorous fish species; however, its limited availability has prompted efforts to reduce reliance on it. As harvested wild fish consumption continues to grow, the aquaculture sector thus faces increasing pressure to define environmentally sustainable alternatives to mitigate the overexploitation of oceanic resources while, at the same time, meeting the nutritional requirements for farmed fish, without compromising growth performance or nutrient utilization [

3]. Although FM replacement has usually relied on plant as well as animal by-products to reduce trophic transfer inefficiencies, new growth-promoting additives are now being explored for feed enhancement.

Among animal-rendered by-products, FM and FO replacement has been commonly achieved with poultry meal (PM) and poultry oil (PO). On the one hand, PM shares functional and nutritional properties with FM, offering advantages such as stable availability and lower cost. However, like other animal-based ingredients, PM composition is subject to variability, often resulting in nutritional deficiencies (especially essential amino acids) that might hinder the fulfillment of species-specific nutritional requirements [

4]. Despite these shortcomings, which have usually been addressed with the supplementation of deficient nutrients or with the combined use of alternative sources, PM has been utilized as an FM substitute at different inclusion levels in aquafeed formulations, influencing production efficiency in a species- and environment-dependent manner. This has prompted investigations into its effects on the gut microbiota across aquaculture species, including large yellow croaker (

Larimichthys crocea) [

5], gilthead seabream (

Sparus aurata) [

6,

7], Japanese abalone (

Haliotis discus hannai) [

8], rainbow trout (

Oncorhynchus mykiss) [

9,

10,

11], and European sea bass (

Dicentrarchus labrax) [

12]. On the other hand, PO has emerged as a promising candidate for FO replacement, in spite of differences in chemical composition. FO contains long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs), particularly

LC-PUFAs (e.g., eicosapentaenoic acid, EPA; docosapentaenoic acid, DPA; docosahexaenoic acid, DHA); in turn, PO is abundant in monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and

LC-PUFAs [

13]. Nevertheless, FO substitution with PO has been less explored, with existing studies focusing on gilthead seabream [

6] and yellowtail kingfish (

Seriola lalandi) [

13].

Beyond FM and FO replacement to enhance growth performance and feed efficiency, aquafeeds have also been supplemented with functional additives, notably organic acids (OAs). While widely adopted in livestock production, their application in aquaculture has been limited and is currently focused on high-value species. As nonantibiotic compounds with defined antimicrobial activity spectra, OAs are commonly administered as blends (OABs) to overcome the inconsistencies observed with single-acid applications. Similar to their growth-promoting effects, which are influenced by biological variables (e.g., species, physiological traits, and age) and extrinsic factors (e.g., rearing environment, dosage, and blend concentration), OABs have also been shown to modulate the gut microbiota in species- and formulation-specific manners, primarily by suppressing potentially pathogenic microbial populations [

14]. Moreover, for enhanced functional outcomes, OABs have often been combined with other bioactive feed components, such as essential oils, plant extracts, and enzymes. Microbiome studies have reported these synergistic effects in multiple species, including European sea bass [

15], rainbow trout [

16], and Nile tilapia (

Oreochromis niloticus) [

17,

18].

With the rise in antibiotic resistance, plant-derived compounds have progressively gained prominence as environmentally sustainable feed additives for the control of disease outbreaks in aquaculture farming thanks to successful applications in livestock production [

19]. Indeed, phytogenic feed additives (PFAs) are generally recognized for their therapeutically favorable characteristics, including minimal side effects, reduced drug resistance, and economic feasibility. Furthermore, PFAs exhibit anabolic (biomass enhancement, nutrient utilization, energy retention), immunoprotective (disease resistance, stress response), and cytoprotective (antioxidant, anti-inflammatory) properties [

20]. Their bioactive components (e.g., polysaccharides, flavonoids, polyphenols, alkaloids, saponins, and terpenoids) have especially demonstrated efficacy against a wide range of fish diseases, including bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic infections [

21]. Although PFA effects vary with concentration and preparation methods, phytochemicals could promote beneficial intestinal microbiota through fermentation, while suppressing pathogenic microbes [

20]. In this regard, investigations into PFA-mediated microbiota modulation have been conducted in several fish species, including largemouth bass (

Micropterus salmoides) [

22], barbel chub (

Acrossocheilus fasciatus) [

23], common carp (

Cyprinus carpio) [

24], Nile tilapia [

25], and rainbow trout [

26]. While the precise mechanisms behind PFA function in fish remain to be thoroughly elucidated, dietary intervention continues to offer one of the most practical approaches to promote aquatic animal health [

27].

In light of growing restrictions on chemotherapeutic use in aquaculture due to bioaccumulation risks, probiotics, together with plant-derived compounds, have emerged as suitable feed additives with multiple beneficial properties [

28]. Indeed, probiotic bacteria enhance growth, nutrient digestion, pathogen resistance, and stress tolerance, while probiotic yeasts support gut microbiota modulation, immune stimulation, and growth improvement. In contrast, probiotic filamentous fungi primarily promote the production of digestive enzymes, including amylases, xylanases, cellulases, β-glucanases, lipases, and proteases. Although typically of non-fish origin, multi-strain probiotics are increasingly derived from the native gastrointestinal microbiota of the fish host [

29]. In this regard, a dosage of 1

10

6 colony-forming units (CFUs) per gram of feed is generally suggested to ensure viable colonization [

30], despite optimal efficacy depending on biological (species, developmental stage) and non-biological (rearing environment, administration period, administration method) factors [

28]. Common probiotic strains usually include lactic acid bacteria (e.g.,

Bacillus,

Enterococcus,

Lactobacillus, and

Lactococcus) and yeasts, such as

Saccharomyces cerevisiae [

31,

32,

33]. Due to their influence on intestinal microbiota composition and homeostasis, probiotics have thus been investigated in various fish species, including Atlantic salmon (

Salmo salar) [

34], gilthead seabream [

35,

36], rainbow trout [

37], and Nile tilapia [

38]. Nevertheless, commercial strain selection must account for potential risks, including dysbiosis and zoonotic transmission [

28].

As a commercially valuable carnivorous marine species, European sea bass has been selectively bred to improve productivity (e.g., growth, feed efficiency, processing yields) and robustness (e.g., disease resistance, stress endurance, hypoxia tolerance) traits [

39]. In particular, breeding programs have expanded considerably in recent years through the application of parentage assignment via microsatellite markers, enabling accurate pedigree reconstruction without the need for physical tagging. This genetic approach has facilitated family-based selection for quantitative traits while simultaneously supporting genetic parameter estimation and inbreeding management. When combined with reproduction control through artificial fertilization, fish farmers have been able to establish controlled mating designs enhancing genetic gain and promoting the long-term sustainability of sea bass aquaculture [

40]. Given the selection of high-performing genotypes, it has become increasingly necessary to assess how dietary regimens influence intestinal microbiota composition in improved strains, as investigated in Torrecillas et al. [

41] and Rimoldi et al. [

42].

Building on the findings of Torrecillas et al. [

41] (hereafter referred to as Study 1) and Rimoldi et al. [

42] (hereafter referred to as Study 2), this study seeks to deepen the analysis of the intestinal microbiota of European sea bass by applying artificial intelligence (AI), with particular emphasis on machine learning (ML), to uncover patterns within the datasets obtained from both investigations. While machine learning has become essential to microbiome studies in human and livestock research, its application in aquaculture has remained limited [

43]. In this regard, machine learning has been successfully applied in aquaculture monitoring and analytics (e.g., species classification, biomass estimation, size measurement, behavior analysis, disease prevention, feeding frequency optimization, and water quality monitoring), spanning image-based and non-image-based implementations [

44,

45]. However, its use in fish-related microbiome studies has been scarce, with existing work largely restricted to the investigation of microbiota composition in relation to environmental conditions [

46,

47] and network modeling of microbial interactions with biotic and abiotic rearing parameters [

48]. To the best of our knowledge, machine learning has not yet been applied to investigate the relationship between microbial profiles and dietary formulations, especially in the context of feeds derived from more environmentally sustainable sources. Such applications are urgently needed in the aquaculture sector to minimize the depletion of marine stocks, reduce the disruption of food webs, and reduce the pressure on other intensive production systems [

2,

49]. This knowledge gap is particularly relevant given the growing interest in ML-driven design of environmentally efficient aquafeeds [

50] and the promising outcomes reported in livestock nutrition [

51]. While several bioinformatic tools are currently available for microbiome analysis, such as the Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction (ANCOM-BC) for differential abundance testing [

52], the Statistical Analysis of Metagenomic Profiles (STAMP) for taxonomic and functional profile testing [

53,

54], the Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) for biomarker discovery [

55], they are not intended for predictive modeling, being restricted to specific domains and generally unsuitable for commercial-scale applications. In contrast, machine learning delivers the scalability and adaptability needed to harness high-dimensional multi-omics datasets generated via next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies [

56]. Unlike conventional bioinformatic methods that often analyze features separately, machine learning also enables joint feature analysis, thus offering a more comprehensive perspective on microbial communities. In light of the considerable advantages afforded by machine learning, we developed a structured pipeline to reveal associations that may have been overlooked by conventional bioinformatic approaches routinely used in microbiota research. Accordingly, the following research objectives (ROs) were established: RO1, to investigate the presence of a distinct subset of microbial taxa exerting significant influence on predictive outcomes; RO2, to assess potential associations between gut microbiota composition and categorical combinations; RO3, to evaluate the extent to which dietary ingredient composition variations can predict shifts in microbial abundance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Experimental Procedures

Torrecillas et al. [

41] examined the interplay between genotype and diet in the intestinal microbiota of European sea bass using isolipidic, isonitrogenous formulations: a control diet (20% FM/5–9% FO) and an experimental diet (10% FM/10% PM/0% FO/1–3% PO/2–3% DHA oil). Diets were tailored to three developmental stages and produced in three pellet sizes to meet nutritional demands. Following a 42-week pre-trial period, fish were reared for 87 weeks in a flow-through system (FTS) under natural photoperiod conditions. At trial completion, autochthonous intestinal microbiota was sampled and analyzed via 16S rRNA gene sequencing (V4 hypervariable region). The authors found that, when considering high-growth (HG) and wild-type (WT) genotypes, genotype exerted a stronger influence on microbiota composition than diet. In particular, HG fish exhibited lower inter-individual variability, suggesting greater adaptive capacity to dietary changes as a result of selective breeding; conversely, genotype effects were largely confined to specific bacterial taxa, regardless of the diet.

Building on the formulation developed by Torrecillas et al. [

41], Rimoldi et al. [

42] used this diet as a control and supplemented it with individual functional additives: probiotics (

Bacillus subtilis,

Bacillus licheniformis, and

Bacillus pumilus at 2

10

10 CFU/g in equal ratios), organic acids (sodium butyrate), and phytogenic compounds (garlic extract with medium-chain fatty acids). After 42 weeks to reach the juvenile stage, fish were reared for 12 weeks in a recirculating aquaculture system (RAS), with feeding consisting of a high-dose phase (10 g/kg probiotics, 7.5 g/kg organic acids, 7.5 g/kg phytogenics for 2 weeks) followed by a low-dose phase (2 g/kg probiotics, 3 g/kg organic acids, 5 g/kg phytogenics for 10 weeks). After each phase, fish underwent a pathogen challenge (10

5 CFU

Vibrio anguillarum per fish via anal inoculation) and a stress test (high stocking density). At the end of the feeding trial, autochthonous intestinal microbiota was sampled and analyzed via 16S rRNA gene sequencing (V4 hypervariable region). Despite supplementation, the results showed no clear separation between control and additive-treated groups, although the relative abundance of specific taxa differed between genotypes.

2.2. Machine Learning Pipeline Implementation

Starting from the findings reported in Torrecillas et al. [

41] and Rimoldi et al. [

42], we used the microbial counts derived from 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the autochthonous intestinal microbiota of Europea sea bass from both studies; in this regard, the sequencing data had previously been deposited as FASTQ files into the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under accession numbers PRJEB47388 [

41] and PRJEB61519 [

42], with the preprocessing pipeline for metabarcoding sequencing data documented in the respective paper. Taxonomic classifications assigned to the amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) from both datasets were utilized without further modification or subset pooling, with SILVA as the reference database for taxa identification. In this study, we leveraged ML to uncover hidden patterns behind individual and synergistic relationships between diet and genotype across both datasets. To this end, ML analyses were conducted using ad hoc encodings to assess the influence of the categorical combinations considered across both studies (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). While microbial counts were available at different taxonomic levels (phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species), we focused on lower resolutions, namely family and genus, to ensure higher specificity and biological relevance [

57]; in particular, the species level was excluded because taxonomic resolution at this rank was insufficient in our 16S rRNA gene amplicon data generated with Illumina technology, whose short-read amplicon sequencing often lacks the sequence length and unique variation required to reliably discriminate closely related species [

58,

59].

To implement an efficient pipeline, we took both framework selection and model assessment concerns into consideration. On the one hand, we selected Python 3.13.3 as the reference programming language owing to its extensive support for data analysis libraries, which, in the proposed implementation, included: Pandas 2.2.3, NumPy 2.2.5, SciPy 1.15.2, scikit-learn 1.6.1, XGBoost 3.0.0, CatBoost 1.2.8, Matplotlib 3.10.1, and SHAP 0.46.0. On the other hand, given the small size of the original datasets, we applied leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) to maximize information utilization and minimize prediction bias, despite the increasing number of microbial features over taxonomic levels. Furthermore, we applied evaluation metrics tailored to balanced datasets to assess model performance: for classification, we used the accuracy (ACC) and the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC); for regression, we used the coefficient of determination (R

2), the mean absolute error (MAE), which assigns equal weight to errors, and the root mean squared error (RMSE), which assigns greater weight to larger discrepancies. While other performance metrics exist, particularly for classification, they are more frequently applied when dealing with imbalanced datasets. Common metrics include precision (i.e., the fraction of true positives among all predicted positives), recall (i.e., the fraction of true positives among all actual positives), and F1-score (i.e., the harmonic mean of precision and recall). However, for balanced datasets, accuracy offers more immediate interpretability, while MCC is considered more informative than F1-score as it takes into account the balanced ratio of confusion matrix categories (true positives, false positives, true negatives, false negatives) [

60]. Given the exploratory nature of this study, the highest performing model within each categorical grouping was determined through a comparative assessment of performance metrics rather than formal inferential testing. Accuracy was prioritized for classification tasks, while R

2 was emphasized for regression tasks, as both are widely accepted indicators of predictive reliability. The use of this strategy enabled the recognition of promising models while avoiding additional statistical analyses, with the understanding that more rigorous validation will be needed in future confirmatory studies. With these implementation choices, we sought to strike an effective balance between model reliability and output informativeness.

As a fundamental prerequisite for predictive modeling, both datasets underwent preprocessing to retain samples pertinent to the research objectives. Specifically, the original datasets, which consisted of 42 instances for Study 1 (130 families and 221 genera) and 60 instances for Study 2 (189 families and 316 genera), were filtered to exclude measurements related to feed and pre-feeding conditions. Following filtering, the datasets were reduced to 24 samples for Study 1 and 48 samples for Study 2. While this reduction improved the consistency and reliability of the input data by ensuring that genotype and/or diet were the sole influencing factors during feature selection, it nevertheless constrained the effective sample size available for modeling. Because smaller datasets can lead to models being overly tailored to a specific dataset, we mitigated potential effects on statistical power and model generalizability by consistently leveraging LOOCV and systematically comparing ML-derived results with conventional microbiome analyses reported in our prior studies, thereby confirming the consistency of the retained datasets with established findings. Additional preprocessing procedures also included handling missing values, removing null columns, and resolving data inconsistencies to ensure data integrity and reliability. These steps formed the foundational components of the analytical framework employed to pursue the research objectives outlined below.

RO1. In an effort to reduce dataset complexity, feature selection was performed to determine the most significant microbial taxa, enhancing model generalizability and mitigating overfitting. In the case of RO2, we applied recursive feature elimination (RFE) using ensemble-based, margin-based, and generalized linear models as supervised estimators. To ensure a balanced selection between permissive and conservative algorithms, we retained microbial taxa with the greatest overlap across estimators, under the constraint that, given as the number of features and as the number of samples, . In the case of RO3, we identified statistically significant microbial taxa through point-biserial correlation analysis and analysis of variance (ANOVA), each considering class grouping—namely, diet genotype combinations and, where applicable, diet alone. In order to ensure robust selection, we imposed threshold criteria of and for point-biserial correlation analyses, and a significance threshold of for ANOVA-based comparisons; in the latter case, taxa selection was conducted using a series of independent one-way ANOVAs. Although such feature selection approaches can reduce high dimensionality, they may lead to overfitting on small datasets and therefore select dataset-specific predictors: on the one hand, repeated model fitting on limited samples can inflate variance in feature-importance estimates for RFE, while, on the other hand, small sample sizes can destabilize correlation estimates and p-values in point-biserial correlation and ANOVA. Despite this overfitting potential, RFE, ANOVA, and point-biserial correlation offer methodological advantages over alternative selection approaches such as mutual information and Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO). RFE provides a model-specific, iterative framework that systematically removes less informative predictors, returning a ranked subset of variables optimized for predictive performance and reducing the risk of model overfitting. By contrast, point-biserial correlation is particularly well suited for binary classification tasks, as it furnishes a straightforward and interpretable measure of linear association between continuous predictors and binary outcomes, with minimal computational overhead. ANOVA complements these methods by enabling the statistical evaluation of mean differences across categorical groups and providing interpretable inferential outputs. Taken together, these techniques highlight the importance of statistical robustness and model-specific optimization, offering advantages in settings where balanced datasets and explicit feature relevance are prioritized, as opposed to the coefficient penalization of LASSO or the less interpretable nonlinear dependencies captured by mutual information. In both research objectives, nevertheless, any non-microbial contaminants or ambiguous taxa were manually removed.

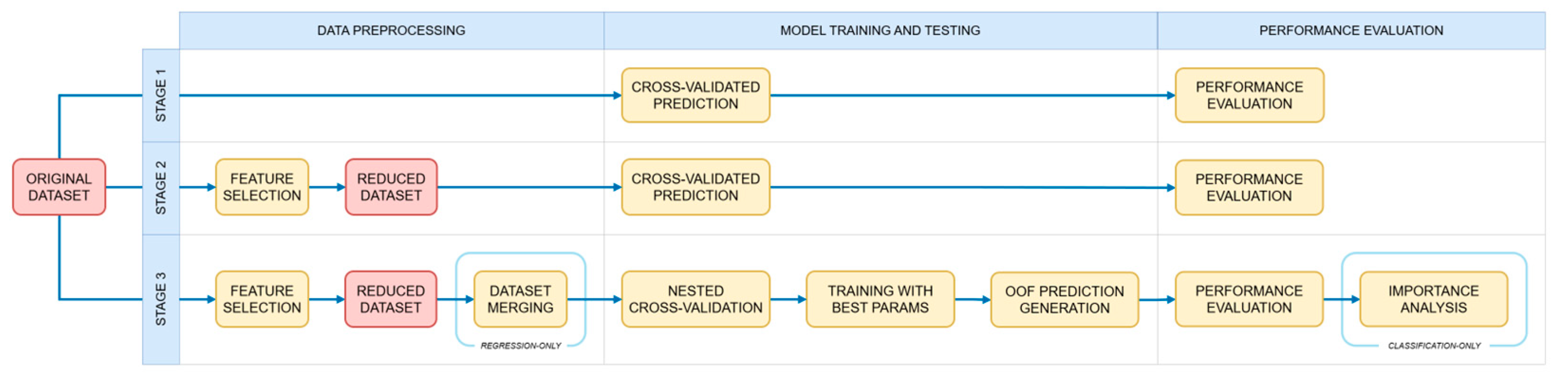

RO2–RO3. Both research objectives were addressed with a three-stage pipeline tailored to meet task-specific needs. In the first stage, models were evaluated on full datasets with default implementations to establish baseline performance. In the second stage, both datasets were reduced to include only the microbial taxa identified during feature selection, and models were evaluated using the same default settings to assess potential overfitting. Given the limited size of our datasets, we used cross-validation (CV) in both stages instead of traditional train–test splitting. This approach allowed to reduce variance in performance estimates arising from different split proportions and enhance generalizability. In the third stage, models were evaluated on the reduced datasets using nested cross-validation (NCV) to ensure unbiased performance evaluation while, at the same time, optimizing hyperparameters. In particular, the NCV function was designed to return both the average model performance (measured as accuracy in classification tasks and as root mean squared error in regression tasks) and the optimal parameter configuration. The latter was applied to evaluate models on the reduced datasets, producing out-of-fold (OOF) predictions able to approximate performance on unseen data. While both research objectives share a common analytical framework, their respective implementation peculiarities were addressed accordingly (

Figure 2). In the case of RO2, SHAP and rank analyses were performed to visualize the individual contributions of the most relevant taxa and to identify the most influential features across different class groupings. In the case of RO3, regression analysis required extending both datasets to include the respective quantities of diet ingredients reported in Torrecillas et al. [

41] (

Supplementary Table S1) and Rimoldi et al. [

42] (

Supplementary Table S2).

Since most algorithms are now capable of handling both classification and regression, we leveraged a diverse set of algorithmic families, each with distinct underlying mechanisms: tree-based (decision trees, DTs), ensemble-based (random forests, RFs; extra trees, ETs; gradient boosting, GB; extreme gradient boosting, XGB; categorical boosting, CB), margin-based (support vector machines, SVMs), probability-based (Naïve Bayes, NB), distance-based (k-nearest neighbors, k-NNs), neural network-based (multilayer perceptrons, MLPs), and generalized linear models (GLMs). In the case of RO2, as a classification task, we selected the following algorithms: DT classifier (DTC), RF classifier (RFC), ET classifier (ETC), GB classifier (GBC), XGB classifier (XGBC), CB classifier (CBC), multinomial NB (MNB), SVM classifier (SVC), k-NN classifier (KNC), MLP classifier (MLPC), and logistic regression (LREG). In the case of RO3, as a regression task, we selected the following algorithms: DT regressor (DTR), RF regressor (RFR), ET regressor (ETR), GB regressor (GBR), XGB regressor (XGBR), SVM regressor (SVR), k-NN regressor (KNR), and MLP regressor (MLPR). In both cases, SVM-based models were evaluated using various kernel functions (linear, LK; polynomial, PK; radial basis function, RK; sigmoid, SK) during the first two pipeline stages. However, in the final stage, LK was preferred due to its superior generalizability, mitigating the overfitting risks associated with PK and RK as well as the unstable behavior observed in SK. Ultimately, to guarantee proper learning and unbiased performance, datasets were standardized when using scale-sensitive algorithms.

4. Discussion

As aquaculture progressively shifts from reliance on oceanic resources toward more environmentally and economically sustainable practices, multiple feed ingredient alternatives have been evaluated as substitutes [

61]. Among these, poultry-based ingredients have historically represented a common replacement for FM and FO [

62]. Their viability as alternative protein and lipid sources at different inclusion levels has been well established over time [

63,

64], particularly in crustaceans and marine fish [

4]. In European sea bass, for instance, poultry-rendered ingredients have been combined with insect-derived ingredients within the framework of circular economy, offering nutritional potential without compromising growth performance, feed conversion efficacy, and overall health [

12]. In parallel, feed additives have emerged as important components of modern aquafeeds. Originally used to compensate for deficiencies in essential nutrients, additives are now increasingly recognized as functional ingredients capable of modulating metabolism and physiology, enhancing growth and health while also contributing to environmental and economic sustainability [

65]. Modern additives encompass different compounds, including probiotics, which have demonstrated beneficial effects on fish performance and health [

66]. While ingredient replacements and functional additives are gaining prominence as strategies to reduce environmental footprint and improve economic sustainability, their efficacy remains strongly dependent on species-specific factors and rearing conditions. To date, most studies have focused on growth performance and feed utilization, whereas the impacts of replacement diets on host-associated microbiota remain comparatively underexplored.

In our companion studies, we examined the dietary effects of poultry by-product ingredients (Study 1) and additive-based fortification (Study 2) in feeds on the gut microbiota of European sea bass. Microbial community composition was assessed in both cases with metabarcoding-derived abundance data. While both studies supported the validity of the proposed alternative dietary strategies, the relative contributions of diet and host genotype differed between them. Specifically, genotype exerted the strongest influence in Study 1, whereas diet was the predominant factor in Study 2, although these effects were restricted to a limited number of microbial taxa. Building on these findings, we conducted an in-depth analysis of microbial abundance patterns across both studies using artificial intelligence, specifically machine learning, to better characterize the interrelationship between host-associated microbiota and the individual as well as synergistic effects of diet and genotype, in line with our research objectives.

Although routinely applied in human microbiome research and, more recently, livestock studies due to its capacity to process and interpret large-scale datasets, artificial intelligence has witnessed limited application in fish microbiome studies [

43]. In the present work, artificial intelligence enabled to perform classification (RO2) and regression (RO3) tasks, as well as to identify minimal feature subsets associated with each dietary treatment (RO1), yielding informative results across both studies. In classification analyses, both studies demonstrated improved model accuracy when shifting from synergistic to individual factors for data categorization, with the combined grouping exhibiting the lowest predictive performance and genotype providing the highest discriminative ability. Indeed, the stronger effect of genotype, which was also reported in the reference studies, is supported by the larger number of specimens attributable to this grouping compared to the combined one. This ensured a sufficiently robust sample size for representative inference on data derived from metabarcoding analyses, despite the determination of a suitable sample size remaining contested. Indeed, recent combinatorial studies on European sea bass and gilthead seabream suggest that nine individuals per group may suffice to capture approximately 90% of bacterial species richness, thus offering representative insights into microbial shifts [

67]. In this study, the sample size for the combined grouping did not permit confirmatory outcomes, in agreement with the conclusions of Panteli et al. [

67] on microbiome investigations with comparable biological replicates [

36,

68,

69]; nevertheless, comparable small sample sizes have also been used in pilot microbiome studies on livestock [

70,

71,

72] and humans [

73,

74]. When considering the individual groupings, on the other hand, sample size proved sufficient to provide preliminary support for the feasibility of our predictive pipeline. At the same time, the transition from multiclass to binary classification likely contributed to the improved performance, given the reduced algorithmic complexity of binary classification. By contrast, regression analyses in both studies produced unsatisfactory results, highlighting the need for further methodological refinement to enhance predictive power. Such improvements will be essential to enable the development of dietary interventions at the level of individual feed ingredients. While the regression outcomes underscore the necessity for optimization at the implementation stage, the classification results support the feasibility of our approach and thus provide a foundation for the development of ML pipelines capable of interrogating more complex datasets and uncovering more intricate host-microbiota-diet relationships.

Predictive performance differed markedly between regression and classification. Regression analyses yielded unsatisfactory results, likely due to the limited sample size and the high degree of similarity between diets in each study, differing only in a limited number of ingredients and in minor quantities. This lack of variability may have hindered the identification of patterns linking formulation differences to shifts in microbial abundance. Greater diversification in ingredient quantities could potentially enhance the ability to detect such relationships. In addition, future studies may benefit from the application of more advanced regression techniques like penalized regression models, such as LASSO (based on L1 regularization), Ridge (based on L2 regularization), and Elastic Net (combining L1 and L2 regularization) [

75]. Despite these methodological possibilities, the regression models applied in this study did not achieve sufficient predictive power to support meaningful biological interpretation. By contrast, classification analyses produced promising results, thus warranting further investigation. Across both studies, tree-based (DTC) and ensemble-based (RFC, ETC, CBC, GBC, XGBC) models demonstrated higher performance, with ensemble models proving particularly effective. This advantage could be attributed to the capacity of ensemble methods to mitigate overfitting as well as maintain robustness to noise, albeit at the expense of higher computational resources and reduced interpretability relative to single-tree models [

56,

76,

77]. The enhanced performance of ensemble-based models has also been reported in studies applying machine learning to fish microbiota, although such investigations have usually focused on associations with contaminated environments rather than dietary influences [

46,

78]; nevertheless, research leveraging machine learning on fish microbiota remains scarce. Comparable outcomes were observed with probability-based (MNB) and distance-based (KNC) models, which are valued for rapid training and high interpretability, although they exhibit sensitivity to correlated or irrelevant features. Margin-based (SVC), neural-network-based (MLPC), and generalized linear (LREG) models also merit consideration, despite attaining comparable performance only within specific categorical groupings. These limitations are consistent with their inherent characteristics: margin-based models are optimized for high-dimensional spaces, whereas neural networks generally require large datasets to achieve optimal training. Nevertheless, SVC and LREG remain widely common in microbiome research [

56,

77], including the few studies applying machine learning to fish microbiota [

46,

78]. In the case of SVC, reduced performance may be attributed to the use of the linear kernel, which has been selected due to its generalizability and stability, rather than the radial basis function, which is frequently adopted as a default kernel despite its higher risk of overfitting. For MLPC, performance decrease likely reflects the small sample size, which constrains the capacity of the model to detect meaningful patterns. Despite outcome variability across both studies, machine learning has demonstrated efficacy in extracting information at multiple taxonomic levels [

79], underscoring the need for further refinement of the implemented analytical pipeline.

Classification results were strongly influenced by the feature selection process, which proved instrumental in both mitigating overfitting and enhancing model generalizability. Building on these favorable results, the microbial taxa identified with feature selection in the classification task were further investigated to assess their biological relevance. Given the high taxonomic resolution afforded by the SILVA database, together with the findings reported in both companion studies, result interpretation focused on the genus level, for which, based on the most prevalent taxa described in Study 1 and Study 2, high-frequency (HF) and low-frequency (LF) genera were defined. For Study 1, HF genera included Clostridium sensu stricto 1 and Enhydrobacter, which were part of the study-specific core microbiota established by the authors; LF genera included Pseudoalteromonas and Flavobacterium. For Study 2, HF genera included Acinetobacter, Cutibacterium, Enterovibrio, Escherichia-Shigella, Idiomarina, and Streptococcus; LF genera included Acholeplasma, Brevundimonas, Lactobacillus, Marinobacter, Micrococcus, Peptoniphilus, Photobacterium, Salegentibacter, Salinisphaera, and an unclassified member of the family Flavobacteriaceae.

From an ecological perspective, the microbial genera comprising HF and LF groups in both studies are known to influence the gut health of fish hosts through beneficial, neutral, and pathogenic roles.

Clostridium sensu stricto 1,

Lactobacillus, and

Brevundimonas are frequently associated with fermentation of dietary substrates, production of short-chain fatty acids, and probiotic effects capable of improving immunity and growth [

34,

80,

81]. Marine-associated taxa like

Idiomarina,

Marinobacter,

Pseudoalteromonas, and

Salinisphaera contribute to ecological stability by degrading complex polysaccharides or hydrocarbons and by producing antimicrobial compounds that suppress pathogens [

82,

83,

84,

85].

Enterovibrio,

Flavobacterium and

Photobacterium include commensal and pathogenic species, reflecting the dual role of some genera in nutrient cycling and disease [

86,

87,

88]. Opportunistic or conditionally pathogenic taxa such as

Acinetobacter,

Escherichia-Shigella, and

Streptococcus can compromise gut homeostasis under stress conditions [

89], while genera like

Acholeplasma,

Cutibacterium,

Enhydrobacter,

Micrococcus,

Peptoniphilus, and

Salegentibacter are less characterized but may contribute to microbial diversity and niche occupation. Collectively, these genera shape gut health by mediating digestion, modulating immune responses, and influencing resilience against environmental stressors, with their impact depending on host species, diet, and microbial balance.

In the case of Study 1, HF genera were associated with the DG1 grouping, with Clostridium as the only genus for which a statistically significant interaction effect was detected through conventional microbiota analyses; moreover, using our approach, Enhydrobacter was identified as an additional genus with influence on the interaction effect. In contrast, LF genera included Pseudoalteromonas and Flavobacterium, which, in the companion study, showed no statistically significant effect with D1 or G1, respectively. For the G1 grouping, while Flavobacterium was not among the genera identified as significant in conventional microbiota analyses, statistical significance was observed at the family level for Flavobacteriaceae. In light of the high accuracy attained by the selected models, however, Flavobacterium alone was sufficient to predict the dietary regime, without the inclusion of additional genera, thereby suggesting a functionally significant role for this taxon. For the D1 grouping, instead, conventional analyses did not identify any statistically significant associations with microbial taxa; in contrast, our feature selection approach identified Pseudoalteromonas as the sole genus required to achieve accurate diet-based classification.

In the case of Study 2, for the DG2 grouping, conventional techniques identified Acinetobacter and Enterovibrio as genera demonstrating statistically significant interaction effects; furthermore, both genera were classified as HF taxa by the feature selection procedure, which, however, also highlighted other influential genera, particularly among the LF group. For the D2 grouping, feature selection identified a smaller set of predictive genera compared with those detected as statistically significant by conventional techniques. Streptococcus was the only genus shared between approaches, while Acholeplasma and Lactobacillus were uniquely identified through feature selection and not detected by conventional methods. For the G2 grouping, conventional analyses found statistical significance only for Photobacterium, which was likewise included in the feature set returned by feature selection, while Micrococcus was restricted to the ML-derived feature set.

In both studies, the use of machine learning for feature selection deepened our understanding of the microbial genera impacted by diet, genotype, and diet

genotype interactions. In this regard, while ML-based feature selection was largely consistent with conventional microbiota analyses, with statistically significant taxa also captured within the ML-derived feature set, it additionally identified microbial taxa not originally reported as such. For Study 1, the following additional genera were identified:

Enhydrobacter (DG1),

Pseudoalteromonas (D1), and

Flavobacterium (G1). For Study 2, the following additional genera were detected:

Brevundimonas,

Cutibacterium,

Escherichia-Shigella,

Idiomarina,

Lactobacillus,

Marinobacter,

Peptoniphilus,

Salegentibacter,

Salinisphaera, and

Streptococcus (DG2);

Acholeplasma and

Lactobacillus (D2);

Micrococcus (G2). When these findings were compared with HF and LF genera reported in both studies, a greater number of LF genera was observed. This suggests that low-abundance taxa may exert a stronger influence on gut microbiota profile than previously estimated with conventional microbial community analyses, despite not being recognized as core microbiota components [

90,

91]. These results benefited from the capacity of machine learning to mine data more extensively than conventional techniques, owing to the broader range of available models and the possibility to evaluate features concurrently rather than independently. Moreover, the independence of ML models from biological assumptions enabled the recognition of subtle patterns that may be overlooked by conventional methods.

Despite the generally unsatisfactory predictive performance observed in regression models, the results of the feature selection procedure warrant brief consideration. In Study 1, statistically significant features were identified only within the DG1 grouping, whereas no features were selected for the D1 grouping. In Study 2, by contrast, the procedure detected significant features for the DG2 and D2 groupings. These findings find support in the microbial diversity analyses reported in the reference studies, although the observed effects were generally restricted to specific taxa. Specifically, Study 1 revealed interaction effects without evidence of a diet effect, while Study 2 identified both interaction and diet effects. Notably, however, the microbial taxa highlighted by the feature selection procedure did not fully overlap with those reported in the original analyses, thus underscoring the need for further investigation. This discrepancy suggests that, while the selection algorithm was capable of detecting statistically significant features, the biological relevance of these findings remains uncertain.

4.1. Methodological Considerations and Research Horizons

The present study offers valuable insights into the individual and synergistic effects of multiple factors (diet and genotype) on the autochthonous intestinal microbiota of European sea bass; however, certain limitations must be addressed to ensure scientific completeness, transparency, and rigor.

4.1.1. Computational Considerations

Compared to research studies on fish growth performance, the sample sizes used in the present work were relatively limited (24 fish for Study 1, 48 fish for Study 2), though numerically consistent with those reported in microbiota-focused studies [

46,

92,

93]. While larger sample sizes are usually recommended to enhance statistical robustness and diet-induced microbiota shift detection [

94,

95,

96], to minimize dataset-specific bias, we implemented computational strategies including feature selection to reduce dimensionality, LOOCV to maximize data utilization, and NCV to separate hyperparameter tuning from model evaluation [

97]. We also decided against data augmentation, given that the artificial manipulation of biological datasets may result in the introduction of unrealistic patterns and thus compromise biological validity. Nonetheless, current research is investigating targeted augmentation strategies to address these challenges, particularly in the context of microbial datasets [

98,

99,

100]. Moreover, we acknowledge certain limitations associated with the feature selection procedure: on the one hand, feature selection was performed on the entire datasets prior to modeling, thereby introducing a potential risk of data leakage; on the other hand, taxa identification is inherently dependent on the algorithms used to implement the selection procedure, which could return feature sets differing from those reported in this study when using different learning estimators, selection functions, and inclusion criteria. While our choice to define a common feature set prioritized interpretability and consistency, future work could address overfitting by performing feature selection within each fold of nested cross-validation, followed by consensus procedures to derive a unified feature set for better interpretability. With larger datasets, feature selection could also be limited to a dedicated subset since such data volumes generally ensure representativeness [

77,

101]. Furthermore, taxonomy-aware feature engineering approaches, which leverage phylogenetic hierarchy to create compact and informative feature spaces, may provide even more insightful outcomes in supervised contexts [

102]. Despite the present constraints, the alignment between ML-derived findings and those obtained through conventional methods reinforces the reliability of our approach and highlights its potential for future applications.

In microbiome studies with small sample sizes, informative feature selection has generally relied on established bioinformatic tools (e.g., ANCOM-BC, STAMP, LEfSe), which, while offering interpretability through conventional statistical metrics (e.g.,

p-values, confidence intervals, effect sizes), remain domain-specific and unsuitable for predictive modeling in supervised contexts. By contrast, machine learning offers the ability to jointly assess features, quantify feature importance, capture interaction effects and co-occurrence patterns among taxa, and manage high-dimensional data. In line with our research objectives, we implemented ML models capable of evaluating multiple features simultaneously and integrating with explanatory frameworks, thus balancing predictive capability with biological interpretability and complementing conventional microbiome analyses. However, considering the considerable shift toward ML-based approaches in microbiome research, it is important to acknowledge that the black-box nature of ML models poses interpretability challenges for non-experts. To overcome this, hybrid strategies integrating domain-specific methods with ML models within unified analytical pipelines have been proposed. For instance, in a recent colorectal cancer study, LEfSe and ANCOM-BC were used to characterize individual taxa with altered abundance in affected patients, followed by a Bayesian machine learning model to substantiate compositional differences observed in individual microbial markers [

103]. Within such combined frameworks, machine learning contributes scalability and flexibility for handling high-dimensional, multi-omics datasets, while domain-specific tools provide biologically grounded insights based on transparent assumptions. Leveraging transdisciplinary knowledge transfer [

104], these hybrid implementations could be applied to aquaculture research, fostering intelligent fish farming and providing deeper insights into microbiota alterations driven by different dietary and rearing conditions. Building on the research of Zakaria et al. [

105], who demonstrated the integration of artificial intelligence with gut microbiota modulation for disease detection in shrimp aquaculture, a comparable hybrid pipeline can be envisioned for precision aquaculture in fish farming. Conventional bioinformatic techniques could serve as a first step in filtering and prioritizing candidate microbial features, thus reducing dimensionality and ensuring biological relevance. Selected features can then be incorporated into ML models capable of modeling complex nonlinear interactions with environmental and dietary parameters. This pipeline could facilitate early detection of stress or disease, optimize feed formulations to support beneficial microbial communities, and provide real-time decision support for farmers. Ultimately, the convergence of machine learning and bioinformatic tools represents a promising paradigm for precision aquaculture, enabling microbiota-informed predictions that support the sustainable management of dietary and rearing practices while preserving interpretability.

4.1.2. Biological Considerations

While ML modeling in this study was performed on microbiota abundance data, it is important to consider the rearing system used, namely FTS in Study 1 and RAS in Study 2, as they exert direct effects on microbial communities [

106]. In FTS, fish are continuously exposed to a constant influx of externally renewed water, resulting in higher environmental microbial input and greater temporal variability in intestinal communities. In contrast, RAS limit external microbial inputs through water treatment processes, while relying on biofilter-associated microbiota to maintain water quality. Indeed, these controlled rearing configurations enhance host-mediated selective pressures that foster the establishment of facility-specific microbial assemblages, thereby acting as physical environments as well as ecological filters that shape the microbiota communities colonizing the host gut. As such, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the specificity of microbiota associated with the rearing system may have influenced the features selected in each study. This raises the important methodological consideration that the discriminative features identified through machine learning may not solely reflect diet and/or genotype effects but also capture signatures of the rearing environment itself. This influence is especially relevant when comparing studies across facilities or rearing systems, as the microbial baseline established by RAS or FTS may bias feature selection toward taxa that are characteristic of the system rather than universally associated with diet or genotype. Therefore, it should not be definitively ruled out that the selected features are partly representative of the rearing system, in addition to the combined and/or individual effects under examination. The acknowledgment of the role of rearing-system-specific microbiota enhances the interpretive framework of aquaculture microbiome studies, highlighting the importance of distinguishing between host-driven and environment-driven microbial signals and thus ensuring that predictive pipelines capture biologically meaningful patterns rather than artifacts of facility-specific microbial ecology. Beyond rearing conditions, it is important to acknowledge that 16S rRNA gene sequencing can introduce methodological biases depending on experimental design choices, potentially affecting abundance estimation and thus compromising community diversity assessment [

107,

108]. Together with other factors influencing microbiota analysis (e.g., species, life stage, captivity status), these considerations highlight the importance of rigorous experimental design and methodological consistency in microbiome research to ensure reliability, reproducibility, and knowledge transferability across studies.

As this investigation was conducted within a ML framework, the validation of both the selected models and the feature subsets identified in each study on external datasets constitutes a fundamental step in ensuring pipeline robustness. However, it is important to notice that, although poultry-derived and fortified feeds have frequently been used as FM and FO substitutes, both studies utilized specifically developed feed formulations. As such, the present study focused on the implementation of diet-specific predictive models able to learn patterns unique to each dietary formulation. Consequently, robust external validation would necessitate datasets derived from European sea bass reared under comparable conditions and fed identical diets to avoid feature misattribution, reduced predictive performance, or misleading conclusions; however, to the best of our knowledge, no such datasets are currently available that would enable the external validation of our models without introducing potential bias.

As publicly accessible microbiome datasets become increasingly common, large-scale research programs and consortia are simultaneously emerging to expand this knowledge. Although still modest in scale compared to landmark initiatives such as the Human Microbiome Project, these efforts are oriented toward mapping, engineering, and applying microbiomes in aquaculture under diverse environmental and rearing conditions. A central focus lies in the development of integrated multitrophic aquaculture (IMTA) systems, which provide experimental platforms for investigating innovative and environmentally sustainable feeds, thus positioning aquaculture practices within the broader paradigms of the circular economy and the One Health approach. Importantly, the emergence of these initiatives underscores both the scientific potential of microbiome-informed aquaculture and the urgent need to reform data-sharing policies [

109]. Establishing clear guidelines for equitable reuse and interoperability of datasets will be crucial to ensure that the benefits of these programs extend across disciplines, regions, and stakeholders, ultimately fostering a more collaborative and sustainable research ecosystem.