1. Introduction

Materials used in modern medicine must meet a range of standards and requirements [

1], preceded by thorough scientific investigations. The aim of these studies is to confirm that the use of the aforementioned materials is entirely safe [

2]. A further challenge for materials employed in medicine is the environment in which they are to be used, namely the human body [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Human tissues are characterised by an organised, yet irregular internal structure, influenced by numerous factors such as age, sex, anatomical location and physiological function [

3,

7,

8,

9]. For the purposes of this article, particular emphasis was placed on human bone tissues. These pose a significant challenge to researchers aiming to fully replicate their properties and functions when attempting to replace them with materials other than human bone tissue. The primary functions of bone tissue include the continuous production of blood and the transport of mineral components throughout the body, which was particularly emphasised in three key studies: Ethier et al. [

3], Robling et al. [

10] and Hart et al. [

6]. Beyond these physiological roles, a key function of bones is to provide stable structural support enabling movement and protecting internal organs, as it states in Refs. [

5,

6,

10]. The characteristic and organised internal architecture of bones [

5,

6,

10,

11] is directly related to the internal and external forces acting on the passive human musculoskeletal system. As has been demonstrated, in areas of high stress concentration, the internal structure of bone can undergo remodelling-strengthening, such as in the region of the femoral bone head, strongly emphasised by many recent studies [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The bone tissue capacity for regeneration and repair (e.g., following fracture) enables the integration of bones with various types of implants. Currently, medical practice utilises grafts such as allografts, xenografts or autografts as well as synthetic implants manufactured from bone substitute or biocompatible materials. This approach is well documented in numerous studies [

1,

3,

9,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

The primary challenge in bone–implant integration is not only achieving stable fixation but also preserving the bone ability to perform its aforementioned physiological functions. Regarding these physiological functions, as proven in other studies [

16,

21,

22,

23,

24], the implant surface should facilitate appropriate bonding and anchorage of bone tissue within the implant structure (porous surface). It allows bone ingrowth onto the implant surface and thereby enables restoration of the bone physiological function. Maintaining the mechanical functions of bones can be considerably more challenging to achieve. It is crucial that the materials used should possess strength properties comparable to those of the bone to which they are to be joined. This is particularly important due to the potential occurrence of stress concentrations at the interface between a material with higher mechanical parameters and that characterised by lower mechanical properties [

1,

4,

5,

10,

25,

26]. Making an implant with mechanical parameters significantly exceeding those of bones may lead to bone resorption at the implant–bone interface. This phenomenon results from improper load distribution, where stresses are primarily transferred by the implant structure. It has also been observed that the bone–implant junction should provide an appropriate level of rigidity, which is crucial during the bone regeneration phase as it reduces the risk of graft rejection by the organism [

7,

14,

15,

25]. Medical implants address these challenges by being fabricated from suitably prepared materials such as metal alloys, ceramics, polymers or their composites [

17,

18,

19,

21,

23,

24,

27,

28]. The choice of an appropriate material depends directly on the intended function it is to perform within the human body. The use of composite materials for implant fabrication can offer numerous advantages such as providing adequate reinforcement and desired mechanical properties through the primary, more durable component. At the same time, it enables the creation of a tailored, biocompatible or bioactive base favouring the proliferation of biological tissues to be formed in the future [

3,

9,

17]. As Glenske et al. [

29] points out, to date, fabricated implants have been characterised by a homogeneous internal structure, exhibiting the mechanical properties of an isotropic material. Developing a bone substitute material with a structure and mechanical properties similar to those of the bone structure could enable the development of a new generation of implants. According to numerous sources [

4,

22,

30,

31,

32], trees most closely resemble bones in terms of their internal structure. Their characteristic, organised and oriented structure mirrors the internal structure of bones in many respects, including the possibility of transporting nutrients from the roots to the crown and back—thanks to specialised structures such as tracheids and vessels [

32,

33,

34]. Trees also exhibit the ability to adapt and rebuild in areas particularly exposed to increased load or deformation, enabling them to prevent fractures [

4,

30,

31,

32]. However, structural similarities alone are insufficient to utilise raw wood. A series of technological processes is required to transform the natural material into a biomorphic one suitable for applications in the human body. Crucially, this must be achieved while preserving its structural features and properties as faithfully as possible [

22,

30,

31,

32,

33,

35,

36,

37].

The technology enabling the adaptation of natural materials for medical applications is the process of pyrolysis. Pyrolysis, also referred to as carbonisation, involves the thermochemical decomposition of biomass under anaerobic conditions. These conditions are typically ensured by an appropriate (controlled) environment, involving the use of a sealed (tight) machine chamber and a continuous supply of argon or nitrogen to the chamber [

38,

39,

40]. Due to the necessity of providing heat input to initiate and sustain the pyrolysis process, the reaction is classified as endothermic. This process primarily involves elements (chemical compounds) responsible for the structural composition of plants, e.g., trees, i.e., cellulose, hemicellulose or lignin [

30,

31,

32]. The thermal energy supplied to the heating chamber triggers the breakdown of these compounds into smaller particles in the form of gases, liquids or solids. The pyrolysis process can be represented by the following chemical reaction Formula (1) [

39].

During the pyrolysis of wood, three reaction products can typically be observed, i.e., solid biochar, liquid and gas. Fu et al. [

20] confirmed that biochar is the solid product of wood pyrolysis, containing mineral fractions and composed predominantly of carbon. The second product of pyrolysis, i.e., a liquid in the form of water vapour, consists not only of water but also of an organic fraction characterised by a complex chemical composition, primarily containing homologous phenolic compounds [

39]. The final product of pyrolysis includes the release of both condensable gases (liquefying upon cooling and composed of heavy molecules) and non-condensable gases (carbon dioxide, methane, ethane, ethylene and other secondary gases, characterised by relatively small molecular size) [

20,

39,

40]. The primary objective of pyrolysis in the context of medical applications is to convert wood into a biocompatible material exhibiting bioactive properties. In modern medicine, bioactivity is a highly desirable characteristic as it enables controlled drug delivery systems to release therapeutic agents to a targeted site at a specific time. Such a site may be the inflamed area surrounding a resected bone segment replaced by an implant or cellular scaffold. Pyrolysis produces a scaffold, i.e., a carbonaceous matrix, serving as an appropriate substrate for bonding with other chemical compounds [

3,

39,

41].

The aim of this study was to determine the mechanical properties of plant-derived biochars. The intended application of the examined biochars is their use as bone substitute materials. Therefore, particular emphasis in this article was placed on human bone tissues. The study-related tests aimed to identify which variant of the tested material groups exhibits mechanical properties (Young’s modulus and flexural strength) most closely resembling those of selected human bones. The study also involved the assessment of the effect of the pyrolysis process on the mechanical properties of the analysed plant-derived samples. Furthermore, the study included a comparative analysis concerning the results obtained for the different species (groups) of selected samples.

2. Materials and Methods

The mechanical properties of the tested samples were determined using two measurement methods, enabling the obtainment of detailed and reliable results. The first method was the classical static three-point bending test, conducted using an MTS Criterion Model 43 testing machine (MTS Systems, Eden Prairie, MN, USA). This method enables the determination of key parameters such as Young’s modulus and flexural strength, which are essential for assessing the mechanical properties of materials. The second method, involving the use of the Digital Image Correlation (DIC) system (Dantec Dynamics A/S, Skovlunde, Denmark), makes it possible to perform a precise analysis of sample deformation under loading conditions. This technique is based on capturing images of the sample surface and enables the obtainment of deformation-related information in real time. As a result, it is possible to receive more precise data on the material behaviour under loading conditions. The application of both measurement methods in the study of the mechanical properties of bone substitute materials, such as plant-derived biochars, enables a comprehensive evaluation of their suitability for medical applications in terms of mechanical properties.

2.1. Material

The study was conducted using a total of 100 samples obtained from trees of various species. Two, i.e., soft-structured and hard-structured, types of wood were compared. The first group included samples from fir and poplar, whereas the second group contained samples from oak and hornbeam. For each of the four tree species, 25 samples were prepared with dimensions appropriate for conducting the static three-point bending test. The aim of the tests was to compare the selected tree species in terms of their mechanical properties (changing under the effect of pyrolysis temperature). The pyrolysis process was carried out on a total of 80 samples at temperatures of 400 °C, 600 °C, 800 °C and 1000 °C (five samples per specified temperature).

The samples were obtained by precisely cutting larger wooden slats using a Struers Secotom-15 cutting machine. The measurement diagram concerning the wooden samples is presented in

Figure 1. The length (L) was defined as the longest side of the sample. The width (W) was taken as the dimension along the grain orientation, whereas the thickness (T) was the dimension of the transverse grain arrangement. An example of the sample arrangement during tests is presented in

Figure 1, where the sample was loaded transversely to the direction of the grains.

The average length of all the samples prepared for the tests in a raw state was 79.98 ± 0.36 mm. In turn, in terms of the samples after the pyrolysis process, that dimension amounted to 66.26 ± 0.37 mm. Regarding the remaining dimensions of width and thickness, required for the tests, the raw samples had average values (width × thickness) of 10.37 ± 0.19 mm × 9.91 ± 0.22 mm. The samples shrunk after the pyrolysis process. The average values of width and thickness after pyrolysis were 7.89 ± 0.26 mm and 7.07 ± 0.27 mm, respectively. The samples before and after the carbonisation process were measured using a HELIOS PREISSER DIGI-MET 1320 417 electronic calliper (HELIOS-PREISSER, Gammertingen, Germany)—provided with a currently valid quality certificate. After determining the geometric dimensions of the samples in their raw state and following the carbonisation process, the mass of the samples was determined using a RADWAG laboratory scale (RADWAG, Radom, Poland). To determine the apparent (geometric) density of the samples before and after the pyrolysis process, Formula (2) was used.

The obtained values were used for a preliminary assessment of the effect of the pyrolysis process on the analysed tree species.

Table 1 presents the average dimensions of the samples before and after the pyrolysis process.

Table 2 summarises the results of calculations performed on samples, along with additional data on the samples tested—mass, volume and density.

2.2. Pyrolysis Process

The pyrolysis process was carried out in a horizontal tube furnace manufactured by CZYLOK (CZYLOK Sp. z o.o., Jastrzebie-Zdroj, Poland) under a nitrogen atmosphere, at temperatures of 400 °C, 600 °C, 800 °C and 1000 °C. The heating rate during the process was 3 °C per minute. Once the target temperature had been reached, the samples were held at the temperature for one hour and cooled under a nitrogen atmosphere (to a room temperature of approximately 22 °C). For each of the specified temperatures, five samples were selected and prepared from each tree species (fir, poplar, oak and hornbeam). The samples prepared for the pyrolysis process (in their raw state) are presented in

Figure 2a. The same figure also presents the outcome of a correctly conducted pyrolysis process at a temperature of 800 °C, whereas

Figure 2b shows the samples before the test and

Figure 2c the samples after the three-point bending test.

2.3. Strength Analysis Using a Static Uniaxial Three-Point Bending Test

The strength tests were performed using an MTS Criterion Model 43 universal testing machine (MTS Systems, Eden Prairie, MN, USA). Mechanical properties were determined in a three-point bending test. The test stand was equipped with a set of specialised grips and a force sensor with a measurement range of up to 2.5 kN. The three-point bending test was performed at a rate of 2 mm/min, with a support span set at 50 mm. The data acquisition frequency amounted to 10 Hz. The strength tests were conducted at a room temperature of 22 °C and a relative humidity of 50%, with the support span fixed at 50 mm. Each strength test was performed at a room temperature of 22 °C and a humidity of 50%. Prior to testing, each sample was precisely measured. A representative method of sample mounting is presented in

Figure 3.

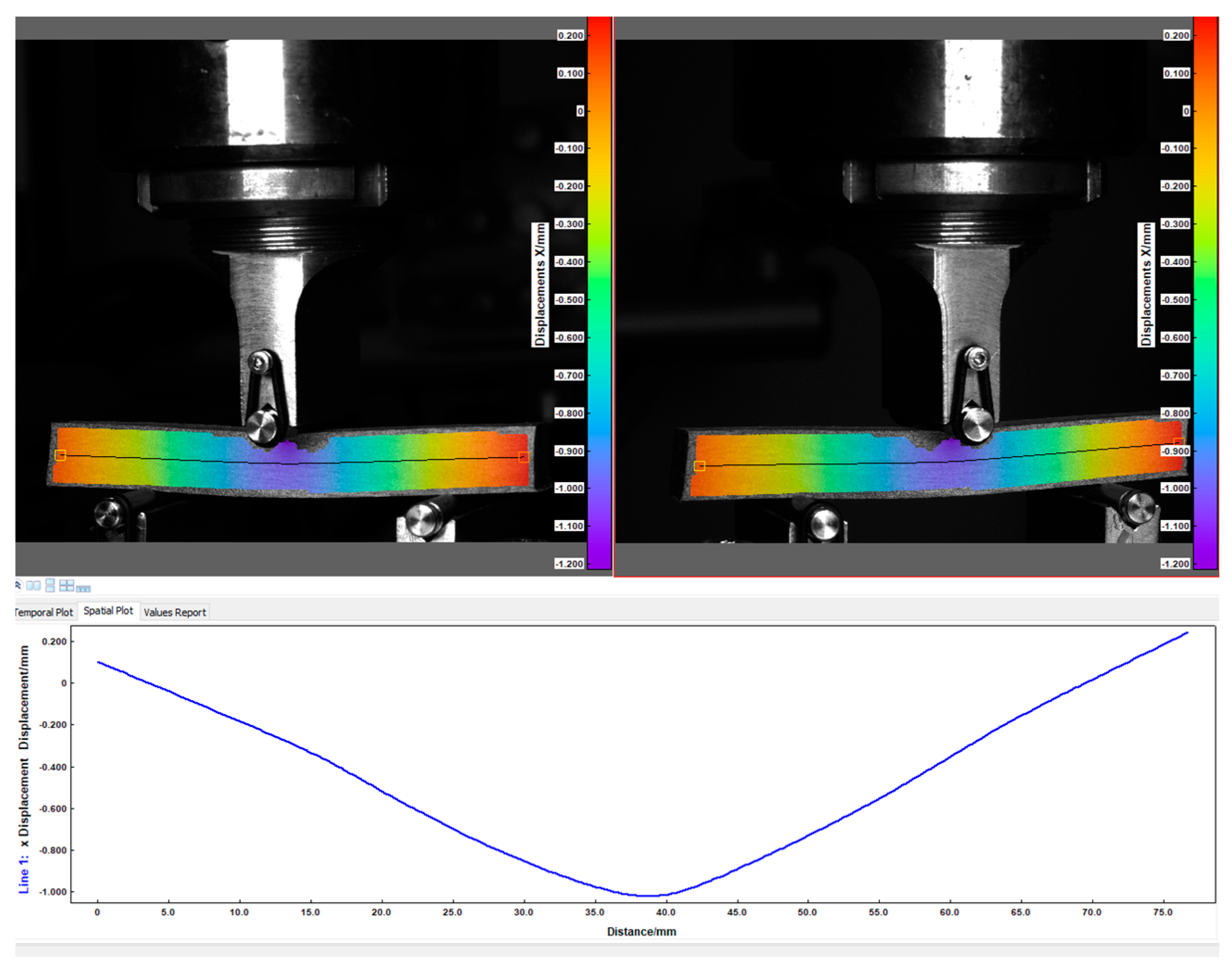

2.4. Strength Analysis Using Digital Image Correlation System (DIC)

The second key component of strength tests, used alongside the universal testing machine, is the Digital Image Correlation (DIC) system (Dantec Dynamics). This system operates by monitoring a single surface of the tested material using special cameras. To ensure accuracy of the system operation, the sample surface must be properly prepared. In the initial stage, after the carbonisation, a thin layer of white paint was applied onto the sample surface in order to create a uniform background. Subsequently, black markers were added, used by the DIC system to calculate strain and displacement values for the surface subjected to analysis. The obtained data enabled the determination of mechanical parameters such as Young’s modulus (E), flexural strength (Rg) and deflection (f). The DIC system was synchronised with the testing machine force sensor, enabling the analysis of image sequences of the sample corresponding to recorded force values. Observations of changes were performed using two high-resolution DANTEC DYNAMIC cameras (Dantec Dynamics A/S, Skovlunde, Denmark) and two light sources mounted nearby. The calibration of the system and the control of the testing process were performed using the ISTRA 4D software version 16.4. An example of the camera setup is presented in

Figure 4, whereas representative data obtained from the DIC system are shown in

Figure 5.

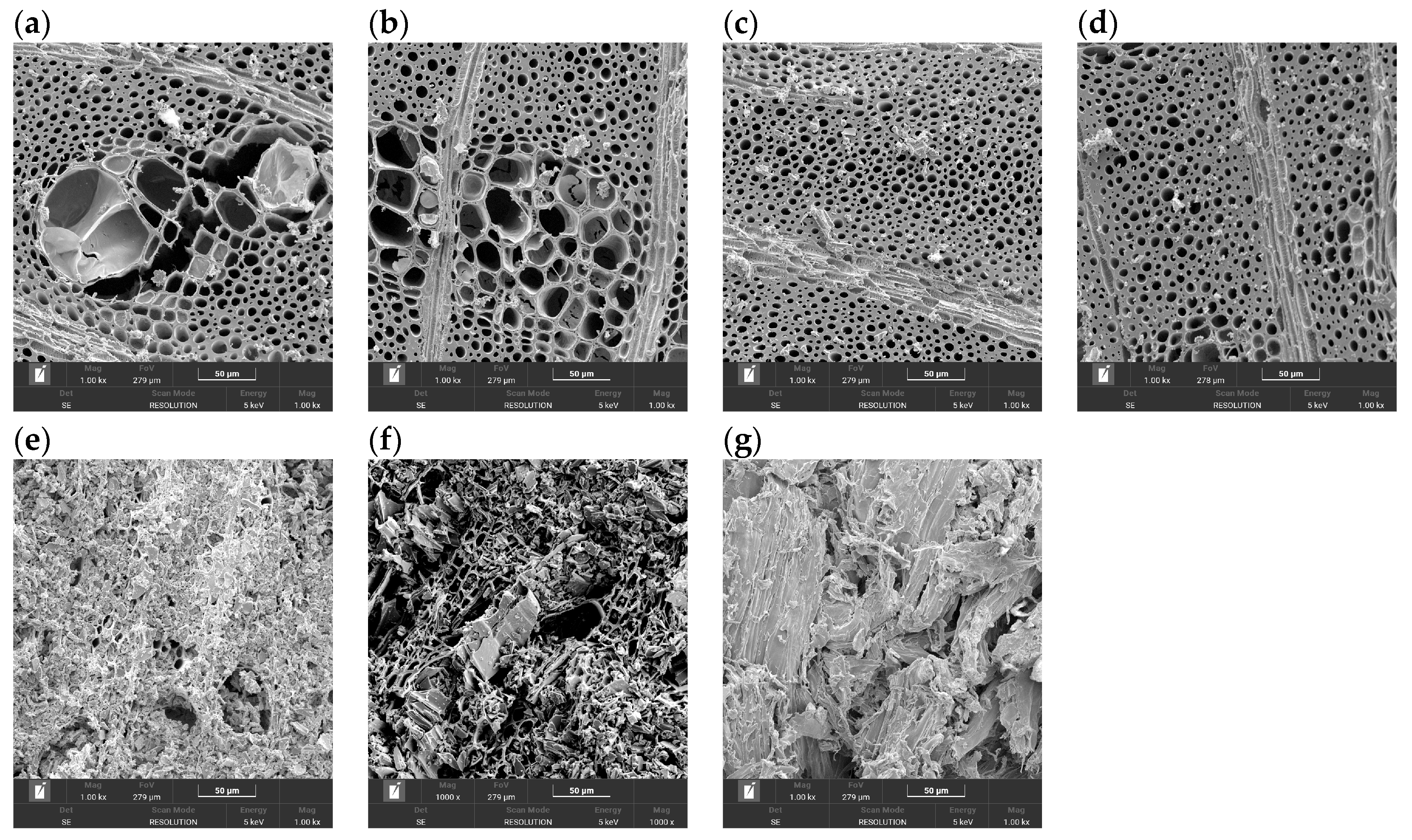

2.5. Microstructural Characterisation (SEM)

The microstructure of the carbonised specimens was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in order to visualise the wood-derived architecture and its evolution with carbonisation temperature and wood species. SEM observations were performed on representative biochars obtained from all investigated wood species (fir, poplar, oak and hornbeam).

In the case of hornbeam, a full temperature series was analysed, including samples carbonised at 400 °C, 600 °C, 800 °C and 1000 °C, to follow the progressive changes in the cellular architecture. In addition, SEM images were acquired for fir, poplar and oak biochars after pyrolysis at 1000 °C in order to compare the microstructure of softwood (fir, poplar) and hardwood (oak, hornbeam) species under identical, high-temperature carbonisation conditions.

For SEM analysis, the specimens were cut or gently fractured to expose longitudinal and transverse sections and then mounted on aluminium stubs using conductive carbon tape. SEM imaging was performed using a Tescan Vega 4 (TESCAN ORSAY HOLDING, Brno, Czech Republic) equipped with an X-ray energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS, Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK). Images were acquired at magnifications of 1000× (and, where necessary, at lower and higher magnifications) to capture both the overall cellular architecture and the finer details of the cell walls and pore structure.

The SEM observations were used qualitatively to confirm the preservation of the hierarchical wood-derived porosity in the biochars and to correlate temperature- and species-dependent changes in cell-wall thickness, pore morphology and microcracking with the mechanical properties obtained from the three-point bending tests.

3. Results

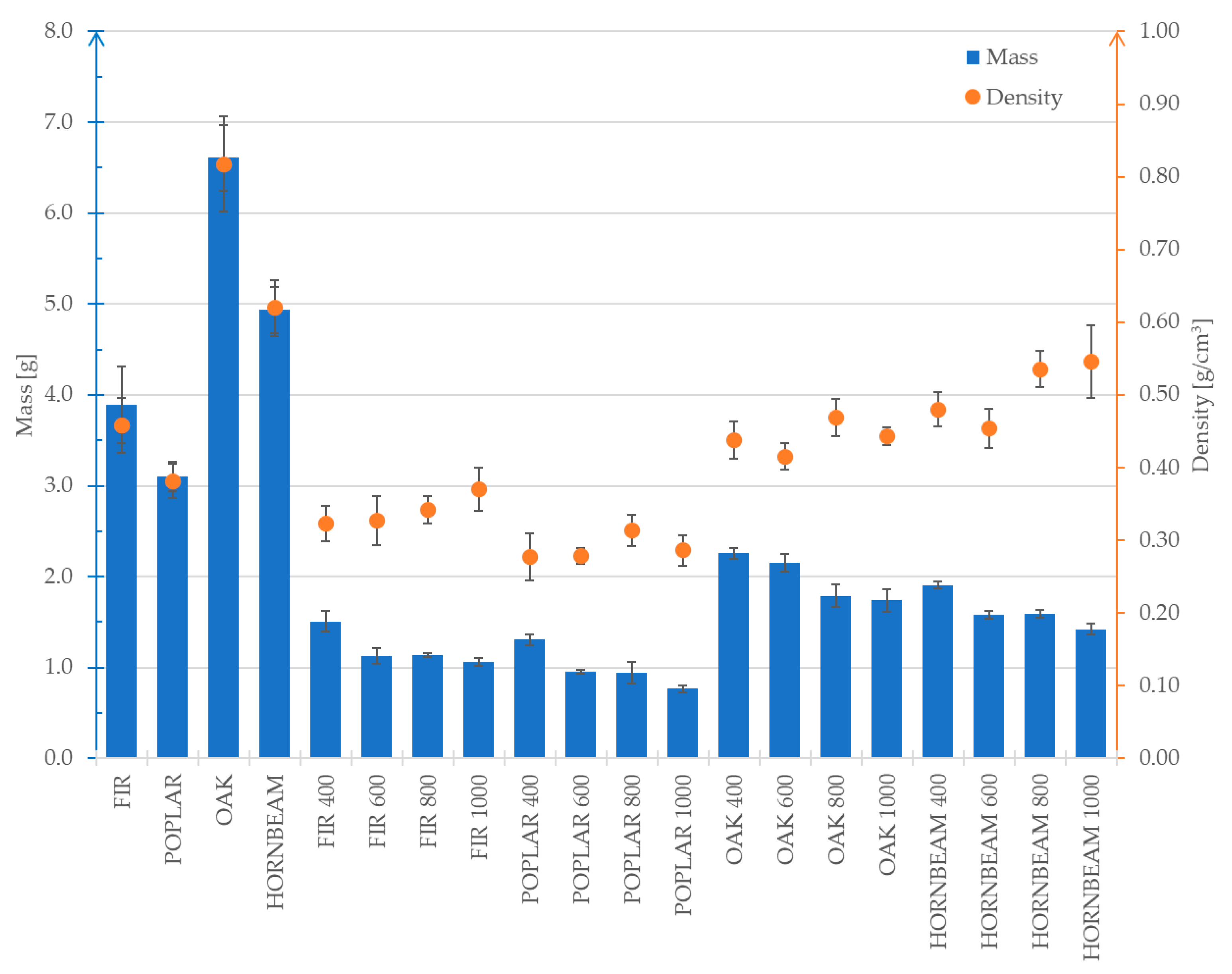

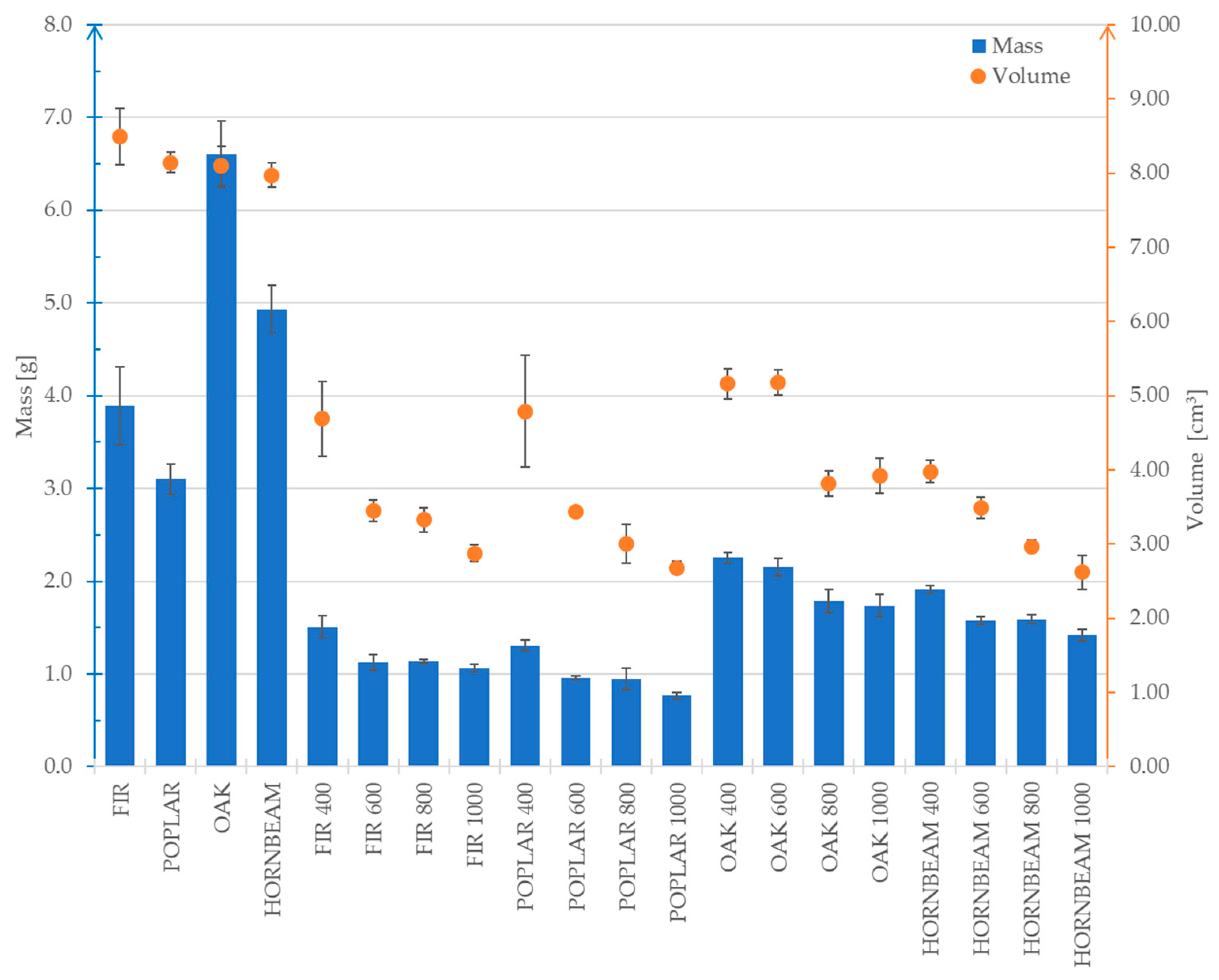

3.1. The Effect of the Pyrolysis Process on the Mass and Density of the Samples

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 presents the average results concerning the changes in mass, volume and density for the analysed wood species. The average measurements of the analysed properties were compiled despite the different initial dimensions of the samples. The purpose was to present changes in these values depending on the pyrolysis temperature to which the samples were subjected.

For all the tested wood species, a significant mass reduction was observed when comparing the raw samples to the biochars. As presented in the diagram in

Figure 7, both mass and volume decrease along with increasing carbonisation temperature. The group of samples designated as POPLAR 1000 was characterised by the greatest mass loss (by 78%) compared to the initial value. The greatest volume reduction (68%) was observed in relation to the HORNBEAM 1000 samples. In turn, the analysis of the diagram in

Figure 6 revealed that the largest decrease in density (47%) was observed in the OAK 600 samples. As regards the OAK samples, it was observed that the decrease in volume was irregular compared to the mass loss (considering all pyrolysis temperatures). This directly affected the changes in the density values and results in their irregular distribution in the diagram in

Figure 7. The fastest volume decrease in relation to mass was observed in the FIR group. This phenomenon results in a significant increase in the density of this species along with a rising pyrolysis temperature. A similar trend was observed in terms of the HORNBEAM group (

Figure 6). The observed changes in mass, volume and density of the samples after pyrolysis are of significant importance in the context of using wood-derived materials as bone substitute materials. The reduction in mass and volume indicates the loss of volatile organic components and remodelling of the material, which contributes to its improved chemical and biological stability, crucial for biomaterials used in implantology and bone reconstruction. At the same time, the increase in density reflects a densification of the material structure, which may lead to enhanced mechanical properties such as compressive strength and strength to three-point bending.

3.2. Microstructural Observations (SEM)

Representative SEM images of hornbeam biochars carbonised at 400 °C, 600 °C, 800 °C and 1000 °C, together with additional images of fir, poplar and oak biochars at 1000 °C, are presented in

Figure 8. For hornbeam at 400 °C, the cellular architecture of the parent wood is largely preserved: the cell walls remain relatively thick and continuous, the lumina are regular and mostly open, and only limited intra-wall porosity or defects can be observed. With increasing carbonisation temperature to 600 °C and 800 °C, the walls gradually become thinner and visually stiffer, the lumina appear more open and elongated, and a larger number of fine micro- and mesopores develops within the walls. At 800 °C, the hornbeam biochars still exhibit a continuous, well-connected carbon skeleton surrounding aligned pores, which provides an efficient load-bearing framework. At 1000 °C, hornbeam biochars maintain this overall framework, but local wall irregularities, pore coalescence and microcracking become more evident, indicating partial degradation of the stiffened carbon structure.

The SEM images of the other wood species at 1000 °C highlight the species-dependent response to high-temperature pyrolysis. In the softwood biochars (fir and poplar), the cell walls appear more strongly thinned and, in some regions, partially fragmented. The pores are larger and more irregular in shape, and microcracks are more frequent than in hornbeam, which indicates a more fragile and anisotropic carbon skeleton. Oak biochar at 1000 °C shows an intermediate morphology: the framework is denser and more continuous than in fir and poplar but still less compact than in hornbeam, with more pronounced wall roughness and local defects. These observations confirm that hardwoods—and hornbeam in particular—preserve a more favourable load-bearing architecture after high-temperature carbonisation than softwoods.

Overall, the SEM observations are consistent with the trends obtained in the mass/density measurements and mechanical tests. Biochars that retain a relatively dense, continuous and well-connected carbon skeleton (especially hornbeam at 800–1000 °C and, to a lesser extent, oak at 1000 °C) exhibit the highest values of Young’s modulus and, at intermediate temperatures, also of flexural strength. In contrast, the pronounced wall thinning, irregular pore enlargement and frequent microcracking observed in softwood biochars at 1000 °C are in line with their more variable and, in some cases, reduced strength despite relatively high stiffness. These findings suggest that not only the overall porosity but also the integrity and connectivity of the cell-wall network are critical determinants of the mechanical performance of plant-derived biochars.

3.3. Results of Three-Point Bending from the MTS Testing Machine

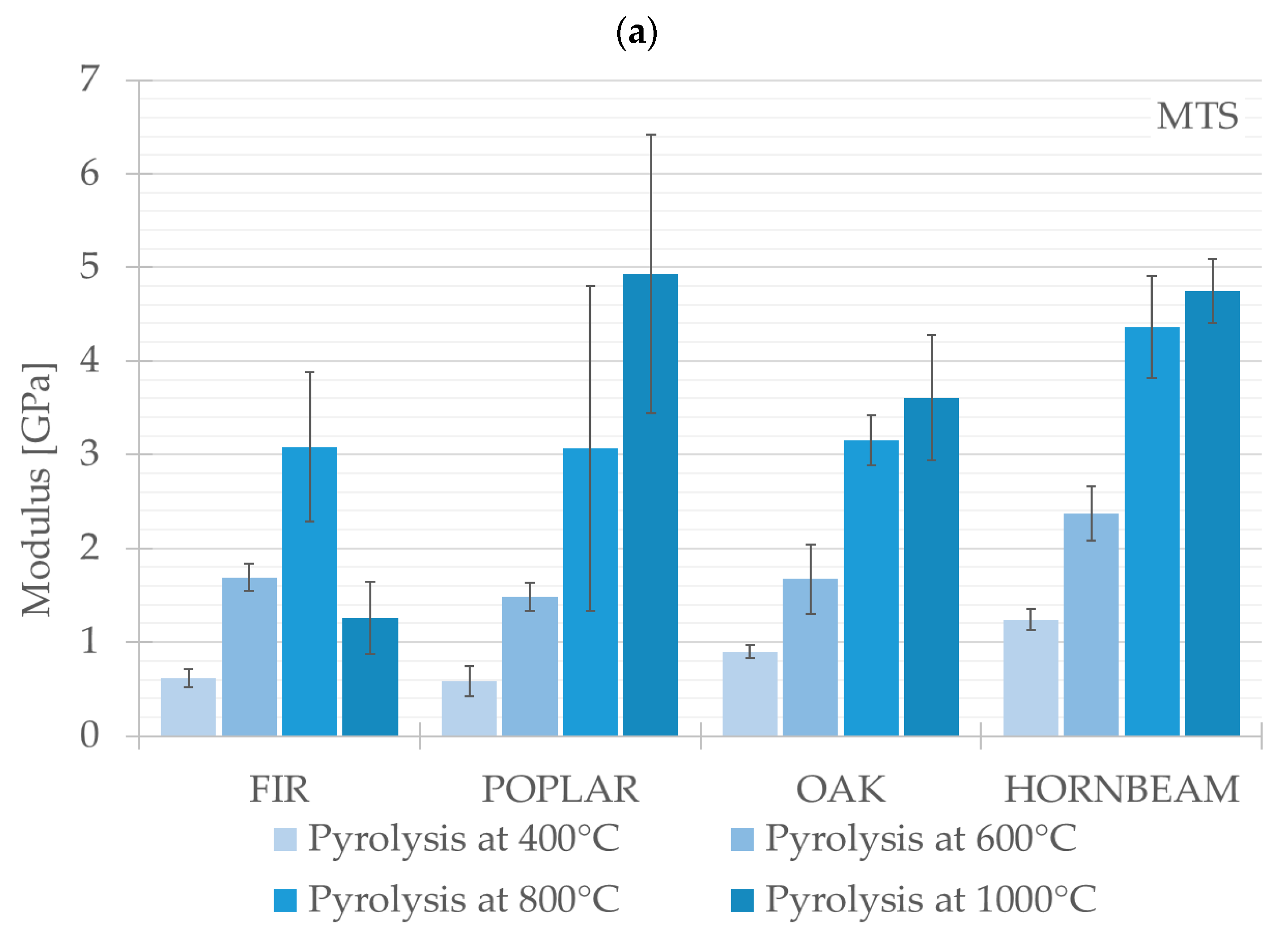

The results of the three-point bending test are presented in this chapter. The compared values constitute average values for each test group (FIR, POPLAR, OAK, HORNBEAM). The authors presented key calculated mechanical properties and parameters obtained from the three-point bending test (Young’s modulus and flexural strength) for the tested wood species and assessed the effect of the pyrolysis process on the changes in such parameters. The graphical changes are presented in

Figure 9a,b.

In terms of Young’s modulus, the highest values were observed in the case of POPLAR, which underwent pyrolysis at 1000 °C, reaching 4.93 ± 1.49 GPa. The analysis of results obtained from the testing machine indicates that, for most of the tested wood species (delivered from POPLAR, OAK, HORNBEAM), Young’s modulus increases along with a rising pyrolysis temperature. At a temperature of 800 °C, the Young modulus values for three species (FIR, POPLAR, OAK) were nearly identical and amounted to approximately 3.15 GPa.

Another parameter subjected to analysis was flexural strength. The highest values for this parameter were observed in relation to HORNBEAM, which underwent pyrolysis at a temperature of 800 °C; the value of flexural strength amounted to 18.66 ± 1.87 MPa. In terms of the group of hardwood species, a temperature of 800 °C was the threshold temperature at which an increase in flexural strength was observed. This increase was also observed as regards the samples from FIR (a softwood species). The second representative of the softwood group (POPLAR) was characterised by the highest flexural strength in the case of samples subjected to pyrolysis at a temperature of 1000 °C. The lowest flexural strength values (amounting to 1.18 ± 0.08 MPa) across all the species and wood types were recorded for the FIR group subjected to pyrolysis performed at a temperature of 1000 °C.

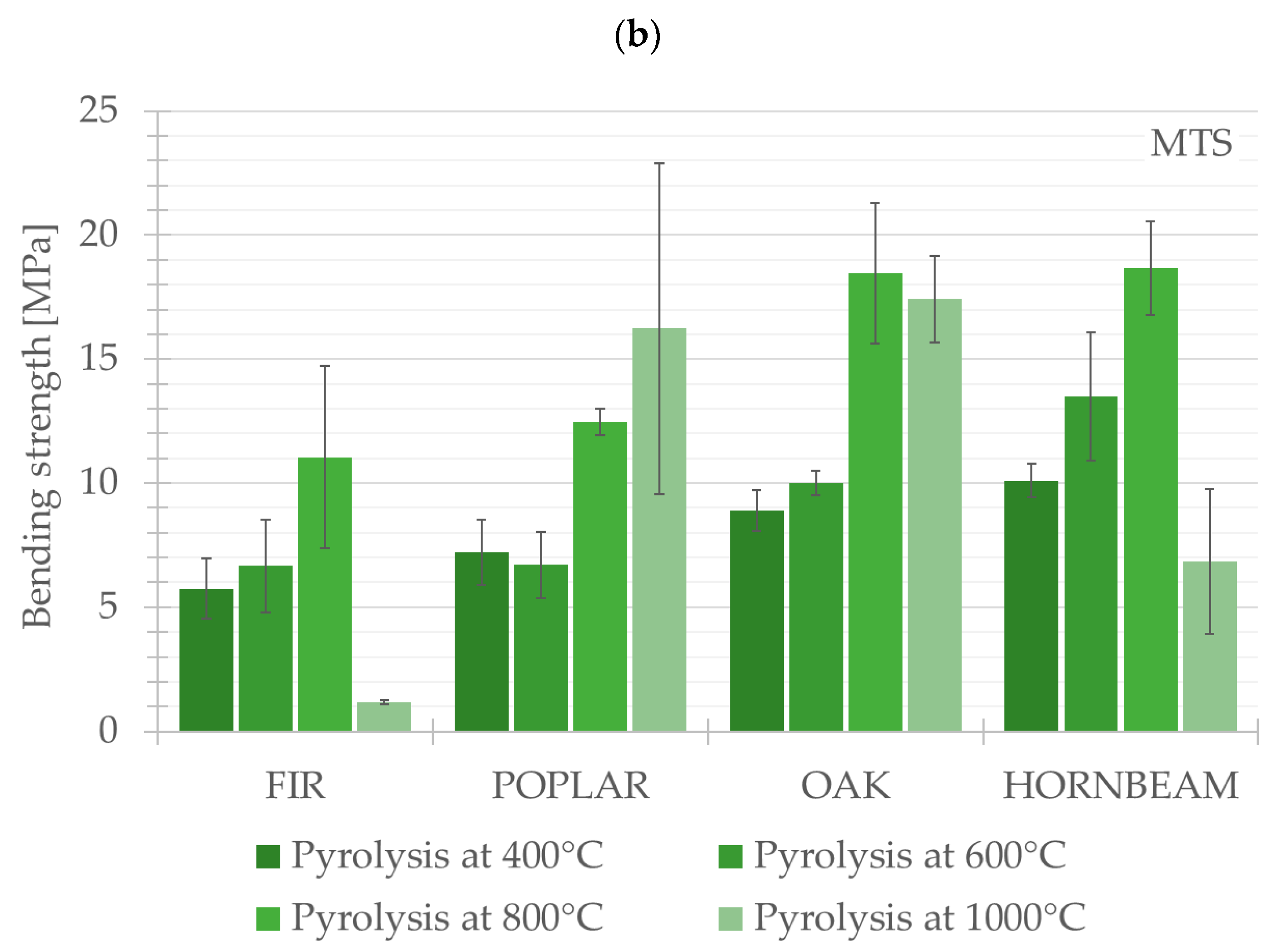

3.4. Results of Three-Point Bending from Digital Image Correlation System

This chapter presents the results of three-point bending tests obtained using the DIC system for all experimental variants—both the raw samples and those subjected to pyrolysis at temperatures ranging from 400 °C to 1000 °C. The values compared are the average values for each tested group and each species (FIR, POPLAR, OAK, HORNBEAM). The key calculated mechanical properties and parameters obtained from the three-point bending tests for the wood species under investigation are presented along with an assessment of the effect of the pyrolysis process on their changes. The changes are illustrated graphically in

Figure 10a,b. The tests revealed differences in the behaviour of softwood species (FIR and POPLAR) compared to hardwood species (OAK and HORNBEAM), with the latter generally demonstrating superior performance, which may be of significance in the context of biomaterial applications.

In terms of Young’s modulus, the highest value, reaching 5.69 ± 0.76 GPa, was observed in relation to HORNBEAM, subjected to pyrolysis at a temperature of 1000 °C. As regards the remaining species, the threshold temperature for an increase in Young’s modulus was 800 °C. Beyond this temperature, it was possible to observe a decrease or stabilisation in Young’s modulus. The foregoing may indicate that excessively high pyrolysis temperatures have a detrimental effect on the material structure, leading to the deterioration of its mechanical properties.

Afterwards, the results obtained for flexural strength were subjected to analysis. The highest value of this parameter, reaching 18.97 ± 2.11 MPa, was observed in relation to HORNBEAM subjected to pyrolysis at a temperature of 800 °C. In turn, the lowest flexural strength, amounting to 1.24 ± 0.09 MPa was observed in relation to FIR subjected to pyrolysis at a temperature of 1000 °C. For the hardwood species group, the threshold temperature at which an increase in flexural strength was observed amounted to 800 °C. This increase was also observed in relation to the samples of FIR (softwood). The other softwood species POPLAR was characterised by the highest flexural strength in the samples subjected to pyrolysis at a temperature of 1000 °C (

Figure 10b).

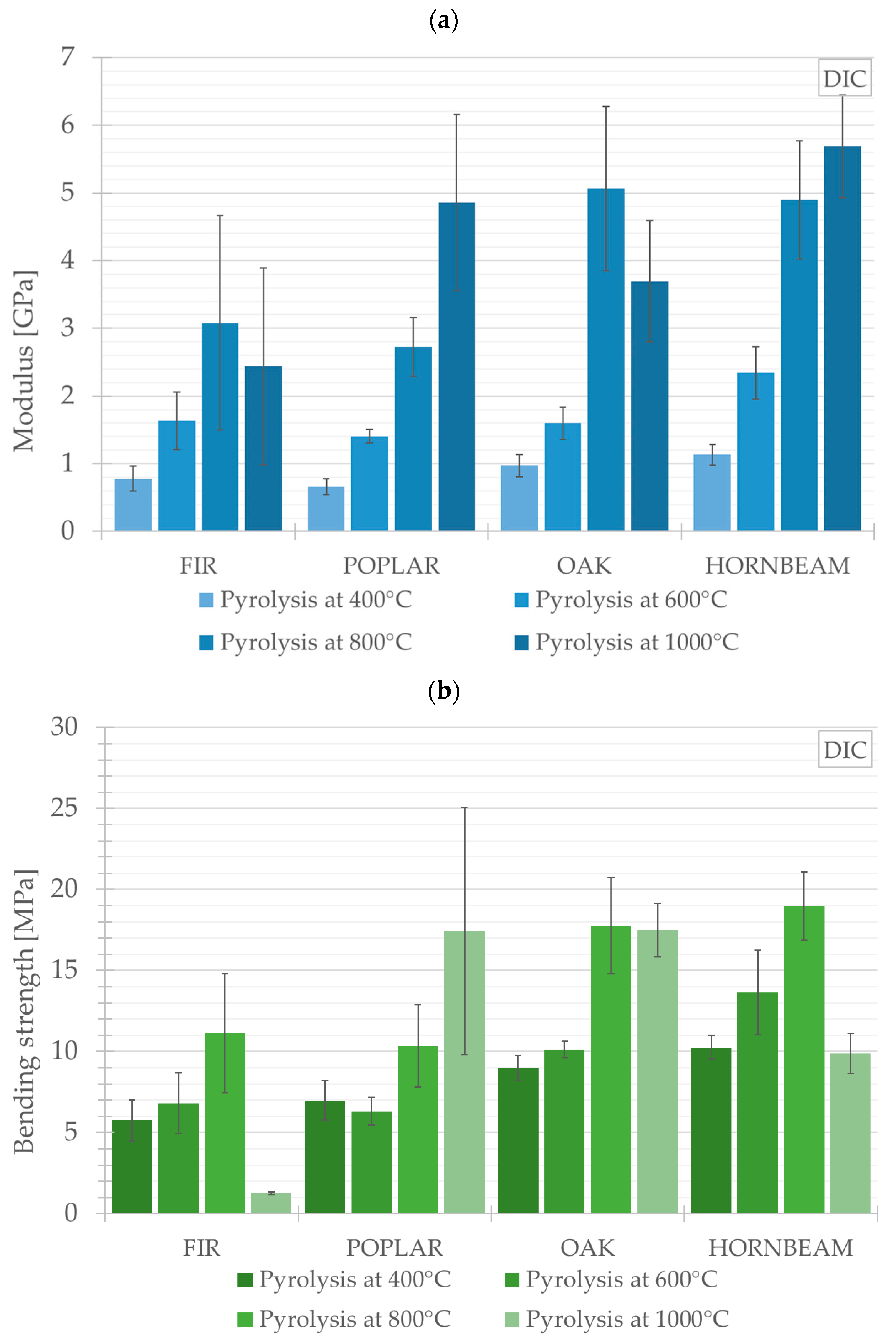

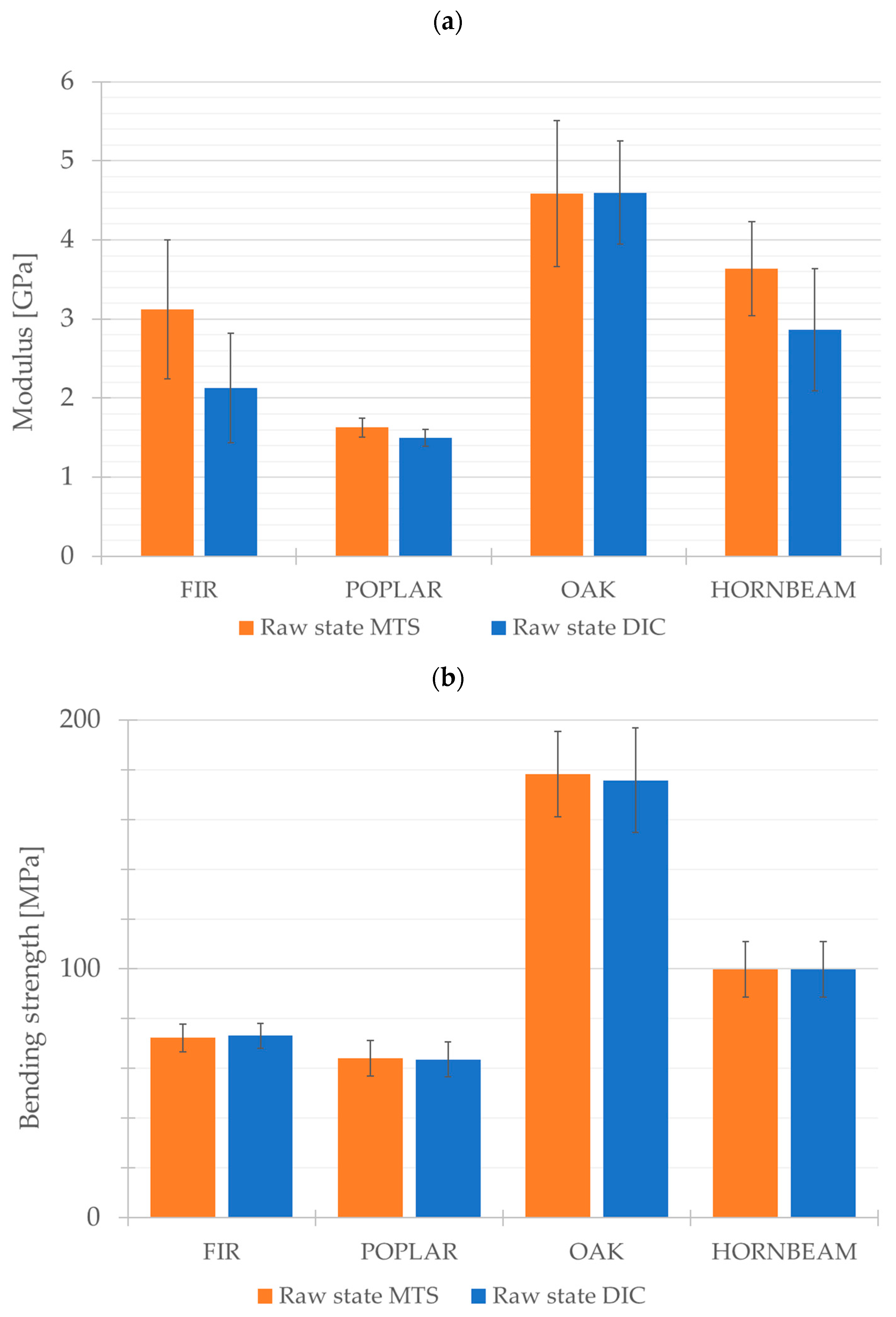

The results obtained using two testing methods, i.e., the materials testing system (MTS) and the Digital Image Correlation system (DIC), revealed strong convergence in the measurements of Young’s modulus and flexural strength (

Figure 11a,b). The comparative analysis of these results suggests that both methods provide consistent data regarding the mechanical properties of the tested materials, confirming the reliability and usefulness of the methods in the evaluation of wood sample properties.

4. Discussion

The present study analysed the potential use of plant-derived biochars as bone substitute materials. Four wood species were investigated and carbonised at different temperatures, and their mechanical behaviour was characterised using a classical three-point bending test combined with Digital Image Correlation (DIC). This approach enabled the simultaneous assessment of global mechanical parameters, such as Young’s modulus and flexural strength, and local displacements and strain distributions on the sample surface, providing a more comprehensive view of the mechanical response of these highly porous materials.

A key outcome of the study is that biochars derived from hornbeam carbonised at 800–1000 °C exhibited the most favourable combination of mechanical properties among all tested materials. The maximum Young’s modulus reached 5.69 ± 0.76 GPa, while the flexural strength amounted to 0.01897 ± 0.00211 GPa. These values are lower than those reported by other researchers for human femoral cortical bone (Young’s modulus: 9.1–21 GPa; flexural strength: 0.103–0.238 GPa [

11,

13,

41,

42,

43,

44]) but comparable to the range reported for ribs (Young’s modulus: 2.79–7.44 GPa; strength: 0.03864–0.08098 GPa [

5,

45,

46,

47]). This indicates that, although hornbeam biochars cannot be considered as direct substitutes for highly loaded long bones, they fall within stiffness ranges that are relevant for less-loaded skeletal elements and thus may be suitable as components of composite or reinforced constructs rather than stand-alone load-bearing implants.

Particular attention was paid to the comparison with the mechanical properties of the mandibular bone, which is clinically relevant in reconstructive and oncological surgery. For the cancellous part of the mandible, Young’s modulus ranges from 0.2 GPa to 2.5 GPa and compressive strength from 0.005 GPa to 0.020 GPa [

26,

48]. The values obtained for the biochars in this study lie within, and in some cases exceed, these ranges, indicating that the materials can safely cover the mechanical requirements of the trabecular component. For the cortical part of the mandible, Young’s modulus typically ranges from 5 GPa to 14 GPa, with compressive strength between 0.040 GPa and 0.120 GPa [

5,

11]. Hornbeam biochars with a Young’s modulus of 5.69 ± 0.76 GPa therefore fall at the lower end of the cortical range, which indicates that they may be suitable for mandibular reconstruction, particularly as hybrid or reinforcing components combined with other biomaterials. From a clinical perspective, a slightly lower stiffness than that of native cortical bone may even be beneficial by reducing stress shielding, provided that the scaffold is adequately supported and integrated with fixation hardware [

11,

13,

41,

42,

43,

44].

Carbonisation temperature had a marked influence on both geometric and mechanical parameters. Increasing the temperature was accompanied by reductions in mass, volume and apparent density, which can be attributed to the removal of volatile components and the reorganisation of the internal structure during pyrolysis. At lower temperatures (400–600 °C), the extent of carbonisation is limited and the remaining organic phase still dominates the behaviour, leading to relatively modest stiffness and strength. Within the 800–1000 °C range, the progressive aromatisation and stiffening of the carbon skeleton lead to a clear increase in Young’s modulus and flexural strength, especially for hardwood species, in line with previous reports on thermally treated and carbonised biomorphic materials [

41,

42,

43,

44]. This indicates that appropriate selection of carbonisation parameters may be used to tailor the physical properties of biochars to match specific biomechanical requirements, but also that there is an upper limit beyond which further increases in temperature may degrade mechanical performance due to excessive porosity and microcracking.

The SEM observations provide a structural explanation for these trends. At 400 °C, the cellular architecture of the parent wood is largely preserved, with relatively thick and continuous cell walls and limited intra-wall porosity. At intermediate temperatures (600–800 °C), the walls become thinner and more carbon-rich, and the lumina open, while micro- and mesopores develop but remain embedded in a continuous framework. For hornbeam, this results in a dense and well-connected load-bearing skeleton surrounding elongated pores, which is consistent with the high stiffness and flexural strength obtained at 800 °C. At 1000 °C, further thinning of the walls and the appearance of more pronounced microcracking and pore coalescence are observed, particularly in softwood biochars. This reduces the effective load-bearing cross section and explains why, for some species, the flexural strength does not increase further or even decreases at 1000 °C, despite a continued increase in stiffness. Overall, the microstructural data confirm that not only the overall porosity, but also the integrity and connectivity of the cell-wall network, are critical determinants of mechanical performance.

The convergence of results obtained with the MTS testing machine and the DIC system confirms the reliability of the mechanical characterisation. Both techniques revealed similar trends in the variation in Young’s modulus and flexural strength with wood species and carbonisation temperature, and the differences in absolute values generally remained within one standard deviation. At the same time, the two methods provide complementary information. The MTS-based measurements capture the global load–displacement response and are slightly affected by the compliance of the testing setup. In contrast, DIC yields local strain maps on the tensile surface and is sensitive to microstructural heterogeneity, imperfections and the choice of the region of interest. Small discrepancies between MTS and DIC values can therefore be explained by these methodological differences rather than by inconsistencies in material behaviour. In addition, DIC enables the identification of local strain concentrations that may act as initiation sites for damage and failure, which is particularly valuable for the design of biomimetic scaffolds with graded properties.

From the perspective of bone tissue engineering, the naturally porous architecture of plant-derived biochars favours tissue ingrowth and vascularisation. The preserved, anisotropic channel structure mimics the organisation of trabecular bone and may facilitate directional transport of fluids and cells, which is considered advantageous for scaffold performance [

11,

13,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Although the mechanical properties of the materials investigated here are somewhat lower than those of dense cortical bone, they appear sufficient for reconstructing regions subjected to limited or moderate functional loading, such as ribs, scapula, parts of the pelvis or mandibular segments. Their lower stiffness, closer to that of bone, may also help to mitigate stress shielding phenomena that are often observed with metallic implants, especially if biochars are used as fillers or internal scaffolds in composite systems.

At the same time, several important limitations and open questions must be acknowledged. First, the present work focused exclusively on mechanical and basic geometrical and microstructural characterisation; no in vitro or in vivo biocompatibility data were included. Systematic studies of cytocompatibility and cytotoxicity, as well as long-term degradation behaviour in the presence of body fluids and inflammatory mediators, are necessary before clinical translation can be considered. Second, a more detailed three-dimensional analysis of the microstructure is needed to fully understand the relationship between carbonisation temperature, porosity, pore architecture and mechanical performance. Techniques such as micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), combined with quantitative assessment of porosity, absorbency and ionic conductivity, would provide deeper insight into structure–property relationships.

In addition, spectroscopic studies (e.g., FTIR, Raman) could help to characterise the chemical nature of the residual organic phase and surface functional groups, which is crucial for predicting bioactivity and interactions with cells. Surface properties, chemical stability and the feasibility of sterilisation without compromising structural integrity or functional parameters should also be carefully evaluated. Future work should therefore focus on the development of strategies for surface functionalisation of biochars, aimed at enhancing osteoblast differentiation, osteointegration and angiogenesis under both in vitro and in vivo conditions. Optimising pore size and shape, as well as adjusting stiffness to match the surrounding bone, may further improve graft integration and functionality. The incorporation of growth factors, adhesive peptides or bioactive ceramic phases could extend the application of biochars towards advanced regenerative therapies. Equally important will be the development of shaping and machining technologies that allow the production of patient-specific implants and composite constructs.

Overall, plant-derived biochars can be regarded as interdisciplinary materials combining biologically inspired structure with tuneable mechanical properties. Their relatively low cost, environmental friendliness and the possibility of local production further increase their attractiveness as candidates for next-generation biomaterials, provided that future work confirms their long-term safety and biological performance.

5. Conclusions

In this study, plant-derived biochars obtained from different wood species and carbonised at temperatures between 400 °C and 1000 °C were mechanically characterised with respect to their potential application as bone graft substitutes. Mechanical testing combined a classical three-point bending configuration with Digital Image Correlation, enabling the determination of both global strength parameters and local deformation fields.

Among all investigated materials, hornbeam biochars carbonised at 800–1000 °C exhibited the most favourable combination of properties. The highest Young’s modulus, 5.69 ± 0.76 GPa, and flexural strength, 0.01897 ± 0.00211 GPa, place these biochars within the range reported for cancellous bone and at the lower end of the range for cortical mandibular bone. This suggests that such biochars may be suitable for reconstruction of skeletal regions subjected to limited or moderate functional loading, such as ribs, scapula, pelvic bones or mandibular segments, particularly as part of hybrid constructs.

The study confirmed a strong influence of carbonisation temperature on mass, density and mechanical behaviour. Increasing temperature led to pronounced mass and volume loss, but within the 800–1000 °C range it also resulted in increased stiffness and, for hardwood species, improved flexural strength, demonstrating that the physical properties of biochars can be tuned by adjusting pyrolysis parameters. The good agreement between mechanical parameters obtained from the MTS machine and the DIC system supports the reliability of the proposed characterisation protocol and shows the benefit of combining global and local measurement techniques.

Overall, lignocellulose-derived biochars subjected to appropriate heat treatment exhibit a set of features desirable from the perspective of bone tissue engineering: controlled, bone-like porosity, adequate mechanical stability, mechanical properties comparable to those of selected bone tissues and susceptibility to further modification. With their natural origin, wide availability and potential for surface and microstructural engineering, they represent a promising alternative or complement to existing ceramic and polymer scaffolds. Nevertheless, comprehensive microstructural and biological studies, including in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility and degradation assessments, are essential before these materials can be considered for clinical use.