Therapeutic Potential of Flavonoids—The Use of Apigenin in Medicine

Abstract

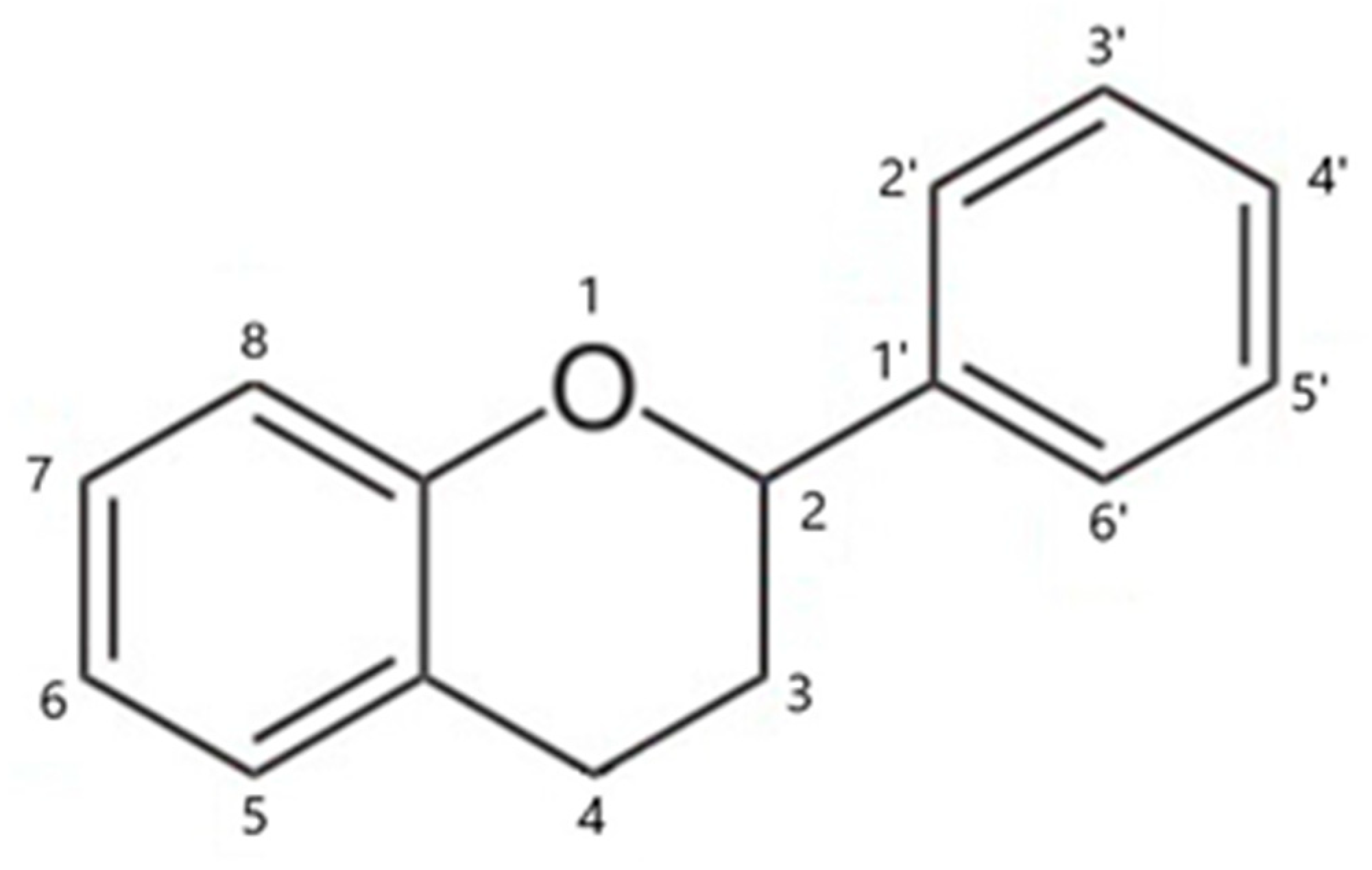

1. Introduction

- –

- Flavones—e.g., apigenin, luteolin, diosmetin;

- –

- Isoflavones—e.g., genisgtein, daidzein;

- –

- Flavonols—e.g., quercetin, myricetin, morin, kemferol, fistein;

- –

- Flavanones—e.g., hesperetin, hesperedin, nerygenin, naringenin;

- –

- Flavanols—e.g., catechin, epigallocatechin, epicatechin;

- –

- Anthocyanins—e.g., cyanidin, malvidin, pelargonidin;

- –

- Biflavonoids—e.g., ginkgetin;

- –

- Flavonoglycans—e.g., silybin;

- –

- Chalcones—e.g., phloretin.

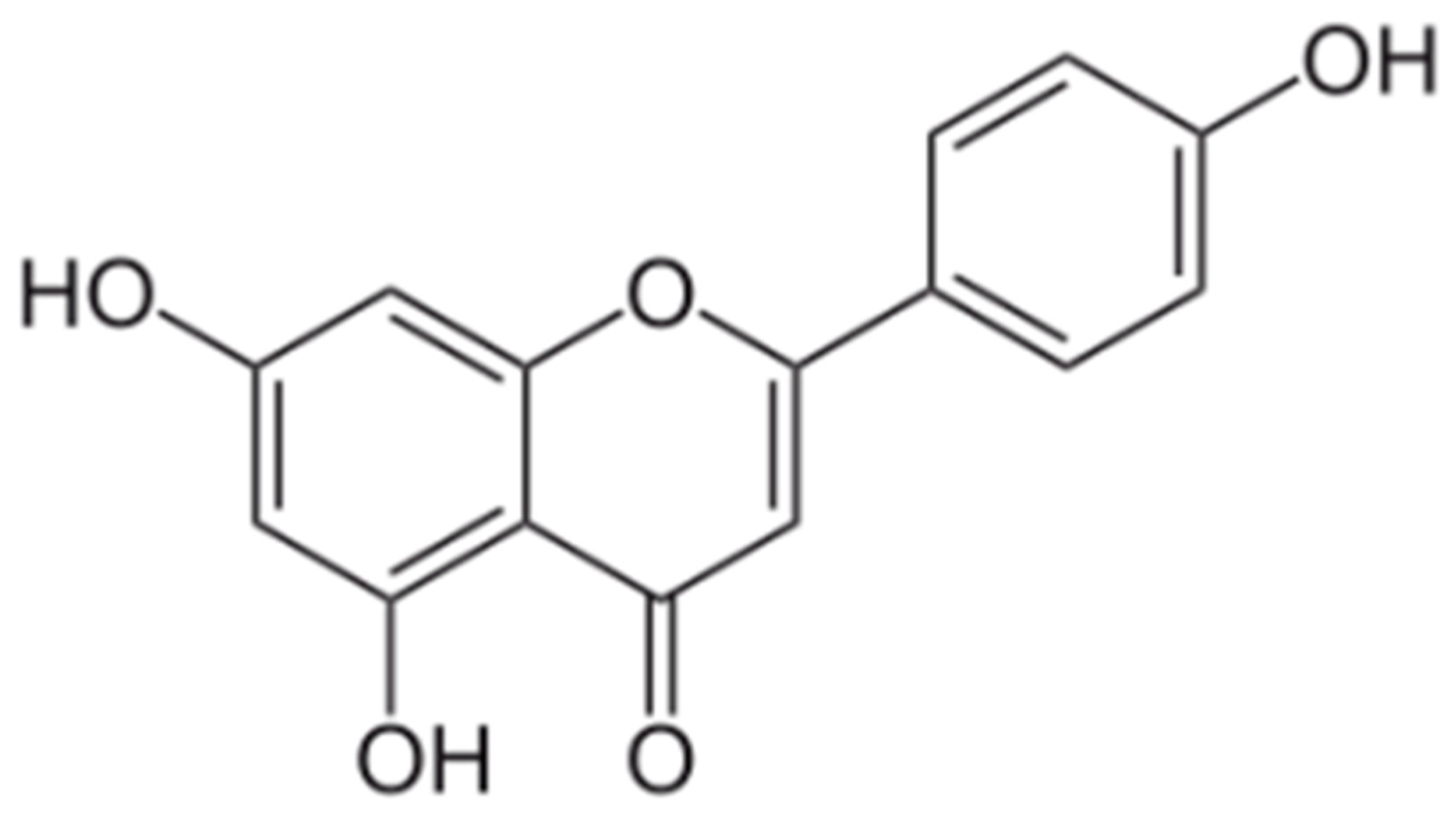

2. Apigenin

3. The Use of Apigenin in Medicine

3.1. Antioxidant Effect

3.2. Anticancer Effect

3.3. Antiallergic Effect

3.4. Effects in Cardiology

3.5. Effects in Orthopedics

3.6. Effects in Neurology

3.6.1. Alzheimer’s Disease

3.6.2. Monoamines (MAO)

3.6.3. Memory Problems

3.6.4. Anxiety Disorders and Depression

3.6.5. Insomnia

3.7. Antidiabetic Effect

3.8. Antiviral Effects

3.9. Antibacterial Effects

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jasiński, M.; Mazurkiewicz, E.; Rodzewicz, P.; Figlerowicz, M. Flavonoids’ structure, properties and particular function for legume plants. Biotechnologia 2009, 2, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Pandey, A.K. Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 162750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majewska, M.; Czeczot, H. Flavonoids in prevention and therapy of diseases. Ter. I Leki 2009, 65, 369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Waszkiewicz-Robak, B. The content of polyphenolic compounds in raw materials and in processed food–A review. Technol. Prog. Food Process. 2021, 2, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodowska, K.M. Natural flavonoids: Classification, potential role, and application of flavonoid analogues. Eur. J. Biol. Res. 2017, 7, 108–123. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiquee, R.; Mahmood, T.; Ansari, V.A.; Ahsan, F.; Bano, S. Apigenin unveiled: An encyclopedic review of its preclinical and clinical insights. Discov. Plants 2025, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R. Selected aspects of the biological activity of flavonoids. Ann. UMCS 2016, XXVI, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Znajdek-Awiżeń, P. Phytochemical Studies on the Herb of Axyris amaranthoides L. Ph.D. Thesis, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznań, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kałwa, K. Antioxidant properties of flavonoids and their impact on human health. Kosm. Probl. Nauk. Biol. 2019, 1, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosiak, N.; Tykarska, E.; Miklaszewski, A.; Pietrzak, R.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Enhancing the Solubility and Dissolution of Apigenin: Solid Dispersions Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hołderna-Kędzia, E. Antibacterial activity of ethanolic extracts of propolis (EEP). Post. Fitoter. 2022, 23, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewska, P.; Skrzypczak, N. Moda na flawonoidy–o co tyle szumu? Tutoring Gedanensis 2021, 6, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Sahu, P.K.; Haldar, R.; Sahu, K.K.; Prasad, P.; Roy, A. Apigenin Naturally Occurring Flavonoids: Occurrence and Bioactivity. UK J. Pharm. Biosci. 2016, 4, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Venditti, A.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Kręgiel, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Santini, A.; Souto, E.B.; Novellino, E.; et al. The Therapeutic Potential of Apigenin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.B.; Fatima, F.; Ahmed, M.M.; Aldawsari, M.F.; Alalaiwe, A.; Anwer, M.K.; Mohammed, A.A. Enhanced Apigenin Dissolution and Effectiveness Using Glycyrrhizin Spray-Dried Solid Dispersions Filled in 3D-Printed Tablets. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeleszczuk, Ł.; Zielińska-Pisklak, M.; Młodzianka, A. Perilla frutescens—Niezwykłe właściwości pachnotki zwyczajnej. Lek. W Polsce 2013, 23, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.; Lozano, Y.F.; Gaydou, E.M.; Li, B. Antioxidant activities of polyphenols extracted from Perilla frutescens varieties. Molecules 2009, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailović, V.; Katanić Stanković, J.S.; Jurić, T.; Srećkowić, N.; Misić, D.; Siler, B.; Monti, D.M.; Imbimbo, P.; Nikles, S.; Pan, S.-P.; et al. Blackstonia perfoliata (L.) Huds. (Gentianaceae): A promising source of useful bioactive compounds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 145, 111974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scimone, G.; Carucci, M.G.; Risoli, S.; Pisuttu, C.; Cotrozzi, L.; Lorenzini, G.; Nali, C.; Pellegrini, E.; Petersen, M. Ozone Treatment as an Approach to Induce Specialized Compounds in Melissa officinalis Plants. Plants 2024, 13, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.; Yamashita, M.; Iguchi, S.; Kihara, T.; Kamon, E.; Ishikawa, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Ishimizu, T. Biochemical Characterization of Parsley Glycosyltransferases Involved in the Biosynthesis of a Flavonoid Glycoside, Apiin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvan, S.; Manoharan, S.; Baskaran, N.; Anusuya, C.; Karthikeyan, S.; Prabhakar, M.M. Chemopreventive potential of apigenin in 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene induced experimental oral carcinogenesis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 670, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golonko, A.; Olichwier, A.J.; Szklaruk, A.; Paszko, A.; Świsłocka, R.; Szczerbiński, Ł.; Lewandowski, W. Apigenin’s Modulation of Doxorubicin Efficacy in Breast Cancer. Molecules 2024, 29, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Peng, L.; Cao, T.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Liu, Y. Apigenin inhibits the proliferation and aerobic glycolysis of endometrial cancer cells by regulating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2024, 45, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Bhaskaran, N.; Babcook, M.A.; Fu, P.; Maclennan, G.T.; Gupta, S. inhibits prostate cancer progression in TRAMP mice via targeting PI3K/Akt/FoxO pathway. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh, K.; Dizaji, S.R.; Ramezani, F.; Imani, F.; Shamseddin, J.; Sarveazad, A.; Yousefifard, M. Potential therapeutic effects of apigenin for colorectal adenocarcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, 70171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrott, K.M.; Wiley, C.D.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Campisi, J. Apigenin suppresses the senescence-associated secretory phenotype and paracrine effects on breast cancer cells. Geroscience 2017, 39, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domino, M. Enatolowy Ekstrakt Propolisu (EEP) Jako Stymulator Apoptozy Indukowanej w Komórkach Nowotworowych HeLa. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Medical Sciences in Zabrze, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Zabrze, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Golonko, A.; Kalinowska, M.; Świsłocka, R.; Świderski, G.; Lewandowski, W. Applications of phenolic compounds and their derivatives in industry and medicine. Civ. Environ. Eng. Bud. I Inżynieria Sr. 2015, 6, 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Gołąb, J.; Nowis, D.; Lasek, W.; Stokłosa, T. Immunologia. Wydawnictwo Naukowe; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, H. Apigenin attenuates inflammatory response in allergic rhinitis mice by inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. Environ. Toxicol. 2023, 38, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Huang, X.; Zhu, H.-H.; Wang, N.; Xie, C.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Shi, H.-L.; Chen, M.-M.; Wu, Y.-R.; Ruan, Z.-H.; et al. Apigenin ameliorates non-eosinophilic inflammation, dysregulated immune homeostasis and mitochondria-mediated airway epithelial cell apoptosis in chronic obese asthma via the ROS-ASK1-MAPK pathway. Phytomedicine 2023, 111, 154646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Fan, Z.; Han, S.; Sun, N.; Che, H. Apigenin Attenuates the Allergic Reactions by Competitively Binding to ER With Estradiol. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 16, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Nunez, L.; Rivera, J.; Guerrero, J.A.; Martinez, C.; Vicente, V.; Lozano, M.L. Differential effects of quercetin, apigenin and genistein on signalling pathways of protease-activated receptors PAR(1) and PAR(4) in platelets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 158, 1548–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Xu, A.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Fu, R.; Jiang, W.; Li, X. Fabrication of apigenin and adenosine loaded nanoparticles against doxorubicin induced myocardial infarction by reducing inflammation and oxidative stress. BMC Biotechnol. 2024, 24, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Nunez, L.; Lozano, M.L.; Palomo, M.; Vicente, V.; Castillo, J.; Benavente-Garcia, O.; Diaz-Ricart, M.; Escolar, G.; Rivera, J. Apigenin inhibits platelet adhesion and thrombus formation and synergizes with aspirin in the suppression of the arachidonic acid pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 2970–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Jun, F.; Chen, H.; Ke-Jing, Y.; Jian, H.; Xiao-Yan, D. Hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects of total flavonoids of Perilla Frutescens leaves in hyperlipidemia rats induced by high-fat diet. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, M.; He, D.; Ru, X.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Y.; Bruce, I.C.; Xia, Q.; Yao, X.; Jin, J. Apigenin, a plant-derived flavone, activates transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 cation channel. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 166, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroczek, J. Zastosowanie Apigeniny Jako Modulatora Procesu Mineralizacji Zachodzącego w Pęcherzykach Macierzy Pozakomórkowej Wydzielanych Przez Komórki Kości Człowieka. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Chemistry, University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Briolay, A.; Bessueille, L.; Magne, D. TNAP: A New Multitask Enzyme in Energy Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Conor, C.J.; Leddy, H.A.; Benefield, H.C.; Liedtke, W.B.; Guilaj, F. TRPV4-mediated mechanotransduction regulates the metabolic response of chondrocytes to dynamic loading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 1316–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoara, R.; Hashempur, M.H.; Ashraf, A.; Salehi, A.; Dehshahri, S.; Habibagahi, Z. Efficacy and safety of topical Matricaria chamomilla L. (chamomile) oil for knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2015, 21, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Du, W.; Che, W.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L. Apigenin Inhibits the Progression of Osteoarthritis by Mediating Macrophage Polarization. Molecules 2023, 28, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, J.-L.; Liu, R.; Li, X.-X.; Li, J.-F.; Zhang, L. Neuroprotective, anti-amyloidogenic and neurotrophic effects of apigenin in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Molecules 2013, 18, 9949–9965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balez, R.; Steiner, N.; Engel, M.; Munoz, S.S.; Lum, J.S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, D.; Vallotton, P.; Sachdev, P.; O’Connor, M.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of apigenin against inflammation, neuronal excitability and apoptosis in an induced pluripotent stem cell model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Qin, G.W.; Wang, J.; Chu, W.-J.; Guo, L.-H. Functional activation of monoamine transporters by luteolin and apigenin isolated from the fruit of Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. Neurochem. Int. 2010, 56, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo, P.S.; Rubio, M.C.; Medina, J.H.; Adler-Graschińsky, E. Involvement of monoamine oxidase and noradrenaline uptake in the positive chronotropic effects of apigenin in rat atria. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996, 312, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; He, M.; Lee, A.; Cho, E. Apigenin Ameliorates Scopolamine-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction and Neuronal Damage in Mice. Molecules 2021, 26, 5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, N.H.; Awad, M.M.; El-Shaer, R.A.; Ibrahim, H.A.M.; Ibrahim, S.; AbuoHashish, N.A.; El-Khalik, S.R.A. Anti-Aging Effect Of Apigenin Through Modulating Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Cellular Senescence, And miR-34a In D-Galactose Induced Brain Aging In Mice. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2025, 101, 5142–5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.J.; Xie, S.X.; Keefe, J.R.; Soeller, I.; Li, Q.S.; Amsterdam, J.D. Long-term chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 1735–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsterdam, J.D.; Shults, J.; Soeller, I.I.; Mao, J.J.; Rockwell, K.; Newberg, A.B. Chamomile (Matricaria recutita) may provide antidepressant activity in anxious, depressed humans: An exploratory study. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2012, 18, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Zhao, D.; Qu, R.; Fu, Q.; Ma, S. The effects of apigenin on lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 594, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zick, S.M.; Wright, B.D.; Sen, A.; Arnedt, T. Preliminary examination of the efficacy and safety of a standardized chamomile extract for chronic primary insomnia: A randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D.J.; Johnson, A.A. Apigenin: A natural molecule at the intersection of sleep and aging. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1359176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Kar, A. Apigenin (4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavone) regulates hyperglycaemia, thyroid dysfunction and lipid peroxidation in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2007, 59, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihim, S.A.; Kaneko, Y.K.; Yamamoto, M.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kimura, T.; Ishikawa, T. Apigenin Alleviates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Apoptosis in INS-1 β-Cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2023, 46, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, F.; Hameed, A.; Ali, A.; Imad, R.; Hafizur, R.M. Apigenin potentiates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion through the PKA-MEK kinase signaling pathway independent of K-ATP channels. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 116986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Bi, J.; Li, F.; Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Meng, X.; Sun, B.; Wang, D.; Kong, W.; Jiang, C.; et al. Antiviral Efficacy of Flavonoids against Enterovirus 71 Infection in vitro and in Newborn Mice. Viruses 2019, 11, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.; Fang, C.Y.; Cheng, Y.-J.; Hsu, H.-Y.; Chou, S.-P.; Huang, S.-Y.; Tsai, C.-H.; Chen, J.-Y. Inhibition of Epstein-Barr virus reactivation by the flavonoid apigenin. J. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, C.; Ohno, M.; Otsuka, M.; Kishikawa, T.; Goto, K.; Muroyama, R.; Kato, N.; Yoshikawa, T.; Takata, A.; Koike, K. The flavonoid apigenin inhibits hepatitis C virus replication by decreasing mature microRNA122 levels. Virology 2014, 462–463, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales, A.; Lin, E.; Stoffel, V.; Dickson, S.; Khan, Z.K.; Beld, J.; Jain, P. Apigenin improves cytotoxicity of antiretroviral drugs against HTLV-1 infected cells through the modulation of AhR signaling. NeuroImmune Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 2, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Peng, W.; Kou, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L. High-throughput screening identification of apigenin that reverses the colistin resistance of mcr-1-positive pathogens. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0034124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegazi, A.; Abd El-Moez, S.I.; Abd Allah, A.A.F. Antibacterial Activity of Some Types of Monofloral Honey Against Clostridium acetobutylicum and Clostridium perfringens. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 552–565. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Y.; Li, C.; Dai, W.; Lou, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Khan, A.A.; Wan, C. The Anti-Biofilm Activity and Mechanism of Apigenin-7-O-Glucoside Against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 2129–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafar, M.; Khan, M.S.A.; Salahuddin, M.; Zahoor, S.; Slais, H.M.; Alalwan, L.I.; Alshaban, H.R. Development of apigenin loaded gastroretentive microsponge for the targeting of Helicobacter pylori. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors | Model/Method | Cell Line | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meng et al. [18] | Perilla frutescens extract | In vitro (DPPH assay) | Antioxidant activity; apigenin identified as one of four compounds with highest radical scavenging potential |

| Salehi et al. [15] | Review | Various cell models | Anti-oxidative stress increases expression of catalase, GSH-synthase; upregulates Phase II enzymes via Nrf2 activation and NADPH oxidase inhibition |

| Mihailović et al. [19] | Blackstonia perfoliata methanol extract | In vitro | Anti-inflammatory (COX-1/COX-2 inhibition), moderate antioxidant activity, inhibition of lipid peroxidation, antifungal > antibacterial activity; apigenin contributes synergistically with other secondary metabolites |

| Scimone et al. [20] | Melissa officinalis (lemon balm) | Plant model | Ozone elicitation increased apigenin content (~48–93% increase in flavonoids), enhanced PAL activity; increased total antioxidant activity up to 3× control |

| Song An et al. [21] | Petroselinum crispum (parsley) | Plant tissue/enzymatic study | Apiin (apigenin glycoside) biosynthesis via glucosyltransferase and apiosyltransferase; apigenin exerts anti-inflammatory (NF-κB inhibition, cytokine reduction) and antioxidant effects; supports cardiovascular, lipid metabolism, and immune function; potential for nutraceutical/phytotherapeutic use |

| Authors | Model | Cancer Type/Cells | Dose of Apigenin | Mechanism/Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salehi et al. [15] | In vitro human cell cultures | Various cancer cell lines | – | Cell cycle stopped in G1/S and G2/M; activation of caspase 3 and 8; regulation of PI3K/Akt, p38/MAPK, ERK, COX-2, Bax, STAT-3, Bcl-2. |

| Silvan et al. [22] | In vivo (hamsters) | DMBA-induced buccal pouch carcinoma | 2.5 mg/kg body weight | Prevented tumor formation; only mild dysplasia and hyperplasia observed; no full carcinogenesis. |

| Golonko et al. [23] | In vitro | MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 | 12.5–200 µM; synergistic effects mainly at 25–100 µM | When api was combined with DOX, a strong synergistic effect was observed, reducing the IC50 of both compounds. Api inhibited cell migration and increased lipid droplet accumulation in TNBC. |

| Li Xu et al. [24] | In vitro | HEC-1A | 0–40 µmol of apigenin | Apigenin inhibited the proliferation of endometrial cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner and enhanced apoptosis by increasing the expression of BAX and Cleaved Caspase-3 and downregulating BCL-2. Additionally, it reduced aerobic glycolysis, reducing glucose consumption, lactate production, and ATP levels by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. |

| Shukla et al. [25] | In vivo (TRAMP mice) | Prostate cancer | 20 µg or 50 µg daily for 20 weeks | Reduced tumor volume and metastasis; decreased genitourinary mass; modulated PI3K/Akt/FoxO3a and IGF-I signaling. |

| Ahmadzadeh et al. [26] | Meta-analysis In vitro and in vivo | Colon cancer | - | Apigenin significantly inhibited the proliferation and growth of colon cancer cells, induced apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase in vitro. In animal models, it reduced tumor size without significant toxicity or impact on body weight. |

| Perrot et al. [27] | In vitro | human fibroblasts and breast cancer cells) | – | Inhibited SASP via MAPK and IL-1 suppression; reduced inflammatory phenotype. |

| Domino [28] | In vitro (HeLa ACC 57) | Cervical cancer | Ethanolic propolis extract containing apigenin | MTT, LDH, and TRAIL assays showed strong cytotoxicity; enhanced apoptosis with TRAIL. |

| Author | Model/Method | Main Findings/Doses | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Navarro-Nunez et al. [34] | Radioligand binding assay with 125I-thrombin, platelet aggregation tests | Apigenin, quercetin, genistein impair platelet aggregation and 5-HT release. Apigenin in doses 0–100 µM. | Apigenin acts as protein kinase inhibitors or disrupt platelet intracellular signaling; do not directly bind thrombin receptors. |

| Li et al. [35] | Development and evaluation of nanoparticles with apigenin (AP) and adenosine (AD) for the treatment of cardiac injury induced by myocardial infarction (MI) in rats | DOX in dose 85 mg/kg. AP + AD in doses 5 mg/kg and 7.5 mg/kg. | AP-AD PNPs increased the concentration of both substances in the blood and heart, extending their residence time in the body and reducing clearance. |

| Navarro-Nunez et al. [36] | PFA-100 test, binding to TP receptor, platelet adhesion tests | Apigenin competed with the ligand [3H]SQ29548 with a Ki value of 155.3 ± 65.4 µM. | Apigenin enhances aspirin’s inhibitory effect on platelet aggregation. Competes with TP antagonist, prolongs occlusion time, may help in aspirin-resistant patients. |

| Szeleszczuk et al. [17,37] | In vivo study in hyperlipidemic rats, HPLC analysis | This extract was administered to the rats orally in doses ranging from 50 to 200 mg/kg body weight. | Extracts contained mainly apigenin and luteolin; beneficial effect on lipid profile. Reduced triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL; increased HDL. |

| Xin et al. [38] | HEK293 cells, MAEC cells, mesenteric artery segments; patch clamp, calcium imaging, pressure myography | In HEK293 cells, apigenin was used in the range of 0.01 µM to 30 µM. | Apigenin activates TRPV4, induces Ca2+ influx and vasodilation. TRPV4 activation is dose-dependent; vasodilation blocked by TRPV4 inhibitors. |

| Study/Author | Model/Subjects | Dose/Method | Main Findings | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhao et al. [44] | Mice with APP/PS1-induced Alzheimer’s | 40 mg/kg apigenin orally for 3 months | Improved memory and learning; reduced amyloid deposits | Restoration of ERK/CREB/BDNF pathway |

| Balez et al. [45] | Human pluripotent stem cell model of Alzheimer’s | Apigenin treatment | Reduced neuronal hyperexcitability; inhibited cytokine activation; reduced apoptosis | Inhibition of nitric oxide production |

| Golonko et al. [29] | Population-level analysis | Dietary flavonoid intake | Higher flavonoid intake linked to lower Alzheimer’s/dementia mortality | Epidemiological correlation |

| Zhao et al. [46] | Monoamine studies | Apigenin and luteolin from perilla | Reduced monoamine levels, potentially alleviating depression and cocaine addiction | Affects monoamine metabolism |

| Lorenzo et al. [47] | Isolated rat atrial tissue | Apigenin | Increased noradrenaline activity; inhibited MAO | MAO inhibition |

| Salehi et al. [15] | Rat brains | Apigenin absorption studies | Can cross blood-brain barrier; inhibits MAO | Potential treatment for anxiety, depression, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s |

| Salehi et al. [15] | Rodents with scopolamine-induced memory deficits | Chamomile extract 200–500 mg/kg | Improved memory (Morris water maze, passive avoidance) | Cognitive enhancement in Alzheimer’s model |

| Kim et al. [48] | In vivo research on mice | Apigenin orally at doses of 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg dail | Apigenin reduced the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, decreased caspase-3 and PARP activation, and decreased the levels of BACE, Presenilin1 and 2, and RAGE receptors, while increasing IDE, BDNF, and TrkB levels | Regulation of apoptosis, amyloidogenesis, and the neurotrophic pathway |

| Ayad et al. [49] | In vivo research on mice | D-galactose—150 mg/kg/day); apigenin—(20 mg/kg/day). | In the D-galactose group, decreased Fis-1 levels and SOD activity, as well as miR-34a and p16 gene expression, were observed, along with increased SA-β-gal activity, MFN-2, ROS, and MDA levels. | Apigenin administration helped maintain mitochondrial homeostasis, miR-34a and p16 expression levels in the D-galactose/apigenin group, and increased SOD activity |

| Mao et al. [50] | GAD patients | Chamomile extract 500 mg, 3x daily | Reduced anxiety symptoms, lowered BP and body weight | Chronic anxiety treatment |

| Amsterdam et al. [51] | Anxiety ± depression patients | Chamomile extract (1.2% apigenin) | Potential antidepressant effects | Modulation of dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine |

| Li et al. [52] | Mice, LPS-induced depressive behavior | Apigenin 25–50 mg/kg daily for 1 week | Reduced depressive behavior and inflammatory response | Suppressed IL-1β, TNF-α, COX2, iNOS |

| Zick et al. [53] | Chronic insomnia patients | Chamomile extract 2.5 mg apigenin | Slight improvement in daytime functioning | Possibly due to flavonoids crossing blood-brain barrier |

| Kramer and Johnson [54] | Chronic insomnia and sleep disorders | Apigenin studies | Apigenin exhibited a sedative effect, reduced motor activity, and improved learning and memory parameters, suggesting a beneficial effect on sleep quality | The mechanisms include modulation of the GABA system, reduction in inflammation, increased glutathione levels, and reduction in oxidative stress markers |

| Authors of Article | Target/Area | Study Model | Apigenin Dose/Administration | Key Findings/Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dai et al. [58] | EV71 Virus (HFMD) | 293S embryonic kidney cells overexpressing SCARB2; BALB/c mice (neonatal) | In vitro: flavonoids tested on cells; In vivo: injected in PBS + DMSO for a week starting 2 h post-infection | In vitro: 85.65% inhibition of cell growth; In vivo: 88.89% survival rate, weight gain; inhibits viral replication by disrupting RNA binding to JNK pathway |

| Wu et al. [59] | Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV) | rAkata cells co-cultured with TW01 and HONE-1; control cells NA and HA; Burkitt’s lymphoma cells | 20 µM and 50 µM in vitro | No cytotoxicity to control cells; blocks lytic expression of EBV; inhibits viral replication in both B lymphocytes and epithelial cells |

| Shibata et al. [60] | Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) | Huh7-Feo human hepatoma cells (replicon system) | 5 µM and higher, administered for 5 days | Significantly reduces HCV replication without harming healthy cells; inhibits miR122 which regulates viral replication |

| Sales et al. [61] | HTLV-1 virus | HTLV-1 MT-4 cell line | 8 µM of apigenin were used to analyze protein expression in PBMCs and 20 µM in experiments with the HTLV-1 MT-4 cell line. | Apigenin can modulate cellular responses through the AhR pathway and enhance the efficacy of antiretroviral drugs against infected cells, without exhibiting its own cytotoxicity up to 128 µM |

| Target/Area | Study Model | Apigenin Dose/Administration | Key Findings/Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tang et al. [62] | E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae and in vivo tests on larvas and mices | 128–256 µg/mL of apigenin and 4 µg/mL of colistin | Apigenin may act as a natural antibiotic adjuvant by directly binding to the MCR-1 protein. |

| Hegazi et al. [63] | Clostridium acetobutylicum DSM1731; Clostridium perfringens KF383123 | Honey samples with flavonoids; compared with antibiotics | Strong inhibition of bacterial growth; highest inhibition against C. perfringens: palm (31.33 mm), cotton (30.33 mm), acacia (30.33 mm); C. acetobutylicum: eucalyptus (25 mm); synergistic effect with drugs observed. |

| Pei et al. [64] | Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | MIC of A7G were 0.14 mg/mL for E. coli and 0.28 mg/mL for S. aureus | The use of half the MIC dose of A7G did not significantly affect bacterial growth itself but strongly reduced biofilm formation—by 83.2% for E. coli and 88.9% for S. aureus. |

| Jafar et al. [65] | Helicobacter pylori | Microsponges contain 250 mg of apigenin and 375 mg of polymer | Apigenin exhibits multifaceted bactericidal activity and may act synergistically with antibiotics, limiting the development of resistance. This is promising solution in the treatment of H. pylori infection and peptic ulcer disease. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Glinkowska, A.; Rzepecka-Stojko, A.; Stojko, J. Therapeutic Potential of Flavonoids—The Use of Apigenin in Medicine. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12996. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412996

Glinkowska A, Rzepecka-Stojko A, Stojko J. Therapeutic Potential of Flavonoids—The Use of Apigenin in Medicine. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12996. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412996

Chicago/Turabian StyleGlinkowska, Anna, Anna Rzepecka-Stojko, and Jerzy Stojko. 2025. "Therapeutic Potential of Flavonoids—The Use of Apigenin in Medicine" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12996. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412996

APA StyleGlinkowska, A., Rzepecka-Stojko, A., & Stojko, J. (2025). Therapeutic Potential of Flavonoids—The Use of Apigenin in Medicine. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12996. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412996