Resilient Adaptive Fuzzy Observer-Based Sliding Control for Nonlinear Systems with Unpredictable Sensor Delays

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We construct a novel adaptive fuzzy observer that approximates the unknown nonlinear dynamics and actively compensates the effect of delayed measurements. The observer explicitly exploits both current and delayed outputs, and its approximation structure draws inspiration from multiobserver- and fuzzy-based designs [18,25,26].

- A sliding-mode controller is developed using observer-estimated states, where the sliding surface incorporates delay-resilient terms and the switching gain is adapted online. The design builds on model–reference SMC principles and adaptive twisting ideas [27,28], ensuring robustness against matched uncertainties and bounded delay-induced disturbances.

- A Lyapunov-based analysis establishes that the closed-loop trajectories remain bounded and that the tracking error converges to a small neighborhood around the origin, without requiring explicit knowledge of the delay. This generalizes existing observer-based feedback schemes for delayed or degraded measurements and clarifies the interaction between delay compensation and SMC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Dynamics and Delay Model

2.2. Fuzzy Approximation and Structural Assumptions

2.3. Composite Disturbance Characterization

2.4. Delay Residual Decomposition

2.5. Adaptive Fuzzy Observer

2.6. Sliding Surface and Control Law

2.7. Adaptive Law

2.8. Comprehensive Lyapunov Stability Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Setup

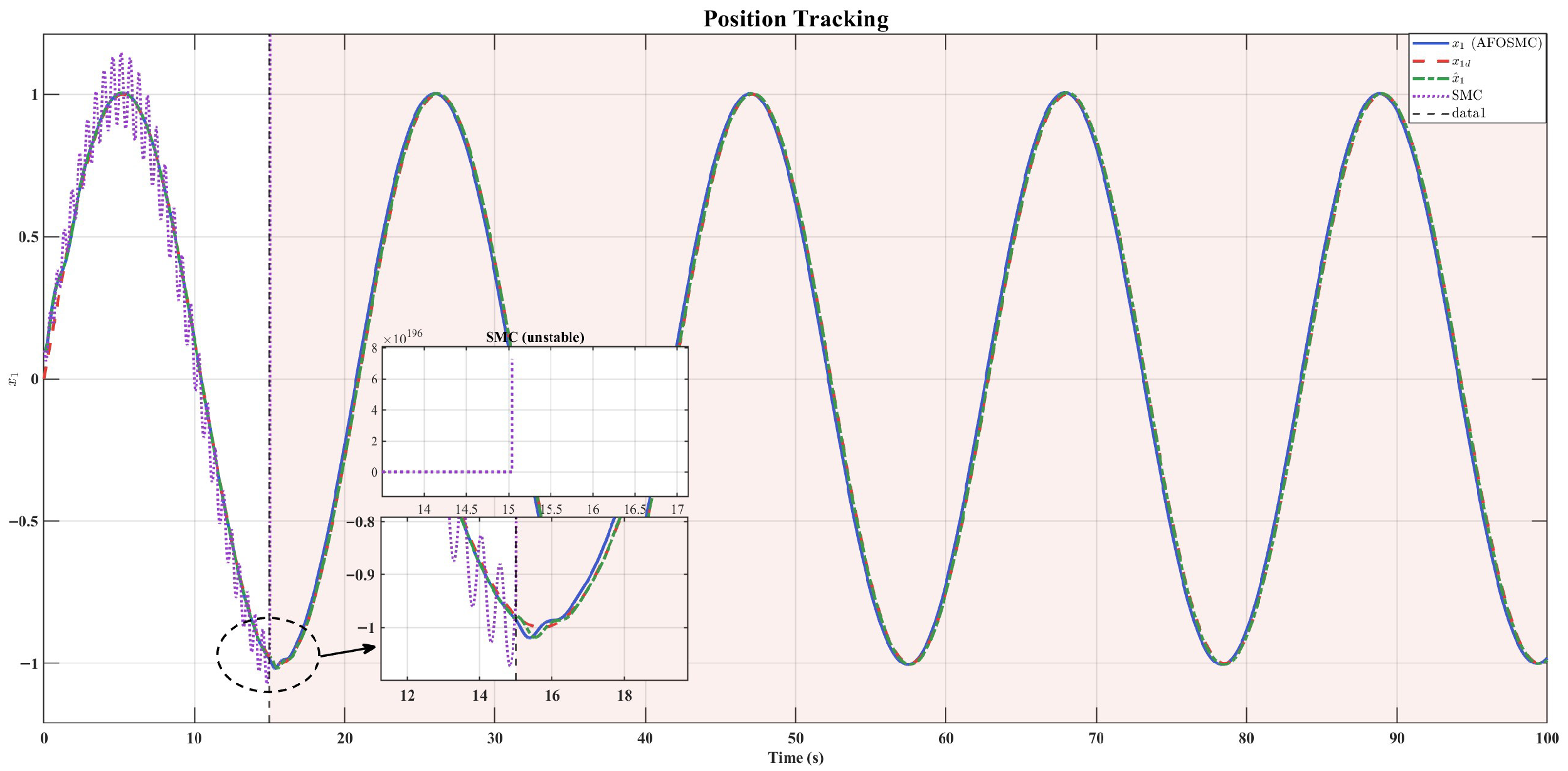

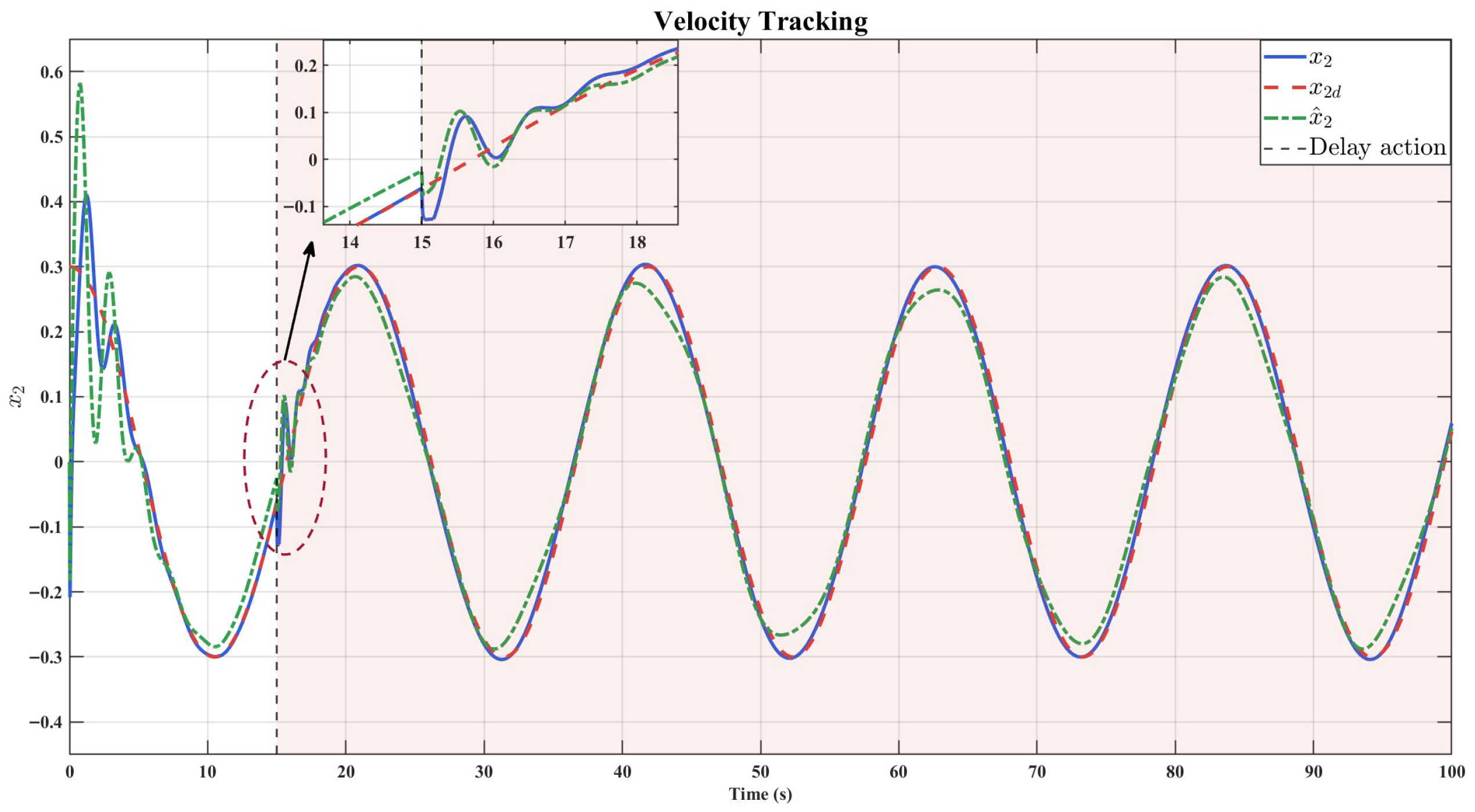

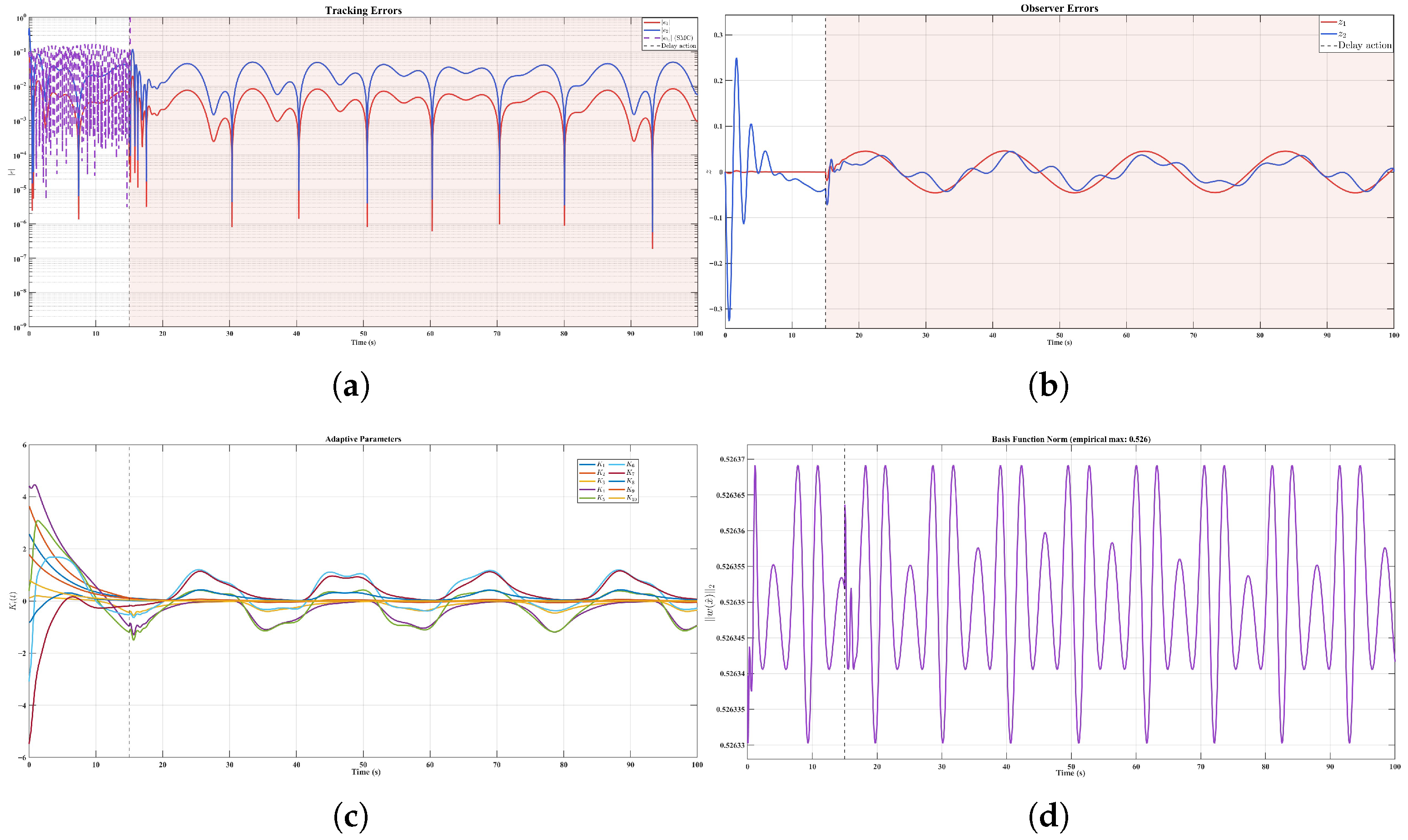

3.2. Tracking Performance

3.3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steinberger, M.; Horn, M.; Ferrara, A. Adaptive control of multivariable networked systems with uncertain time delays. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 67, 489–504. [Google Scholar]

- Leyva-Ramos, J.; Pearson, A.E. Output feedback stabilizing controller for time-delay systems. Automatica 2000, 36, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.H.; Chung, M.J. Memoryless H∞ controller design for linear systems with delayed state and control. Automatica 1995, 31, 917–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.H.; Chung, M.J. Memoryless stabilization of uncertain dynamic systems with time-varying delayed state and control. Automatica 1995, 31, 1349–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.C.; Glover, K.; Khargonekar, P.P.; Francis, B.A. State-space solutions to standard H2 and H∞ control problems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1989, 34, 831–847. [Google Scholar]

- Dugard, L.; Verriest, E.I. (Eds.) Stability and Control of Time-Delay Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arcak, M.; Nešić, D. A framework for nonlinear sampled-data observer design and its application to networked control systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2004, 49, 2063–2068. [Google Scholar]

- Farza, M.; M’Saad, M.; Rossignol, L. Observer design for a class of MIMO nonlinear time-delay systems. Syst. Control Lett. 2010, 59, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, C.M.; Zemouche, A.; Trinh, H. Observer-based control design for nonlinear systems with unknown delays. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II 2021, 69, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, G. Multivariable adaptive control: A survey. Automatica 2014, 50, 2737–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ström, K.J.Ȧ.; Wittenmark, B. Adaptive Control, 2nd ed.; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Narendra, K.S.; Annaswamy, A.M. Stable Adaptive Systems; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.-M.; Han, Q.-L.; Yu, X. Survey on recent advances in networked control systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2016, 12, 1740–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwiger, J.; Steinberger, M.; Horn, M. Spatially distributed networked sliding mode control. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2019, 3, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, S.A.; Chakravarty, A.; Kar, I. Improved event-triggered adaptive control of non-linear uncertain networked systems. IET Control Theory Appl. 2019, 13, 2146–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, P.X.; Shi, P. Observer-based fuzzy adaptive output-feedback control for stochastic nonlinear multiple time-delay systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2017, 25, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zou, L.; Ge, Q.; Dong, H. Observer-based fuzzy PID control for nonlinear systems with degraded measurements dealing with randomly perturbed sampling periods. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2024; early access. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Liang, M.; Li, C.-N. Adaptive fuzzy sliding mode observer for cylinder mass flow estimation in SI engines. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 23889–23900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, D.-P.; Liu, Y.-J. Adaptive neural network tracking design for a class of uncertain nonlinear discrete-time systems with unknown time-delay. Neurocomputing 2015, 168, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, K.; Soo, H.J.; Postlethwaite, I. Discrete-time adaptive control of uncertain sampled-data systems with uncertain input delay: A reduction. IET Control Theory Appl. 2020, 14, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Tan, W. Linear Active Disturbance Rejection Control for Processes With Time Delays: IMC Interpretation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 16606–16617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.-J.; Yang, G.-H. Secure state estimation of nonlinear cyber-physical systems against DoS attacks: A multiobserver approach. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 53, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Wen, C. MAS-based distributed resilient control for a class of cyber-physical systems with communication delays under DoS attacks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 53, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Xia, J.; Deng, R.; Cheng, P.; Yang, Q. Adaptive observer-based resilient control strategy for wind turbines against time-delay attacks on rotor speed sensors measurement. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2023, 14, 1807–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramjug-Ballgobin, M.; Faille, D.; Taylor, C.; Laabir, M.; Gouzé, J.-L. Regularized observer-based parameter and state estimation for biological systems with time-delay differential equations. Math. Biosci. 2020, 327, 108414. [Google Scholar]

- Ramjug-Ballgobin, M.; Taylor, C.; Faille, D.; Gouzé, J.-L. Observer-based control of biomass concentration under discrete and delayed measurements. In Proceedings of the International Conference Control, Automation, Robotics and Vision (ICARCV), Shenzhen, China, 13–15 December 2020; pp. 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, J.P.V.S.; Hsu, L.; Costa, R.R.; Lizarralde, F. Output-feedback model-reference sliding mode control of uncertain multivariable systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2003, 48, 2245–2250. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J.A.; Negrete, D.Y.; Torres-Gonzalez, V.; Fridman, L. Adaptive continuous twisting algorithm. Int. J. Control 2016, 89, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Huang, D.; Yang, G.; Ma, J.; Hu, C. Resilient Adaptive Fuzzy Observer-Based Sliding Control for Nonlinear Systems with Unpredictable Sensor Delays. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12993. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412993

Li L, Huang D, Yang G, Ma J, Hu C. Resilient Adaptive Fuzzy Observer-Based Sliding Control for Nonlinear Systems with Unpredictable Sensor Delays. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12993. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412993

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Luanhui, Deqing Huang, Guang Yang, Junjie Ma, and Chao Hu. 2025. "Resilient Adaptive Fuzzy Observer-Based Sliding Control for Nonlinear Systems with Unpredictable Sensor Delays" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12993. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412993

APA StyleLi, L., Huang, D., Yang, G., Ma, J., & Hu, C. (2025). Resilient Adaptive Fuzzy Observer-Based Sliding Control for Nonlinear Systems with Unpredictable Sensor Delays. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12993. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412993