1. Introduction

The continuous exploitation of coal resources is accompanied by increasingly severe issues related to mine water. The traditional drainage treatment methods not only cause a significant waste of water resources but also bring potential environmental pollution risks. To achieve the utilization of mine water resources, Academician Gu Dazhao [

1] first proposed coal mine underground reservoir technology centered on “conduction-storage-utilization”. This technology has been successfully applied in mining areas such as Shendong, achieving effective storage and utilization of mine water. However, the coal pillar dams reserved in the coal mine underground reservoirs have been continuously exposed to high-mineralization-degree mine water for a long time. The water–rock interaction leads to physical and chemical damage to the coal pillar, resulting in phenomena such as matrix softening, expansion of pores, and fractures, which in turn affect its long-term bearing capacity and stability, and even may cause instability of the dam body and surface subsidence and other engineering geological disasters. Therefore, in-depth research on the dynamic evolution laws of the microstructure of coal and rock under high-mineralization-degree mine water environment is of great theoretical and engineering significance for accurately evaluating the long-term stability of the coal pillar and achieving disaster prevention and control.

Previous studies have shown [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] that the physical and mechanical properties of rocks not only depend on their mineral composition and pore-fissure structure, but are also influenced by external environmental factors, among which the water chemical effect is particularly crucial. Currently, the microscopic mechanism of water–coal interaction has attracted widespread attention. Ting Ai et al. [

10] found that the porosity of coal rock increased after water immersion through nuclear magnetic resonance and scanning electron microscopy; Liu Peng et al. [

11] pointed out that water infiltration aggravates the pore evolution of coal under ultrasonic action and promotes gas diffusion; Yao Qiangling et al. [

12] analyzed the temporal and spatial characteristics of water distribution and crack propagation in coal rock before and after water immersion; Qin Botao et al. [

13] found that water immersion led to a significant increase in the pore size and pore volume of coal samples, showing a significant softening and reaming effect. Additionally, Yang Shijie et al. [

14] used X-ray diffraction and CT scanning to reveal that drilling fluid immersion causes hydration swelling and fracture propagation in coal and rock; Gao Mingzhong [

15] studied the macroscopic behavior and microscopic damage of coal rock under different immersion times by electron microscope scanning and mechanical test and found the surface spalling and microcrack development caused by hydration. Xia Haojun et al. [

16] confirmed that the number of pores in coal rock gradually increased with immersion time through microscopic observation and nuclear magnetic resonance technology. These studies unanimously indicate that water chemical effects have a significant impact on the dissolution of coal-rock minerals and the evolution of pore structure, especially in high-mineralization mine water environments, where the combined effect of multiple ions may lead to more significant structural damage and performance deterioration.

In terms of quantitative characterization of microstructure, the application of fractal theory, image processing techniques, and multi-physical field-testing methods has greatly enhanced our understanding of the pore-fissure system. Mu Guangyuan et al. [

17] combined fractal theory with full-aperture testing to quantify the structural complexity of adsorption pores and flow pores in low-rank coal. He Yang et al. [

18] revealed the evolution patterns of fracture fractal structures under water–coal interaction through water-carried coal particle migration simulation experiments and fractal theory; Liu, Zhen et al. [

19] investigated changes in coal pore volume and permeability under varying water pressures, constructing corresponding fractal models; Wang Min et al. [

20], based on NMR experiments, found that the porosity change rate of coal rock exhibits exponential growth with increasing salt solution concentration and immersion time, while the fractal dimension decreases linearly with immersion time; Zhu Hongqi et al. [

21] analyzed the evolution of fractal dimension of microfractures in coal samples through water immersion experiments; Chen Shida et al. [

22] pointed out that the increase in confining pressure made the pore structure of coal denser and the fractal characteristics of seepage space enhanced. In addition, extreme conditions such as liquid nitrogen freeze–thaw are also used in the research on coal body modification. Qin Lei et al. [

23] and Li Feng et al. [

24], respectively, discovered the laws of the decrease in fractal dimensions of flow pores and adsorption pores under freeze–thaw cycles and liquid nitrogen immersion solutions. Although existing studies have revealed the influence of water–coal interaction on the microstructure of coal rock and used fractal theory and other means to conduct partial quantitative analysis of the pore structure, there is still a lack of systematic and in-depth research on the dynamic evolution laws of coal-rock pore-fissure structure under the immersion of high-mineralization mine water (especially simulating the complex ion components of actual mine water), especially the quantitative characterization of pore morphology, size distribution, connectivity, and structural complexity.

Accordingly, this study conducted laboratory simulations of various mineralized mine water environments. Static immersion experiments were performed on coal samples, with real-time monitoring of solution chemical parameters including pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), electrical conductivity (EC), and oxidation–reduction potential (ORP). The micro-morphology and pore structure of immersed samples were quantitatively analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and a pore-crack analysis system (PCAS). The influence of mineralization degree on the damage and expansion behavior of coal pore-fracture networks was systematically investigated, and the underlying micro-evolution mechanisms were elucidated. The findings provide a theoretical foundation and data support for evaluating the long-term stability and ensuring the safety of coal pillar dams in coal mine underground reservoirs under high-mineralization water conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Coal-Rock Sample

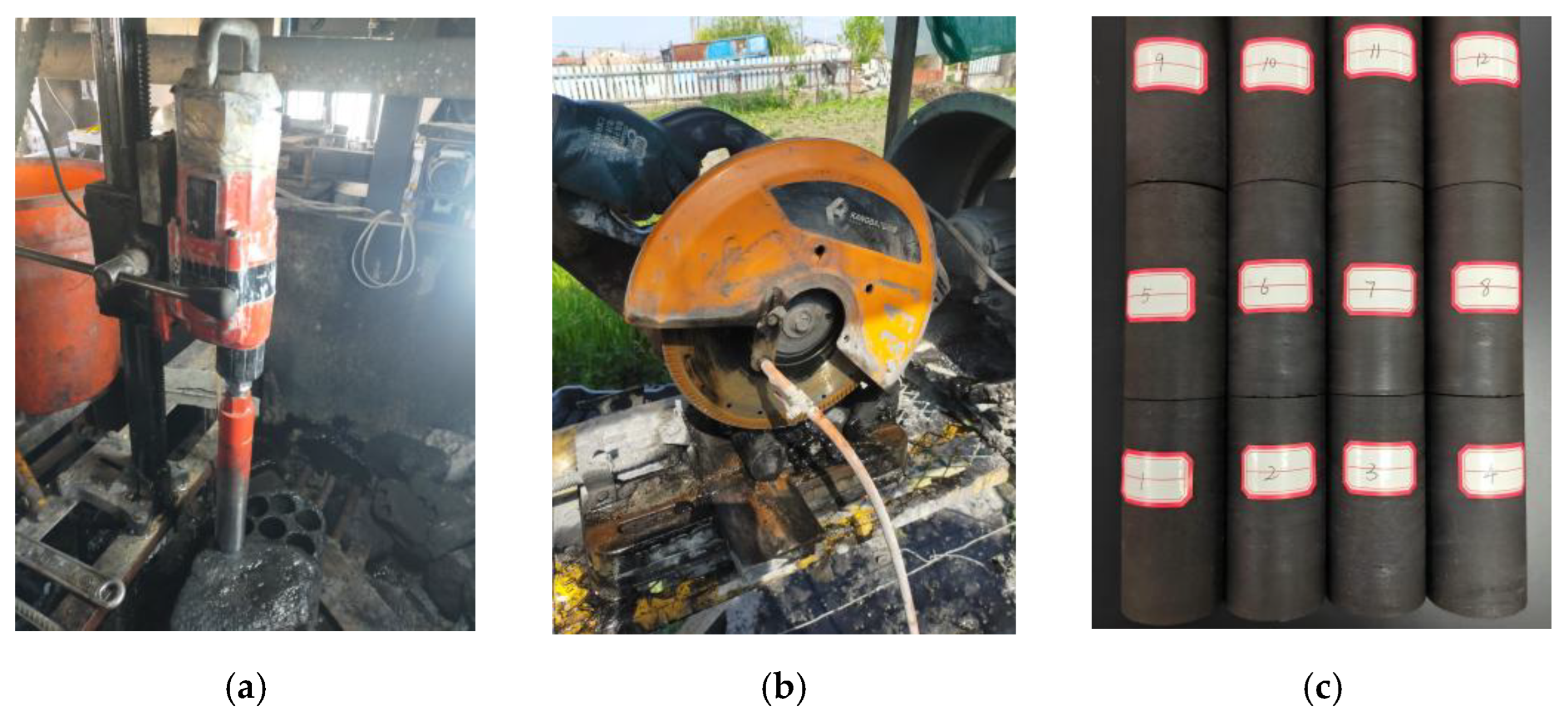

The coal samples selected for the experiment were taken from the Tashan Coal Mine in the Datong mining area, and the coal type was bituminous coal. To reduce the influence of the coal sample’s discreteness on the test results, all the samples were collected from a single large intact coal body in the same mining face. The coal sample preparation process is divided into three steps: first, the raw coal is drilled into a cylindrical sample with a diameter of 50 mm by using a drilling coring machine, and the coring direction is perpendicular to the bedding plane of the coal seam; then, use the cutting machine to cut it into a 100 mm high sample; finally, in order to avoid the slip of coal and rock and the uneven surface, the two ends of the coal sample are polished and polished by a grinding machine. The whole rock sample preparation process strictly follows the International Society of Rock Mechanics standards and the engineering rock mass test method standards. The processed samples were immediately sealed with cling film to prevent weathering effects. The main processing flow of coal rock is shown in

Figure 1.

Given the significant differences in the development of pores and fractures among different coal samples, to effectively reduce the interference of heterogeneity on the test results, this study adopted the acoustic wave detection method to screen the prepared dry coal samples to assess the integrity of the coal samples. The screening criterion was set as an acoustic wave velocity ranging from 1.6 km/s to 1.8 km/s. Ultimately, 15 coal samples were selected and divided into 5 groups, with 3 samples (including 2 parallel samples) set for each group to ensure the repeatability of the experimental data. After completing the relevant physical parameter tests, the subsequent immersion experiments were carried out.

Based on data collection, the main ions in the high-mineralization-degree mine water of coal mines such as Shendong Mine include Ca

2+, Na

+, Mg

2+, Cl

−, SO

42−, and HCO

3−. The ion concentrations in different concentrations of mine water vary. To facilitate experimental analysis, referring to reference [

25,

26], an indoor simulation of groundwater environment was adopted, and representative ions from the groundwater were selected to prepare water solutions of different mineralization degrees. Based on the ion concentrations and contents of the existing highly mineralized mine water, this experiment used five types of salts, namely, CaCl

2, MgSO

4, Na

2SO

4, NaHCO

3, and NaCl, as solutes for the mixture. The specific content of each salt strictly followed the settings in

Table 1 to avoid precipitation reactions between ions. Eventually, five types of simulated highly mineralized mine water solutions with mineralization degrees of 1000 mg/L, 5000 mg/L, 10,000 mg/L, 15,000 mg/L, and 20,000 mg/L were successfully prepared for subsequent immersion tests. During the preparation process, a precision electronic balance and standard volumetric apparatus were used to complete the weighing and volume determination operations, ensuring the precise control and reproducible preparation of the immersion medium components, which provided a strong guarantee of the reliability of the test results.

2.2. Soak Test

The immersion of coal samples is the core of this simulation test. Combined with the actual working conditions of the coal mine underground reservoir, the mine water in the coal mine underground reservoir will show an alternating state of static immersion and dynamic flow in different operating stages, but the whole is still dominated by static immersion. Therefore, the static immersion method is used in the test of high-mineralization mine water immersion coal rock. Because there is no direct sunlight in the underground reservoir of coal mine, except for measuring the water quality process, the rest of the time needs to be carried out under the dark cover. After each water quality measurement, seal the opening of the container with cling film to prevent direct contact with the atmosphere and ensure the accuracy of data interpretation.

To ensure the complete capture of the evolution law of water quality parameters during the immersion process, it is necessary to reasonably set the immersion duration and monitoring frequency. According to existing research, the immersion duration of coal samples is usually determined based on the stability of the solution’s water quality parameters, with the rate of parameter change in the early stage of immersion typically higher than that in the later stage. In this experiment, the immersion duration of the coal samples was ultimately set to 2 weeks (336 h), referring comprehensively to the relevant literature [

27,

28]. To accurately capture the dynamic evolution characteristics of water quality parameters, the data monitoring adopted a phased adjustment approach. Intensive monitoring was conducted within the first 0–24 h, with a monitoring interval of 1 h; after 24 h, the monitoring interval was fixed at 12 h until the end of the 2-week experiment.

During the immersion process, a C-600 pen-type multi-functional water quality meter was used to collect the water quality parameters of the solution. The main parameters monitored included the pH value, oxidation–reduction potential (ORP), total dissolved solid (TDS) content, and electrical conductivity (EC) of the solution. This instrument has high sensitivity, with a pH measurement accuracy within ±0.05, effectively enabling dynamic monitoring of the solution’s water quality parameters. To reduce measurement uncertainty, the instrument was calibrated before each monitoring session, and its accuracy was verified using standard solutions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. PH Change in Immersion Solution

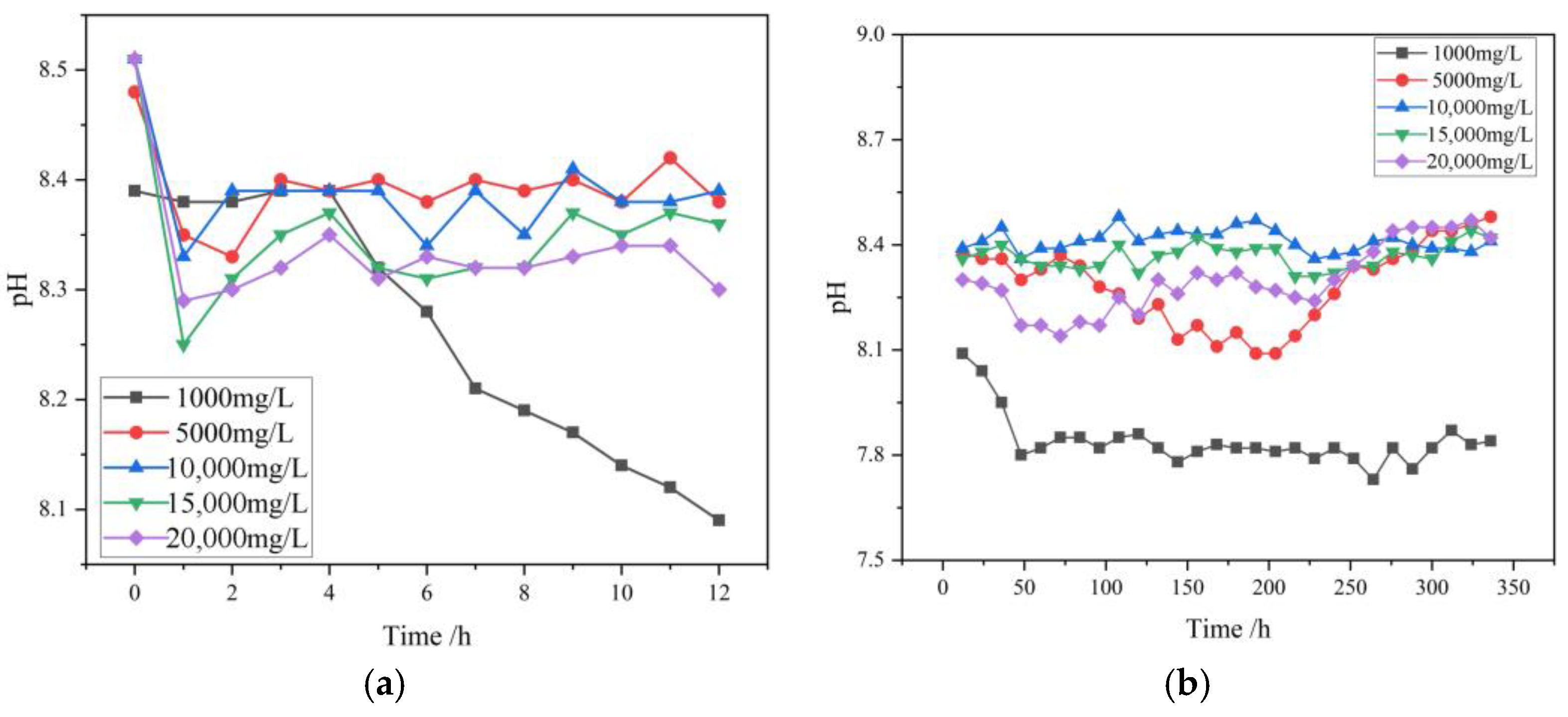

The pH values of the high-mineralization mine water are mostly between 7 and 9. The initial pH values of the high-mineralization solutions configured in this experiment are 8.39, 8.48, 8.51, 8.51, and 8.51, respectively, all within the normal range. As shown in

Figure 2a, within the first 12 h of immersion, the pH values of the solutions decreased compared to the initial values. Among them, the solution with a concentration of 1000 mg/L had the largest decrease, dropping from 8.39 to 8.09. The pH values of this solution changed relatively little in the first 4 h and then continued to decrease after the fifth hour, with a relatively small difference in the rate of decrease per hour. The four solutions with concentrations ranging from 5000 mg/L to 20,000 mg/L all started to decrease from similar initial pH values. Within the first 1 h before immersion, the pH value decrease rate was relatively significant: specifically, the pH of the 5000 mg/L solution decreased from 8.48 to 8.35, the pH of the 10,000 mg/L solution decreased from 8.51 to 8.33, the pH of the 15,000 mg/L solution decreased from 8.51 to 8.25, and the pH of the 20,000 mg/L solution decreased from 8.51 to 8.29. This demonstrates a pattern where the higher the concentration of the soaked solution, the greater the decrease in pH within the first hour. After immersion for 1 to 3 h, the pH values of all solutions showed a slight increase. After 3 h, the pH values fluctuated within a small range and gradually stabilized. The pH value of the 5000 mg/L solution stabilized around 8.4, the pH value of the 10,000 mg/L solution stabilized around 8.38, the pH value of the 15,000 mg/L solution stabilized around 8.34, and the 20,000 mg/L solution stabilized at approximately 8.32. Additionally, solutions with higher concentrations exhibited lower pH values after stabilization.

As shown in

Figure 2b, during the entire two-week immersion period, the pH value of the 1000 mg/L solution decreased significantly within the first 50 h, from 8.39 to 7.8, and then stabilized after 50 h, fluctuating slightly around 7.8. Considering the inherent measurement error of the instrument, it can be concluded that there was no significant difference in the pH value of the solution after 50 h. The pH value of the 5000 mg/L solution continued to decrease to around 8.1 within 200 h, began to rise back to the initial level between 200 and 300 h, and eventually stabilized at around 8.45. The pH values of the 10,000 mg/L and 15,000 mg/L solutions showed minimal changes over a two-week period, stabilizing at approximately 8.41 and 8.36, respectively. The pH value of the 20,000 mg/L solution decreased from 8.5 to 8.2 over the first 100 h, then showed a slow upward trend, ultimately stabilizing at approximately 8.45.

The trend in solution pH directly reflects the dynamic equilibrium of H+ concentration in the solution. In this immersion experiment, solutions of different concentrations of high mineralization all exhibited a decrease in pH, which was mainly attributed to the oxidation and dissolution of minerals such as pyrite (FeS

2) and siderite (FeCO

3) in the coal rock. These mineral components react with dissolved oxygen in the water to form sulfate ions (SO

42−) and iron ions (Fe

2+/Fe

3+), while releasing H

+, thereby increasing the acidity of the solution and lowering the pH value of the water. The chemical reaction mechanism [

29] can be described as follows:

As can be seen from the reactions above, pyrite and siderite in coal rock undergo oxidation upon contact with water, releasing H+ ions which lower the solution pH. Simultaneously, highly mineralized aqueous systems typically contain a certain concentration of HCO3−, a weakly alkaline anion. In an acidic environment, HCO3− can combine with H+ to form H2CO3, which subsequently decomposes into CO2 and H2O. In a solution with a concentration of 1000 mg/L, the concentration of HCO3− is low, and its ability to neutralize H+ is weak, so the decrease in the pH value of the solution is relatively large whereas in solutions with a concentration of 5000 mg/L or higher, the concentration of HCO3− is high, which can act as an effective buffering system to neutralize the H+ produced by the oxidation reaction, allowing the pH of the solution to gradually rise and stabilize after consuming the H+.

3.2. Changes in TDS of the Immersion Solution

The total dissolved solid (TDS) content of the immersion solution is a key indicator for characterizing the total amount of dissolved solids in water and is often used as an important basis for assessing the degree of mineralization of a water solution. In indoor experiments simulating the immersion of coal rock in high-mineralization mine water, the trend in TDS values is shown in

Figure 3. The experimental results show the following: For the 1000 mg/L solution, the initial TDS value was 1000 mg/L, which decreased from 1000 mg/L to 975 mg/L (a decrease of 2.5%) between 0 and 7 h, then rose back to around 1000 mg/L between 7 and 12 h, and continued to increase after 12 h, reaching a final TDS value of 1150 mg/L after two weeks of immersion (an increase of 15% from the initial value). The TDS value of the 5000 mg/L solution decreased from 5000 mg/L to 4640 mg/L (a decrease of 7.2%) between 0 and 9 h, increased to approximately 4900 mg/L between 9 and 12 h, and continued to rise after 12 h, reaching a final TDS value of 5200 mg/L after two weeks. The initial TDS value of the 10,000 mg/L solution decreased from 10,000 mg/L to 9365 mg/L (a decrease of 6.4%) between 0 and 8 h, increased to approximately 9700 mg/L between 8 and 12 h, and continued to rise after 12 h, stabilizing at approximately 9900–10,000 mg/L by the end of the 24 h immersion period. The initial TDS value of the 15,000 mg/L solution decreased from 15,000 mg/L to 14,210 mg/L (a decrease of 5.3%) between 0 and 12 h, and between 12 and 24 h, it rose to approximately 14,739 mg/L, and after 24 h until the end of the immersion, the TDS value fluctuated slightly around 14,800 mg/L. Considering instrument error, it can be considered that the TDS value of the solution had stabilized at this point. The initial TDS value of the 20,000 mg/L solution decreased from 20,000 mg/L to 19,488 mg/L (a decrease of 2.6%) between 0 and 6 h, increased to 19,800 mg/L between 6 and 12 h, and between 12 and 24 h, it further increased to around 20,000 mg/L. After 24 h until the end of the immersion process, the TDS value fluctuated slightly around the initial concentration (20,000 mg/L). Considering instrument error, this indicates that the TDS value of the solution had stabilized at this point.

In the experiment simulating the immersion of coal rock in simulated high-mineralization mine water, at the initial stage of immersion, different concentrations of high-mineralization solutions all showed a slight decrease in TDS values. This is because in the initial stage of contact between the high-mineralization solution and the coal rock, the cations in the solution are adsorbed at negatively charged sites on the surface of clay minerals through electrostatic interaction, or combine with the negatively charged groups of organic matter in the coal, resulting in a temporary decrease in the concentration of soluble salts in the solution [

30].

As the immersion time is extended to approximately 8 h, the TDS of most solutions begins to gradually increase. This phenomenon is attributed to the adsorption sites of clay minerals or organic matter reaching saturation, causing adsorbed salt ions to desorb into the solution due to concentration gradients or differences in chemical potential; simultaneously, soluble minerals in the coal rock gradually dissolve and release salt ions, with both processes collectively driving an increase in solution mineralization. During the initial stages of immersion, water absorption and swelling of clay minerals or organic matter may cause pore blockage, inhibiting dissolution. However, as immersion time increases, the expansion of internal fractures or the breakdown of cementation in the coal rock enhances permeability, thereby promoting the continued dissolution and release of soluble salts from deeper layers.

After two weeks of immersion, a 1000 mg/L solution exhibited a TDS increase phenomenon. This was due to the relatively weak inhibitory effect of the lower salt concentration on the dissolution of minerals. The clay minerals and calcite in the coal rock gradually dissolved and released salt ions, while the dissolution and oxidation process of siderite and pyrite produced sulfate ions, resulting in a significant increase in the solution’s mineralization degree. In a high-mineralization-degree environment of over 5000 mg/L, the salt ion concentration in the solution was at a relatively high level, and the chemical equilibrium of dissolution–precipitation shifted towards precipitation, effectively inhibiting the further dissolution of minerals. Therefore, the TDS value maintained a relatively stable state.

3.3. Changes in ORP of the Immersion Solution

The oxidation–reduction potential (ORP) of a solution is a comprehensive electrochemical parameter that characterizes the strength of the oxidizing or reducing properties of a water body. As shown in

Figure 4b, during a two-week immersion period, the ORP values of mine water samples at different concentrations all exhibited a decreasing trend with increasing immersion time. The ranges of change were as follows: 164 mV to −3 mV (1000 mg/L), 151 mV to −32 mV (5000 mg/L), 149 mV to −40 mV (10,000 mg/L), 147 mV to −44 mV (15,000 mg/L), and 143 mV to −53 mV (20,000 mg/L). The ORP values continued to decrease in the negative direction, indicating that the oxidizing properties of the solution gradually weakened, while the reducing properties correspondingly increased. Compared with the values before immersion, the ORP values of the solutions after two weeks of immersion decreased by 167, 183, 189, 191, and 196 mV, respectively. After approximately 300 h, the ORP values of the solutions tended to stabilize.

As shown in

Figure 4a, within the first 12 h of immersion, the redox values of different concentrations of high-mineralization mine water solutions all dropped rapidly in the first 2 h, then rebounded in the third hour and continued to decline thereafter. Among them, the 1000 mg/L solution had a relatively slow rate of decline in the first 3 h, while the 5000 mg/L, 10,000 mg/L, 15,000 mg/L, and 20,000 mg/L solutions dropped rapidly in 4–5 h and then declined slowly in 5–12 h.

During the entire immersion test period, the oxidation–reduction potential value showed a general downward trend. This was mainly due to the continuous oxidation of siderite, pyrite, and organic carbon, which continuously consumed the dissolved oxygen in the solution. Moreover, the immersion experiment was not completely sealed, which promoted the continuous oxidation reaction until the oxidation–reduction potential value stabilized after 300 h. The rapid decline and subsequent recovery of the oxidation–reduction potential within the first 12 h was closely related to the change in solution pH, indicating that the pH change in the early stage of the immersion dominated the variation in the oxidation–reduction potential value. Since the H+ ion has a strong oxidizing ability, its concentration reduction would lead to a decrease in the oxidizing property of the solution, thereby causing a decrease in the oxidation–reduction potential.

3.4. Changes in EC in Immersion Solution

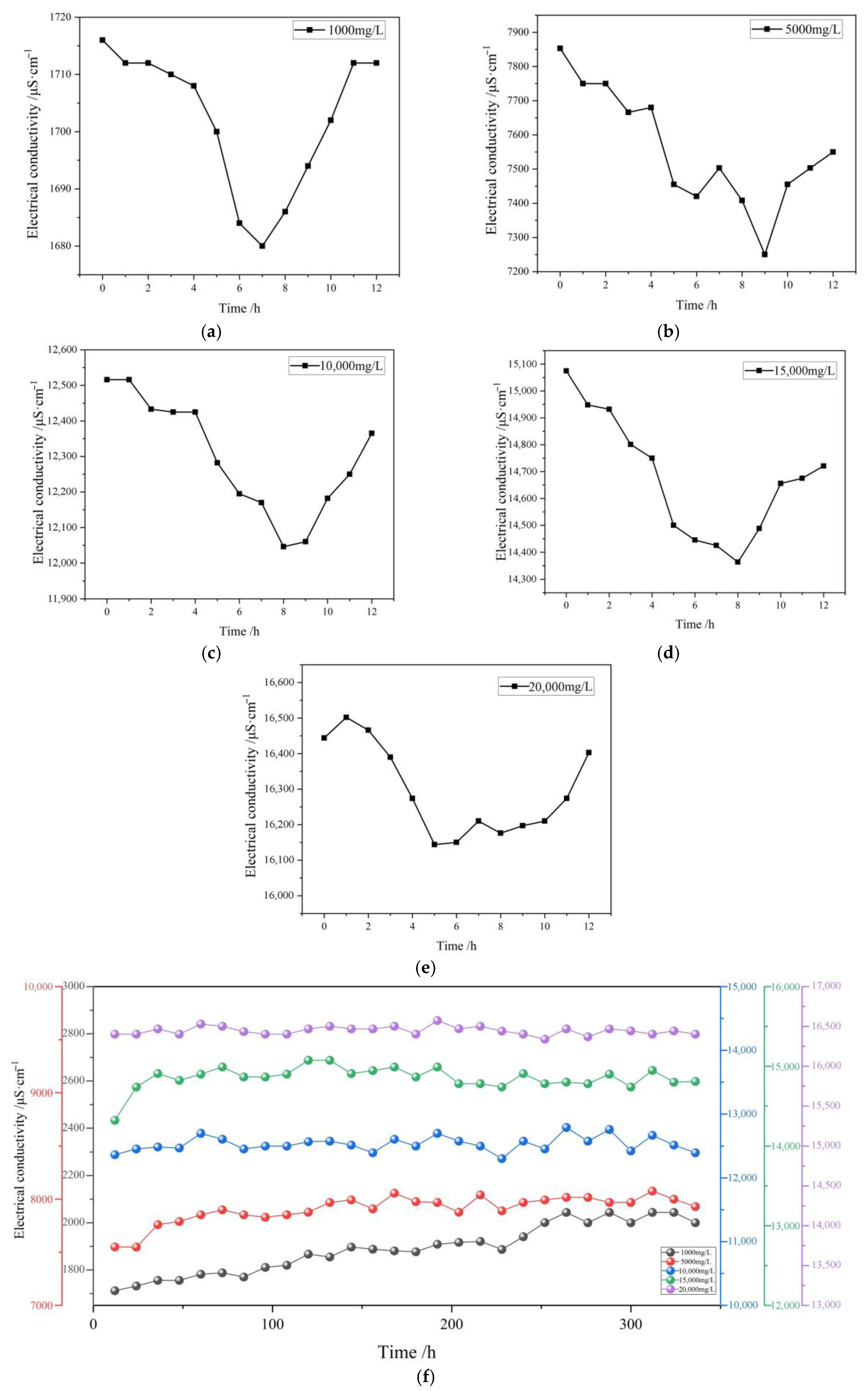

Conductivity (EC) is an important parameter for characterizing the conductive performance of a solution.

Figure 5 shows the variation pattern of the solution’s EC value over time during the immersion of coal rock in highly mineralized mine water. From the figure, it can be seen that the trend of the solution’s EC value during the immersion process is highly similar to the variation curve of total dissolved solids (TDS). Within the initial 12 h of immersion, the EC value and TDS value variation curves of solutions at different concentrations are essentially consistent, with their numerical fluctuations and the timing of peak values highly aligned.

As shown in

Figure 5f, the conductivity value of the 1000 mg/L solution exhibits a continuous upward trend over 12–250 h, with a range of 1712 μS/cm–2044 μS/cm. After 250 h, the conductivity value stabilizes around 2000 μS/cm. The conductivity value of the 5000 mg/L solution shows a continuous increase from 12 to 130 h, with a range of 7549 μS/cm to 8076 μS/cm, and stabilizes around 8000 μS/cm after 130 h. The conductivity value of the 10,000 mg/L solution fluctuated within the range of 12,365 μS/cm to 12,791 μS/cm over a period of 12 h to 2 weeks, and remained consistently around 12,500 μS/cm. The conductivity value of a 15,000 mg/L solution increased steadily from 14,321 μS/cm to 14,908 μS/cm over 12 to 36 h, stabilizing at approximately 14,900 μS/cm after 36 h. The conductivity value of the 20,000 mg/L solution exhibited irregular fluctuations during the first 12 h, after which it stabilized around 16,400 μS/cm.

Whether during the initial immersion phase or after two weeks of continuous immersion, the EC and TDS values of the solution exhibit a close correlation, indicating a strong positive correlation between the solution’s conductivity and total dissolved solids (TDS). The underlying mechanism is as follows: in high-mineralization mine water, nearly all of the total dissolved solids are composed of dissolved inorganic salts. As free-moving ions, these dissolved inorganic salts act as carriers of electric current. Therefore, the higher the ion concentration, the stronger the solution’s conductivity.

3.5. Changes in the Microscopic Morphology of Coal Rock After Immersion

This experiment used a JSM-7610F field emission scanning electron microscope manufactured by JEOL Ltd. to observe the microscopic morphological characteristics of coal rock. The device is equipped with a semi-immersion objective lens and a high-performance electron optical system, providing excellent imaging performance. In order to accurately capture the nanoscale microscopic morphological characteristics of coal rock pores, this study selected an acceleration voltage of 15.0 kV and used a 0.8 nm resolution mode for detailed analysis.

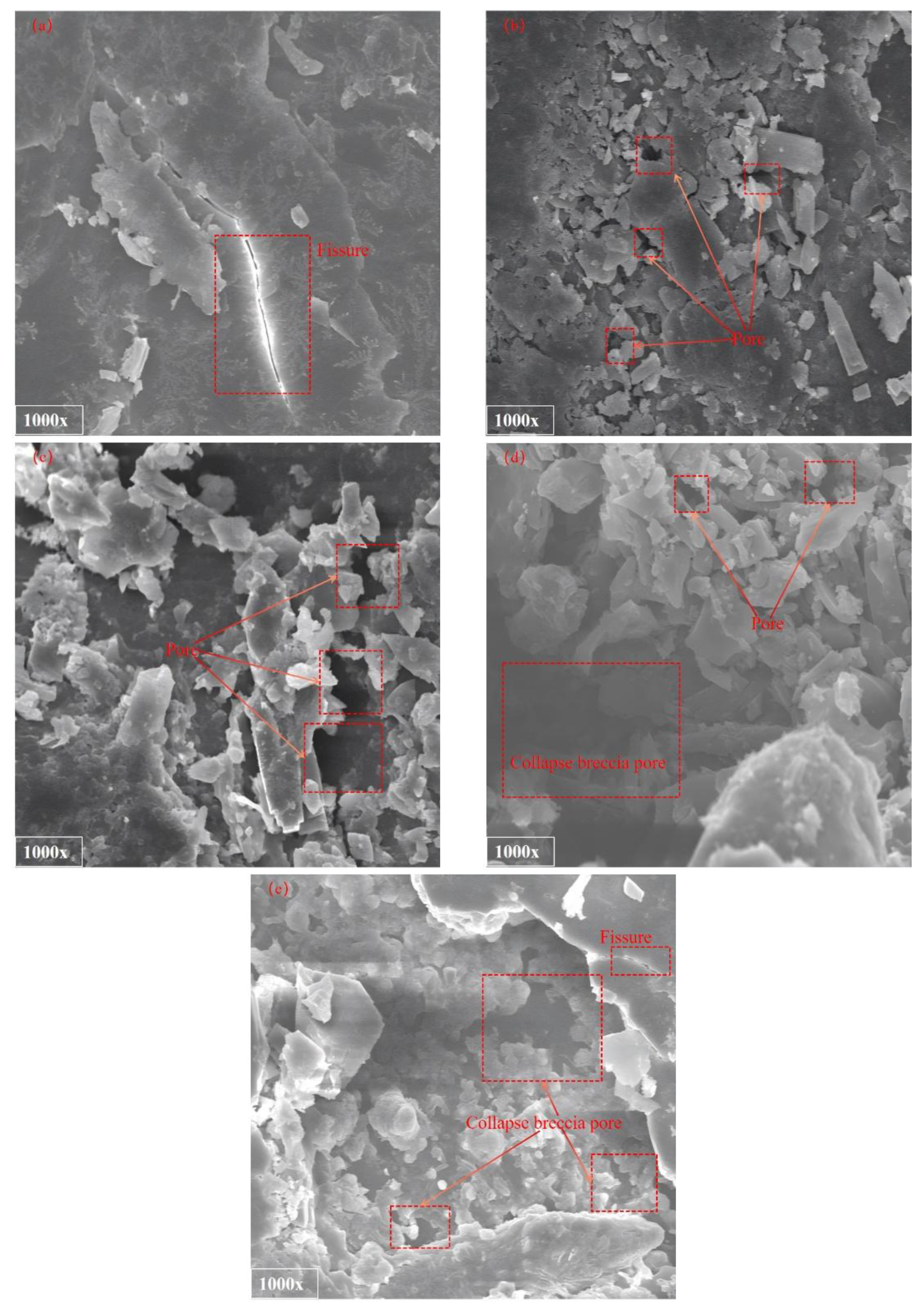

After being soaked in high-salinity solutions for two weeks, the pore structure characteristics of the coal rock under scanning electron microscopy are shown in

Figure 6a to (e), which correspond, respectively, to the microscopic scanning images of the coal rock after being soaked in solutions with initial concentrations of 1000 mg/L, 5000 mg/L, 10,000 mg/L, 15,000 mg/L, and 20,000 mg/L.

From the SEM images, it is evident that, as the mineralization degree of mine water increases, the microstructure of coal and rock undergoes a systematic evolution. Following immersion in a solution with a mineralization degree of 1000 mg/L, the surface matrix remains largely intact, exhibiting a regular and smooth morphological profile. The erosive effect of mine water at this concentration is minimal, resulting in limited development of secondary pores. Pores and fractures are predominantly primary in origin, with a distinct bright reflective band observed along the primary fractures due to physical deposition of salts. As the mineralization degree of the immersion solution increases to the range of 5000–10,000 mg/L, the erosive impact on the coal and rock matrix becomes progressively more pronounced. A significant increase in pore quantity is observed, accompanied by the widespread formation of small dissolution pores, fragmented particle pores, and other types of secondary porosity. Simultaneously, salt crystals continue to accumulate on the matrix surface, leading to a transformation from an initially smooth topography to a visibly uneven surface. The surface flatness index decreases markedly, exhibiting initial signs of microscale roughness—indicative of the early-stage degradation of coal and rock structural integrity. In solutions with a mineralization degree of 15,000 mg/L, the pore types of the coal matrix show diverse development. Besides the primary pores, a large number of new pore types such as exogenous breccia pores, intergranular pores of debris, and structural fragmented particle pores are formed. However, the connectivity of these pores is generally poor, and no effective permeation channels are formed. Moreover, the outline of salt crystalline particles around the pores becomes increasingly clear, and their size is significantly larger than that in medium- and low-mineralization environments. Affected by the continuous intensification of erosion, the surface of the coal rock presents a complex and rough morphology. There is a directional expansion trend of dissolution pores, and the width and length of the fractures increase simultaneously. Eventually, the matrix layer is eroded into a sheet-like structure. When mineralization reaches an extremely high level of 20,000 mg/L, the fragmentation characteristics of the coal-rock matrix can be visually observed to intensify significantly through SEM images. Specifically, the roughness of the boundaries of dissolution pores and fragmented particle pores increases and is accompanied by severe serration. Collapsed breccia pores, dissolution pores, and debris pores are interconnected to form a highly irregular composite pore system, filled with a large amount of salt crystalline particles inside the pores and with rough and uneven pore walls. In addition, large-scale matrix peeling occurs on the surface of the coal rock, and the degree of fracture connectivity increases significantly. Some fractures intersect each other to form a complex network structure.

In summary, the evolutionary pattern of coal-rock microstructure can be summarized as follows: as the mineralization degree of the immersion solution increases, the structure transitions from being structurally intact with simple pores at low concentrations to exhibiting interconnected pores and fragmented matrix at high concentrations.

3.6. Changes in the Pore Structure of Coal Rock After Immersion (Quantitative Analysis)

The variation in microscopic structure parameters of coal and rock is an important characterization of its microstructure. In this study, microscopic images were acquired via scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and the images were processed and analyzed using the Pore and Crack Analysis System (PCAS) developed by Nanjing University. The specific processing workflow includes importing SEM images and converting them to grayscale images; performing threshold segmentation based on the maximum between-class variance method (the Otsu method) to accurately distinguish pores/fissures from the matrix; generating binary images; eliminating noise and optimizing small pores; and finally extracting the geometric contours and topological networks of pores/fissures through vectorization. Based on this technical route, the system quantitatively identified the pore networks and fissure structures of coal and rock samples, and the identification process is illustrated in

Figure 7. Using the obtained high-precision vectorized data, key microscopic structure parameters (including pore and fissure size, shape factor, probability density entropy, and fractal dimension) were further calculated.

3.6.1. Equivalent Pore Diameters (d)

The traditional equivalent diameter method, which is based on measuring the longest chord at the pore center, is difficult to accurately characterize the complex pore morphology and connectivity. Therefore, in this study, PCAS software (V2.325) was adopted to automatically recognize and count the pixel area S of each pore. The equivalent pore diameter was calculated in accordance with the circular area equivalence principle (Equation (1)), and the statistical results are presented in

Table 2. The PCAS-based analysis reveals that the equivalent pore diameters primarily distribute within four intervals, namely, 4~10 μm, 10~16 μm, 16~24 μm, and >24 μm.

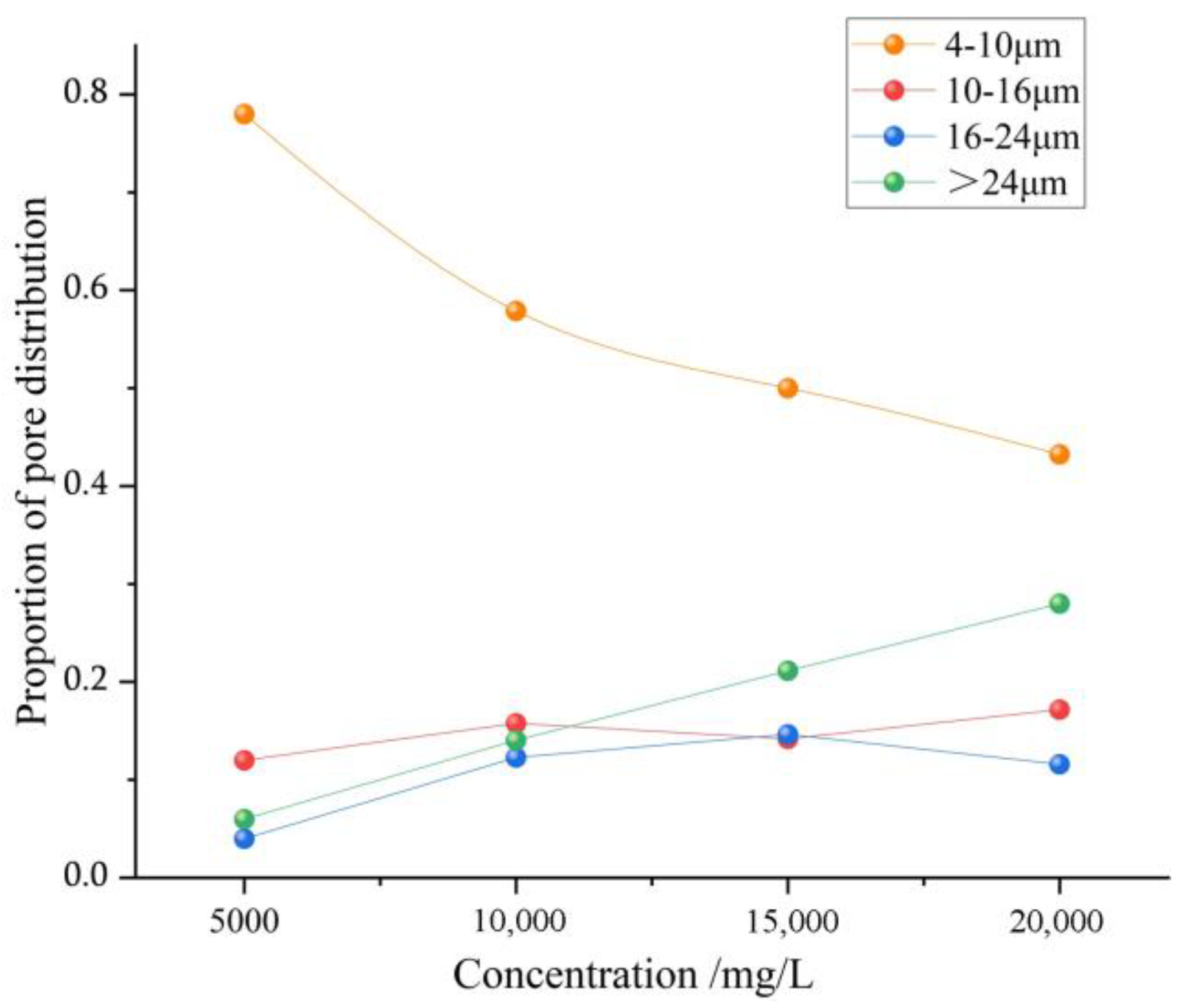

When the mineralization degree increased from 5000 mg/L to 20,000 mg/L, the proportion of pores within the 4–10 μm size range decreased by 34.8%. The pores in this range are mainly composed of fragmented pores and angular gravel pores. The decrease in the proportion of these pores indicates that after being soaked in the high-mineralization-degree solution, the fragmented pores and angular gravel pores have connected, resulting in a reduction in the number of pores but an increase in size and an enlargement of the pore diameter. Based on the statistical results in

Table 2,

Figure 8 was drawn.

Figure 8 illustrates the systematic influence of mineralization degree on the pore size distribution of coal rock. As the mineralization degree increases, the proportion of large pores with equivalent pore sizes >24 μm exhibits a significant linear increase (22% increase), indicating that high-mineralization degree promotes the development of large-pore structures in coal rock. Combined with scanning electron microscopy, it can be seen that the coal matrix layer has been eroded, forming dissolution holes, through cracks, and other large pores. However, the proportion of pores in the 10–16 μm and 16–24 μm ranges shows no significant change. The reason for this is that an initial increase in mineralization degree promotes matrix dissolution and the formation of numerous pores; however, continued elevation results in the crystallization of dissolution products or ions, which occludes the pores, ultimately causing a slight decline in porosity within this range.

3.6.2. Average Shape Factor (ff)

The shape factor is a dimensionless parameter that quantitatively characterizes the degree to which the geometric shape of microscopic pores deviates from the ideal regular shape (such as circular or spherical). It has significant application value in the quantitative analysis of pore structures. Its theoretical range is from 0 to 1, and the circular pores reach the maximum value of 1 [

31].

This study employs the average shape factor as an indicator for characterizing pore roundness. Using PCAS software, the perimeter

L and area

S of individual pores are statistically analyzed. The shape factor for each pore is calculated based on Formula (2), and the arithmetic mean is then computed for all effective pores (see Equation (3)). The variation pattern is illustrated in

Figure 9.

In the formula, n is the number of particles counted. The value of ff ranges from 0 to 1, and the smaller the value, the more complex the shape of the particle edges.

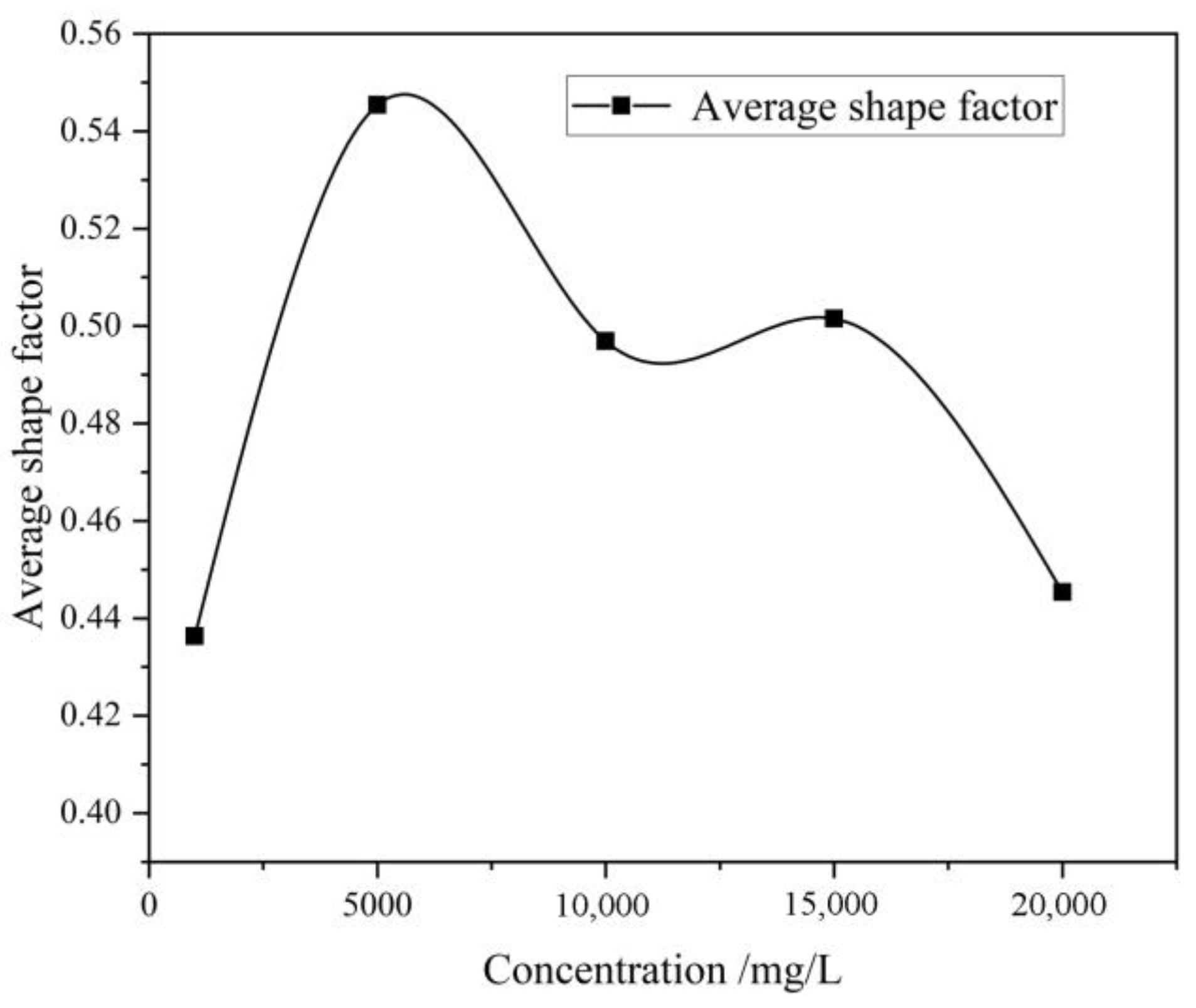

As shown in

Figure 9, when the mineralization degree value increased from 1000 mg/L to 5000 mg/L, the increase in the average shape factor indicated that the pore boundaries became smoother and the geometric shape became more regular. Combining with the microscopic images, it can be seen that when the coal rock was soaked in the mine water with a mineralization degree of 1000 mg/L, there were fewer pores and a longer fracture, corresponding to a smaller shape factor; after being soaked in the solution with a mineralization degree of 5000 mg/L, the coal-rock matrix presented more fine pores, mainly of dissolution pores and angular grain pores. When the mineralization degree increased to 10,000 mg/L, large irregular pores were formed in the coal-rock matrix, some pores merged to form larger pores with a longer shape, and the average shape factor decreased accordingly. When the mineralization degree further increased to 15,000 mg/L, the average shape factor continued to decrease but the decrease was smaller; the microscopic images showed that the microscopic surface of the coal rock presented a significant fragmentation feature; the surface of the matrix had more salt crystals; the pore types were mainly dissolution pores and angular grain pores; the pore boundary shapes were irregular; and the perimeter increased, resulting in a slight decrease in the shape factor. When the mineralization degree increased to 20,000 mg/L, the pores were mainly collapsing angular grain pores; the irregularity of the pores and fractures significantly increased, causing a significant decrease in the average shape factor.

3.6.3. Fractal Dimension (D)

Fractal dimension, as a key parameter for describing the non-smooth and irregular geometric forms in nature, can effectively characterize their self-similarity and structural complexity. In the study of coal rock pore structure, this parameter can provide quantitative information about the pore characteristics, and its numerical changes can reflect the evolution laws of the pore structure of coal-rock under immersion conditions of mine water with different mineralization degrees. This study employs the area–perimeter method to calculate the fractal dimension. Based on the vectorized pore boundaries extracted from images, the area S and perimeter L of each pore are statistically determined. Linear fitting is performed in a double-logarithmic coordinate system, and the fractal dimension

D is derived from the fitted slope. Among them, the relationship between the microscopic fractal dimension value of coal rock and the microscopic pore area (

S) and perimeter (

L) satisfies the following formula [

32]:

In the formula, D is the fractal dimension of the area perimeter method, with values ranging from 1 to 2. Smaller D values indicate simpler particle structure and the smoother the surface of the particle. c is a constant.

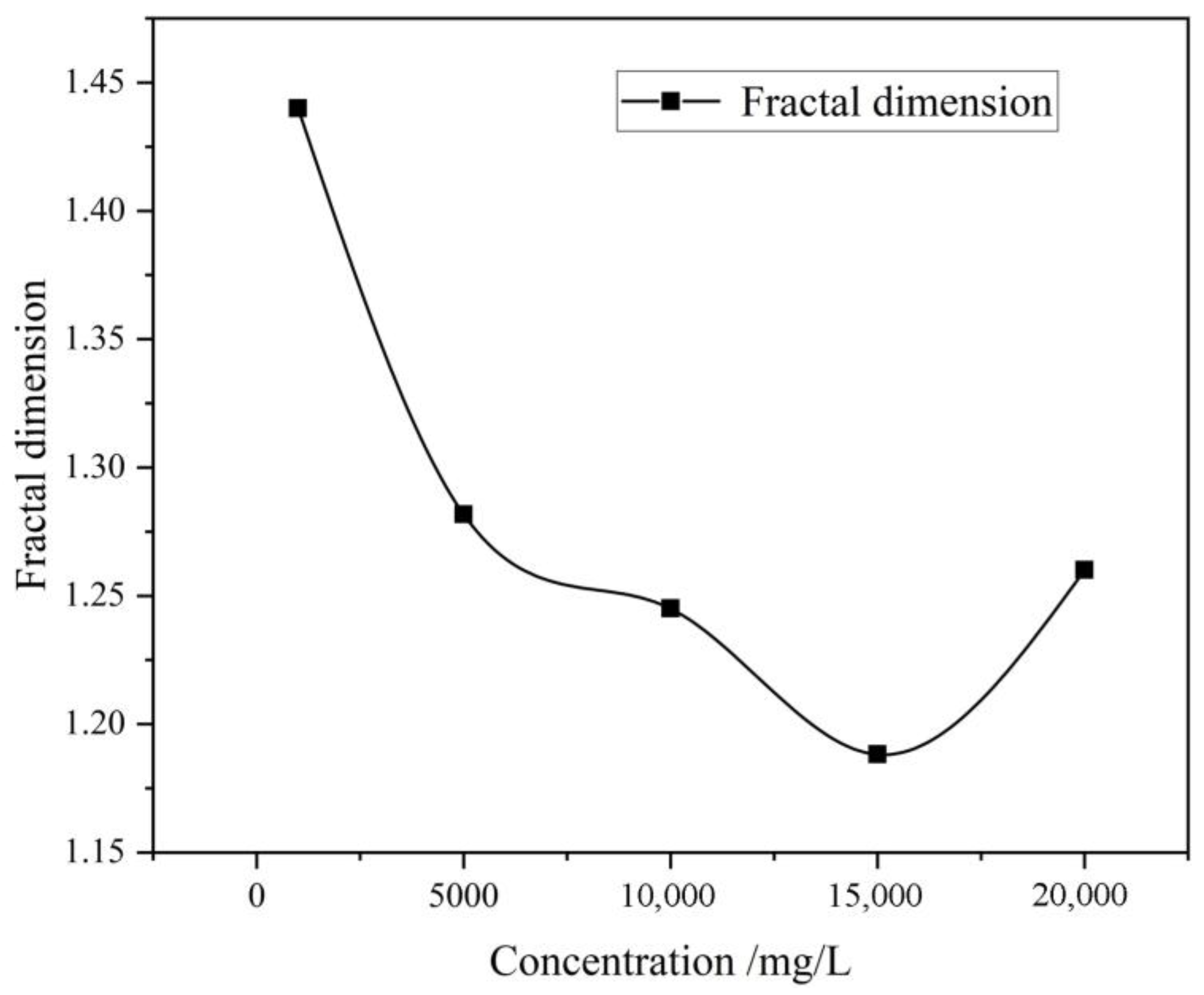

As shown in

Figure 10, after immersion in a highly mineralized solution, the fractal dimension (

D) of the microscopic pores in coal rock first decreases and then increases as the mineralization degree rises. Under conditions of 1000 mg/L mineralization concentration, the coal-rock matrix is relatively flat, but there is a primary crack, which is narrow and long, resulting in a relatively high fractal dimension. As mineralization concentration increases, the degree of fragmentation of the coal matrix intensifies, with erosion grooves appearing on the surface and an increase in the number of pores. Components such as mineral ions in the aqueous solution preferentially interact with the smaller and irregular pore surface in the coal rock, resulting in a smooth pore edge and a regular shape, and the complexity of the pore structure is reduced, resulting in a decrease in the fractal dimension

D value. When the mineralization degree further increases to the range of 10,000 mg/L to 15,000 mg/L, the fragmentation of matrix layer particles becomes evident, the number of pores significantly increases, and large collapsed angular gravel pores appear. Simultaneously, some adjacent irregular small pores undergo fusion. During the initial stage of fusion, the size of newly formed pores increases, but their overall structure exhibits a trend toward relative simplification and regularization, resulting in a reduction in the complexity of the pore network structure during this phase, with the fractal dimension

D value continuing to decrease accordingly. When the mineralization degree reaches 20,000 mg/L, the interaction between coal-rock mineral components and mine water intensifies, leading to the breakdown of more chemical bonds within the coal rock. This causes further dissolution and fragmentation of pore walls, resulting in the formation of more branches and smaller secondary pores. Based on scanning electron microscope (SEM) image analysis, it is evident that under these conditions, a highly complex pore structure has formed, where newly formed pores intertwine with existing pores to form a pore network with a more complex topological structure. This significantly increases the overall irregularity and complexity of the pore system, resulting in an increase in the fractal dimension (

D) value.

3.6.4. Probability Entropy (H)

Probability entropy is an extension of information entropy in continuous probability distributions used to quantify the uncertainty of random variables or the degree of disorder in a distribution. In coal-rock pore analysis, it measures the heterogeneity or complexity of pore structure by statistically analyzing the probability density function of pore characteristics. Its mathematical expression is [

33].

In the formula, Hm is the probability entropy. The value range is between 0~1; the greater the value, indicating that the particles or pores are arranged disorderly, the more chaotic the microstructure; in the process of microscopic image processing, the azimuthal range of the long axis of particles or pores (0°~180°) is usually divided into 18 intervals at intervals of 10°. The interval index i identifies the angle partition (for example, i = 1 corresponds to 0°~10°), so the maximum value n of i is 18. mi is the number of particles or pores whose long axes fall within the i-th azimuth angle interval; M represents the total number of statistically analyzed particles or pores.

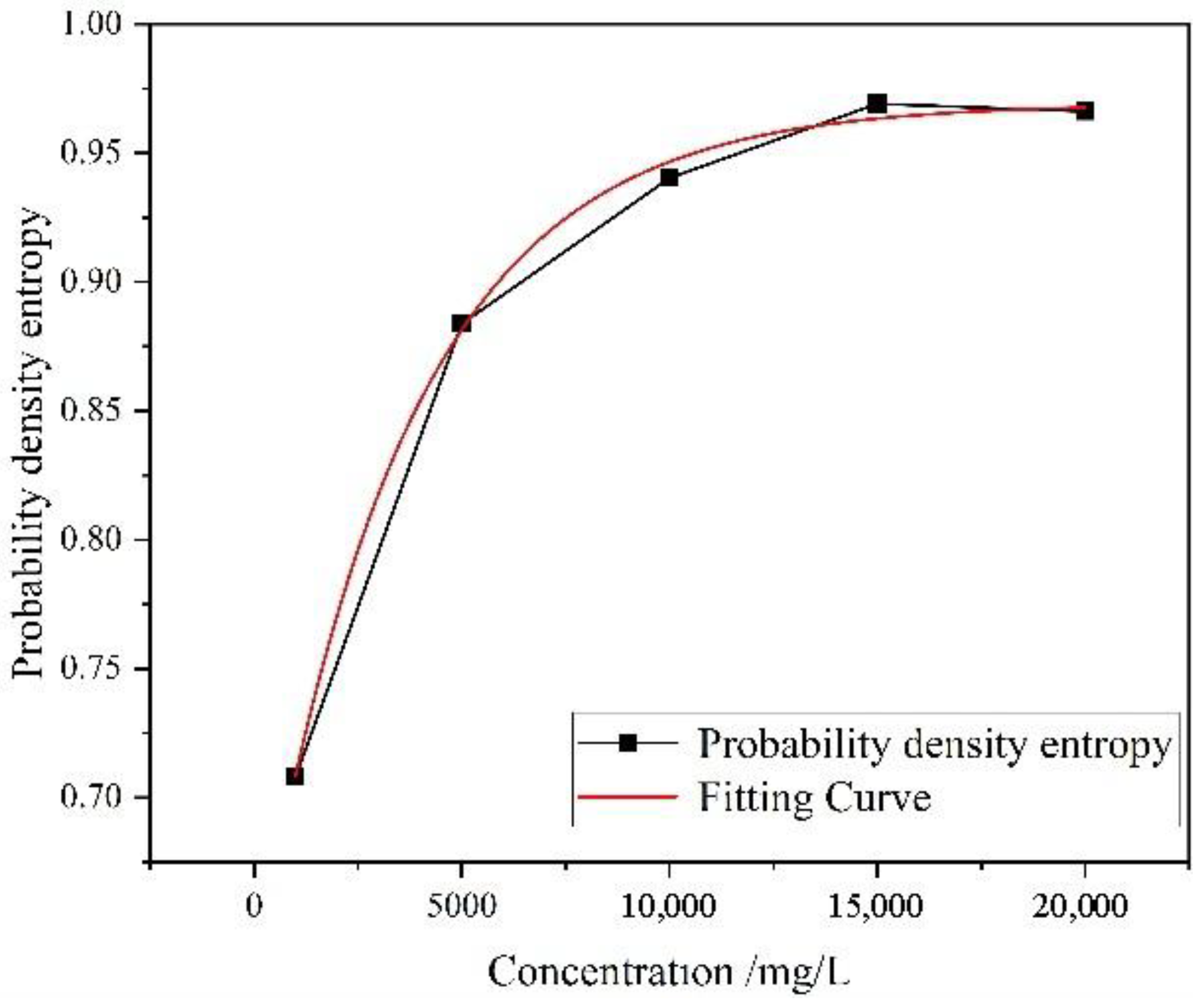

As illustrated in

Figure 11, the pore probability entropy of coal rock calculated in accordance with Equation (5) exhibits a significant upward trend with the increase in the mineralization degree of the immersion environment, with a total increase of 36.9%. This change indicates that as the solution mineralization degree increases, the distribution of pore major-axis azimuth evolves from relative concentration toward dispersion, resulting in attenuated overall orientation and a marked enhancement in microstructural disorder. To further clarify this variation law, the experimental data were fitted using an exponential function, and the corresponding fitting model is obtained as follows:

The fitting results show that the correlation coefficient R2 = 0.997, indicating an extremely high fitting accuracy. This suggests that the exponential model can well characterize the overall trend of probability entropy changing with mineralization degree. From the correspondence between the fitting curve and the actual data, it can be observed that when the mineralization degree increases from 1000 mg/L to 20,000 mg/L, the probability entropy rises rapidly in the relatively low mineralization range, while the growth rate gradually slows down and tends to stabilize in the relatively high-mineralization range. This variation law indicates that the disorder degree of the coal-rock pore system is more sensitive to the change in mineralization degree in the initial reaction stage, but the sensitivity gradually approaches saturation in the high-mineralization region.

Further analysis based on scanning electron microscope (SEM) images demonstrates that an increase in mineralization degree of mine water leads to the fragmentation of the microstructure surfaces of coal rock, with the internal structure arrangement becoming more disordered and the degree of microstructural disorder significantly enhanced, thereby causing significant modifications to the microscopic structure of coal rock.

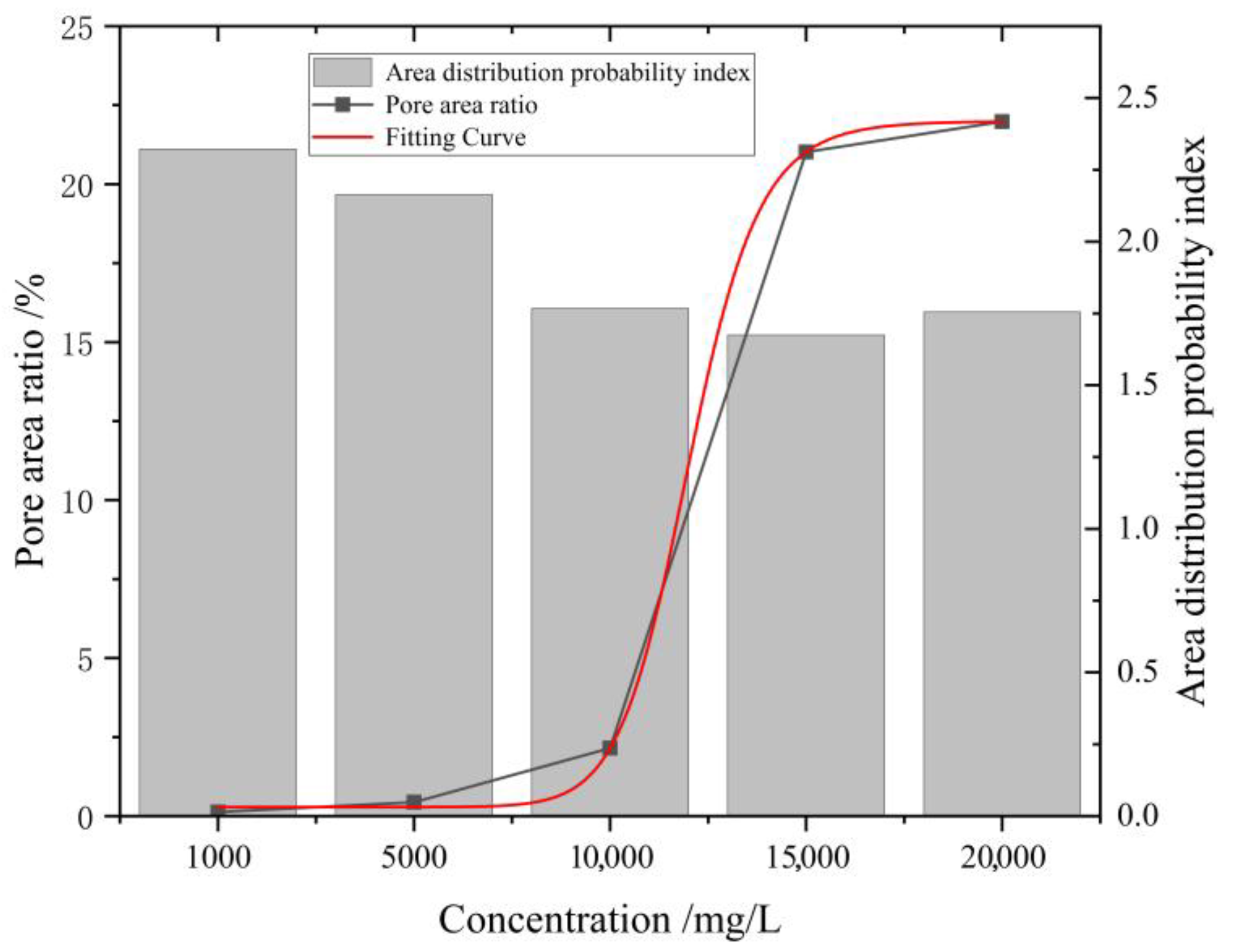

3.6.5. Area Distribution Probability Index

The area distribution probability index is a statistical parameter that characterizes the probability of occurrence of different area units in a system. In the analysis of coal-rock pore systems, this index is used to quantify the degree of dispersion of the area ratio of different pore size intervals. It can reflect the characteristics and patterns of pore area distribution and quantitatively describe the particle area distribution and its density characteristics in specific regions. The formula for calculating the probability distribution function is as follows [

34]:

In the equation,

f(

d) denotes the areal density of pores corresponding to the equivalent aperture

d (μm);

b is the areal distribution probability index, where its value reflects the uniformity of the pore size distribution—a smaller b value indicates a relatively higher proportion of large pores; a is a constant associated with pore density. Based on the equivalent pore size data extracted via PCAS software, the cumulative area fraction N(>d) for different pore size intervals was statistically analyzed. Subsequently, a linear relationship between lg(N(>d)) and lg(d) was fitted in a logarithmic coordinate system, and the power-law index b was derived from the fitted slope. The variation law of b with the mineralization degree is illustrated in

Figure 12.

As shown in

Figure 12, when the mineralization degree increased from 1000 mg/L to 20,000 mg/L, the area distribution probability index showed a trend of first decreasing and then stabilizing. When the mineralization degree was 1000 mg/L, this index was relatively high, indicating that the probability of large particles was lower and small particles dominated; combined with the microscopic image analysis, at this time, the number of pores was relatively small, and the pores identified by PCAS software were mostly small pores formed by the dispersion of primary fractures, thus the index was relatively high. When the mineralization degree rose to 5000 mg/L, the index decreases but remains higher than the index values under subsequent high-mineralization conditions. Based on microscopic images, it can be observed that the number of pores in the coal-rock matrix increases at this point, but they are still predominantly small pores. When the mineralization degree reaches 10,000 mg/L, 15,000 mg/L, and 20,000 mg/L, the index stabilizes at a similar level of approximately 1.75, with a decrease of approximately 20% compared to the relatively lower-mineralization-degree values. Based on microscopic images, it can be observed that under these three higher mineralization-degree conditions, the number of large-area pores is large and accounts for a large proportion, so the area distribution probability index is small.

In addition to the area probability distribution index, this study also performed a statistical analysis on the pore area proportion under different mineralization degrees. The relevant results are illustrated in

Figure 12. When the mineralization degree was 1000 mg/L and 5000 mg/L, the pore area proportion was generally low; when the mineralization degree increased to 10,000 mg/L, the proportion exhibited a significant surge; under the conditions of 15,000 mg/L and 20,000 mg/L, the pore area proportion further increased and tended to stabilize, with the stable range approximately 25%. To further reveal the trend characteristics of the pore area proportion with variations in mineralization degree, a functional fitting was performed on the variation relationship. The fitting curve is shown as the red curve in

Figure 12, and its mathematical expression is as follows:

The fitting results exhibit a typical “S-shaped growth” characteristic, indicating that the pore area proportion presents a distinct nonlinear increasing trend with the elevation of mineralization degree: the variation is relatively slow at the low-mineralization stage, accelerates rapidly after exceeding the critical mineralization degree, and eventually tends to stabilize. This variation law is highly consistent with the microscopic structure observation results—high-mineralization mine water exerts a stronger dissolution, ion exchange, and crystallization induction effect on coal-rock minerals, which promotes the expansion and connection of pores, markedly increases the proportion of large pores, and thus drives the rapid increase in the overall pore area proportion.