1. Introduction

Obstetrics is a medical specialty in which there is a high risk of making clinical errors. The results of an analysis performed by Taniguchi et al. show that obstetrics and gynaecology is fifth in specialties in terms of the frequency of medical errors [

1]. The systematic review results by Klemann et al. showed that 85.2% of errors were caused by poor birth preparedness and poor recognition of risky complications. The most common error was a delay in obstetrical intervention, resulting in foetal hypoxia [

2]. Next, Zhou et al. analysed types of medical errors leading to occurrences of infantile cerebral palsy. Results showed that 88% of the errors were associated with technology [

3].

Moreover, unlike other medical specialties where the health conditions of only a single patient are considered, in obstetrics, a dimension of the decision space is

, where

n denotes the number of decision variables attributed to the mother’s health state, and

m is the number of decision variables describing the health status of the foetus. Thus, the number of health parameters monitored during pregnancy is high. This leads to several cognitive biases affecting obstetrical decisions, which were described by Atallah et al. [

4].

The most critical period of a pregnancy is labour, when obstetricians or midwives should monitor the contractile activity of the uterus, measured by a toco-sensor, and the variability of the foetal heart rate, measured by an FHR sensor. The FHR parameters are used to assess a foetus’s well-being, whereas observation of the uterine contractions helps predict labour progress. Lacking or weak contractions do not produce sufficient force to deliver a baby. The previously cited review showed that misinterpretation of the tocographic signal (TCG) occurred in 38% of the obstetrical errors [

5]. It is also well known that measurements of uterine contraction amplitudes are biased by a patient’s BMI, the location of the toco-sensor, and reduced tension applied to the supporting elastic band bound to a patient’s abdomen [

6]. Moreover, the tension of the rectus abdominis muscle may affect the tocographic signal. Therefore, more robust measures are needed. An alternative method is electrohysterography (EHG), also known as uterine electromyography. It measures the bioelectrical activity preceding mechanical contractions of a pregnant uterus. However, no standards exist for the acquisition and analysis of EHG signals. An excellent review of the state of the art on this problem was provided by Garcia Casado et al. [

6]. Generally, we can distinguish three sources of variation in prediction accuracy between published results, namely, the EHG signal databases used for training and validation of a classifier, the methods of EHG signal parametrisation (EHG features) used as predictors, and the classifier algorithms.

1.1. EHG Databases

There are several EHG databases that are often used to study methods for labour predictions; however, they have some drawbacks.

Firstly, the clinical studies and public databases of EHG signals resulting from these studies do not incorporate any important clinical variables that may confound relations between the studied parameters of EHG signals and the occurrence of preterm labour. In Physionet, there are four public databases containing EHG signals. The greatest, TPEHG DB, has 300 records. The bioelectrical uterine activities were measured via four bipolar channels around the 23rd and 31st weeks of gestation. Of the women, 38 of 300 had preterm labour. The bandwidth of the signals was 0.08–4 Hz, and the sample frequency was equal to 20 Hz. This database also contained the following clinical attributes: maternal age, number of previous deliveries (parity), previous abortions, weight at the time of recording, occurrence of hypertension, diabetes, placental position, first-trimester bleeding, second-trimester bleeding, cervical funnelling, and smoking status. This content may enable us to study the progression of uterine contractions in cases of preterm and term labour. In fact, many women have no measurable uterine contractions before the 35th week of gestation. Thus, we cannot definitively resolve EHG signals if the lack of differences between these groups is due to physiological principles or the inefficiency of studied classifiers. The clinical data allow us to study their influence on bioelectrical uterine activities; however, there is no information about the most important potential confounder, which is body mass index [

7,

8].

The second database is the Icelandic 16-electrode electrohysterogram database, which contains 122 4-by-4 electrode EHG recordings performed on 45 pregnant women using a standardised recording protocol and a placement guide system. The recordings were performed in Iceland between 2008 and 2010. Of the 45 participants, 32 were measured repeatedly during the same pregnancy and participated in two to seven recordings. Recordings were performed in the third trimester (112 recordings) and during labour (10 recordings). The database includes simultaneously recorded tocographical signals, annotations of events, and obstetric information on participants. For each recording, information was noted on participant age, body mass index (BMI), gestational age, placental position, gravidity, parity, history of caesarean section, eventual mode of delivery, and gestational age at delivery. During a recording, the researcher records participant movements, equipment manipulation, participant-reported possible contractions and foetal movements, and any other unusual events. This database has several advantages [

9]. The EHG signals sampled at a frequency of 200 Hz have a bandwidth of 0–100 Hz. This permits the study of all possible components of abdominal bioelectrical signals, including the activity of abdominal muscles. Next, the annotations of uterine contractions and other events affecting EHG signals enable us to extract bursts corresponding to uterine activity or to investigate the robustness of the classifier to signal disturbances resulting from maternal or foetal movements. Moreover, the 4 × 4 matrix of the unipolar electrodes furnishes possibilities to evaluate the propagation of bioelectrical uterine activity or mutual dependency between channels, assuming that the closer the patient is to labour, the greater the synchronisation between EHG channels [

10]. The main limitation of this database is the small number of EHG signals recorded during the active phase of labour. This imbalance of data strongly affects the accuracy of labour predictions. Therefore, there are special methods dedicated for imbalanced samples, such as SMOTE or ADASYN algorithms.

The third database, called TPEHGT DS, consists of 26 records registered during 18 pregnancies, 13 of which ended in premature births, and 13 ended in term labour [

8]. The registered protocols and clinical data are the same as those used in the TPEHG DB because these two databases were created by the same authors. However, the number of records in the TPEHG DS is too small to use for evaluating classifiers. Some researchers merge the TPEHG DB and TEHG DS databases; however, this approach still results in few cases with tocographical signals. These databases have dummy variables tagging uterine contractions. Therefore, researchers can test algorithms that recognise uterine contractions or methods for parametrising EHG bursts.

The newest database, ICEHG DS, consists of 126 records [

8]. The EHG signals were registered in 91 pregnancies. Of these, 59 required oxytocin inductions, and 19 were ended by emergency caesarean sections performed after failed inductions. The 13 pregnancies were terminated by elective caesarean sections. The database also has some clinical data describing the study groups. This is the first database dedicated to the protracted active phase of labours or arrested labours [

10,

11].

1.2. EHG Signal Parametrisation

Unlike tocography, EHG signals are not Gaussian pulses. Therefore, the primary research effort is to identify a set of EHG signal parameters that most closely correspond to the contractile activity of a pregnant uterus. Mostly, this is carried out using a black-box framework, i.e., the researchers use their own or public databases of EHG signals and heuristically select a means of EHG parametrisation. Next, they arbitrarily select a classifier and apply a validation method for evaluating the quality of labour predictions.

We can examine the EHG signal through three pairs of glasses. Firstly, we assume that EHG signals are generated by a linear myometrial system, allowing us to apply commonly used parameters. In the time domain, there are the rms or peak-to-peak values, the autocorrelation zero-crossing, the envelope estimation using rms or Teager–Kaiser energy operators, or Hilbert transformation [

12]. In the frequency domain, the following parameters were studied: modal, mean, median frequency, high power band/low power band ratio, and maximal or mean power spectrum [

6]. The performed studies indicate that the time domain parameters, except for the envelope of the signals, are sensitive to signal noise. In turn, the frequency of EHG parameters is significantly influenced by foetal and maternal heart rates, as well as the mother’s respiratory rate, which can lead to divergent and poor results for labour predictions [

8].

The other view on the EHG signals assumes that they are generated by a nonlinear system of myometrial myocytes. Thus, the parameters describing the nonlinear character of EHG signals are also used. The idea behind them is that when childbirth approaches, bioelectrical uterine activity becomes more regular, i.e., there is less “nonlinearity” in the EHG signals. The following parameters were evaluated: approximate and sample entropy; multiscale and wavelet entropy; maximal Lyapunov exponent; fractal dimension; fuzzy and variance entropy; time reversibility; Hirst exponent; and Lempel–Ziv complexity [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Also, the phase coupling was estimated by a bispectrum or bicoherence [

17].

The third group of EHG parametrisation methods is based on physiological postulation stating that effective labour requires mutually dependent retractions and distractions of the uterine myometrium. Thus, its bioelectrical activity must also be synchronised and propagated from the uterine fundus to the uterine cervix. Having multi-channel EHG measurements, we can estimate and monitor a relationship between them. For this purpose, different parameters were investigated such as a correlation matrix, mutual information, Granger causality coefficients, and time series graph representations via Markov chains [

18,

19]. The most interesting application is the use of resistivity tomography to compute the spatial distribution of bioelectrical potentials on a uterine surface [

20]. This enables the monitoring of bioelectrical wave propagation and, therefore, has significant clinical potential.

1.3. Classifier Algorithms

Similarly, the black-box reasoning approach accompanies classifier evaluation. A studied classifier is selected based on the author’s favourite, and with no scientific reasons. This leads to overcomplicated classifiers without results of the simplest classifier’s performance. Lastly, the most advanced classifiers are often proposed, such as different types of neural networks, supported vector machines, random forests, regression trees, and boosting structures [

21,

22,

23]. In our opinion, such a research trend is unclear. These classifiers approximate a relation between a studied EHG parameter and the probability of uterine activities during labour. If this relation is “weakly nonlinear”, the classifiers will be overparametrised. Similar results of labour predictions obtained for different advanced classifiers suggest that simpler versions may be sufficient, as no advanced classifier specifically fits the studied data.

The final methodological stage involves validating labour predictions. Most published results are actually obtained based on public EHG signals. Thus, there are retrospective case–control studies. Since these databases contain an imbalanced number of cases and controls, with the number of controls typically being small, resampling or cross-validation methods are often employed [

22].

1.4. Methodological Remarks

Although this research methodology seems to be correct, we first draw attention to an important problem. Unfortunately, public EHG databases result in most published papers being written by computer or data science engineers without obstetrical backgrounds. Thus, the clinical usefulness of electrohysterography is evaluated almost only for preterm labour under the assumption that preterm labour must precede uterine contractile activity, which is likely to be physiological labour. However, the most frequently aetiological factor for preterm labours is an intrauterine inflammatory process that produces cytokines [

24]. Thus, in the case of preterm labour, we cannot observe prodromal uterine contractions. On the other hand, the contractions that occur after the 20th week of gestation are a physiological phenomenon, and do not imply preterm labour. Thus, lower accuracy of preterm labour prediction may result from the fact that early occurring uterine contractions are physiologically weakly correlated with the birth date, independent of measurement and classification methods. In our opinion, the clinical usefulness of EHG should be assessed in a longitudinal panel study ending in the second stage of labour. The study time points may be determined by routine USG and CTG visits. Ultimately, a case–control study can be performed where the case group consists of women in the second labour stage and the control group consists of women in the second trimester of a pregnancy. In this study design, the study groups are definitely and physiologically different in the amplitude and frequency of uterine contractions.

The next methodological issue is to find a proper and unbiased “gold standard” for EHG measurements and clinical efficiency assessment. Indeed, some authors proposed different mathematic transformations of EHG signals on tocographical signals [

12,

25]. However, for each function

and

, we can find a transform

such as that

for any closeness norm and any sufficiently small

. However, this does not prove that the transform

represents a real mechanism that occurred in the studied biological system. Other studies have shown a discrepancy in the amplitudes and frequencies of uterine contractions measured via EHG, external tocography, and internal tocography. Indeed, we have three signals representing three different biophysical quantities: electrical potentials generated by uterine myocytes, stresses of the uterine wall, and intrauterine pressure. The relations between them are complicated and nonlinear [

26,

27].

1.5. The Study Aims

In summarising the above considerations, we notice a tendency to complicate methods of estimating EHG features and classification algorithms. However, this tendency does not improve the clinical significance nor clinical application of electrohysterography. Most of the proposed EHG parameters do not have a physiological meaning. Thus, clinicians are sceptical because they do not understand how a given classifier works. Moreover, physiologically unexplainable classifiers require external validations based on different cohorts because we are never sure whether good labour prediction results from yet unknown physiological phenomena or from unmeasured confounders specific to a given database of EHG signals.

Therefore, the primary goal of this study was to evaluate the accuracy of labour prediction based on a physiologically interpreted feature of EHG signals. Additionally, an easily explainable classifier was applied to test whether a simple classifier would yield much less accurate predictions. The secondary aim was to demonstrate that the proposed parameter, when applied to tocographical signals, also yields similarly good results. Achieving this goal enhances the clinical usefulness of the presented method, as tocography remains a clinical gold standard.

3. Results

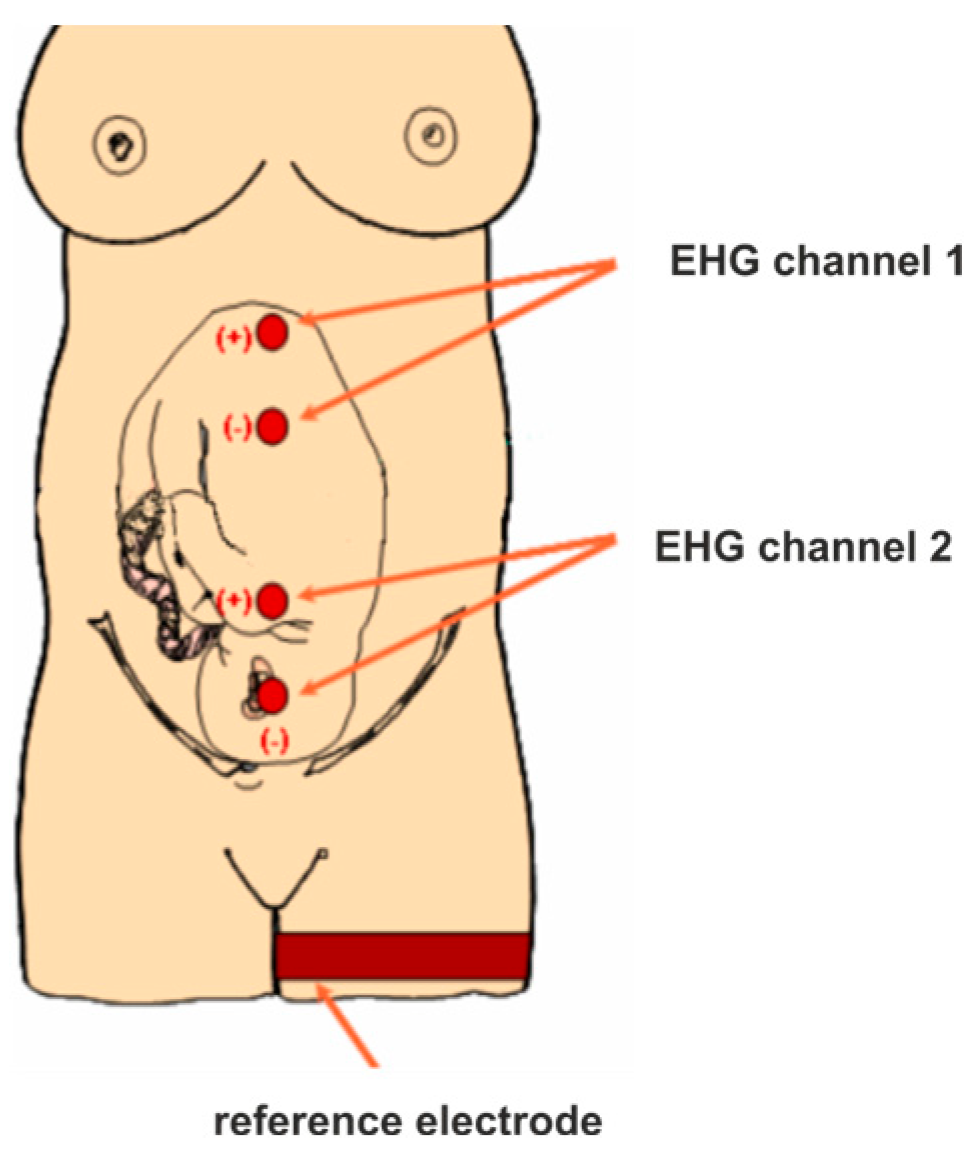

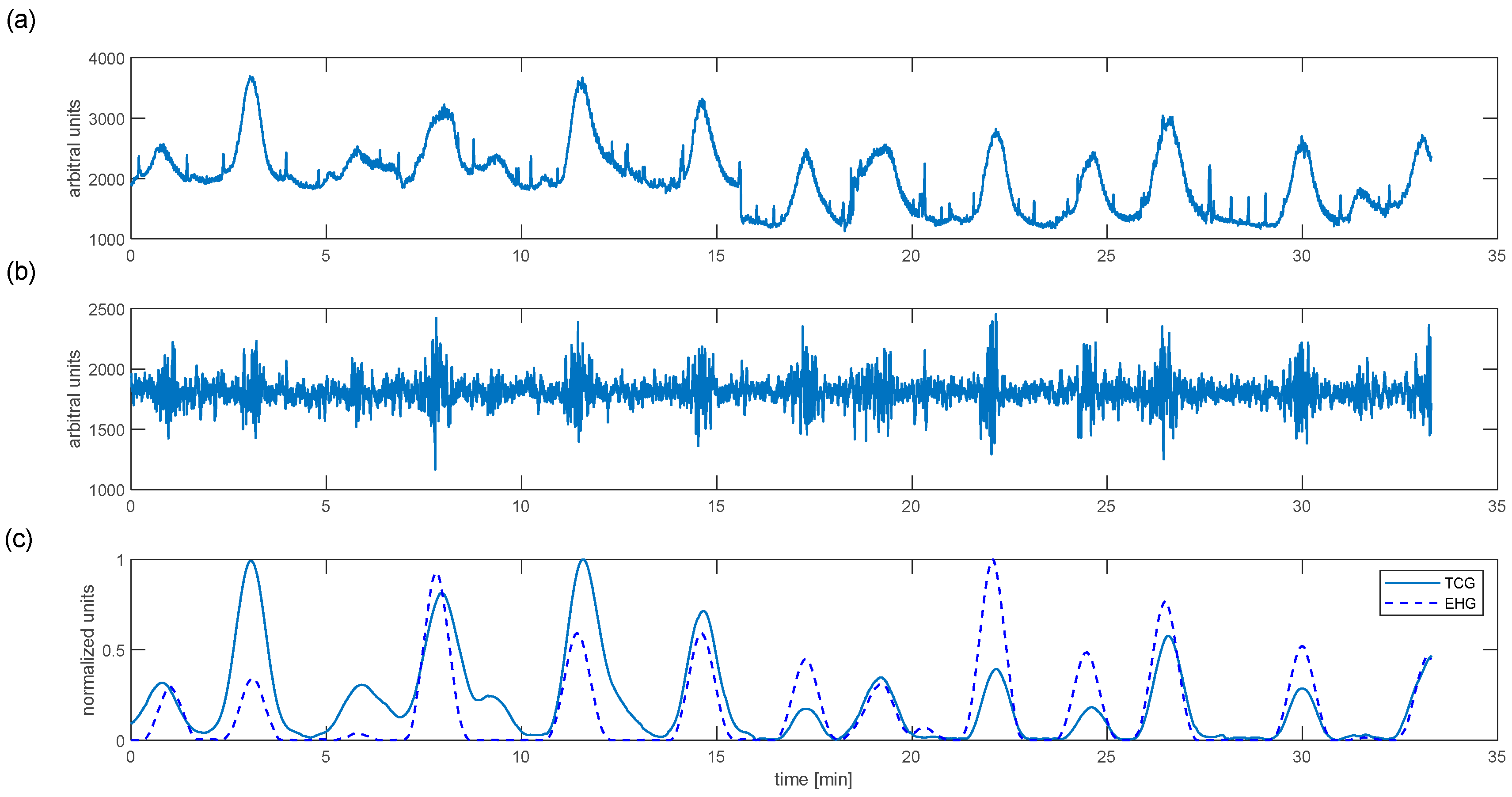

The primary objective of the presented study was to estimate uterine contractile activity based on the electrohysterographical signal. The results of the proposed algorithm for a randomly selected woman at birth are shown in

Figure 2.

We can see that each variation in uterine stiffness detected by a tocodynamometer is associated with the bioelectrical bursts seen in the filtered EHG signal (

Figure 2c). The proposed algorithm enables estimation of mechanical uterine activity based on the EHG signal. The normalised EHG and TCG are timely and synchronous. However, their amplitudes are different. These results are based on the earlier-mentioned anthropometric factors that affect TCG measurements. Moreover, the EHG represents local uterine activity, whereas TCG measures stiffness and movements of the uterine fundus; these also cause discrepancies.

Also, the linearity (Pearson coefficient) and nonlinearity (Spearman coefficient) between

and

were computed. The obtained results are summarised in

Table 1.

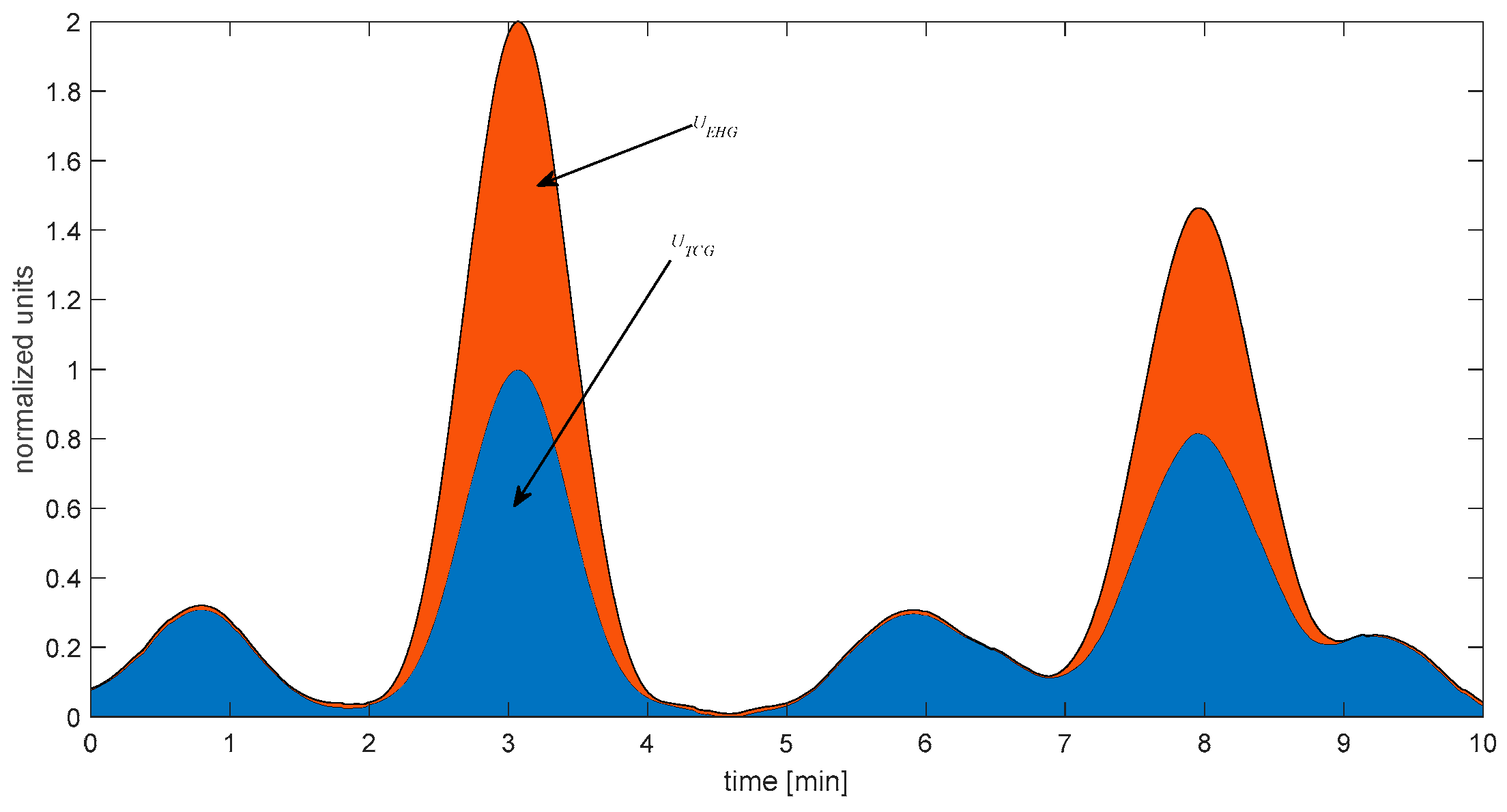

Figure 3 presents the graphical representation of the introduced uterine activity indexes expressed by (4) and computed for the EHG and TCG signals. These indexes have biological meaning because they estimate the energy of uterine contractions that occurred in 10 min.

The proposed classifier and the uterine activity integral minimise false-positive diagnoses of labour. This is not surprising. The detection of high bioelectrical activity in the uterus leads to frequent and muscular contractions. Thus, such a contraction almost always evacuates a foetus from the uterus unless there is a disproportionate birth. Sensitivity associated with the false-negative rate is most important from a clinical point of view. It means that a woman has undetected labour contractions and frequently qualifies for induction of labour via administration of oxytocin. Since tocography (mainly in obese women) underestimates the strength of contractions, the oxytocin dose usually is increased. Consequently, tachycardia of the uterus blocks blood flow via the uterine and placental arteries, leading to foetal hypoxia at birth. The proposed classifier yields a false-negative rate of less than 10%.

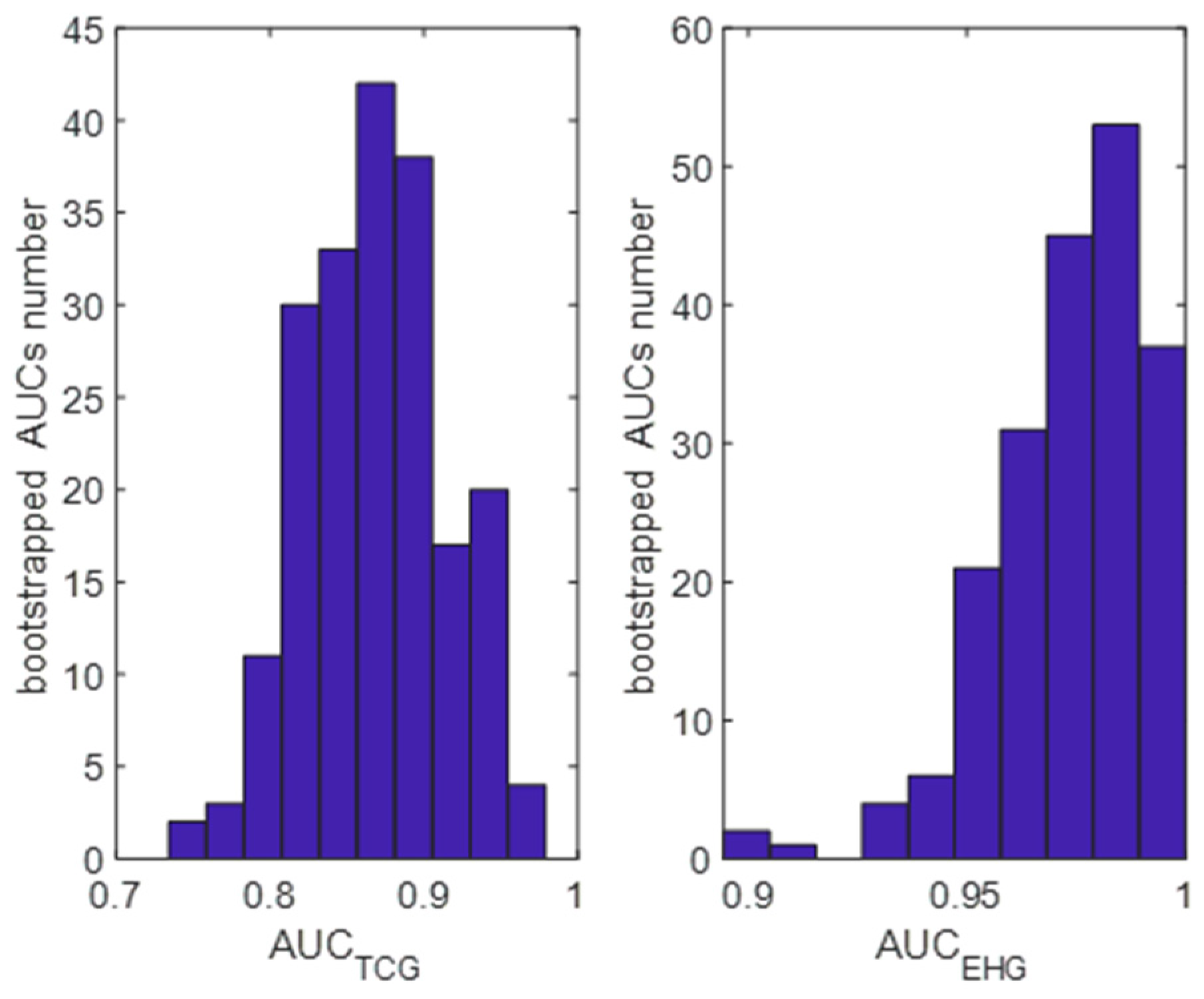

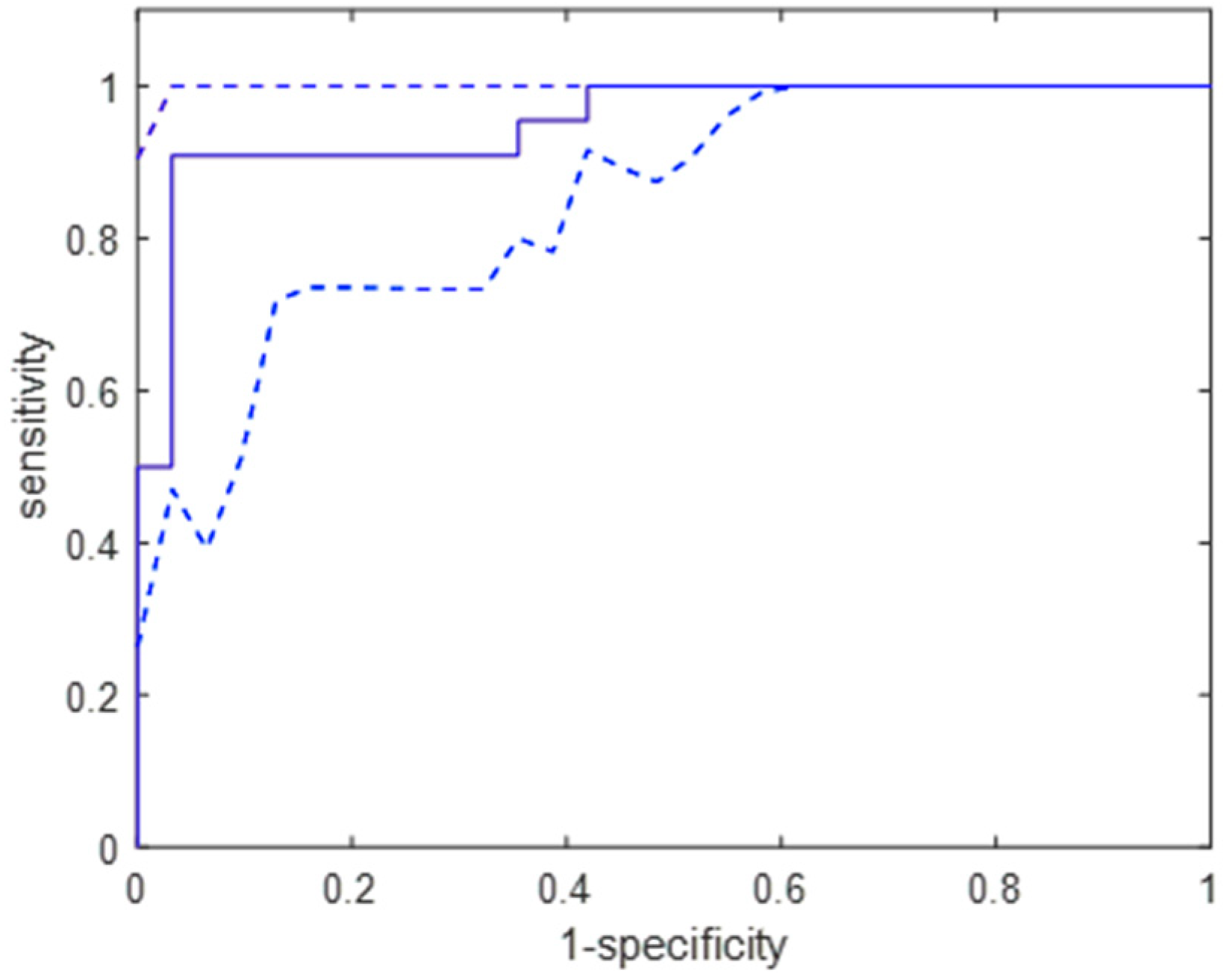

The performed bootstrapping experiment confirmed that the studied group had been appropriately selected because the classifier applied to TCG signals in the bootstrapped sample detected almost all parturient women.

Figure 4 presents the distribution of the AUC values obtained for the studied classifier using the bootstrap samples. The mean (95% confidence intervals) were 0.86 (0.73–0.93) for the TCG signals and 0.96 (0.91–0.99) for the EHG signals. We can see significant differences in the distribution shapes, suggesting that the uterine activity integral index computed for the processed EHG signals results in better labour detection.

The confusion table shows misclassifications for a random bootstrapped case (

Table 2). Thus, the sensitivity is 96%, and the specificity is 93%.

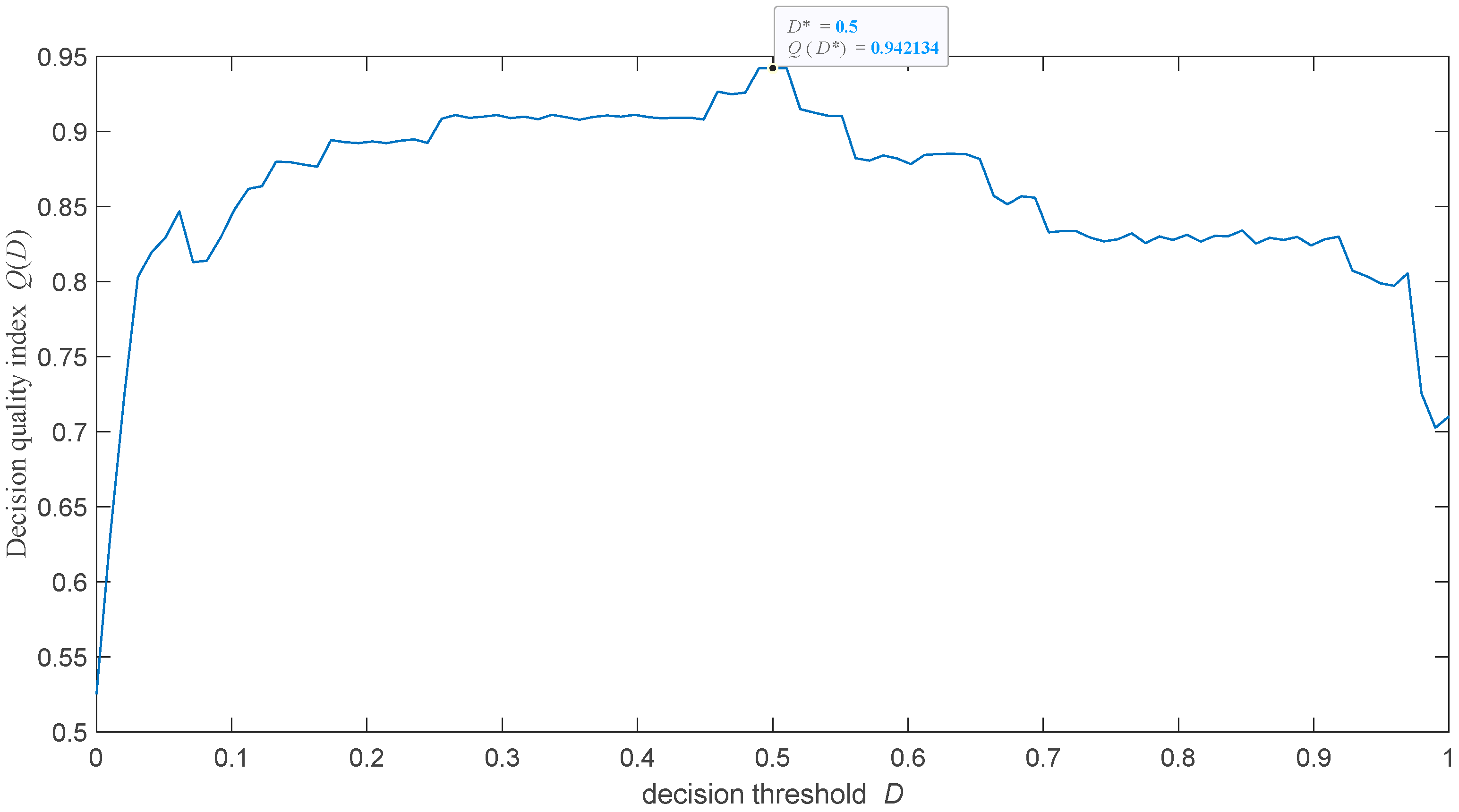

The study’s next step was to test how the selection of the decision threshold affects the detection of uterine activities during labour. It was postulated that the optimal threshold value should maximise the following decision quality index:

where the mean and the standard deviation of AUCs are computed for the bootstrapped sample EHG signals parametrised by the uterine activity indexes (4). This ensures a trade-off between the accuracy and precision of labour contraction diagnoses. Formula (12) was optimised by searching the solution set.

Figure 5 presents the function. We note that the decision threshold of a priori set to 0.5 is optimal.

It is interesting that the accuracy of the proposed classifier weakly depends on its decision threshold (

Figure 6). This advantage stems from a linear, statistically significant (

p < 0.03) relation between the uterine activity integral computed for an EHG signal and the odds of uterine contractions during labour.

Additionally,

Figure 7 presents an example of the biomechanical and bioelectrical activity of the uterus during the third stage of postpartum.

Figure 7 also confirms the similarity between the TCG and processed EHG signals. There are no frequent and prolonged contractions. However, some “impulse-like” contractions lead to expulsion of the placenta. These expulsive contractions result from the double bioelectrical activity, ensuring the necessary “pushing”.

4. Discussion

Management of labour is one of the pivotal challenges of modern medicine. The epidemiological data collected in the American public health registers indicate that around 30% of labours require some obstetrical interventions such as oxytocin induction, vacuum application, or caesarean sections [

33]. These cases probably result from the fact that older and more obese women are bearing their first children. Considering the increase in body mass indexes, it seems that palpable examinations and classical tocogragraphy would need to become more clinically useful. The FDA approved electrohysterography for clinical settings and recommended it for obese women instead of tocography.

Therefore, methods intended for monitoring pregnancies and labour are still being studied. However, we noted several important drawbacks of the performed studies, which lead to great confusion in the interpretation of the results. We observed a surge in studies testing different machine-learning algorithms on EHG or CTG signals collected in public databases. These are only retrospective studies not designed by the authors. In the case of EHG research, the study endpoint is the occurrence of preterm labour, assuming that this endpoint must causally precede early uterine activity. However, in some cases, this assumption may be violated. The most frequent aetiological factor of preterm labour is intrauterine inflammation, which immediately spreads and induces a cascade of pro-inflammatory reactions, producing cytokines and prostaglandins that stimulate uterine contractions. Then, preterm labour does not precede early uterine activity. Thus, lower accuracy in predicting preterm labour may result from pathophysiology but not from EHG parametrisation and classifier typing.

On the basis on the review performed by Garcia-Cascado et al., we note that accuracies in labour prediction obtained for the most nonlinear classifiers are similar (AUC > 0.85) [

6]. From a clinical epidemiological perspective, diagnostic or screening tests with AUC values exceeding 0.8 are considered clinically sufficient [

34]. However, these results appear to be overly optimistic. They were obtained using a very imbalanced TPEHG database and applying oversampling techniques before partitioning EHG signals into the training and test sets. The analysis performed by Vandewiele et al. provides interesting results. They show that oversampling applied before partitioning produces significant overestimation of classification accuracy. If this was applied to both the test and training sets, the accuracy, measured as AUC, would not exceed 0.55 [

35].

Moreover, all advanced classifiers approximate a nonlinear relation between EHG parameters and labour prediction (usually preterm), although in a different way. Thus, for “weak” nonlinearity, these classifiers will, in principle, yield similar results. This is nihil novi. Therefore, the principle of Ockham’s razor, expressed by the information criteria, should be used.

Unfortunately, the most recently proposed classifiers belong to black-box models. Indeed, knowledge of fertility and birth mechanisms is still incomplete but many factors and relations between them are known. Thus, it appears that gray-box-based classifiers would be more effective. Such classifiers are consistent with the concept of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). A computer-aided diagnostic system (CAD) is interpretable if its parameters, in particular, decision variables, have biological or clinical meaning. Moreover, such a system is explainable when the outcome prediction for a given patient performed by this system is understandable to medical staff. AI researchers rightly distinguish two types of explanation. Explanation ante hoc (explanation by design) requires the incorporation of biological or clinical knowledge into building a CAD system, leading to gray- or even white-box models [

36]. Clinical decision making is a balance of experience, awareness, knowledge, and information gathering, utilising appropriate assessment tools, consulting with colleagues, and applying evidence-based practice. Since many medical health providers are unable to provide rational justifications for their decisions, we strongly recommend applying careful participant observations to identify variables and factors enabling proper clinical decision making [

37]. CAD systems based on explanation ante hoc usually use Markov chains, probabilistic nets, or decision trees. On the other hand, an explanation can also be provided post hoc when a theoretical and functional background is found that explains the influence of decision variables on the predicted outcome [

38]. Such CAD systems are based on so-called

glass-

box models because the decision process is transparent for users. However, we stress that these CAD systems are exposed to confirmation bias [

39].

The disadvantages of classifiers proposed for predicting childbirth drew attention in 2024 Pirnar et al. They strongly criticised the use of increasingly complex classifiers based on black-box models, showing that the greater compilation of EHG parameters and classification algorithms does not significantly improve the accuracy of predicting uterine contractions during labour. Thus, they proposed the simple classifier basing the peak amplitude of the normalised EHG power spectrum computed in the passband of 0.15–0.575 Hz. This parameter seems to be associated with the dynamics of bioelectrical processes occurring in the myometrium [

40].

Fully agreeing with Pirna’s criticism, we proposed the physiologically explainable-by-design classifier to predict labour contractile activity based on EHG signals. This classifier is interpretable because the introduced uterine activity index has a biophysical interpretation. It estimates the total energy of uterine contractions lasting 10 min. Also, our classification algorithm is explainable because we apply the well-known logistic regression model, and the association between the uterine activity index and labour contractions is related to the biomechanics of labour. Moreover, the presented classifier was tested on a group of women with physiological pregnancy and physiological deliveries at term to avoid confounding factors associated with preterm birth. The case and control groups were almost balanced in terms of the numbers of patients and potential confounders. The obtained results support the hypothesis formulated by Pirnar et al. that a simple physiologically explainable classifier can achieve prediction accuracy comparable to that of more complex numerical models [

40]. This was also confirmed by the statistically significant correlations between EHG and TCG parameters. This study also shows for the first time that predicting uterine activities during labour based on TCG and EHG yields comparable results. This finding aligns with previous investigations, which have indicated a similar number of contractions detected by these two methods [

41], supporting the potential application of electrohysterography in obstetric practice.