4.1. Dataset

In our experiments on skin lesion image classification, we employed the ISIC 2018 dataset [

57], specifically Task 3—skin lesion classification. This dataset was collaboratively developed by dermatology experts worldwide, comprising a large collection of annotated skin lesion images. It contains 11,720 high-resolution images categorized into seven classes: vascular skin lesions (VASC), melanocytic nevi (NV), dermatofibroma (DF), benign keratosis (BKL), melanoma (MEL), basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and actinic keratosis (AKIEC). Representative images from these seven categories are displayed in

Figure 4. All images in the dataset have a resolution of 600 × 450 pixels, which were resized to 224 × 224 pixels for our experiments.

The dataset was split into 8715 images for training, 1493 for validation, and 1512 for testing.

Table 1 delineates the data partitioning scheme and the corresponding class distribution. As evidenced in

Table 1, the ISIC2018 manifests severe class imbalance across all partitions, with this challenge being particularly pronounced in the training set. Among the training samples, the NV category constitutes the majority, accounting for approximately 67% of the total samples. In contrast, the DF, VASC, and AKIEC categories collectively represent less than 6% of the training data. MEL, being the clinically most critical malignant category, comprises 11% of the training samples yet remains outnumbered by NV samples by nearly a 6:1 ratio. This extreme class imbalance predisposes the model to exhibit bias toward majority classes during training, consequently compromising its recognition capability for minority classes. This substantial data challenge constitutes the primary motivation for our research.

4.2. Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted on a GeForce RTX 4090D GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with 24 GB of memory, and the models were implemented using the PyTorch 1.10.0 framework. Regarding weight initialization, we initialized the Swin-B backbone by loading pre-trained weights from the ImageNet-22k dataset, while for the newly added modules, we adopted PyTorch’s default Kaiming Normal Initialization method. After multiple rounds of manual hyperparameter tuning on the validation set, we determined a stable and optimal parameter configuration. During training, AdamW was adopted as the optimizer for the proposed MaLafFormer model. The training was performed for 100 epochs with a batch size of 32, an initial learning rate of 1 × 10

−4, a minimum learning rate of 1 × 10

−6, and a weight decay coefficient of 1 × 10

−4. The first five epochs were set as a warm-up phase, followed by a cosine decay strategy to automatically adjust the learning rate. The detailed parameter settings are presented in

Table 2. To enhance the generalization capability of the model, we applied data augmentation to the training images, including random cropping to 224 × 224 pixels, as well as random horizontal flipping (probability: 0.4), random vertical flipping (probability: 0.3), and random rotation with an angle range of ±15° (probability: 0.6).

During training, we employed an Early Stopping strategy for all models. Specifically, after the completion of each training epoch, we calculated the loss value on the validation set and saved the model checkpoint that exhibited the minimum validation loss. All results reported in this paper are derived from the checkpoint that achieved the minimum loss on the validation set. This method of selecting the best checkpoint based on validation set performance ensures that the reported results reflect the model’s optimal generalization ability on unseen data, thereby safeguarding the impartiality of the experimental findings.

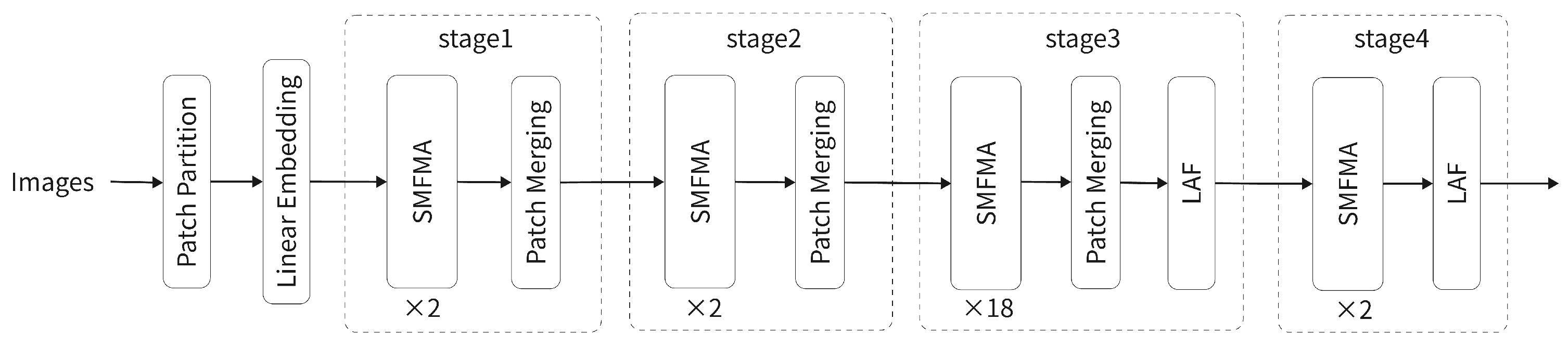

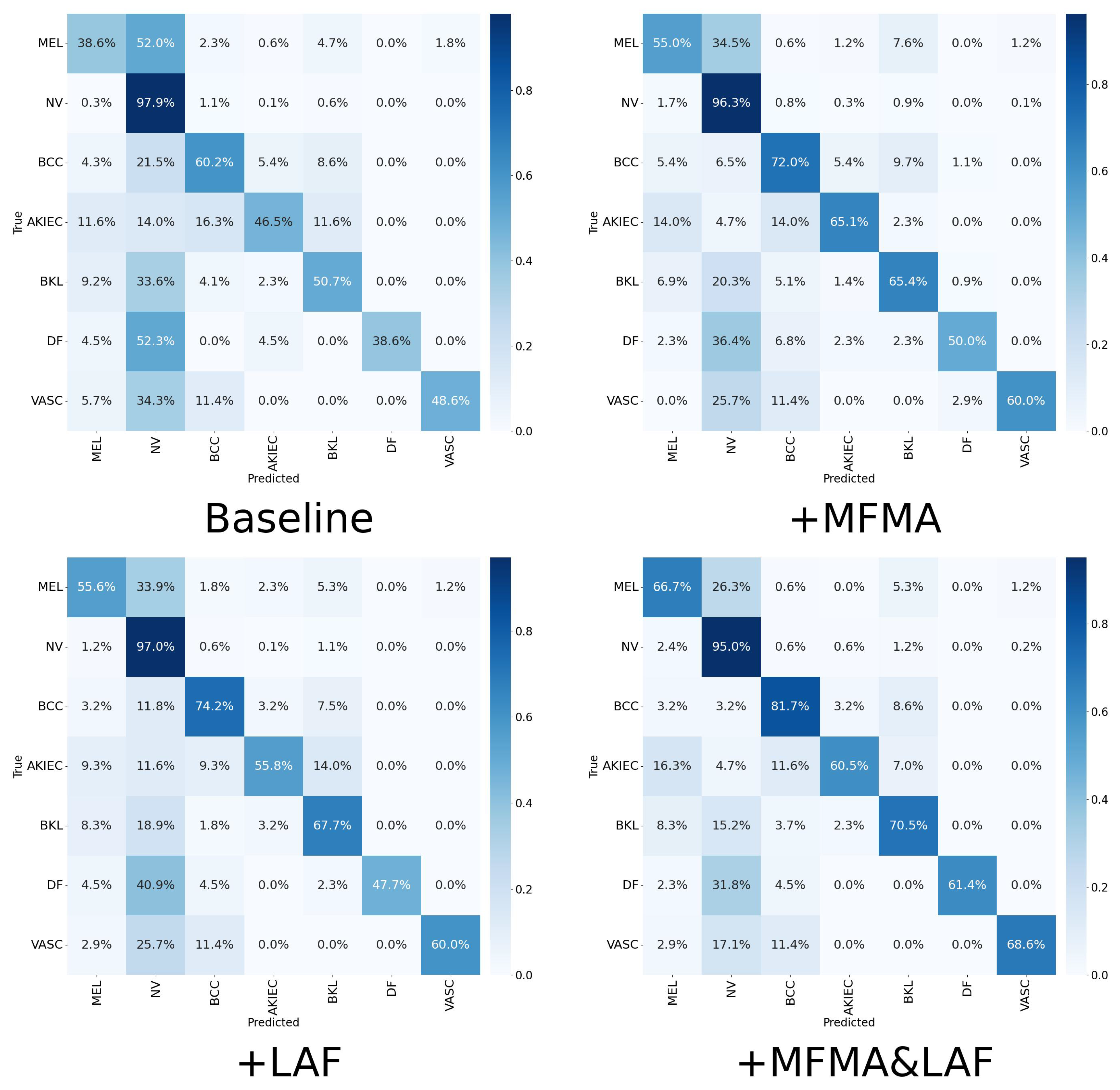

4.3. Ablation Study

The MFMA and LAF modules are the two key components of the proposed model. To validate their effectiveness, ablation studies were executed on the ISIC2018 dataset for the skin lesion classification task, thereby allowing for the assessment of each component’s impact on the final performance metrics. Our baseline is Swin-B and all experiments used the parameter configuration described in

Section 4.2. To verify robustness, we repeated every method three times with seeds 42, 217 and 3407. All metrics in

Table 3 are reported as average ± standard across these three runs.

As shown in

Table 3, incorporating the MFMA and LAF modules improved the model’s classification accuracy by 4.41% and 5.20%, respectively. Specifically, the MFMA module establishes connections between feature layers through multi-scale global pooling and cross-layer feature fusion, thereby enhancing inter-layer contextual modeling capability and improving the perception of the overall image structure. The LAF module performs fine-grained local modeling of feature maps via channel grouping and local attention mechanisms, which strengthens the model’s ability to discriminate key regions and to perceive lesion boundaries.

Furthermore, when both MFMA and LAF modules are incorporated, the model achieves optimal performance, reaching an average classification accuracy of 84.35%, representing a 6.37% improvement over the baseline model. Precision, Recall, and F1 score are also significantly enhanced. This indicates that MFMA and LAF contribute complementarily to the model’s classification outcomes. MFMA strengthens global semantic understanding, while LAF focuses on local salient regions and boundary structures. Together, they synergistically enhance the model’s classification performance.

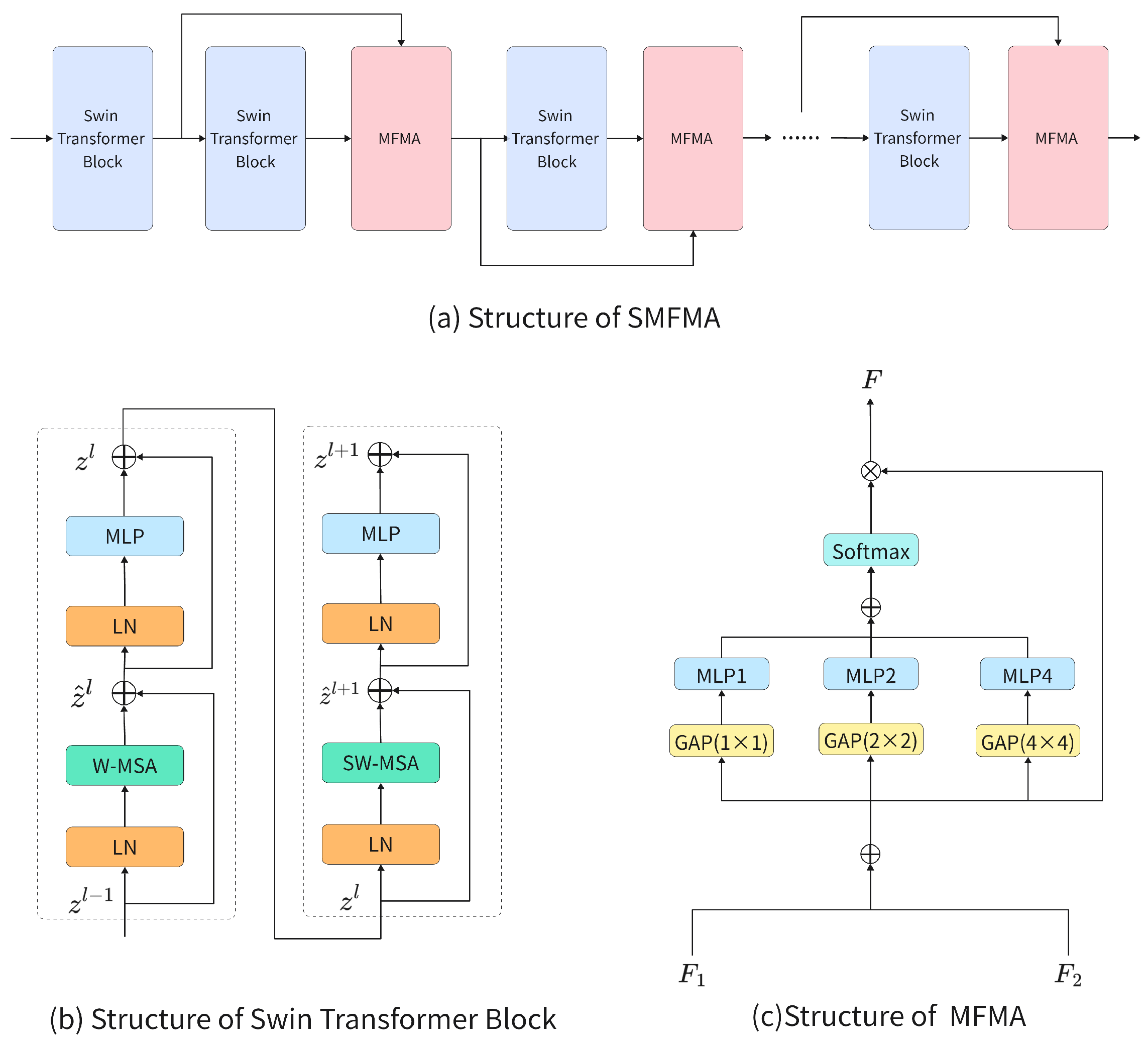

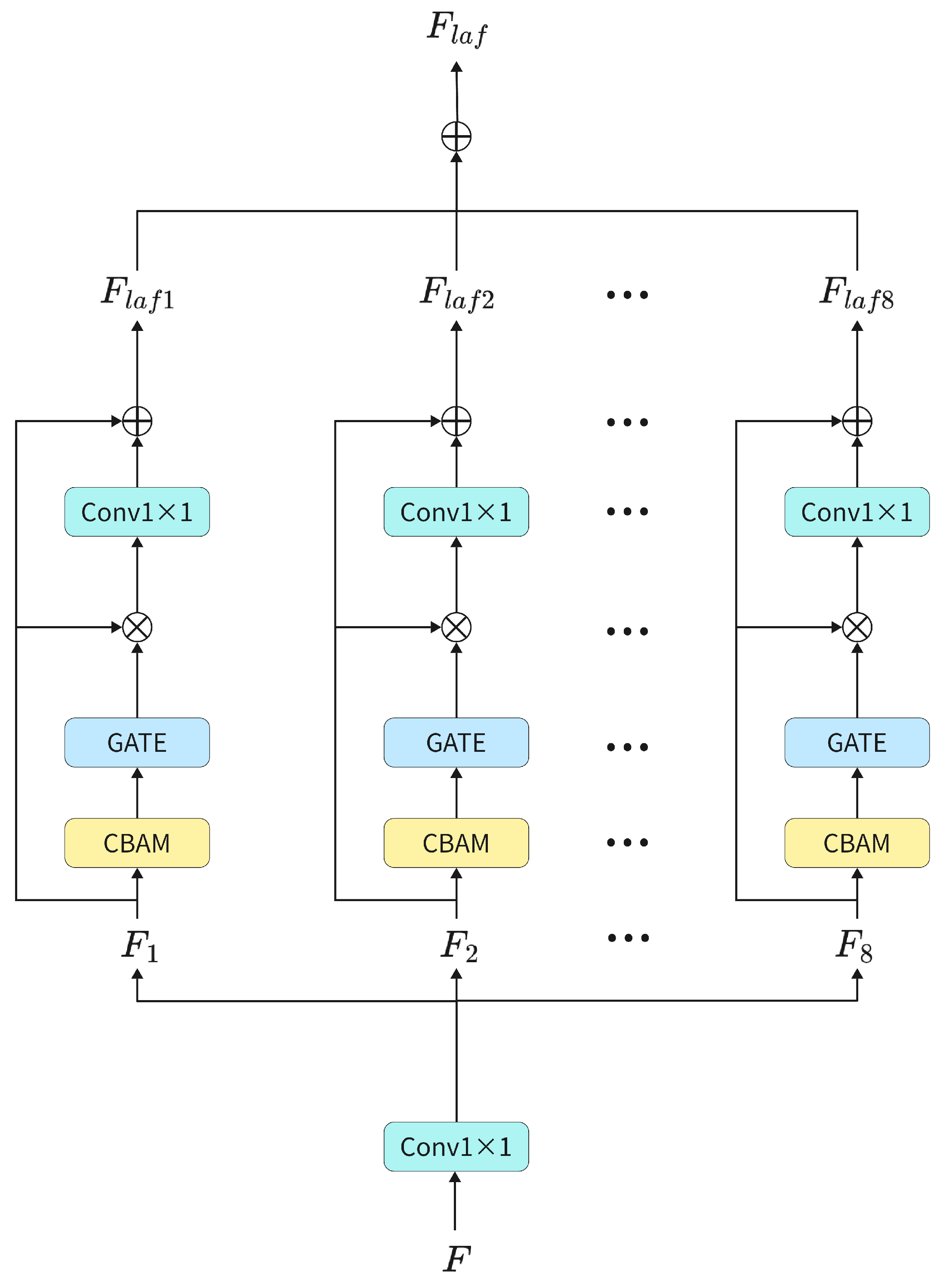

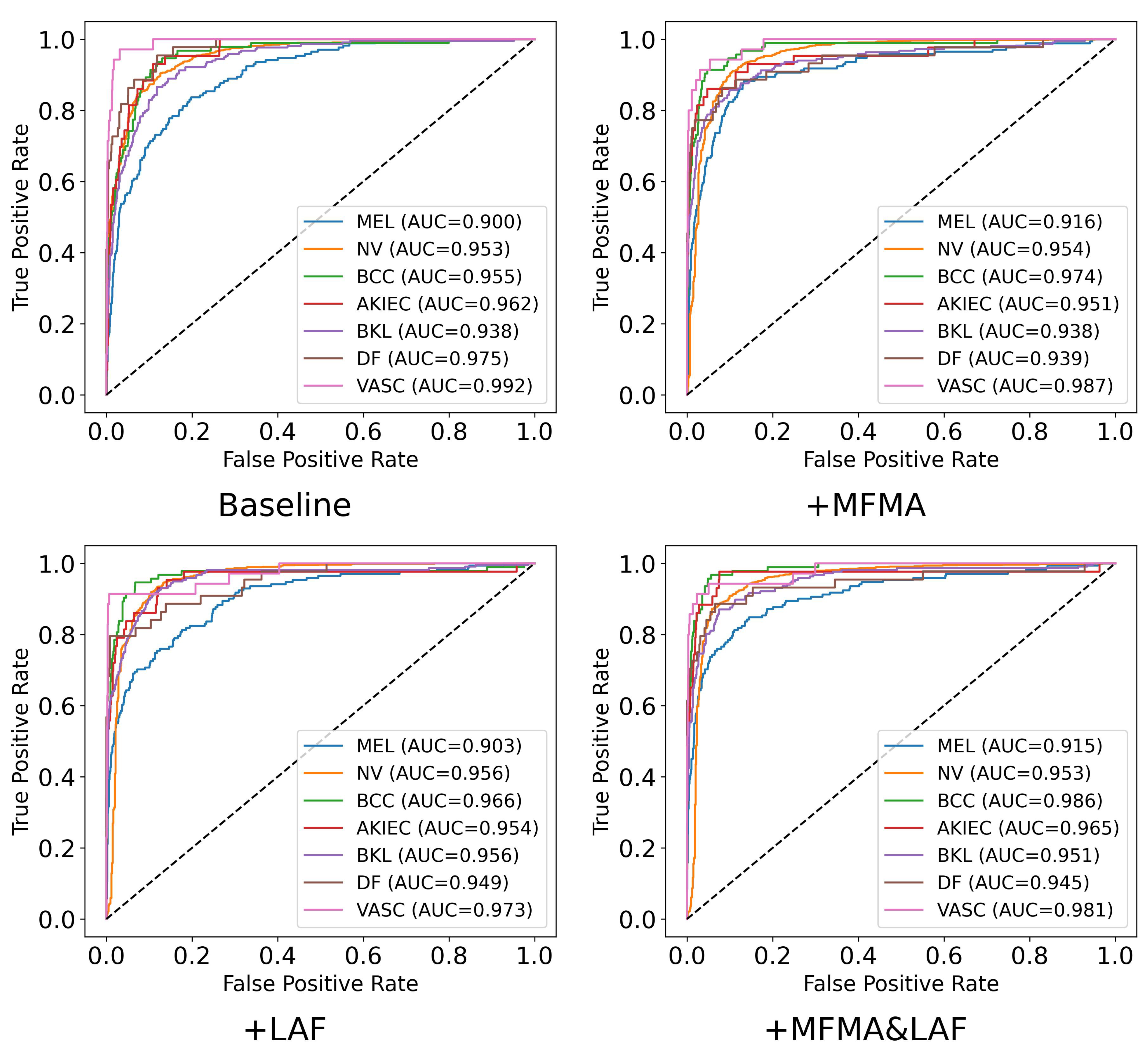

To further explore the specific performance of the MFMA and LAF modules across the seven diagnostic categories, particularly the clinically important MEL, we present in

Table 4 the precision, recall, F1 score, specificity, and AUC achieved by each method. The corresponding confusion matrices and ROC plots are shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. To ensure clarity and facilitate comparison, the results in

Table 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 are from a single run with seed 42. As shown, when MFMA and LAF are introduced separately, the model achieves better classification metrics than the baseline model for most categories. For MEL, the baseline model achieves a recall of only 0.386, clearly exposing its substantial deficiency in identifying this key minority class. After introducing MFMA, the recall for MEL increases to 0.550, while incorporating LAF results in a recall of 0.556, demonstrating the effectiveness of both modules.

When MFMA and LAF are jointly deployed, the model achieves the best overall performance, especially for the critical categories of MEL, BCC, DF, and VASC, where its recall and F1 are the highest among all methods. This indicates that the combination of MFMA and LAF exhibits a strong synergy, most effectively enhancing the model’s ability to capture positive samples and its overall performance. Notably, MaLafFormer attains the highest recall of 0.667 and F1 score of 0.677 on MEL, the most clinically significant category. Compared with the baseline, recall increases by 0.281 and F1 by 0.193, suggesting a substantially reduced risk of missing fatal cases. Meanwhile, for the most prevalent category of NV, MaLafFormer maintains a high F1 while achieving a specificity of 0.829, effectively lowering the risk of mistakenly excising benign lesions. In addition, for the rare but highly malignant BCC, MaLafFormer raises recall from 0.602 to 0.817, significantly contributing to the early detection of this cancer.

In addition, we employed Grad-CAM to visualize the layer preceding the classification head of the model, allowing the model’s attention regions to be depicted through heatmaps. Grad-CAM visualization results for selected skin lesion images are presented in

Figure 7.

It can be observed that, for the baseline model, the attention distribution is easily affected by the background, making it difficult to consistently focus on the lesion regions, with some lesion areas receiving low attention. After introducing the MFMA module, the heatmaps show a significant enhancement of feature responses across the global context, allowing the model to better capture the overall lesion. However, there is also some over-attention to irrelevant areas, indicating that while this module improves global feature modeling, it struggles to focus on key regions. With the addition of the LAF module, the model demonstrates stronger local attention, forming high-response areas in the core lesion regions and covering most of the lesion, showing more precise localization of local target areas, although the overall coverage is still somewhat limited.When both the MFMA and LAF modules are simultaneously incorporated, the heatmaps show coverage of the entire lesion structure while accurately localizing the core lesion regions. This demonstrates that the model not only possesses strong global semantic understanding but also sensitively perceives lesion boundaries, achieving comprehensive and precise attention to the lesion areas.

This coordinated attention to both global and local information enables the model to perform more stably and accurately in identifying lesion boundaries and distinguishing between similar classes, further validating the complementary role and effectiveness of MFMA and LAF in feature modeling.

4.4. Comparison with Other Models

We selected six representative image classification models as comparison models, including VGG-19 and ConvNeXt based on CNN architecture, ViT and Swin based on Transformer architecture, and MedMamba and VMamba from the Mamba series. Experiments were conducted on the ISIC2018 dataset, and the overall classification results are shown in

Table 5.

The evaluation results in

Table 5 show that the proposed method achieves the best performance in ACC, Precision, Recall, and F1 score. Compared with the ViT and Swin models, MaLafFormer improves classification accuracy by 13.76% and 7.14% respectively. It also outperforms the CNN-based models VGG-19 and ConvNeXt in classification performance. Compared to VMamba, which has a similar parameter scale, MaLafFormer achieved better performance in terms of accuracy with a 14.48% advantage.

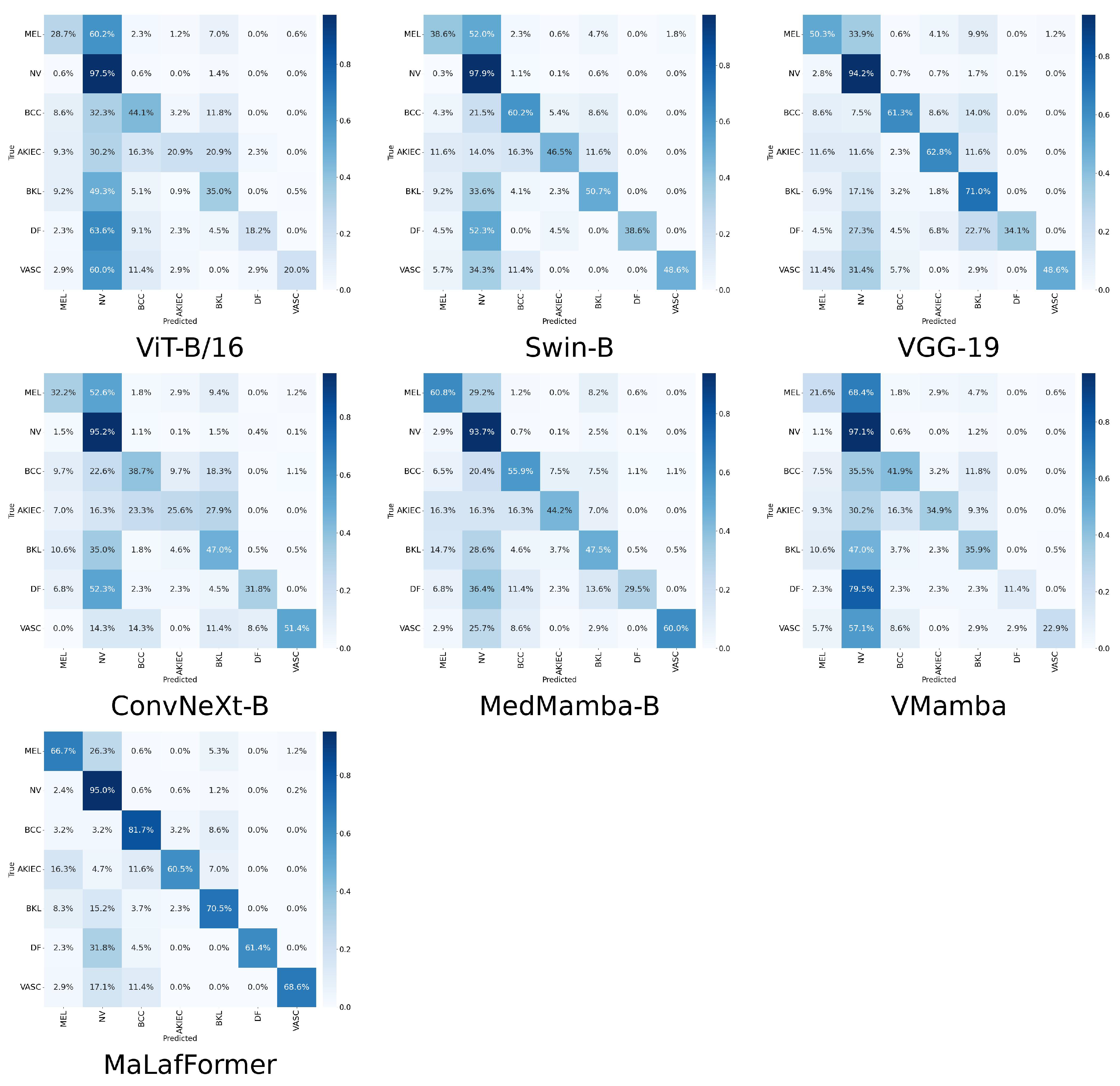

To provide a comprehensive comparison of model performance at the category level,

Table 6 presents the per-class precision, recall, F1, specificity, and AUC for all models across the seven lesion categories of the ISIC2018. The corresponding confusion matrices and ROC plots are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. Overall, our MaLaFormer demonstrates leading performance across all categories, indicating a robust and generalized capability with no apparent weaknesses on this dataset. Specifically, for MEL, the category with the highest fatality rate, MaLaFormer achieves the highest scores in precision, recall, F1, and AUC while maintaining a specificity of 0.961. Compared to all competing models, MaLaFormer attains the highest specificity for the NV, which has the largest number of samples, suggesting its potential to effectively reduce unnecessary biopsies. Even for the categories with extremely limited samples, namely DF and VASC, our model maintains a recall greater than 61%, confirming its sensitivity to rare lesions. In contrast, models such as VGG-19, ConvNeXt, and MedMamba exhibit relatively low precision and recall rates for most categories. Meanwhile, ViT and Vmamba appear to be significantly influenced by the majority class, resulting in degraded classification performance for other classes.

These results indicate that MaLafFormer effectively improves the model’s discriminative ability and feature expression ability without relying on a massive increase in parameters or computational complexity.In the comparison of skin lesion classification datasets, it achieves better diagnostic performance than other methods.