1. Introduction

Fabric cutting, sewing assembly, and garment pressing are the basic production activities in the garment manufacturing business that put workers at risk of developing work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs). These problems result from the long-term impact of repeated actions, sustained uncomfortable postures, and prolonged labor in ergonomically unfriendly settings. Specifically, when cutting curves, cloth cutters frequently bend and twist their wrists and torsos [

1]. Then, the sewing machine operator sews the cut fabric together. Sewing operators often sit at their workstations and lean forward to sew for long periods of time. Common ergonomic difficulties with sewing machines include forward head protrusion, elbows over shoulder height, and a curved back. Long-term use of these positions can result in neck, back, and other issues. Garment pressing operators adjust and press the cloth to improve garment fit, applying pressure to the wrists and torso. The risk of WMSDs increases with each year of service as discomfort increases. Therefore, given the significance of garment manufacturing in the industrial environment, garment worker ergonomic assessments are useful. Such approaches can enhance working conditions, reduce WMSDs, increase productivity and quality, and support industrial growth. However, most research on this population has been conducted through cross-sectional surveys [

2], with a conspicuous absence of long-term cohort data and evaluations of intervention effectiveness.

Existing ergonomic assessment methods for WMSDs focus primarily on posture analysis. These approaches assess joint angles, duration, and repeat frequency of work postures to detect potential occupational risk factors. It normally consists of two parts: posture measurement instruments and risk assessment analysis. There are two types of posture measurement tools: nonvisual and visual. Nonvisual methods leverage wearable sensors to capture high-precision human motion data. For instance, Zhang et al. [

3] used data from IMU sensors and recorded posture levels to find body positions that could cause muscle and bone disorders. They also measured how often and how long these postures were held to determine risk levels. Yu et al. [

4] employed surface electromyography (sEMG) technology to simulate repetitive manual material handling tasks performed by workers. Their goal was to study how muscle tiredness changes when the body rotates to different angles, and how this connects to WMSDs. Weston et al. [

5] tried a new method for recognizing postures. They used NIRS sensors to check oxygen levels in muscles. This helps show how much load a particular posture puts on muscles. However, all these methods need people to wear multiple devices for long periods to obtain full data [

6]. It can limit natural movement and cause discomfort. During demanding tasks, it may lower work efficiency and raise privacy concerns [

7]. Also, it is hard to always place sensors in the exact same way. This creates technical problems like timing errors and unstable signals [

8]. Because of these issues, wearable sensors are mostly used in labs instead of real factories.

Visual-based methods, such as depth cameras, enable real-time detection and tracking of 3D skeletal models for dynamic posture monitoring. Li et al. [

9] used Kinect v2 to collect skeleton data from construction workers. Their system recognizes postures instantly and checks physical load. It provides continuous warnings instead of needing human supervisors. Similarly, Zhou et al. [

10] applied Kinect v2 to study human motions. Their approach uses machine learning to classify postures and determine risk levels. However, depth cameras have a limited working distance. For example, Kinect v2 works best within 4.5 m. This narrow range restricts their coverage in large work areas. They also use a lot of power and have relatively low image quality, making them less suitable for some industrial uses. Regular RGB cameras have a wider field of view. They can capture multiple workers across big spaces without interrupting work. Yang et al. [

11] used a Bag-of-Features method to recognize movements from video. Ding et al. [

12] built a CNN-LSTM deep learning model that detects risky behavior automatically. These studies indicate that computer vision can accurately estimate human body posture. This technology has great potential in assessing ergonomic risks in the workplace.

With the rapid development of deep-learning–based object detection, YOLO architectures have become widely used for real-time human monitoring in industrial environments. Recent work has demonstrated that incorporating attention mechanisms into YOLO can significantly enhance feature discrimination under occlusion, cluttered backgrounds, and small-scale target conditions. For example, Wang et al. integrated a channel–spatial attention mechanism into the C3 module of YOLOv5 and reported notable improvements in detecting small objects while maintaining real-time performance [

13]. In parallel, the emergence of computer-vision–based ergonomic risk assessment (ERA) has shown that 2D human pose estimation combined with scoring systems such as RULA can achieve accuracy comparable to expert evaluations in real workplaces, as demonstrated by Agostinelli et al. [

14]. Furthermore, a recent comprehensive review highlighted that pose-estimation-driven ERA has become a key direction in occupational health research but also pointed out that most existing systems are developed for general industrial or office settings and lack domain-specific adaptation for tasks involving fine hand–arm movements and frequent occlusions [

15]. These findings underscore the need for a specialized, attention-enhanced, and ergonomics-oriented vision system tailored to the garment manufacturing environment.

However, despite the progress made by these existing methods, the complexity of the clothing manufacturing environment increases the challenge of human pose estimation. In sewing, the machine and piles of cloth often block the view of the lower body and hand joints. Because of this, the small, precise hand and arm movements used in sewing can be hard to detect correctly. Moreover, the fast-paced, assembly-line nature of garment production imposes stringent real-time requirements on posture assessment systems, which must rapidly and accurately identify ergonomically risky movements to enable timely intervention. But traditional ergonomic assessments or models with low frame rate are inadequate for the requirements of garment production floors. Therefore, it is important to design a task-specific integration scheme that can handle these garment-industry characteristics.

To address these limitations, the main contributions of this work are threefold:

(1) We design a scene-adaptive attention-enhanced detection framework (YOLO-SE-CBAM) specifically optimized for occlusion patterns, textile clutter, and upper-limb visibility challenges unique to garment-manufacturing environments.

(2) We introduce a wrist-oriented keypoint extension strategy for HRNet, enabling accurate ergonomic scoring in tasks—such as sewing—where wrist deviation is a dominant contributor to WMSDs.

(3) We propose a task-specific pose-to-RULA fusion pipeline, forming the first end-to-end system tailored for garment manufacturing that maps 2D pose estimation to ergonomic risk levels derived from real workstation behaviors.

These contributions highlight that although the individual deep-learning modules are well-known, the novelty of this study lies in the task-driven integration and ergonomic applicability in real garment-production scenarios, which has not been previously explored.

In light of these challenges, this paper proposes the combined YOLO-SE-CBAM-HRNet model. By enhancing YOLO’s feature extraction capabilities, the model optimizes occlusion detection in complex garment manufacturing scenarios, while simultaneously leveraging HRNet’s high-resolution advantages to enable precise human joint localization. This approach addresses the subjectivity and inefficiency of traditional RULA-based ergonomic assessment methods, which rely on manual observation and scoring. It can also adapt to video information input from ordinary cameras, providing a practical WMSDs risk-assessment solution for the garment industry. Unlike prior generic pipelines, this study provides the first integration specifically designed for the visual and ergonomic characteristics of garment-production tasks. The model implements an end-to-end workflow covering video input, pose estimation, angle calculation, RULA scoring, and risk warning, and its effectiveness has been verified in real-world scenarios.

3. Methods

The core of our methods lies in improving the computer vision-based human pose estimation algorithm to enhance the accuracy of human pose estimation in complex scenarios, thereby enabling limited ergonomic risk assessment. This section will provide a detailed exposition of the proposed methodology for ergonomic risk assessment in sewing workshops, encompassing an integrated framework that combines object detection, human pose estimation, and ergonomic scoring. The pipeline comprises three core modules: the YOLO-SE-CBAM model for human detection, the HRNet model for keypoint localization, and the RULA method for ergonomic scoring. Each component has undergone rigorous validation using performance metrics. Every part has been thoroughly tested with performance measures. The next sections will explain each part in detail.

3.1. YOLO-SE-CBAM

In clothing workshops, busy backgrounds often cause problems. Stacked textiles and equipment can hide workers or be mistaken for people. This leads to missed detections or false alarms. The standard YOLOv8 model works fast but does not pay special attention to human shapes. It may miss people in crowded sewing areas.

In our work, we added SE and CBAM modules to YOLOv8. This created a new model called YOLO-SE-CBAM. The improved system now finds people more accurately in messy environments. It also handles background distractions much better.

3.1.1. YOLOv8 Architecture

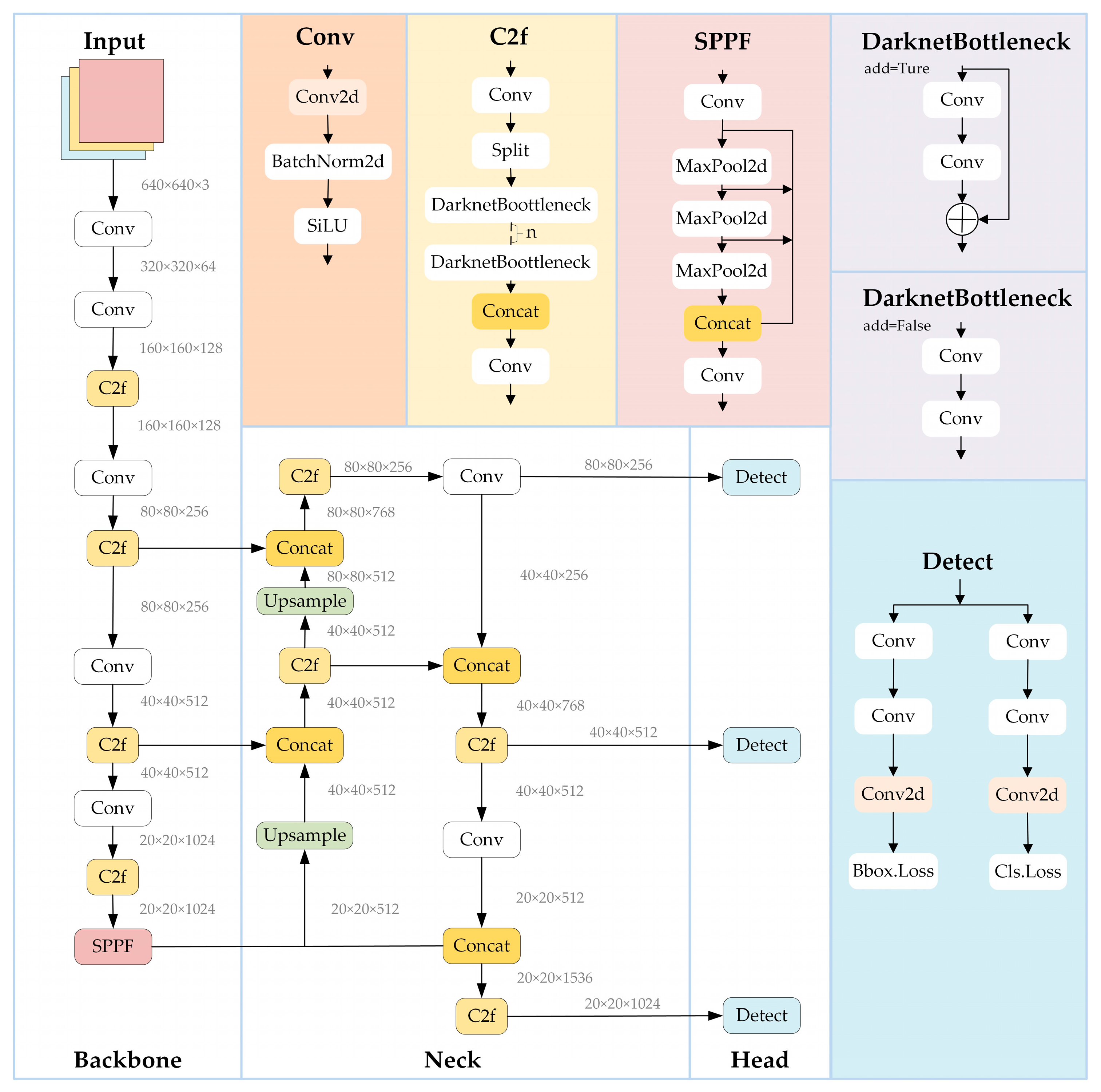

Figure 1 illustrates the YOLOv8 model. Its structure has three main parts: the Backbone, the Neck, and the Detection Head. The Backbone uses multiple layers with batch normalization and SiLU activation. This helps gradient flow better than the older ReLU function. A key improvement in YOLOv8 is the C2f module, which replaces the C3 module from YOLOv5. The C2f has more branches and skip connections. This gives richer feature details and better gradient flow, without needing much more computing power. It works especially well for spotting small objects. At the end of the Backbone, the SPPF module processes feature maps from different scales. It combines multi-level spatial information, which helps the model detect objects of various sizes. The Neck uses a PAN-FPN design. It mixes features from different Backbone layers. It samples features both top-down and bottom-up. Finally, it provides the Head with three separate feature maps made for objects of different sizes. The Head works without anchor boxes. It splits the job into two separate tasks: classifying objects and drawing bounding boxes. This separation reduces interference between the tasks and helps the model detect more accurately [

49]. We chose the YOLOv8s model because it is lightweight. The model receives images sized at 640 by 640 pixels. It only keeps detections identified as “person”. This provides clean, focused areas for the next step of pose estimation. It also helps reduce noise from unnecessary boxes when people are partly hidden.

The system locates the head area to obtain the body’s bounding box, called p_boxes. Each box follows the format [x1, y1, x2, y2]. Here, (x1, y1) marks the box’s top-left corner. The point (x2, y2) marks its bottom-right corner. This method lets us separate and standardize the image areas containing people. It ensures the next stage, which uses HRNet to find body keypoints, works on a stable and consistent input.

3.1.2. Attention Mechanisms

There are several common kinds of attention mechanisms. These include spatial attention, channel attention, and mixes of both. After studying our specific situation, we picked a solution that uses SE and CBAM modules. Using these two together helps us obtain the best outcome.

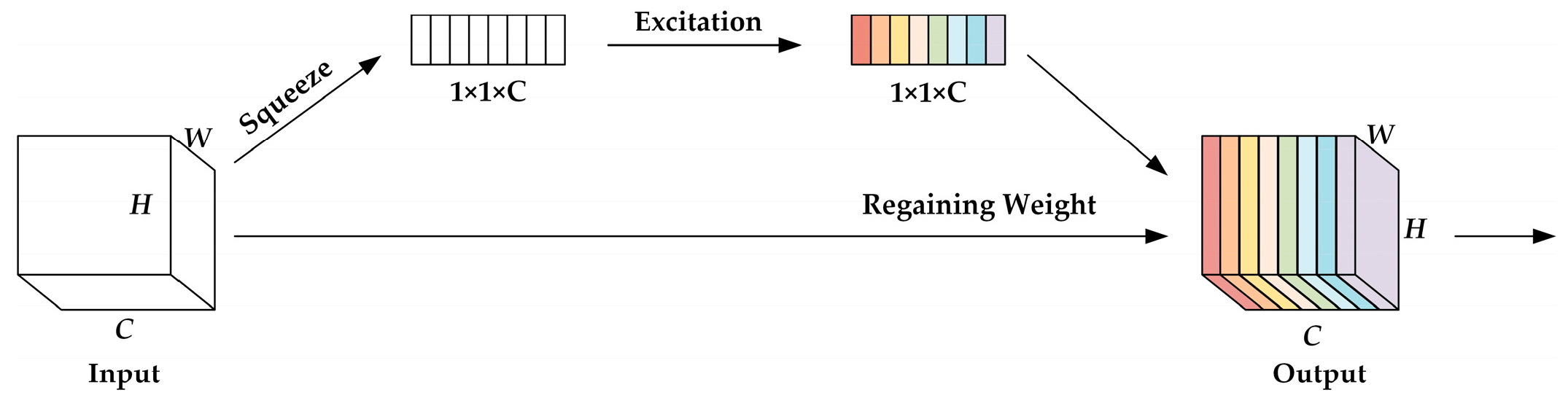

(1) SE: The Squeeze and Excitation (SE) module is a channel attention mechanism. It consists of two main parts: the Squeeze operation and the Excitation operation. This design allows the network to dynamically adjust the importance of different feature channels. At the same time, it suppresses features that are less useful for the task. The structure of the SE module is shown in

Figure 2. SE recalibrates only the channels, yet workers within the workshop occlude one another, necessitating explicit spatial emphasis on critical regions. Consequently, CBAM is introduced to concurrently model both channels and spatial relationships.

Following the structural description, the mathematical formulation of the SE module is summarized as follows.

Given an input feature map

, the Squeeze operation applies global average pooling to aggregate spatial information into a channel descriptor:

where

is the value at spatial location

in channel

;

denotes the number of channels;

and

represent the height and width of the feature map, respectively; and

is the aggregated descriptor for channel

.

The Excitation operation then uses a two-layer fully connected gating mechanism to generate channel-wise importance weights:

where

is the channel descriptor vector;

and

are learnable weight matrices;

denotes the ReLU activation;

denotes the Sigmoid function; and

represents the learned channel-wise importance weights.

Finally, the input feature map is rescaled through channel-wise multiplication:

where

is the learned importance weight for channel

and

denotes the recalibrated output feature map.

This formulation highlights that SE adaptively adjusts the response of each channel based on global contextual information, allowing the network to emphasize feature channels most relevant to human detection under occlusion-prone and visually complex workshop environments.

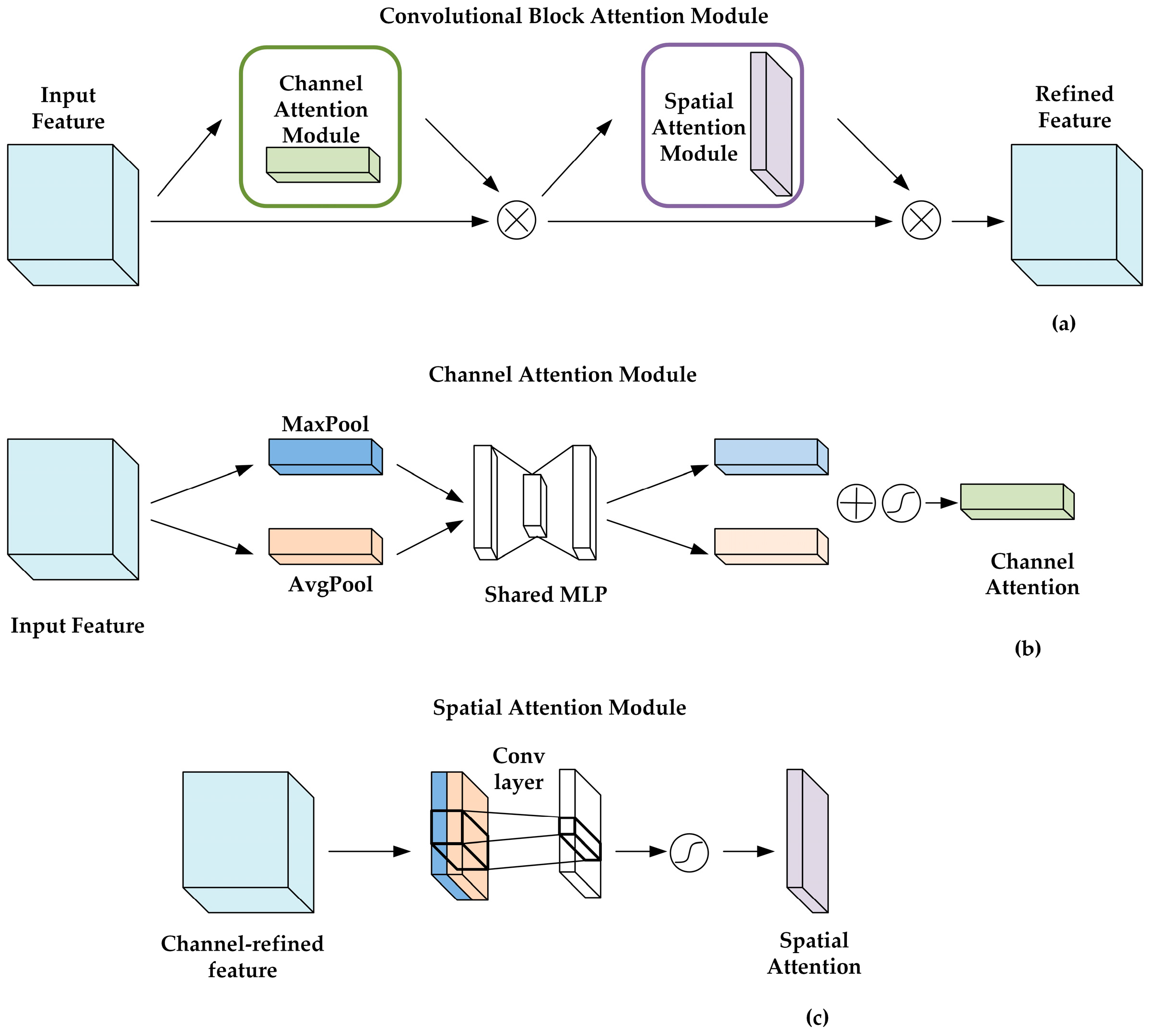

(2) CBAM: As shown in

Figure 3, the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) contains two parts that work in order. These are the Channel Attention Module (CAM) and the Spatial Attention Module (SAM). It helps the model choose and combine important features more flexibly. This improves how the model assigns importance during learning. It also becomes better at noticing small objects in images. The SE module has a limitation. It uses only average pooling, which can miss some important local details. The CAM module works differently. It uses both average pooling and max pooling together. Average pooling gathers overall information, while max pooling finds distinct features. They share the same MLP weights to learn about channels. Their outputs are added together to create a final channel attention map.

For an input feature map

, CAM first applies global average pooling and max pooling along the spatial dimensions:

Both descriptors are fed into a shared MLP, and their outputs are added to produce the channel attention map:

The recalibrated feature map is then obtained via channel-wise multiplication:

where

and

denote the average-pooled and max-pooled channel descriptors;

MLP denotes the shared fully connected layers;

is the Sigmoid function;

represents the channel attention weights;

denotes channel-wise multiplication.

The SAM module uses the spatial connections between features. It finds the most important areas in an image. First, it creates two 2D maps using average and max pooling across the channels. Then, it combines these maps into one spatial feature map. This map includes information from all channels. A 7 × 7 convolution layer processes it, and a Sigmoid function creates the final 2D spatial attention map.

Given the output of CAM,

, SAM computes two spatial descriptors by applying average pooling and max pooling across the channel dimension:

These two feature maps are concatenated:

and passed through a

convolution followed by a Sigmoid activation to obtain the spatial attention map:

The final refined feature map is obtained as follows:

where

and

represent spatial descriptors;

is a convolutional layer with a

kernel;

is Sigmoid;

is the spatial attention map;

is the final feature refined in both channel and spatial dimensions.

CBAM works in a serial manner. First, channel attention adjusts the feature map’s channels. Then, spatial attention adjusts its spatial areas. This process creates a feature map that is refined in both channel and spatial aspects. By combining CAM and SAM, CBAM makes the model understand images better. It strengthens key channel features and focuses on important spatial areas. This allows the model to capture a complete set of visual information.

3.1.3. The Overall Framework

This research built an object detection model called YOLO-SE-CBAM. The structure is shown in

Figure 4.

In the YOLOv8 framework, the SE and CBAM modules are inserted after the main convolutional layers to strengthen feature representation. While the backbone extracts semantic information progressively, SE recalibrates channel responses and CBAM refines both channel- and spatial-level attention, suppressing background noise and highlighting posture-relevant regions. This enhancement improves human detection robustness under common factory challenges such as occlusions, variable lighting, and cluttered scenes, while preserving the real-time efficiency required in industrial applications. These improvements provide a stronger feature basis for subsequent keypoint detection and ergonomic analysis.

3.2. HRNet with Keypoint Detection

HRNet analyzes human poses using images from YOLOv8. The input is prepared by first expanding the center of each detection box by 1.4 times. This box is then scaled to a fixed size of 288 × 384 pixels. This size is used for both training and running the HRNet model. The input images first pass through convolutional layers and max pooling to generate initial feature maps, forming the first high-resolution branch. Subsequently, low-resolution branches are added sequentially. The model becomes stronger at finding features by running multiple branches in parallel. Each branch looks at a different level of detail. During each branch extraction stage, the number of channels is adjusted through repeated stacked Bottleneck layers, maintaining the feature layer size to ensure high-resolution information remains uncompressed. Upon completing the initial high-resolution branch and channel adjustment, the network enters the branch expansion phase: it proceeds to the first Transition layer, which generates two new feature branches based on the current high-resolution feature map–one downsampled by a factor of 4 and another downsampled by a factor of 8. Subsequently, the network proceeds to the next round of Stage feature extraction. Upon completion, Transition2 directly takes the 8× downsampled feature map from the existing branches as input, generating a new 16× downsampled feature branch through a convolutional layer. At this point, the number of parallel branches within the network increases again, forming a richer, multi-scale structure comprising: ‘high-resolution branch + 4× downsampled branch + 8× downsampled branch + 16× downsampled branch’. At the feature processing grade, the high-resolution branch retains precise coordinate information for joint nodes, while low-resolution branches (such as the 16× subsampled branch) leverage larger receptive fields to capture broader human body part relationships. The network ultimately feeds the highest-resolution feature map into its output layer. Through 1 × 1 convolutions, feature channels are mapped onto heatmaps for key body points (e.g., shoulders, elbows, knees) with dimensions heatmap_width = 72, height = 96 (scaled proportionally to one-quarter of the input size). Each pixel value in the heatmap represents the probability that the corresponding position is the target keypoint. By decoding the coordinates of the maximum value location in the heatmap, the final predicted results for each human joint can be obtained [

50].

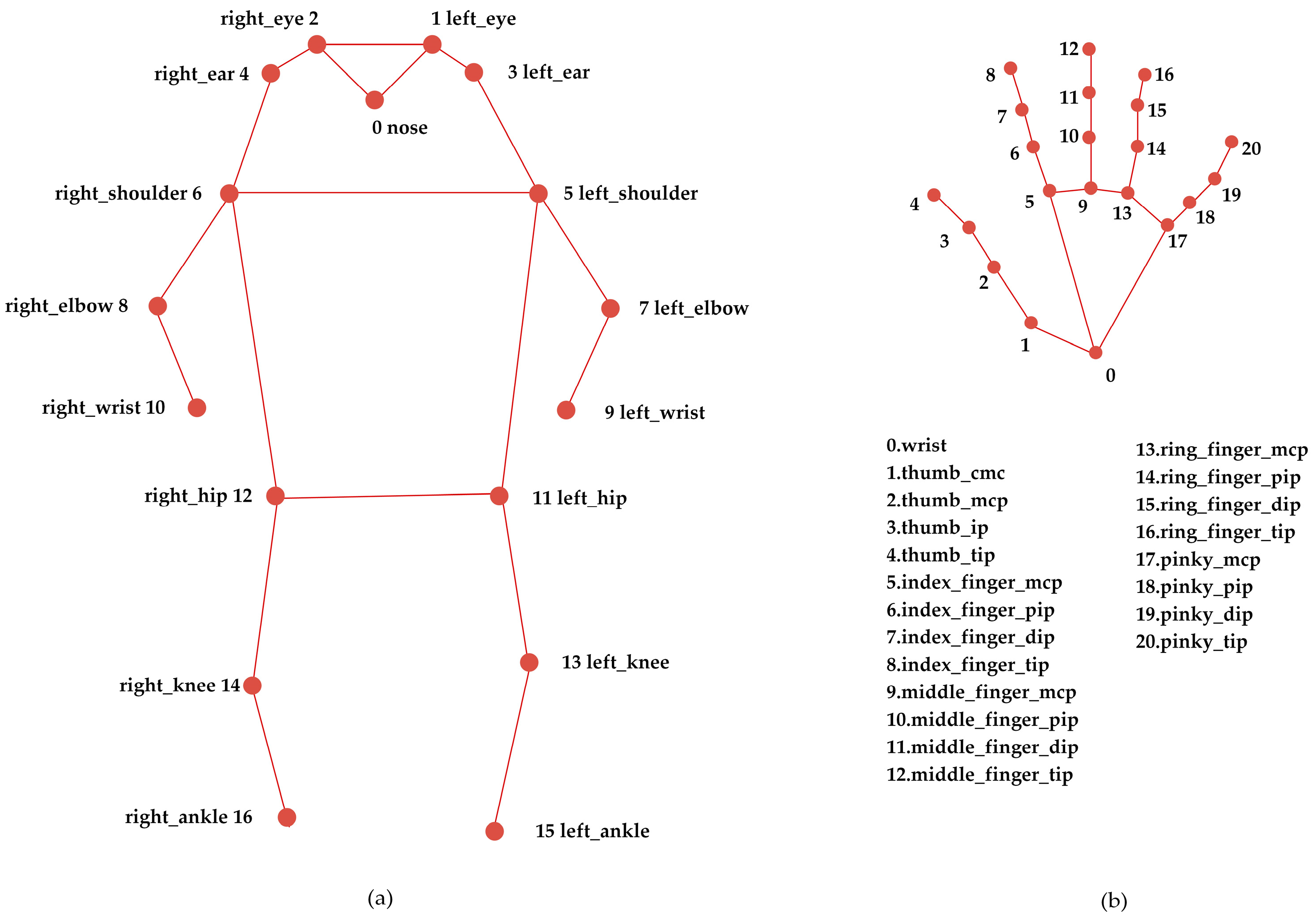

To ensure transparent and reproducible posture assessment, this study explicitly formulates the computation of joint angles required for RULA scoring. All angles

θ are obtained from COCO keypoint coordinates (

Figure 5), using the standard vector-based formulation:

where the dot product and Euclidean norms are computed directly from the COCO keypoint coordinates shown in

Figure 5. Based on this formulation, each RULA-related angle is derived from anatomically meaningful keypoint combinations as follows:

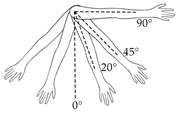

Upper-arm angle (): Derived from the shoulder–elbow vector (left arm: ; right arm: ) relative to the vertical reference axis.

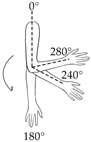

Lower-arm angle (): Derived from the elbow–wrist vector (left arm: ; right arm: ) relative to the corresponding upper-arm vector.

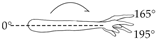

Wrist angle (): Computed from the wrist–hand-reference vector (left wrist: ; right wrist: ) relative to the lower-arm segment. The additional keypoint (middle-finger base) provides a stable reference for quantifying wrist deviation during sewing operations, where fine wrist rotations frequently occur.

Neck angle (): Computed from the vector connecting the averaged shoulder position to the upper-trunk region, relative to the vertical axis.

Trunk angle (): Computed using the vector from the averaged hip keypoint to the averaged shoulder keypoint referenced against the vertical direction.

All computed angles are then mapped to the corresponding posture categories and scoring rules defined in

Table 2 and

Table 3, ensuring full alignment with the original RULA assessment criteria and enabling transparent reproduction of the ergonomic evaluation pipeline.

To support more detailed analysis of wrist posture, an additional hand keypoint was incorporated into the pose-estimation process. This was achieved by extending the keypoint annotation scheme used during training and generating a corresponding heatmap using the same Gaussian-based encoding method applied to the original joints. In the network implementation, the adjustment was confined to the output layer responsible for heatmap prediction, ensuring that the backbone architecture and multi-resolution fusion mechanism of HRNet remained unchanged. During training, the newly added keypoint was optimized together with the existing ones under the same loss function, and during inference, its location was obtained through the standard heatmap-peak decoding procedure. This integration approach provides finer hand-related posture information while maintaining full compatibility with the original HRNet design.

Table 4 shows that compared to other models trained on the COCO dataset, HRNet-W48 achieves higher average precision values on the COCO test development set, falling only slightly below the RLE and TokenPose models. However, when considering overall performance, HRNet-W48 demonstrates greater advantages. RLE (Run-Length Encoding) is fundamentally a data compression algorithm. Within the domains of object detection and keypoint recognition, it is typically employed to encode output results, thereby reducing data transmission volume. When utilised as a model architecture or methodology to enhance AP values, its network structure lacks the intuitive and readily comprehensible mechanisms for feature extraction and keypoint localisation that HRNet possesses. TokenPose, whilst a novel approach based on the Transformer architecture with unique advantages in handling long-range dependencies, suffers from the Transformer’s inherently black-box nature. In industrial real-time monitoring scenarios, its lack of interpretability may hinder the rapid identification of model misclassification causes. Second, systems like RLE and TokenPose do not effectively address frequent challenges in textile manufacturing, such as fabric patterns or machines that block the view. This makes their joint detection less reliable than HRNet. In real-time monitoring, HRNet and YOLO-SE-CBAM function really well together. HRNet’s ability to mix several feature scales allows it to manage a variety of workshop situations consistently.

HRNet (W48) has been widely used as a strong baseline on COCO and MPII human pose-estimation benchmarks [

57], which supports its selection as a stable backbone for ergonomic angle computation. As shown in

Table 4, smaller HRNet variants led to reduce the keypoint-detection accuracy under partial occlusion, whereas the objective of this work is to verify the correctness of the detection–pose–scoring pipeline rather than to explore architectural variations within HRNet. Therefore, ablation analysis was focused on YOLO-based attention enhancements, where performance differences were expected to be more meaningful for the downstream ergonomic-scoring task.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, in order to measure the wrist angle for RULA scoring, this study adds a new keypoint. The method uses the 17 standard points from MS COCO 2017, plus one more: the middle finger’s base. This added 9th keypoint comes from the COCO Handpose dataset.

3.3. Rapid Upper Limb Assessment

The Rapid Upper Limb Assessment (RULA) is a method for assessing the risks associated with poor arm and neck posture at work. Lynn McAtamney and Nigel Corlet [

60] introduced it in 1993. The RULA approach evaluates the angles of the upper and lower arms, wrists, neck, and back. It first assigns a number to each body part depending on its position. The arm and wrist numbers are then combined to form Score A, followed by the neck and back values in Score B. To locate Score C, first check Score A in

Table 2 and Score B in

Table 3.

Then, add them together to reach a final number between one and seven. Score C defines action priority: 1–2 (low risk, ignore), 3–4 (medium, consider modifications), 5–6 (high, act soon), and 7 (extremely high, act now).

The experimental validation in this study was conducted as an initial feasibility assessment. A small set of representative static frames was extracted from longer operational videos to ensure that the selected images captured typical postures within cutting, sewing, and pressing tasks. These frames were annotated and evaluated by a focused expert group familiar with garment manufacturing ergonomics. The goal of this validation was not to provide full large-scale statistical generalization but rather to verify the functional correctness of the proposed detection–estimation–scoring pipeline under real workshop conditions.

3.4. Performance Metrics

This study uses several measures to check the detection performance of YOLO-SE-CBAM. This ensures the experiment results are correct. Commonly used evaluation metrics include Intersection over Union (

IoU), Precision, Recall, and map, calculated as follows:

TP denotes the number of correctly detected positive samples,

FP denotes the number of negative samples misclassified as positive, and

FN denotes the number of missed positive samples (i.e., those incorrectly classified as negative). The

AP value denotes the area under the P-R curve. In Formula (3), the

mAP value is obtained by calculating the average of all category APs, where N represents the total number of detected types. In this experiment, a higher mAP value indicates better detection performance and higher recognition accuracy of the algorithm.

denotes the area of the predicted frame, and Bb denotes the area of the ground truth frame. The

IoU ratio reflects the degree of overlap between predicted and ground truth frames. A higher

IoU value indicates greater prediction accuracy. The

mAP at

IoU threshold 0.5 (mAP@0.5) denotes the metric calculated using non-maximum suppression (NMS) with an IoU threshold ≥0.5 [

61].

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Video Capture and Ethics

This study conducted ergonomic risk assessments on three primary processes in the sewing manufacturing industry: fabric cutting, sewing, and pressing. Video capture involved 3 master craftsmen for fabric cutting, 7 for sewing, and 4 for pressing. Based on posture estimation, all research participants were able-bodied. Ethical protocols were strictly followed throughout this study: All participants were required to sign informed consent forms, where they were fully informed of this study’s purpose, data usage, and the measures implemented to ensure data confidentiality and personal privacy. Additionally, three ergonomics experts were recruited; their manual assessment results will serve as a benchmark to verify whether the proposed method can achieve performance comparable to or exceeding that of human evaluators.

4.2. Implementation Details

All the related code and algorithm run on the computer with Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU ES-2680 v3 (Santa Clara, CA, USA) and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Ti (Santa Clara, CA, USA) under Windows 10. The object detection training part used the MS COCO 2017 dataset, which contains about 118,287 training images from 80 object categories. The dataset is rich in human poses and a large number of images. We first split the whole dataset into a 90% training set and a validation set, as well as a 10% test set. Then, we further split the 90% training and validation set into a 90% training set and a 10% validation set. Finally, we obtain an 81% training set and 9% validation set as training data and a 10% test set as test data. The training part uses the VOC dataset format, and the labels are saved in XML format to keep the object coordinates and category information. All the grayscale images will be automatically converted into images with RGB channels to fit the model input format. The input image size is forced to be 640 × 640 (640 is a multiple of 32, which is the downsampling factor of YOLOv8). Mosaic augmentation is enabled. Mosaic enhancement will further enable mix-up enhancement with 50% probability enhancement. This strategy is used in the first 70% of epochs to train to make a balance between data diversity and fidelity to the true distribution.

The training strategy adopts a phased optimization strategy: In the freezing phase, the pretrained backbone network outputs basic features, which alleviate the feature learning instability caused by the initial parameter random initialization. While a larger batch size accelerates the training speed, 50 iterations are trained in each epoch, with 32 samples input to the model loaded into the memory in each iteration. In the unfrozen phase, the backbone network tunes to human detection and fine-tunes all parameters to improve the accuracy of human target recognition. In the unfrozen phase, the backbone network is trained for 300 epochs with a batch size of 16. This design not only reduces the occupation of GPU memory during full parameter training but also increases the number of parameters that can be updated each time, providing more flexibility. We adopt SGD as the optimizer, the initial learning rate of which is set to 1 × 10−2. The minimum learning rate is set as 1% of the initial learning rate. The momentum is set as 0.937, and the weight decay is set as 5 × 10−4. The cosine annealing strategy is adopted in the learning rate decay strategy to make the adjustment gentler. In order to ensure the reliability of the training process and the ability to trace the results, this experiment adopts an evaluation strategy to save weight files in the 10th epoch. The mean Average Precision (mAP) is adopted as the evaluation index, which plays a key role in dynamically monitoring the training convergence and avoiding overfitting. In this study, mAP refers specifically to mAP@0.5 (AP50), following the COCO-style IoU threshold of 0.5 for object detection evaluation. To ensure experimental repeatability and efficiency, the parameter initialization module and the random augmentation module were configured with the fixed random seed (seed = 11). At the same time, the multi-threaded data loading (num_workers = 4) is enabled to parallelize loading and preprocessing the data, so as to improve the training efficiency.

To evaluate the practical deployability of the proposed pipeline, we additionally measured the runtime performance of both the detection and pose-estimation components under the same hardware configuration. The inference speed was computed using the full YOLO–HRNet pipeline, and the resulting FPS values are reported in

Table 5 together with parameters and FLOPs. These measurements provide a clearer assessment of real-time feasibility on representative industrial hardware.

4.3. Results on the COCO Dataset

An ablation study was conducted on YOLOv8-SE-CBAM, with the results shown in

Table 5 and

Figure 6. In addition to accuracy metrics,

Table 5 also reports the number of parameters, FLOPs, and inference time of each model variant. All FPS values reported in

Table 5 were measured on the same hardware configuration described in

Section 4.2 (Intel Xeon E5-2680 v3 CPU and NVIDIA RTX 4060 Ti GPU). These results provide a comprehensive view of the computational cost associated with SE and CBAM, enabling a clearer assessment of the accuracy–efficiency trade-off for real-time deployment.

As demonstrated by the precision-recall (PR) curve in

Figure 6, the original YOLOv8 model exhibits a precision approaching 1.0 at low recall grades, indicating high accuracy for predictions with strong confidence. However, with the increase in recall, precision rapidly decreases to about 0.1 in the high recall region (recall > 0.8). Namely, when more objects are detected, there are more false positives. For YOLOv8-SE, compared with YOLOv8, its precision is better than YOLOv8 in the medium-to-high recall range (recall > 0.6). For example, when recall = 0.8, its precision is much higher than YOLO’s.

Compared with YOLOv8, YOLOv8-CBAM is more accurate in the whole recall range. When the recall is low, the accuracy of YOLOv8-CBAM is similar to YOLOv8; when the recall is medium (for example, recall = 0.5) or high (for example, recall = 0.8), the accuracy of YOLOv8-CBAM is higher. Because Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) combines channel attention and spatial attention, it can focus more accurately on features and decrease more false positives when more objects are detected.

YOLOv8-SE-CBAM obtains the best performance in all models. When the recall is low, its accuracy is close to 1.0; when the recall = 0.6, its accuracy is close to 0.9; when the recall is high, its accuracy is much higher than the other three models. The highest F1-score achieved by the YOLOv8-SE-CBAM model, which integrates both SE and CBAM attention mechanisms, signifies its superior capability in balancing detection precision and recall under challenging industrial environments. YOLOv8-SE-CBAM outperforms all other models. The combined SE and CBAM attention mechanisms enhance its feature selection, allowing it to handle occlusions and complex postures effectively. SE attention mechanism and CBAM attention mechanism enhance the feature selection and focusing ability of the model, and YOLOv8-SE-CBAM is most effective at balancing recall and accuracy.

As shown in

Table 5, introducing SE or CBAM into the YOLOv8 baseline results in only a marginal increase in parameters (from 9.831 M to 9.832 M) and no change in FLOPs (23.4 G), confirming that both modules are lightweight additions. Despite this minimal computational overhead, both attention mechanisms noticeably improve inference speed. Specifically, YOLOv8-SE achieves the highest FPS (87.36), demonstrating that SE’s channel-wise recalibration enhances feature selectivity without imposing extra latency. CBAM, which includes both channel and spatial attention, slightly increases computational complexity but still delivers a high runtime performance of 82.53 FPS. When SE and CBAM are combined, the resulting model reaches 82.84 FPS—maintaining real-time capability while achieving the highest accuracy (AP = 83.09%). Here, AP refers to AP@0.5 (IoU = 0.5) to ensure consistency in performance evaluation across all model variants.

From

Table 6 and

Figure 7, we compared our proposed YOLOv8-SE-CBAM model with other object detection models. Precision of YOLOv8-SE-CBAM is 91.13%, recall is 66.08%, F1 score is 77.0%, and AP is 83.09%. Even though the recall is slightly lower, the accuracy is improved a lot compared with EFF-YOLO [

62], which obtains 77.8% accuracy and 67.2% recall. It outperforms all YOLOv5s variants [

63]—including YOLOv5 (73.82% accuracy, 67.05% F1), YOLOv5-SE (72.64% accuracy, 64.99% F1), YOLOv5-CBAM (70.66% accuracy, 65.04% F1), and YOLOv5-STP (74.92% accuracy, 67.9% F1)—across all metrics. It also has higher accuracy than the advanced YOLOv5 model [

64] that reached 79% AP. These results confirm that integrating SE and CBAM into YOLOv8 strengthens discriminative feature extraction, improving accuracy, recall, F1 score, and AP in object detection tasks.

With SE and CBAM attention modules enhancing its feature extraction capability, YOLO-SE-CBAM enables high-precision human detection in complex workshop environments that involve equipment occlusion, lighting variations, and worker overlap. Its 91.13% precision effectively filters out interfering objects (e.g., machinery, materials), providing clean human regions of interest (ROIs) for subsequent pose analysis. HRNet, leveraging its full-path high-resolution feature representation architecture, accurately extracts key human keypoints (e.g., neck, shoulders, elbows, hips) and calculates joint angles for common worker postures. This fully meets RULA’s accuracy requirements for quantifying angles of critical body regions. YOLO-SE-CBAM-HRNET supports rapid deployment. It needs no additional training data annotation for specific workshop scenarios or task types, and only depends on the general-purpose COCO human detection pre-trained model.

4.4. Algorithm Performance and Visualization

To qualitatively demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed YOLO-SE-CBAM-HRNet model in real garment production environments,

Figure 8 presents the pose estimation results on workers during the three primary processes.

The output images confirm that our method reliably identifies joint locations and reconstructs body positions. It accurately estimates the right-side postures frequently adopted by operators during production. This performance remains consistent despite typical factory obstructions like fabric piles in sewing or machinery blocking the view during pressing. These findings verify the approach’s practical effectiveness in real workshop environments, establishing a trustworthy basis for follow-up ergonomic evaluation.

Beyond qualitative visualization, the end-to-end runtime of the complete YOLO–SE-CBAM–HRNet–RULA pipeline was also evaluated under continuous video input. On the hardware platform described in

Section 4.2 (Intel Xeon E5-2680 v3 CPU and RTX 4060 Ti GPU), the system processed 640 × 640 input frames at approximately 35.3 FPS, including person detection, region-of-interest cropping, multi-scale pose estimation, and RULA angle computation. This frame rate satisfies the real-time requirement for workshop-level monitoring (typically ≥ 30 FPS) and indicates that the full detection–pose–scoring workflow can operate stably during garment production tasks.

4.5. Establishment of Expert Standards and Comparison with RULA Algorithm Scoring

This study extracted 10 static single-frame images with non-repetitive postures from each of the cutting, sewing, and pressing processes. A fixed panel of three experts was invited to score these 30 samples. A multidimensional metric system was established to distinguish between inter-expert consistency (benchmark validation) and algorithm-expert consistency (model performance):

Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) measure numerical consistency. For inter-expert reliability, ICC(3,1) bidirectional mixed-effects models (suitable for fixed expert groups and random samples) were employed; ICC(A,1) assessed consistency between algorithm scores and expert average scores. ICC emphasizes numerical consistency, with values >0.85 indicating high agreement.

Cohen’s Kappa focuses on categorical agreement (risk grades 1–4), independent of numerical bias and sensitive to category mismatches (e.g., misclassifying grade 2 as grade 3). A Kappa value above 0.8 shows excellent agreement in the ratings.

We use Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and 95% Limits of Agreement (95% LoA) to measure the scoring differences. MAE tells us the average size of the errors. The 95% LoA shows the range where most errors fall. A smaller range means the agreement is more consistent.

Table 7 shows the ICC for ScoreA by three experts is 0.951, which denotes the experts have nearly perfect consistency in scoring. While the ICC for ScoreB is 0.89, and Cronbach’s Alpha is 0.959. The ICC result of ScoreB is lower than that of ScoreA. It means the consistency of numerical judgments by experts for ScoreB is slightly worse than that of ScoreA. Experts had different evaluations on the trunk angle. Some experts scored samples more than 180° as 4, while the rest scored samples rotated slightly less than 180° as 2. However, Cronbach’s Alpha shows the same scoring criteria (no bias, only a slight difference in numerical value) for all experts. Reliability coefficients based on overall scoring were above 0.85, which also suggested that three experts had high consistency in their ratings and thus the experts’ mean score could be used as the standard for comparing with our system’s mean score.

Table 7 presents the scores by three experts and our method. Cohen’s kappa co-efficient was used to further investigate the consistency of classification. All three scoring groups had high numerical consistency, with only a slight difference between Score A, Score B, and Score C. However, in terms of classification consistency and bias stability, there were some differences among them. The ICC between the system and three experts for Score A was 0.917, which means the system and experts had high numerical agreement. However, the Cohen’s kappa coefficient of Score A was 0.808, while those of Score B and Score C were higher than that of Score A. It means that the classification accuracy of Score A was slightly lower than that of Score B and Score C. Score A achieved a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.808, while Score B reached 0.849, which was higher than 0.808. This advantage stems not from smaller fluctuations in the B score (2 or 4 points), but from fewer classification mismatches between the system and expert assessments. For example, in trunk angle evaluations, although system scores may differ from expert scores by 2 or 4 points, such mismatches occur less frequently. In contrast, Score A exhibited more frequent classification mismatches. A typical case occurs when a worker’s hand is facing the camera with the back of the hand visible: the system’s classification of “wrist” more frequently deviates from the category assigned by experts, as shown in

Figure 9. Additionally, score fluctuations across grades 1, 2, and 3 for Score A involved more instances where the system and experts assigned different grades, ultimately leading to a lower kappa coefficient.

Score C achieved an ICC of 0.93 and a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.831, indicating high grades of both numerical and categorical consistency between the system and experts. Regarding mean absolute error (MAE) and 95% limits of agreement (95% LoA), MAE followed the gradient: Group C (0.1556) < Group A (0.2222) < Group B (0.3111). The 95% LoA results revealed that Group C had the most concentrated deviation distribution, while Group B had the most dispersed. This confirms that for Group C scores, the algorithm exhibits the smallest average deviation from the expert average and more stable consistency, while Group B shows the highest variability in the evaluation results. In summary, the methodology proposed in this study demonstrates high reliability and stability, specifically for Score C. It accurately reflects the ergonomic risk grades of different processes for garment workers, thereby providing an effective tool for WMSDs risk assessment in sewing workshops.

Although the numerical and categorical agreements were generally high, the misclassifications exhibited a characteristic distribution across the three production processes. In cutting, most discrepancies arose from borderline trunk flexion angles, where rapid forward bending during material handling led to occasional score shifts between adjacent RULA categories. In sewing, misclassifications were primarily associated with fine wrist posture variations, which are more difficult for the algorithm to detect due to frequent occlusions caused by fabric, sewing tools, and hand–material interactions. In pressing, errors were mostly related to rapid upper-arm elevation during repetitive lifting motions, causing transient deviations in upper-limb angle estimation. Importantly, these misclassifications were generally small in magnitude—typically within one RULA level—and did not alter the overall risk classification for most samples. This distribution shows that the model performs robustly across all processes while being more sensitive to subtle or transient postural changes.

To further verify that the RULA angle computation is supported by sufficiently accurate pose information, we additionally evaluated the HRNet-W48 keypoint detector on the COCO keypoint validation split. The assessment followed the official OKS-based metric, where the Object Keypoint Similarity (OKS) measures keypoint accuracy by comparing predicted locations with ground truth while accounting for person scale and keypoint visibility. Under this protocol, HRNet-W48 achieved an OKS-AP of 74.9%, which is aligned with the commonly reported performance of this architecture. This level of keypoint localization accuracy indicates that major joints—including shoulders, elbows, hips, and wrists—are detected with sufficient precision to support stable downstream angle estimation. The inclusion of this supplementary analysis enhances the credibility of the ergonomic scoring outcomes presented in

Table 7.

5. Comprehensive Analysis of Garment Manufacturing Processes

We extracted representative process videos (30 FPS) from recorded cutting, sewing, and pressing operations for ergonomic analysis:

As shown in

Figure 10a, during the cutting process, when the workers used the electric cutter to trim the fabric, the comparison of the variation in risk grades based on the distance between the fabric and the body as follows: When the fabric is close to the body, the fluctuation in ScoreA value is caused by the small change in arm postures when moving the machine, but the whole risk grade is not changed, still in Grade 3. When the fabric is farther from the worker, the angle between the worker’s torso and the vertical direction is always less than 160° (minimum 121.8°), and the arm is always straight and raised up, so the range of motion is greatly increased. During this process, when the angle of the upper arm increases, the score changes from Grade 3 to Grade 4. At the same time, when the score of the torso angle reaches Grade 4, the whole risk grade is Grade 4.

As shown in

Figure 10b, during the pressing process, we captured the worker’s (how to fold and flatten the collar); when the worker lifted the pressing material, the angle of her upper arm was 63.1°. From 120 to 360 frames, the worker laid the pressing material on the collar; from 360 to 600 frames, the worker did the picking up the iron and repeatedly pressing the collar operation–at this time, the angle of her upper arm is sometimes 15.4°, sometimes 51.7°, fluctuating due to the back-and-forth movement of the arm. At this time, scoreA was 2–3 points, and the risk grade was evaluated as 3. After the ironed collars are produced, when workers place the collars, the angle of their upper arms becomes larger and their torso bends forward, so the risk grade becomes Grade 4.

As shown in

Figure 11, during the sewing stage, a female worker picked fabric, sewed seams, and finished garments. Score A fluctuated between 2 and 4 points with high frequency (range 2–4, grade 3), because the worker had to make small adjustments with the arms and wrists (grade 2–3). In the range of video frames 0–750, shown in

Figure 11. ScoreB showed large amplitude and high frequency fluctuation between 3 and 6 points. This was because the worker had to pick and place materials and prepare fabric before sewing. When worker picked and placed materials, their torso would tilt forward and backward to make their lumbar comfortable, causing a large fluctuation in risk grade. Later, in video frames 1530–1620, the worker placed the sewn garment beside her body, resulting in large fluctuations in arm abduction. The angle between the upper and fore arm increased, while the grade of the risk of torso and neck did not change, which added up to a risk grade of 5.

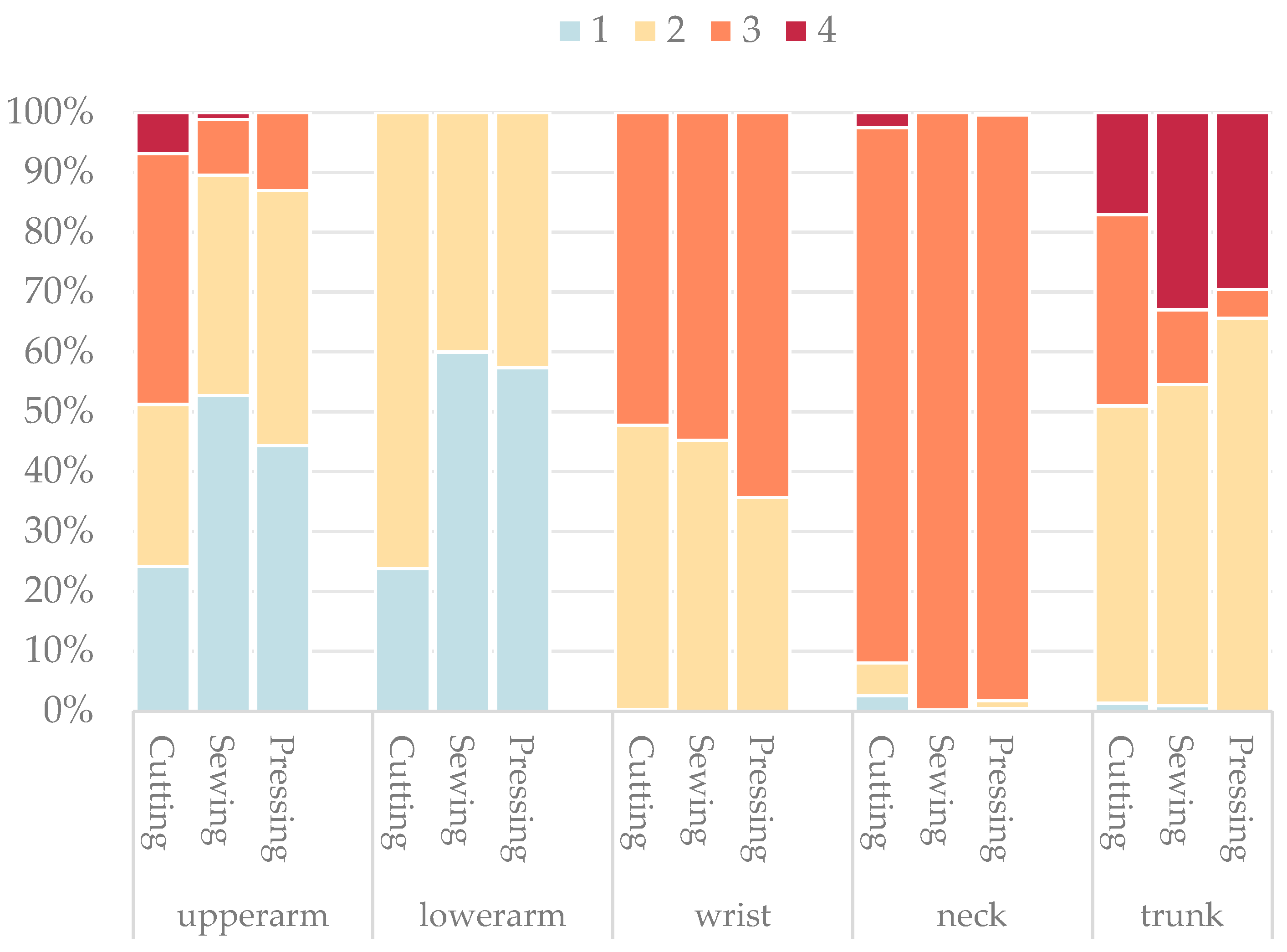

After scoring selected video samples, the risk grade distribution across different processes and body parts was analyzed, as shown in

Figure 12. Risk grades were coded as 1–4 based on the assessment scores, with key findings detailed below:

In the cutting process, the proportion of Grade 3 and Grade 4 risk postures of the upper arm is 41.30% and 6.19% and the sum of the two grades is nearly 47.5%. This shows that the upper arm would deviate from the angle range of the natural relaxed angle of 15° while operating a cutting machine. The arm is in a state of least muscle and joint effort, and the deviation finally leads to a high proportion of medium-to-high risk postures. In the forearm, Grade 2 risk postures take over 76.24% and there are no Grade 3 and Grade 4 risks. The proportion of the above three grades appears because the forearm should coordinate with the upper arm to make wide-range dynamic angle adjustment to move the fabric closer to or further from the cutting machine or control the machine to make cutting. The adjustment of upper limb postures leads to a slight deviation of the forearm from the optimal posture, but the deviation is not so serious that it leads to Grade 3 or above risk. In the case of torso, Grade 3 and Grade 4 risk postures take 31.97% and 17.06% and the sum of the two grades is nearly 50%. This is because the workers should lean forward to assist force application of the upper limb during cutting. The leaning posture of the torso pulls it away from the natural posture. The spine is in a state of least stress when it is in the physiological curvature state that is vertical to the ground. The deviation leads to a high proportion of medium-to-high risk.

In the sewing operation, grade 1 risk postures of the upper arm take 82.35%. Because of the precision requirement of upper limb postures in sewing work, the upper arm angle is usually maintained in a low-risk angle range, and the proportion of Grade 1 risk is relatively high. The proportion of Grade 1 and Grade 2 risk postures of the forearm is 60% and 40.8%, respectively. The proportion of the two grades is relatively balanced. This is because the forearm should be swung repetitively to feed fabric, and high precision angular requirement is needed for the angular control of the forearm to ensure the smooth sewing. The repetitive action leads to the deviation of the forearm from the optimal posture, but the deviation is not serious enough to cause the consequence of Grade 3 risk or above. In the case of trunk, Grade 4 risk posture takes 32.99%. This is because the workers should lean backward more than 180° to alleviate the back pain during the break from sewing work. The excessive extension posture of the torso leads to tremendous stress on the torso and leads to a high proportion of high risk load. Meanwhile, the long duration of fabric feeding leads to the deviation of the torso from the optimal posture, and the posture makes the worker lean forward. The proportion of Grade 2 risk is 53.64%.

The total percentage of Grade 1 upper arm movements in the process of pressing was 44.35% and the total percentage of Grade 2 upper arm movements was 42.61%. The total percentage of both grades exceeded 87%, which means that the arm swing was small, and the posture was rather relaxed and stable during the work, so the risk was low. The proportion of Grade 3 wrist movements was 42.61%, which means that the angles of the twisting the wrist were relatively high, and the repetitive movement during pressing was also considerable, which often causes hand and wrist pain. In addition, the fact that the head was in a downward position for a long time to observe the pressing area also means that the vast majority of necks were grade 3. In the examined body region, the proportion of Grade 4 risk was 29.57% and the proportion of Grade 2 risk was 65.65%. The repetitive movement of leaning forward to press and then moving to an upright position was the cause of the torso region risks.

In all three processes, the risk grades of wrist injuries were mainly Grade 2 and Grade 3. This is because, during cutting, sewing, and ironing, the wrist is forced out of its natural state, relaxed position. While cutting, workers have to hold the cutting machine; while sewing, small angle adjustments are required during the sewing process; while ironing, the iron must be operated. The difficulty of the wrist to be in a neutral angular position in all three processes is the area where the risks are concentrated. The most common risk for the neck was Grade 3, and the proportion of Grade 1 and Grade 2 was less than 3%. This is because the neck must be bent downward continuously to observe the details of the process while working.

Garment manufacturing workers are required to perform repetitive work in the forearm, torso, and wrist, which makes them more susceptible to WMSDs, chronic muscle strain, tendonitis, and degenerative diseases of the cervical and lumbar spine. Further ergonomic interventions can be carried out to reduce the occurrence of high-risk postures. For example, reasonable workstation layout and standardized postural training can be used to solve problems such as excessive trunk forward bending and excessive upper arm flexion [

65].

6. Discussion

6.1. Technical Advantages

The YOLO-SE-CBAM-HRNet method shows clear strengths in assessing worker movements during clothing assembly. Sewing tasks often include handling multiple fabric layers, blocked views from machinery, and small, detailed hand motions. Common detection and posture analysis tools struggle to identify important body points due to limited feature capture. The SE part adjusts channel weights to emphasize key posture features. CBAM then pinpoints critical zones such as hands and arms in both channel and spatial views. Together, they reduce noise from hidden sections and boost the precision of locating people. Tests indicate that adding SE and CBAM increases mAP by 4.43% and recall by 5.99% over a basic model without these attention parts. This enhancement significantly improves the representational quality of human-related features, leading to more precise and reliable keypoint localization. HRNet keeps high-definition feature maps during the entire process. It also combines different scale data to add fine details. This approach fixes the problem of fuzzy keypoint positions seen in older networks that use heavy downsampling. As a result, it supports the later steps of calculating joint angles for RULA ratings.

6.2. Research Limitations

This research uses 2D pictures to detect key body points. However, real body positions exist in three-dimensional space. Flat images often make mistakes in judging depth because of camera angles. For instance, during fabric cutting, an arm that moved 30 degrees sideways looks only a little bent when seen from the side. The system then gives a low score of 1–2 points, even though the actual angle is large. In pressing work, both 30° forward bending and 30° sideways leaning look similar in 2D images. This similarity can cause wrong-angle judgments by the system. The absence of depth cues introduces structural ambiguity and limits the accuracy of posture assessment. Future studies should include 3D posture analysis to make assessments more correct.

Adding a reference point at the middle finger’s root helps measure wrist angles better. But when workers face their palms toward the camera during sewing, key points like the wrist and finger base may be located inaccurately. The system could mistake this hand position for bent postures, giving 2–3 points. Human experts can tell from the work type and hand motions that the wrist is actually relaxed. They would assign 1–2 points. The computer calculates body angles very precisely using hip and shoulder points from HRNet. For example, it measures 185.2° exactly. Following the rules gives 4 points when the torso leans back over 180°. But humans rely on visual estimation. They cannot easily see differences between 180 and 185°. They often rate a slight 185.2° backward lean as normal posture, giving 1–2 points. This scoring difference comes from two approaches: exact computer measurement versus human visual judgment.

In addition to the factors discussed above, discrepancies between human assessments and algorithmic angle estimation are also influenced by differences in evaluation philosophy. Ergonomists tend to make holistic judgments that consider task type, body movement patterns, and work context, whereas the 2D estimation module evaluates posture strictly based on geometric relationships. This often leads to small but systematic deviations. To reduce such inconsistencies in real deployment, the system adopts a simple calibration procedure that standardizes camera placement, working distance, and viewing angle, helping to minimize bias introduced by perspective distortion. Moreover, ergonomic scoring methods such as RULA inherently incorporate tolerance margins for joint angles, meaning that slight numerical differences rarely change the final risk category. As a result, even when human and algorithmic measurements diverge by a few degrees, the practical impact on risk-level assignment remains limited. These considerations suggest that the system can operate reliably in real manufacturing environments as long as basic calibration is maintained and posture scoring is interpreted within the appropriate tolerance range.

Moreover, the present study did not include comparisons with recent pose-estimation models such as RTMPose, ViTPose, DWPose, or other MMPose pipelines. These models typically rely on transformer-based architectures or multi-stage tracking mechanisms that incur higher computational cost and are less suited for lightweight edge-device deployment, which is a primary consideration for workshop-level ergonomic monitoring. Benchmarking against these models will be performed in future work to further strengthen the generalizability of the proposed framework.

Although real-time inference was achieved on the tested hardware, the experiments were conducted on pre-recorded videos, meaning that camera vibration, worker turnover, rapid hand motions, dense object interactions, and strong illumination changes were not systematically stress-tested. In addition, power consumption, long-duration thermal stability, and frame-rate robustness—which are critical for edge-device deployment—were not examined. These aspects will be addressed in future work through extended real-time experiments in continuously operating workshop environments.

6.3. Outlook

The existing data only records basic routine operations across three processes: cutting, sewing, and pressing (e.g., straight cutting with a cutting machine, flat sewing with a sewing machine, and back-and-forth pressing with an iron). It does not include extreme movements within the workflow that are prone to high risks, such as bending down to the ground to pick up stacked fabrics (trunk forward tilt angle ≤ 110°), standing on tiptoes to reach high material shelves (upper arm elevation angle ≥ 120°), or kneeling on one knee to arrange fabrics on the floor (coordinated twisting of lower limbs and torso). Although these actions occur relatively infrequently, each instance imposes substantially higher biomechanical loads than routine tasks. Such peak-load movements are well-recognized contributors to work-related musculoskeletal disorders and require considerable physical effort, which accelerates fatigue and reduces operational efficiency [

66]. Their omission creates blind spots in the algorithm’s assessment of peak risks. The full garment manufacturing process encompasses a complete chain, including cutting-sewing-pressing-packaging-handling. Current research only covers the first three core processes, excluding equally high-risk operations such as packaging (e.g., folding garments, boxing, and bagging) and handling (e.g., transferring fabric bundles, finished product boxes).

The current dataset was collected under semi-controlled workshop conditions that included moderate background clutter and partial occlusion but did not fully capture the most congested or heavily obstructed environments found in some garment-production settings. Future work will expand the dataset to include scenes from more challenging real-world conditions, such as densely packed workstations, severe occlusions caused by machinery and stacked textiles, diverse lighting environments, and variations in worker clothing and fabric types. In addition, multi-angle video capture from different production lines will be incorporated to ensure broader coverage of operational contexts. These expanded data sources will support further refinement of the detection and pose-estimation modules, enhancing their robustness and generalizability in highly cluttered factory environments.

Existing research has not conducted an in-depth analysis on the material heterogeneity and process variability in garment manufacturing: On one hand, it fails to consider the impact of fabric material (e.g., heavy denim/light silk/stretch knits) and size (e.g., large-scale fabric sheets/small-scale cut pieces) on work posture and load. For instance, cutting heavy denim requires greater upper arm force and causes more significant wrist angle deviation, yet existing algorithms rely solely on posture angle scores without adjusting risk grades based on material properties. On the other hand, distinctions within the same process for specialized tasks (e.g., flat seaming, overlocking, and bar tacking in sewing) were not made. Different specialized tasks involve distinct equipment operation methods and posture emphases (e.g., bar tacking requires frequent fabric rotation and increased trunk twisting). Future research should use data from these situations to better understand muscle and skeleton injuries in clothing production.

7. Conclusions

This study aims to solve the problems of low efficiency and strong subjectivity in manual ergonomic evaluation of garment manufacturing workers. This study uses the YOLO-SE-CBAM-HRNet algorithm to realize automatic ergonomic evaluation of three basic garment manufacturing processes: cutting, sewing, and pressing. Through computer vision technology, it automatically extracts the key postural features (such as upper arm angle, wrist angle, and torso angle) of workers in garment manufacturing processes from worker operation videos and evaluates the ergonomic level of garment manufacturing workers quantitatively based on these features. Furthermore, the reliability of the YOLO-SE-CBAM-HRNet–based evaluation was examined by benchmarking its RULA-derived scores against expert assessments. To validate the algorithm, RULA scores generated by the system were compared against expert assessments. The results demonstrate strong consistency and stability between the algorithm and human experts, confirming its ability to accurately track dynamic ergonomic risks across different processes. It should be noted, however, that the present validation was conducted as a pilot study with a limited number of workers and a restricted set of task scenarios. Consequently, the results should be interpreted as demonstrating initial feasibility rather than full-scale generalizability across the entire garment manufacturing industry. Expanding participant diversity and process variability will be necessary in future work to ensure broader applicability. This study also identifies major ergonomic risk factors in garment production through analysis of the three key processes. These findings support the use of computer vision as a reliable, intelligent tool for ergonomic monitoring in the garment industry.

This study identifies critical ergonomic risk factors inherent in garment production: tasks such as cutting and material handling lead to pronounced trunk forward bending and upper arm flexion, while sewing involves sustained non-neutral wrist postures and prolonged trunk flexion. Pressing tasks further impose repetitive upper-limb loading and sustained trunk flexion, which are known contributors to cumulative musculoskeletal strain. These findings highlight the upper arms, wrists, and torso as the most vulnerable body regions, underpinning the risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders such as muscle strain, tendonitis, and spinal degeneration.

Overall, this study significantly advances the existing knowledge base in ergonomic risk management for the garment manufacturing sector. It not only deepens understanding of the specific ergonomic risk factors inherent in core garment production processes but also provides a feasible and reliable intelligent assessment tool for industrial applications [

67]. The findings offer data-driven decision support for workplace redesign. This includes optimizing workbench height, rearranging equipment, and adding assistive tools to boost safety and efficiency. The YOLO-SE-CBAM-HRNet algorithm can also be used in other apparel production processes. The resulting data can provide broader support for the intelligent transformation of ergonomic management in the garment manufacturing industry.