Color-Based Laser Engraving of Heritage Textile Motifs on Wood

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

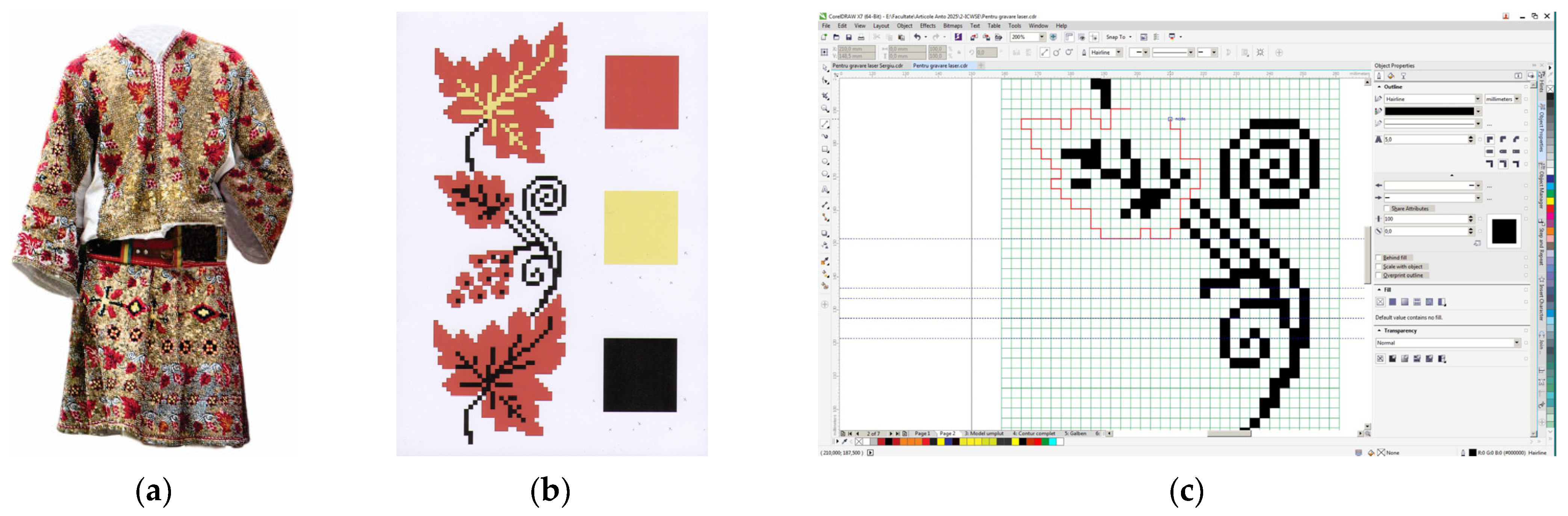

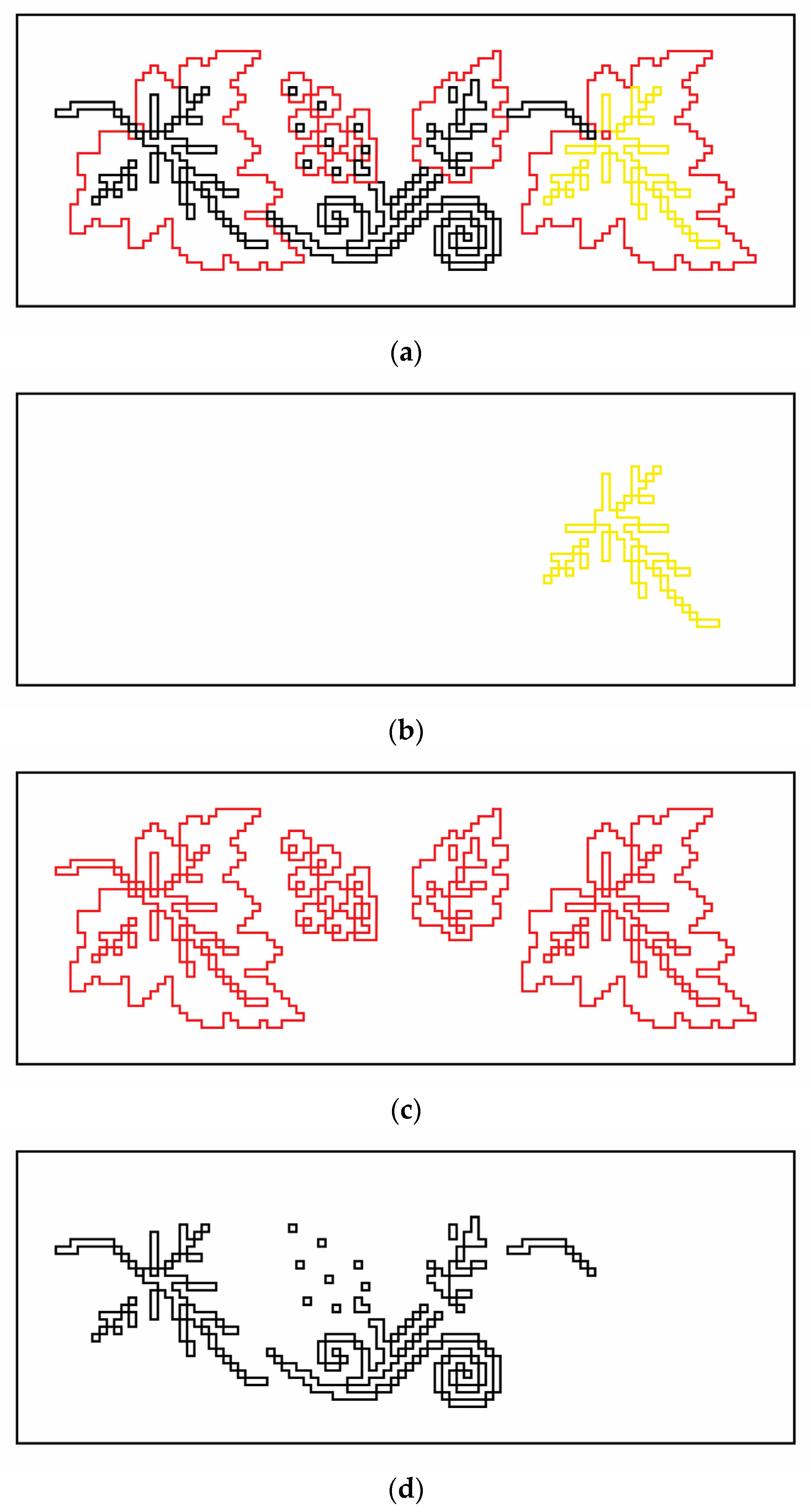

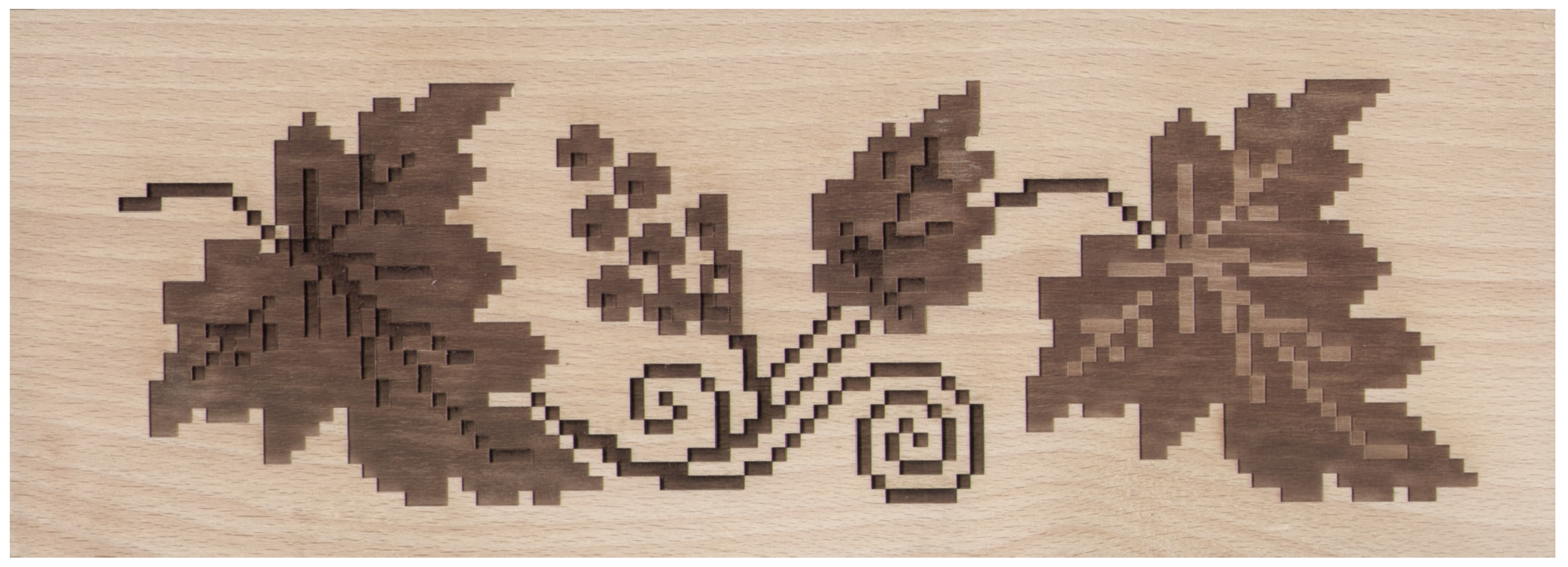

2.1. Textile Traditional Motif

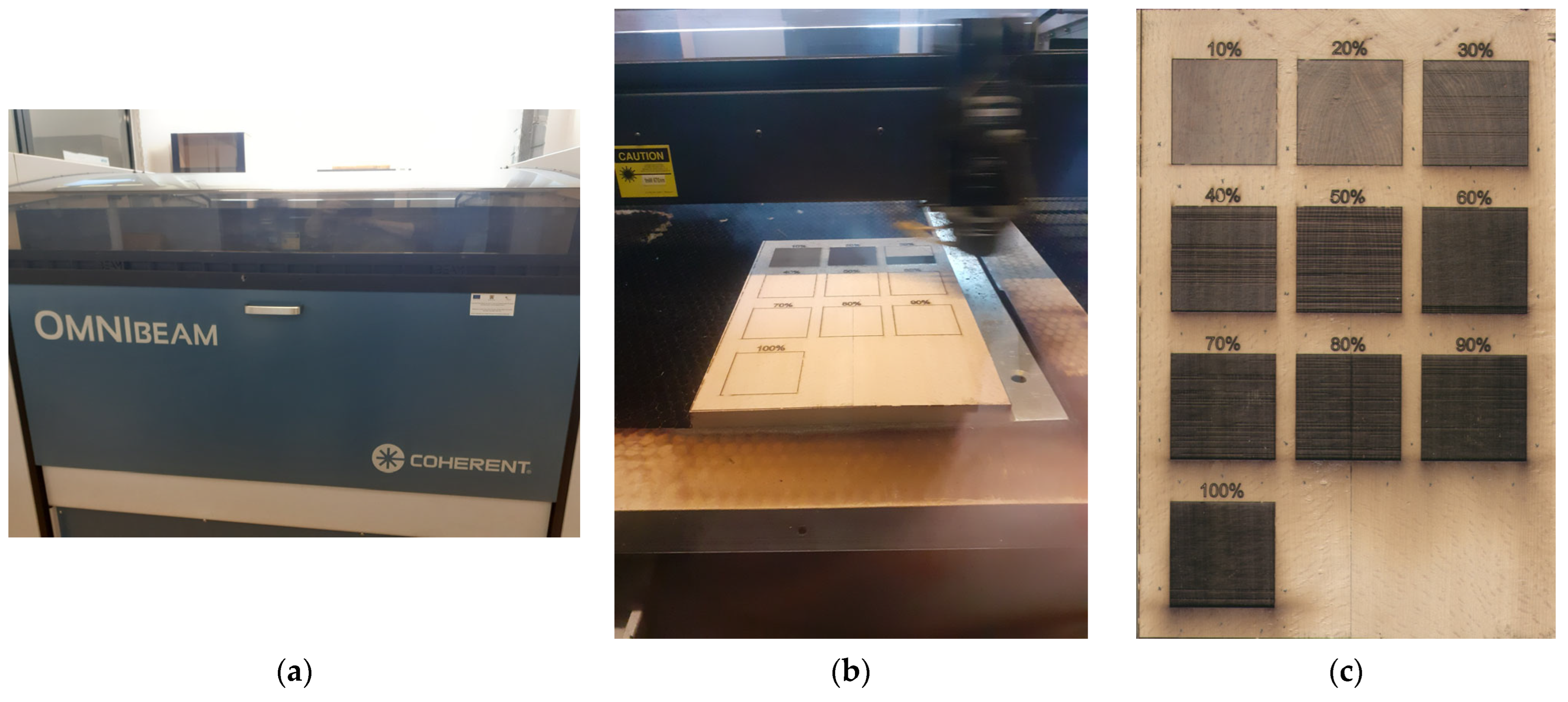

2.2. Equipment and Material

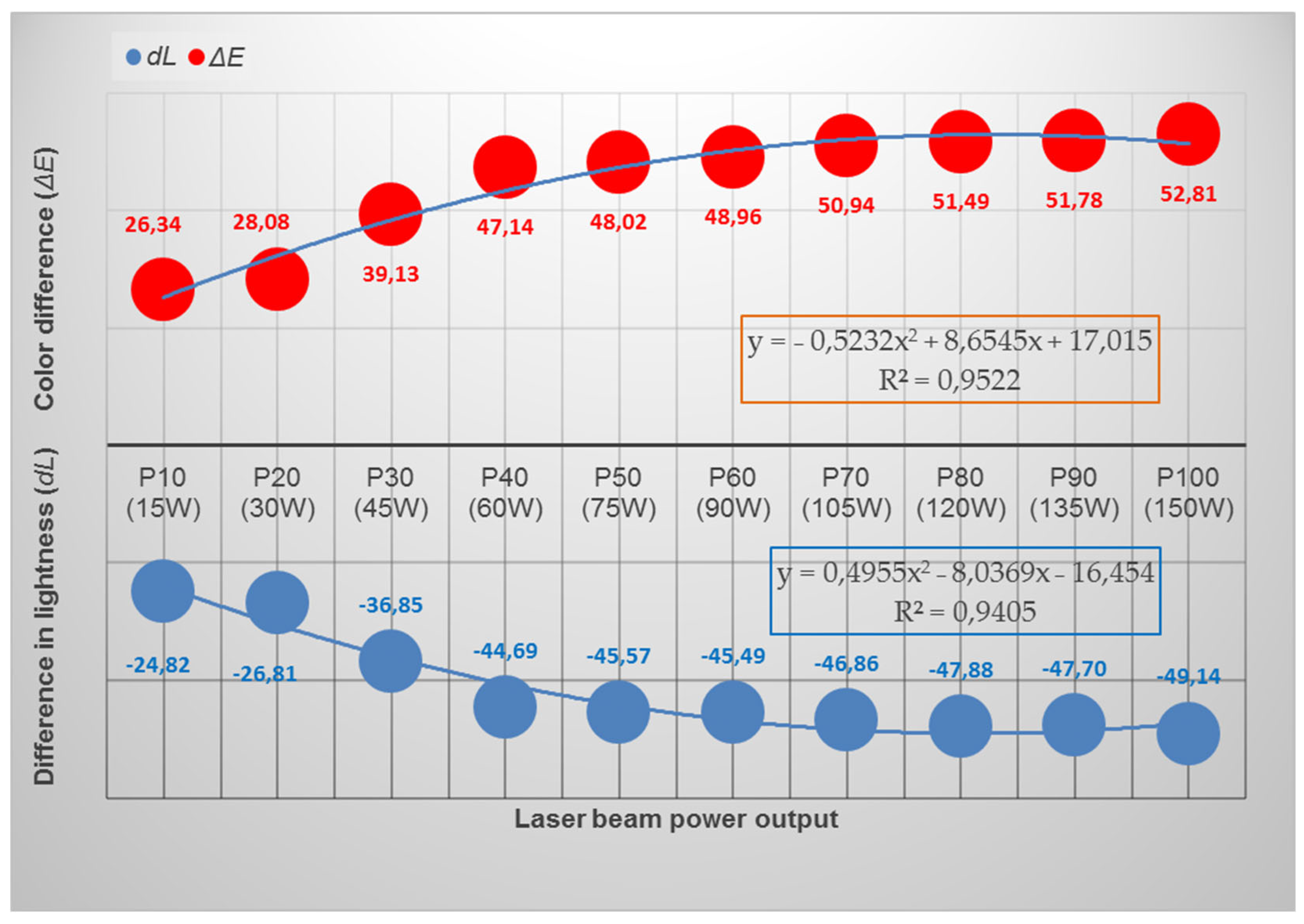

2.3. Testing Method

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| a | Red-green coordinate |

| b | Yellow-blue coordinate |

| Bk | Black |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CIELab | International Commission on Illumination system |

| L | Lightness |

| Ye | Yellow |

| ΔE | Color difference |

References

- Beschastnov, N.P.; Rybaulina, I.V.; Dembitskaya, A.S. From popular arts to decorative and applied arts of the folklore direction: Modern experience and ways of development. Vestn. Slavianskikh Kul’tur 2020, 55, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silah, S.; Basaree, R.O.; Isa, B.; Redzuan, R.S. Tradition and Transformation: The Structure of Malay Woodcarving Motifs in Craft Education. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 90, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffee, N.; Said, I. Types of Floral Motifs and Patterns of Malay Woodcarving in Kelantan and Terengganu. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, H.; Sabil, A.; Hanapi, A. Typology of Woodcarving Motifs in Johor Traditional Malay Houses. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2023, 14, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, G.; Cimatti, B.; Melosi, F. A Proposal for the Evaluation of Craftsmanship in Industry. Procedia CIRP 2016, 40, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu-Ming, M.; He-min, D.; Hao, Y. On innovative design of traditional Chinese patterns based on aesthetic experience to product features space mapping. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2023, 10, 2286732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisnawati, E.; Sunarni, N.; Indrayani, L.M.; Sofyan, A.N.; Nur, T. Identity Exhibition in Batik Motifs of Ebeg and Pataruman. Sage Open 2019, 9, 2158244019846686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaja, D.S.E.; Wibirama, S.; Herliansyah, M.K.; Sudiarso, A. Comparative study of integral image and normalized cross-correlation methods for defect detection on Batik klowong fabric. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J. Application of dunhuang decorative tile elements in children’s furniture based on symbolic duality and D4S Theory. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, O.; Cuciuc Romanescu, L. An Analogical Approach to Colors and Symbolism in Romanian and Turkish Folk Art. Art-Sanat. 2021, 15, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariseftia, E.; Azzahra, A.; Ciptandi, F. Analysis of Traditional Elements in Traditional Woven Fabrics Using the ATUMICS Method: Case Study: Sidan Woven Fabric by the Endo Segadok Weaving Group in Menua Sadap Village. J. Indones. Sos. Sains 2025, 6, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieș, D.; Indrie, L.; Caciora, T.; Herman, G.; Huniadi, A.; Șandor, M.-I.; Albu, A.; Costea, M.; Moș, C.; Safarov, B.; et al. Heritage textiles: An integrated approach for assessment and future conservation. Ind. Textilă 2022, 73, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumadewi, P.; Wening, S. Study of the Art and Culture of Hinggi and Lau Motifs in the Traditional Ceremonies of the East Sumba Community. J. Vis. Art Des. 2023, 15, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, A.; Caciora, T.; Berdenov, Z.; Ilies, D.; Sturzu, B.; Sopota, D.; Herman, G.; Ilies, A.; Kecse, G.; Ghergheleş, C. Digitalization of garment in the context of circular economy. Ind. Textilă 2021, 72, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, A.; Androne, A.; Gurau, L.; Racasan, S.; Cosereanu, C. Textile heritage motifs to decorative furniture surfaces. Transpose process and analysis. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 52, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Wang, R. Research on Multi-Feature Fusion Shadow Puppet Motifs Generation Based on CSPMotifsGAN and Cultural Heritage Preservation. Comput. Animat. Virtual Worlds 2025, 36, e70047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Wang, J. Design optimization of wood-carved window grilles in historical architectures using stable diffusion model and intuitionistic Fuzzy VIKOR. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Marziana Mohammad Noh, L.; Abd Razak, H. Application of the Chinese Dunhuang Algae Well Pattern in Contemporary Architecture Design: A Review Paper. Malays. J. Soc. Space 2024, 20, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, X. From Ancient Traditions to Contemporary Design Influences Digital Archeology: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Tibetan Pattern Studies. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2024, 24, 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Barboutis, I.; Kamperidou, V.; Economidis, G. Handcrafted Reproduction of a 17th Century Bema Door Supported by 3D Digitization and CNC Machining. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawono, B.; Yuniarto, T.; Sanusi, C.E.P.; Felasari, S.; Widyanarka, O.K.W.; Anggoro, P.W. Optimization of virtual design and machining time of the mold master ceramic jewelry products with Indonesian batik motifs. Front. Mech. Eng. 2024, 9, 1276063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroviciu, I.; Teodorescu, I.C.; Vasilca, S.; Albu, F. Transition from Natural to Early Synthetic Dyes in the Romanian Traditional Shirts Decoration. Heritage 2023, 6, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Jamali, S.S.B. The application of ancient Chinese ornamentation in modern furniture design. Herança 2025, 8, 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Rakhim, D.; Vermol, V.V.; Legino, R. Designing Movable Kitchen Cart through the Elements of Traditional Baba Nyonya House. Environ. Behav. Proc. J. 2021, 6, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Abdul Rahman, A.R.; Gill, S.S.; Raja Ahmad Effendi, R.A.A. Furniture design based on cultural orientation: A thematic review. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2025, 12, 2442811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurau, L.; Petru, A.; Varodi, A.; Timar, M.C. The Influence of CO2 Laser Beam Power Output and Scanning Speed on Surface Roughness and Colour Changes of Beech (Fagus sylvatica). BioResources 2017, 12, 7395–7412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidholdová, Z.; Reinprecht, L.; Igaz, R. The Impact of Laser Surface Modification of Beech Wood on its Color and Occurrence of Molds. Bioresources 2017, 12, 4177–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Açik, C. Modeling of Color Design on Furniture Surfaces with CNC Laser Modification. Drv. Ind. 2023, 74, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakimovich, B.; Chernykh, M.; Stepanova, A.I.; Siklienka, M. Influence of selected laser parameters on quality of images engraved on the wood. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen 2016, 58, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gochev, Z.; Vitchev, P. Colour Modifications in Plywood by Different Modes of CO2 Laser Engraving. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen 2022, 64, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernykh, M.; Korepanova, A.; Maksimova, E.; Sevryugin, V.; Gilfanov, M.; Štollmann, V. Selecting Color of Mosaic Pattern Elements for Laser Engraving on Wood. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen 2024, 66, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, M.; Muhammad, A.; Yusof, S.N.A.; Awang, R.; Mat Rasul, R.; Mohamad, W.; Izamshah, R.; Ginting, A. Determining optimal laser engraving conditions for high-contrast and well-defined engraving on Kapur wood (Dryobalanops) using ImageJ. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 141, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Açık, C.; Tutuş, A. Investigation of the effect of laser modification on some wood color characteristics. J. Fac. Eng. Archit. Gazi Univ. 2024, 39, 1973–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Xue, Z.; Wang, X.; Song, K.; Wan, X. A Color Reproduction Method for Exploring the Laser-Induced Color Gamut on Stainless Steel Surfaces Based on a Genetic Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.; Lopes, A.; Miranda, G. Ceramics Surface Design by Laser Texturing: A Review on Structures and Functionalities. ” Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 12, e00302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewski, P.; Sykutera, D.; Rojewski, M. The Impact of Selected Laser-Marking Parameters and Surface Conditions on White Polypropylene Moldings. Polymers 2022, 14, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.N.; Das, A.K.; Billah, M.M.; Rahman, K.-S.; Hiziroglu, S.; Hattori, N.; Agar, D.A.; Rudolfsson, M. Multifaceted Laser Applications for Wood—A Review from Properties Analysis to Advanced Products Manufacturing. Lasers Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 10, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, A.; Timar, M.C.; Beldean, E.C.; Georgescu, S.V.; Coşereanu, C. Adding Value to Maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) Wood Furniture Surfaces by Different Methods of Transposing Motifs from Textile Heritage. Coatings 2022, 12, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurek, M.; Wagnerová, R.; Šafář, M.; Bidhar, S. Crafting pixels in wood: Understanding the interplay of technologies and visual perception in wooden photo engraving. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2025, 83, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurek, M.; Wagnerová, R. Laser beam calibration for wood surface colour treatment. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2021, 79, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kúdela, J.; Kubovský, I.; Andrejko, M. Discolouration and Chemical Changes of Beech Wood After CO2 Laser Engraving. Forests 2024, 15, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisei, L. Ornamentation of Traditional Textiles from the Republic of Moldova. Ph.D. Thesis, Academy of Sciences of Moldova, Institute of Cultural Heritage, Center of Ethnology, Chișinău, Moldova, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Measured Items | Investigated Area | Average L* | Average a* | Average b* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser engraved squares on beech wood | Blank (untreated wood) | 68.67 (1.11) 2 | 12.03 (0.51) | 21.08 (0.54) |

| Square 10% (P10) 1 | 43.84 (2.81) | 11.60 (0.81) | 12.27 (0.92) | |

| Square 20% (P20) | 41.86 (0.91) | 10.92 (0.89) | 12.79 (0.93) | |

| Square 30% (P30) | 31.82 (2.25) | 9.26 (0.43) | 8.22 (0.77) | |

| Square 40% (P40) | 23.98 (1.55) | 5.88 (0.75) | 7.40 (1.25) | |

| Square 50% (P50) | 23.10 (1.16) | 7.30 (1.15) | 6.71 (3.98) | |

| Square 60% (P60) | 23.18 (0.75) | 6.09 (1.22) | 3.96 (2.67) | |

| Square 70% (P70) | 21.80 (0.21) | 5.83 (0.69) | 2.09 (1.50) | |

| Square 80% (P80) | 20.79 (0.71) | 5.46 (1.45) | 3.32 (1.90) | |

| Square 90% (P90) | 20.96 (1.98) | 5.18 (1.60) | 2.13 (3.63) | |

| Square 100% (P100) | 19.53 (0.89) | 4.30 (1.79) | 3.35 (2.67) | |

| Traditional motif on cardboard | Blank (White) | 93.93 (2.03) | 4.03 (0.16) | −10.01 (0.29) |

| Yellow | 87.07 (3.29) | −12.04 (1.12) | 73.24 (3.40) | |

| Red | 47.72 (0.71) | 55.57 (1.32) | 19.90 (2.23) | |

| Black | 30.93 (0.17) | 0.61 (0.27) | −1.96 (0.68) |

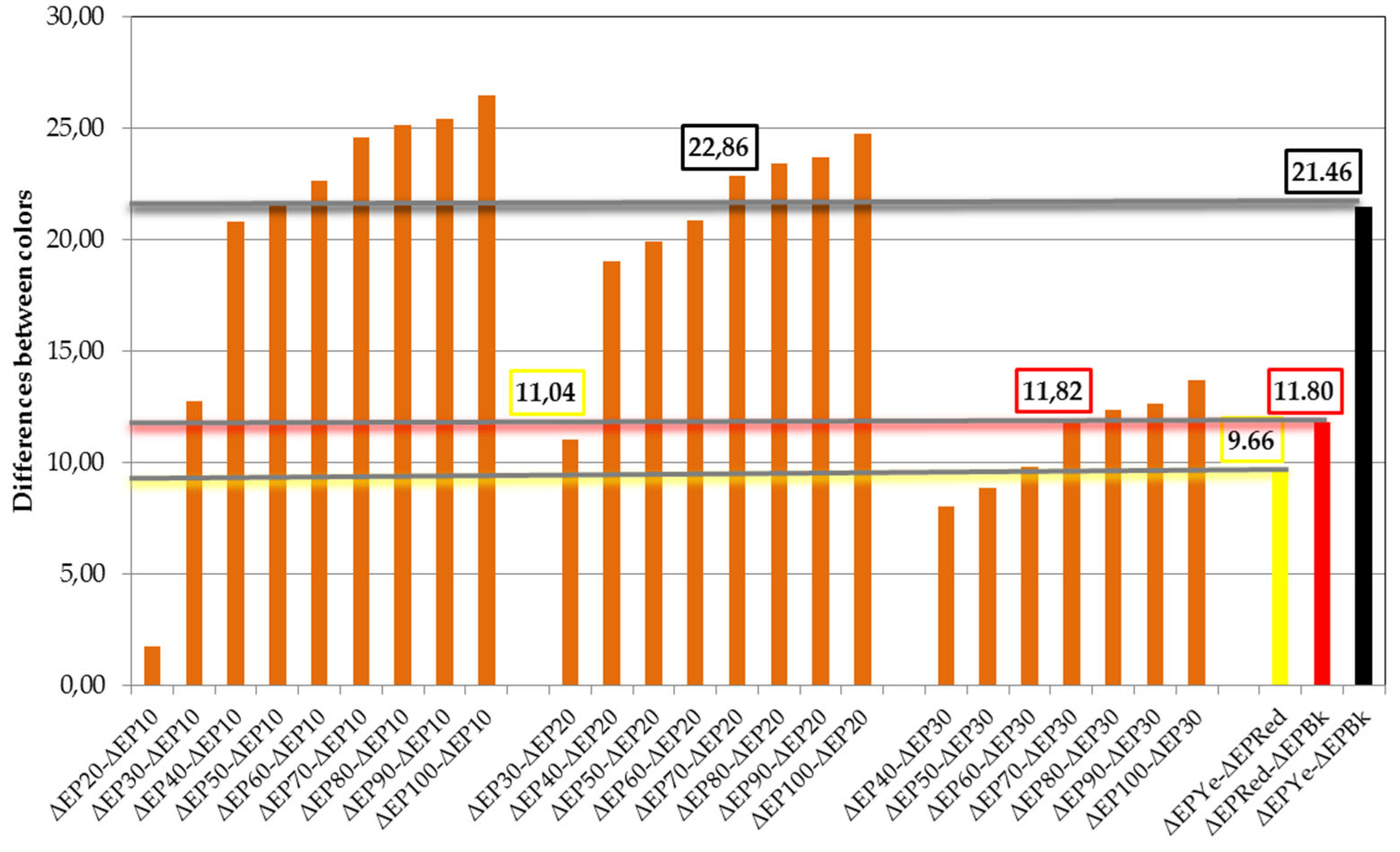

| Color Investigation | Investigated Color | ΔEPn 1 | Difference ΔEPn-ΔEP10 (n ≥ 20) | Difference ΔEPn-ΔEP20 (n ≥ 30) | Difference ΔEPn-ΔEP30 (n ≥ 40) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser engraved squares | Square 10% (P10) | 26.34 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Square 20% (P20) | 28.08 | 1.74 | 0 | 0 | |

| Square 30% (P30) | 39.13 | 12.78 | 11.04 | 0 | |

| Square 40% (P40) | 47.14 | 20.80 | 19.06 | 8.01 | |

| Square 50% (P50) | 48.02 | 21.67 | 19.93 | 8.89 | |

| Square 60% (P60) | 48.96 | 22.62 | 20.88 | 9.84 | |

| Square 70% (P70) | 50.94 | 24.60 | 22.86 | 11.82 | |

| Square 80% (P80) | 51.49 | 25.15 | 23.41 | 12.36 | |

| Square 90% (P90) | 51.78 | 25.44 | 23.70 | 12.66 | |

| Square 100% (P100) | 52.81 | 26.47 | 24.73 | 13.68 | |

| Color Investigation | Investigated Color | ΔEcolor 2 | Difference ΔE(Yellow-Red) | Difference ΔE(Red-Black) | Difference ΔE(Yellow-Black) |

| Traditional motif | Yellow | 85.07 | 9.66 | 0 | 0 |

| Red | 75.41 | 0 | 11.80 | 0 | |

| Black | 63.60 | 0 | 0 | 21.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lungu, A.; Georgescu, S.V.; Cosereanu, C. Color-Based Laser Engraving of Heritage Textile Motifs on Wood. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12900. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412900

Lungu A, Georgescu SV, Cosereanu C. Color-Based Laser Engraving of Heritage Textile Motifs on Wood. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12900. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412900

Chicago/Turabian StyleLungu, Antonela, Sergiu Valeriu Georgescu, and Camelia Cosereanu. 2025. "Color-Based Laser Engraving of Heritage Textile Motifs on Wood" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12900. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412900

APA StyleLungu, A., Georgescu, S. V., & Cosereanu, C. (2025). Color-Based Laser Engraving of Heritage Textile Motifs on Wood. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12900. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412900