3.2. Compressive Strength

When mixed with water, OPC reacted with water to produce calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, the primary binding component, and calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)

2). Due to its ultrafine particle size, SF acted as a micro-filler in the early stages, packing tightly between the larger cement grains. This accelerated the cement hydration by providing additional nucleation sites for C-S-H gel formation. SF also exhibited high pozzolanic activity in the mixes, positively affecting the compressive strength. The amorphous silica (SiO

2) present in SF reacted with Ca(OH)

2 generated during cement hydration through a pozzolanic reaction, forming additional C-S-H. This secondary C-S-H formation enhanced the microstructure and overall strength of the hardened concrete [

54]. Both SF and FA were pozzolanic materials; thus, they reacted with the Ca(OH)

2 released by the OPC hydration. These reactions consumed the weak and water-soluble Ca(OH)

2 and converted it into an additional, stronger C-S-H gel. This continued throughout the long-term curing process. Because of its higher reactivity and much finer particle size, SF’s pozzolanic reaction was faster and more significant in the early stages, while FA’s reaction was slower and provided more long-term strength. GGBFS, on the other hand, was a latent hydraulic material and a pozzolanic material. Its reactions occurred more slowly than those of cement [

55,

56], and also produced a C-(A)-S-H gel that mainly contributed to the improvement of the concrete’s later-age strength.

When combined in the mixtures, these materials did not act independently; instead, they enhanced each other’s performance. SF contributed to early strength through its micro-filling effect and rapid pozzolanic reaction. Over the long term, slower-reacting materials like GGBFS and FA continued to form secondary binding gels, resulting in higher ultimate strength than the concrete produced solely from OPC. However, when the OPC content was too low, the Ca(OH)2 produced was not sufficient to induce the pozzolanic reactions, leading to a higher amount of unhydrated particles and consequently, a reduction in compressive strength.

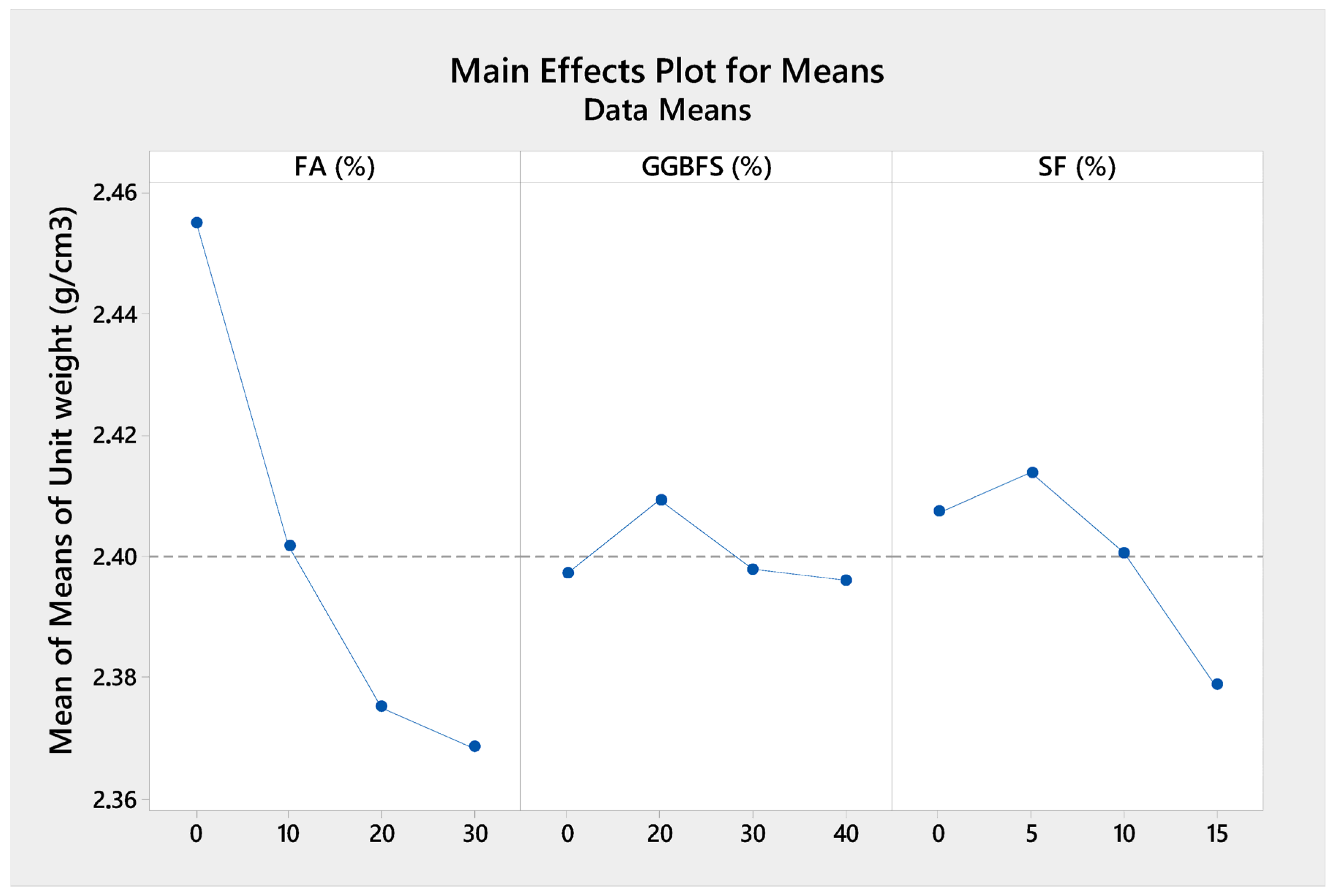

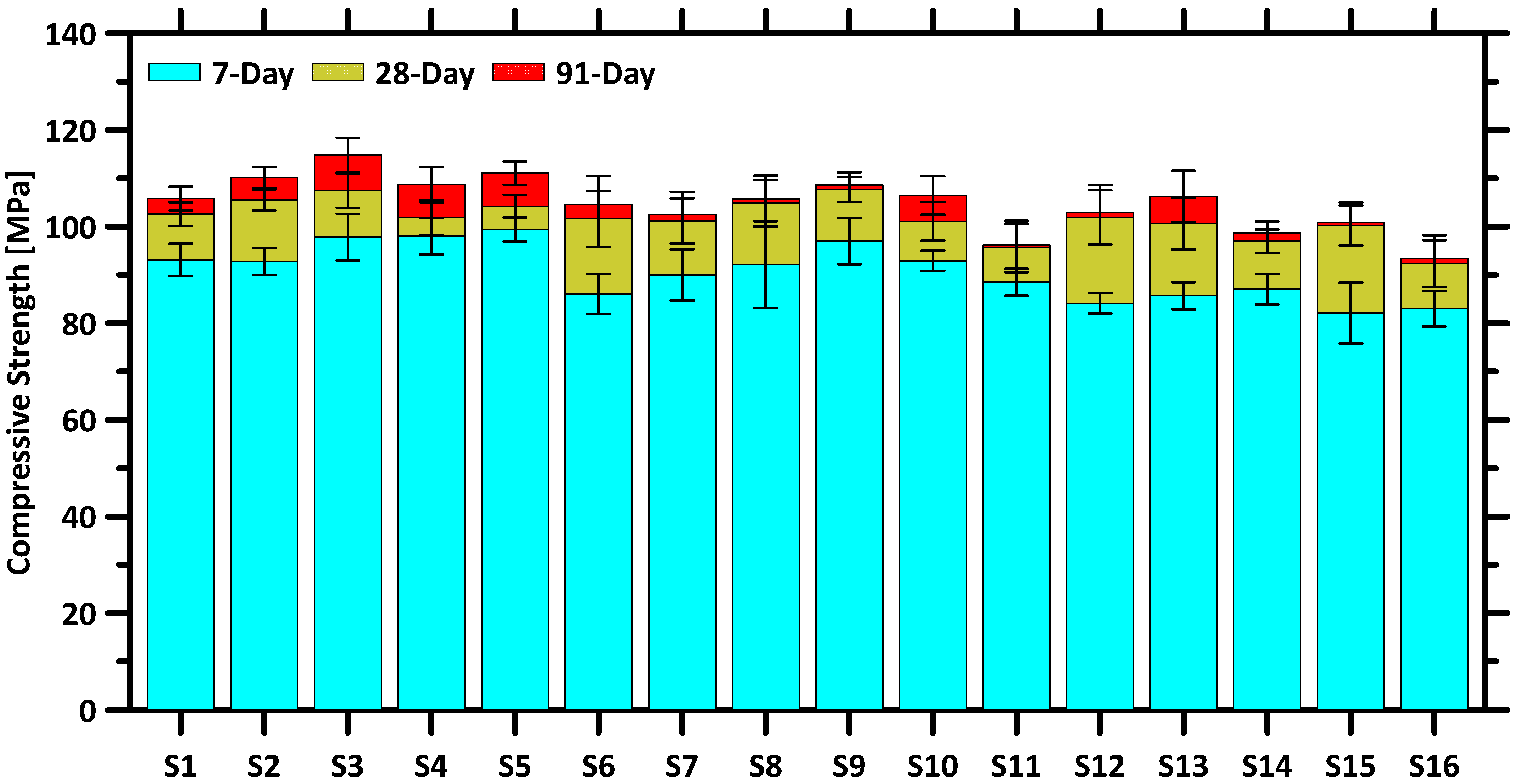

The compressive strengths of the concrete at 7 days, 28 days, and 91 days are displayed in

Figure 6. In addition,

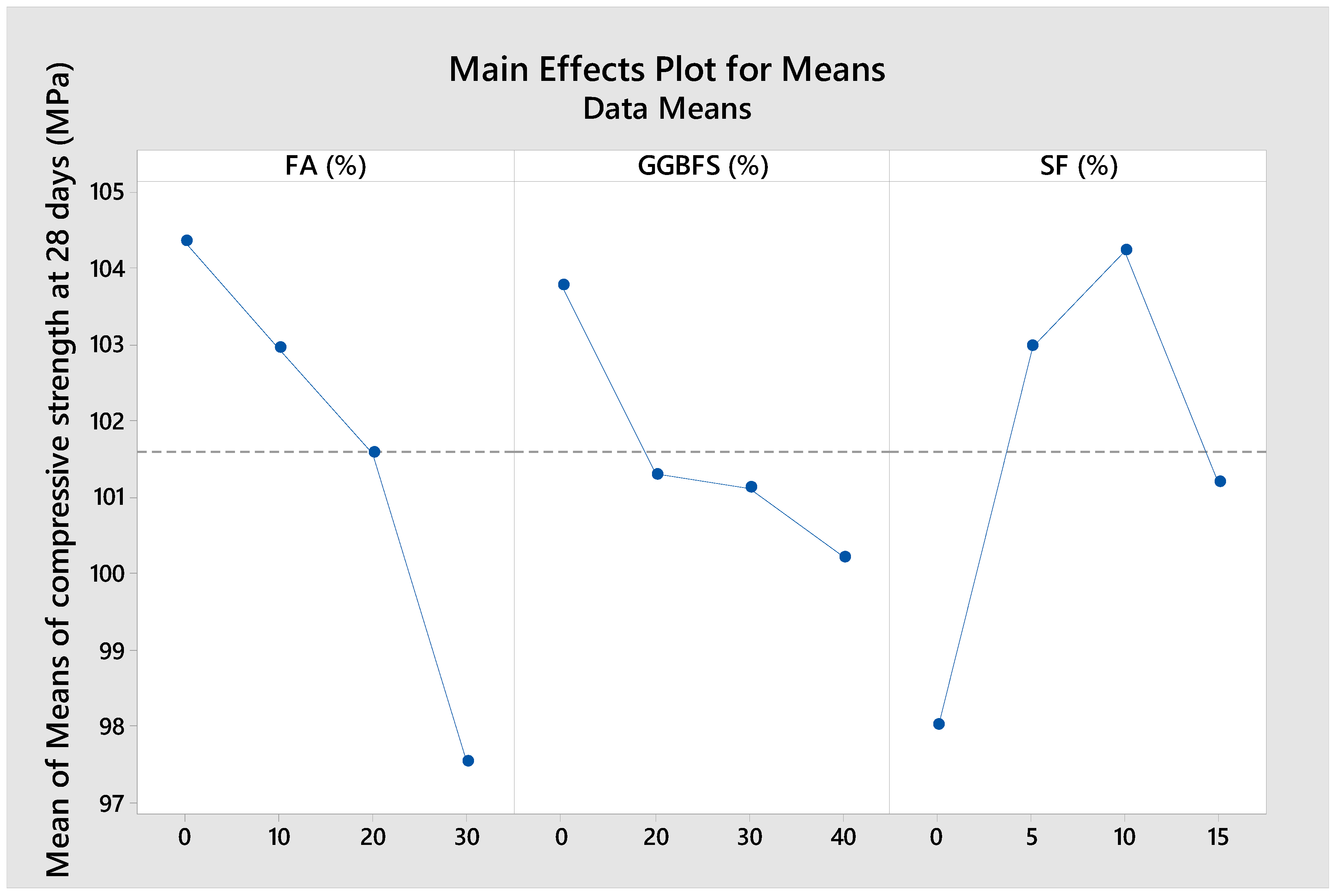

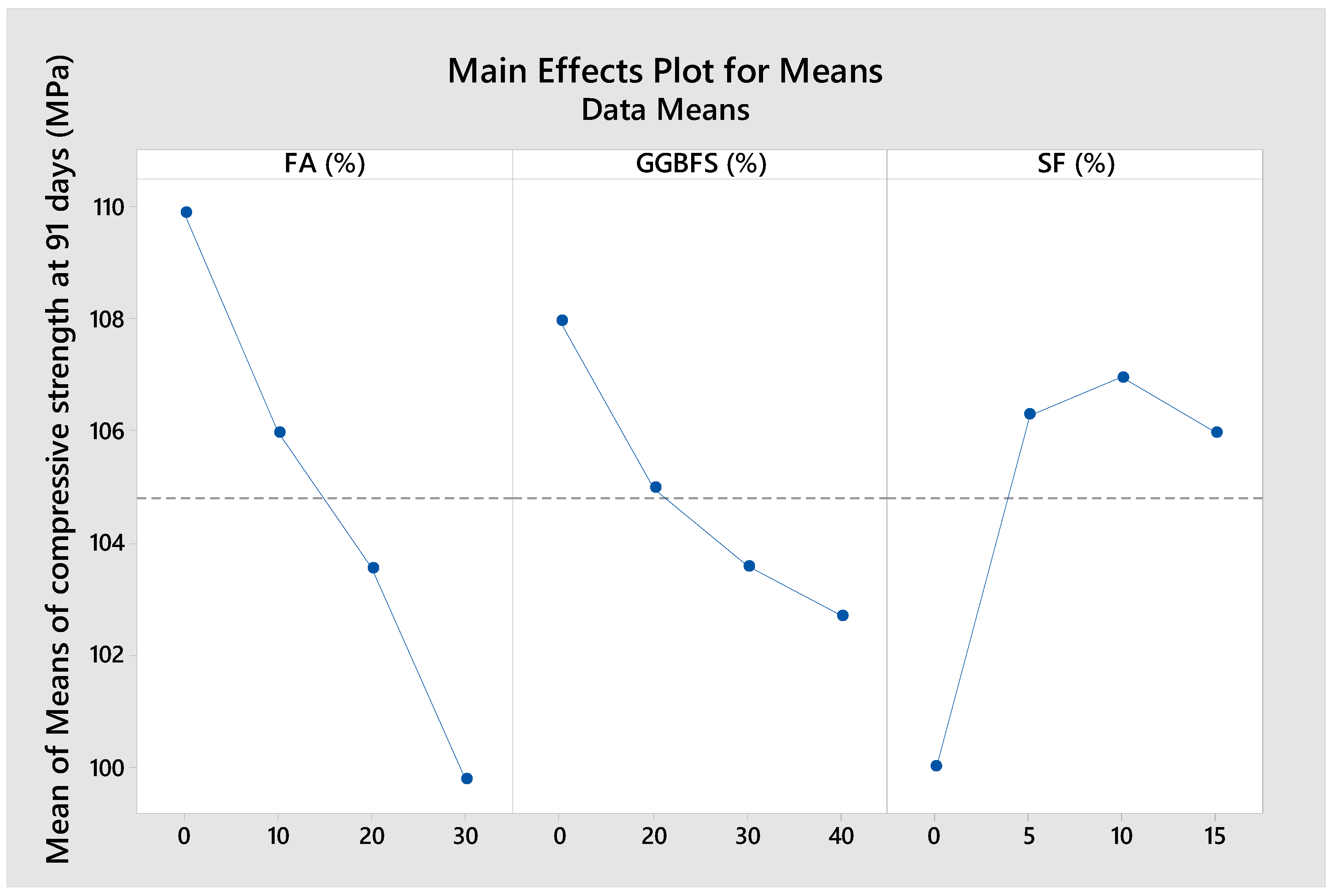

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 further illustrate the effects of each SCM on the compressive strength of the concrete samples across different curing periods. As expected, the compressive strength of the concrete increased with curing time due to the gradual densification of the matrix by hydrates produced from the hydration reaction of the cement and SCMs. Between 7 and 28 days, the rate of strength gain ranged from 4.0% to 22.2%, while after 28 days, the rate decreased significantly to between 0.5% and 6.9%. Previous studies indicated that these SCMs reacted with portlandite generated during OPC hydration to form additional calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel, thereby contributing to strength development [

57]. Generally, the replacement of OPC with GGBFS does not exceed 50% by mass in order to preserve adequate 28-day strength and durability, while FA is commonly limited to below 35% [

11]. SF is often added in amounts less than 8%, though it can be used up to 12.5% or more in certain applications [

6]. Although SCMs are generally recognized for improving concrete strength and durability, the reductions observed in this study were likely due to the high replacement levels of OPC, which may exceed the optimal thresholds for maintaining compressive performance.

As can be seen from

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the compressive strength tended to decrease with increasing amounts of FA and GGBFS, or when the SF content exceeded 10%. The relatively limited reactivity of FA compared to OPC, GGBFS, and SF [

6,

58] likely resulted in the notable reduction in compressive strength in mixtures with higher FA content. GGBFS also caused some strength loss when used as a partial OPC replacement, though the effect was less pronounced than that of FA [

59]. In addition, the high replacement level of SCMs reduced the content of OPC, thereby limiting the formation of calcium hydroxide [Ca(OH)

2] during hydration. This reduction in Ca(OH)

2 availability constrained the pozzolanic reaction of the SCMs, ultimately resulting in the decreased compressive strength of the concrete specimens. The synergistic interaction among SCMs, however, improved strength levels. As shown in

Figure 6, the control OPC mixture performed a 28-day compressive strength of approximately 102.6 MPa. Mix S5, which contained 85% OPC, 10% FA, 0% GGBFS, and 5% SF, performed a compressive strength that was higher by 1.5% compared to the OPC mixtures. Meanwhile, mix S8, with only 40% OPC, 10% FA, 40% GGBFS, and 10% SF, exhibited a slightly higher strength, outperforming the control mix by 2.2%. These results demonstrate that substantial OPC reductions, replaced by optimized SCM blends, can deliver environmental benefits without compromising mechanical performance.

As aforementioned, GGBFS contributed to both cementitious and pozzolanic reactions during the hydration of OPC. FA enhanced the strength of the mixtures by (1) providing high pozzolanic activity that generated additional hydration products, and (2) promoting its own pozzolanic reaction through filler and seeding effects [

14,

60]. SF, with finer particles and amorphous content, contributed to strength enhancement through both chemical reactions with Ca(OH)

2, forming additional C–S–H, and a micro-filler effect that improved particle packing [

61]. Mixes containing 10% SF and retaining 60–70% OPC consistently showed the highest compressive strengths throughout the curing period.

Among mixes with 10% SF, increasing FA content corresponded to lower strengths, highlighting FA’s relatively lower reactivity. The addition of SF expedites the hydration process, which is hindered at lower w/b ratios. However, SF also consumes water and creates agglomerates, leading to a fast decrease in free water for cement hydration [

23]. Consequently, when SF content exceeded an optimal threshold, compressive strength began to decline. It is also worth noting that most of the mixtures achieved compressive strengths exceeding 100 MPa, demonstrating performance comparable to that of pure OPC concrete.

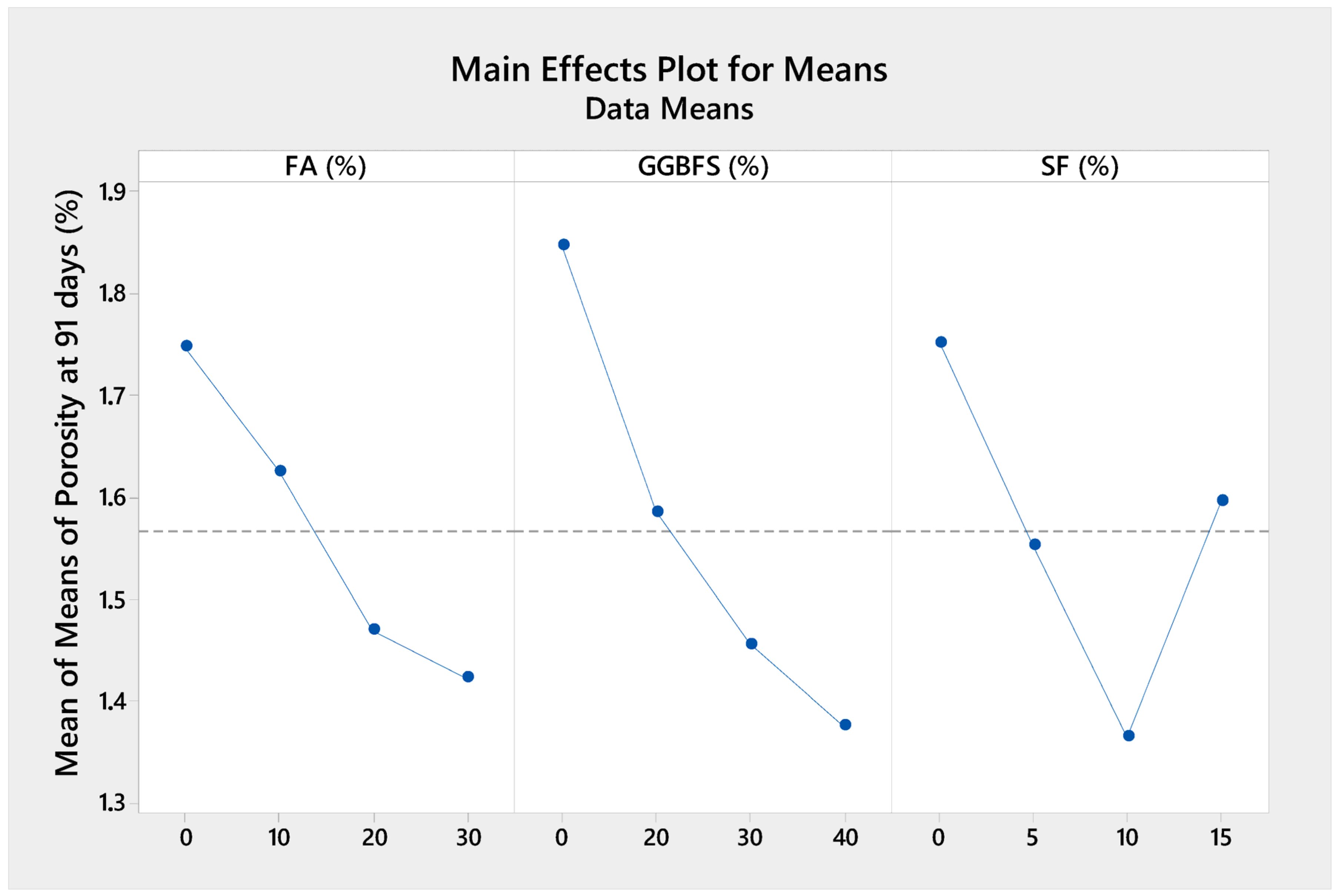

3.3. Porosity

Water absorption porosity is a key microstructural parameter that strongly influences the mechanical and durability properties of concrete.

Figure 10 illustrates the porosity of high-performance fine-grained concrete at 91 days. The water absorption porosity of the concrete samples varied between 1.24 and 2.46%, decreasing with the increasing replacement of OPC by GGBFS and FA, which can be explained by the fact that more porous concretes have a less dense matrix, which weakens the overall structure. Although the inclusion of GGBFS and FA reduced OPC content and theoretically should have enhanced the long-term matrix refinement through pozzolanic activity, their relatively lower reactivity compared to OPC resulted in the slower development of hydration products [

58]. This delayed reaction led to the presence of unreacted particles and increased the amount of permeable voids in the concrete, thereby elevating the porosity of the samples containing higher proportions of FA and GGBFS. In contrast, the incorporation of SF had a significant densifying effect on the concrete matrix. Due to its ultrafine particle size, SF acted as a micro-filler, effectively filling voids between cement particles and reducing capillary porosity. Moreover, its high pozzolanic reactivity enabled it to rapidly react with the Ca(OH)

2 released during OPC hydration, forming additional C–S–H gel and further densifying the matrix [

61]. This dual effect, both physical and chemical, contributed to a substantial reduction in porosity, particularly when SF was used at optimal levels. Thus, while GGBFS and FA have potential long-term benefits for durability, their high replacement levels in this study may have exceeded the optimal range for microstructural improvement, especially within the 91-day curing period. Meanwhile, the positive impact of SF on porosity aligned well with the observed enhancements in compressive strength, reinforcing the importance of balanced SCM proportions in high-performance concrete design. However, it also consumed available free water for cement hydration by forming agglomerates, especially at low w/b ratios [

23], thus creating more porosity in the mortar matrix.

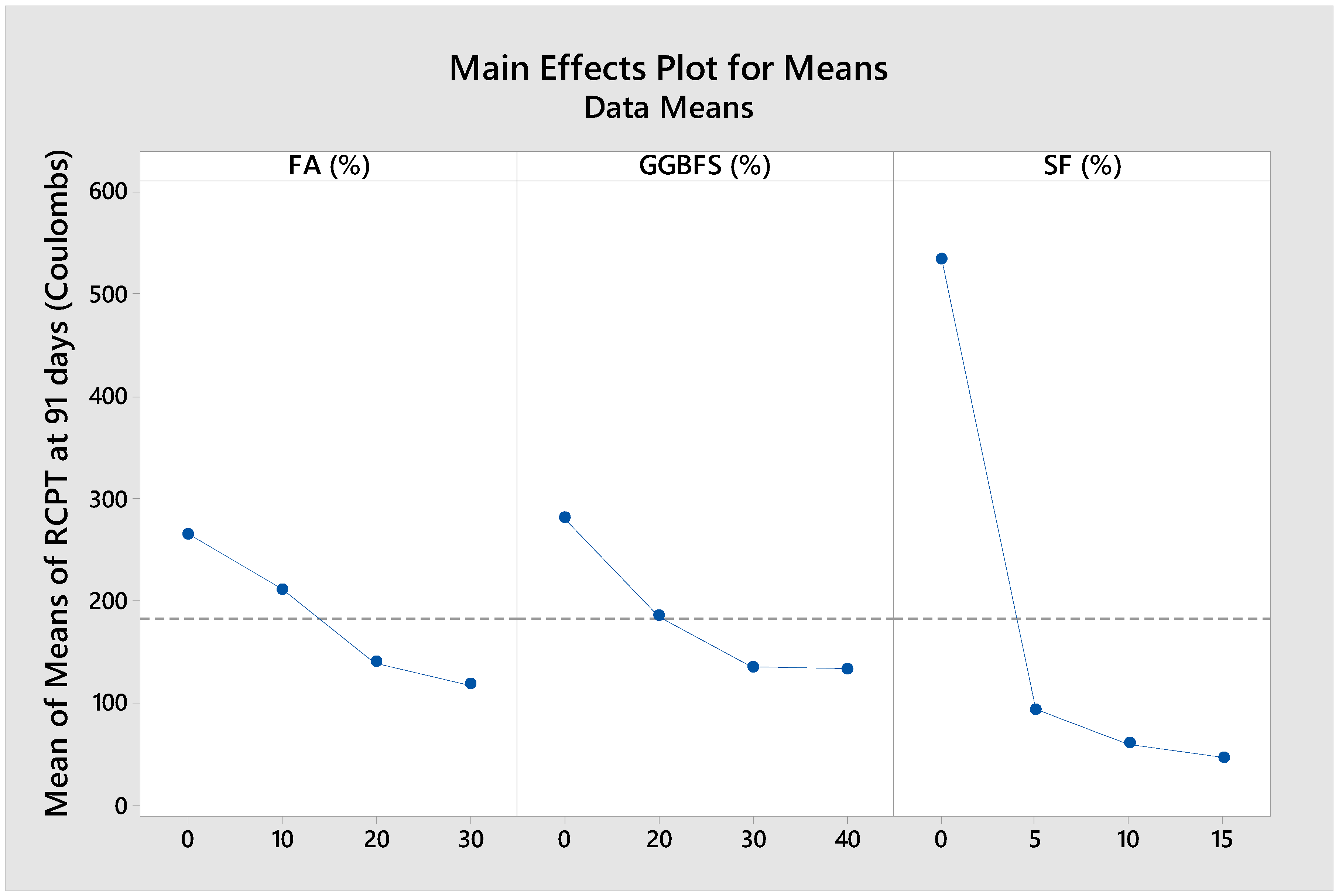

3.4. RCPT

RCPT is a widely used indicator of concrete’s resistance to chloride ion penetration, which is critical for assessing durability, especially in structures exposed to marine environments.

Figure 11 illustrates the impact of FA, GGBFS, and SF on the RCPT of the concrete mixtures at 91 days. As evident from the figure, the incorporation of SCMs significantly reduced the RCPT values compared to the control mix, composed solely of OPC. At 91 days, all concrete specimens exhibited excellent chloride ion penetration resistance, as indicated by RCPT values below 600 Coulombs. According to Sengui et al. [

62], SCMs influenced concrete through two primary mechanisms: the pozzolanic effect and the filler effect. The pozzolanic effect involved the chemical reaction between the SCMs and Ca(OH)

2, a byproduct of OPC hydration. This reaction produced additional C–S–H, which filled capillary pores and contributed to matrix densification. Meanwhile, the filler effect occurred when the fine particles of SCMs physically occupied voids within the mix, improving particle packing and reducing pore connectivity. In particular, concrete mixes containing optimal proportions of SF demonstrated the lowest RCPT values, indicating a highly impermeable matrix. The incorporation of SF has been widely recognized in the literature as the most effective strategy for improving resistance to chloride ion penetration, primarily due to its ability to partially obstruct transport pathways [

63], refine pore size and distribution [

64], and enhance the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) [

65], among other mechanisms. As aforementioned, high SF dosage may cause particle agglomeration and increase porosity in the mortar matrix, thereby slightly elevating RCPT values. Furthermore, while high-volume replacement with SCMs did not fully contribute to the pozzolanic reaction, their physical filling effect improved the microstructure, thereby reducing chloride ion transport and enhancing the resistance of the concrete specimens to chloride penetration.

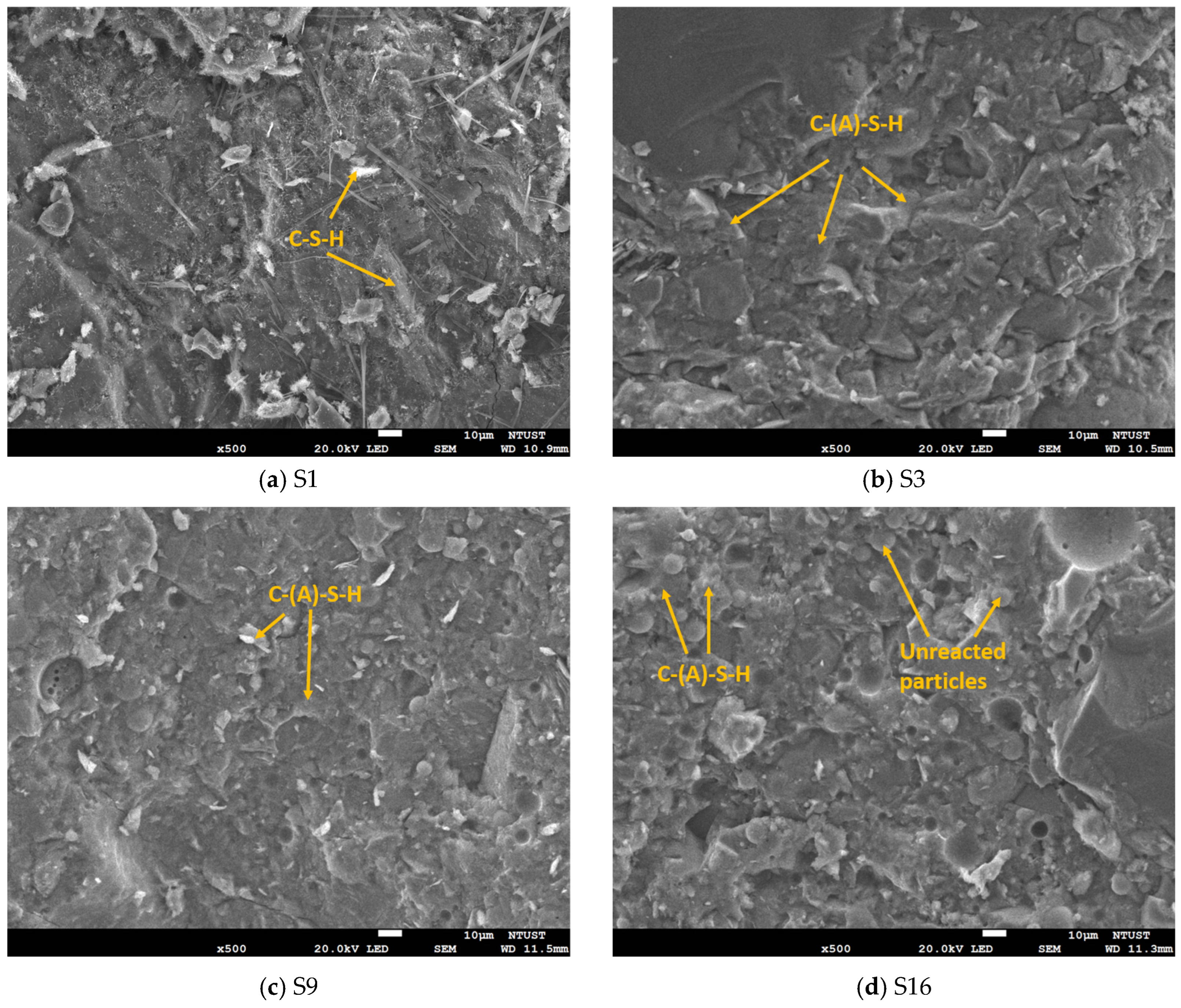

3.5. SEM/EDS

Figure 12 illustrates the SEM images of fine-grained HPC S1, S3, S9, and S16 with varied FA, GGBFS, and SF contents at 28 days. The SEM analysis revealed that the dense microstructure observed in the four mixtures correlates with the previously indicated high compressive strength values. The SEM images of mixtures S1, S3, and S9 revealed compact and homogeneously distributed hydration products with minor visible pores. These features are indicative of a well-developed microstructure, consistent with the high compressive strength values recorded for these mixes at the same curing age. The dense matrix observed was largely attributed to the synergistic effects of SCMs in enhancing particle packing and producing additional C–S–H gel through pozzolanic reactions. In particular, the presence of SF significantly refined the pore structure, acting both as a micro-filler and as a highly reactive pozzolan that consumed Ca(OH)

2 to form more C–S–H, thus contributing to strength gain and matrix densification.

In contrast, the SEM image of mixture S16 displayed a less compact microstructure, characterized by visible voids and a higher presence of unhydrated particles. This could have been caused by incomplete or delayed hydration processes, likely due to excessive replacement levels of OPC with less reactive SCMs such as FA. As previously discussed, FA reacts more slowly compared to OPC, GGBFS, and SF, and when used in higher quantities, can result in reduced early-age reactivity and consequently, a more porous matrix. This microstructural deficiency explains the relatively lower compressive strength observed in S16, despite the potential long-term benefits of FA in improving durability. Moreover, the unhydrated particles visible in S16 may also indicate suboptimal mix proportions that hindered full hydration. These observations reinforce the importance of optimizing the replacement levels and balance between different SCMs to ensure adequate hydration and a dense microstructure.

3.6. Discussion

The contribution of FA, GGBFS, and SF levels to the compressive strength of fine-grained HPC at 28 days was rigorously assessed through analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Minitab R 18.1 based on the experimental data from 16 distinct mix designs. This statistical approach allowed for a systematic assessment of how each SCM contributed to the strength development at 28 days.

Table 5 presents the ANOVA results, offering valuable insight into the individual and collective effects of the SCMs. The Degrees of Freedom (DF) represent the number of independent values that can vary without violating model constraints, offering insight into the complexity of each term. The sum of squares (SS) represents how far data points deviate from the mean value. A higher value suggests greater variation in the data, while a smaller value shows that the data points are more closely clustered around the mean. The Adjusted Sum of Squares (Adj SS) quantifies the amount of variation each factor explains in the response variable, while accounting for the presence of other predictors. This is further normalized through the Adjusted Mean Square (Adj MS), obtained by dividing the Adj SS by the corresponding DF, providing an average measure of variation explained per degree of freedom. The F-Value serves as a critical test statistic, indicating the ratio of variance explained by a specific factor to the unexplained (residual) variance—higher values typically point to more influential factors. Finally, the

p-Value reveals the statistical significance of each term, with values below 0.05 denoting a meaningful influence on the response variable [

66].

From the analysis, it was evident that FA and SF contents significantly impacted the 28-day compressive strength, as both exhibited p-values below 0.05. In contrast, the effect of GGBFS was not statistically significant, with a p-value exceeding 0.05. The respective contributions of FA, GGBFS, and SF to the total variance in compressive strength were 41.25%, 10.97%%, and 34.47%, respectively. These values indicate the percentage of the total variation in compressive strength that can be attributed to changes in the respective SCM contents, suggesting that FA content played a dominant role in influencing the strength outcomes of the studied mixtures. The low reactivity of FA can lead to a significant loss in fine-grained HPC; therefore, the content of this SCM should be limited to maintain the strength of the fine-grained HPC. GGBFS, on the other hand, even being used at 40%, still resulted in a slight reduction in strength, indicating that this SCM was more reactive and participated effectively in hydrate generation. Additionally, SF, due to its finer particles and amorphous silica content, when utilized up to the optimal level, can significantly enhance the fine-grained HPC’s compressive strength; however, exceeding this level results in a considerable reduction in this contribution.

To evaluate the stability and performance of the response, the General Linear Model (GLM) was initially employed to estimate the major effects of each factor. The model demonstrated a strong fit for capturing the main effects, making it a valuable tool for preliminary analysis. However, the shortcoming of this approach lies in its inability to effectively capture complex interactions between factors. To address this shortcoming and provide a more robust representation of the system behavior, a quadratic regression model was subsequently developed.

The equations were constructed using Minitab software in two steps:

First, we constructed a full quadratic regression model, including all possible main effects and interactions, based on 16 experimental data points.

- ○

To ensure the model’s compactness and statistical significance, we applied the Stepwise Regression method. Variables with a

p-value> 0.05 (not statistically significant) were systematically removed. The final equation in

Table 7 retained only statistically significant predictor variables (

p < 0.05) to optimize prediction accuracy.

Table 7.

Final Regression Analysis: 28-day compressive strength versus FA (%). GGBFS (%). SF (%).

Table 7.

Final Regression Analysis: 28-day compressive strength versus FA (%). GGBFS (%). SF (%).

| Analysis of Variance |

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | p-Value |

| Regression | 4 | 207.93 | 51.981 | 13.28 | 0.000 |

| FA (%) | 1 | 94.83 | 94.830 | 24.22 | 0.000 |

| GGBFS (%) | 1 | 26.27 | 26.274 | 6.71 | 0.025 |

| SF (%) | 1 | 81.35 | 81.348 | 20.78 | 0.001 |

| SF (%) × SF (%) | 1 | 63.60 | 63.601 | 16.25 | 0.002 |

| Error | 11 | 43.06 | 3.915 | | |

| Total | 15 | 250.99 | | | |

| Model Summary |

| S | R-sq | R-sq(adj) | R-sq(pred) |

| 1.97861 | 82.84% | 76.60% | 66.59% |

| Coefficients |

| Term | Coef | SE Coef | T-Value | p-Value | VIF |

| Constant | 103.21 | 1.39 | 74.17 | 0.000 | |

| FA (%) | −0.2178 | 0.0442 | −4.92 | 0.000 | 1.00 |

| GGBFS (%) | −0.0866 | 0.0334 | −2.59 | 0.025 | 1.00 |

| SF (%) | 1.412 | 0.310 | 4.56 | 0.001 | 12.25 |

| SF (%) × SF (%) | −0.0798 | 0.0198 | −4.03 | 0.002 | 12.25 |

| Regression Equation |

| Rn28-day = 103.21 − 0.2178 FA (%) − 0.0866 GGBFS (%) + 1.412 SF (%) − 0.0798 SF (%) × SF (%) |

| Fits and Diagnostics for Unusual Observations |

| Obs | Rn28-day | Fit | Resid | Std Resid | |

| 14 | 97.00 | 101.09 | −4.09 | −2.s39 | R |

Despite the initial inclusion of quadratic and interaction terms in the regression model, the statistical analysis revealed that several of these terms—namely FA(%) × FA(%), GGBFS(%) × GGBFS(%), FA(%) × GGBFS(%), and FA(%) × SF(%)—exhibited

p-values exceeding 0.05, indicating they were statistically insignificant contributors to the response. To enhance model parsimony and interpretability, these terms were systematically eliminated through a stepwise regression procedure, wherein variables were retained in order of their statistical significance and contribution to model fit. The refined model resulting from this iterative selection process is summarized in

Table 7. While this streamlines and effectively predicts the response variable, it still does not adequately capture the interactive effects between factors.

The CO

2 emissions associated with each concrete mixture were evaluated based on the quantities of raw materials used in the mix designs and the corresponding emission factors reported in the literature [

67,

68]. The assessment was normalized per unit of mechanical performance by calculating emissions per 1 MPa of 28-day compressive strength. This approach reflects the environmental efficiency of each mixture, considering not only the absolute emissions but also how effectively the concrete performs structurally. As illustrated in

Table 8 and

Table 9, all the proposed concrete mixtures incorporating the SCMs resulted in significantly lower CO

2 emissions compared to the reference mix made with 100% OPC. This reduction in emissions is primarily attributed to the partial replacement of OPC, which is known to be the most carbon-intensive component in concrete due to the calcination and energy demands involved in its production. Using higher SCMs levels significantly reduces CO

2 emissions from 35 to 65% compared to the controlled mixture.