Fault Diagnosis of Core Drilling Rig Gearbox Based on Transformer and DCA-xLSTM

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A novel T-DCAx framework is proposed for gearbox fault detection, combining dual-path convolutional attention and xLSTM with Transformer to handle noise and complex conditions.

- (2)

- DCA-xLSTM enhances key feature extraction by integrating global-local attention and long-term sequence learning, improving robustness under complex working conditions.

- (3)

- Based on the proposed DCA-xLSTM structure, the encoder of Transformer is combined with self-attention to capture global dependencies, and the T-DCAx network is proposed. In this way, the network pays attention to the overall information and improves the fault diagnosis accuracy of the proposed method.

2. Related Work

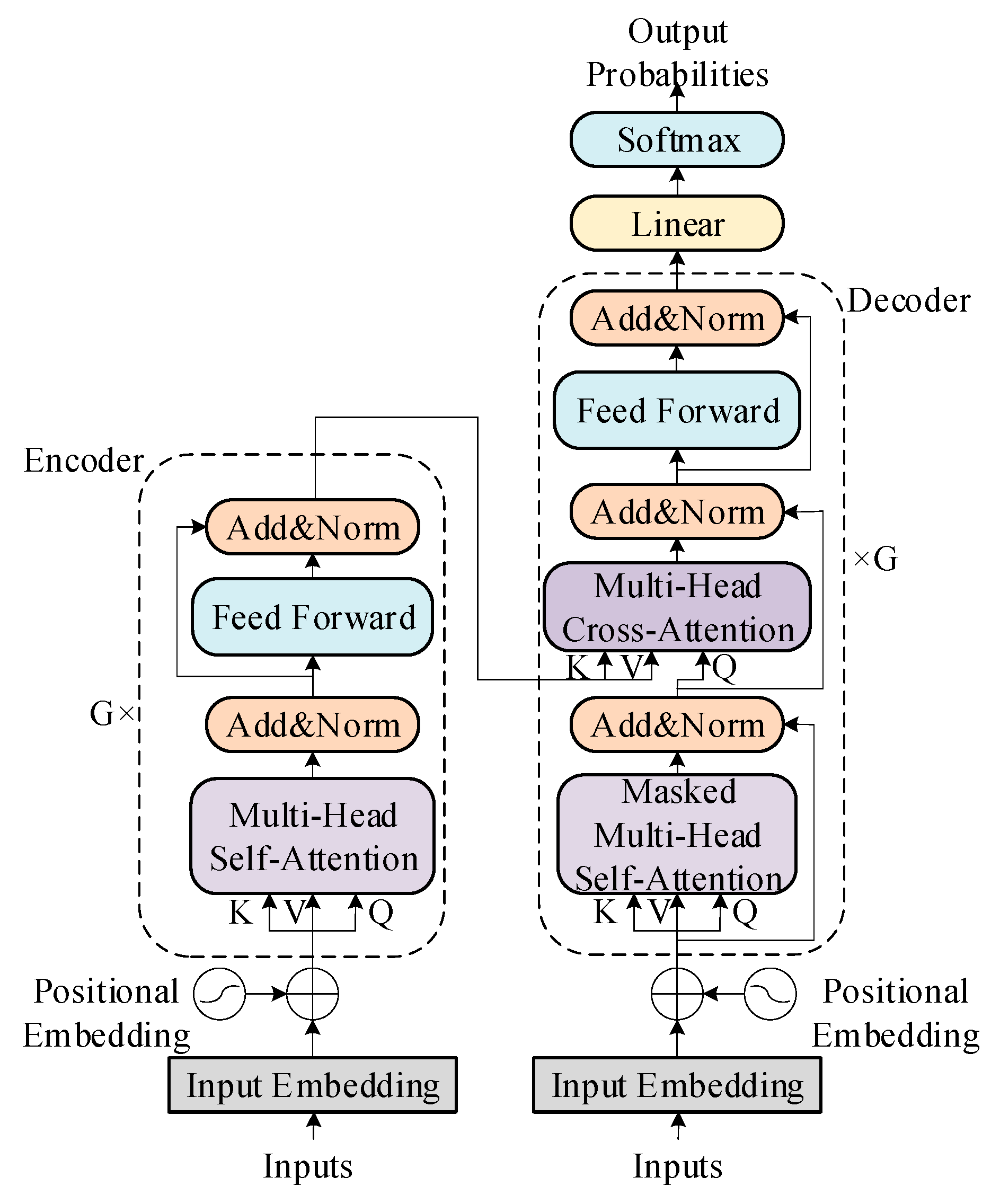

2.1. Transformer

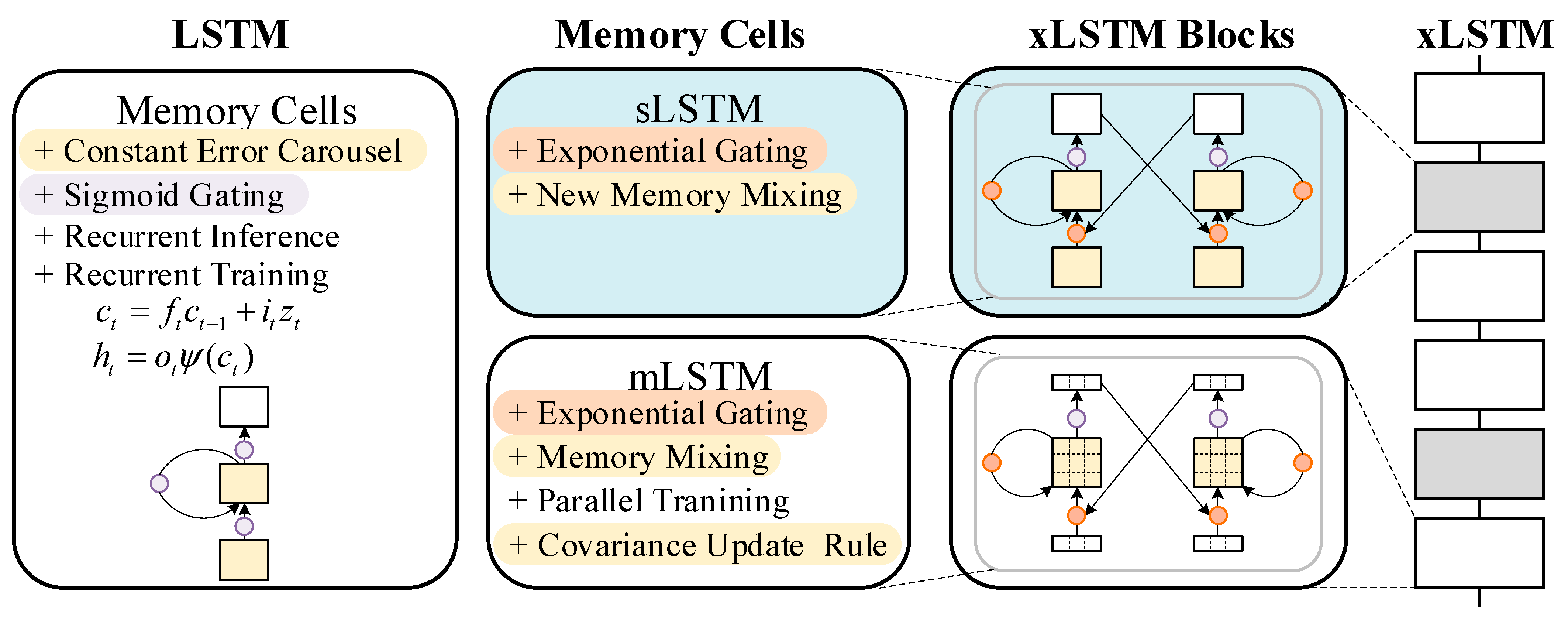

2.2. Xlstm

3. The Proposed T-DCAx Method

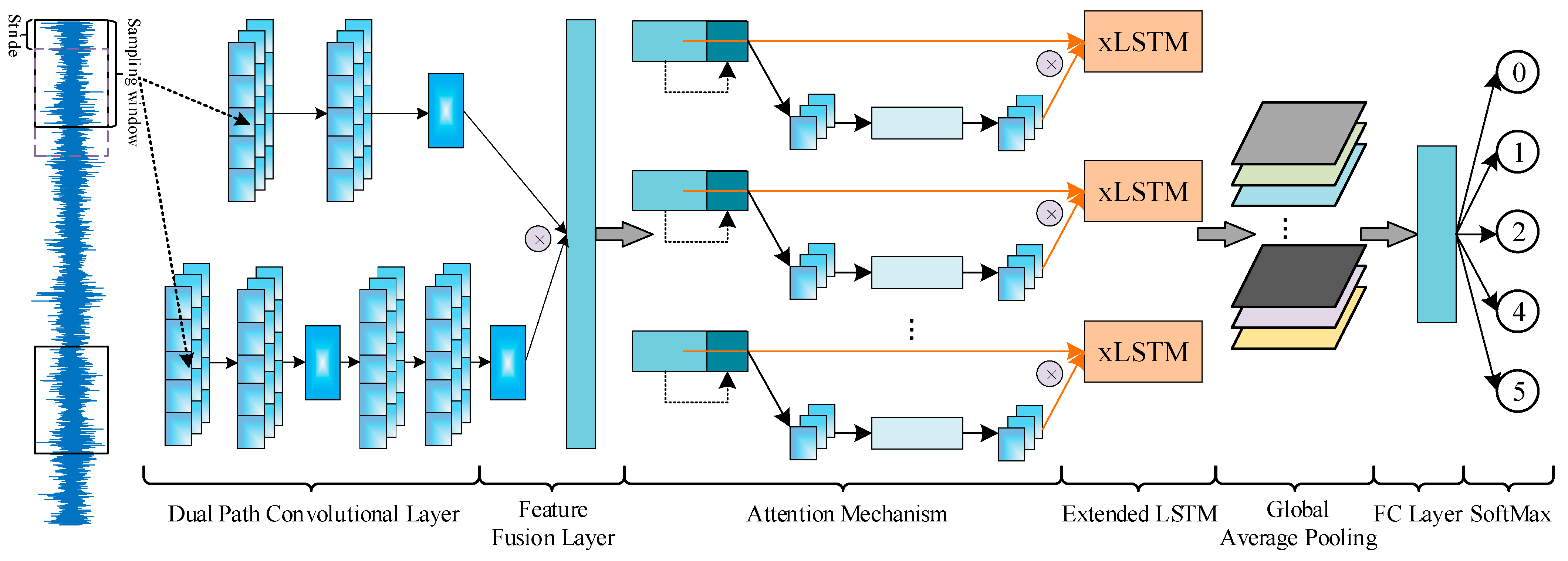

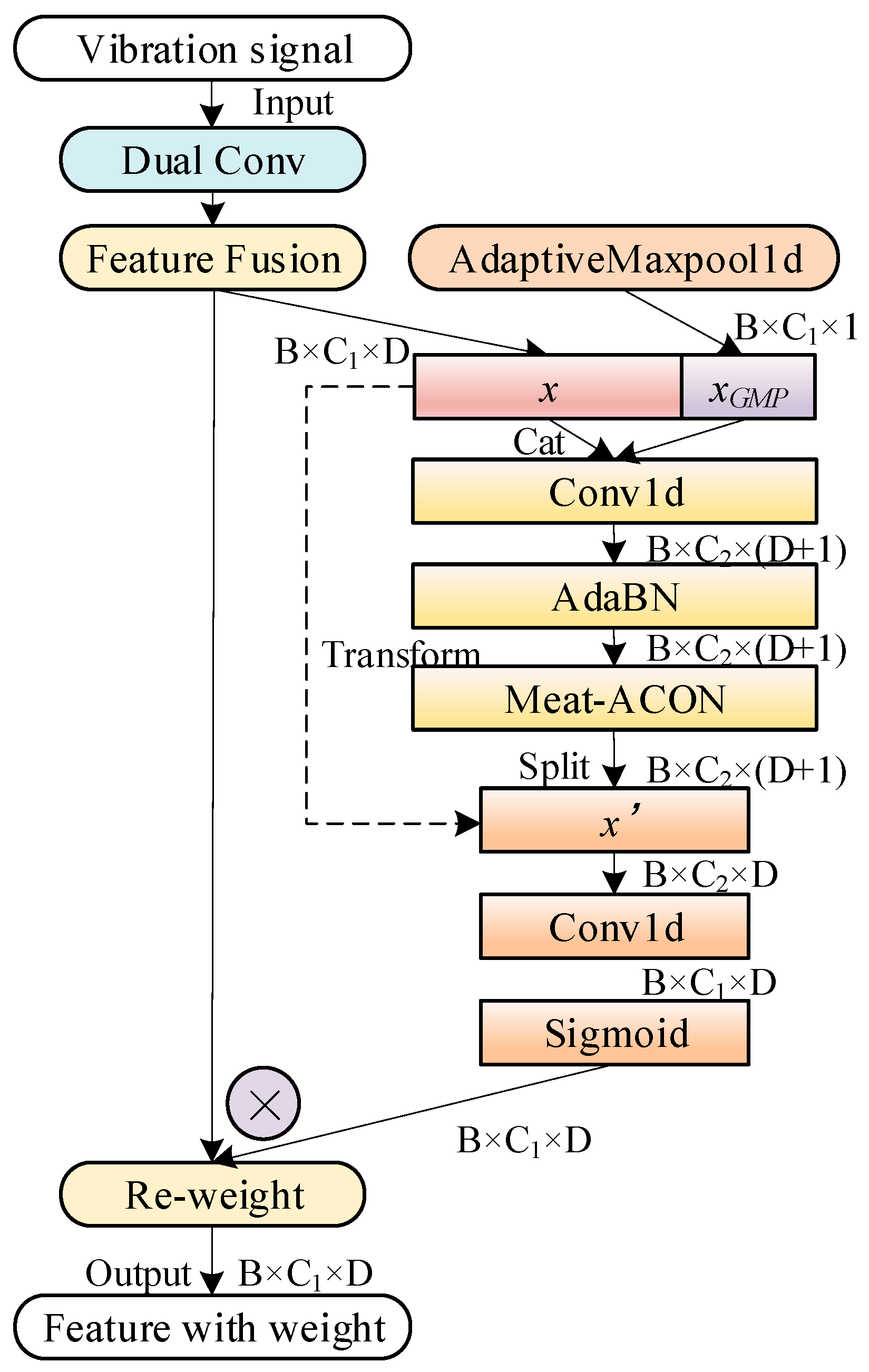

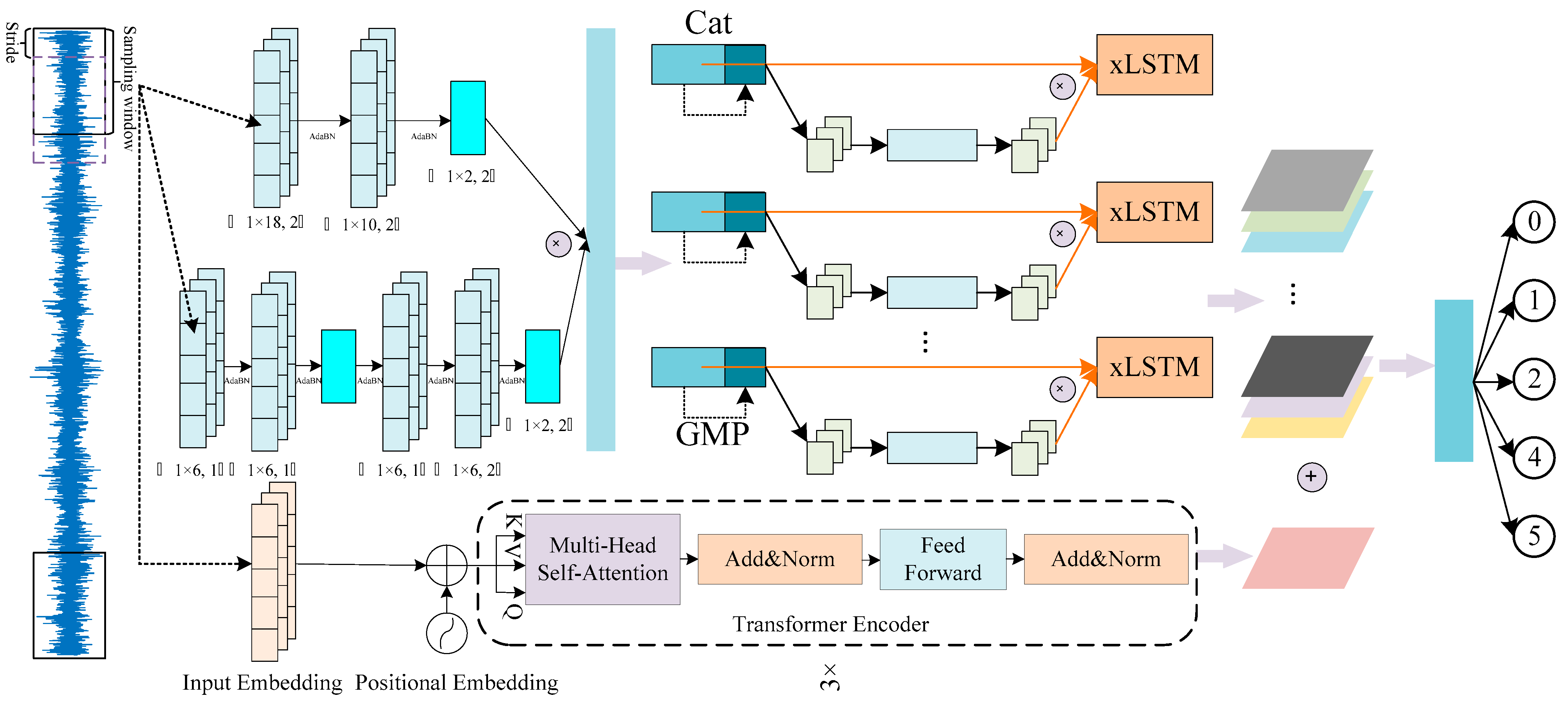

3.1. Build the DCA-xLSTM Model

3.1.1. Dual Path Convolution and Feature Fusion

3.1.2. D-Signal Attention Mechanism

3.2. Proposed the T-DCAx

- (1)

- The dual convolutional layer extracts high- and low-frequency features using large and small kernels, respectively. Large kernels enhance low-frequency learning and noise robustness, while small kernels deepen the network. Their combination enables multi-scale feature extraction for subsequent xLSTM processing. Feature fusion is performed via element-wise product.

- (2)

- In xLSTM, the mLSTM module stores multi-dimensional time-series features (e.g., vibration energy across bands), while the sLSTM module with exponential gating enhances key feature selection and suppresses noise, improving robustness.

- (3)

- The Transformer encoder complements DCA-xLSTM with multi-head attention, capturing frequency-diverse features and enhancing global context modeling.

3.3. The Overall Framework of the Proposed T-DCAx for Fault Diagnosis

- −

- First, build a dual-path convolutional attention and extended long short-term memory network (DCA-xLSTM) based on attention mechanism. xLSTM introduces exponential gating and memory structure, which improves its ability to handle long-term dependencies in time sequence and alleviates the problem of gradient disappearance.

- −

- Secondly, build a Transformer method. Transformers are good at using self-attention to capture global context and pay attention to holistic information.

- −

- Third, arrange DCA-xLSTM and Transformer in parallel, and finally fuse the output features of the two models.

4. Experimental Verifications

4.1. Experimental Data Description

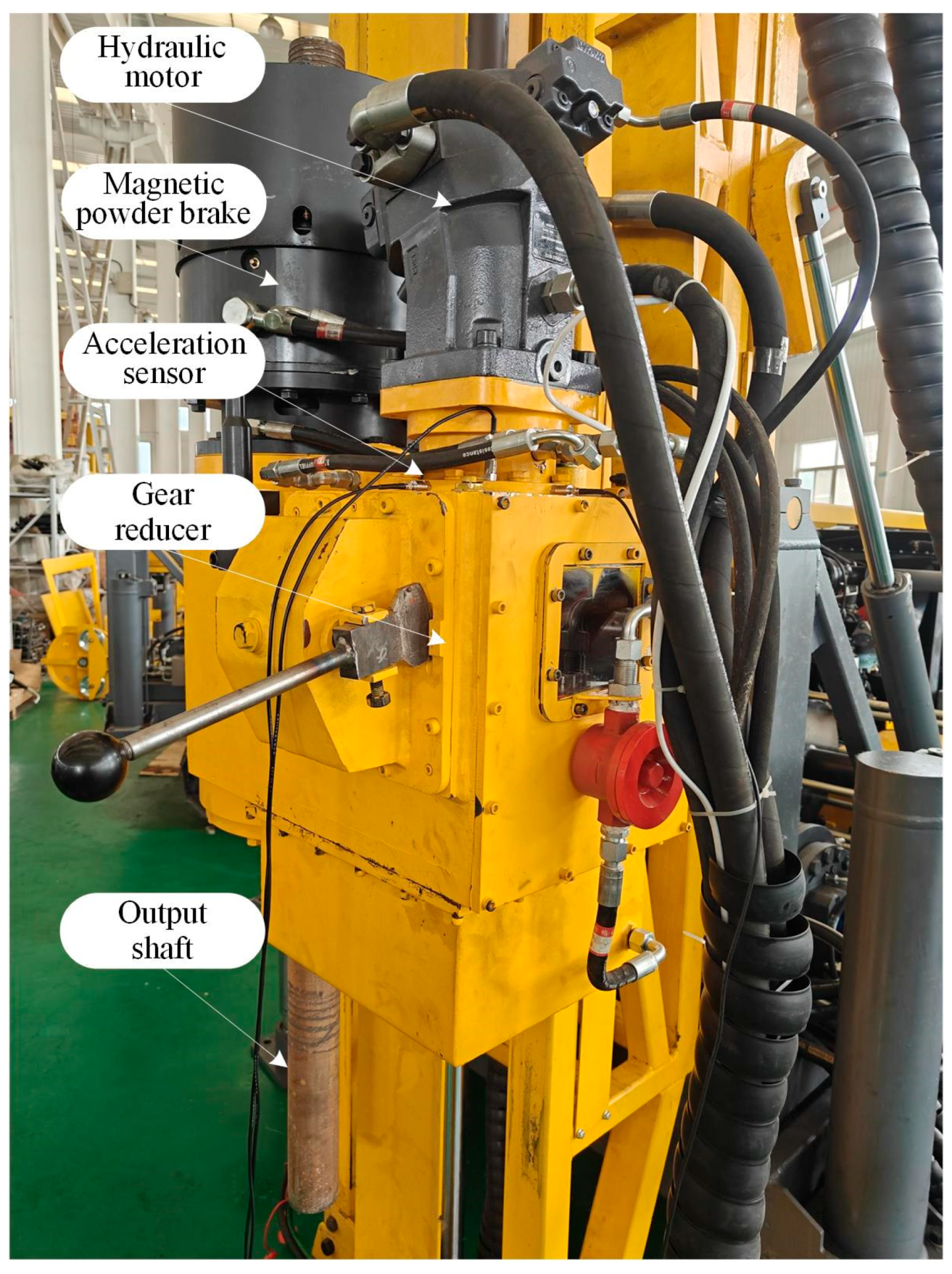

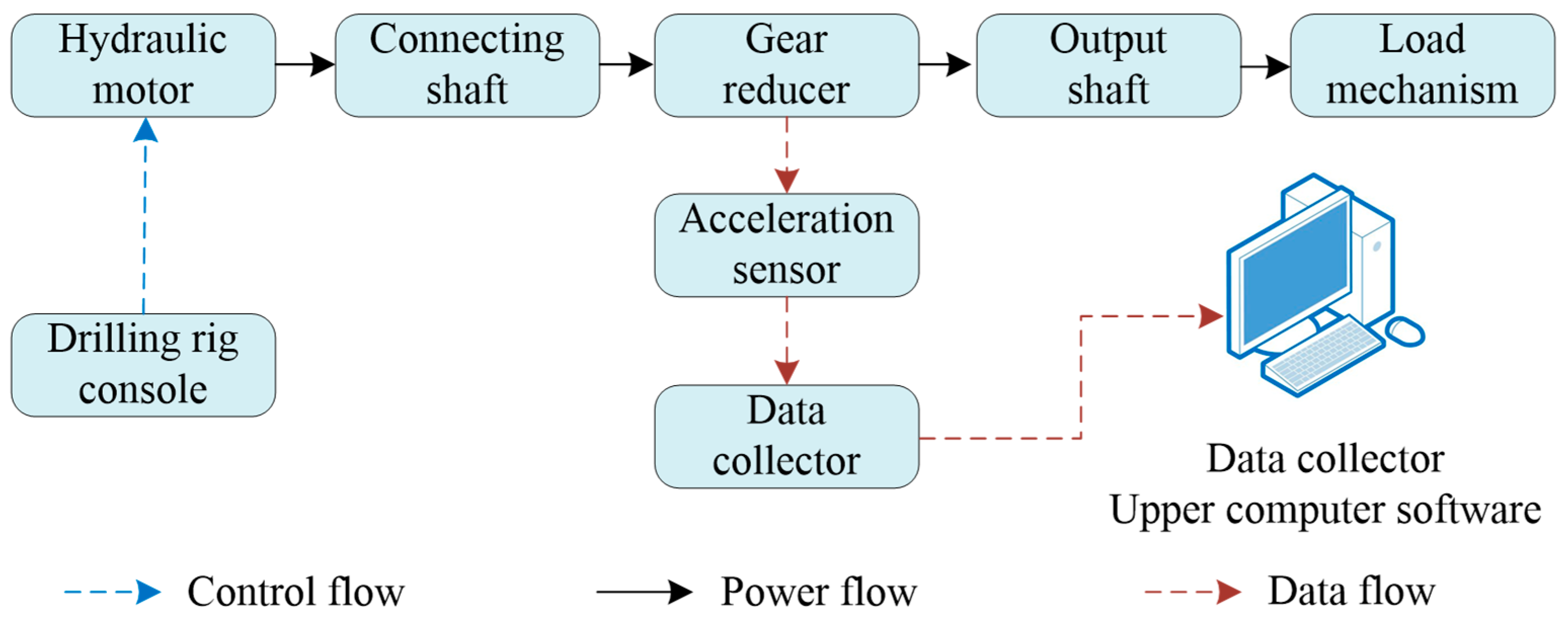

4.1.1. Experimental Platform Construction

- (1)

- Initializing the motor control unit to execute start/stop commands and dynamic speed/mode switching based on preset strategies.

- (2)

- Configuring the multi-channel signal acquisition system, including sensor calibration, sensitivity adjustment, and sampling rate settings.

- (3)

- Activating the system to collect real-time vibration signals via the acceleration sensors, transmit it to the computer through the data acquisition device, and process it using dedicated software. Experimental progress is tracked and all core parameters are archived to ensure result accuracy and repeatability.

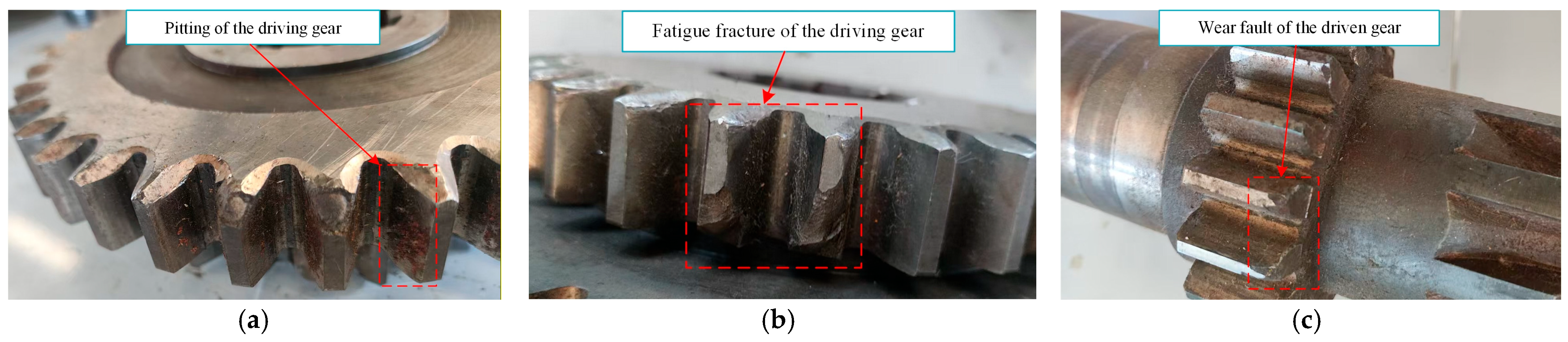

4.1.2. Experimental Design

- (1)

- Build the complete test platform. Install the gearbox and three acceleration sensors as designed, check key assembly parameters, and adjust each subsystem until stable operation is achieved.

- (2)

- Set the load torque to 0 N·m and motor speed to 590 rpm (working condition S5L0). Collect vibration signals from the faulty gearbox and repeat three times to ensure data reliability.

- (3)

- After the driving gear pitting test is completed, the machine is shut down to organize and archive the relevant vibration signals, and then the next faulty component is replaced to prepare for a new round of tests.

- (4)

- After completing the tests of all faulty components in sequence, the test platform is closed and cleaned, and all experimental data are summarized and archived to prepare for subsequent data processing, fault analysis and classification.

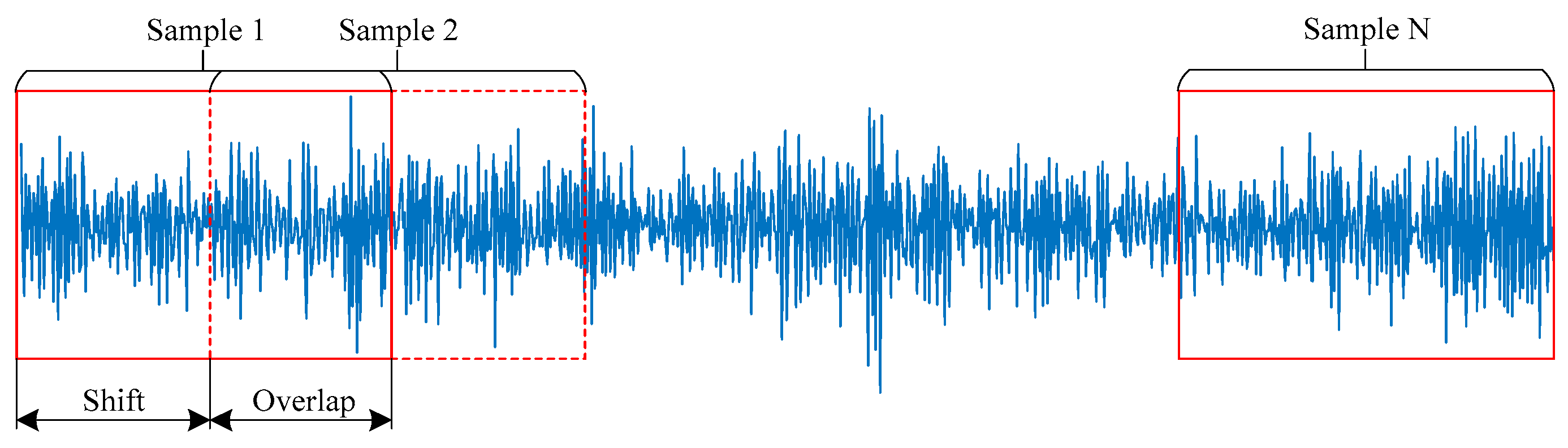

4.1.3. Dataset Settings

4.2. Experimental Environment Setting and T-DCAx Parameter Settings

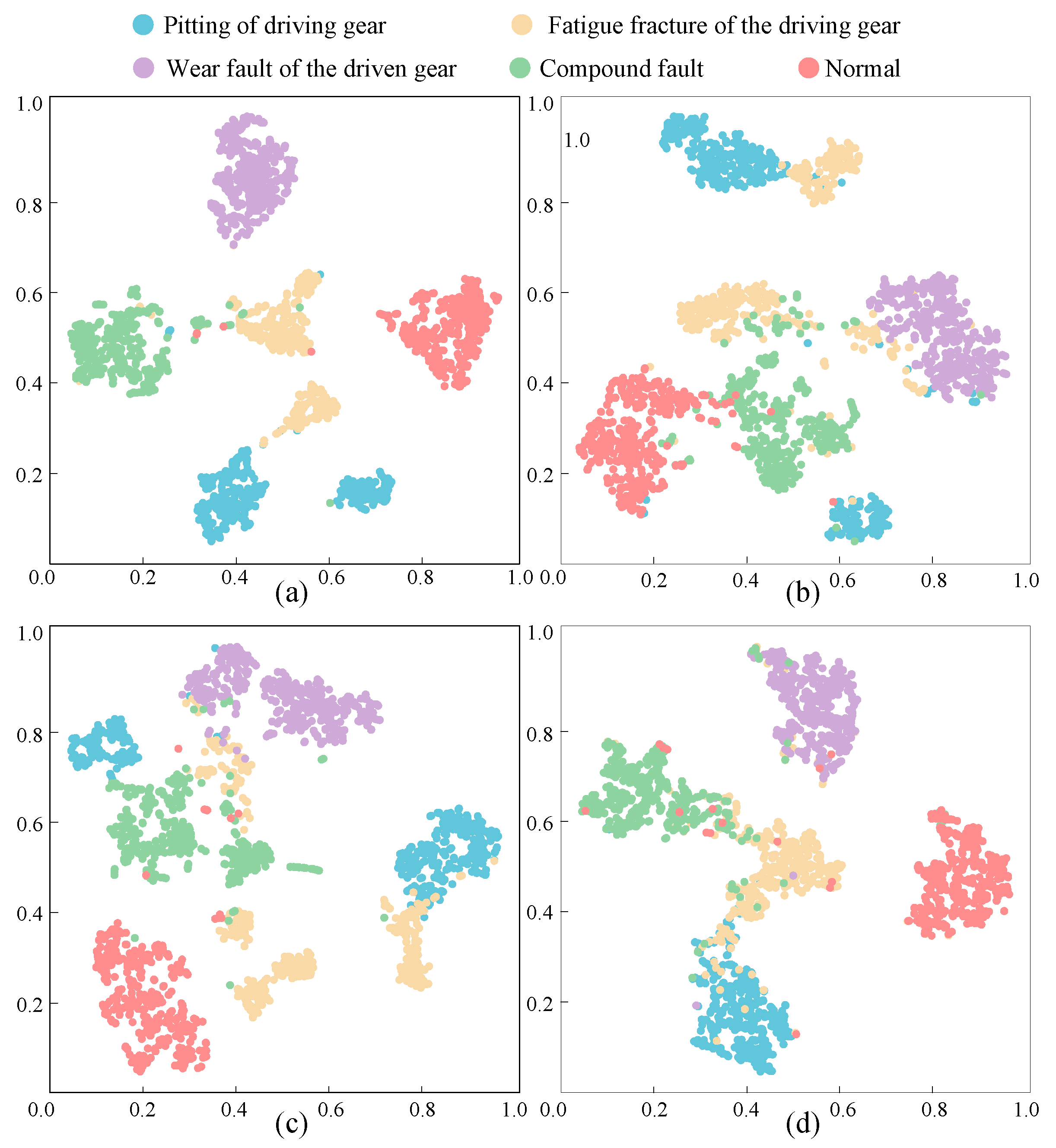

4.3. Experimental Analysis

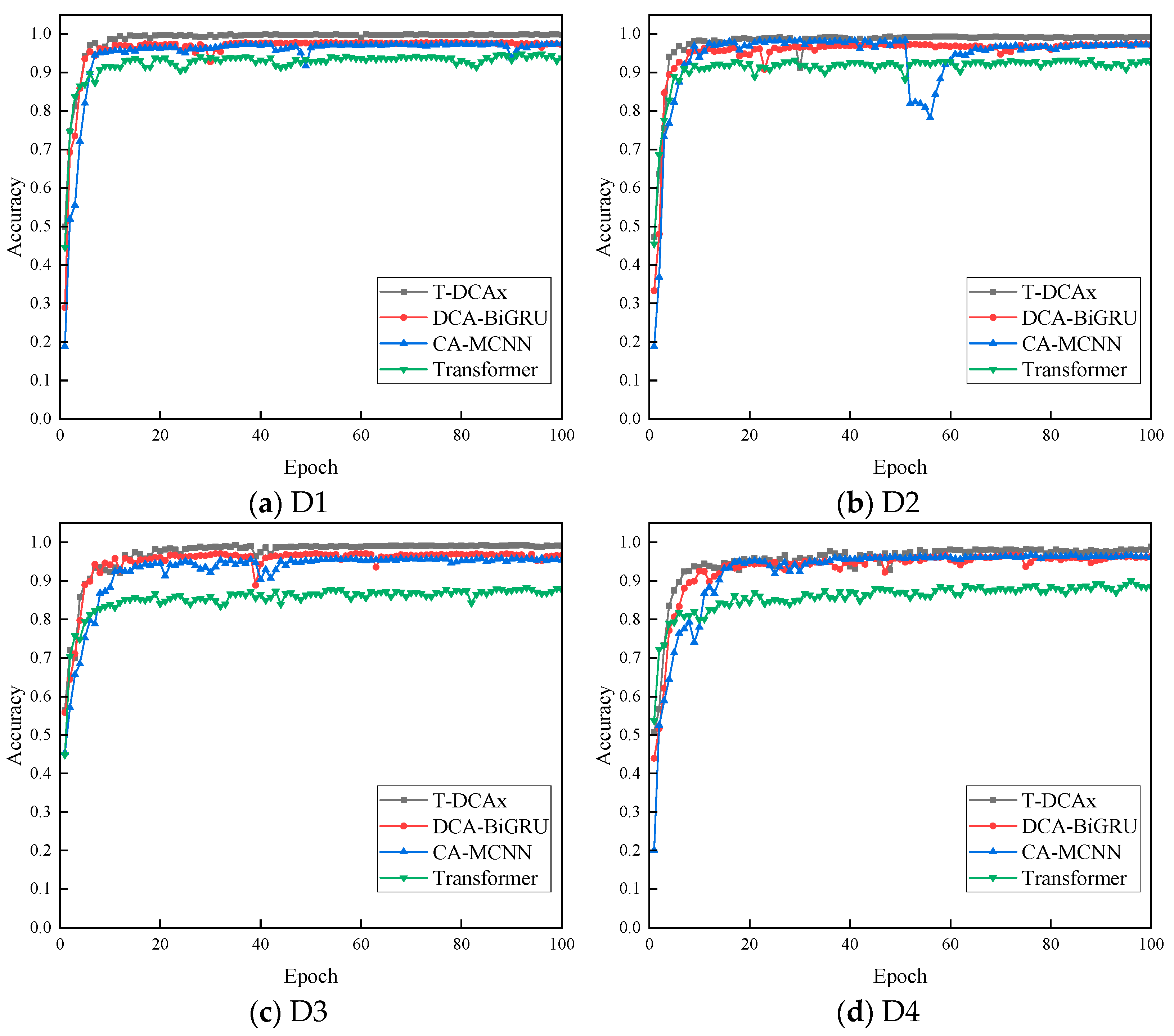

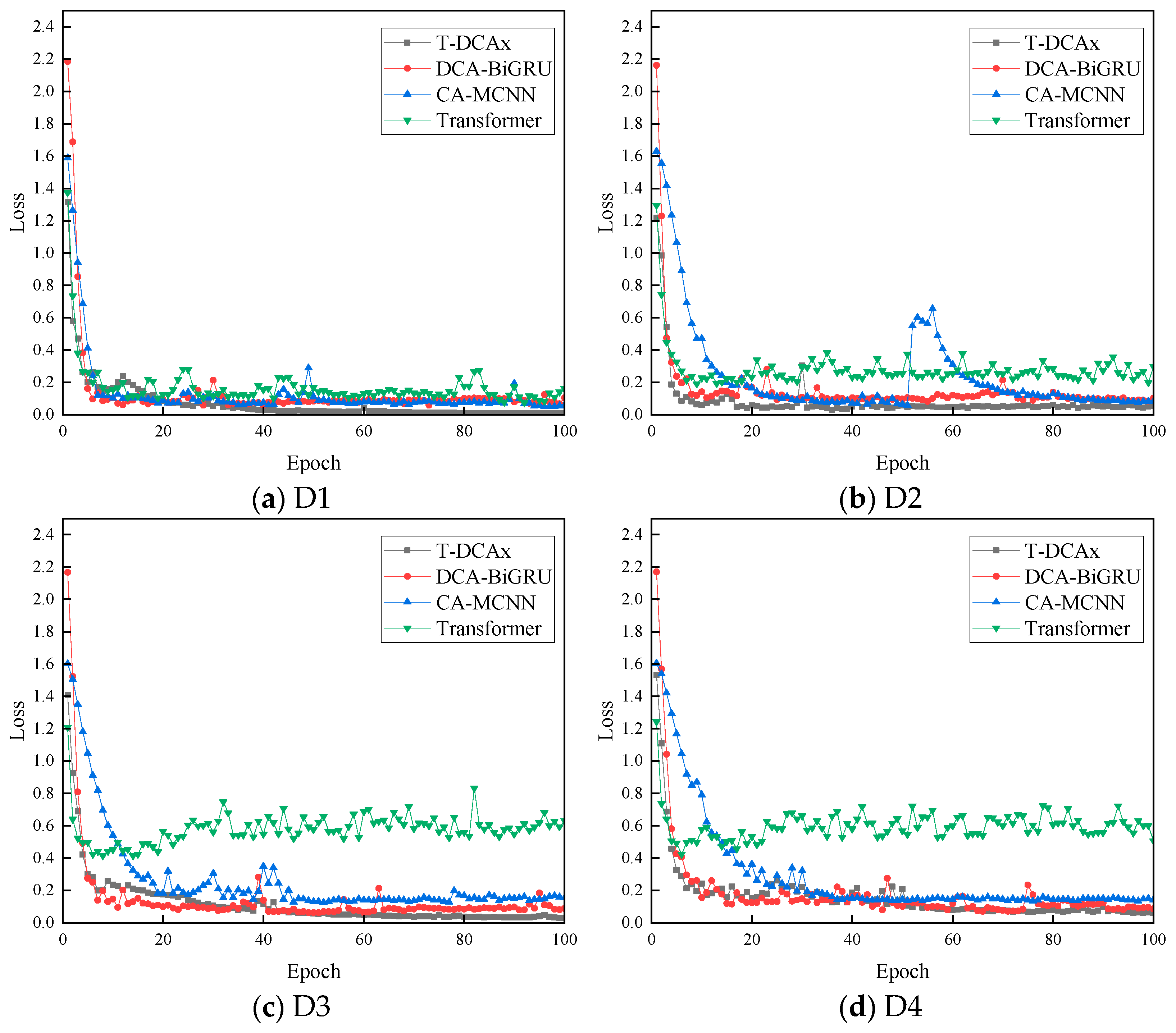

4.3.1. Comparison of Different Methods

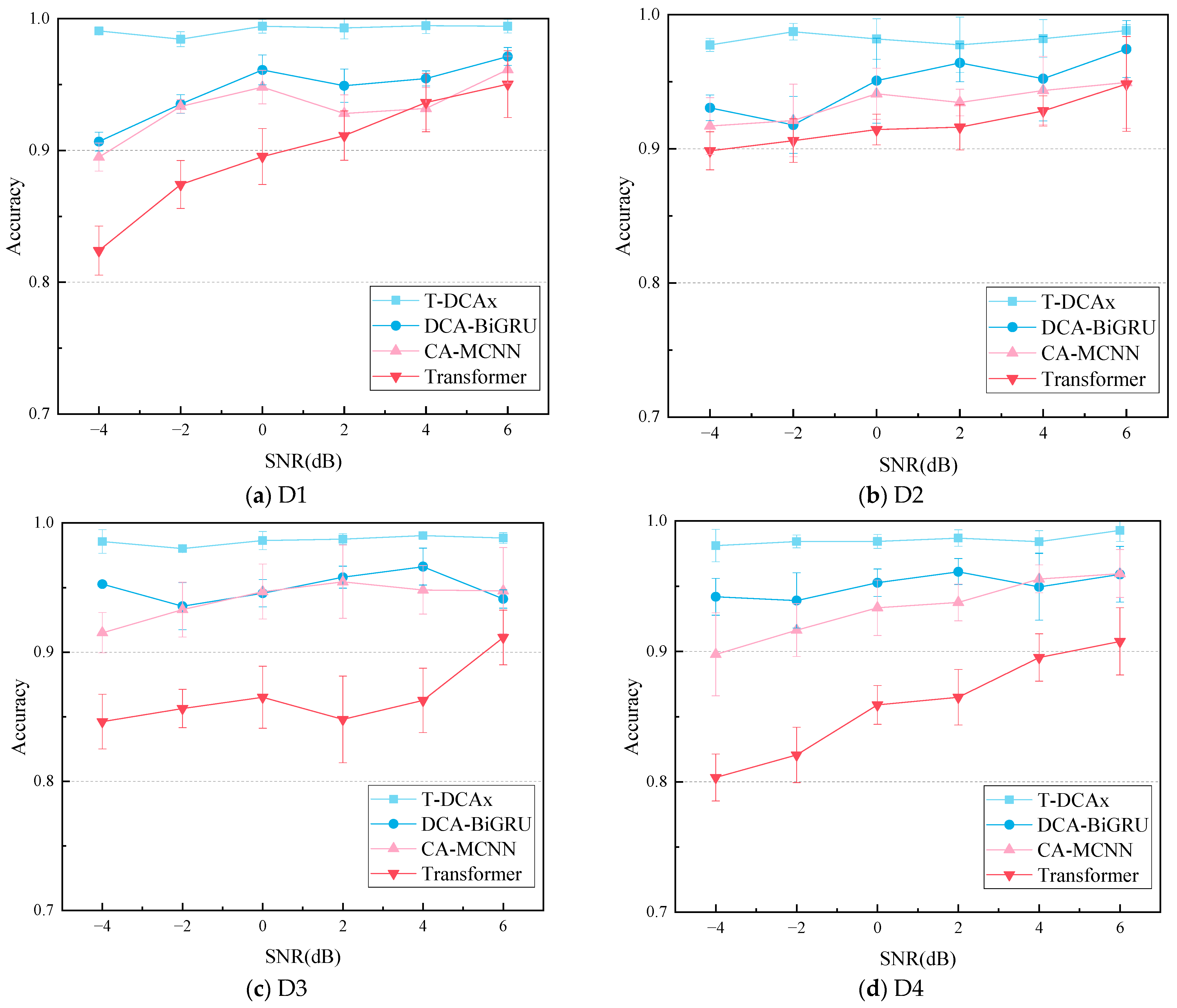

4.3.2. Experimental Verification and Analysis of Noise Immunity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WT | Wavelet transform |

| EMD | Empirical mode decomposition |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| ANN | Artificial neural networks |

| DL | Deep learning |

| AMs | Attention mechanisms |

| TST | Time series transformer |

| DCA | Dual-path convolutional attention-enhanced |

References

- Yang, Q.; Li, X.; Cai, H.; Hsu, Y.M.; Lee, J.; Yang, C.H.; Li, Z.L.; Lin, M.Y. Fault prognosis of industrial robots in dynamic working regimes: Find degradation in variations. Measurement 2021, 173, 108545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Bi, W.; Ji, G.; Zhou, B.; Zhuo, L. Deep and ultra-deep oil and gas well drilling technologies: Progress and prospect. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2022, 9, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tian, J.; Liang, P.; Xu, X.; Yu, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, D. Single and simultaneous fault diagnosis of gearbox via wavelet transform and improved deep residual network under imbalanced data. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzgec, U.; Dokur, E.; Balci, M. A novel hybrid model based on Empirical Mode Decomposition and Echo State Network for wind power forecasting. Energy 2024, 300, 131546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Shao, Y. Fast Support Vector Machine with Low-Computational Complexity for Large-Scale Classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 54, 4151–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Kim, M.K.; Fu, N.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Srebric, J. Investigating the impact of data normalization methods on predicting electricity consumption in a building using different artificial neural network models. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 118, 105570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YWu, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, W.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, X.; Fan, Y.; Cui, Y. Application of multi-scale information semi-supervised learning network in vibrating screen operational state recognition. Measurement 2024, 238, 115264. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Zhong, S.; Fu, X.; Tang, B.; Pecht, M. Deep residual shrinkage networks for fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 4681–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, O.; Slavkovikj, V.; Vervisch, B.; Stockman, K.; Loccufier, M.; Verstockt, S.; Van de Walle, R.; Van Hoecke, S. Convolutional neural network based fault detection for rotating machinery. J. Sound Vib. 2016, 377, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, D.; Hu, C. Fault detection of the gear reducer based on CNN-LSTM with a novel denoising algorithm. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 2572–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Selwi, S.M.; Hassan, M.F.; Abdulkadir, S.J.; Muneer, A.; Sumiea, E.H.; Alqushaibi, A.; Ragab, M.G. RNN-LSTM: From applications to modeling techniques and beyond—Systematic review. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Hou, L.; Chen, Y. A Time Series Transformer based method for the rotating machinery fault diagnosis. Neurocomputing 2022, 494, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wei, Q. Early kick detection based on multi-scale temporal modelling and interpretability framework. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 206, 108177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Zheng, L.; Dong, Z.; Jiao, W.; Tang, C.; Sun, J.; Xuan, Z. Recursive prototypical network with coordinate attention: A model for few-shot cross-condition bearing fault diagnosis. Appl. Acoust. 2025, 231, 110442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Tong, L.; Xu, X.; Cai, J.; Peng, X.; Omar, M.; Bashir, A.K.; Wang, W. Robust Fault Diagnosis of Drilling Machinery Under Complex Working Conditions Based on Carbon Intelligent Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 34663–34678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, M.; Siddique, M.F.; Kim, J.-M. Burst-informed acoustic emission framework for explainable failure diagnosis in milling machines. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 185, 110373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.; Neto, P. Classification of assembly tasks combining multiple primitive actions using Transformers and xLSTMs. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.18012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhang, D.; Song, Y.; Sun, X. Inverse design and spatial optimization of SFAM via deep learning. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 306, 110855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, J.; Ma, J.; Chen, Z. A lightweight transformer based on feature fusion and global–local parallel stacked self-activation unit for bearing fault diagnosis. Measurement 2024, 236, 115068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Pöppel, K.; Spanring, M.; Auer, A.; Prudnikova, O.; Kopp, M.; Klambauer, G.; Brandstetter, J.; Hochreiter, S. xLSTM: Extended long short-term memory. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.04517. [Google Scholar]

- Jalayer, M.; Orsenigo, C.; Vercellis, C. Fault detection and diagnosis for rotating machinery: A model based on convolutional LSTM, Fast Fourier and continuous wavelet transforms. Comput. Ind. 2021, 125, 103378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Shi, J.; Hou, X.; Liu, J. Adaptive Batch Normalization for practical domain adaptation. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 80, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Sun, J. Activate or not: Learning customized activation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 8032–8042. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; He, C.; Lu, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, L. Fault diagnosis for small samples based on attention mechanism. Measurement 2022, 187, 110242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-J.; Liao, A.-H.; Hu, D.-Y.; Shi, W.; Zheng, S.-B. Multi-scale convolutional network with channel attention mechanism for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Measurement 2022, 203, 111935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Module | Model | Main Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Hydraulic motor | A6VM80HD2/63W-VAB020B-0400 | Engine power: 132 kW/2500 rpm Maximum RPM: 3000 |

| Acceleration sensor | AI002 | Sensitivity: 1.938 mV/ms−2 |

| Data acquisition instrument | AVANT MI-7016 | Number of channels: 16 Maximum sampling frequency: 192 kHz Input voltage range: ±10 VPEAK |

| Gearbox | YDX-3 | Rated torque: 500 N·m Maximum Torque: 4200 N·m |

| Magnetic particle brake | CZF-200 | Rated torque: 2000 N·m Excitation current: 3A |

| Motor Speed (rpm) | Load (N·m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 400 | 1200 | |

| 590 | S5L0 | S5L4 | S5L12 |

| 1190 | S11L0 | S11L4 | S11L12 |

| Fault Type Number | Collection Frequency/Hz | Speed/rpm | Load/N·m | Fault Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6000 | 590/1180 | 0/400/1200 | Pitting of driving gear |

| 1 | 6000 | 590/1180 | 0/400/1200 | Fatigue fracture of the driving gear |

| 2 | 6000 | 590/1180 | 0/400/1200 | Wear fault of the driven gear |

| 3 | 6000 | 590/1180 | 0/400/1200 | Compound fault |

| 4 | 6000 | 590/1180 | 0/400/1200 | Normal |

| Dataset | Working Condition |

|---|---|

| D1 | 590 rpm and 0 N |

| D2 | 590 rpm and 0, 400 N |

| D3 | 590, 1180 rpm and 0, 400 N |

| D4 | 590, 1180 rpm and 0, 400, 1200 N |

| Layer Type | Kernel Size /Stride/Padding | Activation | AdaBN | Input | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conv1d | 18/2/0 | Meta-ACON | Yes | (128,1,1024) | (128,50,504) |

| Conv1d | 10/2/0 | Meta-ACON | Yes | (128,50,504) | (128,30,248) |

| MaxPool1d | 2/2/0 | / | No | (128,30,248) | (128,30,124) |

| Conv1d | 6/1/0 | Meta-ACON | Yes | (128,1,1024) | (128,50,1019) |

| Conv1d | 6/1/0 | Meta-ACON | Yes | (128,50,1019) | (128,40,1014) |

| MaxPool1d | 2/2/0 | / | No | (128,40,1014) | (128,40,507) |

| Conv1d | 6/1/0 | Meta-ACON | Yes | (128,40,507) | (128,30,502) |

| Conv1d | 6/2/0 | Meta-ACON | Yes | (128,30,502) | (128,30,249) |

| MaxPool1d | 2/2/0 | / | No | (128,30,249) | (128,30,124) |

| Multiplicative Fusion | / | / | / | (128,30,124) × 2 | (128,30,124) |

| CoordAtt | / | / | / | (128,30,124) | (128,30,124) |

| xLSTM | / | / | / | (128,124,30) | (128,124,64) |

| PatchEmbedding | / | / | / | (128,1,1024) | (128,1,16,124) |

| Transformer Block × 3 | / | GELU | / | (128,1,17,124) | (128,1,17,124) |

| Concatenate | / | / | / | [(128,30,124), (128,1,124)] | (128,31,124) |

| AdaptiveAvgPool1d | / | / | / | (128,31,124) | (128,31) |

| Linear (FC) | / | SoftMax | / | (128,31) | (128,5) |

| Experimental Software and Hardware Environment Configuration | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Central Processing Unit (CPU) | Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-13490F 2.50 GHz |

| Memory (RAM) | DDR5 5600 16 G RAM |

| Graphics card (GPU) | NVIDIA GeForce GTX2080 ti |

| Operating system | Microsoft Windows 11 ×64 |

| Development environment (RAM) | Python 3.8, Pytorch 1.11.0 |

| T-DCAx | DCA-BiGRU | CA-MCNN | Transformer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average accuracy (%) | 99.42 | 96.11 | 94.81 | 89.53 |

| Standard deviation (%) | 0.525 | 1.131 | 1.273 | 2.121 |

| Average training time(s) | 631 | 837 | 653 | 423 |

| Minimum epoch at model convergence | 9 | 11 | 14 | 23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, X.; Du, Y.; Gao, P.; Tang, X.; Liu, J.; Ma, H. Fault Diagnosis of Core Drilling Rig Gearbox Based on Transformer and DCA-xLSTM. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12858. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412858

Wu X, Du Y, Gao P, Tang X, Liu J, Ma H. Fault Diagnosis of Core Drilling Rig Gearbox Based on Transformer and DCA-xLSTM. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12858. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412858

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Xiaolong, Yaosen Du, Pengju Gao, Xiaoren Tang, Jianxun Liu, and Hanchen Ma. 2025. "Fault Diagnosis of Core Drilling Rig Gearbox Based on Transformer and DCA-xLSTM" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12858. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412858

APA StyleWu, X., Du, Y., Gao, P., Tang, X., Liu, J., & Ma, H. (2025). Fault Diagnosis of Core Drilling Rig Gearbox Based on Transformer and DCA-xLSTM. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12858. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412858