Development of a Monitoring Method for Powered Roof Supports

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction and Specification of Pressure, Inclination, and Position Sensors

- Application: Measurement of hydraulic pressure in cylinders and control valves of roof support sections.

- Type: Strain gauge pressure transducer (Center of Hydraulics DOH Ltd., Piekary Śląskie, Poland)

- Measuring Range: 0–60 MPa (typically up to 40 MPa for operational use)

- Connection: STECKO DN-10

- Communication: ISM 2.4 GHz

- Operating Temperature Range: –10 to 40 °C

- Weight (with battery): 690 g

- Accuracy: ±0.25% of full scale

- Output Signal: RS-485 (digital)

- Enclosure Protection: IP67; certified for operation in methane- and coal-dust-hazardous areas (ATEX certified)

- Application: Measurement of inclination angle and orientation of the roof support section during operation.

- Type: MEMS inclinometers or gyroscopic sensors (Center of Hydraulics DOH Ltd., Piekary Śląskie, Poland)

- Measuring Range: ±90°

- Accuracy: 0.1° or better

- Additional Features: Temperature compensation, vibration damping, integration capability with section control system.

2.2. Determination of the Calculation Method

- Λ—inclination angle, [°]

- ay—gravitational acceleration in the Y-axis, [m/s2]

- ax—gravitational acceleration in the X-axis, [m/s2]

- az—gravitational acceleration in the Z-axis, [m/s2]

- —measured height (h1, h2, h3) [m]

- —length of the section element, [m]

- —angle of the given section element

- Hc—height total, [m]

- h1—height determined by the length of the canopy and the angle, [m]

- h2—height determined by the length of the shield support and the angle, [m]

- h3—height determined by the length of the lemniscates and the angle, [m]

3. Results

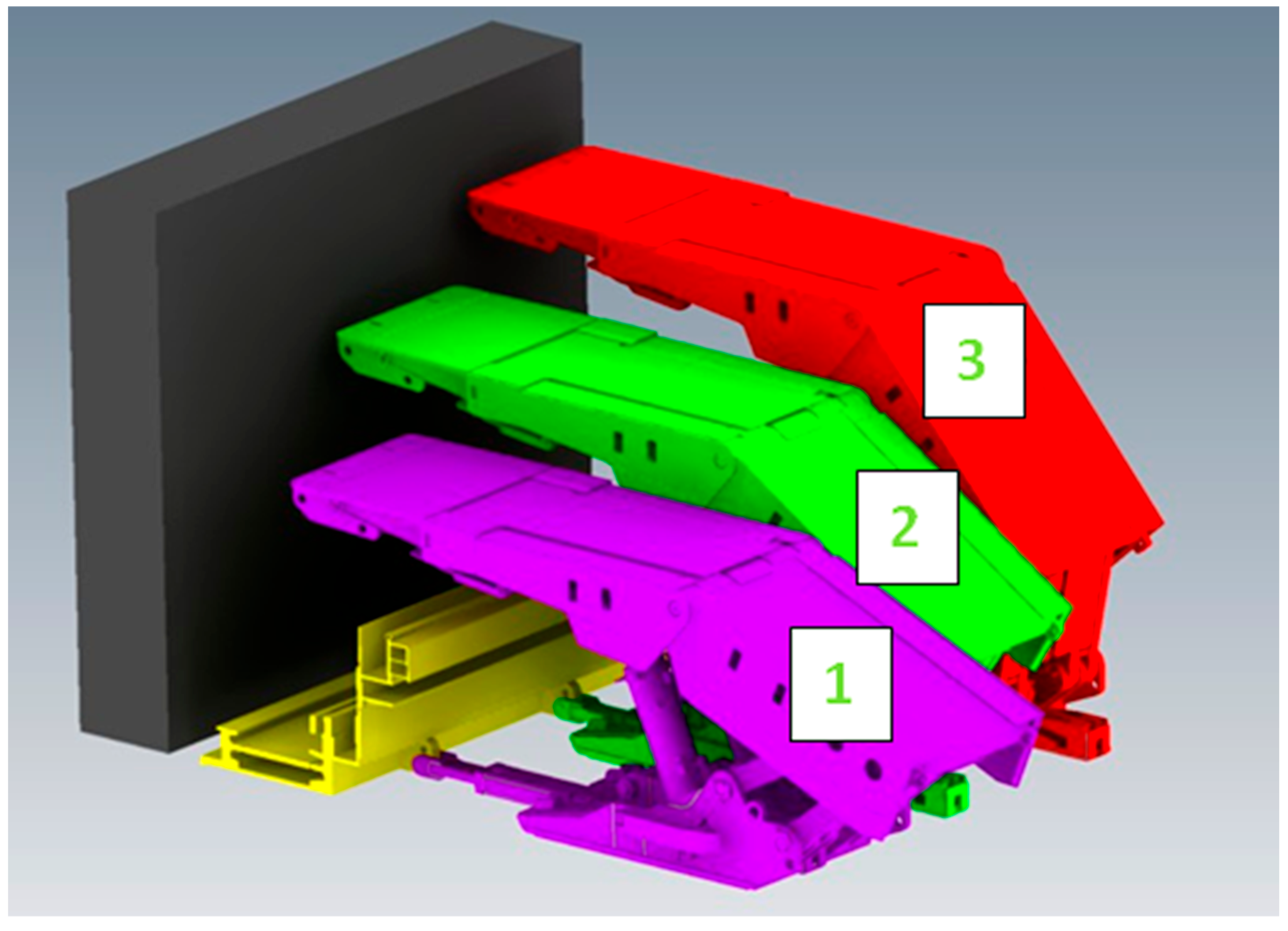

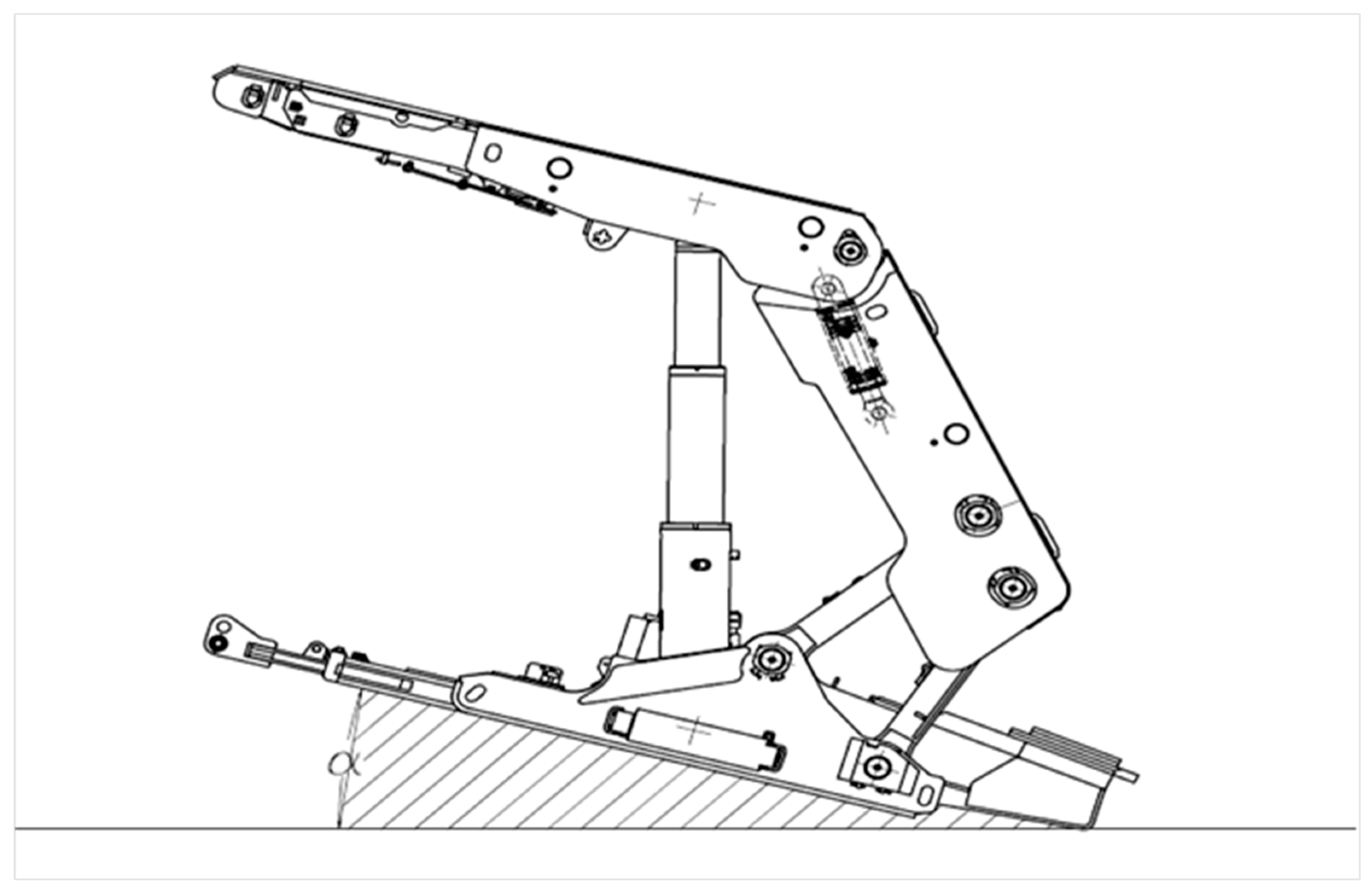

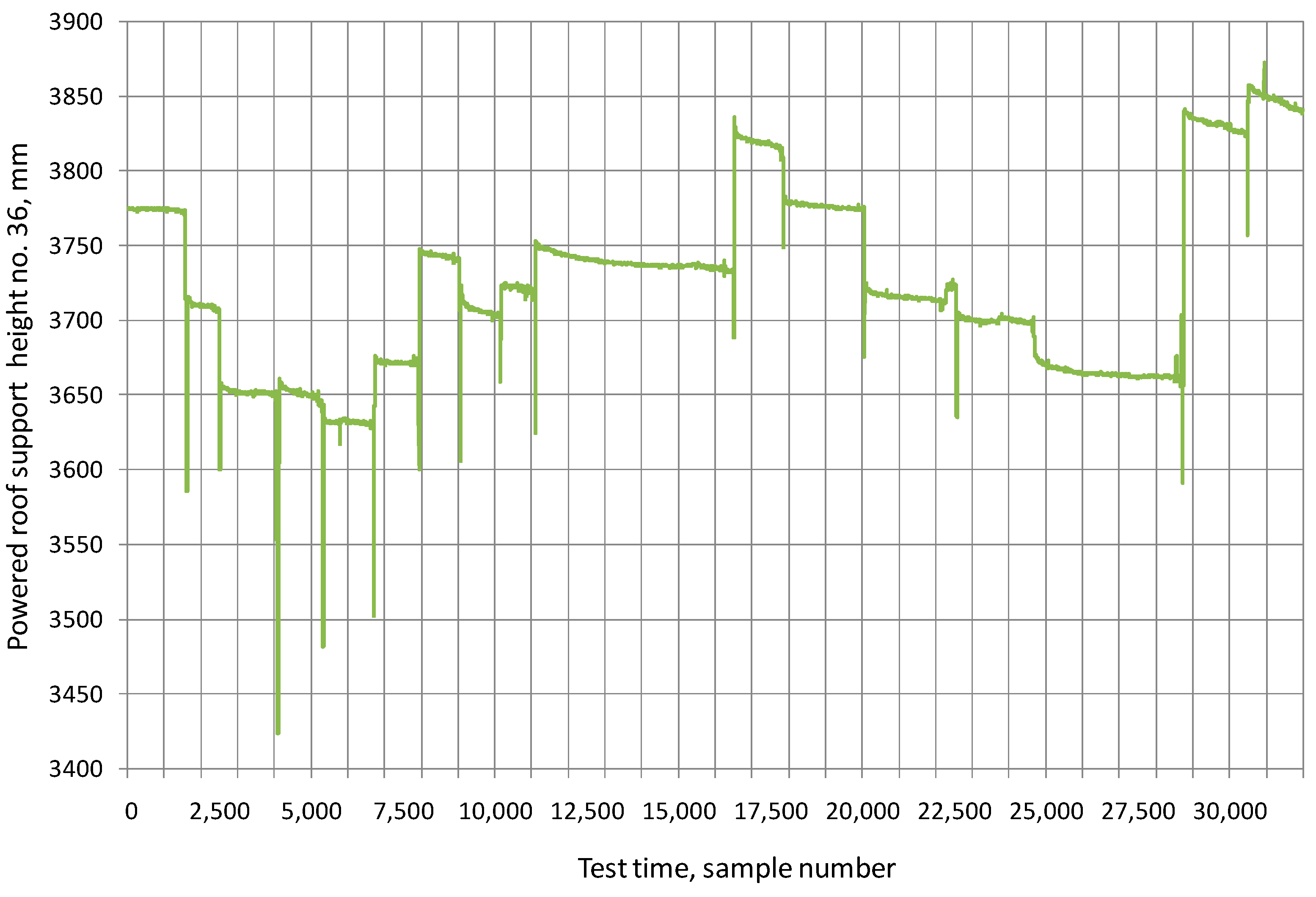

3.1. Bench Tests

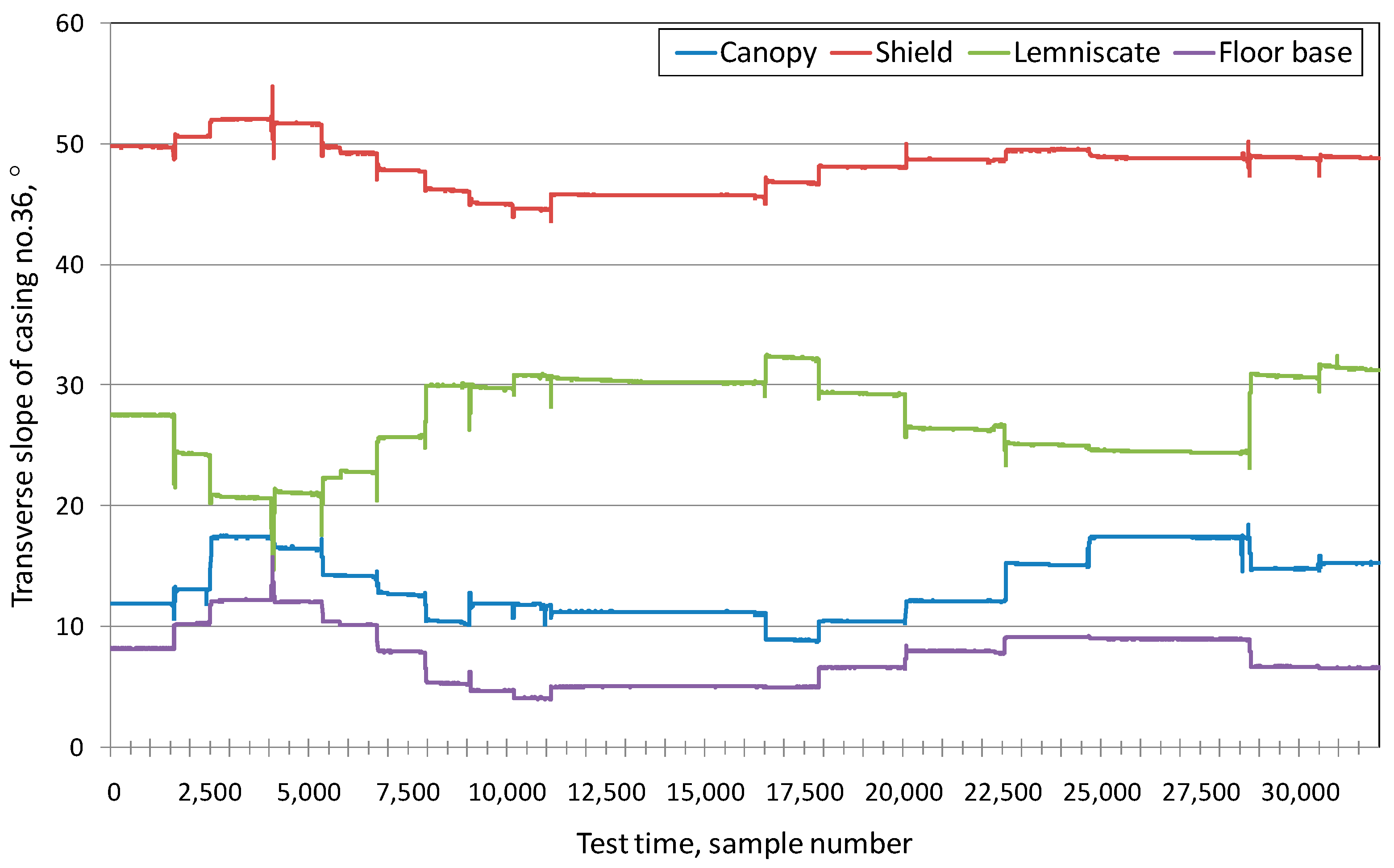

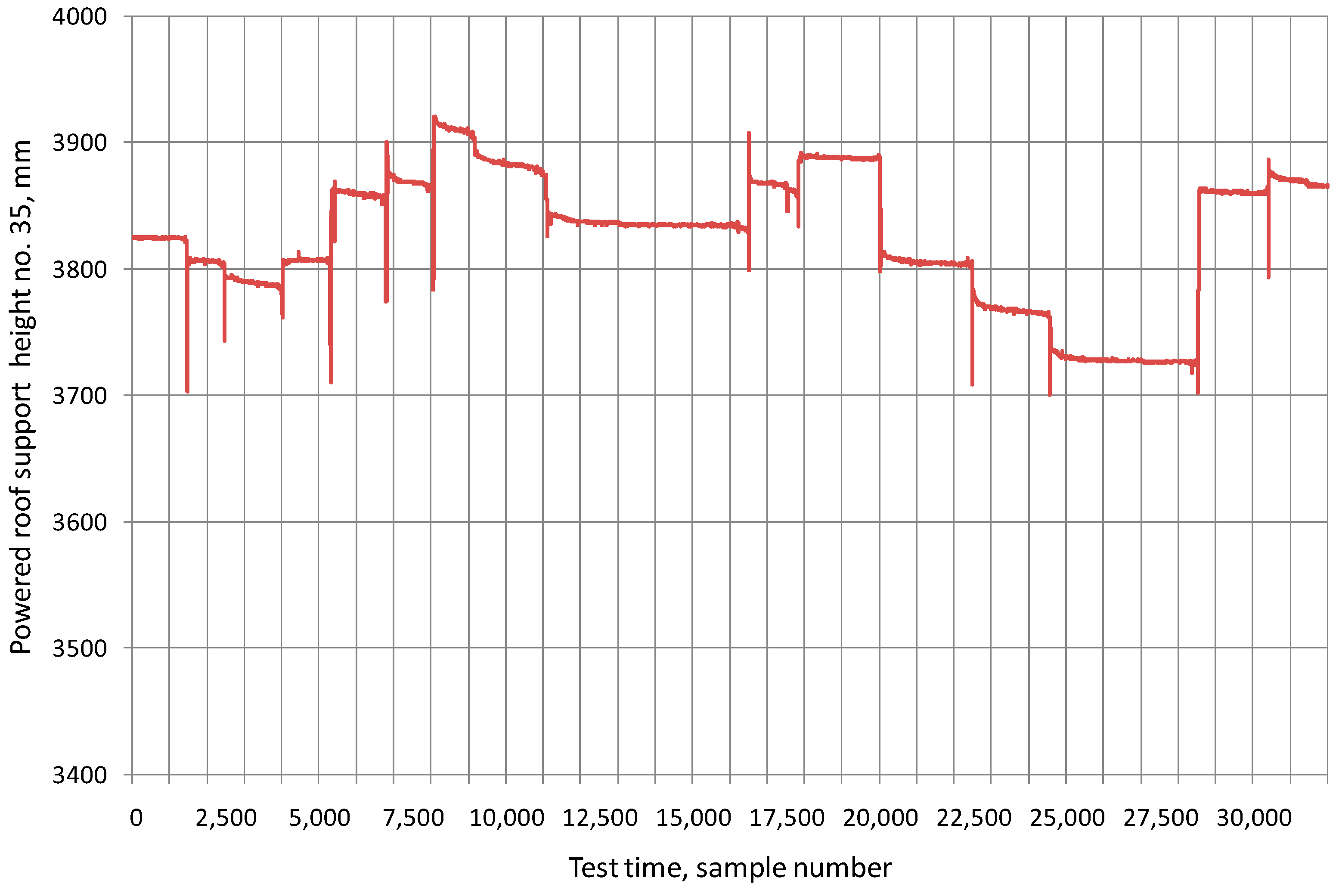

3.2. Tests Under Real Conditions

4. Discussion

- The sensors constituting the measuring recording system should be located on the canopy, the floor base, the lemniscates, and the shield support.

- Innovative mounting brackets should be used to mount the sensors.

- The mounting locations were determined, taking into account the areas most exposed to external forces under actual conditions.

- The sensors are located for easy access during service maintenance related to a failure or replacement of the power supply batteries.

- The installation of the sensors took into account the impact of the structural elements on the quality of the measurement system’s communication.

- The sensors are visible to the crew for significantly improved visualization of light signals indicating the operating status of the support.

- -

- Environmental working conditions—High temperature, humidity, dust, and the presence of vibrations in the excavation may negatively affect sensors and transmission cables, causing signal interference or failure of measuring devices.

- -

- Limited resistance of sensors to mechanical damage—In longwall operation conditions, system components are exposed to vibrations, impacts from rock fragments, and contact with structural elements, which may lead to their premature wear.

- -

- Data transmission and integration issues—In underground environments, ensuring stable wired or wireless communication is difficult, especially over longer distances. Integrating systems from different manufacturers can also be problematic due to inconsistent communication protocol standards.

- -

- The complexity of data interpretation—Analyzing the results requires specialized engineering knowledge and understanding the dynamics of the support section. In many cases, data filtering and pre-processing are necessary to eliminate errors resulting from measurement noise.

- -

- Implementation and maintenance costs—Advanced monitoring systems require significant capital expenditure, both at the installation stage and for subsequent maintenance, which may limit their use in smaller mining plants.

- -

- Assessment of the technical condition of the section—Ongoing measurement of parameters, such as pressure in cylinders, displacements, and inclination or load on the structure, enables early detection of irregularities and prevention of failures.

- -

- Increased crew safety—The system allows for the identification of potentially dangerous situations, such as excessive section deflection, loss of contact with the ceiling, or overloading of structural elements, enabling immediate response by operators.

- -

- Optimization of operating parameters—Real-time analysis of measurement data allows for the adjustment of support forces, travel speed, and synchronization of the operation of individual sections, which leads to improved stability and efficiency of the longwall system.

- -

- Supporting decision-making and diagnostic processes—Archiving monitoring data enables the creation of forecasting models, assessment of load trends, and identification of areas with an increased risk of rock mass deformation.

- -

- Cooperation with superior systems—Modern monitoring systems can be integrated with comprehensive longwall control systems, which allows for the automation of some operational processes and remote control of selected support functions.

5. Conclusions

- The analyzed spatial model of the powered support required the use of additional structural elements and the addition of material properties to increase strength. These factors were refined using numerical calculations. The locations most exposed to possible damage resulting from exceeding the permissible stress values have been determined. The conducted model tests (strength tests) indicated structural changes in order to achieve safety and quality requirements while reducing production costs, as well as identifying preliminary installation locations for installing sensors to monitor the powered roof parameters.

- The powered support monitoring system is a tool for diagnosing and analyzing the operation of the support sections. The research made it possible to determine the height, as well as the transverse and longitudinal inclination of the support on the bench test, based on the obtained geometric parameters and the operating angles of the basic support elements.

- Analysis based on model and bench tests showed no collision of the roof support elements with the system sensors. The measuring system was installed on the canopy, the floor base, the shield support, and the lemniscate.

- The prepared measuring system allows for quick identification of any type of deviations in the setting of each support section. Above all, obtaining quick information about irregularities in the section setting will limit the further process of deterioration of its cooperation with the rock mass and other machines in the complex.

- The conducted research determined the methodology, the operating procedure, and the installation of the measuring and recording system. This information constitutes guidelines for the development of the measuring and recording system. The obtained information about the geometry of the support section should allow the assessment of its operation and allow determining the relationship between this state and phenomena occurring in the rock mass.

- The practical use of the system, provided that the sensors are denser in the longwall excavation and innovative mounting brackets are used, leads to significant changes in the way mining is carried out, reducing downtime and increasing the safety of the crew.

- -

- Further improve the design methods for the mechanical components of powered support sections to enhance their ergonomics with a view to introducing remote control of their operation;

- -

- Conduct tests under real conditions in order to limit the number of sensors used to determine the geometric parameters of the roof support;

- -

- Improve the system in terms of its cooperation with other machines of the longwall complex;

- -

- Introduce artificial intelligence solutions for self-learning of the system in order to react and warn the user about changes occurring in the rock mass;

- -

- Improve the system in terms of determining the limit values of recorded system parameters that may adversely affect the operation of the roof support and the entire longwall complex in terms of safety;

- -

- Improve the quality of the sensor power supply so that there is no need to replace the battery under surface conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zimroz, P.; Trybała, P.; Wróblewski, A.; Góralczyk, M.; Szrek, J.; Wójcik, A.; Zimroz, R. Application of UAV in Search and Rescue Actions in Underground Mine-A Specific Sound Detection in Noisy Acoustic Signal. Energies 2021, 14, 3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, Y. Roof pre-blasting to prevent support crushing and water inrush accidents. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2012, 22, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyalich, G.; Buyalich, K.; Byakov, M. Factors Determining the Size of Sealing Clearance in Hydraulic Legs of Powered Supports. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 21, 3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalec, W.; Suchorab, N.; Konieczna-Fuławka, M.; Król, R. Specific energy consumption of a belt conveyor system in a continuous surface mine. Energies 2020, 13, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, A.K.; Mishra, A.K.; Singh, R. Underground mining of thick coal seams. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2015, 25, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaluk, O.; Slabyi, O.; Vekeryk, V.; Velychkovych, A.; Ropyak, L.; Lozynskyi, V. A Technology of Hydrocarbon Fluid Production Intensification by Productive Stratum Drainage Zone Reaming. Energies 2021, 14, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwica, K.; Stopka, G.; Kalita, M.; Bałaga, D.; Siegmund, M. Impact of Geometry of Toothed Segments of the Innovative KOMTRACK Longwall Shearer Haulage System on Load and Slip during the Travel of a Track Wheel. Energies 2021, 14, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesiek, A.; Zimroz, R.; Śliwiński, P.; Gomolla, N.; Wyłomańska, A. A Method for Structure Breaking Point Detection in Engine Oil Pressure Data. Energies 2021, 14, 5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebda-Sobkowicz, J.; Gola, S.; Zimroz, R.; Wyłomańska, A. Identification and Statistical Analysis of Impulse-Like Patterns of Carbon Monoxide Variation in Deep Underground Mines Associated with the Blasting Procedure. Sensors 2019, 19, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.S.; Feng, D.; Cheng, J.; Yang, L. Automation in U.S. longwall coal mining: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2019, 29, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauze, K.; Mucha, K.; Wydro, T.; Pieczora, E. Functional and Operational Requirements to Be Fulfilled by Conical Picks Regarding Their Wear Rate and Investment Costs. Energies 2021, 14, 3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uth, F.; Polnik, B.; Kurpiel, W.; Baltes, R.; Kriegsch, P.; Clause, E. An innovate person detection system based on thermal imaging cameras dedicatefor underground belt conveyors. Min. Sci. 2019, 26, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Ren, T.; Wynne, P.; Wan, Z.; Zhaoyang, M.; Wang, Z. A comparative study of dust control practices in Chinese and Australian longwall coal mines. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2016, 25, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prostański, D. Empirical Models of Zones Protecting Against Coal Dust Explosion. Arch. Min. Sci. 2017, 62, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, J.C.; Reid, D.C.; Dunn, M.T.; Hainsworth, D.W. Longwall automation: Delivering enabling technology to achieve safer and more productive underground mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2015, 25, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortnowski, P.; Gładysiewicz, L.; Król, R.; Ozdoba, M. Energy Efficiency Analysis of Copper Ore Ball Mill Drive Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, P.J. Comminution of Copper Ores with the Use of a High-Pressure Water Jet. Energies 2020, 13, 6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayrutdinov, M.M.; Golik, V.I.; Aleksakhin, A.V.; Trushina, E.V.; Lazareva, N.V.; Aleksakhina, Y.V. Proposal of an Algorithm for Choice of a Development System for Operational and Environmental Safety in Mining. Resources 2022, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalec, W.; Błażej, R.; Konieczna, M.; Król, R. Laboratory Tests on e-pellets effectiveness for ore tracking. Min. Sci. 2018, 25, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janus, J.; Krawczyk, J. Measurement and Simulation of Flow in a Section of a Mine Gallery. Energies 2021, 14, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiul, K.; Khudyakov, A.; Vashchenko, S.; Krot, P.V.; Solodka, N. The experimental study of compaction parameters and elastic after-effect of fine fraction raw materials. Min. Sci. 2020, 27, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Spearing, S.; Ju, F.; Jessu, K.V.; Wang, Z.; Ning, P. Control Effects of Five Common Solid Waste Backfilling Materials on In Situ Strata of Gob. Energies 2019, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajs, J.; Trybała, P.; Górniak-Zimroz, J.; Krupa-Kurzynowska, J.; Kasza, D. Modern Solution for Fast and Accurate Inventorization of Open-Pit Mines by the Active Remote Sensing Technique-Case Study of Mikoszów Granite Mine (Lower Silesia, SW Poland). Energies 2021, 14, 6853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajwa, S.; Janoszek, T.; Prusek, S. Influence of canopy ratio of powered roof support on longwall working stability—A case study. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2019, 29, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juganda, A.; Strebinger, C.; Brune, J.F.; Bogin, G.E. Discrete modeling of a longwall coal mine gob for CFD simulation. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świątek, J.; Janoszek, T.; Cichy, T.; Stoiński, K. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations for Investigation of the Damage Causes in Safety Elements of Powered Roof Supports-A Case Study. Energies 2021, 14, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adach-Pawelus, K.; Pawelus, D. Influence of Driving Direction on the Stability of a Group of Headings Located in a Field of High Horizontal Stresses in the Polish Underground Copper Mines. Energies 2021, 14, 5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, K. Influence of cutting angle on mechanical properties of rock cutting by conical pick based on finite element analysis. J. Min. Sci. 2021, 28, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doległo, L.; Stoiński, K.; Gil, J. Analityczna ocena wydajności objętościowej układu hydraulicznego stojaka zmechanizowanej obudowy ścianowej. Masz. Górnicze 2009, 4, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jasiulek, D.; Skóra, M.; Jagoda, J.; Jura, J.; Rogala-Rojek, J.; Hetmańczyk, M. Monitoring the Geometry of Powered Roof Supports—Determination of Measurement Accuracy. Energies 2023, 16, 7710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodecki, J.; Góralczyk, M.; Krot, P.; Ziętek, B.; Szrek, J.; Worsa-Kozak, M.; Zimroz, R.; Śliwiński, P.; Czajkowski, A. Process Monitoring in Heavy Duty Drilling Rigs-Data Acquisition System and Cycle Identification Algorithms. Energies 2020, 13, 6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardzinski, P.; Jurdziak, L.; Kawalec, W.; Król, R. Copper ore quality tracking in a belt conveyor system using simulation tools. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patyk, M.; Bodziony, P.; Krysa, Z. A Multiple Criteria Decision Making Method to Weight the Sustainability Criteria of Equipment Selection for Surface Mining. Energies 2021, 14, 3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzop, K.; Szurgacz, D. Tests Result of the Prototype Monitoring System for the Operating Parameters of the Powered Roof Support in Real Conditions. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2024, 34, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szurgacz, D.; Trzop, K.; Spearing, A.J.S.; Pokorny, J.; Zhironkin, S. Determining the pressure increase in the hydraulic cylinders of powered roof support based on actual measurements. Acta Montan. Slovac 2022, 27, 876. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Hu, Y.; Liu, S.; Yin, J.; Fan, K.; Yi, L. An AGCRN Algorithm for Pressure Prediction in an Ultra-Long Mining Face in a Medium-Thick Coal Seam in the Northern Shaanxi Area, China. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N. Research on Hydraulic Support Attitude Monitoring Method Based on Electro-Hydraulic Control System of Fully Mechanized Mining Face. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, G. Real-Time Monitoring of Underground Miners’ Status Based on Mine IoT System. Sensors 2024, 24, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Underground Mine Safety and Health: A Hybrid MEREC-CoCoSo Framework for Sensor Selection in Underground Mining. Sensors 2024, 24, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B. Research on an Intelligent Mining Complete System of a Fully Mechanized Coal Mining Face in Thin Coal Seam. Sensors 2023, 23, 9034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruczek, P.; Gomolla, N.; Hebda-Sobkowicz, J.; Michalak, A.; Śliwiński, P.; Wodecki, J.; Stefaniak, P.; Wyłomańska, A.; Zimroz, R. Predictive Maintenance of Mining Machines Using Advanced Data Analysis System Based on the Cloud Technology. In Proceedings of the 27th International Symposium on Mine Planning and Equipment Selection-MPES 2018; Widzyk-Capehart, E., Hekmat, A., Singhal, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ma, L.; Guo, J.; Yang, P. Support-surrounding rock relationship and top-coal movement laws in large dip angle fully-mechanized caving face. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 533–539. [Google Scholar]

- Ralston, J.C.; Hargrave, C.O.; Dunn, M.T. Longwall automation: Trends, challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2017, 27, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajda, M.; Błażej, R.; Hardygóra, M. Optimizing splice geometry in multiply conveyor belts with respect to stress in adhesive bonds. Min. Sci. 2018, 25, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gładysiewicz, L.; Król, R.; Kisielewski, W.; Kaszuba, D. Experimental determination of belt conveyors artificial friction coefficient. Acta Mont. 2017, 22, 206–214. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak, D.; Hardygóra, M. Method for laboratory testing rubber penetration of steel cords in conveyor belts. Min. Sci. 2020, 27, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajda, M.; Hardygóra, M. Analysis of Reasons for Reduced Strength of Multiply Conveyor Belt Splices. Energies 2021, 14, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buevich, V.V.; Gabov, V.V.; Zadkov, D.A.; Vasileva, P.A. Adaptation of the mechanized roof support to changeable rock pressure. Eurasian Min. 2015, 2, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babyr, N.V.; Korolev, A.I.; Neupokoeva, T.V. Enhancement of powered cleaning equipment with the view of mining and geological conditions. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 194, 032004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klishin, V.I.; Klishin, S.V. Coal Extraction from Thick Flat and Steep Beds. J. Min. Sci. 2010, 46, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypkowski, K.; Korzeniowski, W.; Zagórski, K.; Zagórska, A. Modified Rock Bolt Support for Mining Method with Controlled Roof Bending. Energies 2020, 13, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jixiong, Z.; Spearing, A.J.S.; Xiexing, M.; Shuai, G.; Qiang, S. Green coal mining technique integrating mining-dressing-gas draining-backfilling-mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2017, 27, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gabov, V.V.; Zadkov, D.A.; Stebnev, A.V. Evaluation of structure and variables within performance rating of hydraulically powered roof sup-port legs with smooth roof control. Eurasian Min. 2016, 2, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Systematic principles of surrounding rock control in longwall mining within thick coal seams. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2019, 29, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Shao, Z.; Gao, Y. Theoretical analysis of support stability in large dip angle coal seam mined with fully-mechanized top coal caving. Min. Sci. 2020, 27, 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Babyr, N.; Babyr, K. To improve the contact adaptability of mechanical roof support. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 266, 03015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabov, V.V.; Zadkov, D.A.; Babyr, N.V.; Xie, F. Nonimpact rock pressure regulation with energy recovery into the hydraulic system of the longwall powered support. Eurasian Min. 2021, 36, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhang, D.; Gong, S.; Zhou, K.; Xi, C.; He, M.; Li, T. Dynamic impact experiment and response characteristics analysis for 1:2 reduced-scale model of hydraulic support. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2021, 31, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyalich, G.; Byakov, M.; Buyalich, K.; Shtenin, E. Development of Powered Support Hydraulic Legs with Improved Performance. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 105, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frith, R.C. A holistic examination of the load rating design of longwall shields after more than half a century of mechanised longwall mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2015, 26, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Fan, Y. Fatigue Behavior of a Box-Type Welded Structure of Hydraulic Support Used in Coal Mine. Materials 2015, 8, 6609–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzki, P.; Krot, P. Dynamics control of powered hydraulic roof supports in the underground longwall mining complex. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 942, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Xu, P.; Meng, Z.; Ma, C.; Lei, X. Posture and Dynamics Analysis of Hydraulic Support with Joint Clearance under Impact Load. Machines 2023, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gao, K.; Zeng, Q.; Meng, F.; Cheng, J. Research on Intelligent Control System of Hydraulic Support Based on Position and Posture Detection. Machines 2023, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyko, J. General Mechanics; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; pp. 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Analog Devices. Using an Accelerometer for Inclination Sensing; AN-1057 Aplication Note; Analog Devices, Inc.: Wilmington, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczak, S. Tilt measurements realised by means of MEMS accelerometers. Pomiary Autom. Robot. 2008, 12, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szurgacz, D.; Trzop, K.; Bazan, Ł.; Brodny, J.; Krysa, Z. Development of a Monitoring Method for Powered Roof Supports. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12828. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312828

Szurgacz D, Trzop K, Bazan Ł, Brodny J, Krysa Z. Development of a Monitoring Method for Powered Roof Supports. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12828. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312828

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzurgacz, Dawid, Konrad Trzop, Łukasz Bazan, Jarosław Brodny, and Zbigniew Krysa. 2025. "Development of a Monitoring Method for Powered Roof Supports" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12828. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312828

APA StyleSzurgacz, D., Trzop, K., Bazan, Ł., Brodny, J., & Krysa, Z. (2025). Development of a Monitoring Method for Powered Roof Supports. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12828. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312828