Construction of an Intelligent Risk Identification System for Highway Flood Damage Based on Multimodal Large Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Core Technical Methodologies

2.1. Multimodal Large Models and Fine-Tuning Principles

2.2. Prompt Engineering

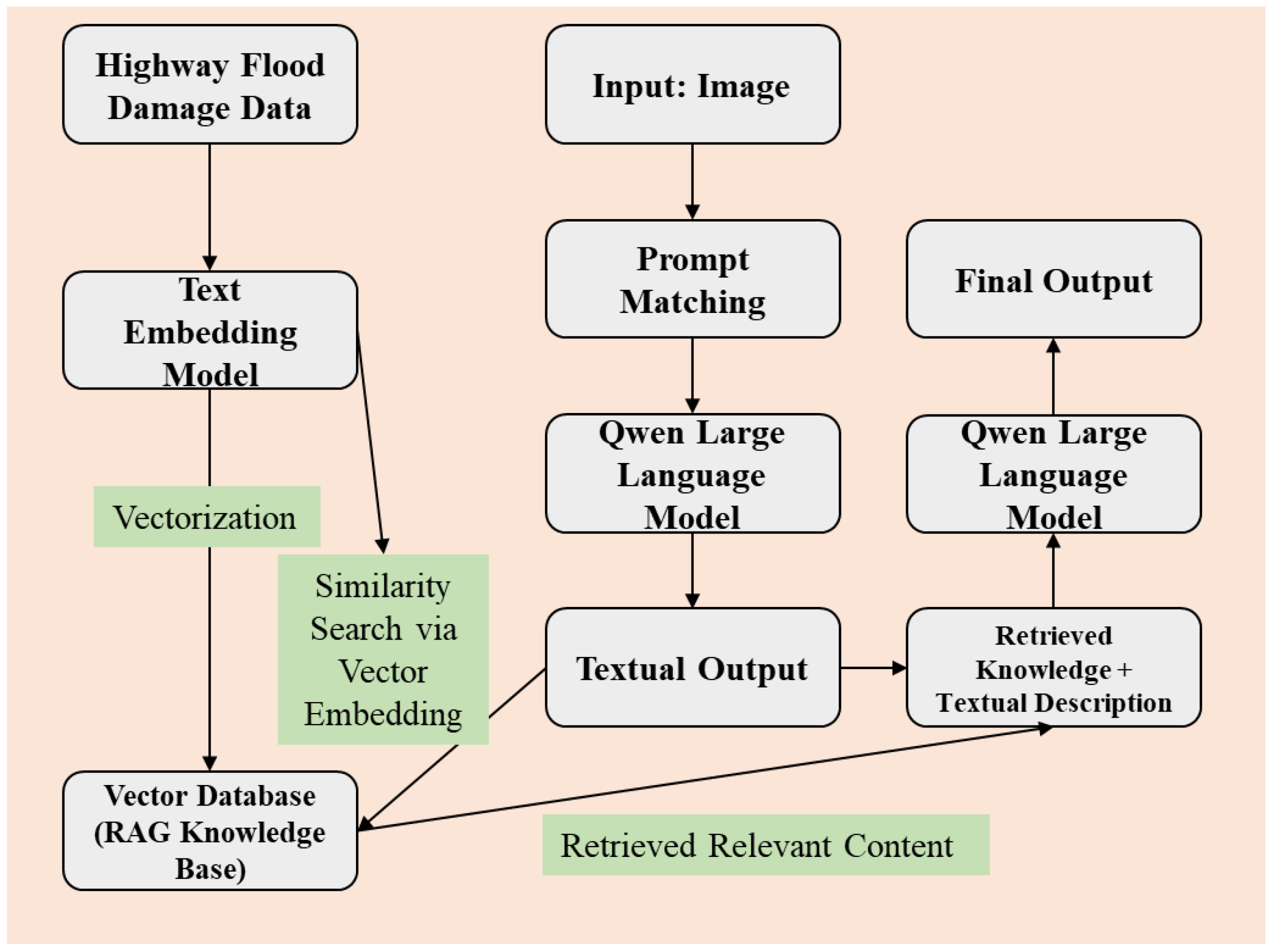

2.3. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

3. Intelligent Identification System for Highway Flood Damage and Related Distresses

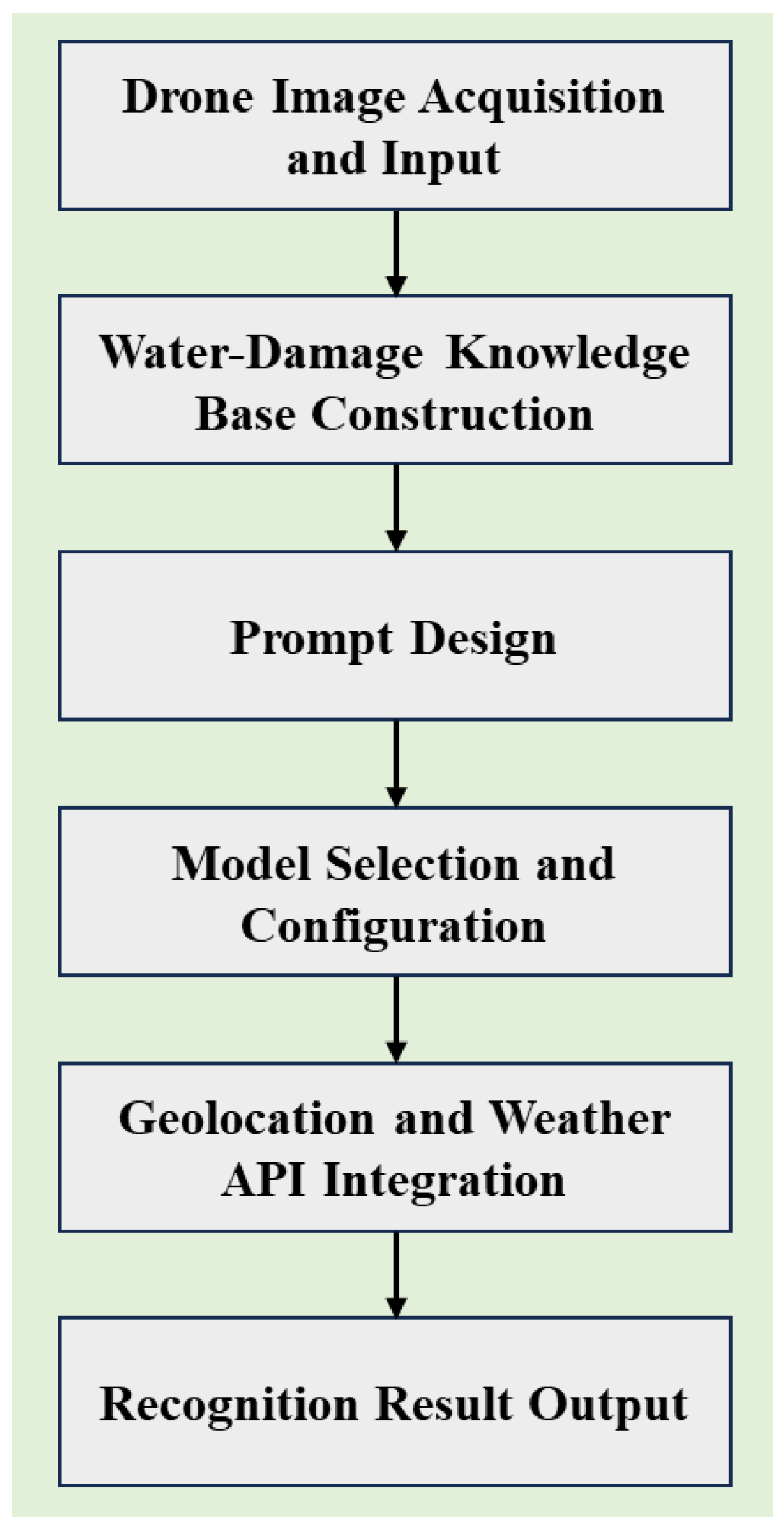

3.1. Workflow

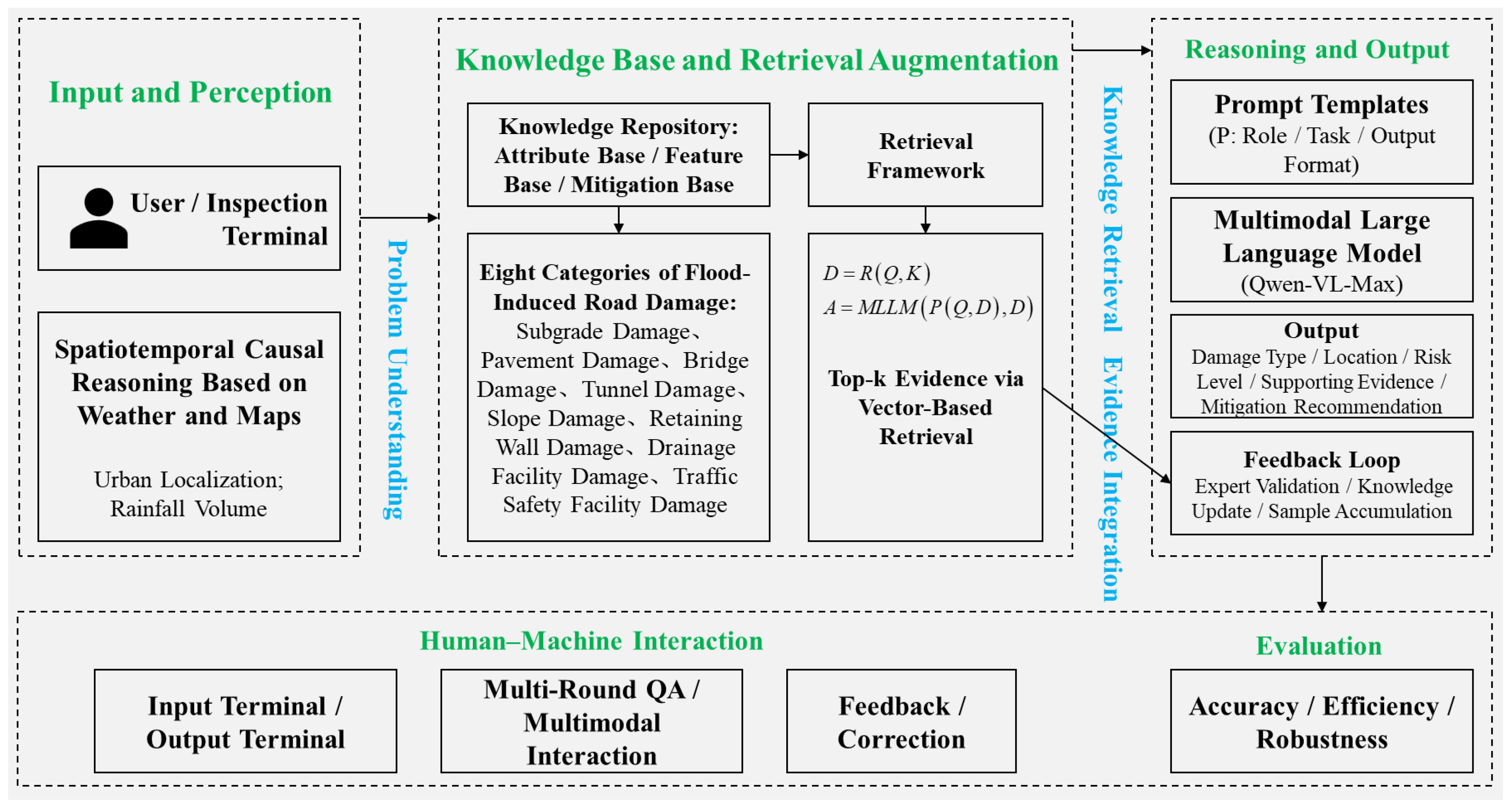

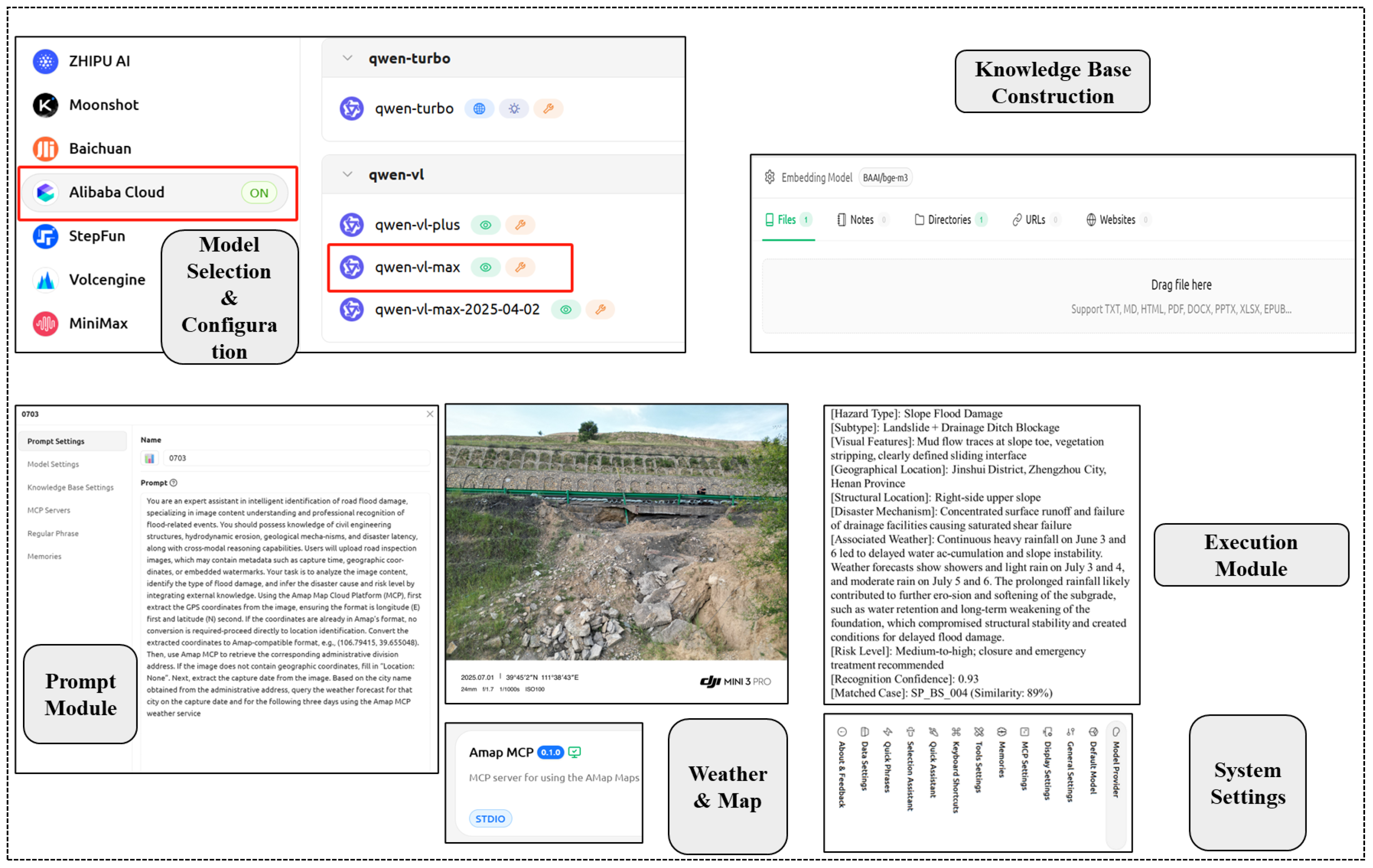

3.2. System Architecture

3.3. System Implementation

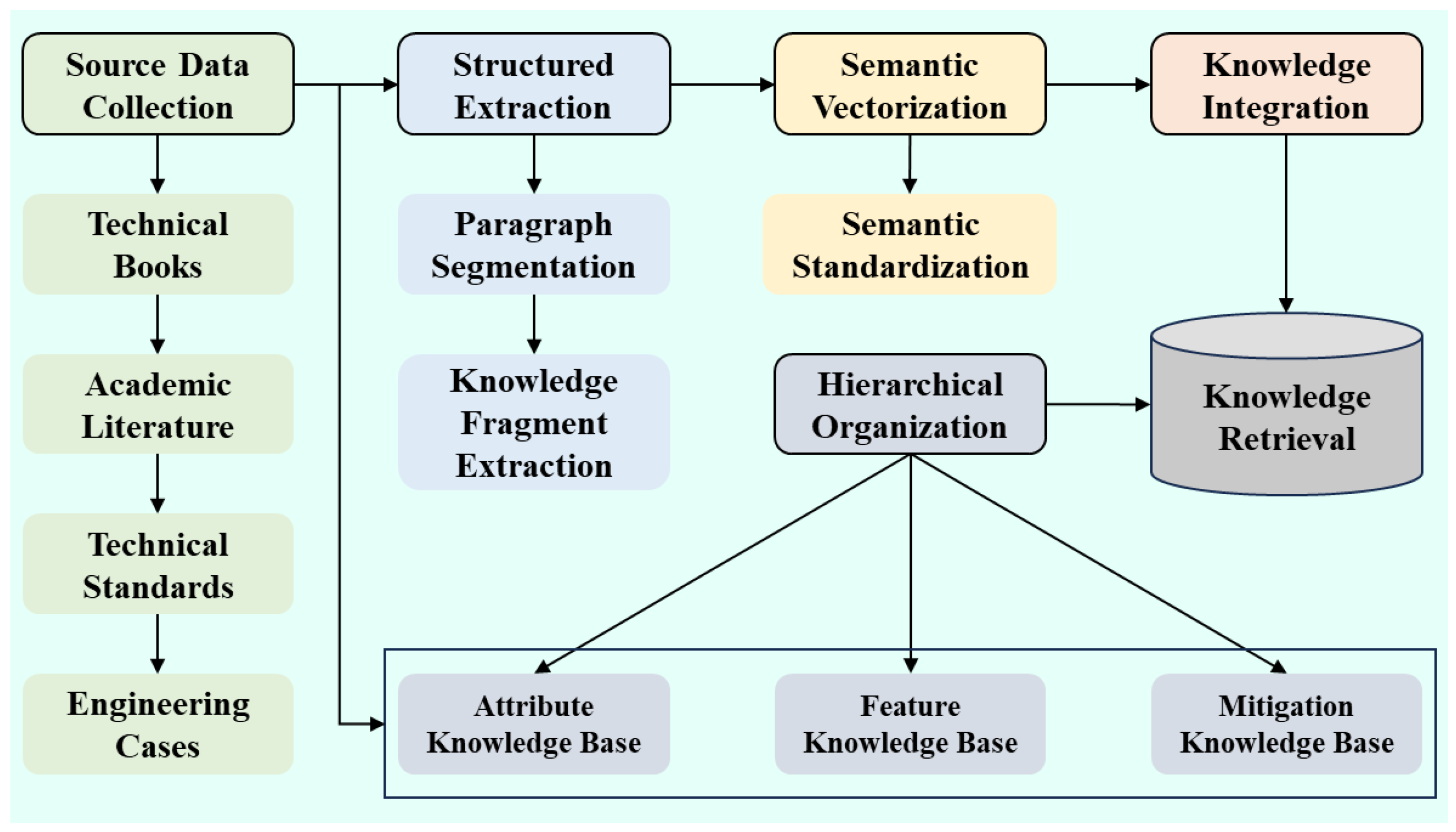

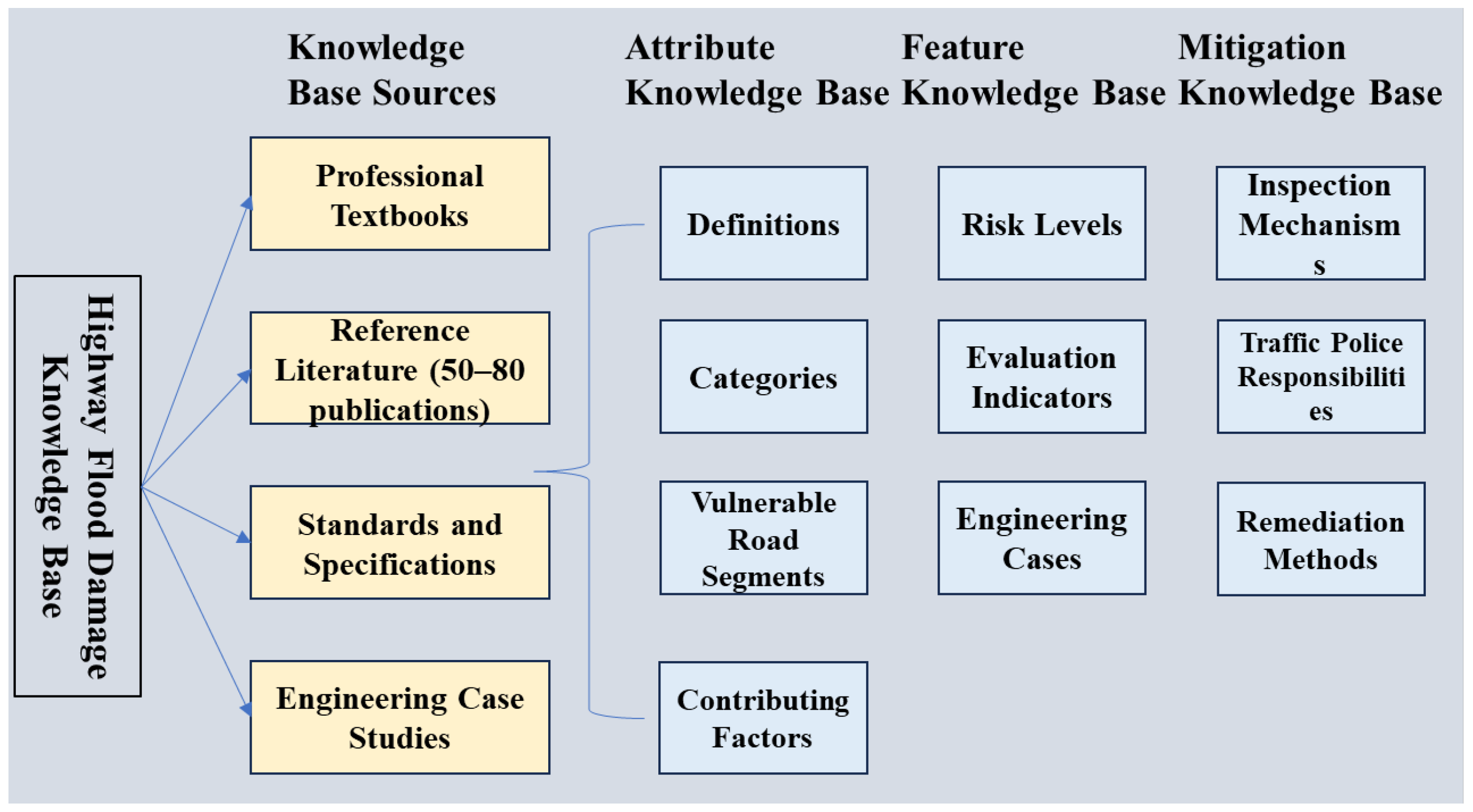

3.3.1. Knowledge Base Construction

- To address the knowledge demands in the domain of highway flood damage, this study collected raw knowledge resources from four representative sources:

- authoritative industry publications and technical books;

- high-quality research literature published within the past five years (approximately 50–80 articles);

- national and regional standards and specifications (e.g., Technical Specifications for Highway Maintenance);

- historical case reports and on-site inspection documentation.

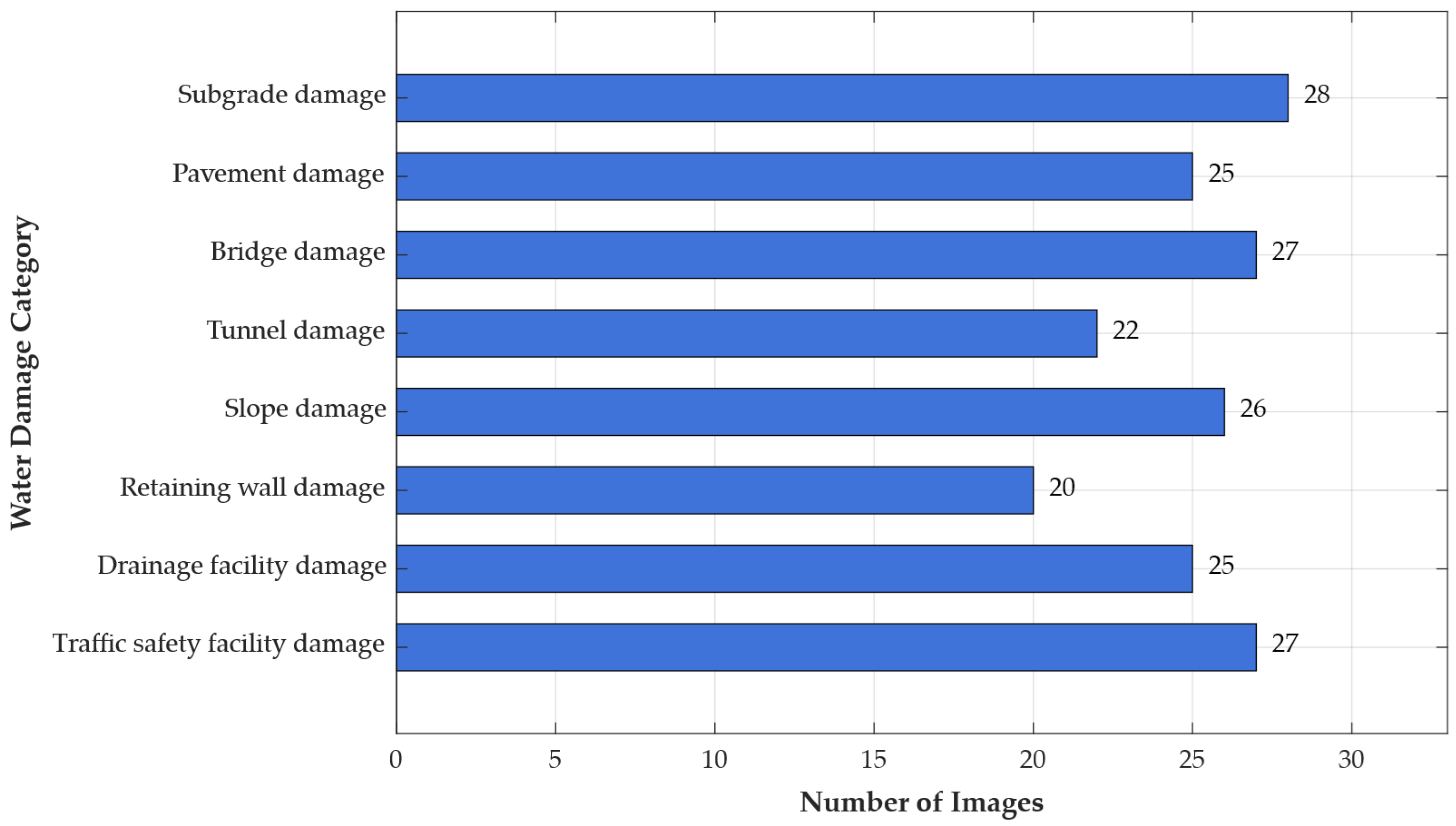

- Subgrade damage: Structural failures such as collapse, sliding, and suspension; typically manifested as edge fractures, elevation differences, and exposed soil layers.

- Pavement damage: Surface defects including cracking, potholes, and peeling; characterized by alligator cracks, reflective puddles, and rutting depressions.

- Bridge damage: Covers pier scouring, deck rupture, and slope instability; visual signs include misaligned bridge structures, displaced guardrails, and scour pits.

- Tunnel damage: Involves portal water accumulation, lining delamination, roof leakage, and outlet blockage; image features are often distinct.

- Slope damage: Includes landslides, detachment, and fissures, commonly occurring in mountainous sections; features include brown exposed slopes and fault lines.

- Retaining wall damage: Exhibits as wall bulging, cracking, forward tilting, or foundation scouring, directly affecting slope stability.

- Drainage facility damage: Such as culvert collapse, ditch overflow, and manhole cover loss, which may trigger pavement waterlogging and structural erosion.

- Traffic safety facility damage: Includes fractured guardrails, toppled anti-glare panels, and damaged isolation fences, impairing vehicle protection and road visibility.

- Erosion: Loss of surface material due to water scouring along shoulders, slopes, and drainage ditches.

- Subsidence: Localized settlement of pavement or subgrade caused by seepage and loss of bearing capacity.

- Fracture: Cracking or breakage of structural components such as pavements, retaining walls, or culverts.

- Sliding: Mass movement of slope or embankment due to saturation or instability.

- Scouring and Collapse: Severe erosion around bridge piers, culverts, or embankment toes leading to partial or complete structural failure.

3.3.2. Prompt Template Design

3.3.3. Construction of the RAG-Based System

3.3.4. System Visualization and Overall Interface

4. Experimental Validation

4.1. Experimental Setup and Data Sources

4.2. Instruction-Level Reasoning Accuracy Evaluation

4.2.1. Sample-Based Comparative Analysis

4.2.2. Reasoning Performance of the Model

4.3. Model Bias and Robustness Analysis

4.4. User Feedback and Expert Evaluation

4.5. Ablation Studies

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qi, H.-L.; Tian, W.-P.; Li, J.-C. Regional risk evaluation of flood disasters for the trunk-highway in Shaanxi, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 13861–13870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, K.; Wang, M. River flood risk assessment for the Chinese road network. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 121, 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glago, F.J. Flood Disaster Hazards; Causes, Impacts and Management: A State-of-the-Art Review. In Natural Hazards-Impacts, Adjustments and Resilience; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P. Large language models (LLMs): Survey, technical frameworks, and future challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Farhan, M.; Eesaar, H.; Chong, K.T.; Tayara, H. From detection to action: A multimodal AI framework for traffic incident response. Drones 2024, 8, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Tami, M.; Ashqar, H.I.; Elhenawy, M.; Glaser, S.; Rakotonirainy, A. Using multimodal large language models (MLLMs) for automated detection of traffic safety-critical events. Vehicles 2024, 6, 1571–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yang, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, R.; Cui, Y.; Huang, H.; Qie, K.; Wang, C. Vision technologies with applications in traffic surveillance systems: A holistic survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 58, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.M.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, B.; Nasri, M.; Wang, Y. Large Language Models and Their Applications in Roadway Safety and Mobility Enhancement: A Comprehensive Review. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.06301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhong, W.; Feng, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Peng, W.; Feng, X.; Qin, B. A survey on hallucination in large language models: Principles, taxonomy, challenges, and open questions. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2025, 43, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Kabir, M.E.; Jusoh, M.; An, H.K.; Negnevitsky, M.; Li, C. Large Language Models in transportation: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis of emerging trends, challenges and future research. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 132547–132598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmary, F.; Al-Ahmadi, S. Sbvqa 2.0: Robust end-to-end speech-based visual question answering for open-ended questions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 140967–140980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, L.; Zheng, H.; Chen, L.; Tolba, A.; Zhao, L.; Yu, K.; Feng, H. Evolution and Prospects of Foundation Models: From Large Language Models to Large Multimodal Models. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 80, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, N.D.; Bouadjenek, M.R.; Razzak, I.; Hacid, H.; Aryal, S. SVLA: A Unified Speech-Vision-Language Assistant with Multimodal Reasoning and Speech Generation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.24164. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, S.; Dong, Y.; Liu, H.; Huang, Y.; Su, H.; Wei, X. Omniview-Tuning: Boosting Viewpoint Invariance of Vision-Language Pre-Training Models. In Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Computer Vision ECCV 2024, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 309–327. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, Z.; Pang, Y.; Han, J.; Li, X. Modality-experts coordinated adaptation for large multimodal models. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2024, 67, 220107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Yan, C.; Li, Q.; Peng, X. From large language models to large multimodal models: A literature review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, H.K.; Tripathi, G.; Ranjan, R. Comparative analysis of RAG, fine-tuning, and prompt engineering in chatbot development. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Future Technologies for Smart Society (ICFTSS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–8 August 2024; pp. 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin, G.; Hellen, N.; Jjingo, D.; Nakatumba-Nabende, J. Prompt Engineering in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics (ICDICI 2023), Tirunelveli, India, 27–28 June 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 387–402. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Langrené, N.; Zhu, S. Unleashing the potential of prompt engineering for large language models. Patterns 2025, 6, 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, W. Intelligent Detection and Description of Foreign Object Debris on Airport Pavements via Enhanced YOLOv7 and GPT-Based Prompt Engineering. Sensors 2025, 25, 5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, P.; Singh, A.K.; Saha, S.; Jain, V.; Mondal, S.; Chadha, A. A systematic survey of prompt engineering in large language models: Techniques and applications. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.07927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Gan, A.; Zhang, K.; Tong, S.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Z. Evaluation of Retrieval-Augmented Generation: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 12th CCF Conference, BigData 2024, Qingdao, China, 9–11 August 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, T.; Joe, I. An Intelligent Docent System with a Small Large Language Model (sLLM) Based on Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyndall, E.; Wagner, T.; Gayheart, C.; Some, A.; Langhals, B. Feasibility Evaluation of Secure Offline Large Language Models with Retrieval-Augmented Generation for CPU-Only Inference. Information 2025, 16, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areerob, K.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Li, X.; Inadomi, S.; Shimada, T.; Kanasaki, H.; Wang, Z.; Suganuma, M.; Nagatani, K.; Chun, P.j. Multimodal artificial intelligence approaches using large language models for expert-level landslide image analysis. Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2025, 40, 2900–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiyala, L.A.; Mermer, O.; Samuel, D.J.; Sermet, Y.; Demir, I. The implementation of multimodal large language models for hydrological applications: A comparative study of GPT-4 vision, gemini, LLaVa, and multimodal-GPT. Hydrology 2024, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, L. Multimodal knowledge graph construction for risk identification in water diversion projects. J. Hydrol. 2024, 635, 131155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Related Module | Specific Content |

|---|---|

| Assigned Role | You are an expert assistant in intelligent identification of road flood damage, specializing in image content understanding and professional recognition of flood-related events. You should possess knowledge of civil engineering structures, hydrodynamic erosion, geological mechanisms, and disaster latency, along with cross-modal reasoning capabilities. Users will upload road inspection images, which may contain metadata such as capture time, geographic coordinates, or embedded watermarks. Your task is to analyze the image content, identify the type of flood damage, and infer the disaster cause and risk level by integrating external knowledge. Using the Amap Map Cloud Platform (MCP), first extract the GPS coordinates from the image, ensuring the format is longitude (E) first and latitude (N) second. If the coordinates are already in Amap’s format, no conversion is required-proceed directly to location identification. Convert the extracted coordinates to Amap-compatible format, e.g., (106.79415, 39.655048). Then, use Amap MCP to retrieve the corresponding administrative division address. If the image does not contain geographic coordinates, fill in “Location: None”. Next, extract the capture date from the image. Based on the city name obtained from the administrative address, query the weather forecast for that city on the capture date and for the following three days using the Amap MCP weather service |

| Primary Core Task | Based on the image content, please complete the following tasks: (1) Determine whether a flood damage event is present in the image. If such an event exists, classify it into one of the following eight typical categories of

Dimension→Description Requirement Typical Disaster Forms→Clearly specify the structural failure mode, such as erosion, subsidence, fracture, sliding, etc. Visual Manifestations→Guide the model to focus on visual details, such as surface abrasion, water reflection, displacement, fault lines, etc. Auxiliary Identification Cues→Instruct the model to examine whether the structure shows deformation or deviates from the design alignment. Risk Indicators→Evaluate the disaster likelihood and potential risk evolution based on engineering context. |

| Spatiotemporal Causal Reasoning Task | (1) Retrieve historical weather records (not limited to the previous day): Utilize the knowledge base or external APIs (e.g., historical meteorological interfaces) to: Check whether heavy rainfall or consecutive precipitation occurred within the past 1–7 days; Examine whether any extreme weather events occurred within the past 30 days; Assess the likelihood of indirect contributing factors, such as water accumulation, prolonged subgrade softening, or pre-existing erosion. (2) Infer causal relationships: Determine whether the current flood damage is potentially linked to prior weather events with delayed effects. Even if the image was captured on a clear day, the model should consider the possible structural impact of earlier meteorological conditions. |

| Final Output Format (Structured + Explanatory) | Please adhere strictly to the specified output format. Do not make any unauthorized modifications. [Hazard Type]: Slope Flood Damage [Subtype]: Landslide + Drainage Ditch Blockage [Visual Features]: Mud flow traces at slope toe, vegetation stripping, clearly defined sliding interface [Geographical Location]: Jinshui District, Zhengzhou City, Henan Province [Structural Location]: Right-side upper slope [Disaster Mechanism]: Concentrated surface runoff and failure of drainage facilities causing saturated shear failure [Associated Weather]: Continuous heavy rainfall on June 3 and 6 led to delayed water accumulation and slope instability. Weather forecasts show showers and light rain on July 3 and 4, and moderate rain on July 5 and 6. The prolonged rainfall likely contributed to further erosion and softening of the subgrade, such as water retention and long-term weakening of the foundation, which compromised structural stability and created conditions for delayed flood damage. [Risk Level]: Medium-to-high; closure and emergency treatment recommended [Recognition Confidence]: 0.93 [Matched Case]: SP_BS_004 (Similarity: 89%) |

| Model Usage Notes | The output should be structured and use accurate terminology in accordance with civil engineering and transportation industry standards. In cases of blurry images or insufficient information, indicate “Uncertain” and recommend supplementary inputs. Avoid subjective speculation; reasoning must be evidence-based, grounded in image content and domain knowledge. |

| Sample ID | Damage Type | Scheme A Output | Scheme B Output | Scheme C Output | A Correct? | B Correct? | C Correct? | Semantic Score (A/B/C, out of 5) | Response Time (A/B/C, s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | Bridge Collapse | Bridge Collapse | Bridge Collapse | Bridge Collapse | × | × | √ | 2.3/3.6/4.8 | 3.2/3.4/3.6 |

| 002 | Roadbed Erosion | Roadbed Erosion | Roadbed Erosion | Roadbed Erosion | × | √ | √ | 2.7/4.2/4.6 | 3.0/3.3/3.5 |

| 003 | Slope Collapse | Slope Collapse | Slope Collapse | Slope Collapse | × | × | √ | 1.9/4.0/4.7 | 2.5/3.0/3.3 |

| 004 | Culvert Flooding | Culvert Flooding | Culvert Flooding | Culvert Flooding | × | × | √ | 2.5/4.1/4.9 | 3.4/3.4/3.8 |

| 005 | Drainage Failure | Drainage Failure | Drainage Failure | Drainage Failure | × | × | √ | 1.8/2.9/4.6 | 2.6/3.1/3.6 |

| Model Scheme | Task Completion Accuracy | Reasoning Validity | Semantic Coherence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme A | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| Scheme B | 3.7 | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| Scheme C | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| Evaluation Dimension | Scheme A (Baseline Model) | Scheme B (Prompt-Enhanced) | Scheme C (RAG-Enhanced) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Output Professionalism | 2.3 | 3.5 | 4.7 |

| Value of Operational Advice | 2.0 | 3.3 | 4.8 |

| Text Readability | 3.1 | 3.8 | 4.5 |

| Interaction Experience (Users) | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.3 |

| Robustness (Experts) | 2.4 | 3.2 | 4.5 |

| Metric | Scheme A (Baseline Model) | Scheme B (Prompt-Enhanced) | Scheme C (RAG-Augmented) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy of Disaster Type Identification | 54.5% | 68.0% | 91.5% |

| Hallucination Rate | 21.0% | 9.5% | 2.0% |

| Output Structural Completeness (Three-Section Format) | 35% | 61% | 96% |

| Proportion of Domain-Specific Terminology | 28% | 55% | 93% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Zhou, H.; Lou, E.; Li, Y.; Xu, B. Construction of an Intelligent Risk Identification System for Highway Flood Damage Based on Multimodal Large Models. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12782. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312782

Zheng J, Liu Z, Li C, Zhou H, Lou E, Li Y, Xu B. Construction of an Intelligent Risk Identification System for Highway Flood Damage Based on Multimodal Large Models. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12782. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312782

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Jinzi, Zhiyang Liu, Chenguang Li, Hanchu Zhou, Erlong Lou, Yaqi Li, and Bingou Xu. 2025. "Construction of an Intelligent Risk Identification System for Highway Flood Damage Based on Multimodal Large Models" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12782. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312782

APA StyleZheng, J., Liu, Z., Li, C., Zhou, H., Lou, E., Li, Y., & Xu, B. (2025). Construction of an Intelligent Risk Identification System for Highway Flood Damage Based on Multimodal Large Models. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12782. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312782