Assessment of the Impact of Blasting Operations on the Intensity of Gas Emission from Rock Masses: A Case Study of Hydrogen Sulfide Occurrence in a Polish Copper Ore Mine

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Rock bursts;

- Roof control method during the liquidation of a selected space;

- Changes in atmospheric air pressure;

- Depression of the main ventilation fan station;

- Changes in local depressions in the ventilation network;

- Use of explosives in deposit mining technology.

2. Experiment Description

2.1. Mining Area for Experiment

2.2. Measurement System

3. Experiment Results

4. Data Analysis

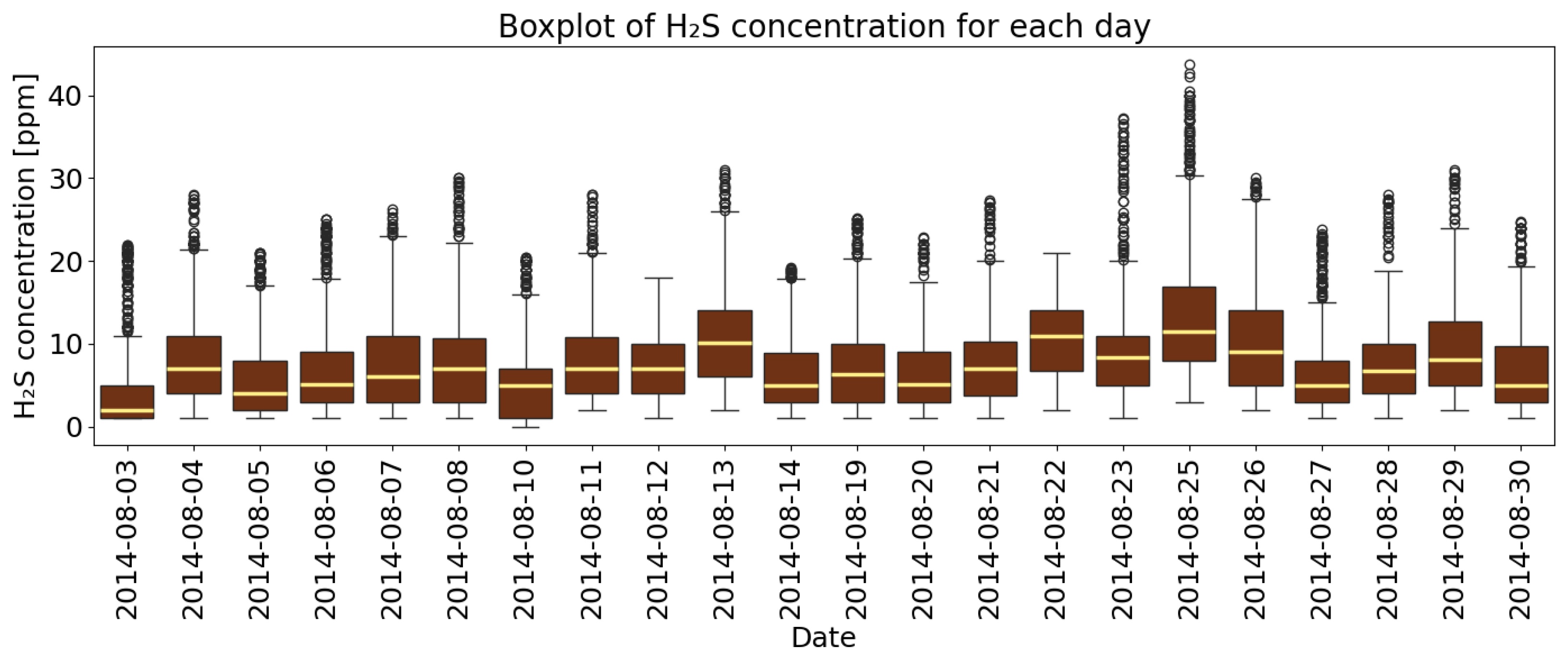

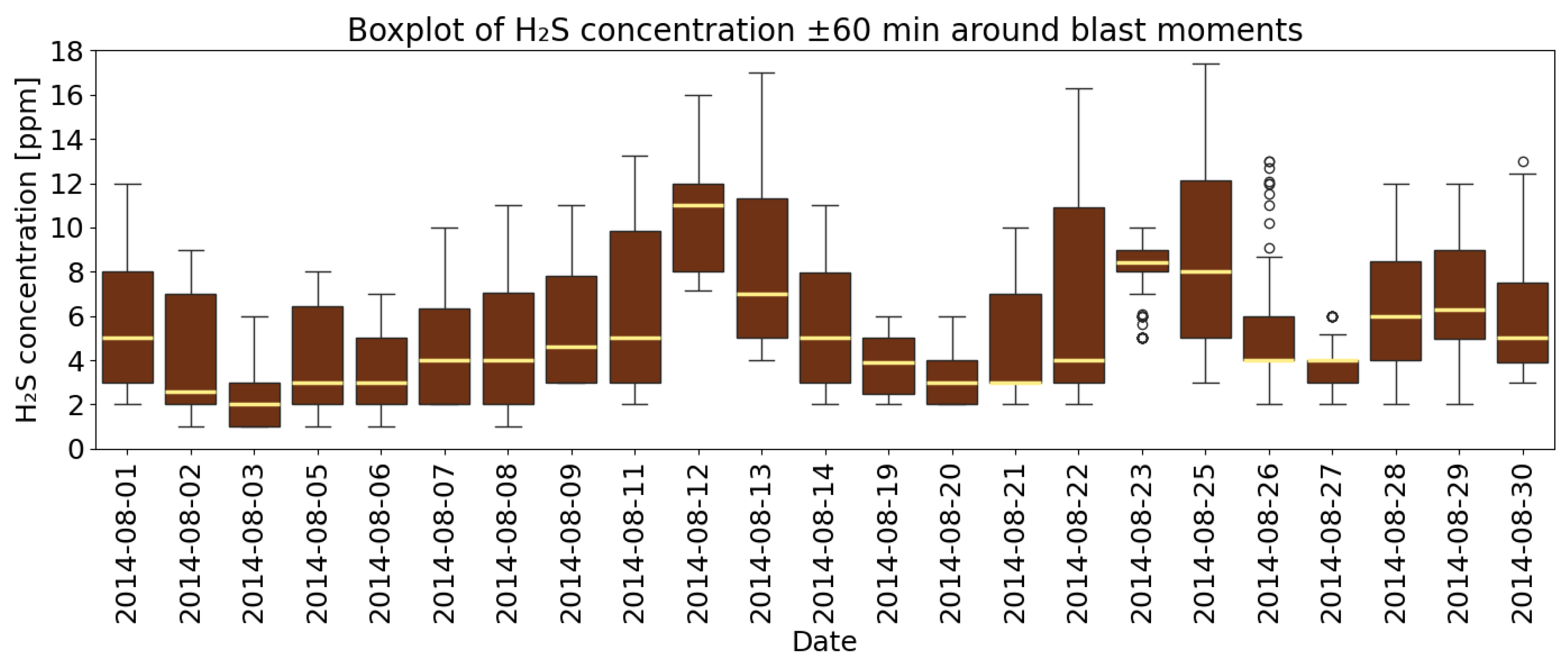

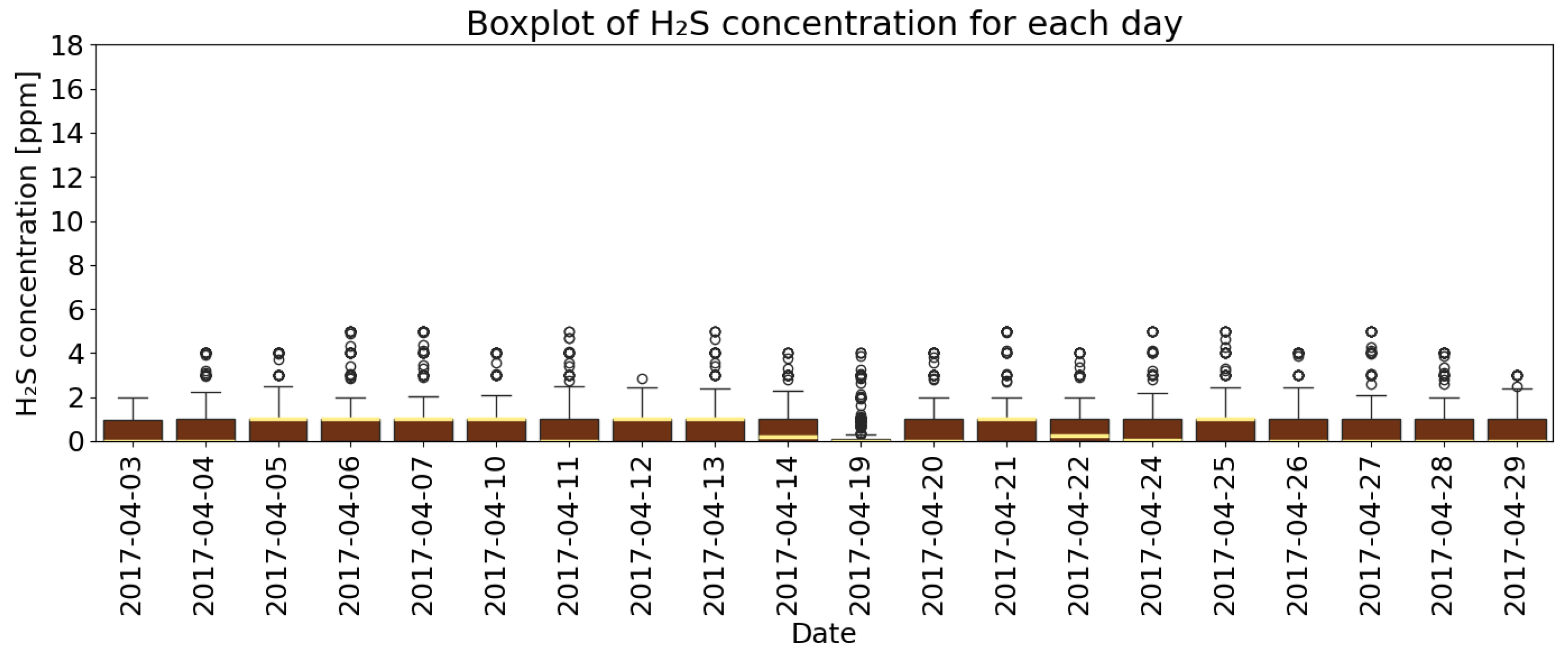

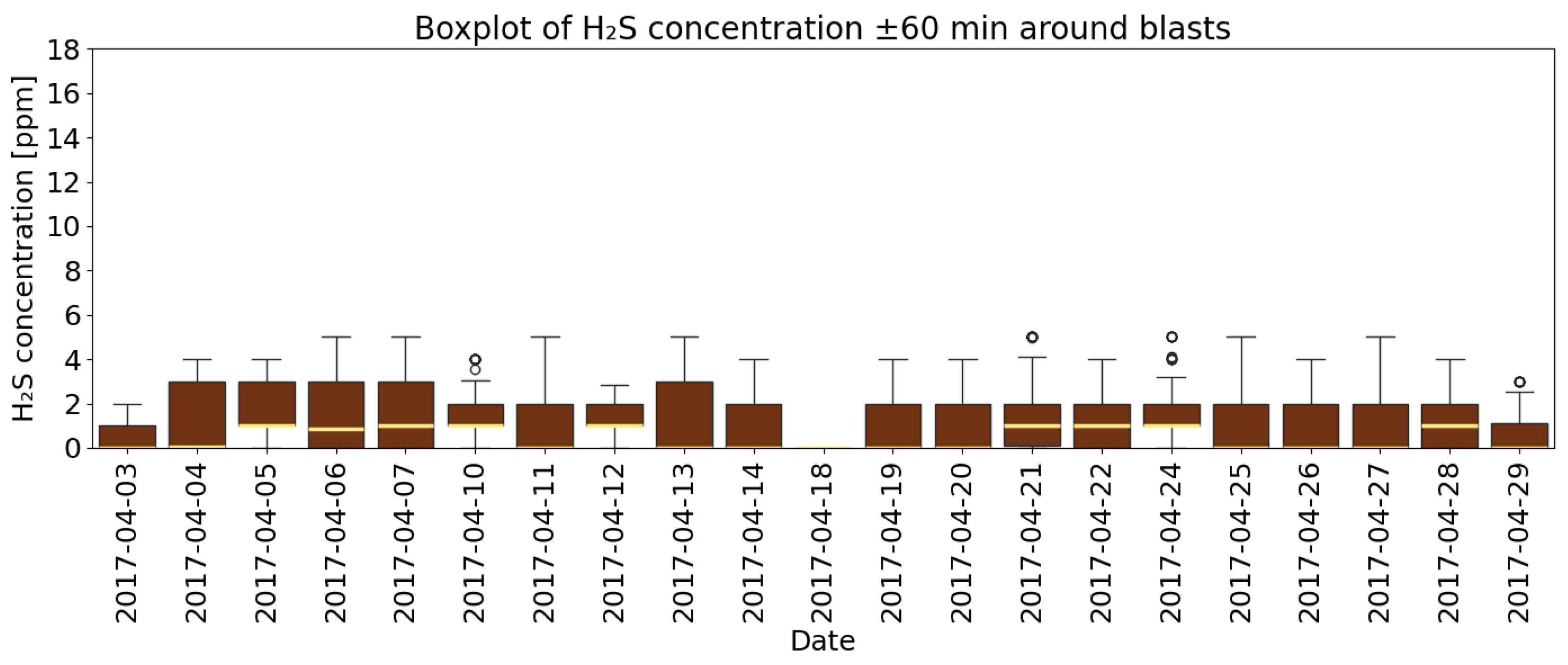

4.1. Basic Descriptive Statistics of Measurement Data

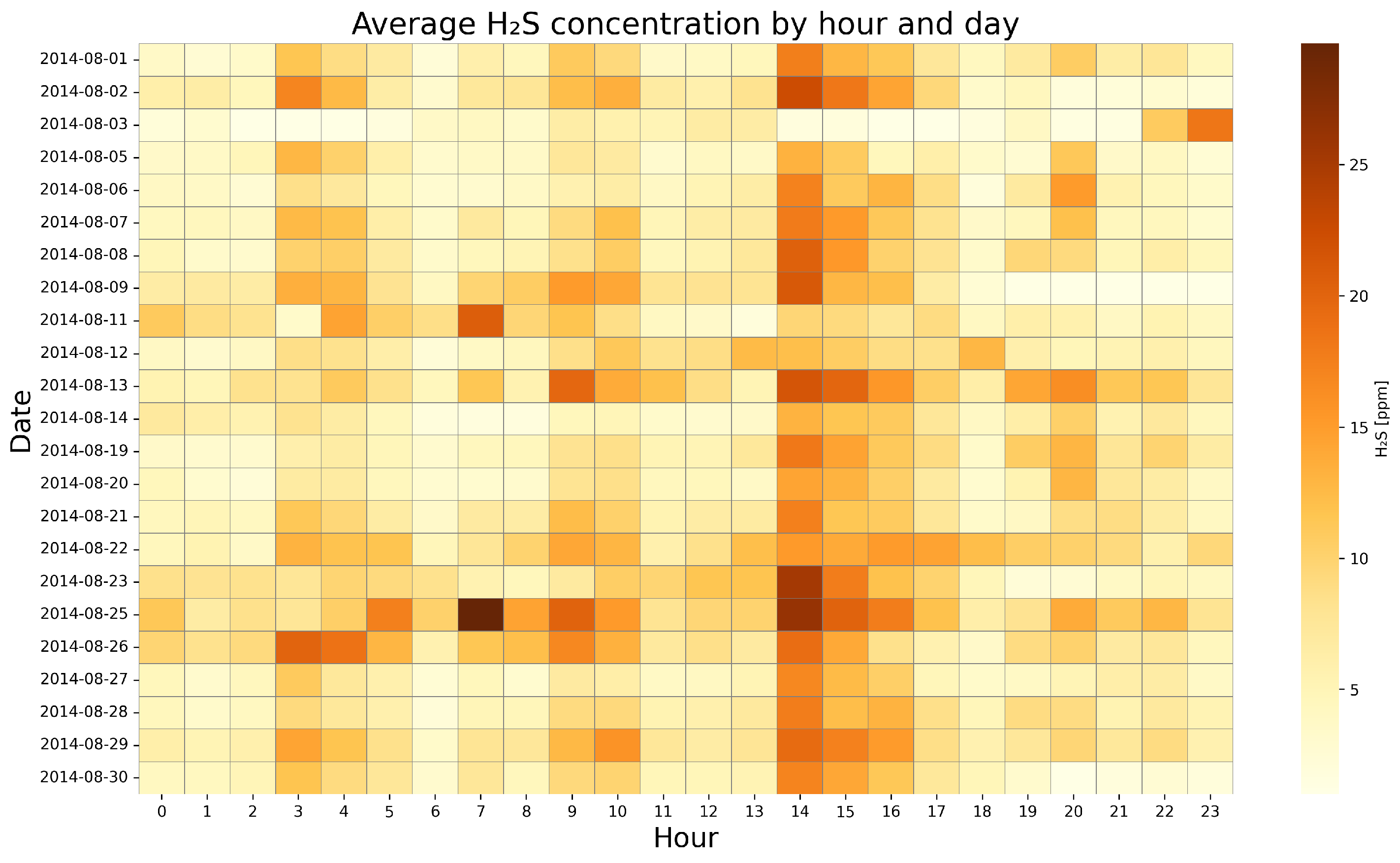

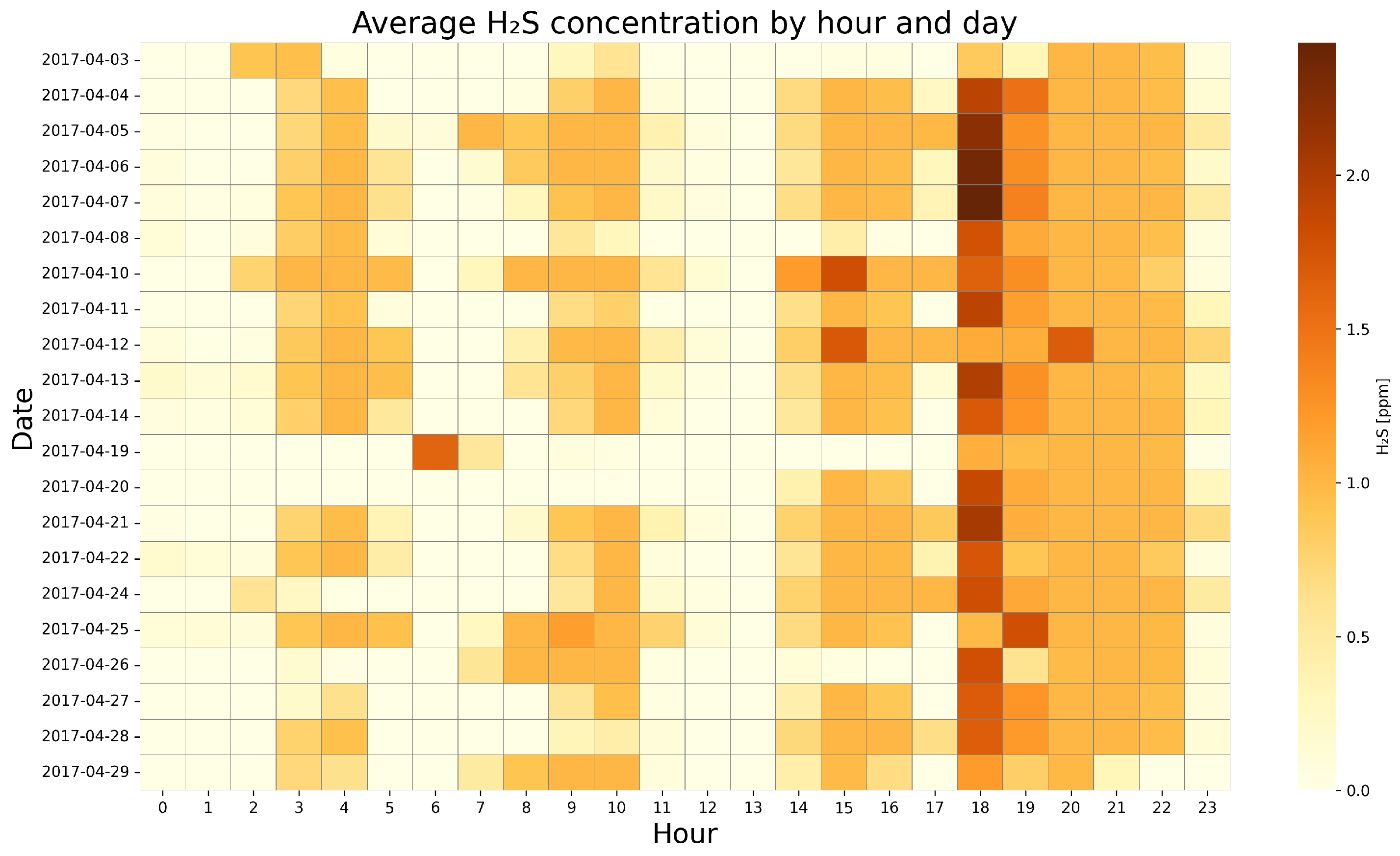

4.2. Visualization of Temporal Dynamics of Gas Concentrations—Heat Map Analysis

4.3. A Detailed Assessment of the Impact of Blasting Operations on the Mine Atmosphere—Event Study Analysis

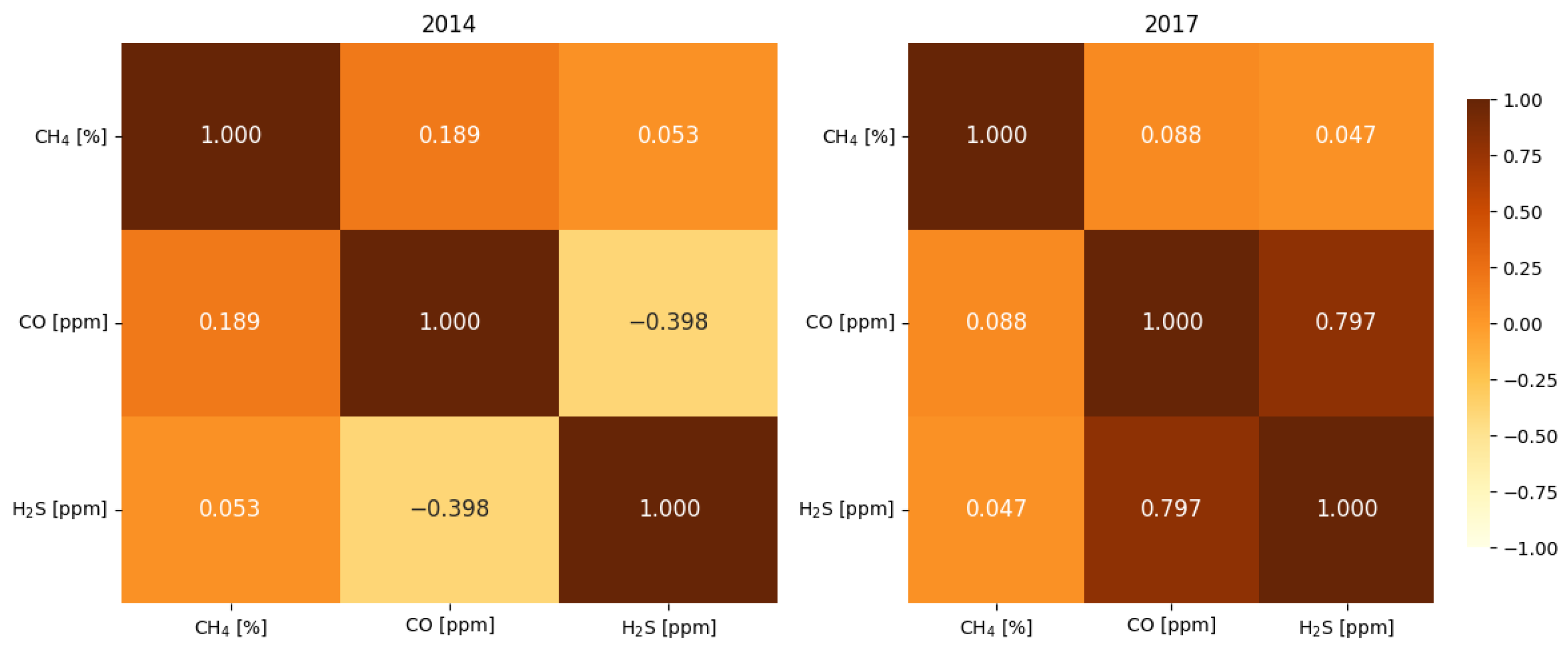

4.4. Correlation Analysis of Gaseous Hazards and Environmental Factors

4.5. Analysis of the Dynamics of Changes in the Composition of the Mine Atmosphere After Blasting

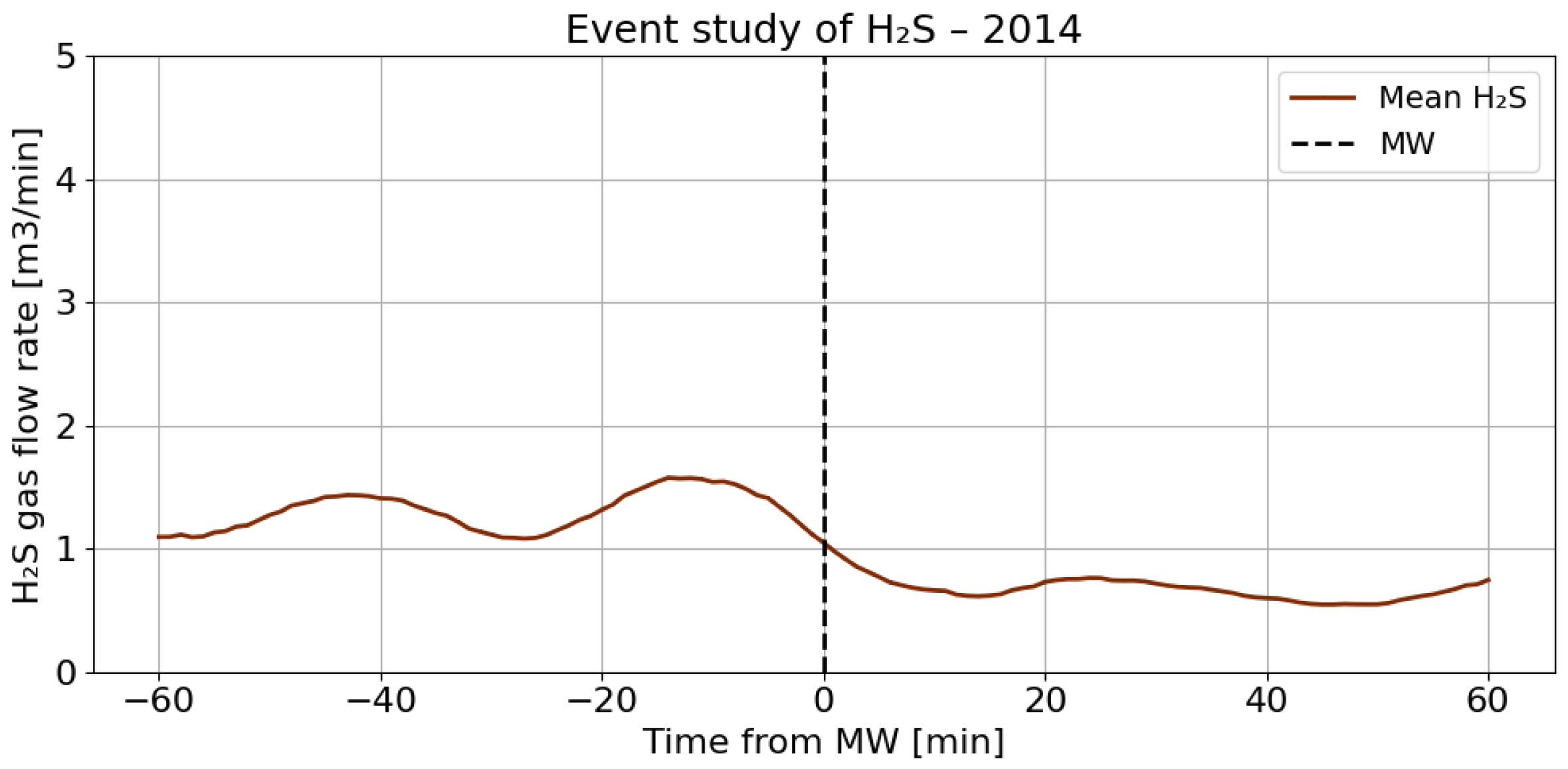

4.5.1. Analysis of the Timing of the Increase in H2S Concentration After Blast in 2014

- Increment derivative of concentration (rate of H2S increase in consecutive minutes):where are successive time points (minutes) within the post-blast interval.

- Time to reach the maximum H2S concentration after the blast:That is, the time difference between the moment of the blast and the time at which the maximum concentration occurs within the analyzed window.

- Mean time to reach maximum H2S concentration for all blasts in the analyzed period:where denotes the number of blasts analyzed, and is the time to reach the maximum concentration after the j-th blast.

4.5.2. Analysis of Mine Atmosphere Stabilization Time After Blasts in 2017

- Stabilization criterion of H2S concentration within the time interval :where is the length of the concentration change analysis window, and is the variability threshold considered as the equilibrium state of the atmosphere.

- Atmospheric stabilization time after the blast:that is, the shortest time after the blast at which the H2S concentration remains stable during the following 10 min of measurement.

- Mean stabilization time for all analyzed blasts:where denotes the number of analyzed blasts, and is the stabilization time after the j-th blast.

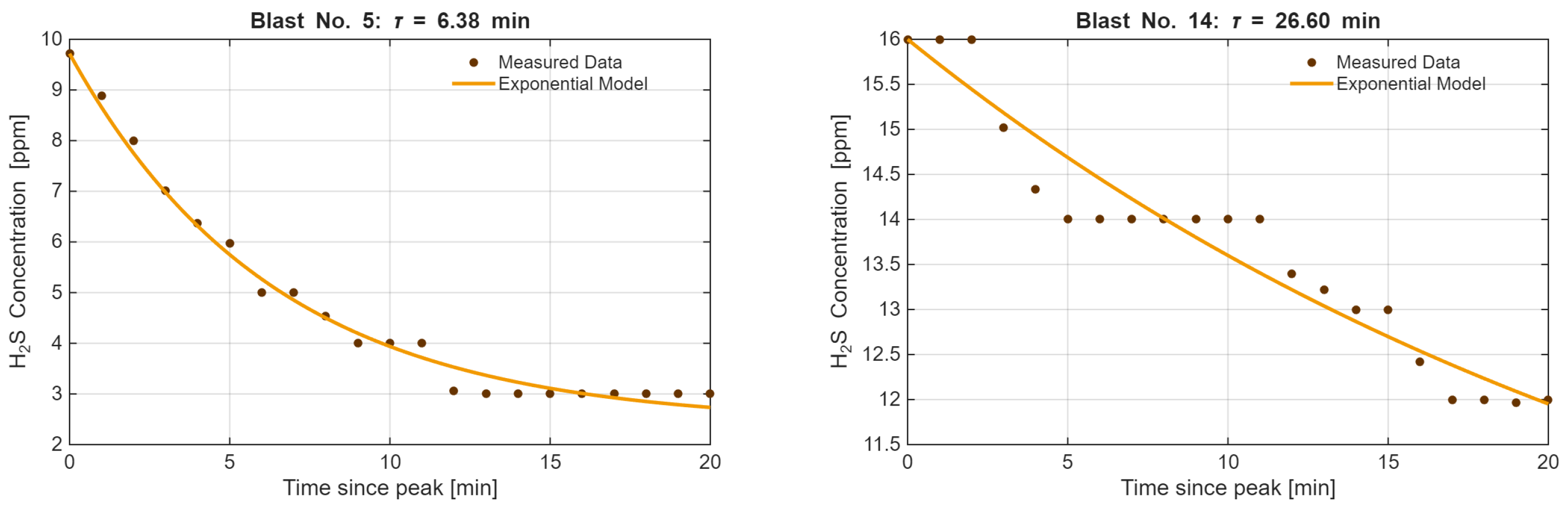

4.6. Time Constant (τ) in Post-Blast Ventilation

- Year 2014: For the blasting events analyzed in 2014, the estimated time constants ranged from approximately 5.5 to 48 min. This suggests a generally variable ventilation efficiency, dependent on the specific location of the mining faces during that period.

- Year 2017: In 2017, the values of varied between almost 7 and 54 min. The distribution of values in this period reflects the ventilation conditions associated with the gas emissions observed in 2017.

5. Conclusions

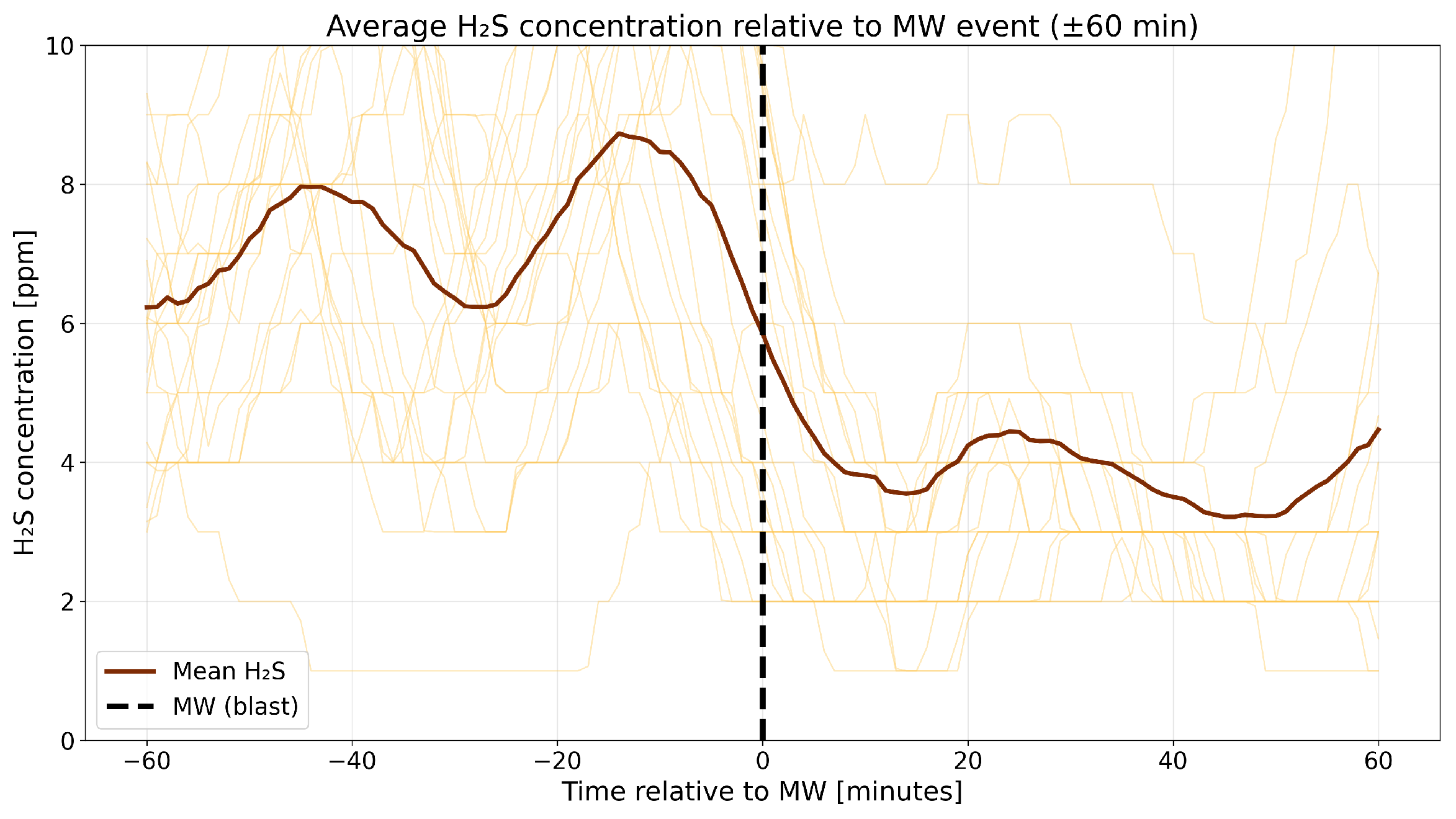

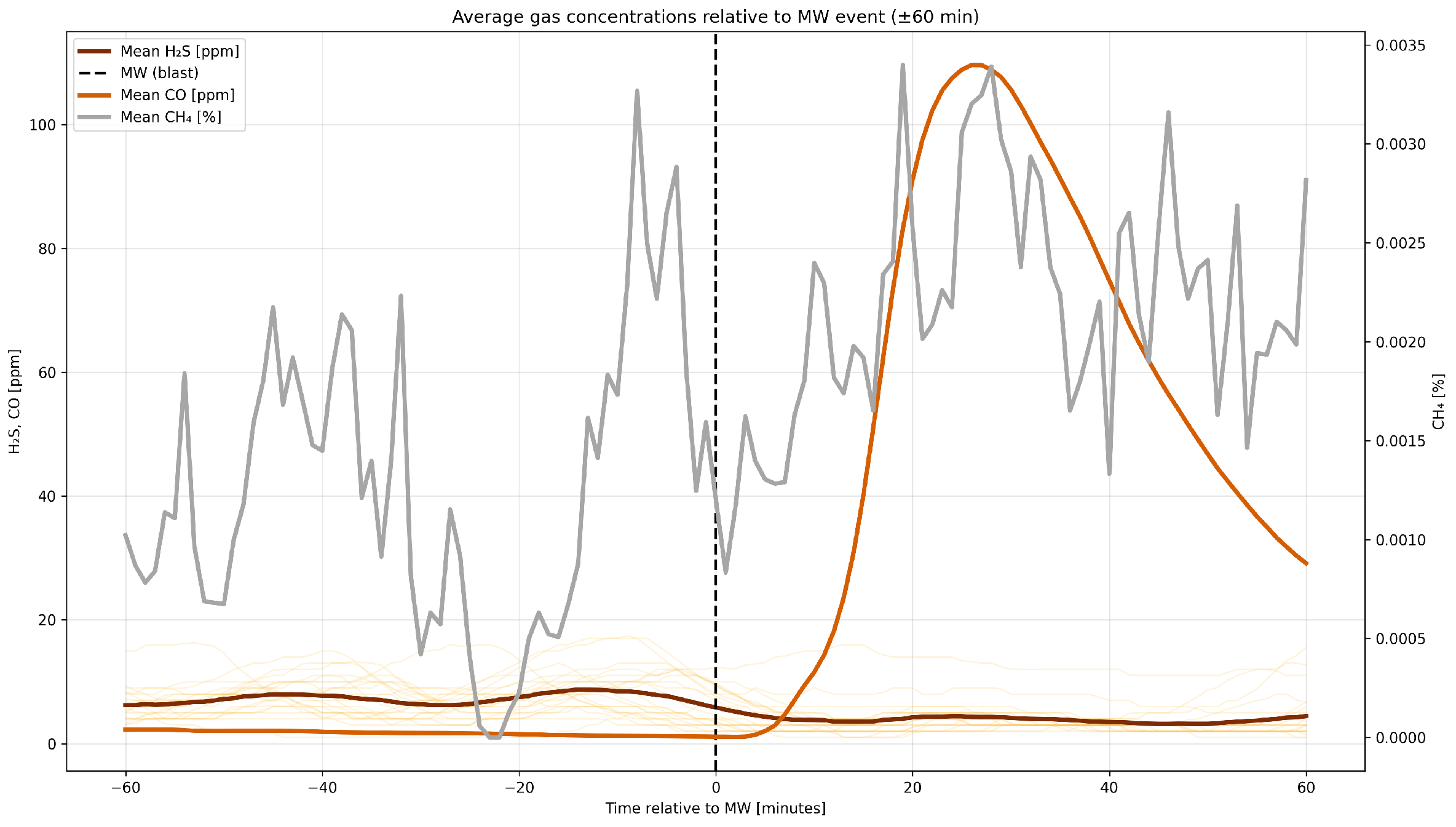

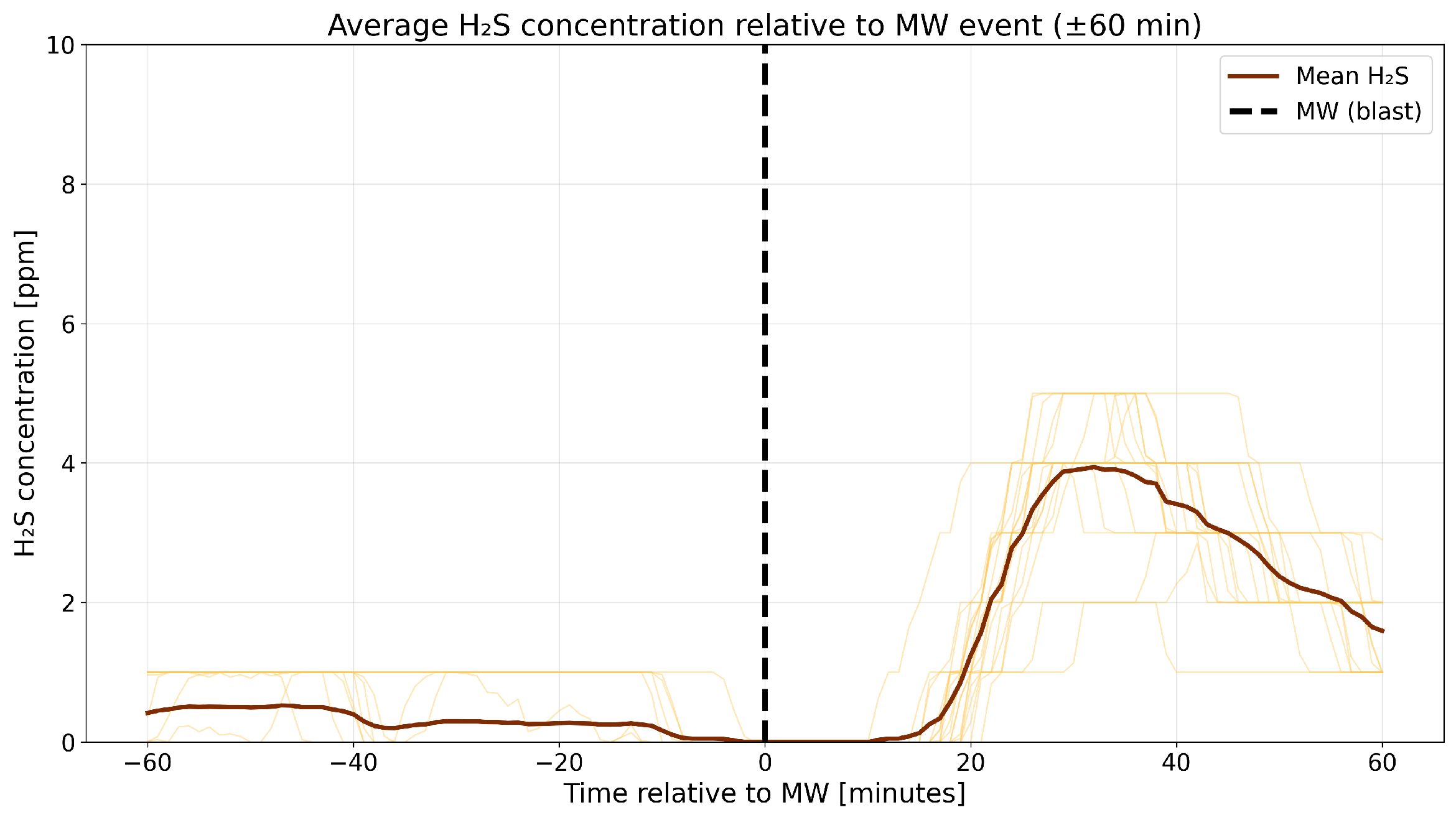

- Explosive blasting with explosives causes an increased outflow of hydrogen sulfide and other gases from the rock mass into the excavations. Explosive blasting with explosives causes an increased outflow of hydrogen sulfide from the rock mass, which is reflected in the observed increase in H2S concentration in the excavation approximately one hour after the blast. Analysis of data from 2014 and 2017 indicates that this effect is strongly dependent on the initial gas level in the excavation—under conditions of low H2S concentration before the blast, a significant, though limited in absolute terms, increase in the post-blast concentration is observed, whereas at higher initial concentrations, the blast can cause a short-term decrease in the average concentration, suggesting the effects of gas mixing and dispersion due to air movement in the excavation. These results confirm that explosives not only mechanically cut the rock but also induce changes in gas emissions from the rock mass, which is important for mine hazard assessment and ventilation planning.

- Analysis of H2S concentrations within the ±range 60 min after blasting showed that in 2014, the average concentration decreased after blasting, whereas in 2017, blasting caused a significant increase in concentration, although the absolute values were much lower. These results suggest that the impact of blasting on H2S concentrations in the excavation varies depending on the year and the initial gas level. In 2014, at higher initial concentrations, blasting led to a lower average concentration, which may indicate mixing or ventilation effects. In 2017, however, with very low H2S levels before blasting, the observed increase in concentration after blasting suggests a local gas release, the effects of which were limited due to the low initial concentration.

- Analysis of H2S concentrations during blasting operations in 2014 and 2017 revealed varying behavior. In 2014, H2S exhibited a moderate negative correlation with CO ( = −0.398) and no significant correlation with CH4 ( = 0.053), while in 2017, a strong positive H2S–CO correlation was observed ( = 0.797), with a still negligible correlation with CH4 ( = 0.047). Analysis within ±60 min of blasting showed that in 2014, higher initial H2S concentrations decreased after detonation, likely due to ventilation, while in 2017, lower initial levels increased locally after the blast. The strong H2S–CO correlation is due to their co-production and transport by detonation, while CH4 remains largely independent due to other sources and slower release.

- The average time to reach the maximum concentration of H2S after the use of explosives in 2014 was 24 min 25 s, while in 2017 it was 29 min and 22 s. The time to stabilize the atmosphere in the mine in 2014 was 58 min 15 s, while in 2017 it was 40 min and 57 s. The highest concentration values occur within the first hour after detonation. This result is an important factor to consider in safety procedures—particularly when planning the airflow volume supplied to the mining area, post-blast ventilation time, planning measurements, and assessing personnel exposure. The study demonstrates that the time constant is a critical parameter for mine safety management, extending beyond simple statistical analysis. It was estimated through fitting the non-linear equation to the measurement data. As a variable it is aggregating the influence of key ventilation factors—distance from the face to the gas concentration measurement point (L) and airflow velocity (v)—provides a comprehensive metric of the system’s inertia.

- The average H2S concentration values obtained after mining blasting did not exceed the 7 ppm threshold in any of the analyzed periods. An increase in hydrogen sulfide concentrations was observed after mining blasting, but this increase did not exceed the permissible value. This phenomenon is crucial for worker safety. The average face ventilation time, approximately 30–40 min before crew access, is a key element in personnel protection—it allows for the effective removal of residual gases and ensures safe working conditions.

- Further work should consider the impact of explosive mass and the number of blast faces on the dynamics of H2S concentration. Further research should focus on a detailed analysis of the H2S concentration growth curve following blasting, taking into account both the rate and time of reaching maximum values, and the time for the concentration to decline to baseline values. An important direction will also be to assess the impact of the mass of explosive used and the number of blast faces fired on the dynamics of hydrogen sulfide emissions, which will allow for a better understanding of the relationship between blasting parameters and mine atmosphere safety.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ismail, S.N.; Ramli, A.; Aziz, H.A. Influencing factors on safety culture in mining industry: A systematic literature review approach. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Obracaj, D.; Gao, K.; Shi, L. The Research on Demand-Based Regulation of Mine Airflow Based on Niche Genetic Algorithm. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 170844–170861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasiewicz, A.; Janicka, A. Selection of a Universal Method for Measuring Nitrogen Oxides in Underground Mines: A Literature Review and SWOT Analysis. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, A.; Nadeau, S.; Gbodossou, A. A new practical approach to risk management for underground mining project in Quebec. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2013, 26, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Rinne, M. Geotechnical Risk classification for underground mines. Arch. Min. Sci. 2015, 60, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugarski, A.D.; Cauda, E.G.; Janisko, S.J.; Mischler, S.E.; Noll, J.D. Diesel Aerosols and Gases in Underground Mines: Guide to Exposure Assessment and Control; Report of Investigations 9687; National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Dreger, M. Methane emissions and hard coal production in the Upper Silesian Coal Basin in relation to the greenhouse effect increase in Poland in 1994–2018. Min. Sci. 2021, 28, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.y.; Ji, H.g.; Lü, X.f.; Wang, T.; Zhi, S.; Pei, F.; Quan, D.l. Mitigation of greenhouse gases released from mining activities: A review. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2021, 28, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasiewicz, A.; Wroblewski, A.; Gola, S. Preliminary sources identification of nitric oxide (NO) emissions in underground mine. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 942, p. 012019. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B.; Shao, Z.; Wei, H.; Yang, G.; Zhu, X.; Xu, B.; Zhang, F. Status of research on hydrogen sulphide gas in Chinese mines. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 2502–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Energy. Regulation of the Minister of Energy related to operations of underground mining (available in Polish: Rozporzadzenie Ministra Energii z dnia 23 listopada 2016r.,w sprawie szczegółowych wymagań dotyczacych prowadzenia ruchu podziemnych zakładów górniczych. In Dz. U. z 2017r.,poz. 1118; Ministerstwo Energii: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wodzicki, A.; Piestrzyński, A. An ore genetic model for the Lubin—Sieroszowice mining district, Poland. Miner. Depos. 1994, 29, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilecki, Z.; Laskowski, M.; Hryciuk, A.; Wróbel, J.; Koziarz, E.; Pilecka, E.; Czarny, R.; Krawiec, K. Identification of gaso-geodynamic zones in the structure of copper ore deposits using geophysical methods. CIM J. 2014, 5, 194–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kijewski, P.; Kubiak, J.; Gola, S. Siarkowodór-nowe zagrożenie w górnictwie rud miedzi. Zesz. Nauk. Inst. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. Energią PAN 2012, 83, 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, C.; Wang, S.; Sun, P.; Zhao, S.; Mu, X. Analysis of the Formation Mechanism of Hydrogen Sulfide in the 13# Coal Seam of Shaping Coal Mine. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 2980–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Han, Z.; Lin, B.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; et al. A visual color response test paper for the detection of hydrogen sulfide gas in the air. Molecules 2023, 28, 5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, T.S.; Rosolina, S.M.; Xue, Z.L. Quantitative, colorimetric paper probe for hydrogen sulfide gas. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 253, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, N. Problems caused by microbes and treatment strategies health and safety issues from the production of hydrogen sulphide. In Applied Microbiology and Molecular Biology in Oilfield Systems, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Applied Microbiology and Molecular Biology in Oil Systems (ISMOS-2), Stavanger, Norway, 2–5 June 2009; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Batterman, S.; Grant-Alfieri, A.; Seo, S.H. Low level exposure to hydrogen sulfide: A review of emissions, community exposure, health effects, and exposure guidelines. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2023, 53, 244–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.A.; Hassan, N.E. Review of Toxic Gases and Their Impact on Human Health. J. Biointerface Res. Pharm. Appl. Chem. 2024, 1, 7–12. Available online: https://sprinpub.com/jabirian (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Kim, H.; Cho, S.; Jung, I.; Jung, S.; Park, W.J. A case of syncope in a villager with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after hydrogen sulfide exposure by an unauthorized discharge of wastewater. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 35, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Srivastava, V.C. Insight into the thermal kinetics and thermodynamics of sulfuric acid plant sludge for efficient recovery of sulfur. Waste Manag. 2022, 140, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S)—Compound Summary (CID 402). Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/402 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- UK Health Security Agency. Hydrogen Sulphide: Toxicological Overview. Government of the United Kingdom; 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Uliasz-Misiak, B. Ryzyko środowiskowe związane z eksploatacją złóż węglowodorów zawierających siarkowodór. Rocz. Ochr. Środowiska 2015, 17, 1498–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Wang, E.; Wang, G.; Fan, J. Prevention and Control of Hydrogen Sulphide Accidents in Mining Extremely Thick Coal Seam: A Case Study in Wudong Coal Mine. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 8885949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Wang, W.; He, B.G.; Chen, J. Review on optical fiber sensors for hazardous-gas monitoring in mines and tunnels. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebda-Sobkowicz, J.; Gola, S.; Zimroz, R.; Wyłomańska, A. Pattern of H2S concentration in a deep copper mine and its correlation with ventilation schedule. Measurement 2019, 140, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilkiewicz, E.; Borkowski, A.; Duda, R.; Działak, P.; Kowalski, T.; Becker, R. Integrated stable S isotope, microbial and hydrochemical analysis of hydrogen sulphide origin in groundwater from the Legnica-Głogów Copper District, Poland. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 166, 105981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; He, Y. Genesis, controls and risk prediction of H2S in coal mine gas. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Q.; Li, S.; Yao, M.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xiang, S. Study on the factors of hydrogen sulfide production from lignite bacterial sulfate reduction based on response surface method. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Internal Technical Report of KGHM Polska Miedź S.A.; PTE_SI_XIII_GL-I_G-51: Projekt Techniczny; KGHM Polska Miedź S.A.: Lubin, Poland, 2024.

- Butra, J.; Pytel, W. Room-and-pillar mining systems in Polish copper mines. In Mine Planning and Equipment Selection 2004, Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Symposium on Mine Planning and Equipment Selection, Wroclaw, Poland, 1–3 September 2004; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Skrzypkowski, K. Case studies of rock bolt support loads and rock mass monitoring for the room and pillar method in the legnica-głogów copper district in Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevitel Sp. z o.o. Technical Documentation and User Manual of Measurement Device (Available in Polish: Dokumentacja Techniczno-Ruchowa. Instrukcja Użytkowania i Obsługi DTR SEV-256/2014 v3.2. Urządzenie Pomiarowe AZRP); Sevitel Sp. z o.o.: Katowice, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, M.G. Descriptive statistics and graphical displays. Circulation 2006, 114, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydari, S.; Hoseinie, S.H.; Bagherpour, R. Prediction of jumbo drill penetration rate in underground mines using various machine learning approaches and traditional models. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haarman, B.C.B.; Riemersma-Van der Lek, R.F.; Nolen, W.A.; Mendes, R.; Drexhage, H.A.; Burger, H. Feature-expression heat maps—A new visual method to explore complex associations between two variable sets. J. Biomed. Inform. 2015, 53, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorescu, A.; Warren, N.L.; Ertekin, L. Event study methodology in the marketing literature: An overview. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astivia, O.L.O.; Zumbo, B.D. Population models and simulation methods: The case of the Spearman rank correlation. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2017, 70, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, C.; Ye, J.; Esteves, R.M.; Rong, C. Using Spearman’s correlation coefficients for exploratory data analysis on big dataset. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2016, 28, 3866–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | H2S | CO | CH4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement range | 0–200 ppm | 0–1000 ppm | 0–100% |

| Power supply | 12V DC, 10 mA | ||

| Operating temperature | −20 °C to +50 °C | ||

| Humidity range | 0–95% (non-condensing) | ||

| ATEX classification | II M1 Ex ia I Ma | ||

| Protection rating | IP65 | ||

| Communication | RS485 | ||

| August 2014 | April 2017 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Day | Blasting Time | Day | Blasting Time |

| 1 August 2014 | 18:06 | 3 April 2017 | 18:04 |

| 2 August 2014 | 06:20 | 4 April 2017 | 18:10 |

| 3 August 2014 | 01:06 | 5 April 2017 | 18:08 |

| 5 August 2014 | 06:15 | 6 April 2017 | 18:04 |

| 6 August 2014 | 06:17 | 7 April 2017 | 18:05 |

| 7 August 2014 | 06:05 | 8 April 2017 | 18:05 |

| 8 August 2014 | 06:13 | 10 April 2017 | 18:11 |

| 9 August 2014 | 06:10 | 11 April 2017 | 18:05 |

| 11 August 2014 | 18:06 | 12 April 2017 | 18:05 |

| 12 August 2014 | 18:07 | 13 April 2017 | 18:05 |

| 13 August 2014 | 18:08 | 14 April 2017 | 18:03 |

| 14 August 2014 | 18:03 | 19 April 2017 | 06:03 |

| 19 August 2014 | 06:08 | 19 April 2017 | 18:07 |

| 20 August 2014 | 06:11 | 20 April 2017 | 18:06 |

| 21 August 2014 | 06:17 | 21 April 2017 | 18:07 |

| 22 August 2014 | 06:22 | 22 April 2017 | 18:05 |

| 23 August 2014 | 06:15 | 24 April 2017 | 18:11 |

| 25 August 2014 | 18:09 | 25 April 2017 | 18:24 |

| 26 August 2014 | 18:16 | 26 April 2017 | 18:04 |

| 27 August 2014 | 18:07 | 27 April 2017 | 18:13 |

| 28 August 2014 | 18:04 | 28 April 2017 | 18:09 |

| 28 August 2014 | 18:09 | 29 April 2017 | 18:04 |

| 29 August 2014 | 18:06 | ||

| 29 August 2014 | 18:06 | ||

| 30 August 2014 | 18:07 | ||

| 30 August 2014 | 18:17 | ||

| 31 August 2014 | 18:05 | ||

| Statistic | H2S Sensor [ppm] |

|---|---|

| Number of observations (count) | 2783 |

| Mean | 5.61 |

| Standard deviation (std) | 3.40 |

| Minimum (min) | 1.00 |

| 1st quartile (25%) | 3.00 |

| Median (50%) | 5.00 |

| 3rd quartile (75%) | 8.00 |

| Maximum (max) | 17.40 |

| Statistic | H2S Sensor [ppm] |

|---|---|

| Number of observations (count) | 2662 |

| Mean | 1.071 |

| Standard deviation (std) | 1.431 |

| Minimum (min) | 0.00 |

| 1st quartile (25%) | 0.00 |

| Median (50%) | 0.00 |

| 3rd quartile (75%) | 2.00 |

| Maximum (max) | 5.00 |

| Year | Period | Min [ppm] | Mean [ppm] | Max [ppm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Before the blast | 1.000 | 7.255 | 17.400 |

| After the blast | 1.000 | 3.738 | 16.000 | |

| 2017 | Before the blast | 0.000 | 0.267 | 1.000 |

| After the blast | 0.000 | 1.885 | 5.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Banasiewicz, A.; Kotyla, M.; Gola, S. Assessment of the Impact of Blasting Operations on the Intensity of Gas Emission from Rock Masses: A Case Study of Hydrogen Sulfide Occurrence in a Polish Copper Ore Mine. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12781. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312781

Banasiewicz A, Kotyla M, Gola S. Assessment of the Impact of Blasting Operations on the Intensity of Gas Emission from Rock Masses: A Case Study of Hydrogen Sulfide Occurrence in a Polish Copper Ore Mine. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12781. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312781

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanasiewicz, Aleksandra, Michalina Kotyla, and Sebastian Gola. 2025. "Assessment of the Impact of Blasting Operations on the Intensity of Gas Emission from Rock Masses: A Case Study of Hydrogen Sulfide Occurrence in a Polish Copper Ore Mine" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12781. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312781

APA StyleBanasiewicz, A., Kotyla, M., & Gola, S. (2025). Assessment of the Impact of Blasting Operations on the Intensity of Gas Emission from Rock Masses: A Case Study of Hydrogen Sulfide Occurrence in a Polish Copper Ore Mine. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12781. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312781