Research on Low-Frequency Sound Absorption Based on the Combined Array of Hybrid Digital–Analog Shunt Loudspeakers †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory of the Hybrid Digital–Analog Shunt Loudspeaker Array

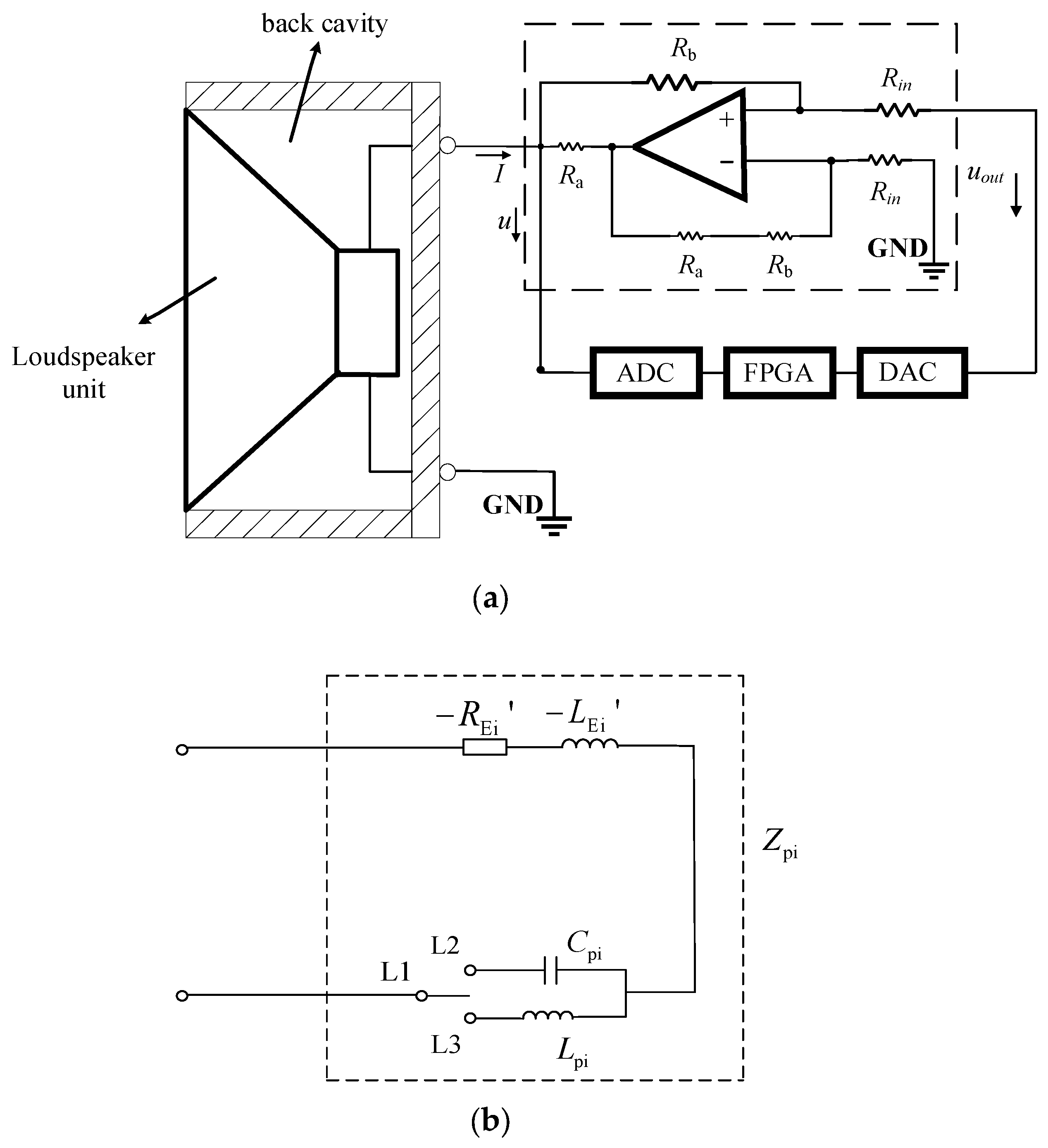

2.1. Model of a Tunable Hybrid Digital–Analog Shunt Speaker Unit

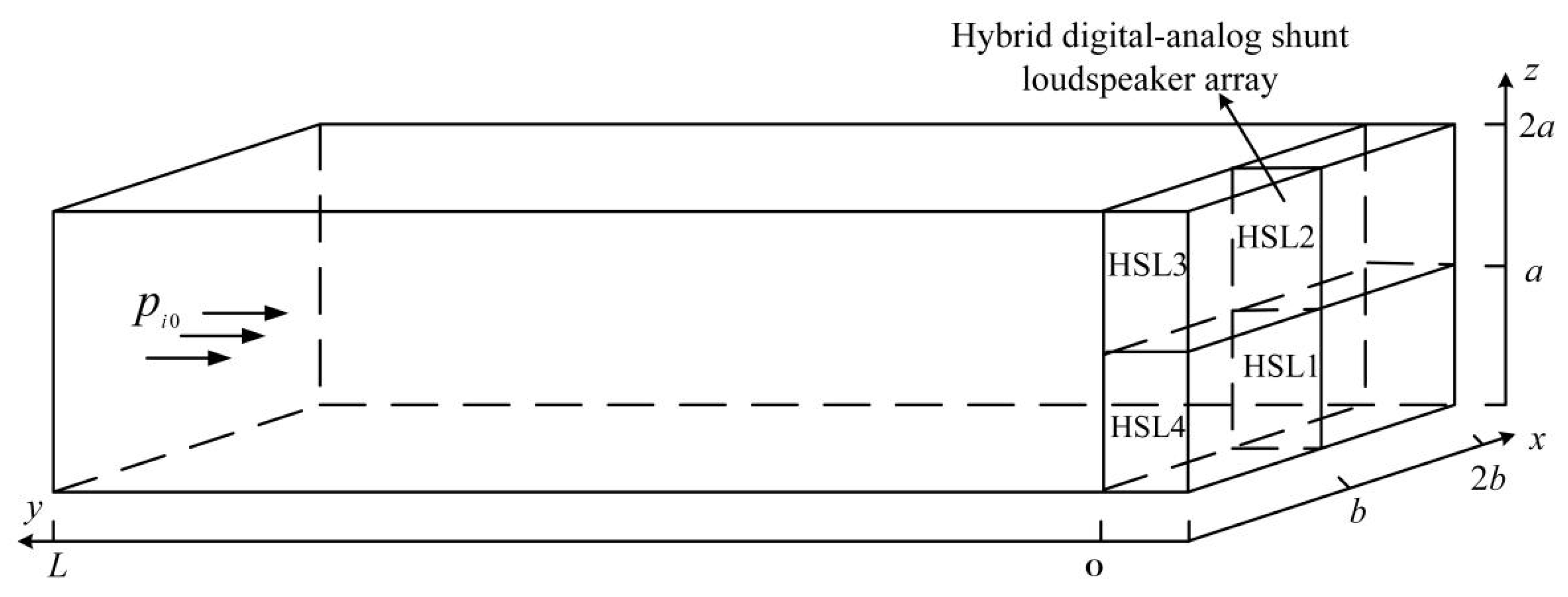

2.2. Theoretical Model of the HSLA Absorber

3. Numerical Simulations

3.1. Simulation Setup

3.1.1. The Loudspeaker Parameters and Shunt Circuit Configuration of Each Unit

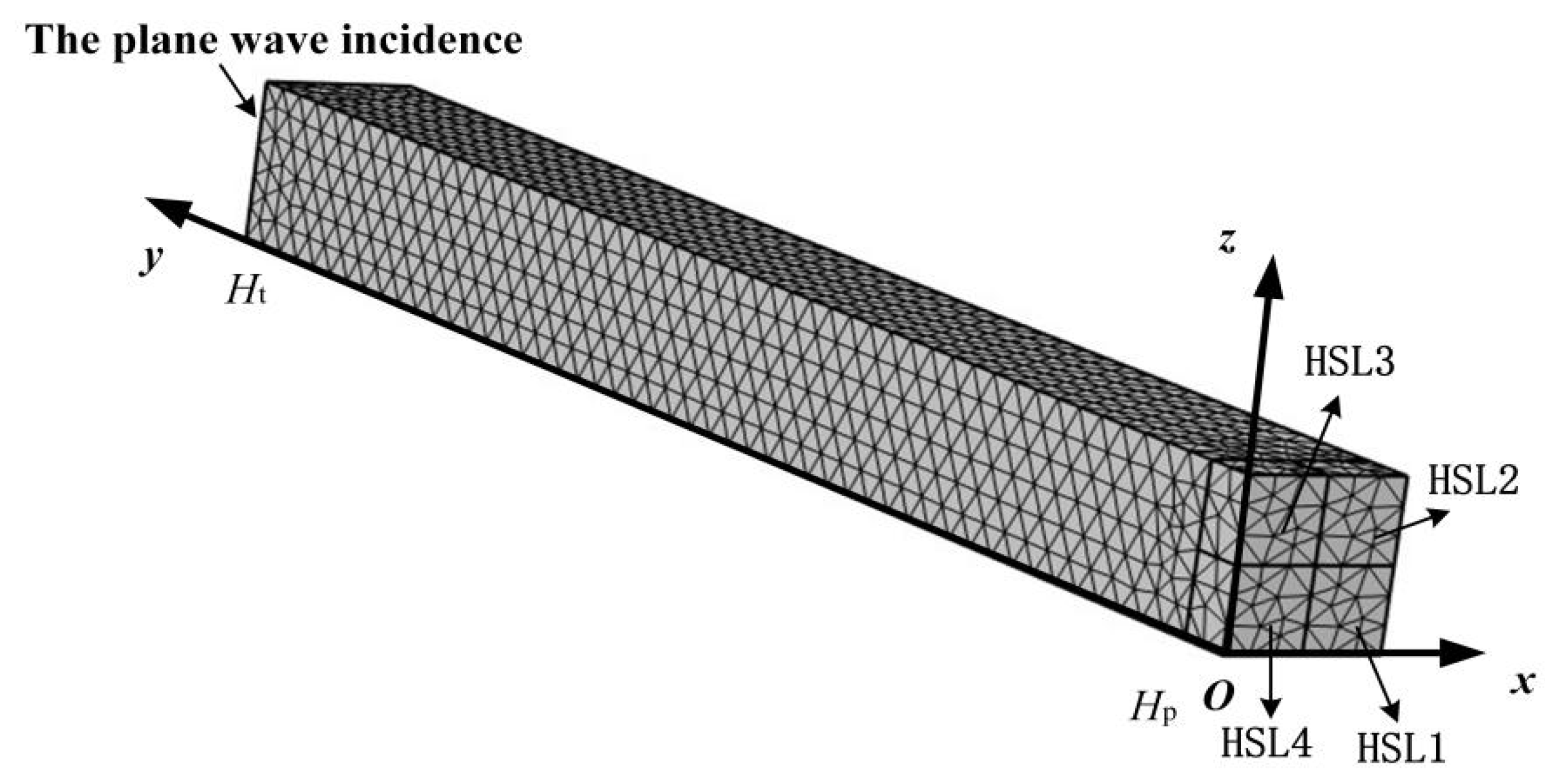

3.1.2. The Finite Element Modeling

3.2. Simulation Results

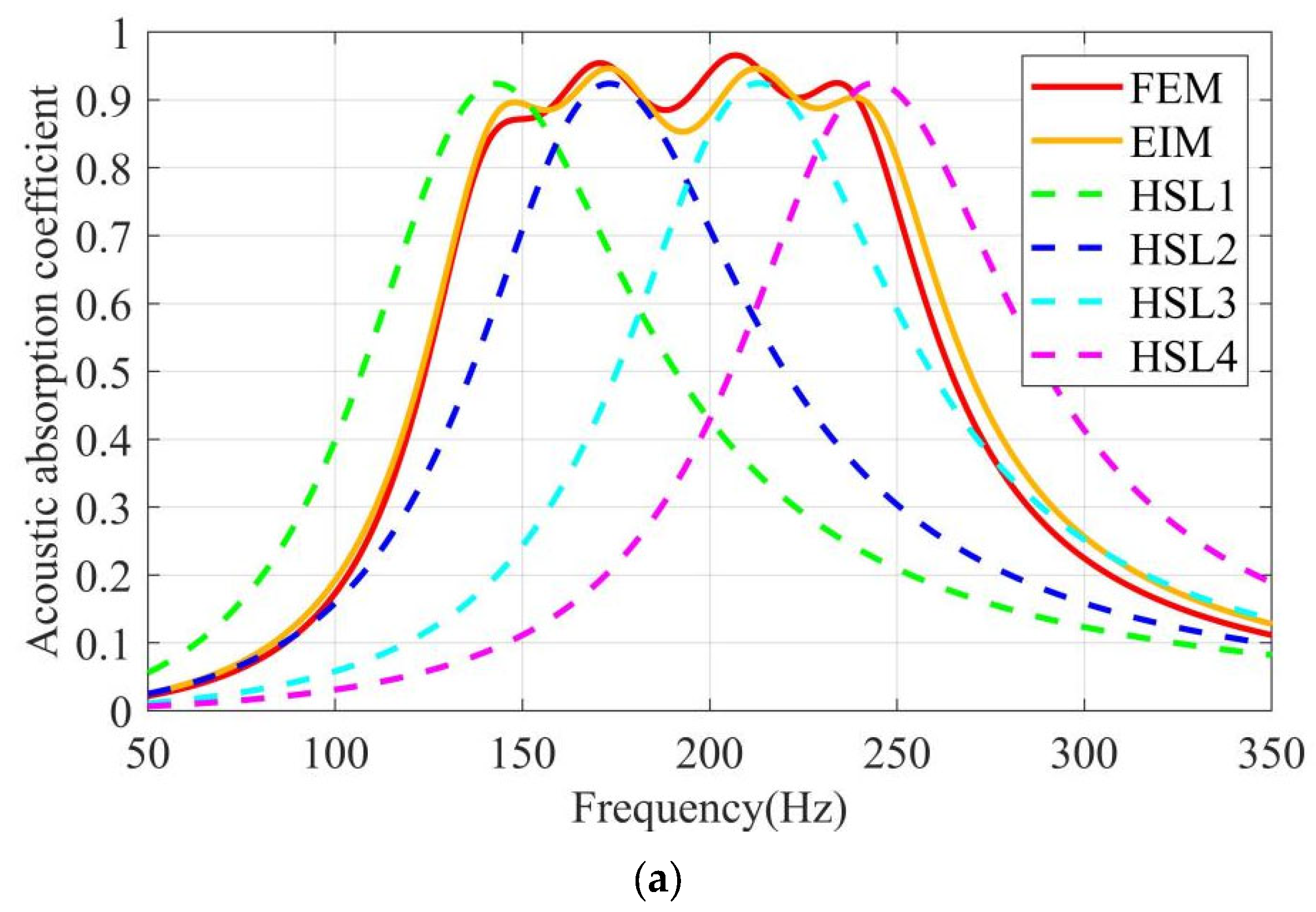

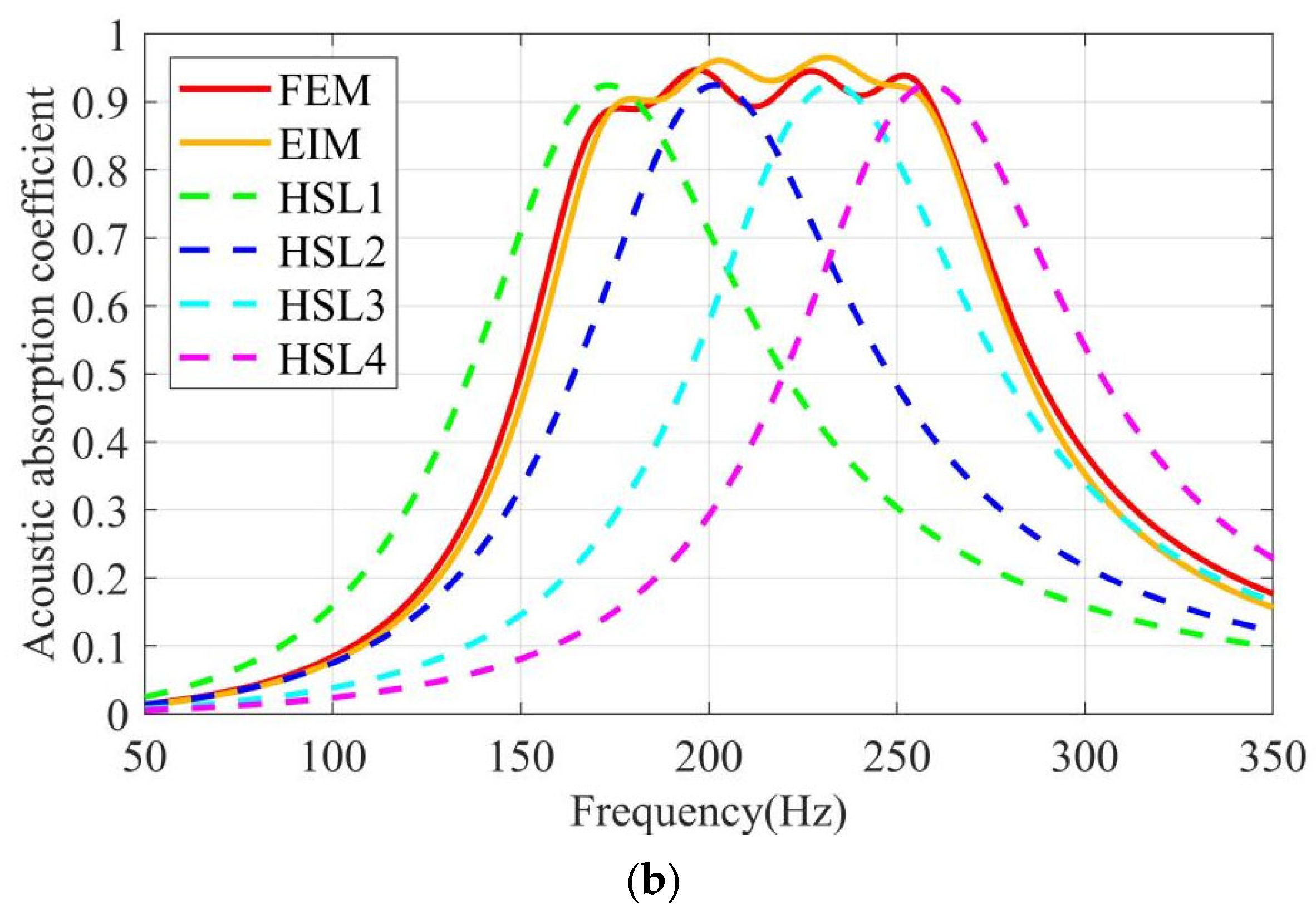

3.2.1. Sound Absorption Coefficients of the HSLA Low-Frequency Absorber

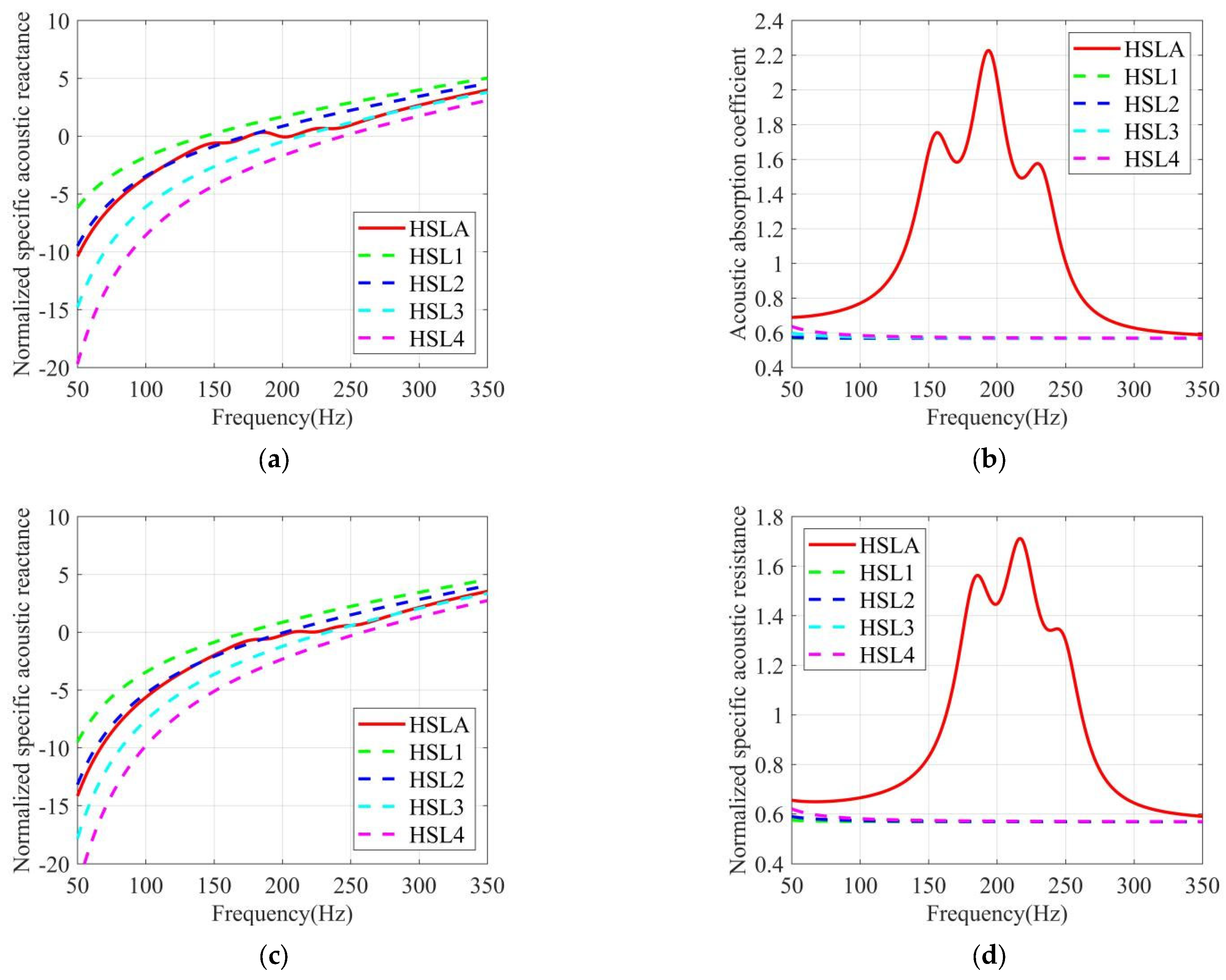

3.2.2. Normalized Specific Acoustic Impedance

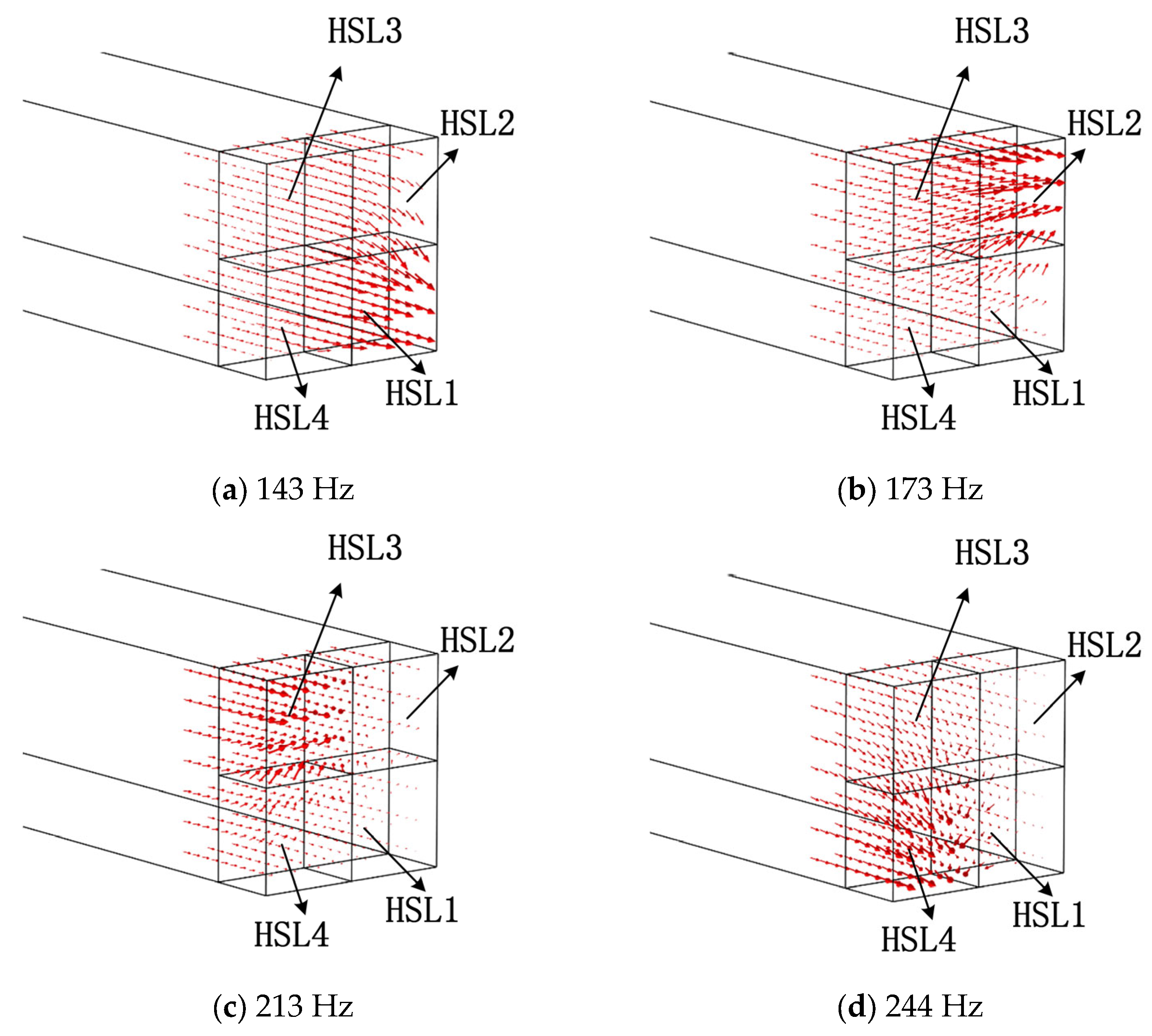

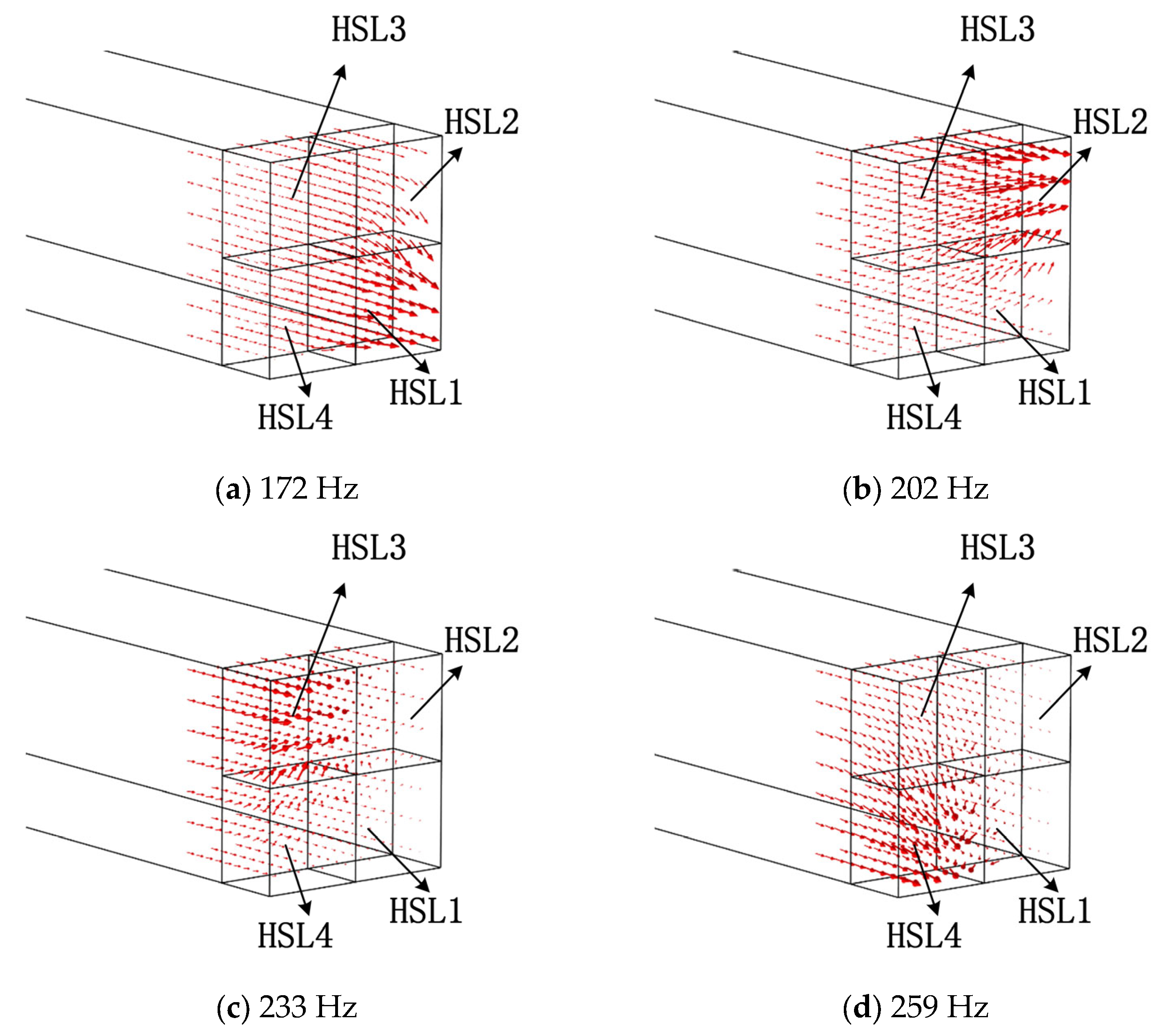

3.2.3. Sound Intensity Distribution

4. Experiments

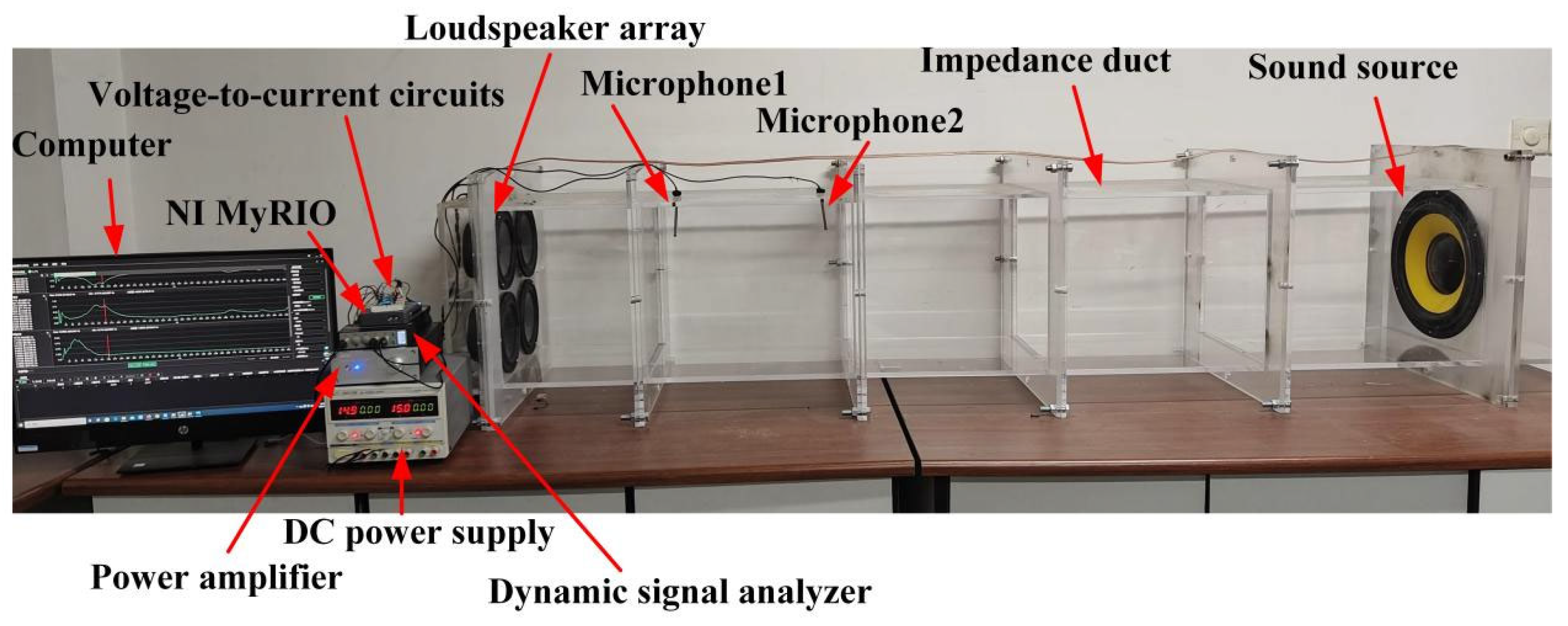

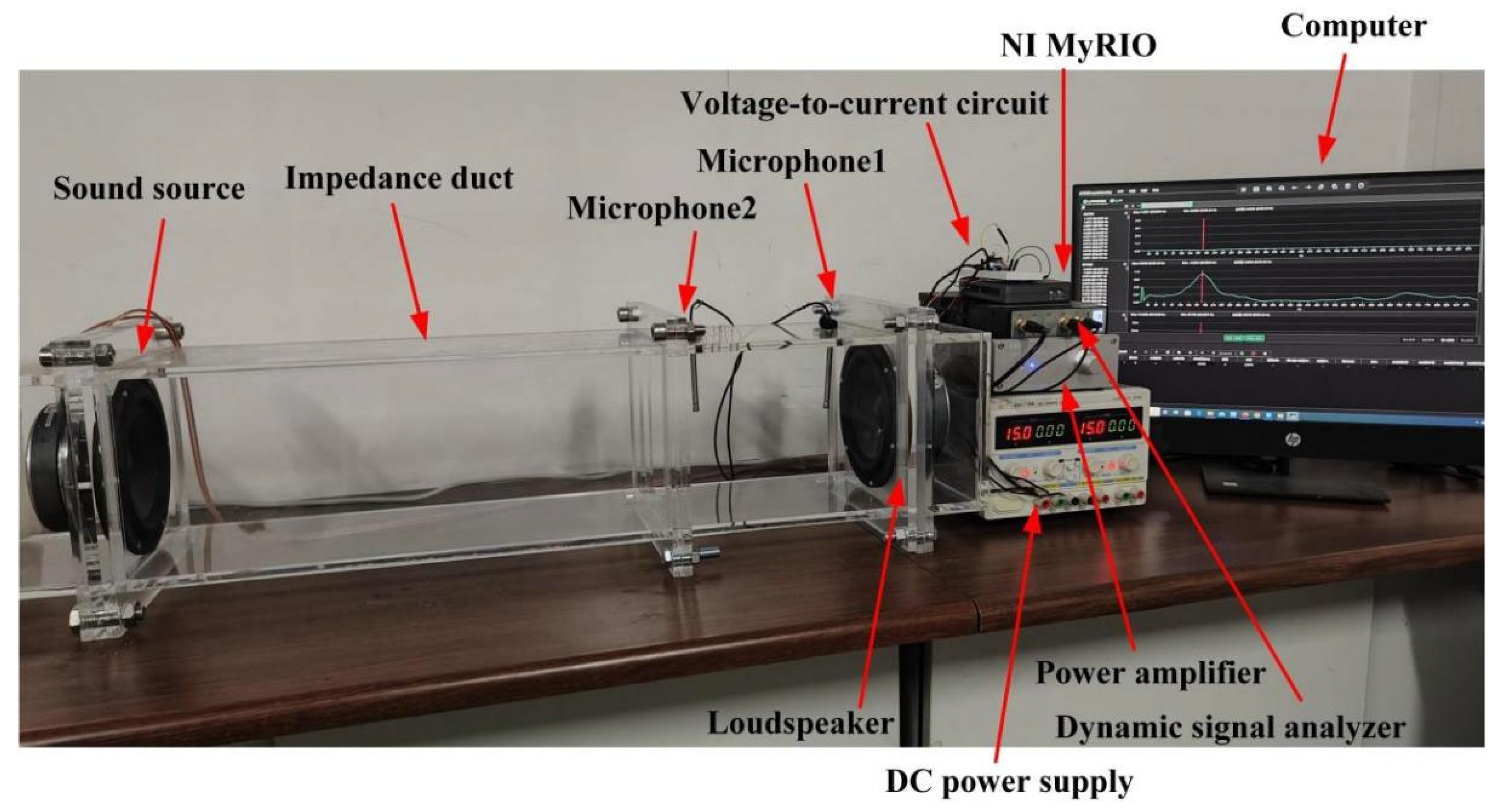

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Experimental Setup of the Proposed HSLA Absorber

4.1.2. Experimental Setup of the HSL1–HSL4 Units

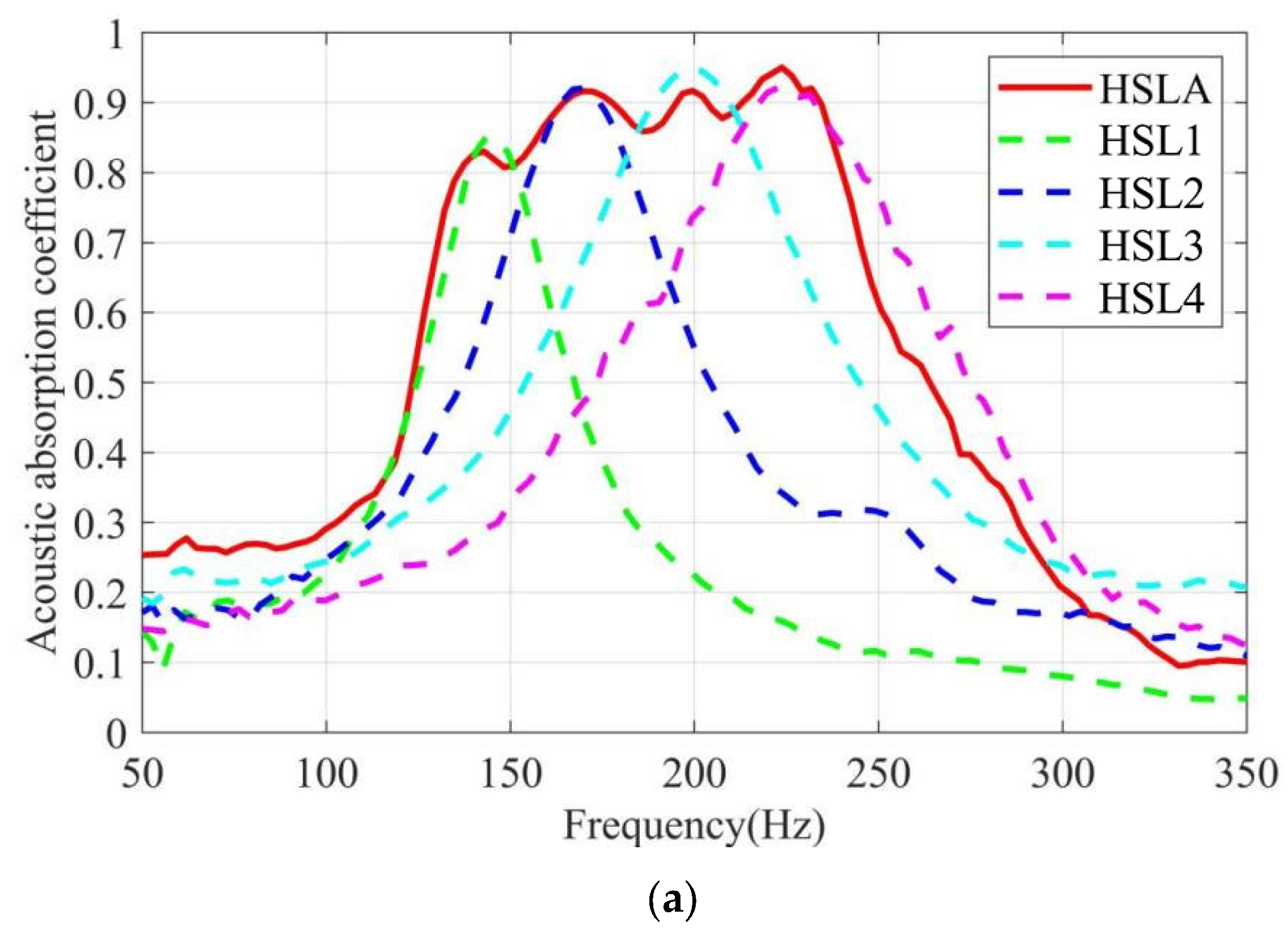

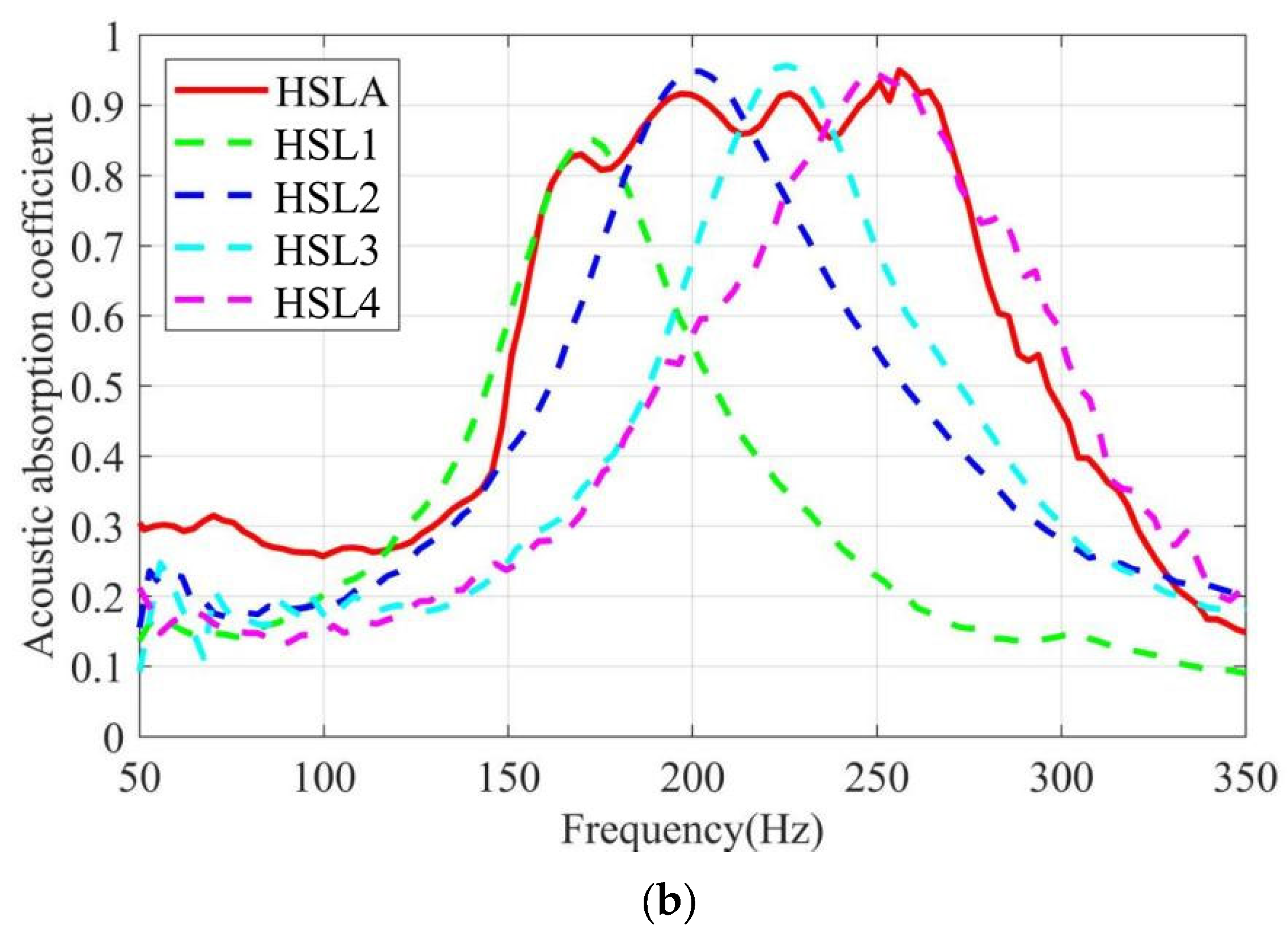

4.2. Experimental Results of the HSLA Low-Frequency Sound Absorber

4.2.1. Experimental Results of the HSLA and HSLi Units

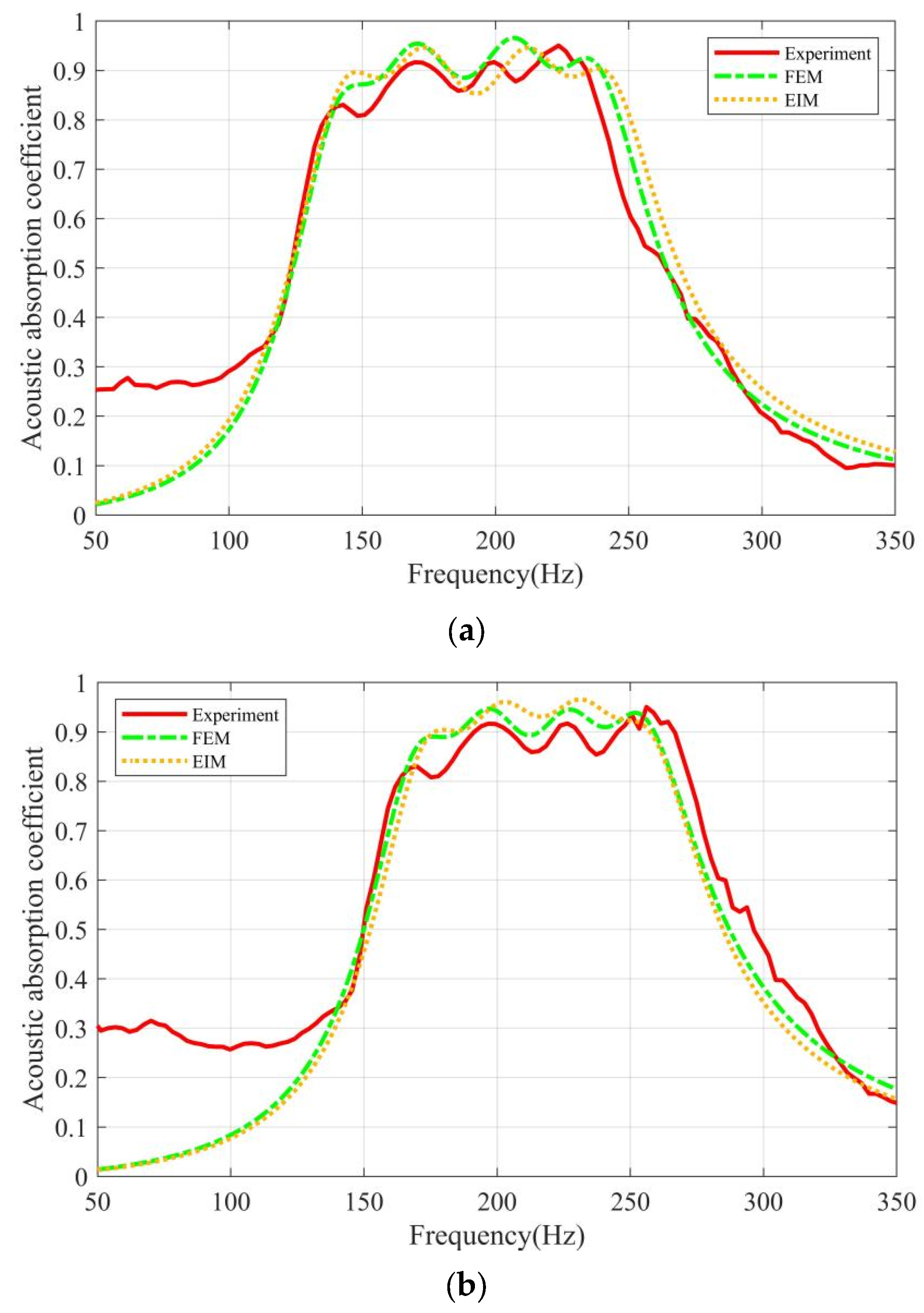

4.2.2. Comparison of Experimental Results with Simulated Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, M.Y.; Chen, C.; Li, X.D. The influence of the grazing flow and sound incidence direction on the acoustic characteristics of double Helmholtz resonators. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 202, 109160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompoli, F. Acoustical Characterization and Modeling of Sustainable Posidonia Fibers. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maa, D.Y. Microperforated-panel wideband absorbers. Noise Control Eng. J. 1987, 29, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, G.; Singh, S. Near-perfect sound absorptions in low-frequencies by varying compositions of porous labyrinthine acoustic metamaterial. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 198, 108974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.W.; Liu, Y.Y.; Sun, W.; Wang, H.; Lei, Y.; Wang, H.; Zeng, X. Broadband low-frequency sound absorbing metastructures composed of impedance matching coiled-up cavity and porous materials. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 200, 109061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.M.; Wu, J.W.; Yan, S.L.; Mao, Q.B. Design and study of broadband sound absorbers with partition based on micro-perforated panel and Helmholtz resonator. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 205, 109262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetiyo, I.; Sihar, I.; Sudarsono, A.S. Sound absorption characteristics of thin parallel microperforated panel (MPP) for random incidence field. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 201, 109131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissek, H.; Boulandet, R.; Fleury, R. Electroacoustic absorbers: Bridging the gap between shunt loudspeakers and active sound absorption. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2011, 129, 2968–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Wu, K.M.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, L.X. A programmable resonator based on a shunt-electro-mechanical diaphragm. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 229, 107532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černík, M.; Mokrý, P. Sound reflection in an acoustic impedance tube terminated with a loudspeaker shunted by a negative impedance converter. Smart Mater. Struct. 2012, 21, 115016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivet, E.; Karkar, S.; Lissek, H. Multi-degree-of-freedom low-frequency electroacoustic absorbers through coupled resonators. Appl. Acoust. 2018, 132, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.J.; Niederberger, D.; Moheimani, S.O.R.; Morari, M. Control of resonant acoustic sound fields by electrical shunting of a loudspeaker. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2007, 15, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissek, H.; Boulandet, R.; Rivet, E. Optimization of electric shunt resonant circuits for electroacoustic absorbers. In Proceedings of the Acoustics 2012 Nantes Conference, Nantes, France, 23–27 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, R.X.; Tao, J.C.; Qiu, X.J. Shunted loudspeakers for transformer noise absorption. In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress on Sound and Vibration, Beijing, China, 13–17 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, C.N.; Tao, J.C.; Qiu, X.J. Thin multi-tone sound absorbers based on analog circuit shunt loudspeakers. Noise Control Eng. J. 2018, 66, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, C.N.; Tao, J.C.; Qiu, X.J. A multi-tone sound absorber based on an array of shunted loudspeakers. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.J.; Cong, C.N.; Tao, J.C.; Qiu, X.J. Dual frequency sound absorption with an array of shunt loudspeakers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Huang, L.X.; Zhang, Z.Y. Tunable noise absorption by shunted loudspeaker. In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress on Sound and Vibration, Beijing, China, 13–17 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Chan, Y.J.; Huang, L.X. Thin broadband noise absorption through acoustic reactance control by electro-mechanical coupling without sensor. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2014, 135, 2738–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Wang, C.Q.; Huang, L.X. Tuning of the acoustic impedance of a shunted electro-mechanical diaphragm for a broadband sound absorber. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 126, 536–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Li, X.; Liu, B.L. Optimization of shunted loudspeaker for sound absorption by fully exhaustive and backtracking algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivet, E.; Boulandet, R.; Lissek, H.; Rigas, I. Study on room modal equalization at low frequencies with electroacoustic absorbers. In Proceedings of the Acoustics 2012 Nantes Conference, Nantes, France, 23–27 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Huang, L.X. Electroacoustic Control of Rijke Tube Instability. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 409, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.C.; Jing, R.X.; Qiu, X.J. Sound absorption of a finite micro-perforated panel backed by a shunted loudspeaker. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2014, 135, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cao, Z.G.; Li, Z.H.; Liu, B.L. Sound absorption of a shunt loudspeaker on a perforated plate. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 193, 108776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.G.; Li, X.; Liu, B.L. Broadband sound absorption of a hybrid absorber with shunt loudspeaker and perforated plates. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 203, 109185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulandet, R.; Rivet, E.; Lissek, H. Sensorless Electroacoustic Absorbers Through Synthesized Impedance Control for Damping Low-Frequency Modes in Cavities. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2016, 102, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.B.; Cong, C.N. Design of adjustable low-frequency sound absorbers through hybrid digital-analog shunt loudspeakers. Appl. Acoust. 2025, 228, 110331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.B.; Liu, J.C.; Cong, C.N. Study on adjustable dual-frequency sound absorber based on hybrid digital-analog shunt loudspeakers. In Proceedings of the 3nd International Conference on Acoustics, Fluid Mechanics and Engineering, Hangzhou, China, 8–10 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.C.; Xu, Y.B.; Cong, C.N. Study on low-frequency broadband sound absorption based on an array of shunt loudspeakers. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Image, Signal Processing and Pattern Recognition, Nanjing, China, 28–30 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10534-2:1998; Acoustics—Determination of Sound Absorption Coefficient and Impedance in Impedance Tubes. Part 2: Transfer Function Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| DC resistor | RE1 | 7.25 | Ω |

| Voice coil inductor | LE1 | 0.475 | mH |

| Force factor | B1l1 | 7.813 | N/A |

| Moving mass | Mms1 | 13.80 | g |

| Mechanical resistance | Rms1 | 1.214 | kg/s |

| Mechanical compliance | Cms1 | 0.667 | mm/N |

| Effective area | S | 2.1 × 10−2 | m2 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| DC resistor | RE2 | 6.41 | Ω |

| Voice coil inductor | LE2 | 0.369 | mH |

| Force factor | B2l2 | 7.924 | N/A |

| Moving mass | Mms2 | 15.107 | g |

| Mechanical resistance | Rms2 | 1.578 | kg/s |

| Mechanical compliance | Cms2 | 0.360 | mm/N |

| Effective area | S | 2.1 × 10−2 | m2 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| DC resistor | RE3 | 6.95 | Ω |

| Voice coil inductor | LE3 | 0.472 | mH |

| Force factor | B3l3 | 8.111 | N/A |

| Moving mass | Mms3 | 15.468 | g |

| Mechanical resistance | Rms3 | 1.326 | kg/s |

| Mechanical compliance | Cms3 | 0.61 | mm/N |

| Effective area | S | 2.1 × 10−2 | m2 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| DC resistor | RE4 | 6.91 | Ω |

| Voice coil inductor | LE4 | 0.467 | mH |

| Force factor | B4l4 | 8.273 | N/A |

| Moving mass | Mms4 | 16.475 | g |

| Mechanical resistance | Rms4 | 1.401 | kg/s |

| Mechanical compliance | Cms4 | 0.596 | mm/N |

| Effective area | S | 2.1 × 10−2 | m2 |

| Lpi | Cpi | |

|---|---|---|

| HSL1 | / | 71 μF |

| HSL2 | 23.5 mH | / |

| HSL3 | 6.3 mH | / |

| HSL4 | 3.9 mH | / |

| Lpi | Cpi | |

|---|---|---|

| HSL1 | 23.5 mH | / |

| HSL2 | 7.9 mH | / |

| HSL3 | 4.5 mH | / |

| HSL4 | 2.2 mH | / |

| a0 | a1 | a2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSL1 (Cp1 = 70.78 μF) | −6.4098 | −0.0003 | −6.4110 |

| HSL2 (Lp2 = 23.46 mH) | 2.3395 | 2.3540 | / |

| HSL3 (Lp3 = 6.253 mH) | 0.6181 | 0.6319 | / |

| HSL4 (Lp4 = 3.851 mH) | 0.3781 | 0.3920 | / |

| a0 | a1 | a2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSL1 (Lp1 = 23.46 mH) | 2.3395 | 2.3540 | / |

| HSL2 (Lp2 = 7.932 mH) | 0.7851 | 0.7989 | / |

| HSL3 (Lp3 = 4.451 mH) | 0.4381 | 0.4521 | / |

| HSL4 (Lp4 = 2.174 mH) | 0.2109 | 0.2238 | / |

| Experiments | Simulations | ε | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIM | FEM | εEF | εES0 | |||

| Configuration 1 | fll (Hz) | 125 | 123 | 125 | 1.6% | 0% |

| ful (Hz) | 264 | 269 | 264 | 1.9% | 0% | |

| h | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 1.2% | 1.2% | |

| Configuration 2 | fll (Hz) | 151 | 154 | 151 | 1.9% | 0% |

| ful (Hz) | 296 | 284 | 284 | 0% | 4.1% | |

| h (Hz) | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 1.2% | 2.4% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Xu, Y.; Cong, C.; Wu, J. Research on Low-Frequency Sound Absorption Based on the Combined Array of Hybrid Digital–Analog Shunt Loudspeakers. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12774. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312774

Liu J, Xu Y, Cong C, Wu J. Research on Low-Frequency Sound Absorption Based on the Combined Array of Hybrid Digital–Analog Shunt Loudspeakers. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12774. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312774

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jiachen, Yubing Xu, Chaonan Cong, and Jiawei Wu. 2025. "Research on Low-Frequency Sound Absorption Based on the Combined Array of Hybrid Digital–Analog Shunt Loudspeakers" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12774. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312774

APA StyleLiu, J., Xu, Y., Cong, C., & Wu, J. (2025). Research on Low-Frequency Sound Absorption Based on the Combined Array of Hybrid Digital–Analog Shunt Loudspeakers. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12774. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312774